Ca’ Granda, Hortus simplicium: Restoring an Ancient Medicinal Garden of XV–XIX Century in Milan (Italy)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

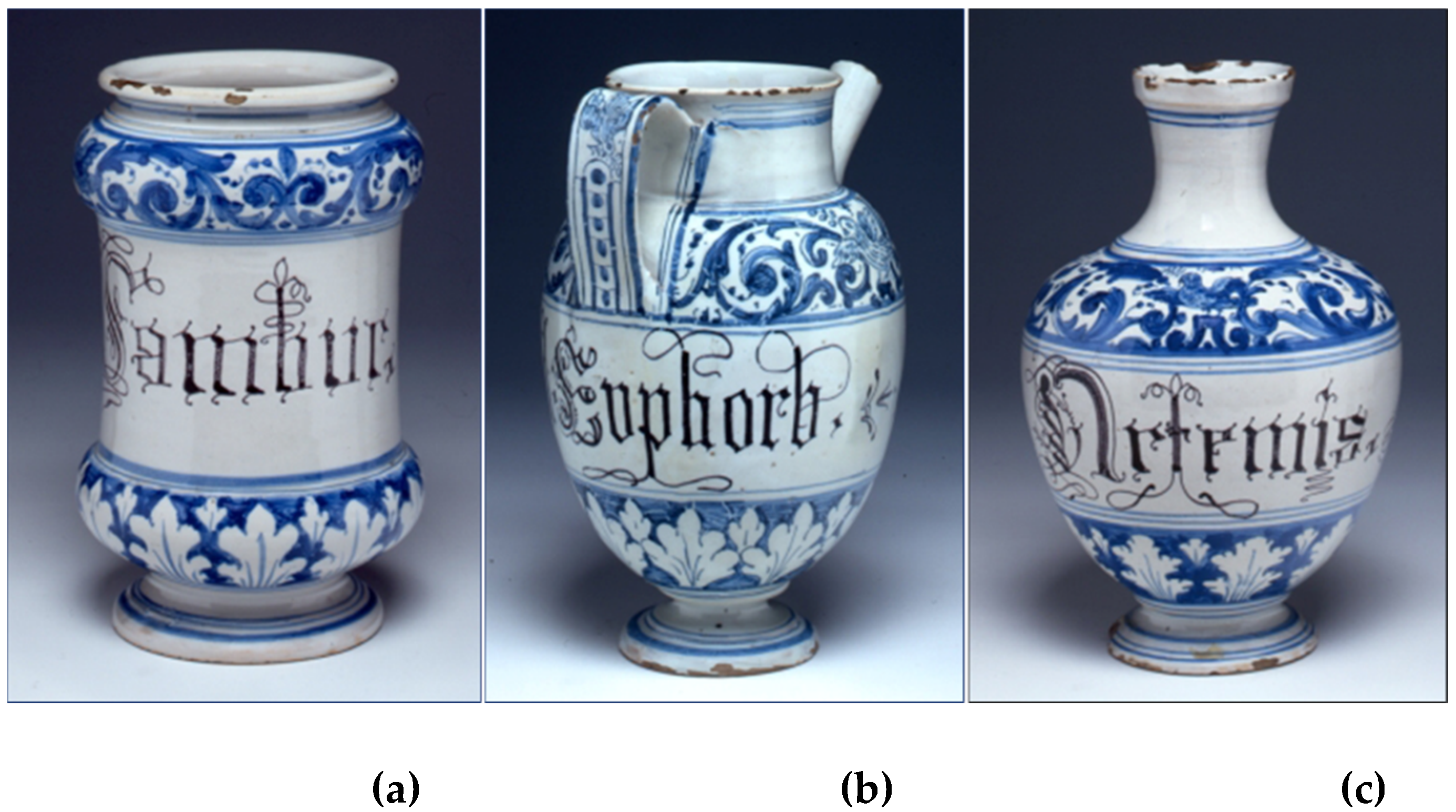

2.1. Inscriptions Analysis and Interpretation

2.2. Plant Species in the Remedies and Validation of the Historical Medicinal Use

2.3. Plant Species Checklist for the Restoration of the Ancient Garden of Simples

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Historical Research

3.2. Pharmacological Research

3.3. Checklist of Potentially Cultivated Species at the Ancient Garden of Simples

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cosmacini, G. La Ca’ Granda dei Milanesi: Storia dell’Ospedale Maggiore di Milano; Laterza: Roma/Bari, Italy, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Castelli, G. La Farmacia dell’Ospedale Maggiore nei Secoli; Edizioni Medici Domus: Milano, Italy, 1940. [Google Scholar]

- Sironi, V.A. Ospedali e Medicamenti: Storia del Farmacista Ospedaliero; Laterza: Roma/Bari, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bosi, G.; Mazzanti, M.B.; Galimberti, P.M.; Mills, J.; Montecchi, M.C.; Rottoli, M.; Torri, P.; Reggio, M. Indagini archeologiche sull’antico giardino dei semplici della Spezieria dell’Ospedale Maggiore di Milano. Archeol. Uomo Territ. 2012, 31, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Bascapè, G. La “Spezieria” dell’Ospedale Maggiore (sec. XV–XIX). Antichi Ricettari Farmaceutici. La suppellettile artistica: Vasi del Rinascimento e dell’età Barocca, mortai ecc. Le Scuole di Chimica e Farmacia (1783–1860); “Quaderni di Poesia” di Emo Cavalleri: Milano/Como, Italy, 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Zanchi, G. La collezione dei vasi da farmacia. In Ospedale Maggiore/Ca’ Granda. Collezioni Diverse; Electa: Milano, Italy, 1988; pp. 273–316. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://www.lombardiabeniculturali.it (accessed on 30 September 2021).

- Donzelli, G.; Donzelli, T. Teatro Farmaceutico, Dogmatico e Spagirico; Napoli, Italy, 1726; Available online: https://books.google.com.hk/books?hl=zh-CN&lr=&id=dVBgAAAAcAAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP11&dq=Donzelli,+G.%3B+Donzelli,+T.+Teatro+Farmaceutico,+Dogmatico+e+Spagirico&ots=syW7IdzlLr&sig=Zbvu93VZtRFCQ59mJCJe3dsUI7g&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=Donzelli%2C%20G.%3B%20Donzelli%2C%20T.%20Teatro%20Farmaceutico%2C%20Dogmatico%20e%20Spagirico&f=false (accessed on 30 September 2021).

- Lémery, N. Farmacopea Universale che Contiene Tutte le Composizioni di Farmacia le quali sono in uso Nella Medicina, tanto in Francia, Quanto per Tutta L’europa, … e di più un Vocabolario Farmaceutico, Molte Nuove Osservazioni, ed Alcuni Ragionamenti Sopra Ogni op; Gio. Gabriel Hertz: Venezia, Italy, 1720. [Google Scholar]

- Castiglione, G.O. Prospectus Pharmaceutici; Mediolani: Caroli Iosephi Quinti: Milano, Italy, 1698. [Google Scholar]

- Castiglione, G.O.; Castiglione, B.F.; Galli, C.G. Prospectus Pharmaceutici Editio Tertia, […]; Caroli Iosephi Quinti: Milano, Italy, 1729. [Google Scholar]

- Collegio dei Medici (Roma); Castelli, P.; Ceccarelli, I. Antidotario romano latino, e volgare. Tradotto da Ippolito Ceccarelli. Li Ragionamenti, e le Aggiunte Dell’elettione de’ Semplici, e Prattica delle Compositioni. Con le Annotationi del sig. Pietro Castelli Romano. E Trattati Della Teriaca Romana, e Della; In Venetia per Francesco Brogiollo: Venezia, Italy, 1664. [Google Scholar]

- James, R. Dizionario Universale di Medicina di Chirurgia di Chimica di Botanica di Notomia di Farmacia D’istoria Naturale & c. Del Signor James a cui Precede un Discorso Istorico Intorno All’origine e Progressi Della Medicina Tradotto Dall’originale Inglese dai sig; Giambatista Pasquali: Venezia, Italy, 1753. [Google Scholar]

- Ettmüller, M. Michaelis Ettmulleri … Opera Omnia in Quinque tomos Distribuita. Editio Novissima Veneta, Lugdunensi, Francofurtensi et Neapolitana Emendatior, & Locupletior Omnium Completissima cum Integro Textu Schroederi, Morelli, et ludovici; Jo. Gabrielis Hertz: Venezia, Italy, 1734. [Google Scholar]

- Royal College of Physicians of London. Pharmacopœia Londinensis: Or, the New London Dispensatory … Translated into English … The Seventh Edition, Corrected and Amended. By William Salmon. [With a portrait.]; R. Chiswell: London, UK, 1707. [Google Scholar]

- Medicum Collegium Boudewyns. Pharmacia Antuerpiensis Galeno-Chymica. A Medicis Iuratis,&Collegij Medici officialibus … Edita, etc. [With a Preface by M. Boudewyns.]; Georgium Willemseus: Antwerp, Belgium, 1661. [Google Scholar]

- Donzelli, G. Teatro Farmaceutico Dogmatico e Spagirico del Dottore Giuseppe Donzelli …: Nel Quale S’insegna una Moltiplicità D’arcani Chimici più Sperimentati Dall’autore in Ordine alla Sanità, con Evento non Fallace e con una Canonica Norma di Preparare Ogni Compos; Antonio Bortoli: Venezia, Italy, 1704. [Google Scholar]

- Barnaba, G.P.O. Opera di Gio. Pietro Orelli Barnaba di Locarno,… Nella Quale si Tratta de’ Morbi al Corpo Umano Dannosi, con loro Cause, Segni, e Pronostici, con le cure de’ Medemi, e con L’aggiunta de’ Composti Chimici, ed Altri Particolari Segreti; Carlo Giuseppe Quinto: Milano, Italy, 1711. [Google Scholar]

- Culpeper, N. The Complete Herbal; to Which Is Now Added, Upwards of One Hundred Additional Herbs, with a Display of Their Medicinal and Occult Qualities … to Which Are Now First Annexed, The English Physician, Enlarged, and Key to Physic … New Edition … Illustra; Thomas Kelly&Company: London, UK, 1863. [Google Scholar]

- Rossetto, G. I Libri di Gio. Mesue dei Semplici Purgatiui, et Delle Medicine Composte, Adornati di Molti Annotationi, & Dichiarationi Vtilissimi, a li Gioueni, che Vogliono Essercitar L’arte Della Speciaria Come Tesoro di Quella, con Vn’ampia Espositione di Vocabuli; Alessandro de’ Vecchi: Venezia, Italy, 1621. [Google Scholar]

- Lémery, N. Dizionario overo Trattato Universale delle Droghe Semplici in cui si Ritrovano i loro Differenti nomi, la loro Origine, la loro Scelta, i Principj, che Hanno, le loro Qualità, la loro Etimologia, e Tutto ciò, che v’ha di Particolare Negli Animali, ne’ veg; Giuseppe Bertella: Venezia, Italy, 1751. [Google Scholar]

- Scoresby-Jackson, R.E. Notebook of Materia Medica, Pharmacology, and Therapeutics; Maclachlan & Stewart: Edinburgh, UK, 1875. [Google Scholar]

