Sulfide (Na2S) and Polysulfide (Na2S2) Interacting with Doxycycline Produce/Scavenge Superoxide and Hydroxyl Radicals and Induce/Inhibit DNA Cleavage

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

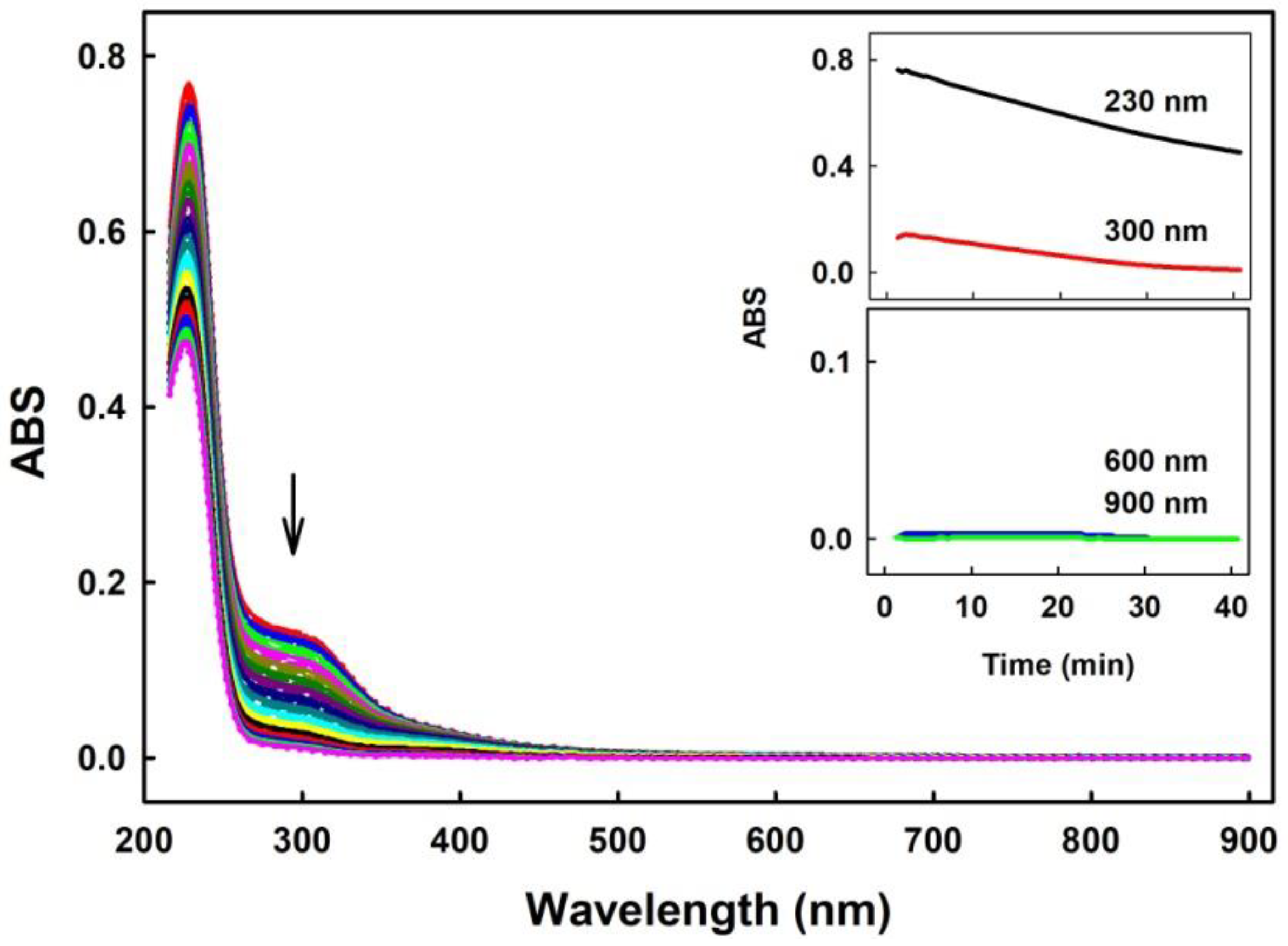

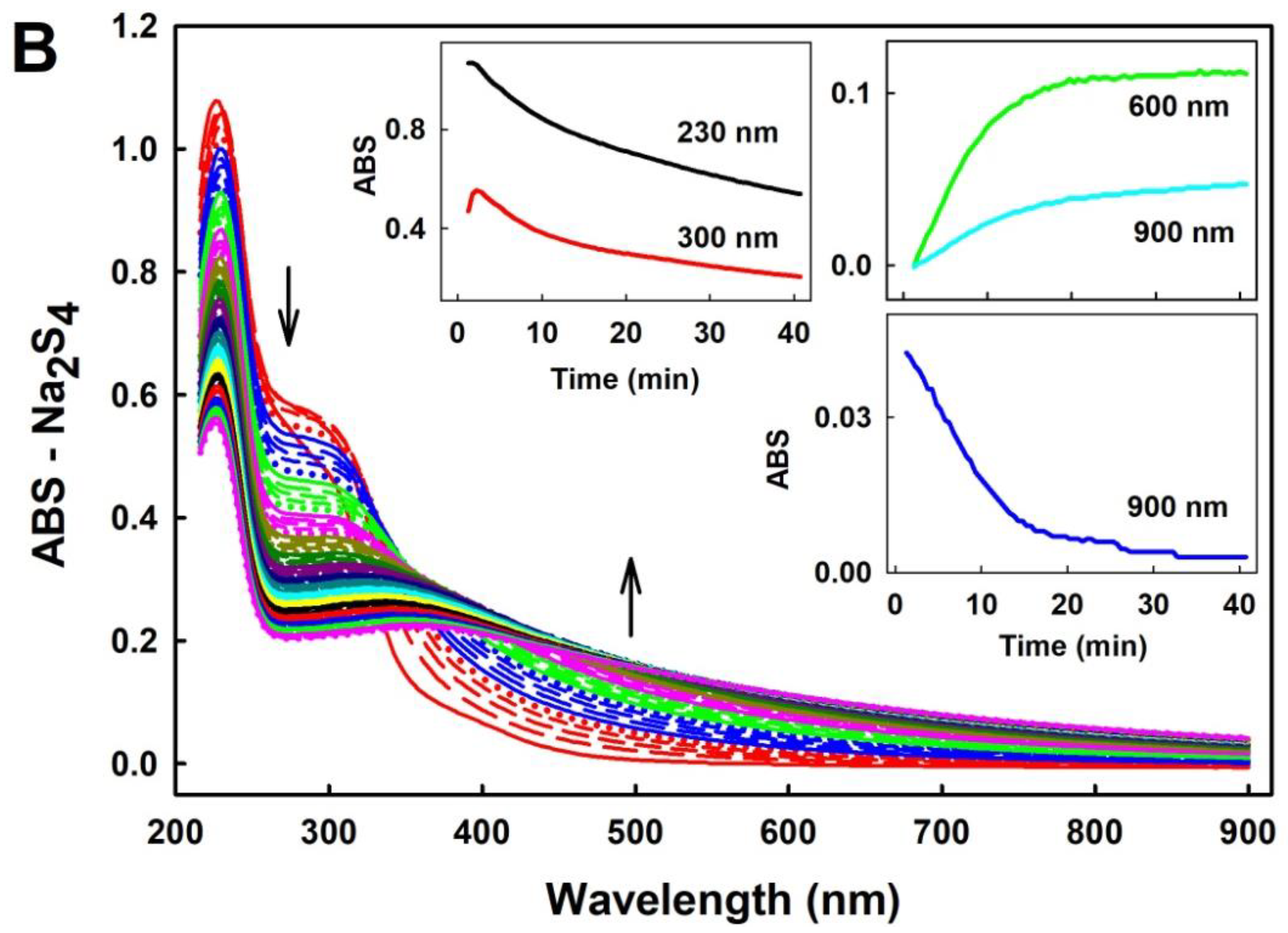

2.1. Practical Work with Polysulfides

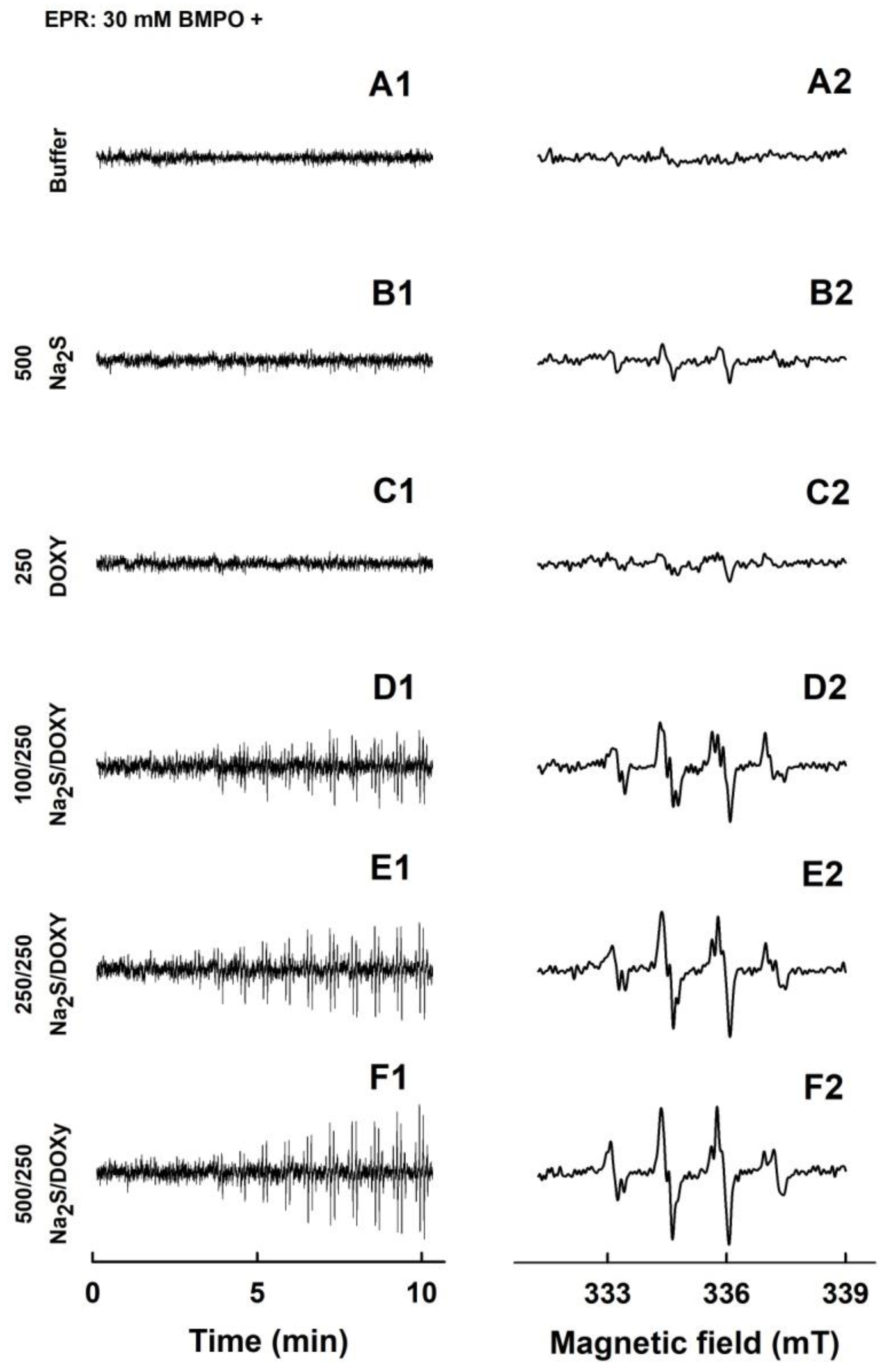

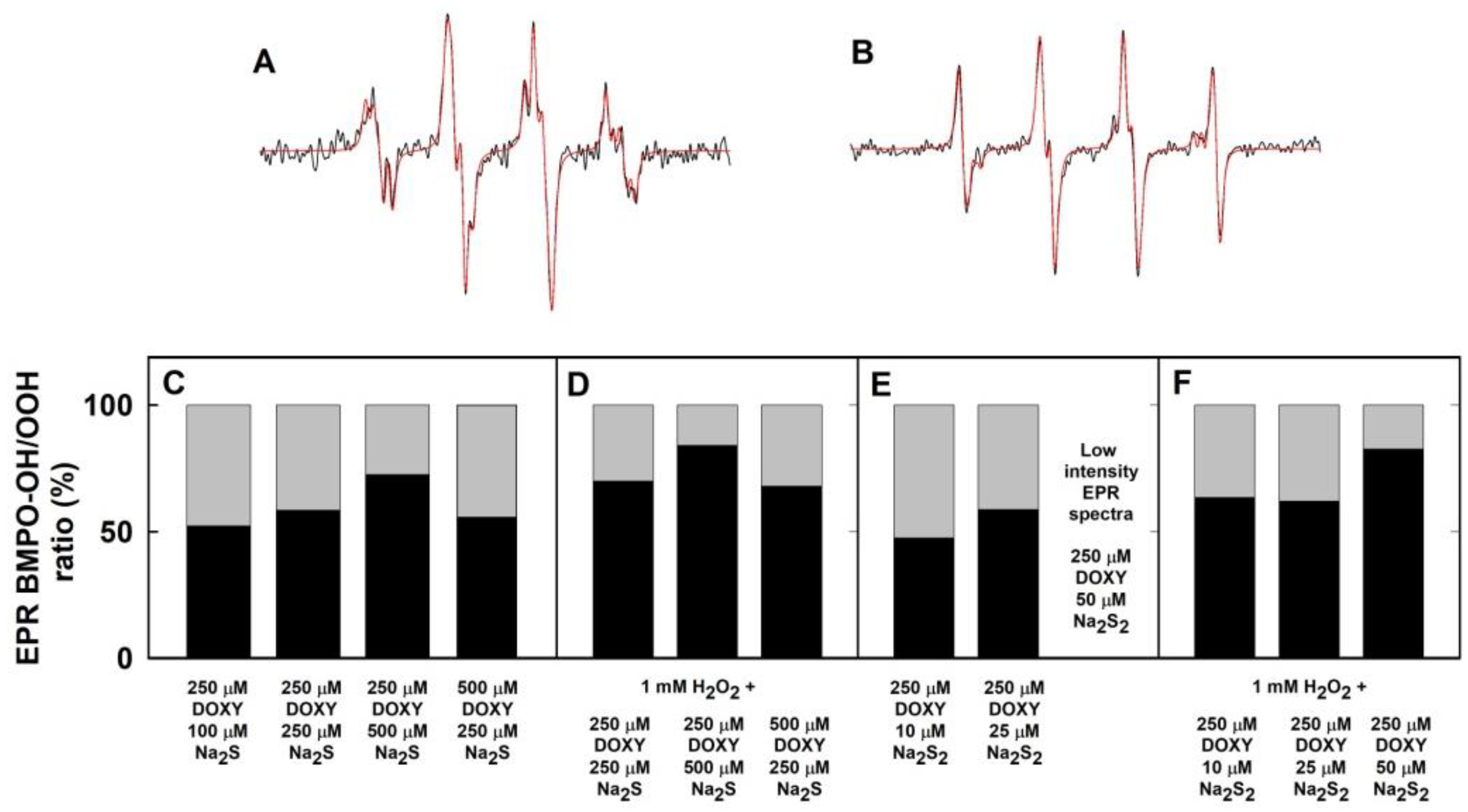

2.2. Formation of the O2•− and •OH Radicals by Na2S or Na2S2 Interacting with DOXY

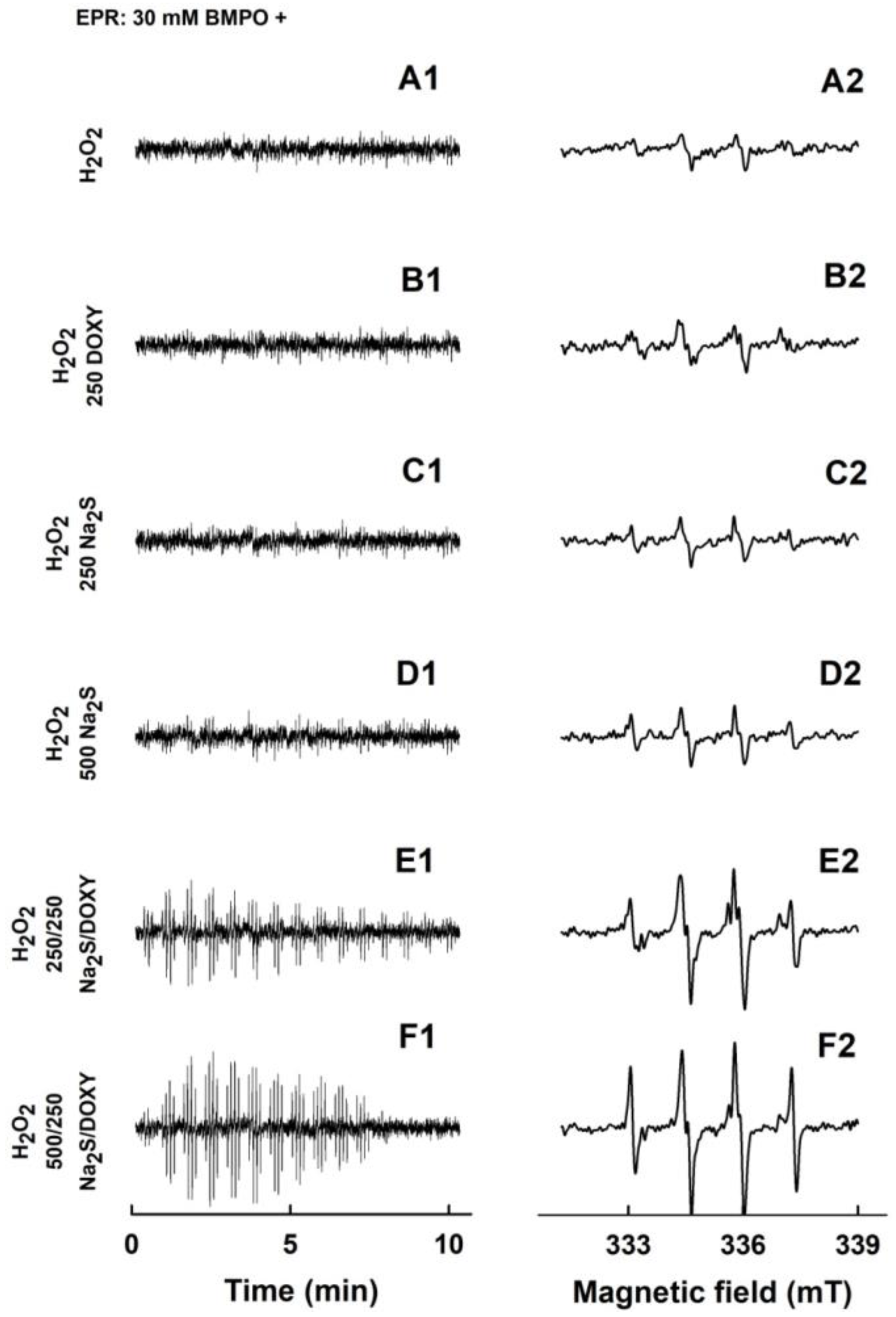

2.3. Formation of the O2•− and •OH Radicals by Na2S Interacting with DOXY in the Presence of Hydrogen Peroxide (H2O2)

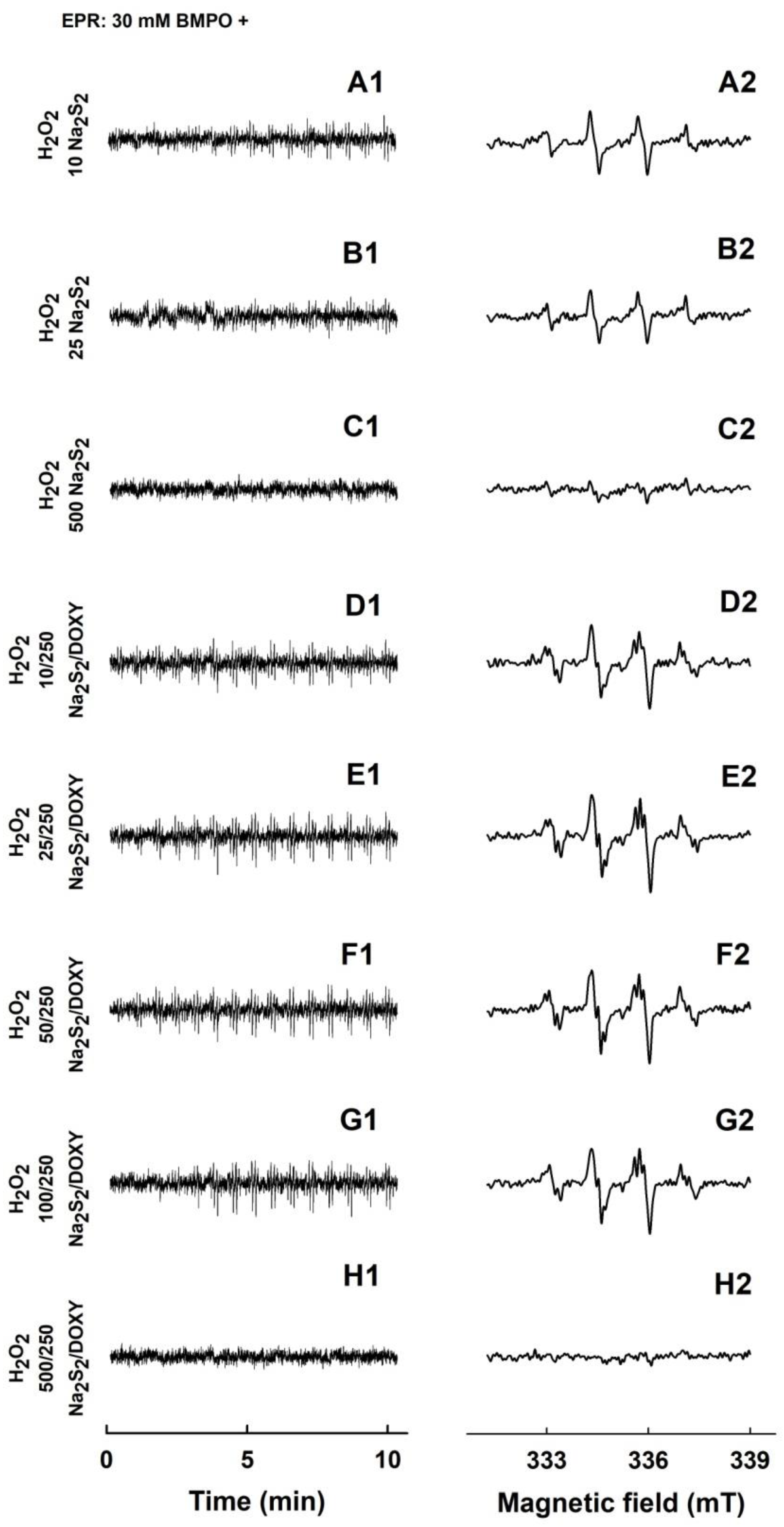

2.4. Formation of the O2•− and •OH Radicals by Na2S2 Interacting with DOXY in the Presence of H2O2

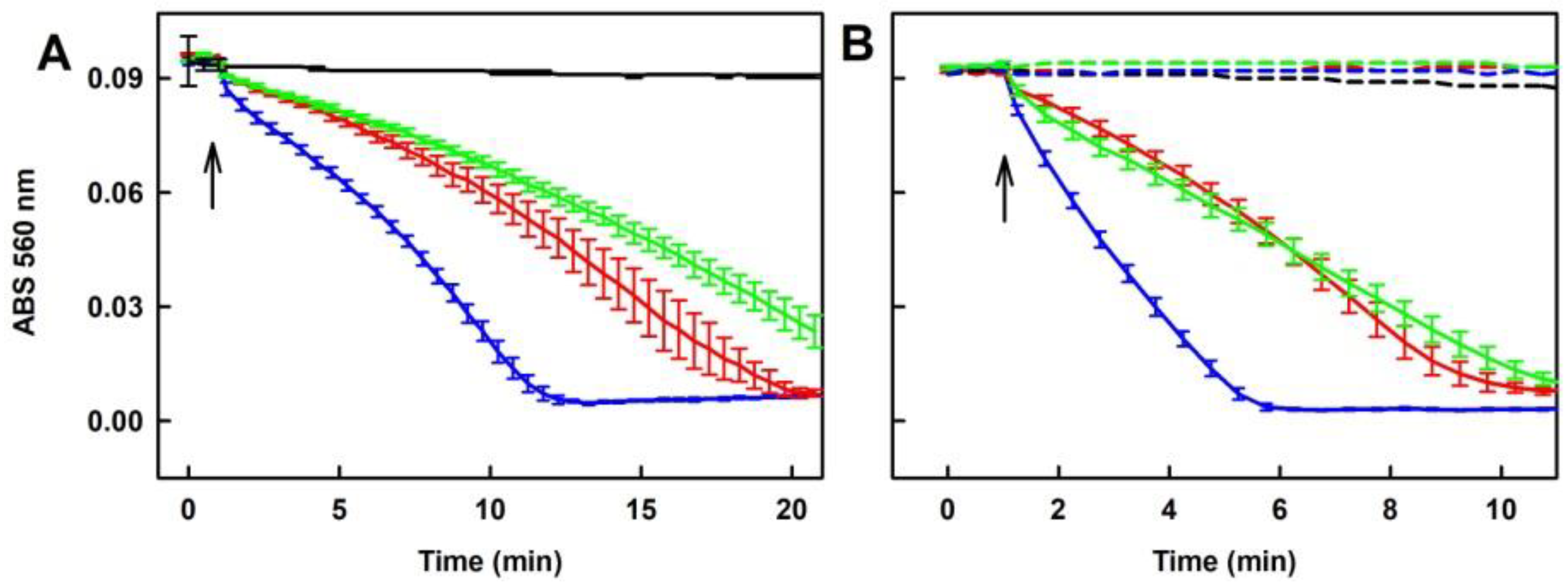

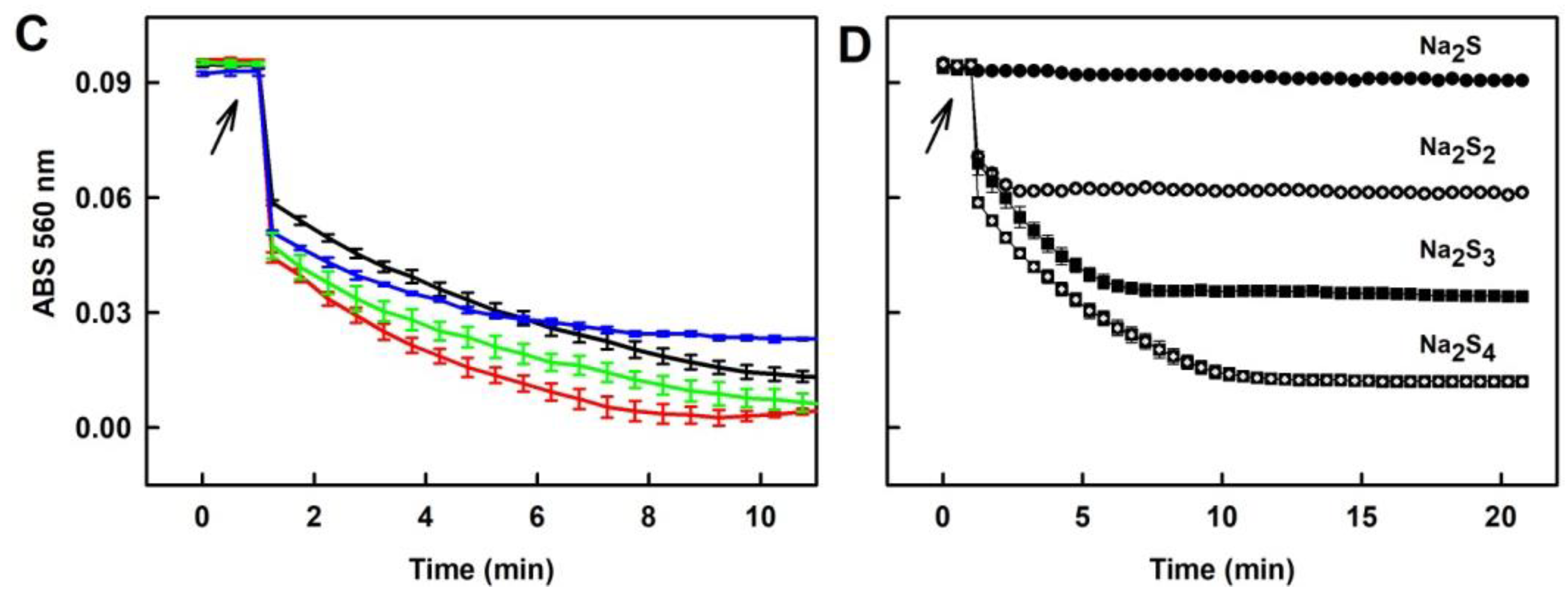

2.5. Potency of Compounds to Reduce the •cPTIO Radical

2.5.1. Tetracyclines, but neither FUSA nor NORF, Reduce the •cPTIO Radical in the Presence of Na2S

2.5.2. Ability of the Polysulfide/Tetracyclines Mixture to Reduce the •cPTIO Radical

