Systematic Review of Informal Urban Economies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy and Identification of Studies

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Classification of Journal Articles

2.4. Limitations of the Systematic Review

3. Results

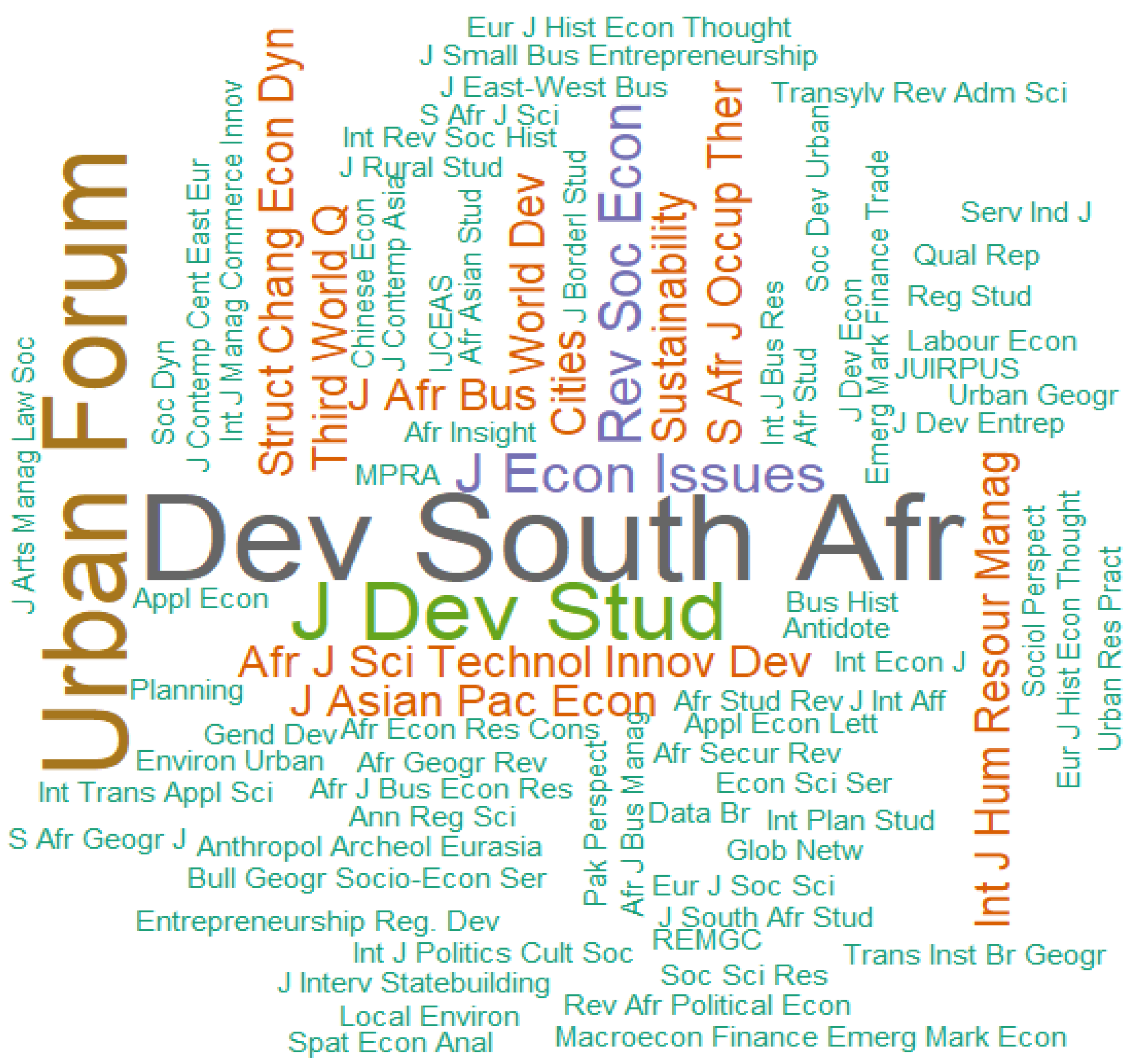

