Dawson- and Lindqvist-Type Hybrid Polyoxometalates: Synthesis, Characterization and Ca2+-ATPase Inhibition Potential

Abstract

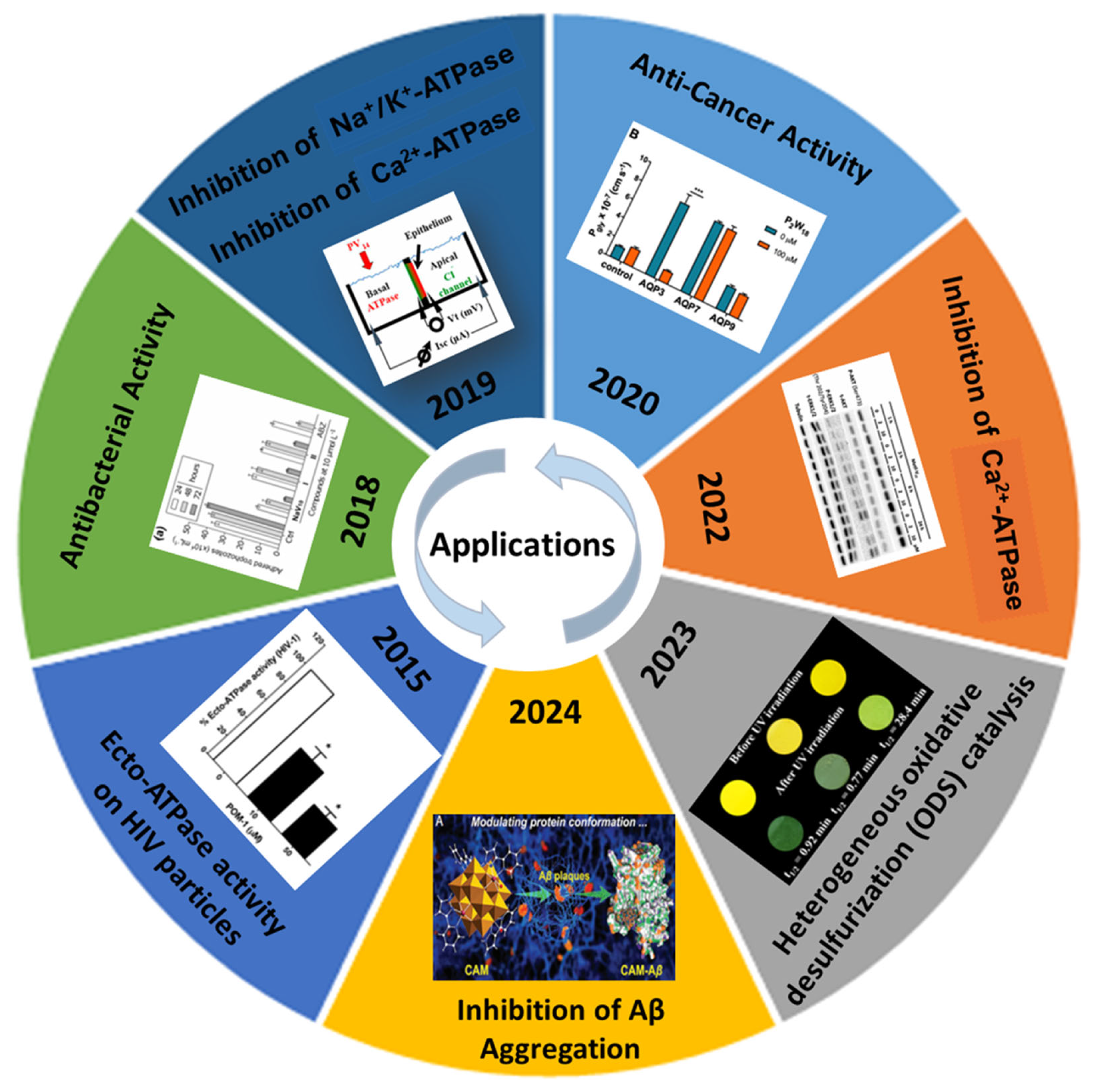

1. Introduction

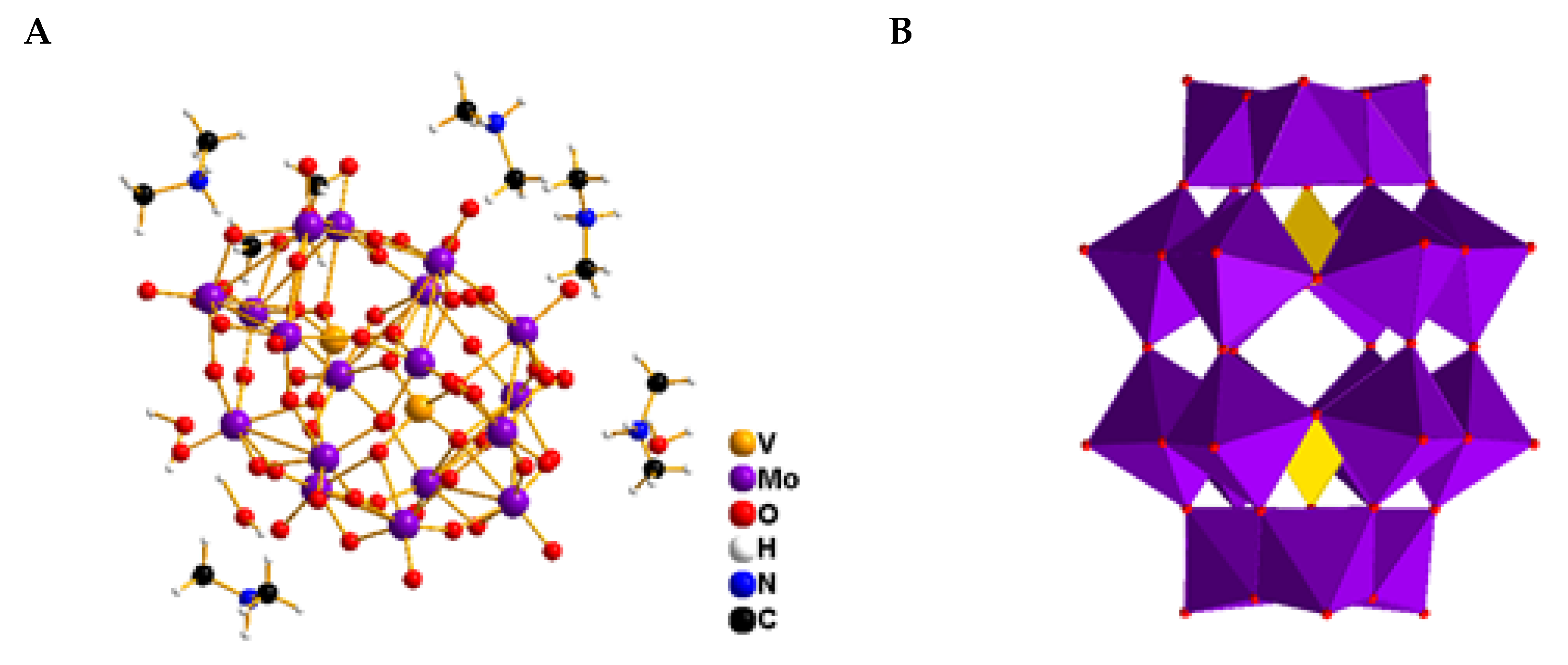

