The Skin Microbiome and Bioactive Compounds: Mechanisms of Modulation, Dysbiosis, and Dermatological Implications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Functions of the Skin Microbiome

3. Dysbiosis and Skin Disorders

3.1. Acne

3.2. Atopic Dermatitis (AD)

3.3. Psoriasis

3.4. Rosacea

3.5. Chronic Wounds

3.6. Seborrheic Dermatitis (SD) and Dandruff

3.7. Vitiligo

3.8. Alopecia Areata (AA)

3.9. Itch

3.10. Eczema

3.11. Carcinogenesis

| Disease | Association with the Skin Microbiome and Consequence | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Acne vulgaris | ↑ C. acnes (pro-inflammatory strains RT4/RT5), ↓ S. epidermidis Consequences: excessive TLR2 stimulation, production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, biofilm formation, inflammation of hair follicles. | [58,59,60,61] |

| Atopic Dermatitis | ↓ diversity, dominance of S. aureus (superantigens, toxins), ↓ S. epidermidis, ↓ C. acnes Consequences: epidermal barrier disruption, enhanced Th2/IgE response, chronic inflammation; excessive S. epidermidis growth may also act pathogenically | [29,62,63,64] |

| Psoriasis | Microbiome changes: ↑ Streptococcus spp., ↑ Malassezia spp., ↓ Cutibacterium Consequences: dysbiosis activation of dendritic cells, predominance of Th17/IL-23 response, exacerbation of skin inflammation. | [65] |

| Rosacea | Microbiome changes: ↑ Demodex folliculorum, ↑ Heyndrickxia oleronia, ↓ C. acnes Consequences: TLR2 activation, induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-8, TNF-α), neutrophil recruitment, overexpression of LL-37/KLK5 chronic inflammation, papules, and pustules. | [34,35,66] |

| Chronic wounds/DFU | Microbiome changes: pathogenic biofilm (S. aureus, P. aeruginosa), ↓ protective flora; presence of Porphyromonas, Streptococcus, Peptostreptococcus, Sphingomonas, Stenotrophomonas, Anaerococcus, Staphylococcus, Corynebacterium. Consequences: disruption of the wound-site microbiome balance, chronic inflammation, delayed healing. | [13,17,18] |

| SD/dandruff | Microbiome changes: ↑ Malassezia restricta, ↓ Malassezia globosa, ↓ commensal bacteria (Cutibacterium, S. epidermidis). Consequences: increased production of irritating and pro-inflammatory metabolites (unsaturated fatty acids, indoles), AhR activation, epidermal barrier disruption, increased TEWL, and exacerbation of inflammation. | [39,40,41] |

| Sebaceous folliculitis | ↑ Malassezia spp. | [67] |

| Vitiligo | Microbiome changes: dysbiosis, ↓ microbiome diversity in vitiligo lesions; ↓ Corynebacterium (healthy skin), ↑ Flavobacteriales, ↑ Gammaproteobacteria, ↑ Flavobacteria. Consequences: the specific microbiota composition in vitiligo may influence disease progression and the persistence of inflammation. | [42] |

| Alopecia areata | Microbiome changes: imbalance of the hair follicle microbiome; ↑ C. acnes, ↓ S. epidermidis; ↓ microbial diversity. Consequences: loss of homeostasis, modulation of immune response, exacerbation of perifollicular inflammation; potential links with the gut microbiome. | [43,44,45,46] |

| Pruritus/Itch | Microbiome changes: ↓ commensals (S. epidermidis, C. acnes), ↑ S. aureus (proteases, toxins). Consequences: barrier disruption, ↑ pathogenic biofilm, activation of PAR-1/PAR-2 on sensory neurons, overproduction of β-defensins (pruritogenic effect), ↑ TLR3/TSLP signaling -chronic inflammation and persistent itch. | [9,47,48,49,50,51,52,53] |

| Eczema | Microbiome changes: ↑ S. aureus, ↓ microbial diversity; presence of profiles enriched in Streptococcus, Gemella, Haemophilus. Consequences: dysbiosis promotes pathogen colonization, skin barrier impairment, and inflammation development. | [6,54] |

| AK | Microbiome changes: decrease in C. acnes (especially protective strains) and S. epidermidis; increase in S. aureus. Consequences: dysbiosis appears already in AK and correlates with progression to SCC | [22,55] |

| SCC | Microbiome changes: ↑ S. aureus (biofilm, toxins, inflammation), ↓ commensals (C. acnes, S. epidermidis). Consequences: dysbiosis promotes progression from AK to SCC; exacerbated inflammation, increased β-defensin-2 expression, impaired immune response. | [55,56,68,69,70] |

| MM | Microbiome changes: ↑ Corynebacterium, Fusobacterium, Streptococcus, Trueperella, Bacteroides. Consequences: dysbiosis correlates with disease progression; Corynebacterium is associated with an increase in IL-17–producing T cells. | [14,56,57,71] |

| Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) | Dysbiosis with S. aureus dominance (virulent strains, spa/NF-κB) is associated with poorer prognosis ↓ event-free survival. AMPs enhance inflammation and select for pathogens. Commensals (S. epidermidis, S. hominis) may act protectively. The skin microbiome holds potential as a prognostic marker and therapeutic target. | [72] |

| BCC | Microbiome changes: decrease in C. acnes and S. epidermidis; increase in pathogens (S. aureus). Consequences: dysbiosis may contribute to BCC development through chronic inflammation and impaired immune response. | [14,55,56] |

4. Factors Disrupting the Balance of the Skin Microbiome

4.1. Cosmetics

4.2. Surfactants

4.3. Microplastics

4.4. Antibiotics

4.5. Dermatological Procedures

4.6. Ultraviolet (UV) Radiation

4.7. Air Pollution

4.8. Place of Residence

4.9. Excessive Hygiene

4.10. Age and Skin Aging

4.11. Chronic Stress

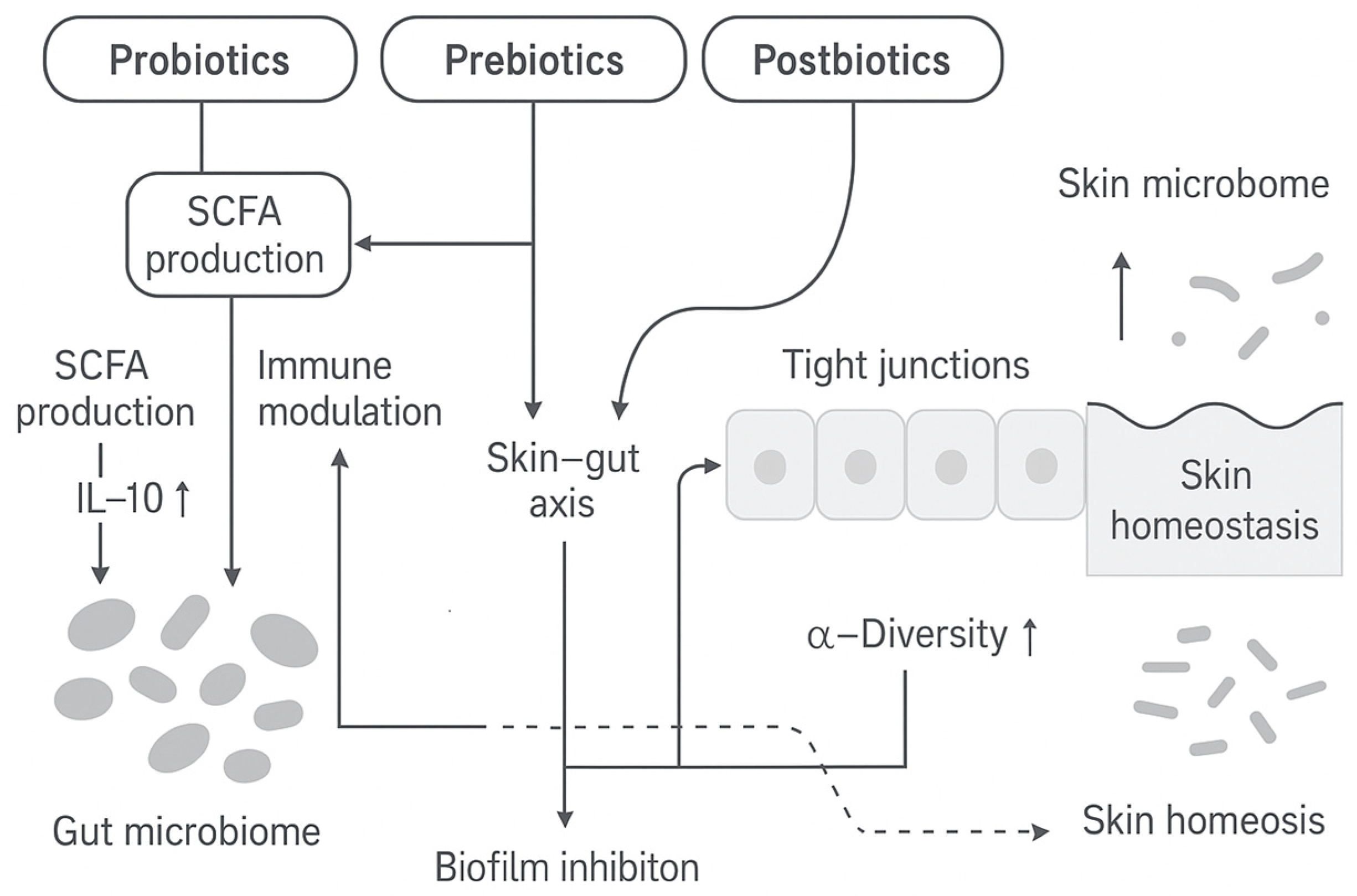

5. Strategies for Microbiome-Friendly Intervention

5.1. Probiotics

5.2. Prebiotics

5.2.1. Oligosaccharides

5.2.2. Algal Oligosaccharides

5.2.3. Pectic and Starch Oligosaccharides

5.2.4. Chitosan Oligosaccharides

5.2.5. Milk Oligosaccharides

5.2.6. Inulin (Fructooligosaccharides) (FOS)

5.2.7. Gluco-Oligosaccharides (GlcOs)

5.2.8. Oat (Avena sativa L.)—Beta-Glucan

5.3. Postbiotics

5.3.1. Fermented Oils

5.3.2. Fermented Sugarcane Straw (Saccharum officinarum L.)

5.4. Microbiome-Friendly Cosmeceuticals

5.4.1. Botanical Extracts

Rhodomyrtus tomentosa (Aiton) Hassk.

