1. Introduction

The rise of live e-commerce can be attributed to the rapid advancement of Internet technology, which has provided consumers with a novel shopping experience characterized by interactivity and real-time engagement. However, this emerging shopping paradigm has also given rise to numerous challenges, particularly the proliferation of impulsive purchasing behavior. As live shopping gains in popularity, consumer dissatisfaction resulting from such spontaneous purchases is increasing. This not only leads to a significant number of consumers experiencing post-purchase regret but also instigates numerous consumer disputes and fosters social discontent [

1]. Within this context, key opinion leaders (KOLs), pivotal figures in live e-commerce, wield substantial influence over consumers’ purchasing decisions through their verbal and non-verbal actions [

2]. When KOLs overstate the merits of products or employ inappropriate marketing strategies, they may exacerbate consumers’ tendencies toward impulsive buying and disrupt the social and economic order [

3]. Relevant data indicate an increasing trend in complaints associated with live shopping, highlighting the numerous issues prevalent in this domain. This severely compromises the consumer shopping experience and impedes the healthy development of the live e-commerce sector [

4].

In live shopping environments, the psychological interaction between KOLs and users is crucial. Users assimilate the information disseminated by KOLs while viewing live broadcasts, forming initial cognitive and emotional responses to products that directly steer their purchasing decisions. Impulsive purchasing behavior typically stems from a transient emotional impulse without adequate planning, whereas purposeful purchasing behavior occurs when consumers have a defined purchasing plan and objective. Both forms of buying behavior not only reflect individual consumption patterns but are also closely linked to broader social and economic dynamics. Impulsive buying behavior can lead to resource wastage and an increase in consumer debt, while purposeful buying behavior is comparatively more rational and planned.

To gain an in-depth understanding of user purchasing behavior in live e-commerce, this study introduces the PAD emotion theory, and the SOR model, which describes emotional states and classifies emotions into three dimensions: pleasure, arousal, and dominance [

5]. Pleasure refers to the extent of happiness an individual experiences when facing external stimuli, such as enjoyment during a meal; arousal refers to the level of excitement, like that induced by hearing exciting music; and dominance reflects an individual’s sense of control in specific situations, such as decision-making in familiar environments. In live e-commerce, consumers’ purchasing behavior is often influenced by these three combined emotions [

6]. The SOR model explains the mechanism of individual behavior generation. This model posits that external stimuli (S) trigger changes in an individual’s internal mental state (O), ultimately leading to behavioral responses (R). For instance, an appealing advertisement may arouse excitement and interest, thereby prompting product purchases. In live e-commerce, KOLs’ characteristics and behaviors serve as external stimuli, influencing consumers’ emotional states (organism) and, subsequently, their purchasing behaviors (reaction). This study posits that KOLs’ information source characteristics—professionalism, popularity, charisma, and entertainment—act as external stimuli. These characteristics influence consumers’ pleasure, arousal, and trust, thereby shaping their impulsive and purposeful purchase intentions. Existing studies predominantly focus on KOL characteristics’ direct influence on purchase intention. Conversely, this study innovatively integrates the PAD emotion theory and the SOR model to deeply analyze the mediating role of emotional variables, addressing the theoretical gap in this field.

This study aims to achieve the following objectives: (1) to examine how KOLs’ source characteristics—professionalism, popularity, charisma, and entertainment—influence users’ pleasure, arousal, and trust; and (2) to investigate how these mood changes impact users’ impulsive and purposeful purchase intentions. The contributions of this study are reflected in three aspects: first, methodological innovation. Data-mining techniques capture real-time live-broadcast pop-up data, and machine-learning models measure user interaction characteristics. This approach assesses how user interactions and emotional states potentially impact purchasing behaviors and offers a novel perspective for live broadcasting research, being more scientific and efficient. Second, theoretical innovation is achieved. Using the SOR model and PAD emotion theory, we systematically examine the mechanism by which KOLs influence users’ purchase intentions and the internal logic in live e-commerce. This theoretical exploration holds significant academic value and offers valuable practical insights for the sustainable development of the live e-commerce industry. Third, practical significance is demonstrated. This study reveals the complex mechanism by which KOL features influence users’ emotions and purchase intentions, offering a key basis for optimizing live broadcast marketing strategies. By deeply understanding the relationship between KOL features and consumers’ emotions and purchase behaviors, enterprises and KOLs can better formulate marketing strategies, enhance live-marketing effectiveness, increase consumer engagement, and thereby promote the healthy development of the live e-commerce industry.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Consumer Behavior in Live Shopping

Live shopping, an emerging shopping method, has developed rapidly in recent years. Its unique interactivity and real-time nature have attracted a large number of consumers. Related studies have shown that impulsive buying behavior is more common among consumers in live shopping. A survey by Xu and Huang et al. (2014) found that the incidence of impulsive buying behavior in live shopping is significantly higher than that in traditional e-commerce. This is mainly due to limited-time offers and interactive lucky draws in live streaming that easily stimulate consumers’ desires to make instant purchases [

7]. However, different studies have not yet agreed on the triggers and influencing mechanisms of impulsive buying behavior. Liu et al. (2013) pointed out through experimental research that the way of displaying products in live broadcasts and the language style of anchors directly impact impulsive buying behavior. However, their study focused more on the content of live broadcasts themselves and did not explore the personal influence of the anchors in depth [

8]. In contrast, Meng’s (2012) study emphasized the key role of KOLs, arguing that their personal charisma and professionalism are important factors influencing impulsive buying behavior. However, the specific path and depth of their role are not sufficiently explored [

9]. These studies provide a multi-faceted perspective for understanding consumer behavior in live shopping but still need further integration and deepening. Additionally, while some studies have focused on the negative impacts of impulsive buying, such as resource waste and consumer regret, relatively few studies have explored how to guide consumers to make rational purchases. Most existing studies on consumer behavior in live shopping focus on the triggers of impulsive buying, while the motivation and decision-making process behind purposeful buying behavior remain underexplored. Liu et al.’s (2013) study shows that factors such as consumers’ shopping goals, budget plans, and product demand significantly impact purposeful buying behavior. However, their study does not deeply analyze special factors in the live-streaming environment, such as the atmosphere of the live-broadcasting room and the guidance of KOLs, on purposeful purchasing [

8]. This provides room for further exploration in this study.

2.2. Key Opinion Leader (KOL)

KOLs (key opinion leaders), initially proposed by Lazarsfeld et al., typically refer to individuals with expertise in a specific field and broad influence. Through their influence and expertise, they assist brands in educating consumers and guiding purchasing behavior [

10]. Based on varying characteristics, KOLs can be categorized into types such as professional KOLs, social KOLs, and entertainment KOLs. Ma et al. (2022) showed that professional KOLs provide consumers with authoritative product information and advice using their expertise, thereby enhancing consumers’ purchasing confidence [

11]. For example, in beauty live streams, professional KOLs can explain product ingredients, efficacy, and usage in detail to help consumers make more informed purchasing decisions [

12]. Entertainment KOLs attract consumers’ attention and stimulate purchasing interest through humorous live-streaming styles and interactive methods. According to Meng (2012), the live-streaming style and interaction of entertainment KOLs effectively attract consumers’ attention and stimulate their purchase interest [

9]. Additionally, social KOLs build trust through close interaction and emotional connections with their fans, thereby influencing purchasing behavior. Zhang (2021) pointed out that social KOLs have higher fan loyalty, making their recommended products more likely to be accepted and purchased by fans [

13]. However, existing studies have not yet reached a unified understanding of the characteristics of different KOL types and their influence mechanisms on consumer purchasing behavior. Some studies suggest that the influence of professional KOLs mainly reflects product professionalism and credibility, whereas entertainment KOLs’ influence stems from broadcast entertainment value and attractiveness. However, some studies indicate that the influence of different KOL types may vary depending on factors such as product type and consumer characteristics. Additionally, research is lacking on how KOL influence evolves over time and interacts with live-streaming platform rules and culture. Most existing studies focus on KOLs’ positive influence in driving consumer purchasing behavior but pay less attention to their potential negative impact. Against the backdrop of live e-commerce’s rapid growth, some KOLs may exaggerate product effects or use improper marketing methods to achieve short-term sales goals, thereby harming consumer rights and affecting the industry’s healthy development. Thus, in-depth studies of KOL influence and its mechanisms are crucial for optimizing live e-commerce marketing strategies, enhancing consumer experiences, and promoting industry standardization.

