Wearable and Portable GPS Solutions for Monitoring Mobility in Dementia: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Dementia

1.2. GPS-Derived Mobility Data as a Potential Tool in Clinical Decision Making

1.3. Use of GPS in Patients with Dementia

1.4. Processing Tools and Algorithms Used for GPS Data Analysis

1.5. Assessing the Breadth of Mobility Measures Applied in the Dementia Literature

1.6. Contribution of This Paper to the Literature

- To describe the use of GPS in dementia care and management;

- To identify the extent to which wearable solutions have been used;

- To assess the quality of the studies identified using the conceptual Fillekes framework.

2. Materials and Methods

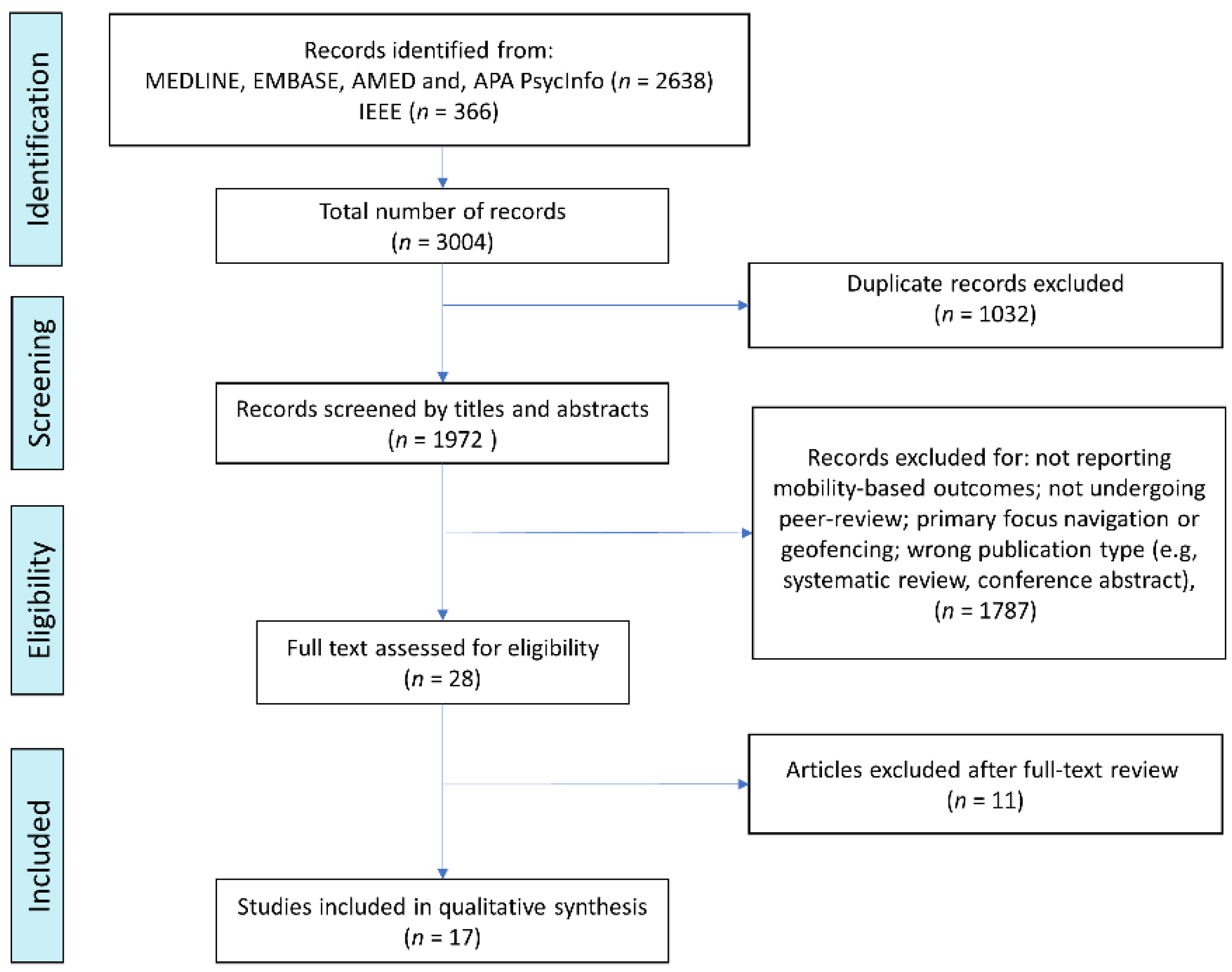

2.1. Contribution of This Paper to the Literature

2.2. Eligibility

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Data Extraction and Study Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

