1. Introduction

In the platform economy, many platform firms are shifting from a product-centric to a service-centric business [

1]. For example, IBM has transformed from a hardware manufacturer into a service provider, with 55% of its revenue now coming from IT services. The diversification of value-added services plays a key role in helping platforms expand their markets, and the freemium model has become a widely adopted business strategy. Freemium refers to the practice of offering basic products or services for free to attract users, while generating revenue by offering high-quality value-added services [

2,

3]. These premium services offer enhanced functionalities, such as membership privileges on video platforms or in-game progression items, to better meet customer needs [

4]. For instance, IQIYI and Tencent Video, which are popular in Chinese online video software, provide free video resources as well as paid services. Subscribers can enjoy features such as ad-free viewing, early access to shows, exclusive content, and high-definition playback [

5]. Moreover, the freemium model rapidly attracts customer groups using the unique business logic of ’free + paid’. Over time, this approach strengthens platforms’ revenue streams and market competitiveness. In 2023, Tencent reported revenues of USD 41.1 billion in the freemium category, and the number of value-added service members reached 250 million, including 117 million video service members and 107 million music value-added service members. At the end of the same year, Netflix had 260 million subscribers and generated USD 33.7 billion in revenue. These examples demonstrate that the freemium model is rapidly gaining global prominence in the digital economy. Therefore, the operation and management of freemium platforms have important practical research value.

Platforms with the freemium model typically maintain a long-term presence in the market, adopting different strategies at various stages to sustain growth and profitability [

6]. During the normal sales period, they provide basic products and value-added services to meet the fundamental needs of customers. This helps to gradually build a stable user base and increase customer reliance on the platform [

2]. Once the customer base becomes stable, the platform enters the marketing period. At this stage, the focus shifts to adjusting product and service differences to increase the conversion of free users into paying customers [

7]. A common strategy during this period is to reduce the quality of the basic product to encourage customers to upgrade to higher-quality value-added services [

8]. This approach has been widely implemented in practice. For example, music streaming platforms such as Spotify and Apple Music limit audio quality and certain features in their free versions, thus incentivizing customers to upgrade to premium subscriptions. Additionally, platforms significantly improve the quality and customer experience of their value-added services during this phase, enhancing customers’ perceived value of the premium services [

9]. A case in point is IQIYI, which offers 4K ultra-high-definition video and exclusive high-rated content to attract customers to subscribe to its premium membership. These marketing strategies directly affect customers’ perceived utility, which in turn may influence their price sensitivity for value-added services. Consequently, selecting the right marketing strategy and setting dynamic prices for services during the two sales periods are critical for improving customer conversion and managing product and service operations effectively.

However, the operating environment of the freemium business model is significantly affected by the development of the digital economy. With easy access to information such as product quality and online reviews, customers’ purchasing decisions are influenced not only by network effects [

10,

11], but by psychological factors such as regret, curiosity, anchoring, and consumer stickiness [

12,

13,

14,

15]. Among these, consumer stickiness is a particularly important factor in studies of purchasing behavior. It refers to the ability of a product or brand to retain customers and keep them engaged [

16]. Stickiness reflects the customer’s sense of dependence, which is shaped by loyalty, trust, and positive experiences with the brand or product. The degree of consumer stickiness to value-added services changes with the quality of products and services, service prices, brand preferences, and other factors, thus affecting the perceived utility of consumers. For example, the high-quality content of IQIYI, the vast and popular resources of Tencent Video, and the clean, user-friendly interface of NetEase CloudMusic all help to enhance user stickiness to the respective platforms. Therefore, the long-term accumulated data resources of the platforms have commercial value as they contain rich information on demand. Thus, determining how best to analyze these resources to optimize product quality and pricing of value-added services is an urgent practical problem for freemium platforms.

In summary, consumer stickiness and service pricing are important factors affecting customer decisions [

17,

18]. An appropriate service marketing strategy can improve results, enabling platforms to achieve higher profits with greater efficiency. However, with freemium, both the quality of the basic product and value-added services greatly affect customer demand. These are the main contents of platform product design and service operations. Due to the presence of consumer stickiness, freemium platforms to optimize the quality levels of both their basic products and premium services. This paper explores these interactions, focusing on three research questions:

How should platforms set optimal pricing strategies for value-added services at different stages of the sales period, considering the influence of consumer stickiness?

How do the width (proportion) and depth (degree) of consumer stickiness affect optimal pricing, service demand, and platform profitability?

During the marketing period, which strategy best maximizes platform profit, and under what conditions should each strategy be implemented?

Accordingly, because consumer choices are affected by both the basic product quality and value-added service level, this study analyzes the effect of depth and width of consumer stickiness on service pricing, service demand, and platform profit among the marketing strategies: the level-improvement strategy for value-added services and the quality-reduction strategy for a basic product. The contributions of this study are as follows:

Considering depth and width of consumer stickiness, we reveal the mechanism by which customer heterogeneity affects the optimal pricing of value-added services.

We construct a two-stage multinomial logit (MNL) model that analyzes the dynamic pricing problem of value-added services for a freemium platform, with a normal sales period in the first stage and a marketing period in the second stage.

With regard to the level-improvement strategy for value-added services and quality-reduction strategy for a basic product, we analyze applicability conditions that affect the two marketing strategies. This compensates for the shortfall in the value-added services marketing strategy employed by platforms in freemium.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 is the literature review.

Section 3 provides problem descriptions. Theoretical analyses of different strategies are conducted in

Section 4. The results of numerical experiments are presented in

Section 5, the Expansion is presented in

Section 6, and the conclusions and recommendations are drawn in

Section 7.

2. Literature Review

The freemium model has recently drawn the attention of scholars worldwide. However, existing research has paid less attention to combining product quality and service level with consumer stickiness. Three streams of the literature relate to our study: product optimization of the value-added model, consumer characteristics, and service pricing and marketing strategies.

2.1. Product Optimization

Existing research shows that the freemium model may lead to a cannibalization effect [

19,

20], where the free version of a product competes with the paid version and suppresses its sales. To address this issue, product optimization has become a key focus in freemium model studies. Specifically, increasing the functionality gap and usage thresholds between the free and paid versions, as well as raising consumers’ switching costs, can effectively reduce internal competition [

21]. However, this cannibalization effect is more likely to occur in the early stages of product adoption. As the paid version matures, its complementary value may offset this effect [

22]. To enhance the effectiveness of the freemium model, Kato et al. [

8] consider customers’ tolerance for limited product usage and find that low tolerance pushes firms to reduce the usage limit of the free version. Incorporating advertising into the freemium framework, Li et al. [

6] show that differentiated content and advertising can both mitigate cannibalization and support user segmentation. However, overly intrusive advertisements may weaken the effectiveness of the freemium approach [

23].

In addition, scholars compare the benefits that free and paid versions bring to platforms and consumers, analyzing their respective characteristics [

24,

25,

26]. Their findings suggest that platforms should offer free versions when product quality is relatively low and customer aversion to advertising is minimal; otherwise, paid versions are more appropriate [

24,

25]. In the context of piracy threats, Wu et al. [

27] find that the freemium model is an effective strategy for deterring piracy and improving platform profitability. While these studies provide a valuable foundation for freemium model design, further research is needed to explore optimization strategies for both the quality of the free product and the level of premium services. In this context, the present study investigates how level improvement for value-added services and quality reduction for a basic product affect customer choice behavior in freemium platforms, and examines the conditions under which each strategy is more effective.

2.2. Consumer Characteristics and Stickiness

Customer purchase decisions are significantly influenced by behavioral characteristics, which in turn impact service pricing and the design of value-added offerings. These behavioral characteristics are shaped not only by external environmental factors but also by individual intrinsic traits [

28]. From an external perspective, factors such as competitive market conditions and marketing strategies play an important role in shaping customer decision-making processes [

6,

18,

29]. From an internal perspective, accurately identifying customers’ intrinsic behavioral traits at different stages of the product lifecycle is essential for platforms to optimize pricing strategies [

30]. When a new product enters the market, factors such as consumer uncertainty, network effects, and hassle costs affect their utility [

20,

31,

32]. Considering consumer uncertainty and network effects, Chen et al. [

31] suggest that the free version of products can reduce consumer uncertainty about the paid version of products and that considering network effects can improve platform profits. Hassle costs for consumers generally include transfer and learning costs. Accounting for learning costs, Dey et al. [

22] establish that free trial versions are necessary. Their findings indicate that suppliers should both extend trial periods and reduce paid version prices when consumers demonstrate low learning efficiency. When a product has been on the market for a long period, Harviainen et al. [

30] find that without considering user experience, poor content and overly aggressive monetization methods are the main reasons for the failure of the free + paid pricing model for products. Based on consumers’ value quality and heterogeneous taste for the positioning of a new product, Fainmesser et al. [

33] find that richer user-generated content positively affects consumer purchasing decisions.