2.3. SOR-PAD Theoretical Framework

To explore the internal mechanism of consumer behavior in live e-commerce, this study innovatively integrates the stimulus–organism–response (SOR) model with the pleasure–arousal–dominance (PAD) affective theory to construct a comprehensive analytical framework. As a theoretical tool for explaining individual behavior, the SOR model focuses on the interconnections between external stimuli, internal psychological states, and behavioral responses. In live e-commerce scenarios, the characteristics and behaviors of key opinion leaders (KOLs) constitute a key external stimulus source, influencing consumers’ psychological states and shaping their purchase decisions [

14]. Zhang’s (2018) empirical study based on the SOR model showed that external stimulus elements, such as interactive design and product display methods in live broadcasts, can significantly influence consumers’ purchase decision-making process [

15]. For example, KOL features such as professionalism and personal charisma, as typical external stimuli, can stimulate consumers’ trust and pleasure, prompting them to develop purchase intentions. Chen’s (2018) research further confirmed that KOL features and behaviors influence consumers’ purchase behaviors by modulating their psychological state [

16].

PAD emotion theory explains consumer behavior from an emotional perspective, subdividing emotional states into three dimensions: pleasure, arousal, and dominance. Pleasure corresponds to the consumer’s happy experiences during the shopping process, arousal reflects the consumer’s degree of excitement, and dominance represents the consumer’s sense of control over the shopping process [

6]. Weinberg et al.’s (1982) empirical study showed that consumers’ pleasure and surprise during live shopping are positively correlated with purchase willingness. It also revealed that high emotional arousal increases the likelihood of impulsive consumption, while enhanced dominance improves consumers’ control over shopping decisions, thereby boosting their purchasing confidence [

17]. Previous studies have revealed potential interactions among pleasure, arousal, and dominance [

17]. For instance, Hui and Bateson (1991) found a positive and direct relationship between dominance and pleasure in service settings [

18]. Chang et al. (2014) found that dominance positively influences arousal levels, which indirectly enhance pleasure [

19]. In contrast, Koo and Lee’s (2011) study of online and offline shopping behaviors showed that trust, reflecting dominance, directly enhances arousal levels, which further positively affect pleasure [

20]. Given this, the present study will empirically test the interactions among the three emotional dimensions of the PAD theory.

Our literature review reveals that despite existing studies achieving certain results in consumer behavior and KOL influence in live e-commerce, notable research gaps persist. First, while many studies focus on KOLs’ direct influence, the intermediary mechanism by which KOLs affect purchasing behavior through consumers’ emotional changes remains underexplored. Second, limited research has examined differences in impulsive and purposive buying behaviors and their underlying mechanisms in live shopping. Additionally, existing studies are hampered by limitations in data collection methods and a lack of real-time data mining and analysis, making it challenging to capture consumers’ immediate emotional responses during live streaming. To address these gaps, this study integrates the SOR model and PAD emotion theory to explore how KOL characteristics influence consumers’ emotions and subsequent purchase intentions. Simultaneously, this study employs a mixed-method approach by combining real-time pop-up text mining and questionnaire surveys, thereby providing a more comprehensive understanding of consumer behavior in live e-commerce. This research design offers deeper theoretical insights while providing valuable guidance for the live e-commerce industry’s practice.

3. Research Design

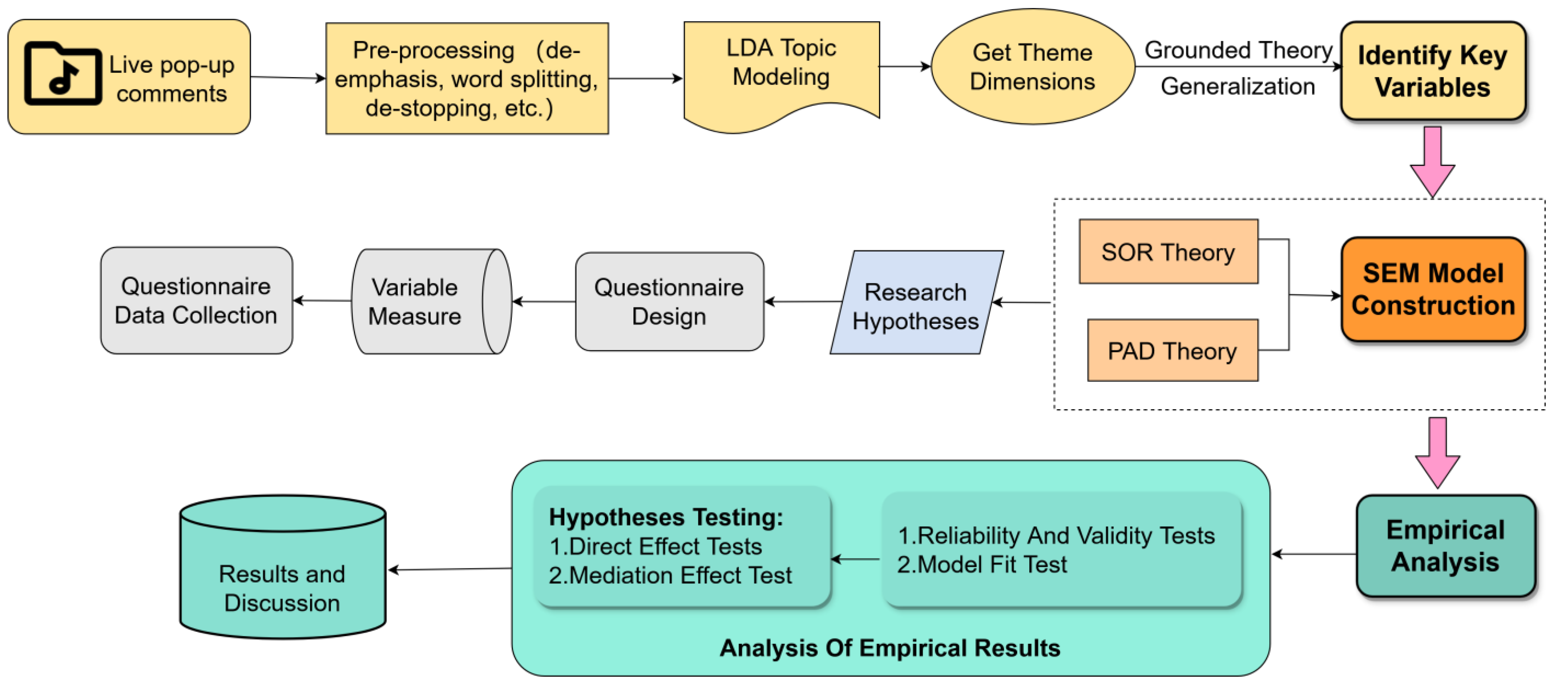

According to the research problem, the following research design was implemented: Firstly, web crawler technology was utilized to collect users’ online comments in KOL bandwagon live-broadcasting rooms, and subsequent preprocessing tasks, including comment screening, de-emphasis, word splitting, and removal of stop words, were conducted. Subsequently, the LDA model was employed to perform topic modeling on the pop-up comments to extract the thematic dimensions. Secondly, the SEM model was constructed by integrating SOR and PAD theories, based on the extracted thematic dimensions, and, drawing on prior research regarding the SEM model, research hypotheses and a questionnaire were formulated, and questionnaires were distributed to consumer users via KOL private domain groups to specifically measure the factors influencing users’ consumption behavior. Finally, empirical research was conducted to validate the hypotheses, assessing the impact of live banding KOLs on inducing consumer behavior. The specific research framework is depicted in

Figure 1.

4. Research Hypotheses

4.1. Study 1: LDA Thematic Modeling to Identify Key Variables

4.1.1. Data Sources

This study’s data source comprises two parts: first, live pop-up texts collected via web-crawling from China’s Jitterbug short-video platform; second, data on users’ purchasing behaviors and intentions gathered through questionnaires. With 160 million daily active users in 2024, this short-video platform is one of China’s most significant live e-commerce platforms. According to the “Top 100 Chinese Anchors with Goods in 2024” [

21] released by iiMedia Research in June 2024, this study selected 36 high-quality anchors as research objects (see

Table 1). These anchors, serving as industry benchmarks, demonstrated outstanding performance in fan volume and sales ability, ensuring high representativeness and typicality. This study collected pop-up texts from 128 live broadcasts, totaling over 106,000 items.