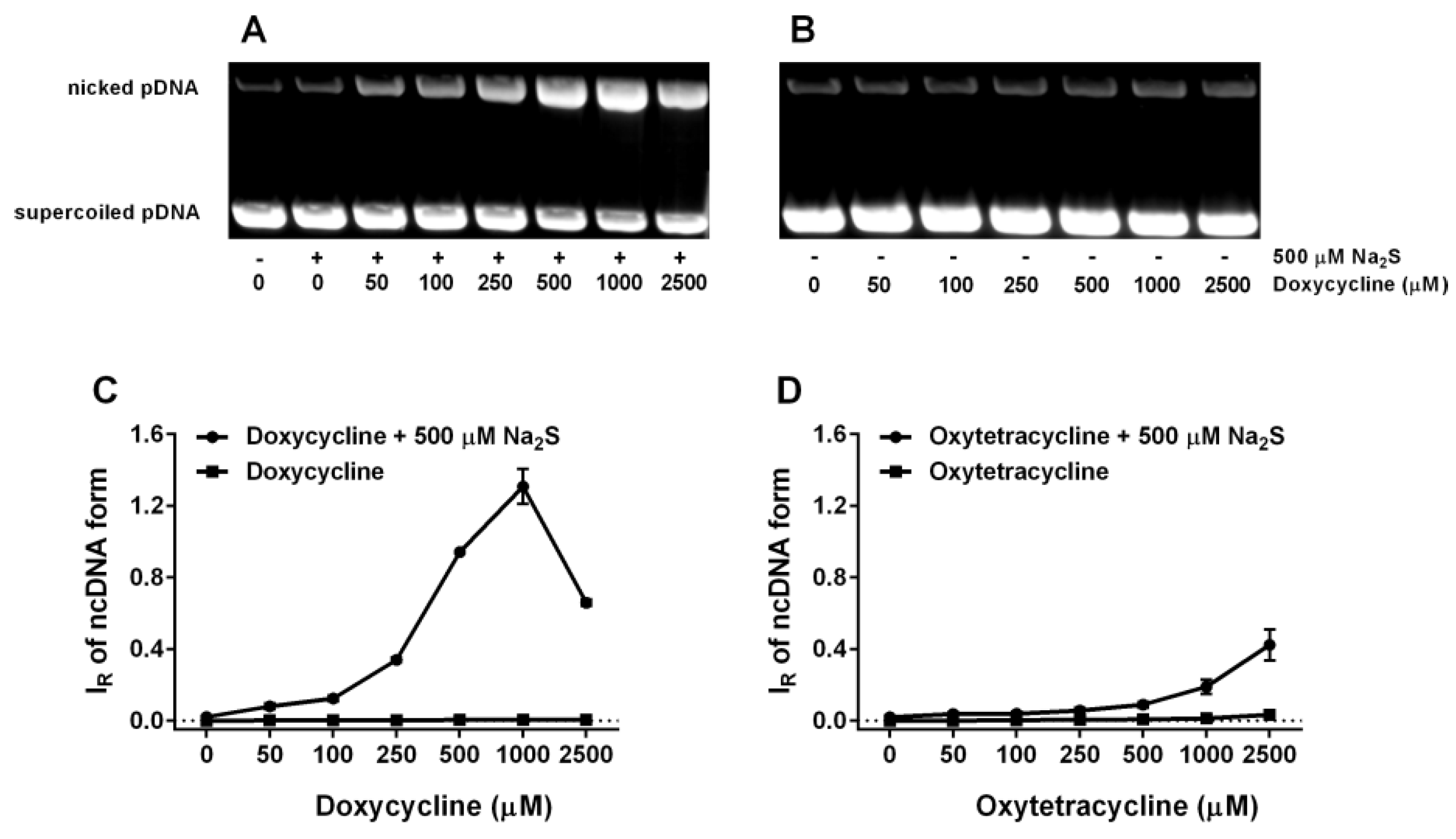

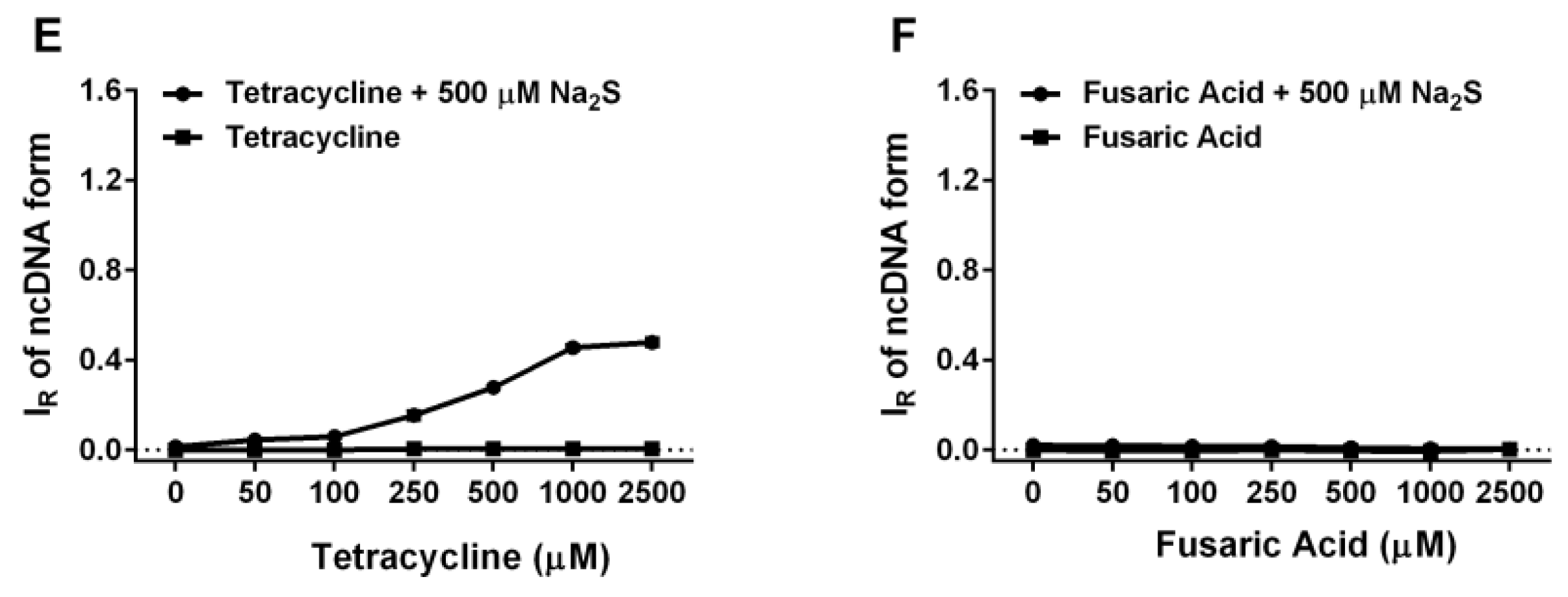

2.6. Tetracyclines Cleave pDNA in the Presence of Na2S, but Inhibit pDNA Cleavage Induced by Polysulfides

2.7. Na2S Did Not Modify Inhibitory Effect of DOXY on Growth of Escherichia Coli Cells

3. Discussion

3.1. Practical Use of Polysulfides versus Na2S

3.2. Interaction of Na2S and Polysulfides with Tetracyclines

3.3. Possible Biological Consequences of the Na2S and Polysulfides Interacting with Tetracyclines

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemicals

4.2. EPR of the •BMPO-adducts

4.3. UV-VIS of •cPTIO

4.4. pDNA Cleavage Assay

4.5. Bacterial Growth Measurement

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, R. Physiological implications of hydrogen sulfide: A whiff exploration that blossomed. Physiol. Rev. 2012, 92, 791–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimura, H. Hydrogen Sulfide and Polysulfide Signaling. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2017, 27, 619–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szabo, C.; Papapetropoulos, A. International union of basic and clinical pharmacology. CII: Pharmacological modulation of H2S levels: H2S donors and H2S biosynthesis inhibitors. Pharmacol. Rev. 2017, 69, 497–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whiteman, M.; Armstrong, J.S.; Chu, S.H.; Jia-Ling, S.; Wong, B.S.; Cheung, N.S.; Halliwell, B.; Moore, P.K. The novel neuromodulator hydrogen sulfide: An endogenous peroxynitrite ‘scavenger’? J. Neurochem. 2004, 90, 765–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiteman, M.; Cheung, N.S.; Zhu, Y.Z.; Chu, S.H.; Siau, J.L.; Wong, B.S.; Armstrong, J.S.; Moore, P.K. Hydrogen sulphide: A novel inhibitor of hypochlorous acid-mediated oxidative damage in the brain? Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005, 326, 794–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staško, A.; Brezová, V.; Zalibera, M.; Biskupič, S.; Ondriaš, K. Electron transfer: A primary step in the reactions of sodium hydrosulphide, an H2S/HS− donor. Free Radic. Res. 2009, 43, 581–593. [Google Scholar]

- Olas, B. Hydrogen sulfide in hemostasis: Friend or foe? Chem. Biol. Interact. 2014, 217, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misak, A.; Grman, M.; Bacova, Z.; Rezuchova, I.; Hudecova, S.; Ondriasova, E.; Krizanova, O.; Brezova, V.; Chovanec, M.; Ondrias, K. Polysulfides and products of H2S/S-nitrosoglutathione in comparison to H2S, glutathione and antioxidant Trolox are potent scavengers of superoxide anion radical and produce hydroxyl radical by decomposition of H2O2. Nitric Oxide 2018, 76, 136–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viry, E.; Anwar, A.; Kirsch, G.; Jacob, C.; Diederich, M.; Bagrel, D. Antiproliferative effect of natural tetrasulfides in human breast cancer cells is mediated through the inhibition of the cell division cycle 25 phosphatases. Int. J. Oncol. 2011, 38, 1103–1111. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Szabo, C.; Coletta, C.; Chao, C.; Módis, K.; Szczesny, B.; Papapetropoulos, A.; Hellmich, M.R. Tumor-derived hydrogen sulfide, produced by cystathionine-β-synthase, stimulates bioenergetics, cell proliferation, and angiogenesis in colon cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 12474–12479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Hu, Q.; Liu, X.; Pan, L.; Xiong, Q.; Zhu, Y.Z. Hydrogen sulfide protects against apoptosis under oxidative stress through SIRT1 pathway in H9c2 cardiomyocytes. Nitric Oxide 2015, 46, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abiko, Y.; Shinkai, Y.; Unoki, T.; Hirose, R.; Uehara, T.; Kumagai, Y. Polysulfide Na2S4 regulates the activation of PTEN/Akt/CREB signaling and cytotoxicity mediated by 1,4-naphthoquinone through formation of sulfur adducts. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 4814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breza, J., Jr.; Soltysova, A.; Hudecova, S.; Penesova, A.; Szadvari, I.; Babula, P.; Chovancova, B.; Lencesova, L.; Pos, O.; Breza, J.; et al. Endogenous H2S producing enzymes are involved in apoptosis induction in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ondrias, K.; Stasko, A.; Cacanyiova, S.; Sulova, Z.; Krizanova, O.; Kristek, F.; Malekova, L.; Knezl, V.; Breier, A. H2S and HS– donor NaHS releases nitric oxide from nitrosothiols, metal nitrosyl complex, brain homogenate and murine L1210 leukaemia cells. Pflugers Arch. 2008, 457, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortese-Krott, M.M.; Kuhnle, G.G.C.; Dyson, A.; Fernandez, B.O.; Grman, M.; DuMond, J.F.; Barrow, M.P.; McLeod, G.; Nakagawa, H.; Ondrias, K.; et al. Key bioactive reaction products of the NO/H2S interaction are S/N-hybrid species, polysulfides, and nitroxyl. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, E4651–E4660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, B.D.; Snyder, S.H. H2S: A Novel Gasotransmitter that Signals by Sulfhydration. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2015, 40, 687–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cacanyiova, S.; Berenyiova, A.; Kristek, F.; Drobna, M.; Ondrias, K.; Grman, M. The adaptive role of nitric oxide and hydrogen Sulphide in vasoactive responses of thoracic aorta is triggered already in young spontaneously hypertensive rats. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2016, 67, 501–512. [Google Scholar]