Regarding customer stickiness, existing studies primarily employ empirical approaches to examine how customer characteristics and product attributes influence stickiness [

34,

35,

36]. For customer characteristics, So et al. [

36] propose that customer engagement has cross-lagged effects on stickiness over time; Rong et al. [

34] further suggest that proprietary resources play a key role in improving stickiness, while price has little direct impact. Customer behavior is crucial for product pricing and service design, and customer stickiness has attracted significant academic attention as an important behavioral factor. However, most existing studies focus on how customer traits or product attributes affect stickiness and offer limited theoretical analysis of how stickiness, in turn, influences pricing decisions. To address this gap, the present study incorporates consumer stickiness into a multinomial logit (MNL) model. It further explores how the width and depth of stickiness affect platform pricing and strategic choices for value-added services.

2.3. Services Pricing and Marketing Strategies

Under current product strategies, basic products fulfill customers’ primary needs, while well-designed and appropriately priced value-added services can significantly enhance customer stickiness and willingness to pay. Therefore, optimizing the pricing and marketing of value-added services is a key approach for platforms to improve competitiveness [

37]. In terms of value-added service pricing, existing studies develop pricing models for monopoly and competitive environments on various platforms, including media platforms [

38], gaming platforms [

39], and video platforms [

40], aiming to maximize platform revenue. For example, Amaldoss et al. [

38] compare uniform pricing with tiered pricing strategies and find that when customers derive high utility from multiple platforms, competitors may adopt differentiated pricing strategies; otherwise, they tend to implement similar pricing schemes. When evaluating the bundling of new digital product with subscription service, Zhang et al. [

41] identify two necessary conditions: low subscriber demand for the new product and a relatively high subscription price. Meanwhile, Mai et al. [

42] demonstrate that offering multiple tiers of premium subscription services is unwarranted in an advertising-saturated market.

Regarding marketing strategies, the qualities of products and services are important in shaping customer demand [

43]. High-quality offerings increase users’ perceived utility and willingness to pay, while low-quality products may cause demand to shift to alternatives [

44]. In the context of freemium models, Shi et al. [

45] demonstrate that designing differentiated network effects for high- and low-quality products can improve model effectiveness. In addition, Li et al. [

46] examine the role of free trials and show that offering complementary free content increases demand for paid services. Various monetization strategies are also used to promote value-added services, such as advertising-based models, pay-per-use pricing, and bundled pricing mechanisms [

47,

48]. For example, Lopez-Navarrete et al. [

47] analyze how advertising and pay-per-view schemes affect revenue allocation for online content providers. Incorporating data-driven marketing, Xing et al. [

49] incorporate fan preferences into service supply chain pricing. Their findings suggest that in data-driven marketing environments, platforms can enhance profitability by moderately raising service prices. Overall, existing studies emphasize the critical role of service pricing and offer a strong theoretical foundation for premium service marketing. Based on these studies, the research develops a two-phase dynamic pricing model for value-added services, covering both the normal sales period and the marketing period. It also provides appropriate service marketing strategies for freemium platforms.

In summary, existing research has primarily focused on product optimization of freemium, consumer characteristics, and stickiness, as well as service pricing and marketing strategies, and important research findings have been reported. However, the design and optimization of marketing strategies for value-added services under the freemium model have not been fully explored from the perspective of consumer stickiness. Moreover, digital developments have made consumer heterogeneity and diverse service marketing strategies important practical characteristics of the freemium model. Therefore, considering the heterogeneity of consumer stickiness for value-added services, this study adopts the MNL model to determine the optimal pricing of value-added services in a freemium model. In addition, we identify more effective marketing strategies based on maximum profit. To clearly state the contribution of this study compared to existing articles, we provide

Table 1 as follows.

3. Problem Descriptions

This study considers a monopoly platform that offers a basic product and

n value-added services

, which are independent of one another. Based on real-world consumption behavior, we assume that each consumer can purchase at most one type of service. Customers have three options for entering the market: (a) not to buy the base product and value-added services; (b) to use the base product only; and (c) to use the base product and buy a value-added service. Consumers who use only the basic product experience negative utility due to its limited functionality. Anyway, the market includes a proportion of sticky customers, among whom those with higher levels of stickiness show a stronger willingness to purchase value-added services [

51]. Customer preferences for value-added services are heterogeneous. Based on purchase frequency, i.e., purchase stickiness [

35], consumers can be categorized into two groups: sticky customers and non-sticky customers. Non-sticky customers are new users with no prior purchase experience, while sticky customers are repeat users. The degree of stickiness is determined by historical purchase frequency and may vary across individuals. To simplify the model, following Li et al. [

6] and Kato et al. [

8], this study treats sticky customers as a homogeneous group, using the average stickiness level within the group as a representative measure.

We develop a two-stage pricing model for value-added services. The first stage is the normal sales period, followed by a marketing period. To promote the sales of value-added services, two marketing strategies are considered: level improvement for value-added services and quality reduction for basic products. Since cost plays a key role in pricing decisions, the quality of the basic product and value-added services is used as a proxy for platform cost. A multinomial logit (MNL) model is used to capture customer choice behavior, incorporating both the depth and width of consumer stickiness to account for the influence of heterogeneous consumer characteristics on the dynamic pricing of value-added services.

Table 2 provides a summary of the notations used throughout this study.

4. Model Construction and Theoretical Analysis of Different Strategies

4.1. The First Stage: Normal Sales Period

The deterministic utility for customers choosing only the basic product is

. Here,

denotes the perceived utility of the basic product by customers, where

m is the quality of the basic product, and

is consumers’ valuation of the basic product, assumed to follow a uniform distribution over the interval [0, 1]. The term

represents the disutility associated with using only the basic product. This disutility mainly arises from negative user experiences, such as limited functionality in free content or non-skippable advertisements. The utility for consumers choosing both the basic product and service

i is

.

represents the overall perceived utility of customers for both the basic product and the value-added service

i, where

denotes the price consumers need to pay for the value-added service

i, and

indicates the degree of consumer stickiness,

indicates that users have consumer stickiness, and

indicates that users are fully rational. We can acquire distinct consumer choice probabilities by building the MNL mode [

53,

54]. The probability that customers do not use the basic product is

The probability that customers use only the basic product is

The probability that customers purchase service

i is

where

and

.

Considering the platform’s research and development (R&D) costs, the profit that can be obtained by the platform is

The maximum platform profit is

From (

2) and (

3), the price of value-added service i as

From (

4) and (

6), the profit of the platform is

Proposition 1.

In a normal sales period, the optimal prices and maximum demand for the value-added services as well as the maximum profit for the platform arewhere , Corollary 1.

With an increase in the depth of consumer stickiness, the maximum demand for value-added services is expected to increase, i.e., ; If , the optimal service prices will increase accordingly, i.e., , if .

Corollary 1 reveals how the depth of consumer stickiness affects the optimal prices and the maximum demand for value-added services. Notably, sticky consumers typically exhibit high usage frequency, low price sensitivity, and a strong aversion to the hassle of switching platforms. These factors increase their willingness to purchase value-added services.

When the price of value-added services exceeds a certain threshold, platforms can optimize revenue by raising prices. In this case, strong consumer stickiness reduces churn, and the marginal increase in revenue from higher prices outweighs the marginal loss from reduced demand. In contrast, if the price remains below the threshold, revenue may fall short of covering fixed costs, and the pricing strategy may fail to tap into the full spending potential of sticky users. Therefore, only when the price exceeds the threshold does the optimal price rise with increasing consumer stickiness. This mechanism helps explain why many video platforms continue to raise membership fees while still maintaining high user retention [

26]. Highly sticky consumers, due to their reliance on and behavioral loyalty to the platform, are more willing to pay for a premium service, thereby justifying and sustaining dynamic pricing strategies.

Corollary 2.

The maximum demand for value-added services increases with the sticky width of consumers, i.e., ; If , the optimal service prices will increase accordingly, i.e., , if .

Corollary 2 illustrates the influence mechanism of sticky width on optimal pricing and maximum demand for value-added services. Noticeably, as the market share of sticky consumers increases, the platform faces a lower risk of demand loss from price changes. This is due to the mitigating effect of customer stickiness, which allows the platform to set higher prices and capture greater consumer surplus. Therefore, it is essential for platforms to monitor the composition of their user base, especially the proportion of sticky users. When this proportion is high and the service prices have already exceeded the critical threshold, raising prices can better reflect the monetization potential of these users.