4.1.2. Data Preprocessing

To enhance data analysis accuracy and efficiency, this study conducted several preprocessing steps on the collected pop-up text data.

(1) The first preprocessing step involves removing special characters and emoticons, which can interfere with subsequent text analysis. For example, a raw pop-up text might read as follows: “This product is fantastic!

![Jtaer 20 00108 i001]()

Check it out @ZhangSan”. After this step, the text becomes as follows: “This product is fantastic Check it out ZhangSan”. The second step is to eliminate repetitive phrases and short texts. Repetitive phrases (e.g., “haha” and “huh”) and short texts (less than 2 characters) typically lack substantive information, hindering effective topic extraction and sentiment analysis. For instance, the repeated phrase “hahahahaha” will be removed. The third step involves filtering based on text length by setting the threshold to 2 characters to eliminate overly short texts. For example, the text “good” is removed due to insufficient information conveyance.

(2) Text segmentation is the subsequent preprocessing step, performed using the Jieba Segmentation Tool. This tool recognizes Chinese word boundaries and splits continuous text into meaningful lexical units.

(3) Finally, stop words are removed. Stop words are common meaningless words such as “the”, “ah”, “what”, etc., which are frequently used in text mining but are typically excluded, as they do not contribute to analyzing key information, such as topic and sentiment. Create a stop-word list containing these common words and remove them from the text. These preprocessing steps yield cleaner, more useful data, providing a solid foundation for subsequent topic modeling and sentiment analysis.

4.1.3. LDA Topic Modeling

The preprocessed text data are used for topic modeling. In this study, the LDA (Latent Dirichlet Allocation) model is used for topic extraction. LDA is a topic-modeling technique that extracts potential topics from large-scale text data. LDA is chosen because it reveals the hidden topic structure in text data, making it suitable for mining complex text data such as live pop-ups. The LDA model identifies the main themes users focus on during live broadcasts. When applying the LDA model, the number of topics must be preset. Traditionally, perplexity and consistency are the two main criteria for evaluating the reasonableness of the number of topics [

22]. However, the developer of the Gensim library has questioned the reliability of perplexity as a metric for evaluating LDA model efficacy in a blog post, sparking extensive academic discussions on selecting appropriate metrics for topic model performance [

23]. Given that grounded theory emphasizes natural emergence rather than predetermined concepts or categories, this study adopts the local enumeration method to determine the optimal number of topics based on actual effects [

24]. In practice, pop-up comments are selected as the first stage of open coding. The optimal number of themes is determined as 11 by comparing and analyzing the clustering effects of theme numbers from 1 to 15. After eliminating low-frequency words (frequency < 10), the ONLINE mode is selected, and 10 training iterations are performed to complete model fitting and theme extraction. This process yields specific theme (concept) classifications and their weights. Finally, six core categories are refined through manual coding and theme fusion (see

Table 2).

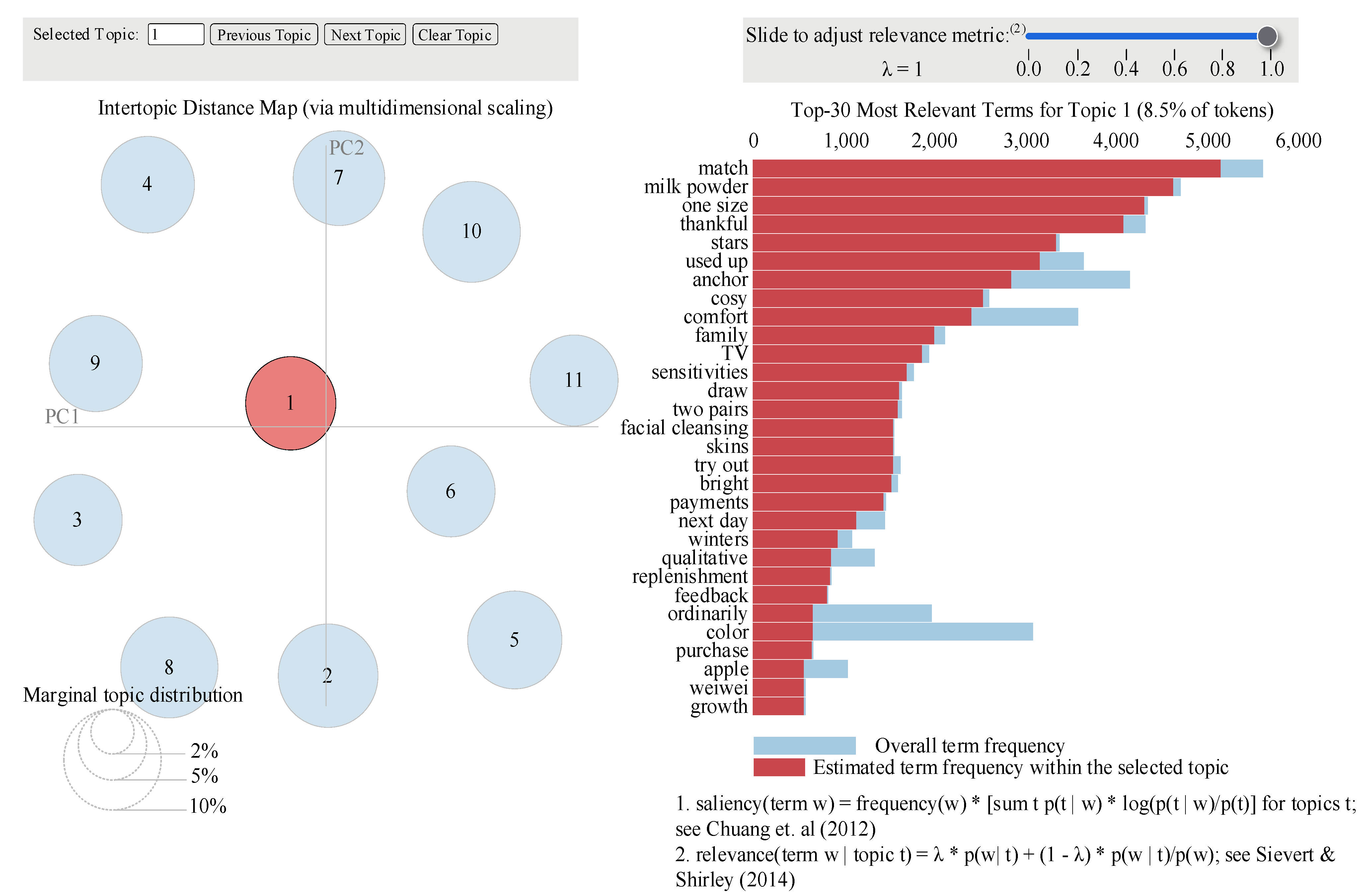

To better observe the effectiveness of topic modeling, this study uses Topic 1 as a case study, visualized using the pyLDAvis library.

Figure 2 comprises two main panels. The left circular graph displays the distribution of different topics; each circle represents a topic, with size indicating the topic’s proportion in the corpus, and distance reflecting similarity between topics. The right bar graph shows the most relevant words under each topic; bar height indicates word importance in the topic, and color reflects the word’s frequency in the corpus. The parameter λ (lambda) in the top right regulates keyword relevance to the topic. When λ approaches 0 (0 ≤ λ ≤ 1), topic-unique words have higher relevance. When λ approaches 1, frequently appearing words have greater relevance.