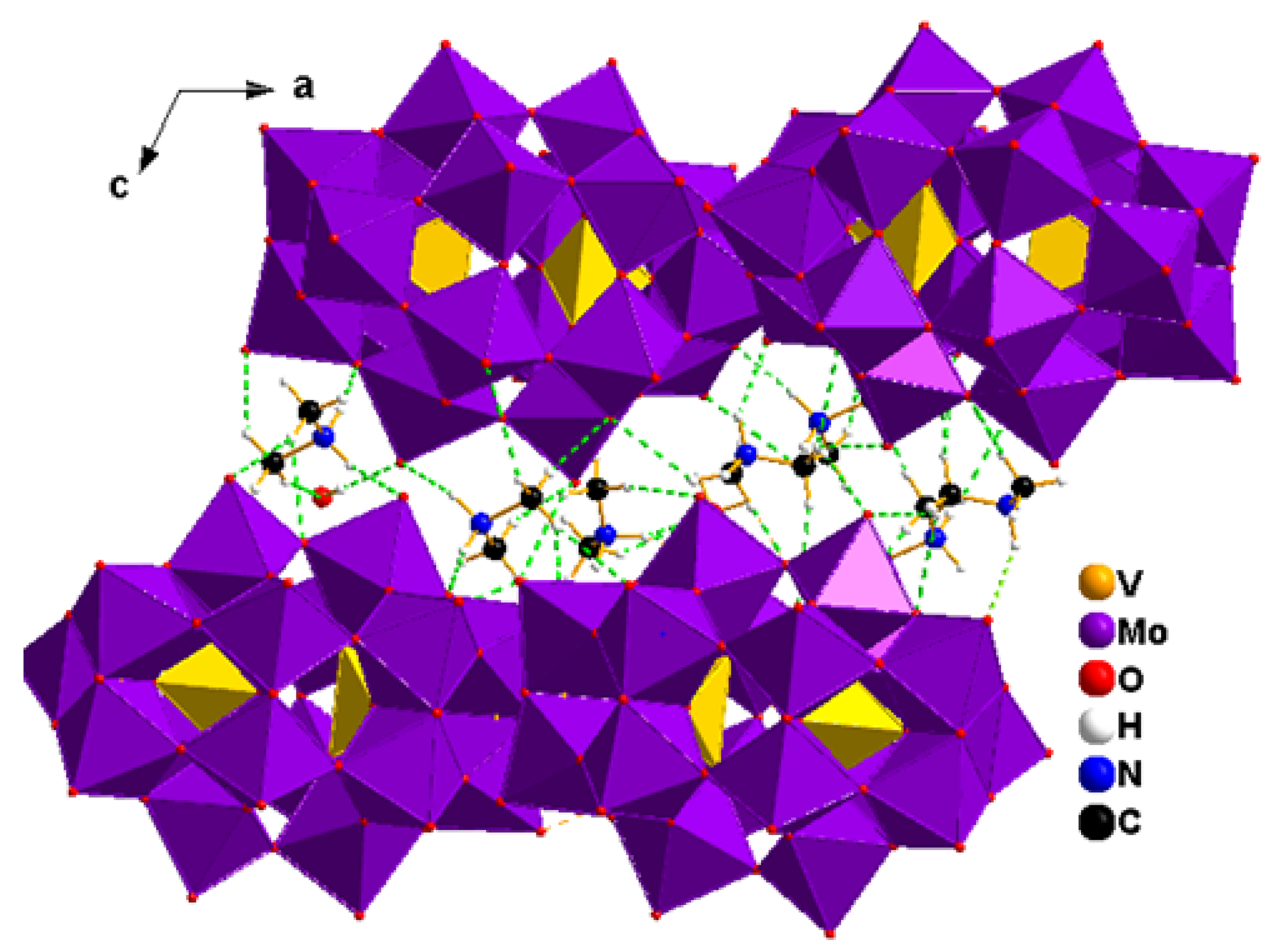

2. Results and Discussion

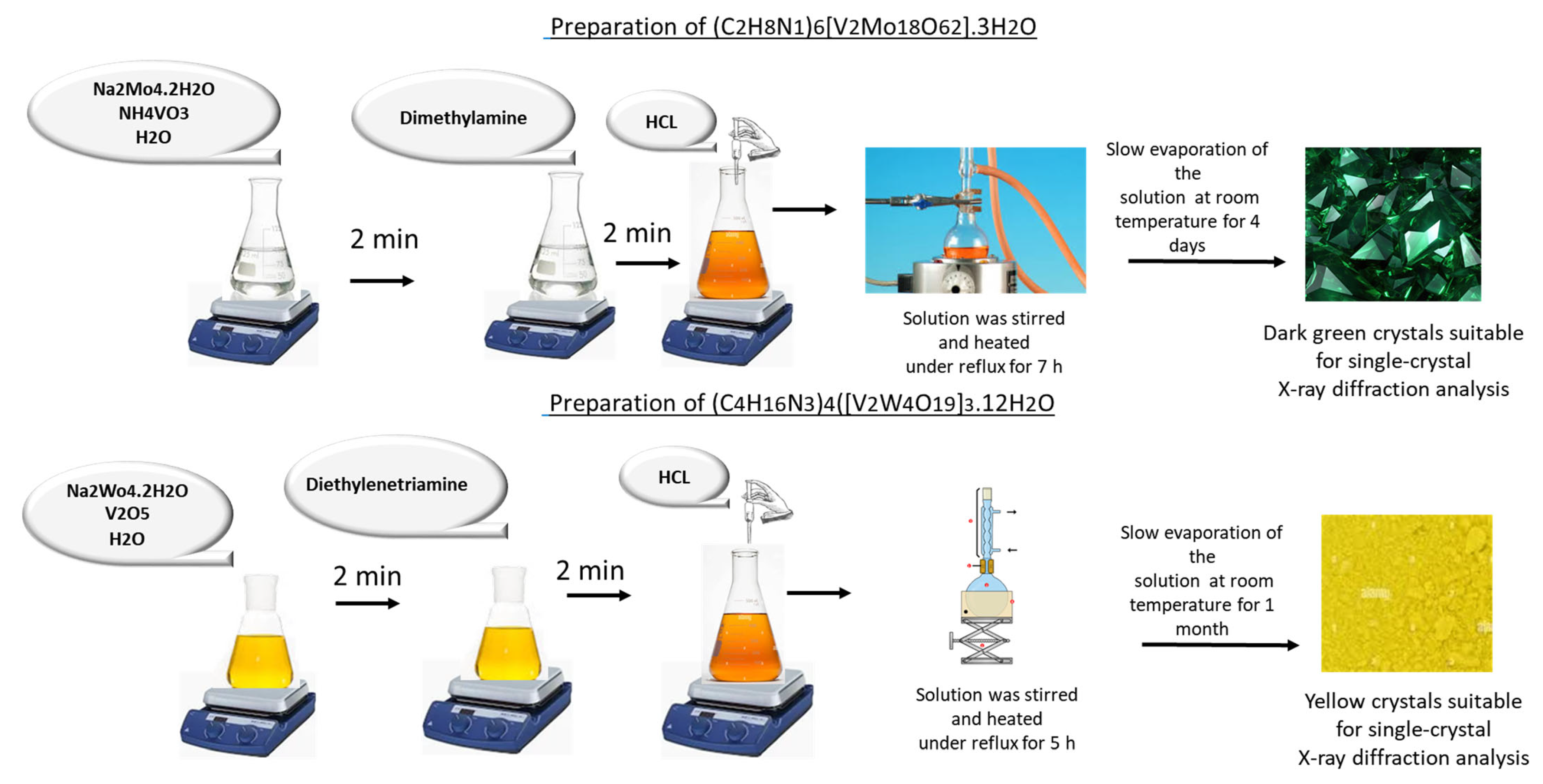

2.1. Synthesis

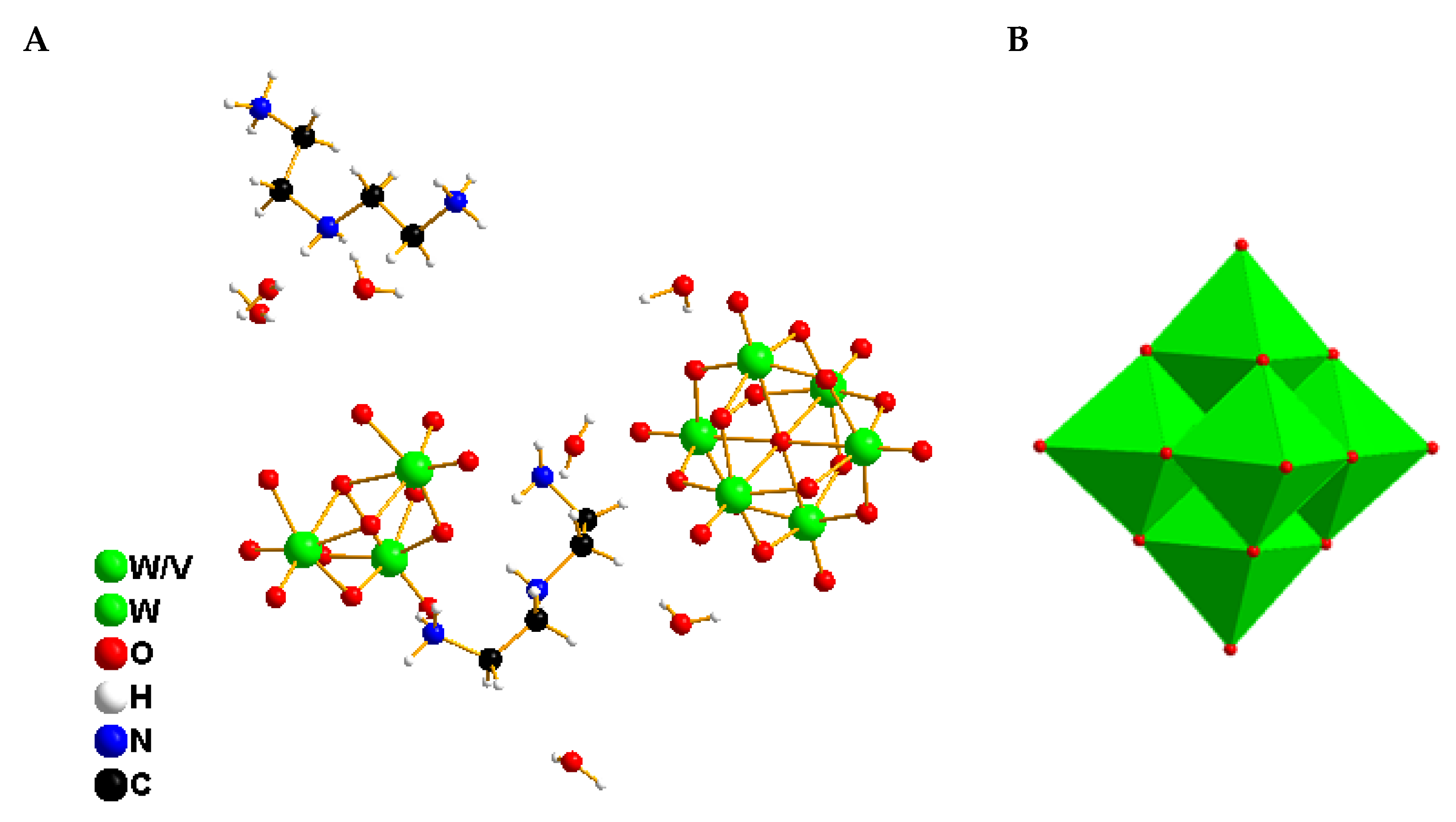

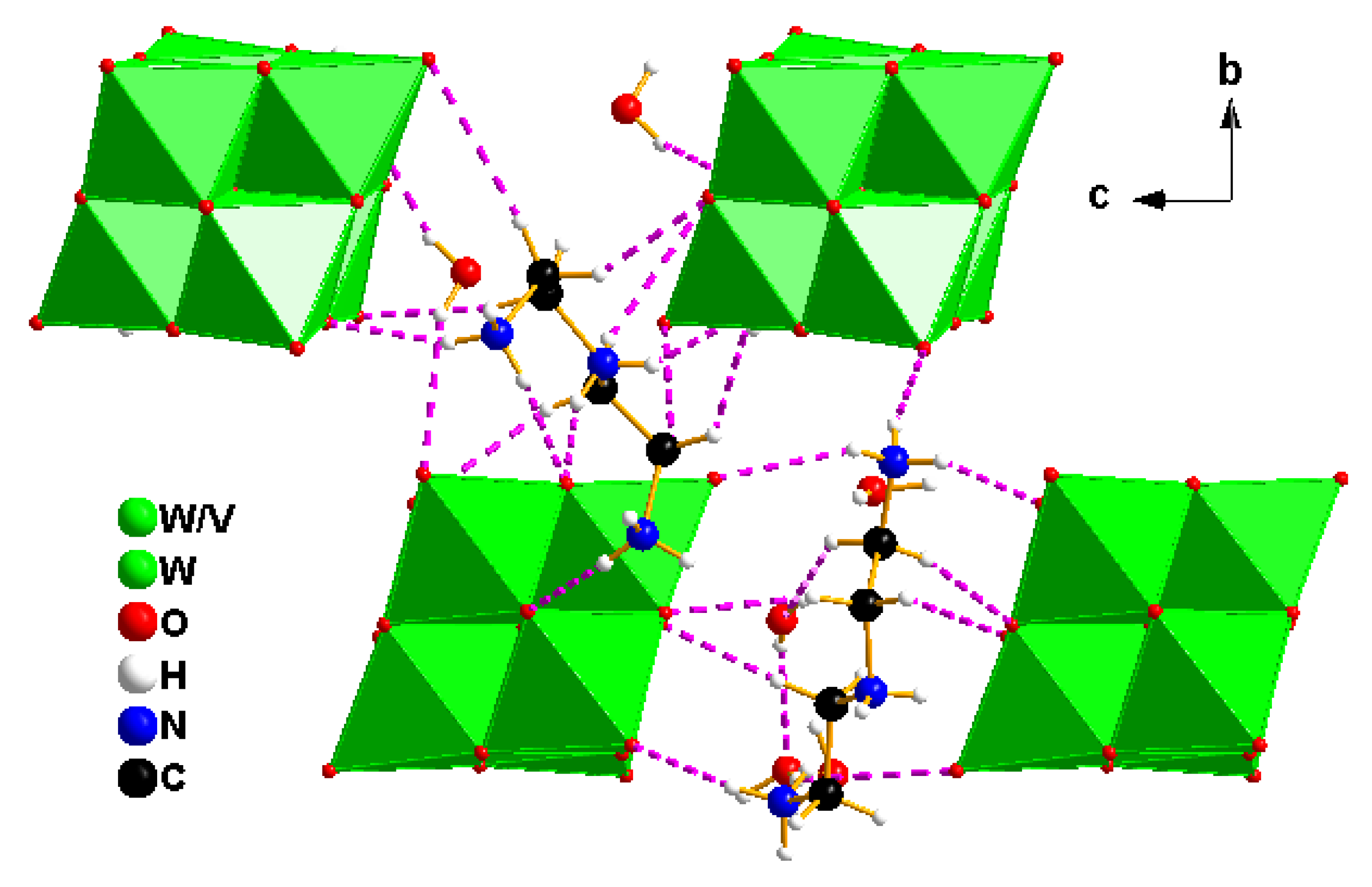

2.2. Crystallization of the Compounds

