Abstract

The aim of this study was to identify the preferences of final purchasers regarding the environment of cooperation with offerors and the benefits of cooperation, as well as to identify dependencies between two groups of preferences, taking into account the age of purchasers. The results of an analysis of the global literature on the subject indicate that so far these issues have not been studied, either in relation to the energy market or other areas of the consumer market. Therefore, we can talk about a cognitive and research gap in this area. In order to reduce the gap, seven research hypotheses were formulated and primary research was carried out on 1196 adult representatives of final purchasers in Poland to verify the hypotheses. The collected data were subjected to quantitative analysis, the results of which made it possible to state that most respondents preferred the parallel use of the online and offline environments as a place of interaction with offerors. More than half of the respondents stated that a combination of material and non-material benefits achieved through cooperation with offerors effectively encourages purchasers to undertake this cooperation. Non-material benefits such as the possibility of gaining new knowledge, the possibility of gaining new skills, and the possibility of establishing relationships with new people turned out to be particularly important. Statistically significant dependencies were identified between the preferences regarding the environment of cooperation and preferences regarding the benefits of cooperation. Moreover, dependencies were identified between age and the general specificity of benefits of cooperation with offerors, and between age and twelve specific benefits of cooperation. Conclusions drawn from the results obtained have great cognitive and application value, enriching knowledge of the behavior of final purchasers and making it easier for offerors, including companies operating on the consumer energy market, to make effective decisions about encouraging recipients to cooperate in the process of creating a marketing offer.

1. Introduction

One of the key challenges faced by modern enterprises operating on the consumer market is meeting the rapidly growing requirements of final purchasers. Moreover, purchasers’ requirements increasingly relate not only to a marketing offer, including its product and non-product features, but also to various aspects reflecting relationships between purchasers and offerors. These requirements include expectations regarding the role offerors assign to final purchasers. The classic division of market roles unambiguously separating the role of the recipient from the role of the supplier is frequently not consistent with the current preferences of final purchasers. In the modern consumer market, it is more and more common for final purchasers to try to fulfill a much more active market role [1] and engage more fully in various marketing activities undertaken by offerors, including companies operating on the energy market.

The effect of searching for the possibility of meeting this type of expectation is engaging in cooperation with offerors [2], both spontaneously and under the influence of incentives offered by offerors to final purchasers. On the one hand, participation in the co-creation of various elements of a marketing offer allows purchasers to meet the needs related to active involvement in their creation, and on the other hand, it allows many other benefits to be achieved. Of course, offerors also benefit from this cooperation [3]. With regard to the energy market, literature even mentions a community focused around energy (‘energy communities’) which achieves numerous benefits by generating new solutions of a market and social nature [4,5].

Therefore, it is even more important to apply a marketing approach to the issue of cooperation between final purchasers and offerors which is based on the need to systematically identify purchasers’ preferences regarding the environment of cooperation and the benefits that can be achieved. Guided by these preferences, purchasers choose a specific type and scope of their market activity. Thus, in this case, we can talk about a decision-making process, the effect of which is mutually beneficial cooperation between final purchasers and offerors, provided that the scope, specificity, and value of benefits perceived by purchasers exceed the estimated expenditure necessary to undertake cooperation.

The results of an analysis of global literature, which are presented later in this article, revealed a cognitive and research gap concerning the importance of preferences regarding the environment of cooperation between final purchasers and offerors in relation to (1) the general specificity of the preferred benefits of cooperation and (2) the preferred specific benefits of cooperation. This gap concerns all the more the importance of final purchasers’ age in terms of their preferences in the above-mentioned areas.

Therefore, this study was conducted to solve the following research problem: what the importance of final purchasers’ preferences related to the environment of cooperation with offerors is, depending on the age of purchasers, in relation to (1) the general specificity of benefits of cooperation expected by purchasers and (2) the expected specific benefits of cooperation. The aim of this research was, therefore, to identify final purchasers’ preferences regarding the environment of cooperation with offerors and the benefits of this cooperation, and to identify the dependencies between both groups of preferences, taking into account the age of purchasers.

This article was structured to achieve this aim and to verify seven research hypotheses. It includes a literature review, a presentation of primary data and results, an academic discussion, implications, limitations, and the direction of future studies.

2. Literature Review

The contemporary consumer market is characterized by increasing volatility [6], while becoming less and less predictable. It can be identified with a turbulent system of relationships between its participants, where final purchasers and offerors (i.e., producers, traders, and service providers) play a key role. Their relationships may have a different configuration, time horizon, purpose for which they were established, etc., which results in a greater or lesser strength of mutual connections.

In the classically understood division of market roles fulfilled by final purchasers and offerors, these relationships were usually characterized by relatively less strength, as they were established only in order to purchase a specific product. They were primarily based on purchasing behavior, which was the limit of the market activity of final purchasers. Many authors identified only these behaviors with the overall market behavior of purchasers [7]. In such a system, purchasers played the role of passive recipients, and offerors mainly played the role of suppliers, being the dominant party that determined conditions for the functioning of this system. Decisions made by final purchasers concerned only or mainly the type and/or value of the purchased products. This was evident in virtually every product group, including products offered on the energy market [8].