- Aldovrandi, U. Antidotarium, à Bonon: Med: Collegio Ampliatum … Cum dupl. Tab., una Præsidiorum, Altera Morborum; Vittorio Benacci: Bologna, Italy, 1606. [Google Scholar]

- Mattioli, P.A. I Discorsi di M. Pietro And. Matthioli Sanese, Medico del Sereniss. Principe Ferdinando Archiduca d’Austria & c. ne i sei libri di Pedacio Dioscoride Anazarbeo Della Materia Medicinale. I Quai Discorsi in Diuersi Luoghi Dall’auttore Medesimo sono Stati ac; Vincenzo Valgrisi: Venezia, Italy, 1559. [Google Scholar]

- Aldrovandi, U. ANTIDOTARII BONONIENSIS, siue De Vsitata Ratione Componendorum, Miscendorumq[ue] Medicamontorum, EPITOME; Giovanni Rossi: Bologna, Italy, 1574. [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann, P.K. Farmacologia Dinamica per uso Accademico del Dottore in Medicina, … Fil. car. Hartmann Tradotta dal Latino in Italiano Dalli Fratelli Andrea ed Angelo Buffini con Aggiunte Enunciate Nella loro Prefazione. Dedicata al Chiarissimo Dottore … Giuseppe Cor; Tipografia Bizzoni: Pavia, Italy, 1827. [Google Scholar]

- Donzelli, G. Teatro Farmaceutico Dogmatico, e Spagirico del Dottore Giuseppe Donzelli Napoletano, … nel Quale S’insegna vna Moltiplicità D’arcani Chimici più Sperimentati Dall’autore, … Con L’aggiunta in Molti Luoghi del Dottor Tomaso Donzelli Figlio Dell’autore; Felice Cesaretti: Roma, Italy, 1677. [Google Scholar]

- Tiling, M. Matthiae Tilingi… Lilium Curiosum, seu Accurata Lilii albi Descriptio, in qua ejus Natura & Essentia Mirabilis… Explicantur…; Francofurti ad Moenum: Sumptibus Jacobi Gothofredi Seyleri: Typis Balthas. Christoph. Wustii, sen: Frankfurt, Germany, 1683. [Google Scholar]

- Maynwaringe, E. Historia et Mysterium luis Venereæ: Utrumque Concise Abstractum et Formatum ex Feriis Perpensionibus & Criticis Collationibus Diversarum Repugnantium Opinionum… Medicorum Anglorum, Gallorum, Hispanorum & Italorum, Dissentientium Scriptorum (…); Nauman & Wolff: Frankfurt, Germany, 1675. [Google Scholar]

- Borgarucci, P. La Fabrica Degli Spetiali Partita in XII Distintioni; Vincenzo Valgrisio: Venezia, Italy, 1566. [Google Scholar]

- Geiger, P.L. Pharmacopoea Universalis; Chr. Fr. Winter: Heidelberg, Germany, 1845. [Google Scholar]

- Memoirs of the Royal Society, or a New Abridgment of the Philosophical Transactions from 1665 to 1740; J. Nourse: London, UK, 1745.

- Dresdnisches Magazin oder Ausarbeitungen und Nachrichten zum Behuf der Naturlehre, der Arzneykunst, etc.; Gröll M.: Dresden, Germany, 1760.

- Elzevier, K. Lexicon Galeno-Chymico-Pharmaceuticum Universale, of Groot-Algemeen Apothekers Woordenboek, Vervattende de Voorschriften der Samengestelde Geneesmiddelen, Die in Alle Bekende Dispensatorien Worden Gevonden …; Amsterdam: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1790. [Google Scholar]

- Manget, J.J. Bibliotheca Medico-Practica …; H. Cramer & Fratrum Philibert: Geneva, Switzerland, 1739. [Google Scholar]

- Culpeper, N. Pharmacopœia Londinensis; or, the London Dispensatory, Further Adorned by the Studies and Collections of the Fellows Now Living of the Said College, etc.; Awnsham and John Churchill: London, UK, 1695. [Google Scholar]

- Blanckaert, S. The Physical Dictionary … The Fifth Edition: With the Addition of Many Thousand Terms of Art … Also a Catalogue of Characters Used in Physick, Both in Latin and English, Engraved in Copper; Sam Crouch; John Sprint: London, UK, 1708. [Google Scholar]

- von Plenck, J.J. Materia Chirurgica, Ovvero Dottrina de’ Medicamenti Soliti Usarsi alla cura de’ Mali Esterni, del Celebre Profess. G.J. Plenck, Dottore di Chirurgia … Nella Cesareo Regia Universita di Buda; Giuseppe Orlandelli: Venezia, Italy, 1788. [Google Scholar]

- Millar, J. Encyclopaedia Britannica, or a Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and Miscellaneous Literature; A. Constable and Company: Edimburgh, UK, 1810. [Google Scholar]

- Cooley, A.J.; Brough, J.C. Cooley’s Cyclopaedia of Practical Receipts, Processes: And Collateral Information in the Arts, Manufactures, Professions, and Trades, Including Medicine, Pharmacy, and Domestic Economy. Designed as a Comprehensive Supplement to the Pharmacopoeias …; John Churchill and Son: London, UK, 1864. [Google Scholar]

- Graniti, N. Dell’antica, e Moderna Medicina Teorica, e Pratica Meccanicamente Illustrata da Niccolo Graniti patrizio Salernitano Dottor Fisico-Medico-Teologo, Accademico Genial di SICILIA, Della Societa Letteraria di Venezia, Nominato fra gli Arcadi di Roma Filoteo A; Domenico Occhi: Venezia, Italy, 1739. [Google Scholar]

- de Gorter, J. Joannis de Gorter … Chirurgia Repurgata ab Auctore Recensita, Emendata, Multisque in Locis Aucta. Accessit Materies Medica Chirurgiae Repurgatae Accommodata; Giovanni Manfrè: Padova, Italy, 1765. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, J. The Elements of Materia Medica; Longman, Orme, Brown, Green, and Longmans: London, UK, 1840. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, G.B.; Bache, F.; Wood, H.C.; Remington, J.P.; Sadtler, S.P.; LaWall, C.H.; Osol, A. The Dispensatory of the United States of America; J. B. Lippincott Company: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1883. [Google Scholar]

- Blanckaert, S. The Physical Dictionary … The Sixth Edition: With the Addition of Many Thousand Terms of Art, and Their Explanation … Also a Catalogue of the Characters Us’d in Physick, etc.; Sam. Crouch; John&Benj. Sprint: London, UK, 1715. [Google Scholar]

- Beasley, H. The Medical Formulary: Comprising Standard and Approved Formulae for the Preparations and Compounds Employed in Medical Practice; Lindsay & Blakiston: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1856. [Google Scholar]

- Horst, G. Opera Medica: 3; Johan Andreas and Wolfgang Jun. Haredum: Nuremberg, Germany, 1660. [Google Scholar]

- Collegium Medicum Amstelodamensis (Amsterdam). Pharmacopoea Amstelodamensis nova; Petrum Henricum Dronsberg: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1792. [Google Scholar]

- Dispensatorium Pharmaceuticum Austriaco-Viennense; Collegium Pharmaceuticum Viennense: Wien, Austria, 1751.

- Dubois, J.; Galenus, C. Mesue et Omnia quae cum eo Imprimi Consueuerunt Pulchrioribus Typis Reformata … Addita est Iacobi Siluij Interpretatio Canonum Uniuersalium … Et duo Trochisci Mesue, Quæin Manu Scriptis Exemplaribus Inuenimus: & Quædam Compositiones ex Galeno; Lucantonio Giunti: Venezia, Italy, 1549. [Google Scholar]

- Medicorum, C. Antidotarium Bononiense Medic. Collegii Diligenter Emendatum et Auctum …; Vittorio Benacci: Bologna, Italy, 1615. [Google Scholar]

- The Epitome: A Monthly Retrospect of American Practical Medicine and Surgery; W. A. Townsend: New York, NY, USA, 1886.

- Garrod, A.B. The Essentials of Materia Medica, and Therapeutics; W. Wood & Company: New York, NY, USA, 1865. [Google Scholar]

- Jourdan, A.J.L.; Sembenini, G.B. Farmacopea Universale Ossia Prospetto Delle Farmacopee Di Amsterdam, Anversa, Dublino, Edimburgo (etc.); Geronimo Tasso: Venezia, Italy, 1833. [Google Scholar]

- Blanckaert, S. The Physical Dictionary, Wherein the Terms of Anatomy, the Names and Causes of Diseases, Chirurgical Instruments, and Their Use, Are Accurately Described … the Seventh Edition, Etc.; John&Benj. Sprint; Edw. Symon: London, UK, 1726. [Google Scholar]

- Zucchi, C.; Ranzoli, A. Prontuario di Farmacia Coll’aggiunta di Nozioni di Chimica Legale e di Chimica Medica; Francesco Vallardi: Milano, Italy, 1855. [Google Scholar]

- Beasley, H. The Book of Prescriptions: Containing 2900 Prescriptions Collected from the Practice of the Most Eminent Physicians and Surgeons, English and Foreign; Lindsay & Blakiston: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1855. [Google Scholar]

- Castelli, P. Antidotario Romano Commentato dal Dottor Pietro Castelli … Oue S’apporta il Primo Autore di Ciascheduna Compositione, si fa la Collatione con L’altre Ricette, etc. With the Text; G. B. Russo: Cosenza, Italy, 1648. [Google Scholar]

- Vossius, G.J. Gerardi Ioannis Vosii de Theologia Gentili, et Physiologia Christiana …; Joan Blaeu: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1668. [Google Scholar]

- Durante, C.; Ferro, G.M. Herbario Nuovo; Giacomo Hertz: Venezia, Italy, 1667. [Google Scholar]

- Fantonetti, G. Dizionario dei Termini di Medicina, Chirurgia, Veterinaria, Farmacia, Storia Naturale, Botanica, Fisica, Chimica, ec. di Begin, Boisseau, Jourdain, Montgarny, Richard, Dottori in Medicina, Sanson, Dottore in Chirurgia Dupuy, Professore alla Scuola Veterina; Editori degli Annali Universali delle Scienze e dell’Industria coi tipi di F. e P. Lampato: Milano, Italy, 1828. [Google Scholar]

- Cantani, A. Manuale di Farmacologia Clinica (Materia Medica e Terapeutica) Basata Specialmente sui Recenti Progressi Della Fisiologia e Della Clinica: 2; Editori degli Annali Universali delle Scienze e dell’Industria coi tipi di F. e P. Lampato: Milano, Italy, 1887. [Google Scholar]

- Direzione Generale della Sanità Pubblica. Farmacopea Ufficiale del Regno D’italia; Tip. Delle Mantellate: Roma, Italy, 1892. [Google Scholar]

- Gherardini, G. Supplimento a’ Vocabolarj Italiani Proposto da Giovanni Gherardini: L-P. 4; Stamperia di Gius. Bernardoni di Gio: Milano, Italy, 1855. [Google Scholar]

- Cassone, F. Flora Medico-Farmaceutica; Tip. di G. Cassone: Torino, Italy, 1850. [Google Scholar]

- Casselmann, A. Commentar zur russischen Pharmacopoe, nebst Uebersetzung des Textes, und vergleichender Berücksichtigung der neuesten Pharmacopoeen des Auslandes. … Bearbeitet von Dr A. Casselmann. Heft 1; St. Pietroburgo, Russia, 1867; Available online: https://play.google.com/store/books/details/Commentar_zur_russischen_Pharmacopoe_nebst_Ueberse?id=GfBZAAAAcAAJ&hl=bg&gl=US (accessed on 30 September 2021).

