Ethnobotany, Phytochemistry and Pharmacological Effects of Plants in Genus Cynanchum Linn. (Asclepiadaceae)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Ethnomedicinal Uses

3. Chemical Constituents

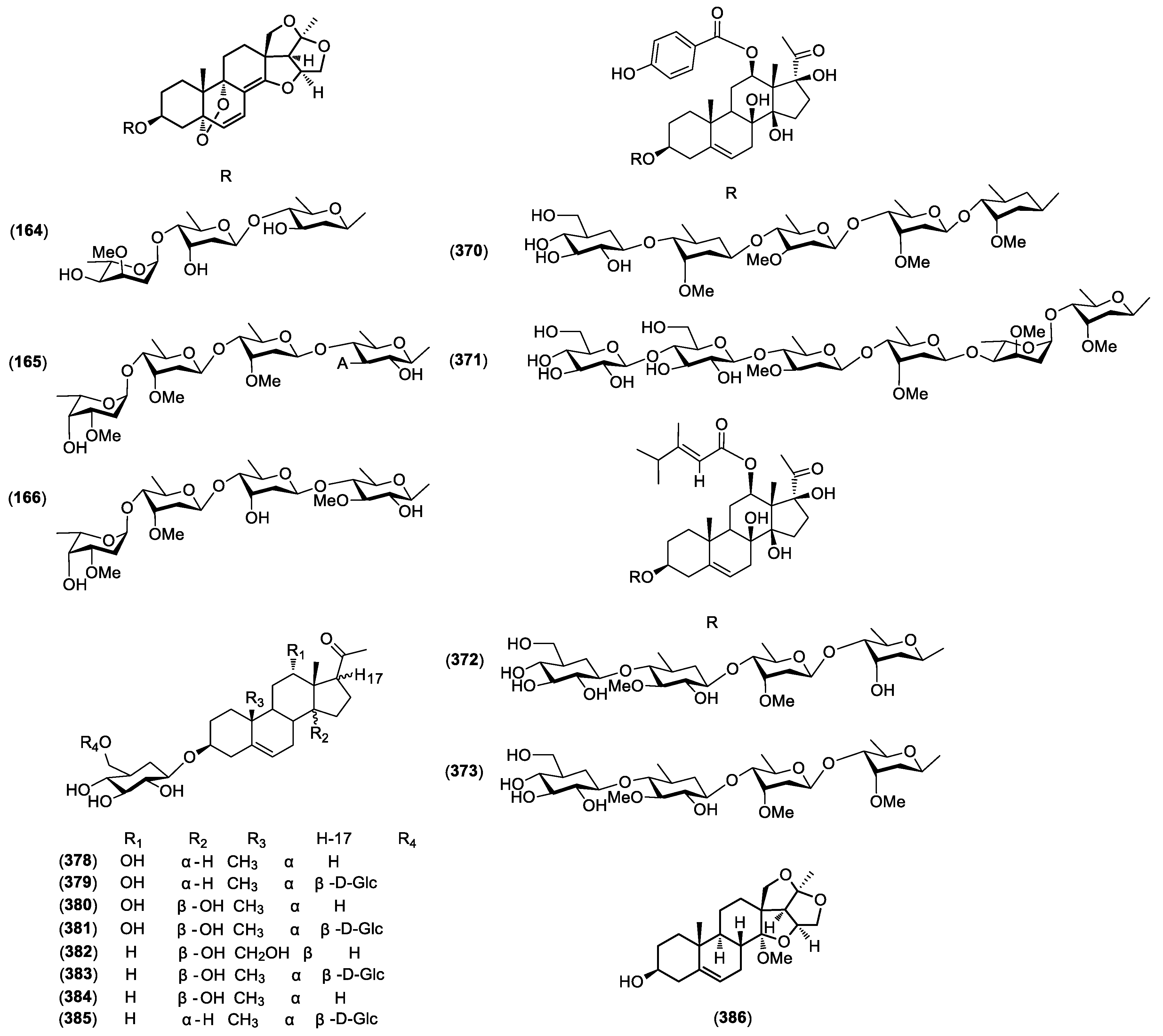

3.1. C21 Steroids

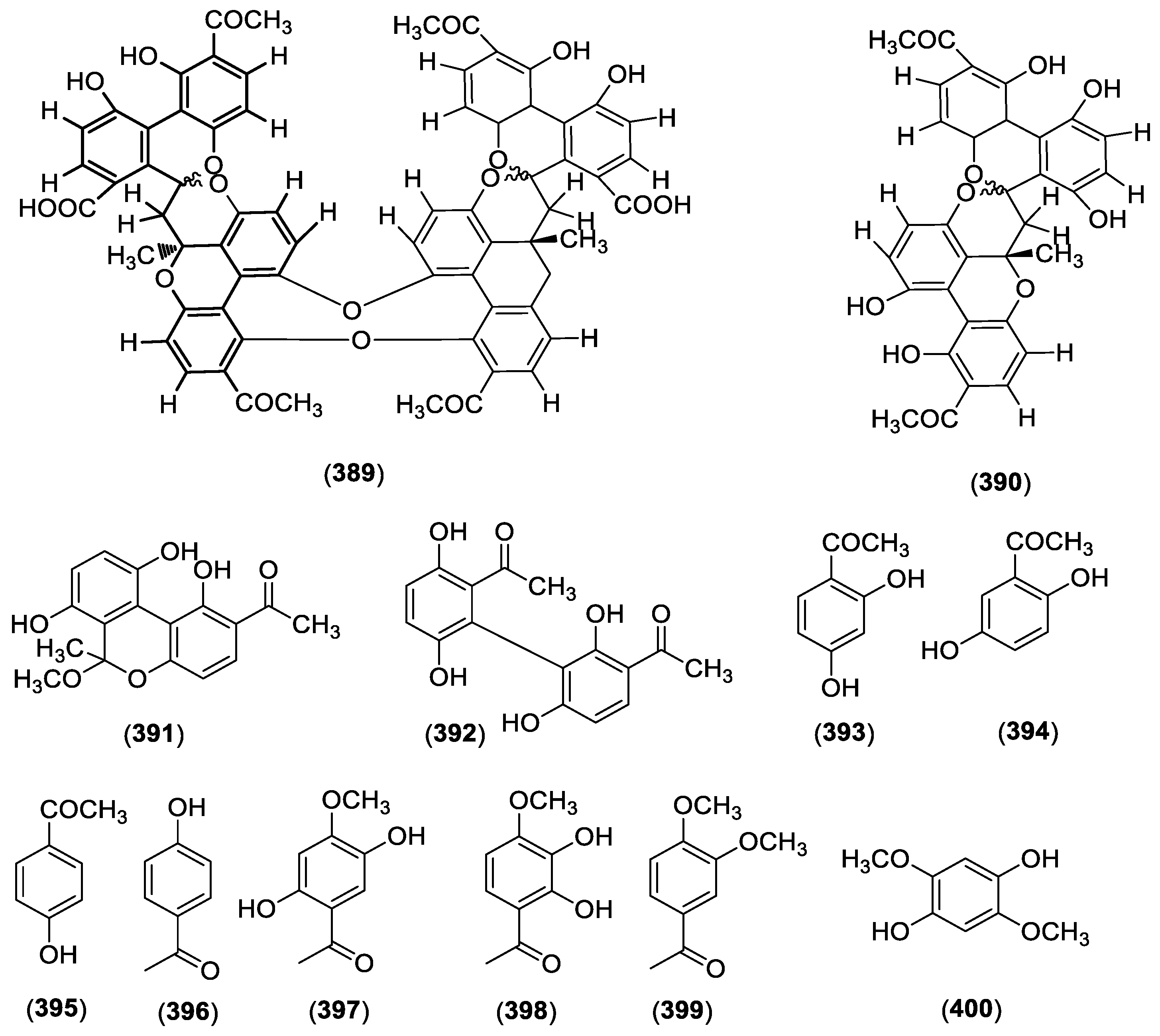

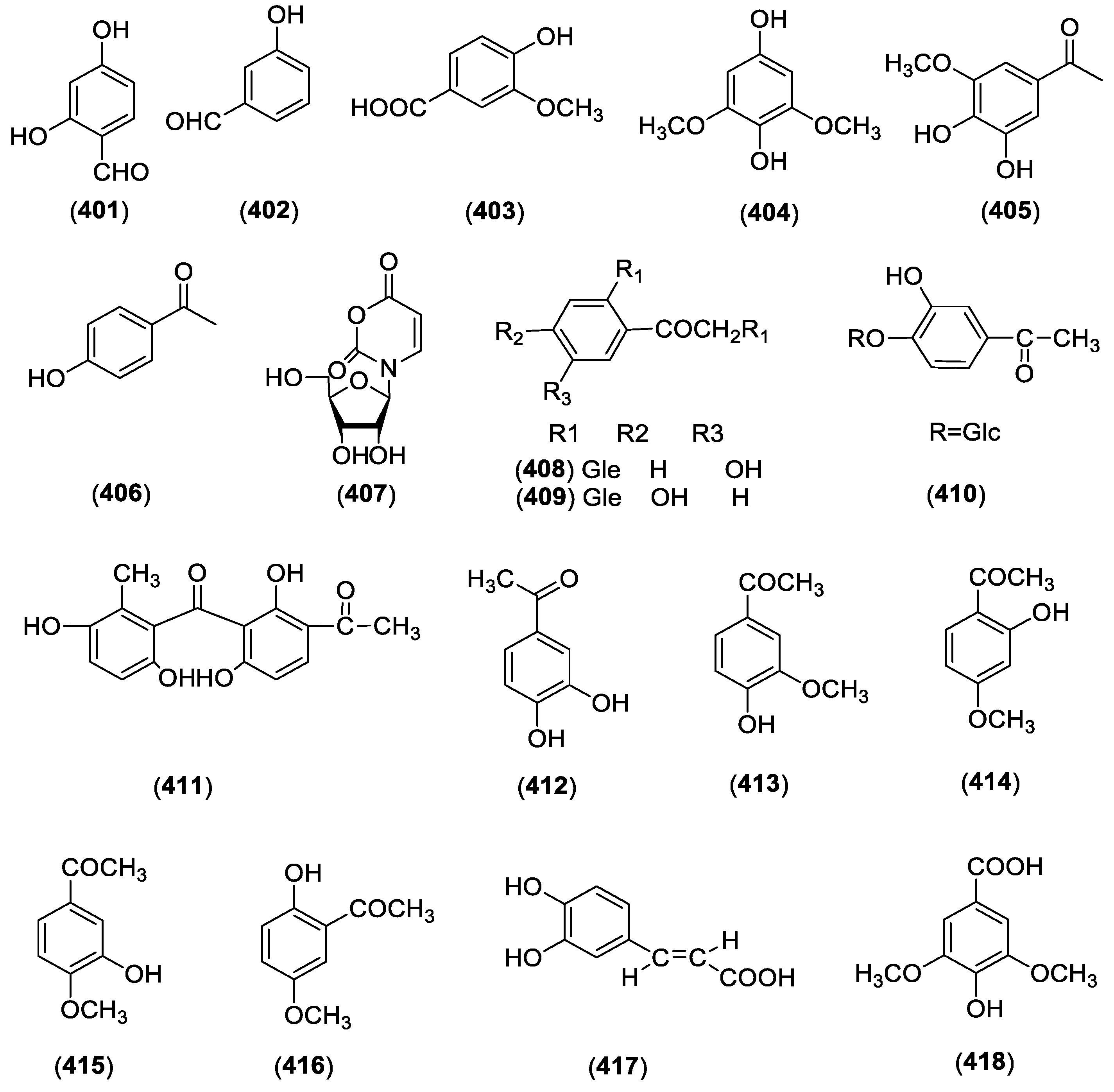

3.2. Benzene and Its Derivatives

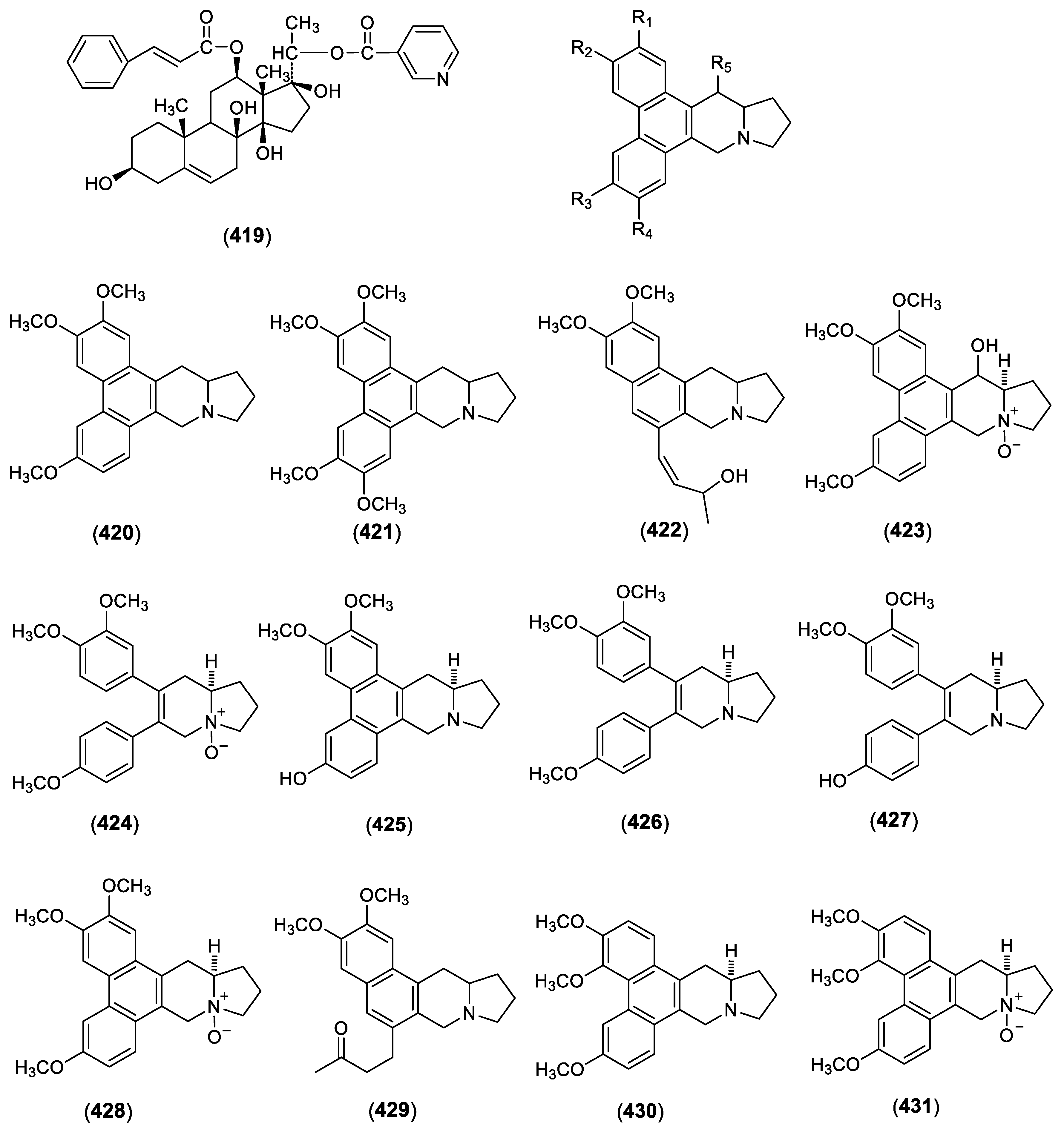

3.3. Alkaloids

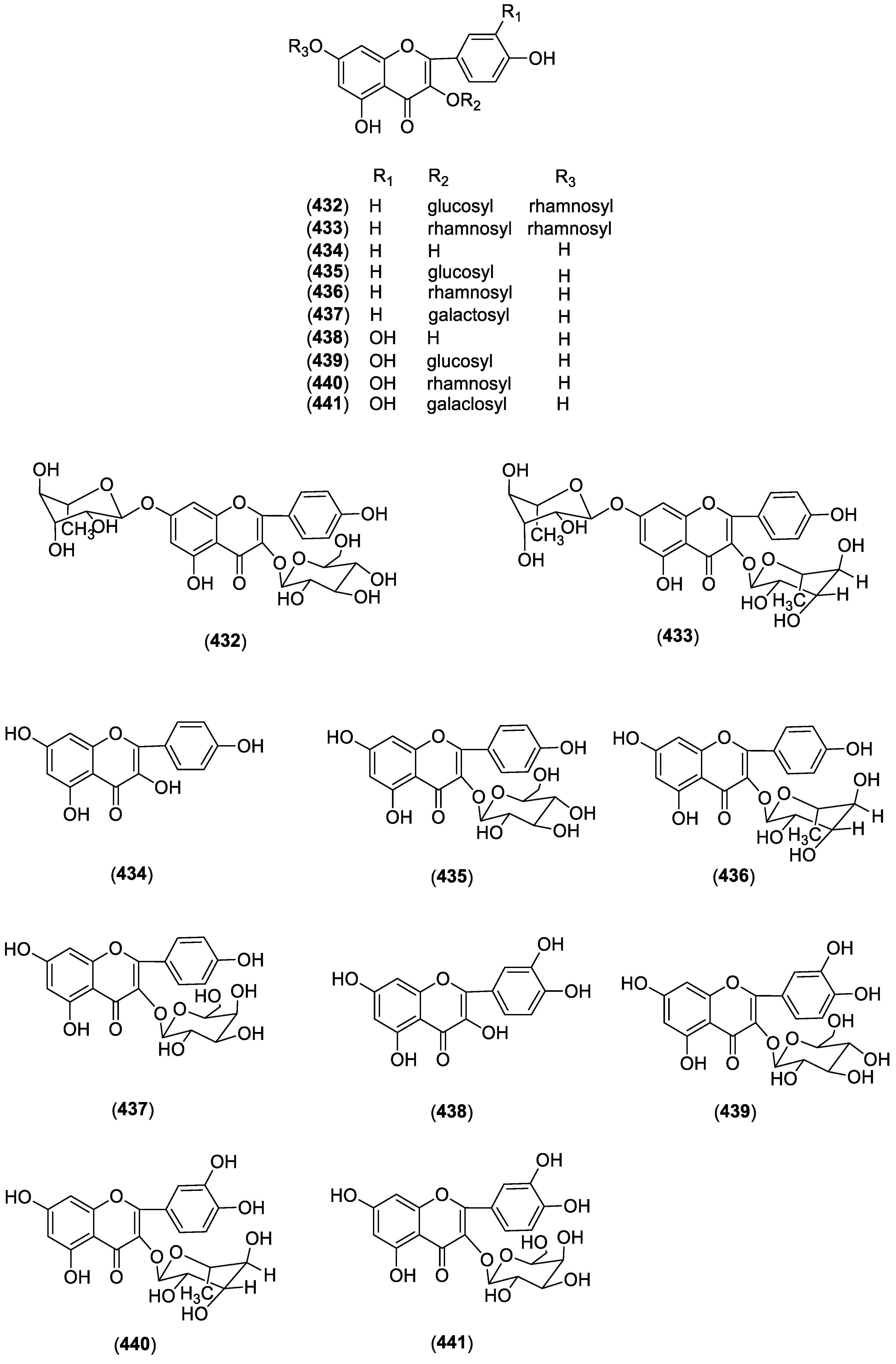

3.4. Flavones

3.5. Terpene

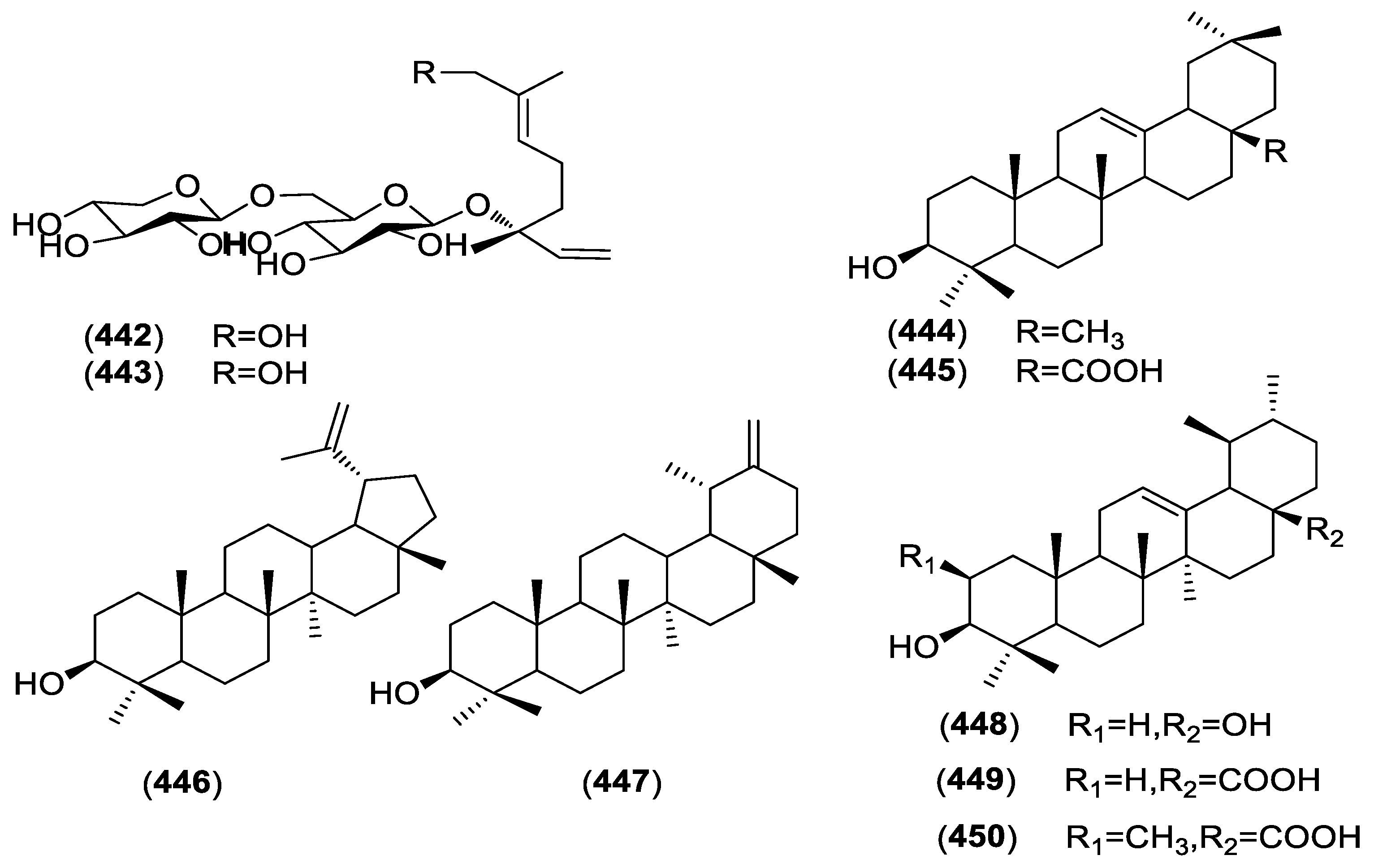

3.6. Others

4. Pharmacology

4.1. Anti-Cancer

4.2. Neuroprotective Effect

4.3. Anti-Fungal, Anti-Parasitic and Anti-Viral Activities

4.4. Anti-Inflammatory and Immunosuppressive Effects

4.5. Anti-Oxidizing Effect

4.6. Hepatoprotective Function

4.7. Appetite Suppressant Effect

4.8. Anti-Depressant Effect

4.9. Vasodilating Activity

4.10. Others

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wu, Z.; Ding, L.; Zhao, S. Chemical constituents and pharmacological effects of Cynanchum Linn. World Phytomed. 1991, 6, 147–154. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, X.J.; Hao, D.C. Recent advances in phytochemistry and pharmacology of C21 steroid constituents from Cynanchum plants. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 2016, 14, 321–334. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Choi, H.G.; Li, Y.; Park, Y.M.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, D.H.; Lee, J.H.; Son, J.K.; Na, M.; Lee, S.H. Chemical constituents of Cynanchum wilfordii and the chemotaxonomy of two species of the family asclepiadacease, C. wilfordii and C. auriculatum. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2011, 34, 2021–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Zhang, C.; Wu, L.; Dai, Y.; Wu, Q. Research advances on chemical constituents and pharmacological actions of Cynanchum Linn. J. Chin. Med. Mater. 2003, 3, 216–218. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Zhou, H. Research advances on chemical constituents of Cynanchum Linn. Central South Pharm. 2006, 4, 371–375. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng-Xiang, Q.; Zhuang-Xin, Z.; Lin, Y.; Jun, Z. Two new glycosides from the roots of Cynanchum versicolor. Planta Med. 1991, 57, 454–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Z.; Zhang, W.; Kong, L.; Liang, M.; Li, H.; Lin, M.; Liu, R.; Zhang, C. Rapid identification of C21 steroidal saponins in Cynanchum versicolor bunge by electrospray ionization multi-stage tandem mass spectrometry and liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2007, 21, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, W.; Eisenbrand, G. Cynanchum glaucescens (decne.) hand.-mazz. In Chinese Drugs of Plant Origin: Chemistry, Pharmacology, and Use in Traditional and Modern Medicine; Tang, W., Eisenbrand, G., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1992; pp. 417–428. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.-J.; Wang, B.; Zhang, J.-X.; Yan, C.; Mu, S.-Z.; Hao, X.-J. Studies on cytotoxic pregnane sapogenins from Cynanchum wilfordii. Fitoterapia 2015, 101, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Y.-W.; Zhang, Q.-Z.; Xu, D.-H.; Liang, J.-H.; Wang, B. Antiparasitic effect of cynatratoside-c from Cynanchum atratum against Ichthyophthirius multifiliis on grass carp. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 7183–7189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji-Hong, W.; Yan-Li, W.; Yu-Hua, L.; Ji-Yuan, Z.; Ze-Hong, L.I. Activity of two extracts of Cynanchum paniculatum against Ichthyophthirius multifiliis theronts and tomonts. Parasitology 2017, 144, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, G.G.; Chan, K.M.; To, M.H.; Cheng, L.; Fung, K.P.; Leung, P.C.; Lau, C.B. Potent airway smooth muscle relaxant effect of cynatratoside B, a steroidal glycoside isolated from Cynanchum stauntonii. J. Nat. Prod. 2014, 77, 1074–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, H.; Li, W.; Koike, K. Pregnane glycosides from Cynanchum atratum. Steroids 2008, 73, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, H.; Li, W.; Asada, Y.; Satou, T.; Wang, Y.; Koike, K. Twelve pregnane glycosides from Cynanchum atratum. Steroids 2009, 74, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.-X.; Wang, D.; Zhang, Y.-J.; Yang, C.-R. Identification of new qingyangshengenin and caudatin glycosides from the roots of Cynanchum otophyllum. Steroids 2011, 76, 1003–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.L.; Zhou, J.; Chen, Z.H.; Guo, S.Y.; Li, C.Q.; Zhao, W.M. Bioactive C21 steroidal glycosides from the roots of Cynanchum otophyllum that suppress the seizure-like locomotor activity of zebrafish caused by pentylenetetrazole. J. Nat. Prod. 2015, 78, 1548–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.-X.; Jiang, F.-T.; Yang, Q.-X.; Liu, X.-H.; Zhang, Y.-J.; Yang, C.-R. New pregnane glycosides from the roots of Cynanchum otophyllum. Steroids 2007, 72, 778–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, D.-Y.; Wei, J.-C.; Wan, J.-B.; Huang, X.-J.; Xiang, C.; Li, B.-C.; Zhang, Q.-W.; Wang, Y.-T.; Li, P. Four new C21 steroidal glycosides from Cynanchum otophyllum Schneid. Phytochem. Lett. 2014, 9, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tursunova, R.N.; Maslennikova, V.A.; Abubakirov, N.K. Pregnane glycosides of Cynanchum sibiricum III. The structure of sibiricosides d and e. Chem. Nat. Compd. 1975, 11, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslennikova, V.A.; Tursunova, R.N.; Abubakirov, N.K. Pregnane glycosides of Cynanchum sibiricum. Chem. Nat. Compd. 1969, 5, 279–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, H.; Xiang, W.-J.; Ma, L.; Hu, L.-H. Six new C21 steroidal glycosides from Cynanchum bungei Decne. Helv. Chim. Acta 2008, 91, 2222–2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, H.; Li, W.; Koike, K.; Satou, T.; Chen, Y.; Nikaido, T. Cynanosides a–j, ten novel pregnane glycosides from Cynanchum atratum. Tetrahedron 2005, 61, 5797–5811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Sun, H.; Ye, Y.; Chen, F.; Pan, Y. C-21 steroidal glycosides from the roots of Cynanchum chekiangense and their immunosuppressive activities. Steroids 2006, 71, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tai, Y.; Cao, X.; Li, X.; Pan, Y. Identification of C-21 steroidal glycosides from the roots of Cynanchum chekiangense by high-performance liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry. Analy. Chim. Acta 2006, 572, 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.Y.; Sung, S.H.; Kim, Y.C. New acetylcholinesterase-inhibitory pregnane glycosides of Cynanchum atratum roots. Helv. Chim. Acta 2003, 86, 474–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, W.-J.; Ma, L.; Hu, L.-H. C21 steroidal glycosides from Cynanchum wilfordii. Helv. Chim. Acta 2009, 92, 2659–2674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, M.-Y.; Choi, N.H.; Min, B.S.; Choi, G.J.; Choi, Y.H.; Jang, K.S.; Han, S.-S.; Cha, B.; Kim, J.-C. Potent in vivo antifungal activity against powdery mildews of pregnane glycosides from the roots of Cynanchum wilfordii. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 12210–12216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.-L.; Lin, T.-C.; Kuo, Y.-H. Five new pregnane glycosides from Cynanchum taiwanianum. J. Nat. Prod. 1995, 58, 1167–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, X.-J.; Yao, N.; Qian, S.-H.; Li, Y.-B.; Li, P. Four new C21 steroidal glycosides from the roots of Cynanchum auriculatum. Helv. Chim. Acta 2009, 92, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Chen, Z.; Wu, J.; Wang, L.; Wang, H.; Zhao, W. Appetite suppressing pregnane glycosides from the roots of Cynanchum auriculatum. Phytochemistry 2013, 93, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Luo, Y.; Li, G.P.; Yang, Q.X. Pregnane glycosides from the antidepressant active fraction of cultivated Cynanchum otophyllum. Fitoterapia 2016, 110, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Xu, N.; Zhou, Y.; Qiao, L.; Cao, J.; Yao, Y.; Hua, H.; Pei, Y. Steroidal glycosides from the roots of Cynanchum amplexicaule Sieb. et Zucc. Steroids 2008, 73, 629–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liqin, W.; Yuemao, S.; Xing, X.; Yuqing, W.; Jun, Z. Five new C21 steroidal glycosides from Cynanchum komarovii al.Iljinski. Steroids 2004, 69, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konda, Y.; Toda, Y.; Harigaya, Y.; Lou, H.; Li, X.; Onda, M. Two new glycosides, hancoside and neohancoside a, from Cynanchum hancockianum. J. Nat. Prod. 1992, 55, 1447–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, J.; Li, P.; Bi, Z.M.; Zhou, J.L. New c21 steroidal glycoside from Cynanchum paniculatum. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2007, 18, 300–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Zhang, J.X.; Liu, K.X.; Huang, T.; Yan, C.; Huang, L.J.; Liu, S.; Mu, S.Z.; Hao, X.J. Seco-pregnane steroidal glycosides from the roots of Cynanchum atratum and their anti-TMV activity. Fitoterapia 2014, 97, 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konda, Y.; Toda, Y.; Takayanagi, H.; Ogura, H.; Harigaya, Y.; Lou, H.; Li, X.; Onda, M. A new modified steroid, hancopregnane, and a new monoterpene from Cynanchum hancockianum. J. Nat. Prod. 1992, 55, 1118–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, M.H.; Wang, Z.J.; Yang, H.J.; Maimai, M.; Fang, J.; Tang, L.Y.; Yang, L. A new C21-steroidal glycoside from Cynanchum stauntonii. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2007, 18, 415–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, S.-H.; Wang, J.-P.; Won, S.-J.; Lin, C.-N. Bioactive constituents of the roots of Cynanchum atratum. J. Nat. Prod. 2001, 64, 608–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Qin, H.