Native Quercetin as a Chloride Receptor in an Organic Solvent

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

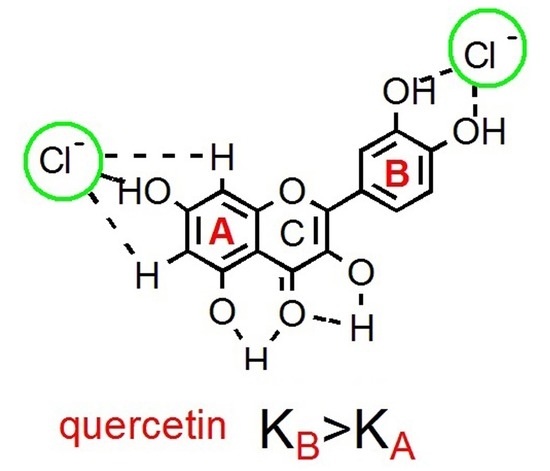

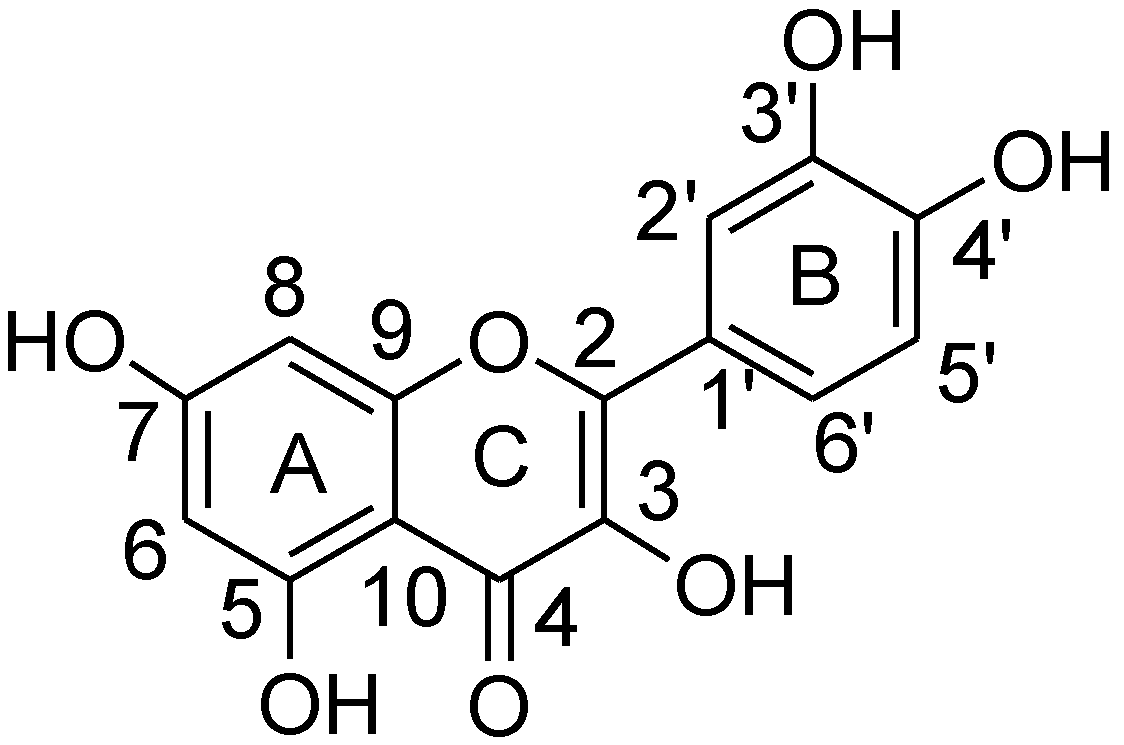

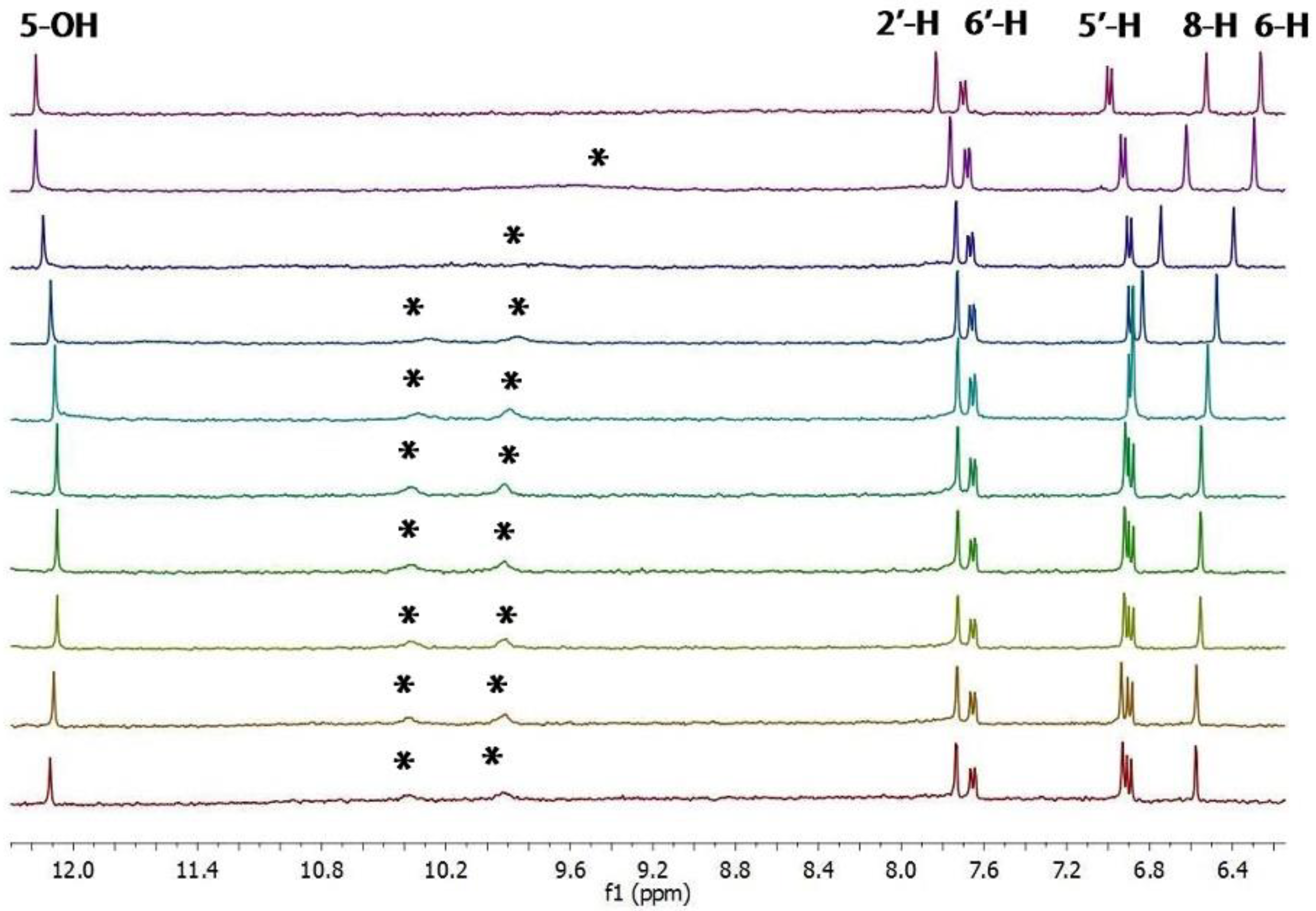

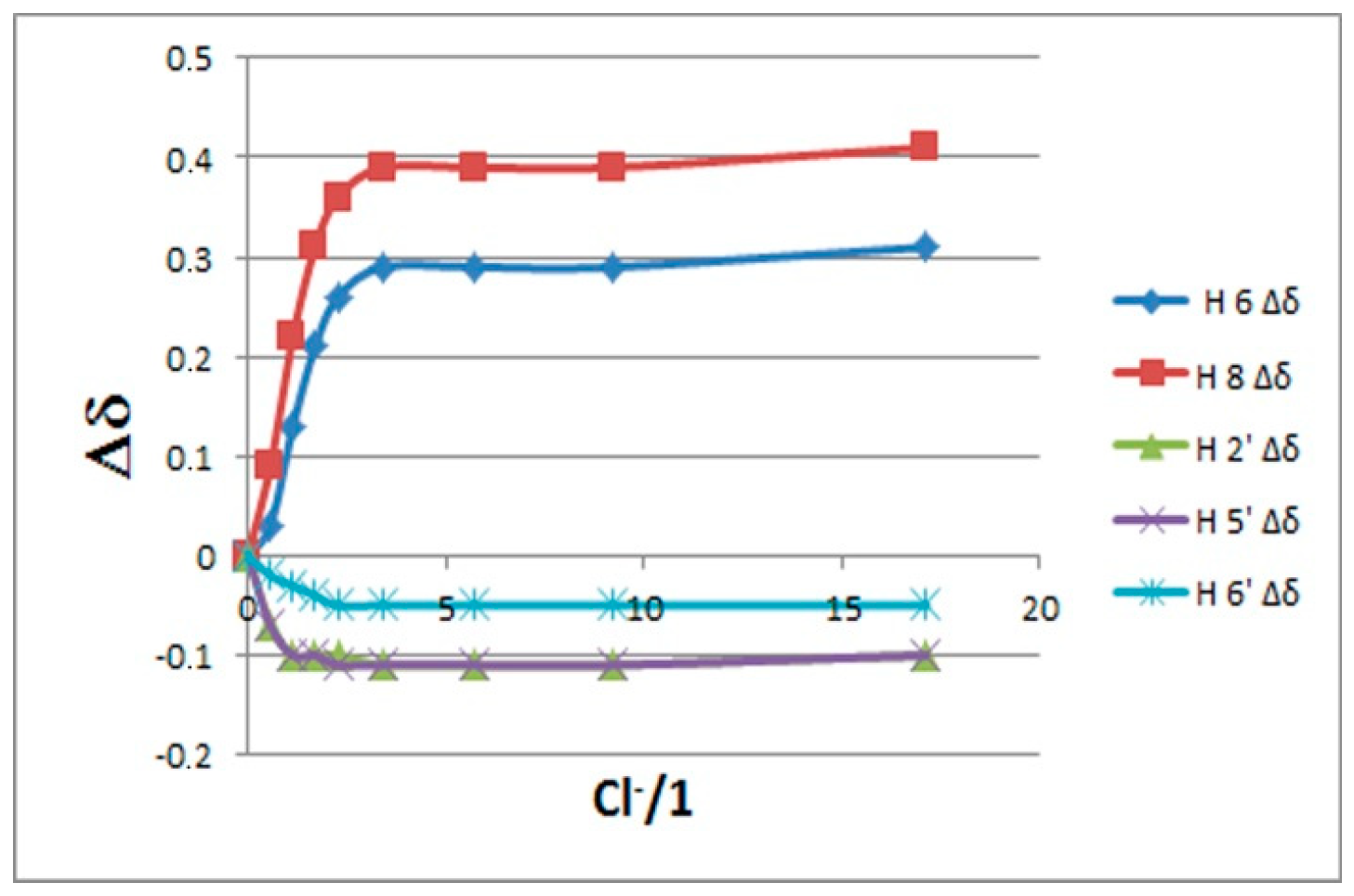

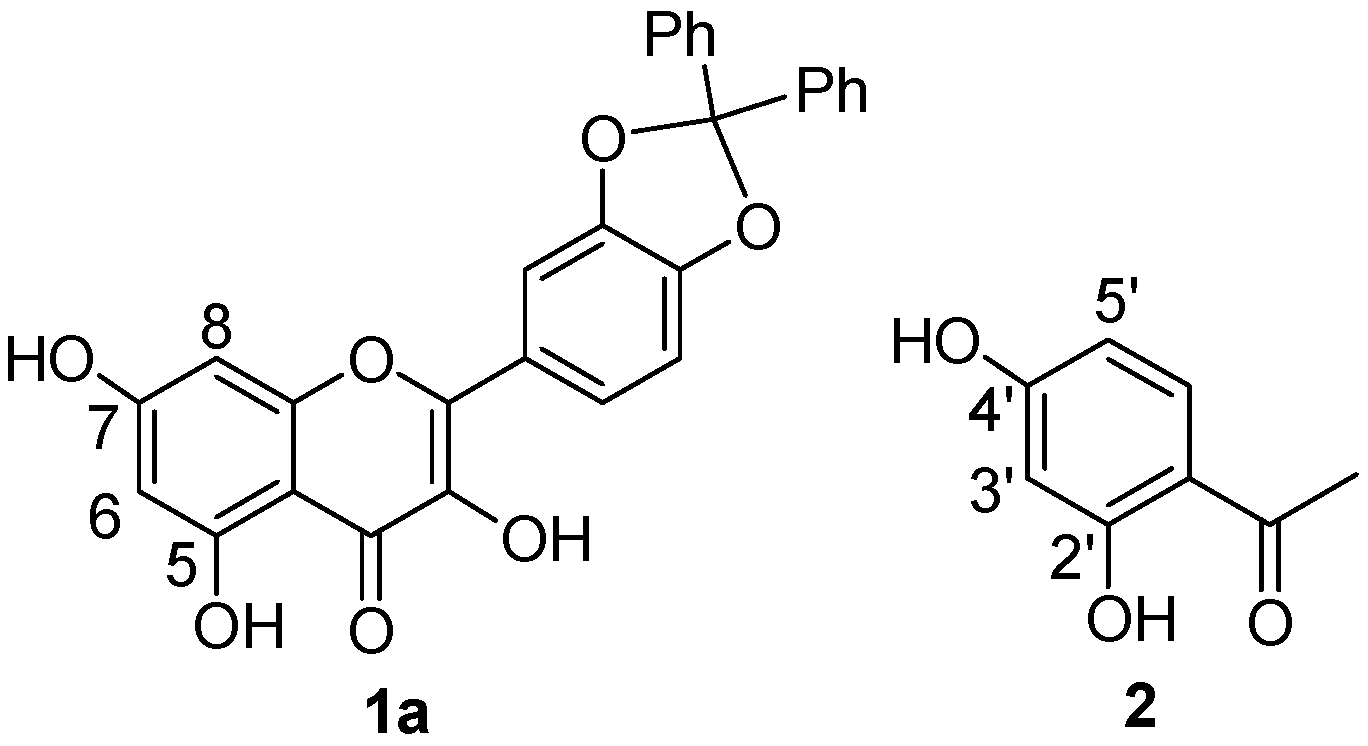

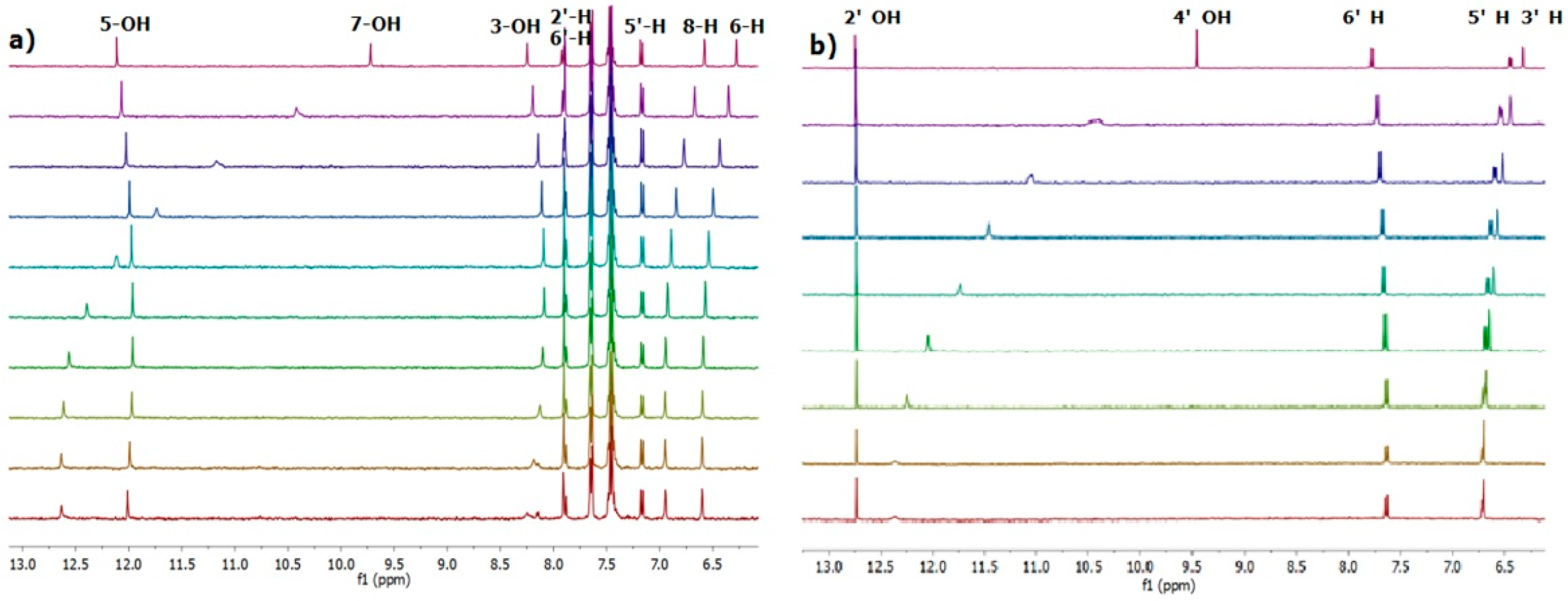

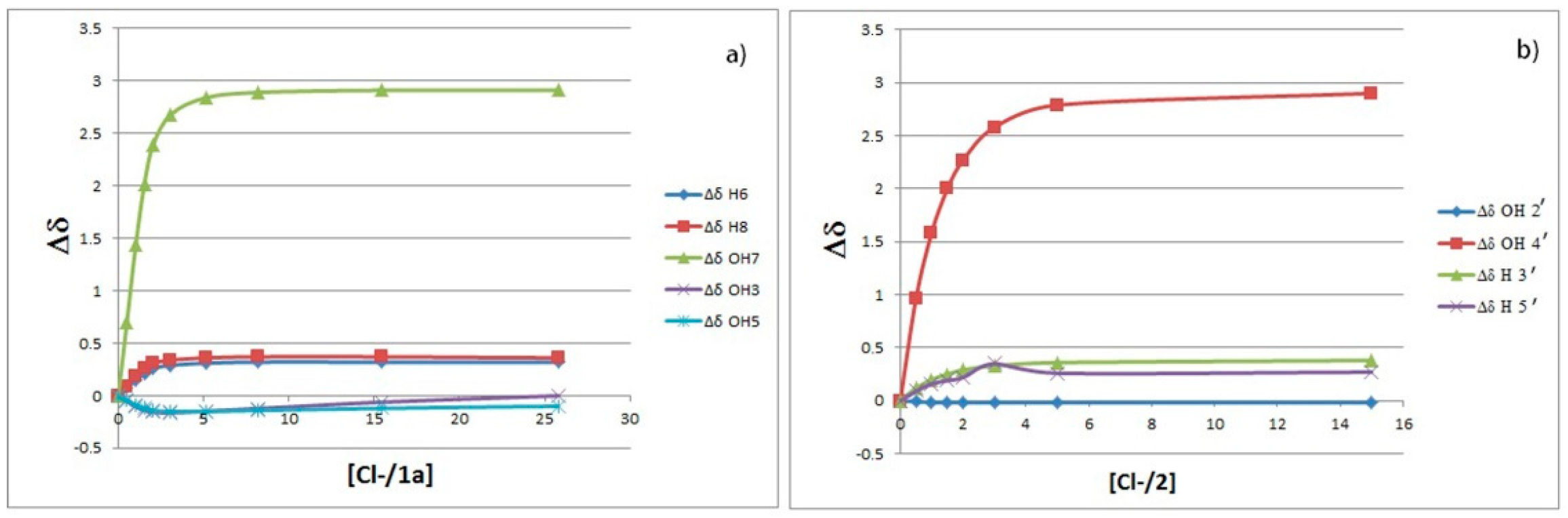

2.1. 1H-NMR Binding Studies

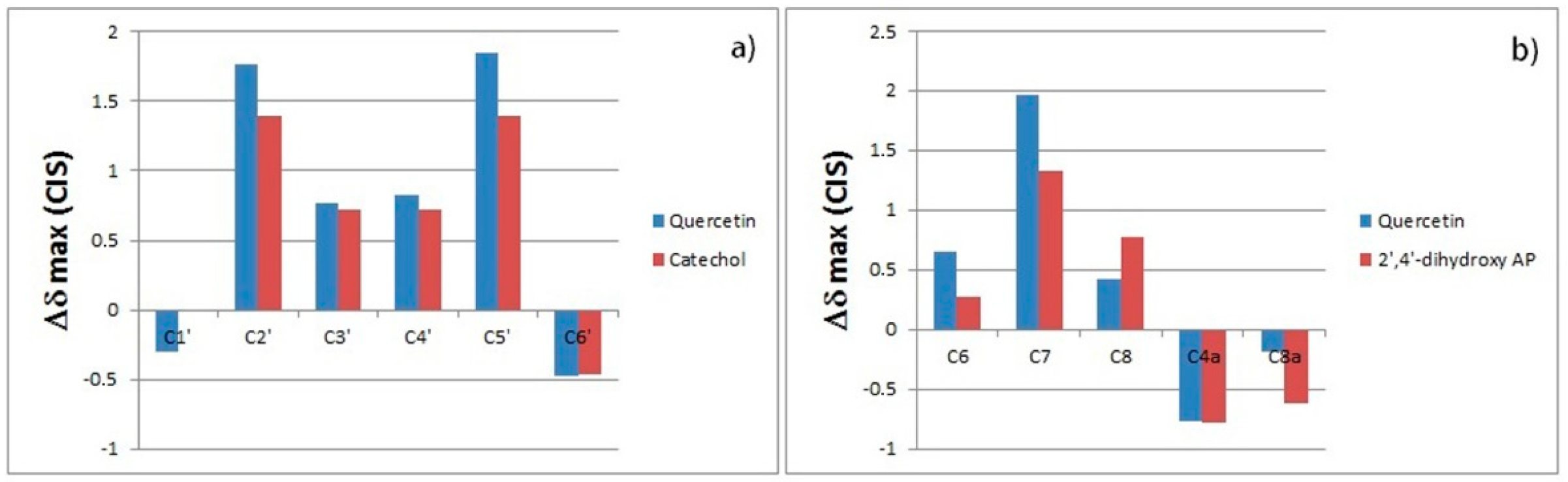

2.2. 13C-NMR and ESI-MS Binding Studies

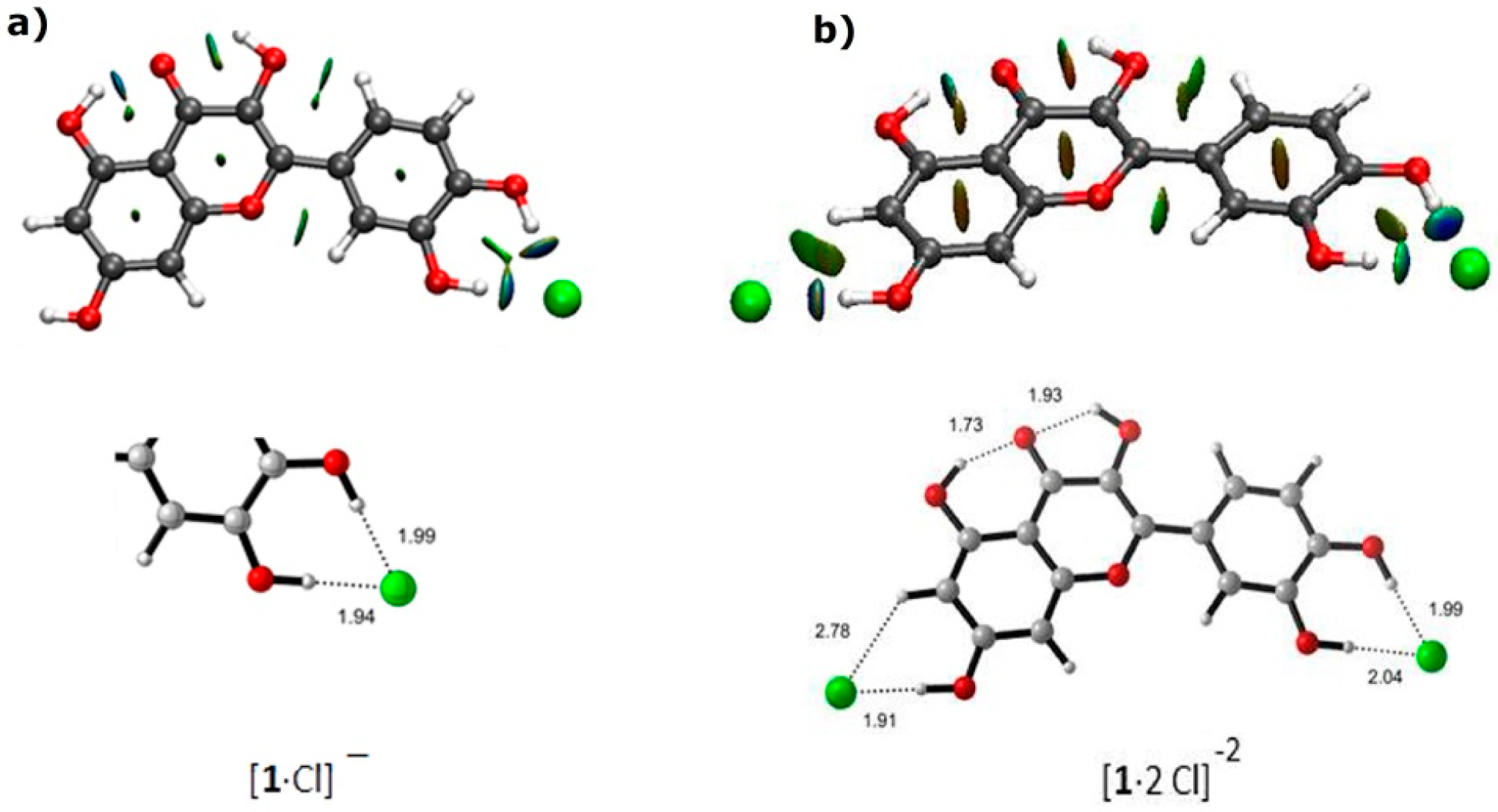

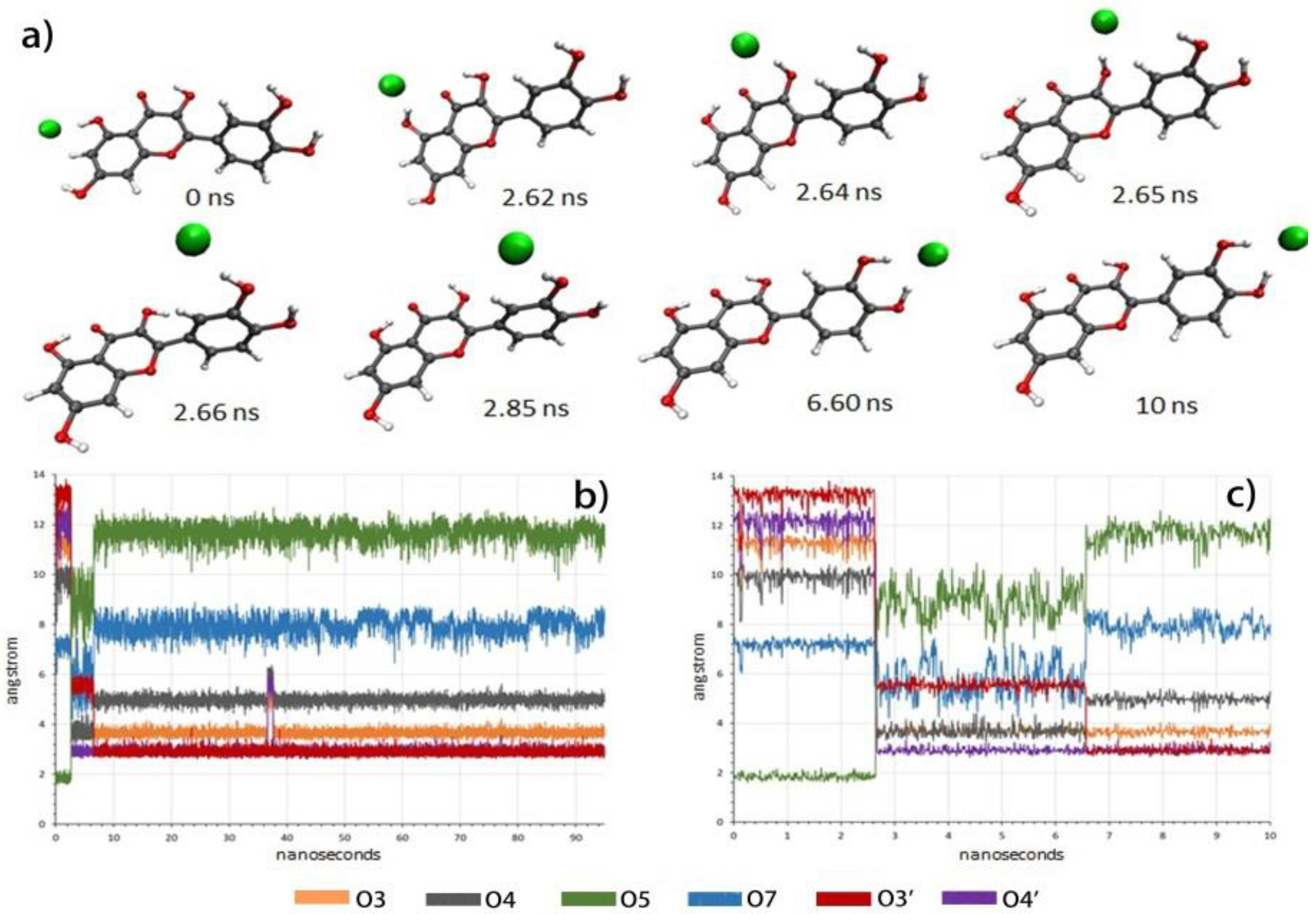

2.3. Molecular Modeling

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General Comments

3.2. 1H-NMR Titration

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References and Notes

- Gale, P.A.; Howe, E.N.W.; Wu, X. Anion receptor chemistry. Chem 2016, 1, 351–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, P.A.; Garcia-Garrido, S.E.; Garric, J. Anion receptors based on organic frameworks: Highlights from 2005 and 2006. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008, 37, 151–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oshovsky, G.V.; Reinhoudt, D.N.; Verboom, W. Supramolecular Chemistry in Water. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 2366–2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunnlaugsson, T.; Glynn, M.; Tocci, G.M.; Kruger, P.E.; Pfeffer, F.M. Anion recognition and sensing in organic and aqueous media using luminescent and colorimetric sensors. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2006, 250, 3094–3117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sessler, J.L.; Camiolo, S.; Gale, P.A. Pyrrolic and polypyrrolic anion binding agents. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2003, 240, 17–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, P.A. Anion receptor chemistry: Highlights from 1999. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2001, 213, 79–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.T.; Okunola, O.; Quesada, R. Recent advances in the transmembrane transport of anions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 3843–3862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowe, S.M.; Miller, S.; Sorscher, E.J. Cystic Fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 352, 1992–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantin, G.; Fogagnolo, M.; Delso, I.; Merino, P. Exploratory spectroscopic and computational studies of the anion binding properties of methyl hyocholate in organic solvent. Tetrahedron 2017, 73, 1698–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winstanley, K.J.; Sayer, A.M.; Smith, D.K. Anion binding by catechols an NMR, optical and electrochemical study. Org. Biol. Chem. 2006, 4, 1760–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winstanley, K.J.; Smith, D.K. Ortho-substituted catechol derivatives: The effect of intramolecular hydrogen-bonding pathways on chloride anion recognition. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 72, 2803–2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Dijk, C.; Driessen, A.; Recourt, K. The uncoupling efficiency and affinity of flavonoids for vesicles. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2000, 60, 1593–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlikowska-Pawlęga, B.; Gruszecki, W.I.; Misiak, L.; Paduch, R.; Piersiak, T.; Zarzyka, B.; Pawelec, J.; Gawron, A. Modification of membranes by quercetin, a naturally occurring flavonoid, via its incorporation in the polar head group. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2007, 1768, 2195–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, R.F.V.; De Giovani, W.F. Antioxidant properties of complexes of flavonoids with metal ions. Redox Rep. 2004, 9, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naso, L.; Valcarcel, M.; Villacé, P.; Roura-Ferrer, M.; Salado, C.; Ferrer, E.G.; Williams, P.A.M. Specific antitumor activities of natural and oxovanadium (IV) complexed flavonoids in human breast cancer cells. N. J. Chem. 2014, 38, 2414–2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parveen, S.; Tabassum, S.; Arjmand, F. Human topoisomerase I mediated cytotoxicity profile of l-valine-quercetin diorganotin (IV) antitumor drug entities. J. Organomet. Chem. 2016, 823, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, M.; Yin, H.; Zhang, X.; Li, C.; Yue, C.; Cheng, S. Di- and tri-organotin (IV) complexes with 2-hydroxy-1-naphthaldehyde 5-chloro-2-hydroxybenzoylhydrazone: Synthesis, characterization and in vitro antitumor activities. J. Organomet. Chem. 2013, 724, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabassum, S.; Yadav, S. Investigation of diorganotin (IV) complexes: Synthesis, characterization, in vitro DNA binding studies and cytotoxicity assessment of di-n-butyltin (IV) complex. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2014, 423, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabassum, S.; Zaki, M.; Afzal, M.; Arjmand, F. New modulated design and synthesis of quercetin-CuII/ZnII-Sn2 IV scaffold as anticancer agents: In vitro DNA binding profile, DNA cleavage pathway and Topo-I activity. Dalton Trans. 2013, 42, 10029–10041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Anna, M.M.; Censi, V.; Carrozzini, B.; Caliandro, R.; Denora, N.; Franco, M.; Veclani, D.; Melchior, A.; Tolazzi, M.; Mastrorilli, P. Triphenylphosphane Pt (II) complexes containing biologically active natural polyphenols: Synthesis, crystal structure, molecular modeling and cytotoxic studies. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2016, 163, 346–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, C.; Kapoor, H.C. Antioxidants in fruits and vegetables—The millennium’s health. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2001, 36, 703–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massi, A.; Bortolini, O.; Ragno, D.; Bernardi, T.; Sacchetti, G.; Tacchini, M.; De Risi, C. Research progress in the modification of quercetin leading to anticancer agents. Molecules 2017, 22, 