Content of Carnosic Acid, Carnosol, Rosmarinic Acid, and Proximate Composition in an Assortment of Dried Sage (Salvia officinalis L.)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

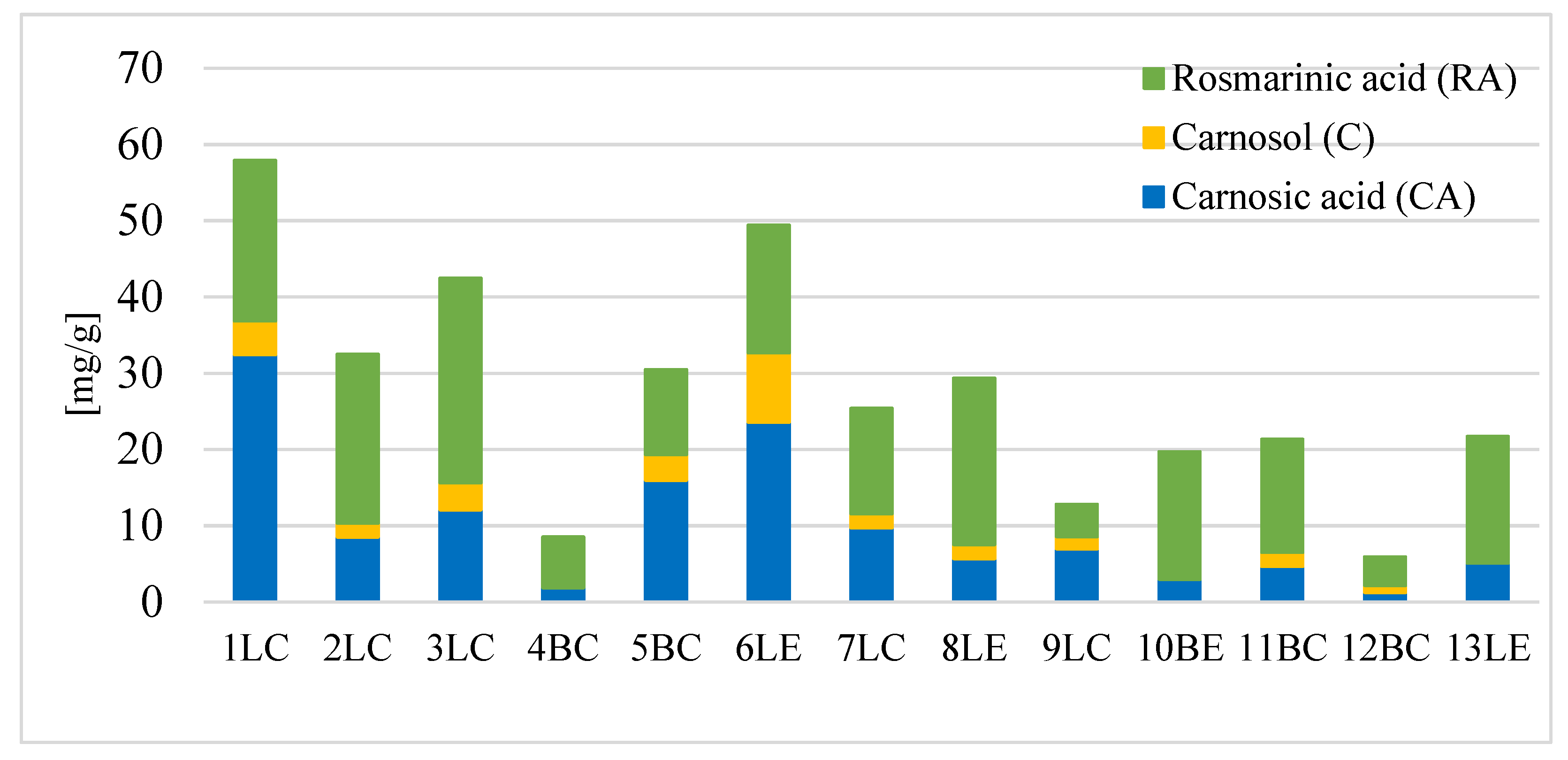

2.1. Bioactive Compounds

2.2. Composition of Basic Nutrients and Moisture

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sage (Salvia officinalis L.)