The nature of mutual relationships between final purchasers and offerors has changed, among other things due to the growing expectations of purchasers. These expectations concerned not only marketing offers available on the market, but also the role assigned to purchasers. Searching for opportunities to meet these expectations, purchasers began to show greater openness to engaging in non-purchasing behaviors, including communication and creation. The changes taking place in mutual relationships between final purchasers and offerors resulted, among other things, in a significant increase in the scope and level of purchasers’ market activity [2]. They have ceased to fulfill the role of ‘passive recipients’ and became ‘new purchasers’ [1] or ‘active purchasers’ [9], i.e., prosumers [10] who engaged in the creation of various elements of marketing offers either spontaneously or through incentives. Thus, the complexity of the decision-making process has increased, especially from the point of view of final purchasers. The decisions they make have begun to concern the very fact of joining the process of cooperation with offerors, and after making a positive decision, also the scope and specificity of mutual cooperation. This trend has become clearly visible in various industries, including the energy market, where purchasers have begun to be referred to as ‘active recipients’ [11] or even ‘key actors’ [12] of the market game.

Obviously, final purchasers’ openness to cooperation posed big challenges for offerors who had to redefine the existing business model in favor of a model based on a much greater empowerment of purchasers. This required a change in the scope and level of offerors’ activity towards creating conditions (e.g., mental and infrastructural) [13] conducive to initiating and developing cooperation with offerors. Offerors no longer act solely as product suppliers. In the new relational system, both parties have begun to play the role of both the supplier and the recipient, bringing values to mutual cooperation (including abilities, experience, and knowledge [14]) and increasing marketing potential of every value. This contributed to the creation of a common, unique potential, positively influencing mutual relationships by strengthening them even more.

It is worth explaining that in this article, the term ‘final purchaser’, instead of ‘consumer’ (which is usually used by other researchers), is used deliberately. A final purchaser is a person who purchases a product and is also its consumer if they use the product themselves. Therefore, these terms are not synonyms [15]. In the present study, people who make the purchase were analyzed, which justifies the use of the concept ‘final purchaser’. When considering cooperation, the term ‘offeror’ is also used to denote the other side of the relational system that connects an active purchaser with an enterprise. This procedure is deliberate. In the literature, analyses are usually narrowed down to producers [1,16]; however, in practice, cooperation may occur not only between purchasers and producers, but also between purchasers and service providers, and purchasers and traders (retailers). Cooperation may also involve undertaking joint actions with other purchasers [17]. The effect of such cooperation in practice, however, always affects an offeror, beginning with the building of their image (good or bad) and ending with the creation of a loyal community of supporters of a given brand or a company. Therefore, it is extremely important to effectively manage communication and the creative activity of final purchasers [18] initiated as part of inter-purchasing cooperation, i.e., cooperation occurring without the direct participation of offerors.

Cooperation between active purchasers and offerors can be defined as undertaking joint actions aimed at creating products and other elements of a marketing offer so that their material and non-material features effectively meet the expectations of final purchasers [19], bringing both the purchasers and offerors various measurable and immeasurable benefits. These actions must be effectively managed [20] so that they contribute to an increase in the competitive abilities of offerors [3]. The interaction between active purchasers and offerors is closely related to the ‘value co-creation’ paradigm [21,22,23] and the concept of ‘consumer-centric product’ [24], orienting their mutual relationships in the future.

The advantage of such relationships over the relational system characteristic of the traditionally understood relationships between final purchasers and offerors results to a large extent from the benefits achieved by both parties thanks to mutual cooperation [16], which definitely outweigh the effects [25] achieved within the traditional business model based on the disconnection of market roles.

From the point of view of active purchasers, the perceived benefits, which they would not be able to obtain under the traditional division of market roles, are particularly important. Although some researchers point out that purchasers join cooperation for altruistic reasons [26], without expecting any benefits, it must not be forgotten that the mere fulfillment of the need to be useful is a benefit achieved through cooperation. The final purchasers’ comparative analysis of the expected benefits of cooperation with the expenditure that must be incurred to undertake and conduct this cooperation is one of the key stages of a decision-making process. The results of such a comparison usually determine the involvement in cooperation or the lack of it.

All benefits obtained by final purchasers thanks to cooperation with offerors can be divided into two main groups: non-material and material ones. In the literature, the importance of non-material benefits is emphasized. They are analyzed either in general as developmental benefits [27] or in a detailed way. In the case of this second approach, the non-material benefits include gaining new knowledge [28], gaining new skills [16], gaining new experience and/or sharing it [29], gaining social benefits [26] such as establishing relationships with other entities, and achieving psychological effects, including satisfaction [30]. The cash prize or material prize can be counted as the material benefits but these benefits cannot be obtained on a regular basis. It is emphasized that active purchasers (prosumers) do not receive remuneration [31] for their contribution to the preparation of a specific element of an offer, which is one of the main assumptions of prosumption. However, for some product groups, e.g., on the energy market, prosumers can achieve financial benefits in the form of lower prices for energy which they co-create in cooperation with offerors [12,32].

In the literature, in addition to the benefits achieved through cooperation, the driving forces behind the development of the cooperation include the development of Internet technology (inter alia Dellaert [1]; Kozinets, Patterson, and Ashman [33]). Many authors even equate interaction between final purchasers and offerors with online activity [13,34,35,36]. However, such an approach seems to be too much of a simplification, as it does not take into account various forms of prosumer activity undertaken in the real world, where most of the activities as such still take place. Certainly, unpredictable aspects such as the COVID-19 pandemic and the resulting restrictions have caused a change in final purchasers’ behavior [37]. There has been a sharp increase in their activity online (especially on social media [38]). However, even in pandemic conditions, purchasers’ involvement has not been eliminated from the offline environment.