4.2. Study 2: Theoretical Hypotheses

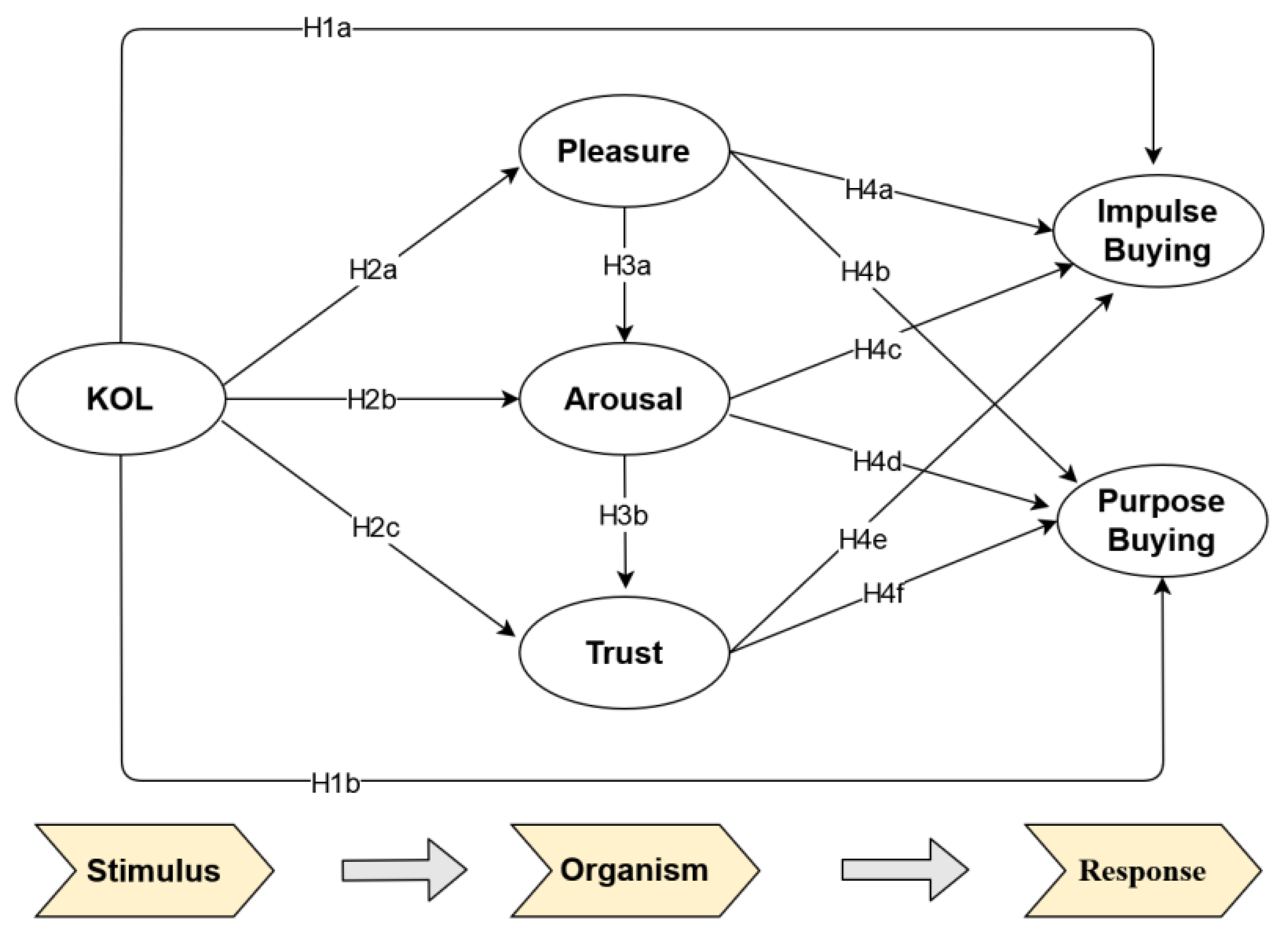

Building on Study 1’s results, this study innovatively integrates the SOR model and PAD emotion theory to develop a comprehensive framework for analyzing how key-opinion-leader (KOL) characteristics influence users’ purchasing behavior. Specifically, the PAD theory posits that pleasure, arousal, and trust dimensions indirectly affect purchase intentions by influencing users’ internal mental states (i.e., the “organism” component of the SOR model). To visualize this conceptual mapping, a detailed schematic diagram (

Figure 3) was developed to illustrate the interconnections among KOL characteristics, emotional responses, and purchase behaviors. KOL characteristics—professionalism, popularity, charisma, and entertainment—act as external stimuli (corresponding to the SOR model’s “stimulus” element) and significantly influence users’ purchase intentions. As external stimuli, these features significantly influence users’ emotional states. Emotional responses, including pleasure, arousal, and trust, align with the three core dimensions of PAD emotion theory and form the key part of the SOR model’s “organism” component. They accurately reflect the internal psychological changes triggered by users’ exposure to KOL features. Purchasing behavior is ultimately reflected in users’ purchase intentions, including impulsive and purposeful purchases, both categorized as “reaction” elements in the SOR model. Through this mapping, the study clarifies how KOL characteristics influence emotional responses and indirectly shape purchasing behaviors, offering a comprehensive theoretical explanation for understanding consumer behaviors in live e-commerce.

4.2.1. Hypothesis on the Influence of KOLs on Willingness to Consume (S-R)

Key opinion leaders (KOLs) are individuals active in interpersonal communication networks who frequently provide information, opinions, or suggestions to others, influencing them. They are characterized by professionalism, product involvement, interactivity, and visibility [

9,

10]. Academic research on KOLs in live shopping predominantly examines their characteristics, including professionalism, product involvement, interactivity, high visibility, entertainment, authenticity, and visibility, to determine their impact on consumer behavior, yet no unanimous conclusion has been reached [

10,

27]. Social-level factors significantly shape consumer behavior, with reference groups, family structure, and individual social roles being particularly influential. Among these reference groups, KOLs exert significant influence over individual consumption choices [

28]. As product adopters, KOLs serve as role models for other consumers, effectively driving purchasing behavior [

29]. For instance, in advertising, businesses often leverage celebrities as spokespeople to build emotional connections with audiences, thereby stimulating consumer purchasing desire. KOLs possess strong information evaluation, screening, and interpretation skills, enabling them to provide high-quality product-related information and reduce consumer information asymmetry. Hence, when KOLs recommend products, they are more likely to arouse consumers’ purchase intention [

30]. Thus, we propose the following hypotheses:

H1a. KOLs have a significant positive effect on users’ purposeful purchasing.

H1b. KOLs have a significant positive influence on users’ impulsive purchasing.

4.2.2. Hypotheses on the Influence of KOLs on Purchase Sentiment (S-O)

Traditional webcasting seeks entertainment rewards, and e-commerce live broadcasting, as a novel live marketing form, is naturally no less entertaining. Zhang et al. noted that webcasting, with its pan-entertainment characteristic, awakens audience pleasure through interactivity, entertainment, and mobility [

15]. Entertainment in webcast shopping aims to inspire or stimulate consumers to achieve a psychological state of satisfaction and pleasure [

31]. Chen et al. showed that webcasting entertainment significantly impacts consumers’ purchase mood and intention [

16], and strengthens the emotional bond between KOLs and consumers [

12]. Thus, entertainment in live webcast shopping—such as talk shows, singing, and lucky draws—affects consumers’ emotional and cognitive responses. Meanwhile, KOLs, characterized by professionalism and popularity, offer consumers efficient, valuable, and targeted services [

32]. When the platform’s products and services meet consumers’ personalized needs during live broadcasts, consumers experience arousal and pleasure, leading to trust generation [

33]. Liu et al. also noted that KOLs can respond promptly to consumer questions. Communication and information exchange among consumers stimulate emotional responses, and good interaction fosters positive emotions, though final results remain unconfirmed [

33]. Consequently, this study examines whether, during live streaming, KOLs positively impact audience arousal, pleasure, and trust perception through pop-ups, explanations, and comprehensive live interactions. It also investigates whether users’ purchasing emotions influence purposeful or impulsive purchasing behaviors.

E-commerce live broadcasts are sales-oriented, leveraging entertainment, game PK, and visual elements to stimulate users. This process imparts product knowledge, awakens emotions, and generates pleasant feelings. As information processors, KOLs bridge product information and user transmission. Consumer trust in KOLs naturally arises from this interaction. KOLs maintain long-term focus on specific products, demonstrating high product involvement. They accumulate knowledge and experience, enhancing their professionalism and earning consumer trust [

34]. Based on the above, we propose the following hypotheses:

H2a. KOLs have a significant positive effect on arousal perception.

H2b. KOLs have a significant positive effect on pleasure perception.

H2c. KOLs have a significant positive effect on trust perception.

