Ferrocene Bis(Sulfonate) Salt as Redoxmer for Fast and Steady Redox Flow Desalination

Abstract

1. Introduction

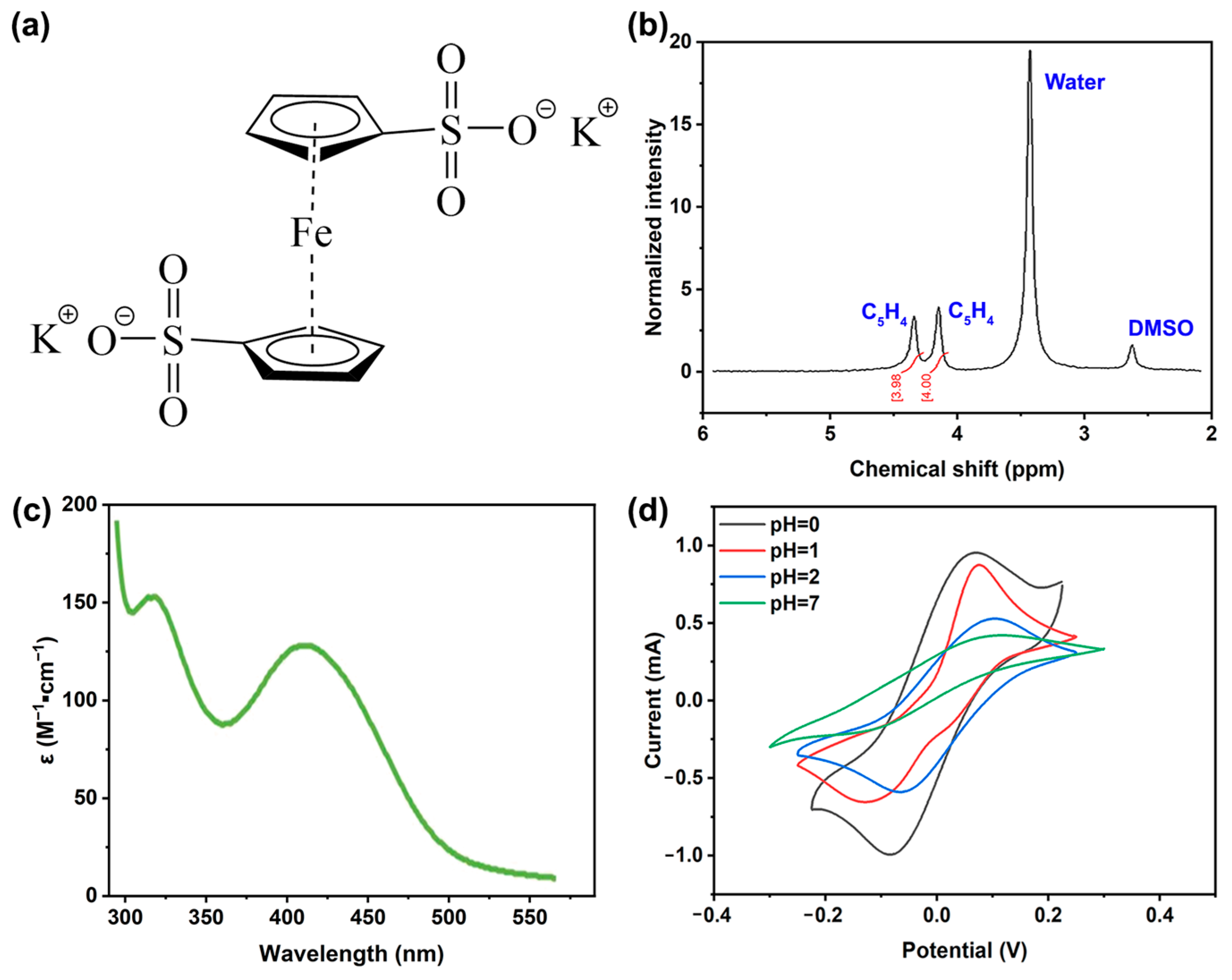

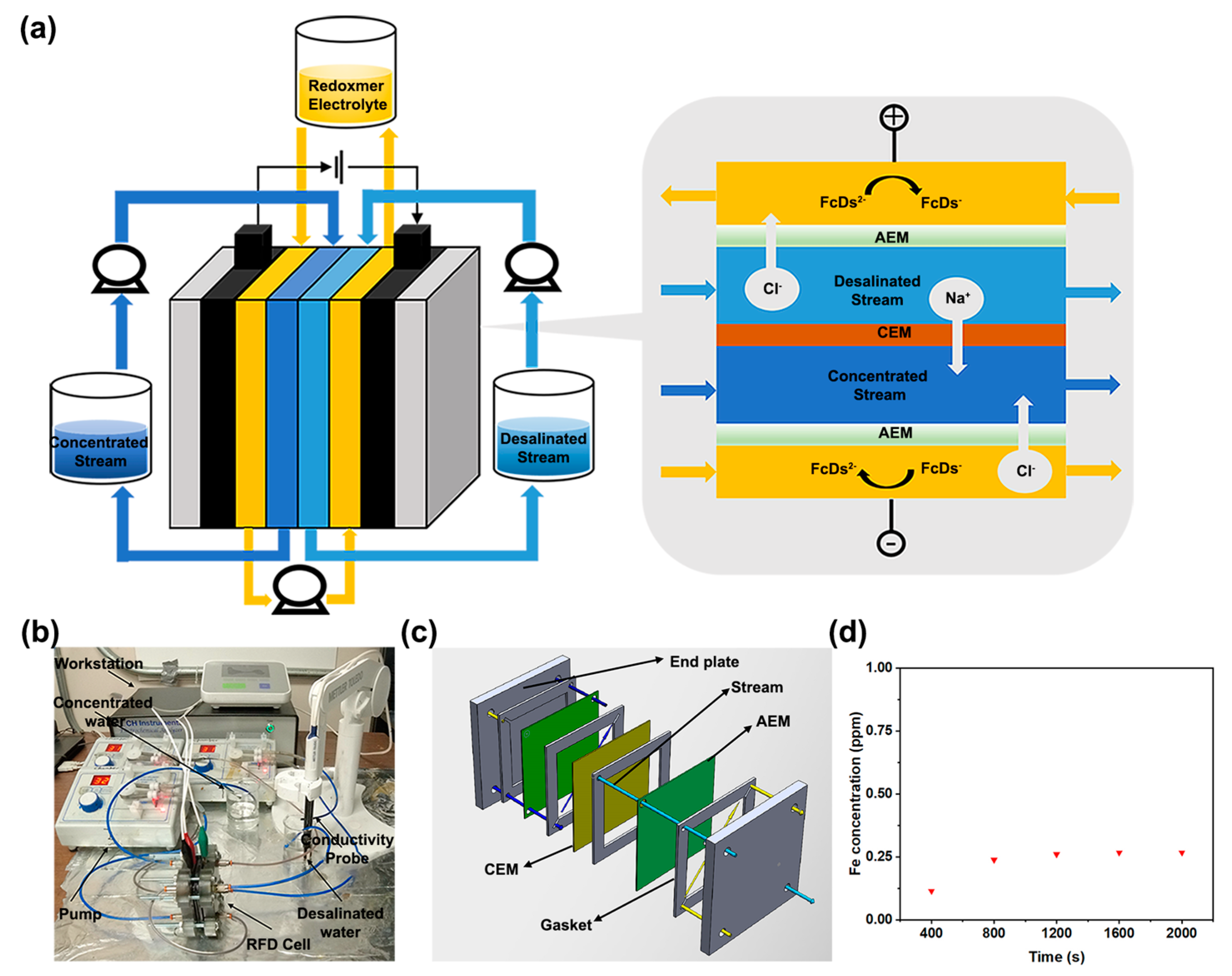

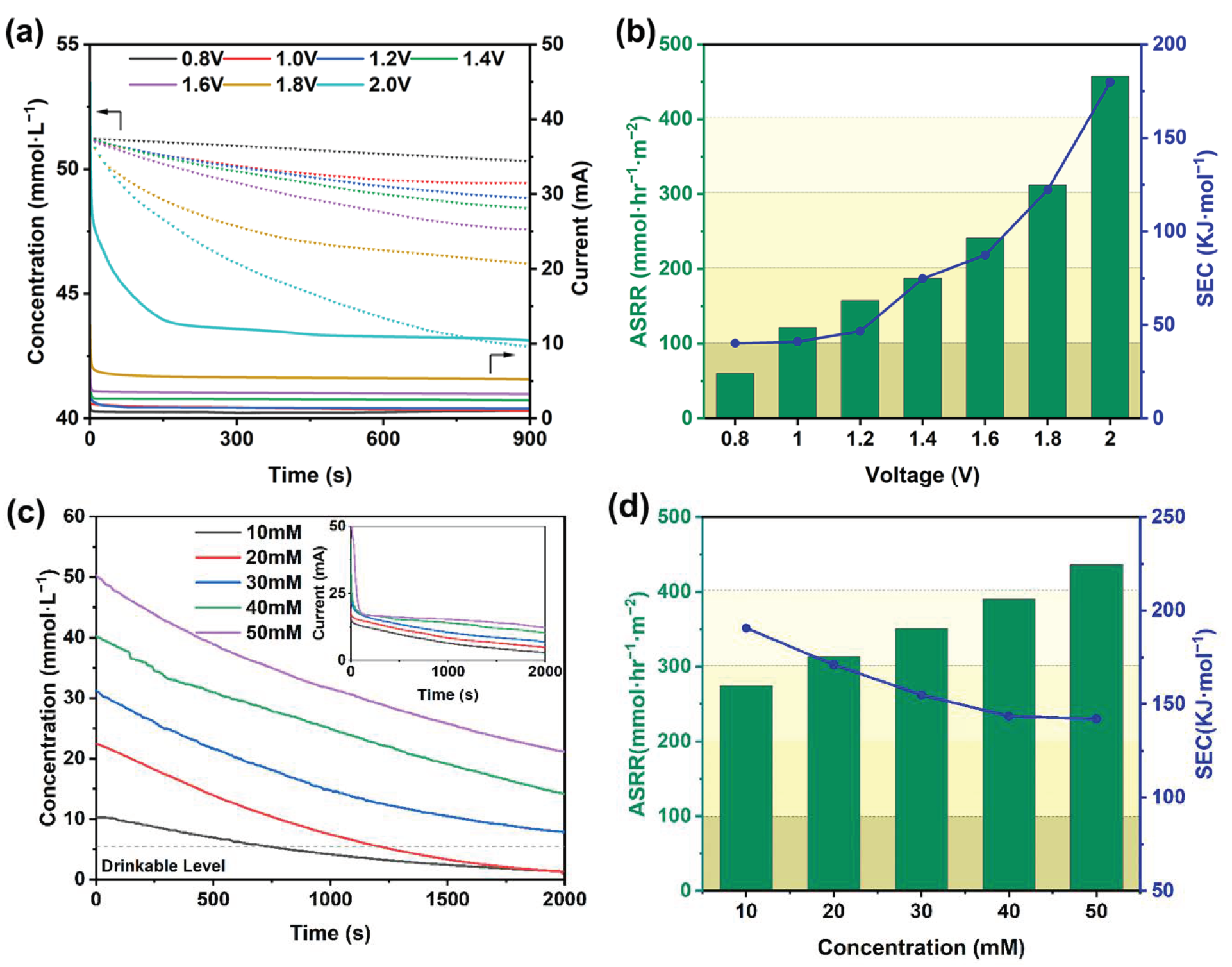

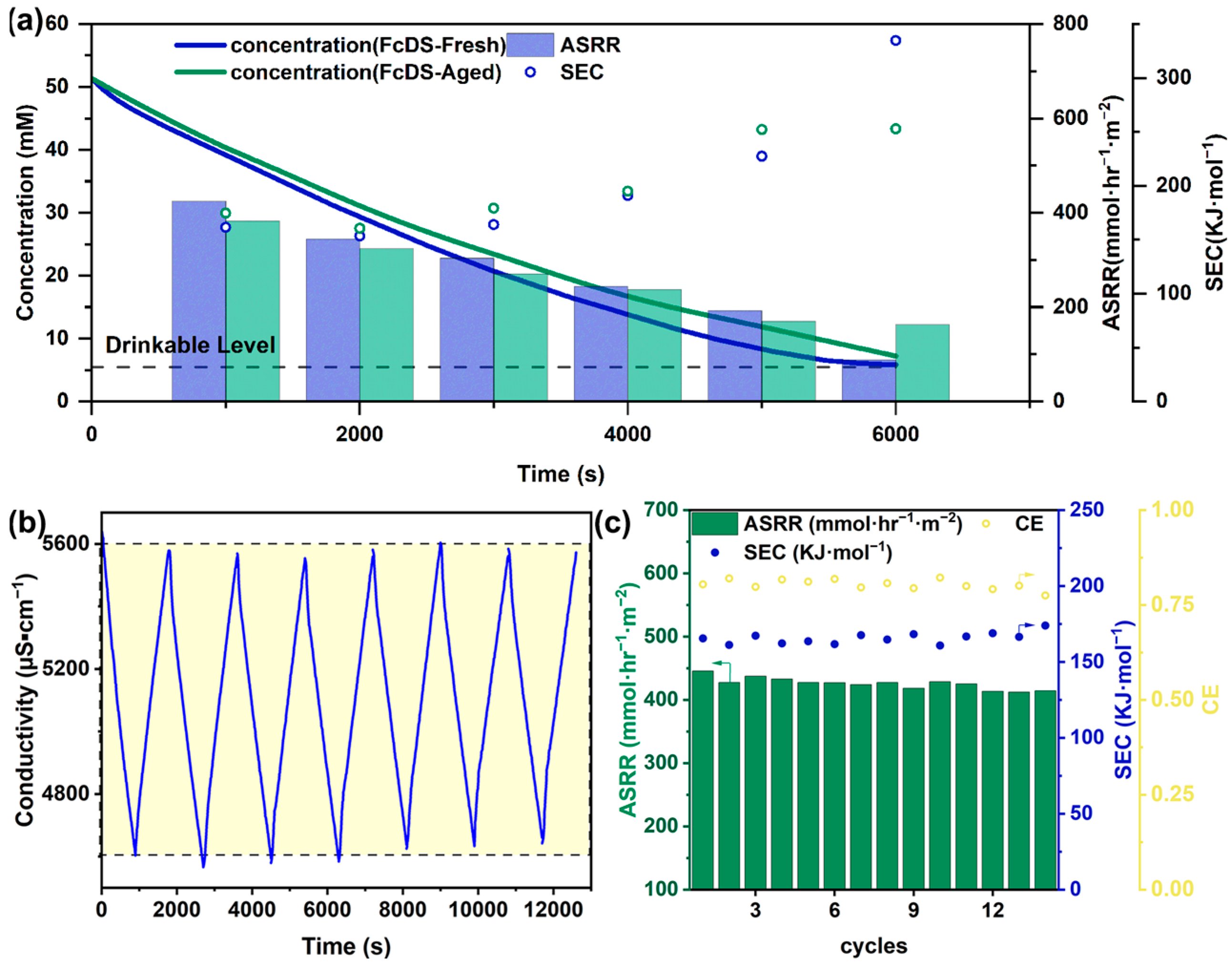

2. Results and Discussion

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Synthesis of 1,1′-FcDS

3.3. 1,1′-FcDS Redox Flow Electrodes Preparation

3.4. Salt Removal Tests

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Karagiannis, I.C.; Soldatos, P.G. Water desalination cost literature: Review and assessment. Desalination 2008, 223, 448–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rajabi, M.M.; Abumadi, F.A.; Laoui, T.; Atieh, M.A.; Khalil, K.A. Capacitive deionization for water desalination: Cost analysis, recent advances, and process optimization. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 58, 104816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darre, N.C.; Toor, G.S. Desalination of Water: A Review. Curr. Pollut. Rep. 2018, 4, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekonnen, M.M.; Hoekstra, A.Y. Four billion people facing severe water scarcity. Sci. Adv. 2016, 2, e1500323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, F.; Du, X.; Li, Y.; Cao, H.; Zhang, Y. Desalination stability of capacitive deionization using ordered mesoporous carbon: Effect of oxygen-containing surface groups and pore properties. Desalination 2015, 376, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boota, M.; Hatzell, K.B.; Alhabeb, M.; Kumbur, E.C.; Gogotsi, Y. Graphene-containing flowable