The Effects of Essential Oils on the Nervous System: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Essential Oils and Application Methods

2.2. Physiological Outcomes

2.3. Pathophysiological Outcomes

| Author | Year | Country | Study Design | Study Population | Age (Mean ± SD or Range) | Sample Size (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scuteri et al. [8] | 2022 | Italy | experimental study | male ddY mice | 2 months | 6 |

| Pereira et al. [9] | 2022 | Portugal | randomized control trial (RCT) | patients diagnosed with Breast cancer, stage I and II | 51.48 ± 10.34 years | 56 |

| Maya-Enero [10] | 2022 | Spain | RCT | neonatals | 3–6 months | 71 |

| Hawkins et al. [11] | 2022 | United States (US) | RCT | post-COVID-19 female participants | 19–49 years | 19 |

| Ebrahimi et al. [12] | 2022 | Iran | RCT | elderly participants | 72.81 ± 7.14 years | 61 |

| Du et al. [13] | 2022 | Canada | RCT | healthy university students | 22.80 years | 59 |

| Dehghan et al. [14] | 2022 | Iran | RCT | patients undergoing chronic hemodialysis | 53.66 ± 12.30 years | 86 |

| Chen et al. [15] | 2022 | Taiwan | RCT | postpartum women | >20 years | 29 |

| Atef et al. [16] | 2022 | Egypt | experimental study | male Wistar rats | 8 weeks | 50 |

| Usta et al. [17] | 2021 | Türkiye | RCT | premature babies | 24–37 weeks | 31 |

| Shammas et al. [18] | 2021 | US | RCT | patients diagnosed with breast cancer and undergoing microvascular breast reconstruction. | 32–68 years | 27 |

| Sgoifo et al. [19] | 2021 | Italy | RCT | healthy women participants | 32.70 ± 1.80 years | 20 |

| Seifritz et al. [20] | 2021 | Canada | RCT | healthy male or female participants | 18–55 years | 34 |

| Schneider [21] | 2021 | Germany | RCT | women and men participants | 34.20 ± 6.90 years | 15 |

| Mascherona et al. [22] | 2021 | Switzerland | RCT | patients diagnosed with dementia and behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) | 87.06 ± 6.95 years | 16 |

| Manor et al. [23] | 2021 | Thailand | experimental study | adult male Wistar rats | 2 months | not available (n/a) |

| Ko et al. [24] | 2021 | Taiwan | experimental study | healthy male or female participants | 22 ± 2 years | 9 |

| Karimzadeh et al. [25] | 2021 | Iran | RCT | conscious patients admitted to ICUs | 36.41 ± 12.06 years | 56 |

| Ferreira et al. [26] | 2021 | Brazil | experimental study | juveniles Oreochromis niloticus | 6 weeks | 12 |

| Takahashi et.al. [27] | 2020 | Japan | RCT | Alzheimer type dementia patients | 76.20 ± 9.80 years | 19 |

| Schneider [28] | 2020 | Germany | RCT | male or female participants | 24–52 years | 7 |

| Hacke et al. [29] | 2020 | Brazil | experimental study | adult zebrafish | 4–6 months | 14 |

| Kawai et al. [30] | 2020 | Japan | experimental study | healthy men participants | 21 ± 2.10 years | 13 |

| Bae et al. [31] | 2020 | US | RCT | recruited residents in long term care unit | 81.24 ± 11.05 years | 29 |

| Watson et al. [32] | 2019 | Australia | RCT | nursing home residents diagnosed with dementia | 89.31 ± 6.30 years | 49 |

| Son et al. [33] | 2019 | Korea | RCT | sophomore female nursing students | 20 years | 32 |

| Patra et al. [34] | 2019 | Germany | experimental study | female Suffolk sheep | 121 ± 3.70 days | 12 |

| Park et al. [35] | 2019 | Korea | quasi-experimental study | healthy female Korean participants | 21–39 years | 12 |

| Felipe et al. [36] | 2019 | Brazil | experimental study | male Swiss albino mice | 2 months | 6 |

| Xiong et al. [37] | 2018 | China | RCT | community-dwelling adults with symptoms of depression | 67.87 ± 7.51 years | 20 |

| Vital et al. [38] | 2018 | Brazil | experimental study | students, employers, and visitors | group of age 18–24, 25–39, 40–54, and >55 years | 10 |

| Van Dijk et al. [39] | 2018 | South Africa | RCT | children admitted to the burns unit | 0–13 years | 110 |

| Senturk and Kartin [40] | 2018 | Türkiye | RCT | hemodialysis patients | ≥30 years | 17 |

| Qadeer et al. [41] | 2018 | Pakistan | experimental study | locally breed albino Wistar rats | 2 months | 6 |

| Moss et al. [42] | 2018 | United Kingdom (UK) | RCT | healthy female and male adults | 22.84 ± 3.95 years | 40 |

| Montibeler et al. [43] | 2018 | Brazil | RCT | female nursing team of a surgical center | 39.50 ± 9.87 years | 19 |

| Kennedy et al. [44] | 2018 | UK | RCT | male or female participants | 21–35 years | 24 |

| Kalayasiri et al. [45] | 2018 | Thailand | RCT | male participants with inhalant dependence | 27.9 ± 5.77 years | 17 |

| Brnawi et al. [46] | 2018 | US | experimental study | male or female participants | 36 ± 14 or 21–65 years | 75 |

| Mosaffa-Jahromi et al. [47] | 2017 | Iran | RCT | participants with irritable bowel syndrome with mild to moderate depression | 34.15 ± 9.29 years | 40 |

| Matsumoto et al. [48] | 2017 | Japan | RCT | women with subjective premenstrual symptoms | 20.60 ± 0.20 years | 10 |

| Lam et al. [49] | 2017 | Hongkong | in vitro study | pheochromocytoma PC12 cells | - | 3 |

| Karadag et al. [50] | 2017 | Türkiye | RCT | male and female patients in coronary ICU | 50.33 ± 12.14 years | 30 |

| Huang and Capdevila [6] | 2017 | Spain | RCT | administrative university workers | 42.21 ± 7.12 years | 42 |

| Goepfert et al. [51] | 2017 | Germany | RCT | conscious and non-conscious palliative patients | 42−84 years | 20 |

| Forte et al. [52] | 2017 | Italy | experimental study | pigs | 35–220 days | 72 |

| Chen et al. [53] | 2017 | Taiwan | RCT | healthy pregnant women | 33.31 ± 4.01 or 24–43 years | 24 |

| Kasper et al. [54] | 2016 | Germany | RCT | male and female outpatients diagnosed with mixed anxiety and depressive disorder | 18–65 years | 160 |

