Abstract

Epigallocatechin-3-O-gallate (EGCG) is the major catechin component of green tea (Cameria sinensis), and is known to possess antiviral activities against a wide range of DNA viruses and RNA viruses. However, few studies have examined chemical modifications of EGCG in terms of enhanced antiviral efficacy. This paper discusses which steps of virus infection EGCG interferes with, citing previous reports. EGCG appears most likely to inhibits the early stage of infections, such as attachment, entry, and membrane fusion, by interfering with viral membrane proteins. According to the relationships between structure and antiviral activity of catechin derivatives, the 3-galloyl and 5′-OH group of catechin derivatives appear critical to antiviral activities. Enhancing the binding affinity of EGCG to virus particles would thus be important to increase virucidal activity. We propose a newly developed EGCG-fatty acid derivative in which the fatty acid on the phenolic hydroxyl group would be expected to increase viral and cellular membrane permeability. EGCG-fatty acid monoesters showed improved antiviral activities against different types of viruses, probably due to their increased affinity for virus and cellular membranes. Our study promotes the application of EGCG-fatty acid derivatives for the prevention and treatment of viral infections.

1. Introduction

2. Classifications, Structures, and Life Cycles of Viruses Discussed in This Review

2.1. Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV)

Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) and type 2 (HSV-2) belong to the Herpesviridae family and are known as common pathogens that cause localized skin infections of the mucosal epithelia of the genitals, oral cavity, pharynx, esophagus and eyes. They have a complex structure, comprising an icosahedral, double-stranded DNA-containing capsid, located within the virion and surrounded by a membrane envelope heterogeneously studded with morphologically distinct spikes formed by 12 different glycoprotein species. Two of these glycoproteins (gB and gC) bind heparan sulfate on a cell (Figure 2A and Figure 3(1)). Next, gD binds to entry receptors such as herpes virus entry mediator (HVEM), nectin-1 and 3-O sulfated heparan sulfate. Once bound to the HVEM, gD changes conformation and interacts with viral glycoproteins H (gH) and L (gL), which form a complex. These interactions may result in a hemifusion state. The interaction of gB with the gH/gL complex triggers membrane fusion and creates an entry pore for the delivery of the viral capsid to nuclear pores. Transcription and replication of the viral genome as well as the assembly of progeny capsids take place within the nucleus. The viral mRNA is synthesized by the host cell RNA-polymerase II with the participation of viral factors in all steps in infection. Viral proteins regulate sequential transcriptional cascades (α, β, and γ genes) and a series of posttranslational modifications. After the initiation of viral DNA replication, levels of expression of late γ genes, especially encoding capsid proteins, increase to provide the assembly of progeny virions. Capsid assembly and viral genome packaging occur in the nucleus followed by nucleocapsid egress from the nucleus via nuclear pore or by budding through the nuclear membrane. With the participation of UL36 and UL37 proteins, the capsid is transported from the nucleus to the cytoplasm, where virion maturation and outer shell formation occur. Release of the virion from the cell by exocytosis accomplishes envelope formation.

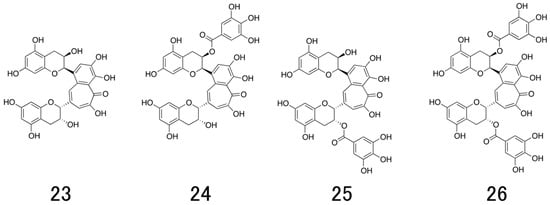

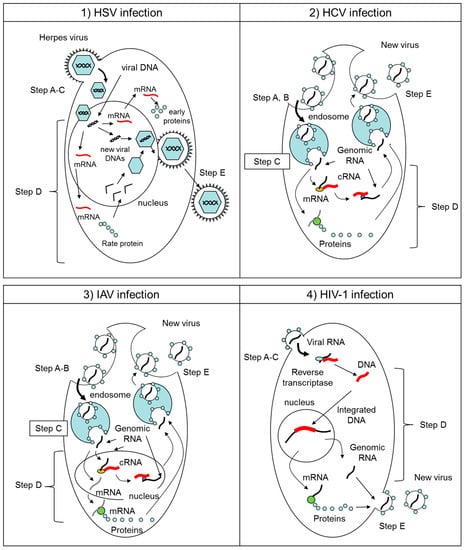

Figure 2.

The DNA and RNA viruses described in this study were classified by Baltimore group. A representative of each virus family and their structures are summarized in the figures. (A) Herpes simplex virus-1 is a member of Herpesviridae, classified to Baltimore group I possessing dsDNA as the genome in a nucleocapsid core enveloped by lipid membrane. (B) Hepatitis C virus and (C) Dengue virus are member of Flaviviridae, classified to Baltimore group IV possessing a (+) single-stranded RNA genome in the viral particle. (D) Influenza A virus is a member of Orthomyxoviridae, classified to Baltimore group V possessing eight (−)-strand viral RNA genomes in the viral particle. (E) Human immunodeficiency virus-1 is a member of Retroviridae, classified to Baltimore VI possessing two (+)-strand RNA genomes in a protein core in the viral particle.

Figure 3.

