A g-Type Lysozyme from Deep-Sea Hydrothermal Vent Shrimp Kills Selectively Gram-Negative Bacteria

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. LysG1 Possesses the Conserved Structure Features of g-Type Lysozyme

2.2. Recombinant LysG1 (rLysG1) Kills Selectively Gram-Negative Bacteria in a Regulated Manner

2.3. rLysG1 Binds Target Bacteria via Interaction with LPS and Attenuates LPS-Induced Inflammatory Response

2.4. rLysG1 Kills Bacteria by Disrupting Bacterial Membrane

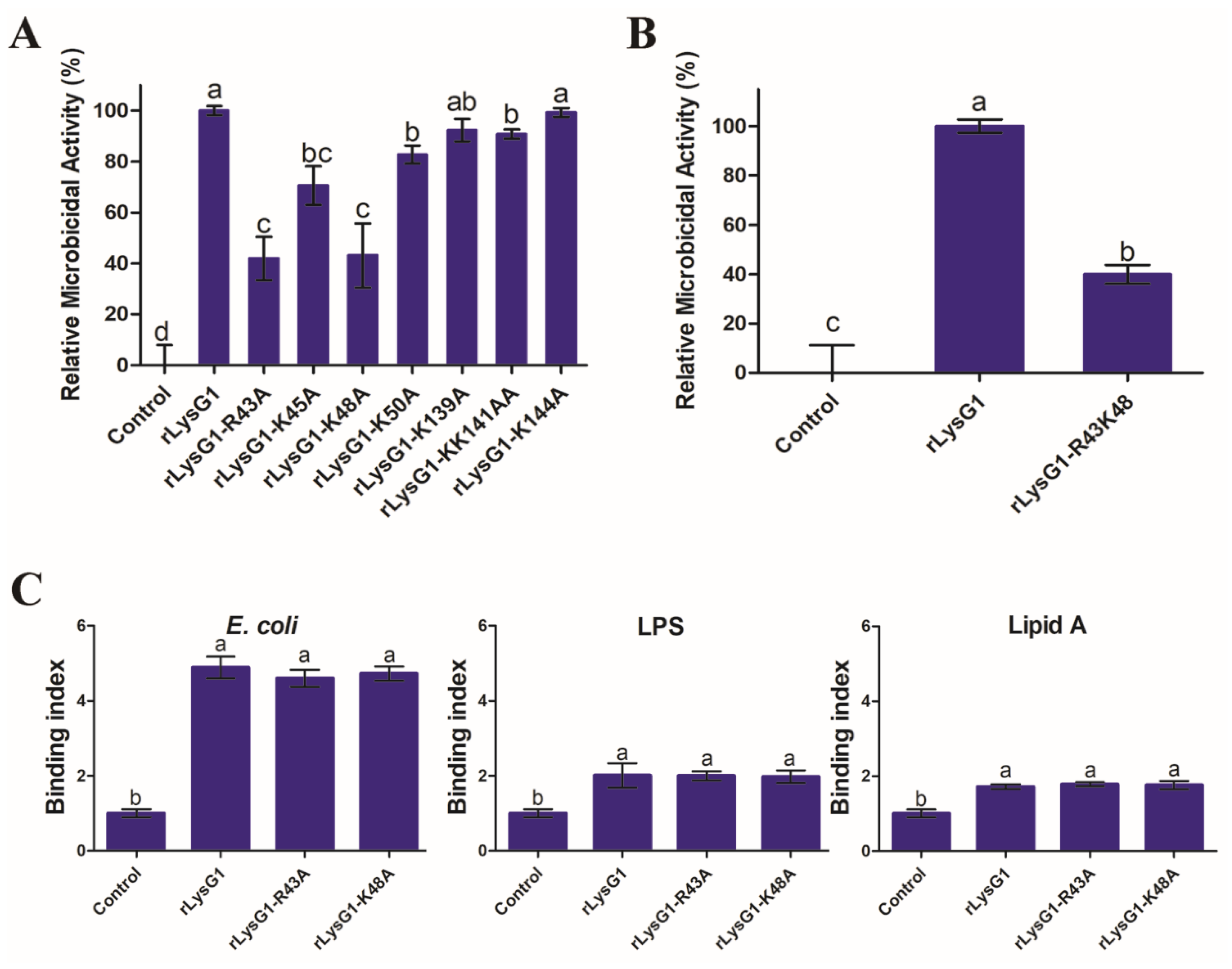

2.5. The Bacteriolytic Activity of rLysG1 Depends on Specific Structural Motifs

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Bacteria Strains and Culture Conditions

4.2. Sequence and Phylogenetic Analysis

4.3. Plasmid Construction and Protein Purification

4.4. Muramidase Activity

4.5. Bactericidal Activity

4.6. Binding of rLysG1 to Bacteria and Bacterial Cell Wall Components

4.7. Examination of Bacterial Cell Membrane Integrity

4.8. Cell Culture

4.9. Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR)

