How Visual and Mental Human-Likeness of Virtual Influencers Affects Customer–Brand Relationship on E-Commerce Platform

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Influencer Endorsement

2.2. Development and Application of Virtual Influencers

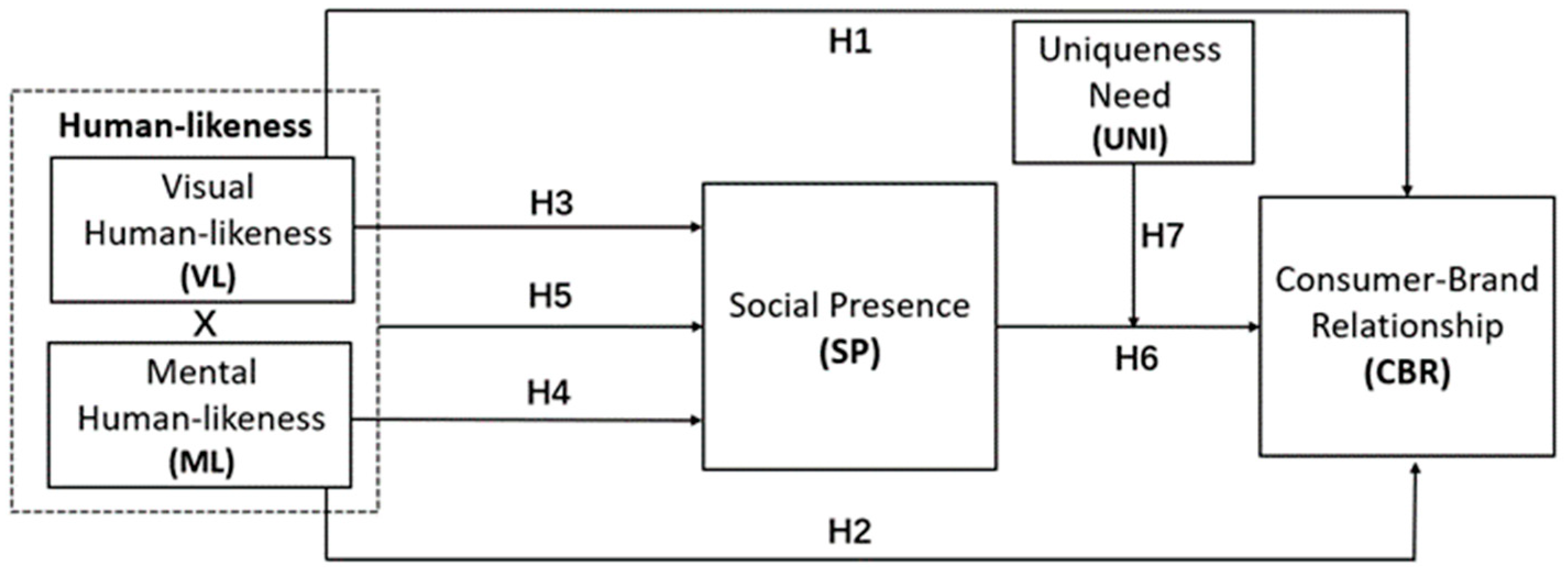

3. Theory

3.1. Consumer–Brand Relationship

3.2. Social Presence

3.3. Need for Uniqueness

4. Research Method

4.1. Data Collection

4.2. Measurement

4.3. Data Analysis

5. Result

5.1. Measurement Model Evaluation

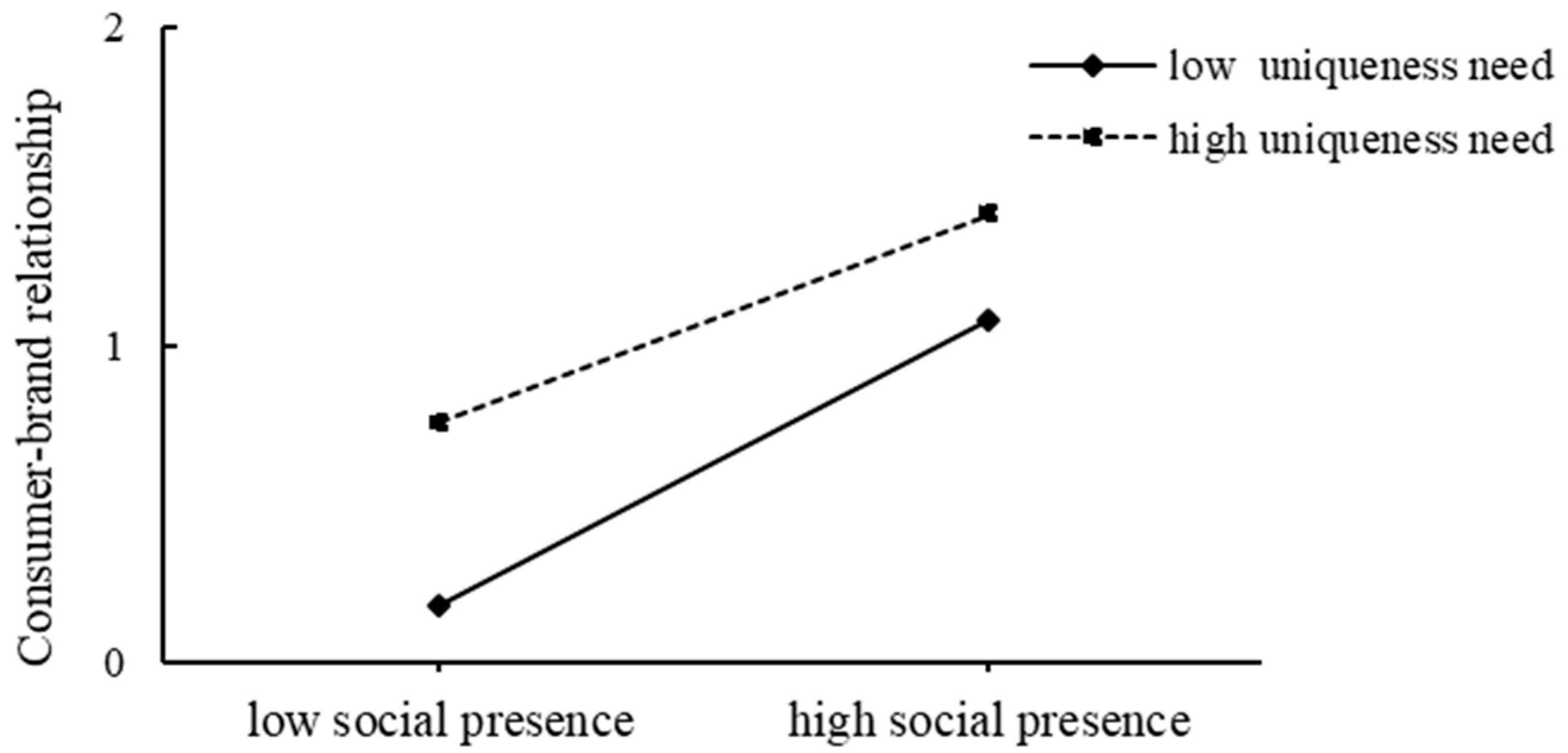

5.2. Structural Model Evaluation

6. Discussion

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Practical Implications

7. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Measurement Scales

References

- López, M.; Sicilia, M.; Verlegh, P.W.J. How to Motivate Opinion Leaders to Spread E-WoM on Social Media: Monetary vs Non-Monetary Incentives. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2022, 16, 154–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geyser, W. The State of Influencer Marketing 2023: Benchmark Report. Available online: https://influencermarketinghub.com/influencer-marketing-benchmark-report/ (accessed on 17 November 2024).

