Soft-Template Synthesis of Mesoporous Anatase TiO2 Nanospheres and Its Enhanced Photoactivity

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

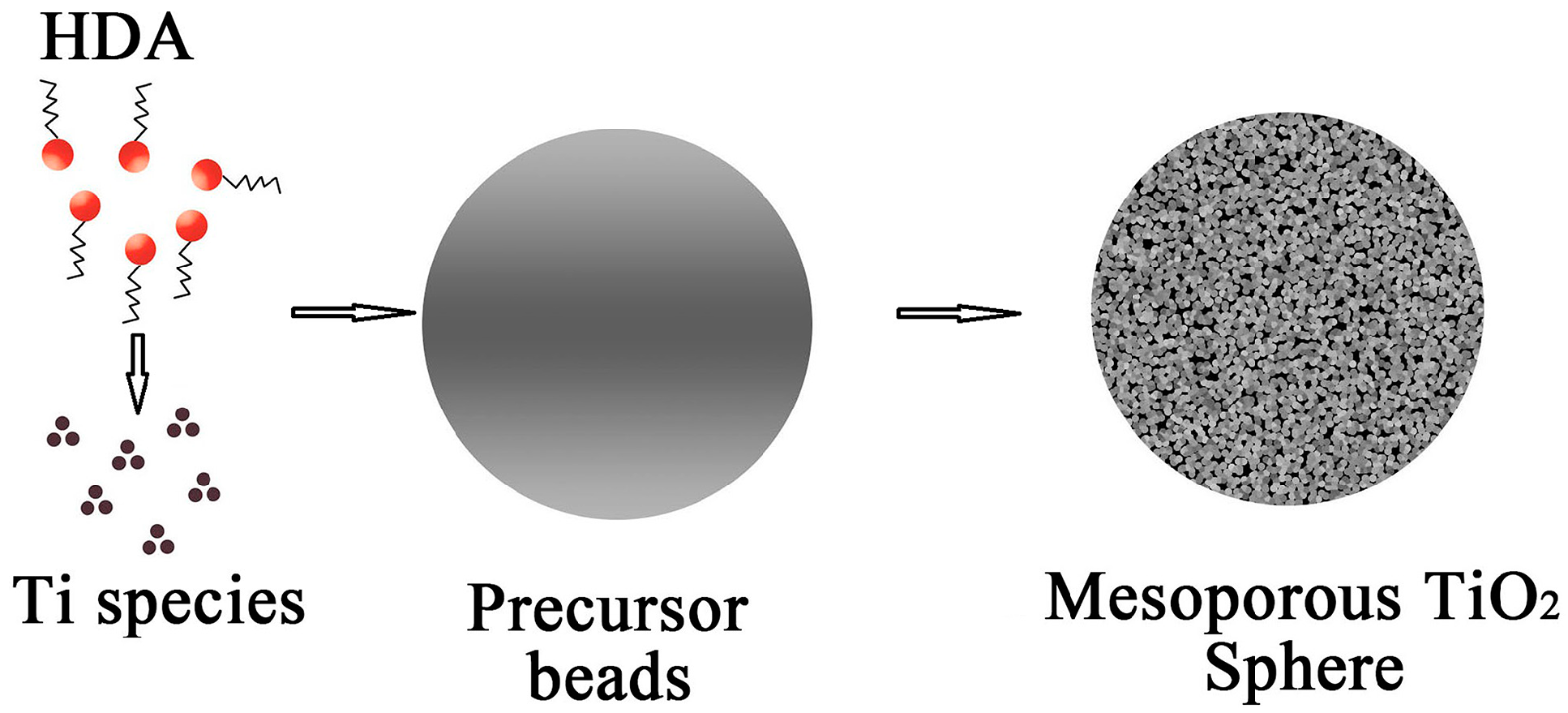

2.1. Formation Mechanism of the Mesoporous Spherical TiO2

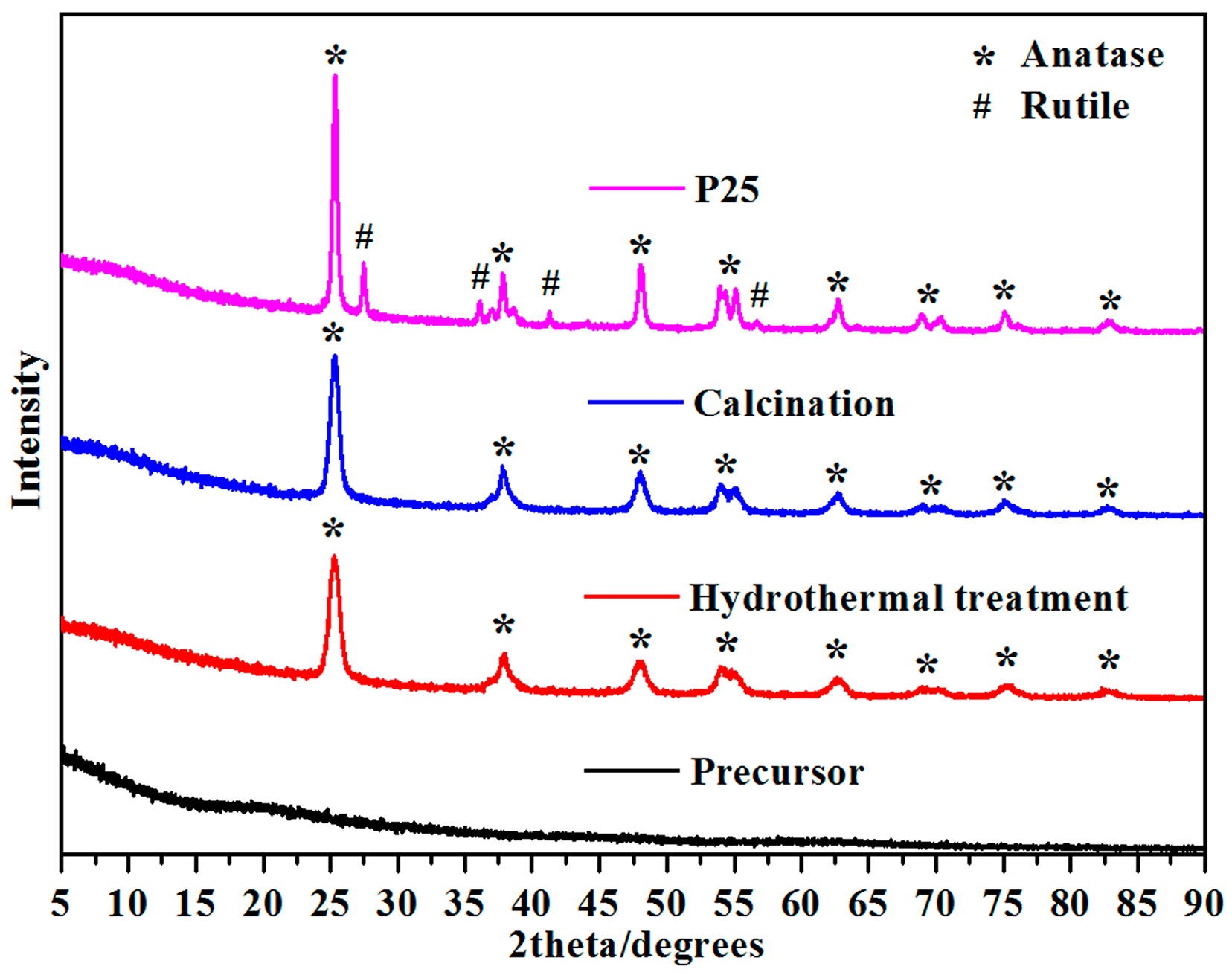

2.2. XRD of Mesoporous Spherical TiO2 and P25 TiO2

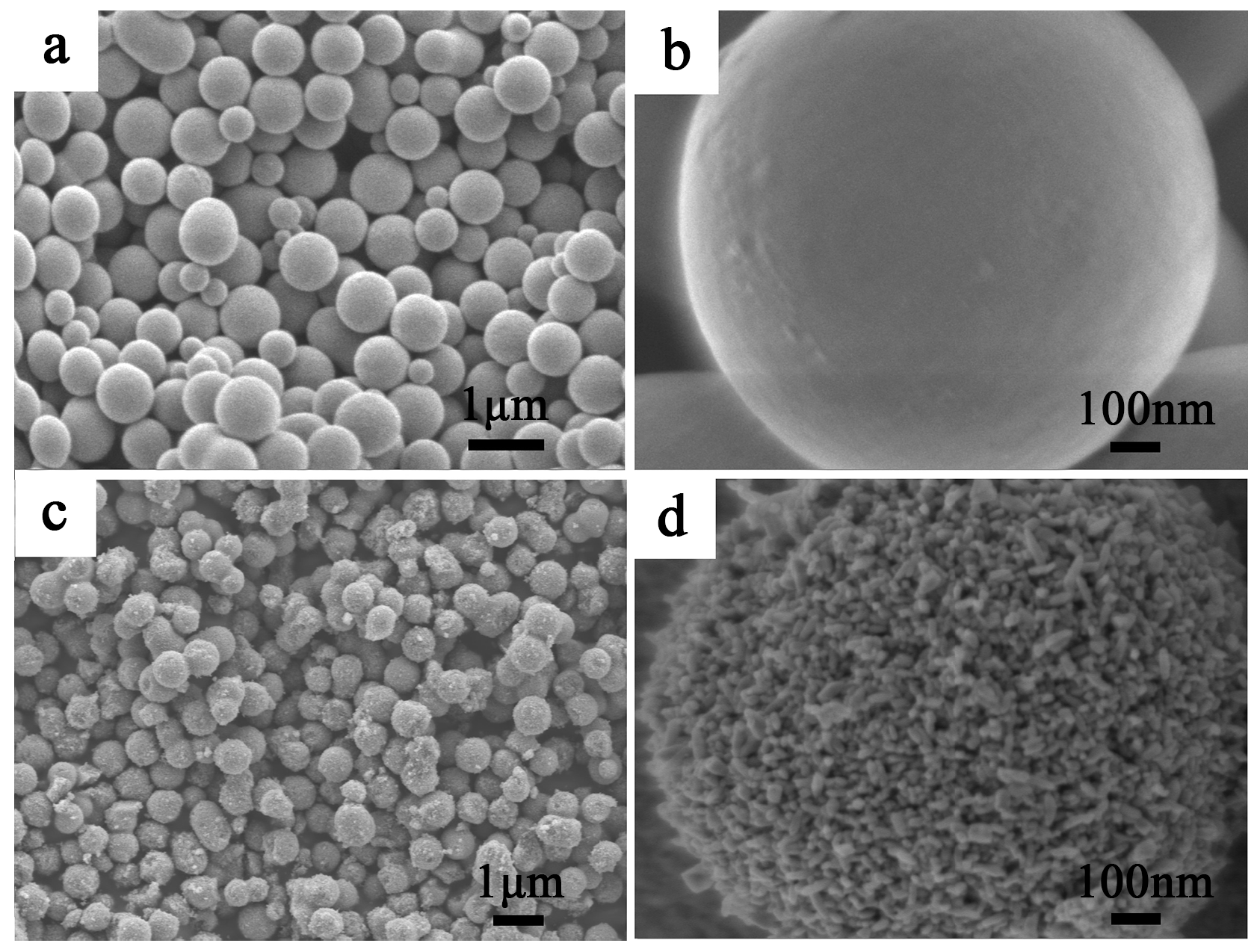

2.3. SEM of Mesoporous Spherical TiO2 and P25 TiO2

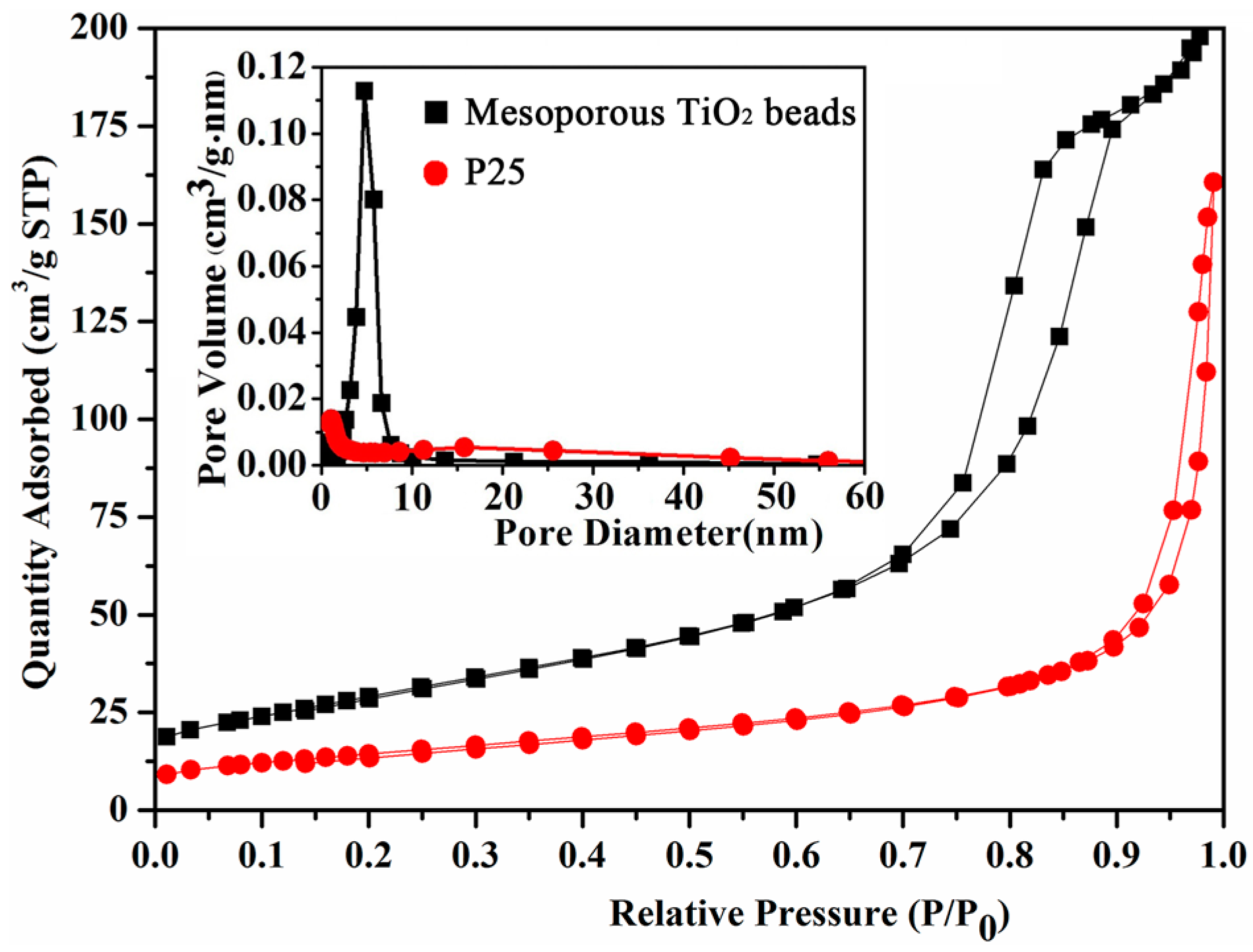

2.4. BET of Mesoporous Spherical TiO2 and P25 TiO2

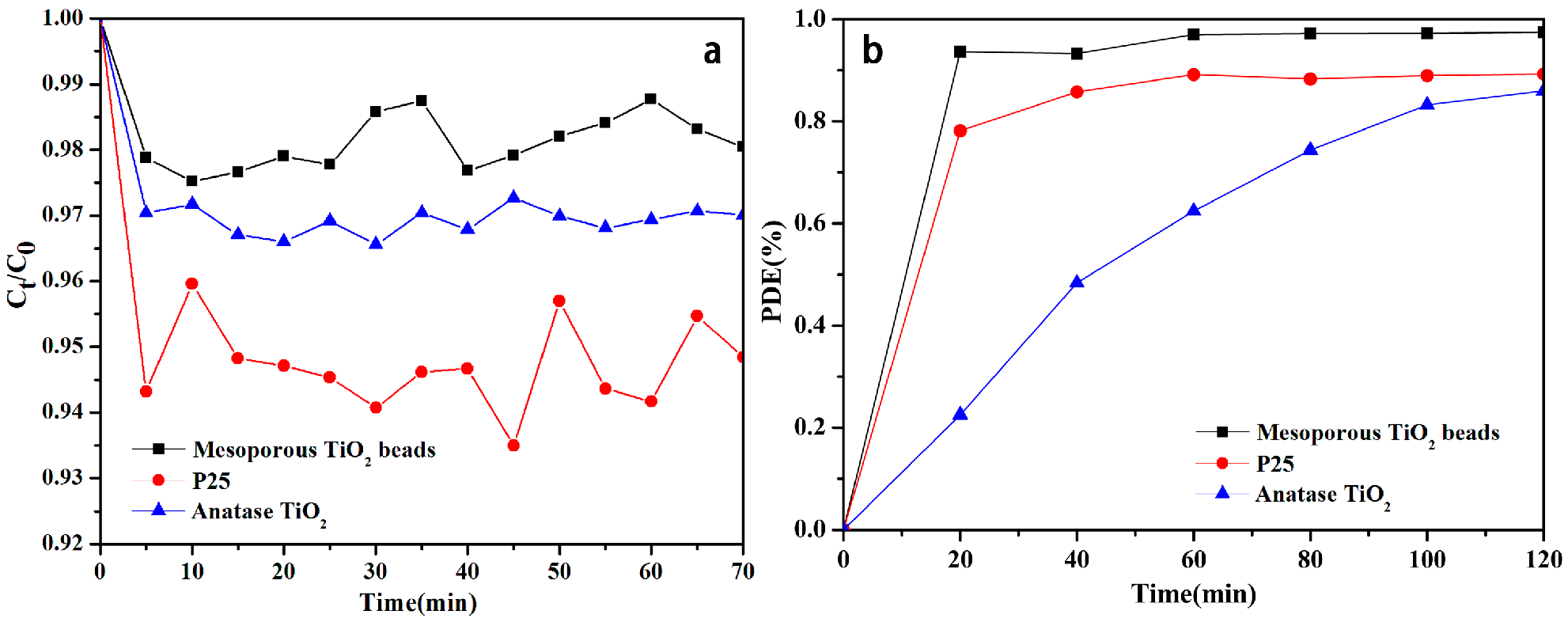

2.5. Adsorption Activities

2.6. Photocatalytic Activities

2.7. The Kinds of Generated ROS under UV-Light Irradiation

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Chemicals and Materials

3.2. Preparation of Mesoporous Spherical TiO2

3.3. Characterization of TiO2

3.4. Adsorption and Photocatalytic Characterization

3.5. Evaluation of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS)

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Leshuk, T.; Parviz, R.; Everett, P.; Krishnakumar, H.; Varin, R.A.; Gu, F. Photocatalytic activity of hydrogenated TiO2. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2013, 5, 1892–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.C.; Jimmy, C.Y.; Ho, C.; Hou, Y.D.; Fu, X.Z. Photocatalytic Activity of a Hierarchically Macro/Mesoporous Titania. Langmuir 2005, 21, 2552–2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shibata, H.; Ogura, T.; Mukai, T.; Ohkubo, T.; Sakai, H.; Abe, M. Direct Synthesis of Mesoporous Titania Particles Having a Crystalline Wall. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 16396–16397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimny, K.; Roquescarmes, T.; Carteret, C.; Stébé, M.J.; Blin, J.L. Synthesis and Photoactivity of Ordered Mesoporous Titania with a Semicrystalline Framework. J. Phys. Chem. C 2012, 116, 6585–6594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, W.S.; Lee, S.W.; Kim, Y.R. Templating Route to Mesoporous Nanocrystalline Titania Nanofibers. Chem. Mater. 2005, 17, 3072–3074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Kang, E.; Son, S.U.; Park, H.M.; Lee, M.K.; Kim, J.; Kim, K.W. Monodisperse nanoparticles of Ni and NiO: Synthesis, characterization, self-assembled superlattices, and catalytic applications in the Suzuki coupling reaction. Adv. Mater. 2005, 17, 429–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.Y.; Ergang, N.S.; Al-Daous, M.A.; Stein, A. Synthesis and characterization of three-dimensionally ordered macroporous carbon/titania nanoparticle composites. Chem. Mater. 