How Streamers Foster Consumer Stickiness in Live Streaming Sales

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Live Streaming Sales

2.2. Social Support

2.3. Social Identification

2.4. Consumer Stickiness

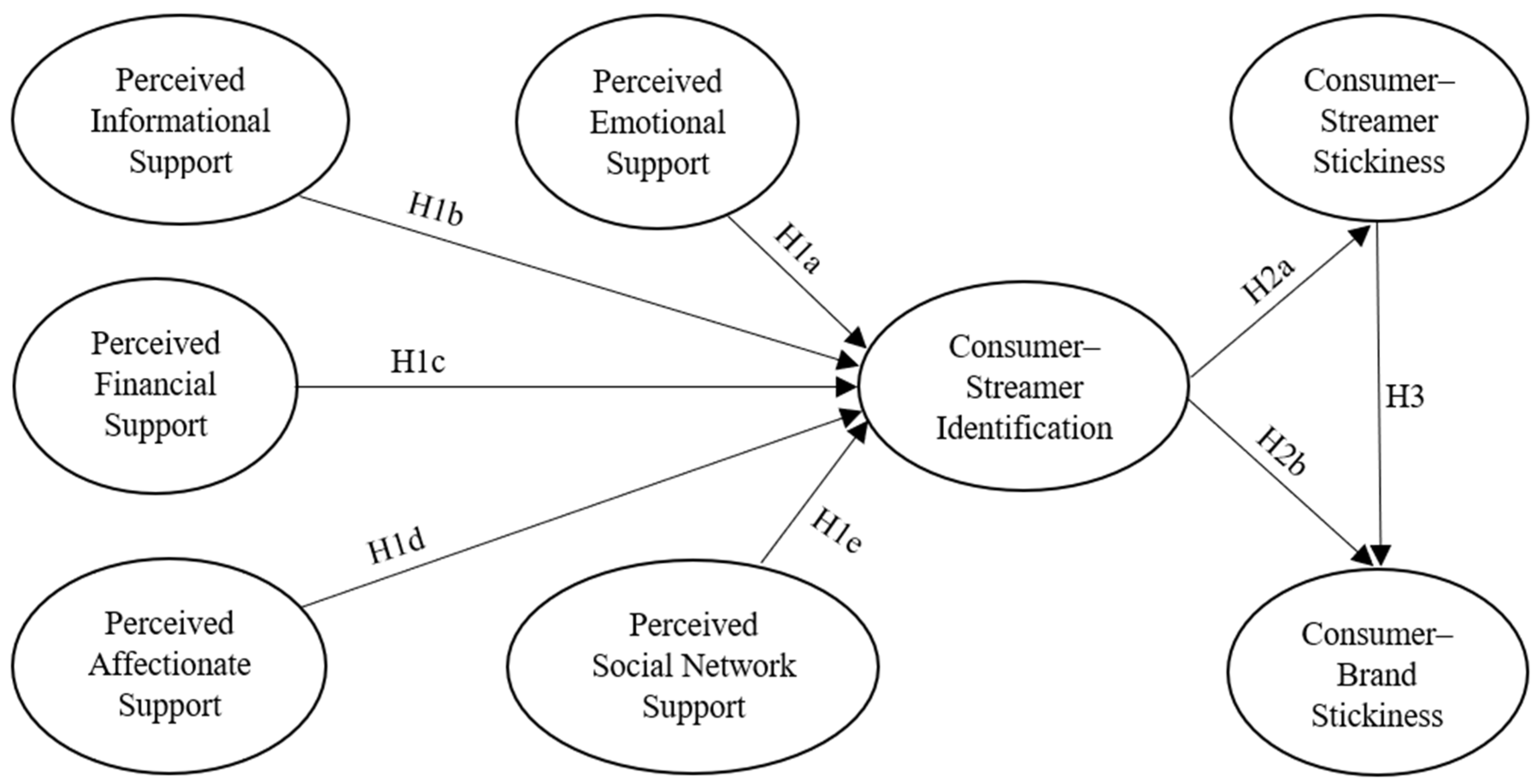

3. Conceptual Model and Hypotheses

3.1. The Impact of Perceived Streamer Support on Consumer–Streamer Identification

3.2. The Impact of Consumer–Streamer Identification on Consumer Stickiness

3.3. The Impact of Consumer–Streamer Stickiness on Consumer–Brand Stickiness

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Sample and Data Collection Procedure