3.2. GPS Data Processing

3.3. GPS-Derived Mobility Indicators

4. Discussion

4.1. Overall Findings

4.2. Mobility Behaviour of PwD

4.3. GPS-Derived Outcomes and Processing Methods

4.4. The Extent to Which Wearable Solutions Have Been Used

4.5. Device Use and Acceptability in PwD

4.6. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wittenberg, R.; Hu, B.; Barraza-Araiza, L.; Funder, A.R. Projections of Older People with Dementia and Costs of Dementia Care in the United Kingdom, 2019–2040; London School of Economics: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Status Report on the Public Health Response to Dementia; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; p. 251. [Google Scholar]

- Gustavsson, A.; Svensson, M.; Jacobi, F.; Allgulander, C.; Alonso, J.; Beghi, E.; Dodel, R.; Ekman, M.; Faravelli, C.; Fratiglioni, L.; et al. Cost of Disorders of the Brain in Europe 2010. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011, 21, 718–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jellinger, K.A. Recent Update on the Heterogeneity of the Alzheimer’s Disease Spectrum. J. Neural Transm. 2021, 129, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nutt, J.G. Higher-Level Gait Disorders: An Open Frontier. Mov. Disord. 2013, 28, 1560–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Alphen, H.; Volkers, K.M.; Blankevoort, C.G.; Scherder, E.J.A.; Hortobágyi, T.; Van Heuvelen, M.J.G. Older Adults with Dementia Are Sedentary for Most of the Day. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0152457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hope, T.; Keene, J.; McShane, R.H.; Fairburn, C.G.; Gedling, K.; Jacoby, R. Wandering in Dementia: A Longitudinal Study. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2001, 13, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teahan, Á.; Lafferty, A.; Cullinan, J.; Fealy, G.; O’Shea, E. An Analysis of Carer Burden Among Family Carers of People with and Without Dementia in Ireland. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2021, 33, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuignet, T.; Perchoux, C.; Caruso, G.; Klein, O.; Klein, S.; Chaix, B.; Kestens, Y.; Gerber, P. Mobility Among Older Adults: Deconstructing the Effects of Motility and Movement on Wellbeing. Urban Stud. 2020, 57, 383–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Li, Q.; Chen, Y.; Xie, X.; Ma, W.-Y. Understanding Mobility Based on GPS Data; ACM Digital Library: New York, NY, USA, 2008; ISBN 9781605581361. [Google Scholar]