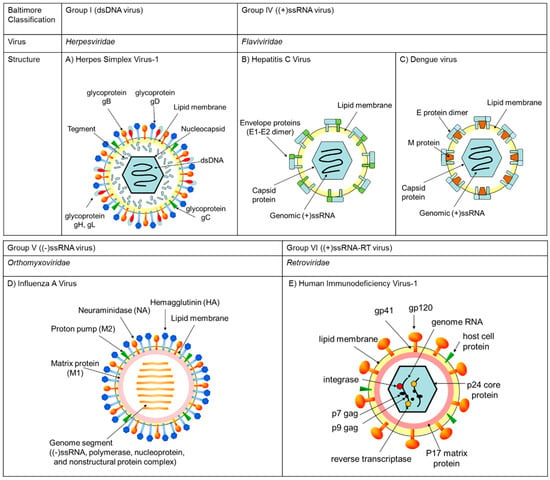

Schematic overviews of the virus life cycles of (1) HSV, (2) HCV, (3) IAV, and (4) HIV-1 in infected cells. Their infection processes were divided by five steps. Step A: virus attaches to cell surface receptor. Step B: virus entry into cells by endocytosis. Step C: virus-cell membrane fusion. Step D: viral genome replication and synthesis of progeny viral components. Step E: budding of newly developed progeny virions.

2.2. Hepatitis C Virus (HCV), Zika Virus (ZIKV), West Nile Virus (WNV), Dengue Virus (DENV), and Chikungunya Virus (CHIKV)

HCV, ZIKV, WNV, and DENV are all part of the Flaviviridae family and are enveloped, with icosahedral and spherical geometries. HCV, of the genus Hepacivirus, is a major cause of liver disease, while ZIKV, WNV, and DENV, of the genus Flavivirus, cause a series of prevalent arthropod-borne viral diseases. While HCV and DENV belong to the same family and thus share many features of their life cycles, their virion organization and properties differ substantially. HCV and DENV are enveloped viruses with at diameter of approximately 40–65 nm and they have a non-segmented, single-stranded, 9.6- to 11-kb, positive-sense RNA genome (Figure 2B,C). The core of the viral particle is composed by the capsid proteins, which are thought to enclose the RNA genome (Figure 2B,C). The HCV glycoproteins (envelope 1 [E1] and envelope 2 [E2], Figure 2B), and the DENV glycoproteins (envelope [E] and matrix [M] proteins, Figure 2C) are embedded in the lipid envelope. In case of HCV infection, E1 serves as the fusogenic subunit and E2 acts as the receptor-binding protein. Entry into host cells occurs through complex interactions between virions and several cell-surface molecules (Figure 3(2)). In case of DENV, E and M proteins form the external surface of the mature virus particle. The binding of E protein to dendritic cell specific receptor triggers the internalization of DENV into the cells. Once inside the cells, the genome is translated to proteins, then proteolytically processed by viral and cellular proteases to produce three structural and nonstructural (NS) proteins. The NS proteins recruit the viral genome into an RNA replication complex and the RNA replication takes places via the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. After the negative-strand RNA is synthesized, it serves as a template to produce new positive-strand viral genomes. Nascent genomes can then be translated, further replicated or packaged within new virus particles and released at the cell surface. CHIKV is from the Togaviridae family and is also enveloped, with icosahedral and spherical geometry. The diameter is 65–70 nm with a non-segmented, single-stranded, 10- to 12-kb, positive-sense RNA genome. The virus consists of four nonstructural proteins and three structural proteins. The structural proteins are the capsid and two envelope glycoproteins: E1 and E2, which form heterodimeric spikes on the virion surface. E2 binds to cellular receptors to enter the host cell through receptor-mediated endocytosis. E1 contains a fusion peptide which, when exposed to the acidity of the endosome in eukaryotic cells, dissociates from E2 and initiates membrane fusion that allows the release of nucleocapsids into the host cytoplasm, promoting infection.

2.3. Influenza A Virus (IAV)

Influenza A virus is part of the Orthomixoviridae family, an enveloped, roughly spherical virus with a diameter of about 50–120 nm and eight distinct negative-sense single-stranded RNA genome segments. Influenza virus has three membrane proteins: hemagglutinin (HA), proton pump (M2), and neuraminidase (NA). The inner membrane of the virion is backed by matrix (M1) protein, and the inside of the virion contains eight different genome segments. Each genome segment is a ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex that consists of a negative-strand RNA genome together with an RNA polymerase complex (PA, PB1, PB), nucleoprotein (NP), and nonstructural proteins (NS) (Figure 2D).

The IAV binds to host cell glycoproteins or glycolipids by HA protein and enters cells through receptor-mediated endocytosis (Figure 3(3)). Under the low pH of the late endosome, HA induces fusion of the viral and endosomal membranes. After the replication and transcription of IAV genomic RNAs takes place in the nucleus by the trimeric viral polymerase complex composed of PB2, PB1, and PA subunits, the viral proteins enter the endoplasmic reticulum. Transport of viral protein to the plasma membrane likely requires host factors. At the plasma membrane, HA and NA associate with lipid rafts that are the site of influenza virus budding. The assembly and virion incorporation of the eight distinct viral ribonucleoproteins requires segment-specific packaging signals in the viral RNAs.