- Capria, D.M. Dizionario Generale di Chimica, Farmacia, Terapia, Materia-Medica, Tossicologia, Mineralogia e Chimica Applicata alle Arti; Andrea Festa: Napoli, Italy, 1860. [Google Scholar]

- Richter, G.A. Trattato Completo Di Materia Medica. Prima Versione Italiana Del Dottore Domenico Gola; Angelo Bonfanti: Milano, Italy, 1834. [Google Scholar]

- Orosi, G. Farmacopea italiana: Pt. 1; Vincenzo Mansi Editore: Livorno, Italy, 1857. [Google Scholar]

- Biblioteca Provinciale. Dizionario Delle Scienze Naturali nel quale si Tratta Metodicamente dei Differenti Esseri Della Natura, … Accompagnato da una Biografia de’ piu Celebri Naturalisti, Opera utile ai Medici, agli Agricoltori, ai Mercanti, agli artisti, ai Manifattori, …; V. Batelli e Comp.: Firenze, Italy, 1848. [Google Scholar]

- Mistichelli, D.; Vincent, H.; Trevisani, F.; De Rossi, A. Trattato Dell’apoplessia in cui con Nuove Osservazioni Anatomiche, e Riflessioni Fisiche si Ricercano Tutte le Cagioni, e Spezie di quel male, e vi si Palesa frà gli altri un Nuovo, & Efficace Rimedio. Dedicato al Reverendiss. Padre, e Padrone Colendiss; Antonio de’ Rossi: Roma, Italy, 1709. [Google Scholar]

- Chomel, P.G.B. Storia Compendiosa Delle Piante Usuali che Comprende i Diversi Nomi Delle Medesime, la loro Dose, le Principali loro Composizioni in Farmacia, e il Modo di Servirsene di Pier. Gio. Bat. Chomel Tradotta dal Francese … Tomo Primo-Quinto; Desideri: Roma, Italy, 1809. [Google Scholar]

- Soares, F. Pharmacopéa Lusitana Composta pela Commissão Creada por Decreto da Rainha Fidelissima D. Maria II. em 5 de Outubra de 1838. [By F. Soares Franco.]; José Baptista Morando: Lisbon, Portugal, 1841. [Google Scholar]

- Hager, H. Pharmacopoea recentiores Anglica, Gallica, Germaniae, Helvetica, Russiae inter se Collatae: Supplementum Manualis Pharmaceutici Hageri; Güntheri: Wrocław, Poland, 1869. [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger, R. Compendium der Arzneimittellehre nach der Neuesten Österreichischen Pharmakopoe vom Jahre 1855: Nebst Wortgetreuer Uebersetzung Dieser Pharmakopoe und der neuen Arzneitaxe; Carl Gerold: Wien, Austria, 1855. [Google Scholar]

- Càssola, F. Dizionario di Farmacia Generale per Filippo Cassola; Reale Tip. Militare: Napoli, Italy, 1846. [Google Scholar]

- Scotti, G. Flora Medica della Provincia di Como; C. Franchi: Como, Italy, 1872. [Google Scholar]

- Fedelissimi, G.B. De Febre Maligna Polydaedalae Medicorum Epistolae ad Ioannem Baptistam Fidelissimum …; Pietro Antonio Fortunato: Pistoia, Italy, 1628. [Google Scholar]

- Miraj, S.; Alesaeidi, S. A systematic review study of therapeutic effects of Matricaria recutita chamomile (chamomile). Electron. Physician 2016, 8, 3024–3031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usta, C.; Yildirim, A.B.; Turker, A.U. Antibacterial and antitumour activities of some plants grown in Turkey. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2014, 28, 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, N.E.; Kaddam, L.A.; Alkarib, S.Y.; Kaballo, B.G.; Khalid, S.A.; Higawee, A.; Abdelhabib, A.; Alaaaldeen, A.; Phillips, A.O.; Saeed, A.M. Gum Arabic (Acacia senegal) Augmented Total Antioxidant Capacity and Reduced C-Reactive Protein among Haemodialysis Patients in Phase II Trial. Int. J. Nephrol. 2020, 2020, 7214673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saeidnia, S.; Gohari, A.R.; Mokhber-Dezfuli, N.; Kiuchi, F. A review on phytochemistry and medicinal properties of the genus Achillea. DARU J. Pharm. Sci. 2011, 19, 173–186. [Google Scholar]

- Forouzanfar, F.; Hosseinzadeh, H. Medicinal herbs in the treatment of neuropathic pain: A review. Iran. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2018, 21, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghelani, H.; Chapala, M.; Jadav, P. Diuretic and antiurolithiatic activities of an ethanolic extract of Acorus calamus L. rhizome in experimental animal models. J. Tradit. Complement. Med. 2016, 6, 431–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, P.K.; Kumar, V.; Mal, M.; Houghton, P.J. Acorus calamus: Scientific validation of ayurvedic tradition from natural resources. Pharm. Biol. 2007, 45, 651–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajput, S.B.; Tonge, M.B.; Karuppayil, S.M. An overview on traditional uses and pharmacological profile of Acorus calamus Linn. (Sweet flag) and other Acorus species. Phytomedicine 2014, 21, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Snafi, A.E. The chemical constituents and pharmacological effects of Adiantum capillus-veneris—A Review. Int. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2015, 5, 106–111. [Google Scholar]

- Dehdari, S.; Hajimehdipoor, H. Medicinal properties of Adiantum capillus-veneris Linn. In traditional medicine and modern phytotherapy: A review article. Iran. J. Public Health 2018, 47, 188–197. [Google Scholar]

- Ibraheim, Z.Z.; Ahmed, A.S.; Gouda, Y.G. Phytochemical and biological studies of Adiantum capillus-veneris L. Saudi Pharm. J. 2011, 19, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Q.; Zang, X.; Liu, Z.; Song, S.; Xue, P.; Wang, J.; Ruan, J. Ethanol extractof Adiantum capillus-veneris L. suppresses the production of inflammatory mediators by inhibiting NF-κB activation. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013, 147, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, D.C.; Dhanasekaran, M. Medicinal Mushrooms: Recent Progress in Research and Development; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2019; ISBN 9811363811. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, F.; Zhou, L.W.; Yang, Z.L.; Bau, T.; Li, T.H.; Dai, Y.C. Resource Diversity of Chinese Macrofungi: Edible, Medicinal and Poisonous Species; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2019; Volume 98, ISBN 0123456789. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, T.N.; Costa, G.; Ferreira, J.P.; Liberal, J.; Francisco, V.; Paranhos, A.; Cruz, M.T.; Castelo-Branco, M.; Figueiredo, I.V.; Batista, M.T. Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory, and Analgesic Activities of Agrimonia eupatoria L. Infusion. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 2017, 8309894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastian, P.; Fal, A.M.; Jambor, J.; Michalak, A.; Noster, B.; Sievers, H.; Steuber, A.; Walas-Marcinek, N. Candelabra Aloe (Aloe arborescens) in the therapy and prophylaxis of upper respiratory tract infections: Traditional use and recent research results. Wien. Med. Wochenschr. 2013, 163, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hekmatpou, D.; Mehrabi, F.; Rahzani, K.; Aminiyan, A. The effect of Aloe vera clinical trials on prevention and healing of skin wound: A systematic review. Iran. J. Med. Sci. 2019, 44, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jain, S.; Rathod, N.; Nagi, R.; Sur, J.; Laheji, A.; Gupta, N.; Agrawal, P.; Prasad, S. Antibacterial effect of Aloe vera gel against oral pathogens: An in-vitro study. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2016, 10, ZC41–ZC44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwale, M.; Masika, P.J. In vivo anthelmintic efficacy of Aloe ferox, Agave sisalana, and Gunnera perpensa in village chickens naturally infected with Heterakis gallinarum. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2015, 47, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.F.; Liu, C.F.; Lai, W.F.; Xiang, Q.; Li, Z.F.; Wang, H.; Lin, N. The laxative effect of emodin is attributable to increased aquaporin 3 expression in the colon of mice and HT-29 cells. Fitoterapia 2014, 96, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonaterra, G.A.; Bronischewski, K.; Hunold, P.; Schwarzbach, H.; Heinrich, E.U.; Fink, C.; Aziz-Kalbhenn, H.; Müller, J.; Kinscherf, R. Anti-inflammatory and Anti-oxidative Effects of Phytohustil® and Root Extract of Althaea officinalis L. on Macrophages in vitro. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahboubi, M. Marsh Mallow (Althaea officinalis L.) and Its Potency in the Treatment of Cough. Complement. Med. Res. 2020, 27, 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paun, G.; Neagu, E.; Albu, C.; Savin, S.; Radu, G.L. In Vitro Evaluation of Antidiabetic and Anti-Inflammatory Activities of Polyphenolic-Rich Extracts from Anchusa officinalis and Melilotus officinalis. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 13014–13022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Snafi, A.E. The pharmacological importance of Anethum graveolens. A review. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 6, 11–13. [Google Scholar]

- Sowndhararajan, K.; Deepa, P.; Kim, M.; Park, S.J.; Kim, S. A review of the composition of the essential oils and biological activities of Angelica species. Sci. Pharm. 2017, 85, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batiha, G.E.; Olatunde, A.; El-mleeh, A.; Hetta, H.F.; Al-rejaie, S.; Alghamdi, S.; Zahoor, M.; Beshbishy, A.M. Pharmacokinetics of Wormwood (Artemisia absinthium). Antibiotics 2020, 9, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, S.; Ejaz, M.; Dar, K.K.; Nasreen, S.; Ashraf, N.; Gillani, S.F.; Shafi, N.; Safeer, S.; Khan, M.A.; Andleeb, S.; et al. Evaluation of chemopreventive and chemotherapeutic effect of Artemisia vulgaris extract against diethylnitrosamine induced hepatocellular carcinogenesis in balb c mice. Braz. J. Biol. 2020, 80, 484–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeedi, M.; Vahedi-Mazdabadi, Y.; Rastegari, A.; Soleimani, M.; Eftekhari, M.; Akbarzadeh, T.; Khanavi, M. Evaluation of Asarum europaeum L. Rhizome for the Biological Activities Related to Alzheimer’s Disease. Res. J. Pharmacogn. 2020, 7, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M.; Bibi, Y.; Iqbal Raja, N.; Ejaz, M.; Hussain, M.; Yasmeen, F.; Saira, H.; Imran, M. Review on Therapeutic and Pharmaceutically Important Medicinal Plant Asparagus officinalis L. J. Plant Biochem. Physiol. 2017, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, Y.M.; Chin, Y.W.; Yang, M.H.; Kim, J. Terpenoid constituents from the aerial parts of Asplenium scolopendrium. Nat. Prod. Sci. 2008, 14, 265–268. [Google Scholar]