Based on Corollaries 1 and 2, it can be concluded that to stimulate demand for value-added services, platforms should adopt strategies to convert non-sticky users into sticky users and strengthen the degree of customer stickiness. This involves optimizing customer experience and usage pathways in product and service design. Strategies include enhancing service continuity, improving content quality, providing personalized recommendations, and fostering interactive experiences to reinforce habitual usage and platform dependence. Furthermore, platforms should implement mechanisms such as membership rewards and task-based incentives to extend user engagement time and increase repeat purchases. These efforts can gradually reduce users’ willingness to switch to competing services and strengthen long-term loyalty.

4.2. The Second Stage: Marketing Period

4.2.1. The Level-Improvement Strategy for Value-Added Services

As the platform enters the marketing period, it promotes the sales of value-added services by adjusting the quality difference between the product and value-added services, mitigating the cannibalization effect of free products on paid services. This section first considers increasing the level of value-added services, at which point the quality of the basic product remains unchanged. The deterministic utility from customers choosing only the basic product is

. The utility of consumers choosing to purchasing service

i is

.

is the incremental level of the value-added service

i, where the increase does not exceed the original service level (i.e.,

).

denotes the degree of customer stickiness, and

is the stickiness coefficient. Compared with the normal sales period, an increased level of value-added services leads to higher utility levels for sticky consumers regarding the value-added services, i.e.,

. The probability that customers do not use the basic product is

The probability of only using the basic product is

The probability of purchasing the service

i is

where

and

.

In this case, as the level of value-added services increases, the platform’s R&D costs for these services will increase. The profit obtained by the platform is

The maximum platform profit is

From (

9) and (

10), we obtain the price of the value-added service

i as

From (

11) and (

13), the platform profit is

Proposition 2.

In the level-improvement strategy for value-added services at the marketing period, the optimal prices and maximum demand for the value-added services, as well as the maximum profit for the platform, arewhere , . Corollary 3.

The maximum demand for value-added services increases with the incremental level of value-added services, i.e., ; If , the optimal service prices will increase accordingly, i.e., , if .

Corollary 3 illustrates the influence mechanism by which changes in the level of value-added services

affect the optimal service prices and maximum service demand. This finding highlights a positive relationship between service quality and consumer purchase intention [

50]. Higher service standards increase the perceived value of the offering, which enhances users’ willingness to pay and boosts conversion rates. However, improving value-added services often leads to higher costs in areas such as content production, technical infrastructure, and user management. Therefore, setting appropriate price increases is essential to maintain platform profitability [

20]. For example, IQIYI has positioned high-quality value-added services as a core competitive advantage, offering original content such as the

Light On and

Love series, and charges higher membership fees than many competitors. Despite this, the platform continues to attract a large subscriber base. This is largely due to its commitment to content innovation and consistent delivery of high-quality programming. The IQIYI case illustrates an effective strategy in which superior service quality drives user monetization and supports a premium pricing model.

Corollary 4.

The maximum demand for value-added services increases with the coefficient of sticky depth, i.e., ; If , the optimal service prices will increase accordingly, i.e., , if .

Corollary 4 illustrates the influence mechanism of the sticky depth coefficient on the optimal prices and maximum demand for value-added services. During the marketing period, an improvement in service quality not only enhances the user experience but also strengthens the user dependence on the platform. Sticky consumers, who use the platform more frequently and rely on it more heavily, are more sensitive to service quality and show a greater willingness to pay. As the proportion of sticky users grows, the overall demand for value-added services also increases. To maximize profit, the platform must adjust pricing to reflect users’ perceived value and account for the costs of improving services. For example, WPS Office offers basic functions for free to attract users, then gradually integrates high-frequency tools such as cloud storage, PDF conversion, and annotation features into its premium membership. By continuously improving its value-added services, the platform increases users’ willingness to pay and maintains strong market acceptance, even as membership fees increase.

4.2.2. The Quality-Reduction Strategy for the Basic Product

In this section, we investigate the effect of reducing the basic product quality on customers’ decision-making behavior under the constant level of value-added services. The deterministic utility from customers choosing only the basic product is

.

represents the reduction in the quality of the basic product, where the decrease does not exceed the original quality level (i.e.,

).

is the consumers’ aversion to the basic product. Compared with the normal sales period, a lower-quality basic product will make customers more averse to the basic product, i.e.,

. The utility of consumers choosing to purchase service

i is

.

is the degree of customer stickiness, where

is the stickiness coefficient. Compared with the normal sales period and the level-improvement strategy for value-added services, a decrease in the basic product quality leads to lower sticky utility for sticky consumers, i.e.,

. The probability that customers do not use the basic product is

The probability of only using the basic product is

The probability of purchasing service

i is

where

and

.

In this case, because of the decrease in the basic product quality, the platform’s R&D costs for the basic product will decrease. The profit obtained by the platform is

The maximum platform profit is

From (

16) and (

17), we obtain the price of service

i as

From (

18) and (

20), the profit of the platform is

Proposition 3.

In the quality-reduction strategy for the basic product at marketing period, the optimal prices and maximum demand for the value-added services as well as maximum platform profit for them arewhere , . Corollary 5.

The maximum profit of the platform increases with the basic product quality decreases, while the optimal prices and maximum demand for value-added services are not affected, i.e., ; ; .

Corollary 5 elucidates the mechanism through which the reduction in the quality of the basic product influences service pricing, customer demand, and platform profit. When the level of value-added services remains constant, adjustment to the quality of the basic product does not alter the intrinsic value of the value-added services. A moderate reduction in the quality of the basic product does not significantly lower consumers’ perceived value of the value-added services, nor does it significantly affect their willingness to pay or purchasing behavior. This is because, in the freemium model, the basic product primarily serves as a tool for attracting users or offering trial experiences, rather than being a core value source. In comparison, value-added services are the main revenue drivers and attract greater consumer attention due to their independent functionality and enhanced benefits.

From an operational perspective, lowering the quality of the basic product can reduce costs related to research, development, and maintenance. This improves resource allocation efficiency and expands profit margins, especially in cost-sensitive markets. When designing product portfolios, platforms should clearly define the roles of basic and premium services. By intentionally limiting the functional value of basic offerings and strengthening the differentiation from paid services [

45], platforms can guide users toward higher-value consumption and improve overall profitability without compromising user experience.

Corollary 6.

As the coefficient of emotional utility rises, the maximum demand for value-added services will increase, i.e., ; If , the optimal service prices will increase accordingly, i.e., , if .

Corollary 6 illustrates the influence mechanism of the coefficient of disgusting emotion

on the optimal prices and maximum demand. The findings reveal that during the marketing period, platforms may strategically reduce the quality of the basic product. As noted by Kato [

8], this approach lowers user satisfaction with the free tier and creates emotional dissonance among non-paying users. A higher value of the emotional utility coefficient indicates that consumers react more strongly to such negative experiences. Some users may choose to upgrade to paid subscriptions due to the reduced value of the free version, while others may discontinue usage in more severe cases.

To implement this strategy effectively, platforms must accurately assess users’ emotional reactions to changes in basic product quality and carefully manage the functional limits of the free product. This balance helps to avoid excessive user churn while encouraging migration to premium offerings. In addition, when consumers exhibit high emotional sensitivity, platforms can consider moderate price increases for value-added services to reflect their higher perceived value, thus supporting both revenue growth and customer segmentation goals.

Corollary 7.

The maximum demand for value-added services increases with the coefficient of sticky depth, i.e., ; If , the optimal service prices will increase accordingly, i.e., , if .

Corollary 7 illustrates how the sticky depth coefficient impacts optimal pricing and maximum demand. Noticeably, during the marketing period, strategically reducing the quality of the basic product can enhance the distinction between free and premium offerings, thereby encouraging customers to upgrade. However, this approach may also weaken the stickiness utility associated with the basic product, especially for habitual customers, who may perceive a decline in overall experience. In markets characterized by lower customer stickiness, platforms should consider implementing moderate price reductions for value-added services. This can help compensate for the perceived utility loss from the downgraded basic product, improve conversion rates, and enhance overall profitability.

5. Case Simulation Analysis

We construct a two-stage model for the freemium platform and analyze the optimal pricing, maximum demand, and maximum platform profit. Here, numerical analysis is used to illustrate how the optimal solutions vary with changes in the width and depth of consumer stickiness. We also compare the platform’s optimal marketing strategies under different conditions. In addition, due to the complexity of theoretical calculations, we analyze the impact of the sticky depth coefficient and the incremental level of value-added services on the maximum profit of the platform by simulation.

