Abstract

Based on para-social interaction (PSI) theory and social identity perspective, this study explores the mechanisms driving consumers’ impulse buying in social live shopping. It examines how live content design, namely information comprehensiveness (INFCOM) and interactivity (INT), affects consumer cognition and affective experiences, namely perceived usefulness (PU), PSI, and sense of belonging (SOB), to generate the influence of the urge to buy impulsively (UBI), and further explores the moderating role of the consumer–broadcaster para-social relationship (PSR) between live content design and consumer experience. Findings indicate that in an accumulative social live shopping environment, comprehensive information and strong interactivity enhance consumer social identity, reduce shopping hesitations and obstacles, and encourage UBI. Forming a close consumer–broadcaster relationship is crucial for promoting social identity and increasing UBI. Even without interactive engagement, consumers who feel a close connection with the broadcaster still experience interaction and SOB. PSR influences impulse buying by enhancing consumer perceptions and thereby promoting UBI. This study advances the understanding of impulse buying from a social identity perspective and suggests that merchants and livestream designers can improve quality and sales by providing comprehensive product information and incorporating diverse interactive elements in live broadcasts.

1. Introduction

Accumulative social live shopping is a rapidly emerging marketing model characterized by frequent livestreams and social interactions, fostering strong trust relationships and stable social shopping ecosystems [1]. Through real-time interaction, consumers communicate directly with broadcasters and connect with like-minded individuals within the community, enhancing their sense of identification and belonging, which in turn increases trust and purchase desire. Unlike traditional live shopping, accumulative social live shopping builds robust communities on social media and livestream platforms, enhancing consumer stickiness and driving long-term profitability. Major e-commerce platforms, such as Little Red Book, Tik Tok, and YouTube, have adopted this model [2,3].

Social live shopping combines promotions, the atmosphere of live broadcasts, and others’ shopping behaviors to trigger impulse buying during livestreams [4,5]. This impulse buying boosts sales, accelerates shopping decisions, and enhances product competitiveness. Moreover, it improves the consumer experience by bringing a sense of novelty, excitement, and fun, promoting repeat purchases. However, despite the increasing commercial success of live shopping, the existing knowledge of the mechanisms driving impulsive buying in livestreaming remains insufficient, as highlighted in recent studies.

The current research on impulse buying primarily focuses on the following three aspects: cognitive, emotional, and social. Cognitively, studies examine the information processing and decision making; emotionally, studies concentrate on the pleasure derived from shopping; socially, studies explore the influence of social factors on impulse buying [6]. However, there remains a paucity of research on the specific mechanisms by which social identification impacts impulse buying. For example, studies have identified how factors, like social contagion and scarcity persuasion, can induce impulse buying behavior [7,8].

In accumulative social live environments, consumers’ impulse buying is deeply influenced by community culture, social identity, and group psychology. This type of shopping redefines the experience as a multisensory participatory event, enhancing consumers’ sense of group belonging and significantly impacting their purchasing decisions [9]. Particularly when the livestream community shows interest in a specific product, it can trigger consumers’ herd impulse buying behavior [10]. Emotional connections established by the broadcasters further drive impulse buying behavior. Therefore, analyzing consumer behavior from a social identification perspective provides critical insights for livestream platform operations and marketing strategies. Moreover, Luo et al. [7] emphasized the role of customer engagement and deal proneness in shaping impulsive buying tendencies, further validating the importance of understanding social dynamics in live shopping environments.

Despite these insights, a key research gap remains in how para-social interaction (PSI) theory applies to impulse buying in live shopping contexts. Existing studies largely focus on face-to-face social interactions or mediated communication, overlooking how PSI, an inherently one-sided yet emotionally significant relationship, influences purchasing behavior [11]. In information-overloaded and noisy environments, given that livestream broadcasters often create a strong emotional connection with consumers through frequent and personalized interactions, examining the role of PSI becomes especially relevant in understanding how these connections can drive impulse buying in the accumulative social live shopping setting. PSI theory posits that emotional connections and social interactions between media figures and audiences create an illusion of one-sided interaction, significantly influencing audience behavior [12]. In livestreaming, broadcasters use verbal cues and gestures to make consumers feel noticed and more inclined to purchase. In accumulative social live shopping, broadcasters, through frequent broadcasting and a long-term accumulated fan base, establish intimate relationships with consumers, which are fundamentally para-social in nature [13]. However, existing studies inadequately explore how para-social relationships (PSR) affect impulse buying behavior.

Analyzing the characteristics of livestream content significantly impacts consumers’ social identification and purchasing decisions. For example, comprehensive information speeds up the process of consumers acquiring the necessary information, thereby increasing the likelihood of purchase. While high interactivity, through body language and answering questions, fosters communication between broadcasters and consumers, enhancing mutual identification. Therefore, this research adopts information completeness (INFCOM) and interactivity (INT) to describe accumulative social live content design [14,15]. INFCOM attracts a broad audience and promotes social identity. In livestreaming, INT enhances community experience through effective communication, fostering social identity [16,17].

During impulse buying, consumers’ psychological reactions can be categorized into cognitive and emotional aspects [18]. Cognitive responses include acquiring useful information to effectively complete shopping tasks, which is perceived usefulness (PU) [17]. Positive emotional experiences are key triggers for impulse buying [16]. There is currently a lack of research exploring the emotional reactions of impulse buying in social live shopping from the perspective of social identity. PSI stimulates social expectations by establishing connections akin to actual social interactions [19]. These connections meet consumers’ social needs and enhance their impulse buying motivation. Simultaneously, a sense of belonging (SOB) as an emotional experience of social feedback can further prompt purchasing decisions within the livestream communities [20]. To delve deeper into the influence mechanisms of social identity on impulse buying, this study utilizes PSI to describe social expectations and SOB to describe social feedback.

In an accumulative social live shopping environment, the impact of livestream content design on consumer experience varies depending on the relationship with the broadcaster. Current research mainly focuses on broadcaster characteristics, with less attention paid to the emotional connections between consumers and broadcasters [17]. For instance, the existing research points to the key role that para-social relationships and anticipated emotions play in mediating impulse buying tendencies, especially when scarcity is a factor [8]. However, the rise of key opinion consumers (KOCs) indicates that even with fewer followers, KOCs exert more profound impacts on community groups through their relationship networks. Social media research shows that PSR between fans and social media figures significantly increases information credibility, purchase intention, and community loyalty [21,22]. Existing studies lack the in-depth exploration of PSR’s moderating mechanisms in livestream consumers’ impulse buying. Therefore, this research aims to examine the moderating role of PSR in the relationship between livestream content design and consumer experience.

Based on the aforementioned practical needs and gaps in the existing research, this study explores the effects of livestream content design (INFCOM and INT) on consumers’ cognitive and emotional experiences (PU, PSI, and SOB) from a social identity perspective and further investigates the mechanisms underpinning impulse buying. Additionally, the study examines PSR’s moderating role in the relationship between livestream content design and consumer experience. The findings indicate that comprehensive information and high interactivity in accumulative social live shopping enhance consumer social identity, reduce shopping hesitation, and promote impulse buying decisions. Establishing intimate relationships between consumers and broadcasters plays a critical role in fostering social identity and increasing UBI. Even without direct interactive behavior, consumers with close relationships still experience perceived interaction and belongingness in the shopping environment. Furthermore, this study reveals PSR’s impact mechanisms on consumers’ impulse buying, demonstrating that following behavior towards the broadcasters triggers strong perceptions, thereby facilitating UBI.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Impulse Buying Behaviour of Consumers

Impulse buying, defined as spontaneous purchases without prior planning [23], often occurs in e-commerce, influenced by website recommendations or consumer suggestions rather than predefined goals. Impulse buying is considered based on information processing [24], triggered by external stimuli (Stimulus, S) involving perceptual stimuli, information processing, and psychological activities that elicit internal reactions from consumers (Organism, O). This ultimately leads to impulsive responses (Response, R) [18,23,25]. The S-O-R paradigm is commonly used in research to model consumer impulse buying in the context of livestreaming e-commerce [25]. Chen and Gao [26] explored how promotional tactics, host characteristics, and interactivity influence irrational consumer behavior through the S-O-R framework, offering a theoretical foundation for discussing impulsive purchasing motivations in livestream shopping.