- Hinrichs, T.; Zanda, A.; Fillekes, M.P.; Bereuter, P.; Portegijs, E.; Rantanen, T.; Schmidt-Trucksäss, A.; Zeller, A.W.; Weibel, R. Map-Based Assessment of Older adults’ Life Space: Validity and Reliability. Eur. Rev. Aging Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portegijs, E.; Tsai, L.-T.; Rantanen, T.; Rantakokko, M. Moving through Life-Space Areas and Objectively Measured Physical Activity of Older People. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0135308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, K.D.; Sawyer, P.; Ritchie, C.S.; Allman, R.M.; Brown, C.J. Life-Space Mobility Predicts Nursing Home Admission Over 6 Years. J. Aging Health 2013, 25, 907–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.; Rodriguez, M.A.; Al Snih, S. Life-Space Mobility in the Elderly: Current Perspectives. Clin. Interv. Aging 2020, 15, 1665–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stalvey, B.T.; Owsley, C.; Sloane, M.E.; Ball, K. The Life Space Questionnaire: A Measure of the Extent of Mobility of Older Adults. J. Appl. Gerontol. 1999, 18, 460–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, P.S.; Bodner, E.V.; Allman, R.M. Measuring Life-Space Mobility in Community-Dwelling Older Adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2003, 51, 1610–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tinetti, M.E.; Ginter, S.F. The Nursing Home Life-Space Diameter. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1990, 38, 1311–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, D.; Nayak, U.S.L.; Isaacs, B. The Life-Space Diary: A Measure of Mobility in Old People at Home. Int. Rehabil. Med. 1985, 7, 182–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fillekes, M.P.; Kim, E.-K.; Trumpf, R.; Zijlstra, W.; Giannouli, E.; Weibel, R. Assessing Older Adults’ Daily Mobility: A Comparison of GPS-Derived and Self-Reported Mobility Indicators. Sensors 2019, 19, 4551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Duval, C.; Boissy, P.; Montero-Odasso, M.; Zou, G.; Jog, M.; Speechley, M. Comparing GPS-Based Community Mobility Measures with Self-Report Assessments in Older Adults with Parkinson’s Disease. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 2020, 75, 2361–2370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boissy, P.; Blamoutier, M.; Brière, S.; Duval, C. Quantification of Free-Living Community Mobility in Healthy Older Adults Using Wearable Sensors. Front. Public Health 2018, 6, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorpe, J.; Forchhammer, B.H.; Maier, A.M. Adapting Mobile and Wearable Technology to Provide Support and Monitoring in Rehabilitation for Dementia: Feasibility Case Series. JMIR Form. Res. 2019, 3, e12346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorpe, J.R.; Forchhammer, B.H.; Maier, A.M. Development of a Sensor-Based Behavioral Monitoring Solution to Support Dementia Care. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2019, 7, e12013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, R.; Kim, J.-M. An Effective Approach to Improving Low-Cost GPS Positioning Accuracy in Real-Time Navigation. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, 671494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Vorlíček, M.; Stewart, T.; Schipperijn, J.; Burian, J.; Rubín, L.; Dygrýn, J.; Mitáš, J.; Duncan, S. Smart Watch Versus Classic Receivers: Static Validity of Three GPS Devices in Different Types of Built Environments. Sensors 2021, 21, 7232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, S.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, P. Applications of Titanium in the Electronic Industry. Titan. Consum. Appl. 2019, 2019, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, S.; Auslander, G.K.; Shoval, N.; Gitlitz, T.; Landau, R.; Heinik, J. Caregiving Burden and Out-of-Home Mobility of Cognitively Impaired Care-Recipients Based on GPS Tracking. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2012, 24, 1836–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, J.Y.; Rose, R.V.; Gammada, E.; Lam, I.; Roy, E.A.; Black, S.E.; Poupart, P. Measuring Life Space in Older Adults with Mild-to-Moderate Alzheimer’s Disease Using Mobile Phone GPS. Gerontology 2014, 60, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Free GPS Online Post Processing Services—GIS Resources. Available online: https://gisresources.com/Free-Gps-Online-Post-Processing-Services/ (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Milne, H.; van der Pol, M.; McCloughan, L.; Hanley, J.; Mead, G.; Starr, J.; Sheikh, A.; McKinstry, B. The Use of Global Positional Satellite Location in Dementia: A Feasibility Study for a Randomised Controlled Trial. BMC Psychiatry 2014, 14, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabiri, S.; Marković, N.; Heaslip, K.; Reddy, C. A Deep Convolutional Neural Network Based Approach for Vehicle Classification Using Large-Scale GPS Trajectory Data. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2020, 116, 102644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, L.; Yamamoto, T.; Morikawa, T. Identification of Activity Stop Locations in GPS Trajectories by DBSCAN-TE Method Combined with Support Vector Machines. Transp. Res. Procedia 2018, 32, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoval, N.; Wahl, H.