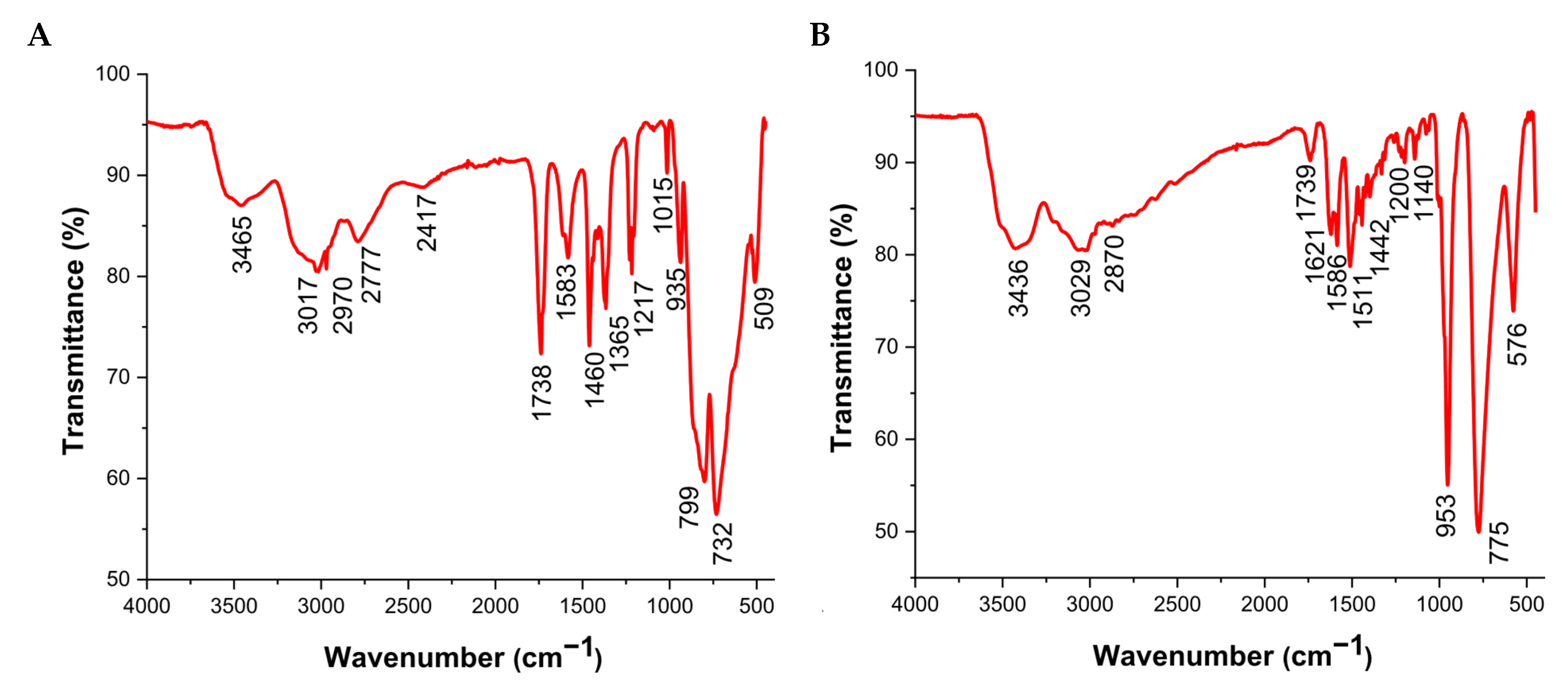

2.3. Characterization of the Compounds

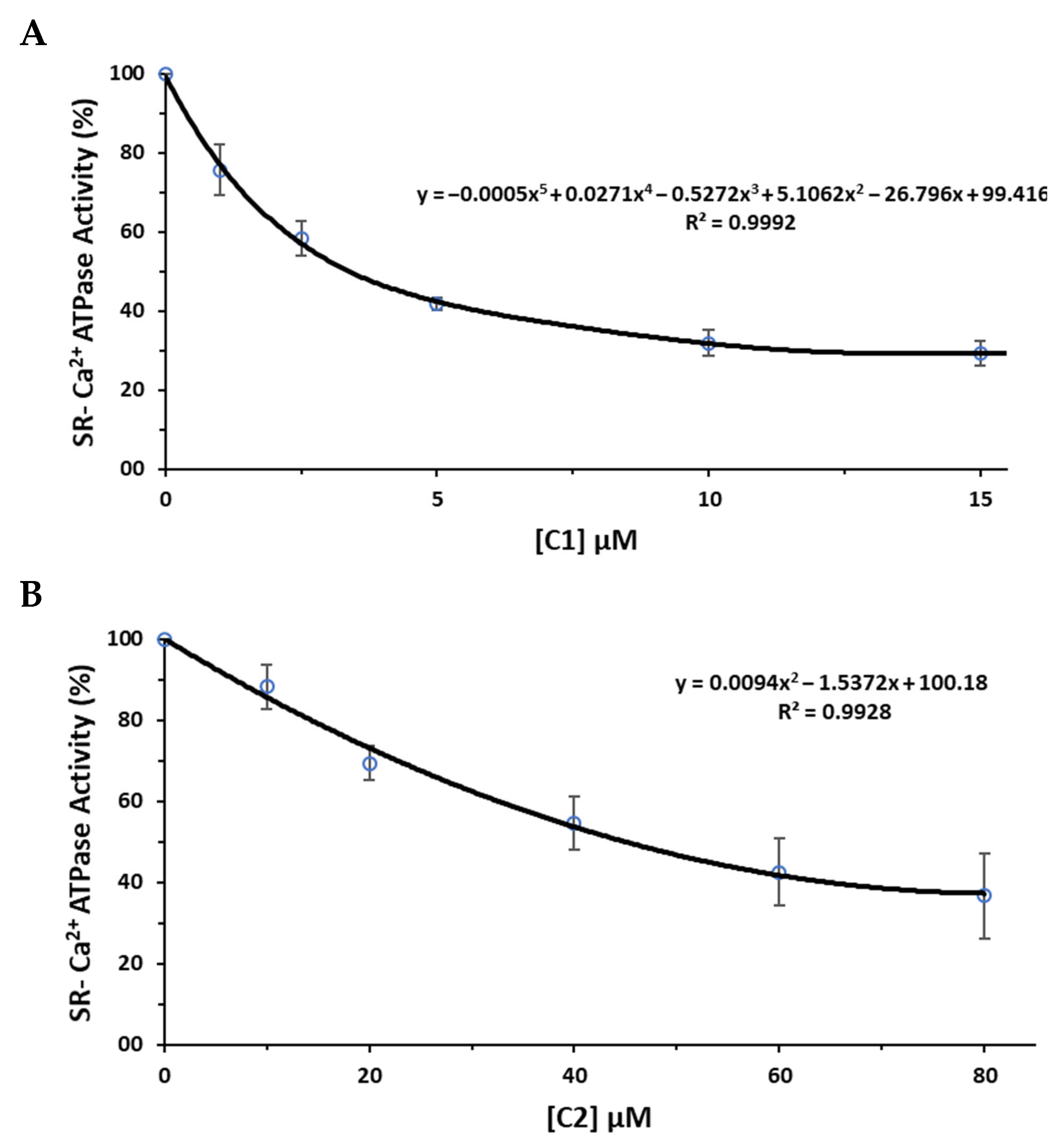

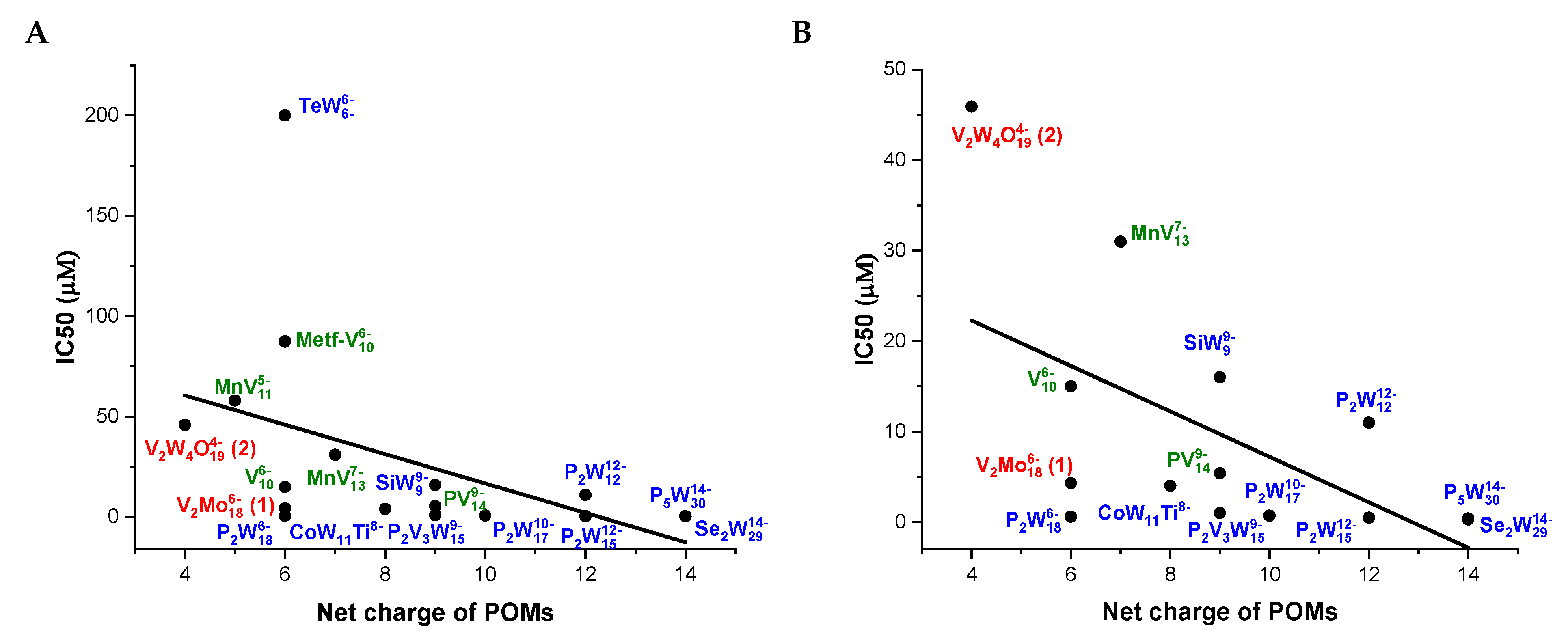

2.4. Polyoxometalates Inhibition of Ca2+-ATPase