- Sands, S.; Campbell, C.L.; Plangger, K.; Ferraro, C. Unreal Influence: Leveraging AI in Influencer Marketing. Eur. J. Mark. 2022, 56, 1721–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Leszkiewicz, A.; Kumar, V.; Bijmolt, T.; Potapov, D. Digital Analytics: Modeling for Insights and New Methods. J. Interact. Mark. 2020, 51, 26–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Wang, L.; Li, X. To Collaborate or Serve? Effects of Anthropomorphized Brand Roles and Implicit Theories on Consumer Responses. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2019, 61, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.-C.; MacDorman, K.F. Measuring the Uncanny Valley Effect. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2016, 9, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDorman, K.F.; Green, R.D.; Ho, C.-C.; Koch, C.T. Too Real for Comfort? Uncanny Responses to Computer Generated Faces. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2009, 25, 695–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vuong, Q.-H.; La, V.-P.; Nguyen, M.-H.; Jin, R.; La, M.-K.; Le, T.-T. AI’s Humanoid Appearance Can Affect Human Perceptions of Its Emotional Capability: Evidence from a U.S. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2024, 40, 4906–4917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appel, M.; Izydorczyk, D.; Weber, S.; Mara, M.; Lischetzke, T. The Uncanny of Mind in a Machine: Humanoid Robots as Tools, Agents, and Experiencers. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 102, 274–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, J.-P.; Ohler, P. Venturing into the Uncanny Valley of Mind—The Influence of Mind Attribution on the Acceptance of Human-like Characters in a Virtual Reality Setting. Cognition 2017, 160, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, V.L.; Fowler, K. Close Encounters of the AI Kind: Use of AI Influencers As Brand Endorsers. J. Advert. 2020, 50, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baklanov, N. The Top Instagram Virtual Influencers in 2019. Available online: https://hypeauditor.com/blog/the-top-instagram-virtual-influencers-in-2019/ (accessed on 18 November 2024).

- Minton, M. Balmain Drops the Kardashians in Favor of CGI Models. Available online: https://pagesix.com/2018/08/30/balmain-drops-the-kardashians-in-favor-of-cgi-models/ (accessed on 18 November 2024).