2.4. Human Immunodeficiency Virus-1 (HIV-1)

HIV-1 belongs to the Retroviridae family and is an enveloped, roughly spherical virus with a diameter of about 120 nm and two copies of a positive-sense single-stranded RNA genome. This single-stranded RNA is bound to integrase, reverse transcriptase, and other proteins. The viral envelope contains proteins from the host cell and relatively few copies of the envelope protein, known as glycoprotein (gp)120, and a stem consisting of three gp41 molecules (Figure 2E).

HIV-1 binds to a CD4 receptor and one of two co-receptors on the surface of a CD4+ T-lymphocyte. The virus then fuses with the host cell (Figure 3(4)). After fusion, the virus releases genomic RNA into the host cell. An HIV enzyme called reverse transcriptase converts the single-stranded HIV RNA to double-stranded HIV DNA. The newly formed HIV DNA enters the nucleus of the host cell, where an HIV enzyme called integrase inserts the HIV DNA within the host cell’s own DNA. The integrated HIV DNA is called a provirus. The provirus may remain inactive for several years, producing few or no new copies of HIV. When the host cell receives a signal to become active, the provirus uses a host enzyme called RNA polymerase to create copies of the HIV genomic material, as well as shorter strands of RNA called messenger RNA (mRNA). The mRNA is used as a blueprint to make long chains of HIV proteins. An HIV enzyme called protease cuts the long chains of HIV proteins into smaller individual proteins. As the smaller HIV proteins come together with copies of the RNA genetic material of HIV, a new virus particle is assembled. The newly assembled virus pushes out from the host cell.

Figure 3 provides representative schematic overviews of the viral life cycles of HSV, HCV, IAV, and HIV-1 in infected cells. In the first step of each virus infection, virus attaches to the cell surface with or without binding receptors. This attachment step is described as “Step A” in this study. Among those viruses, HCV and IAV enter the cell by endocytosis. This entry step is described as “Step B” in this study. In case of HCV and IAV, as the pH in the endosome drops, a conformational change in viral membrane proteins is triggered and induces membrane fusion between virus and cells. This membrane fusion step is described as “Step C” in this study. In the cases of HSV and HIV-1, both Steps B and C are integral steps with Step A. After uncoating viral genes from the virion in the cytoplasm or nucleus, the viral genes are replicated and/or transcribed to mRNA to create progeny virions. This replication step is described as “Step D” in the study. In the last step, newly produced virions are secreted from the infected cell by enzymatic cleavage of the virus-cell interaction. This step is described as “Step E” in this study.

7. Lipid Bilayer Affinity of EGCG-Alkyl Ether Derivatives

In 1998, Kouno et al. [49] reported that EGCG (1) inhibited lipid peroxidation in liposome bilayer caused by water soluble radical initiator [2,2′-azobis(2-amidinopropane) dihydrocholoride (AAPH)]. But 1 did not inhibit peroxidation caused by lipophilic radical initiator [2,2′-azobis (2,4-dimethylvaleronitrile) (AMVN)], because it does not penetrate into the hydrophobic region of lipid bilayer. Therefore, they synthesized a series of lipophilic EGCG such as thioether derivatives (6; EGCG-(CH2-S-C8)2 and EGCG-(CH2-S-Bn)2) and a n-octadecylisocyanate derivative (7; EGCG-C18-Carbamoyl). These compounds were evaluated their inhibition activities against lipid peroxidation of egg-phosphatidylcholine (PC) by measuring the concentration of thiobarbitulic acid reactive substrate. As a result, EGCG-(CH2-S-C8)2 and EGCG-C18-Carbamoyl inhibited lipid peroxidation in liposome lipid bilayer caused both by AAPH at 7.9 μM and 24.6 μM and by AMVN at 60.0 μM and 22.1 μM, respectively (Table 1). EGCG-(CH2-S-Bn)2 efficiently inhibited lipid peroxidation by AAPH (IC50 = 9.6 μM), but showed limited inhibitory effect to AMVN (IC50 = 432 μM). These data indicated that EGCG modified with a long alkyl chain obtain increased affinity into the hydrophobic region of the lipid bilayer.

8. EGCG-Fatty Acid Derivatives

8.1. Synthesis of EGCG-Fatty Acid Derivatives

Since EGCG modified with a long alkyl chain possesses lipophilic property [49], we synthesized a series of EGCG fatty acid monoester derivatives 8 by lipase-catalyzed transesterification [50]. EGCG-monoesters modified with saturated fatty acids such as butanoyl, octanoyl, lauroyl, palmitoyl, and stealoyl groups are represented as EGCG-C4, EGCG-C8, EGCG-C12, EGCG-C16, and EGCG-C18, respectively. EGCG-monoesters modified with non-saturated fatty acids such as linoleyl and linoneyl are represented as EGCG-C18DE and EGCG-C18TE.

Although EGCG (1) has been reported to interfere with the catalytic activity of lipases [51], we succeeded in preparing EGCG-fatty acid derivatives by a lipase-catalyzed transesterification in polar organic solvents such as N,N-dimethylformamide or acetonitrile [50]. Interestingly, this lipase-catalyzed method afforded the B-ring modified esters as major products in case the acyl donor is a saturated fatty acid ester such as vinyl stearate (Acyl position, R1:R2:R3:R4 = 38:35:7:20) [50], while it affords the D-ring modified esters as major products in case the acyl donors are non-saturated fatty acid such as vinyl linolate (Acyl position, R1:R2:R3:R4 = 28:22:5:45) and linoleate (Acyl position, R1:R2:R3: R4 = 15:19:4:62) according to 1H-NMR spectroscopy analysis.