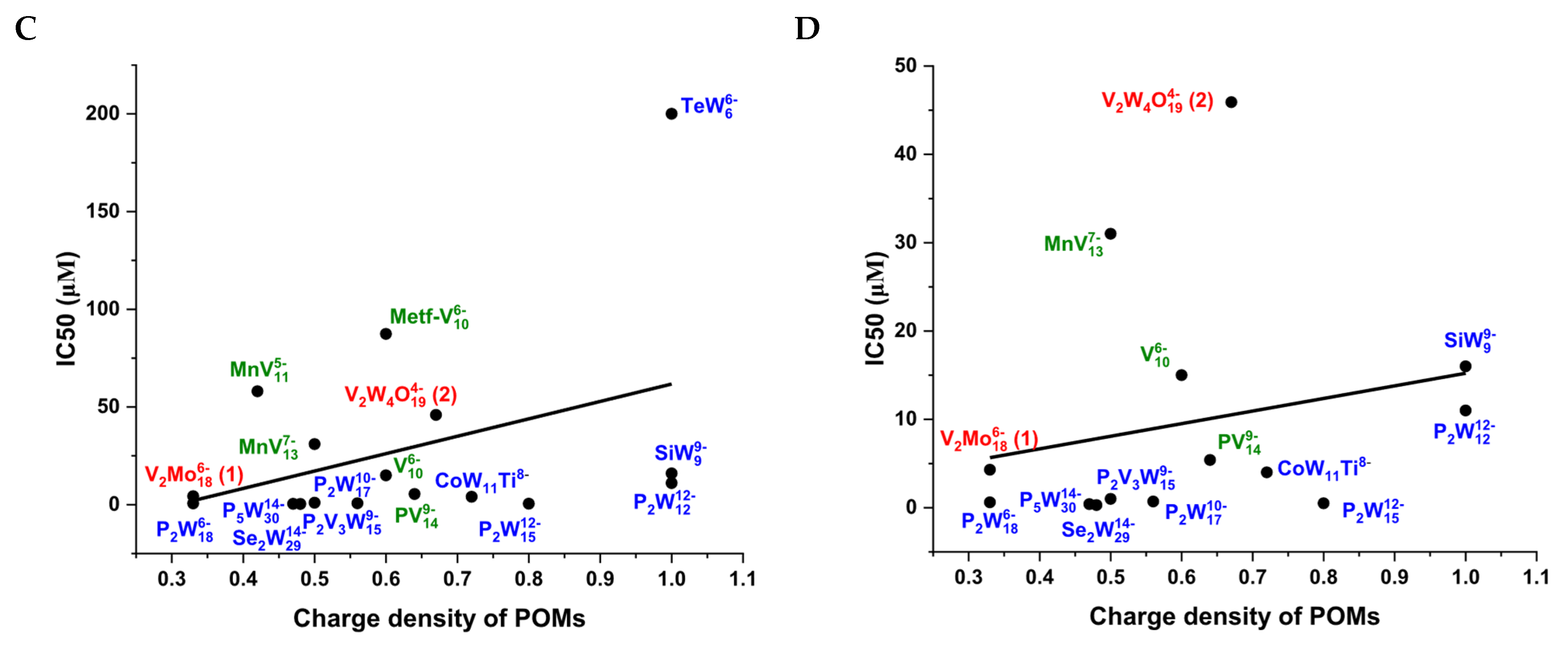

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Reagents

3.2. Characterization

3.3. Preparation of Sarcoplasmic Reticulum Vesicles and POMs Solutions

3.4. Determination of Ca2+-ATPase IC50 Values

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AD | Alzheimer’s Disease |

| BVS | bond valence sum |

| CE | celecoxib |

| CPA | cyclopiazonic acid |

| E-NTPDase | ecto-nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolases |

| HPOMs | heteropolyoxometalates |

| IC50 | 50% inhibitory concentration |

| ID | distortion index |

| IPOMs | isopolyoxometalates |

| MOFs | metal organic frameworks |

| MV | mixed valence |

| PEP | phosphoenolpyruvate |

| POMos | polyoxomolybdates |

| POTs | polyoxotungstates |

| POVs | polyoxovanadates |

| SRVs | sarcoplasmic reticulum vesicles |

| TG | thapsigargin |

References

- Rathee, B.; Wati, M.; Sindhu, R.; Sindhu, S. Review of Some Applications of Polyoxometalates. Orient. J. Chem. 2022, 38, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarroug, R.; Moslah, W.; Srairi-Abid, N.; Artetxe, B.; Masip-Sánchez, A.; López, X.; Ayed, B.; Ribeiro, N.; Correia, I.; Corte-Real, L.; et al. Synthesis, Crystal Structure, Computational and Solution Studies of a New Phosphotetradecavanadate Salt. Assessment of Its Effect on U87 Glioblastoma Cells. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2025, 269, 112882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouallegui, T.; Zarroug, R.; Artetxe, B.; Ayed, B. Structural Resolution of the New Polyoxometalate Hybrid (C2N4H7O)4(NH4)[HMo7O24]·4H2O: Textile Dye Decolorization and BSA Binding Properties. J. Mol. Struct. 2025, 1336, 142069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouallegui, T.; Dege, N.; Ayed, B. Structural, Physico-Chemical Properties of a Hybrid Material Based on Anderson-Type Polyoxomolybdates. J. Iran. Chem. Soc. 2023, 20, 2373–2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schachter, J.; Delgado, K.V.; Souza, V.B.; Bou-Habib, D.C.; Persechini, P.M.; Fernandes, J.R.M. Inhibition of ecto-ATPase activities impairs HIV-1 infection of macrophages. Immunobiology. 2015, 220, 589–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missina, J.M.; Gavinho, B.; Postal, K.; Santana, F.S.; Valdameri, G.; de Souza, E.M.; Hughes, D.L.; Ramirez, M.I.; Soares, J.F.; Nunes, G.G. Effects of Decavanadate Salts with Organic and Inorganic Cations on Escherichia coli, Giardia intestinalis, and Vero Cells. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 57, 11930–11941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques-da-Silva, D.; Fraqueza, G.; Lagoa, R.; Vannathan, A.A.; Mal, S.S.; Aureliano, M. Polyoxovanadate Inhibition of Escherichia coli Growth Shows a Reverse Correlation with Ca2+-ATPase Inhibition. New J. Chem. 2019, 48, 15016–15027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimpão, C.; da Silva, I.V.; Mósca, A.F.; Pinho, J.O.; Gaspar, M.M.; Gumerova, N.I.; Rompel, A.; Aureliano, M.; Soveral, G. The Aquaporin-3-Inhibiting Potential of Polyoxotungstates. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sousa-Coelho, A.L.; Aureliano, M.; Fraqueza, G.; Serrão, G.; Gonçalves, J.; Sánchez-Lombardo, I.; Link, W.; Ferreira, B.I. Decavanadate and Metformin-Decavanadate Effects in Human Melanoma Cells. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2022, 235, 111915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghmasheh, M.; Rezvani, M.A.; Jafarian, V.; Ardeshiri, H.H. Synthesis and Characterization of a New Nanocatalyst Based on Keggin-Type Polyoxovanadate/Nickel-Zinc Oxide, PV14/NiZn2O4, as a Potential Material for Deep Oxidative Desulfurization of Fuels. Energy Fuels 2023, 37, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, H.; Ren, J.; Qu, X. Polyoxometalates: Metallodrug agents for combating amyloid aggregation. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2024, 11, nwae226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, C.-G.; Zhao, Z.-J.; Tan, T.; Yan, J.-N.; Chen, Z.-W.; Xiong, J.-T.; Li, H.-L.; Wei, Y.-H.; Hu, K.-H.; Chen, J. Lindqvist-Type Polyoxometalates Act as Anti-Breast Cancer Drugs via Mitophagy-Induced Apoptosis. Curr. Med. Sci. 2024, 44, 809–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gumerova, N.I.; Krivosudský, L.; Fraqueza, G.; Breibeck, J.; Al Sayed, E.; Tanuhadi, E.; Bijelic, A.; Fuentes Moreno, J.; Aureliano, M.; Rompel, A. The P-Type ATPase Inhibiting Potential of Polyoxotungstates. Metallomics 2018, 10, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mateos, P.S.; Ruscitti, C.B.; Casella, M.L.; Matkovic, S.R.; Briand, L.E. Phosphotungstic Wells–Dawson Heteropolyacid as a Potential Catalyst in the Transesterification of Waste Cooking Oil. Catalysts 2023, 13, 1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijelic, A.; Aureliano, M.; Rompel, A. Polyoxometalates as Potential Next-Generation Metallodrugs in the Combat Against Cancer. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 298–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.-S.; Yang, G.-Y. Recent Advances in Polyoxometalate-Catalyzed Reactions. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 4893–4962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Cui, H.; Jiang, F.; Kong, L.; Fei, B.; Mei, X. Efficient Removal of Methylene Blue Using an Organic–Inorganic Hybrid Polyoxometalate as a Dual-Action Catalyst for Oxidation and Reduction. Catalysts 2024, 14, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalilpour, H.; Shafiee, P.; Darbandi, A.; Yusuf, M.; Mahmoudi, S.; Moazzami Goudarzi, Z.; Mirzamohammadi, S. Application of polyoxometalate-based composites for sensor systems: A review. J. Compos. Compd. 2021, 3, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.-J.; Martinez Soria, L.; Gomez Romero, P. Coherent Integration of Organic Gel Polymer Electrolyte and Ambipolar Polyoxometalate Hybrid Nanocomposite Electrode in a Compact High Performance Supercapacitor. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aureliano, M.; Gumerova, N.I.; Sciortino, G.; Garribba, E.; McLauchlan, C.C.; Rompel, A.; Crans, D.C. Polyoxidovanadates’ interactions with proteins: An overview. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2022, 454, 214344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraro, G.; Vitale, L.; Sciortino, G.; Pisanu, F.; Garribba, E.; Merlino, A. Interaction of VIVO-8-hydroxyquinoline species with RNase A: The effect of metal ligands in the protein adduct stabilization. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2023, 10, 5186–5198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tito, G.; Ferraro, G.; Pisanu, F.; Garribba, E.; Merlino, A. Non-Covalent and Covalent Binding of New Mixed-Valence Cage-like Polyoxidovanadate Clusters to Lysozyme. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202406669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinda, R.; Garribba, E.; Sanna, D.; Crans, D.C.; Pessoa, J.C. Hydrolysis, Ligand Exchange, and Redox Properties of Vanadium Compounds: Implications of Solution Transformation on Biological, Therapeutic, and Environmental Applications. Chem. Rev. 2025, 125, 1468–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Watanabe, S.; Tsutsumi, A.; Kadokura, H.; Kikkawa, M.; Inaba, K. Cryo-EM Analysis Provides New Mechanistic Insight into ATP Binding to Ca2+-ATPase SERCA2b. EMBO J. 2021, 40, e108482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aureliano, M.; Fraqueza, G.; Berrocal, M.; Córdoba Granados, J.J.; Gumerova, N.I.; Rompel, A.; Gutiérrez Merino, C.; Mata, A.M. Inhibition of SERCA and PMCA Ca2+-ATPase Activities by Polyoxotungstates. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2022, 236, 111952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraqueza, G.; Ohlin, C.A.; Casey, W.H.; Aureliano, M. Sarcoplasmic Reticulum Calcium ATPase Interactions with Decaniobate, Decavanadate, Vanadate, Tungstate and Molybdate. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2012, 107, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poejo, J.; Gumerova, N.I.; Rompel, A.; Mata, A.M.; Aureliano, M.; Gutierrez-Merino, C. Unveiling the Agonistic Properties of Preyssler-Type Polyoxotungstate s on Purinergic P2 Receptors. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2024, 259, 112640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himeno, S.; Kawasaki, K.; Hashimoto, M. Preparation and Characterization of an α-Wells–Dawson-Type [V2Mo18O62]6− Complex. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2008, 81, 1465–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baur, W.H. The geometry of polyhedral distortions. Predictive relationships for the phosphate group. Acta Crystallogr. B 1974, 30, 1195–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Yu, X.; Zhen, Q.; Yu, T.; Wang, X.; Yang, G.; Song, Y.; Pang, H. Synthesis of Two New Polyoxometalate-Based Organic Complexes from 2D to 3D Structures for Improving Supercapacitor Performance. Dalton Trans. 