4.2. Measure Operationalization

4.3. Testing for Common Method Bias

5. Data Analysis and Results

5.1. Measurement Model Evaluation

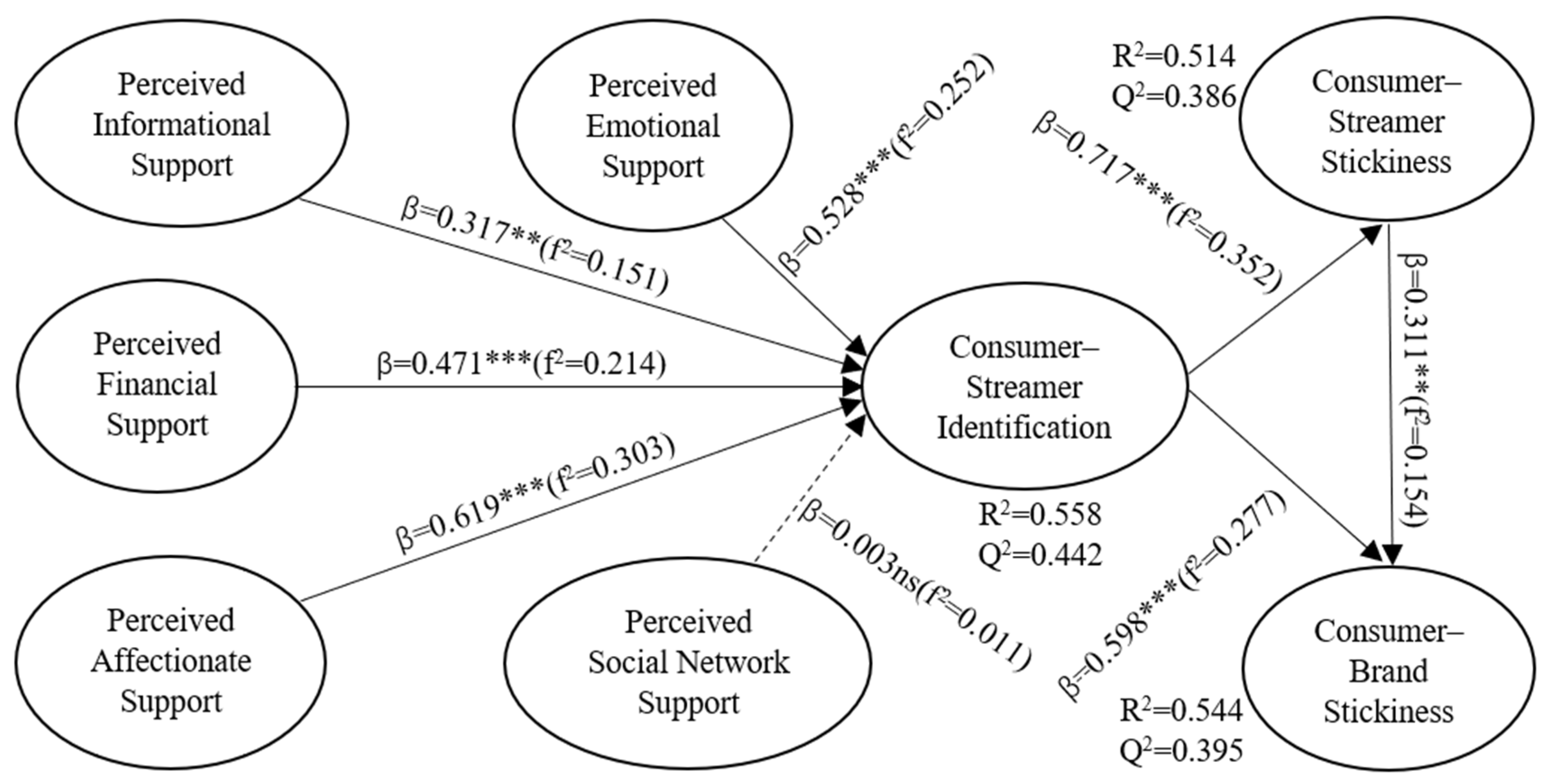

5.2. Structural Model Evaluation and Hypothesis Test

6. Discussion and Implications

6.1. Theoretical Contributions

6.2. Managerial Implications

6.3. Limitations and Further Research Avenues

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wongkitrungrueng, A.; Dehouche, N.; Assarut, N. Live streaming commerce from the sellers’ perspective: Implications for online relationship marketing. J. Mark. Manag. 2020, 36, 488–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.-W.; Shieh, M.-D.; Lien, J.-J.J.; Yang, J.-F.; Chu, W.-T.; Huang, T.-H.; Hsieh, H.-C.; Chiu, H.-T.; Tu, K.-C.; Chen, Y.-T.; et al. Enhancing Fan Engagement in a 5G Stadium with AI-Based Technologies and Live Streaming. IEEE Syst. J. 2022, 16, 3169553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, T.; Wang, L.; Song, Y. Impact of live commerce spillover effect on supply chain decisions. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2022, 122, 1109–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Liu, M.T. Investigating the live streaming sales from the perspective of the ecosystem: The structures, processes and value flow. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2023, 35, 1157–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Shao, X.; Li, X.; Guo, Y.; Nie, K. How Live Streaming Influences Purchase Intentions in Social Commerce: An IT Affordance Perspective. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2019, 37, 100886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Kim, H.-M. What online game spectators want from their twitch streamers: Flow and well-being perspectives. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 66, 102951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, X.; Cai, J. How attachment affects user stickiness on live streaming platforms: A socio-technical approach perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 60, 102478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Törhönen, M.; Giertz, J.; Weiger, W.H.; Hamari, J. Streamers: The new wave of digital entrepreneurship? Extant corpus and research agenda. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2021, 46, 101027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Cheng, X.; Huang, X. “Oh, My God, Buy It!” Investigating Impulse Buying Behavior in Live Streaming Commerce. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Int. 2023, 39, 2436–2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Y. Why do audiences choose to keep watching on live video streaming platforms? an explanation of dual identification framework. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 75, 594–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrich, T.; Schlauderer, S.; Overhage, S. The Impact of Social Commerce Feature Richness on Website Stickiness through Cognitive and Affective Factors: An Experimental Study. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2019, 36, 100861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Min, Q.; Han, S.; Liu, Z. Understanding Followers’ Stickiness to Digital Influencers: The Effect of Psychological Responses. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 54, 102169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Qi, Y.; Li, X. What affects the user stickiness of the mainstream media websites in China? Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2018, 29, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.L.; Liao, Y.C. Exploring the Linkages between Perceived Information Accessibility and Microblog Stickiness: The Moderating Role of a Sense of Community. Inf. Manag. 2014, 51, 833–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.J.; Lin, L.M. The Effects of Match-ups on the Consumer Attitudes toward Internet Celebrities and Their Live Streaming Contents in the Context of Product Endorsement. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 52, 101934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, M.S.; Massiah, C.A. When Customers Receive Support from Other Customers: Exploring the Influence of Intercustomer Social Support on Customer Voluntary Performance. J. Serv. Res. 2007, 9, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Sun, H.; Chang, Y. Effect of Social Support on Customer Satisfaction and Citizenship Behavior in Online Brand Communities: The Moderating Role of Support Source. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 31, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongkitrungrueng, A.; Assarut, N. The role of live streaming in building consumer trust and engagement with social commerce sellers. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 543–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.L.; Liang, X.J.; Xie, T.; Wang, H.Z. See now, act now: How to interact with customers to enhance social commerce engagement? Inf. Manag. 