-L.; Zhang, L.; Li, Z.-H.; Wang, Y.-H.; Zhu, H.-B. Steroids from the roots of Cynanchum stauntonii. Planta Med. 2004, 70, 1075–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dou, J.; Li, P.; Song, Y.; Qi, L.W.; Bi, Z.M. Application of liquid chromatography coupled with electrospray ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry for screening and quantitative analysis of C21 steroids in the roots and rhizomes of Cynanchum paniculatum. J. Sep. Sci. 2007, 30, 992–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, N.; Wang, M.; Kikuzaki, H.; Nakatani, N.; Ho, C.-T. Two C21-steroidal glycosides isolated from Cynanchum stauntoi. Phytochemistry 1999, 52, 1351–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.-Q.; Deng, A.-J.; Qin, H.-L. Nine new steroidal glycosides from the roots of Cynanchum stauntonii. Steroids 2013, 78, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, C.-Z.; Liu, J.-X.; Pang, S.-W.; Dai, Y.; Zhou, H.; Mu, Z.-Q.; Wu, J.; Tang, J.-S.; Liu, L.; Yao, X.-S. Steroidal glycosides from the roots of Cynanchum stauntonii and their effects on the expression of iNOS and COX-2. Phytochem. Lett. 2016, 16, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, A.J.; Yu, J.Q.; Li, Z.H.; Ma, L.; Zhang, Z.H.; Qin, H.L. 14,15-secopregnane-type glycosides with 5alpha:9alpha-peroxy and delta(6,8(14))-diene linkages from the roots of Cynanchum stauntonii. Molecules 2017, 22, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Li, X.; Xiang, C.; Qin, Y.; He, J.; Li, B.C.; Li, P. Cytotoxicity of pregnane glycosides of Cynanchum otophyllum. Steroids 2015, 104, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.-F.; Shan, W.-G.; Zhan, Z.-J. Polyhydroxypregnane glycosides from the roots of Cynanchum otophyllum. Helv. Chim. Acta 2011, 94, 2272–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.R.; Li, Y.B.; Liu, X.D.; Zhang, J.F.; Duan, J.A. Antitumor activity of C-21 steroidal glycosides from Cynanchum auriculatum Royle ex Wight. Phytomedicine 2008, 15, 1016–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.-B.; He, H.-P.; Lu, C.-H.; Mu, Q.-Z.; Shen, Y.-M.; Hao, X.-J. C21 steroidal glycosides of seven sugar residues from Cynanchum otophyllum. Steroids 2006, 71, 935–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.L.; Gao, Z.B.; Zhao, W.M. Identification and evaluation of antiepileptic activity of C21 steroidal glycosides from the roots of Cynanchum wilfordii. J. Nat. Prod. 2016, 79, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Shen, Y.; He, H.; Du, Z.; Mu, Q.; Hao, X. C21 steroidal saponins from Cynanchum otophyllum. Chin. Herb. Med. 2015, 7, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.-X.; Bao, Y.-R.; Wang, S.; Zhu, R.-Q.; Bao, L.-N.; Guan, Y.-P.; Meng, X.-S. Steroidal glycosides from roots of Cynanchum otophyllum. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2015, 51, 703–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Bao, Y.-R. A new steroidal glycoside from roots of Cynanchum wallichii. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2015, 51, 897–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, B.Y.; Kim, S.E.; Kim, Y.H.; Kim, H.S.; Hong, Y.-S.; Ro, J.S.; Lee, K.S.; Lee, J.J. Pregnane glycoside multidrug-resistance modulators from Cynanchum wilfordii. J. Nat. Prod. 1999, 62, 640–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Rao, L.L.; Xiang, C.; Li, B.C.; Li, P. C21 steroidal glycosides from the roots of Cynanchum saccatum. Steroids 2015, 101, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, L.-L.; Zhang, M.; Xiang, C.; Li, B.-C.; Li, P. Steroid glycosides and phenols from the roots of Cynanchum saccatum. Phytochem. Lett. 2015, 11, 49–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, L.W.; Gu, X.J.; Li, P.; Liang, Y.; Hao, H.; Wang, G. Structural characterization of pregnane glycosides from Cynanchum auriculatum by liquid chromatography on a hybrid ion trap time-of-flight mass spectrometer. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2009, 23, 2151–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.S.; Oh, J.Y.; Choi, S.U.; Lee, K.R. Chemical constituents from the roots of Cynanchum paniculatum and their cytotoxic activity. Carbohydr. Res. 2013, 381, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Hu, Y.; Yu, S.; Fu, G.; Huang, X.; Fan, L. Steroidal glycosides from Cynanchum forrestii Schlechter. Steroids 2006, 71, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Qu, J.; Yu, S.-S.; Hu, Y.-C.; Huang, X.-Z. Seven new steroidal glycosides from the roots of Cynanchum forrestii. Steroids 2007, 72, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.L.; Tan, H.; Shen, Y.M.; Kawazoe, K.; Hao, X.J. A pair of new C-21 steroidal glycoside epimers from the roots of Cynanchum paniculatum. J. Nat. Prod. 2004, 67, 82–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lou, H.; Li, X.; Onda, M.; Konda, Y.; Machida, T.; Toda, Y.; Harigaya, Y. Further isolation of glycosides from Cynanchum hancockianum. J. Nat. Prod. 1993, 56, 1437–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.-Q.; Zhao, L. Two new glycosides and one new neolignan from the roots of Cynanchum stauntonii. Phytochem. Lett. 2015, 13, 355–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, A.J.; Zhang, D.; Li, Q.; Zhang, Z.H.; Li, Z.H.; Qin, H.L. Sugar-free pregnane-type steroids from the roots of Cynanchum stauntonii. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2017, 19, 557–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.; Chen, H.; Li, W.; Pei, Y.H. Steroidal glycosides from Cynanchum amplexicaule. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2011, 13, 756–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeo, H.; Kim, K.W.; Kim, J.; Choi, Y.H. Steroidal glycosides of the 14,15-seco-18-nor-pregnane series from Cynanchum ascyrifolium. Phytochemistry 1998, 49, 1129–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.-X.; Ge, Y.-C.; Huang, X.-Y.; Sun, Q.-Y. Cynanauriculoside C–E, three new antidepressant pregnane glycosides from Cynanchum auriculatum. Phytochem. Lett. 2011, 4, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Tan, A.-M.; Yang, S.-B.; Zhang, A.-Y.; Zhang, H. Two new C21 steroidal glycosides from the stems of Cynanchum paniculatumkitag. Helv. Chim. Acta 2009, 92, 937–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Teng, H.-L.; Yang, G.-Z.; Mei, Z.-N. Three new steroidal glycosides from the roots of Cynanchum auriculatum. Helv. Chim. Acta 2011, 94, 1296–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Fan, Q.; Xu, G.; Feng, Z.; Hao, X. C21 steroidal glycosides from acidic hydrolysate of Cynanchum otophyllum. Chin. Herb. Med. 2014, 6, 319–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.-M.; Sun, Z.-H.; Chen, M.-H.; Liao, Q.; Tan, M.; Zhang, X.-W.; Zhu, H.-D.; Pi, R.-B.; Yin, S. Neuroprotective polyhydroxypregnane glycosides from Cynanchum otophyllum. Steroids 2013, 78, 1015–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.J.; Ding, M.L.; Tao, L.J.; Zhang, M.; Xu, X.H.; Zhang, C.F. Immunosuppressive C21 steroidal glycosides from the root of Cynanchum atratum. Fitoterapia 2015, 105, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, B.; Wang, X.; Yang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Shi, S.; Guo, F.; Li, Y. Sixteen novel C-21 steroidal glycosides from the roots of Cynanchum mooreanum. Steroids 2015, 104, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.-Q.; Zhao, L. Seco-pregnane steroidal glycosides from the roots of Cynanchum stauntonii. Phytochem. Lett. 2016, 16, 34–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsoukalas, M.; Psichas, A.; Reimann, F.; Gribble, F.M.; Lobstein, A.; Urbain, A. Pregnane glycosides from Cynanchum menarandrense. Steroids 2017, 125, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheng, F.; Chen, M.; Tan, Y.; Xiang, C.; Zhang, M.; Li, B.; Su, H.; He, C.; Wan, J.; Li, P. Protective effects of otophylloside n on pentylenetetrazol-induced neuronal injury in vitro and in vivo. Front. Pharmacol. 2016, 7, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shibano, M.; Misaka, A.; Sugiyama, K.; Taniguchi, M.; Baba, K. Two secopregnane-type steroidal glycosides from Cynanchum stauntonii (Decne.) Schltr.ex Levl. Phytochem. Lett. 2012, 5, 304–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.-L.; Won, S.-J.; Day, S.-H.; Lin, C.-N. A cytotoxic acetophenone with a novel skeleton, isolated from Cynanchum taiwanianum. Helv. Chim. Acta 1999, 82, 1716–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.-Y.; Chang, T.-S.; Shen, H.-C.; Tai, S.S.-K. Murine tyrosinase inhibitors from Cynanchum bungei and evaluation of in vitro and in vivo depigmenting activity. Exp. Dermatol. 2011, 20, 720–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weon, J.B.; Lee, B.; Yun, B.R.; Lee, J.; Ma, C.J. Simultaneous determination of ten bioactive compaounds from the roots of Cynanchum paniculatum by using high performance liquid chromatography coupled-diode array detector. Pharmacogn. Mag. 2012, 8, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Weon, J.B.; Kim, C.Y.; Yang, H.J.; Ma, C.J. Neuroprotective compounds isolated from Cynanchum paniculatum. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2012, 35, 617–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.-L.; Lin, T.-C.; Kuo, Y.-H. Two acetophenone glucosides, cynanonesides A and B, from Cynanchum taiwanianum and revision of the structure for cynandione a. J. Nat. Prod. 1997, 60, 368–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wang, J.; Xiang, L.; Zhu, L. Separation and purification of baishouwubenzophenone, 4-hydroxyacetophenone and 2,4-dihydroxyacetophenone from Cynanchum auriculatum Royle ex Wight by HSCCC. Chromatographia 2009, 70, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, H.; Kim, J. A benzoquinone from Cynanchum wilfordii. Phytochemistry 1997, 46, 1103–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.