2025, 54, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Jing, Z.; Li, K.; Chen, Y.; Li, D.; Ma, P.; Wang, J.; Niu, J. Copper-Containing Polyoxometalate-Based Metal−Organic Framework as a Catalyst for the Oxidation of Silanes: Effective Cooperative Catalysis by Metal Sites and POM Precursor. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 61, 4056–4061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, I.D.; Altermatt, D. Bond-valence parameters obtained from a systematic analysis of the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database. Acta Crystallogr. B 1985, 41, 244–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, H.; Kashino, S. Ethylammonium and Diethylammonium Salts of Chloranilic Acid. Cryst. Struct. Commun. 2000, 56, 202–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akouibaa, M.; Slassi, S.; Direm, A.; Nasif, V.; Sayin, K.; Cruciani, G.; Precisvalle, N.; Lachkar, M.; El Bali, B. mer-[Ni(dien)2]Cl2·H2O and mer-[Ni(dien)2](NO3)2 Complexes (dien = Diethylenetriamine): Synthesis, Physicochemical and Computational Studies, Antioxidant Activity, and Their Use as Pre-cursors for Ni/NiO Nanoparticle Preparation. J. Mol. Struct. 2025, 1319, 139457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maalaoui, A.; Agwamba, E.C.; Louis, H.; Mathias, G.E.; Rzaigui, M.; Akriche, S. Combined Experimental and Computational Study of V-Substituted Lindqvist Polyoxotungstate: Screening by Docking for Potential Antidiabetic Activity. Inorg. Chem. 2023, 62, 14279–14290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humelnicu, D.; Olariu, R.-I.; Sandu, I.; Apostolescu, N.; Sandu, A.V.; Arsene, C. New Heteropolyoxotungstates and Heteropolyoxomolybdates Containing Radioactive Ions (uranyl and thorium) in their Structure. Rev. Chim. 2008, 59, 920–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Téllez, C.A.; Hollauer, E.; Mondragon, M.A.; Castaño, V.M. Fourier transform infrared and Raman spectra, vibrational assignment and ab initio calculations of terephthalic acid and related compounds. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2001, 57, 667–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchida, S.; Kamata, K.; Ogasawara, Y.; Fujita, M.; Mizuno, N. Structural and dynamical aspects of alkylammonium salts of a silicodecatungstate as heterogeneous epoxidation catalysts. Dalton Trans. 2012, 41, 9979–9983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhou, J.; Chu, L.; Zhang, M.; Xu, C.; Liu, J.; Li, S. Diethylenetriamine-Functionalized Reduced Graphene Oxide Having More Amino Groups for Methylene Blue Removal. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 3280–3288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, C.; Fraqueza, G.; Carabineiro, S.A.C.; Aureliano, M. The Ca2+-ATPase Inhibition Potential of Gold(I, III) Compounds. Inorganics 2020, 8, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yatime, L.; Buch-Pedersen, M.J.; Musgaard, M.; Morth, J.P.; Winther, A.-M.L.; Pedersen, B.P.; Olesen, C.; Andersen, J.P.; Vilsen, B.; Schiøtt, B.; et al. P-Type ATPases as Drug Targets: Tools for Medicine and Science. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Bioenerg. 2009, 1787, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aureliano, M.; Gumerova, N.I.; Sciortino, G.; Garribba, E.; Rompel, A.; Crans, D.C. Polyoxovanadates with emerging biomedical activities. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 447, 214143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brini, M.; Calì, T.; Ottolini, D.; Carafoli, E. Neuronal calcium signaling: Function and dysfunction. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2014, 71, 2787–2814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, M.; Joshi, S.; Khambete, M.; Degani, M. Role of calcium dysregulation in Alzheimer’s disease and its therapeutic implications. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2023, 101, 453–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, M.; Zhang, J.; Chen, S.; Huang, Y.; Chen, W.; He, L.; Zhang, Y. Role of Calcium Homeostasis in Alzheimer’s Disease. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2020, 18, 487–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boczek, T.; Sobolczyk, M.; Mackiewicz, J.; Lisek, M.; Ferenc, B.; Guo, F.; Zylinska, L. Crosstalk among Calcium ATPases: PMCA, SERCA and SPCA in Mental Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mata, A.M.; Berrocal, M.; Marcos, D.; Sepúlveda, M.R. Impairment of PMCA Activity by Amyloid β-Peptide in Membranes from Alzheimer's Disease-Affected Brain and from Other Model Systems. Biophys. J. 2010, 98, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Drews, A.; Flint, J.; Shivji, N.; Jönsson, P.; Wirthensohn, D.; De Genst, E.; Vincke, C.; Muyldermans, S.; Dobson, C.; Klenerman, D. Individual aggregates of amyloid beta induce temporary calcium influx through the cell membrane of neuronal cells. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 31910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraqueza, G.; Fuentes, J.; Krivosudský, L.; Dutta, S.; Mal, S.S.; Roller, A.; Giester, G.; Rompel, A.; Aureliano, M. Inhibition of Na+/K+- and Ca2+-ATPase Activities by Phosphotetradecavanadate. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2019, 197, 110700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solé-Daura, A.; Poblet, J.M.; Carbó, J.J. Structure–Activity Relationships for the Affinity of Chaotropic Polyoxometalate Anions towards Proteins. Chem. Eur. J. 2020, 26, 5799–5809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciortino, G.; Aureliano, M.; Garribba, E. Rationalizing the Decavanadate(V) and Oxidovanadium(IV) Binding to G-Actin and the Competition with Decaniobate(V) and ATP. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 60, 334–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gumerova, N.I.; Al-Sayed, E.; Krivosudský, L.; Čipčić-Paljetak, H.; Verbanac, D.; Rompel, A. Antibacterial Activity of Polyoxometalates Against Moraxella catarrhalis. Sect. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 6, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Čolović, M.B.; Bajuk-Bogdanović, D.V.; Avramović, N.S.; Holclajtner-Antunović, I.D.; Bošnjaković-Pavlović, N.S.; Vasić, V.M.; Krstić, D.Z. Inhibition of rat synaptic membrane Na+/K+-ATPase and ecto-nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolases by 12-tungstosilicic and 12-tungstophosphoric acid. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2011, 19, 7063–7069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krstić, D.; Čolović, M.; Bosnjaković-Pavlović, N.; Spasojević-De Bire, A.; Vasić, V. Influence of decavanadate on rat synaptic plasma membrane ATPases activity. Gen. Physiol. Biophys. 2009, 28, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Brito, B.R.; Camilo, H.d.S.; Cruz, A.F.d.; Ribeiro, R.R.; de Sá, E.L.; Camargo de Oliveira, C.; Fraqueza, G.; Klassen, G.; Aureliano, M.; Nunes, G.G. Mixed-Valence Pentadecavanadate with Ca2+-ATPase Inhibition Potential and Anti-Breast Cancer Activity. Inorganics 2025, 13, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijelic, A.; Aureliano, M.; Rompel, A. The antibacterial activity of polyoxometalates: Structures, antibiotic effects and future perspectives. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 1153–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, F.; Aureliano, M. Polyoxometalates Impact as Anticancer Agents. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, N.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Liu, C.; Yu, D.; Ren, J.; Qu, X. Site-Directed Chemical Modification of Amyloid by Polyoxometalates for Inhibition of Protein Misfolding and Aggregation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2022, 61, e202115336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atrian-Blasco, E.; de Cremoux, L.; Lin, X.; Mitchell-Heggs, R.; Sabater, L.; Blanchard, S.; Hureau, C. Keggin-type polyoxometalates as Cu(II) chelators in the context of Alzheimer’s disease. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58, 2367–2370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaken, B.; Bouhnik, K.; Omer, R.N.; Bloch, N.; Samson, A.O. Polyoxometalates bind multiple targets involved in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2025, 30, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan, K.; Yeh, H.-L. Biological Activity of Polyoxometalates and Their Applications in Anti-Aging. Med. Res. Arch. 2024, 12, 6108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. A short history of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr. A 2008, 64, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr. C 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Assignment | (C2H8N1)6[V2Mo18O62].3·H2O | (C4H16N3)4[V2W4O19]3.12H2O |