8.2. Cytotoxicity and Influenza Virus Inhibitory Effect of EGCG and EGCG-Fatty Acid Derivatives

In 2008, Mori et al. [50] examined cytotoxicity of EGCG (1) and EGCG derivatives (8) to MDCK cells by MTT proliferation and viability assay. As a result, the cytotoxicity of EGCG-fatty acid derivatives (8) was increased in an alkyl-length dependent manner. Interestingly, the lauroyl ester showed the highest among them and the CC50 was 42 μM which was 6.6-fold higher than 1 (CC50 = 275 μM) [50]. This was probable due to the increased cellular membrane affinity of EGCG-C12 with modest water solubility.

In this review, we further provide the effect of non-saturated bonds in EGCG-fatty acid esters on the cytotoxicity by synthesizing EGCG-fatty acid esters that have the same alkyl chain length but have different number of cis-olefin bonds. As a result, EGCG-C18TE possesses three cis-olefin bonds in C18 alkyl chain showed 9.4-fold higher cytotoxicity (CC50 = 32 μM) than EGCG-C18 (CC50 = 300 μM) (Table 6). On the other hand, EGCG-C18DE that has two cis-olefin bonds in C18 alkyl chain showed only 1.2-fold higher cytotoxicity (CC50 = 250 μM) than EGCG-C18 (Table 6). The hydrophobicity of EGCG-C18, EGCG-C18DE, and EGCG-C18TE were estimated as log P value using the ChemBioDraw Ultra ver. 11 software and those log P values were identified as 8.97, 8.33, and 8.01, respectively. Thus, the higher cytotoxicity of EGCG-C18TE could be due to both better water solubility and the higher cellular membrane affinity.

Table 6.

Cytotoxicity and Protective Effect of EGCG and EGCG-Fatty Acid Derivatives against Influenza A/PR/8/34(H1N1) Virus.

Anti-influenza virus activities of 1 and EGCG-fatty acid derivatives (8) were studied using two different experimental methods. In the first experiment, 1 and EGCG fatty acid derivatives were added to a confluent monolayer of MDCK cells, followed by incubation for 2 h at 37 °C. After the solution was removed from each well, cell sheets were washed and infected with influenza A/PR/8/34 (H1N1) virus. After 1 h for virus adsorption at room temperature, the cell sheets were washed and assessed by the plaque formation inhibitory assay. As a result, the EC50 of EGCG-C18DE and EGCG-C18TE were 7.0 μM and 3.0 μM that were much lower than 1 (EC50 = 94 μM) and EGCG-C18 (EC50 = 64 μM) (Table 6). The selectivity index (SI) of EGCG-C18DE was 35.7 that is higher than 1 (SI = 2.91) and EGCG-C18 (SI = 4.68) (Table 6).

In the second experiment, the virus was pre-treated with 1 or EGCG-fatty acid derivatives (8) to assess their virucidal activities. Briefly, each compound was directly mixed with influenza A/PR/8/34(H1N1) virus and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. The mixed solution was then applied to a confluent monolayer of MDCK cells and subsequently assessed by plaque formation inhibitory assay. As a result, EGCG-C18 exhibited higher virucidal activity (EC50 = 60 nM in Table 7) than EGCG-C18DE (EC50 = 180 nM) and EGCG-C18TE (EC50 = 100 nM) and those were less concentration used in Table 6. From the SI values of 1 and EGCG-fatty acid derivatives summarized in Table 6 and Table 7, these compounds directly interact with the virus particle rather than cells and show potent virucidal activity at much lower concentrations. Further, the introduction of fatty acids such as stearoyl, linoleyl, and linolenyl derivatives to EGCG drastically enhance the antiviral activity of 1. The virucidal effect of EGCG-fatty acid derivatives was also confirmed for other seasonal influenza A/H1N1, A/H3N2, B viruses and avian influenza A/H5N2 viruses [52]. From these data, EGCG-fatty acid esters considered to interact with some common regions of virus components such as viral membrane or proteins and interfere the attachment, entry and membrane fusion (Inhibition Step: A–C).

Table 7.

Cytotoxicity and Direct Virucidal Effect of EGCG and EGCG-Fatty Acid Derivatives against Influenza A/PR/8/34(H1N1) Virus.

8.3. Anti-Influenza Virus Activity of EGCG-C16 in Chicken Embryonated Eggs

In 2009, Kaihatsu et al. [52] further assessed the virucidal effect of EGCG-fatty acid derivatives on avian influenza virus in chicken embryonated eggs. As this effect has already been assessed in cell-based assays, they pre-treated with influenza A/Duck/Hong Kong/342/78 (H5N2) to EGCG (1), EGCG-C16 (8), zanamivir, and oseltamivir phosphate at a concentration of 1 μM for 1 h at room temperature. The mixture was then inoculated (50 pfu/egg) into the allantoic fluid of embryonated eggs for 7 days at 37 °C. As a result, EGCG-C16 completely inhibited avian influenza virus infection of chicken embryos, while commercially available drugs did not show complete blockage [53,54]. These results indicate that EGCG-C16 induces irreversible and virucidal denaturing of influenza viruses.