2020, 57, 103324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graupensperger, S.; Benson, A.J.; Kilmer, J.R.; Evans, M.B. Social (Un)distancing: Teammate Interactions, Athletic Identity, and Mental Health of Student-Athletes During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Adolesc. Health 2020, 67, 662–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagiwara, G.; Tsunokawa, T.; Iwatsuki, T.; Shimozono, H.; Kawazura, T. Relationships among student-athletes’ identity, mental health, and social support in Japanese student-athletes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shehadeh, N.; Rubens, M.; Attonito, J.; Jennings, T. Social Support and Its Impact on Ethnic Identity and HIV Risk among Migrant Workers. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2018, 5, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toyoshima, A.; Nakahara, J. The Effects of Familial Social Support Relationships on Identity Meaning in Older Adults: A Longitudinal Investigation. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 650051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.P.; Ho, Y.T.; Li, Y.W.; Turban, E. What drives social commerce: The role of social support and relationship quality. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2012, 16, 69–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Chaudhry, S.S. Enhancing consumer engagement in e-commerce live streaming via relational bonds. Internet Res. 2021, 30, 1019–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Cui, B.J.; Lyu, B. Influence of Streamer’s Social Capital on Purchase Intention in Live Streaming E-Commerce. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 748172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Qin, F.; Wang, G.A.; Luo, C. The impact of live video streaming on online purchase intention. Serv. Ind. J. 2020, 40, 656–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Xu, X.-Y.; Tayyab, S.M.U.; Li, Q. How the live streaming commerce viewers process the persuasive message: An ELM perspective and the moderating effect of mindfulness. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2021, 49, 101087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, C.; Wohn, D.Y. Predictors of parasocial interaction and relationships in live streaming. Convergence 2021, 27, 1714–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rungruangjit, W. What drives Taobao live streaming commerce? The role of parasocial relationships, congruence and source credibility in Chinese consumers’ purchase intentions. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; Chen, K.; Qi, J.; Li, J.; Yu, I.Y. Creating immersive and parasocial live shopping experience for viewers: The role of streamers’ interactional communication style. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2023, 17, 140–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alutaybi, A.; Al-Thani, D.; McAlaney, J.; Ali, R. Combating Fear of Missing Out (FoMO) on Social Media: The FoMO-R Method. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durao, M.; Etchezahar, E.; Genol, M.A.A.; Muller, M. Fear of Missing Out, Emotional Intelligence and Attachment in Older Adults in Argentina. J. Intell. 2023, 11, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, F.F.; Gu, F.F.; Palmatier, R.W. Online influencer marketing. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2022, 50, 226–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolega, L.; Rowe, F.; Branagan, E. Going digital? The impact of social media marketing on retail website traffic, orders and sales. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 60, 102501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Kim, D.-E. The influence of technological interactivity and media sociability on sport consumer value co-creation behaviors via collective efficacy and collective intelligence. Int. J. Sport. Mark. Spons. 2022, 23, 18–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherbourne, C.D.; Stewart, A.L. The MOS social support survey. Soc. Sci. Med. 1991, 32, 705–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohn, D.Y.; Freeman, G.; McLaughlin, C. Explaining viewers’ emotional, instrumental, and financial support provision for live streamers. In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Montreal, QC, Canada, 21–26 April 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, J.; Chen, M.; Yang, C.; Chung, T.; Lee, Y. Personality traits, interpersonal relationships, online social support, and Facebook addiction. Telemat. Inform. 2016, 33, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Y.; Jo, M.-S.; Sarigollü, E. Social Value and Content Value in Social Media: Two Paths to Psychological Well-being. J. Organ. Comput. Electron. Commer. 2017, 27, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Y.; Ertz, M.; Jo, M.-S.; Sarigollü, E. Social value, content value, and brand equity in social media brand communities: A comparison of Chinese and US consumers. Int. Mark. Rev. 2018, 35, 18–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, M.A.; Abrams, D. Social Identifications: A Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations and Group Processes, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 1988; pp. 6–56. [Google Scholar]