-W.; Auslander, G.; Isaacson, M.; Oswald, F.; Edry, T.; Landau, R.; Heinik, J. Use of the Global Positioning System to Measure the Out-of-Home Mobility of Older Adults with Differing Cognitive Functioning. Ageing Soc. 2011, 31, 849–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fillekes, M.P.; Giannouli, E.; Kim, E.-K.; Zijlstra, W.; Weibel, R. Towards a Comprehensive Set of GPS-Based Indicators Reflecting the Multidimensional Nature of Daily Mobility for Applications in Health and Aging Research. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2019, 18, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evidence|Dementia: Assessment, Management and Support for People Living with Dementia and Their Carers|Guidance|NICE. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng97/Evidence (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Kaspar, R.; Oswald, F.; Wahl, H.-W.; Voss, E.; Wettstein, M. Daily Mood and Out-of-Home Mobility in Older Adults. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2015, 34, 26–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oswald, F.; Wahl, H.-W.; Voss, E.; Schilling, O.; Freytag, T.; Auslander, G.; Shoval, N.; Heinik, J.; Landau, R. The Use of Tracking Technologies for the Analysis of Outdoor Mobility in the Face of Dementia: First Steps into a Project and Some Illustrative Findings from Germany. J. Hous. Elder. 2010, 24, 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahl, H.-W.; Wettstein, M.; Shoval, N.; Oswald, F.; Kaspar, R.; Issacson, M.; Voss, E.; Auslander, G.; Heinik, J. Interplay of Cognitive and Motivational Resources for Out-of-Home Behavior in a Sample of Cognitively Heterogeneous Older Adults: Findings of the SenTra Project. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2012, 68, 691–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wettstein, M.; Wahl, H.-W.; Shoval, N.; Auslander, G.; Oswald, F.; Heinik, J. Cognitive Status Moderates the Relationship Between Out-of-Home Behavior (OOHB), Environmental Mastery and Affect. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2014, 59, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wettstein, M.; Seidl, U.; Wahl, H.-W.; Shoval, N.; Heinik, J. Behavioral Competence and Emotional Well-Being of Older Adults with Mild Cognitive Impairment. GeroPsych 2014, 27, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wettstein, M.; Wahl, H.-W.; Shoval, N.; Auslander, G.; Oswald, F.; Heinik, J. Identifying Mobility Types in Cognitively Heterogeneous Older Adults Based on GPS-Tracking. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2013, 34, 1001–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wettstein, M.; Wahl, H.-W.; Shoval, N.; Oswald, F.; Voss, E.; Seidl, U.; Frölich, L.; Auslander, G.; Heinik, J.; Landau, R. Out-of-Home Behavior and Cognitive Impairment in Older Adults. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2012, 34, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoval, N.; Auslander, G.K.; Freytag, T.; Landau, R.; Oswald, F.; Seidl, U.; Wahl, H.W.; Werner, S.; Heinik, J. The use of advanced tracking technologies for the analysis of mobility in Alzheimer’s disease and related cognitive diseases. BMC Geriatr. 2008, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, K.; Lee, S.; Lee, S.; Bae, S.; Harada, K.; Shimada, H. Environmental Predictors of Objectively Measured Out-of-Home Time Among Older Adults with Cognitive Decline. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2019, 82, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayat, S.; Mihailidis, A. Outdoor Life in Dementia: How Predictable Are People with Dementia in Their Mobility? Alzheimer’s Dement. Diagn. Assess. Dis. Monit. 2021, 13, e12187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayat, S.; Naglie, G.; Rapoport, M.J.; Stasiulis, E.; Chikhaoui, B.; Mihailidis, A. Inferring Destinations and Activity Types of Older Adults from GPS Data: Algorithm Development and Validation. JMIR Aging 2020, 3, e18008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, J.; Boyle, J.; Pretzer-Aboff, I.; Knoefel, J.; Young, H.M.; Wheeler, D.C. Using a GPS Watch to Characterize Life-Space Mobility in Dementia: A Dyadic Case Study. J. Gerontol. Nurs. 2021, 47, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liddle, J.; Ireland, D.; Krysinska, K.; Harrison, F.; Lamont, R.; Karunanithi, M.; Kang, K.; Reppermund, S.; Sachdev, P.S.; Gustafsson, L.; et al. Lifespace Metrics of Older Adults with Mild Cognitive Impairment and Dementia Recorded via Geolocation Data. Australas. J. Ageing 2021, 40, e341–e346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sturge, J.; Klaassens, M.; Lager, D.; Weitkamp, G.; Vegter, D.; Meijering, L. Using the Concept of Activity Space to Understand the Social Health of Older Adults Living with Memory Problems and Dementia at Home. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 288, 113208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayat, S.; Naglie, G.; Rapoport, M.J.; Stasiulis, E.; Widener, M.J.; Mihailidis, A. A GPS-Based Framework for Understanding Outdoor Mobility Patterns of Older Adults with Dementia: An Exploratory Study. Gerontology 2021, 68, 106–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vívoactive HR—Specifications. Available online: https://www8.garmin.com/manuals/webhelp/vivoactivehr/EN-US/GUID-A83D50A0-AB1C-4A7B-824A-465FAB065925.html?Msclkid=bc44a015a5d111ec93152998eed292d3 (accessed on 17 March 2022).