-S.; Lai, J.-S.; Kao, Y.-H. The constituents of Cynanchum taiwanianum. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 1991, 38, 393–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.-L.; Chen, X.; Wu, Y.; Jiang, H.-Q.; Zhang, X.-L.; Li, E.-T.; Li, Y.-Y.; Zhou, H.-L.; Liu, J.-G.; Wang, D.-Y. Chemical constituents from Cynanchum paniculatum (Bunge) Kitag. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2015, 61, 139–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.-U.; Kang, S.-I.; Yoon, S.-H.; Budesinsky, M.; Kasal, A.; Mayer, K.K.; Wiegrebe, W. A new steroidal alkaloid from the roots of Cynanchum caudatum. Planta Med. 2000, 66, 480–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanner, U.; Wiegrebe, W. Alkaloids of Cynanchum vincetoxicum: Efficacy against MDA-MB-231 mammary carcinoma cells. Arch. Pharm. (Weinheim) 1993, 326, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budzikiewicz, H.; Faber, L.; Herrmann, E.-G.; Perrollaz, F.F.; Schlunegger, U.P.; Wiegrebe, W. Vinceten, ein benzopyrroloisochinolin-alkaloid, aus Cynanchum vincetoxicum (L.) pers. (Asclepiadaceae). Liebigs Annalen der Chemie 1979, 1979, 1212–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Stærk, D.; Christensen, J.; Lemmich, E.; Duus, J.Ø.; Olsen, C.E.; Jaroszewski, J.W. Cytotoxic activity of some phenanthroindolizidine N-oxide alkaloids from Cynanchum vincetoxicum. J. Nat. Prod. 2000, 63, 1584–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staerk, D.; Lykkeberg, A.K.; Christensen, J.; Budnik, B.A.; Abe, F.; Jaroszewski, J.W. In vitro cytotoxic activity of phenanthroindolizidine alkaloids from Cynanchum vincetoxicum and tylophora tanakae against drug-sensitive and multidrug-resistant cancer cells. J. Nat. Prod. 2002, 65, 1299–1302. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- An, T.; Huang, R.-Q.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, D.-K.; Li, G.-R.; Yao, Y.-C.; Gao, J. Alkaloids from cynanchum komarovii with inhibitory activity against the tobacco mosaic virus. Phytochemistry 2001, 58, 1267–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Gao, Y.; Wang, K.; Hu, Z. Determination of active components in Cynanchum chinense R. Br. by capillary electrophoresis. Biomed. Chromatogr. 2006, 20, 451–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.-U.; Shin, U.-S.; Huh, K. Inhibitory effects of gagaminine, a steroidal alkaloid from Cynanchum wilfordi, on lipid peroxidation and aldehyde oxidase activity. Planta Med. 1996, 62, 485–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konda, Y.; Toida, T.; Kaji, E.; Takeda, K.; Harigaya, Y. First total synthesis of two new diglycosides, neohancosides a and b, from Cynanchum hancockianum. Carbohydrate Res. 1997, 301, 123–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, L.; Zhang, W.D.; Zhang, C.; Liu, R.H.; Su, J.; Zhou, Y. Antitumor activity of crude extract and fractions from root tuber of Cynanchum auriculatum Royle ex Wight. Phytother. Res. 2005, 19, 259–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, S.; Zhao, J.; Wang, S.; Han, J. The mechanism of antitumor activity of total glucosides extracted from Cynanchum auriculatum royle (CA). Chin. J. Cancer Res. 1989, 1, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Gu, X.; Peng, Y.; Huang, W.; Qian, S. Two new cytotoxic pregnane glycosides from Cynanchum auriculatum. Planta Med. 2008, 74, 551–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.-S.; Ye, Y.-P.; Shen, Y.-M.; Liang, H.-L. Two new cytotoxic C-21 steroidal glycosides from the root of Cynanchum auriculatum. Tetrahedron 2000, 56, 3875–3879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.K.; Nam, K.A.; Heo, Y.H. Cytotoxic activity and G2/M cell cycle arrest mediated by antofine, a phenanthroindolizidine alkaloid isolated from Cynanchum paniculatum. Planta Med. 2003, 69, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, Z.Q.; Yu, S.L.; Wei, Y.J.; Ma, L.; Wu, Z.F.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Q.W.; Zhao, M.; Ye, W.C.; Che, C.T.; et al. C21 steroidal glycosides from Cynanchum stauntonii induce apoptosis in HepG2 cells. Steroids 2016, 106, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, D.; Feng, B.; Chen, S.; Chen, G.; Li, Z.; Lu, X.; Sang, X.; An, X.; Wang, H.; Pei, Y. C21 steroidal glycosides from the roots of Cynanchum paniculatum. Fitoterapia 2016, 113, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Ma, L.; Wu, Z.F.; Yu, S.L.; Wang, L.; Ye, W.C.; Zhang, Q.W.; Yin, Z.Q. Cytotoxic and apoptosis-inducing activity of C21 steroids from the roots of Cynanchum atratum. Steroids 2017, 122, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.K.; Yeo, H.; Kim, J.; Markelonis, G.J.; Oh, T.H.; Kim, Y.C. Cynandione a from Cynanchum wilfordii protects cultured cortical neurons from toxicity induced by H2O2, L-glutamate, and kainate. J. Neurosci. Res. 2000, 59, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.Y.; Yoon, J.S.; Kim, E.S.; Kang, S.Y.; Kim, Y.C. Anti-acetylcholinesterase and anti-amnesic activities of a pregnane glycoside, cynatroside b, from Cynanchum atratum. Planta Med. 2005, 71, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Huang, X.B.; Wan, Q.L.; Ding, A.J.; Yang, Z.L.; Qiu, M.H.; Sun, H.Y.; Qi, S.H.; Luo, H.R. Otophylloside b protects against abeta toxicity in Caenorhabditis elegans models of alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Prod. Bioprospect. 2017, 7, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, W.; Oh, T.S.; Park, Y.J. Anti-viral effect of herbal medicine korean traditional Cynanchum paniculatum (BGE.) kitag extracts. Afr J. Tradit. Complement Altern. Med. 2017, 14, 194–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.-G.; Yang, J.-Y.; Lee, H.-S. Acaricidal potentials of active properties isolated from Cynanchum paniculatum and acaricidal changes by introducing functional radicals. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 7568–7573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.-C.; Wang, B.-C.; Yang, X.-S.; Wang, Q. Chemical composition of the volatile oil from Cynanchum stauntonii and its activities of anti-influenza virus. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2005, 43, 198–202. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.B.; Lee, S.M.; Park, J.H.; Lee, T.H.; Baek, N.I.; Park, H.J.; Lee, H.; Kim, J. Cynandione a from Cynanchum wilfordii attenuates the production of inflammatory mediators in LPS-induced BV-2 microglial cells via NF-κB inactivation. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2014, 37, 1390–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.Q.; Lin, M.B.; Deng, A.J.; Hou, Q.; Bai, J.Y.; Li, Z.H.; Ma, L.; Zhang, Z.H.; Yuan, S.P.; Jiang, R.T.; et al. 14,15-secopregnane-type C21-steriosides from the roots of Cynanchum stauntonii. Phytochemistry 2017, 138, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.Y.; Kim, M.H.; Lee, H.; Ahn, K.S.; Um, J.Y.; Lee, S.G.; Kim, J.; Yang, W.M. Cynanchum atratum inhibits the development of atopic dermatitis in 2,4-dinitrochlorobenzene-induced mice. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 90, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, C.W.; Ahn, S.; Lim, T.G.; Hong, H.D.; Rhee, Y.K.; Yang, D.C.; Jang, M. Cynanchum wilfordii polysaccharides suppress dextran sulfate sodium-induced acute colitis in mice and the production of inflammatory mediators from macrophages. Mediators Inflamm. 2017, 2017, 3859856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.K.; Yeo, H.; Kim, J.; Kim, Y.C. Protection of rat hepatocytes exposed to CCl4 in-vitro by cynandione a, a biacetophenone from Cynanchum wilfordii. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2000, 52, 341–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, S.A.; Lee, S.; Sohn, E.H.; Yang, J.; Park, D.W.; Jeong, Y.J.; Kim, I.; Kwon, J.E.; Song, H.S.; Cho, Y.M.; et al. Cynanchum wilfordii radix attenuates liver fat accumulation and damage by suppressing hepatic cyclooxygenase-2 and mitogen-activated protein kinase in mice fed with a high-fat and high-fructose diet. Nutr. Res. 2016, 36, 914–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Fu, X.; Zhao, S.; Fu, X.; Zhang, H.; Shao, L.; Li, G.; Fan, C. Antiangiogenic properties of caudatin in vitro and in vivo by suppression of VEGF-VEGFR2-AKT/FAK signal axis. Mol. Med. Rep. 2017, 16, 8937–8943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.N.; Huang, P.L.; Wang, J.J.; Day, S.H.; Lin, H.C.; Wang, J.P.; Ko, Y.L.; Teng, C.M. Stereochemistry and biological activities of constituents from Cynanchum taiwanianum. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1998, 1380, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devitt, G.; Howard, K.; Mudher, A.; Mahajan, S. Raman spectroscopy: An emerging tool in neurodegenerative disease research and diagnosis. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2018, 9, 404–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, G.; Choi, C.Y.; Jun, W. Effects of aqueous extracts of Cynanchum wilfordii in rat models for postmenopausal hot flush. Prev. Nutr. Food Sci. 2016, 21, 373–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Lee, G.; Shin, J.; Choi, H.; Jo, A.; Pan, S.; Bae, D.; Lee, Y.; Choi, C. Cynanchum wilfordii ameliorates testosterone-induced benign prostatic hyperplasia by regulating 5alpha-reductase and androgen receptor activities in a rat model. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Name | Medicinal Parts | Traditional Uses | Distribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| C. sibiricum Willd. | Whole plant | Carbuncle swollen | Russia, China (Ovr Mongol, Gansu, Xinjiang) |