- Tomić, A.; Petrović, S.; Tzakou, O.; Couladis, M.; Milenković, M.; Vučićević, D.; Lakušić, B. Composition and antimicrobial activity of the rhizome essential oils of two Athamanta turbith subspecies. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2009, 21, 276–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi-Samani, M.; Bahmani, M.; Rafieian-Kopaei, M. The chemical composition, botanical characteristic and biological activities of Borago officinalis: A review. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2014, 7, S22–S28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemian, M.; Owlia, S.; Owlia, M.B. Review of Anti-Inflammatory Herbal Medicines. Adv. Pharmacol. Sci. 2016, 2016, 9130979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilani, A.H.; Bashir, S.; Khan, A. ullah Pharmacological basis for the use of Borago officinalis in gastrointestinal, respiratory and cardiovascular disorders. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2007, 114, 393–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirsadraee, M.; Moghaddam, S.K.; Saeedi, P.; Ghaffari, S. Effect of Borago officinalis extract on moderate persistent asthma: A phase two randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Tanaffos 2016, 15, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Yasiry, A.R.M.; Kiczorowska, B. Frankincense—Therapeutic properties. Postepy Hig. Med. Dosw. 2016, 70, 380–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Tawab, M.; Werz, O.; Schubert-Zsilavecz, M. Boswellia serrata. Altern. Med. Rev. 2008, 13, 165–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, M.Z. Boswellia serrata, a potential antiinflammatory agent: An overview. Indian J. Pharm. Sci. 2011, 73, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukiya, M.; Akihisa, T.; Yasukawa, K.; Tokuda, H.; Toriumi, M.; Koike, K.; Kimura, Y.; Nikaido, T.; Aoi, W.; Nishino, H.; et al. Anti-inflammatory and anti-tumor-promoting effects of cucurbitane glycosides from the roots of Bryonia dioica. J. Nat. Prod. 2002, 65, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johri, R.K. Cuminum cyminum and Carum carvi: An update. Pharmacogn. Rev. 2011, 5, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahboubi, M. Caraway as Important Medicinal Plants in Management of Diseases. Nat. Prod. Bioprospect. 2019, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddouks, M.; Lemhadri, A.; Michel, J.B. Hypolipidemic activity of aqueous extract of Capparis spinosa L. in normal and diabetic rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005, 98, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadgoli, C.; Mishra, S.H. Antihepatotoxic activity of p-methoxy benzoic acid from Capparis spinosa. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1999, 66, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Ma, Z.F. Phytochemical and pharmacological properties of Capparis spinosa as a medicinal plant. Nutrients 2018, 10, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkan, T.; Ustunes, L.; Lermioglu, F.; Ozer, A. Antiinflammatory, analgesic, and antipyretic effects of an aqueous extract of Erythraea centaurium. Planta Med. 1991, 57, 34–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mroueh, M.; Saab, Y.; Rizkallah, R. Hepatoprotective activity of Centaurium erythraea on acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in rats. Phyther. Res. 2004, 18, 431–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mabona, U. Antimicrobial activity of southern African medicinal plants with dermatological relevance Unathi Mabona. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013, 148, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiroz, L.S.; Ferreira, E.A.; Mengarda, A.C.; Almeida, A.d.C.; Pinto, P.d.F.; Coimbra, E.S.; de Moraes, J.; Denadai, Â.M.L.; Da Silva Filho, A.A. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of cnicin from blessed thistle (Centaurea benedicta) and its inclusion complexes with cyclodextrins against Schistosoma mansoni. Parasitol. Res. 2020, 120, 1321–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durdević, L.; Mitrović, M.; Pavlović, P.; Bojović, S.; Jarić, S.; Oberan, L.; Gajić, G.; Kostić, O. Total phenolics and phenolic acids content in leaves, rhizomes and rhizosphere soil under Ceterach officinarum D.C., Asplenium trichomanes L. and A. adiantum nigrum L. in the Gorge of Sićevo (Serbia). Ekol. Bratisl. 2007, 26, 164–173. [Google Scholar]

- Zangeneh, M.M.; Zangeneh, A.; Bahrami, E.; Almasi, M.; Amiri-Paryan, A.; Tahvilian, R.; Moradi, R. Evaluation of hematoprotective and hepatoprotective properties of aqueous extract of Ceterach officinarum DC against streptozotocin-induced hepatic injury in male mice. Comp. Clin. Pathol. 2018, 27, 1427–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.J.; Deng, A.J.; Liu, C.; Shi, R.; Qin, H.L.; Wang, A.P. Hepatoprotective activity of Cichorium endivia L. extract and its chemical constituents. Molecules 2011, 16, 9049–9066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warashina, T.; Miyase, T. Sesquiterpenes from the Roots of Cichorium endivia. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2008, 56, 1445–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.H.; Cai, M.; Liu, Y.S.; Sun, P.L.; Luo, S.L. Antibacterial Activity and Mechanisms of Essential Oil from Citrus medica L. var. Sarcodactylis. Molecules 2019, 24, 1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahilrajan, S.; Nandakumar, J.; Kailayalingam, R.; Manoharan, N.A.; SriVijeindran, S.T. Screening the antifungal activity of essential oils against decay fungi from palmyrah leaf handicrafts. Biol. Res. 2014, 47, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Yu, H.; Xie, Y.; Guo, Y.; Fan, J.; Yao, W. The anti-inflammatory potential of Cinnamomum camphora (L.) J.Presl essential oil in vitro and in vivo. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 267, 113516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Qin, J.; Wang, P.; Li, Q.; Yu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y. Chemical composition and larvicidal activities of essential oil of Cinnamomum camphora (L.) leaf against anopheles stephensi. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2020, 53, e20190211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Csikós, E.; Cseko, K.; Ashraf, A.R.; Kemény, Á.; Kereskai, L.; Kocsis, B.; Böszörményi, A.; Helyes, Z.; Horváth, G. Effects of Thymus vulgaris L., Cinnamomum verum J.Presl and Cymbopogon nardus (L.) rendle essential oils in the endotoxin-induced acute airway inflammation mouse model. Molecules 2020, 25, 3553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, L.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, H.; Bari, A.; Ullah, R.; Xue, J. Role of gold nanoparticle from Cinnamomum verum against 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1, 2, 3, 6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) induced mice model. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2019, 201, 111657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.R.; Ramsay, A.; Hansen, T.V.A.; Ropiak, H.M.; Mejer, H.; Nejsum, P.; Mueller-Harvey, I.; Thamsborg, S.M. Anthelmintic activity of trans-cinnamaldehyde and A-and B-type proanthocyanidins derived from cinnamon (Cinnamomum verum). Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 14791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pashmforosh, M.; Vardanjani, H.R.; Vardanjani, H.R.; Pashmforosh, M.; Khodayar, M.J. Topical anti-inflammatory and analgesic activities of Citrullus colocynthis extract cream in rats. Medicina 2018, 54, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-sieni, A.I.I. The antibacterial activity of traditionally used Salvadora persica L. (miswak) and Commiphora gileadensis (palsam) in Saudi Arabia. Afr. J. Tradit. Complement. Altern. Med. 2014, 11, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- El Ashry, E.S.H.; Rashed, N.; Salama, O.M.; Saleh, A. Components, therapeutic value and uses of myrrh. Pharmazie 2003, 58, 163–168. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, J.; Che, D.; Cho, B.; Kang, H.; Kim, J.; Jang, S. Commiphora myrrha inhibits itch-associated histamine and IL-31 production in stimulated mast cells. Exp. Ther. Med. 2019, 1914–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sotoudeh, R.; Hadjzadeh, M.-A.-R.; Gholamnezhad, Z.; Aghaei, A. The anti-diabetic and antioxidant effects of a combination of Commiphora mukul, Commiphora myrrha and Terminalia chebula in diabetic rats. Avicenna J. Phytomed. 2019, 9, 454–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khorasany, A.R.; Hosseinzadeh, H. Therapeutic effects of saffron (Crocus sativus L.) in digestive disorders: A review. Iran. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2016, 19, 455–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kianmehr, M.; Khazdair, M.R. Possible therapeutic effects of Crocus sativus stigma and its petal flavonoid, kaempferol, on respiratory disorders. Pharm. Biol. 2020, 58, 1140–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, H.; Hua, L.J. Crocus sativus L. protects against SDS-induced intestinal damage and extends lifespan in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol. Med. Rep. 2016, 14, 5601–5606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umigai, N.; Takeda, R.; Mori, A. Effect of crocetin on quality of sleep: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study. Complement. Ther. Med. 2018, 41, 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzat, S.M.; Raslan, M.; Salama, M.M.; Menze, E.T.; El Hawary, S.S. In vivo anti-inflammatory activity and UPLC-MS/MS profiling of the peels and pulps of Cucumis melo var. cantalupensis and Cucumis melo var. reticulatus. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2019, 237, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelli, D.; Sahebkar, A.; Johnston, T.P.; Pedone, C. Curcumin use in pulmonary diseases: State of the art and future perspectives. Pharmacol. Res. 2017, 115, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, B.; Stojanović-Radić, Z.; Matejić, J.; Sharifi-Rad, M.; Anil Kumar, N.V.; Martins, N.; Sharifi-Rad, J. The therapeutic potential of curcumin: A review of clinical trials. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 163, 527–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, O.; Salamma, R.; Abbas, L. Screening of antibacterial activity in vitro of Cyclamen hederifolium tubers extracts. Res. J. Pharm. Technol. 2016, 9, 1837–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, G.J.; Hameed, I.H.; Kamal, S.A. Anti-inflammatory effects and other uses of Cyclamen species: A review. Indian J. Public Health Res. Dev. 2018, 9, 206–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segneanu, A.-E.; Cepan, C.; Grozescu, I.; Cziple, F.; Olariu, S.; Ratiu, S.; Lazar, V.; Marius Murariu, S.; Maria Velciov, S.; Daniela Marti, T. Therapeutic Use of Some Romanian Medicinal Plants. Pharmacogn.-Med. Plants 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udefa, A.L.; Amama, E.A.; Archibong, E.A.; Nwangwa, J.N.; Adama, S.; Inyang, V.U.; Inyaka, G.U.-u.; Aju, G.J.; Okpa, S.; Inah, I.O. Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic effects of hydro-ethanolic extract of Cyperus esculentus L. (tigernut) on lead acetate-induced testicular dysfunction in Wistar rats. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 129, 110491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, T.; Cawood, M.; Iqbal, Q.; Ariño, A.; Batool, A.; Sabir Tariq, R.M.; Azam, M.; Akhtar, S. Phytochemicals in Daucus carota and their health benefits—review article. Foods 2019, 8, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.P.; Chauhan, N.S.; Padh, H.; Rajani, M. Search for antibacterial and antifungal agents from selected Indian medicinal plants. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2006, 107, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobeen, A.; Siddiqui, M.A.; Khan, I.; Quamri, M.A.; Itrat, M.; Khan, M.I. Therapeutic potential of Ushaq (Dorema ammoniacum D. Don): A unique drug of Unani medicine. Int. J. Unani Integr. Med. 2018, 2, 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- Mottaghipisheh, J.; Vitalini, S.; Pezzani, R.; Iriti, M. A comprehensive Review on Ethnobotanical, Phytochemical and Pharmacological Aspects of the Genus Dorema; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2021; ISBN 0123456789. [Google Scholar]