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Sample Availability

References

- Phillips, D.C. The Three-Dimensional Structure of an Enzyme Molecule. Sci. Am. 1966, 215, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De-La-Re-Vega, E.; Garcia-Galaz, A.; Diaz-Cinco, M.E.; Sotelo-Mundo, R.R. White shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) recombinant ly-sozyme has antibacterial activity against Gram negative bacteria: Vibrio alginolyticus, Vibrio parahemolyticus and Vibrio cholerae. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2006, 20, 405–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derde, M.; Lechevalier, V.; Guérin-Dubiard, C.; Cochet, M.-F.; Jan, S.; Baron, F.; Gautier, M.; Vié, V.; Nau, F. Hen Egg White Lysozyme Permeabilizes Escherichia coli Outer and Inner Membranes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 9922–9929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, H.R.; Matsuzaki, T.; Aoki, T. Genetic evidence that antibacterial activity of lysozyme is independent of its catalytic function. FEBS Lett. 2001, 506, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.-W.; Sun, C.; Sun, S.-S.; Zhao, X.-F.; Wang, J.-X. Functional analysis of two invertebrate-type lysozymes from red swamp crayfish, Procambarus clarkii. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2010, 29, 1066–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laible, N.J.; Germaine, G.R. Bactericidal activity of human lysozyme, muramidase-inactive lysozyme, and cationic polypeptides against Streptococcus sanguis and Streptococcus faecalis: Inhibition by chitin oligosaccharides. Infect. Immun. 1985, 48, 720–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Masschalck, B.; Michiels, C.W. Antimicrobial properties of lysozyme in relation to foodborne vegetative bacteria. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2003, 29, 191–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, L.; Douglas, S.D.; Kay, N.E.; Yamada, O.; Osserman, E.F.; Jacob, H.S. Modulation of neutrophil function by lysozyme. Potential negative feedback system of inflammation. J. Clin. Investig. 1979, 64, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ragland, S.A.; Criss, A.K. From bacterial killing to immune modulation: Recent insights into the functions of lysozyme. PLoS Pathog. 2017, 13, e1006512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Kovacs-Nolan, J.; Yang, C.; Archbold, T.; Fan, M.Z.; Mine, Y. Hen Egg Lysozyme Attenuates Inflammation and Modulates Local Gene Expression in a Porcine Model of Dextran Sodium Sulfate (DSS)-Induced Colitis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 2233–2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogundele, M.O. A novel anti-inflammatory activity of lysozyme: Modulation of serum complement activation. Mediat. Inflamm. 1998, 7, 363–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saurabh, S.; Sahoo, P.K. Lysozyme: An important defence molecule of fish innate immune system. Aquac. Res. 2008, 39, 223–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canfield, R.E.; McMurry, S. Purification and characterization of a lysozyme from goose egg white. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1967, 26, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callewaert, L.; Michiels, C.W. Lysozymes in the animal kingdom. J. Biosci. 2010, 35, 127–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, D.M.; Gong, Z.M. Molecular Evolution of Vertebrate Goose-Type Lysozyme Genes. J. Mol. Evol. 2003, 56, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bathige, S.; Umasuthan, N.; Whang, I.; Lim, B.-S.; Jung, H.-B.; Lee, J. Evidences for the involvement of an invertebrate goose-type lysozyme in disk abalone immunity: Cloning, expression analysis and antimicrobial activity. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2013, 35, 1369–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Yu, H.; Liu, W.; Su, H.; Shan, Z.; Bao, X.; Li, Y.; Fu, L.; Gao, X. A goose-type lysozyme gene in Japanese scallop (Mizuhopecten yessoensis): cDNA cloning, mRNA expression and promoter sequence analysis. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2012, 162, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsen, I.W.; Myrnes, B.; Edvardsen, R.B.; Chourrout, D. Urochordates carry multiple genes for goose-type lysozyme and no genes for chicken- or invertebrate-type lysozymes. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2003, 60, 2210–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, J.; You, L.; Wu, H. Two goose-type lysozymes in Mytilus galloprovincialis: Possible function diversifi-cation and adaptive evolution. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e45148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhao, J.; Song, L.; Li, C.; Zou, H.; Ni, D.; Wang, W.; Xu, W. Molecular cloning of an invertebrate goose-type lysozyme gene from Chlamys farreri, and lytic activity of the recombinant protein. Mol. Immunol. 2007, 44, 1198–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, F.; Wu, R.; Yang, S.; Li, Y.; Xu, Y. Identification and functional characterization of a c-type lysozyme from Fenneropenaeus penicillatus. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2019, 88, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hikima, S.; Hikima, J.; Rojtinnakorn, J.; Hirono, I.; Aoki, T. Characterization and function of kuruma shrimp lysozyme pos-sessing lytic activity against Vibrio species. Gene 2003, 316, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.-T.; Wang, J.; Mao, Y.; Liu, M.; Niu, S.-F.; Qiao, Y.; Su, Y.-Q.; Wang, C.-Z.; Zheng, Z.-P. Identification and expression analysis of a new invertebrate lysozyme in Kuruma shrimp (Marsupenaeus japonicus). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2016, 49, 336–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.H.; Li, T.; Cao, X.T.; Zhou, Y.; Yuan, J.F.; Gu, Z.M.; Lan, J.F. PcLys-i3, an invertebrate lysozyme, is involved in the an-tibacterial immunity of the red swamp crayfish, Procambarus clarkii. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2018, 87, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sotelo-Mundo, R.R.; Islas-Osuna, M.A.; De-La-Re-Vega, E.; Hernández-López, J.; Vargas-Albores, F.; Yepiz-Plascencia, G. cDNA cloning of the lysozyme of the white shrimp Penaeus vannamei. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2003, 15, 325–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supungul, P.; Rimphanitchayakit, V.; Aoki, T.; Hirono, I.; Tassanakajon, A. Molecular characterization and expression analysis of a c-type and two novel muramidase-deficient i-type lysozymes from Penaeus monodon. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2010, 28, 490–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Gao, F.Y.; Zheng, Q.M.; Bai, J.J.; Wang, H.; Lao, H.H.; Jian, Q. Cloning and characterization of the tiger shrimp lysozyme. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2009, 36, 1239–1246. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Sun, Q.-L.; Luan, Z.-D.; Lian, C.; Sun, L. Comparative transcriptome analysis of Rimicaris sp. reveals novel molecular features associated with survival in deep-sea hydrothermal vent. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Little, C.; Vrijenhoek, R.C. Are hydrothermal vent animals living fossils? Trends Ecol. Evol. 2003, 18, 582–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dover, C.L.; German, C.R.; Speer, K.G.; Parson, L.M.; Vrijenhoek, R.C. Evolution and biogeography of deep-sea vent and seep invertebrates. Science 2002, 295, 1253–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martin, J.W.; Haney, T.A. Decapod crustaceans from hydrothermal vents and cold seeps: A review through 2005. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 2005, 145, 445–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Ávila, I.; Cambon-Bonavita, M.-A.; Pradillon, F. Morphology of First Zoeal Stage of Four Genera of Alvinocaridid Shrimps from Hydrothermal Vents and Cold Seeps: Implications for Ecology, Larval Biology and Phylogeny. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0144657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.L.; Ye, S.; Cheng, C.Y.; Li, H.W.; Lu, B.; Yang, W.J.; Yang, J.S. Identification and characterization of a symbiotic agglutina-tion-related C-type lectin from the hydrothermal vent shrimp Rimicaris exoculata. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2019, 92, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Sun, Y.; Sun, L. A Crustin from Hydrothermal Vent Shrimp: Antimicrobial Activity and Mechanism. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Bloa, S.; Boidin-Wichlacz, C.; Cueff-Gauchard, V.; Rosa, R.D.; Cuvillier-Hot, V.; Durand, L.; Methou, P.; Pradillon, F.; Cam-bon-Bonavita, M.A.; Tasiemski, A. Antimicrobial peptides and ectosymbiotic relationships: Involvement of a novel type iia crustin in the life Cycle of a deep-sea vent shrimp. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, A.N.; Solstad, T.; Svineng, G.; Seppola, M.; Jørgensen, T.Ø. Molecular characterisation of a goose-type lysozyme gene in Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua L.). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2009, 26, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Herreweghe, J.M.; Michiels, C.W. Invertebrate lysozymes: Diversity and distribution, molecular mechanism and in vivo function. J. Biosci. 