- BT-Q1000XT. Available online: http://www.qstarz.com/Products/GPSProducts/BT-Q1000XT-F.Htm (accessed on 17 March 2022).

- Bohte, W.; Maat, K. Deriving and Validating Trip Purposes and Travel Modes for Multi-Day GPS-Based Travel Surveys: A Large-Scale Application in the Netherlands. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2009, 17, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furletti, B.; Cintia, P.; Renso, C.; Spinsanti, L. Inferring human activities from GPS tracks. In Proceedings of the 2nd ACM SIGKDD International Workshop on Urban Computing ’13, Chicago, IL, USA, 11 August 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadwen, T.; Smallbon, V.; Zhang, Q.; D’Souza, M. Energy Efficient LoRa GPS Tracker for Dementia Patients. In Proceedings of the 2017 39th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), Jeju, Korea, 11–15 July 2017; pp. 771–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzmeier, A.; Besser, J.; Weigel, R.; Fischer, G.; Kissinger, D. A Compact Back-Plaster Sensor Node for Dementia and Alzheimer Patient Care. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Sensors Applications Symposium (SAS), Queenstown, New Zealand, 18–20 February 2014; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megges, H.; Freiesleben, S.D.; Rösch, C.; Knoll, N.; Wessel, L.; Peters, O. User Experience and Clinical Effectiveness with Two Wearable Global Positioning System Devices in Home Dementia Care. Alzheimer’s Dement. Transl. Res. Clin. Interv. 2018, 4, 636–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prümper, J. Der Benutzungsfragebogen ISONORM 9241/10: Ergebnisse zur Reliabilität und Validität. In Software-Ergonomie; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1997; pp. 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freiesleben, S.D.; Megges, H.; Herrmann, C.; Wessel, L.; Peters, O. Overcoming Barriers to the Adoption of Locating Technologies in Dementia Care: A Multi-Stakeholder Focus Group Study. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Øderud, T.; Landmark, B.; Eriksen, S.; Fossberg, A.B.; Aketun, S.; Omland, M.; Hem, K.-G.; Østensen, E.; Ausen, D. Persons with Dementia and Their Caregivers Using GPS. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2015, 217, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author (Year) | Study Population | Device(s) and Location Carried | Duration | Sampling Frequency | Study Design | GPS-Derived Outcomes | Data Processing Details | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oswald et al. [38] (2010) | PwD n = 6, MCI n = 6, HC n = 7 (Participants between age 63–80). | SenTra device: GPS receiver, a RF transmitter wristwatch, and a home RF monitoring system [44]. Location: GPS device located in pouch or bag [44]. | 4 weeks | 0.2 Hz | Observational, cross-sectional study | Distance travelled, Walking speed, Distance from home, Daily mobility activity | The GPS data were transmitted via the GPRS protocol to a project server. A valid hour was ≥30 min of valid GPS data; a day was valid only if there were no invalid hours. Full time analysis was carried out on valid days (methodology of processing was not stated). | This study established that the future proposed SenTra project was feasible. However, the SenTra tracking kit placed high cognitive and behavioural demands on participants. |

| Shoval et al. [33] (2011) | PwD n = 7 (mean age 81.9), MCI n = 21 (mean age 78.3), HC n = 13 (mean age 72.9). | SenTra kit [44] | 4 weeks | 0.1 Hz | Observational, cross-sectional study | Distance from home, Time OOH | GPS data transmitted via the GPRS protocol to a project server. Using a combination of a GIS and the recorded locations of the participant, the distance from home was calculated. This information was visualized on a ‘spider-web diagram.’ | Participants with cognitive impairment travelled shorter distances from home during the day compared with HCs. PwD had a smaller spatial range compared to those with MCI. |

| Werner et al. [27] (2012) | PwD n = 16, MCI n = 34, HC n = 26, CG n = 66 (Participants aged 63 or older). | SenTra kit [44] | 4 weeks | 0.1 Hz | Observational, cross-sectional study | Time spent OOH per day, Time spent walking per day, Number of visited nodes, Number of walking tracks per day, Average walking distance, Average walking speed | GPS data transmitted via the GPRS protocol to a project server. From GPS data a node was defined as a stopping point lasting >5 min. A track was the pathway between nodes. Detail was not presented on the processing methods to gather GPS derived outcomes. | The greater the mobility of PwD (with mobility defined through the GPS derived outcomes), the less burden placed on CGs. |