Parboteeah et al. [18] presented an online impulse buying model categorizing website cues into task-relevant (TR) and mood-relevant (MR). TR cues aid task execution, while MR cues enrich shopping pleasure. Grounded in the S-O-R framework, this model posits that websites offering high-quality TR and MR cues can shape consumer cognitive and affective reactions, consequently influencing impulse buying behavior. Some studies reveal how live stimuli induce impulse buying behavior by influencing consumer cognitive and affective reactions through their psychological experiences. Cognitive reactions include trust in products and sellers [27] cognitive assimilation [16], and PU [17]. Affective reactions include arousal [16] and perceived enjoyment [17]. Huang and Suo [28] found that interpersonal interaction positively influences impulse buying decisions. Fu and Hsu [11] further explored how virtual interaction and a sense of place foster impulse buying behavior, providing insights into how spatial factors contribute to shopping motivations. Ming et al. [29] discovered that the remote presentation of live platforms and social presence also affect trust and buying behavior. The herd effect in live environments suggests that consumer purchase intentions are influenced by the purchasing behavior of others [30].

Despite S-O-R exploration, the role of social identity in live environments is overlooked. This study explores the impact of affective reactions on impulse buying from the perspective of social identity. Through the PSI theory, it studies the connection established between consumers and broadcasters that is similar to real social interaction and emphasizes the importance of social expectations and social feedback in impulse buying through PSI and SOB to further delve into the mechanisms of social identity on impulse buying.

2.2. Social Identity Research

Research on social identity in e-commerce continues to deepen, providing important perspectives for understanding consumer group behavior and their relationship with e-commerce platforms. Tajfel [31] pointed out that social identity is a part of an individual’s self-concept, originating from membership in one or more social groups, with its associated values and emotions. The academic community recognizes that consumer identity significantly impacts behaviors like purchase decisions [32], brand preferences, consumer loyalty [33], psychological feelings of brand community, and brand commitment [34], as well as the improvement of consumer satisfaction and repurchase likelihood [35]. Chen et al. [36] emphasized the role of platform functions in shaping consumer identity, which drives participation behavior in livestreaming commerce, providing a theoretical basis for exploring consumer engagement.

Social feedback and social expectations are two important aspects of social identity [37]. Social feedback includes the responses individuals receive from others or the social environment, where SOB represents the emotional experiences gained from it. Emotional experiences from livestreaming communities enhance buying willingness [20]. Social expectations refer to anticipated results from interactions, characterized by PSI [19].

2.3. Para-Social Interaction Theory

2.3.1. Para-Social Interaction (PSI)

PSI is an illusionary friendship or intimate relationship between viewers and remote media personalities [38,39]. Essentially, PSI is a one-way, asymmetrical, non-reciprocal interaction controlled by media personalities [39,40]. With the emergence of social media, allowing consumers to interact with media personalities at unprecedented frequencies and intensities, PSI has been used to understand interactions within online virtual communities [41], including YouTube [42], relationships between internet celebrities and consumers [43], and consumer interactions on social e-commerce platforms [44]. When individuals engage in PSI, they develop social expectations, crucial in forming impulse buying behavior [45]. Chen et al. [46] showed how social presence influences consumer identification, further shaping purchase decisions in livestreaming scenarios, providing empirical evidence for PSI’s role in impulse buying.

Despite PSI’s widespread use, research on its application in livestreaming is limited. To deepen the study of affective reactions and social identity, this research employs PSI to characterize social expectations and SOB to represent social feedback. Expanding on PSI theory, the paper explores impulse buying in livestreaming consumers and investigates the moderating effect of PSR on the relationship between livestreaming design and consumer experience.

2.3.2. Para-Social Relationship (PSR)

PSR reflects the ongoing relationship between the audience and media personalities, resembling a lasting friendship rather than a singular exposure [47]. In livestreaming, consumers readily perceive an illusion of interaction, forming a one-sided “friendship” with broadcasters. Live broadcasts allow two-way real-time communication, and the accumulative social live shopping model solidifies the relationship between broadcasters and fans, constituting PSR. The conventional wisdom is that broadcasters with a large number of followers positively impact sales [48]. Denghua and Lidan [49] highlighted how virtual interactions between consumers and broadcasters influence purchase intentions and brand loyalty through establishing para-social relationships, underlining the importance of building these virtual ties. For those with fewer fans but a close relationship with them, whether they can rely on PSR to build a stable and loyal fan base is worth exploring. This study investigates the moderating role of PSR in live content design and consumer experience.

Although the relationship between PSI and PSR has been well-explored in traditional media and social platforms, its application in livestreaming environments remains relatively underdeveloped. Specifically, there is a lack of research that fully explores how real-time interactions in livestreaming influence the transition from PSI to PSR, and how this evolving relationship affects consumer behavior, such as impulse buying and long-term loyalty. Studies such as those by Aw and Labrecque and Kim [43,50] suggest that PSI and PSR play crucial roles in shaping consumer attitudes, yet further investigation is needed to understand how these interactions manifest uniquely in livestreaming, where immediacy and interactive elements differ significantly from other media forms.

3. Research Hypothesis

3.1. The Urge to Buy Impulsively (UBI)

UBI refers to the sudden and spontaneous desire or impulse experienced by consumers to buy a product [51]. Only when consumers experience the desire for impulse buying is it possible for them to engage in impulse buying behaviors to satisfy this urge [18]. When using structural models, UBI can serve as a more potent measure of impulse buying than the actual impulse buying behavior due to the controlled environment’s challenges [52]. Therefore, consistent with previous research [18,45], UBI is employed as a proxy variable for impulse buying in the context of livestreaming.

3.2. Consumer Experience

The extant research on impulse buying has primarily examined cognitive, emotional, and social factors. However, in traditional online shopping contexts, consumers’ psychological reactions are divided into cognitive and affective categories, yet for accumulative social live shopping that values social competence, research on the social dimension is lacking. Therefore, based on the S-O-R framework, this study explores the impact of live content design (INFCOM and INT) on consumer cognition and experience (PU, PSI, and SOB) from a social identity perspective. Additionally, it examines the moderating role of consumer–broadcaster PSR between live content design and consumer experience.

3.2.1. Perceived Usefulness (PU)

In cognitive reactions, consumers’ impulse buying can be attributed to acquiring information that streamlines shopping efficiency, known as PU [18,45]. Current research predominantly examines the relation between the PU of products or services sold via traditional online or offline channels and the propensity to purchase [5]. In the context of livestreaming sales, PU represents the degree to which online consumers believe that livestreaming aids in achieving purchasing goals and enhances shopping efficiency [16]. According to social identity theory, individuals build stronger identification and involvement with activities they perceive as valuable, such as watching livestreams, thereby increasing the likelihood of impulse purchases, improving shopping efficiency. Studies by Lim et al. [53] have established a positive relationship between PU and consumer buying behavior in online shopping environments. Extending this concept to live shopping contexts offers a novel perspective on understanding the process of social identification in e-commerce. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1.

PU has a positive impact on UBI.

3.2.2. PSI

Social identity theory explains how individuals shape their behavior by emulating the social roles they identify with. Especially reflected in the livestreaming environment, PSI between broadcasters and viewers strengthens their bond and may prompt viewers to mimic the broadcasters’ behaviors, such as purchasing recommended products. Thus, enhanced PSI might drive viewers’ impulsive buying behaviors.

The emotional experience, influenced by social identity (social expectations and social feedback), triggers impulsive buying. Despite limited research, PSI significantly impacts online impulsive buying in social commerce [16], whereas livestreaming studies primarily focus on content and social elements, with little on PSI [54].

Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2.