We select a comprehensive video platform, represented by Tencent Video, as the case study subjects. The platform offers free videos and functionally limited basic services, alongside premium content and fully featured value-added services. To increase the conversion of customers into paying members, the platform can adjust the quality of free and member-exclusive content, either by enhancing the level of value-added services or reducing the quality of basic service, thus widening the gap between free and premium offerings. Subsequently, the platform sets appropriate membership prices at different sales stages based on customer stickiness. Historical purchase frequency and membership duration are used to measure the width and depth of consumer stickiness, that is

[

35]. The sales volume and pricing of the value-added services, and app rating of the platform are adopted as indicators of overall quality between quality and service, and the service level, given that basic product quality is calculated as the overall quality minus the level of value-added service, we obtain

m accordingly. Customer review data on video content and functionality serve as a basis for estimating the customer evaluation coefficient

for the platform product and services. Based on operational data from video platforms and parameter settings from existing studies [

8,

52,

55], and considering the constraints of this model, where

are within [0, 1],

, and

, we standardize and define the relevant parameters as follows:

,

and

. Overall, the parameter settings are relatively close to the common assumptions and empirical patterns observed in the operation of mainstream video platforms, supporting the practical relevance and feasibility of the simulation.

5.1. Sensitivity Analysis

This subsection, respectively, analyzes the impact of changes to the sticky depth coefficient

and value-added service level

on platform profit during the marketing period. We consider a scenario where the platform offers one basic product and two homogeneous services, characterized by identical trends in service level, service pricing, and service demand. Based on the assumptions outlined in the problem description and the parameter value settings, we define the following conditions:

. The range of

is [0, 5], the range of

is (0, 1), and the range of

is (1, 5). The effects of these two types of changes on platform profits are visualized in

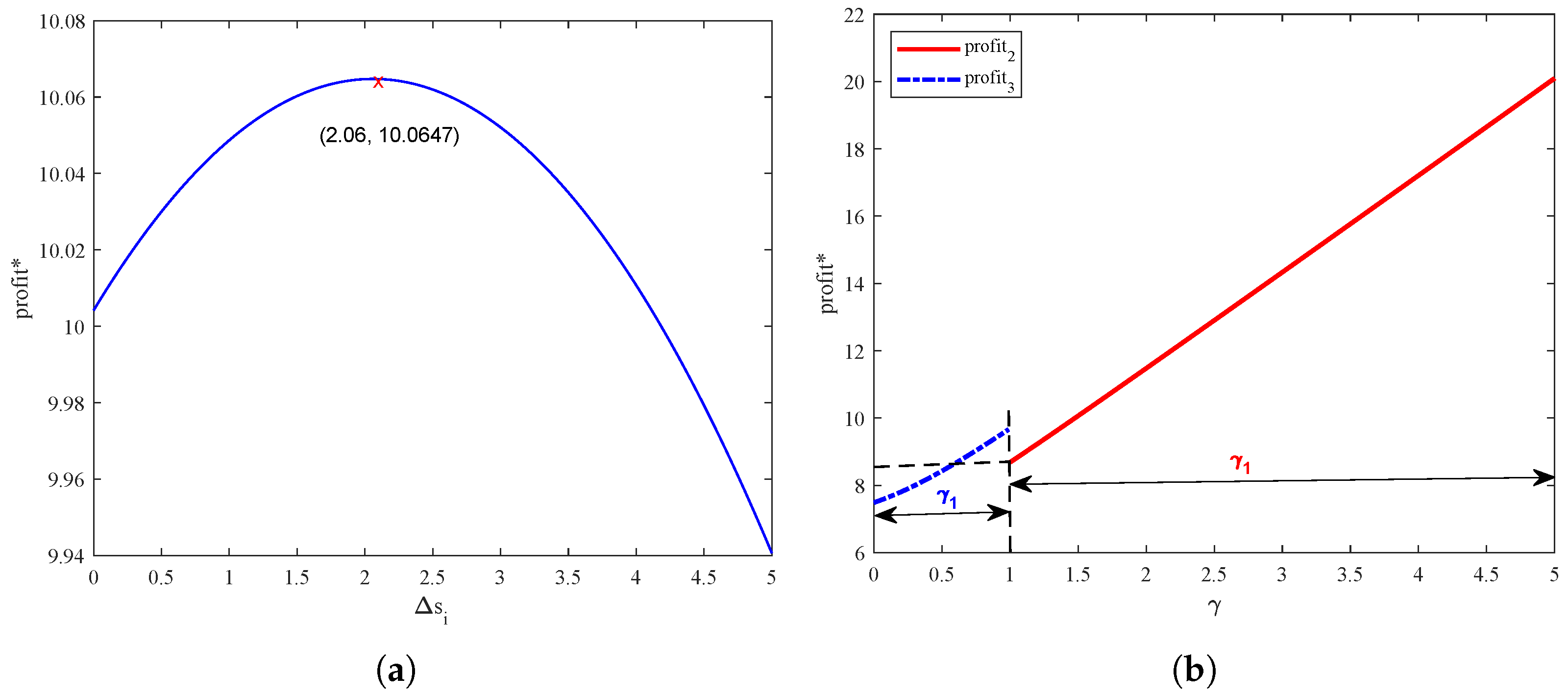

Figure 1.

Figure 1a shows that in the level-improvement strategy for value-added services, platform profit first increases and then decreases as the service level rises. When the increment is 2.06, the platform profit can reach the maximum. This is because the initial enhancement of value-added services significantly improves perceived service quality, thereby increasing membership conversion rate and boosting platform revenue. However, once the service level surpasses a certain threshold, marginal improvements yield diminishing returns in customer perception. At the same time, further service upgrades entail substantial costs in technology and content development, resulting in a decline in overall profitability. Noticeably, these findings highlight the existence of an optimal service level, suggesting that platforms cannot pursue unlimited service level improvements to achieve higher premium pricing. This finding contrasts with Rietveld’s conclusion [

50], which suggests that the freemium platform should create more value to maintain its core competitiveness. Our study finds that while moderate improvements in service quality can increase perceived value and support flexible pricing, excessive upgrades raise R&D and operational costs, leading to diminishing returns. For example, video platforms often attract members by offering exclusive series and original content. While these features enhance user engagement, acquiring premium content or producing original shows requires significant upfront investment. If subscriber growth fails to offset the rising costs, the additional revenue may not cover the increased marginal cost per user, limiting the profitability of continued service upgrades.

Figure 1b shows that the platform’s maximum profit increases with the sticky depth coefficient. Customers with a higher stickiness level are more likely to purchase value-added services, as these services offer greater perceived utility. Although both marketing strategies benefit from increased consumer stickiness, the mechanisms behind profit growth differ significantly. Under the level improvement for value-added services, profit rises almost linearly with the stickiness coefficient, and this growth exceeds that observed under the basic product quality reduction strategy. This indicates that enhancing service quality has a stronger potential to increase perceived value and support higher pricing, thereby driving greater profitability. For highly sticky customers, platforms should prioritize improving service features and offering exclusive content. These elements boost user-perceived value and increase their willingness to pay. In contrast, while the quality reduction for basic products may reduce short-term operational costs, its capacity for profit growth is limited. Overreliance on this approach can undermine long-term customer loyalty and erode brand equity.

5.2. Optimal Marketing Strategy Analysis for Value-Added Services

We examine how variations in consumers’ sticky depth and sticky width impact the optimal pricing, maximum demand, and maximum platform profit under both homogeneous and heterogeneous service scenarios. By comparing the optimal results of the two strategies, we identify the optimal marketing approach of the platform.