3.1. General Characteristics of Studies

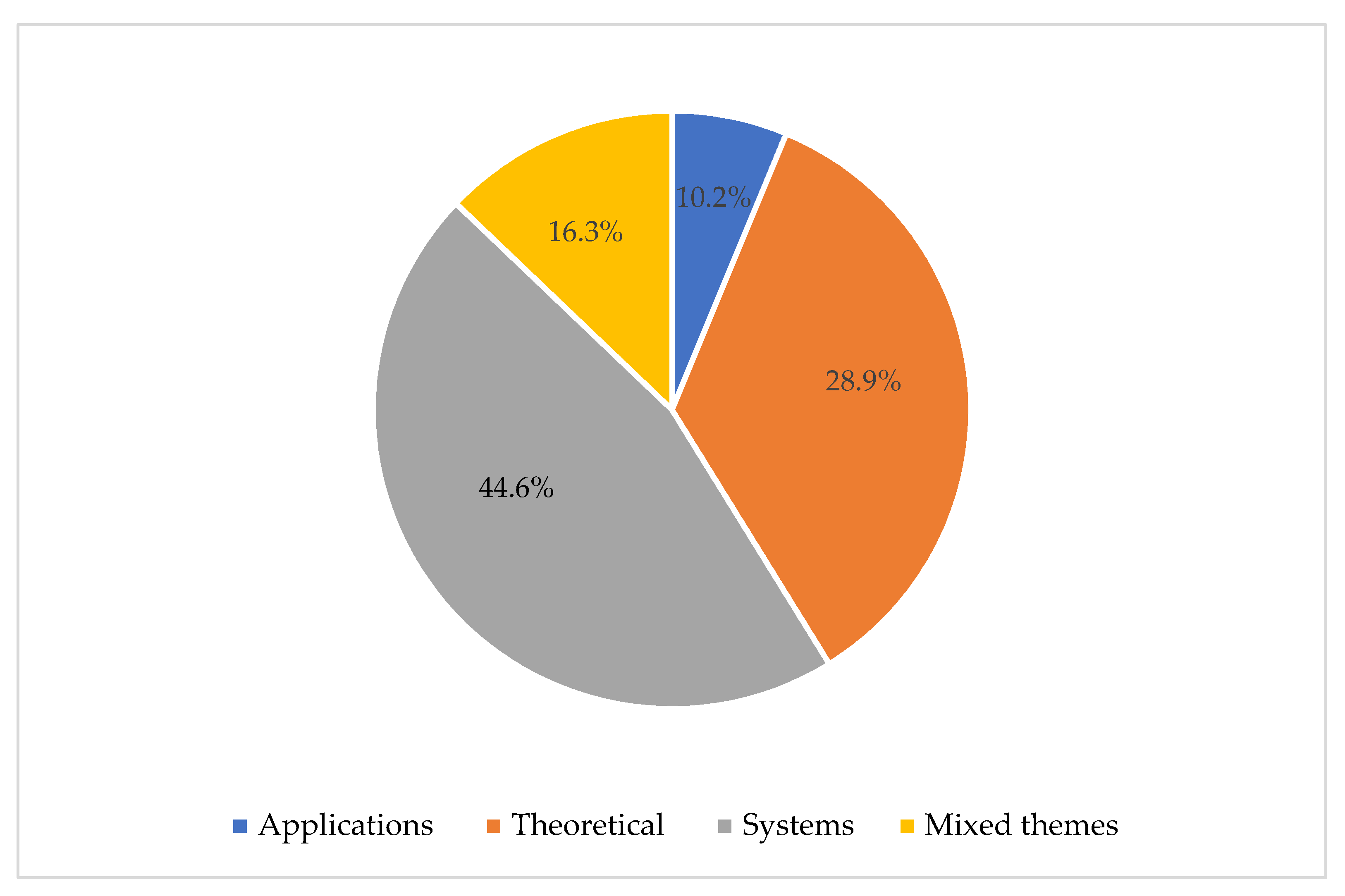

3.2. Research Themes in UEI

3.2.1. Systems Related Studies of UEI

3.2.2. Theoretical Studies

3.2.3. Multiple Themes/Categories

3.2.4. Applications Related Studies of UEI

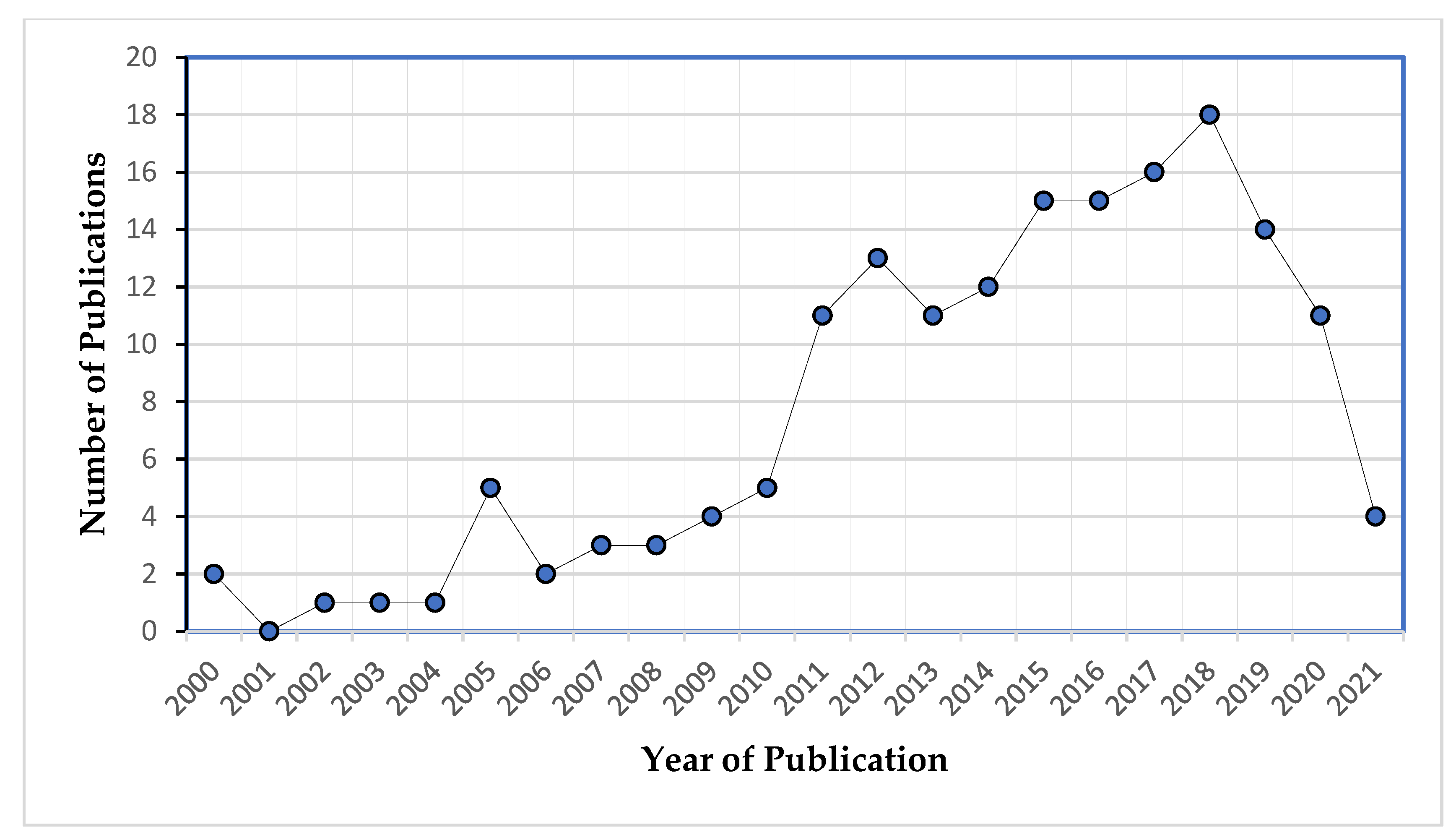