| C. chinense R. Br. | Whole plant | Wind-dispelling prescription | China (Liaoning, Hebei, Henan, Shandong, Shangxi, Ningxia, Gansu, Jiangsu, Zhejiang) |

| C. auriculatum Royle ex Wight | Roots | Stop coughing, cure neurasthenia, gastric and duodenal ulcers, nephritis, and so on. | India, China (Shandong, Hebei, Henan, Shanxi, Gansu, Tibet, Anhui, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Fujian, Taiwan, Jiangxi, Hunan, Hubei, Guangxi, Guangdong, Guizhou, Sichuang, Yunnan) |

| C. officinale (Hemsl.) Tsiang et Zhang | Roots | Treatment of tonic analgesia, epilepsy, rabies and snake bites. | China (Shanxi, Anhui, Jiangxi, Hunan, Hubei, Guangxi, Guizhou, Sichuan, Yunnan) |

| C. bungei Decne. | Roots | For physically weak and insomnia, forgetful dreams, skin itching. | North Korea, China (Liaoning, OvrMongol, Hubei, Hunan, Shandong, Shanxi, Gansu). |

| C. otophyllum Schneid. | Roots | For rheumatoid bone pain, rubella itching, epilepsy, rabies bites, snake bites. | China (Hunan, Guangxi, Guizhou, Yunnan, Sichuan, Tibet) |

| C. corymbosum Wight | Whole plant | Treatment of neurasthenia, chronic nephritis, orchitis, urinary amenorrhea, tuberculosis, hepatitis and so on. | India, Burma, Laos, Vietnam, Kampuchea, Malaysia; China (Fujian, Guangxi, Guangdong, Sichuan, Yunnan) |

| C. wilfordii (Maxim.) Hemsl. | Roots | Injury, dysentery, infantile malnutrition, stomach pain, leucorrhea, sore ringworm. | China (Liaoning, Henan, Shandong, Shanxi, Shaanxi, Gansu, Xinjiang, Jiangsu, Anhui, Sichuan, Hunan, Hubei), North Korea, Japan. |

| C. amplexicaule (Sieb. et Zucc.) Hemsl. var. castaneum Makino | Whole plant | Swelling and poisoning, governance bruises, rheumatism. | North Korea, Japan, China (Heilongjiang, Liaoning) |

| C. forrestii Schltr. var. forrestii | Roots | Reduce pain, accelerate the healing. | Tibet, Gansu, Sichuan, Guizhou and Yunnan |

| C. stauntonii (Decne.) Schltr. ex Levl. | Whole plant | Treatment of lung disease, infantile malnutrition plot, cold cough and chronic bronchitis and so on. | Gansu, Anhui, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Hunan, Jiangxi, Fujian, Guangdong, Guangxi and Guizhou. |

| C. vincetoxicum (L.) Pers. | Roots, seeds | Root: antiemetic; seed extract: treat cardiac failure. | China (Sichuan, Yunnan, Jiangsu and Taiwan), India and central and Western Europe |

| C. inamoenum (Maxim.) Loes. | Roots | Postpartum depression, pregnancy enuresis, scabies and lymphadenitis. | China (Liaoning, Hebei, Shandong, Shanxi, Anhui, Zhejiang, Hubei, Hunan, Shaanxi, Gansu, Guizhou, Sichuan, Tibet), North Korea and Japan. |

| C. atratum Bunge | Roots, stems | Clearing heat antitoxicant, insufficiency of vital energy and blood, fever. | China (Heilongjiang, Jilin, Shandong, Hebei, Henan, Shanxi, Shanxi, Sichuan, Guizhou, Yunnan, Guangxi, Liaoning, Guangdong, Hunan, Hubei, Fujian, Jiangxi, Jiangsu), North Korea and Japan |

| C. glaucesces (Decne.) Hand.-Mazz. | Roots, stems | Relieving dyspnea, antitussive and antiasthmatic. | Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Fujian, Jiangxi, Hunan, Guangdong, Guangxi and Sichuan |

| C. paniculatum (Bunge) Kitagawa | Roots, stems | Rheumatism, stomach pain, toothache, low back pain, flutters injury, urticaria, and eczema. | China (Liaoning, Ovr Mongol, Hebei, Henan, Shanxi, Gansu, Sichuan, Guizhou, Yunnan, Shandong, Anhui, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Jiangxi, Shanxi, Hubei, Hunan, Guangdong and Guangxi), North Korea and Japan. |