5.2.1. Homogeneous Services

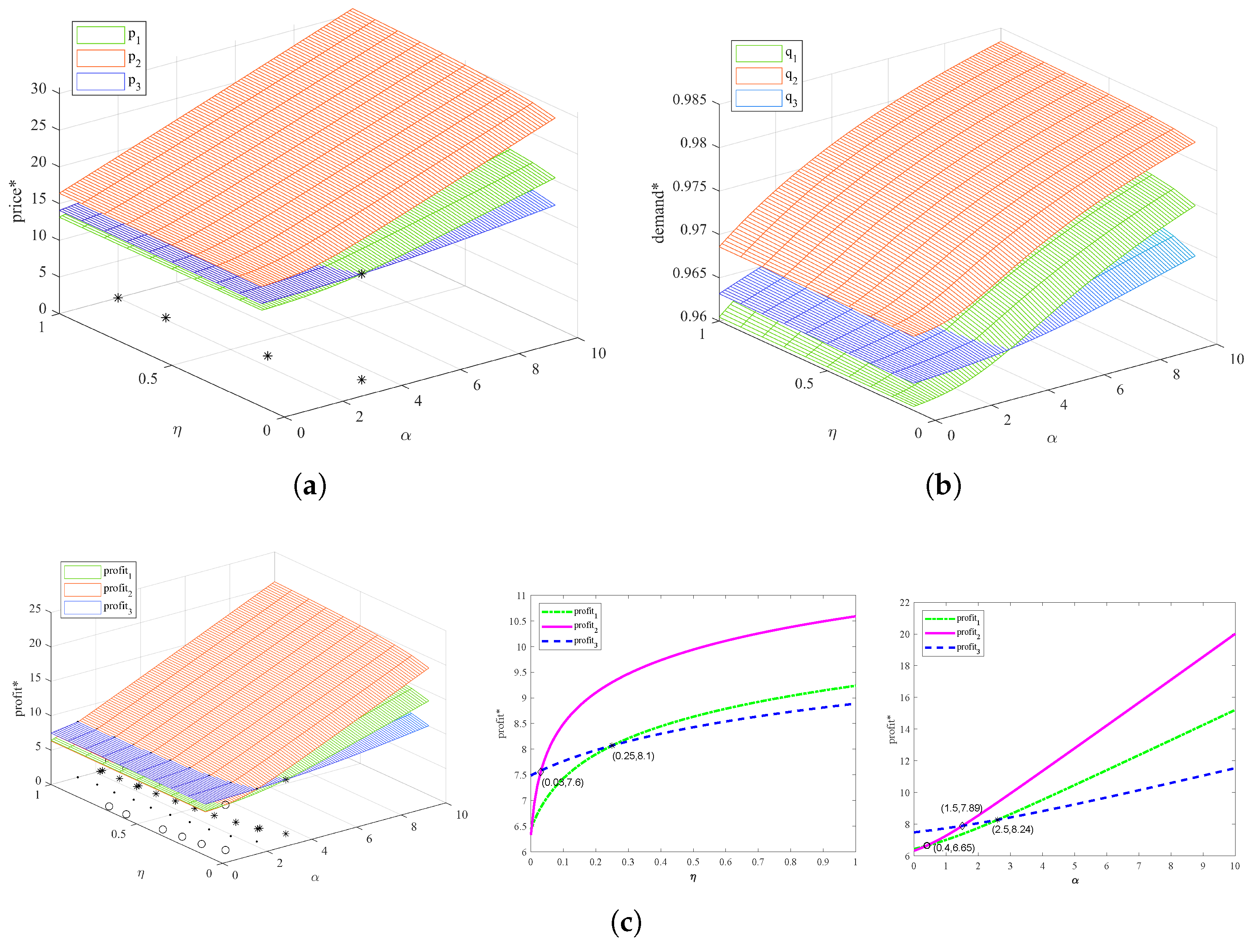

Combining the conditional assumptions in the problem descriptions and the range of parameters, we set

. The range of

is [0, 10], and the range of

is (0, 1]. The effects of sticky depth and width on the optimal service price, maximum demand, and maximum platform profit change under two sales periods, as visualized in

Figure 2.

Figure 2 shows that, in the context of homogeneous service levels, when the depth of consumer stickiness

and the width of sticky consumers

increase, the prices for value-added services, demand, and profit increase. With an increase in the depth of consumer stickiness, the platform profit growth rate is slower under the quality-reduction strategy for the basic product and faster under the level-improvement strategy for value-added services. This is because, under the level improvement for value-added services, consumers benefit from a more comprehensive and higher-quality service experience, resulting in substantially greater stickiness utility compared to scenarios where user conversion is driven primarily by reduced basic product quality. As the degree of consumer stickiness increases, this utility gap further widens, contributing to the difference in profit growth between the two strategies.

Figure 2 illustrates that consumer stickiness plays a critical role in determining the optimal marketing strategy. When stickiness is relatively low, consumers are less aware of the benefits of premium services and show limited willingness to pay. In this case, platforms, especially the video platforms, should adopt the quality reduction for the basic product to create a perceived limitation in the free tier, thereby encouraging users to try paid services. Value-added service prices should be set above those in the regular sales period but remain lower than prices under the level improvement for value-added services. As consumer stickiness increases, customers tend to develop a stronger reliance on platform content and services, becoming more willing to pay for enhanced experiences. At this stage, platforms should focus on enhancing value-added services by enriching content and improving member-exclusive features. This strategy strengthens user engagement and perceived value, allowing platforms to maintain demand even at higher price points. Accordingly, platforms should adjust pricing upward to reflect the increased perceived value and capture greater profitability.

5.2.2. Heterogeneous Services

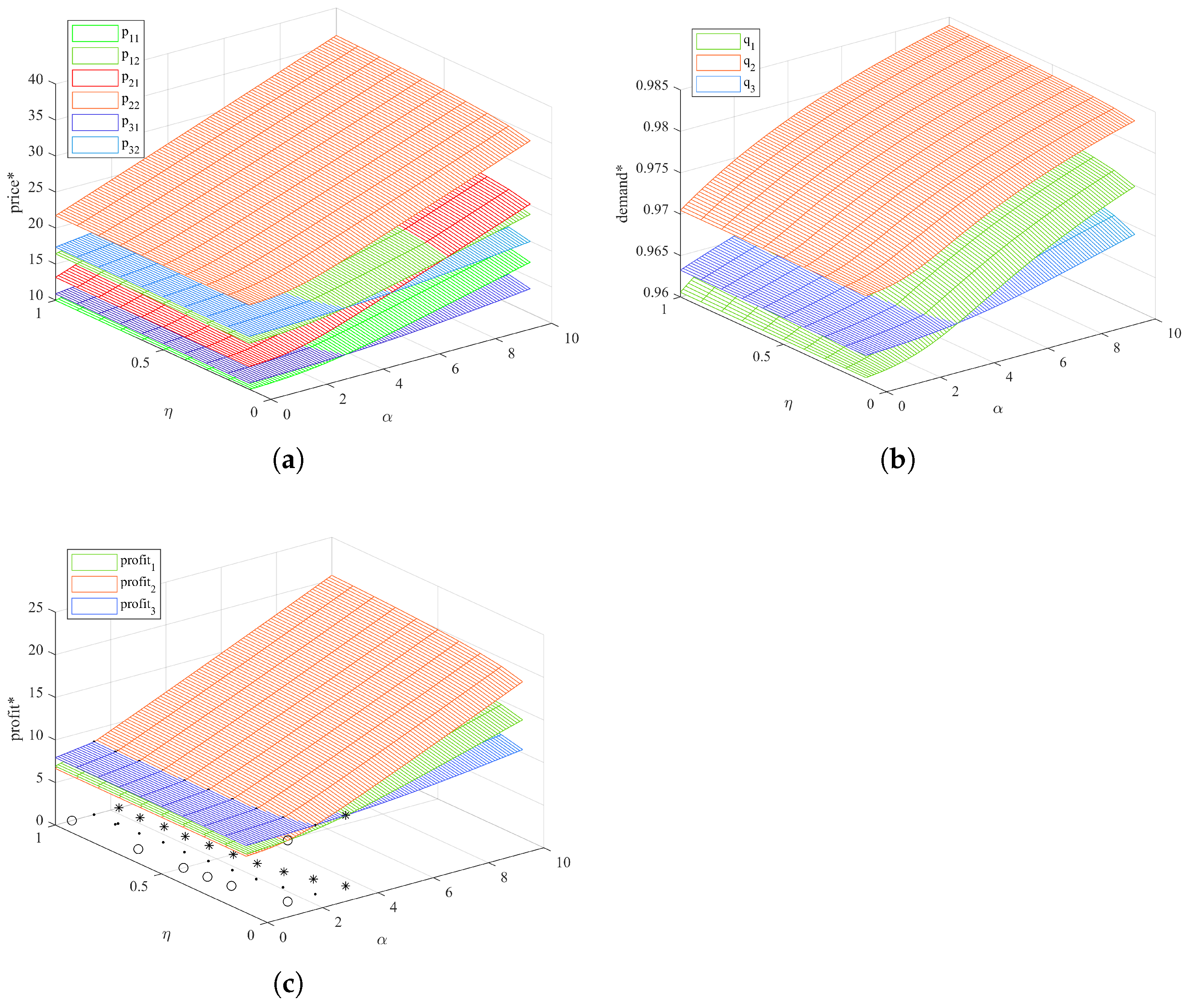

A basic product and two heterogeneous services are assumed herein. Combining the conditional assumptions in the problem descriptions and the range of parameters, we set

, and

. The range of

is [0, 10], and the range of

is (0, 1]. The effects of sticky depth and width on the optimal prices of the value-added services, maximum total demand for services, and maximum platform profit change under the different marketing strategies, as visualized in

Figure 3.