Halymenia durvillei

Mangifera indica L.

Symphytum officinale L.

Calendula officinalis L. and Arnica montana L.

Centella asiatica (L.) Urb.

Hamamelis virginiana L.

Camellia sinensis (L.) Kuntze

Punica granatum L.

Selenicereus undatus (Haw.) D.R.Hunt (Pitahja)

Solanum lycopersicum L.

Myristica fragrans Houtt.

Ribes nigrum L.

5.4.2. Thermal Water

5.4.3. Biosurfactants

5.5. Animal-Derived Substances

5.5.1. Honey

5.5.2. Propolis

5.5.3. Royal Jelly

5.5.4. Beeswax

5.5.5. Pollen and Bee Bread

5.5.6. Snail Mucin

5.5.7. Chitosan

Mechanistic Boxes (By Compound Class)

6. Interplay with the Gut–Skin Axis

7. Examples of Commercial Ingredients Supporting the Skin Microbiome

8. Research Gaps and Future Directions

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Deng, T.; Zheng, H.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, M.; He, G.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wu, J.; Cheng, H. Emerging trends and focus in human skin microbiome over the last decade: A bibliometric analysis and literature review. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2023, 16, 2153–2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona-Cruz, S.; Orozco-Covarrubias, L.; Sáez-de-Ocariz, M. The human skin microbiome in selected cutaneous diseases. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 834135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scharschmidt, T.C.; Segre, J.A. Skin microbiome and dermatologic disorders. J. Clin. Investig. 2025, 135, e184315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skowron, K.; Bauza-Kaszewska, J.; Kraszewska, Z.; Wiktorczyk-Kapischke, N.; Grudlewska-Buda, K.; Kwiecińska-Piróg, J.; Wałecka-Zacharska, E.; Radtke, L.; Gospodarek-Komkowska, E. Human skin microbiome: Impact of intrinsic and extrinsic factors on skin microbiota. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.-J.; Kim, M. Skin barrier function and the microbiome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Koh, Y.-S. The role of skin microbiome in human health and diseases. J. Bacteriol. Virol. 2024, 54, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polak, K.; Jobbágy, A.; Muszyński, T.; Wojciechowska, K.; Frątczak, A.; Bánvölgyi, A.; Bergler-Czop, B.; Kiss, N. Microbiome modulation as a therapeutic approach in chronic skin diseases. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haykal, D.; Cartier, H.; Dréno, B. Dermatological health in the light of skin microbiome evolution. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2024, 23, 3836–3846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Hunt, R.L.; Villaruz, A.E.; Fisher, E.L.; Liu, R.; Liu, Q.; Cheung, G.Y.C.; Li, M.; Otto, M. Commensal Staphylococcus epidermidis contributes to skin barrier homeostasis by generating protective ceramides. Cell Host Microbe 2022, 30, 301–313.e309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferček, I.; Lugović-Mihić, L.; Tambić-Andrašević, A.; Ćesić, D.; Grginić, A.G.; Bešlić, I.; Mravak-Stipetić, M.; Mihatov-Štefanović, I.; Buntić, A.M.; Čivljak, R. Features of the skin microbiota in common inflammatory skin diseases. Life 2021, 11, 962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sroczyńska, M.; Łuchowska, A.; Żaczek, A. Exploring the use of probiotics in dermatology—A literature review. J. Educ. Health Sport 2023, 13, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munteanu, C.; Turti, S.; Marza, S.M. Unraveling the gut-skin axis: The role of microbiota in skin health and disease. Cosmetics 2025, 12, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrd, A.L.; Belkaid, Y.; Segre, J.A. The human skin microbiome. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, B.K.; Bae, J.; Kim, D.; Huh, C.H.; Cho, K.H. The human microbiota and skin cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.; Cogen, A.L.; Radek, K.A.; Park, H.J.; MacLeod, D.T.; Leichtle, A.; Ryan, A.F.; Di Nardo, A.; Gallo, R.L. Activation of TLR2 by a small molecule produced by Staphylococcus epidermidis increases antimicrobial defense against bacterial skin infections. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2010, 130, 2211–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, T.; Glatz, M.; Horiuchi, K.; Kawasaki, H.; Akiyama, H.; Kaplan, D.H.; Kong, H.H.; Amagai, M.; Nagao, K. Dysbiosis and Staphylococcus aureus colonization drives inflammation in atopic dermatitis. Immunity 2015, 42, 756–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanford, J.A.; Gallo, R.L. Functions of the skin microbiota in health and disease. Semin. Immunol. 2013, 25, 370–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belkaid, Y.; Segre, J.A. Dialogue between skin microbiota and immunity. Science 2014, 346, 954–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Kopylova, E.; Mao, J.; Namkoong, J.; Sanders, J.; Wu, J. Microbiome and lipidomic analysis reveal the interplay between skin bacteria and lipids in a cohort study. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1383656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nodake, Y.; Matsumoto, S.; Miura, R.; Honda, H.; Ishibashi, G.; Matsumoto, S.; Dekio, I.; Sakakibara, R. Pilot study on novel skin care method by augmentation with Staphylococcus epidermidis, an autologous skin microbe—A blinded randomized clinical trial. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2015, 79, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohshima, H.; Kurosumi, M.; Kanto, H. New solution of beauty problem by Staphylococcus hominis: Relevance between skin microbiome and skin condition in healthy subject. Skin Res. Technol. 2021, 27, 692–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakatsuji, T.; Chen, T.H.; Narala, S.; Chun, K.A.; Two, A.M.; Yun, T.; Shafiq, F.; Kotol, P.F.; Bouslimani, A.; Melnik, A.V.; et al. Antimicrobials from human skin commensal bacteria protect against Staphylococcus aureus and are deficient in atopic dermatitis. Sci. Transl. Med. 2017, 9, eaah4680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrowski, J.; Chlebus, E.; Bednarski, I. Menopause and the skin microbiome: A review of the current knowledge. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratanapokasatit, Y.; Laisuan, W.; Rattananukrom, T.; Petchlorlian, A.; Thaipisuttikul, I.; Sompornrattanaphan, M. How Microbiomes Affect Skin Aging: The Updated Evidence and Current Perspectives. Life 2022, 12, 936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niedźwiedzka, A.; Micallef, M.P.; Biazzo, M.; Podrini, C. The Role of the Skin Microbiome in Acne: Challenges and Future Therapeutic Opportunities. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.B.; Byun, E.J.; Kim, H.S. Potential Role of the Microbiome in Acne: A Comprehensive Review. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, C.T.; Lancien, U.; Corvec, S.; Mengeaud, V.; Mias, C.; Véziers, J.; Khammari, A.; Dréno, B. Pro-Inflammatory Activity of Cutibacterium acnes Phylotype IA1 and Extracellular Vesicles: An In Vitro Study. Exp. Dermatol. 2024, 33, e15150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edslev, S.M.; Olesen, C.M.; Stegger, M.; Do, T.N.; Kwok, C.K.; Vestergaard, M.; Andersen, P.S.; Jemec, G.B.E. Staphylococcal Communities on Skin Are Associated with Atopic Dermatitis and Disease Severity. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjerre, R.D.; Holm, J.B.; Palleja, A.; Sølberg, J.; Skov, L.; Johansen, J.D. Skin Dysbiosis in the Microbiome in Atopic Dermatitis Is Site-Specific and Involves Bacteria, Fungus and Virus. BMC Microbiol. 2021, 21, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Hülpüsch, C.; Traidl-Hoffmann, C.; Reiger, M.; Schloter, M. Understanding the Role of Staphylococcus aureus in Atopic Dermatitis: Strain Diversity, Microevolution, and Prophage Influences. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1480257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stehlikova, Z.; Kostovcik, M.; Kostovcikova, K.; Kverka, M.; Juzlova, K.; Rob, F.; Hercogova, J.; Bohac, P.; Pinto, Y.; Uzan, A.; et al. Dysbiosis of Skin Microbiota in Psoriatic Patients: Co-Occurrence of Fungal and Bacterial Communities. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radaschin, D.S.; Tatu, A.; Iancu, A.V.; Beiu, C.; Popa, L.G. The Contribution of the Skin Microbiome to Psoriasis Pathogenesis and Its Implications for Therapeutic Strategies. Medicina 2024, 60, 1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celoria, V.; Rosset, F.; Pala, V.; Dapavo, P.; Ribero, S.; Quaglino, P.; Mastorino, L. The Skin Microbiome and Its Role in Psoriasis: A Review. Psoriasis: Targets Ther. 2023, 13, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, W.; Hamblin, M.R.; Wen, X. Role of the Skin Microbiota and Intestinal Microbiome in Rosacea. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1108661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Pellicer, P.; Eguren-Michelena, C.; García-Gavín, J.; Llamas-Velasco, M.; Navarro-Moratalla, L.; Núñez-Delegido, E.; Agüera-Santos, J.; Navarro-López, V. Rosacea, Microbiome and Probiotics: The Gut-Skin Axis. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1323644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonel, C.; Sena, I.F.G.; Silva, W.N.; Prazeres, P.H.D.M.; Fernandes, G.R.; Mancha Agresti, P.; Martins Drumond, M.; Mintz, A.; Azevedo, V.A.C.; Birbrair, A. Staphylococcus epidermidis Role in the Skin Microenvironment. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2019, 23, 5949–5955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Versey, Z.; da Cruz Nizer, W.S.; Russell, E.; Zigic, S.; DeZeeuw, K.G.; Marek, J.E.; Overhage, J.; Cassol, E. Biofilm–Innate Immune Interface: Contribution to Chronic Wound Formation. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 648554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallo, I.; Sivori, F.; Mastrofrancesco, A.; Abril, E.; Pontone, M.; Di Domenico, E.G.; Pimpinelli, F. Bacterial Biofilm in Chronic Wounds and Possible Therapeutic Approaches. Biology 2024, 13, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prohic, A.; Sadikovic, T.J.; Krupalija-Fazlic, M.; Kuskunovic-Vlahovljak, S. Malassezia Species in Healthy Skin and in Dermatological Conditions. Int. J. Dermatol. 2016, 55, 494–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, R.; Li, R.; Wang, R. Skin Microbiome Alterations in Seborrheic Dermatitis and Dandruff: A Systematic Review. Exp. Dermatol. 2021, 30, 1546–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednarek, M.; Musiał, C. Mikrobiom Owłosionej Skóry Głowy—Aspekty Trychologiczne. Kosmetol. Estet. 2019, 8, 393–396. [Google Scholar]