It should be added that the literature discusses the interaction between active purchasers and offerors in various contexts, e.g., by analyzing the scope of purchaser activity online [39], the determinants of this activity [13,14,40], and the determinants of the intentions to cooperate [28], the scope of purchaser involvement according to the phases of a new product development process [41], and by considering possible future scenarios for the development of cooperation with offerors [12].

On the other hand, final purchasers’ preferences regarding the environment of cooperation and the expected benefits have not been studied; nor has the relationship between the preferred environment of cooperation and these benefits. Of course, no in-depth research has been carried out, which would analyze the above-mentioned aspects in the context of final purchasers’ age. Therefore, a cognitive and research gap exists for this area. In order to reduce the gap, this article attempts to define final purchasers’ preferences regarding the environment of cooperation with offerors and the benefits of this cooperation, and identify the dependencies between both groups of preferences, taking into account purchasers’ age.

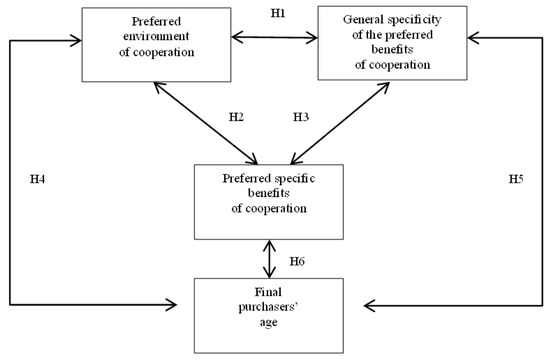

Because the studies in the mentioned scope have not yet been conducted, to achieve this aim, the following research hypotheses were verified:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

There is a dependence between the environment of cooperation with offerors preferred by final purchasers and the general specificity of the preferred benefits of this cooperation;

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

There is a dependence between the environment of cooperation with offerors preferred by final purchasers and the preferred specific benefits of this cooperation;

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

There is a dependence between the general specificity of the preferred benefits of cooperation with offerors and the preferred specific benefits of this cooperation;

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

There is a dependence between final purchasers’ age and the preferred environment of cooperation with offerors;

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

There is a dependence between final purchasers’ age and the general specificity of the preferred benefits of cooperation;

Hypothesis 6 (H6).

There is a dependence between final purchasers’ age and the preferred specific benefits of cooperation;

Hypothesis 7 (H7).

Final purchasers’ age is a feature that differentiates their preferences regarding specific benefits of cooperation with offerors.

The occurrence of the assumed dependencies is presented graphically on the conceptual model (Figure 1). It is worth noting that this model reflects the assumptions of six hypotheses concerning the dependencies between particular variables. However, this model does not show the assumption presented in hypothesis H7 as it is impossible to graphically show this differentiation.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model.

3. Research Methodology

To achieve the aim of this study and to verify the research hypotheses, empirical research was conducted. The primary data were collected by means of the Internet research method via the CAWI (computer-assisted web interview) technique using the questionnaire as the research tool consisting of closed questions only. The survey was carried out in mid-2020 among 1196 adult representatives of final purchasers from Poland. According to the approach adopted in this study, the aim was to identify final purchasers’ opinions, without narrowing down the analysis to a specific product or group of products. This made it possible to define respondents’ preferences with regard to cooperation with offerors as a phenomenon that permeates various spheres of life, through the prism of the environment of this cooperation and the benefits associated with it.

The geographic scope of the conducted research was nationwide. The research was panel-based. The sample was based on a quota. The socio-demographic characteristics (i.e., gender, age, education, and region) were dispersed proportionally to the distribution of a feature in the general population, with a deviation of no more than 10 respondents in relation to the proportion for the distribution of the entire Polish population (based on Główny Urząd Statystyczny (Central Statistical Office) data and the computer-assisted personal interview (CAPI) population studies).The sample size was determined according to the Cochran formula [42] based on the total population of Poles in 2020 amounting to 38,652,000 people, including 32,962,000 adult residents [43], and using a 3% margin of error and 95% confidence level [44]. Most of the respondents, according to the structure of the general population, were women (52%). For the needs of the research process, the respondents were divided into four age groups, the share of which was as follows: between 18 and 30 years old (26.6%), between 31 and 43 years old (50.3%), between 44 and 56 years old (18.7%), and over 56 years old (4.4%). This structure corresponded to the age structure of the general population.

The subject scope of the article covers the following groups of variables: the preferred environment of cooperation between final purchasers and offerors and the benefits expected by final purchasers from cooperation with offerors in general and in detail. An attempt was made to check whether there are statistically significant dependencies between these groups and whether there are dependencies between single groups and the age of respondents.

During the research, respondents were asked to indicate their preferences regarding the environment of cooperation with offerors (online, offline, both of these environments) and indicate the importance attached to the generally understood benefits of cooperation (material, non-material, both types are equally important). Moreover, they were presented with a set of thirteen specific benefits that can be achieved by final purchasers through cooperation with offerors. The benefits were distinguished based on the results of an analysis of the literature (inter alia Mandolfo, Chen, and Noci [16]; Kleber and Volkova [45]) and the results of preliminary unstructured interviews. These interviews were conducted among 20 representatives of adult final purchasers in Poland.