8.4. Antiviral Activity of EGCG-Fatty Acid Derivatives for Other Viruses

In 2012, Zhong et al. [55] prepared lipophilic ester derivatives of EGCG, namely EGCG-O-tetrastearate, EGCG-O-tetraeicosapentaenoate, EGCG-O-tetradocosahexaenoate, and EGCG-O-octabutylate (9). The EGCG-polyunsaturated fatty acids showed approximately 1700-fold and 22-fold higher anti-hepatitis C virus protease inhibitory activities than the positive control embelin and EGCG-O-tertrastearate in vitro. (Inhibition step; D, but only tested against protease)

In 2013, Oliveira et al. [56] reported that palmitoyl-EGCG (8, EGCG-C16) blocks viral glycoprotein(s) and efficiently inhibit the binding of HSV-1 to host receptors. (Inhibition step: A)

In 2014, Zhao et al. [26] evaluated the antiviral activity of EGCG-O-monopalmitate (8, EGCG-C16) against Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus (PRRSV). EGCG-C16 showed 177-fold higher the virus inhibitory effects compared to EGCG when they were added to a monolayer of MARC-145 cells prior to the virus inoculation at 10 TCID50 (50% tissue culture infectious dose). They infer that EGCG-C16 may inhibit viral adsorption and cell intrusion. The EC50 value of EGCG-C16 for PRRSV is nearly the same level as Ribavirin, a guanosine analog used to inhibit viral RNA synthesis, but the selectivity is 3.8-fold higher than them. (Inhibition step: A). From these reports, EGCG-fatty acid esters efficiently interact with the viral membrane or the cellular membrane and prevent viral attachment and entry steps.

9. Conclusions

From this study, EGCG was found to be the most potent and universal virus inhibitor among the natural catechins, directly interacting not only with various types of enveloped DNA, (+)-RNA, and (−)-RNA viruses, but also various types of cells. The 3-galloyl and 5′-OH groups appear crucial for virus inhibition activity. EGCG mainly inhibits the early stages of infections, such as attachment, entry, and membrane fusion, by interfering with either viral membrane proteins or cellular protein or both of them. We thus developed EGCG-fatty acid derivatives to improve the viral and cellular membrane permeability of EGCG and investigated their antiviral activities. As a result, EGCG-fatty acid monoesters with a long fatty acid showed improved antiviral activities against broad spectrum of influenza virus, HSV, and PRRV, with higher potency than EGCG. This methodology may facilitate the application of EGCG-fatty acid derivatives to the prevention and treatment of viral infections.

Author Contributions

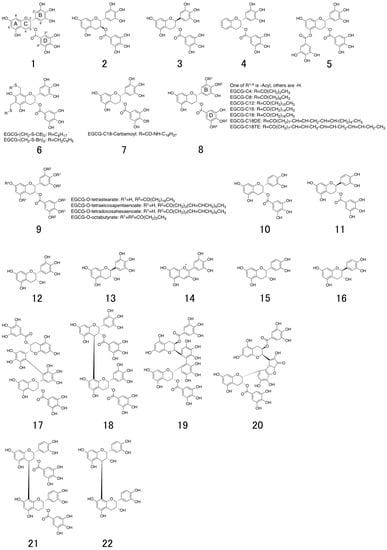

K.K.: Section 1, Section 2, Section 6, Section 7 and Section 8, Figure 2 and Figure 3, Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7, Abstract, and Conclusions, M.Y.: Literature search, Section 3, Section 4 and Section 5, Figure 1 and Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5. Y.E.: Literature search, Review design, Outline and Reference confirmation.

Funding

This work was funded by a Grand for Industrial Technology Research (P00041 to Kunihiro Kaihatsu), from New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization (NEDO).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| AAPH | 2,2′-azobis(2-amidinopropane) dihydrocholoride |

| AMVN | 2,2′-azobis (2,4-dimethylvaleronitrile) |

| bEGCdG | 2′,2′-bisepigallocatechin digallate |

| BVDV | bovine viral diarrhea virus |

| C | (−)-catechin |

| CC50 | 50% cytotoxic concentration |

| CG | (−) catechin-3-O-gallate |

| CHIKV | chikungunya virus |

| DENV | dengue virus |

| DO-EGCG | 5,7-dideoxy-EGCG |

| E | envelope protein |

| EBOV | Ebola virus |

| EC | (−) epicatechin |

| EC50 | 50% effective concentration |

| ECG | (−) epicatechin-3-O-gallate |

| EGC | (−)-epigallocatechin |

| EGCDG | epigallocatechin 3,5-digallate |

| EGCG | (−)-epigallocatechin-3-O-gallate |

| ELISA | enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| EM | electron microscopy |