| C.versicolor Bunge | Roots and stems | Reducing fever and causing diuresis, cure tuberculosis, edema, pain and so on. | China (Jilin, Liaoning, Hebei, Henan, Sichuan, Shandong, Jiangsu and Zhejiang) |

| C. chekiangense M. Cheng ex Tsiang et P. T. Li | Roots | Treatment of bruises, smashed topical, and scabies. | China (Zhejiang, Henan, Hunan and Guangdong) |

| C.mooreanum Hemsl. | Whole plant | Wash sores scabies. | China (Henan, Hubei, Hunan, Anhui, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Jiangxi, Fujian and Guangdong) |

| Name | Compositions | Effect/Traditional Use | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baiwei san | Cynanchum atratum Bunge, Zingiber officinale Rosc., Trichosanthes kirilowii Maxim., Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch., Mirabilite. | Antidepressant | ‘Qian jin yi fang’, vol. 18 |

| Baiwei yuan | Cynanchum atratum Bunge, Rehmannia glutinosa (Gaetn.) Libosch. ex Fisch. et Mey., Cinnamomum cassia Presl, Rubia yunnanensis Diels, Taxillus sutchuenensis (Lecomte) Danser, Dendrobium nobile Lindl., Achyranthes bidentata Blume, Ligusticum chuanxiong Hort., Saposhnikovia divaricata (Trucz.) Schischk., Panax ginseng C. A. Mey., Aristolochia fangchi Y. C. Wu ex L. D. Chow et S. M. Hwang, Cornus officinalis Sieb. et Zucc., Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels, Schisandra chinensis (Turcz.) Baill. | Infertility, abortion | ‘Song·tai ping hui min he ji jv fang’ |

| Baiwei tang | Cynanchum atratum Bunge, Panax ginseng C. A. Mey., Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels, Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch. | Depressed dizziness, and occurrence of temporary fainting. | ‘Pu ji ben shi fang’, vol. 7 |

| Baiwei wan | Cynanchum atratum Bunge, Panax ginseng C. A. Mey., Aconitum carmichaelii Debx., Rehmannia glutinosa (Gaetn.) Libosch. ex Fisch. et Mey., Cinnamomum cassia Presl, Cynanchum otophyllum Schneid., Evodia rutaecarpa (Juss.) Benth., Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels, Areca catechu L. | Irregular menstruation, infertility | ‘Yi lve liu shu’, vol. 27 |

| Baiwei gao | Cynanchum atratum Bunge, Ampelopsis japonica (Thunb.) Makino, Bletilla striata (Thunb. ex A. Murray) Rchb. f., Typhonium giganteum Engl., Angelica dahurica (Fisch. ex Hoffm.) Benth. et Hook. f. ex Franch. et Sav., Paeonia lactiflora Pall., frankincense, Fraxinus chinensis Roxb. | Evil sore | ‘Shen hui’, vol. 63 |

| Baiwei shiwei wan | Cynanchum atratum Bunge, Anemarrhena asphodeloides Bunge, Cortex Lycii, Rehmannia glutinosa (Gaetn.) Libosch. ex Fisch. et Mey., Ophiopogon japonicus (L.f.) Ker-Gawl., Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch, Dichroa febrifuga Lour., Polygonatum odoratum (Mill.) Druce, Panax ginseng C. A. Mey. | Frail, afraid of cold, heat | ‘Wai tai’, vol. 3 |

| Baiwei wan jiawei | Saposhnikovia divaricata (Trucz.) Schischk., Notopterygium incisum Ting ex H. T. Chang, Cynanchum atratum Bunge, Tribulus terrester L., pomegranate bark, Taraxacum mongolicum Hand.-Mazz., Lonicera japonica Thunb. | Breeze heat, Nasal obstruction, headache, fever | ‘Shen shi yao han’ |

| Buyi baiwei wan | Cynanchum atratum Bunge, Dolomiaea souliei (Franch.) Shih, Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels, Cinnamomum cassia Presl, Lycopuslucidus Tur-Cz. var. hirtus Regel, Achyranthes bidentata Blume, Rehmannia glutinosa (Gaetn.) Libosch. ex Fisch. et Mey., Paeonia suffruticosa Andr., Panax ginseng C. A. Mey., Ligusticum chuanxiong Hort., Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz., Citrus aurantium L., Asarum sieboldii Miq., Aconitum carmichaelii Debx., Astragalus membranaceus (Fisch.) Bunge, Dipsacus asperoides C. Y. Cheng et T. M. Ai, Evodia rutaecarpa (Juss.) Benth., Magnolia officinalis Rehd. et Wils. | Postpartum weakness, pale complexion, diet reduced, increasingly thin. | ‘Pu ji fang’, vol. 350 |

| Jiawei baiwei wan | Cynanchum atratum Bunge, Paeonia lactiflora Pall., Adenophora stricta Miq., Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels, Ligusticum chuanxiong Hort., Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch, Astragalus membranaceus (Fisch.) Bunge. | Too much blood loss, fainting | ‘Wei sheng hong bao’, vol. 5 |

| Huachong dingdan wan | Rehmannia glutinosa (Gaetn.) Libosch. ex Fisch. et Mey., Cynanchum glaucescens (Decne.) Hand.-Mazz. | Stomach pain | ‘Bian zheng lu’, vol. 2 |

| Xuanchaung weicha san | Cynanchum atratum Bunge, Angelica dahurica (Fisch. ex Hoffm.) Benth. et Hook. f. ex Franch. et Sav., Daucus carota L., Stemona japonica (Bl.) Miq., Zanthoxylum bungeanum Maxim., Rehmannia glutinosa (Gaetn.) Libosch. ex Fisch. et Mey. | Insecticide, detoxification | ‘Yi liao bao jian cha tang pu’ |

| Jiawei baiwei tang | Cynanchum atratum Bunge, Semen Trichosanthis, Citrus maxima (Burm.) Merr., Fritillariae Thunbergii, Artemisia carvifolia, Dendrocalamopsis beecheyana (Munro) Keng var. pubescens (P. F. Li) Keng f. | Pneumonia, cough | ‘Ma pei zhi yi an’ |

| Baiwei renshen wan | Cynanchum atratum Bunge, Panax ginseng C. A. Mey., Rubia yunnanensis Diels, Achyranthes bidentata Blume, Asarum sieboldii Miq., Magnolia officinalis Rehd. et Wils., Pinellia ternata (Thunb.) Breit., Adenophora stricta Miq., Zingiber officinale Rosc., Gentiana macrophylla Pall., Zanthoxylum bungeanum Maxim., Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels, Aconitum carmichaelii Debx., Saposhnikovia divaricata (Trucz.) Schischk., Aster tataricus L. f. | Irregular menstruation, infertility | ‘Qian jin yi fang’, vol. 2 |

| Guizhi huangqi baiwei kuandonghua san | Cinnamomum cassia Presl, Astragalus membranaceus (Fisch.) Bunge, Cynanchum atratum Bunge, Tussilago farfara L., Paeonia lactiflora Pall., Anemarrhena asphodeloides Bunge. | Lung malaria | ‘Jie nue lun shu’ |

| Wumei baiwei xixin wan | Dichroa febrifuga Lour., Cynanchum atratum Bunge, Clematis apiifolia DC., Anemarrhena asphodeloides Bunge, Sophora flavescens Alt., Dichroa febrifuga Lour., Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch, Asarum sieboldii Miq. | Liver malaria | ‘Jie nue lun shu’ |

| Baiqian san | Cynanchum glaucescens (Decne.) Hand.-Mazz., Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch, Panax ginseng C. A. Mey., Rehmannia glutinosa (Gaetn.) Libosch. ex Fisch. et Mey., Cannabis sativa L., Cinnamomum cassia Presl, Wolfiporia cocos, Astragalus membranaceus (Fisch.) Bunge, donkey-hide gelatin, Ophiopogon japonicus (Linn. f.) Ker-Gawl. | Pulmonary fibrosis, cough and phlegm | ‘Sheng hui’, vol. 31 |

| Baiqian tang | Cynanchum glaucescens (Decne.) Hand.-Mazz., Aster tataricus L. f., Pinellia ternata (Thunb.) Breit., Euphorbia pekinensis Rupr. | Cough, body swollen, chest tightness, throat hoarse | ‘Bei ji qian jin yao fang’, vol. 18 |

| Baiqian yin | Cynanchum glaucescens (Decne.) Hand.-Mazz., Platycodon grandiflorus (Jacq.) A. DC., Smilax china L., Amygdalus Communis Vas, Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch. | Weak, cough, vomit blood | ‘Sheng ji zong lu’, vol. 90 |

| Shenyan baiqian tang | Cynanchum glaucescens (Decne.) Hand.-Mazz., Pinellia ternata (Thunb.) Breit., Aster tataricus L. f., Ephedra sinica Stapf, Magnolia officinalis Rehd. etWils., Panax ginseng C. A. Mey., Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch. | Cough, wheezing, nausea, vomiting, belching, hiccups | ‘Sheng ji zong lu’, vol. 67 |

| Xuchangqing san | Cynanchum paniculatum (Bunge) Kitagawa, Sophora flavescens Alt., Aconitum carmichaelii Debx., Evodia rutaecarpa (Juss.) Benth., Camptotheca acuminata Decne., Asarum sieboldii Miq., Acorus calamus L., Pinellia ternata (Thunb.) Breit. | Scabies disease | ‘Sheng ji zong lu’, vol. 137 |

| Xuchangqing tang | Cynanchum paniculatum (Bunge) Kitagawa, Perotis indica (L.) Kuntze, Akebia quinata (Houtt.) Decne., Malva crispa Linn., Areca catechu L., Dianthus superbus L. | weakness of the spleen and the stomach | ‘Ben cao gang mu’, vol. 13 |

| Anwei jian | Taraxacum mongolicum Hand.-Mazz., Cynanchum otophyllum Schneid., Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch, Carthamus tinctorius L., Cynanchum paniculatum (Bunge) Kitagawa. | Stomach pain, blood circulation | ‘Yuan zheng gang fang’ |

| Huainan wan | Plantago asiatica L., Prunus salicina Lindl., Adiantum capillus-veneris L., Cynanchum paniculatum (Bunge) Kitagawa. | Tuberculosis, upset, headache and vomiting | ‘Pu ji fang’, vol. 237 |

| No. | Compound Name | Species | Parts | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C21 steroids | ||||

| 1 | Cynanversicoside A | C. versicolor | Roots | [6] |

| 2 | Cynanversicoside B | C. versicolor | Roots | [6] |

| 3 | Cynanversicoside C | C. versicolor | Root/rhizome | [7] |

| 4 | Cynanversicoside D | C. versicolor | Root/rhizome | [7] |

| 5 | Cynanversicoside F | C. versicolor | Root/rhizome | [7] |

| 6 | Glaucogenin B | C. glaucescens | Roots | [8] |

| 7 | 12β-O-(4-hydroxybenzoyl)-8β,14β,17β-trihydroxypregn-2,5-diene-20-one | C. wilfordii | Roots | [9] |

| 8 | 12β-O-benzoyl-8β,14β,17β-trihydroxypregn-2,5-diene-20-one | C. wilfordii | Roots | [9] |

| 9 | Glaucoside A | C. glaucescens | Roots | [8] |

| 10 | Glaucoside B | C. glaucescens | Roots | [8] |

| 11 | Glaucoside C | C. glaucescens | Roots | [10] |

| 12 | Glaucoside D | C. glaucescens | Roots | [8] |

| 13 | Glaucoside E | C. glaucescens | Roots | [8] |

| 14 | Glaucoside F | C. glaucescens | Roots | [8] |

| 15 | Glaucoside G | C. glaucescens | Roots | [8] |

| 16 | Glaucoside H | C. glaucescens | Roots | [8] |

| 17 | Glaucoside I | C. glaucescens | Roots | [8] |

| 18 | Glaucoside J | C. glaucescens | Roots | [8] |

| 19 | Cynatratoside F | C. atratum | Roots | [8] |

| 20 | Cynatratoside C | C. atratum | Roots | [10] |

| 21 | Cynatratoside A | C. atratum | Roots | [11] |

| 22 | Cynatratoside B | C. atratum | Roots | [12] |

| 23 | Atratoside A | C. atratum | Roots | [13] |

| 24 | Atratoside B | C. atratum | Roots | [13] |

| 25 | Atratoside C | C. atratum | Roots | [14] |

| 26 | Atratoside D | C. atratum | Roots | [8] |

| 27 | Otophylloside A | C. forrestii C. otophyllum C. wallichii | Roots | [15] |

| 28 | Otophylloside B | C. forrestii C. otophyllum C. wallichii | Roots | [15] |

| 29 | Otophylloside C | C. otophyllum | Roots | [16] |

| 30 | Otophylloside F | C. otophyllum | Roots | [16] |

| 31 | Otophylloside H | C. otophyllum | Roots | [17] |

| 32 | Otophylloside I | C. otophyllum | Roots | [17] |

| 33 | Otophylloside J | C. otophyllum | Roots | [17] |

| 34 | Otophylloside K | C. otophyllum | Roots | [17] |

| 35 | Otophylloside L | C. otophyllum C. auriculatum | Roots | [17] |

| 36 | Otophylloside M | C. otophyllum | Roots | [17] |

| 37 | Otophylloside N | C. forrestii | Roots | [15] |

| 38 | Otophylloside O | C. forrestii | Roots | [15] |

| 39 | Otophylloside P | C. forrestii | Roots | [15] |

| 40 | Otophylloside Q | C. forrestii | Roots | [15] |

| 41 | Otophylloside R | C. forrestii | Roots | [15] |

| 42 | Otophylloside S | C. forrestii | Roots | [15] |

| 43 | Otophylloside T | C. otophyllum | Roots | [16] |

| 44 | Otophylloside U | C. otophyllum | Roots | [18] |

| 45 | Otophylloside V | C. otophyllum | Roots | [18] |

| 46 | Otophylloside W | C. otophyllum | Roots | [18] |

| 47 | Sibiricoside D | C. sibiricum | Roots | [19] |

| 48 | Sibiricoside E | C. sibiricum | Roots | [19] |

| 49 | Sibirigenin | C. sibiricum | Roots | [20] |

| 50 | Penupogenin | C. sibiricum | Roots | [20] |

| 51 | Penupogenin3-O-β-d-glucopyranosyl-(1→4)-β-l-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-α-l-diginopyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranoside | C. bungei | Stems | [21] |

