What about Dinner? Chemical and Microresidue Analysis Reveals the Function of Late Neolithic Ceramic Pans

Abstract

1. Introduction

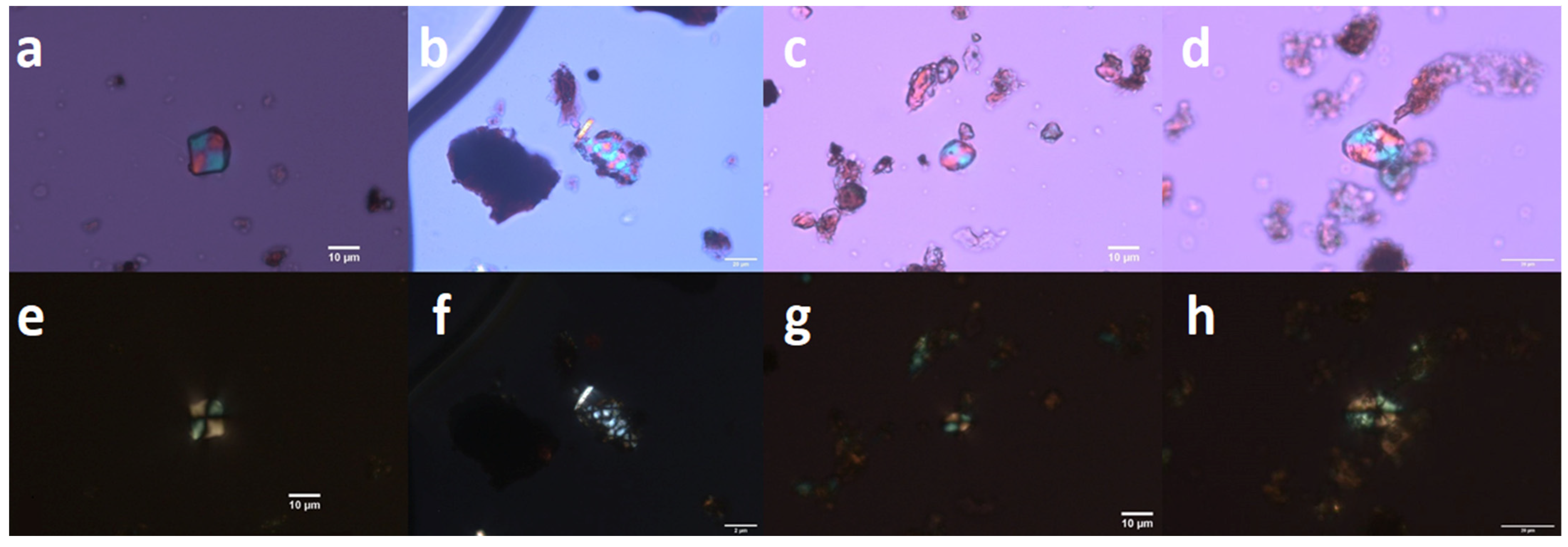

2. Results and Discussion

3. Materials and Methods

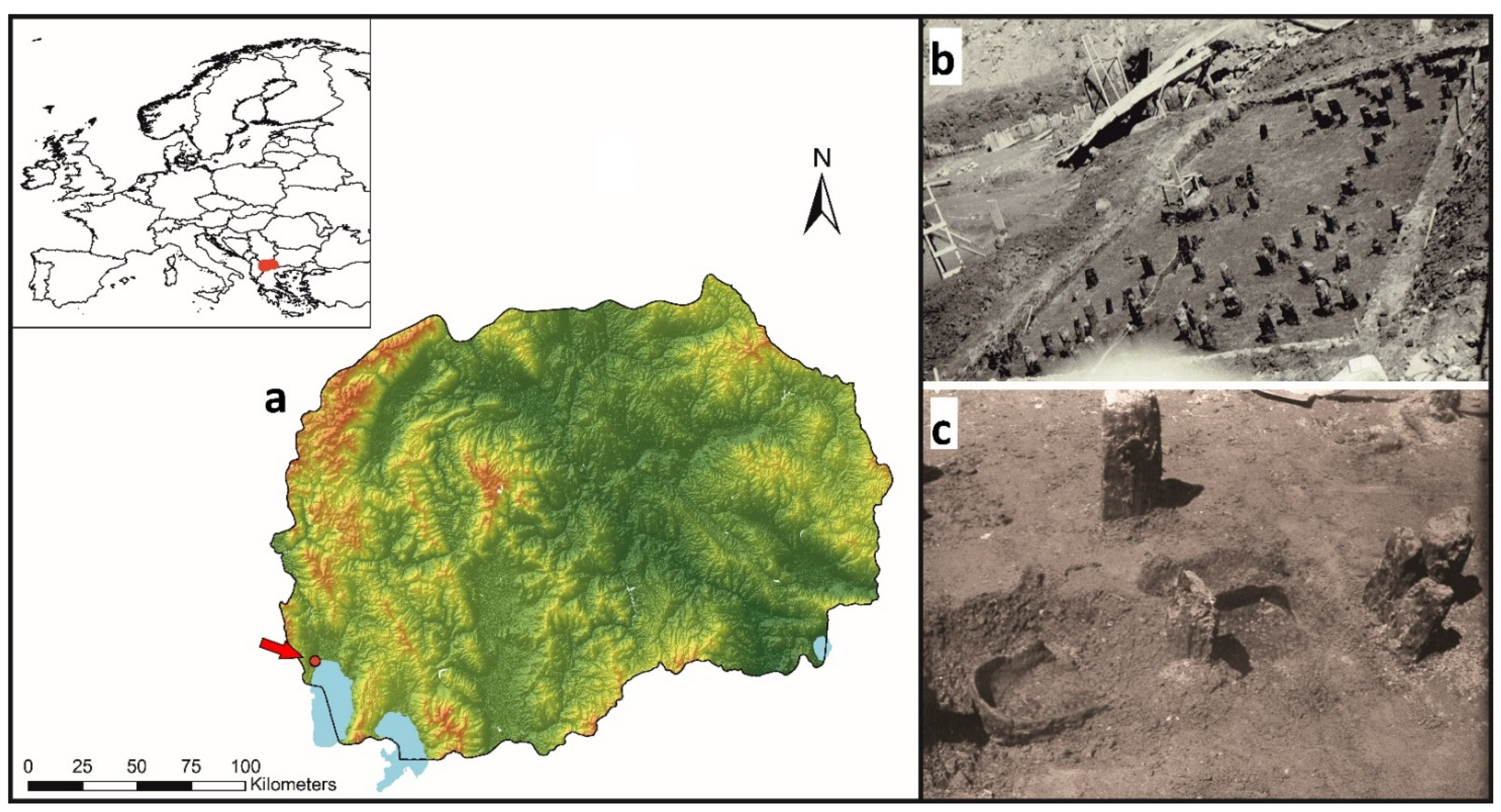

3.1. Archaeological Samples

3.2. Residual Sample Extraction

3.3. Sampling for Starch, Phytoliths, and Non-Pollen Objects

3.4. Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry (GC/MS)

3.5. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Sample Availability

References

- Schiffer, M.B. Formation Processes of the Archaeological Record; University of Utah Press: Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Rösch, M. Pollen analysis of the contents of excavated vessels—Direct archaeobotanical evidence of beverages. Veg. Hist. Archaeobotany 2005, 14, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanus, K.; Baeten, J.; Poblome, J.; Accardo, S.; Degryse, P.; Jacobs, P.; De Vos, D.; Waelkens, M. Wine and olive oil permeation in pitched and non-pitched ceramics: Relation with results from archaeological amphorae from Sagalassos, Turkey. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2009, 36, 900–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preusz, M.; Jan, T.; Vilímek, J.; Enei, F.; Preusz, K. Chemical profile of organic residues from ancient amphoras found in Pyrgi. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2019, 24, 565–573. [Google Scholar]