- Ganju, P.; Nagpal, S.; Mohammed, M.H.; Kumar, P.N.; Pandey, R.; Natarajan, V.T.; Mande, S.S.; Gokhale, R.S. Microbial Community Profiling Shows Dysbiosis in the Lesional Skin of Vitiligo Subjects. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 18761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Migacz-Gruszka, K.; Branicki, W.; Obtulowicz, A.; Pirowska, M.; Gruszka, K.; Wojas-Pelc, A. What’s New in the Pathophysiology of Alopecia Areata? The Possible Contribution of Skin and Gut Microbiome in the Pathogenesis of Alopecia—Big Opportunities, Big Challenges, and Novel Perspectives. Int. J. Trichology 2019, 11, 185–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simakou, T.; Butcher, J.P.; Reid, S.; Henriquez, F.L. Alopecia Areata: A Multifactorial Autoimmune Condition. J. Autoimmun. 2019, 98, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juhasz, M.; Chen, S.; Khosrovi-Eghbal, A.; Ekelem, C.; Landaverde, Y.; Baldi, P.; Atanaskova Mesinkovska, N. Characterizing the Skin and Gut Microbiome of Alopecia Areata Patients. Ski. J. Cutan. Med. 2020, 4, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, D.; Sorbellini, E.; Marzani, B.; Rucco, M.; Giuliani, G.; Rinaldi, F. Scalp Bacterial Shift in Alopecia Areata. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0215206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, T.; Bilik, S.M.; Burke, O.M.; Pastar, I.; Yosipovitch, G. Host–Microbiome Interactions in Chronic Itch. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 5633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almoughrabie, S.; Cau, L.; Cavagnero, K.; O’Neill, A.M.; Li, F.; Roso-Mares, A.; Mainzer, C.; Closs, B.; Kolar, M.J.; Williams, K.J.; et al. Commensal Cutibacterium acnes Induce Epidermal Lipid Synthesis Important for Skin Barrier Function. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadg6262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, K.; O’Neill, A.M.; Williams, M.R.; Cau, L.; Nakatsuji, T.; Horswill, A.R.; Gallo, R.L. Short Chain Fatty Acids Produced by Cutibacterium acnes Inhibit Biofilm Formation by Staphylococcus epidermidis. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 21237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, P.Y.; Hoon, M.A. Specific β-Defensins Stimulate Pruritus through Activation of Sensory Neurons. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2022, 142, 594–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.S.; Yosipovitch, G. The Skin Microbiota and Itch: Is There a Link? J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, J.; Gallo, R.L. The Central Roles of Keratinocytes in Coordinating Skin Immunity. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2024, 144, 2377–2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, L.; Costa, F.; Blake, K.J.; Choi, S.; Chandrabalan, A.; Yousuf, M.S.; Shiers, S.; Dubreuil, D.; Vega-Mendoza, D.; Rolland, C.; et al. S. aureus Drives Itch and Scratch-Induced Skin Damage through a V8 Protease-PAR1 Axis. Cell 2023, 186, 5375–5393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prescott, S.L.; Larcombe, D.L.; Logan, A.C.; West, C.; Burks, W.; Caraballo, L.; Levin, M.; Van Etten, E.; Horwitz, P.; Kozyrskyj, A.; et al. The Skin Microbiome: Impact of Modern Environments on Skin Ecology, Barrier Integrity, and Systemic Immune Programming. World Allergy Organ. J. 2017, 10, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voigt, A.Y.; Emiola, A.; Johnson, J.S.; Fleming, E.S.; Nguyen, H.; Zhou, W.; Tsai, K.Y.; Fink, C.; Oh, J. Skin Microbiome Variation with Cancer Progression in Human Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2022, 142, 2773–2782.e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savoia, P.; Azzimonti, B.; Rolla, R.; Zavattaro, E. Role of the Microbiota in Skin Neoplasms: New Therapeutic Horizons. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.H.; Gwillim, E.; Patel, K.R.; Hua, T.; Rastogi, S.; Ibler, E.; Silverberg, J.I. Epidemiology of alopecia areata, ophiasis, totalis, and universalis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2020, 82, 675–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessinioti, C.; Katsambas, A.D. The Role of Propionibacterium acnes in Acne Pathogenesis: Facts and Controversies. Clin. Dermatol. 2010, 28, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claudel, J.-P.; Auffret, N.; Leccia, M.-T.; Poli, F.; Corvec, S.; Dréno, B. Staphylococcus epidermidis: A Potential New Player in the Physiopathology of Acne? Dermatology 2019, 235, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dréno, B.; Martin, R.; Moyal, D.; Henley, J.B.; Khammari, A.; Seité, S. Skin Microbiome and Acne Vulgaris: Staphylococcus, a New Actor in Acne. Exp. Dermatol. 2017, 26, 798–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coughlin, C.C.; Swink, S.M.; Horwinski, J.; Sfyroera, G.; Bugayev, J.; Grice, E.A.; Yan, A.C. The Preadolescent Acne Microbiome: A Prospective, Randomized, Pilot Study Investigating Characterization and Effects of Acne Therapy. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2017, 34, 661–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, H.H.; Oh, J.; Deming, C.; Conlan, S.; Grice, E.A.; Beatson, M.A.; Nomicos, E.; Polley, E.C.; Komarow, H.D.; NISC Comparative Sequence Program; et al. Temporal Shifts in the Skin Microbiome Associated with Disease Flares and Treatment in Children with Atopic Dermatitis. Genome Res. 2012, 22, 850–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henley, J.B.; Ing, R.M.M.; Zelenkova, H. Microbiome of Affected and Unaffected Skin of Patients with Atopic Dermatitis before and after Emollient Treatment. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2014, 13, 1365–1372. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, M.E.; Schaffer, J.V.; Orlow, S.J.; Gao, Z.; Li, H.; Alekseyenko, A.V.; Blaser, M.J. Cutaneous Microbiome Effects of Fluticasone Propionate Cream and Adjunctive Bleach Baths in Childhood Atopic Dermatitis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2016, 75, 481–493.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yerushalmi, M.; Elalouf, O.; Anderson, M.; Chandran, V. The Skin Microbiome in Psoriatic Disease: A Systematic Review and Critical Appraisal. J. Transl. Autoimmun. 2019, 2, 100009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, A.K.; Spaunhurst, K.; Sprockett, D.; Thomason, Y.; Mann, M.W.; Fu, P.; Ammons, C.; Gerstenblith, M.; Tuttle, M.S.; Popkin, D.L. Characterization of the Facial Microbiome in Twins Discordant for Rosacea. Exp. Dermatol. 2018, 27, 295–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velegraki, A.; Cafarchia, C.; Gaitanis, G.; Iatta, R.; Boekhout, T. Malassezia Infections in Humans and Animals: Pathophysiology, Detection, and Treatment. PLoS Pathog. 2015, 11, e1004523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kullander, J.; Forslund, O.; Dillner, J. Staphylococcus aureus and Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Skin. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2009, 18, 472–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, D.L.A.; Lachner, N.; Tan, J.-M.; Tang, S.; Angel, N.; Laino, A.; Linedale, R.; Lê Cao, K.-A.; Morrison, M.; Frazer, I.H. A Natural History of Actinic Keratosis and Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma Microbiomes. mBio 2018, 9, e01432-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhusudhan, N.; Pausan, M.R.; Halwachs, B.; Durdević, M.; Windisch, M.; Kehrmann, J.; Patra, V.; Wolf, P.; Boukamp, P.; Moissl-Eichinger, C. Molecular Profiling of Keratinocyte Skin Tumors Links Staphylococcus aureus Overabundance and Increased Human β-Defensin-2 Expression to Growth Promotion of Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cancers 2020, 12, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuhashi, I.; Kajihara, S.; Sawamura, S.; Kanemaru, H.; Makino, K.; Aoi, J.; Makino, T.; Masuguchi, S.; Fukushima, S.; Ihn, H. Skin Microbiome in Acral Melanoma: Corynebacterium Is Associated with Advanced Melanoma. J. Dermatol. 2021, 48, e15–e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licht, P.; Dominelli, N.; Kleemann, J.; Pastore, S.; Müller, E.-S.; Haist, M.; Hartmann, K.S.; Stege, H.; Bros, M.; Meissner, M.; et al. The Skin Microbiome Stratifies Patients with Cutaneous T Cell Lymphoma and Determines Event-Free Survival. Biofilms Microbiomes 2024, 10, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Belkum, A.; Lisotto, P.; Pirovano, W.; Mongiat, S.; Zorgani, A.; Gempeler, M.; Bongoni, R.; Klaassens, E. Being Friendly to the Skin Microbiome: Experimental Assessment. Front. Microbiomes 2023, 2, 1077151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriu, P.A.; Iker, B.; Malik, K.; Leung, H.; Mohn, W.W.; Hillebrand, G.G. New Insights into the Intrinsic and Extrinsic Factors That Shape the Human Skin Microbiome. mBio 2019, 10, e00839-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, B.M. Prevention and Control of Infections in Hospitals: Practice and Theory, 1st ed.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 337–437. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, B.K.; Lee, S.; Myoung, J.; Hwang, S.J.; Lim, J.M.; Jeong, E.T.; Park, S.G.; Youn, S.H. Effect of the Skincare Product on Facial Skin Microbial Structure and Biophysical Parameters: A Pilot Study. MicrobiologyOpen 2021, 10, e1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puebla-Barragan, S.; Reid, G. Probiotics in Cosmetic and Personal Care Products: Trends and Challenges. Molecules 2021, 26, 1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouslimani, A.; da Silva, R.; Kosciolek, T.; Janssen, S.; Callewaert, C.; Amir, A.; Dorrestein, K.; Melnik, A.V.; Zaramela, L.S.; Kim, J.-N.; et al. The Impact of Skin Care Products on Skin Chemistry and Microbiome Dynamics. BMC Biol. 2019, 17, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fourniere, M.; Latire, T.; Souak, D.; Feuilloley, M.G.J.; Bedoux, G. Staphylococcus epidermidis and Cutibacterium acnes: Two Major Sentinels of Skin Microbiota and the Influence of Cosmetics. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, D.; Ciardiello, T.; Franzoni, M.; Pasini, F.; Giuliani, G.; Rinaldi, F. Effect of Commonly Used Cosmetic Preservatives on Skin Resident Microflora Dynamics. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 8695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, X.; Zhao, L.; Gu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Liu, N.; An, L.; Lu, Y.; Cui, S. Effect of Leave-On Cosmetic Antimicrobial Preservatives on Healthy Skin Resident Staphylococcus epidermidis. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2023, 22, 2115–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Cui, S.; Zhou, L.; He, K.; Song, L.; Liang, H.; He, C. Effect of Cosmetic Chemical Preservatives on Resident Flora Isolated from Healthy Facial Skin. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2019, 18, 652–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mim, M.F.; Sikder, M.H.; Chowdhury, M.Z.H.; Bhuiyan, A.-U.-A.; Zinan, N.; Islam, S.M.N. The Dynamic Relationship between Skin Microbiomes and Personal Care Products: A Comprehensive Review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e15–e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, D.; Kim, H. Effects of Cosmetics and Their Preservatives on the Growth and Composition of Human Skin Microbiota. J. Soc. Cosmet. Sci. Korea 2015, 41, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, B.; Hoptroff, M.; Arnold, D.; Eccles, R.; Campbell-Lee, S. In-Vivo Impact of Common Cosmetic Preservative Systems in Full Formulation on the Skin Microbiome. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0254172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobler, D.; Schmidts, T.; Wildenhain, S.; Seewald, I.; Merzhäuser, M.; Runkel, F. Impact of Selected Cosmetic Ingredients on Common Microorganisms of Healthy Human Skin. Cosmetics 2019, 6, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssens-Böcker, C.; Doberenz, C.; Monteiro, M.; de Oliveira Ferreira, M. Influence of Cosmetic Skincare Products with pH < 5 on the Skin Microbiome: A Randomized Clinical Evaluation. Dermatol. Ther. 2025, 15, 141–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korting, H.C.; Hübner, K.; Greiner, K.; Hamm, G.; Braun-Falco, O. Differences in the Skin Surface pH and Bacterial Microflora Due to the Long-Term Application of Synthetic Detergent Preparations of pH 5.5 and pH 7.0. Results of a Crossover Trial in Healthy Volunteers. Acta Derm.-Venereol. 1990, 70, 429–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rippke, F.; Berardesca, E.; Weber, T.M. pH and Microbial Infections. In pH of the Skin: Issues and Challenges; S. Karger AG: Basel, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 54, pp. 87–94. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H.; Yu, F.; Wang, C.; Han, Z.; Liu, S.; Chen, D.; Liu, D.; Meng, X.; He, X.; Huang, Z. The Impacts of Sodium Lauroyl Sarcosinate in Facial Cleanser on Facial Skin Microbiome and Lipidome. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2024, 23, 1351–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aristizabal, M.; Jiménez-Orrego, K.V.; Caicedo-León, M.D.; Páez-Cárdenas, L.S.; Castellanos-García, I.; Villalba-Moreno, D.L.; Ramírez-Zuluaga, L.V.; Hsu, J.T.S.; Jaller, J.; Gold, M. Microplastics in Dermatology: Potential Effects on Skin Homeostasis. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2024, 23, 766–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treuel, L.; Brandholt, S.; Maffre, P.; Wiegele, S.; Shang, L.; Nienhaus, G.U. Impact of Protein Modification on the Protein Corona on Nanoparticles and Nanoparticle Cell Interactions. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 503–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.H.; Kim, H.S. Microplastics in Cosmetics: Emerging Risks for Skin Health and the Environment. Cosmetics 2025, 12, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, J.R.; Powell, E.J.; Tomasovic, L.M.; Marcheskie, R.L.; Girish, V.; Warman, A.; Sivaloganathan, D. Changes in the Skin Microbiome Following Dermatological Procedures: A Scoping Review. Appl. Microbiol. 2024, 4, 972–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.; Choi, J.Y.; Shin, J.-W.; Huh, C.-H.; Park, K.-C.; Du, M.-H.; Yoon, S.; Na, J.-I. Changes in Lesional and Non-Lesional Skin Microbiome During Treatment of Atopic Dermatitis. Acta Derm.-Venereol. 2019, 99, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lossius, A.H.; Sundnes, O.; Ingham, A.C.; Edslev, S.M.; Bjørnholt, J.V.; Lilje, B.; Bradley, M.; Asad, S.; Haraldsen, G.; Skytt-Andersen, P.; et al. Shifts in the Skin Microbiota after UVB Treatment in Adult Atopic Dermatitis. Dermatology 2022, 238, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Liu, L.; Zhou, L.; Chen, L.; Chen, X.; Xiong, X.; Deng, Y. The Effect of Intense Pulsed Light on the Skin Microbiota and Epidermal Barrier in Patients with Mild to Moderate Acne Vulgaris. Lasers Surg. Med. 2021, 53, 1348–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Ariyawati, A.; Chen, T.; Chen, J.; Liu, L.; Pu, Y.; Li, Y.; et al. Effect of 30% Supramolecular Salicylic Acid Peel on Skin Microbiota and Inflammation in Patients with Moderate-to-Severe Acne Vulgaris. Dermatol. Ther. 2023, 13, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Li, R.; Zhang, Q.; He, S.; Wang, Y. Antibacterial Effect and Possible Mechanism of Salicylic Acid Microcapsules against Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2022, 19, 12761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, V.; Laoubi, L.; Nicolas, J.-F.; Vocanson, M.; Wolf, P. A Perspective on the interplay of ultraviolet-radiation, skin microbiome and skin resident memory TCR+ Cells. Front. Med. 2018, 5, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Bai, X.; Peng, T.; Yi, X.; Luo, L.; Yang, J.; Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; He, T.; Wang, X.; et al. New Insights Into the Skin Microbial Communities and Skin Aging. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 565549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, E.M.; Ahmed, H.; Isedeh, P.N.; Kohli, I.; Van Der Pol, W.; Shaheen, A.; Muzaffar, A.F.; Al-Sadek, C.; Foy, T.M.; Abdelgawwad, M.S.; et al. Ultraviolet radiation, both UVA and UVB, influences the composition of the skin microbiome. Exp. Dermatol. 2019, 28, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harel, N.; Reshef, L.; Biran, D.; Brenner, S.; Ron, E.Z.; Gophna, U. Effect of Solar Radiation on Skin Microbiome: Study of Two Populations. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Air Pollution. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/air-pollution#tab=tab_2 (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Mancebo, S.; Wang, S. Recognizing the Impact of Ambient Air Pollution on Skin Health. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2015, 29, 2326–2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chueachavalit, C.; Meephansan, J.; Payungporn, S.; Sawaswong, V.; Chanchaem, P.; Wongpiyabovorn, J.; Thio, H.B. Comparison of Malassezia spp. Colonization between Human Skin Exposed to High- and Low-Ambient Air Pollution. Exp. Dermatol. 2022, 31, 1454–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ying, S.; Zeng, D.-N.; Chi, L.; Tan, Y.; Galzote, C.; Cardona, C.; Lax, S.; Gilbert, J.; Quan, Z.-X. The Influence of Age and Gender on Skin-Associated Microbial Communities in Urban and Rural Human Populations. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0141842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCall, L.-I.; Callewaert, C.; Zhu, Q.; Song, S.J.; Bouslimani, A.; Minich, J.J.; Ernst, M.; Ruiz-Calderon, J.F.; Cavallin, H.; Pereira, H.S.; et al. Home Chemical and Microbial Transitions across Urbanization. Nat. Microbiol. 2020, 5, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordain, L.; Lindeberg, S.; Hurtado, M.; Hill, K.; Eaton, S.B.; Brand-Miller, J. Acne Vulgaris: A Disease of Western Civilization. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2002, 138, 1584–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Urbanization Prospects: The 2018 Revision; (ST/ESA/SER.A/420); United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Li, B.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, W.; Jia, T.; Yang, J.; Song, L. Analysis of Microbial Composition in Different Dry Skin Areas of Beijing Women. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 10, 1504054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.Y.; You, S.W.; Gu, K.N.; Kim, H.J.; Shin, J.G.; Leem, S.; Hwang, B.K.; Kim, Y.; Kang, N.G. Longitudinal Study of the Interplay between the Skin Barrier and Facial Microbiome over 1 Year. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1298632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananthapadmanabhan, K.P.; Moore, D.J.; Subramanyan, K.; Misra, M.; Meyer, F. Cleansing without Compromise: The Impact of Cleansers on the Skin Barrier and the Technology of Mild Cleansing. Dermatol. Ther. 2004, 17 (Suppl. 1), 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.E.; Fischbach, M.A.; Belkaid, Y. Skin Microbiota–Host Interactions. Nature 2018, 553, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandegrift, R.; Bateman, A.C.; Siemens, K.N.; Nguyen, M.; Wilson, H.E.; Green, J.L. Cleanliness in Context: Reconciling Hygiene with a Modern Microbial Perspective. Microbiome 2017, 5, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesia, S.; Kononov, T.; Zahr, A.S. A Multi-Functional Anti-Aging Moisturizer Maintains a Diverse and Balanced Facial Skin Microbiome. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 133, 1791–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, B.; Bascom, C.C.; Hu, P.; Binder, R.L.; Fadayel, G.; Huggins, T.G.; Jarrold, B.B.; Osborne, R.; Rocchetta, H.L.; Swift, D.; et al. Aging-Associated Changes in the Adult Human Skin Microbiome and the Host Factors That Affect Skin Microbiome Composition. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2022, 142, 1934–1946.e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Fleming, E.; Legendre, G.; Roux, L.; Latreille, J.; Gendronneau, G.; Forestier, S.; Oh, J. Skin Microbiome Attributes Associate with Biophysical Skin Aging. Exp. Dermatol. 2023, 32, 1546–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, B.; Hoptroff, M.; Arnold, D.; Cawley, A.; Smith, L.; Adams, S.E.; Mitchell, A.; Horsburgh, M.J.; Hunt, J.; Dasgupta, B.; et al. Compositional Variations between Adult and Infant Skin Microbiome: An Update. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pistone, D.; Meroni, G.; Panelli, S.; D’Auria, E.; Acunzo, M.; Pasala, A.R.; Zuccotti, G.V.; Bandi, C.; Drago, L. A Journey on the Skin Microbiome: Pitfalls and Opportunities. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakin, E.; Yurku, K.; Ivanov, M.; Izotov, A.; Nakhod, V.; Pustovoyt, V. Regulation of Stress-Induced Immunosuppression in the Context of Neuroendocrine, Cytokine, and Cellular Processes. Biology 2025, 14, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, S.; Bouladoux, N.; Wilhelm, C.; Molloy, M.J.; Salcedo, R.; Kastenmuller, W.; Deming, C.; Quinones, M.; Koo, L.; Conlan, S.; et al. Compartmentalized Control of Skin Immunity by Resident Commensals. Science 2012, 337, 1115–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joint FAO/WHO Working Group. Guidelines for the Evaluation of Probiotics in Food. FAO/WHO londonon; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, C.; Guarner, F.; Reid, G.; Gibson, G.R.; Merenstein, D.J.; Pot, B.; Morelli, L.; Berni Canani, R.; Flint, H.J.; Salminen, S.; et al. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics Consensus Statement on the Scope and Appropriate Use of the Term Probiotic. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 11, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasbarrini, G.; Bonvicini, F.; Gramenzi, A. Probiotics history. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2016, 50, S116–S119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rušanac, A.; Škibola, Z.; Matijašić, M.; Čipčić Paljetak, H.; Perić, M. Microbiome-based products: Therapeutic potential for inflammatory skin diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 6745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, L.T.K.; Bushra, F.A.; Rattananon, P.; Rimi, A.A.; Lee, C.; Tahmid, S.M.; Tisha, S.A.; Jisan, I.F.; Das, R.; Sneha, J.I.; et al. Strategic antagonism: How Lactobacillus plantarum counters Staphylococcus aureus pathogenicity. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1635123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Marzio, L.; Centi, C.; Cinque, B.; Masci, S.; Giuliani, M.; Arcieri, A.; Zicari, L.; De Simone, C.; Cifone, M.G. Effect of the lactic acid bacterium Streptococcus thermophilus on stratum corneum ceramide levels and signs and symptoms of atopic dermatitis patients. Exp. Dermatol. 2003, 12, 615–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.B.; Im, M.; Lee, Y.; Lee, J.H.; Lim, J.; Park, Y.H.; Seo, Y.J. Effect of emollients containing vegetable-derived Lactobacillus in the treatment of atopic dermatitis symptoms: Split-body clinical trial. Ann. Dermatol. 2014, 26, 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchet-Rethore, S.; Bourdès, V.; Mercenier, A.; Haddar, C.H.; Verhoeven, P.O.; Andres, P. Effect of a lotion containing the heat-treated probiotic strain Lactobacillus johnsonii NCC 533 on Staphylococcus aureus colonization in atopic dermatitis. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2017, 10, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, É.; Lundqvist, C.; Axelsson, J. Lactobacillus reuteri DSM 17938 as a novel topical cosmetic ingredient: A proof of concept clinical study in adults with atopic dermatitis. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myles, I.A.; Castillo, C.R.; Barbian, K.D.; Kanakabandi, K.; Virtaneva, K.; Fitzmeyer, E.; Paneru, M.; Otaizo-Carrasquero, F.; Myers, T.G.; Markowitz, T.E.; et al. Therapeutic responses to roseomonas mucosa in atopic dermatitis may involve lipid-mediated tnf-related epithelial repair. Sci. Transl. Med. 2020, 12, eaaz8631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebeer, S.; Oerlemans, E.F.M.; Claes, I.; Henkens, T.; Delanghe, L.; Wuyts, S.; Spacova, I.; van den Broek, M.F.L.; Tuyaerts, I.; Wittouck, S.; et al. Selective targeting of skin pathobionts and inflammation with topically applied Lactobacilli. Cell Rep. Med. 2022, 3, 100521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biazzo, M.; Pinzauti, D.; Podrini, C. SkinDuo™ as a targeted probiotic therapy: Shifts in skin microbiota and clinical outcomes in acne patients. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, A.C.; Martins, S.M.D.S.B., Jr.; Belo, J.V.T.; Lemos, M.V.C.; Lima, C.E.M.C.; Silva, C.D.D.; Zagmignan, A.; Nascimento da Silva, L.C. Global trends and scientific impact of topical probiotics in dermatological treatment and skincare. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, G.R.; Hutkins, R.; Sanders, M.E.; Prescott, S.L.; Reimer, R.A.; Salminen, S.J.; Scott, K.; Stanton, C.; Swanson, K.S.; Cani, P.D.; et al. Expert consensus document: The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of prebiotics. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 14, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lolou, V.; Panayiotidis, M.I. Functional role of probiotics and prebiotics on skin health and disease. Fermentation 2019, 5, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knackstedt, R.; Knackstedt, T.; Gatherwright, J. The role of topical probiotics on skin conditions: A systematic review of animal and human studies and implications for future therapies. Exp. Dermatol. 2019, 5, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moskovicz, V.; Gross, A.; Mizrahi, B. Extrinsic factors shaping the skin microbiome. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodarzi, A.; Mozafarpoor, S.; Bodaghabadi, M.; Mohamadi, M. The potential of probiotics for treating acne vulgaris: A review of literature on acne and microbiota. Dermatol. Ther. 2020, 33, e13279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, L.; Li, T.; Yang, S.; Ma, L.; Cai, B.; Jia, Q.; Jiang, H.; Bai, T.; Li, Y. The prebiotic effects of fructooligosaccharides enhance the growth characteristics of Staphylococcus epidermidis and enhance the inhibition of Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2025, 47, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flowers, L.; Grice, E.A. The skin microbiota: Balancing risk and reward. Cell Host Microbe 2020, 28, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jesus Raposo, M.F.; De Morais, A.M.M.B.; De Morais, R.M.S.C. Emergent sources of prebiotics: Seaweeds and microalgae. Mar. Drugs 2016, 14, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morvan, P.Y.; Vallee, R. Evaluation of the Effects of stressful life on human skin microbiota. Appl. Microbiol. 2018, 4, 1000140. [Google Scholar]