- Hogg, M.A.; Turner, J.C. Interpersonal attraction, social identification and psychological group formation. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 1985, 15, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stets, J.E.; Burke, P.J. Identity theory and social identity theory. Soc. Psychol. Q. 2000, 63, 224–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Mael, F. Social identity theory and the organization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papista, E.; Dimitriadis, S. Exploring consumer brand relationship quality and identification: Qualitative evidence from cosmetics brands. Qual. Mark. Res. 2012, 15, 33–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, H.G.; Jeseo, V.; Vincent, L.H. Promoting customer engagement in service settings through identification. J. Serv. Mark. 2021, 35, 473–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, H.R.; Loureiro, S.M.C.; Basile, G.; Vrontis, D. The increasing dynamics between consumers, social groups and brands. Qual. Mark. Res. 2012, 15, 404–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millán, Á.; Díaz, E. Analysis of consumers’ response to brand community integration and brand identification. J. Brand Manag. 2014, 21, 254–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahearne, M.; Bhattacharya, C.B.; Gruen, T. Antecedents and consequences of customer-company identification: Expanding the role of relationship marketing. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 574–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Browne, G.J.; Wetherbe, J.C. Why Do Internet Users Stick with a Specific Web Site? A Relationship Perspective. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2006, 10, 105–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.C.-C. Online Stickiness: Its Antecedents and Effect on Purchasing Intention. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2007, 26, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zott, C.; Amit, R.; Donlevy, J. Strategies for Value Creation in E-commerce: Best Practice in Europe. Eur. Manag. J. 2000, 18, 463–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lien, C.-H.; Cao, Y.; Zhou, X. Service Quality, Satisfaction, Stickiness, and Usage Intentions: An Exploratory Evaluation in the Context of WeChat services. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 68, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, H.-S.; Hsiao, K.-L. Youtube stickiness: The needs, personal, and environmental perspective. Internet Res. 2015, 25, 85–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.W.; Lin, C.P. To Stick or Not to Stick: The Social Response Theory in the Development of Continuance Intention from Organizational Cross-level Perspective. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2011, 27, 1963–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, Y.-H.; Chen, L.-F.; Chang, C.-C.; Chiu, F.-H. Configurational path to customer satisfaction and stickiness for a restaurant chain using fuzzy set qualitative comparative analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 2939–2949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.-T.; Wang, Y.-S.; Liu, E.-R. The stickiness intention of group-buying websites: The integration of the commitment–trust theory and e-commerce success model. Inf. Manag. 2016, 53, 625–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Guo, L.; Hu, M.; Liu, W. Influence of customer engagement with company social networks on stickiness: Mediating effect of customer value creation. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2017, 37, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rather, R.A.; Tehseen, S.; Parrey, S.H. Promoting customer brand engagement and brand loyalty through customer brand identification and value congruity. Span. J. Mark.-ESIC 2018, 22, 321–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladhari, R.; Massa, E.; Skandrani, H. Youtube vloggers popularity and influence: The roles of homophily, emotional attachment, and expertise. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 54, 102027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kock, F.; Berbekova, A.; Assaf, A.G. Understanding and managing the threat of common method bias: Detection, prevention and control. Tour. Manag. 2021, 86, 104330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuller, C.M.; Simmering, M.J.; Atinc, G.; Atinc, Y.; Babin, B.J. Common methods variance detection in business research. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3192–3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA; Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017; pp. 81–190. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Howard, M.C.; Nitzl, C. Assessing measurement model quality in PLS-SEM using confirmatory composite analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 109, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guha, A.; Bressgott, T.; Grewal, D.; Mahr, D.; Wetzels, M.; Schweiger, E. How artificiality and intelligence affect voice assistant evaluations. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigdon, E.E. Choosing PLS path modeling as analytical method in European management research: A realist perspective. Eur. Manag. J. 2016, 34, 598–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Constructs | Items | Respondents | Percentages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Streamer | Jiaqi Li | 132 | 47.1 |

