The Essential Oil-Bearing Plants in the United Arab Emirates (UAE): An Overview

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Study Location

Weather Conditions and Soil Analysis

3. Data Collection Methodologies

4. Results and Discussions

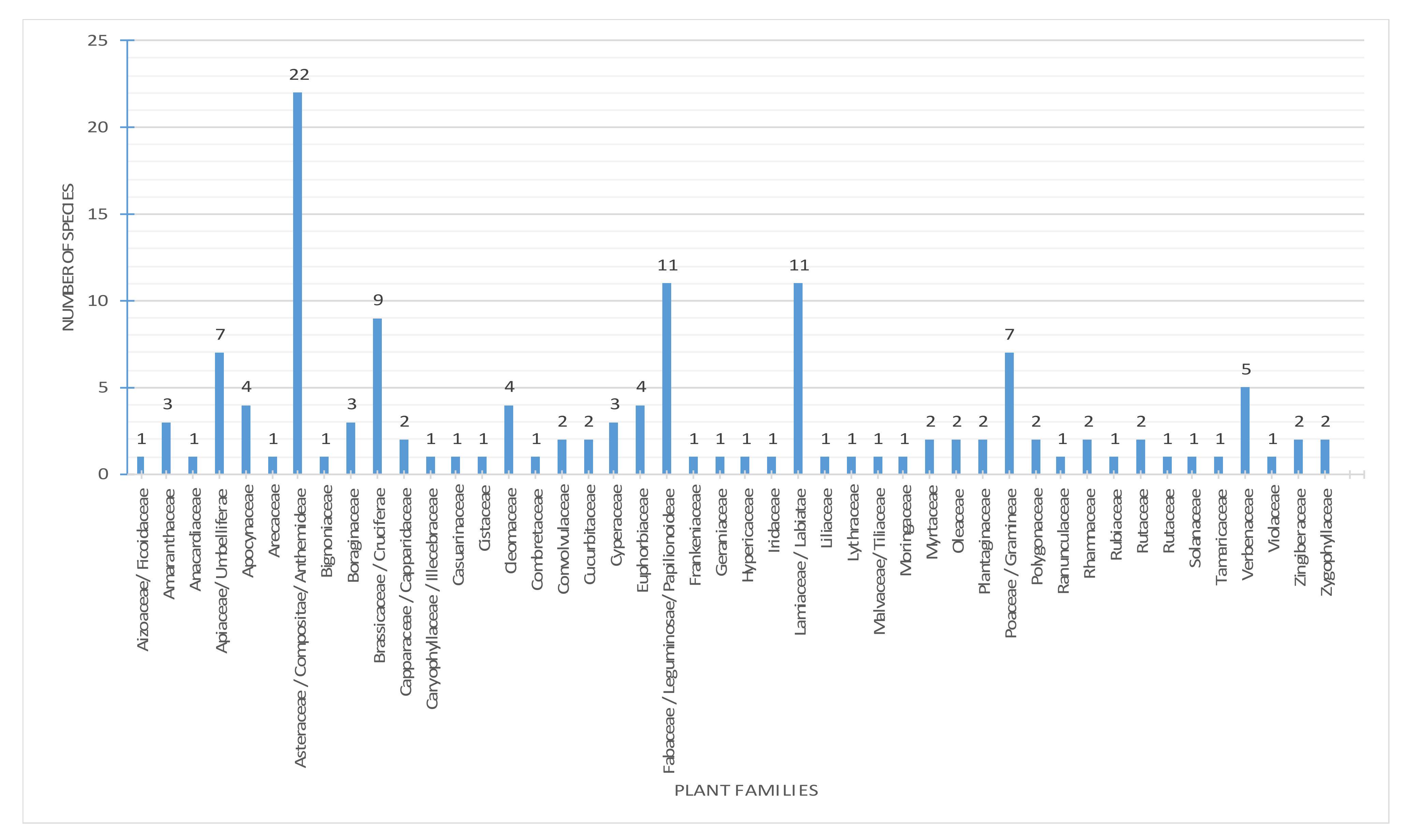

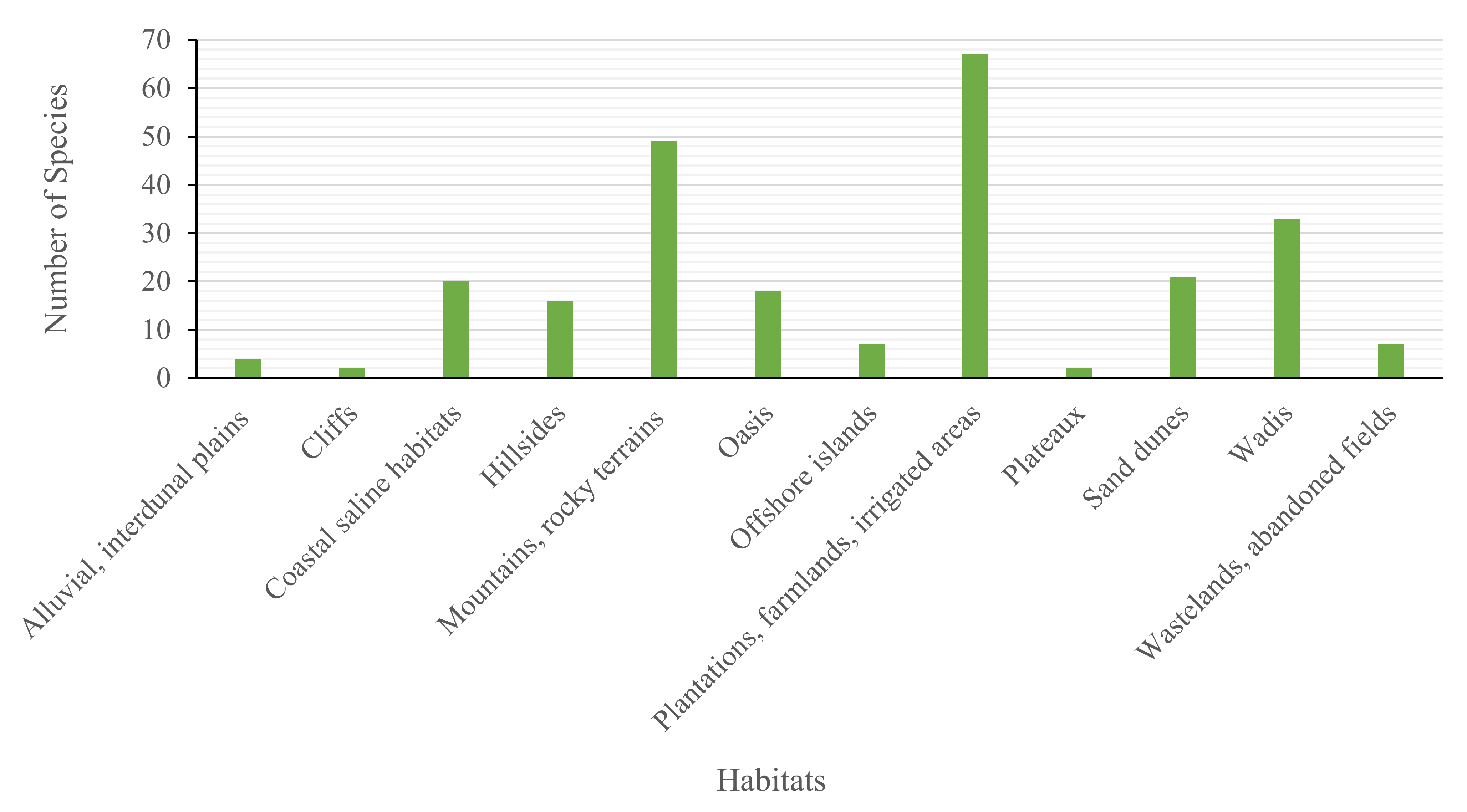

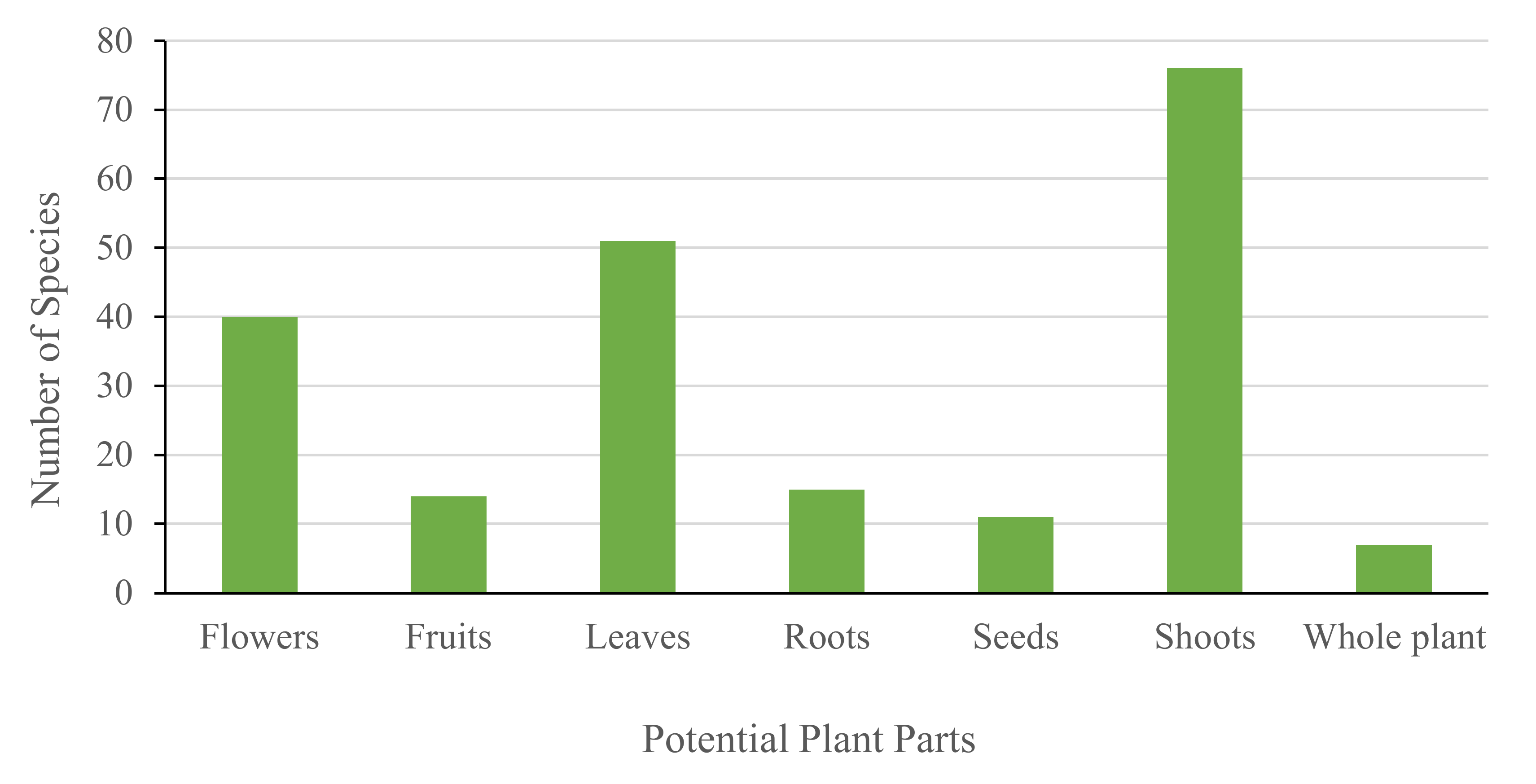

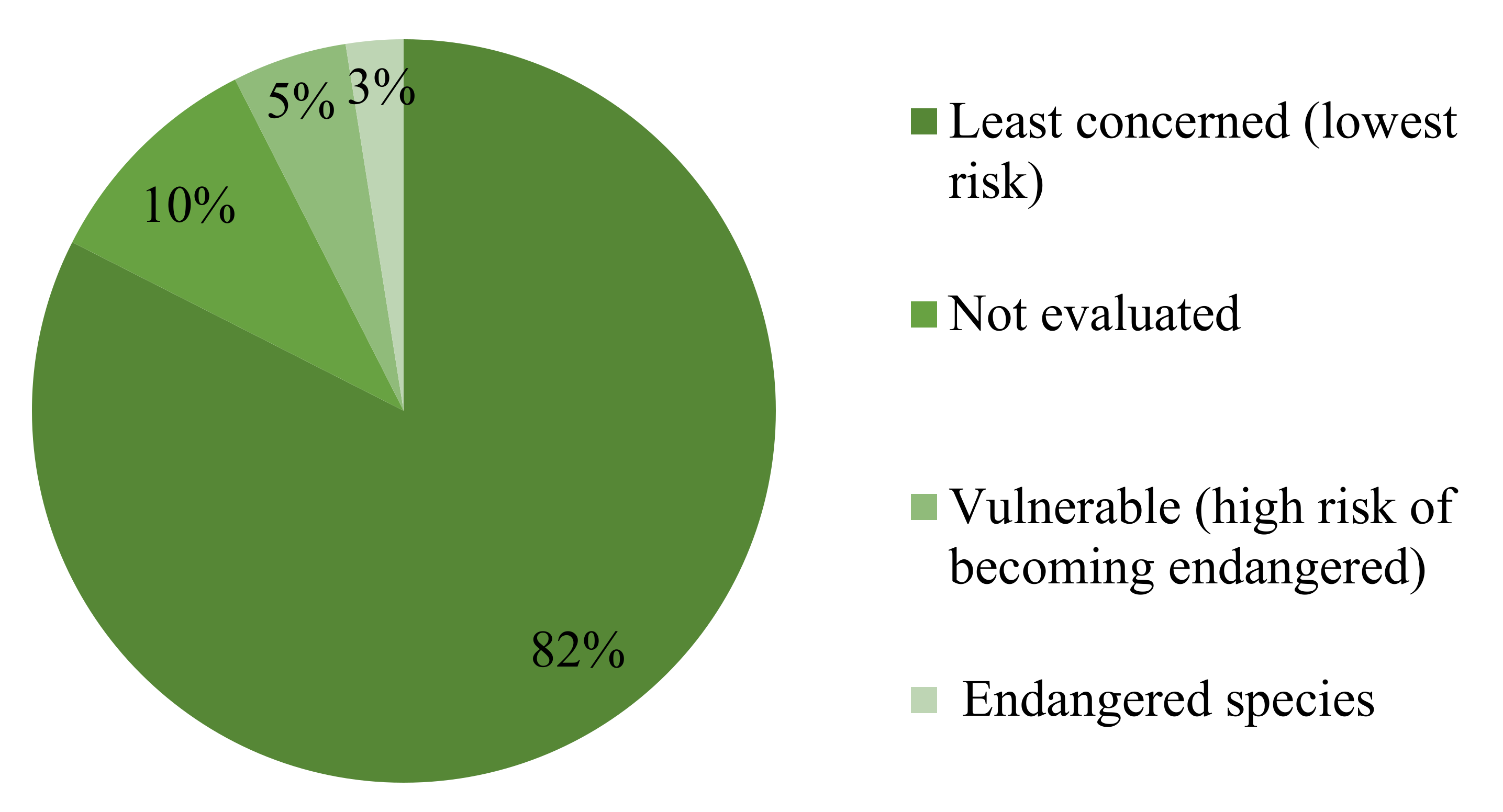

4.1. A Comprehensive Overview

4.2. A Detailed Overview

4.3. List of Abbreviations

- Botanical Name: Syn. “Synonyms”; Eng. “English”; Arb. “Arabic”.

- Form: Vine “V”; Grass “G”; Weed “W”; Forb “F”; Herb “H”; Shrub “S”; Tree “T”.

- Life Form: Geophyte “Ge”; Phanerophyte “Ph”; Chamaephyte “Ch”; Hemicryptophyte “He”; Therophyte “Th”; Cryptophyte “Cr”; Neophyte “Na”.

- Life Cycle: Annual “A”; Biennial “B”; Perennial “P”.

- Economic Value: Medicine and/or Folk Medicine “Med”; Food “Fod”; Nutrition “Nutr”; Food Preservation “FPre”; Flavoring “Flav”; Food Aroma “FArom”; Forage “Forg”; Aromatic “Arom”; Essential Oils “EOs”; Cosmetic “Cosm”; Biofuel “Biof”; Fuel “Fuel”; Cleaning and Hygiene “Clea”; Insecticides “Insec”; Ecological “Eco”; Landscaping “Lands”; Other “Oth”: (Dye, Constructions, Household items, Cushions, Fibers, Sponges, Tobacco, Honey Production, Soil Amendment).

- Folk Medicine:

- Emirates: Abu Dhabi “AD”; Dubai “Du”; Sharjah “S”; Fujairah “F”; Ajman “A”; Ras Al Khaimah “RAK”; Umm Al Quwain “UAQ”.

- Important Locations: Al Ain “Ain”; Khor Kalba “K”; Khor Fakkan “KF”; Hajar Mountains “HM”; Ru’us Al-Jibal “RA”; Jebel Hafit “JH”; Wadi Jeema”J”; Hatta “H”; Wadi Lakayyam “WL”; Along the Country “AC”; Country Center “CC”; East Emirates “EE”; North Emirates “NE”; Coasts of North Emirates “CN”; Eastern Coast “EC”; Western coast “WC”; Scattered Locations “SL”

- Soil: Sand “San”; Silt “Sil”; Rocky or Gravel “Roc”; Saline “Sal”.

- Habitats: Oasis “Oas”; Sand Dunes “Dun”; Coasts “Cos”; Roadsides “Rod”; Offshore Islands “Off”; Inland Water Habitats “Wat”; Plantations and Farmlands and Irrigated Lands “Plat”; Hillsides “Hil”; Disturbed Sites “DS”; Alluvial and Interdunal Plains “Apl”; Wadis “Wad”; Gardens “Gar”; Fallow Fields and Plains “FF”; Cliffs “Cli”; Mountains and Rocky terrains “Mou”; Plateaux “PX”; Wastelands and Abandoned Fields “AF”; Urban areas “Urb”.

- Flowering: Months’ abbreviations will be used.

- Wildlife Status: Fairly common and locally abundant “FC”; Common and widespread locally “CO”; Not common “NC”; Rare and vulnerable “RA”; Not evaluated “NE”; Cultivated Plant “C”.

- Plant Part: Potential for EOs (Roots “R”; Rhizomes “Rz”; Tuber “Tu”; Leaves “L”; Stems and twigs “St”; Pods “Pd”; Buds “Bd”; Bulbs “Bl”; Bark “Bk”; Flowers “Fl”; inflorescences “IF”; Shoots and Aerial parts “Sh”; Fruits “Fr”; Seeds “Se”; Whole Plant “W”).

- Physical Properties: EOs physical characteristics (Color/Odor) Plant part + extraction method.

- Yield (%): EO yield (%, v/w of dry weight). Supported with plant part and extraction method

- Isolation Method: EO extraction method including:

- Main Chemical Groups/Components:

- Biological Activity: [EO Biological Activity] (Activity Details) Plant part + extraction method.

- General Notes: The use of “!” means information uncertainty.

4.4. Phytochemicals and Biological Activities from UAE Based Plants

5. Obstacles and Difficulties

6. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baser, K.H.C.; Buchbauer, G. Handbook of Essential Oils: Science, Technology, and Applications; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bakkali, F.; Averbeck, S.; Averbeck, D.; Idaomar, M. Biological effects of essential oils–A review. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2008, 46, 446–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahin, S.M.; Salem, M.A. The innovative perspective of arid land agriculture: Essential oil-bearing plants as factories for a healthy and sustainable future. In Proceedings of the The Annual Meeting of Crop Science Society of America (CSSA), Synergy in Science: Partnering for Solutions, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 15–18 November 2015; ACSESS Digital Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Shahin, S.M.; Kurup, S.; Cheruth, J.; Salem, M. Chemical composition of Cleome amblyocarpa Barr. & Murb. essential oil under different irrigation levels in sandy soils with antioxidant activity. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants 2018, 21, 1235–1256. [Google Scholar]

- Al Yousuf, M.H.; Bashir, A.K.; Veres, K.; Dobos, Á.; Nagy, G.; Máthé, I.; Blunden, G.; Vera, J.R. Essential oil of Haplophyllum tuberculatum (Forssk.) A. Juss. from the United Arab Emirates. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2005, 17, 519–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Yousuf, M.H.; Bashir, A.K.; Dobos, Á.; Veres, K.; Nagy, G.; Máthé, I.; Blunden, G. The composition of the essential oil of Teucrium stocksianum from the United Arab Emirates. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2002, 14, 47–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Yousuf, M.; Bashir, A.; Veres, K.; Dobos, A.; Nagy, G.; Mathe, I.; Blunden, G. Essential oil of Pulicaria glutinosa Jaub. from the United Arab Emirates. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2001, 13, 454–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senthilkumar, A.; Thangamani, A.; Karthishwaran, K.; Cheruth, A.J. Essential oil from the seeds of Moringa peregrina: Chemical composition and antioxidant potential. South Afr. J. Bot. 2020, 129, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajaj, R.; Shahin, S.; Salem, M. The challenges of climate change and food security in the United Arab Emirates (UAE): From deep understanding to quick actions. J. Curr. Nutr. Food Sci. 2018, 14, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahin, S.M.; Salem, M.A. Review future concerns on Irrigation requirements of date palm tree in the United Arab Emirates (UAE): Call for quick actions. In Proceedings of the 5th International Date Palm Conference, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 16–18 March 2014; pp. 255–262, ISBN 978-9948-22-868-4. [Google Scholar]

- Ajaj, R.; Shahin, S.; Kurup, S.; Cheruth, J.; Salem, M.A. Elemental fingerprint of agriculture soils of eastern region of the Arabian desert by ICP-OES with GIS mapping. J. Curr. Environ. Eng. 2018, 5, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahin, S.M.; Salem, M.A. The challenges of water scarcity and the future of food security in the United Arab Emirates (UAE). Nat. Res. Cons. 2015, 3, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M.; Murad, A.; Chowdhury, R. Evaluation of groundwater quality in the eastern district of Abu Dhabi Emirate: UAE. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2017, 98, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batanouny, K.H. Current knowledge of plant ecology in the Arab Gulf countries. Catena 1987, 14, 291–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Western, R.A. The Flora of the United Arab Emirates: An Introduction; United Arab Emirates University Publications: Al Ain, United Arab Emirates, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Tanira, M.O.M.; Bashir, A.K.; Dib, R.; Goodwin, C.S.; Wasfi, I.A.; Banna, N.R. Antimicrobial and phytochemical screening of medicinal plants of the United Arab Emirates. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1994, 41, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasfi, I.A.; Bashir, A.K.; Abdalla, A.A.; Banna, N.R.; Tanira, M.O.M. Antiinflammatory activity of some medicinal plants of the United Arab Emirates. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1995, 33, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, F.M. Weeds in the United Arab Emirates; United Arab Emirates University Publications: Al Ain, United Arab Emirates, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Emirates Natural History Group. Tribulus: Bulletin of the Emirates Natural History Group; AI lttihad Press and Printing Corporation: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 1997; Volume 7, pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Böer, B.; Chaudhary, S.A. New Records for the Flora of the United Arab Emirates. Willdenowia 1999, 29, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jongbloed, M.; Feulner, G.; Böer, B.; Western, A.R. The Comprehensive Guide to the Wild Flowers of the United Arab Emirates; Environmental Research and Wildlife Development Agency: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, G.; Sakkir, S. The Vascular Plants of Abu Dhabi Emirate; Environmental Research and Wildlife Development Agency: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Aspinall, S. The Emirates: A Natural History; Trident Press Ltd.: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- ZCHRTM (Zayed complex for Herbal Research and Traditional Medicine). In Encyclopedia of Medicinal Plants of UAE; General Authority for Health Services for the Emirate of Abu Dhabi: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2005; Volume 1.

- Handa, S.S.; Rakesh, D.D.; Vasisht, K. Compendium of Medicinal and Aromatic Plants: Asia. ICS UNIDO Asia 2006, 2, 305. [Google Scholar]

- Karim, F.M.; Dakheel, A.J. Salt-Tolerant Plants of the United Arab Emirates; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Mousa, M.; Fawzi, N. Vegetation analysis of Wadi Al Ain, United Arab Emirates. Acad. J. Plant Sci. 2009, 2, 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Sakkir, S.; Kabshawi, M.; Mehairbi, M. Medicinal plants diversity and their conservation status in the United Arab Emirates (UAE). J. Med. Plant Res. 2012, 6, 1304–1322. [Google Scholar]

- Fawzi, N.; Ksiksi, T. Plant species diversity within an important United Arab Emirates ecosystem. Rev. Écol. 2013, 67, 25–36. [Google Scholar]

- Hurriez, S.H. Folklore and Folklife in the United Arab Emirates; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Feulner, G.R. The Olive Highlands: A unique“ island” of biodiversity within the Hajar Mountains of the United Arab Emirates. Tribulus 2014, 22, 9–35. [Google Scholar]

- El-Keblawy, A.A.; Khedr, A.H.A.; Khafaga, T.A. Mountainous Landscape Vegetation and Species Composition at Wadi Helo: A Protected area in Hajar Mountains, UAE. Arid Land Res. Manag. 2016, 30, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EAD (Environmental Agency of Abu Dhabi). Jewels of the UAE. 2017. Available online: http://www.arkive.org/uae/en/plants-and-algae (accessed on 1 April 2018).

- EAD (Environmental Agency of Abu Dhabi). Grasses, Sedges and Rushes of the UAE; EAD (Environmental Agency of Abu Dhabi): Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2019.