- Fournière, M.; Bedoux, G.; Souak, D.; Bourgougnon, N.; Feuilloley, M.G.J.; Latire, T. Effects of Ulva sp. extracts on the growth, biofilm production, and virulence of skin bacteria microbiota: Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis, and Cutibacterium acnes strains. Molecules 2021, 26, 4763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusdi, B.; Ariyani, R.; Yuniarni, U. The effect of prebiotic starch and pectin from ambon banana peel (Musa acuminata AAA) on the growth of skin microbiota bacteria in vitro. Pharmacol. Clin. Pharm. Res. 2023, 8, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-H.; Eom, S.-H.; Yu, D.; Lee, M.-S.; Kim, Y.-M. Oligochitosan as a potential anti-acne vulgaris agent: Combined antibacterial effects against Propionibacterium acnes. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2017, 26, 1029–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Wang, X.; Zhang, P.; Li, B. Recent trends in human milk oligosaccharides: Newsynthesis technology, regulatory effects, and mechanisms of non-intestinal functions. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2025, 24, e70147. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Duan, F.Y.; Sun, T.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, L.L. Galactooligosaccharides: Synthesis, metabolism, bioactivities and food applications. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 6160–6176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortaz, E.; Nomani, M.; Adcock, I.; Folkerts, G.; Garssen, J. Galactooligosaccharides and 2-fucosyllactose can directly suppress growth of specific pathogenic microbes and affect phagocytosis of neutrophils. Nutrition 2022, 96, 111601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davani-Davari, D.; Negahdaripour, M.; Karimzadeh, I.; Seifan, M.; Mohkam, M.; Masoumi, S.J.; Berenjian, A.; Ghasemi, Y. Prebiotics: Definition, types, sources, mechanisms, and clinical applications. Foods 2019, 8, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abed, S.M.; Ali, A.H.; Noman, A.; Niazi, S.; Al-Farga, A.; Bakry, A.M. Inulin as prebiotics and its applications in food industry and human health: A review. Int. J. Agric. Innov. Res. 2016, 5, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Martinez, M.J.; Soto-Jover, S.; Antolinos, V.; Martinez-Hernandez, G.B.; Lopez-Gomez, A. Manufacturing of short-chain fructooligosaccharides: From laboratory to industrial scale. Food Eng. Rev. 2020, 12, 149–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, M.; van Pijkeren, J.P. Gluco-oligosaccharides as potential prebiotics: Synthesis, purification, structural characterization, and evaluation of prebiotic effect. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2023, 22, 2611–2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiyama, H.; Oono, T.; Huh, W.K.; Yamasaki, O.; Akagi, Y.; Uemura, H.; Yamada, T.; Iwatsuki, K. Actions of gluco-oligosaccharide against Staphylococcus aureus. J. Dermatol. 2002, 29, 580–586. [Google Scholar]

