Ginger Powder-Based Pickering Emulsions: An Innovative Platform for Anticancer Drug Delivery

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. GA4-Based Pickering Emulsion Formulation

2.2. GA4_Pes Characterization

2.3. Preparation and Characterization of DOX-Loaded GA4_Pes

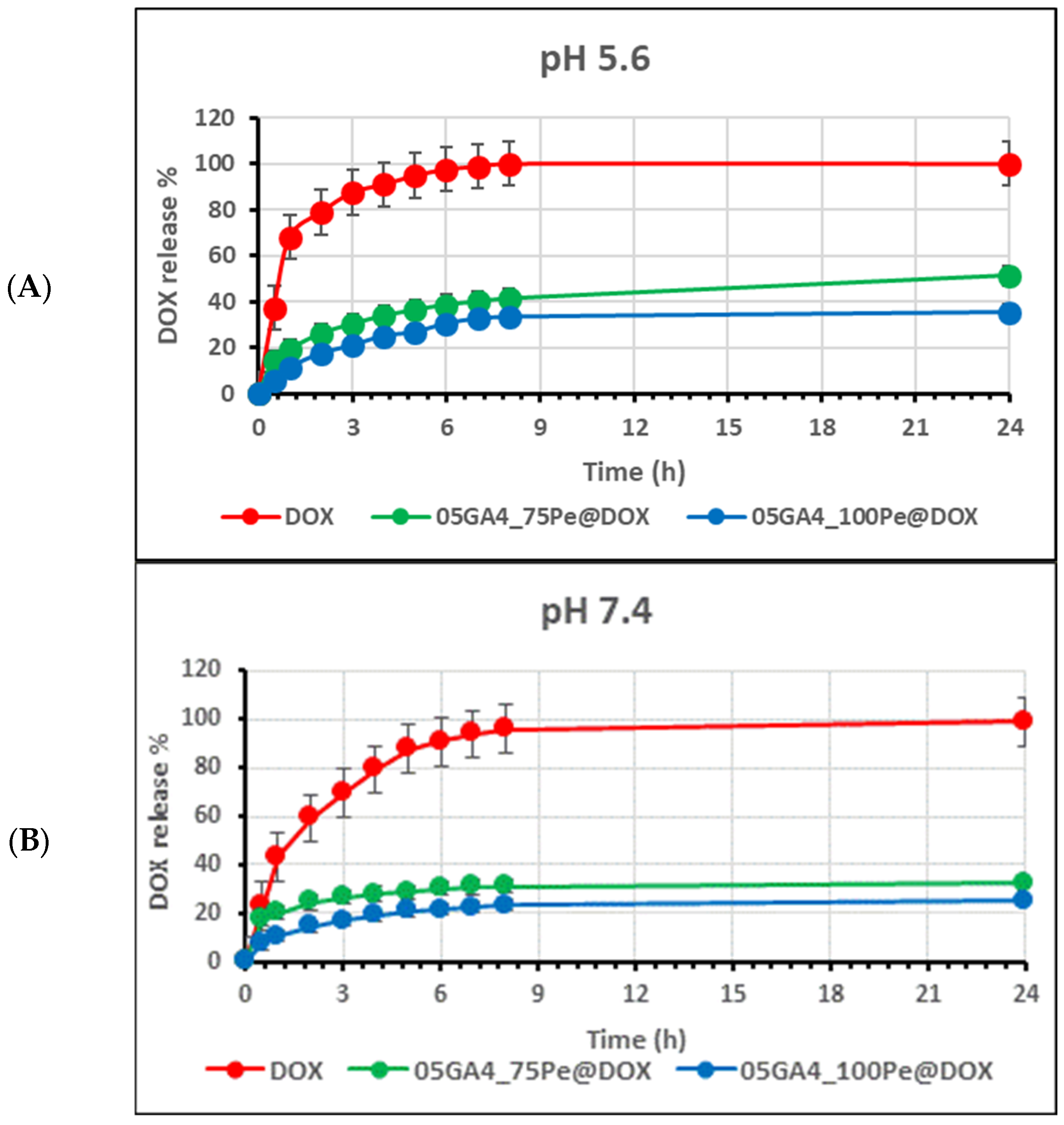

2.4. In Vitro Drug Release Analysis

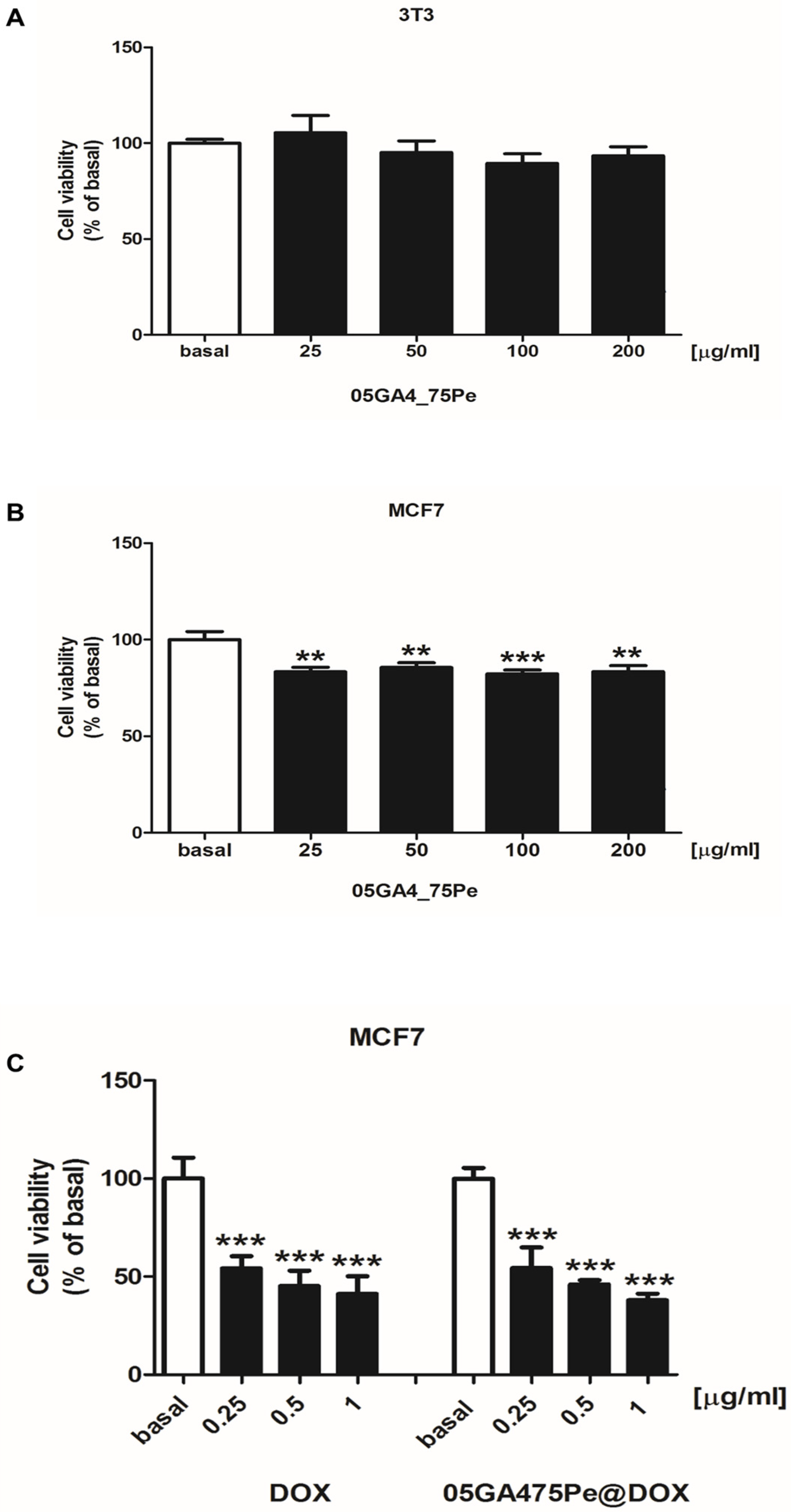

2.5. In Vitro Cytotoxicity Studies

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Preparation of Ginger Powder-Based Pickering Emulsions (GA4_Pes)