3.2. Other Materials

3.3. Preparation of Sage Extracts

3.4. Determination of Total Polyphenol Content

3.5. Determination of Total Flavonoid Content

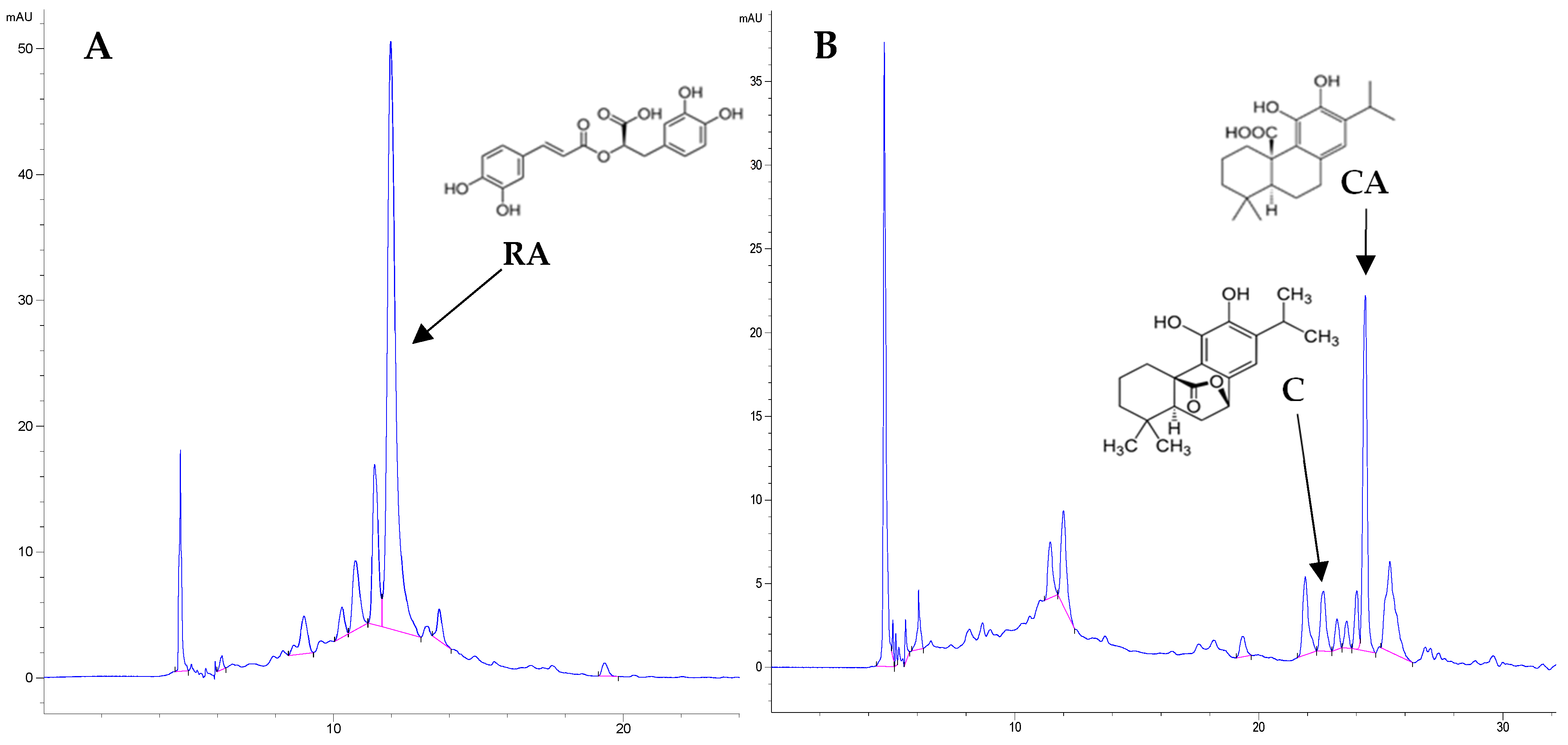

3.6. Determination of Rosmarinic and Carnosic Acid and Carnosol Using Liquid Chromatography (HPLC)

3.7. Proximate Composition—Nutrients and Moisture

3.8. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Akacha, B.B.; Kačániová, M.; Mekinić, I.G.; Kukula-Koch, W.; Koch, W.; Orhan, I.E.; Cmikova, N.; Taglieri, I.; Venturi, F.; Samartin, C.; et al. Sage (Salvia officinalis L.): A botanical marvel with versatile pharmacological properties and sustainable applications in functional foods. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2024, 169, 361–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrebień-Filisińska, A.M.; Bartkowiak, A. Antioxidative effect of sage (Salvia officinalis L.) macerate as “green extract” in inhibiting the oxidation of fish oil. Antioxidants 2021, 11, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farruggia, D.; Di Miceli, G.; Licata, M.; Leto, C.; Salamone, F.; Novak, J. Foliar application of various biostimulants produces contrasting response on yield, essential oil and chemical properties of organically grown sage (Salvia officinalis L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1397489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggini, V.; Bertazza, G.; Gallo, E.; Mascherini, V.; Calvi, L.; Marra, C.; Michelucci, F.; Liberati, C.; Trassi, A.; Baraldi, R.; et al. The Different Phytochemical Profiles of Salvia officinalis Dietary Supplements Labelled for Menopause Symptoms. Molecules 2023, 29, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawiślak, G. Yield and chemical composition of essential oil from Salvia officinalis L. in third year of cultivation. Herba Pol. 2014, 60, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Đurović, S.; Micić, D.; Pezo, L.; Radić, D.; Bazarnova, J.G.; Smyatskaya, Y.A.; Blagojević, S. The effect of various extraction techniques on the quality of sage (Salvia officinalis L.) essential oil, expressed by chemical composition, thermal properties and biological activity. Food Chem. X 2022, 13, 100213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hrebień-Filisińska, A.M.; Bartkowiak, A. The