| Gaston et al. [55] | 2016 | Argentina | experimental study | male and female meat-type chicks | 1 day old | 16 |

| Dyer et al. [56] | 2016 | UK | experimental study | patients diagnosed with sleep problems | 16–84 years | 65 |

| Yoshiyama et al. [57] | 2015 | Japan | RCT | patients with mild to moderate dementia in a nursing home | ≥65 years | 7 |

| Watanabe et al. [58] | 2015 | Japan | RCT | healthy females | 21.3 ± 1.02 or 20–23 years | 7 |

| Kasper et al. [59] | 2015 | Germany | RCT | male and female out-patients with a diagnosis of restlessness | 18–65 years | 86 |

| Hasanein and Riahi [60] | 2015 | Iran | experimental study | locally bred male Wistar rats | 2 months | 8 |

| Chen et al. [61] | 2015 | Taiwan | quasi-experimental study | healthy adults | 20–21 years | 16 |

| Bikmoradi et al. [62] | 2015 | Iran | RCT | patients undergone coronary artery bypass graft | 65.13 ± 9.76 years | 30 |

| Nagata et al. [63] | 2014 | Japan | RCT | male and female asymptomatic participants undergoing screening computed tomography colonography | 45–59 years | 56 |

| Matsumoto et al. [64] | 2014 | Japan | RCT | healthy women participants | 20.50 ± 0.10 years | 20 |

| Koteles and Babulka [65] | 2014 | Hungary | quasi-experimental study | male adult participants | 37.70 ± 10.90 years | 33 |

| Kasper et al. [66] | 2014 | Germany | RCT | male and female with generalized anxiety disorder | 18–65 years | 128 |

| Igarashi et al. [67] | 2014 | Japan | quasi-experimental study | female university and graduate students | 21.60 ± 1.50 or 19–26 years | 19 |

| Baldinger et al. [68] | 2014 | Austria | RCT | healthy participants | 25.60 ± 3.70 years | 17 |

| Varney and Buckle [69] | 2013 | US | RCT | male and female participants | 25–45 years | 7 |

| Taavoni et al. [70] | 2013 | Iran | RCT | postmenopausal participants | 45–62 years | 30 |

| Seol et al. [71] | 2013 | Korea | RCT | female patients diagnosed with urinary incontinence | 33–75 years | 12 |

| Igarashi [72] | 2013 | Japan | RCT | 28-week-pregnant women | 29.30 ± 4.30 years | 6 |

| Han et al. [73] | 2013 | China | experimental study | male ICR mice | 2 months | 10 |

| Fu et al. [74] | 2013 | Australia | RCT | patients diagnosed with dementia | 84 ± 6.36 years | 22 |

| Brito et al. [75] | 2013 | Brazil | experimental study | male adult albino Swiss mice | 3 months | 6 |

| Apay et al. [76] | 2012 | Türkiye | quasi-experimental study | midwifery and nursing students | 20.31 ± 1.09 years | 44 |

| Author | Essential Oils | Application Methods | Measures | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Du et al. [13] | lemon and grapeseed | inhaled | cognitive function tests | shortened reaction time response, more impulsive decision-making |

| Dehghan et al. [14] | lavender, rosemary, and orange | inhaled | retrospective and prospective memory scale | only lavender or rosemary can reduce some memory problems in hemodialysis patients by reduction of retrospective memory problems |

| Sgoifo et al. [19] | Juniperus phoenicea gum extract, Copaifera officinalis (Balsm Copaiba) resin, Aniba rosaeodora (Rosewood) wood oil and Juniperus virginiana oil | dermal | psychological questionnaires (anxiety, perceived stress, and mood profile), autonomic parameters (heart rate (HR) and heart rate variability (HRV)), and neuroendocrine (salivary cortisol) measurements | stress resilience due to favorable physiological, neuroendocrine, and psychological effects |

| Schneider [21] | peppermint, rosemary, grapefruit, and cinnamon | inhaled | vigilance test using computerized attention and concentration tests | improved vigilance |

| Manor et al. [23] | lavender | inhaled | electroencephalogram (EEG) | distinct anxiolytic-like effects and sleep enhancing purpose |

| Ko et al. [24] | lavender | inhaled | sleep laboratory: EEG, electromyogram (EMG) and electrooculogram (EOG) signals | improved subjective and objective sleep qualities |

| Kawai et al. [30] | grapefruit | inhaled | muscle sympathetic nerve activity (MSNA), blood pressure (BP), heart rate (HR), and cortisol concentration | changed in BP, muscle sympathetic nerve activity changed, decreased stress hormone (cortisol) concentration |

| Park et al. [35] | lavender, peppermint, and coffee | inhaled | quantitative and objective EEG and the questionnaire | stabilized for lavender and aroused for peppermint and coffee |

| Vital et al. [38] | oregano and rosemary | inhaled/oral | a 9-point scale | higher consumer acceptance and willingness to buy |

| Moss et al. [42] | rosemary | oral | computerized cognitive tasks | enhance cognition |

| Montibeler et al. [43] | lavender and geranium | massage | biophysiological and psychological parameters | reduction in heart rate and blood pressure levels after massage sessions |

| Kennedy et al. [44] | spearmint and peppermint | oral | neurotransmitter receptor binding, acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibition, mood scales, and standardized cognitively demanding tasks | peppermint with high levels of menthol characteristic as in vitro cholinergic inhibitory, calcium regulatory, GABA/nicotinic binding/modulated performance on demanding cognitive task/attenuated the increase in mental fatigue associated with extended cognitive task |

| Brnawi et al. [46] | cinnamon bark and leaf | oral | a 9-point hedonic scale | natural antimicrobial ingredient in milk beverages—sensory aspect |

| Matsumoto et al. [48] | yuzu and lavender | inhaled | heart rate variability and the profile of mood states (POMS) questionnaire | alleviated premenstrual emotional symptoms and improved parasympathetic nervous system activity |

| Huang and Capdevila [6] | petitgrain | inhaled | the stait–trait anxiety inventory (STAI) questionnaire, POMS questionnaire, and HRV | improved performance in the workplace-autonomic balance, reduced stress level, and increased arousal level-attentiveness-alertness |

| Goepfert et al. [51] | lemon and lavender | inhaled | physiological parameters: respiratory rate (RR), heart rate (HR), systolic (SBP) and diastolic pressure (DBP) | lemon increased RR, HR, DBP, and lavender decreased RR |

| Forte et al. [52] | oregano | oral | sensory analysis of the consumer tests | improved consumer perception of the meat quality |

| Chen et al. [53] | lavender | massage | salivary cortisol and immune function measurements | decreased stress and enhanced immune function |