3.3. Trends and Patterns of UEI Publications between the Year 2000 and 2020

3.4. Dominant Economic Activities in UEI

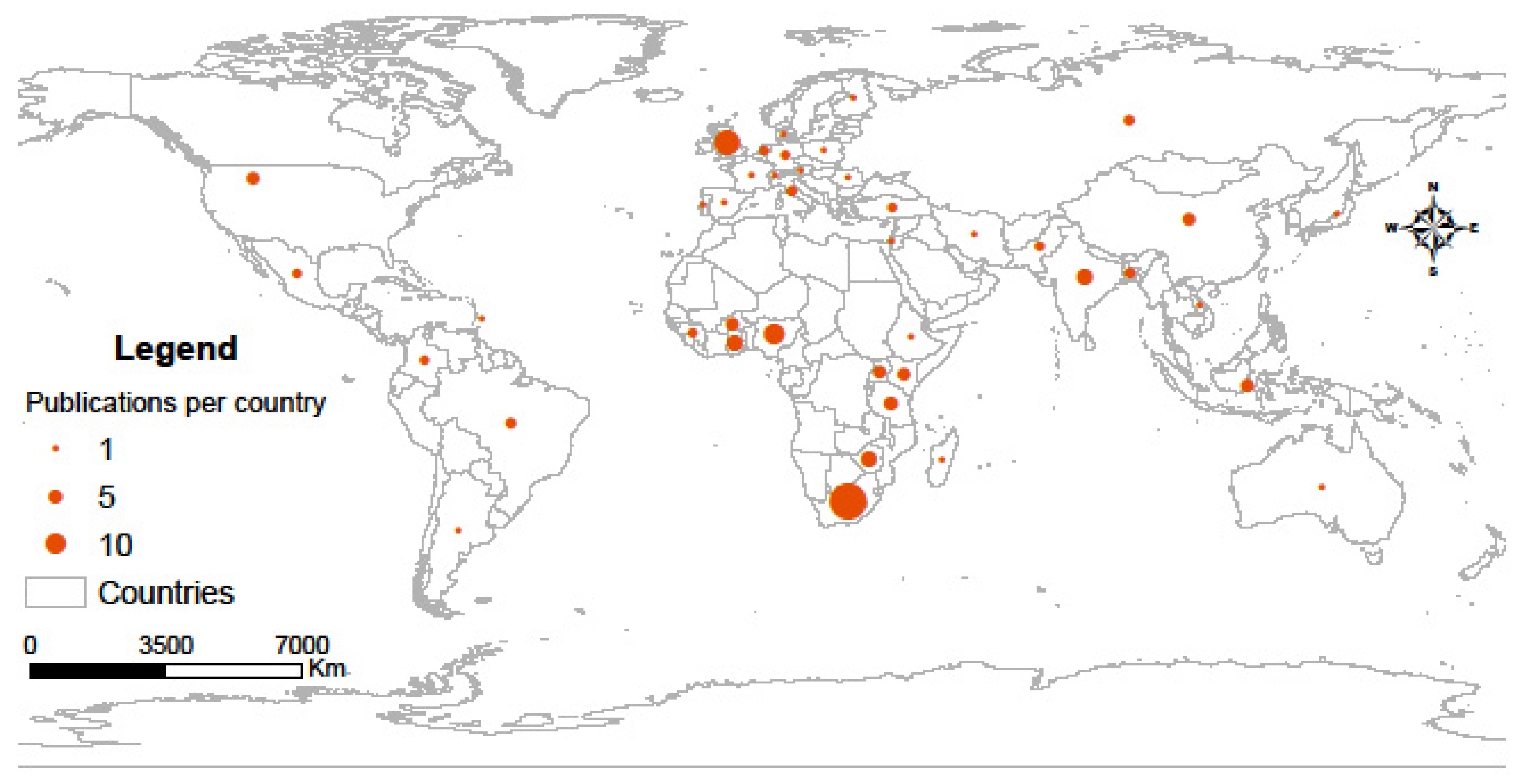

3.5. Geospatial Distribution of UEI Publications

4. Discussion

5. Recommendations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abid, M. Size and Implication of Informal Economy in African Countries: Evidence from a Structural Model. Int. Econ. J. 2016, 30, 571–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombard, M.; Meth, P. Informalities. In Urban Theory; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2016; pp. 180–193. [Google Scholar]