2012, 37, 327–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buonocore, F.; Randelli, E.; Trisolino, P.; Facchiano, A.; de Pascale, D.; Scapigliati, G. Molecular characterization, gene structure and antibacterial activity of a g-type lysozyme from the European sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax L.). Mol. Immunol. 2014, 62, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilojan, J.; Bathige, S.; Kugapreethan, R.; Thulasitha, W.; Nam, B.-H.; Lee, J. Molecular, transcriptional and functional insights into duplicated goose-type lysozymes from Sebastes schlegelii and their potential immunological role. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2017, 67, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Liu, R.; Cui, D.; Liu, H.; Xiong, D.; Liu, X.; Wang, L. Analysis on the expression and function of a chicken-type and goose-type lysozymes in Chinese giant salamanders Andrias davidianus. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2017, 72, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; He, J.; Deng, W.; Chan, S. Molecular cloning, expression of orange-spotted grouper goose-type lysozyme cDNA, and lytic activity of its recombinant protein. Dis. Aquat. Org. 2003, 55, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, S.H.; Zhu, D.D.; Chang, M.X.; Zhao, Q.P.; Jiao, R.; Huang, B.; Fu, J.P.; Liu, Z.X.; Nie, P. Three goose-type lysozymes in the gastropod Oncomelania hupensis: cDNA sequences and lytic activity of recombinant proteins. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2012, 36, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Düring, K.; Porsch, P.; Mahn, A.; Brinkmann, O.; Gieffers, W. The non-enzymatic microbicidal activity of lysozymes. FEBS Lett. 1999, 449, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorini, L.; Felix, F. Influence of manganese on the stability of lysozyme. I. Influence of manganese on the rate of irreversible inactivation of lysozyme by heat. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1953, 10, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuroki, R.; Taniyama, Y.; Seko, C.; Nakamura, H.; Kikuchi, M.; Ikehara, M. Design and creation of a Ca2+ binding site in human lysozyme to enhance structural stability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1989, 86, 6903–6907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bonincontro, A.; De Francesco, A.; Onori, G. Influence of pH on lysozyme conformation revealed by dielectric spectroscopy. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 1998, 12, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, A.; Thomas, U.; Wild, P.; Schraner, E.; Von Fellenberg, R. Effect of lysozyme or modified lysozyme fragments on DNA and RNA synthesis and membrane permeability of Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Res. 2000, 155, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thammasirirak, S.; Pukcothanung, Y.; Preecharram, S.; Daduang, S.; Patramanon, R.; Fukamizo, T.; Araki, T. Antimicrobial peptides derived from goose egg white lysozyme. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2010, 151, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wild, P.; Gabrieli, A.; Schraner, E.M.; Pellegrini, A.; Thomas, U.; Frederik, P.M.; Stuart, M.C.; Von Fellenberg, R. Reevaluation of the effect of lysoyzme on Escherichia coli employing ultrarapid freezing followed by cryoelectronmicroscopy or freeze substitu-tion. Microsc. Res. Tech. 1997, 39, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganz, T.; Gabayan, V.; Liao, H.-I.; Liu, L.; Oren, A.; Graf, T.; Cole, A.M. Increased inflammation in lysozyme M–deficient mice in response to Micrococcus luteus and its peptidoglycan. Blood 2003, 101, 2388–2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riber, U.; Espersen, F.; Wilkinson, B.J.; Kharazmi, A. Neutrophil chemotactic activity of peptidoglycan. A comparison between Staphylococcus-Aureus and Staphylococcus-Epidermidis. APMIS 1990, 98, 881–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, S.; Gu, H.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, L. Teleost Gasdermin E Is Cleaved by Caspase 1, 3, and 7 and Induces Pyroptosis. J. Immunol. 2019, 203, 1369–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, B.; Ding, Y.; Xie, L.; Yan, L. The Modification of the DNS Method for the Determination of Reducing Sugar. J. WuXi Univ. Light Ind. 1999, 18, 74–79. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.; Jiang, S.; Sun, L. A Fish Galectin-8 Possesses Direct Bactericidal Activity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 22, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Microorganisms | MBC (µM) |