- Arsenyan, J.; Mirowska, A. Almost Human? A Comparative Case Study on the Social Media Presence of Virtual Influencers. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2021, 155, 102694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kang, S.; Bae, J. Human Likeness and Attachment Effect on the Perceived Interactivity of AI Speakers. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 144, 797–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Veirman, M.; Cauberghe, V.; Hudders, L. Marketing through Instagram Influencers: The Impact of Number of Followers and Product Divergence on Brand Attitude. Int. J. Advert. 2017, 36, 798–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.Y.; Kim, H.-Y. Influencer Advertising on Social Media: The Multiple Inference Model on Influencer-Product Congruence and Sponsorship Disclosure. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 130, 405–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, J.-P.; Linda Breves, P.; Anders, N. Parasocial Interactions with Real and Virtual Influencers: The Role of Perceived Similarity and Human-Likeness. New Media Soc. 2022, 26, 3433–3453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.L. Conceptualizing, Measuring, and Managing Customer-Based Brand Equity. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkin, C.; Block, M. Effectiveness of Celebrity Endorsers. J. Advert. Res. 1983, 23, 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, K.E. Social Butterflies: How Social Media Influencers Are the New Celebrity Endorsement. Master’s Thesis, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Schouten, A.P.; Janssen, L.; Verspaget, M. Celebrity vs. Influencer Endorsements in Advertising: The Role of Identification, Credibility, and Product-Endorser Fit. Int. J. Advert. 2019, 39, 258–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, C.; Grimm, P.E. The Challenges Native Advertising Poses: Exploring Potential Federal Trade Commission Responses and Identifying Research Needs. J. Public Policy Mark. 2018, 38, 110–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breves, P.L.; Liebers, N.; Abt, M.; Kunze, A. The Perceived Fit between Instagram Influencers and the Endorsed Brand. J. Advert. Res. 2019, 59, 440–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergkvist, L.; Zhou, K.Q. Celebrity Endorsements: A Literature Review and Research Agenda. Int. J. Advert. 2016, 35, 642–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marwick, A.E. Instafame: Luxury Selfies in the Attention Economy. Public Cult. 2015, 27, 137–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, K.J.; Ahn, S.J. A Systematic Review of Virtual Influencers: Similarities and Differences between Human and Virtual Influencers in Interactive Advertising. J. Interact. Advert. 2023, 23, 293–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.-C.; Bruning, P.F.; Swarna, H. Using Online Opinion Leaders to Promote the Hedonic and Utilitarian Value of Products and Services. Bus. Horiz. 2018, 61, 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, C.; Kiew, S.T.J.; Chen, T.; Lee, T.Y.M.; Ong, J.E.C.; Phua, Z. Authentically Fake? How Consumers Respond to the Influence of Virtual Influencers. J. Advert. 2022, 52, 540–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djafarova, E.; Rushworth, C. Exploring the Credibility of Online Celebrities’ Instagram Profiles in Influencing the Purchase Decisions of Young Female Users. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 68, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, B.K.; Potocki, B.; Veldhuis, J. Is That My Friend or an Advert? The Effectiveness of Instagram Native Advertisements Posing as Social Posts. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 2019, 24, 108–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baylor, A.L. Promoting Motivation with Virtual Agents and Avatars: Role of Visual Presence and Appearance. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2009, 364, 3559–3565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamis, S.; Ang, L.; Welling, R. Self-Branding, ‘Micro-Celebrity’ and the Rise of Social Media Influencers. Celebr. Stud. 2016, 8, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.-C.; Swarna, H.; Bruning, P.F. Taking a Global View on Brand Post Popularity: Six Social Media Brand Post Practices for Global Markets. Bus. Horiz. 2017, 60, 621–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laszkiewicz, A.; Kalinska-Kula, M. Virtual Influencers as an Emerging Marketing Theory: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2023, 47, 2479–2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wejnert, B. Integrating Models of Diffusion of Innovations: A Conceptual Framework. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2002, 28, 297–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Cho, S.Y.; Jia, X.; Sun, R.; Tsai, W.S. Antecedents and Outcomes of Generation Z Consumers’ Contrastive and Assimilative Upward Comparisons with Social Media Influencers. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2023, 32, 1046–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Chen, H.; Kong, Q. An Expert with Whom i Can Identify: The Role of Narratives in Influencer Marketing. Int. J. Advert. 2020, 40, 972–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Wang, B.; Liu, Y.; Xi, N.; Zhu, D. How Should Social Media Influencers Tell Compelling Stories through Video Blogs? A Study of Storytelling Features on Live Comments. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2024. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaines, B.R. From Facilitating Interactivity to Managing Hyperconnectivity: 50 Years of Human–Computer Studies. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2019, 131, 4–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidin, C. Visibility Labour: Engaging with Influencers’ Fashion Brands and #OOTD Advertorial Campaigns on Instagram. Media Int. Aust. 2016, 161, 86–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlich, M. The Power of Virtual Influencers: Impact on Consumer Behaviour and Attitudes in the Age of AI. Adm. Sci. 2023, 13, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firmansyah, F. Strategies for Influencers to Enhance Consumer Loyalty in Virtual Marketplaces. J. Soc. Commer. 2023, 3, 188–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhawar, A.; Kumar, P.; Varshney, S. The Emergence of Virtual Influencers: A Shift in the Influencer Marketing Paradigm. Young Consum. 2023, 24, 468–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thellman, S.; Silvervarg, A.; Gulz, A.; Ziemke, T. Physical vs. Virtual Agent Embodiment and Effects on Social Interaction. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Proceedings of the Intelligent Virtual Agents 16th International Conference, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 20–23 September 2016; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 412–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkmans, C.; Kerkhof, P.; Buyukcan-Tetik, A.; Beukeboom, C.J. Online Conversation and Corporate Reputation: A Two-Wave Longitudinal Study on the Effects of Exposure to the Social Media Activities of a Highly Interactive Company. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 2015, 20, 632–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanus, M.D.; Fox, J. Persuasive Avatars: The Effects of Customizing a Virtual Salesperson׳s Appearance on Brand Liking and Purchase Intentions. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2015, 84, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.-J.; Lin, J.-S.; Choi, J.H.; Hahm, J.M. Would You Be My Friend? An Examination of Global Marketers’ Brand Personification Strategies in Social Media. J. Interact. Advert. 2015, 15, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, J.; Williams, E.; Christie, B. The Social Psychology of Telecommunications; Wiley: London, UK, 1976; ISBN 978-0-471-01581-9. [Google Scholar]

- Biocca, F.; Harms, C. Defining and Measuring Social Presence: Contribution to the Networked Minds Theory and Measure. Proc. Presence 2002, 2002, 7–36. [Google Scholar]