use of sage oil macerates (Salvia officinalis L.) for oxidative stabilization of cod liver oil in bulk oil systems. Int. J. Food Sci. 2020, 2020, 4971203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleš, I.; Dobrinčić, A.; Zorić, Z.; Vladimir-Knežević, S.; Elez Garofulić, I.; Repajić, M.; Skroza, D.; Jerković, I.; Dragović-Uzelac, V. Phenolic, headspace and sensory profile, and antioxidant capacity of fruit juice enriched with Salvia officinalis L. and Thymus serpyllum L. extract: A potential for a novel herbal-based functional beverages. Molecules 2023, 28, 3656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starowicz, M.; Lelujka, E.; Ciska, E.; Lamparski, G.; Sawicki, T.; Wronkowska, M. The application of Lamiaceae Lindl. promotes aroma compounds formation, sensory properties, and antioxidant activity of oat and buckwheat-based cookies. Molecules 2020, 25, 5626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boufadi, M.Y.; Keddari, S.; Moulai-Hacene, F.; Chaa, S. Chemical composition, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of Salvia officinalis extract from Algeria. Pharmacogn. J. 2021, 13, 1549–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouloumpasi, E.; Hatzikamari, M.; Christaki, S.; Lazaridou, A.; Chatzopoulou, P.; Biliaderis, C.G.; Irakli, M. Assessment of Antioxidant and Antibacterial Potential of Phenolic Extracts from Post-Distillation Solid Residues of Oregano, Rosemary, Sage, Lemon Balm, and Spearmint. Processes 2024, 12, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jažo, Z.; Glumac, M.; Paštar, V.; Bektić, S.; Radan, M.; Carev, I. Chemical composition and biological activity of Salvia officinalis L. Essential oil. Plants 2023, 12, 1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Başkan, S.; Öztekin, N.; Erim, F.B. Determination of carnosic acid and rosmarinic acid in sage by capillary electrophoresis. Food Chem. 2007, 101, 1748–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdahl, D.B.; McKeague, J. Rosemary and Sage Extracts as Antioxidants for Food Preservation. In Handbook of Antioxidants for Food Preservation; Shahidi, F., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2015; Volume 276, pp. 177–217. [Google Scholar]