Figure 3 shows that, in the context of heterogeneous service levels, as the sticky depth

and the sticky width

increase, the optimal prices, maximum demand, and maximum profit increase accordingly. In the same strategy, higher prices should be set for high-quality value-added services. When the sticky depth is small, the service price under the quality-reduction strategy for the basic product should be lower than the price of the same service during the normal sales period. When the sticky depth is large, the service price during the marketing period is higher than the price of the same service during the normal sales period.

As illustrated in

Figure 3, when value-added services are heterogeneous, platforms, especially the video platforms, should adopt the quality reduction for the basic product when consumer stickiness is low. By moderately lowering the quality of free product, platforms can highlight their limitations and increase user interest in premium services. In this case, differentiated pricing should be used for the two premium service tiers, with prices set slightly above those in the regular sales period. This helps enhance perceived value, highlight service differences, and improve conversion rates. As consumer stickiness increases, platforms should transition toward the level improvement for value-added services. When stickiness reaches moderate levels, the price of lower-tier services should be positioned below that of higher-tier services during standard sales periods. This encourages non-sticky users to try paid services and gradually become more engaged. At high levels of stickiness, customers become increasingly sensitive to service quality rather than price. Even if both premium services are priced above standard levels, consumers remain willing to pay for enhanced experiences due to their strong platform dependence and perceived value.

5.3. Robustness of Profit

This section analyzes the robustness of optimal profit when there is an estimation error in customer stickiness. Without loss of generality, we consider the case of homogeneous consumers only. Suppose the platform estimates the customer stickiness parameter as , based on which the optimal price of the value-added service is , and the corresponding demand is . However, the actual customer stickiness parameter is , which leads to an actual demand of . If , then . Otherwise, . The actual profit of the platform is then given by .

In the case of homogeneous value-added services, assume only two products are developed. Define

as the profit loss due to the estimation error, where

represents the optimal profit under accurate estimation of stickiness.

Table 3 presents the results of platform profit and the corresponding loss under different estimation scenarios.

As shown in

Table 3, when there is a certain estimation error in the degree of customer stickiness, the profit demonstrates strong robustness. The maximum observed profit loss is 0.0061, all of which are below 0.01. Therefore, when the estimation error of customer stickiness remains within a reasonable range, the platform can still achieve near-optimal profit performance. This indicates that the proposed model exhibits good robustness.

6. Expansion

Incorporating customer stickiness characteristics, we classify consumers into two segments: sticky and non-sticky. While the baseline model considers a uniform pricing strategy for value-added services across all customers, this section extends the analysis to differential pricing tailored to these distinct segments. To manage model complexity, and without loss of generality, we treat sticky customers as a homogeneous group. We then derive the optimal pricing strategy for value-added services under heterogeneous customer conditions during the regular sales period.

The deterministic utility for customers choosing only the basic product is

. The utility for non-sticky consumers choosing both the basic product and service i is

. The utility for sticky consumers choosing both the basic product and service i is

.

indicates the prices of value-added services for non-sticky customers,

indicates the prices of value-added services for sticky customers. Assume the price ratio between sticky customers and non-sticky customers is

, such that

. The probability that customers do not use the basic product is

The probability that customers use only the basic product is

The probability that non-sticky customers purchase service

i is

The probability that sticky customers purchase service

i is

The maximum platform profit is

From (

23) and (

24), the price of value-added service i is

From (

23) and (

25), the profit of the platform is

Proposition 4.

The optimal prices and maximum demand for the value-added services as well as the maximum profit for the platform arewhere , Corollary 8. (1) ; when , , otherwise, . (2) . (3) when , .

Corollary 8 shows that under uniform pricing, the value-added service price is higher than the price for sticky customers under differential pricing. However, if the price ratio between sticky and non-sticky customers is sufficiently small, the uniform price may fall below the differential price for non-sticky customers; otherwise, it remains higher. This is because platforms tend to set relatively lower prices to retain sticky customers, who are less sensitive to price but more responsive to switching costs or exhibit higher loyalty. Under uniform pricing, the platform must adopt a moderately balanced price but not too low, thereby partially sacrificing the welfare of sticky customers to balance overall profitability and demand from non-sticky customers.

The relationship between the price of value-added services under uniform pricing and that for non-sticky customers under differential pricing is influenced by the price ratio between sticky and non-sticky customers. When the price for non-sticky customers is significantly higher than that for sticky customers, the platform leverages their higher monetization potential by charging a premium. In contrast, when the price for non-sticky customers is lower than that for sticky customers, the platform adopts a penetration pricing strategy to attract new users, resulting in non-sticky customers paying less than they would under a uniform pricing scheme.

It is worth noting that the maximum demand for value-added services under differential pricing is lower than that under uniform pricing. This is due to two reasons: (1) Under uniform pricing, the platform sets a moderate price for all customers, while differential pricing may impose higher prices on non-sticky customers, significantly reducing their demand and overall service uptake. (2) Differential pricing may create a perception of unfairness among customers, further suppressing demand. Therefore, platforms should implement differential pricing between sticky and non-sticky customers with strategic discretion. Contrary to intuition, by offering targeted purchase incentives or subsidies to sticky customers, the platform can better align pricing with customer characteristics and maximize revenue.

7. Conclusions and Recommendations

In the freemium model, considering the stickiness and heterogeneous characteristics of consumers, a two-stage pricing optimization model for value-added services is constructed for a monopoly platform. We consider the effect of product quality and service level on customer choice behavior. We analyze the optimal pricing and maximum demand for value-added services as well as the optimal platform profit in the normal sales period and the marketing period. Finally, the optimal marketing strategy selection for the service is depicted in the numerical simulation. The main conclusions are as follows:

(1) The optimal prices, maximum demand for value-added services, and platform profit will increase as the sticky depth and width of sticky consumers increase. As the sticky depth coefficient increases, the maximum demand, optimal prices, and platform profit will increase accordingly.

(2) When the level of value-added services increases while the quality of the basic product remains constant, the demand for and pricing of value-added services rise correspondingly. However, platform profit increases initially and then declines. In contrast, when the quality of the basic product is reduced while maintaining a consistent level of value-added services, the platform profit may steadily increase..

(3) Under the quality-reduction strategy for basic products, a higher coefficient of disgusting emotion results in greater demand and higher optimal prices for value-added services. Overall, when consumer stickiness is low, the quality-reduction strategy for the basic product is the more effective strategy. When stickiness is high, improving the level of value-added services becomes a better choice.

(4) Considering the pricing strategies of non-sticky and sticky customers, under uniform pricing, the value-added service price is higher than the price for sticky customers under differential pricing when both customer types are considered. However, if the price ratio between sticky and non-sticky customers is sufficiently small, the uniform price may fall below the differential price for non-sticky customers; otherwise, it remains higher.

Based on the above conclusions, the main recommendations are as follows:

(1) Increasing the sticky depth and the width of sticky consumers positively contributes to the growth of platforms. Platforms can build consumer stickiness by enhancing the consumer experience, establishing a unique brand image, and obtaining celebrity endorsements, all of which enhance consumer stickiness.

(2) Under the level-improvement strategy for value-added services, to attract consumers to purchase value-added services, platforms need to consider the cost of increasing the level of value-added services, and they should appropriately increase the service levels and prices. In the quality-reduction strategy for the basic product, platforms can reduce the quality of the basic product. They can both reduce capital investment in basic product R&D, and increase the quality difference between free products and paid services, thereby mitigating the impact of the cannibalization effect.

(3) Platforms can adopt the quality reduction for basic products to widen the gap in customer utility between the basic product and value-added services. This strategy increases customers’ aversion to the basic product and drives them to become paying customers.

(4) When developing marketing strategies, platforms should carefully analyze both the depth and width of consumer stickiness and set appropriate service prices to improve customer retention and conversion. In designing differentiated pricing strategies for sticky and non-sticky customer segments, it is recommended to offer sticky customers relatively lower prices for value-added services. This approach helps to strengthen their stickiness and enhance their service experience. In contrast, platforms can maintain higher price levels for non-sticky customers. By adopting a tiered pricing strategy that reflects differences in customer value, platforms can improve their ability to capture value from different segments and increase overall profitability.