Each specific benefits of cooperation with offerors was assessed by respondents on the odd Likert scale, which is one of the most fundamental and most frequently used psychometric tools in social sciences [46]. In this study, a five-step variant was used, in which a rating of 5 corresponded to ‘definitely yes’, a rating of 4 corresponded to ‘rather yes’, a rating of 3 corresponded to ‘neither yes nor no’, a rating of 2 corresponded to ‘rather not’, and a rating of 1 corresponded to ‘definitely not’. The use of such a scale was a necessary condition for the method of average score analysis.

The primary data collected were subjected to quantitative analysis using the method of average score analysis, the comparative analysis, the Pearson Chi-square independence test, the analysis of the V-Cramer contingency coefficient value, and the analysis of the Kruskal–Wallis test value.

The Chi-square test was used to determine whether there were statistically significant dependencies between the analyzed variables, and the V-Cramer coefficient was used to determine the strength of the dependencies between the analyzed variables. The V-Cramer coefficient is used when at least one variable has more than two values [47], i.e., when the contingency table is at least 2 × 3.

The Kruskal–Wallis test is a non-parametric equivalent of ANOVA [48]. Its results determine whether the differentiation, in terms of the separation of individual groups of respondents (e.g., the age of respondents divided into four age groups) is statistically significant enough to say that the opinion of a respondent specified by the analyzed answer is significantly different. From the point of view of statistical criteria, in the case of the KW test, it is not necessary for the data to meet many requirements. The only requirements for its implementation are the following [49]:

- -

- the dependent variable should be measured on at least ordinal scale (it can also be measured on a quantitative scale),

- -

- observations in the analyzed groups should be independent of each other, which means that a person in one group should not be included in another group that is compared at the same time (this requirement is met by questions that allowed for the division of respondents into distinct groups, and in the case of the KW test there should more than two groups).

Statistical analysis of the primary data collected was performed using the IBM SPSS Statistics Ver. package. 25.

4. Research Results

The results of this study show that as many as 68.4% of all respondents preferred to use jointly both environments (online and offline) as places of cooperation with offerors (Table 1). The percentage of people who chose the Internet was definitely smaller. Identifying prosumer activity with actions undertaken only in the online environment is therefore unjustified, as it turned out to be inconsistent with the expectations of respondents.

Table 1.

The respondents’ preferred environment of cooperation with offerors during the preparation of marketing offers (%).

The respondents were also asked about the significance assigned to material and non-material benefits that could possibly be obtained through cooperation with offerors. As shown in Table 2, two-thirds of all respondents stated that both types of benefits are equally valuable to them. Moreover, non-material benefits were relatively more important for over four times more respondents than for those who attributed the greatest importance to material benefits.

Table 2.

General benefits of cooperation with offerors chosen by the respondents as more important (%).

Therefore, a question arises whether there is a statistically significant dependence between the preferred environment of cooperation with offerors and the general specificity of benefits obtained from such cooperation. It turns out that such a dependence exists, although it is weak (Table 3). The research hypothesis H1 for respondents is therefore valid.

Table 3.

Respondents’ preferred environment of cooperation with offerors and the general benefits of cooperation with offerors chosen by respondents as more important.

In the next stage of the analysis, an attempt was made to identify specific benefits that, according to the respondents, a final purchaser achieves by engaging in cooperation with offerors on the preparation of marketing offers. Among the thirteen benefits included in the analysis, seven received an average score of more than 4.00, including five of them with a value greater than 4.40 (Table 4). This group includes benefits related to meeting the following needs: a need of knowledge and self-realization through increasing one’s intellectual potential (‘gaining new knowledge’, ‘gaining new skills’, and ‘gaining new experience’), and social needs through increasing one’s relational potential (‘establishing relationships with other people’), as well as satisfying benefits associated with obtaining an offer consistent with purchaser expectations. As can be seen, all of these benefits were non-material, which confirms the results obtained by a direct question about the importance of material and non-material benefits.

Table 4.

Specific benefits indicated by respondents that are achieved by a final purchaser thanks to cooperation with offerors during the preparation of marketing offers.

Both benefits of typically material nature (‘obtaining a cash prize’, ‘obtaining a material prize’) took much higher places, outstripping only the benefits related to satisfying psychological needs (‘impressing other people’, ‘gaining respect from other people’) and benefits related to ‘filling up excess free time’, which took the last position (it was the only benefit which received an average score of only slightly above 3.00). It should be added that for each of the analyzed benefits, the standard deviation did not exceed one-third of the average score, which indicates that the average values accurately reflect the hierarchy of the analyzed benefits [50].

The next stage of the analysis consisted in identifying the dependencies between specific benefits achieved through cooperation with offerors and (1) the preferred environment of this cooperation and (2) the importance assigned to the benefits, taking into account their material or non-material nature. The results of the research showed statistically significant dependencies in the first case for seven analyzed benefits, and in the second case for nine of them (Table 5). Therefore, it can be concluded that for these benefits, in the case of respondents, the research hypotheses H2 and H3, respectively, are valid. In the case of six benefits, such dependencies were identified both for the preferred environment of cooperation and the significance attributed to the benefits according to their nature (in this case, the identified dependencies were relatively stronger, as evidenced by higher values of the V-Cramer coefficient). These aforementioned six benefits included non-material ones (related to increasing one’s intellectual and relational potential) and material ones (obtaining a cash and material prize).