PSI has a positive impact on (UBI).

The study by Olgun [55] shows that on social media and digital platforms, PSI crucially promotes the relationship between consumers and brands or broadcasters. The formulation of H2, by deeply exploring how PSI might enhance impulsive buying behaviors in e-commerce livestream viewers, linking social identity theory with media interaction and examining its psychological and behavioral impact on buying behaviors, thus expanding the theory’s scope.

3.2.3. Sense of Belonging (SOB)

SOB refers to an individual’s identification and connection with a specific group, organization, location, or identity [56]. In livestreaming e-commerce, SOB significantly motivates consumer participation [1]. While existing research focuses on broadcaster image and content influence on SOB, there is limited exploration of the relationship between PSI and SOB [57]. Social identity theory emphasizes that individuals build and maintain their social identity by identifying with a community. In livestreams, viewers feel part of the virtual community through PSI, thereby enhancing their SOB. Similar to social media interactions, livestreaming interactions play a crucial role in forming new social identity constructions [58] This emotional resonance strengthens social identification and builds SOB, providing an effective social experience in constructing online community belonging. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H3.

PSI has a positive impact on SOB.

SOB is a crucial component of social identity. When consumers have a strong SOB within social media environments, they value peer opinions and incorporate social norms into their beliefs [44]. Current studies mainly address individual needs and product characteristics’ impact on UBI in online livestreaming but lack focus on SOB’s influence, an element of social identity [54,59]. Enhanced group belonging in livestreams, driven by dynamic interactions, can align individual behavior with group norms. Recent research highlights the significant impact of community belonging on online consumer behaviors, particularly in social media and online communities [60]. This study examines how SOB in a live shopping context enhances impulse purchases, enriching the e-commerce research framework and offering new insights into consumer behaviors in virtual communities. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H4.

SOB has a positive impact on UBI.

3.3. Live Content Design

Building upon the S-O-R framework and social identity theory, this study extends the theoretical lens to examine the design elements of livestreaming content. The live content design, comprising INFCOM and INT, serves as the stimulus in the S-O-R model, potentially influencing consumers’ cognitive and social experiences (organism) in the context of livestreaming e-commerce.

From a social identity perspective, the design of live content plays a crucial role in shaping consumers’ identification with the virtual community and the brand. INFCOM and INT are posited to influence how consumers perceive their role within the livestreaming environment and their relationship with the broadcaster and other viewers. This theoretical framing allows us to explore how these design elements not only provide information and facilitate interaction but also contribute to the formation and reinforcement of social identity in the digital marketplace.

3.3.1. Information Comprehensiveness (INFCOM)

In online shopping, INFCOM assesses whether the environment provides necessary information for consumers [61]. While research has mainly focused on other variables’ impact on PU, such as live content and individual needs [62], the role of INFCOM in enhancing PU is still limited. Providing comprehensive information can stimulate more active audience participation and interaction, thereby strengthening PU and assisting in shaping consumer identity. From the perspective of social identity theory, comprehensive information influences PU as individuals gain confidence in their purchasing decisions through access to complete product information. This tendency reflects individuals identifying with sources that provide valuable and comprehensive information, particularly in social cumulative livestreaming contexts. Recent studies, such as by Dwiputra et al. [63] confirm that information comprehensiveness directly affects the quality of consumer information processing and purchasing intentions. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H5.

INFCOM has a positive impact on PU.

3.3.2. Interactivity (INT)

INT in live content constitutes inherent interactive signals and clues that vary according to consumer perception. All interactive signals are consumer-oriented, creating an impression of real-time interaction, thereby creating and reinforcing consumers’ perceived PSI [64]. According to social identity theory, these signals foster social identity by integrating audiences into a live community and enhancing their identification with broadcasters and brands [12,65].

INT also improves the PU of information. Studies find that INT, by enhancing information consumption and understanding, increases consumers’ satisfaction and confidence in their purchasing decisions [66]. Social identity theory explains that through interactive behavior, consumers identify with group behaviors they resonate with, thus amplifying content’s PU.

Moreover, INT reinforces consumers’ SOB to the community. By promoting social participation and shared experiences, INT significantly increases consumers’ SOB, confirming their social identity and enhancing brand loyalty [67]. This not only demonstrates a new avenue for social identity application in e-commerce but also highlights the critical role of SOB in forming virtual communities and bolstering consumer loyalty.

Therefore, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

H6.

INT has a positive impact on PU.

H7.

INT has a positive impact on PSI.

H8.

INT has a positive impact on SOB.

3.4. The Regulatory Role of PSR

Broadcasters’ social influence, including PSR and opinion leaders, significantly impacts livestreaming effectiveness [68]. PSR, reflecting the intimate relationship between fans and media personalities, influences purchasing behavior, suggesting that variations in PSR could affect experiential differences in livestreaming when faced with the same livestreaming content design in an accumulative social livestreaming context.

Previous research indicates that PSR influences the level of support or skepticism consumers have towards information, leading to biases in information perception [69]. Based on these findings, this study hypothesizes that a long-standing PSR will influence consumer experiential bias in livestreaming. Baek et al. [70] shows that PSR enhances users’ trust in information by mimicking real-life patterns of social interaction, providing a theoretical basis for PSR to strengthen the relationship between INFCOM and PU.

Wu [71] found that high-quality interactions enhance information’s perceived usefulness through PSR, supporting the view that PSR enhances information practicality through trust. Kim [50] found that as the interaction between participants and content creators increases, their PSI also strengthens. This supports the hypothesis that PSR enhances the positive relationship between INT and PSI, thus improving audience’s social identification and engagement. Liu et al. [72] emphasized that social media interactions enhance community belonging, aligning with the view that PSR strengthens the link between INT and community belonging.

Therefore, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H9.

PSR positively moderates the relationship between INFCOM and PU.

H10.

PSR positively moderates the relationship between INT and PU.

H11.

PSR positively moderates the relationship between INT and PSI.

H12.

PSR positively moderates the relationship between INT and SOB.

3.5. Conceptual Framework

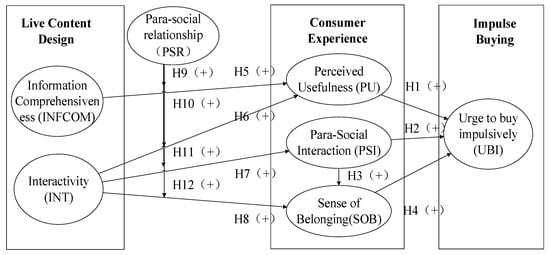

In Figure 1, we present the conceptual framework of this study, illustrating how live content design, represented by INFCO and INT, influences consumer cognition and affective experiences, which in turn drive UBI. The model draws on the stimulus–organism–response (S-O-R) framework and social identity theory, suggesting that live content design elements act as external stimuli (S), affecting the consumer’s internal states (O), including PU, PSI, and SOB. These internal states subsequently lead to a response (R) in the form of UBI. Additionally, the model explores the moderating role of para-social relationships (PSR) between live content design and consumer experiences. Specifically, PSR enhances the effects of INFCOM and INT on consumer cognition (PU) and social experiences (PSI and SOB).

Figure 1.

The model of the research.

By incorporating social identity theory, the model provides a comprehensive framework for driving impulse buying. Meanwhile, this model fills several research gaps in the literature. First, it extends the application of social identity theory to the context of livestreaming e-commerce by examining how content design shapes consumers’ social identity. Second, the model introduces PSR as a moderating variable, providing insights into how the strength of the relationship between consumers and broadcasters influences impulse buying behavior. The model emphasizes that in accumulative social live shopping environments, the strength of PSR significantly impacts how consumers perceive information comprehensiveness and interactivity, thereby enhancing social identity and impulse buying.

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Experimental Design

4.1.1. Livestreaming Video Materials Source

This study designed an experiment to test the hypothesis by editing authentic livestreaming videos of Li Jiaqi selling coconut popsicles on Taobao. This approach was chosen to control product and marketing features, leverage Taobao’s credibility as China’s top e-commerce platform, utilize videos rich in product information and interactive cues for better experimental control, and ensure some participants developed a strong PSR with the well-known broadcaster, Li Jiaqi.

