Digital Franchising in the Age of Transformation: Insights from the Motivation-Opportunity-Ability Framework

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. The Rise and Advantages of Digital Franchising

2.2. Motivation-Opportunity-Ability (MOA) Framework

2.3. Motivation: Desire for Self-Expression and Expected External Rewards

2.4. Opportunity: Platform Support and Platform Attractiveness

2.5. Ability: Self-Efficacy and Digital Literacy

2.6. Entrepreneurial Intentions and Consumption Adoption Intention for Digital Franchising

3. Research Methodology

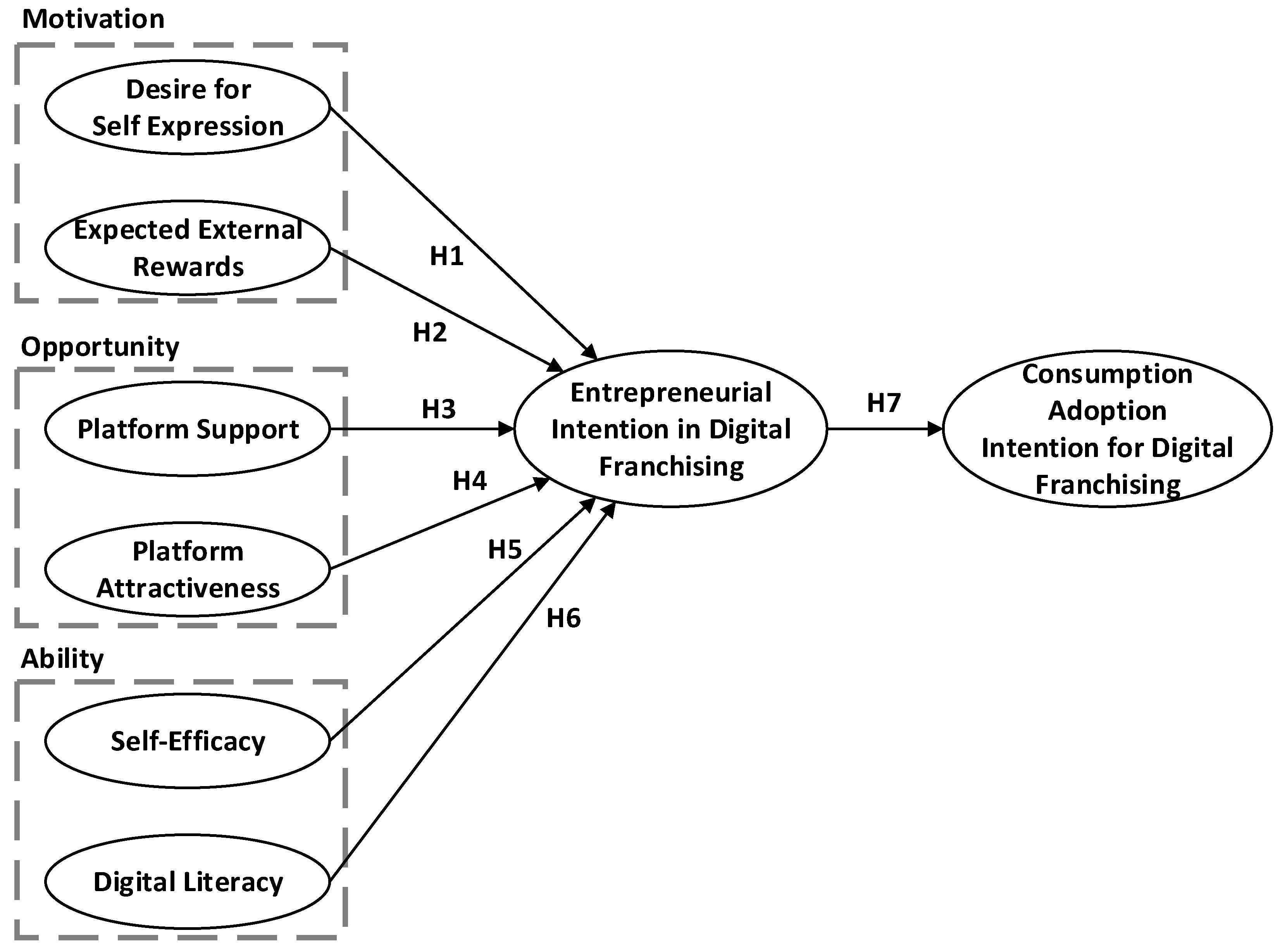

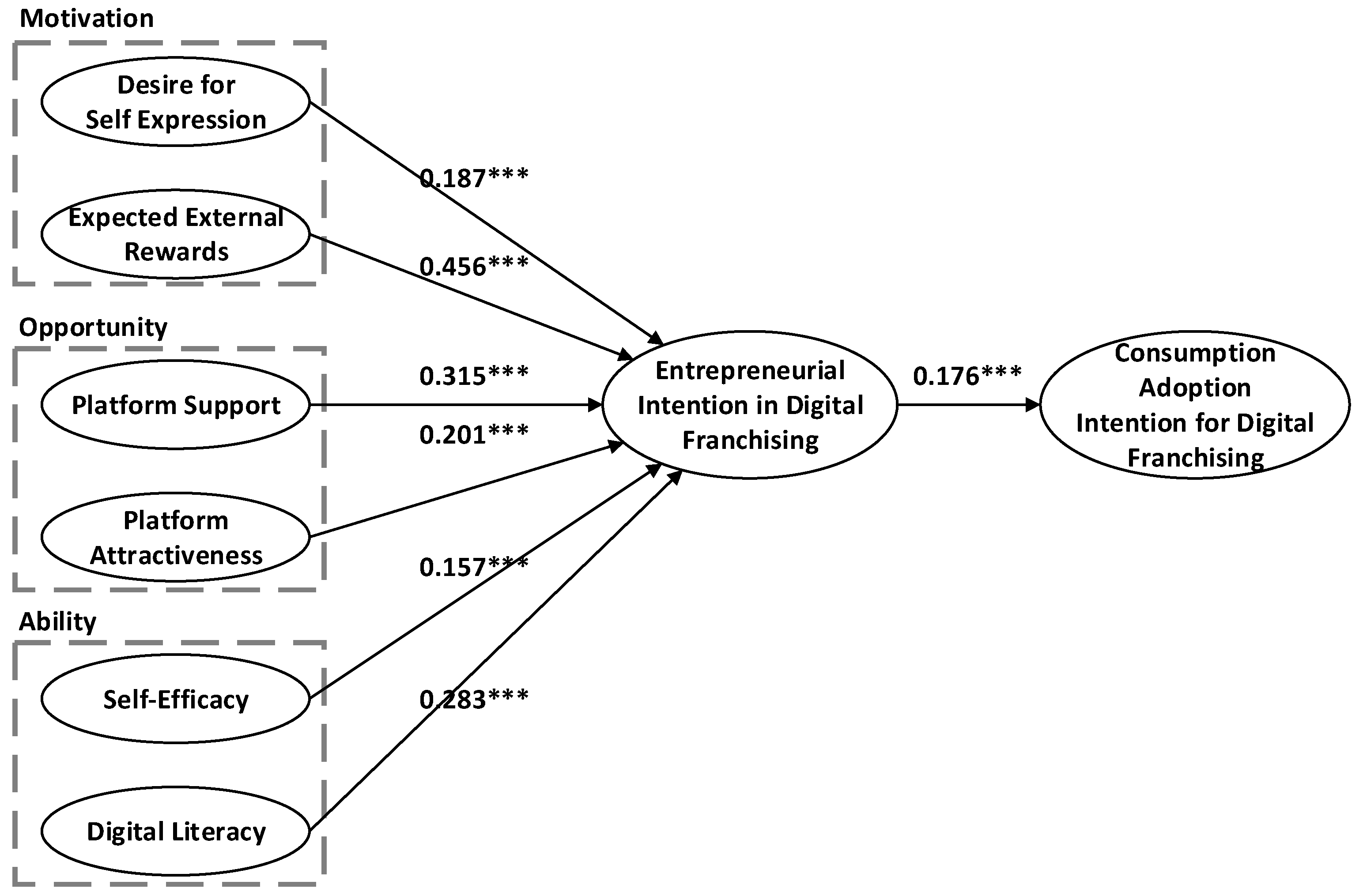

3.1. Research Model

3.2. Questionnaire Design

3.3. Sample and Data Collection

3.4. Methods for Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Reliability and Validity

4.2. Mediation Analysis: Direct and Indirect Effects

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Practical Implications

6.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- MOEA. Annual Important Statistical Table of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises; MOEA, Small and Medium Enterprise and Startup Administration: Taipei, Taiwan, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, D.; Shang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y. Does Entrepreneurship Policy Encourage College Graduates’ Entrepreneurship Behavior: The Intermediary Role Based on Entrepreneurship Willingness. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrawan, S.A.; Chatra, A.; Iman, N.; Hidayatullah, S.; Suprayitno, D. Digital transformation in MSMEs: Challenges and opportunities in technology management. J. Inf. Dan Teknol. 2024, 6, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; LI, Y. The use of data-driven insight in ambidextrous digital transformation: How do resource orchestration, organizational strategic decision-making, and organizational agility matter? Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 196, 122851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flavián, C.; Guinaliu, M.; Lu, Y. Mobile payments adoption–Introducing mindfulness to better understand consumer behavior. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2020, 38, 1575–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavrl, I.; Vukovic, D.; Cerovic, L. Economic and social development. In Proceedings of the 72nd International Scientific Conference on Economic and Social Development-“Digital Transformation and Business”, Varazdin, Croatia, 30 September–1 October 2021; Varazdin Development and Entrepreneurship Agency: Varazdin, Croatia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rana, N.P.; Barnard, D.J.; Baabdullah, A.M.; Rees, D.; Roderick, S. Exploring barriers of m-commerce adoption in SMEs in the UK: Developing a framework using ISM. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 44, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruen, T.W.; Osmonbekov, T.; Czaplewski, A.J. How e-communities extend the concept of exchange in marketing: An application of the motivation, opportunity, ability (MOA) theory. Mark. Theory 2005, 5, 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambisan, S. Digital entrepreneurship: Toward a digital technology perspective of entrepreneurship. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2017, 41, 1029–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guenzi, P.; Nijssen, E.J. The relationship between digital solution selling and value-based selling: A motivation-opportunity-ability (MOA) perspective. Eur. J. Mark. 2023, 57, 745–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersyah, M.H.; Hadining, A. The Effect of Motivation-Opportunity-Ability (MOA) Framework in SME’s Social Media Marketing Adoption. Int. J. Innov. Enterp. Syst. 2020, 4, 66–77. [Google Scholar]