- Cerio, R.; Dohil, M.; Jeanine, D.; Magina, S.; Mahé, E.; Stratigos, A.J. Mechanism of action and clinical benefits of colloidal oatmeal for dermatologic practice. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2010, 9, 1116–1120. [Google Scholar]

- Reynertson, K.A.; Garay, M.; Nebus, J.; Chon, S.; Kaur, S.; Mahmood, K.; Kizoulis, M.; Southall, M.D. Anti-inflammatory activities of colloidal oatmeal (Avena sativa) contribute to the effectiveness of oats in treatment of itch associated with dry, irritated skin. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2015, 14, 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Liu-Walsh, F.; Tierney, N.K.; Hauschild, J.; Rush, A.K.; Masucci, J.; Leo, G.C.; Capone, K.A. Prebiotic colloidal oat supports the growth of cutaneous commensal bacteria including S. epidermidis and enhances the production of lactic Acid. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2021, 14, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capone, K.; Kirchner, F.; Klein, S.L.; Tierney, N.K. Effects of colloidal oatmeal topical atopic dermatitis cream on skin microbiome and skin barrier properties. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2020, 19, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theunis, J.; Chaussade, H.; Bourgeois, O.; Mengeaud, V. Efficacy of a Rhealba® Oat extract-based emollient on chronic pruritus in elderly french outpatients. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2017, 31 (Suppl. 1), 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salminen, S.; Collado, M.C.; Endo, A.; Hill, C.; Lebeer, S.; Quigley, E.M.M.; Sanders, M.E.; Shamir, R.; Swann, J.R.; Szajewska, H.; et al. The international scientific association of probiotics and prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of postbiotics. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 18, 649–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, M.; Oliveira, A.L.; Oliveira, C.; Pintado, M.; Amaro, A.; Madureira, A.R. current postbiotics in the cosmetic market: An update and development opportunities. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 106, 5879–5891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, M.; Carvalho, M.J.; Mota de Carvalho, N.; Azevedo-Silva, J.; Mendes, A.; Pinto Ribeiro, I.; Fernandes, J.C.; Oliveira, A.L.S.; Oliveira, C.; Pintado, M.; et al. Skincare potential of a sustainable postbiotic extract produced through sugarcane straw fermentation by Saccharomyces cerevisiae. BioFactors 2023, 49, 1038–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.H.; Kim, H.S. Skin Deep: The potential of microbiome cosmetics. J. Microbiol. 2024, 62, 181–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Guo, C.; Wang, Q.; Feng, C.; Duan, Z. A pilot study on the efficacy of topical lotion containing anti-acne postbiotic in subjects with mild-to-moderate acne. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 1064460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Feng, C.; Guo, C.; Duan, Z. Development of novel topical anti-acne cream containing postbiotics for mild-to-moderate acne. Indian J. Dermatol. 2022, 67, 667–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canchy, L.; Kerob, D.; Demessant, A.; Amici, J.M. Wound healing and microbiome, an unexpected relationship. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2023, 37, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Almeida, C.V.; Antiga, E.; Lulli, M. Oral and topical probiotics and postbiotics in skincare and dermatological therapy: A Concise Review. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciardiello, T.; Pinto, D.; Marotta, L.; Guliania, G. Effects of fermented oils on alpha-biodiversity and relative abundance of cheek resident skin microbiota. Cosmetics 2020, 7, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grumet, L.; Tromp, Y.; Stiegelbauer, V. The development of high-quality multispecies probiotic formulations: From bench to market. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodorou, I.M.; Kapoukranidou, D.; Theodorou, M.; Tsetis, J.K.; Menni, A.E.; Tzikos, G.; Bareka, S.; Shrewsbury, A.; Stavrou, G.; Kotzampassi, K. Cosmeceuticals: A review of clinical studies claiming to contain specific, well-characterized strains of probiotics or postbiotics. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beri, K. Perspective: Stabilizing the Microbiome Skin-Gut-Brain Axis with Natural Plant Botanical Ingredients in Cosmetics. Cosmetics 2018, 5, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhama, K.; Karthik, K.; Khandia, R.; Munjal, A.; Tiwari, R.; Rana, R.; Khurana, S.K.; Ullah, S.; Khan, R.U.; Alagawany, M.; et al. Medicinal and Therapeutic Potential of Herbs and Plant Metabolites/Extracts Countering Viral Pathogens—Current Knowledge and Future Prospects. Curr. Drug Metab. 2018, 19, 236–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Rahaman, M.S.; Islam, M.R.; Hossain, M.E.; Mithi, F.M.; Ahmed, M.; Saldías, M.; Küpeli Akkol, E.; Sobarzo-Sánchez, E. Multifunctional Therapeutic Potential of Phytocomplexes and Natural Extracts for Antimicrobial Properties. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Najjar, N.; Gali-Muhtasib, H.; Ketola, R.A.; Vuorela, P.; Urtti, A.; Vuorela, H. The Chemical and Biological Activities of Quinones: Overview and Implications in Analytical Detection. Phytochem. Rev. 2011, 10, 353–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farha, A.K.; Yang, Q.-Q.; Kim, G.; Li, H.-B.; Zhu, F.; Liu, H.-Y.; Gan, R.-Y.; Corke, H. Tannins as an Alternative to Antibiotics. Food Biosci. 2020, 38, 100751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholas-Haizelden, K.; Murphy, B.; Hoptroff, M.; Horsburgh, M.J. Bioprospecting the Skin Microbiome: Advances in Therapeutics and Personal Care Products. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBain, A.J.; O’Neill, C.A.; Amezquita, A.; Price, L.J.; Faust, K.; Tett, A.; Segata, N.; Swann, J.R.; Smith, A.M.; Murphy, B.; et al. Consumer Safety Considerations of Skin and Oral Microbiome Perturbation. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2019, 32, e00051-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamaria, E.; Åkerström, U.; Berger-Picard, N.; Lataste, S.; Gillbro, J.M. Randomized Comparative Double-Blind Study Assessing the Difference between Topically Applied Microbiome Supporting Skincare versus Conventional Skincare on the Facial Microbiome in Correlation to Biophysical Skin Parameters. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2023, 45, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sfriso, R.; Egert, M.; Gempeler, M.; Voegeli, R.; Campiche, R. Revealing the Secret Life of Skin—With the Microbiome You Never Walk Alone. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2019, 42, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojar, R.A. Studying the Human Skin Microbiome Using 3D In Vitro Skin Models. Appl. In Vitro Toxicol. 2015, 1, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, H.E.; Bhatia, N.D.; Friedman, A.; Eng, R.M.; Seite, S. The Role of Cutaneous Microbiota Harmony in Maintaining a Functional Skin Barrier. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2017, 16, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gervason, S.; Metton, I.; Gemrot, E.; Ranouille, E.; Skorski, G.; Cabannes, M.; Berthon, J.-Y.; Filaire, E. Rhodomyrtus tomentosa fruit extract and skin microbiota: A focus on C. acnes phylotypes in acne subjects. Cosmetics 2020, 7, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filaire, E.; Vialleix, C.; Cadoret, J.-P.; Dreux, A.; Berthon, J.-Y. ExpoZen®: An active ingredient modulating reactive and sensitive skin microbiota. Euro Cosmet. 2019, 9, 26–27. [Google Scholar]

- De Tollenaere, M.; Boira, C.; Chapuis, E.; Lapierre, L.; Jarrin, C.; Robe, P.; Zanchetta, C.; Vilanova, D.; Sennelier-Portet, B.; Martinez, J.; et al. Action of Mangifera indica leaf extract on acne-prone skin through sebum harmonization and targeting C. acnes. Molecules 2022, 27, 4769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnyk, N.; Popowski, D.; Strawa, J.W.; Przygodzińska, K.; Tomczyk, M.; Piwowarski, J.P.; Granica, S. Skin microbiota metabolism of natural products from comfrey root (Symphytum officinale L.). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 318, 116968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelletier-ahmed, L. Selective Inhibition of Propionibacterium acnes by Calendula officinalis: A Potential Role in Acne Treatment Through Modulation of the Skin Microbiome. Master’s Thesis, Middlesex University, London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Roopashree, T.S.; Dang, R.; Rani, H.R.; Narendra, C. Antibacterial activity of antipsoriatic herbs: Cassia tora, Momordica charantia and Calendula officinalis. Int. J. Appl. Res. Nat. Prod. 2008, 1, 20–28. [Google Scholar]

- Dahake, A.P.; Joshi, V.D.; Joshi, A.B. Antimicrobial screening of different extract of Anacardium occidentale Linn. Int. J. ChemTech Res. 2009, 1, 856–858. [Google Scholar]

- Safdar, W.; Majeed, H.; Naveed, I.; Kayani, W.K.; Ahmed, H.; Hussain, S.; Kamal, A. Pharmacognostical study of the medicinal plant Calendula officinalis L. (Family Compositae). Int. J. Cell Mol. Biol. 2010, 1, 108–116. [Google Scholar]