- Spiteri, C.; Belser, M.; Crispino, A. Preliminary results on content analysis of early bronze age vessels from the site of Castelluccio, Noto, Sicily. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2020, 31, 102533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manhita, A.; Martins, S.; Gomes da Silva, M.; Lopes, M.C.; Barrocas Dias, C. Transporting olive oil in roman times: Chromatographic analysis of dressel 20 amphorae from Pax Julia Civitas, Lusitania. Chromatographia 2020, 83, 1055–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rageot, M.; Mötsch, A.; Schorer, B.; Gutekunst, A.; Patrizi, G.; Zerrer, M.; Cafisso, S.; Fries-Knoblach, J.; Hansen, L.; Tarpini, R.; et al. The dynamics of early celtic consumption practices: A case study of the pottery from the Heuneburg. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rösch, M. Evaluation of honey residues from iron age hill-top sites in southwestern Germany: Implications for local and regional land use and vegetation dynamics. Veg. Hist. Archaeobotany 1999, 8, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ondrkál, F.; Peška, J.; Jagošová, K.; Sokolovská, D.; Kučera, L. The cult-wagon of liptovský hrádok: First evidence of using the urnfield cult-wagons as fat-powered lamps. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2020, 34, 102579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvavadze, E.; Boschian, G.; Chichinadze, M.; Gagoshidze, I.; Gavagnin, K.; Martkoplishvili, I.; Rova, E. Palynological and archaeological evidence for ritual use of wine in the kura-araxes period at aradetis orgora (georgia, caucasus). J. Field Archaeol. 2019, 44, 500–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brami, M.N. The Diffusion of Neolithic Practices from Anatolia to Europe. A Contextual Study of Residential Construction, 8,500–5,500 BC Cal; BAR International Series 2838; BAR Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Beneš, J. Počátky Zemědělství ve Starém Světě: The Origins of Agriculture in the Ancient World; Episteme: České Budějovice, Czech Republic, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Whittle, A.W.R. Europe in the Neolithic: The Creation of New Worlds; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler, C.; Harding, J.; Hofmann, D. The Oxford Handbook of Neolithic Europe; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Matlová, V.; Roffet-Salque, M.; Pavlu, I.; Kyselka, J.; Sedlarova, I.; Filip, V.; Evershed, R.P. Defining pottery use and animal management at the neolithic site of bylany (czech republic). J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2017, 14, 262–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whelton, H.L.; Roffet-Salque, M.; Kotsakis, K.; Urem-Kotsou, D.; Evershed, R.P. Strong bias towards carcass product processing at Neolithic settlements in northern Greece revealed through absorbed lipid residues of archaeological pottery. Quat. Int. 2018, 496, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charters, S.; Evershed, R.P.; Quye, A.; Blinkhorn, P.W.; Reeves, V. Simulation experiments for determining the use of ancient pottery vessels: The behaviour of epicuticular leaf wax during boiling of a leafy vegetable. J. Archaeol. Sci. 1997, 24, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudd, S.N.; Regert, M.; Evershed, R.P. Assessing microbial lipid contributions during laboratory degradations of fats and oils and pure triacylglycerols absorbed in ceramic potsherds. Org. Geochem. 1998, 29, 1345–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregg, M.W.; Slater, G.F. A new method for extraction, isolation and transesterification of free fatty acids from archaeological pottery. Archaeometry 2010, 52, 833–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evershed, R.P.; Arnot, K.I.; Collister, J.; Eglinton, G.; Charters, S. Application of isotope ratio monitoring gas-chromatography mass-spectrometry to the analysis of organic residues of archaeological origin. Analyst 1994, 119, 909–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kučera, L.; Peška, J.; Fojtík, P.; Barták, P.; Kučerová, P.; Pavelka, J.; Komárková, V.; Beneš, J.; Polcerová, L.; Králík, M.; et al. First direct evidence of broomcorn millet (panicum miliaceum) in central Europe. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2019, 11, 4221–4227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oras, E.; Vahur, S.; Isaksson, S.; Kaljurand, I.; Leito, I. MALDI-FT-ICR-MS for archaeological lipid residue analysis. J. Mass Spectrom. 2017, 52, 689–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kučera, L.; Peška, J.; Fojtík, P.; Barták, P.; Sokolovská, D.; Pavelka, J.; Komárková, V.; Beneš, J.; Polcerová, L.; Králík, M.; et al. Determination of milk products in ceramic vessels of corded ware culture from a late eneolithic burial. Molecules 2018, 23, 3247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammann, S.; Cramp, L.J.E. Towards the detection of dietary cereal processing through absorbed lipid biomarkers in archaeological pottery. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2018, 93, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Wang, J.; Rosenberg, D.; Zhao, H.; Lengyel, G.; Nadel, D. Fermented beverage and food storage in 13,000 y-old stone mortars at raqefet cave, Israel: Investigating natufian ritual feasting. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2018, 21, 783–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Wang, J.; Liu, H. The brewing function of the first amphorae in the neolithic yangshao culture, north China. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2020, 12, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanovski, D.; Živaljević, I.; Dimitrijević, V.; Dunne, J.; Evershed, R.P.; Balasse, M.; Dowle, A.; Hendy, J.; McGrath, K.; Fischer, R.; et al. Living off the land: Terrestrial-based diet and dairying in the farming communities of the Neolithic Balkans. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0237608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavelka, J.; Smejda, L.; Hynek, R.; Hrdlickova Kuckova, S. Immunological detection of denatured proteins as a method for rapid identification of food residues on archaeological pottery. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2016, 73, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavelka, J.; Šmejda, L.; Kučková, Š.; Menšík, P. Challenge to molecular archaeology - sediments contaminated by allochthonous animal proteins. J. Liq. Chromatogr. Relat. Technol. 2020, 43, 19–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietra, F.; Baldwin, J.E.; Williams, R.M. Biodiversity and Natural Product Diversity; Elsevier Science: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Casanova, E.; Knowles, T.D.J.; Williams, C.; Crump, M.P.; Evershed, R.P. Practical considerations in high-precision compound-specific radiocarbon dating: Eliminating the effects of solvent and sample cross-contamination on accuracy and precision. Anal. Chem. 2018, 90, 11025–11032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayliss, A.; Marshall, P. Confessions of a serial polygamist: The reality of radiocarbon reproducibility in archaeological samples. Radiocarbon 2019, 61, 1143–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayliss, A.; van der Plicht, J.; Bronk, R.C.; McCormac, F.G.; Healy, F.; Whittle, A. Towards generational time-scales: The quantitative interpretation of archaeological chronologies. In Gathering Time: Dating the Early Neolithic Enclosures of Southern Britain and Ireland; Whittle, A., Healy, F., Bayliss, A., Eds.; Oxbow Books: Oxford, UK, 2011; pp. 17–59. [Google Scholar]