- Mutschlechner, B.; Schwaiger, S.; Schneider, P.; Stuppner, H. Degradation study of carnosic acid. Planta Medica 2016, 82, S1–S381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizani, R.S.; Viganó, J.; Contieri, L.S.; Strieder, M.M.; Kamikawashi, R.K.; Vilegas, W.; de Souza Mesquita, L.M.; Rostagno, M.A. New selective and sustainable ultrasound-assisted extraction procedure to recover carnosic and rosmarinic acids from Rosmarinus officinalis by sequential use of bio-based solvents. Food Chem. 2024, 435, 137540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mo, C.J.; Xu, Y.Q.; Feng, Y.; Chen, A.J.; Yang, C.W.; Ni, H. Simultaneous preparation of water-and lipid-soluble antioxidant and antibacterial activity of purified carnosic acid from Rosmarinus offoccnalis L. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 187, 115448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wei, C.; Zhao, J.; Zhou, D.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zuo, H.; Dong, J.; Zhao, Z.; Hao, M.; et al. Carnosic acid: An effective phenolic diterpenoid for prevention and management of cancers via targeting multiple signaling pathways. Pharmacol. Res. 2024, 206, 107288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-quality-herbal-medicinal-products-traditional-herbal-medicinal-products-revision-2_en.pdf (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- European Pharmacopoeia Commission: Sage leaf (Salvia officinalis). In European Pharmacopoeia; European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines: Strasbourg, France, 2008; pp. 2853–2856.

- Bodalska, A.; Kowalczyk, A.; Fecka, I. Stability of rosmarinic acid and flavonoid glycosides in liquid forms of herbal medicinal products—A preliminary study. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aćimović, M.; Pezo, L.; Čabarkapa, I.; Trudić, A.; Stanković Jeremić, J.; Varga, A.; Lončar, B.; Šovljanski, O.; Tešević, V. Variation of Salvia officinalis L. essential oil and hydrolate composition and their antimicrobial activity. Processes 2022, 10, 1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu, M.; Muller, M.; Alegre, L.; Munne’-Bosch, S. Phenolic diterpene and α-tocopherol contents in leaf extracts of 60 Salvia species. J. Sci. Agric. 2008, 88, 2648–2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavić, V.; Jakovljević, M.; Molnar, M.; Jokić, S. Extraction of Carnosic Acid and Carnosol from Sage (Salvia officinalis L.) Leaves by Supercritical Fluid Extraction and Their Antioxidant and Antibacterial Activity. Plants 2019, 8, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Du, J.; Ou, Y.; Xu, H.; Chen, X.; Zhou, A.; Liping, H.; Cao, Y. Degradation pathway of carnosic acid in methanol solution through isolation and structural identification of its degradation products. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2013, 237, 617–626. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00217-013-2035-5 (accessed on 20 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Lamien-Meda, A.; Nell, M.; Lohwasser, U.; Börner, A.; Franz, C.; Novak, J. Investigation of antioxidant and rosmarinic acid variation in the sage collection of the genebank in Gatersleben. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 3813–3819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulinacci, N.; Innocenti, M.; Bellumori, M.; Giaccherini, C.; Martini, V.; Michelozzi, M. Storage Method, Drying Processes and Extraction Procedures Strongly Affect the Phenolic Fraction of Rosemary Leaves: An HPLC/DAD/MS Study. Talanta 2011, 85, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhat, M.B.; Landoulsi, A.; Chaouch-Hamada, R.; Sotomayor, J.A.; Jordán, M.J. Characterization and quantification of phenolic compounds and antioxidant properties of Salvia species growing in different habitats. Ind. Crops Prod. 2013, 49, 904–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paloukopoulou, C.; Karioti, A. A Validated Method for the Determination of Carnosic Acid and Carnosol in the Fresh Foliage of Salvia rosmarinus and Salvia officinalis from Greece. Plants 2022, 11, 3106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragović-Uzelac, V.; Elez Garofulić, I.; Jukić, M.; Penić, M.; Dent, M. The influence of microwave-assisted extraction on the isolation of sage (Salvia officinalis L.) polyphenols. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2012, 50, 377–383. [Google Scholar]