This study has the following limitations: The effect of advertising on platform revenue and customers is not analyzed. Advertising can be profitable for platforms utilizing a freemium business model. In addition, we do not consider platform pricing optimization strategies in competitive situations. In the future, this study could be extended to analyze advertising strategies and pricing in competitive situations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.L. and B.Z.; methodology, W.Q. and B.Z.; formal analysis, B.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, B.Z.; writing—review and editing, X.L. and Z.L.; visualization, B.Z.; supervision, J.W.; funding acquisition, X.L. and W.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 72001071, in part by the National Social Science Foundation of China, grant number 24FGLB001, in part by the Philosophy and Social Sciences Planning Project of Henan Province in China, grant number 2022BJJ031, in part by the Program of Higher Education Philosophy and Social Sciences Innovative Talents of Henan Province in China, grant number 2024-CXRC-02, in part by the Postdoctoral Science Foundation of China, grant number 2024M750784, in part by the Planning Fund Project of Humanities and Social Sciences Research of the Ministry of Education of China, grant number 24YJA630069, in part by the Key Research and Promotion Project of Henan Province (Soft Science Research), grant number 252400411228, and in part by the Humanities and Social Sciences in Henan Provincial Colleges and Universities (General Category), grant number 2026-ZZJH-015.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

We use no data in this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MNL | Multinomial Logit model |

| VAS | Value-added services |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Proof of Proposition 1

The first derivative of the profit function with respect to the probability of consumers purchasing service

i is

The second derivative of the profit function with respect to the probability of consumers purchasing service

i is

From the second derivative of the profit function of the platform,

for all cases. The profit function is concave with respect to

, and the maximum market share can be obtained. Let

We obtain

Taking the exponent, with e as the base on both sides of the equation, one obtains

The above formula is expressed by the Lambert function:

Let

We have

From (

6) and (

A1), the optimal price of service

i is

From (

26), (

A1), and (

A2), the optimal profit of the platform is

Appendix A.2. Proof of Corollary 1

From (

A1), the first-order derivative of the maximum demand for value-added service

i with respect to the depth of consumer stickiness is

From (

A2), the first-order derivative of the optimal price for value-added service

i with respect to the depth of consumer stickiness is

Appendix A.3. Proof of Corollary 2

From (

A1), the first-order derivative of the maximum demand for value-added service

i with respect to the sticky width is

From (

A2), the first-order derivative of the optimal price for value-added service

i with respect to the sticky width is

Appendix A.4. Proof of Proposition 2

The first derivative of the profit function with respect to the probability of consumers purchasing service

i is

The second derivative of the profit function with respect to the probability of consumers purchasing service

i is

From the second derivative of the profit function of the platform, for all cases. The profit function is concave with respect to , and the maximum market share can be obtained. Let which follows the same process as in the proof of Proposition 1, so it is not repeated.

The maximum demand for value-added services is

where

From (

13) and (

A4), the optimal price of service

i is

From (

12), (

A4), and (

A5), the optimal profit of the platform is

Appendix A.5. Proof of Corollary 3

From (

A4), the first-order derivative of the maximum demand for value-added service

i with respect to change in the value-added service level is

From (

A5), the first-order derivative of the optimal price for value-added service

i with respect to change in the value-added service level is

Appendix A.6. Proof of Corollary 4

From (

A4), the first-order derivative of the maximum demand for value-added service

i with respect to the coefficient of sticky depth is

From (

A5), the first-order derivative of the optimal price for value-added service

i with respect to the coefficient of sticky depth is

Appendix A.7. Proof of Proposition 3

The first derivative of the profit function with respect to the probability of consumers purchasing service

i is

The second derivative of the profit function with respect to the probability of consumers purchasing service

i is

From the second derivative of the profit function of the platform, for all cases. The profit function is concave with respect to , and the maximum market share can be obtained. Let , following the same process as in the proof of Proposition 1, so it is not repeated.

The maximum demand for value-added services is

where

From (

20) and (

A7), the optimal price of service

i is

From (

19), (

A7), and (

A8), the optimal profit of the platform is

Appendix A.8. Proof of Corollary 5

From (

A7), the first-order derivative of the maximum demand for value-added service

i with respect to change in the basic product quality is

From (

A8), the first-order derivative of the maximum profit with respect to change in the basic product quality is

From (

A9), the first-order derivative of the maximum profit with respect to change in the basic product quality is