- Philippsen, B. Hard water and old food. The freshwater reservoir effect in radiocarbon dating of food residues on pottery. Doc. Praehist. 2015, 42, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wagner, B.; Reicherter, K.; Daut, G.; Wessels, M.; Matzinger, A.; Schwalb, A.; Spirkovski, Z.; Sanxhaku, M. The potential of lake ohrid for long-term palaeoenvironmental reconstructions. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2008, 259, 341–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beavan-Athfield, N.; McFadgen, B.; Sparks, R. Environmental influences on dietary carbon and 14C ages in modern rats and other species. Radiocarbon 2001, 43, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bronk Ramsey, C. Bayesian analysis of radiocarbon dates. Radiocarbon 2009, 51, 337–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimer, P.J.; Austin, W.E.N.; Bard, E.; Bayliss, A.; Blackwell, P.G.; Bronk Ramsey, C.; Butzin, M.; Cheng, H.; Edwards, R.L.; Friedrich, M.; et al. The intcal20 northern hemisphere radiocarbon age calibration curve (0–55 cal kBP). Radiocarbon 2020, 62, 725–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozarth, S.R. Classification of opal phytoliths formed in selected dicotyledons native to the great plains. In Phytolith Systematics; Springer: Boston, UK, 1992; pp. 193–214. [Google Scholar]