| GC | (−)-gallocatechin |

| GCG | gallocatechin-3-O-gallate |

| HA | hemagglutinin |

| HBV | hepatitis B virus |

| HCV | hepatitis C virus |

| HCVcc | cell-culture-derived HCV |

| HPV | human papilloma virus |

| HSV | herpes simplex virus |

| HVEM | herpes virus entry mediator |

| IAV | influenza A virus |

| IC50 | 50% inhibitory concentration |

| JEV | Japanese encephalitis |

| M | matrix protein |

| MALDI | matrix assisted laser desorption/ionization |

| MDCK | Madin-Darby canine kidney |

| MUNANA | 2′-(4-methylumbelliferyl)-α-d-N-acetylneuraminic acid |

| NA | neuraminidase |

| NS | nonstructural protein |

| NMR | nuclear magnetic resonance |

| PA | polymerase subunit A |

| PB1 | polymerase subunit B1 |

| PB2 | polymerase subunit B2 |

| PRRSV | porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus |

| RNP | ribonucleoprotein |

| RT | reverse transcription |

| SINV | sindbis virus |

| SEVI | semen-derived enhancer of virus infection |

| TCID50 | 50% tissue culture infectious dose |

| TF | theaflavin |

| TFDG | theaflavin-3,3′-O-digallate |

| TF-3-G | theaflavin-3-gallate |

| TF-3′-G | theaflavin-3′-gallate |

| WNV | West Nile viruses |

| YFV | yellow fever virus |

| ZIKV | zika virus |

References

- Wang, Y.; Ho, C.-T. Polyphenolic Chemistry of Tea and Coffee: A Century of Progress. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 8109–8114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakayama, M.; Suzuki, K.; Toda, M.; Okubo, S.; Hara, Y.; Shimamura, T. Inhibition of the infectivity of influenza virus by tea polyphenols. Antivir. Res. 1993, 21, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taguri, T.; Tanaka, T.; Kouno, I. Antibacterial spectrum of plant polyphenols and extracts depending upon hydroxyphenyl structure. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2006, 29, 2226–2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, D.; Daniel, K.G.; Kuhn, D.J.; Kazi, A.; Bhuiyan, M.; Li, L.; Wang, Z.; Wan, S.B.; Lam, W.H.; Chan, T.H.; et al. Green tea and tea polyphenols in cancer prevention. Front. Biosci. 2004, 9, 2618–2631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyu, S.-Y.; Rhim, J.-Y.; Park, W.-B. Antiherpetic Activities of Flavonoids against Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 (HSV-1) and Type 2 (HSV-2) In Vitro. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2005, 28, 1293–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savi, L.A.; Barardi, C.R.A.; Simoes, C.M.O. Evaluation of Antiherpetic Activity and Genotoxic Effects of Tea Catechin Derivatives. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 2552–2557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isaacs, C.E.; Wen, G.Y.; Xu, W.; Jia, J.H.; Rohan, L.; Corbo, C.; Di Maggio, V.; Jenkins, E.C., Jr.; Hillier, S. Epigallocatechin Gallate Inactivates Clinical Isolates of Herpes Simplex Virus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008, 52, 962–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gescher, K.; Hensel, A.; Hafezi, W.; Derksen, A.; Kuhn, J. Oligomeric proanthocyanidins from Rumex acetosa L. inhibit the attachment of herpes simplex virus type-1. Antivir. Res. 2011, 89, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isaacs, C.E.; Xu, W.; Merz, G.; Hillier, S.; Rohan, L.; Wen, G.Y. Digallate Dimers of (−)-Epigallocatechin Gallate Inactivate Herpes Simplex Virus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011, 55, 5646–5653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colpitts, C.C.; Schang, L.M. A Small Molecule Inhibits Virion Attachment to Heparan Sulfate- or Sialic Acid-Containing Glycans. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 7806–7817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pradhan, P.; Nguyen, M.L. Herpes simplex virus virucidal activity of MST-312 and epigallocatechin gallate. Virus Res. 2018, 249, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, J.M.; Ruzindana-Umunyana, A.; Imbeault, L.; Sircar, S. Inhibition of adenovirus infection and adenain by green tea catechins. Antivir. Res. 2003, 58, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Zhang, E.; Shi, J.; Li, X.; Zhou, K.; Zhang, Q.; Le, A.D.; Tang, X. (−)-Epigallocatechin-3-gallate inhibits human papillomavirus (HPV)-16 oncoprotein-induced angiogenesis in non-small cell lung cancer cells by targeting HIF-1a. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2013, 71, 713–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, W.; Li, L.-X.; Liao, Q.-J.; Liu, C.-L.; Chen, X.-L. Epigallocatechin gallate inhibits HBV DNA synthesis in a viral replication-inducible cell line. World J. Gastroenterol. 