- Rajani, M.; Saxena, N.; Ravishankara, M.N.; Desai, N.; Padh, H. Evaluation of the antimicrobial activity of ammoniacum gum from Dorema ammoniacum. Pharm. Biol. 2002, 40, 534–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bozorgi, M.; Amin, G.; Shekarchi, M.; Rahimi, R. Traditional medical uses of Drimia species in terms of phytochemistry, pharmacology and toxicology. J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2017, 37, 124–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erhirhie, E.O.; Emeghebo, C.N.; Ilodigwe, E.E.; Ajaghaku, D.L.; Umeokoli, B.O.; Eze, P.M.; Ngwoke, K.G.; Chiedu Okoye, F.B.G. Dryopteris filix-mas (L.) Schott ethanolic leaf extract and fractions exhibited profound anti-inflammatory activity. Avicenna J. Phytomed. 2019, 9, 396–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meot-Duros, L.; Le Floch, G.; Magné, C. Radical scavenging, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of halophytic species. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2008, 116, 258–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.J.; Tsai, Y.C.; Hwang, T.L.; Wang, T.C. Thymol, benzofuranoid, and phenylpropanoid derivatives: Anti-inflammatory constituents from Eupatorium cannabinum. J. Nat. Prod. 2011, 74, 1021–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lexa, A.; Fleurentin, J.; Lehr, P.R.; Mortier, F.; Pruvost, M.; Pelt, J.M. Choleretic and hepatoprotective properties of Eupatorium cannabinum in the rat. Planta Med. 1989, 55, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lone, B.A.; Bandh, S.A.; Chishti, M.Z.; Bhat, F.A.; Tak, H.; Nisa, H. Anthelmintic and antimicrobial activity of methanolic and aqueous extracts of Euphorbia helioscopia L. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2013, 45, 743–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.; Liu, L.; Huang, J.; Yu, H.; Wu, H.; Duan, Y.; Cui, X.; Zhang, X.; Liu, L.; Wang, W. Laxative effects of total diterpenoids extracted from the roots of euphorbia pekinensis are attributable to alterations of aquaporins in the colon. Molecules 2017, 22, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farid-Afshar, F.; Saffarian, P.; Mahmoodzadeh-Hosseini, H.; Sattarian, F.; Amin, M.; Fooladi, A.A.I. Antimicrobial effects of Ferula gummosa boiss gum against extended-spectrum β-lactamase producing Acinetobacter clinical isolates. Iran. J. Microbiol. 2016, 8, 263–273. [Google Scholar]

- Masoumi-Ardakani, Y.; Mandegary, A.; Esmaeilpour, K.; Najafipour, H.; Sharififar, F.; Pakravanan, M.; Ghazvini, H. Chemical composition, anticonvulsant activity, and toxicity of essential oil and methanolic extract of Elettaria cardamomum. Planta Med. 2016, 82, 1482–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazemisalman, B.; Vahabi, S.; Yazdinejad, A.; Haghghi, F.; Jam, M.; Heydari, F. Comparison of antimicrobial effect of Ziziphora tenuior, Dracocephalum moldavica, Ferula gummosa, and Prangos ferulacea essential oil with chlorhexidine on Enterococcus faecalis: An in vitro study. Dent. Res. J. (Isfahan) 2018, 15, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badgujar, S.B.; Patel, V.V.; Bandivdekar, A.H. Foeniculum vulgare Mill: A Review of Its Botany, Phytochemistry, Pharmacology, Contemporary Application, and Toxicology. Biomed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 842674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pǎltinean, R.; Mocan, A.; Vlase, L.; Gheldiu, A.M.; Crişan, G.; Ielciu, I.; Voştinaru, O.; Crişan, O. Evaluation of polyphenolic content, antioxidant and diuretic activities of six Fumaria species. Molecules 2017, 22, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raafat, K.M.; El-Zahaby, S.A. Niosomes of active Fumaria officinalis phytochemicals: Antidiabetic, antineuropathic, anti-inflammatory, and possible mechanisms of action. Chin. Med. (UK) 2020, 15, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pundarikakshudu, K.; Patel, J.K.; Bodar, M.S.; Deans, S.G. Anti-bacterial activity of Galega officinalis L. (Goat’s Rue). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2001, 77, 111–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, S.T.; Lin, T.H.; Peng, H.Y.; Chao, W.W. Phytochemical profile of hot water extract of Glechoma hederacea and its antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory activities. Life Sci. 2019, 231, 116519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batiha, G.E.S.; Beshbishy, A.M.; El-Mleeh, A.; Abdel-Daim, M.M.; Devkota, H.P. Traditional uses, bioactive chemical constituents, and pharmacological and toxicological activities of Glycyrrhiza glabra L. (fabaceae). Biomolecules 2020, 10, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, S.; Sun, L.; He, F.; Che, H. Anti-Allergic activity of glycyrrhizic acid on IgE-mediated allergic reaction by regulation of allergy-related immune cells. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 7222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Liu, B.; Cao, B.; Wei, F.; Yu, X.; Li, G.-f.; Chen, H.; Wei, L.-q.; Wang, P. Lan Synergistic protection of Schizandrin B and Glycyrrhizic acid against bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis by inhibiting TGF-β1/Smad2 pathways and overexpression of NOX4. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2017, 48, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Li, G.; Ding, Y.; Ren, T.; Zheng, J.; Kan, J. Effect of Whole Grain Qingke (Tibetan Hordeum vulgare L. Zangqing 320) on the Serum Lipid Levels and Intestinal Microbiota of Rats under High-Fat Diet. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 2686–2693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Pu, X.; Yang, J.; Du, J.; Yang, X.; Li, X.; Li, L.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, T. Preventive and therapeutic role of functional ingredients of barley grass for chronic diseases in human beings. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 3232080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, K.D.P.; Birt, D.F. Evidence for Contributions of Interactions of Constituents to the Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Hypericum Perforatum. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2014, 54, 781–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saddiqe, Z.; Naeem, I.; Maimoona, A. A review of the antibacterial activity of Hypericum perforatum L. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2010, 131, 511–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercier, B.; Prost, J.; Prost, M. The essential oil of turpentine and its major volatile fraction (α- and β-pinenes): A review. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Health 2009, 22, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schelz, Z.; Molnar, J.; Hohmann, J. Antimicrobial and antiplasmid activities of essential oils. Fitoterapia 2006, 77, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sipponen, A.; Laitinen, K. Antimicrobial properties of natural coniferous rosin in the European Pharmacopoeia challenge test. Apmis 2011, 119, 720–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almohawes, Z.N.; Alruhaimi, H.S. Effect of Lavandula dentata extract on ovalbumin-induced asthma in male Guinea pigs. Braz. J. Biol. 2020, 80, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaccai, M.; Yarmolinsky, L.; Khalfin, B.; Budovsky, A.; Gorelick, J.; Dahan, A.; Ben-Shabat, S. Medicinal properties of Lilium candidum L. and its phytochemicals. Plants 2020, 9, 959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafieian-kopaei, M.; Shakiba, A.; Sedighi, M.; Bahmani, M. The Analgesic and Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Linum usitatissimum in Balb/c Mice. J. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 22, 892–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patocka, J.; Bhardwaj, K.; Klimova, B.; Nepovimova, E.; Wu, Q.; Landi, M.; Kuca, K.; Valis, M.; Wu, W. Malus domestica: A review on nutritional features, chemical composition, traditional and medicinal value. Plants 2020, 9, 1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, T.; Miyake, M.; Toba, M.; Okamatsu, H.; Shimizu, S.; Noda, M. Inhibition by apple polyphenols of ADP-ribosyltransferase activity of cholera toxin and toxin-induced fluid accumulation in mice. Microbiol. Immunol. 2002, 46, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, R.K.; Walters, E.H.; Raven, J.M.; Wolfe, R.; Ireland, P.D.; Thien, F.C.K.; Abramson, M.J. Food and nutrient intakes and asthma risk in young adults. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 78, 414–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, O.; Khanam, Z.; Misra, N.; Srivastava, M.K. Chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla). An overview. Pharm. Rev. 2011, 5, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubert, P.; Guinobert, I.; Blondeau, C.; Bardot, V.; Ripoche, I.; Chalard, P.; Neunlist, M. Basal and spasmolytic effects of a hydroethanolic leaf extract of Melissa officinalis L. on intestinal motility: An ex vivo study. J. Med. Food 2019, 22, 653–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azhar, A.S.; El-Bassossy, H.M.; Abdallah, H.M. Mentha longifolia alleviates experimentally induced angina via decreasing cardiac load. J. Food Biochem. 2019, 43, e12702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rad, S.S.; Sani, A.M.; Mohseni, S. Biosynthesis, characterization and antimicrobial activities of zinc oxide nanoparticles from leaf extract of Mentha pulegium (L.). Microb. Pathog. 2019, 131, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgarpanah, J.; Kazemivash, N. Phytochemistry and pharmacologic properties of Myristica fragrans Hoyutt: A review. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2012, 11, 12787–12793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.D.; Bansal, V.K.; Babu, V.; Maithil, N. Chemistry, antioxidant and antimicrobial potential of nutmeg (Myristica fragrans Houtt). J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2013, 11, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, P.; Kumar, P.; Singh, V.K.; Singh, D.K. ARBS Annual Review of Biomedical Sciences Biological Effects of Myristica fragrans. ARBS Annu. Rev. Biomed. Sci. 2009, 11, 21–29. [Google Scholar]

- Olajide, O.A.; Ajayi, F.F.; Ekhelar, A.I.; Awe, S.O.; Makinde, J.M.; Alada, A.R.A. Biological effects of Myristica fragrans (nutmeg) extract. Phyther. Res. 1999, 13, 344–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alipour, G.; Dashti, S.; Hosseinzadeh, H. Review of pharmacological effects of Myrtus communis L. and its active constituents. Phyther. Res. 2014, 28, 1125–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennia, A.; Miguel, M.; Nemmiche, S. Antioxidant Activity of Myrtus communis L. and Myrtus nivellei Batt. & Trab. Extracts: A Brief Review. Medicines 2018, 5, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumbul, S.; Aftab Ahmad, M.; Asif, M.; Akhtar, M. Myrtus communis Linn.—A review. Indian J. Nat. Prod. Resour. 2011, 2, 395–402. [Google Scholar]