- Bikiaris, R.E.; Paczkowska-Walendowska, M.; Koumentakou, I.; Niti, A.; Cielecka-Piontek, J.; Kyzas, G.Z. Bioactivity and physicochemical characterization of Centella asiatica and Marigold extract serums: Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-tyrosinase and skin barrier function insights. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2025. online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasooly, R.; Howard, A.C.; Balaban, N.; Hernlem, B.; Apostolidis, E. The effect of tannin-rich witch hazel on growth of probiotic lactobacillus plantarum. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shill, D.D.; Stade, H.N.; Goodson, K.C.; Beltran, M.A.; Haller, D.; Benson, M.; Drumwright, M.D.; Scholz, D. Pleiotropic effects of a Camellia sinensis leaf extract on in vitro and in vivo skin health characteristics. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2025, 47, 835–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakkalakal, M.; Nadora, D.; Gahoonia, N.; Dumont, A.; Burney, W.; Pan, A.; Chambers, C.J.; Sivamani, R.K. Prospective randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study of oral pomegranate extract on skin wrinkles, biophysical features, and the gut-skin axis. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 6724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henning, S.M.; Yang, J.; Lee, R.-P.; Huang, J.; Hsu, M.; Thames, G.; Gilbuena, I.; Long, J.; Xu, Y.; Park, E.H.; et al. Pomegranate juice and extract consumption increases the resistance to UVB-induced erythema and changes the skin microbiome in healthy women: A randomized controlled trial. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 14528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havas, F.; Krispin, S.; Cohen, M.; Attia-Vigneau, J. A Hylocereus undatus extract enhances skin microbiota balance and delivers in-vivo improvements in skin health and beauty. Cosmetics 2024, 11, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkowska, K.; Otlewska, A.; Raczyk, A.; Maciejczyk, E.; Krajewska, A. Valorisation of tomato pomace in anti-pollution and microbiome-balance face cream. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 20516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oo, T.; Saiboonjan, B.; Mongmonsin, U.; Srijampa, S.; Srisrattakarn, A.; Tavichakorntrakool, R.; Chanawong, A.; Lulitanond, A.; Roytrakul, S.; Sutthanut, K.; et al. Effectiveness of co-cultured Myristica fragrans houtt. seed extracts with commensal Staphylococcus epidermidis and its metabolites in antimicrobial activity and biofilm formation of skin pathogenic bacteria. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2024, 24, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrov Ivanković, A.; Milivojević, A.; Ćorović, M.; Simović, M.; Banjanac, K.; Jansen, P.; Vukoičić, A.; van den Bogaard, E.; Bezbradica, D. In vitro evaluation of enzymatically derived blackcurrant extracts as prebiotic cosmetic ingredient: Extraction conditions optimization and effect on cutaneous microbiota representatives. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2023, 10, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćorović, M.; Petrov Ivanković, A.; Milivojević, A.; Pfeffer, K.; Homey, B.; Jansen, P.A.M.; Zeeuwen, P.L.J.M.; van den Bogaard, E.H.; Bezbradica, D. Investigating the effect of enzymatically-derived blackcurrant extract on skin Staphylococci using an in vitro human stratum corneum model. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selas, B. History of thermalism at avene-les-bains and genesis of the avene thermal spring water. Ann. Dermatol. Venereol. 2017, 144, S21–S26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourrain, M.; Villette, C.; Nguyen, T.; Lebaron, P. Aquaphilus dolomiae gen. nov., sp. nov., isolated from a deep aquifer. Vie Milieu 2012, 62, 191–195. [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero, D.; Garrigue, E. Avène’s thermal water and atopic dermatitis. Ann. Dermatol. Venereol. 2017, 144, S27–S34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aries, M.-F.; Hernandez-Pigeon, H.; Vaissière, C.; Delga, H.; Caruana, A.; Lévêque, M.; Bourrain, M.; Ravard Helffer, K.; Chol, B.; Nguyen, T.; et al. Anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects of Aquaphilus dolomiae extract on in vitro models. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2016, 9, 421–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.; Castex-Rizzi, N.; Redoulčs, D. Immunomodulatory, anti-inflammatory, anti-pruritus and tolerogenic activities induced by I-modulia®, an Aquaphilus dolomiae culture extract, in atopic dermatitis pharmacology models. Ann. Dermatol. Venereol. 2017, 144, S42–S49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deleuran, M.; Georgescu, V.; Jean-Decoster, C. An emollient containing Aquaphilus dolomiae extract is effective in the management of xerosis and pruritus: An international, real-world study. Dermatol. Ther. 2020, 10, 1013–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gueniche, A.; Valois, A.; Salomao Calixto, L.; Sanchez Hevia, O.; Labatut, F.; Kerob, D.; Nielsen, M. A dermocosmetic formulation containing Vichy volcanic mineralizing water, Vitreoscilla filiformis extract, niacinamide, hyaluronic acid, and vitamin E regenerates and repairs acutely stressed skin. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2022, 36, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varvaresou, V.A.; Iakovou, K. Biosurfactants in cosmetics and biopharmaceuticals. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2015, 61, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, M. Recognition and management of wound infections. World Wide Wounds 2004, 7, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Ong, P.Y. Recurrent MRSA skin infections in atopic dermatitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2014, 2, 396–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLoone, P.; Warnock, M.; Fyfe, L. Honey: A realistic antimicrobial for disorders of the skin. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2016, 49, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.T.; Rahman, R.A.; Gan, S.H.; Halim, A.S.; Hassan, S.A.; Sulaiman, S.A.; Kirnpal-Kaur, B.S. The antibacterial properties of malaysian tualang honey against wound and enteric microorganisms in comparison to manuka honey. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2009, 9, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, N.F.; Molan, P.C.; Harfoot, C.G. The sensitivity of dermatophytes to the antimicrobial activity of manuka honey and other honey. Pharm. Pharmacol. Commun. 1996, 2, 471–473. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, R.; Burton, N.; Cooper, R. Proteomic and genomic analysis of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) exposed to manuka honey in vitro demonstrated down regulation of virulence markers. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2014, 69, 603–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Park, J.H.; Kim, J.A.; Neupane, G.P.; Cho, M.H.; Lee, C.S.; Lee, J. Low concentrations of honey reduce biofilm formation, quorum sensing, and virulence in Escherichia coli O157:H7. Biofouling 2011, 27, 1095–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagh, V.D. Propolis: A wonder bees’ product and its pharmacological potentials. Adv. Pharmacol. Sci. 2013, 2013, 308249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybyłek, I.; Karpiński, T.M. Antibacterial properties of propolis. Molecules 2019, 24, 2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidel, V.; Peyfoon, E.; Watson, D.G.; Fearnley, J. Comparative study of the antibacterial activity of propolis from different geographical and climatic zones. Phytother. Res. 2008, 22, 1256–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albanese, G.; Giurgiu, A.I.; Bobiș, O.; Urcan, A.C.; Botezan, S.; Bonta, V.; Ternar, T.N.; Pașca, C.; Iorizzo, M.; De Cristofaro, A.; et al. Functional and antimicrobial properties of propolis from different areas of Romania. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bílikova, K.; Huang, S.C.; Lin, I.P.; Šimuth, J.; Peng, C.C. Structure and antimicrobial activity relationship of royalisin, an antimicrobial peptide from royal jelly of Apis mellifera. Peptides 2015, 68, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadan, M.F.; Al-Ghamdi, A. Bioactive compounds and health-promoting properties of royal jelly: A review. J. Funct. Foods 2012, 4, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fratini, F.; Cilia, G.; Turchi, B.; Felicioli, A. Beeswax: A minireview of its antimicrobial activity and its application in medicine. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2016, 9, 839–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komosinska-Vassev, K.; Olczyk, P.; Kaźmierczak, J.; Mencner, L.; Olczyk, K. Bee pollen: Chemical composition and therapeutic application. Evid -based complement. Altern. Med. 2015, 2015, 297425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascoal, A.; Rodrigues, S.; Teixeira, A.; Feás, X.; Estevinho, L.M. Biological activities of commercial bee pollens: Antimicrobial, antimutagenic, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2014, 63, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha, E.A. Chemical composition and biological activities of bee pollen. Nutrients 2019, 11, 849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, M.; Cerullo, A.R.; Parziale, J.; Achrak, E.; Sultana, S.; Ferd, J.; Samad, S.; Deng, W.; Braunschweig, A.B.; Holford, M. Discovery of snail mucins function and application. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 734023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, D.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, N.; Zhang, X.; Yan, C. Antimicrobial properties of chitosan and chitosan derivatives in the treatment of enteric infections. Molecules 2021, 26, 7136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmingsen, L.M.; Škalko-Basnet, N.; Jøraholmen, M.W. The expanded role of chitosan in localized antimicrobial therapy. Marine Drugs 2021, 19, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán, E.; Ortega, F.; Rubio, R.G. Chitosan: A promising multifunctional cosmetic ingredient for skin and hair care. Cosmetics 2022, 9, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champer, J.; Patel, J.; Fernando, N.; Salehi, E.; Wong, V.; Kim, J. Chitosan against cutaneous pathogens. AMB Express 2013, 3, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, C.; Soares, J.; Tavaria, F.; Duarte, A.; Correia, O.; Sokhatska, O.; Severo, M.; Silva, D.; Pintado, M.; Delgado, L.; et al. Chitosan-coated textiles may improve atopic dermatitis severity by modulating skin Staphylococcal Profile. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0142844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trifan, A.; Opitz, S.E.W.; Josuran, R.; Grubelnik, A.; Esslinger, N.; Peter, S.; Bräm, S.; Meier, N.; Wolfram, E. Is comfrey root more than toxic pyrrolizidine alkaloids? salvianolic acids among antioxidant polyphenols in comfrey (Symphytum officinale L.) roots. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2018, 112, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, M.; Chrubasik, S. Topical herbal therapies for treating osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 31, 1–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/tools-databases/cosing/details/100067 (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/tools-databases/cosing/details/84281 (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/tools-databases/cosing/details/83484 (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/tools-databases/cosing/details/55193 (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/tools-databases/cosing/details/99158 (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Mishra, A.; Chattopadhyay, P. Assessment of in vitro sun protection factor of Calendula officinalis L. (Asteraceae) essential oil formulation. J. Young Pharm. 2012, 4, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/tools-databases/cosing/details/93117 (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/tools-databases/cosing/details/74322 (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/tools-databases/cosing/details/97388 (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/tools-databases/cosing/details/75075 (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/tools-databases/cosing/details/98843 (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/tools-databases/cosing/details/55319 (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/tools-databases/cosing/details/99966 (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/tools-databases/cosing/details/82797 (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/tools-databases/cosing/details/34184 (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/tools-databases/cosing/details/55220 (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/tools-databases/cosing/details/98926 (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/tools-databases/cosing/details/86496 (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/tools-databases/cosing/details/79128 (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/tools-databases/cosing/details/97001 (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/tools-databases/cosing/details/40967 (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/tools-databases/cosing/details/40965 (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/tools-databases/cosing/details/92417 (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/tools-databases/cosing/details/58394 (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/tools-databases/cosing/details/93895 (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/tools-databases/cosing/details/98945 (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/tools-databases/cosing/details/37541 (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/tools-databases/cosing/details/92344 (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/tools-databases/cosing/details/32492 (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/tools-databases/cosing/details/101957 (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/tools-databases/cosing/details/101626 (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Xiao, X.; Hu, X.; Yao, J.; Cao, W.; Zo, Z.; Wang, L.; Qin, H.; Zhong, D.; Li, Y.; Xue, P.; et al. The role of short-chain fatty acids in inflammatory skin diseases. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1083432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solabia Ecoskin. Available online: https://www.solabia.com/cosmetics/product/ecoskin/ (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- UL Prospector, Oligolin®. Available online: https://www.specialchem.com/cosmetics/product/basf-oligolin (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Solabia, Bioecolia®. Available online: https://www.solabia.com/cosmetics/product/bioecolia/ (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Solabia, Serenibiome®. Available online: https://www.solabia.com/cosmetics/product/serenibiome/ (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Available online: https://www.impag.pl/fileadmin/user_upload/PL/Files/Personal_Care/Publikationen/Flyer_Relipidium_2018_04.pdf (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Available online: https://www.ulprospector.com/en/la/PersonalCare/Detail/1960/6352798/Hydrasensyl-Glucan-Green (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Available online: https://www.ulprospector.com/en/la/PersonalCare/Detail/1960/4593183/Phytofirm-Biotic (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Available online: https://www.silab.fr/en/products/skincare/108/lactobiotyl (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Memariani, H.; Memariani, M.; Moravvej, H.; Ranjbar, R.; Akbari, A. The gut–skin axis in psoriasis: Role of probiotics, postbiotics, and short-chain fatty acids in modulating inflammation and microbiota dysbiosis. Heliyon 2025, 11, e025000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mane, S.A.; Bakal, R.L.; Hatwar, P.R.; Kalamb, V.S. Role of probiotics in skin health: Current trends and future perspectives. GSC Biol. Pharm. Sci. 2025, 30, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Mechanism of Action | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Probiotics | Compete with pathogens for niches and nutrients; produce bacteriocins and organic acids; strengthen the epidermal barrier (ceramides, AMPs); modulate immunity (↑ IL-10, ↓ Th17) [128]. | Lactobacillus rhamnosus, L. plantarum, L. johnsonii, Bifidobacterium breve, Streptococcus thermophilus, Staphylococcus hominis, Roseomonas mucosa [133]. |