2005, 17, 6805–6813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, M.N.; Jin, B.; Chow, C.W.K.; Saint, C. Recent developments in photocatalytic water treatment technology: A review. Water Res. 2010, 44, 2997–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.Q.; Xu, W.C.; Zhu, S.L.; Cui, Z.D.; Yang, X.J.; Inoue, A. Anatase TiO2 hierarchical nanospheres with enhanced photocatalytic activity for degrading methyl orange. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2016, 170, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Kemp, K.C.; Chandra, V. Homogeneous anchoring of TiO2 nanoparticles on graphene sheets for waste water treatment. Mater. Lett. 2012, 81, 127–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaker, H.; Chérif-Aouali, L.; Khaoulani, S.; Fourmentin, S. Photocatalytic degradation of methyl orange and real wastewater by silver doped mesoporous TiO2 catalysts. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A 2016, 318, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, C.H.; Jing, L.Q.; Guo, T.; Cui, H.C.; Zhou, J.; Fu, H.G. Mesoporous SiO2-modified nanocrystalline TiO2 with high anatase thermal stability and large surface area as efficient photocatalyst. J. Phys. Chem. C 2009, 113, 1006–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.; Naikoo, G.A.; Sheikh, M.U.D.; Bano, M.; Khan, F. Effective photocatalytic degradation of congo red dye using alginate/carboxymethyl cellulose/TiO2 nanocomposite hydrogel under direct sunlight irradiation. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A 2016, 327, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logar, M.; Bračko, I.; Potočnik, A.; Jančar, B. Cu and CuO/Titanate nanobelt based network assemblies for enhanced visible light photocatalysis. Langmuir 2014, 30, 4852–4862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Xu, Q.; Feng, Z.C.; Li, M.J.; Li, C. Importance of the relationship between surface phases and photocatalytic activity of TiO2. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 1766–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clifton, J., II; Leikin, J.B. Methylene blue. Am. J. Ther. 2003, 10, 289–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Guo, Y.W.; Liu, B.; Jin, X.D.; Liu, L.J.; Xu, R.; Kong, Y.M.; Wang, B.X. Detection and analysis of reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated by nano-sized TiO2 powder under ultrasonic irradiation and application in sonocatalytic degradation of organic dyes. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2011, 18, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Y.; Chen, G.; Li, D.; Luo, Y.; Lock, N.; Jensen, A.P.; Mamakhel, A.; Mi, J.; Iversen, S.B.; Meng, Q. Highly Selective Deethylation of Rhodamine B on Prepared in Supercritical Fluids. Int. J. Photoenergy 2012, 1, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monnier, A.; Schuth, F.; Huo, Q.; Kumar, D.; Margolese, D.; Maxwell, R.S.; Stucky, G.D.; Krishnamurty, M.; Petroff, P.; Firouzi, A.; et al. Cooperative Formation of inorganic-organic interfaces in the synthesis of silicate mesostructures. Science 1993, 261, 1299–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanev, P.T.; Chibwe, M.; Pinnavaia, T.J. Titanium-containing mesoporous molecular sieves for catalytic oxidation of aromatic compounds. Nature 1994, 368, 321–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.D.; Mitchell, D.R.; Prince, K.; Atanacio, A.J.; Caruso, R.A. Gold nanoparticle incorporation into porous titania networks using an agarose gel templating technique for photocatalytic applications. Chem. Mater. 2008, 20, 3917–3926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.X.; Jiang, Z.L.; Tay, Q.L.; Deng, J.; Lai, Y.K.; Gong, D.G.; Dong, Z.L.; Chen, Z. Visible-light plasmonic photocatalyst anchored on titanate nanotubes: A novel nanohybrid with synergistic effects of adsorption and degradation. RSC Adv. 2012, 2, 9406–9414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.F.; Zheng, B.J.; Kuang, Q.; Wang, X.; Xie, Z.X.; Zheng, L.S. Synthesis