Table 5.

Specific benefits chosen by the respondents which a final purchaser achieves thanks to cooperation with offerors compared with the preferred environment of cooperation and the importance attached to the benefits achieved according to their general specificity.

It is worth noting that for the benefit of ‘the possibility of obtaining an offer that better meets purchaser expectations’, which took one of the key positions in the hierarchy, a dependence with the preferred environment of cooperation was discovered, but no dependence was identified between said benefit and the importance attributed to the achieved benefits according to their specificity. In turn, a dependence was discovered between the importance attributed to the achieved benefits and the benefit of ‘filling up excess free time’, which was ranked last in the hierarchy. It should also be added that all of the identified dependences are weak, as their V-Cramer’s coefficient values did not exceed 0.3.

In the next stage of the research process, it was checked whether there were any dependencies between the age of respondents and their preferences regarding (1) the environment of cooperation with offerors, (2) the general specificity of benefits of this cooperation, and (3) specific benefits of this cooperation. As shown in Table 6, a statistically significant dependence was identified for age and the general specificity of the preferred benefits, although this dependence is weak. However, no dependence was observed between age and the preferred environment of cooperation with offerors. As for the specific benefits of this cooperation, statistically significant dependencies were identified for twelve out of thirteen benefits studied (Table 7), but these were weak dependencies, as evidenced by the V-Cramer coefficient value which did not exceed the limit of 0.3. It is worth recalling that the value of the V-Cramer coefficient can range from 0.0 to 1.0. No statistically significant dependence was discovered only for the benefit of ‘the possibility of testing the suitability of one’s ideas’, for which the level of significance p exceeded the limit value, i.e., 0.05. Thus, it can be said that for respondents, the research hypothesis H4 turned out to be invalid. However, the hypothesis H5 is valid. As for the hypothesis H6, in the case of the respondents, it turned out to be valid for twelve specific benefits analyzed.

Table 6.

The age of respondents compared with the preferred environment of cooperation with offerors and the benefits of cooperation with offerors indicated by respondents as more important.

Table 7.

Specific benefits indicated by respondents that a final purchaser achieves thanks to cooperation with offerors versus respondents’ age.

In the last stage of the analysis, the Kruskal–Wallis test was performed to verify the results obtained by applying the Chi-square independence test. The results presented in Table 8 demonstrate that the age of respondents was a feature that statistically significantly differentiated responses concerning twelve specific benefits of cooperation with offerors. For the benefit of ‘the possibility of testing the suitability of one’s ideas’, the significance level p exceeded the threshold value of 0.05. Therefore, we cannot talk about any differentiation only in the case of this benefit. It is the same benefit, in which case no statistically significant dependence was identified. For respondents, the research hypothesis H7 turned out to be valid for twelve out of the thirteen benefits analyzed.

Table 8.

Results of the analysis of the significance of differences between respondents’ indications concerning specific benefits achieved by a final purchaser thanks to cooperation with offerors, according to the age of respondents.

To summarize the main results obtained are shown in the Table 9.

Table 9.

Results of testing research hypotheses.

5. Discussion

The results of this study indicate that almost 70.0% of respondents preferred combining both environments (online and offline) as places of cooperation with offerors. Therefore, prosumption should not be equated solely with the involvement of final purchasers in joint activities online, although with regard to contemporary purchasers, the literature often concerns it only or primarily with the Internet [39,51].

Some authors point out that the use of modern technologies enhances purchasers’ passion with regard to purchase and usage behavior (inter alia Kozinets, Patterson, and Ashman [33]). However, based on the results of this study, it seems that a similar conclusion can also be drawn in the case of prosumer behavior. Among the benefits that can be achieved through cooperation with offerors, the respondents highlighted ‘gaining new knowledge and skills’ and ‘establishing relationships with new people’, which undoubtedly requires emotional involvement, i.e., a kind of passion for going beyond the stereotypical behavior attributed to a final purchaser. It is also worth adding that emotions and experiences were identified by other authors as the key drivers of purchasers’ sustainable behavior [52,53]. It is true that these behaviors were analyzed in relation to purchasing behavior, but, together with prosumer (i.e., communication and creative) behavior, they can also be considered in the context of sustainable market activity (as a triad of behaviors) which can lead to the achievement of benefits important for active purchasers, among which the leading places are occupied by the effects related to experience and building good relationships.

Bettiga, Lamberti, and Noci [26] examined the motives of purchasers’ willingness to cooperate. However, the benefits expected can be equated with motives for a specific action. These researchers observed that altruism and social aspects were among the key motives behind the willingness to cooperate. These results partially correspond to the results of the research presented in this article, in which the possibility of establishing relationships with other entities was among the most important benefits for respondents. It should be emphasized, however, that Bettiga, Lamberti, and Noci analyzed inter-purchase cooperation within virtual communities. Therefore, the subject of their research was different; moreover, these authors focused on only one environment of cooperation. Chen, Drennan, Andrews, and Hollebeek [29] also included purchasers in their studies, analyzing their interaction within virtual communities. They discovered that sharing experience is the key driving force behind cooperation. The fact that in this study the respondents assigned great importance to ‘the possibility of gaining new experience’ proves that these kinds of effects are significant both in the case of cooperation with other purchasers (as demonstrated by other authors) and with offerors (as indicated by the results of the study presented in this article).