4.1.2. Development and Manipulation of Livestreaming Video Materials and Variables

The selected videos were divided into informational and interactive scenarios. Informational scenarios covered product details, like flavor, ingredients, packaging, price, storage, and logistics. Conversely, interactive scenarios featured the broadcaster addressing consumer queries, showing products upon request, sharing personal stories, and engaging with consumers.

Subsequently, four scenarios (S1–S4) were devised, as detailed in Table 1. By selectively retaining or omitting informational and interactive elements in each scenario, control over INFCOM and INT was achieved. S1 and S2 shared similar but minimal interactive elements, with S2 featuring more extensive product information compared to S1.

Table 1.

Definitions of four scenarios.

To objectively differentiate between high and low levels of INT and INFCOM, the study established clear definitions for each construct. INFCOM is defined on a spectrum where low INFCOM provides limited product information, including only basic descriptions, such as flavor and price, while high INFCOM offers comprehensive product details, encompassing specifications, ingredients, packaging, price, storage instructions, and logistics information. Similarly, INT is conceptualized as a continuum, where low INT involves minimal interaction between the broadcaster and viewers, primarily consisting of one-way product presentation, whereas high INT features frequent and diverse interactions, including addressing consumer queries, showing products upon request, sharing personal stories, and actively engaging with consumers. These definitions were operationalized in experimental design, with S1 and S2 representing low INT scenarios, and S3 and S4 representing high INT scenarios. Likewise, S1 and S3 exemplify low INFCOM scenarios, while S2 and S4 demonstrate high INFCOM scenarios.

4.1.3. Pilot Study

Before conducting the main experiment, a small-scale pilot study was performed to test the validity of the experimental materials, including the video clips and questionnaires. The pilot study helped refine the content and duration of the video materials and ensured clear differentiation between the manipulated variables (e.g., information comprehensiveness and interactivity). Additionally, the reliability and validity of the questionnaire were preliminarily tested during the pilot, laying a foundation for data collection in the main experiment.

4.2. Operationalization and Tool Design

Concepts were measured using a Likert seven-point scale (1 = “strongly disagree”, 7 = “strongly agree”). Classic e-commerce and media scales were adapted for the livestreaming context. Adaptive modifications of classic scales proposed for traditional e-commerce and media environments in livestreaming context were employed in this study to measure relevant concepts. Specifically, INFCOM was measured with three items from Wixom and Todd [27], and INT with four items from Labrecque and Homburg et al. [12,73]. PU used three items from Wixom and Todd [27] and Parboteeah et al. [18] . SOB was measured with five items from Teo et al. [74], and UBI with three items from Parboteeah et al. [18].

Regarding the measurement of PSI and PSR, there is limited research that distinguishes between them. Therefore, the study referred to widely used PSI scales developed in different environments, including those used by Rubin et al., Hoerner, and Labrecque [12,39,75], and divided items for PSI and PSR based on their definitions. Specifically, the items were categorized into two groups. One set of items measured consumers’ immediate perceptions and reactions to the broadcaster or environment during livestreaming, used for measuring PSI during livestreaming. The other set of items mainly focused on describing consumers’ general cognitions or emotions towards the broadcaster. These cognitions or emotions could be formed outside of livestreaming by interacting with the broadcaster on social media and social networks in daily life. Ultimately, 17 items were selected to measure PSR, and 12 items were chosen to measure PSI. Table 2 presents a summary of the constructs, the number of items used to measure each construct, and the sources from which these scales were adapted. The specific items can be found in Appendix A Table A1.

Table 2.

Constructs, scales, and their sources.

4.3. Sample and Data Collection

This study employed laboratory and online experiments, utilizing pre-recorded and edited livestreaming videos. The webpages contained both the livestreaming videos and survey questionnaires. Webpage links corresponding to experimental scenarios were randomly distributed to participants via social networks to measure participants’ PSR with the broadcaster and consumer psychological characteristics.

Laboratory and online experiments utilized pre-recorded and edited livestreaming videos embedded in webpages with survey questionnaires. Links to experimental scenarios were randomly distributed via social networks. Participants first completed the PSR scale to measure pre-existing PSR with the broadcaster. After viewing the livestreaming videos, they answered additional questions.

This study adopted a convenience sampling method, drawing participants from a pool of regular livestreaming consumers. This method was chosen because it aligns well with the research objective of examining consumer behavior in real-world livestreaming environments. The convenience sampling approach was suitable, as it allowed us to gather a diverse sample of respondents familiar with e-commerce livestreaming.

5. Data Analysis and Results

5.1. The Characteristics of Sample

Data were collected for four scenarios, yielding 89, 95, 88, and 113 responses, respectively. A minimum completion time of 90 s more than the video duration was set to ensure valid responses. Ultimately, 61, 75, 67, and 82 valid questionnaires were obtained for the four scenarios. The demographic data of participants are detailed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Demographic characteristics of the sample.

The sample comprised 175 males and 110 females, with the majority aged between 18–35 years (258 participants). Most participants held a bachelor’s degree (145), and 97 reported shopping online 6–10 times per month. A significant proportion (263) had prior experience watching e-commerce livestreams, and 243 had previously made purchases during livestreams.

5.2. Descriptive Statistics and Manipulation Checks

The normality of the data was verified using skewness, kurtosis, and the Kolmogorov–Smirnov (K–S) test. Table 4 demonstrates the manipulations’ effectiveness for INFCOM and INT across scenarios. Specifically, one-way ANOVA results showed significant differences in INFCOM item scores (INFCOM1-3) between control (S1) and high information completeness scenarios (S2) (p < 0.05). Similarly, significant differences in INT item scores (INT1-4) were observed between control (S1) and high INT scenarios (S3) (p < 0.05). These findings confirm the effectiveness of the experiment’s manipulation of both independent variables.

Table 4.

Manipulation check.

5.3. Common Method Bias Test

To assess common method bias due to self-reported scales, Harman’s single-factor test method was employed. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted on all items related to the measured constructs to determine if there was a single factor that explained the majority of the variance [76]. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) indicated that the maximum variance explained by the first factor was 31.63%, well below the 40% threshold, suggesting no significant CMB in the data.

5.4. Measurement Model Test

The collected data exhibited a normal distribution, making it suitable for structural equation modelling (SEM) analysis. Mplus 7.0 was used for the analysis of both the measurement model and the structural model. Initially, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was employed to test the measurement model. While the fit indices suggested acceptable fit of the data (χ2 = 1560.719, df = 1059, p < 0.001, χ2/df = 1.47, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.041, comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.954, Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) = 0.951), some standardized factor loadings for items related to PSI and PSR were below 0.7. Following previous studies [77], these items were removed, and CFA was rerun. The results show an improved fit in certain aspects (χ2 = 782.662, df = 539, p < 0.001, χ2/df = 1.45, RMSEA = 0.035, CFI = 0.979, TLI = 0.977). As shown in Table 5, Cronbach’s α, factor loadings, and composite reliability (C.R.) for each construct are all above 0.7, indicating good reliability for all constructs [78]. Additionally, the average variance extracted (AVE) values for each construct exceed the threshold of 0.5, demonstrating acceptable convergent validity. Furthermore, as indicated in Table 6, the square root of AVE for each construct is greater than its correlation with other constructs, confirming the good discriminant validity of the measurement model [79].

Table 5.

Reliability and validity test of conceptual items.

Table 6.

Interrelationships between concepts.