| Wahl et al. [39] (2013) | MCI n = 76 (mean age 72.9), HC n = 146 (mean age 72.5). | SenTra kit [44] | 4 weeks | 0.1 Hz | Observational, cross-sectional study | Time spent OOH per day, Number of visited locations | A valid day was when <1 h of missing data was observed. A visited location was defined as a GPS coordinate staying in the same location for >5 min. | The mean number of visited locations was higher in HCs than those with MCI. |

| Tung et al. [28] (2014) | PwD n = 19 (mean age 70.7), HC n = 33 (mean age 73.7). | GPS receiver on smartphone chipset (Qualcomm RTR6285, Qualcomm Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) Location: Pocket | 3–5 days | 1 Hz | Observational, cross-sectional study | Life-space area, Distance from home, Time OOH | GPS coordinates were projected to a 2D plane using Matlab R12. Home radius was set to 25 m around home coordinates determined from the participants address and Google Earth. A convex hull, calculated using the standard convex hull operation, was used to determine the area and perimeter measures. The Euclidean distance from the home coordinates was calculated and a distance time series was produced to determine the time spent OOH and distance from home were calculated. | Reduced mobility was observed in PwD compared to HCs, using measurements of the area and perimeter of the convex hull. |

| Wettstein et al. [40] (2014a) | PwD n = 35 (mean age 74.1), MCI n = 76 (mean age 72.9), HC n = 146 (mean age 72.5) | SenTra kit [44] | 4 weeks | 0.2 Hz | Observational, cross-sectional study | Walking distance, Walking speed, Walking duration, Time spent OOH, Number of places visited, Number of walking tracks per day | GPS data transmitted via the GPRS protocol to a project server. A valid day had to have OOH behaviour and <1 h of missing GPS data. A visited location was defined as GPS coordinates in the same location for >5 min. A walking track was considered as movement less than 5 km/h. | In PwD, higher walking distance and walking speed were positively correlated with environmental mastery (how capable an individual feels with using environmental resources). |

| Wettstein et al. [41] (2014b) | As per Wettstein et al. [40] | SenTra kit [44] | 4 weeks | 0.2 Hz | Observational, cross-sectional study | Time spent OOH, Number of places visited | The same data processing method was used as per Wettstein et al. [40]. However, the walking tracks were not processed as this was not a GPS derived outcome for this study. | Behavioural competence was significantly lower in PwD than both MCI and HC. The mean number of activities carried out was also lower in PwD compared with MCI and HCs. |

| Kaspar et al. [37] (2015) | PwD n = 16, MCI n = 30, HC n = 95 (Participants were in the age range 50–84). | SenTra kit [44] | 4 weeks | 0.2 Hz | Case Control study | Time spent OOH, Average walking distance, Type of activity, Type of transport | The GPS data were transmitted via the GPRS protocol to a project server. A valid day had <1 h of missing data. Spatial GPS data was interpreted using complex algorithms (specific type not stated), which integrated compound measures, such as acceleration and velocity, alongside geographical background data to distinguish transport modes. | The authors were unable to establish a strong relationship between daily mood and an individual’s mobility. |

| Wettstein et al. [42] (2015a) | As per Wettstein et al. [40] | SenTra kit [44] | 4 weeks | 0.2 Hz | Observational, cross-sectional study | Walking distance, Walking speed, Walking duration, Time spent OOH, Number of places visited, Number of walking tracks per day | The same data processing method was used as Wettstein et al. [40]. An addition of this study was the cluster method which used GPS-derived outcomes to identify whether the participants were ‘mobility restricted’, ‘outdoor oriented’ or ‘walkers’. | The mobility patterns in older people were heterogenous. However, it was identified that there was a higher proportion of cognitively impaired individuals in the cluster defined as having restricted mobility. |

| Wettstein et al. [43] (2015b) | As per Wettstein et al. [40] | SenTra kit [44] | 4 weeks | 0.2 Hz | Observational, cross-sectional study | Walking distance, Walking speed, Walking duration, Time spent OOH, Number of places visited, Number of walking tracks per day | Data processing method the same as Wettstein et al. [40] | The three cognitive ability groups did not significantly differ in OOH walking indicators (e.g., walking speed). However, OOH mobility indicators (time OOH, number of visited locations) were lowest in PwD. |