4.2.3. Buying Emotions: The Influential Relationship Between Pleasure, Arousal, and Trust (O)

Emotion is a strong and profound affective state that arises during an individual’s cognitive interaction with the external world [

17]. It has garnered extensive attention in the academic literature as a key manifestation of attitudes toward the external world. Emotions can permeate an individual’s mental state and drive corresponding behavioral adjustments [

35]. Jacob et al.’s study revealed that external factors can stimulate emotional or cognitive responses, thereby driving avoidance or convergence behavioral strategies [

35]. In consumer behavior research, emotional responses to external stimuli primarily include pleasure and arousal [

17]. Arousal refers to the excitement and thrill induced by external stimuli, whereas pleasure refers to the satisfaction and pleasure derived from them [

17]. Notably, arousal and pleasure are closely correlated, with high arousal levels generally enhancing pleasure [

33]. Koo et al. (2010) further demonstrated a positive correlation between consumer arousal intensity and pleasure enhancement [

27]. In online shopping contexts, Rose’s study confirmed that positive consumer emotions and satisfaction enhance perceived trust [

36].

However, in-depth interviews with key opinion leaders revealed that live streaming typically follows a specific process: entertainment diversion (stimulating pleasure)—product introduction (triggering arousal)—leading to ordering (building trust and driving purchase decisions). This process illustrates how live streaming influences consumer purchasing behavior through emotional engagement strategies. Based on this, we propose the following hypotheses:

H3a. Pleasure perception has a significant positive effect on consumer arousal.

H3b. Arousal has a significant positive effect on consumer trust perception.

4.2.4. Hypothesis on the Influence of Purchase Sentiment on Purchase Intention (O-R)

This study classifies users’ purchasing intention into impulsive and purposeful categories. In live webcast shopping, purposeful buying refers to selective viewing of live shopping with the planned goal of purchasing a specific product. Prior studies, such as those by Koo et al., have demonstrated that pleasurable emotions significantly impact consumer purchase intention [

27]. Similarly, Chang et al.’s study revealed the positive impact of perceived trust on consumer purchase intention [

37]. Liu et al.’s study further showed that arousal and pleasurable emotions can motivate impulsive buying behavior [

33]. Wang’s study also supports the positive effect of pleasure and arousal emotions on online consumers’ purchase intention [

38], indicating that stronger external stimuli trigger greater purchase intention. This aligns with the observation that positive emotions reflect consumers’ good state of mind during shopping, thereby promoting their purchasing behavior.

Specifically, pleasure typically reflects consumers’ enjoyment of products or satisfaction with prices and services, thereby stimulating a strong willingness to buy. Arousal indicates that the product has successfully attracted consumers’ attention, becoming a key driver of their purchase behavior. Xu and Huang’s study explored how price discounts impact consumers’ impulse purchases, showing that discounts effectively stimulate emotions, enhance arousal, and strengthen purchase intentions [

7]. Chen noted that live broadcasting involves symbolic interaction, where elements like KOLs, audiences, pop-ups, and scenes reflect people’s inner needs [

39]. For instance, Hsu et al. argued that website icons, page design, advertisement content, font selection, and video effects collectively shape website quality experiences, significantly impacting consumers’ pleasure and arousal emotions [

40]. Businesses can enhance purchase intention by optimizing website quality to attract consumers [

40]. These symbolic elements not only enrich the interactive nature of live shopping but also profoundly influence users’ buying emotions and decision-making processes. Based on this, we propose the following hypotheses:

H4a. Pleasure perception has a significant positive effect on purposeful purchases.

H4b. Pleasure perception has a significant positive influence on impulsive purchases.

H4c. Arousal perception has a significant positive effect on purposeful purchases.

H4d. Arousal perception has a significant positive effect on impulsive purchases.

H4e. Trust perception has a significant positive effect on purposeful purchases.

H4f. Trust perception has a significant positive effect on impulsive purchases.

5. Questionnaire

5.1. Questionnaire Design

A questionnaire was constructed to validate the topic modeling results and further gather users’ perceptions and purchase intentions regarding these topics. The questionnaire comprises two sections. The first section includes six latent variables: KOL behavioral characteristics during live streaming, user emotional responses (pleasure, arousal, and trust), and factors influencing purposive and impulsive purchases. To ensure the scale’s reliability and validity, all measurement items originate from existing studies and established domestic and international scales, as detailed in

Table 3. Specifically, the KOL measurement scale is derived from Meng Fei’s study, assessing professionalism, entertainment, popularity, and charisma [

9]. The emotional component’s arousal and pleasure-response design primarily references Koo and Ju [

27] and Donovan and Rossiter [

41]. The trust measurement scale is adapted from Ridings’ study [

42], while impulsive and purposive buying measurements refer to Liu [

8]. The second section collects respondents’ basic information, including gender, age, and location, as detailed in

Table 3. The questionnaire was sent to e-commerce experts for review and subsequently revised based on their feedback. The initial version underwent pre-testing with 50 respondents and was refined based on the results to produce the final questionnaire.

5.2. Questionnaire Data Collection

To ensure data relevance and accuracy, the questionnaire was distributed to members of the KOL Private domain WeChat group in live pop-up sessions; these members are all product-purchasing loyal users. During the distribution process, 600 questionnaires were distributed, and 600 were successfully recovered. To ensure data quality for the final analysis, questionnaires with excessively short completion times were excluded. Specifically, questionnaires completed in less than one minute were deemed invalid due to potential impacts on data accuracy. After screening, 424 valid questionnaires were obtained, resulting in a 70.6% validity rate. The sample data exhibit youthfulness and urbanization, aligning with the profile of short-video users. According to AiMedia Consulting, 58% of webcasting shoppers are male, and 42% are female. Within this group, consumers aged 30–50 drive over 80% of purchases. Notably, live e-commerce shoppers are primarily located in Tier 1 and 2 cities, with Tier 2 accounting for 42%. Live e-commerce also positively impacts the economic development of second- and third-tier cities [

43]. This study’s demographic data align closely with these trends, ensuring reliability. To further enhance transparency and reproducibility, detailed records of respondents’ demographic characteristics were maintained, including age, gender, region, education level, occupation, and online-shopping age (see

Table 4). This information helps us better understand the behavioral differences among diverse user groups in live shopping and provides valuable references for future research.

In summary, this study chose the LDA model due to its effectiveness in uncovering latent thematic structures in large-scale text data, as is crucial for analyzing user behavior and emotions during live broadcasts. By contrast, SEM (Structural Equation Modeling) is a robust statistical method for validating complex variable relationships. SEM was selected for its capability to simultaneously examine multiple variable path relationships, making it ideal for validating the relationship between emotions and purchase intentions. The integration of these methods offers a comprehensive and in-depth analytical framework for the study.

6. Results

6.1. Reliability and Validity Tests

In the reliability and validity assessment, SPSS 23.0 and AMOS 26.0 were used to rigorously evaluate the scale, ensuring the credibility and accuracy of the research data. Specifically, Cronbach’s alpha was used to quantify the consistency of survey items. This metric ranges from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating stronger inter-item consistency. Additionally, Construct Reliability (CR) and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) were used to assess scale reliability and convergent validity, respectively. Following Fornell and Larcker (1981) [

44], CR should exceed 0.6, and AVE should exceed 0.5. The current study’s results fully met these criteria, demonstrating that the scale possesses good reliability and validity.

Factor loading analysis results (

Table 5) indicate that most measures showed high correlation with latent variables, with loadings exceeding 0.7. This suggests that these indicators effectively represent the corresponding latent variables [

45]. However, some indicators (e.g., B1 and D4) had factor loadings below this threshold and were excluded. This decision followed the criterion of excluding indicators with factor loadings below 0.7, ensuring scale precision and validity, and establishing a robust foundation for subsequent analysis.

Furthermore, discriminant validity was rigorously assessed. Assessing discriminant validity is crucial for ensuring the rationality and scientific rigor of the research’s scale design. By delineating clear boundaries between latent variables, it confirms that the scale effectively differentiates between distinct constructs, avoiding conceptual confusion from high inter-variable correlations and ensuring research conclusion accuracy. The discriminant validity assessment confirmed that each latent variable independently reflects its intended conceptualization, which is essential for deeply understanding the research question and accurately interpreting the data.