5.5. Structural Model Test

While the measurement model is acceptable, it is crucial to consider measurement errors when validating hypotheses [79]. Unlike regression analysis, SEM allows for the simultaneous assessment of measurement and regression errors [18] . Following Parboteeah et al. [18], we used SEM to test the hypotheses. The structural model showed an acceptable fit (χ2 = 720.526, df = 482, χ2/df = 1.495, RMSEA = 0.042, CFI = 0.961, TLI = 0.958), with all paths significant, supporting all hypotheses. As shown in Table 7, the consumer experience components—PU (β = 0.154, p < 0.01), PSI (β = 0.542, p < 0.025), and SOB (β = 0.241, p < 0.01)—significantly influenced impulse buying intentions, while PSI also positively impacted SOB (β = 0.328, p < 0.01). INFCOM positively affected PU (β = 0.329, p < 0.01), and INT positively impacted PU (β = 0.383, p < 0.01), PSI (β = 0.249, p < 0.01), and SOB (β = 0.361, p < 0.01).

Table 7.

Hypothesis testing.

Subsequently, a mediation effect test was conducted. As this study employed scales to measure variables in research, traditional regression analysis might overlook measurement errors, leading to distorted parameter estimation results. Therefore, this study utilized SEM for multiple mediation analysis [80]. Specifically, the bootstrap method was employed to test the mediating role of consumer experience between live content design and UBI [81]. Table 8 shows that PU (β = 0.169, LLCI = 0.034, ULCI = 0.316), PSI (β = 0.546, LLCI = 0.445, ULCI = 0.636), and SOB (β = 0.263, LLCI = 0.122, ULCI = 0.384) significantly mediate UBI. Table 9 confirms PU’s mediation in the INFCOM → PU → UBI relationship (β = 0.055, LLCI = 0.012, ULCI = 0.116), with the direct effect of INFCOM on UBI being non-significant (β = 0.038, LLCI = −0.090, ULCL = 0.160), indicating PU fully mediates the INFCOM–UBI relationship.

Table 8.

Bootstrap test results for mediation effects.

Table 9.

Indirect effects, direct effects, and total effects.

Further, the indirect effects of PU (β = 0.065, LLCI = 0.014, ULCI = 0.127), PSI (β = 0.138, LLCI = 0.069, ULCI = 0.215), and SOB (β = 0.095, LLCI = 0.038, ULCI = 0.165) in the INT-UBI relationship were significant, with direct effects being non-significant (β = 0.038, LLCI = −0.090, ULCI = 0.160), meaning PU, PSI, and SOB fully mediate INT’s effect on UBI. The analysis of the INT → PSI → SOB → UBI path showed significant chained mediation (β = 0.022, LLCI = 0.010, ULCI = 0.044).

Following Kenny and Judd’s [82] recommendations, a moderation effect test of the pre-existing PSR was conducted (Table 10). Results revealed that PSR positively moderates the effects of INFCOM (β = 0.112, p < 0.05) and INT (β = 0.143, p < 0.01) on PU, supporting hypotheses H9 and H10. PSR also significantly moderates the INT-PSI (β = 0.135, p < 0.025) and INT-SOB (β = 0.279, p < 0.01) relationships. Consumer PSR with the broadcaster enhances the impact of information completeness and interactivity, boosting cognitive and social identification, thus increasing impulse buying likelihood. These findings highlight the significant influence of PSR on consumer psychological reactions and buying behavior.

Table 10.

Moderation effects of PSR.

6. Discussion

In this study, we found that INFCOM and INT positively impact impulse buying behavior by enhancing the consumer experience during livestreaming. This aligns with previous research, such as that conducted by Chen et al. and Li and Cheng [26,83], who demonstrated the mediating role of social presence between social identity and purchase intention. Specifically, we further emphasized how social presence amplifies the influence of interactivity on impulse buying, supported by the studies of Gunasekara et al. and Jia et al. [84,85].

Moreover, by proposing hypotheses based on PU and PSI, this study significantly advances the application of social identity theory in accumulative social live shopping. Compared to the research by Zhao et al. [86], we innovatively integrate social identity theory with e-commerce demands, exploring its usefulness in live shopping environments (H1 hypothesis). Simultaneously, the H2 hypothesis underscores the crucial role of PSI in enhancing consumers’ impulse buying intentions, complementing the research of Fu et al. [87] and highlighting the unique interactive features of accumulative social media platforms.

It is worth noting that our study echoes the views of Kaur et al. [88], further demonstrating the significant enhancement of PSI on SOB, which surpasses the impact of brand community identity on loyalty. Additionally, by combining discussions from Khine and Dreamsonand Mai et al [89,90]. on how cultural backgrounds affect live e-commerce interactions, our research enriches the cultural analysis of social identity and impulse buying in Asian markets.

When exploring the effects of INFCOM and INT on PU and PSI (H5 to H8), our study resonates with the explorations of Liao et al. and Chuang [91,92]. Meanwhile, H9 to H12 reveal the moderating role of PSR, discovering that improving PSR behavior can effectively drive sales in certain scenarios, including those with a smaller fan base, aligning with the findings of Ji et al. [93]. Our research also complements the discussion by Cheung et al. [94] on how PSR serves as a core factor in explaining how consumers process live content.

Furthermore, Wu and Huang [71] emphasize the critical mediating role of trust in the stimulus–organism–response (SOR) model, providing further theoretical support for our study and aiding in deeper explanations of consumer behavior in real-time commerce. In particular, the research by Khoi et al. [95], which also adopts the SOR model to explore how vividness and personalization in live e-commerce influence impulse buying through consumption vision and telepresence, complements our findings. Our study further demonstrates how PSR affects impulse buying behavior by moderating consumer perceptions within the SOR framework, offering a new perspective on the application of the SOR model.

Simultaneously, by integrating the viewpoints of Kim and Park [96], we focus on the mediating role of perceived interactivity and seller trust between PSI and experience satisfaction. This discovery not only aids in understanding how real-time content design and interactivity impact impulse buying but also complements research on consumer experience satisfaction. Additionally, the study by Sun et al. [97], which explores the influence and mechanisms of online group buying behavior based on social identity theory and emotional contagion theory, echoes our theoretical foundation, jointly advancing the understanding of online shopping behavior.

Finally, by integrating research from Nadroo et al. and Pires et al. [98,99], our study provides a more comprehensive perspective on consumer behavior in real-time e-commerce. Specifically, the research by Xueyun and Yiyang, F. [100], which uncovers the underlying motivations of livestreaming reward behavior from a sociological perspective, complements our exploration of the relationship between live interactions and consumer behavior. Meanwhile, the study by Zhang et al. [101], which investigates the impact of WeChat interactions on brand evaluation and finds the mediating role of para-social interaction, shares similarities with our findings on the moderating role of PSR, emphasizing the importance of interaction in consumer behavior.

7. Conclusions

In accumulative social live shopping, broadcasters create PSI, fostering a sense of attention that increases consumer inclination for impulse buying. This also establishes para-social connections, encouraging impulse buying behavior. However, further research is required to examine how these para-social characteristics, viewed through a social identity perspective, impact consumer impulse buying behavior. Therefore, this study investigates the impact mechanism of live content design on consumer impulse buying in accumulative social live shopping, based on the PSI theory from a social identity perspective. The findings indicate that INFCOM and INT in live broadcasts positively influence impulse buying behavior by enhancing consumer experiences. Further exploration of social presence reveals its mediating role between social identity and purchase intention, as social presence amplifies the effects of interactivity on impulse buying. The provision of interactive information to create a perception of engagement with the broadcaster stimulates consumers’ sense of belonging (SOB). This study confirms that, in their decision making, consumers consider SOB and identity and connect with specific groups to fulfil self-identity and values, thus positively affecting impulse buying. Additionally, this study demonstrates that consumers may have established a PSR with broadcasters before watching live broadcasts. This relationship significantly amplifies the impact of external live content design on consumer experiences.

This study proposes hypotheses to investigate the roles of PU and PSI in accumulative social live broadcasting and their influence on consumer behavior, significantly contributing to social identity theory. Through a detailed exploration of the cognitive and emotional mechanisms, the study refines the theoretical understanding of the relationship between para-social interaction and impulse buying in social live shopping contexts. This contribution advances prior research by integrating the concept of para-social relationships into the social identity framework, demonstrating how these relationships amplify consumer engagement and decision-making processes.