| 52 | Cynanoside A | C. atratum | Roots | [22] |

| 53 | Cynanoside B | C. atratum | Roots | [22] |

| 54 | Cynanoside C | C. atratum | Roots | [22] |

| 55 | Cynanoside D | C. atratum | Roots | [22] |

| 56 | Cynanoside E | C. atratum | Roots | [22] |

| 57 | Cynanoside F | C. atratum | Roots | [22] |

| 58 | Cynanoside G | C. atratum | Roots | [22] |

| 59 | Cynanoside H | C. atratum | Roots | [22] |

| 60 | Cynanoside I | C. atratum C. versicolor | Roots | [22] |

| 61 | Cynanoside J | C. atratum | Roots | [22] |

| 62 | Cynanoside K | C. atratum | Roots | [13] |

| 63 | Cynanoside L | C. atratum | Roots | [13] |

| 64 | Cynanoside M | C. atratum | Roots | [13] |

| 65 | Cynanoside N | C. atratum | Roots | [13] |

| 66 | Cynanoside O | C. atratum | Roots | [13] |

| 67 | Cynanosides P1 | C. atratum | Roots | [14] |

| 68 | Cynanosides P2 | C. atratum | Roots | [14] |

| 69 | Cynanosides P3 | C. atratum | Roots | [14] |

| 70 | Cynanosides P4 | C. atratum | Roots | [14] |

| 71 | Cynanosides P5 | C. atratum | Roots | [14] |

| 72 | Cynanosides Q1 | C. atratum | Roots | [14] |

| 73 | Cynanosides Q2 | C. atratum | Roots | [14] |

| 74 | Cynanosides Q3 | C. atratum | Roots | [14] |

| 75 | Cynanosides R1 | C. atratum | Roots | [14] |

| 76 | Cynanosides R2 | C. atratum | Roots | [14] |

| 77 | Cynanosides R3 | C. atratum | Roots | [14] |

| 78 | Cynanoside S | C. atratum | Roots | [14] |

| 79 | Sublanceoside E3 | C. atratum | Roots | [14] |

| 80 | Chekiangensoside A | C. chekiangense | Roots | [23] |

| 81 | Chekiangensoside B | C. chekiangense | Roots | [23] |

| 82 | Chekiangensoside C | C. chekiangense | Roots | [14] |

| 83 | Chekiangensoside D | C. chekiangense | Roots | [24] |

| 84 | Chekiangensoside E | C. chekiangense | Roots | [24] |

| 85 | Cynatroside A | C. atratum | Roots | [25] |

| 86 | Cynatroside B | C. atratum | Roots | [14] |

| 87 | Cynatroside C | C. atratum | Roots | [25] |

| 88 | Wilfoside A | C. wilfordii | Roots | [26] |

| 89 | Wilfoside B | C. wilfordii | Roots | [26] |

| 90 | Wilfoside C | C. wilfordii | Roots | [26] |

| 91 | Wilfoside D | C. wilfordii | Roots | [26] |

| 92 | Wilfoside E | C. wilfordii | Roots | [26] |

| 93 | Wilfoside F | C. wilfordii | Roots | [26] |

| 94 | Wilfoside G | C. wilfordii | Roots | [26] |

| 95 | Wilfoside H | C. wilfordii | Roots | [26] |

| 96 | Wilfoside KIN | C.wilfordii | Roots | [26] |

| 97 | Wilfoside K1GG | C. wilfordii | Roots | [27] |

| 98 | Wilfoside C1GG | C. wilfordii | Roots | [27] |

| 99 | Wilfoside C1N | C. taiwanianum | Roots | [28] |

| 100 | Wilfoside C2N | C. taiwanianum | Roots | [28] |

| 101 | Wilfoside C3N | C. auriculatum | Roots | [29] |

| 102 | Wilfoside M1N | C. auriculatum | Roots | [30] |

| 103 | Wilfoside C1G | C. auriculatum | Roots | [30] |

| 104 | Wilfoside C2G | C. otophyllum | Roots | [31] |

| 105 | Amplexicoside A | C. amplexicaule | Roots | [32] |

| 106 | Amplexicoside B | C. amplexicaule | Roots | [32] |

| 107 | Amplexicoside C | C. amplexicaule | Roots | [32] |

| 108 | Amplexicoside D | C. amplexicaule | Roots | [32] |

| 109 | Amplexicoside E | C. amplexicaule | Roots | [32] |

| 110 | Amplexicoside F | C. amplexicaule | Roots | [32] |

| 111 | Amplexicoside G | C. amplexicaule | Roots | [32] |

| 112 | Tylophoside A | C. amplexicaule | Roots | [32] |

| 113 | Hancoside A | C. amplexicaule C. komarovii | Roots | [33] |

| 114 | Hancoside | C. forrestii C. hunmkiunum | Roots | [34] |

| 115 | Neocynapanogenin F 3-O-β-d-thevetoside | C. paniculatum | Roots | [35] |

| 116 | Neocynapanogenin F | C. paniculatum | Roots | [35] |

| 117 | Neocynapanogenin F 3-O-β-d-thevetopyranoside | C. atratum. | Roots | [36] |

| 118 | Glaucogenin C | C. hunmkiunum C. atratum | Roots | [37] |

| 119 | Glaucogenin C 3-O-α-l-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-digitoxopyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-canaropyranoside | C. stauntonii | root | [38] |

| 120 | Glaucogenin C 3-O-β-d-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-α-l-diginopyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-thevetopyranoside | C. atratum | Roots | [39] |

| 121 | Glaucogenin C 3-O-β-d-thevetopyranoside | C. atratum | Roots | [39] |

| 122 | Glaucogenin C mono-d-thevetoside | C. stauntonii | Roots | [40] |

| 123 | Glaucogenin C 3-O-β-d-oleandropyranoside | C. atratum. | Roots | [36] |

| 124 | Glaucogenin C 3-O-α-l-diginopyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-thevetopyranoside | C. atratum. | Roots | [36] |

| 125 | Glaucogenin C 3-O-α-l-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-oleandropyranoside | C. atratum. | Roots | [36] |

| 126 | Glaucogenin C 3-O-α-l-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-digitoxopyranosy-(1→4)-β-d-oleandropyranoside | C. atratum. | Roots | [36] |

| 127 | Glaucogenin C 3-O-β-d-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-α-l-diginopyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranoside | C. atratum. | Roots | [36] |

| 128 | Glaucogenin C 3-O-α-d-oleandropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-digitoxopyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-oleandropyranoside | C. atratum. | Roots | [36] |

| 129 | Glaucogenin C 3-O-β-d-thevetoside | C. paniculatum. | Root/rhizome | [41] |

| 130 | Glaucogenin A | C. atratum. | Roots | [36] |

| 131 | Glaucogenin A 3-O-β-d-oleandropyranoside | C. atratum. | Roots | [36] |

| 132 | Glaucogenin A 3-O-β-d-digitoxopyranoside | C. atratum. | Roots | [36] |

| 133 | Glaucogenin A 3-O-β-d-digitoxopyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d cymaropyranoside | C. atratum. | Roots | [36] |

| 134 | Glaucogenin A 3-O-β-d-glucopyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-oleandropyranoside | C. atratum. | Roots | [36] |

| 135 | Glaucogenin A 3-O-β-d-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-α-l-diginopyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranoside | C. atratum. | Roots | [36] |

| 136 | Glaucogenin A 3-O-α-l-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-digitoxopyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranoside | C. atratum. | Roots | [36] |

| 137 | Glaucogenin A 3-O-α-d-oleandropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-digitoxopyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-oleandropyranoside | C. atratum. | Roots | [36] |

| 138 | Glaucogenin A 3-O-α-l-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-digitoxopyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-digitoxopyranoside | C. atratum. | Roots | [36] |

| 139 | Glaucogenin A 3-O-β-d-oleandropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-digitoxopyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-oleandropyranoside | C. atratum. | Roots | [36] |

| 140 | Glaucogenin A 3-O-α-l-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-oleandropyranoside | C. atratum. | Roots | [36] |

| 141 | Glaucogenin A 3-O-α-l-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranoside | C. atratum. | Roots | [36] |

| 142 | Glaucogenin A 3-O-β-d-glucopyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-glucopyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-oleandropyranoside | C. atratum. | Roots | [36] |

| 143 | Glaucogenin A 3-O-α-l-oleandropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-digitoxopyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-oleandropyranoside | C. atratum. | Roots | [36] |

| 144 | Glaucogenin D | C. paniculatum. | Root /rhizome | [41] |

| 145 | Stauntoside A | C. stauntoi | Roots | [42] |

| 146 | Stauntoside B | C. stauntoi | Roots | [42] |

| 147 | Stauntoside C | C. stauntonii | Roots | [43] |

| 148 | Stauntoside D | C. stauntonii | Roots | [43] |

| 149 | Stauntoside E | C. stauntonii | Roots | [43] |

| 150 | Stauntoside F | C. stauntonii | Roots | [43] |

| 151 | Stauntoside G | C. stauntonii | Roots | [43] |

| 152 | Stauntoside H | C. stauntonii | Roots | [43] |

| 153 | Stauntoside I | C. stauntonii | Roots | [43] |

| 154 | Stauntoside J | C. stauntonii | Roots | [43] |

| 155 | Stauntoside K | C. stauntonii | Roots | [43] |

| 156 | Stauntoside L | C. stauntonii | Roots | [44] |

| 157 | Stauntoside M | C. stauntonii | Roots | [44] |

| 158 | Stauntoside O | C. stauntonii | Roots | [44] |

| 159 | Stauntoside P | C. stauntonii | Roots | [44] |

| 160 | Stauntoside Q | C. stauntonii | Roots | [44] |

| 161 | Stauntoside R | C. stauntonii | Roots | [44] |

| 162 | Stauntoside S | C. stauntonii | Roots | [44] |

| 163 | Stauntoside T | C. stauntonii | Roots | [44] |

| 164 | Stauntoside UA | C. stauntonii . | Roots | [45] |

| 165 | Stauntoside UA1 | C. stauntonii . | Roots | [45] |

| 166 | Stauntoside UA2 | C. stauntonii . | Roots | [45] |

| 167 | Kidjoranin | C. wilfordii. C. auriculatum | Roots | [9] |

| 168 | Kidjoranin-3-O-β-d-oleandropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-oleandropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranoside | C. otophyllum | Roots | [46] |

| 169 | Kidjoranin 3-O-β-d-digitoxopyranoside | C. otophyllum | Roots | [47] |

| 170 | 20-O-(4-hydroxybenzoyl)-kidjoranin | C. wilfordii | Roots | [9] |

| 171 | 20-O-vanilloyl-kidjoranin | C. wilfordii | Roots | [9] |

| 172 | 20-O-salicyl-kidjoranin | C. wilfordii | Roots | [9] |

| 173 | 20-O-(4-hydroxybenzoyl)-kidjoranin | C. wilfordii. | Roots | [9] |

| 174 | 12β-O-(4-hydroxybenzoyl)-8β,14β,17β-trihydroxypregn-2,5-diene-20-one | C. wilfordii. | Roots | [9] |

| 175 | Caudatin | C. auriculatum | Roots | [29] |

| 176 | caudatin-2,6-dideoxy-3-O-methy-β-d-cymaropyranoside | C. auriculatum | Roots | [48] |

| 177 | 3-O-methyl-caudatin | C. wilfordii | Roots | [9] |

| 178 | Caudatin 3-O-β-d-glucopyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-oleandropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranoside | C. forrestii | Roots | [15] |

| 179 | Caudatin 3-O-α-l-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-α-d-oleandropyranosyl-(1→4)-α-l-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-glucopyranosyl-(1→4)-α-d-oleandropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-oleandropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-diginopyranoside | C. otophyllum | Rhizome | [49] |

| 180 | Caudatin 3-O-β-d-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-α-d-oleandropyranosyl-(1→4)-α-l-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-glucopyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-oleandropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-diginopyranoside | C. otophyllum | Rhizome | [49] |

| 181 | Caudatin 3-O-β-d-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranoside | C. otophyllum | Roots | [16] |

| 182 | Caudatin 3-O-β-d-glucopyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-oleandropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranoside | C. otophyllum | Roots | [16] |

| 183 | Caudatin 3-O-β-d-glucopyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-α-l-diginopyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranoside | C. wilfordii. | Roots | [50] |

| 184 | Caudatin 3-O-β-d-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-oleandropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranoside | C. otophyllum | Roots | [46] |

| 185 | Caudatin-3-O-β-d-oleandropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-thevetopyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranoside | C. otophyllum | Roots | [46] |

| 186 | Caudatin-3-O-β-d-thevetopyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranoside | C. otophyllum | Roots | [46] |

| 187 | Caudatin-3-O-β-d-thevetopyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-digitoxopyranoside. | C. otophyllum | Roots | [46] |

| 188 | Caudatin-3-O-β-d-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-oleandropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-digitoxopyranoside | C. otophyllum | Roots | [46] |

| 189 | Caudatin-3-O-α-l-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-α-d-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-α-l-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-digitoxopyranoside | C. otophyllum | Roots | [46] |

| 190 | Caudatin 3-O-β-d-oleandropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-thevetopyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranoside | C. otophyllum | Roots | [46] |

| 191 | Caudatin 3-O-α-l-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-α-l-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-digitoxopyranoside. | C. otophyllum | Roots | [46] |

| 192 | Caudatin 3-O-α-l-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-α-l-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-oleandropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranoside | C. otophyllum | Roots | [46] |

| 193 | Caudatin 3-O-β-d-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-oleandropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranoside | C. otophyllum | Roots | [46] |

| 194 | Caudatin 3-O-β-d-oleandropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-digitoxopyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranoside | C. otophyllum | Roots | [46] |

| 195 | Caudatin 3-O-β-d-oleandropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-digitoxopyranoside | C. otophyllum | Roots | [46] |

| 196 | Caudatin 3-β-d-digitoxopyranoside | C. otophyllum | Roots | [47] |

| 197 | Caudatin 3-O-α-l-diginopyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranoside | C. otophyllum | Roots | [47] |