| Harada et al. [45] (2019) | PwD n = 147 (The mean age of the n = 192 baseline participants was 76.3 but the age was not stated for those included in the final study) | Globalsat DG-200 Data Logger Location: Pocket | 2 weeks | 0.033 Hz | Secondary analysis of a randomised controlled trial | Time spent OOH per day | GPS data was processed in accordance with the GIS system (ArcGIS for Desktop 10.3: Esri Japan Incorporation: Tokyo, Japan). Home radius set to 100 m around the home coordinates; the time spent OOH was determined using this radius. Validity of a day was defined as wear ≥10 h, location started and ended in the home area, no poor connection during the time OOH and, the participant stated they wore the device in their travel diary. | In PwD, a stronger social network was positively correlated with greater time spent OOH. However, no relationship between environmental factors and time spent OOH was observed in PwD. |

| Thorpe et al. [22] (2019) | PwD n = 6 (Mean age 69.7) | Smartphone (Nexus 5) and a Smartwatch (Sony Smartwatch 3) Location: Pocket (smartphone) and Wrist (smartwatch). | 8 weeks | Ranging from 1000 Hz to 0.003 Hz | Longitudinal study | MCP, Action range, Total distance covered outside the home, Time spent OOH, Time spent moving between locations, Number of places visited, Number of trips | The GPS data was filtered in alignment with the upper limit set at 25 m accuracy. The stop and moves were determined from the trajectory with the DBSCAN method applied to determine locations. A stop was defined as GPS coordinates in the same location for >5 min. The MCP was calculated using the R function to determine the smallest convex polygon around the data points. The action range was the geodesic distance from home coordinates and the GPS data [23]. | Digital monitoring of mobility and activity has the potential to detect fluctuations in behaviour that the participant might not detect themselves. |

| Bayat et al. [46] (2021) | PwD n = 7, HC n = 8 (All participants were ≥65 or older). | SafeTracks Prime Mobile GPS Device Location: Pocket | 8 weeks | 0.017 Hz | Case control study | Number of destinations, Sequence of destinations, Time spent at each destination | 4 of the 8 weeks of captured GPS data were extracted. Home location of each participant was determined using DBSCAN algorithm. The trajectory segmentation method [47] extracted the locations visited by each participant. Extracted destinations were clustered and each destination was assigned a cluster ID [47]. Different entropy methods (random, heterogeneous spatial and spatiotemporal) and algorithms were used to assess randomness of individuals mobility. | There was lower spatial and temporal randomness in mobility patterns in PwD compared to HC. Therefore, across the collected data there was a 5% chance, on average, that a PwD would choose a location at random but an 8% chance in HC. |

| Chung et al. [48] (2021) | PwD n = 1, CG n = 1 (PwD 64, CG 62) | Garmin™ Vivoactive HR Location: wrist watch | 1 week | Not stated | Case study | Total distance moved, Movement speed, Convex hull area, Total wear time, Location (home vs. other), Total time OOH, Total time at home, Heart rate | The GPS data were extracted in TCX and CSV formats. The participant wore the device longer than the intended 7-day study period therefore generating 9 days of complete GPS data. GPS track plots used to describe locations visited with total distance moved and speed of movement determined for each track. LSM visualized by plotting and calculating the convex hull of GPS points using mapview package (CITE). Home radius was set as ≤1000 ft around home coordinates. | The participant engaged in OOH activities every day from late morning until the evening. The travel diary correlated with the GPS-derived outcomes and provided additional information on the type of activity the participant carried out. |

| Liddle et al. [49] (2021) | PwD n = 3, MCI n = 15 (Participants mean age 86.7) | Smartphone based GPS system Location: Pocket | Required 105 to 240 h of GPS data. | Not stated | Longitudinal observational study | Life space area, Time at home, Maximum distance from home, Trips OOH, Time left at home | Custom algorithms (not stated) were used to create metrics. The locations extracted from the GPS data were plotted to visualize the life space area and the shape and perimeter of the life space area were analysed. The home area was defined as 500 m from the home location and the time spent OOH was when the participant left the home radius and did not return for a period > 5 min. | The authors found no relationship between life space and cognition. However, an association with life space and driving status was found with non-drivers having a lower life space compared with drivers. |