| Watanabe et al. [58] | bergamot | inhaled | salivary cortisol level | lower salivary cortisol compared to rest |

| Chen et al. [61] | Meniki and Hinoki wood | inhaled | subject’s BP, HR, HRV, sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system (SNS and PSNS), and POMS questionnaire | simulated a pleasant mood status-regulators of sympathetic nervous system dysfunctions |

| Bikmoradi et al. [62] | lavender | inhaled | DASS-21 questionnaire, HR, RR, SBP and DBP | no effects on mental stress and vital signs in patients following coronary bypass surgery (CABG), but has possibly significant effect on systolic blood pressure of patients |

| Nagata et al. [63] | bergamot | inhaled | a visual analog scale | showed little effect on pain, discomfort, vital signs, as well as preferred music and aroma during the next computed tomography (CT) |

| Matsumoto et al. [64] | yuzu | inhaled | POMS questionnaire and salivary chromogranin A | alleviated negative emotional stress-suppression of sympathetic nervous system activity |

| Koteles and Babulka [65] | rosemary, lavender, and eucalyptus | inhaled | EEG, HR, BP, HRV and self-reported questions and statements alertness, pleasantness, expectations, and perceived effect | no effect on any assessed variables (HR, BP, and HRV) and perceived subjective changes-non-conscious states |

| Igarashi et al. [67] | rose | inhaled | HRV and subjective evaluations | induced physiological–psychological relaxation |

| Baldinger et al. [68] | lavender | oral | positron emission tomography (PET) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) measurements | the anxiolytic effects of Silexan via serotonin-1A receptor |

| Igarashi [72] | lavender, petitgrain, and bergamot | inhaled | POMS questionnaire and autonomic nervous system parameters | no major differences observed between the two groups but essential oils containing linalyl acetate and linalool effective for the POMS and parasympathetic nerve activity based on an intragroup comparison |

| Brito et al. [75] | citronellol | paw injection | nociceptive test | attenuated orofacial pain |

| Son et al. [33] | sweet marjoram and sweet orange | inhaled | participants’ Foley catheterization skill, the Korean version of the revised test anxiety scale, and a numeric rating score | improved the performance of fundamental nursing skills and reduced anxiety and stress |

| Author | Essential Oils | Application Methods | Measures | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scuteri et al. [8] | bergamot | inhaled | licking/biting behavior | analgesic properties |

| Pereira et al. [9] | bergamot, geranium, and mountain pepper | inhaled | the relationship between anxiety, depression, and quality of life (primary outcomes), as well as the impact of hedonic aroma | long-term emotional and quality of life-related adjustment |

| Maya-Enero [10] | lavender | inhaled | pain assessment | decreased crying time |

| Hawkins et al. [11] | thyme, orange peel, clove bud, and frankincense | inhaled | multidimensional fatigue symptom inventory | lowered fatigue score |

| Ebrahimi et al. [12] | lavender and chamomile | inhaled | the depression, anxiety, and DASS stress-scale | both lavender and chamomile essential oils helped decrease depression, anxiety, and stress levels |

| Chen et al. [15] | bergamot | inhaled | questionnaire including the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale and postpartum sleep quality scale (PSQS) | alleviated depressive mood in postpartum |

| Usta et al. [17] | lavender | inhaled | pain scores | pain control in premature infants during heel lancing |

| Shammas et al. [18] | lavender | inhaled | hospital anxiety and depression scale, Richards–Campbell sleep questionnaire, and the visual analogue scale for quantifying stress, anxiety, depression, sleep, and pain | no measurable advantages in breast reconstruction |

| Sgoifo et al. [19] | Juniperus phoenicea gum extract, Copaifera officinalis (Balsm Copaiba) resin, Aniba rosaeodora (Rosewood) wood oil and Juniperus virginiana oil | topical | psychological questionnaires (anxiety, perceived stress, and mood profile), autonomic parameters (heart rate (HR) and heart rate variability (HRV)), and neuroendocrine (salivary cortisol) measurements | stress resilience due to favorable physiological, neuroendocrine and psychological effects |

| Seifritz et al. [20] | lavender | oral | a short form of the addiction research center inventory (visual analogue scales assessing positive, negative, and sedative drug effects) | no abuse potential |

| Mascherona et al. [22] | lavender and sweet orange | inhaled | measures the stress felt by professional caregiver using Italian version of the NPI-NH scale | might improve wellbeing of patients and caregivers |

| Karimzadeh et al. [25] | lavender and citrus | inhaled | the state subscale of State-Trait Anxiety Inventory | reduced the anxiety of patients admitted to ICUs |

| Ferreira et al. [26] | Ocimum gratissimum | water medication /immersion | the time of anesthesia induction and recovery during anesthesia of Oreochromis niloticus exposed to essential oil of Ocimum gratissimum | reduced the stress of transport, and improved the oxidative status of Oreochromis niloticus by stable plasma glucose and change antioxidant defense system by increasing hepatic and kidney ROS |

| Takahashi et.al. [27] | cedar | inhaled | the neuropsychiatric inventory (NPI), the Japanese version of Zarit Caregiver Burden interview (J-ZBI), and the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale-cognitive subscale (ADAS-cog). | improved behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia |

| Hacke et al. [29] | lemongrass, pure citral and geraniol | water medication/immersion | the light–dark test | anxiolytic effect |

| Bae et al. [31] | lavender | inhaled | the geriatric depression scale (GDS) | positive distraction during the healing process-theory of supportive design |

| Watson et al. [32] | lavender and lemon balm | inhaled | NPI and Cohen-Mansfield agitation inventory (CMAI) | reduced agitated behavior in residents without dementia, but no reduction with treatments when compared to placebo independent of cognitive groups |

| Xiong et al. [37] | lavender, sweet orange, and bergamot | massage | the geriatric depression scale (GDS) | intervened depression in older adults |

| Van Dijk et al. [39] | chamomile, lavender, and neroli | massage | the behavioral relaxation scale and the COMFORT behavior scale | not effective in reducing stress of children with burns |

| Senturk and Kartin [40] | lavender | inhaled | Pittsburgh sleep quality index, the Hamilton anxiety assessment scale, and visual analog scale for daytime sleepiness level | improved sleep problems and anxiety for dialysis nurses |

| Kalayasiri et al. [45] | lavender and synthetic oil | inhaled | the modified version of Penn alcohol craving score for inhalants | reduced inhalant craving |

| Mosaffa-Jahromi et al. [47] | anise | oral | the Beck Depression Inventory Scale II | reduction of total score of Beck Depression Inventory II in depressed patients with irritable bowel syndrome |