| 198 | Caudatin 3-O-β-d-glucopyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-digitoxopyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-diginopyranosyl-(1→4)-α-d-oleandropyranoside | C. otophyllum | Rhizome | [51] |

| 199 | Caudatin3-O-β-d-oleandropyranosyl-(1→4)-α-d-oleandropyranosyl-(1→4)-α-d-oleandropyranoside | C. otophyllum | Rhizome | [51] |

| 200 | Caudatin3-O-β-d-glucopyranosyl-(1→4)-α-d-oleandropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-diginopyranosyl-(1→4)-α-d-oleandropyranoside | C. otophyllum | Rhizome | [51] |

| 201 | Qingyangshengenin | C. wilfordii. | Roots | [9] |

| 202 | Qingyangshengenin 3-O-β-d-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-digitoxopyranoside | C. otophyllum | Roots | [16] |

| 203 | Qingyangshengenin 3-O-β-d-oleandropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranoside | C. otophyllum | Roots | [16] |

| 204 | Qingyangshengenin 3-O-β-d-oleandropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-digitoxopyranoside | C. otophyllum | Roots | [16] |

| 205 | Qingyangshengenin 3-O-β-d-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-thevetopyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-digitoxopyranoside | C. otophyllum | Roots | [46] |

| 206 | Qingyangshengenin 3-O-α-l-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-oleandropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranoside | C. otophyllum | Roots | [46] |

| 207 | Qingyangshengenin 3-O-α-l-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-α-l-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-oleandropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranoside | C. otophyllum | Roots | [46] |

| 208 | Qinyangshengenin-3-O-β-d-oleandropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-oleandropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranoside | C. otophyllum | Roots | [52] |

| 209 | Qinyangshengenin-3-O-α-l-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-oleandropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-digitoxopyranoside | C. wallichii | Roots | [53] |

| 210 | Deacymetaplexigenin | C. wilfordii | Roots | [9] |

| 211 | 12-O-vanilloyl-deacymetaplexigenin | C. wilfordii. | Roots | [9] |

| 212 | 12-O-benzoyldeacymetaplexigenin | C. wilfordii. | Roots | [9] |

| 213 | 17β-O-cinnamoyl-3β,8β,14β-trihydroxypregn-12,20-ether | C. wilfordii. | Roots | [9] |

| 214 | Gagamine 3-O-β-d-oleandropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranoside | C. otophyllum | Roots | [46] |

| 215 | Gagaminin 3-O-β-d-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-oleandropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranoside | C. wilfordii | Roots | [54] |

| 216 | Gagaminin 3-O-β-l-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-α-l-diginopyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-digitoxopyranoside | C. bungei | Stems | [21] |

| 217 | Gagaminin 3-O-β-l-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-α-l-diginopyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranoside | C. bungei | Stems | [21] |

| 218 | Gagaminine 3-O-β-d-oleandropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-oleandropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranoside | C. saccatum | Roots | [55] |

| 219 | Gagaminin 3-O-α-l-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-α-l-diginopyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-digitoxopyranoside | C. wilfordii. | Roots | [50] |

| 220 | Gagaminin-3-O-β-d-oleandropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-digitoxopyranoside | C. otophyllum | Roots | [46] |

| 221 | 12β-O-benzoyl-8β,14β,17β-trihydroxypregn-2,5-diene-20-one | C. wilfordii. | Roots | [9] |

| 222 | Rostratamin | C. wilfordii. | Roots | [9] |

| 223 | Rostratamine 3-O-β-d-oleandropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranoside | C. otophyllum | Roots | [16] |

| 224 | Sarcostin | C. otophyllum | Roots | [47] |

| 225 | 12-O-nicotinoylsarcostin3-O-β-l-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-α-l-diginopyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranoside | C. bungei | Stems | [21] |

| 226 | 12-O-acetylsarcostin 3-O-β-lcymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-l-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-digitoxopyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-digitoxopyranoside | C. bungei | Stems | [21] |

| 227 | 12-O-acetylsarcostin3-O-β-l-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-digitoxopyranosyl-(1→4)-β-l-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-α-l-diginopyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranoside | C. bungei | Stems | [21] |

| 228 | 20-O-acetyl-12-O-cinnamoyl-3-O-(β-d-oleandropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-oleandropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranosyl)-8,14-secosarcostin-8,14-dione | C. saccatum | Roots | [56] |

| 229 | Deacylcynanchogenin | C. wilfordii | Roots | [9] |

| 230 | Cynauricuoside A | C. wilfordii | Roots | [27] |

| 231 | Cynauricuoside C | C. auriculatum | Root | [57] |

| 232 | Cynanside A | C. aniculatum | Roots | [58] |

| 233 | Cynanside B | C. aniculatum | Roots | [58] |

| 234 | Komaroside C | C. forrestii | Roots | [59] |

| 235 | Komaroside D | C. komarovii | Roots | [33] |

| 236 | Komaroside E | C. komarovii | Roots | [33] |

| 237 | Komaroside F | C. komarovii | Roots | [33] |

| 238 | Komaroside G | C. komarovii | Roots | [33] |

| 239 | Komaroside H | C. komarovii | Roots | [33] |

| 240 | Cynauricoside A | C. wilfordii. | Roots | [50] |

| 241 | Cynauricoside B | C. auriculatum | Roots | [30] |

| 242 | Cynauricoside C | C. auriculatum | Roots | [30] |

| 243 | Cynauricoside D | C. auriculatum | Roots | [30] |

| 244 | Cynauricoside E | C. auriculatum | Roots | [30] |

| 245 | Cynauricoside F | C. auriculatum | Roots | [30] |

| 246 | Cynauricoside G | C. auriculatum | Roots | [30] |

| 247 | Cynauricoside H | C. auriculatum | Roots | [30] |

| 248 | Cynauricoside I | C. auriculatum | Roots | [30] |

| 249 | Cynauricuside A | C. auriculatum | Roots | [30] |

| 250 | Cynaforroside B | C. forrestii | Roots | [59] |

| 251 | Cynaforroside C | C. forrestii | Roots | [59] |

| 252 | Cynaforroside D | C. forrestii | Roots | [59] |

| 253 | Cynaforroside E | C. forrestii | Roots | [59] |

| 254 | Cynaforroside F | C. forrestii | Roots | [59] |

| 255 | Cynaforroside G | C. forrestii | Roots | [59] |

| 256 | Cynaforroside H | C. forrestii | Roots | [59] |

| 257 | Cynaforroside I | C. forrestii | Roots | [59] |

| 258 | Cynaforroside J | C. forrestii | Roots | [59] |

| 259 | Cynaforroside K | C. forrestii | Roots | [60] |

| 260 | Cynaforroside L | C. forrestii | Roots | [60] |

| 261 | Cynaforroside M | C. forrestii | Roots | [60] |

| 262 | Cynaforroside N | C. forrestii | Roots | [60] |

| 263 | Cynaforroside O | C. forrestii | Roots | [60] |

| 264 | Cynaforroside P | C. forrestii | Roots | [60] |

| 265 | Cynaforroside Q | C. forrestii | Roots | [60] |

| 266 | Atratoglaucoside A | C. atratum C. versicolor | Roots | [39] |

| 267 | Atratoglaucoside B | C. atratum | Roots | [39] |

| 268 | Paniculatumoside A | C. paniculatum . | Roots | [61] |

| 269 | Paniculatumoside B | C. paniculatum . | Roots | [61] |

| 270 | Neohancoside C | C. hunmkiunum | Roots | [62] |

| 271 | Neohancoside D | C. hunmkiunum | Roots | [62] |

| 272 | Deoxyamplexicogenin A-3-O-yl-4-O-(4-O-α-l-cymaropyranosoyl-β-d-digitoxopyranosoyl)-β-d-canaropyranoside | C. stauntonii | Roots | [63] |

| 273 | 2-deoxyamplexicogenin A | C. stauntonii | Roots | [64] |

| 274 | Amplexicogenin C-3-O-β-d-cymaropyranoside | C. amplexicaule | Roots | [65] |

| 275 | Cynascyroside A | C. ascyrifolium | Roots | [66] |

| 276 | Cynascyroside B | C. ascyrifolium | Roots | [66] |

| 277 | Cynascyroside C | C. ascyrifolium C. chekiangense | Roots | [66] |

| 278 | Cynascyroside D | C. atratum | Roots | [25] |

| 279 | Taiwanoside A | C. taiwanianum | Roots | [28] |

| 280 | Taiwanoside B | C. taiwanianum | Roots | [28] |

| 281 | Taiwanoside C | C. taiwanianum | Roots | [28] |

| 282 | Taiwanoside D | C. taiwanianum | Roots | [28] |

| 283 | Taiwanoside E | C. taiwanianum | Roots | [28] |

| 284 | Stauntonine | C. stauntonii | Roots | [40] |

| 285 | Anhydrohirundigenin | C. stauntonii | Roots | [40] |

| 286 | Anhydrohirundigenin monothevetoside | C. stauntonii | Roots | [40] |

| 287 | Auriculoside I | C. auriculatum | Roots | [29] |

| 288 | Auriculoside II | C. auriculatum | Roots | [29] |

| 289 | Auriculoside III | C. auriculatum | Roots | [29] |

| 290 | Auriculoside IV | C. auriculatum | Roots | [29] |

| 291 | Cynanauriculoside I | C. auriculatum | Roots | [29] |

| 292 | Cynanauriculoside II | C. auriculatum | Roots | [29] |

| 293 | Cynanauriculoside A | C. wallichii | Roots | [53] |

| 294 | Cynanauriculoside C | C. auriculatum | Roots | [67] |

| 295 | Cynanauriculoside D | C. auriculatum | Roots | [67] |

| 296 | Cynanauriculoside E | C. auriculatum | Roots | [67] |

| 297 | (3β,8β,9α,16α,17α)-14,16β:15,20α:18,20β-triepoxy-16α,17α-dihydroxy-14-oxo-13,14:14,15-disecopregna-5,13(18)-dien-3-yl α-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-α-digitoxopyranosyl-(1→4)-α-oleandropyranoside | C. paniculatum | Stems | [68] |

| 298 | (3β,8β,9α,16α,17α)-14,16β:15,20α:18,20β-triepoxy-16β:17α-dihydroxy-14-oxo-13,14:14,15-disecopregna-5,13(18)-dien-3-yl α-oleandropyranosyl-(1→4)-α-digitoxopyranosyl-(1→4)-α-oleandropyranoside | C. paniculatum | Stems | [68] |

| 299 | Cyanoauriculoside C | C. auriculatum | Roots | [69] |

| 300 | Cyanoauriculoside D | C. auriculatum | Roots | [69] |

| 301 | Cyanoauriculoside E | C. auriculatum | Roots | [69] |

| 302 | Cyanoauriculoside G | C. wilfordii. | Roots | [50] |

| 303 | Hirundoside A | C. stauntonii | Roots | [43] |

| 304 | Deacetylmetaplexigenin | C. otophyllum | Roots | [47] |

| 305 | Deacetylmetaplexigenin 3-O-β-d-oleandropyranosyl-(1→4)-α-d-oleandropyranosyl-(1→4)-α-d-oleandropyranoside | C. otophyllum | Rhizome | [70] |

| 306 | Deacetylmetaplexigenin 3-O-α-d-oleandropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-thevetopyranosyl-(1→4)-α-d-oleandropyranoside | C. otophyllum | Rhizome | [70] |

| 307 | Deacetylmetaplexigenin 3-O-β-d-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-α-d-oleandropyranoside | C. otophyllum | Rhizome | [70] |