- Guadagno, R.E.; Blascovich, J.; Bailenson, J.N.; McCall, C.A. Virtual Humans and Persuasion: The Effects of Agency and Behavioral Realism. Media Psychol. 2007, 10, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, C.S.; Bailenson, J.N.; Welch, G.F. A Systematic Review of Social Presence: Definition, Antecedents, and Implications. Front. Robot. AI 2018, 5, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, S. Consumers and Their Brands: Developing Relationship Theory in Consumer Research. J. Consum. Res. 1998, 24, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, P. The Effects of Brand Relationship Norms on Consumer Attitudes and Behavior. J. Consum. Res. 2004, 31, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Sung, Y.; Moon, J.H. Effects of Brand Anthropomorphism on Consumer-Brand Relationships on Social Networking Site Fan Pages: The Mediating Role of Social Presence. Telemat. Inform. 2020, 51, 101406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, J.K.; McLelland, M.A.; Wallace, L.K. Brand Avatars: Impact of Social Interaction on Consumer–Brand Relationships. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2022, 16, 237–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsharnouby, M.H.; Jayawardhena, C.; Liu, H.; Elbedweihy, A.M. Strengthening Consumer–Brand Relationships through Avatars. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2023, 17, 581–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, E.S.; Sung, Y. Follow Me! Global Marketers’ Twitter Use. J. Interact. Advert. 2011, 12, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jham, V.; Malhotra, G.; Sehgal, N. Consumer-Brand Relationships with AI Anthropomorphic Assistant: Role of Product Usage Barrier, Psychological Distance and Trust. Int. Rev. Retail Distrib. Consum. Res. 2023, 33, 117–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, P.; McGill, A.L. Is That Car Smiling at Me? Schema Congruity as a Basis for Evaluating Anthropomorphized Products. J. Consum. Res. 2007, 34, 468–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattaraman, V.; Kwon, W.-S.; Gilbert, J.E.; Li, Y. Virtual Shopping Agents. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2014, 8, 144–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.C. The Impact of Anthropomorphism on Consumers’ Purchase Decision in Chatbot Commerce. J. Internet Commer. 2021, 20, 46–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, T.; Fuller, M.; Campbell, D. Designing Interfaces with Social Presence: Using Vividness and Extraversion to Create Social Recommendation Agents. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2009, 10, 889–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L.; Benbasat, I. Evaluating Anthropomorphic Product Recommendation Agents: A Social Relationship Perspective to Designing Information Systems. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2009, 25, 145–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purington, A.; Taft, J.G.; Sannon, S.; Bazarova, N.N.; Taylor, S.H. “Alexa is my new BFF”: Social Roles, User Satisfaction, and Personification of the Amazon Echo. In Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Denver, CO, USA, 6–11 May 2017; pp. 2853–2859. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, J.H.; Kim, E.; Choi, S.M.; Sung, Y. Keep the Social in Social Media: The Role of Social Interaction in Avatar-Based Virtual Shopping. J. Interact. Advert. 2013, 13, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argo, J.J.; Dahl, D.W.; Manchanda, R.V. The Influence of a Mere Social Presence in a Retail Context. J. Consum. Res. 2005, 32, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabiran, E.; Farivar, S.; Wang, F.; Grant, G. Virtually Human: Anthropomorphism in Virtual Influencer Marketing. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 79, 103797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cicco, R.; Iacobucci, S.; Cannito, L.; Onesti, G.; Ceccato, I.; Palumbo, R. Virtual vs. Human Influencer: Effects on Users’ Perceptions and Brand Outcomes. Technol. Soc. 2024, 77, 102488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, K.T.; Bearden, W.O.; Hunter, G.L. Consumers’ Need for Uniqueness: Scale Development and Validation. J. Consum. Res. 2001, 28, 50–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, R.; Sharma, P. Scarcity Appeal in Advertising: Exploring the Moderating Roles of Need for Uniqueness and Message Framing. J. Advert. 2015, 44, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheema, A.; Kaikati, A.M. The Effect of Need for Uniqueness on Word of Mouth. J. Mark. Res. 2010, 47, 553–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Ma, X.; Xu, X.; Liu, Y. Treat for Affection? Customers’ Differentiated Responses to pro-Customer Deviance. Tour. Manag. 2022, 93, 104619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Ju, D.; Yam, K.C.; Liu, S.; Qin, X.; Tian, G. Employee Humor Can Shield Them from Abusive Supervision. J. Bus. Ethics 2022, 186, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Yang, X.; Swanson, S.R. The Impact of Spatial-Temporal Variation on Tourist Destination Resident Quality of Life. Tour. Manag. 