2011, 17, 1507–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuo, G.; Li, Z.; Chen, L.; Xu, X. Activity of compounds from Chinese herbal medicine Rhodiola kirilowii (Regel) Maxim against HCV NS3 serine protease. Antivir. Res. 2007, 76, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciesek, S.; von Hahn, T.; Colpitts, C.C.; Schang, L.M.; Friesland, M.; Steinmann, J.; Manns, M.P.; Ott, M.; Wedemeyer, H.; Meuleman, P.; et al. The Green Tea Polyphenol, Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate, Inhibits Hepatitis C Virus Entry. Hepatology 2011, 54, 1947–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calland, N.; Albecka, A.; Belouzard, S.; Wychowski, C.; Duverlie, G.; Descamps, V.; Hober, D.; Dubuisson, J.; Rouillé, Y.; Séron, K. (−)-Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate Is a New Inhibitor of Hepatitis C Virus Entry. Hepatology 2012, 55, 720–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhat, R.; Adam, A.T.; Lee, J.J.; Deloison, G.; Rouillé, Y.; Séron, K.; Rotella, D.P. Structure-activity studies of (−)-epigallocatechin gallate derivatives as HCV entry inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2014, 24, 4162–4165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calland, N.; Sahuc, M.E.; Belouzard, S.; Pène, V.; Bonnafous, P.; Mesalam, A.A.; Deloison, G.; Descamps, V.; Sahpaz, S.; Wychowski, C.; et al. Polyphenols Inhibit Hepatitis C Virus Entry by a New Mechanism of Action. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 10053–10063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carneiro, B.M.; Batista, M.N.; Braga, A.C.S.; Nogueira, M.L.; Rahal, P. The green tea molecule EGCG inhibits Zika virus entry. Virology 2016, 496, 215–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, D.; Pathan, J.K.; Malviya, S.; Kharia, A. The recent allopathic and herbal approaches for Zika Virus. Int. J. Pharm. Life Sci. 2016, 7, 5271–5280. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, N.; Murali, A.; Singh, S.K.; Giri, R. Epigallocatechin gallate, an active green tea compound inhibits the Zika virus entry into host cells via binding the envelope protein. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 104, 1046–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vázquez-Calvo, Á.; Jiménez de Oya, N.; Martín-Acebes, M.A.; Garcia-Moruno, E.; Saiz, J.C. Antiviral Properties of the Natural Polyphenols Delphinidin and Epigallocatechin Gallate against the Flaviviruses West Nile Virus, Zika Virus, and Dengue Virus. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raekiansyah, M.; Buerano, C.C.; Luz, M.A.D.; Morita, K. Inhibitory effect of the green tea molecule EGCG against dengue virus infection. Arch. Virol. 2018, 163, 1649–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.-W.; Hsieh, P.-S.; Lin, C.-C.; Hu, M.-K.; Huang, S.-M.; Wang, Y.-M.; Liang, C.-Y.; Gong, Z.; Ho, Y.-J. Synergistic effects of combination treatment using EGCG and suramin against the chikungunya virus. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017, 491, 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, C.; Liu, S.; Li, C.; Yang, L.; Zu, Y. In Vitro Evaluation of the Antiviral Activity of the Synthetic Epigallocatechin Gallate Analog-Epigallocatechin Gallate (EGCG) Palmitate against Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus. Viruses 2014, 6, 938–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, C.W.; Hsu, F.L.; Lin, J.Y. Inhibitory Effects of Polyphenolic Catechins from Chinese Green Tea on HIV Reverse Transcriptase Activity. J. Biomed. Sci. 1994, 1, 163–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tillekeratne, L.M.V.; Sherette, A.; Grossman, P.; Hupe, L.; Hupe, D.; Hudson, R.A. Simplified Catechin-Gallate Inhibitors of HIV-1 Reverse Transcriptase. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2001, 11, 2763–2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, K.; Tsuno, N.H.; Kitayama, J.; Okaji, Y.; Yazawa, K.; Asakage, M.; Hori, N.; Watanabe, T.; Takahashi, K.; Nagawa, H. Epigallocatechin gallate, the main component of tea polyphenol, binds to CD4 and interferes with gp120 binding. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2003, 112, 951–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Lu, H.; Zhao, Q.; He, Y.; Niu, J.; Debnath, A.K.; Wu, S.; Jiang, S. Theaflavin derivatives in black tea and catechin derivatives in green tea inhibit HIV-1 entry by targeting gp41. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2005, 1723, 270–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williamson, M.P.; McCormick, T.G.; Nance, C.L.; Shearer, W.T. Epigallocatechin gallate, the main polyphenol in green tea, binds to the T-cell receptor, CD4: Potential for HIV-1 therapy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2006, 118, 1369–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nance, C.L.; Siwak, E.B.; Shearer, W.T. Preclinical development of the green tea catechin, epigallocatechin gallate, as an HIV-1 therapy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2009, 123, 459–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, F.; Chen, W.; Yi, K.; Wu, Z.; Si, Y.; Han, W.; Zhao, Y. The evaluation of catechins that contain a galloyl moiety as potential HIV-1 integrase inhibitors. Clin. Immunol. 2010, 137, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Hattori, T.; Kodama, E.N. Epigallocatechin gallate inhibits the HIV reverse transcription step. Antivir. Chem. Chemother. 2011, 21, 239–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartjen, P.; Frerk, S.; Hauber, I.; Matzat, V.; Thomssen, A.; Holstermann, B.; Hohenberg, H.; Schulze, W.; Schulze zur Wiesch, J.; van Lunzen, J. Assessment of the range of the HIV-1 infectivity enhancing effect of individual human semen specimen and the range of inhibition by EGCG. AIDS Res. Ther. 2012, 9, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellano, L.M.; Hammond, R.M.; Holmes, V.M.; Weissman, D.; Shorter, J. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate rapidly remodels PAP85-120, SEM1(45-107), and SEM2(49-107) seminal amyloid fibrils. Biol. Open. 2015, 4, 1206–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reid, S.P.; Shurtleff, A.C.; Costantino, J.A.; Tritsch, S.R.; Retterer, C.; Spurgers, K.B.; Bavari, S. HSPA5 is an essential host factor for Ebola virus infection. Antivir. Res. 2014, 109, 171–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, R.H. Inhibition of multiplication of influenza virus by extracts of tea. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1949, 71, 84–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imanishi, N.; Tuji, Y.; Katada, Y.; Maruhashi, M.; Konosu, S.; Mantani, N.; Terasawa, K.; Ochiai, H. Additional Inhibitory Effect of Tea Extract on the Growth of Influenza A and B Viruses in MDCK Cells. Microbiol. Immunol. 2002, 46, 491–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, J.-M.; Lee, K.-H.; Seong, B.-L. Antiviral effect of catechins in green tea on influenza virus. Antivir. Res. 2005, 68, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furuta, T.; Hirooka, Y.; Abe, A.; Sugata, Y.; Ueda, M.; Murakami, K.; Suzuki, T.; Tanaka, K.; Kan, T. Concise synthesis of dideoxy-epigallocatechin gallate (DO-EGCG) and evaluation of its anti-influenza virus activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007, 17, 3095–3098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuzuhara, T.; Iwai, Y.; Takahashi, H.; Hatakeyama, D.; Echigo, N. Green tea catechins inhibit the endonuclease activity of influenza A virus RNA polymerase. PLoS Curr. 2009, 1, RRN1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zu, M.; Yang, F.; Zhou, W.; Liu, A.; Du, G.; Zheng, L. In vitro anti-influenza virus and anti-inflammatory activities of theaflavin derivatives. Antivir. Res. 2012, 94, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ling, J.-X.; Wei, F.; Li, N.; Li, J.-L.; Chen, L.-J.; Liu, Y.-Y.; Luo, F.; Xiong, H.-R.; Hou, W.; Yang, Z.-Q. Amelioration of influenza virus-induced reactive oxygen species formation by epigallocatechin gallate derived from green tea. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2012, 33, 1533–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowalinski, E.; Zubieta, C.; Wolkerstorfer, A.; Szolar, O.H.J.; Ruigrok, R.W.H.; Cusack, S. Structural Analysis of Specific Metal Chelating Inhibitor Binding to the Endonuclease Domain of Influenza pH1N1 (2009) Polymerase. PLoS Pathog. 2012, 8, e1002831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.; Kim, S.-Y.; Lee, H.W.; Shin, J.S.; Kim, P.; Jung, Y.-S.; Jeong, H.-S.; Hyun, J.-K.; Lee, C.-K. Inhibition of influenza virus internalization by (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate. Antivir. Res. 2013, 100, 460–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, P.; Downard, K.M. Catechin inhibition of influenza neuraminidase and its molecular basis with mass spectrometry. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2015, 111, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quosdorf, S.; Schuetz, A.; Kolodziej, H. Different Inhibitory Potencies of Oseltamivir Carboxylate, Zanamivir, and Several Tannins on Bacterial and Viral Neuraminidases as Assessed in a Cell-Free Fluorescence-Based Enzyme Inhibition Assay. Molecules 2017, 22, 1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, T.; Kusano, R.; Kouno, I. Synthesis and antioxidant activity of novel amphipathic derivatives of tea polyphenol. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1998, 8, 1801–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, S.; Miyake, S.; Kobe, T.; Nakaya, T.; Fuller, S.D.; Kato, N.; Kaihatsu, K. Enhanced anti-influenza A virus activity of (−)-epigallocatechin-3-O-gallate fatty acid monoester derivatives: Effect of alkyl chain length. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008, 18, 4249–4252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.L.; He, W.Y.; Yao, L.; Zhang, H.P.; Liu, Z.G.; Wang, W.P.; Ye, Y.; Cao, J.J. Characterization of Binding Interactions of (−)-Epigallocatechin-3-gallate from Green Tea and Lipase. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 8829–8835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaihatsu, K.; Mori, S.; Matsumura, H.; Daidoji, T.; Kawakami, C.; Kurata, H.; Nakaya, T.; Kato, N. Broad and potent anti-influenza virus spectrum of epigallocatechin-3-O-gallate-monopalmitate. J. Mol. Genet. Med. 2009, 3, 195–197. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Daidoji, T.; Kaihatsu, K.; Nakaya, T. The Role of Apoptosis in Influenza Virus Pathogenesis and the Mechanisms Involved in Anti-Influenza Therapies. Curr. Chem. Biol. 2010, 4, 208–218. [Google Scholar]

- Kaihatsu, K.; Barnard, D.L. Recent Developments in Anti-influenza A Virus Drugs and Use in Combination Therapies. Mini Rev. Org. Chem. 2012, 9, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Ma, C.-M.; Shahidi, F. Antioxidant and antiviral activities of lipophilic epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) derivatives. J. Funct. Foods 2012, 4, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, A.; Adams, S.D.; Lee, L.H.; Murray, S.R.; Hsu, S.D.; Hammond, J.R.; Dickinson, D.; Chen, P.; Chu, T.-C. Inhibition of herpes simplex virus type 1 with the modified green tea polyphenol palmitoyl-epigallocatechin gallate. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013, 52, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).