- Hrebień-Filisińska, A.M.; Tokarczyk, G. The use of ultrasound-assisted maceration for the extraction of carnosic acid and carnosol from sage (Salvia officinalis L.) directly into fish oil. Molecules 2023, 28, 6094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mervić, M.; Bival Štefan, M.; Kindl, M.; Blažeković, B.; Marijan, M.; Vladimir-Knežević, S. Comparative Antioxidant, Anti-Acetylcholinesterase and Anti-α-Glucosidase Activities of Mediterranean Salvia Species. Plants 2022, 11, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, P.J.; Ubera, J.L.; Tena, M.T.; Valcárcel, M. Determination of the carnosic acid content in wild and cultivated Rosmarinus officinalis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1998, 46, 2624–2627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brückner, K.; Božić, D.; Manzano, D.; Papaefthimiou, D.; Pateraki, I.; Scheler, U.; Ferrer, A.; de Vos, R.C.H.; Kanellis, A.; Tissier, A. Characterization of two genes for the biosynthesis of abietane-type diterpenes in rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis) glandular trichomes. Phytochemistry 2014, 101, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuvelier, M.E.; Richard, H.; Berset, C. Antioxidative activity and phenolic composition of pilot-plant and commercial extracts of sage and rosemary. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 1996, 73, 645–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhat, M.B.; Chaouch-Hamada, R.; Sotomayor, J.A.; Landoulsi, A.; Jordán, M.J. Antioxidant potential of Salvia officinalis L. residues as affected by the harvesting time. Ind. Crops Prod. 2014, 54, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yesil-Celiktas, O.; Girgin, G.Ö.Z.D.E.; Orhan, H.; Wichers, H.J.; Bedir, E.; Vardar-Sukan, F. Screening of free radical scavenging capacity and antioxidant activities of Rosmarinus officinalis extracts with focus on location and harvesting times. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2007, 224, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regulation (EU) 2018/848 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 May 2018 on Organic Production and Labelling of Organic Products, and Repealing Council Regulation (EC) No 834/2007; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2018.

- Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 2011 on the Provision of Food Information to Consumers; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2011.

- Tounekti, T.; Munné-Bosch, S.; Vadel, A.M.; Chtara, C.; Khemira, H. Influence of ionic interactions on essential oil and phenolic diterpene composition of Dalmatian sage (Salvia officinalis L.). Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2010, 48, 813–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tounekti, T.; Hernández, I.; Müller, M.; Khemira, H.; Munné-Bosch, S. Kinetin applications alleviate salt stress and improve the antioxidant composition of leaf extracts in Salvia officinalis. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2011, 49, 1165–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettaieb, I.; Hamrouni-Sellami, I.; Bourgou, S.; Limam, F.; Marzouk, B. Drought effects on polyphenol composition and antioxidant activities in aerial parts of Salvia officinalis L. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2011, 33, 1103–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luis, J.C.; Pérez, R.M.; González, F.V. UV-B radiation effects on foliar concentrations of rosmarinic and carnosic acids in rosemary plants. Food Chem. 2007, 101, 1211–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Generalić, I.; Skroza, D.; Ljubenkov, I.; Katalinić, A.; Burčul, F.; Katalinić, V. Influence of the phenophase on the phenolic profile and antioxidant properties of Dalmatian sage. Food Chem. 2011, 127, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gird, C.E.; Nencu, I.; Costea, T.; Duţu, L.E.; Popescu, M.L.; Ciupitu, N. Quantitative analysis of phenolic compounds from Salvia officinalis L. leaves. Farmacia 2014, 62, 649–657. [Google Scholar]