electrodes for capacitive energy storage. Carbon 2015, 92, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rommerskirchen, A.; Kalde, A.; Linnartz, C.J.; Bongers, L.; Linz, G.; Wessling, M. Unraveling charge transport in carbon flow-electrodes: Performance prediction for desalination applications. Carbon 2019, 145, 507–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouhadana, Y.; Ben-Tzion, M.; Soffer, A.; Aurbach, D. A control system for operating and investigating reactors: The demonstration of parasitic reactions in the water desalination by capacitive de-ionization. Desalination 2011, 268, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, A.Z.; Mench, M.M.; Meyers, J.P.; Ross, P.N.; Gostick, J.T.; Liu, Q. Redox flow batteries: A review. J. Appl. Electrochem. 2011, 41, 1137–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, D.; Beh, E.S.; Sahu, S.; Vedharathinam, V.; van Overmeere, Q.; de Lannoy, C.F.; Jose, A.P.; Völkel, A.R.; Rivest, J.B. Electrochemical Desalination of Seawater and Hypersaline Brines with Coupled Electricity Storage. ACS Energy Lett. 2018, 3, 375–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Liang, Q.; Hu, X.; Zhou, Y.; Ru, Q.; Chen, F.; Hu, S. Coupling desalination and energy storage with redox flow electrodes. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 12308–12314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, R.; Yue, D.; Peng, Z.; Wei, X. Achieving Energy-Saving, Continuous Redox Flow Desalination with Iron Chelate Redoxmers. Energy Mater. Adv. 2023, 4, 0009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scialdone, O.; Guarisco, C.; Grispo, S.; Angelo, A.D.; Galia, A. Investigation of electrode material—Redox couple systems for reverse electrodialysis processes. Part I: Iron redox couples. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2012, 681, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, M.; Zhang, J.; Ramalingam, K.; Wei, Q.; San Hui, K.; Htike Aung, S.; Nam Hui, K.; Chen, F. Stable and efficient self-sustained photoelectrochemical desalination based on CdS QDs/BiVO4 heterostructure. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 429, 132168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhaldi, A.; Alsultan, A.; Alsaikhan, K.; Xie, R.; Li, J.; Peng, Z. Removal and Recovery of Ammonium and Phosphate from Wastewater Using a Redox Flow Deionization Cell (RFDC). ACS EST Water 2023, 3, 1182–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Xu, C.; Wang, Y.; Cai, W. Continuous desalination via redox flow desalination using sodium 4-sulfonatooxy-2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-piperidine-1-oxyl (NaSO4-TEMPO). Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 431, 133917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Yao, L.; Wu, D.; Bentalib, A.; Li, J.; Peng, Z. Sulfonated nickel phthalocyanine redox flow cell for high-performance electrochemical water desalination. Desalination 2020, 496, 114762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Zhang, B.; Schrage, B.R.; Ziegler, C.J.; Boika, A. Investigations into Aqueous Redox Flow Batteries Based on Ferrocene Bisulfonate. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2020, 3, 10270–10277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Jin, S.; Fell, E.M.; Wang, B.; Gordon, R.G.; Aziz, M.J.; Yang, Z.; Xu, T. Functioning Water-Insoluble Ferrocenes for Aqueous Organic Flow Battery via Host–Guest Inclusion. ChemSusChem 2021, 14, 745–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Li, X.; Shi, W.; Wang, Z. Highly Selective Recovery of Phosphorus from Wastewater via Capacitive Deionization Enabled by Ferrocene-polyaniline-Functionalized Carbon Nanotube Electrodes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 31962–31972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Garg, S.; Ma, J.; Waite, T.D. Selective Arsenic Removal from Groundwaters Using Redox-Active Polyvinylferrocene-Functionalized Electrodes: Role of Oxygen. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 12081–12091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nwokonkwo, O.; Pelletier, V.; Broud, M.; Muhich, C. Functionalized Ferrocene Enables Selective Electrosorption of Arsenic Oxyanions over Phosphate—A DFT Examination of the Effects of Substitutional Moieties, pH, and Oxidation State. J. Phys. Chem. A 2023, 127, 7727–7738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, F.; Shi, W.; Wang, Z. Selective Phosphorus Removal from Wastewater Using Graphene Aerogel Loaded with Ferrocene-Polyaniline: Synergetic Adsorption and Electrochemically Mediated Oxidation. ACS EST Water 2022, 2, 2602–2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayed, E.T.; Obaid, M.; Olabi, A.G.; Abdelkareem, M.A.; Al Radi, M.; Al-Dawoud, A.; Al-Asheh, S.; Ghaffour, N. Recent progress on the application of capacitive deionization for wastewater treatment. J. Water