| Viya | 87 | 31.1 | |

| Others | 61 | 21.8 | |

| Platform | Taobao | 222 | 79.3 |

| Douyin | 23 | 8.2 | |

| Others | 35 | 12.5 | |

| Gander | Male | 81 | 28.9 |

| Female | 199 | 71.1 | |

| Age (Years) | <20 | 18 | 6.4 |

| 20–29 | 193 | 68.9 | |

| 30–39 | 60 | 21.4 | |

| >39 | 9 | 3.2 | |

| Educational Background | ≤Middle school degree | 9 | 3.2 |

| Graduate | 169 | 60.4 | |

| ≥Masters | 102 | 36.4 | |

| Monthly Income (CNY) | <5000 | 145 | 51.8 |

| 5000–10,000 | 80 | 28.6 | |

| 10,001–15,000 | 36 | 12.9 | |

| 15,001–20,000 | 17 | 6.1 | |

| >20,000 | 2 | 0.7 | |

| Occupation | Students | 139 | 49.6 |

| Others | 141 | 50.4 |

| Constructs | Codes | Items | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Emotional Support | PES1 | The streamer would be on my side when I encountered difficulties | [17,24,36] |

| PES2 | The streamer would comfort and encourage me when I encountered difficulties | ||

| PES3 | The streamer would listen to me talk about my private feelings when I encountered difficulties | ||

| PES4 | The streamer would express their concerns for me when I encountered difficulties | ||

| Perceived Informational Support | PIS1 | The streamer would offer me suggestions to solve them when I encountered problems | [3,17,24] |

| PIS2 | The streamer would give me information on how to deal with them when I encountered problems | ||

| PIS3 | The streamer would help me discover the reasons and provide me with proposals when I encountered problems | ||

| PIS4 | The streamer would give me information to help me overcome them when I encountered problems | ||