- Banks, N.; Lombard, M.; Mitlin, D. Urban Informality as a Site of Critical Analysis. J. Dev. Stud. 2020, 56, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.A. The Informal Economy: Definitions, Theories and Policies; WIEGO Working Paper; WIEGO: Manchester, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Clement, C. The Formal-Informal Economy Dualism in a Retrospective of Economic Thought Since the 1940s; Schriftenreihe des Promotionsschwerpunkts Globalisierung und Beschäftigung. 2015. Available online: https://www.econstor.eu/handle/10419/107673 (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- Moyo, I.; Gumbo, T. Urban. Informality in South. Africa and Zimbabwe: On Growth, Trajectory and Aftermath; Springer Nature: Berlin, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Damayanti, M.; Scott, N.; Ruhanen, L. Space for the Informal Tourism Economy. Serv. Ind. J. 2018, 38, 772–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnet, F.; Vanek, J.; Chen, M. Women and Men in the Informal Economy: A Statistical Brief; WIEGO: Manchester, UK, 2019; Volume 20, Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_protect/---protrav/---travail/documents/publication/wcms_711798.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2021).

- Chen, M.; Carré, F. The Informal Economy Revisited: Examining the Past, Envisioning the Future; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Radchenko, N. Informal Employment in Developing Economies: Multiple Heterogeneity. J. Dev. Stud. 2017, 53, 495–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koff, H. Informal Economies in European and American Cross-Border Regions. J. Borderl. Stud. 2015, 30, 469–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanchun, B.; Mingyu, C. Transformation of Urban Design from the Perspective of Society-Space Relationship. China City Plan. Rev. 2019, 28, 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Horn, A. Letting Go: Evaluating Spatial Outcomes and Political Decision-Making Heralding the Termination of the Urban Edge in Cape Town, South Africa. Land Use Policy 2018, 78, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassen, S.; Galvaan, R.; Duncan, M. Women’s Experiences of Informal Street Trading and Well-Being in Cape Town, South Africa. South. Afr. J. Occup. Ther. 2018, 48, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A. Urban Informality: Toward an Epistemology of Planning. J. Am. Plann. Assoc. 2005, 71, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A. Why India Cannot Plan Its Cities: Informality, Insurgence and the Idiom of Urbanization. Plan. Theory 2009, 8, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A. Slumdog Cities: Rethinking Subaltern Urbanism. Int. J. Urban. Reg. Res. 2011, 35, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Monroy, A. Critical Commentary. Informality in Space: Understanding Agglomeration Economies during Economic Development. Urban. Stud. 2012, 49, 2019–2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dick, E.; Schmidt-Kallert, E. Understanding the (Mega-) Urban from the Rural: Non-Permanent Migration and Multi-Locational Households. DisP Plan. Rev. 2011, 47, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, G. Models of Urban Migration; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kamete, A.Y. On Handling Urban Informality in Southern Africa. Geogr. Ann. Ser. B Hum. Geogr. 2013, 95, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turok, I. The Prospects for African Urban Economies. Urban. Res. Pract. 2010, 3, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lubida, A.; Veysipanah, M.; Pilesjo, P.; Mansourian, A. Land-Use Planning for Sustainable Urban Development in Africa: A Spatial and Multi-Objective Optimization Approach. Geod. Cartogr. 2019, 45, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryceson, D.F. Birth of a Market Town in Tanzania: Towards Narrative Studies of Urban Africa. J. East. Afr. Stud. 2011, 5, 274–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, K.P. Dualism, Informality and Social Inequality: An Informal Economy Perspective of the Challenge of Inclusive Development in India. Indian J. Labour Econ. 2009, 52, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, P.C. China’s Neglected Informal Economy: Reality and Theory. Mod. China 2009, 35, 405–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potts, D. The Urban Informal Sector in Sub-Saharan Africa: From Bad to Good (and Back Again?). Dev. South. Afr. 2008, 25, 151–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potts, D. The State and the Informal in Sub-Saharan African Urban Economies: Revisiting Debates on Dualism. Cris. States Res. Cent. Work Pap. 2007, 18, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Cypher, J.M. From Structuralism to Neoliberal Depredation and Beyond: Economic Transformations and Labor Policies in Latin America, 1950–2016. Lat. Am. Perspect. 2018, 45, 24–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguimkeu, P. A Structural Econometric Analysis of the Informal Sector Heterogeneity. J. Dev. Econ. 2014, 107, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyo, I.; Nicolau, M.D.; Gumbo, T. Johannesburg (South Africa) Inner City African Immigrant Traders: Pathways from Poverty? In Proceedings of the Urban Forum; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; Volume 27, pp. 329–345. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, A. Peripheral Accumulation in the World Economy: A Cross-National Analysis of the Informal Economy. Int. J. Comp. Sociol. 2013, 54, 420–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Soto, H. The Mystery of Capital: Why Capitalism Triumphs in the West and Fails Everywhere Else; Civitas Books: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey, P.C. Toward a Theory of the Informal Economy. In The Academy of Management Annals; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, C.C.; Franic, J. Explaining Participation in the Informal Economy in Post-Socialist Societies: A Study of the Asymmetry between Formal and Informal Institutions in Croatia. J. Contemp. Cent. East. Eur. 2016, 24, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meagher, K. Social Capital or Analytical Liability? Social Networks and African Informal Economies. Glob. Netw. 2005, 5, 217–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adom, K. Beyond the Marginalization Thesis: An Examination of the Motivations of Informal Entrepreneurs in Sub-Saharan Africa: Insights from Ghana. Int. J. Entrep. Innov. 2014, 15, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogerson, C.M. Emerging from Apartheid’s Shadow: South Africa’s Informal Economy. J. Int. Aff. 2000, 673–695. [Google Scholar]