The results (

Table 6) indicate that all latent variables’ AVE values exceed 0.5, confirming sufficient discriminant validity. Specifically, discriminant validity was assessed by comparing the square root of each latent variable’s AVE with inter-variable correlation coefficients. In the results’ presentation, the diagonal displays the square root of each latent variable’s AVE, while off-diagonal positions show inter-variable correlation coefficients. The table clearly shows that the square root of each latent variable’s AVE exceeds the correlation coefficients, strongly confirming the questionnaire’s scientific and reasonable design. This indicates that the questionnaire effectively differentiates between constructs with distinct statistical differences. This not only supports the study’s depth but also ensures the credibility and validity of the findings.

6.2. Model Fitting Test

This study employed Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) to test the research hypotheses. The model’s fit to the data was assessed using a series of metrics presented in

Table 7. The chi-square degrees-of-freedom ratio (χ

2/df) was 1.719, within the recommended range of 1.00 to 3.00. Other fit indices also showed strong performance: the goodness-of-fit index (GFI) was 0.921, the comparative fit index (CFI) was 0.966, the normed fit index (NFI) was 0.923, and the incremental fit index (AGFI) was 0.903. All values surpassed the recommended threshold of 0.90. The Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) was 0.041, below the recommended threshold of 0.08. Collectively, these metrics indicate a good fit of the model to the data. For metrics like GFI, higher values indicate a better model fit, whereas lower RMSEA values suggest smaller fitting errors. A good model fit provides a reliable analytical framework for testing research hypotheses and underpins a deeper understanding of the relationship between KOL features and users’ purchasing behavior.

6.3. Hypothesis Testing

6.3.1. Direct Effect Test

Analysis results showed (

Table 8) that KOL characteristics significantly affected impulsive purchase intention (H1b, β = 0.202,

p < 0.001), but not purposeful purchase intention (H1a, β = 0.02,

p = 0.718). This aligns with the SOR model and PAD emotion theory, indicating that external stimuli (KOL characteristics) can influence behavioral responses (impulse buying) via affective responses (pleasure, arousal, and trust). Specifically, KOL’s professionalism and charisma increased users’ pleasure and trust, enhancing impulsive purchase intention. This confirms the SOR model’s stimuli–organism–response path and matches the PAD theory’s role of pleasure, arousal, and dominance in driving behavior. However, KOL characteristics did not significantly affect purposeful purchase intention. This might be due to the planned and rational nature of such purchases, which makes them less influenced by emotional fluctuations. This suggests that the SOR model and PAD theory may be limited in explaining rational purchasing. Further developing the theoretical framework could enhance its applicability across different purchasing scenarios. Overall, the empirical results strongly support that KOL characteristics influence purchasing behavior through emotional mechanisms. This deepens our comprehension of KOL roles and emotional marketing strategies in live shopping.

6.3.2. Mediation Effects Test

To explore the psychological mechanism underlying how KOL characteristics influence users’ purchase intention, this study employed the Bootstrap method for mediation effect testing, with 5000 repeated samples and a 95% confidence interval [

46]. The results (

Table 9) indicate that purposeful purchase intention (Model 1) is subject to partial mediation, whereas impulsive purchase intention (Model 2) is subject to full mediation.

Partial mediation implies that KOL traits directly and indirectly influence purposeful purchase intention through factors such as pleasure, arousal, and trust. By contrast, full mediation indicates that the influence of KOL traits on impulsive purchase intention is entirely mediated by these factors. Specifically, KOL characteristics indirectly affect purposive purchase intention through mediators like pleasure, arousal, and trust, which also directly influence purposive purchase intention. For impulsive purchase intention, KOL traits influence exclusively through mediator variables, indicating that these variables fully mediate the relationship between KOL traits and impulsive purchase intention.

These findings further reveal the internal psychological process by which KOL features influence users’ purchase intention, offering a key basis for optimizing live marketing strategies. This distinction clarifies the roles and mechanisms of KOLs in different purchasing behaviors. For instance, for purposive purchases, KOLs directly recommend products through their characteristics and indirectly drive purchases by building trust and pleasure. For impulsive purchases, this depends more on the immediate emotional responses KOLs can inspire. Understanding these differences enables companies and KOLs to design more effective marketing strategies for optimizing different purchase types.

7. Discussion

7.1. Key Findings

This study deeply explores the influence of KOL characteristics on users’ purchase intention, constructs a theoretical framework based on the SOR model and PAD emotion theory, and derives significant findings through empirical research. First, KOL’s professionalism, popularity, charisma, and entertainment significantly enhance users’ pleasure, arousal, and trust. These emotional responses further boost impulsive purchase intention but have no significant effect on purposive purchase intention. Second, purposive purchase intention exhibits partial mediation in the model, indicating that it is directly influenced by KOL features and indirectly affects impulse purchase via emotional variables. Impulsive purchase intention demonstrates complete mediation, meaning KOL features require emotional variables to trigger impulse purchasing.

7.2. Interpretation of Results and Theoretical Links

7.2.1. Influence of Key Opinion Leaders on Consumption Intention (S-R)

This study found that KOLs significantly enhance users’ impulsive purchasing behavior (H1a) but do not significantly affect purposive purchasing intention (H1b), aligning with SOR model and PAD emotion theory predictions. The SOR model posits that external stimuli (KOL features) trigger emotional responses (pleasure, arousal, and trust), which influence behavioral responses (purchase intention). In live shopping contexts, consumers’ impulsive purchases are easily driven by emotions, whereas purposive purchasing is more rational, planned, and less directly influenced by KOL characteristics. This finding further confirms the SOR model’s effectiveness in explaining live shopping consumer behavior [

28,

29] and demonstrates that PAD emotion theory better describes the relationship between emotional experiences and purchase intentions in live shopping [

30]. For instance, consumers may impulsively purchase due to trust and pleasure when encountering KOLs’ professional explanations and enthusiastic recommendations. However, for planned purchases, they rely on their own needs and rational judgments.

7.2.2. Influence of Key Opinion Leaders on Pleasure, Arousal, and Trust (S-O)

Study results show that KOLs significantly influence user pleasure (H2a), arousal (H2b), and trust (H2c). This aligns with Liu et al. (2023) and confirms the key role of KOLs’ entertaining nature in affecting consumers’ emotions in live-streaming shopping compared to traditional online shopping [

33]. Specifically, KOLs’ professionalism makes consumers perceive them as having rich product information, reducing perceived risk and increasing impulse buying tendencies. Meanwhile, KOLs’ charismatic qualities—such as good looks, talent, and engaging presentations—enhance viewers’ experience, stimulate pleasure and arousal, and catalyze purchase intentions. For instance, a KOL with a friendly image and vivid explanations attracts viewers’ attention and stimulates purchase desire. Through frequent interactions and sharing personal experiences, KOLs become a trusted information source for consumers, building a strong connection and fostering trust. These findings align with Liu et al.’s (2022) study on consumer trust in KOLs, further highlighting KOLs’ role in shaping consumers’ emotions and trust in live shopping [

47].

7.2.3. Arousal, Pleasure, Trust Influence Relationships (O)

Results indicate that emotional pleasure positively correlates with arousal (H3a), and arousal positively correlates with trust (H3b). This contrasts with Koo and Liu’s (2021) findings [

20,

48]. Koo et al. concluded that heightened arousal enhances pleasure, thereby promoting trust formation [

20]. However, our results indicate the opposite. This discrepancy arises from differing definitions of arousal. In this study, arousal is defined as the process by which KOLs stimulate users’ intrinsic psychological needs through social presence and product experiences. For instance, KOLs first engage users with entertainment strategies, and then they create a sense of presence based on user needs. This shortens psychological distance, activates emotional responses, and promotes trust formation. This finding reaffirms the complex interplay among the three emotional dimensions in the PAD model, indicating that emotional dimensions interact to shape consumer psychology and behavior.

7.2.4. Effects of Pleasure, Arousal, and Trust on Purchase Intention (O-R)

In webcast shopping, users’ pleasure (H4a), arousal (H4c), and trust (H4e) positively influence purposive purchase intention. Similarly, pleasure (H4b), arousal (H4d), and trust (H4f) significantly drive impulsive purchasing behavior, aligning with Liu et al. (2023) [

48]. This indicates that arousal and pleasure significantly enhance impulsive buying behavior across settings, including emerging webcast shopping and traditional online and offline environments [

17]. Additionally, users’ pleasurable experiences significantly enhance product trust, which in turn elevates purposive purchase intention [

36]. However, Liu et al. (2022) found that consumer trust does not directly influence purchase intention [

47]. This study introduced the PAD emotion model, revealing a direct correlation between trust and purchase intention. This breaks the “black box” limitation and offers deeper insights into users’ purchase intentions.