3.3. Preparation of Ginger Powder-Based Pickering Emulsions Loading Doxorubicin GA4_Pe@DOX

3.4. Physicochemical Characterization

3.4.1. Stability and Type

3.4.2. Droplet Size Analysis and ζ-Potential Measurements

3.4.3. Optical Microscopy

3.4.4. Cryo-Scanning Electron Microscopy (Cryo-SEM)

3.4.5. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

3.4.6. Rheological Characterization and Analysis

3.4.7. Statistical Analysis

3.5. DOX Entrapment Efficiency in GA4_Pes

3.6. In Vitro Drug Release Studies

3.7. Cell Cultures

3.8. MTT Cell Viability Assay

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

) and after 4 weeks of storage at 4 °C (

) and after 4 weeks of storage at 4 °C ( ); Figure S4: TEM image of a single droplet in the 05GA4_75Pe sample (scale bar = 100 nm). Table S1: Physical–chemical characterization of GA4 powder in terms of size (nm), PdI, contact angles, and ζ potentials at 25 °C and, expressed as the mean of three independent experiments ± SD; Table S2: The IC50 and HillSlope values for DOX, 05GA4_Pe75, and 5GA4_Pe75@DOX for the 3T3 and MCF7 cell viability datasets determined by nonlinear regression analysis using GraphPad Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA) statistical software.

); Figure S4: TEM image of a single droplet in the 05GA4_75Pe sample (scale bar = 100 nm). Table S1: Physical–chemical characterization of GA4 powder in terms of size (nm), PdI, contact angles, and ζ potentials at 25 °C and, expressed as the mean of three independent experiments ± SD; Table S2: The IC50 and HillSlope values for DOX, 05GA4_Pe75, and 5GA4_Pe75@DOX for the 3T3 and MCF7 cell viability datasets determined by nonlinear regression analysis using GraphPad Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA) statistical software.Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GA4 | Ginger powder |

| DOX | Doxorubicin |

| W/O | Water-in-Oil emulsion |

| O/W | Oil-in-Water emulsion |

| W/O/W | Water-in-Oil-in-Water emulsion |

| BS_TDDS | Biocompatible Sustainable Transdermal Drug Delivery System |

| FGPS_Pes | Food-Grade Particle-Stabilized Pickering Emulsions |

| GA4_Pe | Ginger Powder-Stabilized Pickering Emulsion |

| 05GA4_XPe | Ginger Powder-Stabilized Pickering Emulsion with X mg of GA4 |

| GA4_Pe@DOX | Doxorubicin-loaded Ginger Powder-Stabilized Pickering Emulsion |

| GA4_XPe@DOX | Doxorubicin-loaded Ginger Powder-Stabilized Pickering Emulsion with X mg of GA4 |

| PdI | Polydispersity Index |

| DLS | Dynamic Light Scattering |

| POM | Polarized Light Microscopy |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| Cryo-SEM | Cryo-Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| TEM | Transmission Electron Microscopy |