- Gallaway, J.H.; Bernasek, A. Gender and Informal Sector Employment in Indonesia. J. Econ. Issues 2002, 36, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Schumacher, K.P. Conceptualizing the Survival Sector in Madagascar. Antipode 2012, 44, 321–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, L.; Short, J.R.; Estrada, D. The Urban Informal Economy: Street Vendors in Cali, Colombia. Cities 2017, 66, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diallo, A. Assessing the Socioeconomic Impacts of the Informal Sector in Guinea, West Africa. Open Access Libr. J. 2017, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bairagya, I. Employment in India’s Informal Sector: Size, Patterns, Growth and Determinants. J. Asia Pac. Econ. 2012, 17, 593–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillani, D.Q.; Khan, R.E.A. Socio-Economic Determinants of Urban Informal Sector Employment: A Case Study of District Bahawalpur. Pak. Perspect. 2013, 18, 133–149. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo, M.; Kilama, B.; Wuyts, M. The Invisibility of Wage Employment in Statistics on the Informal Economy in Africa: Causes and Consequences. J. Dev. Stud. 2015, 51, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamieldien, F.; Van Niekerk, L. Street Vending in South Africa: An Entrepreneurial Occupation. South. Afr. J. Occup. Ther. 2017, 47, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeng-Odoom, F.; Ameyaw, S. A New Informal Economy in Africa: The Case of Ghana. Afr. J. Sci. Technol. Innov. Dev. 2014, 6, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, L.M.; Charman, A.J.E. The Scope and Scale of the Informal Food Economy of South African Urban Residential Townships: Results of a Small-Area Micro-Enterprise Census. Dev. South. Afr. 2018, 35, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, S.; Musango, J.K. Exploring the Connections between Green Economy and Informal Economy in South Africa. South. Afr. J. Sci. 2015, 111, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Meagher, K. The Scramble for Africans: Demography, Globalisation and Africa’s Informal Labour Markets. J. Dev. Stud. 2016, 52, 483–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, C. Falling Though the Policy Gaps? Evidence from the Informal Economy in Durban, South Africa. In Proceedings of the Urban Forum; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; Volume 17, pp. 125–148. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, C.C.; Round, J. A Critical Evaluation of Romantic Depictions of the Informal Economy. Rev. Soc. Econ. 2008, 66, 297–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgin, C.; Oztunali, O. Institutions, Informal Economy, and Economic Development. Emerg. Mark. Finance Trade 2014, 50, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welter, F.; Smallbone, D.; Pobol, A. Entrepreneurial Activity in the Informal Economy: A Missing Piece of the Entrepreneurship Jigsaw Puzzle. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2015, 27, 292–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgin, C.; Oyvat, C. Lurking in the Cities: Urbanization and the Informal Economy. Struct. Change Econ. Dyn. 2013, 27, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyebueke, V.; Geyer, M. The Informal Sector in Urban Nigeria: Reflections from Almost Four Decades of Research. Town Reg. Plan. 2011, 59, 65–76. [Google Scholar]