- Baskaran, S.; Devagaran, S.; Ganesan, K.; Mahadi, N. Intrinsic motivation and entrepreneurial start-up intentions: A franchising perspective. Int. J. Entrep. Ventur. 2021, 13, 443–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookes, M.; Altinay, L.; Wang, X.L.; Yeung, R. Opportunity identification and evaluation in franchisee business start-ups. J. Serv. Theory Pract. 2016, 26, 889–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, S. The impact of franchisor resources, relational capital, and market responsiveness on franchisee performance: From the dynamic capability perspective. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2024, 14, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong-thi, N.T. Fostering Franchising Intention of SMEs in Vietnam: A Motivation-Opportunity-Ability Perspective. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2022, 9, 99–107. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, J.; Castro, R. SMEs Must Go Online—E-Commerce as an Escape Hatch for Resilience and Survivability. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 3043–3062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, U.; Fülöp, M.T.; Tiron-Tudor, A.; Topor, D.I.; Căpușneanu, S. Impact of Digitalization on Customers’ Well-Being in the Pandemic Period: Challenges and Opportunities for the Retail Industry. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Reuver, M.; Sørensen, C.; Basole, R.C. The digital platform: A research agenda. J. Inf. Technol. 2018, 33, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuver, M.; Verschuur, E.; Nikayin, F.; Cerpa, N.; Bouwman, H. Collective action for mobile payment platforms: A case study on collaboration issues between banks and telecom operators. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2015, 14, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, C.; Man, M. The Challenges and Solutions for Digital Entrepreneurship Platforms in Enhancing Firm’s Capabilities. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2021, 16, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Kremez, Z.; Frazer, L.; Quach, S.; Thaichon, P. Collaboration, Communication, Support, and Relationships in the Context of E-Commerce Within the Franchising Sector. In Relationship Marketing in Franchising and Retailing; Routledge: London, UK, 2023; pp. 25–47. [Google Scholar]