- Magwa, M.L.; Gundidza, M.; Gweru, N.; Humphrey, G. Chemical composition and biological activities of essential oil from the leaves of Sesuvium portulacastrum. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2006, 103, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastav, S.; Singh, P.; Mishra, G.; Jha, K.K.; Khosa, R.L. Achyranthes aspera—An important medicinal plant: A review. J. Nat. Prod. Plant Res. 2011, 1, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Samejo, M.Q.; Memon, S.; Bhanger, M.I.; Khan, K.M. Chemical compositions of the essential oil of Aerva javanica leaves and stems. Pak. J. Anal. Environ. Chem. 2012, 13, 48–52. [Google Scholar]

- Samejo, M.Q.; Memon, S.; Bhanger, M.I.; Khan, K.M. Comparison of chemical composition of Aerva javanica seed essential oils obtained by different extraction methods. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 26, 757–760. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Khomarlou, N.; Aberoomand-Azar, P.; Lashgari, A.P.; Tebyanian, H.; Hakakian, A.; Ranjbar, R.; Ayatollahi, S.A. Essential oil composition and in vitro antibacterial activity of Chenopodium album subsp. striatum. Acta Biol. Hung. 2018, 69, 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghizadeh, S.F.; Davarynejad, G.; Asili, J.; Riahi-Zanjani, B.; Nemati, S.H.; Karimi, G. Chemical composition, antibacterial, antioxidant and cytotoxic evaluation of the essential oil from pistachio (Pistacia khinjuk) hull. Microb. Pathog. 2018, 124, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Snafi, A.E. Chemical constituents and pharmacological activities of Ammi majus and Ammi visnaga. A review. Int. J. Pharm. Ind. Res. 2013, 3, 257–265. [Google Scholar]

- Kazemi, M. Phenolic profile, antioxidant capacity and anti-inflammatory activity of Anethum graveolens L. essential oil. Nat. Prod. Res. 2015, 29, 551–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahabipour, S.; Firuzi, O.; Asadollahi, M.; Faghihmirzaei, E.; Javidnia, K. Essential oil composition and cytotoxic activity of Ducrosia anethifolia and Ducrosia flabellifolia from Iran. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2013, 25, 160–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oran, S.A.; Al-Eisawi, D.M. Medicinal plants in the high mountains of northern Jordan. Int. J. Biodiv. Cons. 2014, 6, 436–443. [Google Scholar]

- Askari, F.; Sefidkon, F.; Teymouri, M.; Yousef, N. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of the essential oil of Pimpinella puberula (DC.) Boiss. J. Agr. Sci. Tech. 2009, 11, 431–438. [Google Scholar]

- Radulović, N.S.; Mladenović, M.Z.; Stojanović-Radić, Z.Z. Synthesis of small libraries of natural products: New esters of long-chain alcohols from the essential oil of Scandix pecten-veneris L. (Apiaceae). Flavour Fragr. J. 2014, 29, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, N.; Khan, M.R.; Shabbir, M. Antioxidant activity, total phenolic and total flavonoid contents of whole plant extracts Torilis leptophylla L. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2012, 12, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derwich, E.; Benziane, Z.; Boukir, A. Antibacterial activity and chemical composition of the essential oil from flowers of Nerium oleander. Electron. J. Environ. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 9, 1074–1084. [Google Scholar]

- Lawal, O.A.; Ogunwande, I.A.; Opoku, A.R. Chemical composition of essential oils of Plumeria rubra L. grown in Nigeria. Eur. J. Med. Plants. 2015, 6, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rowaily, S.L.; Abd-ElGawad, A.M.; Assaeed, A.M.; Elgamal, A.M.; Gendy, A.E.N.G.E.; Mohamed, T.A.; Dar, B.A.; Mohamed, T.K.; Elshamy, A.I. Essential Oil of Calotropis procera: Comparative Chemical Profiles, Antimicrobial Activity, and Allelopathic Potential on Weeds. Molecules 2020, 25, 5203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atghaei, M.; Sefidkon, F.; Darini, A.; Sadeghzadeh Hemayati, S.; Abdossi, V. Essential Oil Content and Composition of the Spathe in Some Date Palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) Varieties in Iran. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants 2020, 23, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zebarjad, Z.; Farjam, M.H. Evaluation of antimicrobial activity of essential oils from different parts of Anthemis odontostephana Boiss. Var. odontostephana. Int. J. Pharm. Phytochem. Res. 2015, 7, 579–584. [Google Scholar]

- Tabari, M.A.; Youssefi, M.R.; Benelli, G. Eco-friendly control of the poultry red mite, Dermanyssus gallinae (Dermanyssidae), using the α-thujone-rich essential oil of Artemisia sieberi (Asteraceae): Toxic and repellent potential. Parasitol. Res. 2017, 116, 1545–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ercetin, T.; Senol, F.S.; Orhan, I.E.; Toker, G. Comparative assessment of antioxidant and cholinesterase inhibitory properties of the marigold extracts from Calendula arvensis L. and Calendula officinalis L. Ind. Crops Prod. 2012, 36, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghi, G.; Arshi, R.; Ghazian, F.; Hosseini, H. Chemical composition of essential oil of aerial parts of Cichorium intybus L. from Iran. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants 2012, 15, 213–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.R.; Thabit, R.A.; Wang, W.; Shi, H.W.; Shi, Y.H.; Le, G.W. Analysis and comparison of the essential oil in Conyza bonariensis grown in Yemen and China. Prog. Mod. Biomed. 2013, 36, 7034–7038. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, K.M.; Kim, G.H. Constituents of the Essential Oil from Eclipta prostrata L. Prev. Nutr. Food Sci. 2009, 14, 168–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rustaiyan, A.; Azar, P.A.; Moradalizadeh, M.; Masoudi, S.; Ameri, N. Volatile constituents of three compositae herbs: Anthemis altissima L. var. altissima Conyza Canadensis (L.) Cronq. and Grantina aucheri Boiss. Growing Wild in Iran. J. Essen. Oil Res. 2004, 16, 579–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mahrezi, J.A.; Al-Sabahi, J.N.; Akhtar, M.S.; Selim, D.; Weli, A.M. Essential oil composition and antimicrobial screening of Launaea nudicaulis grown in Oman. Int. J Pharm. Sci. Res. 2011, 2, 3166. [Google Scholar]

- Saleem, M.; Parveen, S.; Riaz, N.; Tahir, M.N.; Ashraf, M.; Afzal, I.; Jabbar, A. New bioactive natural products from Launaea nudicaulis. Phytochem. Lett. 2012, 5, 793–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, N.A. Chemical constituents of essential oil from flowers of Matricaria aurea grown in Saudi Arabia. Indian J. Drugs 2014, 2, 164–168. [Google Scholar]

- Karam, T.K.; Ortega, S.; Nakamura, T.U.; Auzély-Velty, R.; Nakamura, C.V. Development of chitosan nanocapsules containing essential oil of Matricaria chamomilla L. for the treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 162, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, A.; Mousa, M. Merits of anti-cancer plants from the Arabian Gulf region. Can. Ther. 2007, 5, 55–66. [Google Scholar]

- Suliman, F.E.O.; Fatope, M.O.; Al-Saidi, S.H.; Al-Kindy, S.M.; Marwah, R.G. Composition and antimicrobial activity of the essential oil of Pluchea arabica from Oman. Flavour Fragr. J. 2006, 21, 469–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Ghorab, A.H.; Ramadan, M.M.; El-Moez, S.I.A.; Soliman, A.M.M. Essential oil, antioxidant, antimicrobial and anticancer activities of Egyptian Pluchea dioscoridis extract. Res. J. Pharm. Biol. Chem. Sci. 2015, 6, 1255–1265. [Google Scholar]

- Goyal, P.K.; Aggarwal, R.R. A Review on Phytochemical and biological investigation of plant genus Pluchea. Indo Am. J. Pharm. Res. 2013, 3, 3000–3007. [Google Scholar]

- Demirci, B.; Baser, K.H.; Duman, H. The essential oil composition of Gnaphalium luteo-album. Chem. Nat. Comp. 2009, 45, 446–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djermane, N.; Gherraf, N.; Arhad, R.; Zellagui, A.; Rebbas, K. Chemical composition, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of the essential oil of Pulicaria arabica (L.) Cass. Pharm. Lett. 2016, 8, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hajj, N.Q.M.; Wang, H.; Gasmalla, M.A.; Ma, C.; Thabit, R.; Rahman, M.R.T.; Tang, Y. Chemical composition and antioxidant activity of the essential oil of Pulicaria inuloides. J. Food Nut. Res. 2014, 2, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hajj, N.Q.M.; Ma, C.; Thabit, R.; Gasmalla, M.A.; Musa, A.; Aboshora, W.; Wang, H. Chemical composition of essential oil and mineral contents of Pulicaria inuloides. J. Acad. Ind. Res. 2014, 2, 675–678. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hajj, N.Q.M.; Algabr, M.N.; Omar, K.A.; Wang, H. Anticancer, Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Activities of the Essential Oils of Some Aromatic Medicinal Plants (Pulicaria inuloides-Asteraceae). J. Food Nutr. Res. 2017, 5, 490–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boumaraf, M.; Mekkiou, R.; Benyahia, S.; Chalchat, J.C.; Chalard, P.; Benayache, F.; Benayache, S. Essential oil composition of Pulicaria undulata (L.) DC. (Asteraceae) growing in Algeria. Int. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. Res. 2016, 8, 746–749. [Google Scholar]

- Demirci, B.; Yusufoglu, H.S.; Tabanca, N.; Temel, H.E.; Bernier, U.R.; Agramonte, N.M.; Alqasoumi, S.I.; Al-Rehaily, A.J.; Başer, K.H.C.; Demirci, F. Rhanterium epapposum Oliv. essential oil: Chemical composition and antimicrobial, insect-repellent and anticholinesterase activities. Saudi Pharm. J. 2017, 25, 703–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basaid, K.; Bouharroud, R.; Furze, J.N.; Benjlil, H.; de Oliveira, A.L.; Chebli, B. Biopesticidal value of Senecio glaucus subsp. coronopifolius essential oil against pathogenic fungi, nematodes, and mites. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 27, 3082–3090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belhattab, R.; Amor, L.; Barroso, J.G.; Pedro, L.G.; Figueiredo, A.C. Essential oil from Artemisia herba-alba Asso grown wild in Algeria: Variability assessment and comparison with an updated literature survey. Arab. J. Chem. 2014, 7, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtar, M.M.; Shaban, H.M.; Hegazy, M.E.A.F.; Ali, S.S. Evaluating the potential cancer chemopreventive efficacy of two different solvent extracts of Seriphidium herba-alba in vitro. Bull. Fac. Pharm. Cairo Univ. 2017, 55, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, R.S.; Padalia, R.C.; Chauhan, A.; Sundaresan, V. Essential oil composition of Sphagneticola trilobata (L.) Pruski from India. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2014, 26, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padin, S.B.; Fuse, C.; Urrutia, M.I.; Dal Bello, G.M. Toxicity and repellency of nine medicinal plants against Tribolium castaneum in stored wheat. Bull. Insectol. 2013, 66, 45–49. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Mazroa, S.A.; Al-Wahaibi, L.H.; Mousa, A.A.; Al-Khathlan, H.Z. Essential oil of some seasonal flowering plants grown in Saudi Arabia. Arab. J. Chem. 2015, 8, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeedi, M.; Morteza-Semnani, K. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of the essential oil of Heliotropium europaeum. Chem. Nat. Comp. 2009, 45, 98–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Ibrahim, M.; Khalid, K. Investigation of essential oil constituents isolated from Trichodesma africanum (L.) grow wild in Egypt. Res. J. Med. Plant 2015, 9, 248–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kamali, H.; Sani, T.A.; Feyzi, P.; Mohammadi, A. Chemical composition and antioxidant activity from essential oil of Capsella bursa-pastoris. Int. J. Pharmtech. Res. 2015, 8, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadzadeh Moghaddam, M.; Elhamirad, A.H.; Shariatifar, N.; Saidee Asl, M.R.; Armin, M. Anti-bacterial effects of essential oil of Cardaria draba against bacterial food borne pathogens. Horizon Med. Sci. 2014, 19, 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Prabhakar, K.R.; Srinivasan, K.K.; Rao, P.G. Chemical investigation, anti-inflammatory and wound healing properties of Coronopus didymus. Pharm. Boil. 2002, 40, 490–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, A.W.M.; Taha, S.S. Main sulphur content in essential oil of Eruca Sativa as affected by nano iron and nano zinc mixed with organic manure. Agriculture 2018, 64, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Shabasy, A. Survey on medicinal plants in the flora of Jizan Region, Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Bot. Stud. 2016, 2, 38–59. [Google Scholar]

- Rad, J.S.; Alfatemi, M.H.; Rad, M.S.; Sen, D.J. Phytochemical and antimicrobial evaluation of the essential oils and antioxidant activity of aqueous extracts from flower and stem of Sinapis arvensis L. Open J. Adv. Drug Deliv. 2013, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Qudah, M.A.; Abu Zarga, M.H. Chemical composition of essential oils from aerial parts of Sisymbrium irio from Jordan. J. Chem. 2010, 7, 6–10. [Google Scholar]

- Yousif, F.; Wassel, G.; Boulos, L.; Labib, T.; Mahmoud, K.; El-Hallouty, S.; El-Manawaty, M. Contribution to in vitro screening of Egyptian plants for schistosomicidal activity. Pharm. Biol. 2012, 50, 732–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulisic-Bilusic, T.; Schmöller, I.; Schnäbele, K.; Siracusa, L.; Ruberto, G. The anticarcinogenic potential of essential oil and aqueous infusion from caper (Capparis spinosa L.). Food Chem. 2012, 132, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanović, M.; Mimica-Dukić, N.; Poljački, M.; Boža, P. Erythema multiforme due to contact with weeds: A recurrence after patch testing. Contact Dermat. 2003, 48, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunwande, I.A.; Flamini, G.; Adefuye, A.E.; Lawal, N.O.; Moradeyo, S.; Avoseh, N.O. Chemical compositions of Casuarina equisetifolia L. Eucalyptus toreliana L. and Ficus elastica Roxb. ex Hornem cultivated in Nigeria. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2011, 77, 645–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essien, E.E.; Newby, J.M.; Walker, T.M.; Ogunwande, I.A.; Setzer, W.N.; Ekundayo, O. Essential oil constituents, anticancer and antimicrobial activity of Ficus mucoso and Casuarina equisetifolia leaves. Am. J. Essent. Oil 2016, 4, 1–06. [Google Scholar]