The study gives valuable recommendations for livestream designers and businesses. Managers should diversify and include more content to enhance INFCOM, as comprehensive information positively impacts PU. The study concludes that interactivity positively affects PU, PSI, and SOB, suggesting that managers should encourage consumer interaction and content sharing.

Conventional wisdom in livestreaming suggests that broadcasters with a large fan base drive better sale, but this often comes with high costs. This study emphasizes the impact of PSR behavior on impulse buying, indicating that even influencers with a smaller fan base can boost sales by refining their PSR. Recommendations advise livestream managers to enhance PSR cultivation and management. Creating a trustworthy and interactive environment fosters collaboration among consumers, reinforcing positive effects on INT, PSI, and SOB. Diverse interactive tools in social media communities also boost consumer interaction and sharing, enhancing PSR’s impact on INT and PU.

This study has limitations that future research can address. First, regarding the impact of live content design on consumer behavior, future studies should analyze its influence on consumer loyalty, word-of-mouth, and other aspects, providing more insights for e-commerce livestreaming.

In investigating factors affecting consumer emotional experiences, this study focuses on the effects of SOB and PU on impulse buying, excluding other potential influences. Future research should explore how other emotional factors affect consumer experiences and decision making, especially on social live shopping platforms.

Lastly, while this study suggests the moderating role of consumer–broadcaster PSR in the link between live content design and consumer experience, it does not thoroughly explore these mechanisms. Future research should examine how different types of consumer–broadcaster PSR relationships influence consumer engagement and experience in e-commerce livestreaming.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.L. and Y.Z.; methodology, Y.T.; software, W.Z.; validation, Z.Y., W.Z. and Y.T.; formal analysis, S.L.; investigation, Y.Z.; resources, S.L.; data curation, Y.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.Y.; writing—review and editing, W.Z.; visualization, Y.T.; supervision, S.L.; project administration, Y.Z.; funding acquisition, S.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (71871135 and 72271155) and Zhejiang Office of Philosophy and Social Science (25NDJC155YBMS).

Institutional Review Board Statement

In accordance with our institution’s guidelines for low-risk behavioral research, this study qualifies for exemption from formal ethics committee approval. The study utilized pre-recorded livestream videos in a controlled experimental setting, with no direct interaction between researchers and participants. All data were collected through fully anonymous online questionnaires. The study focused solely on general consumer behavior in a commercial context, with no sensitive or private topics involved.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

The items for each construct.

Table A1.

The items for each construct.

| Construct | Simplified Item Content |

| INFCOM (3) | The livestream provided comprehensive product information. |

| The livestream offered complete details about the product. | |

| The livestream gave all necessary product information. | |

| INT (4) | The broadcaster responded efficiently to consumer needs. |

| The broadcaster provided services per user requirements. | |

| The broadcaster listened to consumer needs. | |

| The broadcaster discussed personal topics. | |

| PU (3) | Watching the livestream helped make the right purchase decision. |

| The livestream allowed for quicker purchase decisions. | |

| The livestream improved shopping effectiveness. | |

| SOB (5) | I felt strongly engaged in the livestream. |

| I fully trusted the broadcaster and other consumers. | |

| I enjoyed being a participant in the livestream. | |

| I was very invested in the livestream. | |

| The livestream atmosphere was vibrant. | |

| UBI (3) | I felt an impulse to buy the product even if unplanned. |

| I desired to buy the product even if it wasn’t my goal. | |

| I wanted to buy the product even if not on my list. | |

| PSI (12) | The broadcaster’s jokes enhanced watchability. |

| Watching helped form opinions about the product. | |

| The broadcaster’s feelings about the product aided my decision. | |

| The broadcaster seemed to know what I wanted to learn. | |

| The livestream revealed the broadcaster’s personality. | |

| I enjoyed comparing my thoughts with the broadcaster’s words. | |

| Watching the livestream was relaxing and enjoyable. | |

| I felt the broadcaster kept me company throughout. | |

| I wanted to chat or consult with the broadcaster. | |

| I wanted to comment or message the broadcaster. | |

| Watching the livestream was worthwhile. | |

| I wanted to watch other videos by the broadcaster. | |

| PSR (17) | I looked forward to seeing the broadcaster on other media. |

| I would watch if the broadcaster appeared elsewhere. | |

| I would read stories about the broadcaster. | |

| I care about what’s happening with the broadcaster. | |

| The broadcaster increases the credibility of the information. | |

| I trust the information provided by the broadcaster. | |

| I find the broadcaster charismatic. | |

| I think the broadcaster is authentic and real. | |

| The broadcaster makes me feel comfortable. | |

| The broadcaster feels like an old friend. | |

| I miss the broadcaster when not seeing the livestream. | |

| I feel sorry for the broadcaster’s mistakes. | |

| I hope the broadcaster achieves their goals. | |

| I wish to meet the broadcaster in person. | |

| I like hearing the broadcaster’s voice. | |

| I am willing to listen to what the broadcaster says. | |

| I would recommend the broadcaster to friends. |

References

- Hilvert-Bruce, Z.; Neill, J.T.; Sjöblom, M.; Hamari, J. Social motivations of live-streaming viewer engagement on Twitch. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 84, 58–67. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Wu, Q. Research on the influence mechanism and incentive strategy of consumers’ participation willingness in e-commerce live streaming. In Proceedings of the 2022 2nd International Conference on Management Science and Software Engineering (ICMSSE 2022), Chongqing, China, 15–17 July 2022; Atlantis Press: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 842–853. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K.Z.; Benyoucef, M. Consumer behaviour in social commerce: A literature review. Decis. Support Syst. 2016, 86, 95–108. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.Y.; Gan, C.L. Applications of SOR and para-social interactions (PSI) towards impulse buying: The Malaysian perspective. J. Mark. Anal. 2020, 8, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moslehpour, M.; Pham, V.K.; Wong, W.-K.; Bilgiçli, İ. e-Purchase Intention of Taiwanese Consumers: Sustainable Mediation of Perceived Usefulness and Perceived Ease of Use. Sustainability 2018, 10, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.H.; Nicholson, M. A Multidisciplinary Cognitive Behavioural Framework of Impulse Buying: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2013, 15, 333–356. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, X.; Cheah, J.H.; Hollebeek, L.D.; Lim, X.J. Boosting customers’ impulsive buying tendency in live-streaming commerce: The role of customer engagement and deal proneness. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 77, 103644. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, Q.; Khan, J.; Su, Y.; Tong, J.; Zhao, S. Impulse buying tendency in live-stream commerce: The role of viewing frequency and anticipated emotions influencing scarcity-induced purchase decision. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 75, 103534. [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan, S.; Banerjee, R.; Chakraborty, C.; Mittal, M.; Shiva, A.; Ravi, V. A self-congruence and impulse buying effect on user’s shopping behavior over social networking sites: An empirical study. Int. J. Pervasive Comput. Commun. 2021, 17, 404–425. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlovic, N. Herd behaviour in consumer buying decisions in the age of social media—Studies on different influencing aspects in the mobile communications industry. Int. J. Pervasive Comput. Commun. 2021, 17, 404–425. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, J.R.; Hsu, C.W. Live-streaming shopping: The impacts of para-social interaction and local presence on impulse buying through shopping value. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2023, 123, 1861–1886. [Google Scholar]

- Labrecque, L.I. Fostering Consumer–Brand Relationships in Social Media Environments: The Role of Parasocial Interaction. J. Interact. Mark. 2014, 28, 134–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, M. Celebrity Influence: Politics, Persuasion, and Issue-Based Advocacy; University Press of Kansas: Lawrence, KS, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Liao, J. Antecedents of viewers’ live streaming watching: A perspective of social presence theory. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 839629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaveladze, B.T.; Morris, R.R.; Dimitrova-Gammeltoft, R.V.; Goldenberg, A.; Gross, J.J.; Antin, J.; Sandgren, M.; Thomas-Hunt, M.C. Social interactivity in live video experiences reduces loneliness. Front. Digit. Health 2022, 4, 859849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Wu, J.-H.; Li, Q. What drives consumer shopping behaviour in live streaming commerce? J. Electron. Commer. Res. 2020, 21, 144–167. [Google Scholar]