- Kistruck, G.M.; Webb, J.W.; Sutter, C.J.; Ireland, R.D. Microfranchising in base–of–the–pyramid markets: Institutional challenges and adaptations to the franchise model. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2011, 35, 503–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacInnis, D.J.; Jaworski, B.J. Information processing from advertisements: Toward an integrative framework. J. Mark. 1989, 53, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacInnis, D.J.; Park, C.W. The differential role of characteristics of music on high-and low-involvement consumers’ processing of ads. J. Consum. Res. 1991, 18, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maclnnis, D.J.; Moorman, C.; Jaworski, B.J. Enhancing and measuring consumers’ motivation, opportunity, and ability to process brand information from ads. J. Mark. 1991, 55, 32–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyer, W.D.; MacInnis, D.J. Consumer Behavior; Houghton Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Tanera, L. Tantangan Dalam Menghadapi Perkembangan Teknologi Dan Trasformasi Digital Dalam Bisnis Waralaba. Multiling. J. Univers. Stud. 2023, 3, 481–489. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 25, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolvereid, L. Prediction of employment status choice intentions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1996, 21, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltanifar, M.; Hughes, M.; Göcke, L. Digital Entrepreneurship: Impact on Business and Society; Springer Nature: Berlin, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus, S.; Palmer, C.; Kailer, N.; Kallinger, F.L.; Spitzer, J. Digital entrepreneurship: A research agenda on new business models for the twenty-first century. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2019, 25, 353–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulfert-Blank, A.-S.; Schmidt, I. Assessing digital self-efficacy: Review and scale development. Comput. Educ. 2022, 191, 104626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetri, B.; Juujärvi, S. Self-efficacy, internet self-efficacy, and proxy efficacy as predictors of the use of digital social and health care services among mental health service users in Finland: A cross-sectional study. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2022, 15, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Advani, A.; Mergenthaler, J. From competencies to strengths: Exploring the role of character strengths in developing twenty-first century-ready leaders: A strengths-based approach. Discov. Psychol. 2024, 4, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanage, R.; Davies, M.A.; Stenholm, P.; Scott, J.M. Extending the theory of planned behavior–A longitudinal study of entrepreneurial intentions. Entrep. Res. J. 2024, 14, 1223–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Liu, Y.; Dai, J.; Li, Y. An application of the planned behavior theory to predict Chinese firms’ environmental innovation. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2022, 65, 2676–2695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffman, E. The moral career of the mental patient. Psychiatry 1959, 22, 123–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carsrud, A.; Brännback, M. Entrepreneurial motivations: What do we still need to know? J. Small Bus. Manag. 2011, 49, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer, R.; Warner, L.M. Forschung zur Selbstwirksamkeit bei Lehrerinnen und Lehrern. Handb. Der Forsch. Zum Lehrerberuf 2014, 2, 662–678. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, D.; Kohtamäki, M.; Peng, X.; Kong, X. How digital orientation impacts service innovation in hotels: The role of digital capabilities and government support. Tour. Econ. 2024, 31, 221–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, S. Consumer perceived risk of using autonomous retail technology. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 171, 114389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlenker, B.R.; Leary, M.R. Social anxiety and self-presentation: A conceptualization model. Psychol. Bull. 1982, 92, 641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A.; Zeithaml, V.A.; Malhotra, A. ES-QUAL: A multiple-item scale for assessing electronic service quality. J. Serv. Res. 2005, 7, 213–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Deursen, A.J.; Van Dijk, J.A. The digital divide shifts to differences in usage. New Media Soc. 2014, 16, 507–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helsper, E.J.; Eynon, R. Digital natives: Where is the evidence? Br. Educ. Res. J. 2010, 36, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Laar, E.; Van Deursen, A.J.M.; Van Dijk, J.A.M.; De Haan, J. The relation between 21st-century skills and digital skills: A systematic literature review. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 72, 577–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Bala, H. Technology acceptance model 3 and a research agenda on interventions. Decis. Sci. 2008, 39, 273–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Maalouf, N.J.; Sayegh, E.; Makhoul, W.; Sarkis, N. Consumers’ attitudes and purchase intentions toward food ordering via online platforms. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2025, 82, 104151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón-Monge, E.; Ramírez-Hurtado, J.M. Measuring the consumer engagement related to social media: The case of franchising. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 22, 1249–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Lu, Y. The effects of personality traits on user acceptance of mobile commerce. Intl. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2011, 27, 545–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touni, R.; Kim, W.G.; Choi, H.M.; Ali, M.A. Antecedents and an outcome of customer engagement with hotel brand community on Facebook. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2020, 44, 278–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Seibert, S.E.; Hills, G.E. The mediating role of self-efficacy in the development of entrepreneurial intentions. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, N.F., Jr.; Reilly, M.D.; Carsrud, A.L. Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. J. Bus. Ventur. 2000, 15, 411–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F.; Chen, Y.W. Development and cross–cultural application of a specific instrument to measure entrepreneurial intentions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 593–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertola, P.; Teunissen, J. Fashion 4.0. Innovating fashion industry through digital transformation. Res. J. Text. Appar. 2018, 22, 352–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, S.F.; Tan, C.L.; Kumar, A.; Tan, K.H.; Wong, J.K. Investigating the impact of AI-powered technologies on Instagrammers’ purchase decisions in digitalization era—A study of the fashion and apparel industry. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2022, 177, 121551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavidas, K.; Petropoulou, A.; Papadakis, S.; Apostolou, Z.; Komis, V.; Jimoyiannis, A.; Gialamas, V. Factors Affecting Response Rates of the Web Survey with Teachers. Computers 2022, 11, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sammut, R.; Griscti, O.; Norman, I.J. Strategies to improve response rates to web surveys: A literature review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2021, 123, 104058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, B. Ten commandments of structural equation modeling. In Proceedings of the US Dept of Education, Office of Special Education Programs (OSEP) Project Directors’ Conference, Washington, DC, USA, 16 July 1998; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Munsch, A. Millennial and generation Z digital marketing communication and advertising effectiveness: A qualitative exploration. J. Glob. Sch. Mark. Sci. 2021, 31, 10–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreyer, C.; Stojanová, H. How entrepreneurial is German generation Z vs. generation Y? A literature review. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2023, 217, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, J.S.; Overton, T.S. Estimating nonresponse bias in mail surveys. J. Mark. Res. 1977, 14, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M.W.; Cudeck, R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociol. Methods Res. 1992, 21, 230–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Z.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, S.; Zhong, L.; Zhang, W. Influencing Path of Consumer Digital Hoarding Behavior on E-Commerce Platforms. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Description | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 273 | 55.6 |