- Amalraj, A.; Gopi, S. Biological activities and medicinal properties of Asafoetida: A review. J. Tradit. Complement. Med. 2017, 7, 347–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahendra, P.; Bisht, S. Ferula asafoetida: Traditional uses and pharmacological activity. Pharmacogn. Rev. 2012, 6, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toma, C.C.; Olah, N.K.; Vlase, L.; Mogoşan, C.; Mocan, A. Comparative studies on polyphenolic composition, antioxidant and diuretic effects of Nigella sativa L. (black cumin) and Nigella damascena L. (Lady-in-a-Mist) seeds. Molecules 2015, 20, 9560–9574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Husain, A.; Mujeeb, M.; Khan, S.A.; Najmi, A.K.; Siddique, N.A.; Damanhouri, Z.A.; Anwar, F. A review on therapeutic potential of Nigella sativa: A miracle herb. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2013, 3, 337–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanbari, R.; Anwar, F.; Alkharfy, K.M.; Gilani, A.H.; Saari, N. Valuable Nutrients and Functional Bioactives in Different Parts of Olive (Olea europaea L.)—A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012, 13, 3291–3340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karygianni, L.; Cecere, M.; Argyropoulou, A.; Hellwig, E.; Skaltsounis, A.L.; Wittmer, A.; Tchorz, J.P.; Al-Ahmad, A. Compounds from Olea europaea and Pistacia lentiscus inhibit oral microbial growth. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2019, 19, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romani, A.; Ieri, F.; Urciuoli, S.; Noce, A.; Marrone, G.; Nediani, C.; Bernini, R. Health effects of phenolic compounds found in extra-virgin olive oil, by-products, and leaf of Olea europaea L. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi-Maleki, S.; Kadkhoda, Z.; Taghizad-Farid, R. The antidepressant-like effects of Origanum majorana essential oil on mice through monoaminergic modulation using the forced swimming test. J. Tradit. Complement. Med. 2020, 10, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algera, M.H.; Kamp, J.; van der Schrier, R.; van Velzen, M.; Niesters, M.; Aarts, L.; Dahan, A.; Olofsen, E. Opioid-induced respiratory depression in humans: A review of pharmacokinetic–pharmacodynamic modelling of reversal. Br. J. Anaesth. 2019, 122, e168–e179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benyamin, R.; Trescot, A.M.; Datta, S.; Buenaventura, R.; Adlaka, R.; Sehgal, N.; Glaser, S.E.; Vallejo, R. Opioid complications and side effects. Pain Physician 2008, 11, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Serranillos, M.P.; Palomino, O.M.; Carretero, E.; Villar, A. Analytical study and analgesic activity of oripavine from Papaver somniferum L. Phyther. Res. 1998, 12, 346–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, S.; Huang, J.; Ren, Y.; Zhi, F.; Tian, X.; Wen, G.; Ding, G.; Xia, T.C.; Hua, F.; Xia, Y. Neuroprotection against Hypoxic/Ischemic Injury: δ-Opioid Receptors and BDNF-TrkB Pathway. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 47, 302–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shenoy, S.S.; Lui, F. Biochemistry, Endogenous Opioids. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, J. Petasites hybridus Monograph. Altern. Med. Rev. 2001, 6, 207–209. [Google Scholar]

- Farzaei, M.H.; Abbasabadi, Z.; Ardekani, M.R.S.; Rahimi, R.; Farzaei, F. Parsley: A review of ethnopharmacology, phytochemistry and biological activities. J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2013, 33, 815–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shojaii, A.; Abdollahi Fard, M. Review of Pharmacological Properties and Chemical Constituents of Pimpinella anisum. ISRN Pharm. 2012, 2012, 510795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ksouda, G.; Sellimi, S.; Merlier, F.; Falcimaigne-cordin, A.; Thomasset, B.; Nasri, M.; Hajji, M. Composition, antibacterial and antioxidant activities of Pimpinella saxifraga essential oil and application to cheese preservation as coating additive. Food Chem. 2019, 288, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Malhotra, S.; Prasad, A.; Eycken, E.; Bracke, M.; Stetler-Stevenson, W.; Parmar, V.; Ghosh, B. Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant Properties of Piper Species: A Perspective from Screening to Molecular Mechanisms. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2015, 15, 886–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damanhouri, Z.A. A Review on Therapeutic Potential of Piper nigrum L. (Black Pepper): The King of Spices. Med. Aromat. Plants 2014, 3, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahak, G.; Sahu, R.K. Phytochemical evaluation and antioxidant activity of Piper cubeba and Piper nigrum. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2011, 1, 153–157. [Google Scholar]

- Salehi, B.; Zakaria, Z.A.; Gyawali, R.; Ibrahim, S.A.; Rajkovic, J.; Shinwari, Z.K.; Khan, T.; Sharifi-Rad, J.; Ozleyen, A.; Turkdonmez, E.; et al. Piper Species: A Comprehensive Review on Their Phytochemistry, Biological Activities and Applications. Molecules 2019, 24, 1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozorgi, M.; Memariani, Z.; Mobli, M.; Salehi Surmaghi, M.H.; Shams-Ardekani, M.R.; Rahimi, R. Five pistacia species (P. vera, P. atlantica, P. terebinthus, P. khinjuk, and P. lentiscus): A review of their traditional uses, phytochemistry, and pharmacology. Sci. World J. 2013, 2013, 219815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nirumand, M.C.; Hajialyani, M.; Rahimi, R.; Farzaei, M.H.; Zingue, S.; Nabavi, S.M.; Bishayee, A. Dietary plants for the prevention and management of kidney stones: Preclinical and clinical evidence and molecular mechanisms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dar, P.A.; Sofi, G.; Jafri, M.A. Polypodium vulgare Linn. a versatile herbal medicine: A review. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 2012, 3, 1616–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.X.; Xin, H.L.; Rahman, K.; Wang, S.J.; Peng, C.; Zhang, H. Portulaca oleracea L.: A review of phytochemistry and pharmacological effects. Biomed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 925631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomczyk, M.; Leszczyńska, K.; Jakoniuk, P. Antimicrobial activity of Potentilla species. Fitoterapia 2008, 79, 592–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, N.U.; Amin, R.; Shahid, M.; Amin, M.; Zaib, S.; Iqbal, J. A multi-target therapeutic potential of Prunus domestica gum stabilized nanoparticles exhibited prospective anticancer, antibacterial, urease-inhibition, anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 17, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arena, A.; Bisignano, C.; Stassi, G.; Filocamo, A.; Mandalari, G. Almond skin inhibits HSV-2 replication in peripheral blood mononuclear cells by modulating the cytokine network. Molecules 2015, 20, 8816–8822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bottone, A.; Montoro, P.; Masullo, M.; Pizza, C.; Piacente, S. Metabolomics and antioxidant activity of the leaves of Prunus dulcis Mill (Italian cvs. Toritto and Avola). J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2018, 158, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorji, N.; Moeini, R.; Memariani, Z. Almond, hazelnut and walnut, three nuts for neuroprotection in Alzheimer’s disease: A neuropharmacological review of their bioactive constituents. Pharmacol. Res. 2018, 129, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilani, A.H.; Aziz, N.; Ali, S.M.; Saeed, M. Pharmacological basis for the use of peach leaves in constipation. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2000, 73, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D. Anti-inflammatory, analgesic, and antioxidant activities of methanolic wood extract of Pterocarpus santalinus L. J. Pharmacol. Pharmacother. 2011, 2, 200–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, S.; Veeraraghavan, M.; Devi, C.S. Pterocarpus santalinus: An in vitro study on its anti-Helicobacter pylori effect. Phyther. Res. 2007, 21, 190–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neagu, E.; Radu, G.L.; Albu, C.; Paun, G. Antioxidant activity, acetylcholinesterase and tyrosinase inhibitory potential of Pulmonaria officinalis and Centarium umbellatum extracts. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2018, 25, 578–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Khalil, S.; Turabi, Z.; Musmar, M.; Yaish, S. Antispasmodic activity of Rosmarinus officinalis and Ruscus aculeatus. Bethlehem Univ. J. 2002, 21, 54–60. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Y.; Sun, M.; Xing, J.; Corke, H. Antioxidant phenolic constituents in roots of Rheum officinale and Rubia cordifolia: Structure-radical scavenginq activity relationships. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 7884–7890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, D.C.; Wang, L. Mechanisms of therapeutic effects of rhubarb on gut origin sepsis. Chin. J. Traumatol. (Engl. Ed.) 2009, 12, 365–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basim, E.; Basim, H. Antibacterial activity of Rosa damascena essential oil. Fitoterapia 2003, 74, 394–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cendrowski, A.; Krasniewska, K.; Przybył, J.L.; Zielinska, A.; Kalisz, S. Antibacterial and Antioxidant Activity of Extracts from Rose Fruits (Rosa rugosa). Molecules 2020, 25, 1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolati, K.; Rakhshandeh, H.; Shafei, M.N. Effect of aqueous fraction of Rosa damascena on ileum contractile response of guinea pigs. Avicenna J. Phytomedicine 2013, 3, 248–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lattanzio, F.; Greco, E.; Carretta, D.; Cervellati, R.; Govoni, P.; Speroni, E. In vivo anti-inflammatory effect of Rosa canina L. extract. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011, 137, 880–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mileva, M.; Ilieva, Y.; Jovtchev, G.; Gateva, S.; Zaharieva, M.M.; Georgieva, A.; Dimitrova, L.; Dobreva, A.; Angelova, T.; Vilhelmova-Ilieva, N.; et al. Rose flowers—A delicate perfume or a natural healer? Biomolecules 2021, 11, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade, J.M.; Faustino, C.; García, C.; Ladeiras, D.; Reis, C.P.; Rijo, P. Rosmarinus officinalis L.: An update review of its phytochemistry and biological activity Joana. Futur. Sci. 2018, 4, FSO283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Oliveira, J.R.; Esteves, S.; Camargo, A. Rosmarinus officinalis L. (rosemary) as therapeutic and prophylactic agent. J. Biomed. Sci. 2019, 8, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, A.; Mekhfi, H.; Ziyyat, A.; Legssyer, A.; Bnouham, M.; Amrani, S.; Atmani, F.; Melhaoui, A.; Aziz, M. Anti-diarrhoeal activity of crude aqueous extract of Rubia tinctorum L. roots in rodents. J. Smooth Muscle Res. 2010, 46, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Velde, F.; Esposito, D.; Grace, M.H.; Pirovani, M.E.; Lila, M.A. Anti-inflammatory and wound healing properties of polyphenolic extracts from strawberry and blackberry fruits. Food Res. Int. 2019, 121, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilic, I.; Yesiloglu, Y.; Bayrak, Y.; Gülen, S.; Bakkal, T. Antioxidant activity of Rumex conglomeratus P. Collected from turkey. Asian J. Chem. 2013, 25, 9683–9687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orbán-Gyapai, O.; Liktor-Busa, E.; Kúsz, N.; Stefkó, D.; Urbán, E.; Hohmann, J.; Vasas, A. Antibacterial screening of Rumex species native to the Carpathian Basin and bioactivity-guided isolation of compounds from Rumex aquaticus. Fitoterapia 2017, 118, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loonat, F.; Amabeoku, G.J. imboyek. Antinociceptive, anti-inflammatory and antipyretic activities of the leaf methanol extract of Ruta graveolens L. (Rutaceae) in mice and rats. Afr. J. Tradit. Complement. Altern. Med. 2014, 11, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, H.A.; Venkatesh, S.; Senthilkumar, R.; Kumar, B.S.G.; Ali, A.M. Determination of antibacterial activity and metabolite profile of Ruta graveolens against Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus sobrinus. J. Lab. Physicians 2018, 10, 320–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, I.B.; Rafaela Damasceno, S.; Maco, D.P.C.; Randau, K.P. Use of medicinal plants in the treatment of erysipelas: A review. Pharmacogn. Rev. 2018, 12, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbari, M.; Daneshfard, B.; Emtiazy, M.; Khiveh, A.; Hashempur, M.H. Biological Effects and Clinical Applications of Dwarf Elder (Sambucus ebulus L.): A Review. J. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 22, 996–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaradat, N.A.; Zaid, A.N.; Al-Ramahi, R.; Alqub, M.A.; Hussein, F.; Hamdan, Z.; Mustafa, M.; Qneibi, M.; Ali, I. Ethnopharmacological survey of medicinal plants practiced by traditional healers and herbalists for treatment of some urological diseases in the West Bank/Palestine. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 17, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quave, C.L.; Plano, L.R.W.; Bennett, B.C. Quorum sensing inhibitors of Staphylococcus aureus from Italian medicinal plants. Planta Med. 2011, 77, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehzadeh, A.; Asadpour, L.; Naeemi, A.S.; Houshmand, E. Antimicrobial activity of methanolic extracts of Sambucus ebulus and Urtica dioica against clinical isolates of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Afr. J. Tradit. Complement. Altern. Med. 2014, 11, 38–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokrzadeh, M.; Saeedi Saravi, S.S. The chemistry, pharmacology and clinical properties of Sambucus ebulus: A review. J. Med. Plants Res. 2010, 4, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasinov, O.; Kiselova-Kaneva, Y.; Ivanova, D. Sambucus ebulus—From traditional medicine to recent studies. Scr. Sci. Med. 2013, 45, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Harnett, J.; Oakes, K.; Carè, J.; Leach, M.; Brown, D.; Holger, C.; Pinder, T.-A.; Steel, A.; Anheyer, D. The effects of Sambucus nigra berry on acute respiratory viral infections: A rapid review of clinical studies. Adv. Integr. Med. 2020, 7, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ESCOP—European Scientific Cooperative of Phytotherapy. ESCOP Monographs—Sambuci Flos—Elder Flower, 3rd ed.; ESCOP, Ed.; Thieme Publishing Group: Stuttgard, Germany, 2013; ISBN 978-1-901964-11-0. [Google Scholar]