- Zuo, R.; Xiao, J. Exploring Consumers’ Impulse Buying Behaviour in Live Streaming Shopping. In Proceedings of the Fifteenth International Conference on Management Science and Engineering Management, Toledo, Spain, 1–4 August 2021; Xu, J., García Márquez, F.P., Ali Hassan, M.H., Duca, G., Hajiyev, A., Altiparmak, F., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 78, pp. 610–622. [Google Scholar]

- Parboteeah, D.V.; Valacich, J.S.; Wells, J.D. The Influence of Website Characteristics on a Consumer’s Urge to Buy Impulsively. Inf. Syst. Res. 2009, 20, 60–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleine III, R.E.; Kleine, S.S.; Kernan, J.B. Mundane Consumption and the Self: A Social-Identity Perspective. J. Consum. Psychol. 1993, 2, 209–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Chen, L.; Wang, X.; George, B. Not all posts are treated equal: An empirical investigation of post replying behaviour in an online travel community. Inf. Manag. 2018, 55, 890–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.; Cho, H. Fostering Parasocial Relationships with Celebrities on Social Media: Implications for Celebrity Endorsement. Psychol. Mark. 2017, 34, 481–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, K.; Zhang, Q. Influence of parasocial relationship between digital celebrities and their followers on followers’ purchase and electronic word-of-mouth intentions, and persuasion knowledge. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 87, 155–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piron, F. Defining impulse purchasing. ACR N. Am. Adv. 1991, 18, 509. [Google Scholar]

- Verhagen, T.; Van Dolen, W. The influence of online store beliefs on consumer online impulse buying: A model and empirical application. Inf. Manag. 2011, 48, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, T.K.; Cheung, C.M.; Lee, Z.W. The state of online impulse-buying research: A literature analysis. Inf. Manag. 2017, 54, 204–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Gao, Y. Factors driving irrational purchase behavior of live streaming e-commerce: The mediating effect of consumer purchase intention. Randwick Int. Soc. Sci. J. 2023, 4, 818–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongkitrungrueng, A.; Assarut, N. The role of live streaming in building consumer trust and engagement with social commerce sellers. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 543–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Suo, L. Factors affecting Chinese consumers’ impulse buying decision of live streaming E-commerce. Asian Soc. Sci. 2021, 17, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, J.; Jianqiu, Z.; Bilal, M.; Akram, U.; Fan, M. How social presence influences impulse buying behaviour in live streaming commerce? The role of S-O-R theory. Int. J. Web Inf. Syst. 2021, 17, 300–320. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, S. A Study on the Influence of E-commerce Live Streaming on Consumer’s Purchase Intentions in Mobile Internet. In HCI International 2020—Late Breaking Papers: Interaction, Knowledge and Social Media; Stephanidis, C., Salvendy, G., Wei, J., Yamamoto, S., Mori, H., Meiselwitz, G., Nah, F.F.-H., Siau, K., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 12427, pp. 720–732. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, H. Social Identity and Intergroup Relations; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ahearne, M.; Bhattacharya, C.B.; Gruen, T. Antecedents and consequences of customer-company identification: Expanding the role of relationship marketing. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, C.B.; Rao, H.; Glynn, M.A. Understanding the Bond of Identification: An Investigation of its Correlates among Art Museum Members. J. Mark. 1995, 59, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casaló, L.V.; Flavián, C.; Guinalíu, M. Promoting Consumer’s Participation in Virtual Brand Communities: A New Paradigm in Branding Strategy. J. Mark. Commun. 2008, 14, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuenzel, S.; Vaux Halliday, S. Investigating antecedents and consequences of brand identification. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2008, 17, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Liu, Z.; Wei, S.; Liu, Y. Understanding the role of affordances in promoting social commerce engagement. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2021, 25, 287–312. [Google Scholar]

- Stets, J.E.; Burke, P.J. Identity Theory and Social Identity Theory. Soc. Psychol. Q. 2000, 63, 224–237. [Google Scholar]

- Horton, D.; Richard Wohl, R. Mass Communication and Para-Social Interaction: Observations on Intimacy at a Distance. Psychiatry 1956, 19, 215–229. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, A.M.; Perse, E.M.; Powell, R.A. Loneliness, Parasocial Interaction, and Local Television News Viewing. Hum. Commun. Res. 1985, 12, 155–180. [Google Scholar]

- Thorson, K.S.; Rodgers, S. Relationships Between Blogs as EWOM and Interactivity, Perceived Interactivity, and Parasocial Interaction. J. Interact. Advert. 2006, 6, 5–44. [Google Scholar]

- Ballantine, P.W.; Martin, B.A. Forming parasocial relationships in online communities. ACR N. Am. Adv. 2005, 32, 197–201. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, C.-L. How vloggers embrace their viewers: Focusing on the roles of para-social interactions and flow experience. Telemat. Inform. 2020, 49, 101364. [Google Scholar]

- Aw, E.C.-X.; Labrecque, L.I. Celebrity endorsement in social media contexts: Understanding the role of parasocial interactions and the need to belong. J. Consum. Mark. 2020, 37, 895–908. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L.; Lu, Y.; Wang, B.; Chau, P.Y.K.; Zhang, L. Cultivating the sense of belonging and motivating user participation in virtual communities: A social capital perspective. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2012, 32, 574–588. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, L.; Zheng, X.; Lee, M.K.O.; Zhao, D. Exploring consumers’ impulse buying behaviour on social commerce platform: The role of parasocial interaction. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2016, 36, 333–347. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.R.; Chen, F.S.; Chen, D.F. Effect of social presence toward livestream e-commerce on consumers’ purchase intention. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perse, E.M.; Rubin, R.B. Attribution in Social and Parasocial Relationships. Commun. Res. 1989, 16, 59–77. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, R.Y. The value of followers on social media. IEEE Eng. Manag. Rev. 2020, 48, 173–183. [Google Scholar]

- Denghua, Y.; Lidan, G. Para-social interaction in social media and its marketing effectiveness. Foreign Econ. Manag. 2020, 42, 21–35. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H. Keeping up with influencers: Exploring the impact of social presence and parasocial interactions on Instagram. Int. J. Advert. 2022, 41, 414–434. [Google Scholar]

- Beatty, S.E.; Ferrell, M.E. Impulse buying: Modeling its precursors. J. Retail. 1998, 74, 169–191. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, X. How Does Shopping With Others Influence Impulsive Purchasing? J. Consum. Psychol. 2005, 15, 288–294. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, Y.J.; Osman, A.B.; Halim, M.S.B.A.B. Perceived usefulness and trust towards consumer behaviours: A perspective of consumer online shopping. J. Asian Sci. Res. 2014, 4, 541. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.-H.; Chen, C.-W. Impulse buying behaviours in live streaming commerce based on the stimulus-organism-response framework. Information 2021, 12, 241. [Google Scholar]

- Olgun, C. The Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic Fatigue and Social Media Influencers on Consumer-Brand Identification and Purchase Intentions. Ph.D. Thesis, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, OK, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hagerty, B.M.; Lynch-Sauer, J.; Patusky, K.L.; Bouwsema, M.; Collier, P. Sense of belonging: A vital mental health concept. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 1992, 6, 172–177. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Chen, X.; Zhu, P. How do e-commerce anchors’ characteristics influence consumers’ impulse buying? An emotional contagion perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 76, 103587. [Google Scholar]

- Harlow, S.; Chadha, M. Indian entrepreneurial journalism: Building a typology of how founders’ social identity shapes innovation and sustainability. J. Stud. 2019, 20, 891–910. [Google Scholar]