1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rice-Evans, C.A.; Miller, J.; Paganga, G. Antioxidant properties of phenolic compounds. Trends Plant Sci. 1997, 2, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harborne, J.B.; Williams, C.A. Advances in flavonoid research since 1992. Phytochemistry 2000, 55, 481–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Ryu, E.-H. Solvent-tunable binding of hydrophilic and hydrophobic guests by amphiphilic molecular baskets. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 70, 7585–7591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berryman, O.B.; Sather, A.C.; Hay, B.P.; Meisner, J.S.; Johnson, D.W. Solution phase measurement of both weak σ and C−H⋯X− hydrogen bonding interactions in synthetic anion receptors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 10895–10897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charisiadis, P.; Kontogianni, V.G.; Tsiafoulis, C.G.; Tzakos, A.G.; Siskos, M.; Ioannis, P.; Gerothanassis, I.P. 1H-NMR as a structural and analytical tool of intra- and intermolecular hydrogen bonds of phenol-containing natural products and model compounds. Molecules 2014, 19, 13643–13682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frassineti, C.; Ghelli, S.; Gans, P.; Sabatini, A.; Moruzzi, M.S.; Vacca, A. Nuclear magnetic resonance as a tool for determining protonation constants of natural polyprotic bases in solution. Anal. Biochem. 1995, 231, 374–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, A.J.; Long, B.M.; Pfeffer, F.M. Examples of regioselective anion recognition among a family of two-, three-, and four-“Armed” bis-, tris-, and tetrakis(thioureido)[n]polynorbornane hosts. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 8507–8517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leopoldini, M.; Marino, T.; Russo, N.; Toscano, M. Density functional computations of the energetic and spectroscopic parameters of quercetin and its radicals in the gas phase and in solven. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2004, 111, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero-Martínez, J.M.; Sanmartin, M.; Rosés, M.; Bosch, E.; Ràfols, C. Determination of dissociation constants of flavonoids by capillary electrophoresis. Electrophoresis 2005, 26, 1886–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calculated using Advanced Chemistry Development (ACD/Labs) Software V11.02 (©1994-2018 ACD/Labs.).