Mediation analysis shows that the purposive purchase model (Model 1) exhibits partial mediation. This indicates that KOL characteristics directly stimulate purposive purchasing and indirectly influence purchase intention through emotional variables, like pleasure, arousal, and trust. Conversely, the impulsive purchase model (Model 2) demonstrates complete mediation, indicating that KOL characteristics require emotional variables to trigger impulsive buying. This difference likely originates from the unique live shopping environment. Here, KOLs create a tense atmosphere (e.g., limited-time discounts) to encourage impulsive purchases. During this time, users’ purchasing decisions are primarily emotion-driven, with minimal rational thinking. In contrast, purposive purchasing involves users considering product needs and performance, making the influence of KOL characteristics on purposive purchase intention more complex. This occurs both directly and indirectly through emotional variables. For example, users might directly purchase KOL-recommended products due to trust (direct influence) or make purchase decisions guided by KOLs because of product-related pleasure and arousal (indirect influence). Impulsive buying is often an instant emotional response to KOL stimuli, such as purchasing unplanned products due to enthusiastic recommendations and limited-time offers.

7.3. Practical Implications

For KOLs and enterprises, this study’s findings hold significant practical value: KOLs should enhance their professionalism and charisma, attracting users through positive emotional experiences, thereby boosting purchase intention. Enterprises need to comprehend the complex relationship between KOL characteristics and users’ emotions and behaviors in live shopping, optimizing KOL selection and cooperation strategies. For example, enterprises can accurately identify suitable KOLs by aligning with their product characteristics and target audiences, enhancing marketing effectiveness through data-driven approaches. Concurrently, enterprises should focus on users’ emotional experiences by designing interactive elements that stimulate pleasure and arousal, bolstering brand trust and driving sales conversion.

7.3.1. Expert Bandwagon to Enhance KOL Credibility

In live streaming with goods, KOLs serve as a vital link between users and merchants, playing a crucial role in information transfer. Given the varying quality of KOLs due to the lowered threshold of online live streaming, some KOLs intentionally create a rush atmosphere to boost sales, and even show discrepancies between video displays and actual products, thus severely undermining their credibility. Thus, selecting and training high-quality KOLs with specialized knowledge is crucial. Professional KOLs, or those involving industry experts in live streams, can enhance credibility. They can professionally introduce a product’s appearance, performance, and utility, thereby gaining users’ trust. Additionally, KOLs should prioritize user safety and avoid intentionally creating a rush atmosphere to market products. Moreover, the emotional bias of fans toward KOLs might reduce concerns about alleged false propaganda and lead to “problem-shifting” defenses for idol KOLs [

49]. Hence, only with excellent professional knowledge can KOLs better interact with users, stimulating arousal, pleasure, and trust in products; achieving empathy; and, thus, promoting rational consumption and repurchase behavior. Such a live-streaming sales model can achieve long-term development and gain social recognition.

7.3.2. Create an Immersive Social Presence to Enhance Users’ Buying Emotions

Research findings indicate that impulsive purchasing in live streaming exhibits full mediation, meaning that KOLs stimulate users’ purchasing emotions to induce impulsive buying. Thus, creating an immersive social presence and amplifying users’ buying emotions are key drivers of consumer behavior. Businesses should meticulously plan marketing content, strategically select KOLs, and craft the live broadcast room’s atmosphere. Specifically, enhancing live broadcast fun and interactivity, and selecting humorous anchors, can more effectively engage consumers’ emotions, prompting impulsive purchases. Emotional connection and social identity are crucial for creating an immersive social presence. Anchors should communicate sincerely with viewers, sharing shopping tips and product experiences to foster emotional connections. Encouraging viewers to share personal shopping experiences and product evaluations in the live broadcast room can cultivate shared experiences and identity. Building fan communities and organizing regular activities and sharing sessions can further enhance fans’ sense of belonging and loyalty. Conversely, purposeful purchasing behavior shows partial mediation and primarily targets repeat customers. For these consumers, complex program stimulation or emotional guidance is unnecessary. When products are restocked, businesses can adopt a direct and efficient approach by pre-promoting to maximize short-term sales conversion rates.

8. Limitations and Future Research

This study has several limitations. First, the sample primarily comes from a single live-streaming platform, potentially introducing selection bias. Additionally, the questionnaire data were collected over a short period, which may overlook the temporal impact on user behavior. Future research should expand the sample to multiple platforms and extend the data collection period to improve the findings’ generalizability.

Second, this study primarily examines the direct influence of KOL characteristics on purchase intention and the mediating role of emotional variables, without in-depth exploration of other potential moderating variables. For example, users’ demographic differences (e.g., age, gender, and education level) may influence their perceptions of and responses to KOL features, moderating the relationship between KOL features and purchase intention. Moreover, users’ prior experience with live e-commerce may moderate this relationship, as experienced users might better recognize KOL features and be more influenced by them. Future research could incorporate these moderating variables to further expand and deepen the study’s findings.

Third, this study employed a cross-sectional design, which does not establish a clear causal relationship. Future studies could use experimental designs or longitudinal methods to further validate the causal link between KOL features and user behavior. Exploring additional influencing factors, such as individual user differences and cultural background, could provide a more comprehensive understanding of live shopping behavior.

9. Conclusions

This study explores how KOL features influence users’ purchase intention and reveals the intrinsic link between KOL features and user behavior through a comprehensive SOR-PAD framework. First, KOL features positively influence user emotions, significantly enhancing pleasure, arousal, and trust. These emotional responses further boost impulsive purchase intentions but have no significant direct effect on purposive purchase intentions. Second, our findings indicate that emotional variables mediate the relationship between KOL characteristics and purchase intentions. In impulsive purchase intentions, emotional variables acted as full mediators, indicating that impulsive purchases were entirely driven by these emotional responses. In contrast, emotional variables partially mediated purposive purchase intentions, indicating that rational purchasing decisions were influenced by both emotions and other factors. Overall, this study enhances our understanding of how KOL characteristics influence users’ purchase intentions in live shopping and offers theoretical support and practical guidance for live e-commerce marketing. Future research can expand this theoretical framework, explore additional influencing factors, and further advance the live e-commerce industry.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.L. and H.H.; methodology, J.W.; software and investigation, H.H.; resources; X.L. and J.W.; data curation, J.W and H.H.; writing original draft preparation, and writing—review and editing, J.W.; visualization, X.L.; supervision, X.L. and H.H.; project administration, X.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Social Science Foundation of China under the general project “Research on Ethnic Consciousness Writing and Chinese Cultural Identity in Hakka Video Literature in Southeast Asia”(grant number 2024GZYB11), and this project is headed by Prof. Li Xiaohua.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments. At the same time, the Ethics Committee for Laboratory Animals of South China University of Technology (SCUT) conducted a preliminary review of this project in accordance with the relevant laws and regulations and ethical guidelines, review No. PA-2025166, and concluded that the use of laboratory animals in the experiments in the protocol meets the ethical requirements. After this experimental protocol was formally approved, the investigators were asked to conduct the experiments in accordance with the relevant regulations.