| Matsumoto et al. [48] | yuzu and lavender | inhaled | HRV and the profile of mood states (POMS) questionnaire | alleviated premenstrual emotional symptoms and improved parasympathetic nervous system activity |

| Karadag et al. [50] | lavender | inhaled | Pittsburgh sleep quality index and the Beck anxiety inventory scale. | increased quality of sleep and reduced level of anxiety in coronary artery disease patient |

| Kasper et al. [54] | lavender | oral | Hamilton anxiety rating scale and the Montgomery Asberg depression rating scale | improved impaired daily living skills and health-related quality of life |

| Dyer et al. [56] | bergamot, sandalwood, frankincense, mandarin, lavender, orange sweet, petitgrain, lavandin, mandarin, bergamot, lavender, and roman chamomile. | inhaled | a patient questionnaire | improved Likert scale measuring sleep quality |

| Yoshiyama et al. [57] | bitter orange leaf, Cymbopogon martini, Picea mariana, lavender, damask rose, grapefruit, and lemon balm | massage | behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) and activities of daily living (ADLs) | no improvement of BPSD-ADLs with dementia |

| Kasper et al. [59] | lavender | oral | the Hamilton anxiety rating scale, Pittsburgh sleep quality index, and the Zung Self-rating anxiety scale | calming and anxiolytic efficacy |

| Hasanein and Riahi [60] | lemon balm | injection | nociceptive test | treatment of painful diabetic neuropathy |

| Bikmoradi et al. [62] | lavender | inhaled | DASS-21 questionnaire, HR, RR, systolic (SBP) and diastolic pressure (DBP) | no effects on mental stress and vital signs in patients following coronary bypass surgery (CABG), but has a possibly significant effect on systolic blood pressure in patients |

| Nagata et al. [63] | bergamot | inhaled | a visual analog scale | showed little effect on pain, discomfort, vital signs, as well as preferred music and aroma during the next CT |

| Kasper et al. [66] | lavender | oral | Hamilton anxiety scale, Covi anxiety scale, Hamilton rating scale for depression, and clinical and global impressions | antidepressant effect/improved general mental health–health-related quality of life |

| Baldinger et al. [68] | lavender | oral | PET and MRI measurements | the anxiolytic effects of Silexan via serotonin-1A receptor |

| Varney and Buckle [69] | jojoba oil, peppermint, basil, and helichrysum | inhaled | self-assessed mental exhaustion or burnout | might reduce the perceived level of mental fatigue or burnout |

| Taavoni et al. [70] | lavender, geranium, rose, and rosemary | massage | the menopause rating scale | reduced psychological symptoms |

| Seol et al. [71] | Salvia sclarea and lavender | inhaled | a questionnaire | lowered stress during urodynamic examinations and induced relaxation in female urinary incontinence patients undergoing urodynamic assessments |

| Fu et al. [74] | lavender | inhaled | mini mental state examination and the CMAI short form | reduced disruptive behavior |

| Apay et al. [76] | lavender | massage | visual analog scale | effect of aromatherapy massage on pain was higher than that of placebo massage |

2.4. Mechanism Studies from Basic Research

| Author | Essential Oils | Application Methods | Measures | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scuteri et.al. [8] | bergamot | inhaled | licking/biting behavior | analgesic properties |

| Du et al. [13] | lemon and grapeseed | inhaled | cognitive function tests | shortened reaction time response, and more impulsive decision-making. |

| Dehghan et al. [14] | lavender, rosemary, and orange | inhaled | retrospective and prospective memory scale | only lavender or rosemary could reduce some memory problems in hemodialysis patients by reduction of retrospective memory problems |

| Chen et al. [15] | bergamot | inhaled | a questionnaire including the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale and postpartum sleep quality scale (PSQS) | alleviated depressive mood in postpartum |

| Atef et al. [16] | geraniol | oral | Morris water maze test | shortened escape latency and increased platform crossing |

| Ferreira et al. [26] | Ocimum gratissimum | water medication (immersion) | the time of anesthesia induction and recovery during anesthesia of Oreochromis niloticus exposed to essential oil of Ocimum gratissimum | reduced the stress of transport and improved the oxidative status of Oreochromis niloticus by stable plasma glucose and change antioxidant defense system by increasing hepatic and kidney ROS |

| Schneider [28] | peppermint, rosemary, and grapefruit | inhaled | the hot immersion test paradigm and physiological parameters | resisted a stressful thermal stimulus and increased HRV |

| Hacke et al. [29] | lemongrass, pure citral and geraniol | water medication (immersion) | the light–dark test | anxiolytic effect |

| Kawai et al. [30] | grapefruit | inhaled | muscle sympathetic nerve activity (MSNA), blood pressure (BP), heart rate (HR), and cortisol concentration | changed in BP and MSNA as well as decreased stress hormone cortisol |

| Felipe et al. [36] | alpha-pinene and beta-pinene | oral | determination of dopamine and norepinephrine content, thiobarbituric acid reactive substances, and nitrite concentration | reduced nitrite level and norepinephrine and dopamine (NE-DA) content during pentylenetetrazole-induced seizure |

| Qadeer et al. [41] | lavender | oral | open field test (OFT), light/dark transition box activity, forced swim test (FST) and corticosterone, lipid peroxidation, and endogenous antioxidant enzymes activities | stress induced behavior and biochemical alteration in rats |

| Kennedy et al. [44] | spearmint and peppermint | oral | neurotransmitter receptor binding, acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibition, mood scales, and a standardised cognitively demanding tasks | peppermint with menthol showed in vitro cholinergic inhibitory, calcium regulatory, GABA, nicotinic binding effect; modulated performance on demanding cognitive task; attenuated the increase in mental fatigue associated with extended cognitive task |

| Lam et al. [49] | Acori Tatarinowii Rhizoma, Acori Graminei Rhizoma, and Acori Calami Rhizoma | exposure in cell culture media | transcriptional activation of neurofilament promoters and the neurite outgrowth | potentiated nerve growth factor (NGF)-induced neuronal differentiation in PC12 and neurite outgrowth-neurofilament expression |

| Chen et al. [53] | lavender | massage | salivary cortisol and Immune function measures | decreased stress and enhanced immune function |

| Gaston et al. [55] | Coriandrum sativum | intracerebroventricular injection | OFT test | sedative effect |

| Watanabe et al. [58] | bergamot | inhaled | salivary cortisol level | lowered salivary cortisol compared to rest |

| Hasanein and Riahi [60] | lemon balm | injection | nociceptive test | treatment of painful diabetic neuropathy |

| Matsumoto et al. [64] | yuzu | inhaled | the profile of mood states (POMS) questionnaire and salivary chromogranin A | alleviated negative emotional stress-suppression of sympathetic nervous system activity |

| Han et al. [73] | Acorus tatarinowii Schott | injection/intraperitoneal | OFT, FST, and tail suspension test (TST) | essential oils and asarones from the rhizomes of Acorus tatarinowii could be considered as a new therapeutic agent for curing depression |

| Brito et al. [75] | citronellol | paw injection | nociceptive test | attenuated orofacial pain |