- Neumann, K.; Strömberg, C.A.E.; Ball, T.; Albert, M.R.; Vrydaghs, L.; Cumming, L.S. International code for phytolith nomenclature (ICPN) 2.0. Ann. Bot. 2019, 124, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichert, E.T. The Differentiation and Specificity of Starches in Relation, to Genera, Species; Carnegie Institution of Washington: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Velíšek, J.; Koplik, R.; Cejpek, K. The Chemistry of Food; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Henry, A.G.; Hudson, H.F.; Piperno, D.R. Changes in starch grain morphologies from cooking. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2009, 36, 915–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowther, A. The differential survival of native starch during cooking and implications for archaeological analyses: A review. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2012, 4, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, H. Starch residues on museum artefacts: Implications for determining tool use. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2007, 34, 1752–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.Y.; Yu, J.C.; Lü, H.Y.; Cui, T.X.; Guo, J.N.; Ge, Q.S. Starch grain analysis reveals function of grinding stone tools at Shangzhai site, Beijing. Sci. China Ser. D Earth Sci. 2009, 52, 1164–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L. A long process towards agriculture in the middle yellow river valley, China: Evidence from macro- and micro-botanical remains. J. Indo-Pac. Archaeol. 2015, 35, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucchi, A.; Burguet-Coca, A.; Expósito, I.; Aceituno Bocanegra, F.J.; Lozano, M. Comparisons between methods for analyzing dental calculus samples from El Mirador cave (Sierra de Atapuerca, Spain). Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2019, 11, 6305–6314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, J.; Perry, L.; Ma, Z.; Wan, Z.; Li, M.; Diao, X.; Lu, H. From the modern to the archaeological: Starch grains from millets and their wild relatives in China. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2012, 39, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Kealhofer, L.; Chen, X.; Ji, P. A broad-spectrum subsistence economy in neolithic inner mongolia, China: Evidence from grinding stones. Holocene 2014, 24, 726–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentini, Q.; Favaretto, S.; Miola, A.; Sostizzo, I. Unknown and known quaternary non pollen palynomorphs from sediments analysed in the Laboratory of Palynology, University of Padua Italy. Palyno-Bulletin 2006, 2, 65–66. [Google Scholar]

- Kvavadze, E. Non pollen palynomorphs as an important object for solution of archaeological problems. In Proceedings of 3th International Workshop on Quaternary Non-Pollen Palynomorphs; Maritan, M., Miola, A., Eds.; University of Padova Press: Padova, Italy, 2008; pp. 34–37. [Google Scholar]

- Kvavadze, E.; Kakhiani, K. Palynology of the paravani burial mound (early bronze age, Georgia). Veg. Hist. Archaeobot. 2010, 19, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanassiou, C.G.; Phillips, T.W.; Wakil, W. Biology and control of the khapra beetle, trogoderma granarium, a major quarantine threat to global food security. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2019, 64, 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kislev, M.E.; Nadel, D.; Carmi, I. Epipalaeolithic (19000 BP) cereal and fruit diet at ohalo II, sea of galiee, Izrael. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 1992, 73, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubiak-Martens, L. The plant food component of the diet at the late Mesolithic (Ertebolle) settlement at Tybrind Vig, Denmark. Veg. Hist. Archaeobot. 1999, 8, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranguren, B.; Becattini, R.; Lippi, M.M.; Revedin, A. Grinding flour in upper Palaeolithic Europe (25 000 years bp). Antiquity 2007, 81, 845–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revedin, A.; Aranguren, B.; Becattini, R.; Longo, L.; Marconi, E.; Lippi, M.M.; Skakun, N.; Sinitsyn, A.; Spiridonova, E.; Svoboda, J. Thirty thousand-year-old evidence of plant food processing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 18815–18819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, J.F. Cattails (typha spp.)—Weed problem or potential crop? Econ. Bot. 1975, 29, 7–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gott, B. Cumbungi, Typha species: A staple aboriginal food in southern Australia. AAS 1999, 1, 33–49. [Google Scholar]

- Vencl, S. Žaludy jako potravina: k poznání významu sběru pro výživu v pravěku. Archeol. Rozhl. 1985, 37, 516–565. [Google Scholar]

- Vencl, S. Acorns as food: Again. Památ. Archeol. 1996, 87, 95–111. [Google Scholar]

- De Hingh, A.E. Food Production and Food Procurement in the Bronze Age and Early Iron Age (2000-500 BC). Ph.D. Thesis, Leiden University, Leiden, The Netherlands, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- АКRM. Arheoloska Karta Na Republika Makedonija Tom II (The Archaeological Map of The Republic of Macedonia); Makedonska Akademija Na Naukite I Umetnostite: Skopje, North Macedonia, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Kuzman, P. Praistoriskite palafitni naselbi vo Makedonija. In Makedonija, Mileniumski-Kulturno Istorsiki Fakti I; Kuzman, P., Dimitrova, E., Donev, J., Eds.; Media Print Makedonija and Universitet Evro-Balkan: Skopje, North Macedonia, 2013; pp. 298–429. [Google Scholar]