Informed Consent Statement

All participants were informed of the stages and objectives of the study and were asked to sign an informed consent form agreeing to participate in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data shown in this research are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Liu, W. Beware of the Pit! Faced with “grass” information, 70% of consumers impulsively order. China Consumer News, 23 July 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Oraedu, C.; Izogo, E.E.; Nnabuko, J.; Ogba, I.E. Understanding electronic and face-to-face word-of-mouth influencers: An emerging market perspective. Manag. Res. Rev. 2021, 44, 112–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.W.; Hsu, P.Y.; Chen, J.; Hung, W.-H. Utilitarian and/or hedonic shopping–consumer motivation to purchase in smart stores. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2023, 123, 821–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F. Live bandwagon chaos, exactly how to break. Jilin Daily, 3 December 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. An Approach to Environmental Psychology; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Dreisbach, G. Using the theory of constructed emotion to inform the study of cognition-emotion interactions. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2023, 30, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Huang, J.S. Effects of Price Discounts and Bonus Packs on Online Impulse Buying. Soc. Behav. Pers. Int. J. 2014, 42, 1293–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Hongxiu, L.; Feng, H. Website Attributes in Urging Online Impulse Purchase: An Empirical Investigation on Consumer Perceptions. Decis. Support Syst. 2013, 55, 829–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F. Research of Opinion Leaders’ Impact on Purchase Intention under Social Commerce. Master’s Thesis, Nanjing University, Nanjing, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarsfeld, P.F.; Berelson, B.; Gaudet, H. The People’s Choice: How the Voter Makes up His Mind in a Presidential Campaign; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1944; pp. 177–186. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, L.Y.; Gao, S.Q.; Zhang, X.Y. How to Use Live Streaming to Improve Consumer Purchase Intentions: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H. Research on the Influence of Beauty Opinion Leaders on Consumers’ Willingness to Buy. Master’s Thesis, South China University of Technology, Guangzhou, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. Study on the Influence of Opinion Leaders' Characteristics Spontaneous Formation of Fresh Agricultural Products Brand Community on Community Loyalty. Ph.D. Thesis, Jilin University, Jilin, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, B.; Roy, S.K.; Kesharwani, A.; Sadeghinejad, I. The adoption of mobile payment services by millennials: The roles of smartphone addiction and situational variables. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2023, 35, 2912–2931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L. Study on the Ethical Issues of the Pan-Entertainment Network Live. Ph.D. Thesis, Wuhan University of Technology, Wuhan, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.-C.; Lin, Y.-C. What drives live-stream usage intention? The perspectives of flow, entertainment, social interaction, and endorsement. Telemat. Inform. 2018, 35, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, P.; Gottwald, W. Impulsive consumer buying as a result of emotions. J. Bus. Res. 1982, 10, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, M.K.; Bateson, J.G. Perceived control and the effects of crowding and consumer choice on the service experience. J. Consum. Res. 1991, 18, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.; Chih, W.; Liou, D.; Hwang, L. The influence of web aesthetics on customers’ PAD. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 36, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, D.; Lee, J. Inter-relationships among dominance, energetic and tense arousal, and pleasure, and differences in their impacts under online and offline environment. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2011, 27, 1740–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IiMedia Research. 2024 China’s Top 100 Opinion Leaders in Carrying Goods List is Freshly Released! See Who Has the Most Money-Sucking Ability. AiMedia, 20 June 2024. Available online: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/ms0_vt67o_kD77HyISm9Rg (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Yang, Y.; Huang, J. Speaking with a “forked tongue”—Misalignment between user ratings and textual emotions in LLMs. Kybernetes 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Fan, S.; Wu, L. Registration system review inquiry and IPO information disclosure on STAR market: Textual analysis based on LDA topic model. J. Manag. Sci. China 2022, 25, 45–62. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Wu, G.; Chen, L. Research on Multi-stage Fresh Consumer Demands Based on LDA Topic Model: A Case of JingDong. J. Manag. Case Stud. 2024, 17, 105–122. [Google Scholar]

- Chuang, J.; Manning, C.D.; Heer, J. Termite: Visualization techniques for assessing textual topic models. In Proceedings of the International Working Conference On Advanced Visual Interfaces, Capri Island, Italy, 21–25 May 2012; pp. 74–77. [Google Scholar]

- Sievert, C.; Shirley, K. LDAvis: A method for visualizing and interpreting topics. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Interactive Language Learning, Visualization, and Interfaces, Baltimore, MD, USA, 27 June 2014; pp. 63–70. [Google Scholar]

- Koo, D.-M.; Ju, S.-H. The interactional effects of atmospherics and perceptual curiosity on emotions and online shopping intention. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.; Keller, K. Marketing Management, 14th ed.; Wang, Y.G.; Yu, H.Y.; Xu, L.; Chen, R.; Zhang, H.X., Translators; Renmin University of China Press: Beijing, China, 2012; pp. 172–196. [Google Scholar]

- Everett, M.R.; Cartano, D.G. Methods of measuring opinion leaders: Identifying their characteristics by self-report. J. Mark. 1971, 35, 48–53. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, M.; Wang, Q. A Study on the Evolutionary Mechanism of the Idea Leader in the Consumer Advice Network of the Expectancy Clue and the Network Structure. J. Manag. World 2015, 7, 109–188. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, H.; Mei, H. Empirical Research on the Decision-Making Influence Factors in Consumer Purchase Behavior of Webcasting Platform. Lect. Notes Multidiscipl. Ind. Eng. 2018, 12, 1017–1028. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Y.; Zhao, Y. Survey of Key Technologies in Personalization Application. Libr. Inf. 2011, 1, 59–65. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Q.; Yin, M. The Influence of Internet Shopping Festival Atmosphere on Consumer Impulse Buying. Commer. Res. 2018, 7, 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- Quester, P.; Lim, A.L. Product involvement/brand loyalty: Is there a link? J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2003, 12, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, J. Stimulus-Organism-Response Reconsidered: An Evolutionary Step in Modeling Consumer Behavior. J. Consum. Psychol. 2002, 12, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, S.; Clark, M.; Samouel, P.; Hair, N. Online Customer Experience in E-Retailing: An Empirical Model of Antecedents and Outcomes. J. Retail. 2012, 88, 308–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.H.; Chen, S.W. The impact of online store environment cues on purchase intention. Online Inf. Rev. 2008, 32, 818–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M. Research on the Influencing Factors of Online Purchase Intention Based on Consumer Sentiment. Master’s Thesis, Wuhan University of Technology, Wuhan, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J. Research on webcasting under the perspective of symbolic interactionism. Cover Edit. News 2018, 6, 24–27. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, H.Y.; Tsou, H.T. The effect of website quality on consumer emotional states and repurchases intention. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2011, 5, 6195–6200. [Google Scholar]

- Donovan, R.J.; Rossiter, J.R. Store atmosphere: An environmental psychology approach. J. Retail. 1982, 58, 34–57. [Google Scholar]

- Ridings, C.M.; Gefen, D.; Arinze, B. Some antecedents and effects of trust in virtual communities. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2002, 3, 271–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AiMedia Consulting. China’s Live Streaming E-Commerce Industry Operation big Data Analysis and Trend Research Report, 2022–2023; AiMedia Consulting: Guangzhou, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Market. Res. 1981, 18, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bujang, M.A.; Omar, E.D.; Baharum, N.A. A review on sample size determination for cronbach’s alpha test: A simple guide for researchers. Malays. J. Med. Sci. 2018, 25, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, A.F. Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Commun. Monogr. 2009, 76, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, W.; Li, J.; Zhang, Q. The influence of key opinion leaders on consumers' purchase intention based on SOR model. J. Chongqing Univ. Technol. (Social Sci.) 2020, 34, 70–79. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Q.; Yin, M. Research on the Influence of Webcast Shopping Features on Consumer Buying Behavior. Soft Sci. 2020, 34, 108–114. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Q. Return and Transcendence: A Study of Netizens' Emotional Attitudes toward “Netflix Carrying Goods” in the Context of Fan Culture. Southeast Commun. 2020, 6, 115–119. [Google Scholar]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Check it out @ZhangSan”. After this step, the text becomes as follows: “This product is fantastic Check it out ZhangSan”. The second step is to eliminate repetitive phrases and short texts. Repetitive phrases (e.g., “haha” and “huh”) and short texts (less than 2 characters) typically lack substantive information, hindering effective topic extraction and sentiment analysis. For instance, the repeated phrase “hahahahaha” will be removed. The third step involves filtering based on text length by setting the threshold to 2 characters to eliminate overly short texts. For example, the text “good” is removed due to insufficient information conveyance.

Check it out @ZhangSan”. After this step, the text becomes as follows: “This product is fantastic Check it out ZhangSan”. The second step is to eliminate repetitive phrases and short texts. Repetitive phrases (e.g., “haha” and “huh”) and short texts (less than 2 characters) typically lack substantive information, hindering effective topic extraction and sentiment analysis. For instance, the repeated phrase “hahahahaha” will be removed. The third step involves filtering based on text length by setting the threshold to 2 characters to eliminate overly short texts. For example, the text “good” is removed due to insufficient information conveyance.