3. Discussion

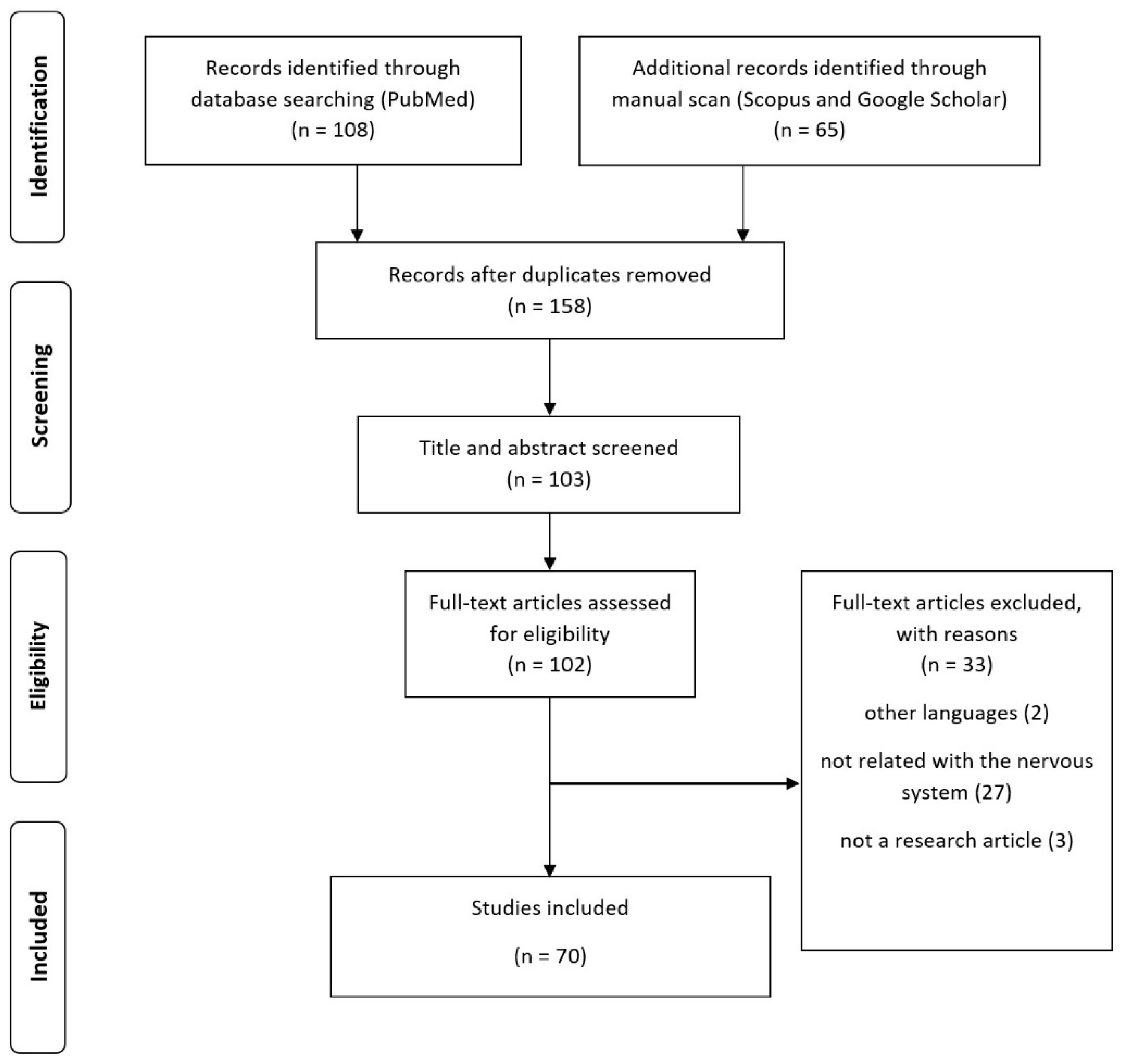

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Question

4.2. Search Strategy

4.3. Study Selection

4.4. Data Charting Process

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Herman, R.A.; Ayepa, E.; Shittu, S.; Fometu, S.S.; Wang, J. Essential oils and their applications-a mini review. Adv. Nutr. Food Sci. 2019, 4, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Fokou, J.B.H.; Dongmo, P.M.J.; Boyom, F.F. Essential oil’s chemical composition and pharmacological properties. In Essential Oils-Oils of Nature; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2020; pp. 13–36. [Google Scholar]

- Sell, C. Chemistry of essential oils. In Handbook of Essential Oils; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020; pp. 161–189. [Google Scholar]