References

- Pickering, S.U. Emulsions. J. Chem. Soc. 1907, 91, 2001–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevalier, Y.; Bolzinger, M.A. Emulsions Stabilized with Solid Nanoparticles: Pickering Emulsions. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2013, 439, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binks, B.P. Particles as Surfactants—Similarities and Differences. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2002, 7, 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Fang, Z.; Chen, X.; Zhang, W.; Xie, Y.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Z.; Yuan, W. An Overview of Pickering Emulsions: Solid-Particle Materials, Classification, Morphology, and Applications. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 235054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Carvalho-Guimarães, F.B.; Correa, K.L.; de Souza, T.P.; Rodríguez Amado, J.R.; Ribeiro-Costa, R.M.; Silva-Júnior, J.O.C. A Review of Pickering Emulsions: Perspectives and Applications. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, A.; Lopes, J.C.B.; Dias, M.M.; Barreiro, M.F. Pickering Emulsions Based in Inorganic Solid Particles: From Product Development to Food Applications. Molecules 2023, 28, 2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mwangi, W.W.; Lim, H.P.; Low, L.E.; Tey, B.T.; Chan, E.S. Food-Grade Pickering Emulsions for Encapsulation and Delivery of Bioactives. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 100, 320–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, H.; Sun, X.; Fan, F. Development and Characterization of Pickering Emulsion Stabilized by Walnut Protein Isolate Nanoparticles. Molecules 2023, 28, 5434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A.; Dickinson, E. Sustainable food-grade Pickering emulsions stabilized by plant-based particles. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 49, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, T.; Xue, C.; Wei, Z. Physicochemical characteristics, applications and research trends of edible Pickering emulsions. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 107, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formoso, P.; Tundis, R.; Pellegrino, M.C.; Leporini, M.; Sicari, V.; Romeo, R.; Gervasi, L.; Corrente, G.A.; Beneduci, A.; Loizzo, M.R. Preparation, characterization, and bioactivity of Zingiber officinale Roscoe powder-based Pickering emulsions. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2022, 102, 6566–6577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazt, B.; Parchen, G.P.; do Amaral, L.F.M.; Gallina, P.R.; Martin, S.; Gonçalves, O.H.; de Freitas, R.A. Unconventional and conventional Pickering emulsions: Perspectives and challenges in skin applications. Int. J. Pharm. 2023, 636, 122817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.-Y.; Shin, H.-Y.; Kim, J.-Y.; Park, S.J. Safety Assessment of Starch Nanoparticles as an Emulsifier in Human Skin Cells, 3D Cultured Artificial Skin, and Human Skin. Molecules 2023, 28, 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiranphinyophat, S.; Otaka, A.; Asaumi, Y.; Fujii, S.; Iwasaki, Y. Particle-stabilized oil-in-water emulsions as a platform for topical lipophilic drug delivery. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2021, 197, 111423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.K.; Setia, A.; Singh, S.; Baghel, Y.S.; Joshi, D.; Bhattacharya, S. Pickering Emulsions: A Potential Strategy to Limiting Cancer Development. Curr. Nanomed. 2022, 12, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Ao, F.; Ge, X.; Shen, W. Food-Grade Pickering Emulsions: Preparation, Stabilization and Applications. Molecules 2020, 25, 3202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koss-Mikołajczyk, I.; Todorovic, V.; Sobajic, S.; Mahajna, J.; Gerić, M.; Tur, J.A.; Bartoszek, A. Natural Products Counteracting Cardiotoxicity during Cancer Chemotherapy: The Special Case of Doxorubicin, a Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muggia, F.M.; Green, M.D. New anthracycline antitumor antibiotics. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 1991, 11, 43–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Lin, M. The Synthesis of Nano-Doxorubicin and its Anticancer Effect. Anti-Cancer Agents Med. Chem. 2021, 21, 2466–2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, S.; Alven, S.; Maseko, R.B.; Aderibigbe, B.A. Doxorubicin-Based Hybrid Compounds as Potential Anticancer Agents: A Review. Molecules 2022, 27, 4478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, H.; Tang, Y.; Wang, S.; Yan, X.; Liu, C.; Guo, L.; Wang, E.; Xu, C. Optimized DOX Drug Deliveries via Chitosan-Mediated Nanoparticles and Stimuli Responses in Cancer Chemotherapy: A Review. Molecules 2024, 29, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neupane, R.; Boddu, S.H.S.; Abou-Dahech, M.S.; Bachu, R.D.; Terrero, D.; Babu, R.J.; Tiwari, A.K. Transdermal Delivery of Chemotherapeutics: Strategies, Requirements, and Opportunities. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohyeddin, A.; Nidal, J.; Lana, M. The Formation of Self-Assembled Nanoparticles Loaded with Doxorubicin and D-Limonene for Cancer Therapy. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 42096–42104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellosi, D.S.; Macaroff, P.P.; Morais, P.C.; Tedesco, A.C. Magneto low-density nanoemulsion (MLDE): A potential vehicle for combined hyperthermia and photodynamic therapy to treat cancer selectively. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2018, 92, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, K.S.; Changling, S.; Shan, X.; Mao, J.; Qiu, L.; Chen, J. Liposome-based codelivery of celecoxib and doxorubicin hydrochloride as a synergistic dual-drug delivery system for enhancing the anticancer effect. J. Liposome Res. 2020, 30, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Zhang, P.; Shan, W.; Gao, J.; Liang, W. A novel chitosan-based thermosensitive hydrogel containing doxorubicin liposomes for topical cancer therapy. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2013, 24, 1649–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, S.M.; Mansur, A.A.; Capanema, N.S.; Carvalho, I.C.; Chagas, P.; de Oliveira, L.C.A.; Mansur, H.S. Synthesis and in vitro assessment of anticancer hydrogels composed by carboxymethylcellulose-doxorubicin as potential transdermal delivery systems for treatment of skin cancer. J. Mol. Liq. 2018, 266, 425–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radu, E.R.; Semenescu, A.; Voicu, S.I. Recent Advances in Stimuli-Responsive Doxorubicin Delivery Systems for Liver Cancer Therapy. Polymers 2022, 14, 5249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Gomes, B.; Cláudia Paiva-Santos, A.; Veiga, F.; Mascarenhas-Melo, F. Beyond the adverse effects of the systemic route: Exploiting nanocarriers for the topical treatment of skin cancers. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2024, 207, 115197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Vinothini, K.; Ramesh, T.; Rajan, M.; Ramu, A. Combined photodynamic-chemotherapy investigation of cancer cells using carbon quantum dot-based drug carrier system. Drug Deliv. 2020, 27, 791–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral, Á.S.; Leonel, E.C.R.; Candido, N.M.; Piva, H.L.; de Melo, M.T.; Taboga, S.R.; Rahal, P.; Tedesco, A.C.; Calmon, M.F. Combined photodynamic therapy with chloroaluminum phthalocyanine and doxorubicin nanoemulsions in breast cancer model. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2021, 218, 112181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhu, K.; Zeng, H.; Zhang, J.; Pu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, T.; Wang, B. Resveratrol solid lipid nanoparticles to trigger credible inhibition of doxorubicin cardiotoxicity. Int. J. Nanomed. 2019, 14, 6061–6071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, C.; Wu, H.; Xu, K.; Cai, T.; Qin, K.; Wu, L.; Cai, B. Liquiritigenin-Loaded Submicron Emulsion Protects Against Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity via Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory, and Anti-Apoptotic Activity. Int. J. Nanomed. 2020, 15, 1101–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wi, T.I.; Won, J.E.; Lee, C.M.; Lee, J.-W.; Kang, T.H.; Shin, B.C.; Han, H.D.; Park, Y.-M. Efficacy of Combination Therapy with Linalool and Doxorubicin Encapsulated by Liposomes as a Two-in-One Hybrid Carrier System for Epithelial Ovarian Carcinoma. Int. J. Nanomed. 2020, 29, 8427–8436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deschamps, F.; Isoardo, T.; Denis, S.; Tsapis, N.; Tselikas, L.; Nicolas, V.; Paci, A.; Fattal, E.; de Baere, T.; Huang, N.; et al. Biodegradable Pickering emulsions of Lipiodol for liver trans-arterial chemo-embolization. Acta Biomater. 2019, 87, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, D.; Yue, S.; Sun, H.; Ni, C.; Zhong, Z. Polymersome-stabilized doxorubicin-lipiodol emulsions for high efficacy chemoembolization therapy. J. Control. Release 2022, 350, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, X.; Xiao, J.; Jiang, H.; Ma, L.; Luo, Y.; Wang, M.; Zhu, Y.; Jiang, H.; Yao, H.; et al. Ultrastable Iodinated Oil-Based Pickering Emulsion Enables Locoregional Sustained Codelivery of Hypoxia Inducible Factor-1 Inhibitor and Anticancer Drugs for Tumor Combination Chemotherapy. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2024, 10, 2270–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binks, B.P.; Dyab, A.K.F.; Fletcher, P.D.I. Novel emulsions of ionic liquids stabilised solely by silica nanoparticles. Chem. Commun. 2003, 20, 2540–2541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binks, B.P.; Whitby, C.P. Silica particle-stabilized emulsions of silicone oil and water: Aspects of emulsification. Langmuir 2004, 20, 1130–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Dai, H.; Ma, L.; Fu, Y.U.; Yu, Y.; Zhou, H.; Guo, T.; Zhu, H.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Y. Properties of Pickering emulsion stabilized by food-grade gelatin nanoparticles: Influence of the nanoparticles concentration. Colloids Surf. B. 2020, 196, 111294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClements, D.J. Food Emulsions: Principles, Practices, and Techniques, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, C.; Rosa, P.; Filipe, A.; Medronho, B.; Romano, A.; Liberman, L.; Talmon, Y.; Norgren, M. Cellulose-stabilized oil-in-water emulsions: Structural features, microrheology, and stability. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 252, 117092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, T.; Sun, H.; Niu, Z.; Xu, W.; Li, Z.; He, Y.; Luo, D.; Xi, W.; Wei, J.; Zhang, C. Carrageenan-Based Pickering Emulsion Gels Stabilized by Xanthan Gum/Lysozyme Nanoparticle: Microstructure, Rheological, and Texture Perspective. Foods 2022, 11, 3757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Zheng, S.; Sun, H.; Ning, Y.; Jia, Y.; Luo, D.; Yingying, L.; Shah, B.R. Rheological behavior and microstructure of Pickering emulsions based on different concentrations of gliadin/sodium caseinate nanoparticles. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2021, 247, 2621–2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, N.; Gani, A.; Jhan, F.; Shah, M.A.; Ashraf, Z. Ferulic acid loaded pickering emulsions stabilized by resistant starch nanoparticles using ultrasonication: Characterization, in vitro release and nutraceutical potential. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2022, 84, 105967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aveyard, R.; Binks, B.P.; Clint, J.H. Emulsions stabilized solely by colloidal particles. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2003, 100–102, 503–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Zhang, W.; Xu, Y.; Yu, Y.; Lin, X.; Fu, M.; Liu, H.; Peng, J.; Zhao, Z. Cellulose nanofiber from pomelo spongy tissue as a novel particle stabilizer for Pickering emulsion. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 224, 1439–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, J.R.; Bhella, D.; Adrian, M. Recent Developments in Negative Staining for Transmission Electron Microscopy. In Microscopy and Analysis; Wiley Analytical Science: Chichester, West Sussex, UK, 2006; pp. 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.; Belwal, T.; Aalim, H.; Li, L.; Lin, X.; Liu, S.; Qunhe, L.; Zou, Y.; Luo, Z. Protein-Polysaccharide Complex Coated W/O/W Emulsion as Secondary Micro- Capsule for Hydrophilic Arbutin and Hydrophobic Coumaric Acid. Food Chem. 2019, 300, 125171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, H.; Yang, T.; Lin, Q.; Liu, G.; Zhang, L.; Yu, F.; Chen, Y. Acetylated starch nanocrystals: Preparation and antitumor drug delivery study. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 89, 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formariz, T.P.; Chiavacci, L.A.; Scarpa, M.V.; Silva-Júnior, A.A.; Egito, E.S.T.; Terrugi, C.H.B.; Franzini, C.M.; Sarmento, V.H.V.; Oliveira, A.G. Structure and viscoelastic behavior of pharmaceutical biocompatible anionic microemulsions containing the antitumoral drug compound doxorubicin. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2010, 77, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formariz, T.P.; Sarmento, V.H.V.; Silva-Junior, A.A.; Scarpa, M.V.; Santilli, C.V.; Oliveira, A.G. Doxorubicin biocompatible O/W microemulsion stabilized by mixed surfactant containing soya phosphatidylcholine. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2006, 51, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, S.; Gholami, M.H.; Hashemi, F.; Zabolian, A.; Farahani, M.V.; Hushmandi, K.; Zarrabi, A.; Goldman, A.; Ashrafizadeh, M.; Orive, G. Advances in Understanding the Role Of P-Gp in Doxorubicin Resistance: Molecular Pathways, Therapeutic Stra-tegies, and Prospects. Drug Discov. Today 2022, 27, 436–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajeev, M.R.; Athira, M.; Suriya, R.; Thayyath, S.A. A Self-Skin Permeable Doxorubicin Loaded Nanogel Composite as a Transdermal Device for Breast Cancer Therapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 50407–50429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 55. Stagnoli, S.; Garro, C.; Ertekin, O.; Heid, S.; Seyferth, S.; Soria, G.; Correa, N.M.; Leal-Egaña, A.; Boccaccini, A.R. Topical systems for the controlled release of antineoplastic Drugs: Oxidized Alginate-Gelatin Hydrogel/Unilamellar vesicles. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 629, 1066–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pradhan, R.; Kim, Y.I.; Jeong, J.H.; Choi, H.G.; Yong, C.S.; Kim, J.O. Fabrication, characterization and pharmacokinetic evaluation of doxorubicin-loaded water-in-oil-in-water microemulsions using a membrane emulsification technique. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2014, 62, 875–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkhatib, M.H.; AlBishi, H.M. In vitro evaluation of antitumor activity of doxorubicin-loaded nanoemulsion in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. J. Nanopart. Res. 2013, 15, 1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.P.; Hua, H.Y.; Sun, P.C.; Zhao, Y.X. A Novel submicron emulsion system loaded with doxorubicin overcome multi-drug resistance in MCF-7/ADR cells. Indian J. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 77, 499–5041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xiong, T.; Wang, X.F.; Chen, D.L.; He, X.D.; Zhang, C.; Wu, C.; Li, Q.; Ding, X.; Qian, J.Y. Pickering emulsifiers based on enzymatically modified quinoa starches: Preparation, microstructures, hydrophilic property and emulsifying property. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 190, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Belwal, T.; Liu, S.; Duan, Z.; Luo, Z. Novel multi-phase nano-emulsion preparation for co-loading hydrophilic arbutin and hydrophobic coumaric acid using hydrocolloids. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 93, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, H.A.; Hutton, J.F.; Walters, K. An Introduction to Rheology; (First, thi); Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriele, D.; de Cindio, B.; D’Antona, P. A weak gel model for foods. Rheol. Acta 2001, 40, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fard, G.H.; Moinipoor, Z.; Anastasova-Ivanova, S.; Iqbal, H.M.N.; Dwek, M.V.; Getting, S.J.; Keshavarz, T. Development of chitosan, pullulan, and alginate based drug-loaded nano-emulsions as a potential malignant melanoma delivery platform. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2022, 4, 100250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimento, A.; Santarsiero, A.; Iacopetta, D.; Ceramella, J.; De Luca, A.; Infantino, V.; Parisi, O.I.; Avena, P.; Bonomo, M.G.; Saturnino, C.; et al. A Phenylacetamide Resveratrol Derivative Exerts Inhibitory Effects on Breast Cancer Cell Growth. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample ID | η∞ (Pa s) | K (Pa sn) | n (-) | A (Pa s1/z) | z (-) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 05GA4_75Pe | 0.0276 ± 0.006 | 2.2 ± 0.3 a | 0.19 ± 0.02 a | 92 ± 22 a | 6.4 ± 2.0 a |