- Todoroska, V. The pile dwelling settlement “Ustie na Drim”. In Neolithic in Macedonia: New Knowledge and Perspectives, Centre for Prehistoric Research; Naumov, G., Fidanovski, L., Eds.; Magnasken: Skopje, North Macedonia, 2016; pp. 41–53. [Google Scholar]

- Benac, А. Оhridsko jezero i južna Pelagonija. Arheološki odkritija na počvata na Makedonija. MANU 2008, 17, 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Sanev, V.; Stamenova, M. Neolitskata naselba “Stranata” vo selo Angelci. In Zbornik na trudovi; Dukovski, V., Pavlovski, V., Lazarev, J., Dudeski, L., Eds.; Mašinski fakultet: Skopje, North Macedonia, 1989; pp. 9–63. [Google Scholar]

- Sinadinovski, P. Docniot Neolit Vo Republika Makedonija. Master’s Thesis, St. Cyril’s Metodi University, Skopje, North Macedonia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Léra, P. Vendbanimi i neolitit të vonë në Barç (Faza Barç II)/L’habitat du Néolithique récent à Barç (La phase Barç II). Iliria 1987, 17, 25–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benac, A. Praistorija jugoslavenskih zemalja II, Neolitsko doba; Akademija nauke i umetnosti Bosne i Hercegovine: Sarajevo, North Macedonia, 1979; pp. 363–472. [Google Scholar]

- Tsirtsoni, Z. Chapter 1:The chronological framework in Greece and Bulgaria between the late 6th and the early 3rd millennium BC, and the “Balkans 4000” project. In The Human Face of Radiocarbon: Reassessing Chronology in Prehistoric Greece and Bulgaria, 5000-3000 Cal BC; MOM Éditions: Lyon, France, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coil, J.; Korstanje, M.A.; Archer, S.; Hastorf, C.A. Laboratory goals and considerations for multiple microfossil extraction in archaeology. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2003, 30, 991–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Yang, X.; Ge, Q.; Ren, X.; Wan, Z. Starch grains analysis of stone knives from Changning site, Qinghai Province, Northwest China. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2013, 40, 1667–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messner, T.C.; Dickau, R.; Harbison, J. Starch grain analysis: Methodology and applications in the northeast. In Current Northeast Paleoethnobotany II; Hart, J.P., Ed.; University of the State of New York, State Education Department: Albany, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 111–128. [Google Scholar]

- Pagán-Jiménez, J.R.; Rodríguez-Ramos, R.; Reid, B.A.; van den Bel, M.; Hofman, C.L. Early dispersals of maize and other food plants into the Southern Caribbean and Northeastern South America. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2015, 123, 231–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavelka, J.; Kovačiková, L.; Šmejda, L. Détermination d’espèces d’animaux domestiques à partir d’un échantillon néolithique grâce au test Elisa. Comptes Rendus Palevol 2011, 10, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinh, T.T.N.; Thompson, L.D.; Galyean, M.L.; Brooks, J.C.; Patterson, K.Y.; Boylan, L.M. Cholesterol content and methods for cholesterol determination in meat and poultry. Compr. Rev. Food. Sci Food Saf. 2011, 10, 269–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Artefact | Sample | Concentration of Cholesterol (mg/g) | Phytoliths and Non-Pollen Objects | Starch | Position of Sample in Ceramic Pan |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KE1 | 1 | 0.05 | - | - | pit (residue) |