On the other hand, Neghina, Bloemer, Birgelen, and Caniëls [27] showed that developmental motives play a key role in the co-creation of professional services. Their research had a different subject scope, and, moreover, these authors did not deal with specific motives, but with a whole group. It is worth noting, however, that in this study, the most important benefit for the largest part of the respondents was ‘the possibility of gaining new knowledge’. High positions were also taken by ‘the possibility of gaining new skills’, ‘the possibility of gaining new experience’, and ‘the possibility of establishing relationships with other entities’. All of these aspects lead to a personal and social development of a given prosumer; therefore, they are developmental aspects. Therefore, from this point of view, the results of the research conducted confirm the results of research conducted by other researchers. Comparing the subject scope of studies conducted by other researchers, it can also be stated that they did not focus either on analyzing dependencies between the preferred environment of cooperation with offerors and the specificity of the expected benefits of such cooperation, or preferences regarding specific effects that respondents would like to achieve thanks to cooperation with offerors.

It is worth adding that in the case of the specific energy market, when considering cooperation between final purchasers and offerors, other researchers focus on individual, measurable benefits such as the possibility of obtaining energy at a lower price [12], or non-material collective (or even social) benefits such as the protection of environment [54,55,56]. On the other hand, the results of present study show that also in the individual dimension, the respondents definitely preferred non-material benefits.

As far as age and its importance in relation to various aspects of final purchasers’ involvement in cooperation with offerors is concerned, the literature includes, among other things, research on dependencies between purchasers’ age and their willingness to engage in prosumer behavior in general. However, these studies focus primarily on presumption considered as a market phenomenon and/or market trend, and they do not analyze either the preferred benefits of this cooperation or the preferred environment for its conduct. For example, Burgiel and Sowa [57] discovered that there is a dependence between readiness for prosumption and the age of respondents; however, their studies covered only representatives of two generations, X and Y. In turn, Eisenbardt identified a statistically significant differentiation of opinions concerning the expected stimuli encouraging cooperation according to age [58] or organizations’ offer [59]. However, this author studied cooperation only in terms of sharing knowledge with other entities.

6. Conclusions

Taking into account the research problem, it must be underlined that most of the respondents preferred to use both environments, i.e., online and offline, at the same time to cooperate with offerors. Only 6.3% of the respondents considered material benefits to be the more important incentives encouraging them to undertake such cooperation. It was more than four times lower percentage than the percentage of respondents who indicated non-material benefits as more important. The results of the analysis of specific benefits achieved by final purchasers as a result of cooperation with offerors confirm that non-material benefits are of key importance. The highest position in the hierarchy was taken by the benefit of ‘the possibility of gaining new knowledge’, followed closely by the benefits of ‘the possibility of gaining new skills’, ‘the possibility of obtaining a marketing offer that better meets purchaser expectations’, and ‘the possibility of establishing relationships with other people’.

A statistically significant dependence was observed between the preferred environment of cooperation and the general specificity of benefits of this cooperation. Therefore, for respondents, hypothesis H1 was valid. Statistically significant dependencies also existed between most of the analyzed specific benefits achieved through cooperation with offerors and (1) the preferred environment for this cooperation, and (2) the importance assigned to the benefits, taking into account their material or non-material nature. Thus, it can be said that, for respondents, hypothesis H2 was valid for seven benefits analyzed, and research hypothesis H3 was valid for nine benefits.

The age criterion included in the analysis made it possible to conclude that there was no statistically significant correlation between respondents’ age and their preferred environment of cooperation with offerors. This dependence was observed between age and (1) the general specificity of benefits preferred by respondents, and (2) twelve out of thirteen analyzed specific benefits of cooperation. Therefore, it can be concluded that for respondents, research hypothesis H4 was invalid. On the other hand, hypotheses H5 and H6 were valid (except for the benefit of ‘the possibility of checking the suitability of one’s ideas’). For the same twelve specific benefits of cooperation with offerors, hypothesis H7 also turned out to be valid.

7. Implications, Limitations, and Directions of Future Research

The results of the research and conclusions obtained based on the results contribute significantly to the theory of marketing and the theory of market behavior, especially when considered in the context of a decision-making process regarding cooperation between final purchasers and offerors. This allows a knowledge gap identified in the analysis of the global literature to be reduced. The results reflect respondents’ preferences regarding the environment of cooperation with offerors, contradicting the approach presented in literature, according to which the Internet is the only or the best environment for joint activities. It was discovered that respondents are looking for a kind of balance in this respect, appreciating the parallel use of the online and offline environments. It was also of a cognitive value to identify the hierarchy of benefits expected by the respondents that may become the share of final purchasers in cooperation with offerors, and to discover the dependences between the preferred environment of cooperation with offerors and the specificity of the expected benefits in general and in detail, taking into account purchasers’ age.

The results of this study are also characterized by high empirical value because they have important practical, especially managerial, implications. They make it possible to shape the environment of mutual cooperation in line with final purchasers’ expectations, taking into account the need for creating conditions to undertake joint activities both online and offline. In turn, identifying the benefits expected by the respondents enables managers to make the right decisions about composing such a set of incentives that will effectively stimulate active final purchasers to join marketing activities. The structure of the preferred benefits of cooperation recognized and the dependencies discovered are useful for managers representing any industry, regardless of the specificity of the products offered. These are also a valuable inspiration to shape mutually beneficial cooperation including for managers representing enterprises operating on the energy market, showing them what benefits are expected by final purchasers and what effects are not attractive enough for them to cooperate with offerors.