- Javidnia, K.; Nasiri, A.; Miri, R.; Jamalian, A. Composition of the essential oil of Helianthemum kahiricum Del. from Iran. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2007, 19, 52–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahin, S.M.; Kurup, S.; Cheruth, J.; Lennartz, F.; Salem, M. Growth, yield, and physiological responses of Cleome amblyocarpa Barr. & Murb. under varied irrigation levels in sandy soils. J. Food Agric. Environ. 2018, 16, 124–134. [Google Scholar]

- Rassouli, E.; Dadras, O.G.; Bina, E.; Asgarpanah, J. The essential oil composition of Cleome brachycarpa Vahl ex DC. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants 2014, 17, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Gawad, A.M.; El-Amier, Y.A.; Bonanomi, G. Essential oil composition, antioxidant and allelopathic activities of Cleome droserifolia (Forssk.) Delile. Chem. Biodivers. 2018, 15, e1800392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anbazhagi, T.; Kadavul, K.; Suguna, G.; Petrus, A.J.A. Studies on the pharmacognostical and in vitro antioxidant potential of Cleome gynandra Linn. leaves. Nat. Prod. Rad. 2009, 8, 151–157. [Google Scholar]

- Owolabi, M.S.; Lawal, O.A.; Ogunwande, I.A.; Hauser, R.M.; Setzer, W.N. Chemical composition of the leaf essential oil of Terminalia catappa L. growing in Southwestern Nigeria. Am. J. Essent. Oil 2013, 1, 51–54. [Google Scholar]

- Böhme, M.; Pinker, I. Investigation regarding the potential for cultivation of indigenous vegetables in Southeast Asia. Acta Hortic. 2006, 752, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Harbi, N.O. Effect of marjoram extract treatment on the cytological and biochemical changes induced by cyclophosphamide in mice. J. Med. Plant Res. 2011, 5, 5479–5485. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, R.K. Sesquiterpene-rich volatile constituents of Ipomoea obscura (L.) Ker-Gawl. Nat. Prod. Res. 2015, 29, 1935–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernando, L.N.; Grün, I.U. Headspace–SPME analysis of volatiles of the ridge gourd (Luffa acutangula) and bitter gourd (Momordica charantia) flowers. Flavour Fragr. J. 2001, 16, 289–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braca, A.; Siciliano , T.; D’Arrigo, M.; Germanò, M.P. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of Momordica charantia seed essential oil. Fitoterapia 2008, 79, 123–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindarajan, M.; Sivakumar, R.; Rajeswary, M.; Yogalakshmi, K. Chemical composition and larvicidal activity of essential oil from Ocimum basilicum (L.) against Culex tritaeniorhynchus, Aedes albopictus and Anopheles subpictus (Diptera: Culicidae). Exp. Parasitol. 2013, 134, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feizbakhsh, A.; Aghassi, A.; Naeemy, A. Chemical constituents of the essential oils of Cyperus difformis L. and Cyperus arenarius Retz from Iran. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants 2012, 15, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hisham, A.; Rameshkumar, K.B.; Sherwani, N.; Al-Saidi, S.; Al-Kindy, S. The composition and antimicrobial activities of Cyperus conglomeratus, Desmos chinensis var. lawii and Cyathocalyx zeylanicus essential oils. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2012, 7, 663–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Q.P.; Cao, X.M.; Hao, D.L.; Zhang, L.L. Chemical composition, antioxidant, DNA damage protective, cytotoxic and antibacterial activities of Cyperus rotundus rhizomes essential oil against foodborne pathogens. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Q.; Jiang, M.L.; Shao, F.; Ma, G.Q.; Shi, Q.; Liu, R.H. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of the essential oil from Euphorbia helioscopia L. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2020, 15, 1934578X20953249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunlesi, M.; Okiei, W.; Ofor, E.; Osibote, A.E. Analysis of the essential oil from the dried leaves of Euphorbia hirta Linn (Euphorbiaceae), a potential medication for asthma. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2009, 8, 7042–7050. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J.; Dou, J.; Xu, J.; Aisa, H.A. Chemical composition, antimicrobial and antitumor activities of the essential oils and crude extracts of Euphorbia macrorrhiza. Molecules 2012, 17, 5030–5039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, N.; Bachrouch, O.; Sriti, J.; Msaada, K.; Khammassi, S.; Hammami, M.; Selmi, S.; Boushih, E.; Koorani, S.; Abderraba, M.; et al. Fumigant and repellent potentials of Ricinus communis and Mentha pulegium essential oils against Tribolium castaneum and Lasioderma serricorne. Int. J. Food Prop. 2017, 20 (Suppl. S3), S2899–S2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samejo, M.Q.; Memon, S.; Bhanger, M.I.; Khan, K.M. Chemical composition of essential oils from Alhagi maurorum. Chem. Nat. Comp. 2012, 48, 898–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanshahian, M.; Saadatfar, A.; Masoumipour, F. Formulation and characterization of nanoemulsion from Alhagi maurorum essential oil and study of its antimicrobial, antibiofilm, and plasmid curing activity against antibiotic-resistant pathogenic bacteria. J. Environ. Health Sci. Eng. 2020, 18, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabudak, T.; Goren, A.C. Volatile Composition of Trifolium and Medicago Species. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants 2011, 14, 401–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gweru, N.; Gundidza, M.; Magwa, M.L.; Ramalivhana, N.J.; Humphrey, G.; Samie, A.; Mmbengwa, V. Phytochemical composition and biological activities of essential oil of Rhynchosia minima (L) (DC) (Fabaceae). Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2009, 8, 721–724. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, X.; Zhang, C.; Qiu, J.; Wang, L.; Bao, J.; Wang, K.; Han, J. Purification, structural characterization and anticancer activity of the novel polysaccharides from Rhynchosia minima root. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 132, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamed Chitsazan, M.; Bina, E.; Asgarpanah, J. Essential oil composition of the endemic species Tephrosia persica Boiss. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2014, 26, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qudah, M.A.; Al-Ghoul, A.M.; Trawenh, I.N.; Al-Jaber, H.I.; Al Shboul, T.M.; Abu Zarga, M.H.; Abu orabi, S.T. Antioxidant Activity and Chemical Composition of Essential Oils from Jordanian Ononis natrix L. and Ononis sicula Guss. J. Biol. Active Prod. Nat. 2014, 4, 52–61. [Google Scholar]

- Ogunbinu, A.O.; Okeniyi, S.; Flamini, G.; Cioni, P.L.; Ogunwande, I.A.; Babalola, I.T. Essential oil composition of Acacia nilotica Linn., and Acacia albida Delile (Leguminosae) from Nigeria. J. Essen. Oil Res. 2010, 22, 540–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivekanandhan, P.; Venkatesan, R.; Ramkumar, G.; Karthi, S.; Senthil-Nathan, S.; Shivakumar, M.S. Comparative analysis of major mosquito vectors response to seed-derived essential oil and seed pod-derived extract from Acacia nilotica. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2018, 15, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogunwande, I.A.; Matsui, T.; Matsumoto, K.; Shimoda, M.; Kubmarawa, D. Constituents of the essential oil from the leaves of Acacia tortilis (Forsk.) Hayne. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2008, 20, 116–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harzallah-Skhiri, F.; Jannet, H.B.; Hammami, S.; Mighri, Z. Variation of volatile compounds in two Prosopis farcta (Banks et Sol.) Eig.(Fabales, Fabaceae= Leguminosae) populations. Flavour Fragr. J. 2006, 21, 484–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaieb, I. Research on insecticidal plants in Tunisia: Review and discussion of methodological approaches. Tunis. J. Plant Prot. 2011, 6, 109–125. [Google Scholar]

- Ljoljić Bilić, V.; Stabentheiner, E.; Kremer, D.; Dunkić, V.; Grubešić, R.J.; Rodríguez, J.V. Phytochemical and micromorphological characterization of croatian populations of Erodium cicutarium. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2019, 14, 1934578X19856257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morshedloo, M.R.; Ebadi, A.; Maggi, F.; Fattahi, R.; Yazdani, D.; Jafari, M. Chemical characterization of the essential oil compositions from Iranian populations of Hypericum perforatum L. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015, 76, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qudah, M.A.; Saleh, A.M.; Al-Jaber, H.I.; Tashtoush, H.I.; Lahham, J.N.; Zarga, M.H.A.; Orabi, S.T.A. New isoflavones from Gynandriris sisyrinchium and their antioxidant and cytotoxic activities. Fitoterapia 2015, 107, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi-Rad, J.; Hoseini-Alfatemi, S.M.; Sharifi-Rad, M.; Setzer, W.N. Chemical composition, antifungal and antibacterial activities of essential oil from Lallemantia royleana (Benth. In Wall.) Benth. J. Food Saf. 2015, 35, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardaweel, S.K.; Bakchiche, B.; ALSalamat, H.A.; Rezzoug, M.; Gherib, A.; Flamini, G. Chemical composition, antioxidant, antimicrobial and Antiproliferative activities of essential oil of Mentha spicata L.(Lamiaceae) from Algerian Saharan atlas. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2018, 18, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Marzouqi, A.H.; Rao, M.V.; Jobe, B. Comparative evaluation of SFE and steam distillation methods on the yield and composition of essential oil extracted from spearmint (Mentha spicata). J. Liq. Chromatogr. Relat. Technol. 2007, 30, 463–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekker, T.; Ignell, R.; Ghebru, M.; Glinwood, R.; Hopkins, R. Identification of mosquito repellent odours from Ocimum forskolei. Parasites Vectors 2011, 4, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourhosseini, M.; Asgarpanah, J. Essential and fixed oil chemical profiles of Salvia aegyptiaca L. Flowers and seeds. J. Chil. Chem. Soc. 2015, 60, 2747–2748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mirzania, F.; Sarrafi, Y.; Farimani, M.M. Comparison of chemical composition, antifungal antibacterial activities of two populations of Salvia macilenta Boiss. Essential oil. Rec. Nat. Prod. 2018, 12, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajabi, Z.; Ebrahimi, M.; Farajpour, M.; Mirza, M.; Ramshini, H. Compositions and yield variation of essential oils among and within nine Salvia species from various areas of Iran. Ind. Crops Prod. 2014, 61, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zomorodian, K.; Moein, M.; Pakshir, K.; Karami, F.; Sabahi, Z. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activities of the essential oil from Salvia mirzayanii leaves. J. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 22, 770–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flamini, G.; Cioni, P.L.; Morelli, I.; Bader, A. Essential oils of the aerial parts of three Salvia species from Jordan: Salvia lanigera, S. spinosa and S. syriaca. Food Chem. 2007, 100, 732–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozzani, S.; Muselli, A.; Desjobert, J.M.; Bernardini, A.F.; Tomi, F.; Casanova, J. Chemical composition of essential oil of Teucrium polium subsp. capitatum (L.) from Corsica. Flavour Fragr. J. 2005, 20, 436–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabudari, A.; Mahalleh, S.F.R.P. Study of antibacterial effects of Teucrium polium essential oil on Bacillus cereus in cultural laboratory and commercial soup. Carpathian Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 8, 176–183. [Google Scholar]

- Sonboli, A.; Bahadori, M.B.; Dehghan, H.; Aarabi, L.; Savehdroudi, P.; Nekuei, M.; Pournaghi, N.; Mirzania, F. Chemotaxonomic Importance of the Essential-Oil Composition in Two Subspecies of Teucrium stocksianum Boiss. from Iran. Chem. Biodivers. 2013, 10, 687–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misaghi, A.; Basti, A.A. Effects of Zataria multiflora Boiss. essential oil and nisin on Bacillus cereus ATCC 11778. Food Control 2007, 18, 1043–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahboubi, M.; Bidgoli, F.G. Antistaphylococcal activity of Zataria multiflora essential oil and its synergy with vancomycin. Phytomedicine 2010, 17, 548–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Shabrawy, M.O.; Marzouk, M.M.; Kawashty, S.A.; Hosni, H.A.; El Garf, I.A.; Saleh, N.A.M. Flavonoid constituents of Dipcadi erythraeum Webb. & Berthel. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Dis. 2016, 6, 404–405. [Google Scholar]

- Satyal, P.; Paudel, P.; Poudel, A.; Setzer, W.N. Antimicrobial activities and constituents of the leaf essential oil of Lawsonia inermis growing in Nepal. Pharmacol. OnLine 2012, 1, 31–35. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, F. GIS, GPS and remote sensing application to investigate agricultural potential in Cholistan. Soc. Nat. 2007, 19, 55–64. [Google Scholar]

- Chaves, T.P.; Pinheiro, R.E.E.; Melo, E.S.; Soares, M.J.D.S.; Souza, J.S.N.; de Andrade, T.B.; Telma, L.; Gomes, L.; Coutinho, H.D. Essential oil of Eucalyptus camaldulensis Dehn potentiates β-lactam activity against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli resistant strains. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 112, 70–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barra, A.; Coroneo, V.; Dessi, S.; Cabras, P.; Angioni, A. Chemical variability, antifungal and antioxidant activity of Eucalyptus camaldulensis essential oil from Sardinia. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2010, 5, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younis, A.; Mehdi, A.; Riaz, A. Supercritical carbon dioxide extraction and gas chromatography analysis of Jasminum sambac essential oil. Pak. J. Bot. 2011, 43, 163–168. [Google Scholar]