| KE1 | 2 | 0.08 | - | - | pit (ceramic under KE1-1) |

| KE1 | 3 | 0.00 | - | - | edge, the reference sample |

| KE1 | SP1 | - | positive | positive | pit |

| KE1 | SP2 | - | - | positive | edge |

| KE2 | 1 | 0.03 | - | - | pit (residue) |

| KE2 | 2 | 0.01 | - | - | pit (ceramic under KE2-1) |

| KE2 | 3 | 0.92 | - | - | pit (residue) |

| KE2 | 4 | 0.04 | - | - | pit (ceramic under KE2-3) |

| KE2 | 5 | 0.00 | - | - | bottom, the reference sample |

| KE2 | 6 | 0.00 | - | - | inner surface (organic temper) |

| KE2 | 7 | 0.01 | - | - | surface (the reference sample) |

| KE2 | SP3 | - | - | negative | pit |

| KE2 | SP4 | - | - | - | pit |

| KE2 | SP5 | - | - | positive | edge |

| KE3 | 1 | 0.02 | - | - | inner surface (close bottom part, baked mass) |

| KE3 | 2 | 0.13 | - | - | inner surface (under edge, baked mass) |

| KE3 | 3 | 0.01 | - | - | inner surface (ceramic under KE3-1) |

| KE3 | 4 | 0.34 | - | - | inner surface (ceramic under KE3-2) |

| KE3 | 5 | 0.04 | - | - | edge (the reference sample) |

| KE3 | SP6 | - | positive | positive | pit |

| KE3 | SP7 | - | negative | pit | |

| KE4 | 1 | 0.44 | - | - | inner edge (close bottom part, baked layer) |

| KE4 | 2 | 0.66 | - | - | inner edge (close upper part, baked layer) |

| KE4 | 3 | 0.19 | - | - | inner edge (ceramic under KE4-1) |

| KE4 | 4 | 0.46 | - | - | inner edge (ceramic under KE4-2) |

| KE4 | 5 | 0.01 | - | - | edge (the reference sample) |

| KE4 | SP8 | - | positive | positive | pit |

| KE4 | SP9 | - | - | positive | pit |

| KE5 | 1 | 0.09 | - | - | inner edge (close bottom part, thin layer) |

| KE5 | 2 | 0.24 | - | - | inner edge (close to KE5-1) |

| KE5 | 3 | 0.02 | - | - | inner edge (ceramic under KE5-1) |

| KE5 | 4 | 0.16 | - | - | inner edge (ceramic under KE5-2) |

| KE5 | 5 | 0.01 | - | - | edge (the reference sample) |

| KE6 | 1 | 0.00 | - | - | wall (close upper part, baked mass) |

| KE6 | 2 | 0.02 | - | - | wall (close to KE6-1 |

| KE6 | 3 | 0.00 | - | - | edge (the reference sample) |

| KE7 | 1 | 0.17 | - | - | organic residue (taken before conservation) |

| Sample | Lab. Code | BP Age | cal BC 68.4% | cal BC 95.4% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KE 4-2 | UGAMS-49232 | 7370 ± 30 | 6341–6313 (13.2%) | 6369–6297 (22.6%) |

| 6260–6216 (31.3%) | 6269–8209 (35.6%) | |||

| 6142–6092 (23.7%) | 6198–6085 (37.2%) | |||

| KE 7 | UGAMS-49233 | 7480 ± 25 | 6411–6366 (36.3%) | 6422–6332 (53.3%) |

| 6308–6265 (32.0%) | 6319–6319 (42.1%) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Beneš, J.; Todoroska, V.; Budilová, K.; Kovárník, J.; Pavelka, J.; Atanasoska, N.; Bumerl, J.; Florenzano, A.; Majerovičová, T.; Vondrovský, V.; et al. What about Dinner? Chemical and Microresidue Analysis Reveals the Function of Late Neolithic Ceramic Pans. Molecules 2021, 26, 3391. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26113391

Beneš J, Todoroska V, Budilová K, Kovárník J, Pavelka J, Atanasoska N, Bumerl J, Florenzano A, Majerovičová T, Vondrovský V, et al. What about Dinner? Chemical and Microresidue Analysis Reveals the Function of Late Neolithic Ceramic Pans. Molecules. 2021; 26(11):3391. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26113391

Chicago/Turabian StyleBeneš, Jaromír, Valentina Todoroska, Kristýna Budilová, Jaromír Kovárník, Jaroslav Pavelka, Nevenka Atanasoska, Jiří Bumerl, Assunta Florenzano, Tereza Majerovičová, Václav Vondrovský, and et al. 2021. "What about Dinner? Chemical and Microresidue Analysis Reveals the Function of Late Neolithic Ceramic Pans" Molecules 26, no. 11: 3391. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26113391

APA StyleBeneš, J., Todoroska, V., Budilová, K., Kovárník, J., Pavelka, J., Atanasoska, N., Bumerl, J., Florenzano, A., Majerovičová, T., Vondrovský, V., Ptáková, M., Bednář, P., Richtera, L., & Kučera, L. (2021). What about Dinner? Chemical and Microresidue Analysis Reveals the Function of Late Neolithic Ceramic Pans. Molecules, 26(11), 3391. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26113391