- Mehdizadeh, L.; Moghaddam, M. Essential Oils: Biological Activity and Therapeutic Potential. In Therapeutic, Probiotic, and Unconventional Foods; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; pp. 167–179. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.S.; Choi, J.; Posadzki, P.; Ernst, E. Aromatherapy for health care: An overview of systematic reviews. Maturitas 2012, 71, 257–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Capdevila, L. Aromatherapy Improves Work Performance Through Balancing the Autonomic Nervous System. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2017, 23, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angelucci, F.; Silva, V.; Dal Pizzol, C.; Spir, L.; Praes, C.; Maibach, H. Physiological effect of olfactory stimuli inhalation in humans: An overview. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2014, 36, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scuteri, D.; Rombolà, L.; Hayashi, T.; Watanabe, C.; Sakurada, S.; Hamamura, K.; Sakurada, T.; Tonin, P.; Bagetta, G.; Morrone, L.A.; et al. Analgesic Characteristics of NanoBEO Released by an Airless Dispenser for the Control of Agitation in Severe Dementia. Molecules 2022, 27, 4987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, M.; Moreira, C.S.; Izdebski, P.; Dias, A.C.P.; Nogueira-Silva, C.; Pereira, M.G. How Does Hedonic Aroma Impact Long-Term Anxiety, Depression, and Quality of Life in Women with Breast Cancer? A Cross-Lagged Panel Model Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maya-Enero, S.; Fàbregas-Mitjans, M.; Llufriu-Marquès, R.M.; Candel-Pau, J.; Garcia-Garcia, J.; López-Vílchez, M. Analgesic effect of inhaled lavender essential oil for frenotomy in healthy neonates: A randomized clinical trial. World J. Pediatr. 2022, 18, 398–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, J.; Hires, C.; Keenan, L.; Dunne, E. Aromatherapy blend of thyme, orange, clove bud, and frankincense boosts energy levels in post-COVID-19 female patients: A randomized, double-blinded, placebo controlled clinical trial. Complement. Ther. Med. 2022, 67, 102823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, H.; Mardani, A.; Basirinezhad, M.H.; Hamidzadeh, A.; Eskandari, F. The effects of Lavender and Chamomile essential oil inhalation aromatherapy on depression, anxiety and stress in older community-dwelling people: A randomized controlled trial. Explore 2022, 18, 272–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, B.; Schwartz-Narbonne, H.; Tandoc, M.; Heffernan, E.M.; Mack, M.L.; Siegel, J.A. The impact of emissions from an essential oil diffuser on cognitive performance. Indoor Air 2022, 32, e12919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghan, N.; Azizzadeh Forouzi, M.; Etminan, A.; Roy, C.; Dehghan, M. The effects of lavender, rosemary and orange essential oils on memory problems and medication adherence among patients undergoing hemodialysis: A parallel randomized controlled trial. Explore 2022, 18, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.L.; Chen, Y.E.; Lee, H.F. The Effect of Bergamot Essential Oil Aromatherapy on Improving Depressive Mood and Sleep Quality in Postpartum Women: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Nurs. Res. 2022, 30, e201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atef, M.M.; Emam, M.N.; Abo El Gheit, R.E.; Elbeltagi, E.M.; Alshenawy, H.A.; Radwan, D.A.; Younis, R.L.; Abd-Ellatif, R.N. Mechanistic Insights into Ameliorating Effect of Geraniol on D-Galactose Induced Memory Impairment in Rats. Neurochem. Res. 2022, 47, 1664–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usta, C.; Tanyeri-Bayraktar, B.; Bayraktar, S. Pain Control with Lavender Oil in Premature Infants: A Double-Blind Randomized Controlled Study. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2021, 27, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shammas, R.L.; Marks, C.E.; Broadwater, G.; Le, E.; Glener, A.D.; Sergesketter, A.R.; Cason, R.W.; Rezak, K.M.; Phillips, B.T.; Hollenbeck, S.T. The Effect of Lavender Oil on Perioperative Pain, Anxiety, Depression, and Sleep after Microvascular Breast Reconstruction: A Prospective, Single-Blinded, Randomized, Controlled Trial. J. Reconstr. Microsurg. 2021, 37, 530–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgoifo, A.; Carnevali, L.; Pattini, E.; Carandina, A.; Tanzi, G.; Del Canale, C.; Goi, P.; De Felici del Giudice, M.B.; De Carne, B.; Fornari, M.; et al. Psychobiological evidence of the stress resilience fostering properties of a cosmetic routine. Stress 2021, 24, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifritz, E.; Möller, H.J.; Volz, H.P.; Müller, W.E.; Hopyan, T.; Wacker, A.; Schläfke, S.; Kasper, S. No Abuse Potential of Silexan in Healthy Recreational Drug Users: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2021, 24, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, R. Natural Odor Inhalers (AromaStick®) Outperform Red Bull® for Enhancing Cognitive Vigilance: Results From a Four-Armed, Randomized Controlled Study. Percept. Mot. Ski. 2021, 128, 135–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascherona, I.; Ferretti, M.; Soldini, E.; Biggiogero, M.; Maggioli, C.; Fontana, P.E. Essential oil therapy for the short-term treatment of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia: A monocentric randomized pilot study. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2021, 33, 2251–2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manor, R.; Kumarnsit, E.; Samerphob, N.; Rujiralai, T.; Puangpairote, T.; Cheaha, D. Characterization of pharmaco-EEG fingerprint and sleep-wake profiles of Lavandula angustifolia Mill. essential oil inhalation and diazepam administration in rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 276, 114193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, L.W.; Su, C.H.; Yang, M.H.; Liu, S.Y.; Su, T.P. A pilot study on essential oil aroma stimulation for enhancing slow-wave EEG in sleeping brain. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karimzadeh, Z.; Azizzadeh Forouzi, M.; Rahiminezhad, E.; Ahmadinejad, M.; Dehghan, M. The Effects of Lavender and Citrus aurantium on Anxiety and Agitation of the Conscious Patients in Intensive Care Units: A Parallel Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial. Biomed. Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 5565956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, A.L.; Favero, G.C.; Boaventura, T.P.; de Freitas Souza, C.; Ferreira, N.S.; Descovi, S.N.; Baldisserotto, B.; Heinzmann, B.M.; Luz, R.K. Essential oil of Ocimum gratissimum (Linnaeus, 1753): Efficacy for anesthesia and transport of Oreochromis niloticus. Fish. Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 47, 135–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, Y.; Shindo, S.; Kanbayashi, T.; Takeshima, M.; Imanishi, A.; Mishima, K. Examination of the influence of cedar fragrance on cognitive function and behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia in Alzheimer type dementia. Neuropsychopharmacol. Rep. 2020, 40, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, R. Essential oil inhaler (AromaStick®) improves heat tolerance in the Hot Immersion Test (HIT). Results from two randomized, controlled experiments. J. Therm. Biol. 2020, 87, 102478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hacke, A.C.M.; Miyoshi, E.; Marques, J.A.; Pereira, R.P. Anxiolytic properties of Cymbopogon citratus (DC.) stapf extract, essential oil and its constituents in zebrafish (Danio rerio). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 260, 113036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, E.; Takeda, R.; Ota, A.; Morita, E.; Imai, D.; Suzuki, Y.; Yokoyama, H.; Ueda, S.Y.; Nakahara, H.; Miyamoto, T.; et al. Increase in diastolic blood pressure induced by fragrance inhalation of grapefruit essential oil is positively correlated with muscle sympathetic nerve activity. J. Physiol. Sci. 2020, 70, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.; Asojo, A.O. Ambient Scent as a Positive Distraction in Long-Term Care Units: Theory of Supportive Design. Herd 2020, 13, 158–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, K.; Hatcher, D.; Good, A. A randomised controlled trial of Lavender (Lavandula angustifolia) and Lemon Balm (Melissa officinalis) essential oils for the treatment of agitated behaviour in older people with and without dementia. Complement. Ther. Med. 2019, 42, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, H.K.; So, W.Y.; Kim, M. Effects of Aromatherapy Combined with Music Therapy on Anxiety, Stress, and Fundamental Nursing Skills in Nursing Students: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, A.K.; Geiger, S.; Braun, H.S.; Aschenbach, J.R. Dietary supplementation of menthol-rich bioactive lipid compounds alters circadian eating behaviour of sheep. BMC Vet. Res. 2019, 15, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, K.H.; Kim, H.J.; Oh, B.; Seo, M.; Lee, E.; Ha, J. Evaluation of human electroencephalogram change for sensory effects of fragrance. Ski. Res. Technol. 2019, 25, 526–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felipe, C.F.B.; Albuquerque, A.M.S.; de Pontes, J.L.X.; de Melo JÍ, V.; Rodrigues, T.; de Sousa, A.M.P.; Monteiro, Á.B.; Ribeiro, A.; Lopes, J.P.; de Menezes, I.R.A.; et al. Comparative study of alpha- and beta-pinene effect on PTZ-induced convulsions in mice. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 2019, 33, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, M.; Li, Y.; Tang, P.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, M.; Ni, J.; Xing, M. Effectiveness of Aromatherapy Massage and Inhalation on Symptoms of Depression in Chinese Community-Dwelling Older Adults. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2018, 24, 717–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vital, A.C.P.; Guerrero, A.; Kempinski, E.; Monteschio, J.O.; Sary, C.; Ramos, T.R.; Campo, M.D.M.; Prado, I.N.D. Consumer profile and acceptability of cooked beef steaks with edible and active coating containing oregano and rosemary essential oils. Meat Sci. 2018, 143, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dijk, M.; O’Flaherty, L.A.; Hoedemaker, T.; van Rosmalen, J.; Rode, H. Massage has no observable effect on distress in children with burns: A randomized, observer-blinded trial. Burns 2018, 44, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şentürk, A.; Tekinsoy Kartın, P. The Effect of Lavender Oil Application via Inhalation Pathway on Hemodialysis Patients’ Anxiety Level and Sleep Quality. Holist. Nurs. Pract. 2018, 32, 324–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qadeer, S.; Emad, S.; Perveen, T.; Yousuf, S.; Sheikh, S.; Sarfaraz, Y.; Sadaf, S.; Haider, S. Role of ibuprofen and lavender oil to alter the stress induced psychological disorders: A comparative study. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 31, 1603–1608. [Google Scholar]