- Sadowska, U.; Kopeć, A.; Kourimska, L.; Zarubova, L.; Kloucek, P. The effect of drying methods on the concentration of compounds in sage and thyme. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2017, 41, e13286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwaśniewska-Karolak, I.; Mostowski, R. Effect of different drying processes on an antioxidant potential of three species of the family. Herba Pol. 2021, 67, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamrouni-Sellami, I.; Rahali, F.Z.; Rebey, I.B.; Bourgou, S.; Limam, F.; Marzouk, B. Total phenolics, flavonoids, and antioxidant activity of sage (Salvia officinalis L.) plants as affected by different drying methods. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2013, 6, 806–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khiya, Z.; Oualcadi, Y.; Gamar, A.; Berrekhis, F.; Zair, T.; Hilali, F.E. Correlation of total polyphenolic content with antioxidant activity of hydromethanolic extract and their fractions of the Salvia officinalis leaves from different regions of Morocco. J. Chem. 2021, 2021, 8585313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajewicz, M.; Staszek, D.; Waksmundzka-Hajnos, M.; Kowalska, T. Comparison of TLC and HPLC fingerprints of phenolic acids and flavonoids fractions derived from selected sage (Salvia) species. J. Liq. Chromatogr. Relat. Technol. 2012, 35, 1388–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 11165:1995; Dried sage (Salvia officinalis L.)—5Specification. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1995. Available online: https://cdn.standards.iteh.ai/samples/19175/eb158cac07c84fd6a9da1dc2d82fe15d/ISO-11165-1995.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- ISO 9909:1997; Oil of Dalmatian sage (Salvia officinalis L.). ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1997. Available online: https://cdn.standards.iteh.ai/samples/17791/fd17d5982b7b481b9f22b4426d3aaa13/ISO-9909-1997.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Karagözoğlu, Y.; Kiran, T.R. Determination of Nutrient Contents of Some Medicinal Plants Sold by Herbalists in Bingol. ODU Med. J. 2023, 10, 41–53. Available online: https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/pub/odutip (accessed on 25 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Vlaicu, P.A.; Untea, A.E.; Turcu, R.P.; Saracila, M.; Panaite, T.D.; Cornescu, G.M. Nutritional Composition and Bioactive Compounds of Basil, Thyme and Sage Plant Additives and Their Functionality on Broiler Thigh Meat Quality. Foods 2022, 11, 1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomescu, A.; Rus, C.; Pop, G.; Alexa, E.; Radulov, I.; Imbrea, I.M.; Negrea, M. Elements Composition Of Some Medicinal Plants Belonging to the Lamiaceae Family. Lucr. Ştiinţifice Ser. Agron. 2015, 58, 175–180. [Google Scholar]

- Todorova, M.; Grigorova, S.; Gjorgovska, N. Effects of Sage (Salvia officinalis L.) Supplementation in Hen Diets on Laying Productivity, Egg Quality, and Biochemical Parameters. Acta Fytotechn Zootech. 2024, 27, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biel, W.; Pomietło, U.; Witkowicz, R.; Piątkowska, E.; Kopeć, A. Proximate Composition and Antioxidant Activity of Selected Morphological Parts of Herbs. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, V.L.; Rossi, J.A. Colorimetry of total phenolics with phosphomolybdic-phosphotungstic acid reagents. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1965, 16, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.W.; Khong, N.M.; Iqbal, S.; Ch’Ng, S.E.; Babji, A.S. Preparation of clove buds deodorized aqueous extract (CDAE) and evaluation of its potential to improve oxidative stability of chicken meatballs in comparison to synthetic and natural food antioxidants. J. Food Qual. 2012, 35, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC. Method 978.04, 925.18, 925.19, and 923.03. In Official Method of Analysis, 18th ed.; Association of Officiating Analytical Chemists: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