- Fukuto, J.M.; Ignarro, L.J.; Nagy, P.; Wink, D.A.; Kevil, C.G.; Feelisch, M.; Cortese-Krott, M.M.; Bianco, C.L.; Kumagai, Y.; Hobbs, A.J.; et al. Biological hydropersulfides and related polysulfides—A new concept and perspective in redox biology. FEBS Lett. 2018, 592, 2140–2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, I.; Hawkey, P.M.; Hinton, M. Tetracyclines, molecular and clinical aspects. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 1992, 29, 245–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Cerbo, A.; Palatucci, A.T.; Rubino, V.; Centenaro, S.; Giovazzino, A.; Fraccaroli, E.; Cortese, L.; Ruggiero, G.; Guidetti, G.; Canello, S.; et al. Toxicological Implications and Inflammatory Response in Human Lymphocytes Challenged with Oxytetracycline. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2016, 30, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, A.R.; Rogers Iii, R.S.; Sheridan, P.J. Tetracycline and other tetracycline-derivative staining of the teeth and oral cavity. Int. J. Dermatol. 2004, 43, 709–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, B.; Kumar, Y.; Shrivastav, B.; Sharma, G.N.; Gupta, G.; Dua, K. Current updates on biological and phannacological activities of doxycycline. Panminerva Med. 2018, 60, 36–39. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Luger, A.L.; Sauer, B.; Lorenz, N.I.; Engel, A.L.; Braun, Y.; Voss, M.; Harter, P.N.; Steinbach, J.P.; Ronellenfitsch, M.W. Doxycycline impairs mitochondrial function and protects human glioma cells from hypoxia-induced cell death: Implications of using tet-inducible systems. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortes, A.L.; Gonsalez, S.R.; Rioja, L.S.; Oliveira, S.S.C.; Santos, A.L.S.; Prieto, M.C.; Melo, P.A.; Lara, L.S. Protective outcomes of low-dose doxycycline on renal function of Wistar rats subjected to acute ischemia/reperfusion injury. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2018, 1864, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, T.; Uchiumi, T.; Monji, K.; Yagi, M.; Setoyama, D.; Amamoto, R.; Matsushima, Y.; Shiota, M.; Eto, M.; Kang, D. Doxycycline induces apoptosis via ER stress selectively to cells with a cancer stem cell-like properties: Importance of stem cell plasticity. Oncogenesis 2017, 6, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duivenvoorden, W.C.M.; Popović, S.V.; Lhotük, Š.; Seidlitz, E.; Hirte, H.W.; Tozer, R.G.; Singh, G. Doxycycline decreases tumor burden in a bone metastasis model of human breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2002, 62, 1588–1591. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, W.; Chen, S.; Qin, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, H.; Meng, J.; Huai, L.; Zhang, Q.; Yin, T.; Lei, Y.; et al. Doxycycline inhibits breast cancer EMT and metastasis through PAR-1/NF-κB/miR-17/E-cadherin pathway. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 104855–104866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, C.R.; Dillon, K.M.; Matson, J.B. A review of hydrogen sulfide (H2S) donors: Chemistry and potential therapeutic applications. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2018, 149, 110–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Daim, M.M.; Ghazy, E.W. Effects of Nigella sativa oil and ascorbic acid against oxytetracycline-induced hepato-renal toxicity in rabbits. Iran. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2015, 18, 221–227. [Google Scholar]

- Olas, B. Hydrogen Sulfide as a “Double-Faced” Compound: One with Pro- and Antioxidant Effect. Adv. Clin. Chem. 2017, 78, 187–196. [Google Scholar]

- Riba, A.; Deres, L.; Eros, K.; Szabo, A.; Magyar, K.; Sumegi, B.; Toth, K.; Halmosi, R.; Szabados, E. Doxycycline protects against ROS-induced mitochondrial fragmentation and ISO-induced heart failure. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0175195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hummitzsch, L.; Zitta, K.; Berndt, R.; Kott, M.; Schildhauer, C.; Parczany, K.; Steinfath, M.; Albrecht, M. Doxycycline protects human intestinal cells from hypoxia/reoxygenation injury: Implications from an in-vitro hypoxia model. Exp. Cell Res. 2017, 353, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Acker, H.; Coenye, T. The Role of Reactive Oxygen Species in Antibiotic-Mediated Killing of Bacteria. Trends Microbiol. 2017, 25, 456–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuto, J.M.; Carrington, S.J.; Tantillo, D.J.; Harrison, J.G.; Ignarro, L.J.; Freeman, B.A.; Chen, A.; Wink, D.A. Small molecule signaling agents: The integrated chemistry and biochemistry of nitrogen oxides, oxides of carbon, dioxygen, hydrogen sulfide, and their derived species. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2012, 25, 769–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Radford, M.N.; Yang, C.T.; Chen, W.; Xian, M. Inorganic hydrogen polysulfides: Chemistry, chemical biology and detection. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 176, 616–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, K.R. H2S and polysulfide metabolism: Conventional and unconventional pathways. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2018, 149, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bil-Lula, I.; Krzywonos–Zawadzka, A.; Sawicka, J.; Bialy, D.; Wawrzynska, M.; Wozniak, M.; Sawicki, G. L-NAME improves doxycycline and ML-7 cardioprotection from oxidative stress. Front. Biosci. Landmark 2018, 23, 298–309. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H.; Joseph, J.; Zhang, H.; Karoui, H.; Kalyanaraman, B. Synthesis and biochemical applications of a solid cyclic nitrone spin trap: A relatively superior trap for detecting superoxide anions and glutathiyl radicals. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2001, 31, 599–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, A.K.; McKellar, J.F.; Phillips, G.O.; Reid, A.G. Photochemical oxidation of tetracycline in aqueous solution. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1979, 2, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruk, I.; Lichszteld, K.; Michalska, T.; Nizinkiewicz, K.; Wrońska, J. The extra-weak chemiluminescence generated during oxidation of some tetracycline antibiotics 1. Autoxidation. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 1992, 14, 329–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalska, T.; Lichszteld, K.; Nizinkiewicz, K.; Kruk, I.; Wrońska, J.; Gołȩbiowska, D. The extra-weak chemiluminescence generated during oxidation of some tetracycline antibiotics II. Peroxidation. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 1992, 16, 305–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kładna, A.; Kruk, I.; Michalska, T.; Berczyński, P.; Aboul-Enein, H.Y. Characterization of the superoxide anion radical scavenging activity by tetracycline antibiotics in aprotic media. Luminescence 2011, 26, 611–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, Y.; Liqi, Z.; Jian, L.; Qinghua, Y.; Qian, Y. Doxycycline induces mitophagy and suppresses production of interferon-β in IPEC-J2 cells. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2017, 7, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, A.; Landi, R.; Rubino, V.; Di Cerbo, A.; Giovazzino, A.; Palatucci, A.T.; Centenaro, S.; Guidetti, G.; Canello, S.; Cortese, L.; et al. Oxytetracycline induces DNA damage and epigenetic changes: A possible risk for human and animal health? PeerJ 2017, 2017, e3236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perdue, B.E.; Standiford, H.C. Tetracyclines. In Antimicrobial Therapy and Vaccines; Yu, V.L., Merigan, T.C., Jr., Barriere, S.L., Eds.; Williams & Wilkins: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1999; pp. 981–995. [Google Scholar]