| Female | 218 | 44.4 | |

| Age | 18–22 | 197 | 40.1 |

| 23–30 | 172 | 35.0 | |

| 31–40 | 74 | 15.1 | |

| 41–50 or older | 48 | 9.8 | |

| Level of Education | High school/vocational or below | 23 | 4.7 |

| Bachelor’s degree or currently studying | 392 | 79.8 | |

| Master’s or above | 76 | 15.5 | |

| Monthly Personal Income | Less than TWD 20,000 | 187 | 38.1 |

| TWD 20,001~TWD 40,000 | 234 | 47.7 | |

| TWD 40,001~TWD 60,000 | 39 | 7.9 | |

| TWD 60,001~TWD 80,000 | 26 | 5.3 | |

| Above TWD 80,001 | 5 | 1 |

| Variable | Items | Standardized Factor Loading | CR | AVE | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Desire for Self-Expression | I aim to showcase my abilities and talents through digital franchising. | 0.915 *** | 0.921 | 0.771 | 0.873 |

| Achieving my goals through digital franchising provides me with a greater sense of self-worth. | 0.872 *** | ||||

| Digital franchising offers me an opportunity to demonstrate my leadership skills. | 0.783 *** | ||||

| I aspire to gain recognition from others by successfully managing a digital franchise. | 0.814 *** | ||||

| Expected External Rewards | I believe participating in digital franchising will provide me with greater financial rewards. | 0.923 *** | 0.945 | 0.792 | 0.813 |

| Digital franchising offers me a stable financial income. | 0.831 *** | ||||

| Successfully operating a digital franchise enhances my social status. | 0.865 *** | ||||

| The success of digital franchising helps me expand my network and increase my social influence. | 0.661 *** | ||||

| Platform Support | I feel that the digital franchising platform provides sufficient technical support. | 0.889 *** | 0.923 | 0.812 | 0.880 |

| I can obtain the necessary resources (e.g., tools or data) from the digital franchising platform. | 0.922 *** | ||||

| The digital franchising platform offers continuous business guidance and training. | 0.814 *** | ||||

| I find the digital franchising platform helpful in solving my entrepreneurial challenges. | 0.795 *** | ||||

| The platform provides clear processes and guidelines to help me succeed in franchising. | 0.684 *** | ||||

| Platform Attractiveness | I find the design and functionality of the digital franchising platform user-friendly. | 0.874 *** | 0.822 | 0.702 | 0.894 |

| The platform’s reputation and credibility enhance its attractiveness to me as an entrepreneur. | 0.741 *** | ||||

| The platform offers unique advantages that attract more customers. | 0.698 *** | ||||

| I prefer a more attractive digital franchising platform over starting a business independently. | 0.789 *** | ||||

| Self-Efficacy | I am confident in achieving my digital franchising goals, even with limited resources. | 0.941 *** | 0.917 | 0.802 | 0.903 |

| I can effectively solve challenges encountered in operating a digital franchise. | 0.864 *** | ||||

| I can maintain the operation of my digital franchise in challenging market conditions. | 0.867 *** | ||||

| I feel confident in achieving the expected outcomes of my digital franchising efforts. | 0.872 *** | ||||

| Digital Literacy | I know how to use social media to promote digital franchising products or services. | 0.733 *** | 0.816 | 0.694 | 0.914 |

| I am familiar with data analysis tools and their application in business decisions for digital franchising. | 0.784 *** | ||||

| I can utilize digital technologies to improve the efficiency of my digital franchising operations. | 0.759 *** | ||||

| Entrepreneurial Intention in Digital Franchising | I am motivated to explore entrepreneurial opportunities through digital franchising. | 0.694 *** | 0.875 | 0.713 | 0.814 |

| I plan to take specific actions toward starting a digital franchise. | 0.713 *** | ||||

| I feel determined to launch a business using digital franchising platforms. | 0.721 *** | ||||

| Consumption adoption intention of digital franchises | I am likely to use a digital franchising platform for purchasing goods or services. | 0.889 *** | 0.942 | 0.795 | 0.849 |