- Mukesi, M.; Iweriebor, B.C.; Obi, L.C.; Nwodo, U.U.; Moyo, S.R.; Okoh, A.I. The activity of commercial antimicrobials, and essential oils and ethanolic extracts of Olea europaea on Streptococcus agalactiae isolated from pregnant women. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2019, 19, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleditch, B.S. Kuwaiti Plants: Distribution, Traditional Medicine, Pytochemistry, Pharmacology and Economic Value; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 2012; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Artizzu, N.; Bonsignore, L.; Cottiglia, F.; Loy, G. Studies on the diuretic and antimicrobial activity of Cynodon dactylon essential oil. Fitoterapia 1996, 67, 174–176. [Google Scholar]

- Arjunan, N.; Murugan, K.; Madhiyazhagan, P.; Kovendan, K.; Prasannakumar, K.; Thangamani, S.; Barnard, D.R. Mosquitocidal and water purification properties of Cynodon dactylon, Aloe vera, Hemidesmus indicus and Coleus amboinicus leaf extracts against the mosquito vectors. Parasitol. Res. 2012, 110, 1435–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilakoglou, I.; Dhima, K.; Paschalidis, K.; Ritzoulis, C. Herbicidal potential on Lolium rigidum of nineteen major essential oil components and their synergy. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2013, 25, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llewellyn, R.S.; D’emden, F.H.; Owen, M.J.; Powles, S.B. Herbicide resistance in rigid ryegrass (Lolium rigidum) has not led to higher weed densities in Western Australian cropping fields. Weed Sci. 2009, 57, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Rabia, A. Ethnobotany among Bedouin Tribes in the Middle East. In Medicinal and Aromatic Plants of the Middle-East; Springer: Dordrech, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Khanuja, S.P.; Shasany, A.K.; Pawar, A.; Lal, R.K.; Darokar, M.P.; Naqvi, A.A.; Kumar, S. Essential oil constituents and RAPD markers to establish species relationship in Cymbopogon Spreng.(Poaceae). Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2005, 33, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, G.M.; Almasaudi, S.B.; Azhar, E.; Al Jaouni, S.K.; Harakeh, S. Biological activity of Cymbopogon schoenanthus essential oil. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2017, 24, 1458–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samejo, M.Q.; Memon, S.; Bhanger, M.I.; Khan, K.M. Chemical composition of essential oil from Calligonum polygonoides Linn. Nat. Prod. Res. 2013, 27, 619–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samejo, M.Q.; Memon, S.; Bhanger, M.I.; Khan, K.M. Essential oil constituents in fruit and stem of Calligonum polygonoides. Ind. Crops Prod. 2013, 45, 293–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, S.S.M.; Alsaadi, A.I.; Youssef, E.G.; Khitrov, G.; Noreddin, A.M.; Husseiny, M.I.; Ibrahim, A.S. Calli Essential Oils Synergize with Lawsone against Multidrug Resistant Pathogens. Molecules 2017, 22, 2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elfotoh, M.A.; Shams, K.A.; Anthony, K.P.; Shahat, A.A.; Ibrahim, M.T.; Abdelhady, N.M.; Azim, N.S.; Hammouda, F.M.; El-Missiry, M.M.; Saleh, M.A. Lipophilic Constituents of Rumex vesicarius L. and Rumex dentatus L. Antioxidans 2013, 2, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harzallah, H.J.; Kouidhi, B.; Flamini, G.; Bakhrouf, A.; Mahjoub, T. Chemical composition, antimicrobial potential against cariogenic bacteria and cytotoxic activity of Tunisian Nigella sativa essential oil and thymoquinone. Food Chem. 2011, 129, 1469–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Z.; Feng, W.; Cao, J.; Cao, D.; Jiang, W. Antioxidant activity and total phenolic contents in peel and pulp of Chinese jujube (Ziziphus jujuba Mill) fruits. J. Food Biochem. 2009, 33, 613–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghannadi, A.; Tavakoli, N.; Mehri-Ardestani, M. Volatile constituents of the leaves of Ziziphus spina-christi (L.) Willd. from Bushehr, Iran. J. Essen. Oil Res. 2003, 15, 191–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, A.K.; Anis, I.; Shah, M.R. Chemical Composition and Antifungal Activity of the Essential Oil of Galium tricornutum subsp. longipedanculatum from Pakistan. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2015, 51, 164–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rehaily, A.J.; Alqasoumi, S.I.; Yusufoglu, H.S.; Al-Yahya, M.A.; Demirci, B.; Tabanca, N.; Wedge, D.E.; Demirci, F.; Bernier, U.R.; Becnel, J.J.; et al. Chemical Composition and biological activity of Haplophyllum tuberculatum Juss. essential oil. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants 2014, 17, 452–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tampe, J.; Parra, L.; Huaiquil, K.; Quiroz, A. Potential repellent activity of the essential oil of Ruta chalepensis (Linnaeus) from Chile against Aegorhinus superciliosus (Guérin) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2016, 16, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alali, F.; Hudaib, M.; Aburjai, T.; Khairallah, K.; Al-Hadidi, N. GC-MS Analysis and Antimicrobial Activity of the Essential Oil from the Stem of the Jordanian Toothbrush Tree Salvadora persica. Pharm. Biol. 2005, 42, 577–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sofrata, A.; Santangelo, E.M.; Azeem, M.; Borg-Karlson, A.K.; Gustafsson, A.; Pütsep, K. Benzyl isothiocyanate, a major component from the roots of Salvadora persica is highly active against Gram-negative bacteria. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e23045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrotra, V.; Mehrotra, S.; Kirar, V.; Shyam, R.; Misra, K.; Srivastava, A.K.; Nandi, S.P. Antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of aqueous extract of Withania somnifera against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. Res. 2017, 1, 40–45. [Google Scholar]

- AbouZid, S.; Elshahaat, A.; Ali, S.; Choudhary, M.I. Antioxidant activity of wild plants collected in Beni-Sueif governorate, Upper Egypt. Drug Discov. Ther. 2008, 2, 286–288. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, D.H.; Wang, Z.; Liang, Z.Y.; Yang, X.B.; Xu, J. Comparative evaluation of the chemical composition of essential oil from twig, leaf and root of Clerodendrum inerme (L.). Gaertn. Adv. Mat. Res. 2012, 343, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deena, M.J.; Thoppil, J.E. Antimicrobial activity of the essential oil of Lantana camara. Fitoterapia 2000, 71, 453–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, E.O.; Almeida, T.S.; Menezes, I.R.; Rodrigues, F.F.; Campos, A.R.; Lima, S.G.; Costa, J.G. Chemical composition of essential oil of Lantana camara L.(Verbenaceae) and synergistic effect of the aminoglycosides gentamicin and amikacin. Rec. Nat. Prod. 2012, 6, 144–150. [Google Scholar]

- Benavides Calvache, O.L.; Villota, J.M.; Milena Tovar, D. Characterization of essential oil present in the leaves of Phyla nodiflora (L.) Greene (OROZUL). Univ. Salud 2010, 12, 57–64. [Google Scholar]

- Senatore, F. Della Porta, G.; Reverchon, E. Constituents of Vitex agnus-castus L. Essential Oil Flavour. Fragr. J. 1996, 11, 179–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalilzadeh, E.; Saiah, G.V.; Hasannejad, H.; Ghaderi, A.; Ghaderi, S.; Hamidian, G.; Mahmoudi, R.; Eshgi, D.; Zangisheh, M. Antinociceptive effects, acute toxicity and chemical composition of Vitex agnus-castus essential oil. Avicenna J. Phytomed. 2015, 5, 218. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.S.; Zhu, F.; Huang, M.Z. GC/MS analysis of the chemical constituents of the essential oil from the fruits of Avicennia marina. Fine Chem. 2009, 3, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Akhbari, M.; Batooli, H.; Kashi, F.J. Composition of essential oil and biological activity of extracts of Viola odorata L. from central Iran. Nat. Prod. Res. 2012, 26, 802–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Rahim, I.R. Control of Alternaria rot disease of pear fruits using essential oil of Viola odorata. J. Phytopathol. Pest Manag. 2016, 3, 71–84. [Google Scholar]

- Charles, D.J.; Simon, J.E.; Singh, N.K. The essential oil of Alpinia galanga Willd. J. Essent. Oil Res. 1992, 4, 81–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Wang, C.; Wei, J.; Li, X.; Wang, P.; Zhou, Z.; Huang, D.; Deng, Z. Composition of the essential oil from Alpinia galanga rhizomes and its bioactivity on Lasioderma serricorne. Bull. Insectol. 2014, 67, 247–254. [Google Scholar]

- Das, A.; Dey, S.; Sahoo, R.K.; Sahoo, S.; Subudhi, E. Antibiofilm and antibacterial activity of essential oil bearing Zingiber officinale Rosc.(Ginger) Rhizome against multi-drug resistant isolates. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants 2019, 22, 1163–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Bai, M.; Yang, J.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Qin, J.; Kuang, Y.; Sampietro, D.A. Chemical composition and larvicidal activity of essential oils from Peganum harmala, Nepeta cataria and Phellodendron amurense against Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae). Saudi Pharm. J. 2020, 28, 560–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraga, B.M. Natural sesquiterpenoids. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2006, 23, 943–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raut, J.S.; Karuppayil, S.M. A status review on the medicinal properties of essential oils. Ind. Crops Prod. 2014, 62, 250–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajjadi, S.E.; Ghassemi, N.; Shokoohinia, Y.; Moradi, H. Essential oil composition of flowers of Anthemis odontostephana Boiss. var. odontostephana. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants 2013, 16, 247–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezazi, A.; Rahchamani, N.; Ghahremaninejad, F. The flora of Saluk National Park, Northern Khorassan province, Iran. J. Biodivers. Environ. Sci. 2014, 5, 45–71. [Google Scholar]

- Rabie, M.; Asri, Y.; Hamzehee, B.; Jalili, A.; Sefidkon, F. Determination of chemotaxonomic indices of Artemisia sieberi Besser based on environmental parameters in Iran. Iran. J. Bot. 2012, 18, 149–157. [Google Scholar]

- Paolini, J.; Barboni, T.; Desjobert, J.M.; Djabou, N.; Muselli, A.; Costa, J. Chemical composition, intraspecies variation and seasonal variation in essential oils of Calendula arvensis L. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2010, 38, 865–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandagopal, S.; Ranjitha Kumari, B.D. Adenine sulphate induced high frequency shoot organogenesis in callus and in vitro flowering of Cichorium intybus L. cv. Focus-a potent medicinal plant. Acta Agric. Slov. 2006, 87, 415–425. [Google Scholar]

- Mabrouk, S.; Elaissi, A.; Ben Jannet, H.; Harzallah-Skhiri, F. Chemical composition of essential oils from leaves, stems, flower heads and roots of Conyza bonariensis L. from Tunisia. Nat. Prod. Res. 2011, 25, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, A.A.F.; Fregonezi, A.M.D.T.; Bassi, D.; Mangolin, C.A.; de Oliviera Collet, S.A.; de Oliveira Junior, R.S.; da Silva, M.d.F.P. Evidence of high gene flow between samples of horseweed (Conyza canadensis) and hairy fleabane (Conyza bonariensis) as revealed by isozyme polymorphisms. Weed Sci. 2015, 63, 604–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, Z.; Kuhestani, K.; Abdollahi, V.; Mahmood, A. Ethnopharmacological studies of indigenous medicinal plants of Saravan region: Baluchistan Iran. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 153, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louhaichi, M.; Salkini, A.K.; Estita, H.E.; Belkhir, S. Initial assessment of medicinal plants across the Libyan Mediterranean coast. Adv. Environ. Biol. 2011, 5, 359–370. [Google Scholar]

- Roby, M.H.H.; Sarhan, M.A.; Selim, K.A.H.; Khalel, K.I. Antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of essential oil and extracts of fennel (Foeniculum vulgare L.) and chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla L.). Ind. Crop. Prod. 2013, 44, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EL-Kamali, H.H.; Yousif, M.O.; Ahmed, O.I.; Sabir, S.S. Phytochemical analysis of the essential oil from aerial parts of Pulicaria undulata (L.) Kostel from Sudan. Ethnobot. Leafl. 2009, 13, 467–471. [Google Scholar]

- Nematollahi, F.; Rustaiyan, A.; Larijani, K.; Nadimi, M.; Masoudi, S. Essential oil composition of Artemisia biennisz Willd. and Pulicaria undulata (L.) CA Mey.: Two compositae herbs growing wild in Iran. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2006, 18, 339–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Demirci, B.; Kiyan, H.T.; Bernier, U.R.; Tsikolia, M.; Wedge, D.E.; Khan, I.; Baser, K.; Tabanca, N. Biting deterrence, repellency, and larvicidal activity of Ruta chalepensis (Sapindales: Rutaceae) essential oil and its major individual constituents against mosquitoes. J. Med. Entomol. 2013, 50, 1267–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Znini, M.; Bouklah, M.; Majidi, L.; Kharchouf, S.; Aouniti, A.; Bouyanzer, A.; Hammouti, B.; Costa, J.; Al-Deyab, S.S. Chemical composition and inhibitory effect of Mentha spicata essential oil on the corrosion of steel in molar hydrochloric acid. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2011, 6, 691–704. [Google Scholar]