| Perceived Financial Support | PFS1 | The streamers would help me save money when I intended to buy the recommended brands | [18,25,38] |

| PFS2 | I could buy the recommended brands with discounts, rebates, gifts, etc. with the help of the streamer | ||

| PFS3 | Compared to in other channels, the same brands recommended by the streamer have lower prices | ||

| PFS4 | I often receive some shopping red envelopes, coupons, vouchers, tokens, etc. from the streamer | ||

| Perceived Affectionate Support | PAS1 | A streamer who shows me love and affection is available | [36,61] |

| PAS2 | A streamer who makes me feel wanted and loved is available | ||

| PAS3 | A streamer who comforts me with love and affection is available | ||

| PAS4 | A streamer whom I can count on to listen to me when I need to talk is available | ||

| Perceived Social Network Support | PSNS1 | Connecting with others for a good time via the streamer is available | [10,36] |

| PSNS2 | Getting together with others via the streamer for relaxation is available | ||

| PSNS3 | Doing something enjoyable with others via the streamer is available | ||

| Consumer–Streamer Identification | CSI1 | I am proud to be the streamer’s follower | [7,10,12,47] |

| CSI2 | The streamer represents values that are important to me | ||

| CSI3 | My values are similar to the streamer’s values | ||

| CSI4 | The streamer is a model for me to follow | ||

| CSI5 | The streamer is the sort of person I want to be like myself | ||

| CSI6 | Sometimes I wish I could be more like the streamer | ||

| CSI7 | The streamer is someone I would like to emulate | ||

| CSI8 | I would like to do the kinds of things the streamer does | ||

| CSI9 | My personality and the streamer’s personality are very similar | ||

| CSI10 | I have a lot in common with the streamer | ||

| CSI11 | I feel an overlap between my self-image and the streamer’s image | ||

| Consumer–Streamer Stickiness | CSS1 | I view the steamer’s live streaming studio almost every day | [7,12,54] |

| CSS2 | I am in the habit of viewing new contents on the streamer’s live streaming studio while accessing the internet | ||

| CSS3 | I visit the streamer’s posts frequently | ||

| CSS4 | I watch the streamer’s live steaming sales for a long time | ||

| CSS5 | I usually spend a lot of time watching the streamer’s channels | ||

| CSS6 | I intend to prolong my stays on the streamer’s live streaming studio | ||

| Consumer–Brand Stickiness | CBS1 | I would stay a longer time on the brands in live streaming sales | [7,12,54] |

| CBS2 | I would view the brand’s live streaming sales as often as I can | ||

| CBS3 | I intend to view the brand’s live streaming sales once noticed in advance | ||

| CBS4 | I intend to prolong my stays on the brand’s live streaming sales | ||

| CBS5 | I browse this brand in live streaming sales almost everyday | ||

| CBS6 | I am in the habit of looking for the brand’s live streaming sales while accessing the internet |

| Constructs | Items | SFL | CR | AVE | α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Emotional Support | PES1 | 0.885 | 0.942 | 0.802 | 0.939 |