2022, 93, 104572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zibrek, K.; McDonnell, R. Social Presence and Place Illusion Are Affected by Photorealism in Embodied VR. In Proceedings of the 12th ACM SIGGRAPH Conference on Motion, Interaction and Games, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 28–30 October 2019; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Algesheimer, R.; Wangenheim, F.v. A Network Based Approach to Customer Equity Management. J. Relatsh. Mark. 2006, 5, 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C. Googlish as a Resource for Networked Multilingualism. World Englishes 2019, 39, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, G.; Hesse, E.; Dottori, M.; Birba, A.; Amoruso, L.; Martorell Caro, M.; Ibáñez, A.; García, A.M. The Bilingual Lexicon, Back and Forth: Electrophysiological Signatures of Translation Asymmetry. Neuroscience 2022, 481, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Matthews, L.M.; Matthews, R.L.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: Updated Guidelines on Which Method to Use. Int. J. Multivar. Data Anal. 2017, 1, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2010; ISBN 978-0-13-515309-3. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, F.; Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Ryu, K. An Assessment of the Use of Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) in Hospitality Research. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 514–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wold, H. Soft modelling: The basic design and some extensions. In Systems Under Indirect Observations: Part II; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1982; pp. 36–37. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller, C.M.; Simmering, M.J.; Atinc, G.; Atinc, Y.; Babin, B.J. Common Methods Variance Detection in Business Research. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3192–3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. Common Method Bias in PLS-SEM: A Full Collinearity Assessment Approach. Int. J. E-Collab. 2015, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acikgoz, F.; Vega, R.P. The Role of Privacy Cynicism in Consumer Habits with Voice Assistants: A Technology Acceptance Model Perspective. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2021, 38, 1138–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Testing Measurement Invariance of Composites Using Partial Least Squares. Int. Mark. Rev. 2016, 33, 405–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, S.-C.; Deng, T.; Mundel, J. The Impact of Personalization on Viral Behavior Intentions on TikTok: The Role of Perceived Creativity, Authenticity, and Need for Uniqueness. J. Mark. Commun. 2022, 30, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashley, C.; Tuten, T. Creative Strategies in Social Media Marketing: An Exploratory Study of Branded Social Content and Consumer Engagement. Psychol. Mark. 2014, 32, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringler, C.; Sirianni, N.J.; Peck, J.; Gustafsson, A. Does Your Demonstration Tell the Whole Story? How a Process Mindset and Social Presence Impact the Effectiveness of Product Demonstrations. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2023, 52, 512–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Park, M. When Digital Celebrity Talks to You: How Human-like Virtual Influencers Satisfy Consumer’s Experience through Social Presence on Social Media Endorsements. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 76, 103581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audrezet, A.; Koles, B. Virtual Influencer as a Brand Avatar in Interactive Marketing. In The Palgrave Handbook of Interactive Marketing; Wang, C.L., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 353–376. ISBN 978-3-031-14961-0. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, R.E.; Lee, S.Y. “You Are a Virtual Influencer!”: Understanding the Impact of Origin Disclosure and Emotional Narratives on Parasocial Relationships and Virtual Influencer Credibility. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2023, 148, 107897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, M.; MacDorman, K.F.; Kageki, N. The Uncanny Valley [From the Field]. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 2012, 19, 98–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritvo, S.E.; Allison, R.S. Designing for the Exceptional User: Nonhuman Animal-Computer Interaction (ACI). Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 70, 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuetzler, R.M.; Grimes, G.M.; Scott Giboney, J. The Impact of Chatbot Conversational Skill on Engagement and Perceived Humanness. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2020, 37, 875–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Frequency Counts | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 337 | 32.373 |