- Moss, M.; Smith, E.; Milner, M.; McCready, J. Acute ingestion of rosemary water: Evidence of cognitive and cerebrovascular effects in healthy adults. J. Psychopharmacol. 2018, 32, 1319–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montibeler, J.; Domingos, T.D.S.; Braga, E.M.; Gnatta, J.R.; Kurebayashi, L.F.S.; Kurebayashi, A.K. Effectiveness of aromatherapy massage on the stress of the surgical center nursing team: A pilot study. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 2018, 52, 03348. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, D.; Okello, E.; Chazot, P.; Howes, M.J.; Ohiomokhare, S.; Jackson, P.; Haskell-Ramsay, C.; Khan, J.; Forster, J.; Wightman, E. Volatile terpenes and brain function: Investigation of the cognitive and mood effects of mentha × piperita L. essential oil with in vitro properties relevant to central nervous system function. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalayasiri, R.; Maneesang, W.; Maes, M. A novel approach of substitution therapy with inhalation of essential oil for the reduction of inhalant craving: A double-blinded randomized controlled trial. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 261, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brnawi, W.I.; Hettiarachchy, N.S.; Horax, R.; Kumar-Phillips, G.; Seo, H.S.; Marcy, J. Comparison of Cinnamon Essential Oils from Leaf and Bark with Respect to Antimicrobial Activity and Sensory Acceptability in Strawberry Shake. J. Food Sci. 2018, 83, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosaffa-Jahromi, M.; Tamaddon, A.M.; Afsharypuor, S.; Salehi, A.; Seradj, S.H.; Pasalar, M.; Jafari, P.; Lankarani, K.B. Effectiveness of Anise Oil for Treatment of Mild to Moderate Depression in Patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Randomized Active and Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. J. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 22, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumoto, T.; Kimura, T.; Hayashi, T. Does Japanese Citrus Fruit Yuzu (Citrus junos Sieb. ex Tanaka) Fragrance Have Lavender-Like Therapeutic Effects That Alleviate Premenstrual Emotional Symptoms? A Single-Blind Randomized Crossover Study. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2017, 23, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, K.Y.C.; Huang, Y.; Yao, P.; Wang, H.; Dong, T.T.X.; Zhou, Z.; Tsim, K.W.K. Comparative Study of Different Acorus Species in Potentiating Neuronal Differentiation in Cultured PC12 Cells. Phytother. Res. 2017, 31, 1757–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadag, E.; Samancioglu, S.; Ozden, D.; Bakir, E. Effects of aromatherapy on sleep quality and anxiety of patients. Nurs. Crit. Care 2017, 22, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goepfert, M.; Liebl, P.; Herth, N.; Ciarlo, G.; Buentzel, J.; Huebner, J. Aroma oil therapy in palliative care: A pilot study with physiological parameters in conscious as well as unconscious patients. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 143, 2123–2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forte, C.; Ranucci, D.; Beghelli, D.; Branciari, R.; Acuti, G.; Todini, L.; Cavallucci, C.; Trabalza-Marinucci, M. Dietary integration with oregano (Origanum vulgare L.) essential oil improves growth rate and oxidative status in outdoor-reared, but not indoor-reared, pigs. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2017, 101, e352–e361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.J.; Chou, C.C.; Yang, L.; Tsai, Y.L.; Chang, Y.C.; Liaw, J.J. Effects of Aromatherapy Massage on Pregnant Women’s Stress and Immune Function: A Longitudinal, Prospective, Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2017, 23, 778–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasper, S.; Volz, H.P.; Dienel, A.; Schläfke, S. Efficacy of Silexan in mixed anxiety-depression—A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016, 26, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gastón, M.S.; Cid, M.P.; Vázquez, A.M.; Decarlini, M.F.; Demmel, G.I.; Rossi, L.I.; Aimar, M.L.; Salvatierra, N.A. Sedative effect of central administration of Coriandrum sativum essential oil and its major component linalool in neonatal chicks. Pharm. Biol. 2016, 54, 1954–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyer, J.; Cleary, L.; McNeill, S.; Ragsdale-Lowe, M.; Osland, C. The use of aromasticks to help with sleep problems: A patient experience survey. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2016, 22, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshiyama, K.; Arita, H.; Suzuki, J. The Effect of Aroma Hand Massage Therapy for People with Dementia. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2015, 21, 759–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, E.; Kuchta, K.; Kimura, M.; Rauwald, H.W.; Kamei, T.; Imanishi, J. Effects of Bergamot (Citrus bergamia (Risso) Wright & Arn.) Essential Oil Aromatherapy on Mood States, Parasympathetic Nervous System Activity, and Salivary Cortisol Levels in 41 Healthy Females. Comp. Med. Res. 2015, 22, 43–49. [Google Scholar]