The research conducted in the present study has some limitations concerning the subject (the research covered only adults), the object (the research covered the preferred environment of cooperation between final purchasers and offerors and the benefits expected by final purchasers thanks to this cooperation), and the geographical aspect (the research covered representatives of final purchasers in Poland). Future research directions will therefore be defined to overcome these limitations. The analysis will also cover minors (persons under 18 years of age). Moreover, an attempt will be made to analyze in detail the preferred environment of cooperation with offerors and the benefits associated with this environment, according to demographic characteristics of final purchasers other than age. Of course, thanks to the application of panel-based research, the results of the future studies can be compared with the results currently obtained.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Dellaert, B.G.C. The consumer production journey: Marketing to consumers as co-producers in the sharing economy. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2018, 47, 238–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grubor, A.; Marić, D. Contemporary Consumer in the Global Environment. In Proceedings of the CBU International Conference on Innovation, Technology Transfer and Education, Prague, Czech Republic, 25–27 March 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D.; Sinarta, Y. Real-time co-creation and nowness service: Lessons from tourism and hospitality. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 563–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frieden, D.; Tuerk, A.; Roberts, J.; d’Herbemont, S.; Gubina, A. Collective Self-Consumption and Energy Communities: Over-view of Emerging Regulatory Approaches in Europe. June 2019. Available online: https://www.compile-project.eu/wp-content/uploads/COMPILE_Collective_self-consumption_EU_review_june_2019_FINAL-1.pdf (accessed on 28 May 2021).

- Roberts, J.; Frieden, D.; d’Herbemont, S. Energy Community Definitions, Compile Project: Integrating Community Power in Energy Islands. May 2019. Available online: https://www.compile-project.eu/wp-content/uploads/Explanatory-note-on-energy-community-definitions.pdf (accessed on 28 May 2021).

- De Morais, I.C.; Brito, E.P.Z.; Quintão, R.T. Productive Consumption Changing Market Dynamics: A Study in Brazilian DIY Cosmetics. Lat. Am. Bus. Rev. 2018, 19, 323–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valaskova, K.; Kramarova, K.; Bartosova, V. Multi Criteria Models Used in Slovak Consumer Market for Business Decision Making. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2015, 26, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotilainen, K.; Saari, U.A. Policy Influence on Consumers’ Evolution into Prosumers—Empirical Findings from an Exploratory Survey in Europe. Sustainability 2018, 10, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzel, M.; Sezen, B.; Alniacik, U. Drivers and consequences of customer participation into value co-creation: A field experiment. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2020. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziemba, E.W.; Eisenbardt, M.; Mullins, R.; Dettmer, S. Prosumers’ Engagement in Business Process Innovation—The Case of Poland and the UK. Interdiscip. J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. 2019, 14, 119–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltramo, A. Active Consumers at the Centre of the Energy System: Towards Modelling Consumer Behaviour in OSeMOSYS. Available online: http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:970636/FULLTEXT01.pdf (accessed on 14 June 2021).