- Roxas, M.; Jurenka, J. Colds and influenza: A review of diagnosis and conventional, botanical, and nutritional considerations. Altern. Med. Rev. 2007, 12, 25–48. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sargin, S.A. Potential anti-influenza effective plants used in Turkish folk medicine: A review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 265, 113319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, B.; Gao, Y.; Ji, J.; Wu, Z.; Chen, S. Saponins from Sanguisorba officinalis improve hematopoiesis by promoting survival through FAK and Erk1/2 activation and modulating cytokine production in bone marrow. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, B.B.; Dey, S. Comparative phytochemical analysis and antibacterial efficacy of in vitro and in vivo extracts from East Indian sandalwood tree (Santalum album L.). Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2012, 55, 476–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suganya, K.; Liu, Q.F.; Koo, B.S. Santalum album extract exhibits neuroprotective effect against the TLR3-mediated neuroinflammatory response in human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells. Phyther. Res. 2021, 35, 1991–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivanco, J.M.; Tumer, N.E. Translation inhibition of capped and uncapped viral RNAs mediated by ribosome-inactivating proteins. Phytopathology 2003, 93, 588–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayromlou, A.; Masoudi, S.; Mirzaie, A. Chemical composition, antioxidant, antibacterial, and anticancer activities of Scorzonera calyculata boiss. And Centaurea irritans wagenitz. Extracts, endemic to iran. J. Rep. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 9, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küpeli Akkol, E.; Acikara, O.B.; Süntar, I.; Citolu, G.S.; Kele, H.; Ergene, B. Enhancement of wound healing by topical application of Scorzonera species: Determination of the constituents by HPLC with new validated reverse phase method. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011, 137, 1018–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sweidan, A.; El-Mestrah, M.; Kanaan, H.; Dandache, I.; Merhi, F.; Chokr, A. Antibacterial and antibiofilm activities of Scorzonera mackmeliana. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 33, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seigner, J.; Junker-Samek, M.; Plaza, A.; D’Urso, G.; Masullo, M.; Piacente, S.; Holper-Schichl, Y.M.; De Martin, R. A Symphytum officinale root extract exerts anti-inflammatory properties by affecting two distinct steps of NF-κB signaling. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pareek, A.; Suthar, M.; Rathore, G.S.; Bansal, V. Feverfew (Tanacetum parthenium L.): A systematic review. Pharmacogn. Rev. 2011, 5, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wider, B.; Pittler, M.H.; Ernst, E. Feverfew for preventing migraine. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 2015, CD002286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimifard, M.; Navaei-Nigjeh, M.; Mahroui, N.; Mirzaei, S.; Siahpoosh, Z.; Nili-Ahmadabadi, A.; Mohammadirad, A.; Baeeri, M.; Hajiaghaie, R.; Abdollahi, M. Improvement in the function of isolated rat pancreatic islets through reduction of oxidative stress using traditional Iranian medicine. Cell J. 2014, 16, 147–162. [Google Scholar]

- Gilani, A.H.; Bashir, S.; Memon, R. Antispasmodic and antidiarrheal activities of Valeriana hardwickii wall. Rhizome are putatively mediated through calcium channel blockade. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2011, 2011, 304960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skalicka-Woźniak, K.; Walasek, M.; Aljarba, T.M.; Stapleton, P.; Gibbons, S.; Xiao, J.; Łuszczki, J.J. The anticonvulsant and anti-plasmid conjugation potential of Thymus vulgaris chemistry: An in vivo murine and in vitro study. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2018, 120, 472–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Park, S.Y.; Hwang, E.; Zhang, M.; Seo, S.A.; Lin, P.; Yi, T.H. Thymus vulgaris alleviates UVB irradiation induced skin damage via inhibition of MAPK/AP-1 and activation of Nrf2-ARE antioxidant system. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2017, 21, 336–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pundarikakshudu, K.; Shah, D.H.; Panchal, A.H.; Bhavsar, G.C. Anti-inflammatory activity of fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum Linn) seed petroleum ether extract. Indian J. Pharmacol. 2016, 48, 441–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Shrivastav, V.; Shrivastav, A.; Shrivastav, B. Therapeutic potential of wheatgrass (Triticum aestivum L.) for the treat-ment of chronic diseases. South Asian J. Exp. Biol. 2014, 3, 308–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, B.; Shetty, M.S.; Anil Kumar, N.V.; Živković, J.; Calina, D.; Docea, A.O.; Emamzadeh-Yazdi, S.; Kılıç, C.S.; Goloshvili, T.; Nicola, S.; et al. Veronica plants—Drifting from farm to traditional healing, food application, and phytopharmacology. Molecules 2019, 24, 2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piana, M.; Silva, M.A.; Trevisan, G.; De Brum, T.F.; Silva, C.R.; Boligon, A.A.; Oliveira, S.M.; Zadra, M.; Hoffmeister, C.; Rossato, M.F.; et al. Antiinflammatory effects of Viola tricolor gel in a model of sunburn in rats and the gel stability study. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013, 150, 458–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, B.; Azam, S.; Bashir, S.; Khan, I.; Adhikari, A.; Choudhary, M.I. Anti-inflammatory and enzyme inhibitory activities of a crude extract and a pterocarpan isolated from the aerial parts of Vitex agnus-castus. Biotechnol. J. 2010, 5, 1207–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, F.; Di Lorenzo, C.; Regazzoni, L.; Fumagalli, M.; Sangiovanni, E.; Peres De Sousa, L.; Bavaresco, L.; Tomasi, D.; Bosso, A.; Aldini, G.; et al. Phenolic profiles and anti-inflammatory activities of sixteen table grape (Vitis vinifera L.) varieties. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 1797–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bazh, E.K.A.; El-Bahy, N.M. In vitro and in vivo screening of anthelmintic activity of ginger and curcumin on Ascaridia galli. Parasitol. Res. 2013, 112, 3679–3686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haniadka, R.; Saldanha, E.; Sunita, V.; Palatty, P.L.; Fayad, R.; Baliga, M.S. A review of the gastroprotective effects of ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe). Food Funct. 2013, 4, 845–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddaraju, M.N.; Dharmesh, S.M. Inhibition of gastric H+,K+-ATPase and Helicobacter pylori growth by phenolic antioxidants of Zingiber officinale. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2007, 51, 324–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Index Omnium Medicamentorum, & Compositionum, quae Reperiuntur in Aromataria Ve. Hospitalis Maioris Mediolani, (…); Archivio Ospedale Maggiore, Servizio sanitario e di culto ex Archivio Bianco SAN524, Ed.; 1711. [Google Scholar]

- Index omnium Medicamentorum, & Compositionum, quae reperiuntur in Aromataria Ve. Hospitalis Maioris Mediolani, (…); Archivio Ospedale Maggiore, Servizio sanitario e di culto ex Archivio Bianco SAN524, Ed.; 1729. [Google Scholar]

- Index Medicamentorum simplicium & compositorum Ad usum Nosocomii Maioris Mediolani; Archivio Ospedale Maggiore, Servizio sanitario e di culto ex Archivio Bianco SAN524, Ed.; 1760. [Google Scholar]

- Articoli Provenienti da Piazze Estere; Archivio Ospedale Maggiore, Servizio sanitario e di culto ex Archivio Bianco SAN524, Ed.; 1793. [Google Scholar]

- Nuova Farmacopea ad uso Dell’ospedale civico di Milano, ed Annesso L.P. di Santa Corona; Archivio Ospedale Maggiore, Servizio sanitario e di culto ex Archivio Bianco SAN523, Ed.; Tipografia Pulini in Cordusio: Milano, Italy, 1809. [Google Scholar]

- Pharmacopoea Austriaca Oeconomiae Nosocomii Civici Generalis Mediolanensi adcomodata; Archivio Ospedale Maggiore, Direzione medica ex Archivio Rosso DIR579, Ed.; 1810–1820.

- Pharmacopoea Austriaca. Tertia Editio Emendata; Archivio Ospedale Maggiore, Servizio sanitario e di culto ex Archivio Bianco SAN525, Ed.; Mediolani: Imp. Regiis Typis: Milano, Italy, 1819.

- Pharmacopoea in usum Nosocomii Majoris Mediolanensis; Archivio Ospedale Maggiore, Direzione medica ex Archivio Rosso DIR578, Ed.; 1839. [Google Scholar]

- Pharmacopoea ad usum Nosocomii Civici Generalis Mediolanensis anno 1789—Milano: Mediolani; Bianchi e Motta: Milano, Italy, 1789.