| PES2 | 0.902 | ||||

| PES3 | 0.904 | ||||

| PES4 | 0.892 | ||||

| Perceived Informational Support | PIS1 | 0.870 | 0.927 | 0.760 | 0.919 |

| PIS2 | 0.845 | ||||

| PIS3 | 0.904 | ||||

| PIS4 | 0.868 | ||||

| Perceived Financial Support | PFS1 | 0.787 | 0.899 | 0.690 | 0.884 |

| PFS2 | 0.876 | ||||

| PFS3 | 0.862 | ||||

| PFS4 | 0.794 | ||||

| Perceived Affectionate Support | PAS1 | 0.878 | 0.941 | 0.800 | 0.932 |

| PAS2 | 0.892 | ||||

| PAS3 | 0.907 | ||||

| PAS4 | 0.901 | ||||

| Perceived Social Network Support | PSNS1 | 0.859 | 0.886 | 0.722 | 0.865 |

| PSNS2 | 0.812 | ||||

| PSNS3 | 0.877 | ||||

| Consumer–Streamer Identification | CSI1 | 0.921 | 0.981 | 0.822 | 0.974 |

| CSI2 | 0.894 | ||||

| CSI3 | 0.918 | ||||

| CSI4 | 0.906 | ||||

| LSI5 | 0.883 | ||||

| CSI6 | 0.901 | ||||

| CSI7 | 0.927 | ||||

| CSI8 | 0.914 | ||||

| CSI9 | 0.897 | ||||

| CSI10 | 0.913 | ||||

| CSI11 | 0.898 | ||||

| Consumer–Streamer Stickiness | CSS1 | 0.915 | 0.963 | 0.814 | 0.941 |

| CSS2 | 0.924 | ||||

| CSS3 | 0.877 | ||||

| CSS4 | 0.892 | ||||

| CSS5 | 0.917 | ||||

| CSS6 | 0.887 | ||||

| Consumer–Brand Stickiness | CBS1 | 0.902 | 0.960 | 0.800 | 0.946 |

| CBS2 | 0.905 | ||||

| CBS3 | 0.874 | ||||

| CBS4 | 0.882 | ||||

| CBS5 | 0.895 | ||||

| CBS6 | 0.908 |

| Constructs | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Perceived Emotional Support | 0.896 | |||||||

| 2. Perceived Informational Support | 0.620 | 0.872 | ||||||

| 3. Perceived Financial Support | 0.581 | 0.679 | 0.831 | |||||

| 4. Perceived Affectionate Support | 0.447 | 0.523 | 0.651 | 0.894 | ||||

| 5. Perceived Social Network Support | 0.488 | 0.498 | 0.581 | 0.429 | 0.850 | |||

| 6. Consumer–Streamer Identification | 0.390 | 0.567 | 0.723 | 0.586 | 0.639 | 0.907 | ||

| 7. Consumer–Streamer Stickiness | 0.418 | 0.537 | 0.711 | 0.602 | 0.647 | 0.683 | 0.902 | |

| 8. Consumer–Brand Stickiness | 0.395 | 0.575 | 0.613 | 0.549 | 0.581 | 0.498 | 0.514 | 0.894 |

| Constructs | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Perceived Emotional Support | - | |||||||

| 2. Perceived Informational Support | 0.497 | - | ||||||

| 3. Perceived Financial Support | 0.469 | 0.536 | - | |||||

| 4. Perceived Affectionate Support | 0.387 | 0.373 | 0.574 | - | ||||

| 5. Perceived Social Network Support | 0.462 | 0.395 | 0.493 | 0.516 | - | |||

| 6. Consumer–Streamer Identification | 0.312 | 0.491 | 0.698 | 0.482 | 0.585 | - | ||

| 7. Consumer–Streamer Stickiness | 0.305 | 0.412 | 0.664 | 0.504 | 0.521 | 0.554 | - | |

| 8. Consumer–Brand Stickiness | 0.328 | 0.429 | 0.527 | 0.418 | 0.436 | 0.351 | 0.379 | - |

| Hypotheses | β | f2 | R2 | Q2 | ρ | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSI | 0.558 | 0.442 | ||||

| H1a: PES→CSI | 0.528 | 0.252 | *** | Support | ||

| H1b: PIS→CSI | 0.317 | 0.151 | ** | Support | ||

| H1c: PFS→CSI | 0.471 | 0.214 | *** | Support | ||

| H1d: PAS→CSI | 0.619 | 0.303 | *** | Support | ||

| H1e: PSNS→CSI | 0.003 | 0.011 | 0.832 | Reject | ||

| CSS | 0.514 | 0.386 | ||||

| H2a: CSI→CSS | 0.717 | 0.352 | *** | Support | ||

| CBS | 0.544 | 0.395 | ||||

| H2b: CSI→CBS | 0.598 | 0.277 | *** | Support | ||

| H3: CSS→CBS | 0.311 | 0.154 | ** | Support |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jiao, Y.; Sarigöllü, E.; Lou, L.; Huang, B. How Streamers Foster Consumer Stickiness in Live Streaming Sales. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2023, 18, 1196-1216. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer18030061

Jiao Y, Sarigöllü E, Lou L, Huang B. How Streamers Foster Consumer Stickiness in Live Streaming Sales. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research. 2023; 18(3):1196-1216. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer18030061

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiao, Yongbing, Emine Sarigöllü, Liguo Lou, and Baotao Huang. 2023. "How Streamers Foster Consumer Stickiness in Live Streaming Sales" Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 18, no. 3: 1196-1216. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer18030061

APA StyleJiao, Y., Sarigöllü, E., Lou, L., & Huang, B. (2023). How Streamers Foster Consumer Stickiness in Live Streaming Sales. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 18(3), 1196-1216. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer18030061