- Lenevich, S.; Distefano, M.D. NMR-based quantification of organic diphosphates. Anal. Biochem. 2011, 408, 316–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ca. 20–30 eq. of water were present during NMR titrations. (Estimated by integration of the water peak in the deuterated acetone).

- Fielding, L. Determination of association constants (Ka) from solution NMR data. Tetrahedron 2000, 34, 6151–6170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Sample Availability: Samples of the compounds are not available from the authors. |

| Host | β (M−1) a from CH Protons | β (M−1) a from OH Protons |

|---|---|---|

| Quercetin (1) | β1 = 4.59 b (error = 36%) β2 = 2.95 b | n.d. c |

| 1a | β1 = 3.01 b β2 n.d. | β1 = 3.02 b β2 n.d. |

| 2 | β = 3.09 | β = 3.10 |

| Catechol | β = 3.36 | β = 3.29 |

| Resorcinol | β = 2.39 | β = 2.12 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abdi Bellau, M.L.; Bortolini, O.; Fantin, G.; Fogagnolo, M.; Ragno, D.; Delso, I.; Merino, P. Native Quercetin as a Chloride Receptor in an Organic Solvent. Molecules 2018, 23, 3366. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules23123366

Abdi Bellau ML, Bortolini O, Fantin G, Fogagnolo M, Ragno D, Delso I, Merino P. Native Quercetin as a Chloride Receptor in an Organic Solvent. Molecules. 2018; 23(12):3366. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules23123366

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbdi Bellau, Mohamed Lamin, Olga Bortolini, Giancarlo Fantin, Marco Fogagnolo, Daniele Ragno, Ignacio Delso, and Pedro Merino. 2018. "Native Quercetin as a Chloride Receptor in an Organic Solvent" Molecules 23, no. 12: 3366. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules23123366

APA StyleAbdi Bellau, M. L., Bortolini, O., Fantin, G., Fogagnolo, M., Ragno, D., Delso, I., & Merino, P. (2018). Native Quercetin as a Chloride Receptor in an Organic Solvent. Molecules, 23(12), 3366. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules23123366