- Mandegary, A.; Sayyah, M.; Reza Heidari, M. Antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory activity of the seed and root extracts of Ferula gummosa Boiss in mice and rats. Daru 2004, 12, 58–62. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, I.; Gupta, V.; Parihar, A.; Gupta, S.; Lüdtke, R.; Safayhi, H.; Ammon, H.P. Effects of Boswellia serrata gum resin in patients with bronchial asthma: Results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled, 6-week clinical study. Eur. J. Med. Res. 1998, 3, 511–514. [Google Scholar]

- Ayromlou, A.; Masoudi, S.; Mirzaie, A. Scorzonera calyculata Aerial Part Extract Mediated Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles: Evaluation of Their Antibacterial, Antioxidant and Anticancer Activities. J. Clust. Sci. 2019, 30, 1037–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trescot, A.M.; Datta, S.; Lee, M.; Hans, H. Opioid pharmacology. Pain Physician 2008, 11, 133–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Vase Number | Vase Inscription | Plant Ingredients (Genus/Species) | Historical Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Aqua Moli | Mythological plant (still unknown) useful for potions and spells | |

| 3 | Aqua Aequi. | Equisetum arvense L. | [8] |

| 4 | Trochiscus Alhandal. | Citrullus colocynthis (L.) Schrad. | [9] |

| 6 | Unguentum Lapatÿ | Cinnamomum camphora (L.) J. Presl, Rosa spp., Rumex conglomeratus Murray, Viola spp. | [10,11] |

| 7 | Unguentum Agrippae | Bryonia spp., Drimia maritima (L.) Stern, Ecballium elaterium (L.) A. Rich., Eryngium maritimum L., Pistacia lentiscus L., Sambucus ebulus L. | [10,11] |

| 9 | Electuarium Diacurcumae | Acorus calamus L., Artemisia absinthium L., Ceterach officinarum Willd., Cinnamomum verum J. Presl, Commiphora gileadensis (L.) C. Chr., Commiphora myrra Nees, Crocus spp. or Crocus sativus L., Curcuma longa L., Cyperus esculentus L., Daucus carota L., Eupatorium cannabinum L., Glycyrrhiza glabra L., Lavandula dentata L., Papaver somniferum L., Pimpinella anisum L., Rheum officinale L., Rubia tinctorum L., Teucrium scordium L., Valeriana spp. | [12] |

| 10 | Unguentum Rosati | Prunus dulcis (Mill.) D.A. Webb, Rosa spp. | [10,11] |

| 11 | Trochiscus Absÿnthi | Artemisia absinthium L., Asarum europeum L., Lavandula dentata L., Rosa spp. | [9] |

| 13 | Trochiscus d. Myrtha. | Myrtus communis L. | - |

| 14 | Conserva Hamech. | Artemisia absenthium L., Citrullus colocynthis (L.) Schrad., Pimpinella anisum L., Polypodium vulgare L., Prunus domestica L., Rosa spp., Thymus spp., Viola spp. | [9] |

| 15 | Unguentum Pectorale | Althaea officinalis L., Anethum graveolens L., Myristica fragrans Houtt., Prunus dulcis (Miller) D.A. Webb, Rosmarinus officinalis L. | [13] |

| 16 | Aqua Aequi. | Equisetum arvense L. | [8] |

| 17 | Trochiscus de Agarici | Agaricus campestris L., Agaricus bisporus (J.E. Lange) Imbach, Zingiber officinale Roscoe | [10,11,14] |

| 18 | Oleum Nucis. mÿrist. | Myristica fragrans Houtt. | [15] |

| 19 | Electuarium bened. lax. | Achillea millefolium L., Acorus calamus L., Alpinia galanga (L.) Willd., Apium graveolens L., Asparagus officinalis L., Athamanta turbith (L.) Brot., Carum carvi L., Convolvulus scammonia L., Crocus spp. or Crocus sativus L., Dianthus Caryophyllus L., Elettaria cardamomum (L.) Maton, Euphorbia esula L., Foeniculum vulgare Mill., Iris tuberosa L., Lavandula dentata L., Myristica fragrans Houtt., Piper longum L., Rosa spp., Ruscus aculeatus L., Saxifraga spp., Zingiber officinale Roscoe | [16] |

| 21 | Conserva Boragina. | Borago officinalis L. | [17,18] |

| 23 | Pilulae Aloe. lota. | Aloe spp., Agaricus bisporus (J.E. Lange) Imbach or Agaricus campestris L., Rosa spp. | [10,11,19] |

| 24 | Unguentum Artanita | Aloe spp., Capparis spinosa L., Citrullus colocynthis (L.) Schrad., Commiphora myrrha (Nees) Engl., Convolvulus scammonia L., Cyclamen hederifolium Aiton, Daphne mezereum L., Dryopteris filix-mas (L.) Schott, Ecballium elaterium (L.) A. Rich., Euphorbia spp., Ferula persica Willd., Iris tuberosa L., Lavandula dentata L., Matricaria chamomilla L., Piper nigrum L., Polypodium vulgare L., Prunus dulcis (Mill.) D.A. Webb, Sambucus ebulus L., Tamarix gallica L., Vitis vinifera L., Zingiber officinale Roscoe | [20] |

| 26 | Oleum Sup. hord. | Hordeum vulgare L. | [21] |

| 27 | Oxymel Scyll. | Drimia maritima (L.) Stearn | [22] |

| 28 | Syrupus rosatus solutus cum fumaria | Fumaria officinalis L., Rosa spp. | [8] |

| 29 | Oleum Spica. | Lavandula dentata L., Sesamum indicum L. | [23] |

| 30 | Syrupus d. Pomis.s. | Malus domestica (Suckow) Borkh., Prunus dulcis (Mill.) D.A. Webb | [9] |

| 31 | Oleum Mastyc. | Pistacia lentiscus L. | [24] |

| 32 | Syrupus de Mÿrtio | Myrtus communis L. | [9] |

| 33 | Syrupus d. Duab. rad. | Foeniculum vulgare Mill., Petroselinum crispum (Mill.) Fuss | [25] |

| 34 | Oleum Absinthÿ | Artemisia absinthium L. | [26] |

| 35 | Syrupus heder. terres. | Glechoma hederacea L., Rosa spp. | [27] |

| 36 | Oleum Lil. alb. q.pl. | Lilium candidum L. | [28] |

| 41 | Electuarium Diaccatol. | Citrullus colocynthis (L.) Schrad. | [29] |

| 44 | Unguentum Citrini | Boswellia serrata Roxb. ex Colebr., Citrus medica L., Cinnamomum camphora (L.) J. Presl | [30] |

| 45 | Trochiscus d. Cappar. | Acorus calamus L., Agrimonia eupatoria L., Aristolochia rotunda L., Asplenium scolopendrum L., Capparis spinosa L., Clinopodium nepeta subsp. glandulosum (Req.) Govaerts, Cyperus esculentus L., Dorema ammoniacum D. Don, Nigella damascena L., Prunus dulcis (Miller) D.A. Webb, Ruta graveolens L., Vitex agnus-castus L. | [9] |

| 46 | Pilulae Fetid. | Narthex asafoetida Falc. ex Lindl. | [31] |

| 48 | Electuarium Diascord. | Achillea millefolium L., Angelica spp., Centaurea benedicta (L.) L., Galega officinalis L., Potentilla erecta (L.) Raeusch., Ruta graveolens L., Sambucus nigra L., Scorzonera spp., Teucrium scordium L. | [32,33] |

| 50 | Diatrium. santal. | Acacia senegal (L.) Willd., Astragalus bustillosii Clos, Cichorium endivia L., Cucumis melo L., Glycyrrhiza glabra L., Portulaca oleracea L., Pterocarpus santalinus L.f., Rosa spp., Rhaponticum scariosum Lam., Santalum album L., Viola spp. | [9] |

| 51 | Trochiscus de Mirra | Artemisia absinthium L., Commiphora myrrha (Nees) Engl., Cuminum cynimum L., Lupinus albus L., Rubia tinctorum L. | [9] |

| 53 | Oleum Mitridat. d. | Different species, exact recipe not yet known | |

| 54 | Electuarium d. Bac. laur. | Acorus calamus L., Carum carvi L., Cuminum cyminum L., Laurus nobilis L., Nigella sativa L., Origanum vulgare L., Piper longum L., Piper nigrum L., Prunus dulcis (Miller) D.A. Webb, Ruta graveolens L. | [9] |

| 55 | Opiatus poter. | Papaver somniferum L., Veronica spp | [34] |

| 57 | Trochiscus Aland. | Citrullus colocynthis (L.) Schrad. | [9] |

| 60 | Extractus Vissi. querc. | Loranthus europaeus Jacq. | [35] |

| 61 | Unguentum Dialthee sub. | Althaea officinalis L., Larix spp. or Pinus spp. or Picea spp. (turpentine), Larix spp. or Pinus spp. or Picea spp. (rosin), Linum usitatissimum L., Trigonella foenum-graecum L. | [36,37] |

| 62 | Reb. Sambuc. | Sambucus nigra L. | [38] |

| 64 | Conserva Absinth. | Artemisia absinthium L. | [39,40] |

| 68 | Unguentum Diagridium | Convolvulus scammonia L. | Not Found |

| 69 | Pilulae de Cinoglo. | Boswellia serrata Roxb. ex Colebr., Commiphora myrrha (Nees) Engl., Crocus spp. or Crocus sativus L., Cynoglossum officinale L., Hyoscyamus niger L., Papaver somniferum L., Viola spp. | [9] |

| 75 | Extractus haed. terrest. | Glechoma hederacea L. | [41] |

| 76 | Unguentum Lapat. | Cinnamomum camphora (L.) J. Presl, Rosa spp., Rumex conglomeratus Murray, Viola spp. | [10,11] |

| 78 | Emplastrum crustae panis m. | Mentha spp., Pistacia lentiscus L., Pterocarpus santalinus L.f., Santalum album L., Triticum aestivum L. subsp. aestivum, Vitis vinifera L. | [9] |

| 79 | Roab. Sambuc. | Sambucus nigra L. | [38] |

| 80 | Electuarium d. Bac. laur. | Acorus calamus L., Carum carvi L., Cuminum cyminum L., Laurus nobilis L., Nigella sativa L., Origanum vulgare L., Piper longum L., Piper nigrum L., Prunus dulcis (Miller) D.A. Webb, Ruta graveolens L. | [9] |

| 81 | Pilulae de Amon. q. | Aloe spp., Commiphora myrrha (Nees) Engl., Convolvulus scammonia L., Dorema ammoniacum D. Don, Ferula gummosa Boiss., Glycyrrhiza glabra L., Pistacia terebinthus L. | [42] |

| 82 | Pulvis hermodac. | Iris tuberosa L. | [43] |

| 84 | Conserva Rosar. | Rosa spp. | [9] |

| 86 | Pilulae Masticin. | Aloe perryi Baker, Pistacia lentiscus L., Rosa spp. | [44] |

| 87 | Extractus haed. terrest. | Glechoma hederacea L. | [41] |

| 92 | Syrupus Absynthii | Artemisia absinthium L. | [45,46] |

| 93 | Mel. ros. sol. com. | Rosa spp. | [10,11] |

| 94 | Syrupus Cichor. Com. Reub. Gul. -n. | Cichorium intybus L., Rheum officinale L. | [47,48] |

| 95 | Oleum Lil. alb. | Lilium candidum L. | [28] |

| 96 | Syrupus d. Artemisie q.p. | Artemisia spp., Asarum europaeum L., Centaurium erythraea Rafn, Cinnamomum verum J. Presl, Foeniculum vulgare Mill., Juniperus communis L., Juniperus sabina L., Lavandula dentata L., Ligustrum vulgare L., Mentha pulegium L., Origanum dictamnus L., Origanum majorana L., Origanum vulgare L., Petroselinum crispum (Mill.) Fuss, Portulaca oleracea L., Ruta graveolens L. | [13,19] |

| 97 | Syrupus Betton. | Stachys officinalis (L.) Trevisan | [9] |

| 98 | Syrupus Althee. fernet. | Althaea officinalis L. | [9] |

| 99 | Syrupus d. s. Betton. | Stachys officinalis (L.) Trevisan | [9] |

| 100 | Syrupus roxato | Rosa spp. | [10,11] |