Process Eng. 2023, 56, 104379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrage, B.R.; Zhao, Z.; Boika, A.; Ziegler, C.J. Evaluating ferrocene ions and all-ferrocene salts for electrochemical applications. J. Organomet. Chem. 2019, 897, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beh, E.S.; Benedict, M.A.; Desai, D.; Rivest, J.B. A Redox-Shuttled Electrochemical Method for Energy-Efficient Separation of Salt from Water. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 13411–13417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Wang, J.; Feng, C.; Ma, J.; David Waite, T. Low energy consumption and mechanism study of redox flow desalination. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 401, 126111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, M.; Feng, K.; Karthick, R.; Zhang, L.; Shi, Y.; Hui, K.S.; Hui, K.N.; Jiang, F.; Chen, F. Photocathode-assisted redox flow desalination. Green Chem. 2020, 22, 4133–4139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; He, Q.; Ma, Z.; Yi, D.; Chen, Y.; Ma, J. In situ potential measurement in a flow-electrode CDI for energy consumption estimation and system optimization. Water Res. 2021, 203, 117522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Sun, J.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, M.; Zhang, P.; Xue, Z.; Jing, Y.; Jia, Y.; Shao, F. Lithium Isotope Electromigration Separation in an Ionic Liquid–Crown Ether System: Understanding the Role of Driving Forces. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2022, 61, 4910–4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wu, Q.; Li, J.; Qiu, S.; Cao, D.; Xu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Yu, X.; Sun, Y. Two benzoyl coumarin amide fluorescence chemosensors for cyanide anions. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2017, 183, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Song, C.; Sun, X.; Guo, H.; Zhu, G. Kinetic and isotherm studies on the electrosorption of NaCl from aqueous solutions by activated carbon electrodes. Desalination 2011, 267, 239–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Quismondo, E.; Santos, C.; Soria, J.; Palma, J.; Anderson, M.A. New Operational Modes to Increase Energy Efficiency in Capacitive Deionization Systems. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 6053–6060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stillwell, A.S.; Webber, M.E. Predicting the Specific Energy Consumption of Reverse Osmosis Desalination. Water 2016, 8, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knox, G.R.; Pauson, P.L. 134. Ferrocene derivatives. Part VII. Some sulphur derivatives. J. Chem. Soc. 1958, 692–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanawanno, K.; Holstrom, C.; Crandall, L.A.; Dodge, H.; Nemykin, V.N.; Herrick, R.S.; Ziegler, C.J. The synthesis and structures of 1,12032-bis(sulfonyl)ferrocene derivatives. Dalton Trans. 2016, 45, 14320–14326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FumaTech. Technical Datasheet—Fumasep® FKS-PET-130. 2021. Available online: https://www.bwt.com/en/-/media/bwt/fumatech/datasheets/new/fumasep/water-treatment-processes/fumasep-fkspet130-dry-formv22.pdf?rev=1916492ac05d40debe2357b9c25e7c48 (accessed on 16 May 2024).