| Sage | CA [mg/g] | C [mg/g] | RA [mg/g] | Polyphenols [mg/g] | Flavonoids [mg/g] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1LC | 32.42 ± 0.67 a | 4.45 ± 0.31 b | 19.6 ± 0.75 bc | 124.3 ± 2.5 b | 16.8 ± 0.5 a |

| 2LC | 8.52 ± 0.15 k | 1.81 ± 0.06 d | 20.6 ± 0.60 b | 111.6 ± 6.6 c | 13.8 ± 0.4 c |

| 3LC | 12.11 ± 2.10 d | 3.52 ± 0.17 c | 23.9 ± 2.34 a | 117.3 ± 6.5 bc | 16.1 ± 1.1 ab |

| 4BC | 1.89 ± 0.05 l | nd | 6.2 ± 0.43 h | 58.7 ± 2.0 g | 7.1 ± 0.1 f |

| 5BC | 15.99 ± 0.39 c | 3.34 ± 0.47 c | 9.9 ± 0.30 g | 92.0 ± 1.8 d | 12.3 ± 0.3 d |

| 6LE | 23.60 ± 0.82 b | 9.06 ± 0.94 a | 14.9 ± 0.82 d | 135.2 ± 2.9 a | 18.2 ± 0.5 h |

| 7LC | 9.72 ± 1.01 e | 1.85 ± 0.04 d | 12.1 ± 1.21 f | 48.1 ± 4.3 h | 13.9 ± 0.6 c |

| 8LE | 5.70 ± 0.06 g | 1.85 ± 0.03 d | 19.2 ± 0.77 c | 64.4 ± 1.0 f | 12.9 ± 0.6 d |

| 9LC | 7.00 ± 0.05 f | 1.58 0.08 e | 3.8 ± 0.32 i | 33.8 ± 1.3 i | 10.2 ± 0.9 ei |

| 10BE | 2.98 ± 0.02 j | nd | 14.6 ± 1.52 d | 54.9 ± 6.2 gh | 11.4 ± 1.5 id |

| 11BC | 4.67 ± 0.03 i | 1.85 ± 0.05 d | 13.0 ± 1.19 df | 49.9 ± 8.0 h | 15.3 ± 1.2 b |

| 12BC | 1.25 ± 0.01 m | 0.95 ± 0.03 f | 3.2 ± 0.31 i | 26.1 ± 2.9 i | 4.8 ± 0.3 g |

| 13LE | 5.12 ± 0.02 h | nd | 14.5 ± 0.64 d | 96.7 ± 6.0 d | 9.9 ± 0.6 e |

| Average | 10.1 | 2.2 | 15.1 | 77.9 | 12.5 |

| Sage | Moisture (%) | Protein (%) | Fat (%) | Ash (%) | Carbohydrates (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1LC | 6.77 ± 0.34 c | 11.25 ± 0.75 c | 11.15 ± 0.40 bcd | 9.27 ± 0.27 c | 61.57 ± 1.42 b |

| 2LC | 7.01 ± 0.29 c | 14.55 ± 0.47 b | 8.07 ± 0.57 ef | 13.13 ± 0.08 ab | 57.24 ± 0.46 c |

| 3LC | 10.01 ± 0.47 b | 16.13 ± 0.10 a | 11.47 ± 0.66 ab | 10.48 ± 0.19 c | 51.92 ± 0.89 d |

| 4BC | 6.58 ± 0.35 c | 10.63 ± 0.30 c | 6.63 ± 0.06 f | 9.08 ± 0.04 c | 67.07 ± 0.27 a |

| 5BC | 9.82 ± 0.49 b | 11.94 ± 0.75 c | 9.81 ± 0.26 d | 9.19 ± 0.17 c | 59.25 ± 0.83 bc |