- Ziaei, A.; Ramezani, M.; Wright, L.; Paetz, C.; Schneider, B.; Amirghofran, Z. Identification of spathulenol in Salvia mirzayanii and the immunomodulatory effects. Phytother. Res. 2011, 25, 557–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Family | Binomial | Taxonomic Authority | Synonyms “Syn.” and/or Common Names (English “Eng.” and/or Arabic “Arb.”) | Reference Categorizing the Plant as Essential Oil-Bearing Plant | Reference for UAE Nativity/Natuaralization | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Aizoaceae/Ficoidaceae (Mesembryanthemum, carpetweed family) | Sesuvium portulacastrum | L. | Sesuvium verrucosum Raf. (Eng. Shoreline purslane, sea purslane, sesuvium) | [35] | [21,22] |

| 2 | Amaranthaceae (Cockscomb family) | Achyranthes aspera | L. | (Eng. Prickly chaff flower) (Arb. Saif el-jinn, umdhrese, sehem, ar-ray, mahoot, na’eem, wazer) | [36] | [21,22] |

| 3 | Aerva javanica | (Burm. f.) Juss. ex Schul. | (Eng. Desert cotton, snow bush) (Arb. Al ara’, twaim, efhe, tirf) | [37,38] | [15,18,21,22,23,24,25,27,28,32] | |

| 4 | Chenopodium album | L. | (Eng. Lamb’s quarters, melde, goosefoot, fat-hen, white goosefoot) (Arb. Shulah, ‘aifajan, rokab al-jamal) | [39] | [15,21,22] | |

| 5 | Anacardiaceae (The cashew, sumac family) | Pistacia khinjuk | Stocks. | [40] | [21] | |

| 6 | Apiaceae/Umbelliferae | Ammi majus | L. | (Eng. Bishop’s flower, bishop’s weed) (Arb. Sannout, sheeh, khilla “khilla sheitani”, nayniya) | [41] | [15,21,22,28] |

| 7 | Anethum graveolens | L. | (Eng. Dill Weed) | [42] | [15,21] | |

| 8 | Ducrosia anethifolia | (DC.) Boiss. | (Arb. Basbaz, haza) | [43] | [15,21,22,28] | |

| 9 | Pimpinella eriocarpa | Banks and Sol. | (Arb. Kusaybirah) | [44] | [15,21] | |

| 10 | Pimpinella puberula | (DC.) Boiss. | [45] | [15,21] | ||

| 11 | Scandix pecten-veneris | L. | (Eng. Shepherd’s-needle, Crib Gwener) (Arb. Mushet) | [46] | [15,21] | |

| 12 | Torilis leptophylla | (L.) Reichenb.f. | (Syn. Caucalis leptophylla) (Eng. Bristle-fruited hedge-parsley) | [47] | [21] | |

| 13 | Apocynaceae (Dogbane family) | Catharanthus roseus | (L.) G. Don | (Syn. Vinca rosea) (Eng. Madagascar periwinkle) | [42] | [15] |

| 14 | Nerium oleander | L. | (Syn. Nerium mascatense) (Eng. Rosebay, olender) (Arb. Defla, haban) | [48] | [15,21,22,28] | |

| 15 | Plumeria rubra | L. | (Eng. Nosegay, frangipan) | [49] | [15,21,22,28] | |

| 16 | Calotropis procera | (Aiton) W.T. Aiton | (Eng. Apple of Sodom, Sodom apple, stabragh, kapok tree, king’s crown, rubber bush, rubber tree, Sodom’s apple milkweed) (Arb. ‘ushar, shakjr, ‘asur, ashkhar “askar”) | [50] | [21,22,28] | |

| 17 | Arecaceae (Palmae, palmaceae family, palm trees) | Phoenix dactylifera | L. | (Eng. Date palm, date palm tree) (Arb. Nakhl, amm-amm) | [51] | [15,21,22,28] |

| 18 | Asteraceae/Compositae/Anthemideae (Sunflower family) | Anthemis odontostephana | Boiss. | (Arb. O’qhowan) | [52] | [15,21] |

| 19 | Artemisia sieberi | Besser | (Eng. Wormwood) | [53] | [28] | |

| 20 | Calendula arvensis | L. | (Eng. Field marigold) (Arb. Ain el baqr, eqhwan-asfar, hanwa, hanuwa) | [54] | [15,21] | |

| 21 | Cichorium intybus | L. | (Eng. Blue daisy, blue dandelion, blue sailors, blue weed, bunk, coffeeweed) (Arb. hindibaa bareeya, chicoria) | [55] | [15,21,28] | |

| 22 | Conyza bonariensis | (L.) Cronq. | (Syn. Conyza linifolia (Willd.) Tackh) (Eng. Flax-leaf Fleabane, Wavy-leaf Fleabane, hairy fleabane) (Arb. hashishat el-jebal, tebaq) | [56] | [21,22] | |

| 23 | Eclipta prostrata | L. | (Syn. Eclipta alba (L.) Hassk.) (Eng. False daisy, Trailing eclipta ). (Arb. Sa’ada, sauweid, masadate) | [57] | [15,21] | |

| 24 | Grantia aucheri | Boiss. | No Information | [58] | [27] | |

| 25 | Launaea nudicaulis | (L.) Hook. f. | (Eng. Hawwa Baqrah ara, hindabah ara, huwah ara, naked launea) (Arb. Huwah al ghazal, safara, huwah, hindabah) | [59,60] | [15,21,22] | |

| 26 | Matricaria aurea | (Loefl.) Sch. Bip. | (Eng. Golden chamomile) (Arb. Babunaj) | [61] | [21,28] | |

| 27 | Matricaria chamomilla | L. | (Syn. Matricaria recutita) (Eng. Chamomile, camomile, german chamomile) | [62] | [63] | |

| 28 | Pluchea arabica | (Boiss.) Qaiser and Lack | (Eng. Pluchea) (Arb. godot) | [64] | [28] | |

| 29 | Pluchea dioscoridis | (L.) DC. | (Syn. Conyza dioscoridis (L.) Desf., Baccharis dioscoridis L.) (Eng. Ploughmans spikenard, marsh fleabane) (Arb. Sahikee, barnof) | [65] | [15,21,22] | |

| 30 | Pluchea ovalis | (pers.) DC. | (Eng. Woolly camphor-weed) | [66] | [15,21] | |

| 31 | Pseudognaphalium luteo-album | (L.) H. and B. | (Syn. Gnaphalium luteo-album L.) (Eng. Cudweed) (Arb. sabount el’afrit) | [67] | [21,22] | |

| 32 | Pulicaria arabica | (L.) Cass. | (Syn. Inula arabica L./Pulicaria elata Boiss./Pulicaria laniceps Bornm.) (Arb. Iqat, abu ‘ain safra) | [68] | [21] | |

| 33 | Pulicaria glutinosa | Jaub. and Spach | (Arb. Thal, fal, shajarat fal, muhayda, mithidi, shajarat al-mithidi, shneena, zayyan) | [7] | [15,21,22] | |

| 34 | Pulicaria inuloides | (Poir.) DC. | No information | [69,70,71] | [21] | |

| 35 | Pulicaria undulata | (L.) C.A. Meyer | (Syn. Pulicaria crispa (Forssk.) Benth.) (Eng. Crisp-leaved fleabane) (Arb. Gathgeth, jithjath, ‘urayfijan) | [72] | [15,21,22] | |

| 36 | Rhanterium epapposum | Oliv. | (Eng. Rhanterium) (Arb. Arfaj) | [73] | [15,21,22] | |

| 37 | Senecio glaucus | L. ssp. coronopifolius (Maire) Al. | (Syn. Senecio desfontanei Druce) (Eng. Maire alexander, buck’s horn groundsel) (Arb. Qorreis, murair, zamlooq, shakhees, rejel al ghurab) | [74] | [15,21,22] | |

| 38 | Seriphidium herba-alba | (Asso) Sojak | (Syn. Artemisia herba-alba Asso/Artemisia inculta Del) (Eng. Wormwood, white wormwood) (Arb. Ata, ghata, shih) | [75,76] | [21] | |

| 39 | Sphagneticola trilobata | (Syn. Wedelia paludosa DC.) (Eng. Singapore daisy, creeping-oxeye, trailing daisy, wedelia) | [77] | [15] | ||

| 40 | Bignoniaceae (Bignonias family) | Jacaranda mimosifolia | D. Con | (Eng. Jacaranda, blue jacaranda, black poui, fern tree) | [78] | [15] |

| 41 | Boraginaceae (Borage, forget-me-not family) | Arnebia linearifolia | DC. | No Information | [79] | [21] |

| 42 | Heliotropium europaeum | L. | (Syn. Heliotropium lasiocarpum Fisch. and Mey.) (Eng. European heliotrope, european turnsole) (Arb. Karee) | [80] | [15,21,22] | |

| 43 | Trichodesma africanum | (Syn. Trichosdesma africana (L.) R. Br.) (Eng. African barbbell) | [81] | [15] | ||

| 44 | Brassicaceae/Cruciferae (Cress, mustard family) | Capsella bursa-pastoris | (L.) Medik. | (Eng. Shepherd’s-purse) (Arb. Kis al ra’y) | [82] | [15,21,22] |

| 45 | Cardaria draba | (L.) Desv. | (Syn. Lepidium draba) (Eng. Whitetop, hoary cress) (Arb. lislis) | [83] | [21,22] | |

| 46 | Coronopus didymus | (L.) Sm. | (Eng. Lesser swine-cress) (Arb. Rashad al-barr) | [84] | [21,22] | |

| 47 | Erucaria hispanica | (Eng. Spanish pink mustard, erucaria myagroides) (Arb. Khezaam, saleeh, kromb al sahra) | [79] | [15,21] | ||

| 48 | Eruca sativa | Mill. | (Eng. Salad rocket, rucola, rucoli, rugula, colewort, roquette, garden rocket, rocket) (Arb. Girgir, jirjeer) | [85] | [15,21,22,28] | |

| 49 | Savignya parviflora | (Delile) Webb | (Eng. Jaljalan, kanad al barr, gulgulan, girgees, small whorled cheeseweed) (Arb. Khzaymah, al-thee, jerjees “girgees”, gongolan “qunqulan, jaljelan, galeigelan, bithman”) | [86] | [15,21,22] | |

| 50 | Schimpera arabica | Hochst. and Steud. | [79] | [15,21] | ||

| 51 | Sinapsis arvensis | L. | (Syn. Sinapis arvensis L.) (Eng. Charlock, charlock mustard, wild mustard) | [87] | [15,21] | |

| 52 | Sisymbrium irio | L. | (Eng. London rocket) (Arb. Howairah, shelyat, figl el-gamal, harrah) قراص حمار | [88] | [21,28] | |

| 53 | Capparaceae/Capparidaceae (Caper family) | Capparis cartilaginea | Decne. | (Eng. Caper) (Arb. Qubr, sediru, ashflah, lezaf “losef, lusfeh, ewsawf) | [89] | [15,21,22,26,28] |

| 54 | Capparis spinosa | L. | (Eng. Caper bush, flinders rose) (Arb. Kobar, lasafa, fakouha, shawk mal homar, shafallah, delayeer, dabayee) | [89,90] | [15,21,22,28] | |

| 55 | Caryophyllaceae/Illecebraceae (Carnation family) | Stellaria media | (L.) Vill. | (Eng. Chickweed, common chickweed, chickenwort, craches, maruns, winterweed, lawn weed) (Arb. Meshit, hashishet el-qizaz, qizaza) | [91] | [15,21] |

| 56 | Casuarinaceae (Beefwood family) | Casuarina equisetifolia | (Syn. Casuarina equistetifolia J.R. and G. Forst.) (Eng. Rhu, casuarina tree) | [92,93] | [15] | |

| 57 | Cistaceae (Rock-rose, rock rose family) | Helianthemum kahiricum | Delile | (Eng. Rock rose, sun rose) (Arb. Ragroog, qsasah, hashma) | [94] | [15,21,22] |

| 58 | Cleomaceae | Cleome amblyocarpa | Barr. and Murb. | (Syn. Cleome africana, Cleome arabica, Cleome daryoushian) (Eng. Spider flower) (Arb. Adheer, durrayt an-na’am, khunnayz, ufaynah) | [4,95] | [21] |

| 59 | Cleome brachycarpa | Vahl ex DC. | (Syn. Cleome vahliana Farsen) (Arb. Za’af, mkhaysah) | [96] | [15,21] | |

| 60 | Cleome droserifolia | Del. | (Syn. Roridula droserifolia Forssk.) (Eng. Cleome herb) | [97] | [15] | |

| 61 | Cleome gynandra | L. | (Syn. Gynandropsis gynandra (L.)Briq.) (Eng. Shona cabbage, African cabbage) (Arb. Abu qarim) | [98] | [21] | |

| 62 | Combretaceae | Terminalia catappa | L. | (Eng. Indian almond-wood, bastard almond, andaman badam) هليلج هندي | [99] | [15] |