- FumaTech. Technical Datasheet—Fumasep® FAS-PET-130. 2021. Available online: https://www.bwt.com/en/-/media/bwt/fumatech/datasheets/new/fumasep/water-treatment-processes/fumasep-faspet130-dry-formv22.pdf?rev=d8a5924b6427472289b96e8babd3f489 (accessed on 16 May 2024).

- You, D.; Feng, Z.; Wu, J.; Xiao, Z.; Li, X.; Yu, Y. Highly permselective and conductive composite anion exchange membranes QPT@PE for electrodialysis desalination. Desalination 2024, 574, 117240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, F.; Chen, Q.-B.; Wang, D.; Wang, J. A novel porous asymmetric cation exchange membrane with thin selective layer for efficient electrodialysis desalination. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 472, 144856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Shen, G.; Zhang, R.; Niu, J.; Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Liu, J.; Li, X.; Liu, C. Small particle size activated carbon enhanced flow electrode capacitive deionization desalination performances by reducing the interfacial concentration difference. Electrochim. Acta 2022, 431, 140971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yong, T.; Qi, J.; Wu, J.; Lin, R.; Chen, Z.; Li, J. Enhancing the electronic and ionic transport of flow-electrode capacitive deionization by hollow mesoporous carbon nanospheres. Desalination 2023, 550, 116381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; He, D.; Tang, W.; Kovalsky, P.; He, C.; Zhang, C.; Waite, T.D. Development of Redox-Active Flow Electrodes for High-Performance Capacitive Deionization. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 13495–13501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.; Peng, S.; Mao, Y.; Zong, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wu, D. Enhancing Brackish Water Desalination using Magnetic Flow-electrode Capacitive Deionization. Water Res. 2022, 216, 118290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Aung, S.H.; Oo, T.Z.; Chen, F. Continuous electrochemical deionization by utilizing the catalytic redox effect of environmentally friendly riboflavin-5′-phosphate sodium. Mater. Today Commun. 2020, 23, 100921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, F.; Hou, X.; Tang, Z.; Shi, Y.; Liang, P.; Yu, D.Y.W.; He, Q.; Li, L.-J. Continuous desalination with a metal-free redox-mediator. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, 13941–13947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xie, R.; Schrage, B.R.; Jiang, J.; Ziegler, C.J.; Peng, Z. Ferrocene Bis(Sulfonate) Salt as Redoxmer for Fast and Steady Redox Flow Desalination. Molecules 2024, 29, 2506. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29112506

Xie R, Schrage BR, Jiang J, Ziegler CJ, Peng Z. Ferrocene Bis(Sulfonate) Salt as Redoxmer for Fast and Steady Redox Flow Desalination. Molecules. 2024; 29(11):2506. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29112506

Chicago/Turabian StyleXie, Rongxuan, Briana R. Schrage, Junhua Jiang, Christopher J. Ziegler, and Zhenmeng Peng. 2024. "Ferrocene Bis(Sulfonate) Salt as Redoxmer for Fast and Steady Redox Flow Desalination" Molecules 29, no. 11: 2506. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29112506

APA StyleXie, R., Schrage, B. R., Jiang, J., Ziegler, C. J., & Peng, Z. (2024). Ferrocene Bis(Sulfonate) Salt as Redoxmer for Fast and Steady Redox Flow Desalination. Molecules, 29(11), 2506. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29112506