| 6LE | 10.87 ± 0.11 b | 10.43 ± 0.18 c | 12.65 ± 0.76 a | 7.85 ± 0.36 d | 58.20 ± 1.02 c |

| 7LC | 12.68 ± 0.45 a | 16.20 ± 0.50 a | 8.73 ± 0.40 de | 12.57 ± 0.09 ab | 49.82 ± 0.43 |

| 8LE | 12.10 ± 0.55 a | 11.32 ± 0.21 c | 8.44 ± 0.50 de | 9.57 ± 0.55 c | 58.58 ± 1.56 c |

| 9LC | 10.55 ± 0.61 b | 13.54 ± 0.34 b | 9.42 ± 0.07 de | 12.03 ± 0.46 b | 54.45 ± 1.05 d |

| 10BE | 12.72 ± 0.45 a | 7.36 ± 0.27 e | 9.87 ± 0.37 de | 7.61 ± 0.02 d | 62.45 ± 0.67 b |

| 11BC | 12.4 6 ± 0.53 a | 14.69 ± 0.74 ab | 7.57 ± 0.42 ef | 11.93 ± 0.21 b | 53.36 ± 1.38 d |

| 12BC | 13.22 ± 0.28 a | 8.90 ± 0.67 d | 6.21 ± 0.84 f | 11.84 ± 0.09 b | 59.84 ± 0.94 bc |

| 13LE | 12.32 ± 0.13 a | 10.93 ± 1.12 c | 8.98 ± 0.40 de | 13.41 ± 1.25 a | 54.36 ± 2.44 d |

| Sage Code | Company Code | Country of Origin | Form | Part of the Plant | Type of Cultivation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1LC | 1 | No information | Loose | Cut sage | Conventional |

| 2LC | 2 | No information | Loose | Leaf | Conventional |

| 3LC | 3 | No information | Loose | Leaf | Conventional |

| 4BC | 4 | No information | Bag | Leaf | Conventional |

| 5BC | 5 | No information | Bag | Leaf | Conventional |

| 6LE | 6 | Bosnia and Herzegovina | Loose | Leaf | Ecological |

| 7LC | 7 | Poland | Loose | Leaf | Conventional |

| 8LE | 8 | Poland | Loose | Herb | Ecological |

| 9LC | 9 | No information | Loose | Leaf | Conventional |

| 10BE | 10 | Poland | Bag | Leaf | Ecological |

| 11BC | 11 | No information | Bag | Leaf | Conventional |

| 12BC | 12 | No information | Bag | Herb | Conventional |

| 13LE | 10 | Poland | Loose | Leaf | Ecological |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hrebień-Filisińska, A.M.; Felisiak, K.; Tokarczyk, G.; Czachura, Z.; Kiliański, K. Content of Carnosic Acid, Carnosol, Rosmarinic Acid, and Proximate Composition in an Assortment of Dried Sage (Salvia officinalis L.). Molecules 2025, 30, 4569. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234569

Hrebień-Filisińska AM, Felisiak K, Tokarczyk G, Czachura Z, Kiliański K. Content of Carnosic Acid, Carnosol, Rosmarinic Acid, and Proximate Composition in an Assortment of Dried Sage (Salvia officinalis L.). Molecules. 2025; 30(23):4569. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234569

Chicago/Turabian StyleHrebień-Filisińska, Agnieszka M., Katarzyna Felisiak, Grzegorz Tokarczyk, Zuzanna Czachura, and Kacper Kiliański. 2025. "Content of Carnosic Acid, Carnosol, Rosmarinic Acid, and Proximate Composition in an Assortment of Dried Sage (Salvia officinalis L.)" Molecules 30, no. 23: 4569. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234569

APA StyleHrebień-Filisińska, A. M., Felisiak, K., Tokarczyk, G., Czachura, Z., & Kiliański, K. (2025). Content of Carnosic Acid, Carnosol, Rosmarinic Acid, and Proximate Composition in an Assortment of Dried Sage (Salvia officinalis L.). Molecules, 30(23), 4569. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234569