|---|---|

| Gram-negative bacteria | |

| Pseudomonas fluorescens | 8 |

| Escherichia coli | 4 |

| Edwardsiella tarda | 16 |

| Vibrio harveyi | - |

| Vibrio anguillarum | - |

| Gram-positive bacteria | |

| Staphylococcus aureus | - |

| Streptococcus iniae | - |

| Micrococcus luteus | - |

| Bacillus subtilis | - |

| Gram-negative bacteria (Deep-sea) | |

| Psedoalteromonas hodoensis | 4 |

| Vibrio neocaledonicus | - |

| Alteromonas abrolhosensis | - |

| Pseudidiomarina donghaiensis | - |

| Gram-positive bacteria (Deep-sea) | |

| Bacillus thuringiensis | - |

| Bacillus mobilis | - |

| Bacillus toyonensis | - |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Luo, J.-C.; Zhang, J.; Sun, L. A g-Type Lysozyme from Deep-Sea Hydrothermal Vent Shrimp Kills Selectively Gram-Negative Bacteria. Molecules 2021, 26, 7624. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26247624

Luo J-C, Zhang J, Sun L. A g-Type Lysozyme from Deep-Sea Hydrothermal Vent Shrimp Kills Selectively Gram-Negative Bacteria. Molecules. 2021; 26(24):7624. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26247624

Chicago/Turabian StyleLuo, Jing-Chang, Jian Zhang, and Li Sun. 2021. "A g-Type Lysozyme from Deep-Sea Hydrothermal Vent Shrimp Kills Selectively Gram-Negative Bacteria" Molecules 26, no. 24: 7624. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26247624

APA StyleLuo, J.-C., Zhang, J., & Sun, L. (2021). A g-Type Lysozyme from Deep-Sea Hydrothermal Vent Shrimp Kills Selectively Gram-Negative Bacteria. Molecules, 26(24), 7624. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26247624