Appendix A.9. Proof of Corollary 6

From (

A7), the first-order derivative of the maximum demand for value-added service

i with respect to the coefficient of emotional utility is

From (

A8), the first-order derivative of the optimal price for value-added service

i with respect to the coefficient of emotional utility is

Appendix A.10. Proof of Corollary 7

From (

A7), the first-order derivative of the maximum demand for value-added service

i with respect to the coefficient of sticky depth is

From (

A8), the first-order derivative of the optimal price for value-added service

i with respect to the coefficient of sticky depth is

References

- Bustinza, O.F.; Vendrell-Herrero, F.; Davies, P.; Parry, G. Testing service infusion in manufacturing through machine learning techniques: Looking back and forward. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Man. 2024, 44, 127–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.H.; Chen, X.; Goes, P.; Zhang, C. Multiplex social influence in a freemium context: Evidence from online social games. Decis. Support Syst. 2022, 155, 113711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Z.X.; Hao, L.; Tan, Y. Freemium pricing in digital games with virtual currency. Inf. Syst. Res. 2021, 32, 481–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyrväinen, O.; Karjaluoto, H. Willingness to pay for freemium services: Addressing the differences between monetization strategies. Int. J. Inform. Manag. 2024, 77, 102787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Xia, H.; Ye, Q. The effect of advertising strategies on a short video platform: Evidence from TikTok. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2022, 122, 1956–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.Y.; Wu, J.; Zhang, J.Z.; Ji, X. Freemium design: Optimal tier differentiation models for content platforms. Transp. Res. Pt. e-Logist. Transp. Rev. 2024, 188, 103612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Lowry, P.B.; Luo, X.; Li, H. Moving consumers from free to fee in platform-based markets: An empirical study of multiplayer online battle arena games. Inf. Syst. Res. 2023, 34, 275–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, T.; Dumrongsiri, A. Designing freemium with usage limitation: When is it a viable strategy? Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2022, 53, 101153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.B.; Zhang, Y.J.; Dan, B.; Zhang, X.M.; Sui, R.H. Simulation modeling and analysis on the value-added service of the third-party e-commerce platform supporting multi-value chain collaboration. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 19, 846–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, L.J.; Li, S.D. Price and product innovation competition with network effects and consumers’ adaptive learning: A differential game approach. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2024, 193, 110298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Fan, L.J.; Tang, Y.Z.; Perera, S.C.; Wang, J.J. The value of blockchain for shipping platforms: A perspective from multi-homing and network effects. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2024, 63, 5452–5474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.L.; Li, Q.; Islam, N.; Han, C.J.; Gupta, S. Product attribute and heterogeneous sentiment analysis-based evaluation to support online personalized consumption decisions. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2024, 71, 11198–11211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, P.; Singh, J.; Wang, W.S. The influence of creative packaging design on customer motivation to process and purchase decisions. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 147, 338–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Qi, W.; Wang, J. Optimal pricing of online products based on customer anchoring-adjustment psychology. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2024, 31, 448–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.L.; Chung, H.F.L. Impact of delightful somatosensory augmented reality experience on online consumer stickiness intention. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2024, 18, 6–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Y.B.; Sarigöllü, E.; Lou, L.G.; Huang, B.T. How streamers foster consumer stickiness in live streaming sales. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2023, 18, 1196–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Yuan, H.; Ye, Q.W.; Qian, Y.; Ge, X.Y. Exploring the impacts of a recommendation system on an e-platform based on consumers’ online behavioral data. Inform. Manag. 2024, 61, 103905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heston, S.L.; Hu, B. Technical note: Dynamic duopolistic competition with sticky prices. Oper. Res. 2024, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhargava, H.K.; Choudhary, V. Research note—When is versioning optimal for information goods? Manag. Sci. 2008, 54, 1029–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.K.; Tang, Q.C. Free trial or no free trial: Optimal software product design with network effects. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2010, 205, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, W.; Chen, Z.G. Optimal pricing of virtual goods with conspicuous features in a freemium model. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2019, 23, 427–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, D.; Ghoshal, A.; Lahiri, A. Support forums and software vendor’s pricing strategy. Inf. Syst. Res. 2021, 32, 653–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedel, A.; Mulcahy, R.; Beatson, A.; Weeks, C. Advertising in freemium services: Lack of control and intrusion as the price consumers pay. J. Advert. 2025, 54, 322–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.W.; Ni, J.; Yu, D.G. Application developers’ product offering strategies in multi-platform markets. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2019, 273, 320–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.G.; Hou, R.; Zhou, Y.W. Platform competition for advertisers and viewers in media markets with endogenous content and advertising. J. Syst. Sci. Syst. Eng. 2020, 29, 36–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.J. Strategy analysis for a digital content platform considering perishability. Ann. Oper. Res. 2023, 320, 415–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.H.; Chamnisampan, N.; Sin, L. Freemium vs. Deterrence: Optimizing revenue in the face of piracy competition. J. Bus. Res. 2025, 194, 115354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mothersbaugh, D.L.; Kleiser, S.B.; Hawkins, D.I. Consumer Behavior: Building Marketing Strategy, 15th ed.; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.Z.; Choudhary, V. Impact of competition from open source software on proprietary software. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2022, 31, 731–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harviainen, J.T.; Ojasalo, J.; Kumar, S.N. Customer preferences in mobile game pricing: A service design based case study. Electron. Mark. 2018, 28, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.H.; Hua, Z.S.; Zhang, Z.G.; Bi, W.J. Analysis of freemium business model considering network externalities and consumer uncertainty. J. Syst. Sci. Syst. Eng. 2018, 27, 78–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.J.; Liao, C.N.; Chen, Y.J. Optimal selling scheme in social networks: Hierarchical signaling, sequential selling, and chain structure. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2023, 32, 2138–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fainmesser, I.P.; Lauga, D.O.; Ofek, E. Ratings, reviews, and the marketing of new products. Manag. Sci. 2021, 67, 7023–7045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, K.; Xiao, F.; Zhang, X.Y.; Wang, J.J. Platform strategies and user stickiness in the online video industry. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2019, 143, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Wang, W.X.; Jiao, Y.Y. Promoting or inhibiting? The impact of the information cocoon on customer stickiness in e-commerce platforms: The moderating role of decision-making style. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2025, 71, 101505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, K.K.F.; King, J.L.C.; Hollebeek, L.D. Social media marketing activities, customer engagement, and customer stickiness: A longitudinal investigation. Psychol. Mark. 2024, 41, 1597–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.; Keller, K.L.; Chernev, A. Marketing Management, 16th ed.; Pearson: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Amaldoss, W.; Du, J.; Shin, W. Pricing strategy of competing media platforms. Mark. Sci. 2024, 43, 488–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.M.; Wei, Y.S.; Nan, G.F.; Li, D.H. Pay-to-play versus hybrid bundling for digital game platforms in digital decarbonization era. Ann. Oper. Res. 2024, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.Z.; Cui, S.L.; He, N.; Li, K.Y.; Tian, L. Contract selection and piracy surveillance for video platforms in the age of social media. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2023, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.Z.; Zhang, Y. Whether to add a digital product into subscription service? J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 19, 921–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, Y.K.; Hu, B. From growth to monetization: Managing freemium services. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2025, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avinadav, T.; Bunker, A.E. The effect of risk aversion and financing source on a supply chain of in-app products. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2021, 29, 2145–2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.W.; Han, M.S.; Wang, K. Symmetric or asymmetric? Value-added service design for new and remanufactured products under competition. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2025, 287, 109682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.J.; Zhang, K.F.; Srinivasan, K. Freemium as an optimal strategy for market dominant platforms. Mark. Sci. 2019, 38, 150–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.S.; Jain, S.; Kannan, P.K. Optimal design of free samples for digital products and services. J. Mark. Res. 2019, 56, 419–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Navarrete, F.; Sanchez-Soriano, J.; Bonastre, O.M. Allocating revenues in a Smart TV ecosystem. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2019, 26, 1611–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.W.; Zhu, C.N.; Qi, W.; Wang, J.W. Product line and service pricing considering negative network effects. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 170, 108328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, P.; Jiang, G.Y.; Zhao, X.R.; Wang, M.X. Quality effort strategies of video service supply chain considering fans preference and data-driven marketing under derived demand. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2023, 62, 101338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rietveld, J. Creating and capturing value from freemium business models: A demand-side perspective. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2018, 12, 171–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.F.; Yang, J.L.; Zhu, M.Y.; Majeed, S. Relationship between consumer participation behaviors and consumer stickiness on mobile short video social platform under the development of ICT: Based on value co-creation theory perspective. Inform. Technol. Dev. 2021, 27, 697–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, G. Effects of consumers’ uncertain valuation-for-quality in a distribution channel. Ann. Oper. Res. 2020, 329, 501–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfandari, L.; Denoyel, V.; Thiele, A. Solving utility-maximization selection problems with Multinomial Logit demand: Is the First-Choice model a good approximation? Ann. Oper. Res. 2019, 292, 553–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, P.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.W.; Jiang, X.X. Location optimization of offline physical stores based on MNL model under BOPS omnichannel. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2022, 17, 1633–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Gong, S.Y.; Li, X. Co-opetitive strategy optimization for online video platforms with multi-homing subscribers and advertisers. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2023, 18, 744–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Influence of change in the value-added service level or sticky depth coefficient on maximum platform profit. Note: profit* represents the maximum profit of the platform. (a) (). (b) ().

Figure 1.

Influence of change in the value-added service level or sticky depth coefficient on maximum platform profit. Note: profit* represents the maximum profit of the platform. (a) (). (b) ().

Figure 2.

Effects of sticky depth and sticky width on the optimal solutions under homogeneous services. Note: price*, demand*, profit* represent the optimal price, maximum demand and maximum profit. denote the price, demand, and profit in the normal sales period; denote the price, demand, and profit of the quality-reduction strategy for the basic product in the marketing period; denote the price, demand, and profit of the level-improvement strategy for value-added services in the marketing period. (a) The optimal price. (b) The maximum demand. (c) The maximum profit.

Figure 2.

Effects of sticky depth and sticky width on the optimal solutions under homogeneous services. Note: price*, demand*, profit* represent the optimal price, maximum demand and maximum profit. denote the price, demand, and profit in the normal sales period; denote the price, demand, and profit of the quality-reduction strategy for the basic product in the marketing period; denote the price, demand, and profit of the level-improvement strategy for value-added services in the marketing period. (a) The optimal price. (b) The maximum demand. (c) The maximum profit.

Figure 3.

Effects of sticky depth and sticky width on the optimal solutions under heterogeneous services. Note: price*, demand*, profit* represent the optimal price, maximum demand and maximum profit. denote the price, demand, and profit in the normal sales period; denote the price, demand, and profit of the quality-reduction strategy for the basic product in the marketing period; denote the price, demand, and profit of the level-improvement strategy for value-added services in the marketing period. (a) The optimal price. (b) The maximum demand. (c) The optimal price.

Figure 3.

Effects of sticky depth and sticky width on the optimal solutions under heterogeneous services. Note: price*, demand*, profit* represent the optimal price, maximum demand and maximum profit. denote the price, demand, and profit in the normal sales period; denote the price, demand, and profit of the quality-reduction strategy for the basic product in the marketing period; denote the price, demand, and profit of the level-improvement strategy for value-added services in the marketing period. (a) The optimal price. (b) The maximum demand. (c) The optimal price.

Table 1.

An overview of studies considering consumer stickiness and pricing strategies with freemium model.

Table 1.

An overview of studies considering consumer stickiness and pricing strategies with freemium model.

| Authors | Freemium | Consumer Stickiness | Quality Strategies | VAS Pricing 1 | Remarks |

|---|

| Guo et al. [2] | √ | | | | Examine the weight of social influence on customer time and money in freemium environment. |

| Avinadav and Bunker [43] | √ | | | | Analyze the stochastic impact of quality on the demand potential for paid products in freemium platform enterprises. |

| So et al. [36] | | √ | | | Investigate the impact of customer evaluations of company marketing activities and customer engagement on customer stickiness based on an empirical approach. |

| Rong et al. [34] | √ | √ | | | Analyze the factors influencing customer stickiness on video platforms and found that the platform’s available resources significantly impact customer stickiness, whereas price does not. |

| Li et al. [6] | √ | | √ | | Explore the impact of content differentiation, advertising differentiation, and content and advertising differentiation on the design of freemium model. |

| Rietveld [50] | √ | | √ | | Compare the freemium model with other business models and found that the diversity of premium services can enhance corporate benefits. |

| Liu et al. [48] | √ | | | √ | Analyze the optimal pricing problem for value-added services under pure bundling and mixed bundling strategies, incorporating the impact of negative network effects. |

| Kato and Dumrongsiri [8] | √ | | √ | √ | Investigate the impact of customer tolerance for usage restrictions and valuation heterogeneity on the design of freemium models. |