| Female | 704 | 67.627 | |

| Education | High school and below | 17 | 1.633 |

| College degree | 70 | 6.725 | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 786 | 75.504 | |

| Postgraduate or above | 168 | 16.138 | |

| Age | 17–28 | 441 | 42.363 |

| 29–50 | 559 | 53.699 | |

| >50 | 31 | 2.978 | |

| How long have you followed the virtual influencer? | <0.5 year | 118 | 11.335 |

| 0.5 year–1 year | 350 | 33.622 | |

| 1 year–1.5 years | 281 | 26.993 | |

| 1.5 years–2 years | 182 | 17.483 | |

| >2 years | 110 | 10.567 |

| Constructs | Factor Loadings | Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visual Human-Likeness | 1. VL1 | 0.764 | 0.892 | 0.897 | 0.650 |

| 2. VL2 | 0.848 | ||||

| 3. VL3 | 0.839 | ||||

| 4. VL4 | 0.839 | ||||

| 5. VL5 | 0.781 | ||||

| 6. VL6 | 0.759 | ||||

| Mental Human-Likeness | 1. ML1 | 0.758 | 0.904 | 0.926 | 0.675 |

| 2. ML2 | 0.840 | ||||

| 3. ML3 | 0.831 | ||||

| 4. ML4 | 0.832 | ||||

| 5. ML5 | 0.845 | ||||

| 6. ML6 | 0.822 | ||||

| Social Presence | 1. SP1 | 0.847 | 0.773 | 0.869 | 0.689 |

| 2. SP2 | 0.855 | ||||

| 3. SP4 | 0.787 | ||||

| Consumer–Brand Relationship | 1. CBR1 | 0.854 | 0.803 | 0.884 | 0.717 |

| 2. CBR2 | 0.833 | ||||

| 3. CBR3 | 0.852 | ||||

| Need for Uniqueness | 1. UNI1 | 0.880 | 0.863 | 0.904 | 0.703 |

| 2. UNI2 | 0.858 | ||||

| 3. UNI3 | 0.813 | ||||

| 4. UNI4 | 0.800 |

| CBR | ML | SP | UNI | VL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBR | 0.847 | ||||

| ML | 0.407 | 0.822 | |||

| SP | 0.533 | 0.561 | 0.830 | ||

| UNI | 0.482 | 0.133 | 0.363 | 0.838 | |

| VL | 0.343 | 0.626 | 0.383 | 0.128 | 0.806 |

| Hypotheses | Beta | T values | p Values | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | VL → CBR | 0.101 | 2.325 | 0.020 | Supported |

| H2 | ML → CBR | 0.158 | 2.926 | 0.004 | Supported |

| H3 | VL → SP | 0.100 | 2.231 | 0.026 | Supported |

| H4 | ML → SP | 0.621 | 11.299 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H5 | VL*ML → SP | 0.095 | 2.958 | 0.003 | Supported |

| H6 | SP → CBR | 0.254 | 6.106 | 0.000 | Supported |

| VL → SP → CBR | 0.025 | 2.006 | 0.045 | ||

| ML → SP → CBR | 0.158 | 5.046 | 0.000 | ||

| VL*ML → SP → CBR | 0.024 | 2.308 | 0.021 | ||

| H7 | UNI*SP → CBR | −0.113 | 3.126 | 0.002 | Supported |

| R2 SP = 0.337 | |||||

| R2 CBR = 0.432 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, L.; Mo, L.; Sun, X.; Zhou, Z.; Ren, J. How Visual and Mental Human-Likeness of Virtual Influencers Affects Customer–Brand Relationship on E-Commerce Platform. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 200. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20030200

Zhang L, Mo L, Sun X, Zhou Z, Ren J. How Visual and Mental Human-Likeness of Virtual Influencers Affects Customer–Brand Relationship on E-Commerce Platform. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research. 2025; 20(3):200. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20030200

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Liangbo, Linlin Mo, Xiaohui Sun, Zhimin Zhou, and Jifan Ren. 2025. "How Visual and Mental Human-Likeness of Virtual Influencers Affects Customer–Brand Relationship on E-Commerce Platform" Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 20, no. 3: 200. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20030200

APA StyleZhang, L., Mo, L., Sun, X., Zhou, Z., & Ren, J. (2025). How Visual and Mental Human-Likeness of Virtual Influencers Affects Customer–Brand Relationship on E-Commerce Platform. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 20(3), 200. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20030200