| 05GA4_100Pe | - | 29.9 ± 5.5 b | 0.054 ± 0.008 b | 587 ± 86 b | 7.8 ± 0.7 a |

| 05GA4_200Pe | - | 118 ± 14 c | 0.065 ± 0.02 b | 1680 ± 70 c | 7.5 ± 0.8 a |

| Sample ID | η∞ (Pa s) | K (Pa sn) | n (-) | A (Pa s1/z) | z (-) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 05GA4_75Pe at 37 °C | 0.0258 ± 0.004 a | 1.02 ± 0.08 a | 0.240 ± 0.02 a | 32.2 ± 5.6 a | 8.9 ± 0.6 ab |

| 05GA4_75Pe@DOX at 37 °C | 0.015 ± 0.006 b | 0.42 ± 0.05 b | 0.427 ± 0.09 b | 7.6 ± 1.4 b | 14.5 ± 6.7 b |

| 05GA4_75Pe@DOX at 25 °C | 0.020 ± 0.005 ab | 2.9 ± 0.5 c | 0.168 ± 0.03 a | 11.6 ± 0.9 ab | 5.0 ± 0.2 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Formoso, P.; Mammolenti, D.; Chimento, A.; Pellegrino, M.C.; Perrotta, I.D.; Lupi, F.R.; Gabriele, D.; Pezzi, V. Ginger Powder-Based Pickering Emulsions: An Innovative Platform for Anticancer Drug Delivery. Molecules 2025, 30, 4349. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30224349

Formoso P, Mammolenti D, Chimento A, Pellegrino MC, Perrotta ID, Lupi FR, Gabriele D, Pezzi V. Ginger Powder-Based Pickering Emulsions: An Innovative Platform for Anticancer Drug Delivery. Molecules. 2025; 30(22):4349. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30224349

Chicago/Turabian StyleFormoso, Patrizia, Domenico Mammolenti, Adele Chimento, Maria Carmela Pellegrino, Ida Daniela Perrotta, Francesca Romana Lupi, Domenico Gabriele, and Vincenzo Pezzi. 2025. "Ginger Powder-Based Pickering Emulsions: An Innovative Platform for Anticancer Drug Delivery" Molecules 30, no. 22: 4349. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30224349

APA StyleFormoso, P., Mammolenti, D., Chimento, A., Pellegrino, M. C., Perrotta, I. D., Lupi, F. R., Gabriele, D., & Pezzi, V. (2025). Ginger Powder-Based Pickering Emulsions: An Innovative Platform for Anticancer Drug Delivery. Molecules, 30(22), 4349. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30224349