| 63 | Convolvulaceae (Morning glory, bindweed family) | Ipomoea aquatica | Forssk. | (Eng. Kang kong, water convolvulus, water spinach, swamp cabbage, ong choy, hung tsai, rau muong) السبانخ المائي | [100] | [21,22] |

| 64 | Ipomoea obscura | (Eng. Obscure morning-glory, small white morning glory) | [101,102] | [21] | ||

| 65 | Cucurbitaceae (Gourd family) | Momordica charantia | L. | (Eng. Bitter melon, bitter gourd, bitter squash, balsam-pear) | [103,104] | [24] |

| 66 | Luffa acutangula | (L.) Roxb. | (Eng. Angled luffa, chinese okra, dish cloth gourd, ridged gourd, sponge gourd, vegetable gourd, strainer vine, ribbed loofah, silky gourd, ridged gourd, silk gourd, sinkwa towelsponge) | [103,105] | [21] | |

| 67 | Cyperaceae (Sedges family) | Cyperus arenarius | Retz. | (Syn. Bobartia indica L.) (Eng. dwarf sedge) | [106] | [21,22,34] |

| 68 | Cyperus conglomeratus | Rottb. | (Eng. Cyperus, mali tamachek saad) (Arb. Thenda. Ayzm, chadrum, qassis, rasha) | [107] | [15,21,22,34] | |

| 69 | Cyperus rotundus | L. | (Eng. Coco-grass, Java grass, nut grass, purple nut sedge, red nut sedge, Khmer kravanh chruk) (Arb. Sa’ed, sa’ed al hammar, hasir) | [108] | [15,21,22,28,34] | |

| 70 | Euphorbiaceae (Spurge, castor, euphorbias family) | Euphorbia helioscopia | L. | (Eng. Sun spurge, madwoman’s milk) (Arb. Haleeb al-diba, sa’asa, tanahout, kerbaboosh) | [109] | [21,22] |

| 71 | Euphorbia hirta | L. | (Eng. Asthma plant, asthma weed, pill-bearing spurge) (Arb. Libbein, demeema, menthra) | [110] | [15,21,22] | |

| 72 | Euphorbia peplus | L. | (Syn. Euphorbia peplis L.) (Eng. Petty spurge, radium weed, cancer weed, milkweed) (Arb. Khunaiz) | [111] | [21,22,28] | |

| 73 | Ricinus communis | L. | (Eng. Castor oil) (Arb. ‘Arash, ash’asheh, khasaab, khirwa “khurwa’a”, junijund, tifsh) | [112] | [15,21,22,28] | |

| 74 | Fabaceae/Leguminosae/Papilionoideae (Pea family) | Alhagi maurorum | Medik. | (Syn. Alhagi graecorum Boiss.) (Eng. Camelthorn, camelthorn-bush, caspian manna, persian mannaplant) (Arb. Shwaika, agool, heidj) | [113,114] | [15,24] |

| 75 | Lotus halophilus | Boiss. and Spruner | (Eng. Greater bird’s foot trefoi) (Arb. Horbeith “hurbuth”, garn al ghazal, ‘asheb al ghanem) | [79,89] | [15,21,22] | |

| 76 | Medicago polymorpha | L. | (Eng. California burclover, toothed bur clover, toothed medick, burr medic) | [115] | [15,21,22] | |

| 77 | Medicago sativa | L. | (Eng. Alfalfa, lucerne) | [116] | [15] | |

| 78 | Rhynchosia minima | (L.) DC. | (Eng. least snout-bean, burn-mouth-vine and jumby bean) (Arb. Baql) | [117] | [15,21,22] | |

| 79 | Tephrosia persica | Boiss. | (Syn. Tephrosia apollinea (Delile) DC.) (Arb. Dhafra, omayye, nafal) | [118] | [15,21,32] | |

| 80 | Trigonella hamosa | L. | (Eng. Branched fenugreek, Egyptian fenugreek) (Arb. Nafal, qutifa, qirqas, darjal, eshb al-malik, qurt) | [79] | [15,21,22] | |

| 81 | Ononis sicula | Guss. | ------ | [119] | [21] | |

| 82 | Acacia nilotica | (L.) Delile | (Syn. Acacia Arabica (Lam.) Willd.) (Eng. Gum arabic tree, babul/kikar, Egyptian thorn, sant tree, al-sant, prickly acacia) (Arb. Sunt garath “kurut”, babul, tulh. Fruit: karat) | [120,121] | [15,21,22,26,28] | |

| 83 | Acacia tortilis | (Forssk.) Hayne | (Eng. Umbrella thorn) (Arb. Samr “samur”, salam) | [120,122] | [15,21,22,26,32] | |

| 84 | Prosopis farcta | (Banks and Sol.) Mac. | (Eng. Dwarf mesquite, syrian mesquite) (Arb. Yanbut, agoul, awsaj) | [123] | [15,21,22] | |

| 85 | Frankeniaceae | Frankenia pulverulenta | L. | (Eng. European Frankenia, European sea heath) (Arb. Molleih, hamra (hmaira), Umm thurayb) | [124] | [21,22] |

| 86 | Geraniaceae (Geranium family) | Erodium cicutarium | (L.) L Her. Ex Aiton | (Eng. Redstem filaree, redstem stork’s bill, common stork’s-bill, pinweed) | [125] | [21] |

| 87 | Hypericaceae (St. Johnswort family) | Hypericum perforatum | (Eng. St.John’s wort) | [126] | [30] | |

| 88 | Iridaceae (Irises family) | Gynandriris sisyrinchium | (L.) Parl. | (Syn. Iris sisyrinchium L., Moraea sisyrinchium (L.) Ker Gawl.) (Eng. Barbary Nut, mountain iris) (Arb. Khowais, su’ayd, ‘unsayl) | [127] | [15,21] |

| 89 | Lamiaceae/Labiatae (Mint, deadnettle family) | Lallemantia royleana | (Benth.) Benth. | (Eng. Bian bing cao) | [128] | [21] |

| 90 | Mentha spicata | spicata (Eng. Spearmint, spear mint) | [129] | [63,130] | ||

| 91 | Ocimum forsskaolii | Benth. | (Syn. Ocimum forskolei Benth.) (Eng. Rehan, sawma) (Arb. Basil) | [131] | [15,21,28] | |

| 92 | Salvia aegyptiaca | L. | (Eng. Egyptian sage) (Arb. Ra’al, na’aim, ghbeisha, shajarat al ghazal, khizam) | [132] | [15,21,22,24,28] | |

| 93 | Salvia macilenta | Boiss. | (Eng. Khizama) (Arb. Khmayzah lethnay, bithman) | [133] | [15,21,22] | |

| 94 | Salvia macrosiphon | Boiss. | (Arb. Shajarat Al Ghazal) | [134] | [15,21] | |

| 95 | Salvia mirzayanii | Rech.f. and Esfandiari | [135] | [21] | ||

| 96 | Salvia spinosa | L. | (Arb. Shajarat al-ghazal) | [136] | [21,22] | |

| 97 | Teucrium polium | L. | (Eng. Felty germander) | [137,138] | [21,28] | |

| 98 | Teucrium stocksianum | Boiss. | (Eng. Jadah, yadah, Ja‘adah) (Arb. Ya’dah, brair) | [6,139] | [15,21,22,24,32,28] | |

| 99 | Zataria multiflora | Boiss. | (Eng. Za’atar, shirazi thyme) | [140,141] | [24] | |

| 100 | Liliaceae (lily family) | Dipcadi erythraeum | Webb and Berth. | (Synonym: Dipcadi serotinum (L.) Medik.) (Eng. Brown Lily, Hyacinthus serotinus, mesailemo, besailemo) (Arb. Busalamo, ansel, misselmo, shkal). | [142] | [15,21,22] |

| 101 | Lythraceae | Lawsonia inermis | L. | (Eng. Egyptian Privet, the henna tree, mignonette tree) | [143] | [15,21,22,24,28] |

| 102 | Malvaceae/Tiliaceae (Mallows family) | Corchorus depressus | (L.) Stocks. | (Eng. Mulakhiyah al bar, sutaih, rukbat al jamal) (Arb. Matara, seluntah, mulukhia el bar, waikai) | [144] | [15,21,22] |

| 103 | Moringaceae (Moringa family) | Moringa peregrina | (Forssk.) Fiori | (Eng.Wild drumstick tree) (Arb. Shu’, yasar, baan, ’aweyr, bayreh, terfaal, yayn) | [8] | [21] |

| 104 | Myrtaceae (Myrtle family) | Eucalyptus camaldulensis | Dehnh. | (Syn. Eucalyptus camaldulensis Dehn.) (Eng. River red gum, red gum, Murray red) | [145] | [15] |

| 105 | Eucalyptus pimpiniana | Maiden | “Eng. Pimpin mallee, red dune mallee” | [146] | [15] | |

| 106 | Oleaceae (Olive family) | Jasminum sambac | (L.) Ait. | (Eng. Arabian jasmine) الفل | [147] | [15] |

| 107 | Olea europaea | L. subsp. Cuspidata | (Wall. Ex G. Don) ciferri (Eng. Olive tree) (Arb. ‘Itm, mitan) | [148] | [21] | |

| 108 | Plantaginaceae (Plantain family) | Plantago amplexicaulis | Cav. | (Eng. Ispaghula, Plantain, rablat al mistah, lesan al hamal) (Arb. gerenwa, rabl, aynsum, khannanit an na’ja) | [79] | [15,21,22] |

| 109 | Plantago boissieri | Hausskn. and Bornm. | (Arb. Rabl, yanam) | [149] | [15,21,22] | |

| 110 | Poaceae/Gramineae (Gramineae, true grasses family) | Cenchrus ciliaris | L. | (Eng. Buffelgrass, African foxtail grass, sand-burr) (Arb. Sadat, khadir, thumum, gharaz, drab, labaytad) | [79] | [15,21,32,34] |

| 111 | Cynodon dactylon | (L.) Pers. | (Eng. Bermudagrass, dubo, dog’s tooth grass, Bahama grass, devil’s grass, couch grass) (Arb. Thi’il, negil “najiel”, najm, sheel, bizait) | [150,151] | [15,21,34] | |

| 112 | Desmostachya bipinnata | (L.) Stapf | (Eng. Halfa grass, big cordgrass, salt reedgrass) (Arb. Halfa, hafla and sanaiba) | [152] | [15,21,34] | |

| 113 | Lolium rigidum | Gaudin | (Eng. Wimmera ryegrass, Swiss rye grass) (Arb. Hayyaban, shilm, ziwan, simbil, rabiya) | [153] | [15,21] | |

| 114 | Cymbopogon commutatus | (Steud.) Stapf | (Syn. Cymbopogon parkeri Stapf.) (Eng. Incense grass, Rosagrass) (Arb. Alklathgar, sakhbar, hamra, idhkhir, khasaab) | [154] | [15,21,22,34] | |

| 115 | Cymbopogon jwarancusa | subsp. olivieri (Boiss.) | (Eng. Oilgrass, iwarancusa grass) | [155] | [20,21] | |

| 116 | Cymbopogon schoenanthus | (L.) Spreng. | (Eng. Camel grass, camel’s hay, fever grass, geranium grass, West Indian lemon grass) (Arb. Adlghar, hashmah) | [155,156] | [15,21,22,24,28,34] | |

| 117 | Polygonaceae (buckwheat family) | Calligonum comosum | L’Her. | (Synonym: Calligonum polygonoides subsp. comosum (L‘Her.) Soskov) (Eng. Fire bush) (Arb. Arta, waragaat as-shams, ‘abal, dhakar) | [157,158,159] | [15,21,22,24,28] |

| 118 | Rumex vesicarius | L. | (Eng. Sorrel, Bladder dock, Rosy dock, Ruby dock) (Arb. Humayth “hommeid, hummad, hambad”, hambasees) | [160] | [15,21,22,24,28] | |

| 119 | Ranunculaceae (Buttercup, crowfoot family) | Nigella sativa | L. | (Eng. Black seed, black cumin) | [161] | [24] |

| 120 | Rhamnaceae (Buckthorn Family) | Ziziphus jujuba | Mill. | (Eng. Chinese date, jujube) | [162] | [15] |

| 121 | Ziziphus spina-christi | (L.) Willd. | (Eng. Christ’s thorn jujube, Christ’s torn, nabk tree) (Arb. Sidr, ber, ‘ilb, zaqa) | [163] | [15,21,22,28] | |

| 122 | Rubiaceae (coffee, Rue, madder, bedstraw family) | Galium tricornutum | Dandy | (Eng. Rough corn bedstraw, roughfruit corn bedstraw and corn cleavers) | [164] | [21] |

| 123 | Rutaceae (Rue, citrus family) | Haplophyllum tuberculatum | (For.) A. Juss. | (Syn. Haplophyllum arabicum) (Eng. Sazab, zeita, kheisa, mesaika) (Arb. Srayu’u asraw, mekhiseh “Umm musayka”, kirkhan, zuqayqah, furaythah, zifra al-tais, sinam al-tais. Khaisa, sjaharet al-ba’ud, sjaharet al-ghazal, tafar al-tays, khokhawot, mekhisat al-hamr) | [165] | [15,21,22,28] |

| 124 | Ruta chalepensis | L. | (Eng. Rue, fringed rue) | [166] | [22,24] | |

| 125 | Salvadoraceae/Salourloruceae | Salvadora persica | L. | (Eng. Toothbrush tree, mustard tree, mustard bush) (Arb. Suwak, rak, (‘arak, yeharayk, ehereek) | [167,168] | [15,21,22,24,28] |