of layered protonated titanate hierarchical microspheres with extremely large surface area for selective adsorption of organic dyes. CrystEngComm 2012, 14, 7715–77120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, N.M.; Madras, G.; Kottam, N.; Thomas, T. Multivalent Cu-doped ZnO nanoparticles with full solar spectrum absorbance and enhanced photoactivity. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2014, 53, 5895–5904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.Y.; Long, L.L.; Li, W.W.; Wang, W.K.; Yu, H.Q. Hexagonal microrods of anatase tetragonal TiO2: Self-directed growth and superior photocatalytic performance. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 6075–6077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renke, D.; Richard, S.; David, F.; Han, M.J.; Choong, S.K.; Pill-Soon, S. Characterization of silkworm chlorophyll metabolites as an active photosensitizer for photodynamic therapy. J. Nat. Prod. 1992, 55, 124–151. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Nosaka, Y. Mechanism of the OH radical generation in photocatalysis with TiO2 of different crystalline types. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118, 10824–10832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, A.; Nag, M.P.; Ravishankar, N.; Thomas, T.; Jain, M.; Raghavan, S. Synergistic effect of Mo + Cu codoping on the photocatalytic behavior of metastable TiO2 solid solutions. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118, 29788–29795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Sample Availability: Samples are not available from the authors. |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, X.; Zou, M.; Wang, Y. Soft-Template Synthesis of Mesoporous Anatase TiO2 Nanospheres and Its Enhanced Photoactivity. Molecules 2017, 22, 1943. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules22111943

Li X, Zou M, Wang Y. Soft-Template Synthesis of Mesoporous Anatase TiO2 Nanospheres and Its Enhanced Photoactivity. Molecules. 2017; 22(11):1943. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules22111943

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Xiaojia, Mingming Zou, and Yang Wang. 2017. "Soft-Template Synthesis of Mesoporous Anatase TiO2 Nanospheres and Its Enhanced Photoactivity" Molecules 22, no. 11: 1943. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules22111943

APA StyleLi, X., Zou, M., & Wang, Y. (2017). Soft-Template Synthesis of Mesoporous Anatase TiO2 Nanospheres and Its Enhanced Photoactivity. Molecules, 22(11), 1943. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules22111943