- Thukral, J. Race, Gender, and Immigration in the Informal Economy. RaceEthnicity Multidiscip. Glob. Contexts 2010, 4, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C.C.; Shahid, M.S.; Martínez, A. Determinants of the Level of Informality of Informal Micro-Enterprises: Some Evidence from the City of Lahore, Pakistan. World Dev. 2016, 84, 312–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratap, S.; Quintin, E. Are Labor Markets Segmented in Developing Countries? A Semiparametric Approach. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2006, 50, 1817–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerxhani, K. The Informal Sector in Developed and Less Developed Countries: A Literature Survey. Public Choice 2004, 120, 267–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devey, R.; Skinner, C.; Valodia, I. Second Best? Trends and Linkages in the Informal Economy in South Africa; Working Paper; Development Policy Research Unit: Cape Town, South Africa, 2006; Available online: https://media.africaportal.org/documents/DPRU_WP06-102.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2021).

- Yusuff, O.S. A Theoretical Analysis of the Concept of Informal Economy and Informality in Developing Countries. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. 2011, 20, 624–636. [Google Scholar]

- Moyo, I. A Case Study of Black African Immigrant Entrepreneurship in Inner City Johannesburg Using the Mixed Embeddedness Approach. J. Immigr. Refug. Stud. 2014, 12, 250–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gezahagn, W. Gender-Wise Determinant of Informal Sector Employment in Jigjiga Town: A Cross Sectional Study. J. Econ. Int. Financ. 2017, 9, 62–67. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner, C.; Valodia, I. Local Government Support for Women in the Informal Economy in Durban, South Africa. Int. J. Polit. Cult. Soc. 2003, 16, 431–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khotkina, Z.A. Employment in the Informal Sector. Anthropol. Archeol. Eurasia 2007, 45, 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodore, N.; Blaauw, D.; Schenck, C.; Valenzuela, A., Jr.; Schoeman, C.; Meléndez, E. Day Labor, Informality and Vulnerability in South Africa and the United States. Int. J. Manpow. 2015, 36, 807–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, S.; Chakrabarti, S. Rural-Urban Linkages, Labor Migration & Rural Industrialization in West Bengal. Indian J. Ind. Relat. 2015, 50, 397–411. [Google Scholar]

- Kabeer, N.; Natali, L. Gender Equality and Economic Growth: Is There a Win-Win? IDS Work. Pap. 2013, 2013, 1–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Informal Enterprises in Kenya; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mhando, P.C. Managing in the Informal Economy: The Informal Financial Sector in Tanzania. Afr. J. Manag. 2018, 4, 282–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Thulare, M.H.; Moyo, I.; Xulu, S. Systematic Review of Informal Urban Economies. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11414. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132011414

Thulare MH, Moyo I, Xulu S. Systematic Review of Informal Urban Economies. Sustainability. 2021; 13(20):11414. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132011414

Chicago/Turabian StyleThulare, Mpendulo Harold, Inocent Moyo, and Sifiso Xulu. 2021. "Systematic Review of Informal Urban Economies" Sustainability 13, no. 20: 11414. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132011414

APA StyleThulare, M. H., Moyo, I., & Xulu, S. (2021). Systematic Review of Informal Urban Economies. Sustainability, 13(20), 11414. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132011414