| 126 | Solanaceae (Nightshade family) | Withania somnifera | (L.) Dunal. | (Eng. Ashwagandha, Indian ginseng, poison gooseberry, winter cherry) (Arb. Babu “ebab”, sumal far, haml balbool, morgan, simm, frakh) | [169] | [21] |

| 127 | Tamaricaceae (Tamarisk family) | Tamarix nilotica | (Ehrenb.) Bunge | (Syn. Tamarix mannifera (Ehrenb.) Bunge (h)/Tamarix arabica Bunge) (Eng. Nile tamarisk) (Arb. tarfa’, “terfat”, athl) | [170] | [15,21,22,26,28] |

| 128 | Verbenaceae (Verbena, vervain family) | Clerodendrum inerme | (L.) Gaertn. | (Eng. Vanajai, garden quinine) | [171] | [15] |

| 129 | Lantana camara | L. | (Eng. Tickberry) | [172,173] | [15] | |

| 130 | Phyla nodiflora | (L.) Greene | (Syn. Phyla nodiflora/Lippia (Phyla) nodiflora (L.) Greene/Phylain nodiflora/Lippia nodiflora (L.) Mychx.) (Arb. Berbin al-jedi, herum dezen, thayyel sini, lebbia, farfakh) | [174] | [15,21] | |

| 131 | Vitex agnus-castus L. | L. | (Eng. Chaste tree) | [175,176] | [20,21,22] | |

| 132 | Avicennia marina | (Forssk.) Vierh. | (Syn. Avicennia marina L.) (Eng. Grey mangrove, white mangrove) (Arb. Qurm, gurm) | [177] | [15,21,22,28] | |

| 133 | Violaceae | Viola odorata | L. | (Eng. Sweet violet, garden violet, common blue violet, viol, viotea) | [178,179] | [24] |

| 134 | Zingiberaceae (Ginger family) | Alpinia galanga | (L.) Sw | (Eng. Greater galangal, thai galangal, blue ginger, thai ginger) | [180,181] | [24] |

| 135 | Zingiber officinale | Roscoe | (Eng. Ginger) | [182] | [24] | |

| 136 | Zygophyllaceae (Caltrop, bean-caper, creosote-bush family) | Peganum harmala | L. | (Eng. African rue, Syrian rue, wild rue, harmal shrub, harmel, isband, ozallalk, steppenraute) | [183] | [24] |

| 137 | Tribulus parvispinus | Presl | (Syn. Tribulus terrestris) (Eng. Puncture vine, Land caltrops, puncture vine) (Arb. Shershir, kuteb “qatb”, hisek, badl, shuraysah, shiqshiq, dreiss) | [184] | [15,21] |

| No. | Botanical Name (Syn./Eng./Arb. Names) | Form | Life Form | Life Cycle | Economic Value | Folk Medicine | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Anthemis odontostephana Boiss. (Arb. O’qhowan) | H | Th | A | Arom, EOs * | [52,186,187] | |

| 2 | Artemisia sieberi Besser (Eng. Wormwood) | H/S | Ch | P | Med, Arom, Eos *, Flav!, Cosm! | (+) (UAE) | [188] |

| 3 | Calendula arvensis L. (Eng. Field marigold) (Arb. Ain el baqr, eqhwan-asfar, hanwa, hanuwa) | H | Th | A | Med, Fod, Nutr, EOs, Cosm | (+) | [54,189] |

| 4 | Cichorium intybus L. (Eng. Blue daisy, blue dandelion, blue sailors, blue weed, bunk, coffeeweed) (Arb. hindibaa bareeya, chicoria) | H | Ch | P | Med, Flav, Forg, EOs, Lands | (+) (Europe: “R”: Are aromatic and used with coffee as a substitute) (UAE: “L”: Boiled in water as fever treatment + “Fr”: Eaten to treat headache and boiled in water for treating jaundice) | [55,190] |

| 5 | Conyza bonariensis (L.) Cronq. (Syn. Conyza linifolia (Willd.) Tackh) (Eng. Flax-leaf Fleabane, Wavy-leaf Fleabane, hairy fleabane) (Arb. hashishat el-jebal, tebaq) | H/W | Th | A/B/P | Med, EOs | (+) | [191,192] |

| 6 | Eclipta prostrata L. (Syn. Eclipta alba (L.) Hassk.) (Eng. False daisy, Trailing eclipta ) (Arb. Sa’ada, sauweid, masadate) | H/W | Th | A | Med, Arom, EOs | (+) (China: Herbal medicine) (North Africa: Juice of fresh plant applied to scalp to improve hair growth) | [57] |

| 7 | Grantia aucheri Boiss. | H | He | A | Med, EOs | (+) (Pakistan: “W”: for snake and scorpion bite) | [58,193] |

| 8 | Launaea nudicaulis (L.) Hook. f. (Eng. Hawwa Baqrah ara, hindabah ara, huwah ara, naked launea) (Arb. Huwah al ghazal, safara, huwah, hindabah) | H | Ch | A/P | Med, EOs | (+) | [59,60] |

| 9 | Matricaria aurea (Loefl.) Sch. Bip. (Eng. Golden chamomile) (Arb. Babunaj) | H | Th | A | Med, Arom *, Eos *, Cosm * | (+) (As a carminative and anti-inflammatory) (Used in ointments and lotions) (As a mouthwash against infections of mouth and gums) (chamomile essential oils “true chamomile oil”: for aromatherapy) (UAE: Medicinal tea. “Fl”: To treat abdominal complains) | [194] |

| 10 | Matricaria chamomilla L. (Syn. Matricaria recutita) (Eng. Chamomile, camomile, german chamomile) | H | Th | A | Med, Nutr, Arom, Eos * | (+) (Saudi Arabia: “Fl”: as antibacterial) (Jordan: to treat various diseases “e.g., inflammation and cancer”) | [107,195] |

| 11 | Pluchea arabica (Boiss.) Qaiser and Lack (Eng. Pluchea) (Arb. godot) | H | Ch | P | Med, Arom, Eos *, Cosm | (+) (UAE: To treat skin and as doedorant) (“W”: Boiled to treat skin ailments + “L”: Extract used as ear drops + “L”: Fresh “L” rubbed on body as deodorant) | [64,66] |

| 12 | Pluchea dioscoridis (L.) DC. (Syn. Conyza dioscoridis (L.) Desf., Baccharis dioscoridis L.) (Eng. Ploughmans spikenard, marsh fleabane) (Arb. Sahikee, barnof) | S/T | Ch | P | Med *, Arom, EOs | (+) (Many Important Applications) (UAE) | [65,66] |

| 13 | Pluchea ovalis (pers.) DC. (Eng. Woolly camphor-weed) | S/T | Ph | A/P | Med *, Arom, EOs | (+) (UAE) | [66] |

| 14 | Pseudognaphalium luteo-album (L.) H. and B. (Syn. Gnaphalium luteo-album L.) (Eng. Cudweed) (Arb. sabount el’afrit) | F/H | Th | A | EOs | (+) | [67] |

| 15 | Pulicaria arabica (L.) Cass. (Syn. Inula arabica L./Pulicaria elata Boiss./Pulicaria laniceps Bornm.) (Arb. Iqat, abu ‘ain safra) | H | He | A/P | EOs | . | [7] |

| 16 | Pulicaria glutinosa Jaub. and Spach (Arb. Thal, fal, shajarat fal, muhayda, mithidi, shajarat al-mithidi, shneena, zayyan) | S | Ch | P | Arom *, EOs, Oth * | [7] | |

| 17 | Pulicaria inuloides (Poir.) DC. | S | Ch | P | Med, Fod, Forg, Arom, EOs, Fuel | (+) | [69,70,71] |

| 18 | Pulicaria undulata (L.) C.A. Meyer (Syn. Pulicaria crispa (Forssk.) Benth.) (Eng. Crisp-leaved fleabane) (Arb. Gathgeth, jithjath, ‘urayfijan) | H/S | Ch | A/P | Med *, Fod, Forg, Arom, Eos *, Fuel | (+) (Dropsy, swelling, edema, gout, febrifuges, painkillers) (Egypt: To treat measles and repel insects) | [196] |

| 19 | Rhanterium epapposum Oliv. (Eng. Rhanterium) (Arb. Arfaj) | S | Ch | p | Forg *, Flav, EOs, Fuel | [197] | |

| 20 | Senecio glaucus L. ssp. coronopifolius (Maire) Al. (Syn. Senecio desfontanei Druce) (Eng. Maire alexander, buck’s horn groundsel) (Arb. Qorreis, murair, zamlooq, shakhees, rejel al ghurab) | H | Th | A | Arom, Eos * | [198] | |

| 21 | Seriphidium herba-alba (Asso) Sojak (Syn. Artemisia herba-alba Asso/Artemisia inculta Del) (Eng. Wormwood, white wormwood) (Arb. Ata, ghata, shih) | S | Ph | P | Med, Eos *, FPre! | (+) (Tunisia) (Inhaling smoke thought to be beneficial for both man and animals) (“Sh”: Young “Sh” eaten by mountain travellers) (Many applications) (UAE: “L”: Crushed as a worm treatment and to combat fevers + Many applications) | [76] |

| 22 | Sphagneticola trilobata (Syn. Wedelia paludosa DC.) (Eng. Singapore daisy, creeping-oxeye, trailing daisy, wedelia) | H | Ch | P | Med, EOs, Lands * | (+) (Brazil) | [75,77] |

| No. | Botanical Name (Syn./Eng./Arb. Names) | Form | Life Form | Life Cycle | Economic Value | Folk Medicine | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alhagi maurorum Medik. (Syn. Alhagi graecorum Boiss.) (Eng. Camelthorn, camelthorn-bush, caspian manna, persian mannaplant) (Arb. Shwaika, agool, heidj) | H/S | He/Na | P | Med, EOs, Biof | (+) (Infusion of plant or plant juice used to treat worm infestations, cataract, jaundicem migraine, arthritis, constipation) (“R”: Green “R” boiled and taken as tea with lime, as an aphrodisiac and to treat kidney disease) (UAE) | [113] |

| 2 | Lotus halophilus Boiss. and Spruner (Eng. Greater bird’s foot trefoi) (Arb. Horbeith “hurbuth”, garn al ghazal, ‘asheb al ghanem) | V!/H | Th | A/P | Med, Fod, Forg, EOs, Lands | (+) (Qatar: as tonic and sedative) | [79,89] |

| 3 | Medicago polymorpha L. (Eng. California burclover, toothed bur clover, toothed medick, burr medic) | F/W | Th | A | Med *, Fod, Forg, EOs, Eco, Lands | (+) (India: for medicinal purposes for skin plagues and dysentery) (Bolivia: for medicinal purposes since 16 century) (Italy: for treating rheumatic pains, wounds and still used until today) | [115] |

| 4 | Medicago sativa L. (Eng. Alfalfa, lucerne) | H | He | P | Med *, Forg *, EOs, Eco | (+) (Great therapeutic benefits) (Used for boosting energy levels) | [116] |

| 5 | Rhynchosia minima (L.) DC. (Eng. least snout-bean, burn-mouth-vine and jumby bean) (Arb. Baql) | V/H | Ch | P | Med, EOs | (+) (Saudi Arabia: Used as abortive) (UAE) | [116,117] |

| 6 | Tephrosia persica Boiss. (Syn. Tephrosia apollinea (Delile) DC.) (Arb. Dhafra, omayye, nafal) | H/S | Ch | P | Med, Arom, Eos * | (+) (“L”: Boiled with water used as eardrops for earache + “Bk”: Powdered and mixed with water put into camel’s ears to remove ticks + “L”: Powdered, heated and mixed as a paste with water and/or salt and applied on wounds and fractures to relieve pain) (UAE) | [118] |

| 7 | Trigonella hamosa L. (Eng. Branched fenugreek, egyptian fenugreek) (Arb. Nafal, qutifa, qirqas, darjal, eshb al-malik, qurt) | H | Th | A | Med, Forg, Flav, EOs | (+) | [79] |

| 8 | Ononis sicula Guss. | H | Th | A | EOs | . | [119] |

| 9 | Acacia nilotica (L.) Delile (Syn. Acacia Arabica (Lam.) Willd.) (Eng. Gum arabic tree, babul/kikar, egyptian thorn, sant tree, al-sant, prickly acacia) (Arb. Sunt garath “kurut”, babul, tulh. Fruit: karat) | T | Ph | P | Med *, EOs, Lands | (+) (Pearl drivers used to apply an infusion of fruits to skin after dives) (“L”: Poultice of “L” used to treat joint pains) (Resin mixed with egg-white applied to eyes to treat cararacts) (“L”: Eaten to treat diarrhoea) (“Se”: Soaked in water or milk drunk to treat diabetes) (“Pd”: Smoke from burning “Pds” inhaled for colds) (UAE: Applied to soothe burns. “L”: are pounded into a paste and used a poultice on boils and swellings or applied around boils to draw out the pus) | [120] |

| 10 | Acacia tortilis (Forssk.) Hayne (Eng. Umbrella thorn) (Arb. Samr “samur”, salam) | S/T | Ph | P | Med, Forg, EOs | (+) (Mostly yields resin, used as a gum to heal wounds) | [122] |