- Kasper, S.; Anghelescu, I.; Dienel, A. Efficacy of orally administered Silexan in patients with anxiety-related restlessness and disturbed sleep—A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015, 25, 1960–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasanein, P.; Riahi, H. Antinociceptive and antihyperglycemic effects of Melissa officinalis essential oil in an experimental model of diabetes. Med. Princ. Pract. 2015, 24, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.J.; Kumar, K.J.; Chen, Y.T.; Tsao, N.W.; Chien, S.C.; Chang, S.T.; Chu, F.H.; Wang, S.Y. Effect of Hinoki and Meniki Essential Oils on Human Autonomic Nervous System Activity and Mood States. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2015, 10, 1305–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikmoradi, A.; Seifi, Z.; Poorolajal, J.; Araghchian, M.; Safiaryan, R.; Oshvandi, K. Effect of inhalation aromatherapy with lavender essential oil on stress and vital signs in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery: A single-blinded randomized clinical trial. Complement. Ther. Med. 2015, 23, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata, K.; Iida, N.; Kanazawa, H.; Fujiwara, M.; Mogi, T.; Mitsushima, T.; Lefor, A.T.; Sugimoto, H. Effect of listening to music and essential oil inhalation on patients undergoing screening CT colonography: A randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Radiol. 2014, 83, 2172–2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, T.; Asakura, H.; Hayashi, T. Effects of olfactory stimulation from the fragrance of the Japanese citrus fruit yuzu (Citrus junos Sieb. ex Tanaka) on mood states and salivary chromogranin A as an endocrinologic stress marker. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2014, 20, 500–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Köteles, F.; Babulka, P. Role of expectations and pleasantness of essential oils in their acute effects. Acta Physiol. Hung. 2014, 101, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasper, S.; Gastpar, M.; Müller, W.E.; Volz, H.P.; Möller, H.J.; Schläfke, S.; Dienel, A. Lavender oil preparation Silexan is effective in generalized anxiety disorder—A randomized, double-blind comparison to placebo and paroxetine. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014, 17, 859–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igarashi, M.; Song, C.; Ikei, H.; Ohira, T.; Miyazaki, Y. Effect of olfactory stimulation by fresh rose flowers on autonomic nervous activity. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2014, 20, 727–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldinger, P.; Höflich, A.S.; Mitterhauser, M.; Hahn, A.; Rami-Mark, C.; Spies, M.; Wadsak, W.; Lanzenberger, R.; Kasper, S. Effects of Silexan on the serotonin-1A receptor and microstructure of the human brain: A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, cross-over study with molecular and structural neuroimaging. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014, 18, pyu063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varney, E.; Buckle, J. Effect of inhaled essential oils on mental exhaustion and moderate burnout: A small pilot study. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2013, 19, 69–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taavoni, S.; Darsareh, F.; Joolaee, S.; Haghani, H. The effect of aromatherapy massage on the psychological symptoms of postmenopausal Iranian women. Complement. Ther. Med. 2013, 21, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seol, G.H.; Lee, Y.H.; Kang, P.; You, J.H.; Park, M.; Min, S.S. Randomized controlled trial for salvia sclarea or lavandula angustifolia: Differential effects on blood pressure in female patients with urinary incontinence undergoing urodynamic examination. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2013, 19, 664–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igarashi, T. Physical and psychologic effects of aromatherapy inhalation on pregnant women: A randomized controlled trial. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2013, 19, 805–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, P.; Han, T.; Peng, W.; Wang, X.R. Antidepressant-like effects of essential oil and asarone, a major essential oil component from the rhizome of Acorus tatarinowii. Pharm. Biol. 2013, 51, 589–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, C.Y.; Moyle, W.; Cooke, M. A randomised controlled trial of the use of aromatherapy and hand massage to reduce disruptive behaviour in people with dementia. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2013, 13, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brito, R.G.; Santos, P.L.; Prado, D.S.; Santana, M.T.; Araújo, A.A.; Bonjardim, L.R.; Santos, M.R.; de Lucca Júnior, W.; Oliveira, A.P.; Quintans-Júnior, L.J. Citronellol reduces orofacial nociceptive behaviour in mice—Evidence of involvement of retrosplenial cortex and periaqueductal grey areas. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2013, 112, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apay, S.E.; Arslan, S.; Akpinar, R.B.; Celebioglu, A. Effect of aromatherapy massage on dysmenorrhea in Turkish students. Pain Manag. Nurs. 2012, 13, 236–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lizarraga-Valderrama, L.R. Effects of essential oils on central nervous system: Focus on mental health. Phytother. Res. 2021, 35, 657–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanida, M.; Niijima, A.; Shen, J.; Nakamura, T.; Nagai, K. Olfactory stimulation with scent of essential oil of grapefruit affects autonomic neurotransmission and blood pressure. Brain Res. 2005, 1058, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Razaghi, N.; Aemmi, S.Z.; Hoseini, A.S.S.; Boskabadi, H.; Mohebbi, T.; Ramezani, M. The effectiveness of familiar olfactory stimulation with lavender scent and glucose on the pain of blood sampling in term neonates: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Complement. Ther. Med. 2020, 49, 102289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zygmunt, A.; Stanczyk, J. Methods of evaluation of autonomic nervous system function. Arch. Med. Sci. 2010, 6, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilly, T.; Drust, B.; Gregson, W. Thermoregulation in elite athletes. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2006, 9, 666–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Bars, D.; Gozariu, M.; Cadden, S.W. Animal models of nociception. Pharmacol. Rev. 2001, 53, 597–652. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sattayakhom, A.; Wichit, S.; Koomhin, P. The Effects of Essential Oils on the Nervous System: A Scoping Review. Molecules 2023, 28, 3771. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28093771

Sattayakhom A, Wichit S, Koomhin P. The Effects of Essential Oils on the Nervous System: A Scoping Review. Molecules. 2023; 28(9):3771. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28093771

Chicago/Turabian StyleSattayakhom, Apsorn, Sineewanlaya Wichit, and Phanit Koomhin. 2023. "The Effects of Essential Oils on the Nervous System: A Scoping Review" Molecules 28, no. 9: 3771. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28093771

APA StyleSattayakhom, A., Wichit, S., & Koomhin, P. (2023). The Effects of Essential Oils on the Nervous System: A Scoping Review. Molecules, 28(9), 3771. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28093771