| 308 | Cynsaccatol A | C. saccatum | Roots | [55] |

| 309 | Cynsaccatol B | C. saccatum | Roots | [55] |

| 310 | Cynsaccatol C | C. saccatum | Roots | [55] |

| 311 | Cynsaccatol D | C. saccatum | Roots | [55] |

| 312 | Cynsaccatol E | C. saccatum | Roots | [55] |

| 313 | Cynsaccatol F | C. saccatum | Roots | [55] |

| 314 | Cynsaccatol G | C. saccatum | Roots | [55] |

| 315 | Cynsaccatol H | C. saccatum | Roots | [55] |

| 316 | Cynotophylloside A | C. otophyllum. | Roots | [47] |

| 317 | Cynotophylloside B | C. otophyllum. | Roots | [47] |

| 318 | Cynotophylloside C | C. otophyllum. | Roots | [47] |

| 319 | Cynotophylloside D | C. otophyllum. | Roots | [47] |

| 320 | Cynotophylloside E | C. otophyllum. | Roots | [47] |

| 321 | Cynotophylloside F | C. otophyllum. | Roots | [47] |

| 322 | Cynotophylloside H | C.otophyllum | Roots/stems | [71] |

| 323 | Stephanoside H | C. otophyllum | Roots | [46] |

| 324 | Wallicoside | C. otophyllum | Roots | [18] |

| 325 | Wallicoside J | C. otophyllum | Roots | [46] |

| 326 | Cynawilfoside A | C. wilfordii. | Roots | [50] |

| 327 | Cynawilfoside B | C. wilfordii. | Roots | [50] |

| 328 | Cynawilfoside C | C. wilfordii. | Roots | [50] |

| 329 | Cynawilfoside D | C. wilfordii. | Roots | [50] |

| 330 | Cynawilfoside E | C. wilfordii. | Roots | [50] |

| 331 | Cynawilfoside F | C. wilfordii. | Roots | [50] |

| 332 | Cynawilfoside G | C. wilfordii. | Roots | [50] |

| 333 | Cynawilfoside H | C. wilfordii. | Roots | [50] |

| 334 | Cynawilfoside I | C. wilfordii. | Roots | [50] |

| 335 | Atratcynoside A | C. atratum | Roots | [72] |

| 336 | Atratcynoside B | C. atratum | Roots | [72] |

| 337 | Atratcynoside C | C. atratum | Roots | [72] |

| 338 | Atratcynoside D | C. atratum | Roots | [72] |

| 339 | Atratcynoside E | C. atratum | Roots | [72] |

| 340 | Atratcynoside F | C. atratum | Roots | [72] |

| 341 | Mooreanoside A | C. mooreanum | Roots | [73] |

| 342 | Mooreanoside B | C. mooreanum | Roots | [73] |

| 343 | Mooreanoside C | C. mooreanum | Roots | [73] |

| 344 | Mooreanoside D | C. mooreanum | Roots | [73] |

| 345 | Mooreanoside E | C. mooreanum | Roots | [73] |

| 346 | Mooreanoside F | C. mooreanum | Roots | [73] |

| 347 | Mooreanoside G | C. mooreanum | Roots | [73] |

| 348 | Mooreanoside H | C. mooreanum | Roots | [73] |

| 349 | Mooreanoside I | C. mooreanum | Roots | [73] |

| 350 | Mooreanoside J | C. mooreanum | Roots | [73] |

| 351 | Mooreanoside K | C. mooreanum | Roots | [73] |

| 352 | Mooreanoside L | C. mooreanum | Roots | [73] |

| 353 | Mooreanoside M | C. mooreanum | Roots | [73] |

| 354 | Mooreanoside N | C. mooreanum | Roots | [73] |

| 355 | Mooreanoside O | C. mooreanum | Roots | [73] |

| 356 | Mooreanoside P | C. mooreanum | Roots | [73] |

| 357 | Cynastauoside A | C. stauntonii | Roots | [74] |

| 358 | Cynastauoside B | C. stauntonii | Roots | [74] |

| 359 | Cynastauoside C | C. stauntonii | Roots | [74] |

| 360 | Saccatol A | C. saccatum | Roots | [56] |

| 361 | Saccatol B | C. saccatum | Roots | [56] |

| 362 | Saccatol C | C. saccatum | Roots | [56] |

| 363 | Cynanotoside A | C. otophyllum | Roots/stems | [71] |

| 364 | Cynanotoside B | C. otophyllum | Roots/stems | [71] |

| 365 | Cynanotoside C | C. otophyllum | Roots/stems | [71] |

| 366 | Cynanotoside D | C. otophyllum | Roots/stems | [71] |

| 367 | Cynanotoside E | C. otophyllum | Roots/stems | [71] |

| 368 | Mucronatoside C | C. otophyllum | Roots | [46] |

| 369 | Sinomarinoside B | C. otophyllum | Roots | [46] |

| 370 | Cynanotophylloside A | C. otophyllum | Roots | [31] |

| 371 | Cynanotophylloside B | C. otophyllum | Roots | [31] |

| 372 | Cynanotophylloside C | C. otophyllum | Roots | [31] |

| 373 | Cynanotophylloside D | C. otophyllum | Roots | [31] |

| 374 | Cynanauriculatoside A | C. otophyllum | Roots | [31] |

| 375 | 3β,14β-dihydroxy-14β-pregn-5-en-20-one | C. paniculatum. | Root/rhizome | [41] |

| 376 | 3-O-β-d-oleandropanyanoside | C. paniculatum. | Root/rhizome | [41] |

| 377 | Hancopregnane | C. hunmkiunum | Roots | [37] |

| 378 | Menarandroside A | C. menarandrense | Aerial parts | [75] |

| 379 | Menarandroside B | C. menarandrense | Aerial parts | [75] |

| 380 | Menarandroside C | C. menarandrense | Aerial parts | [75] |

| 381 | Menarandroside D | C. menarandrense | Aerial parts | [75] |

| 382 | Menarandroside E | C. menarandrense | Aerial parts | [75] |

| 383 | Carumbelloside I | C. menarandrense | Aerial parts | [75] |

| 384 | Carumbelloside II | C. menarandrense | Aerial parts | [75] |

| 385 | Pregnenolone-3-O-gentiobioside | C. menarandrense | Aerial parts | [75] |

| 386 | 14-O-methyl-3-epi-hirundigenin | C. stauntonii | Roots | [76] |

| 387 | Stauntosaponin A | C. stauntonii | Roots | [77] |

| 388 | Stauntosaponin B | C. stauntonii | Roots | [77] |

| Benzene and its derivatives | ||||

| 389 | Cynantetrone | C. taiwanianum | Rhizome | [78] |

| 390 | CynantetroneA | C. taiwanianum | Rhizome | [78] |

| 391 | Cynandione A | C. taiwanianum | Rhizome | [78] |

| 392 | Cynandione B | C. taiwanianum | Rhizome | [78] |

| 393 | 2,4-Dihydroxyacetophenone | C. atratum | Roots | [25] |

| 394 | 2,5-Dihydroxyacetophenone | C. bungei | Roots | [79] |

| 395 | 4-Hydroxyacetophenone | C. atratum | Roots | [25] |

| 396 | 4-acetylphenol | C. paniculatum | Roots | [80] |

| 397 | 2,5-dihydroxy-4-methoxyacetophenone | C. paniculatum | Roots | [80] |

| 398 | 2,3-dihydroxy-4-methoxyacetophenone | C. paniculatum | Roots | [81] |

| 399 | Acetoveratrone | C. paniculatum | Roots | [80] |

| 400 | 2,5-dimethoxyhydroquinone | C. paniculatum | Roots | [80] |

| 401 | Resacetophenone | C. paniculatum | Roots | [80] |

| 402 | M-acetylphenol | C. paniculatum | Roots | [80] |

| 403 | Vanillic acid | C. paniculatum | Roots | [80] |

| 404 | 3,5-dimethoxyhydroquinone | C. paniculatum | Roots | [80] |

| 405 | Acetovanillone | C. wilfordii | Roots | [3] |

| 406 | p-hydroxyacetophenone | C. wilfordii | Roots | [3] |

| 407 | 3-(β-d-ribofuranosyl)-2,3-dihydro-6H-1,3-oxazine-2,6-dione | C. wilfordii | Roots | [3] |

| 408 | Bungeiside A | C. wilfordii | Roots | [3] |

| 409 | Cynanoneside B | C. wilfordii | Roots | [3] |

| 410 | Cynanoneside A | C. taiwanianum | Roots | [82] |

| 411 | Baishouwubenzophenone | C. auriculatum | Roots | [83] |

| 412 | 3,4-dihydroxyacetophenone | C. atratum | Roots | [39] |

| 413 | 4′-hydroxy-3′-methoxyacetophenone | C. wilfordii | Roots | [84] |

| 414 | Paeonol | C. auriculatum | Roots | [58] |

| 415 | Isopaeonol | C. auriculatum | Roots | [58] |

| 416 | 2-hydroxy-5-methoxyacetophenone | C. auriculatum | Roots | [58] |

| 417 | Caffeic acid | C. taiwanianum | Aerial parts | [85] |

| 418 | Syringic acid | C. paniculatum | Roots | [86] |

| Alkaloids | ||||

| 419 | Gagamine | C. caudatum | Roots | [87] |

| 420 | Antofine | C. vincetoxicum | Aerial parts | [88] |

| 421 | Tylophorine | C. vincetoxicum | Aerial parts | [88] |

| 422 | Vincetene | C. vincetoxicum | Aerial parts | [88,89] |

| 423 | (-)-10β,13aα-14β-hydroxyantofine N-oxide | C. vincetoxicum | Aerial parts | [90] |

| 424 | (-)-10β,13aα-secoantofine N-oxide | C. vincetoxicum | Aerial parts | [90] |

| 425 | (-)-(R)-13aα-6-O-desmethylantofine | C. vincetoxicum | Aerial parts | [91] |

| 426 | (-)-(R)-13aα-secoantofine | C. vincetoxicum | Aerial parts | [91] |

| 427 | (-)-(R)-13aα-6-O-desmethylsecoantofine | C. vincetoxicum | Aerial parts | [91] |

| 428 | (-)-10β-antofine N-oxide | C. vincetoxicum | Aerial parts | [90] |

| 429 | 2,3-dimethoxy-6-(3-oxo-butyl)-7,9,10,11,11a,12-hexahydrobenzo[f]pyrrolo[1,2-b]isoquinoline | C. komarovii | Aerial parts | [92] |

| 430 | 7-demethoxytylophorine | C. komarovii | Aerial parts | [92] |

| 431 | 7-demethoxytylophorine N-oxide | C. komarovii | Aerial parts | [92] |

| Flavones | ||||

| 432 | 7-O-α-l-rhamnopyranosyl-kaempferol-3-O-β-d-glucopyranoside | C. chinese | Aerial parts | [93] |

| 433 | 7-O-α-l-rhamnopyranosyl-kaempferol-3-O-α-l-rhamnopyranoside | C. chinese | Aerial parts | [93] |

| 434 | Kaempferol | C. taiwanianum | Aerial parts | [85] |

| 435 | Astragalin | C. taiwanianum | Aerial parts | [85] |

| 436 | Afzelin | C. taiwanianum | Aerial parts | [85] |

| 437 | Trifolin | C. taiwanianum | Aerial parts | [85] |

| 438 | Quercetin | C. taiwanianum | Aerial parts | [85] |

| 439 | Isoquercitrin | C. taiwanianum | Aerial parts | [85] |

| 440 | Quercitrin | C. taiwanianum | Aerial parts | [85] |

| 441 | Hyperin | C. taiwanianum | Aerial parts | [85] |

| Terpene | ||||

| 442 | Neohancoside A | C. hunmkiunum | Roots | [34] |

| 443 | Neohancoside B | C. hunmkiunum | Roots | [62] |

| 444 | β-amyrin | C. paniculatum | Roots | [86] |

| 445 | α-amyrin | C. paniculatum | Roots | [86] |

| 446 | Lupeol | C. paniculatum | Roots | [86] |

| 447 | Taraxasterol | C. paniculatum | Roots | [86] |

| 448 | Ursolic acid | C. paniculatum | Roots | [86] |

| 449 | Oleanolic acid | C. paniculatum | Roots | [86] |

| 450 | Maslinic acid | C. paniculatum | Roots | [86] |

| Cynanchum Species | Extract/Isolate | Plant Part | In Vitro/In Vivo | Dosage/Duration | Model/Effect | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-cancer | ||||||

| C. taiwanianum | Cynantetrone, cynandione B | Rhizome | In vitro | Compounds against T-24 cell lines with ED50 values of ca. 3.5 and 2.5 μg/mL, respectively, and cynandione B against PLC/PRF/5 cell lines (ED50 = 2.7 μg/mL). | [78] | |

| C.auriculatum | Ethanol extract, Petroleumether, CHCl3, EtOAc and n-BuOH fraction | Root tubers | In vitro | 1 μg/mL | The ethanol extract against K562, with the highest inhibition ratio of 24.06% at a concentration of 1 μg/mL. | [96] |

| In vivo | 100 mg/kg/Gavage 7 d | The ethanol extract and n-BuOH fraction showed significant antitumor activity by inhibiting the growth of sarcoma S180 in mice with an inhibition ratio of 42.22% and 41.50%. | ||||

| C. auriculatum | Total glucosides | In vivo | 225 mg/kg 10 d | Model: C57BL/6 mice bearing Lewis lung carcinoma. The inhibition rate of tumor weight was 38.68% the inhibition rate of lung metastasis was 63.64%. | [97] | |

| C.auriculatum | Caudatin, caudatin-2,6-dideoxy-3-O-methy-β-d-cymaropyranoside | Root tubers | In vitro | 12 μM | Model: Human tumor cell line SMMC–7721. IC50 = 24.95 μM; IC50 = 13.49 μM | [48] |

| In vivo | 10, 20, 40 mg/Kg 9 d | Model: Transplantable H22 tumors in mice. The growth of transplantable H22tumors in mice was inhibited. | ||||

| C.auriculatum | Kidjoranin 3-O-α-diginopyranosyl-(1→4)-β-cymaropyranoside, kidjoranin 3-O-β-digitoxopyranoside, caudatin 3-O-β-cymaropyranoside | Roots | In vitro | Model: SMMC-7721 and HeLa cell lines. IC50 = 8.6 μM–58.5 μM. | [98] | |

| C. auriculatum | Auriculoside A, auriculoside B | Roots | In vitro | Have significant cytoxicity against PC3, Hce-8693, Hela, and PAA cell lines. | [99] | |

| C. vincetoxicum | Alkaloids | Overground | In vitro | These alkaloids inhibit growth of the hormone in dependent breast cancer cells MDA-MB 231. | [88] | |

| C. paniculatum | Neocynapanogenin F, neocynapanogenin F 3-O-β-d-thevetoside | Roots | In vitro | 100 μg/mL | These compounds exhibited significant cytotoxic activity on HL-60. The inhibitory rate (%, n = 6) was 74.18% and 97.87%, respectively. | [35] |

| C. paniculatum | Cynanside A, Cynanside B | Roots | In vitro | Model: SK-MEL-2 cells. IC50 values = 26.55 μM; IC50 values = 17.36 μM | [58] | |

| C. paniculatum | Antofine | Roots | In vitro | Ellipticine: IC50 = 500 ± 25 ng/mL | Model: Human lung cancer cells A549. IC50 = 7.0 ± 0.2 ng/mL | [100] |

| Ellipticine: IC50 = 340 ± 35 ng/mL | Model: Human colon cancer cells Col2. IC50 = 8.6 ± 0.3 ng/mL | |||||

| C. wilfordii | 20-O-salicyl-kidjoranin | Roots | In vitro | Adriamycin | Model: Human leukemia cell lines HL-60, K562 and breast cancer cell lines MCF-7. The compound can against HL-60 (IC50 = 6.72 μM) and MCF-7 (IC50 = 2.89 μM). | [9] |

| Qingyangshengenin | The compound can against K-562 (IC50 = 6.72 μM). | |||||

| Rostratamin | The compound can against MCF-7 (IC50 = 2.49 μM). | |||||

| C. wilfordii | Gagaminin 3-O-β-d-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-oleandropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-cymaropyranoside | Roots | In vitro | 1 μM | Model: KB-V1 and MCF7/ADR cells. The compounds completely reverse the multidrug-resistance of KB-V1 and MCF7/ADR cells to Adriamycin, vinblastine, and colchicine. | [54] |

| C. atratum | Glaucogenin C 3-O-β-d-cymaropyranosyl-(1→4)-α-l-diginopyranosyl-(1→4)-β-d-thevetopyranoside | Roots | In vitro | Dexamethasone: 10 μM, compound: 30 μM | Model: 212 cells, RAW 264.7 mouse macrophage-like cell, N9 microglial cell. ED50 value of against 212 cells was 0.96 μg/mL and significant inhibitory on TNF-α formation. | [39] |