| I would recommend digital franchising platforms to others. | 0.911 *** | ||||

| I feel confident engaging with businesses hosted on digital franchising platforms. | 0.874 *** | ||||

| I intend to continue using digital franchising platforms for future transactions. | 0.924 *** |

| Name of Category | Name of Index | Index Value | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute Fit | RMSEA | 0.064 | The required level is achieved. |

| Incremental Fit | CFI | 0.913 | The required level is achieved. |

| Parsimonious Fit | Chisq/df | 2.734 | The required level is achieved. |

| Variable | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Desire for Self-Expression | 6.1 | 0.74 | 0.960 | |||||||

| Expected External Rewards | 5.9 | 0.80 | 0.810 ** | 0.972 | ||||||

| Platform Support | 6.3 | 0.75 | 0.737 ** | 0.703 ** | 0.961 | |||||

| Platform Attractiveness | 6.1 | 0.93 | 0.847 ** | 0.726 ** | 0.773 ** | 0.907 | ||||

| Self-Efficacy | 6.2 | 1.11 | 0.723 ** | 0.844 ** | 0.671 ** | 0.637 ** | 0.958 | |||

| Digital Literacy | 6.0 | 0.80 | 0.669 ** | 0.644 ** | 0.736 ** | 0.704 ** | 0.611 ** | 0.903 | ||

| EIDF | 5.9 | 0.94 | 0.894 ** | 0.788 ** | 0.714 ** | 0.818 ** | 0.702 ** | 0.646 ** | 0.935 | |

| CAIDF | 6.3 | 0.98 | 0.708 ** | 0.876 ** | 0.613 ** | 0.626 ** | 0.835 ** | 0.554 ** | 0.742 ** | 0.971 |

| Hypothesized Paths | Path Coefficient | SE | t-Value | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1: Desire for Self-Expression → EIDF | 0.187 *** | 0.43 | 3.412 *** | Supported |

| H2: Expected External Rewards → EIDF | 0.456 *** | 0.41 | 9.539 *** | Supported |

| H3: Platform Support → EIDF | 0.315 *** | 0.52 | 7.898 *** | Supported |

| H4: Platform Attractiveness → EIDF | 0.201 *** | 0.31 | 5.317 *** | Supported |

| H5: Self-Efficacy → EIDF | 0.157 *** | 0.35 | 2.574 *** | Supported |

| H6: Digital Literacy → EIDF | 0.283 *** | 0.47 | 6.153 *** | Supported |

| H7: EIDF → CAIDF | 0.176 *** | 0.42 | 2.797 *** | Supported |

| Path | Effect Type | β | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Motivation → EIDF → CAIDF | Indirect | 0.081 | <0.01 |

| Opportunity → EIDF → CAIDF | Indirect | 0.074 | <0.01 |

| Ability → EIDF → CAIDF | Indirect | 0.069 | <0.01 |

| EIDF → CAIDF | Direct | 0.176 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hu, T.-L.; Chao, C.-M.; Wu, C.-C.; Lin, C.-H.; Chi, S.-C. Digital Franchising in the Age of Transformation: Insights from the Motivation-Opportunity-Ability Framework. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20020107

Hu T-L, Chao C-M, Wu C-C, Lin C-H, Chi S-C. Digital Franchising in the Age of Transformation: Insights from the Motivation-Opportunity-Ability Framework. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research. 2025; 20(2):107. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20020107

Chicago/Turabian StyleHu, Tung-Lai, Chuang-Min Chao, Chien-Chih Wu, Chia-Hung Lin, and Shu-Che Chi. 2025. "Digital Franchising in the Age of Transformation: Insights from the Motivation-Opportunity-Ability Framework" Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 20, no. 2: 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20020107

APA StyleHu, T.-L., Chao, C.-M., Wu, C.-C., Lin, C.-H., & Chi, S.-C. (2025). Digital Franchising in the Age of Transformation: Insights from the Motivation-Opportunity-Ability Framework. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 20(2), 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20020107