| Prebiotics | Provide selective nutrients for commensals (e.g., S. epidermidis, non-pathogenic C. acnes); support diversity; maintain acidic pH and lipid balance [136]. | Inulin, β-glucan, oligosaccharides, FOS, GOS, COS, HMOs, algal polysaccharides [136] |

| Postbiotics | Exert anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects; strengthen the skin barrier; reduce pathogen colonization; improve hydration [161,162,163]. | Antimicrobial peptides, lactic acid and SCFAs (Cutibacterium), bacterial polysaccharides (EPS) [161,162,163]. |

| Mechanism of Action on the Microbiome | Cosmetological/Dermatological Applications | |

|---|---|---|

| Symphytum officinale root | The extract maintains microbiota diversity; skin bacteria metabolize its components, producing anti-inflammatory metabolites that support the skin barier [186]. | Comfrey leaves and roots are used in concentrations between 5% and 20% in creams, mainly for healing superficial wounds and it is topical use in skin conditions [232,233]. According to the European cosmetic ingredient database (CosIng) extracts of this plant serve multiple functions in cosmetics, including, anti-seborrheic; skin conditioning; soothing [234,235]. |

| Calendula officinalis | It exhibits antibacterial activity; inhibits the growth of C. acnes. It may also reduce the excessive growth of S. epidermidis [187,188]. Ethanolic and methanolic extracts exhibited inhibitory effects against C. albicans [190]. | According to the (CosIng), extracts of this plant serve multiple functions in cosmetics, including skin conditioning, emollient, skin protection, fragrance, perfuming, and humectant [236,237,238]. Calendula oil cream has been reported to protect the skin from UV radiation when used in sunscreen formulations and to help maintain the natural pigmentation of the skin [239]. |

| Arnica montana | Suggestions of a beneficial effect on the composition of the microbiome [186]. | According cosing: Arnica montana extract used in cosmetics mainly as a skin-conditioning and soothing agent [240]. Arnica montana flower extract functions as a fragrance and perfuming ingredient, sometimes also contributing to skin protection [241]. Lactobacillus/Arnica montana Flower Ferment Filtrate—obtained by fermenting Arnica montana flowers with Lactobacillus; acts mainly as a humectant and skin-conditioning agent [242]. |

| Centella asiatica | The extract shows broad antibacterial activity, particularly against S. aureus. It has antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties and strengthens the skin barrier, helping to maintain microbiological homeostasis [191]. | According cosing: Centella asiatica extract used in cosmetics for cleansing, skin conditioning, smoothing, soothing, and tonic functions [243]. Hydrolyzed C. asiatica extract provides antioxidant and skin-conditioning (humectant) effects, supporting hydration and protection [244]. C. asiatica Leaf Extract—functions mainly as a skin-conditioning agent [245]. Lactobacillus/Centella asiatica extract ferment extract—obtained by fermenting Centella asiatica with Lactobacillus; acts as a miscellaneous skin-conditioning ingredient [246]. |

| Hamamelis virginiana | Rich in tannins, the extract acts selectively: it inhibits the growth of pathogenic bacteria, reduces biofilm formation and toxin production (particularly against pathogenic strains of S. aureus, S. epidermidis, and Enterococcus). At the same time, it supports the growth of beneficial probiotic bacteria such as Lactobacillus plantarum, protecting them against oxidative stress [192]. | According cosing: Hamamelis virginiana bark/twig extract—used in cosmetics mainly as an astringent and skin-conditioning ingredient [247]. H. virginiana water—functions as an astringent, hair-conditioning, skin-conditioning, and soothing agent [248]. |

| Camellia sinensis | Camellia sinensis leaf extract rich in immunomodulating polyphenols; stimulates skin dendritic cells to produce signals that enhance pathogen clearance while preserving commensal microbes [193]. | According Cosing: Camellia sinensis Leaf Extract—multifunctional cosmetic ingredient with antimicrobial, antioxidant, and astringent effects. Acts as a skin-conditioning agent (emollient, humectant), provides a fragrance, and is used in oral care. It also supports skin barrier function, protection, and has potential as a tonic and UV absorber [249]. Lactobacillus/Camellia sinensis Extract Ferment Extract—obtained by fermenting Camellia sinensis extract with Lactobacillus; functions as a miscellaneous skin-conditioning and skin-protecting ingredient [250]. |

| Punica granatum | Pomegranate extract (standardized to punicalagin), when taken orally, modulates the skin microbiome. After 4 weeks of supplementation, an increase in the abundance of commensal S. epidermidis and Bacillus was observed. The antioxidant and anti-inflammatory components of pomegranate promote beneficial flora and limit pathogenic microorganisms [194,195]. | Saccharomyces/Punica Granatum Fruit Ferment Filtrate—filtrate obtained by fermenting Punica granatum fruit with Saccharomyces; used in cosmetics as a skin-conditioning ingredient [251]. Punica Granatum Extract—extract of the whole pomegranate plant; provides antioxidant activity and skin-protecting effects [252]. |

| Selenicereus undatus | The fruit extract exhibits microbiome-balancing effects. In vitro, it promotes the growth of commensal bacteria (S. epidermidis, S. hominis) while inhibiting pathogens (S. aureus, C. acnes). In a clinical study, a cream containing the extract increased microbiome diversity (Faith’s diversity +20% vs. placebo) [196]. | There is no information in the CosIng database regarding Hylocereus undatus (pitahya, dragon fruit). The extract appears beneficial in reduced redness, improved skin barrier function (−13% TEWL), enhanced radiance (+11% ITA), and evened out pigmentation [196]. |

| Lycopersicon esculentum oil | An example of cosmetic upcycling, showing an increase in dominant commensals (including Staphylococcus spp., Anaerococcus, Cutibacterium), particularly S. epidermidis, while inhibiting (e.g., Kocuria, Micrococcus, Veillonella, Rothia) [197]. | There is no information in the CosIng database regarding oil from tomato pomace |

| Myristica fragrans (nutmeg) | The extract stimulates the proliferation of S. epidermidis, inducing the production of secondary metabolites—SCFAs and AMPs—which inhibit the survival and biofilm formation of S. aureus [198]. | According Cosing: Myristica fragrans seed extract functions in cosmetics primarily as a skin-conditioning ingredient, acting both as an emollient and a humectant, helping to soften the skin and improve its hydration [253]. |

| Ribes nigrum | The enzymatically obtained polyphenol extract stimulates the growth of beneficial coagulase-negative staphylococci (S. epidermidis) while inhibiting pathogenic S. aureus. In an ex vivo stratum corneum model, even low doses of the extract were able to fully restore the favorable balance, re-establishing the dominance of commensal Staphylococcus [199,200]. | According to CosIng, Ribes nigrum leaf extract functions as a skin-conditioning ingredient [254], while R. nigrum fruit extract is listed with multiple functions, including astringent, skin-conditioning (emollient and general), and perfuming [255]. |

| Mel/Honey | Selectively inhibits S. aureus, Streptococcus, Gram-negative rods, dermatophytes and yeasts, while sparing S. epidermidis and some C. acnes strains. In AD, reduces excessive S. aureus colonization and inflammation; lowers pathogen virulence by decreasing toxin production and biofilm formation [209,210,211]. | According to CosIng, Honey extract functions as a skin-conditioning ingredient, (emollient and humectant and moisturizing), and flavoring [256] |

| Propolis | It has antiseptic properties: inhibits the growth of S. aureus and C. albicans, while supporting beneficial biofilms formed by S. epidermidis. Propolis also acts synergistically with antibiotics [216,217,219]. | According to CosIng, Propolis Extract functions as a skin-conditioning ingredient [257]. The modified forms show additional properties: Saccharomyces/Propolis Ferment Extract listed as antimicrobial, antioxidant, humectant, and skin-conditioning [258]. Lactobacillus/Propolis Ferment Extract classified under miscellaneous skin-conditioning functions [259]. |

| Royal jelly | It inhibits the growth of pathogenic microorganisms (C. albicans, S. aureus), while showing weaker effects on commensal flora, suggesting that it may support microbiome balance primarily by targeting pathogens [220,221]. | According to CosIng, Royal Jelly Extract is classified as a skin-conditioning ingredient [260]. |