|---|---|---|

| ν M—Ot | 935 | 1140–953 |

| νas M—Ot | 732–799 | 775 |

| νs M—Ot | 509 | 576 |

| ν O—H | 3465 | 3436 |

| δ N—H | 3017–2970 | 3029 |

| ν C—N | 2417 | 2870 |

| δ O—H | 1583 | 1621–1586 |

| δ N—H | 1460–1365 | 1511–1442 |

| δ N—C δ C—C | 1115–1212 | 1200 |

| Compounds | Net Charge | Charge Density | POM Archetype | Ca2+-ATPase IC50 (μM) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P2W18 | 6- | 0.33 | Wells-Dawson | 0.6 | [13] |

| Se2W29 | 14- | 0.48 | Wells-Dawson | 0.3 | [13] |

| CoW11Ti | 8- | 0.72 | Keggin | 4 | [13] |

| P2W12 | 12- | 1.00 | Keggin | 11 | [13] |

| SiW9 | 9- | 1.00 | Keggin | 16 | [13] |

| TeW6 | 6- | 1.00 | Anderson | 200 | [13] |

| PV14 | 9- | 0.64 | Keggin | 5.4 | [49] |

| Metf-V10 | 6- | 0.60 | Decavanadate | 87.4 | [9] |

| MnV11 | 5- | 0.42 | Keggin | 58 | [7] |

| MnV13 | 7- | 0.50 | Keggin | 31 | [7] |

| V10 | 6- | 0.60 | Decavanadate | 15 | [26] |

| P2W15 | 12- | 0.80 | Wells-Dawson | 0.5 | [25] |

| P2W17 | 10- | 0.56 | Wells-Dawson | 0.7 | [25] |

| P5W30 | 14- | 0.47 | Preyssler | 0.4 | [25] |

| P2V3W15 | 9- | 0.50 | Wells-Dawson | 1.0 | [25] |

| V2Mo18 (1) | 6- | 0.33 | Wells-Dawson | 3.4 | this study |

| V2W4O19 (2) | 4- | 0.67 | Lindqvist | 45.1 | this study |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Meskini, I.; Capet, F.; Fraqueza, G.; Dege, N.; Tahir, M.N.; Ayed, B.; Aureliano, M. Dawson- and Lindqvist-Type Hybrid Polyoxometalates: Synthesis, Characterization and Ca2+-ATPase Inhibition Potential. Molecules 2025, 30, 4334. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30224334

Meskini I, Capet F, Fraqueza G, Dege N, Tahir MN, Ayed B, Aureliano M. Dawson- and Lindqvist-Type Hybrid Polyoxometalates: Synthesis, Characterization and Ca2+-ATPase Inhibition Potential. Molecules. 2025; 30(22):4334. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30224334

Chicago/Turabian StyleMeskini, Islem, Frédéric Capet, Gil Fraqueza, Necmi Dege, Muhammad Nawaz Tahir, Brahim Ayed, and Manuel Aureliano. 2025. "Dawson- and Lindqvist-Type Hybrid Polyoxometalates: Synthesis, Characterization and Ca2+-ATPase Inhibition Potential" Molecules 30, no. 22: 4334. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30224334

APA StyleMeskini, I., Capet, F., Fraqueza, G., Dege, N., Tahir, M. N., Ayed, B., & Aureliano, M. (2025). Dawson- and Lindqvist-Type Hybrid Polyoxometalates: Synthesis, Characterization and Ca2+-ATPase Inhibition Potential. Molecules, 30(22), 4334. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30224334