- Zahari, N.H.M.; Azmi, N.N.N.; Kamar, W.N.I.W.A.; Othman, M.S. Impact of live streaming on social media on impulse buying. Asian J. Behav. Sci. 2021, 3, 13–23. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S.S. A factors effecting online social decisions in online consumer behaviour. J. Distrib. Sci. 2020, 18, 67–76. [Google Scholar]

- Wixom, B.H.; Todd, P.A. A Theoretical Integration of User Satisfaction and Technology Acceptance. Inf. Syst. Res. 2005, 16, 85–102. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S.; Singh, N.; Kalinić, Z.; Liébana-Cabanillas, F.J. Assessing determinants influencing continued use of live streaming services: An extended perceived value theory of streaming addiction. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 168, 114241. [Google Scholar]

- Dwiputra, R.C.; Handayani, P.W.; Snnarso, F.P.; Hilman, M.H. The influence of electronic word-of-mouth information quality dimensions on consumer product purchase in online marketplace. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Advanced Computer Science and Information Systems (ICACSIS), Depok, Indonesia, 23–25 October 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Song, J.H.; Zinkhan, G.M. Determinants of Perceived Web Site Interactivity. J. Mark. 2008, 72, 99–113. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, K.; Lu, J.; Guo, L.; Li, W. The dynamic effect of interactivity on customer engagement behaviour through tie strength: Evidence from live streaming commerce platforms. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 56, 102251. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, J.-K.; Tseng, C.-Y. Exploring social influence on hedonic buying of digital goods—online games’virtual items. J. Electron. Commer. Res. 2018, 19, 164–185. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, T.K.; Wang, Y.T.; Lin, K.Y. Enhancing brand loyalty through online brand communities: The role of community benefits. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2022, 31, 823–838. [Google Scholar]

- Farivar, S.; Wang, F.; Yuan, Y. Opinion leadership vs. para-social relationship: Key factors in influencer marketing. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 59, 102371. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, C.; Luo, X.R.; Schatzberg, L.; Sia, C.L. Impact of informational factors on online recommendation credibility: The moderating role of source credibility. Decis. Support Syst. 2013, 56, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, Y.M.; Bae, Y.; Jang, H. Social and parasocial relationships on social network sites and their differential relationships with users’ psychological well-being. Cyberpsychology Behav. Soc. Netw. 2013, 16, 512–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Huang, H. Influence of perceived value on consumers’ continuous purchase intention in live-streaming e-commerce—Mediated by consumer trust. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 74, 103534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Fan, X.; Ji, R.; Jiang, Y. Perceived community support, users’ interactions, and value co-creation in online health community: The moderating effect of social exclusion. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homburg, C.; Müller, M.; Klarmann, M. When does salespeople’s customer orientation lead to customer loyalty? The differential effects of relational and functional customer orientation. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2011, 39, 795–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, H.-H.; Chan, H.-C.; Wei, K.-K.; Zhang, Z. Evaluating information accessibility and community adaptivity features for sustaining virtual learning communities. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2003, 59, 671–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoerner, J. Scaling the web: A parasocial interaction scale for world wide web sites. Advert. World Wide Web 1999, 99, 135–147. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioural research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Meng, B.; Kim, W. Bike-traveling as a growing phenomenon: Role of attributes, value, satisfaction, desire, and gender in developing loyalty. Tour. Manag. 2017, 59, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, D.; Straub, D.; Boudreau, M.-C. Structural Equation Modeling and Regression: Guidelines for Research Practice. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2000, 4, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, G.W.; Lau, R.S. Testing Mediation and Suppression Effects of Latent Variables: Bootstrapping With Structural Equation Models. Organ. Res. Methods 2008, 11, 296–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Lynch, J.G.; Chen, Q. Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and Truths about Mediation Analysis. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, D.A.; Judd, C.M. Estimating the nonlinear and interactive effects of latent variables. Psychol. Bull. Am. Psychol. Assoc. 1984, 96, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Cheng, Q. Live stream and willingness to buy: The interactivity between loneliness and parasocial interaction. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Decision Science & Management, Changsha, China, 7–9 January 2022; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2022; pp. 49–64. [Google Scholar]

- Gunasekara, A.; Udunuwarage, M.; Senevirathne, R.E.; Gregory, V.; Jayasuriya, N. The effect of parasocial interaction on impulse buying in the field of marketing. Int. J. Pervasive Comput. Commun. 2021, 17, 404–425. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, M.; Zhao, Y.C.; Song, S.; Zhang, X.; Wu, D.; Li, J. How vicarious learning increases users’ knowledge adoption in live streaming: The roles of parasocial interaction, social media affordances, and knowledge consensus. Inf. Process. Manag. 2024, 61, 103599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, L.; Tang, H.; Zhang, Y. Electronic word-of-mouth and consumer purchase intentions in social e-commerce. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2020, 41, 100980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.-R.; Lu, I.-W.; Chen, J.H.; Farn, C.-K. Investigating consumers’ online social shopping intention: An information processing perspective. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 54, 102189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, H.; Paruthi, M.; Islam, J.; Hollebeek, L.D. The role of brand community identification and reward on consumer brand engagement and brand loyalty in virtual brand communities. Telemat. Inform. 2020, 46, 101321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khine, P.H.H.; Dreamson, N. Cultural understanding of live streaming e-commerce in Asian markets. Int. J. Electron. Commer. Stud. 2023, 14, 001–024. [Google Scholar]

- Mai, T.D.P.; To, A.T.; Trinh, T.H.M.; Nguyen, T.T.; Le, T.T.T. Para-social interaction and trust in live-streaming sellers. Emerg. Sci. J. 2023, 7, 744–754. [Google Scholar]

- Chuang, Y.W. Promoting consumer engagement in online communities through virtual experience and social identity. Sustainability 2020, 12, 855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, G.-Y.; Pham, T.T.L.; Cheng, T.; Teng, C.-I. How online gamers’ participation fosters their team commitment: Perspective of social identity theory. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 52, 102095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, G.; Fu, T.; Choi, T.-M.; Kumar, A.; Tan, K.H. Price and Quality Strategy in Live Streaming E-Commerce With Consumers’ Social Interaction and Celebrity Sales Agents. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2022, 71, 4063–4075. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, M.L.; Leung, W.K.; Aw, E.C.-X.; Koay, K.Y. “I follow what you post!”: The role of social media influencers’ content characteristics in consumers’ online brand-related activities (COBRAs). J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 66, 102940. [Google Scholar]

- Khoi, N.H.; Le, A.N.H.; Dong, P.N. A moderating–mediating model of the urge to buy impulsively in social commerce live-streaming. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2023, 60, 101286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Park, M. The effect of live commerce’s para-social interaction on satisfaction with the experience—Focused on the moderated mediation effect of self-image congruity. Res. J. Costume Cult. 2020, 28, 719–737. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.; Li, Q.; Jian, H. Based on social identity theory and emotional infection theory, this paper explores the influence and mechanism of online group purchasing behavior. In Proceedings of the 2024 9th International Conference on Social Sciences and Economic Development (ICSSED 2024), Beijing, China, 22–27 March 2024; Atlantis Press: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 703–708. [Google Scholar]

- Nadroo, Z.M.; Lim, W.M.; Naqshbandi, M.A. Domino effect of parasocial interaction: Of vicarious expression, electronic word-of-mouth, and bandwagon effect in online shopping. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 78, 103746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, P.B.; Mariana, P.; Delgado, C.J.M.; Santos, J.D. A conceptual approach to understanding the customer experience in e-commerce: An empirical study. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 19, 1943–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xueyun, Z.; Yiyang, F. Para-social interaction in live streaming economy: Evidence from Douyu platform. J. Financ. Econ. 2023, 49, 136–148. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.B.; Zhang, Z.P.; Chang, Y.; Li, T.G.; Hou, R.J. Effect of WeChat interaction on brand evaluation: A moderated mediation model of para-social interaction and affiliative tendency. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 64, 102812. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).