- Welling, P.G.; Koch, P.A.; Lau, C.C.; Craig, W.A. Bioavailability of tetracycline and doxycycline in fasted and nonfasted subjects. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1977, 11, 462–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, F.; Gao, H.; Li, S.S.; An, R.B.; Sun, X.Y.; Kang, B.; Xu, J.J.; Chen, H.Y. A fluorescent: τ-probe: Quantitative imaging of ultra-trace endogenous hydrogen polysulfide in cells and in vivo. Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 5556–5563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.H.; Lu, M.; Hu, L.F.; Wong, P.T.H.; Webb, G.D.; Bian, J.S. Hydrogen sulfide in the mammalian cardiovascular system. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2012, 17, 141–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahler, E.; Sullivan, W.J.; Cass, A.; Braas, D.; York, A.G.; Bensinger, S.J.; Graeber, T.G.; Christofk, H.R. Doxycycline Alters Metabolism and Proliferation of Human Cell Lines. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e64561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamb, R.; Fiorillo, M.; Chadwick, A.; Ozsvari, B.; Reeves, K.J.; Smith, D.L.; Clarke, R.B.; Howell, S.J.; Cappello, A.R.; Martinez-Outschoorn, U.E.; et al. Doxycycline down-regulates DNA-PK and radiosensitizes tumor initiating cells: Implications for more effective radiation therapy. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 14005–14025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pari, L.; Gnanasoundari, M. Influence of naringenin on oxytetracycline mediated oxidative damage in rat liver. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2006, 98, 456–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnanasoundari, M.; Pari, L. Impact of naringenin on oxytetracycline-mediated oxidative damage in kidney of rats. Ren. Fail. 2006, 28, 599–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yonar, M.E. The effect of lycopene on oxytetracycline-induced oxidative stress and immunosuppression in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss, W.). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2012, 32, 994–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Xu, L.; Zhang, F.; Vlashi, E. Doxycycline inhibits the cancer stem cell phenotype and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in breast cancer. Cell Cycle 2017, 16, 737–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, L.; Li, C. Doxycycline inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis of both human papillomavirus positive and negative cervical cancer cell lines. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2016, 94, 526–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Yan, X.; Yu, A.; Wang, Y. Doxycycline synergizes with doxorubicin to inhibit the proliferation of castration-resistant prostate cancer cells. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2017, 49, 999–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Abdalla, T.; Bratcher, P.E.; Jackson, P.L.; Sabbatini, G.; Wells, J.M.; Lou, X.Y.; Quinn, R.; Blalock, J.E.; Clancy, J.P.; et al. Doxycycline improves clinical outcomes during cystic fibrosis exacerbations. Eur. Respir. J. 2017, 49, 1601102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Sample Availability: Samples of the compounds are not available from the authors. |

| BMPO-Adduct | aN, mT | aHβ, mT | aHγ, mT |

|---|---|---|---|

| •BMPO-OH(1) | 1.424 ± 0.008 | 1.27 ± 0.02 | 0.068 ± 0.005 |

| •BMPO-OH(2) | 1.41 ± 0.01 | 1.51 ± 0.01 | 0.06 ± 0.01 |

| •BMPO-OOH(1) | 1.33 ± 0.01 | 1.18 ± 0.01 | – |

| •BMPO-OOH(2) | 1.34 ± 0.01 | 0.97 ± 0.01 | – |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Misak, A.; Kurakova, L.; Goffa, E.; Brezova, V.; Grman, M.; Ondriasova, E.; Chovanec, M.; Ondrias, K. Sulfide (Na2S) and Polysulfide (Na2S2) Interacting with Doxycycline Produce/Scavenge Superoxide and Hydroxyl Radicals and Induce/Inhibit DNA Cleavage. Molecules 2019, 24, 1148. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24061148

Misak A, Kurakova L, Goffa E, Brezova V, Grman M, Ondriasova E, Chovanec M, Ondrias K. Sulfide (Na2S) and Polysulfide (Na2S2) Interacting with Doxycycline Produce/Scavenge Superoxide and Hydroxyl Radicals and Induce/Inhibit DNA Cleavage. Molecules. 2019; 24(6):1148. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24061148

Chicago/Turabian StyleMisak, Anton, Lucia Kurakova, Eduard Goffa, Vlasta Brezova, Marian Grman, Elena Ondriasova, Miroslav Chovanec, and Karol Ondrias. 2019. "Sulfide (Na2S) and Polysulfide (Na2S2) Interacting with Doxycycline Produce/Scavenge Superoxide and Hydroxyl Radicals and Induce/Inhibit DNA Cleavage" Molecules 24, no. 6: 1148. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24061148

APA StyleMisak, A., Kurakova, L., Goffa, E., Brezova, V., Grman, M., Ondriasova, E., Chovanec, M., & Ondrias, K. (2019). Sulfide (Na2S) and Polysulfide (Na2S2) Interacting with Doxycycline Produce/Scavenge Superoxide and Hydroxyl Radicals and Induce/Inhibit DNA Cleavage. Molecules, 24(6), 1148. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24061148