- Immonen, A.; Kiljander, J.; Aro, M. Consumer viewpoint on a new kind of energy market. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2020, 180, 106153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Lu, C.; Torres, E.; Chen, P.-J. Engaging customers in value co-creation or co-destruction online. J. Serv. Mark. 2018, 32, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, F.; Garcia-Perez, A.; Cillo, V.; Giacosa, E. A knowledge-based view of people and technology: Directions for a value co-creation-based learning organisation. J. Knowl. Manag. 2019, 23, 1314–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baruk, A.I. Co-creation of a food marketing offer by final purchasers in the context of their lifestyles. Br. Food J. 2020, 123, 1494–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandolfo, M.; Chen, S.; Noci, G. Co-creation in new product development: Which drivers of consumer participation? Int. J. Eng. Bus. Manag. 2020, 12, 1847979020913764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liljedal, K.T.; Dahlén, M. Consumers’ response to other consumers’ participation in new product development. J. Mark. Commun. 2015, 24, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martineau, E.; Arsel, Z. Managing Communities of Co-creation around Consumer Engagement Styles. J. Assoc. Consum. Res. 2017, 2, 179–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyyedamiri, N.; Tajrobehkar, L. Social content marketing, social media and product development process effectiveness in high-tech companies. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2019, 16, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, A.F.; Storbacka, K.; Frow, P. Managing the co-creation of value. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2007, 36, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Ramaswamy, V. The Future of Competition: Co-Creating Unique Value with Customers; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ramaswamy, V. Co-creation of value—Towards an expanded paradigm of value creation. Mark. Rev. St. Gallen 2009, 26, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, K.R.; Read, S. Value co-creation: Concept and measurement. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2014, 44, 290–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidi, F.; Gharneh, N.S.; Khajeheian, D. A Conceptual Framework for Value Co-Creation in Service Enterprises (Case of Tourism Agencies). Sustainability 2019, 12, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Bose, S.; Babu, M.M.; Dey, B.L.; Roy, S.; Binsardi, B. Value Co-Creation as a Dialectical Process: Study in Bangladesh and Indian Province of West Bengal. Inf. Syst. Front. 2019, 21, 527–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettiga, D.; Lamberti, L.; Noci, G. Investigating social motivations, opportunity and ability to participate in communities of virtual co-creation. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2017, 42, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neghina, C.; Bloemer, J.; Van Birgelen, M.; Caniëls, M.C. Consumer motives and willingness to co-create in professional and generic services. J. Serv. Manag. 2017, 28, 157–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Rana, N.P.; Dwivedi, Y.K. Assessing Consumers’ Co-production and Future Participation On Value Co-creation and Business Benefit: An F-P-C-B Model Perspective. Inf. Syst. Front. 2021, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Drennan, J.; Andrews, L.; Hollebeek, L.D. User experience sharing. Eur. J. Mark. 2018, 52, 1154–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendapudi, N.; Leone, R.P. Psychological Implications of Customer Participation in Co-Production. J. Mark. 2003, 67, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritzer, G. The “New” World of Prosumption: Evolution, “Return of the Same,” or Revolution? Sociol. Forum 2015, 30, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanella, A.; Bui, N.; Castellani, A.; Vangelista, L.; Zorzi, M. Internet of Things for Smart Cities. IEEE Internet Things J. 2014, 1, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozinets, R.; Patterson, A.; Ashman, R. Networks of Desire: How Technology Increases Our Passion to Consume. J. Consum. Res. 2016, 43, 659–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciasullo, M.V.; Troisi, O.; Cosimato, S. How Digital Platforms Can Trigger Cultural Value Co-Creation?—A Proposed Model. J. Serv. Sci. Manag. 2018, 11, 161–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Shen, L.; Chen, Y. A Study on Customer Prosumption Concept and Its Impact on Enterprise Value Co-Creation. Theor. Econ. Lett. 2017, 7, 2040–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sowa, I. Determinanty zróżnicowań zachowań prosumenckich młodych konsumentów. Studia Ekonomiczne 2015, 231, 120–138. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, S.; Saxena, T.; Purohit, N. The New Consumer Behaviour Paradigm amid COVID-19: Permanent or Transient? J. Health Manag. 2020, 22, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appel, G.; Grewal, L.; Hadi, R.; Stephen, A.T. The future of social media in marketing. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2019, 48, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayna, T.; Striukova, L. Involving Consumers: The Role of Digital Technologies in Promoting ‘Prosumption’ and User Innovation. J. Knowl. Econ. 2016, 12, 218–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciaszczyk, M.; Kocot, M. Behavior of Online Prosumers in Organic Product Market as Determinant of Sustainable Consumption. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettiga, D.; Ciccullo, F. Co-creation with customers and suppliers: An exploratory study. Bus. Process. Manag. J. 2018, 25, 250–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glenn, D. Determining Sample Size; University of Florida: Gainesville, FL, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Poland Population. Available online: https://countrymeters.info/en/Poland#population_2020 (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Sample Size Calculator. Available online: https://www.checkmarket.com/sample-size-calculator/ (accessed on 9 December 2020).

- Kleber, D.M.-S.; Volkova, T. Value Co-Creation Drivers and Components in Dynamic Markets. Mark. Brand. Res. 2017, 4, 249–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, A.; Kale, S.; Chandel, S.; Pal, D. Likert Scale: Explored and Explained. Br. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2015, 7, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, B.M.; Rosopa, P.J.; Minium, E.W. Statistical Reasoning in the Behavioral Sciences; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ostertagová, E.; Ostertag, O.; Kováč, J. Methodology and Application of the Kruskal-Wallis Test. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2014, 611, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Test ANOVA Kruskala-Wallisa. Available online: http://www.statystyka.az.pl/test-anova-kruskala-wallisa.php (accessed on 4 April 2021).

- Variance and Standard Deviation. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/edu/power-pouvoir/ch12/5214891-eng.htm (accessed on 25 September 2020).

- Wolny, R. The Development of Prosumption on the Polish e-services Market. Polityki Eur. Finans. Mark. 2019, 22, 238–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ives, C.D.; Abson, D.; Von Wehrden, H.; Dorninger, C.; Klaniecki, K.; Fischer, J. Reconnecting with nature for sustainability. Sustain. Sci. 2018, 13, 1389–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarino, J.; Font, X. Sustainability marketing myopia. J. Vacat. Mark. 2015, 21, 326–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieńkowski, D. Rethinking the concept of prosuming: A critical and integrative perspective. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 74, 101967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiteva, R.; Sovacool, B. Harnessing social innovation for energy justice: A business model perspective. Energy Policy 2017, 107, 631–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, S.B. The energy prosumer. Ecol. Law Q. 2016, 43, 519–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgiel, A.; Sowa, I. New consumer trends adoption by generations X and Y—Comparative analysis. Zeszyty Naukowe Szkoły Głównej Gospodarstwa Wiejskiego. Ekonomika i Organizacja Gospodarki Żywnościowej 2017, 117, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenbardt, M. The impact of incentives on prosumers knowledge sharing—The dimension of their characteristics. Bus. Inform. 2019, 2, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenbardt, M. Incentives as a Trigger for Consumer Knowledge Sharing with Enterprises and Public Sector Organizations. In Proceedings of the ECKM 2020 21st European Conference on Knowledge Management, Coventry, UK, 2–4 December 2020; p. 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).