| Sturge et al. [50] (2021) | PwD n = 2, MCI n = 5 (Participants were aged 59–93). | QStarz BT—1000X | 2 weeks | Not stated | Observational, cross-sectional study | Visited locations, Distance from home, Life Space Area | GPS data extracted and processed in Microsoft Excel then imported into V-Analytics to store the participants locations and trips over the study period and for time-space movement analysis. Activities were created if GPS location points were connected within an 80 m radius for >5 min. GPS locations exceeding this radius were considered as a distinct trip. Activities were imported into ArcMap 10.5.1. to visualize participants’ spatial movement with activities then defined into routine activity space (<7.5 km of the home coordinates) and occasional activity space (>7.5 km). | Cognitively impaired individuals still engaged in activities beyond their neighbourhood area. |

| Bayat et al. [51] (2022) | PwD n = 7, HC n = 8 (All participants were ≥ 65). | SafeTracks Prime Mobile GPS device Location: Pocket, purse or bag | 4 weeks | Not stated | Case control study | Maximum distance from home, Radius of gyration, Life space area, Number of destinations, Number of unique destinations, Time at home, Time OOH, Time on foot, Time in vehicle, Trip time period, Total number of trips, Outdoor activity duration, Types of activities | Data processing as described by Bayat et al. was used in this study [46]. A distance-based probabilistic model based on Google places, API, was used to retrieve information about visited locations of the participants to define their OOH activities (i.e., shopping, leisure, medical services). | PwD undertook more medical-related and fewer sport-related activities compared to HCs. PwD spent less time walking than cognitively intact individuals. |

| Study | Space | Time | Movement Scope | Attribute | Total Number of Outcomes | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Extent | Shape/Distribution | Duration | Timing | Temporal Distribution | Stop | Move | Trajectory | Out of Home | Transport Mode | Further Attribute | ||

| Oswald et al. (2010) [38] | ● | ● | ● | 3 | |||||||||

| Shoval et al. (2011) [33] | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | 5 | |||||||

| Werner et al. (2012) [27] | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | 6 | ||||||

| Wahl et al. (2013) [39] | ● | ● | ● | ● | 4 | ||||||||

| Tung et al. (2014) [28] | ● | ● | ● | ● | 4 | ||||||||

| Wettstein et al. (2014a) [40] | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | 6 | ||||||

| Wettstein et al. (2014b) [41] | ● | ● | ● | ● | 4 | ||||||||

| Kaspar et al. (2015) [37] | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | 7 | |||||

| Wettstein et al. (2015a) [42] | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | 6 | ||||||

| Wettstein et al. (2015b) [43] | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | 6 | ||||||

| Harada et al. (2019) [45] | ● | ● | ● | 3 | |||||||||

| Thorpe et al. (2019) [22] | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | 7 | |||||

| Bayat et al. (2021) [46] | ● | ● | ● | ● | 4 | ||||||||

| Chung et al. (2021) [48] | ● | ● | ● | ● | 4 | ||||||||

| Liddle et al. (2021) [49] | ● | ● | ● | ● | 4 | ||||||||

| Sturge et al. (2021) [50] | ● | ● | ● | ● | 4 | ||||||||

| Bayat et al. (2022) [51] | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | 11 | |

| Total number of studies per category | 9 | 8 | 0 | 15 | 2 | 2 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 14 | 2 | 7 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cullen, A.; Mazhar, M.K.A.; Smith, M.D.; Lithander, F.E.; Ó Breasail, M.; Henderson, E.J. Wearable and Portable GPS Solutions for Monitoring Mobility in Dementia: A Systematic Review. Sensors 2022, 22, 3336. https://doi.org/10.3390/s22093336

Cullen A, Mazhar MKA, Smith MD, Lithander FE, Ó Breasail M, Henderson EJ. Wearable and Portable GPS Solutions for Monitoring Mobility in Dementia: A Systematic Review. Sensors. 2022; 22(9):3336. https://doi.org/10.3390/s22093336

Chicago/Turabian StyleCullen, Anisha, Md Khadimul Anam Mazhar, Matthew D. Smith, Fiona E. Lithander, Mícheál Ó Breasail, and Emily J. Henderson. 2022. "Wearable and Portable GPS Solutions for Monitoring Mobility in Dementia: A Systematic Review" Sensors 22, no. 9: 3336. https://doi.org/10.3390/s22093336

APA StyleCullen, A., Mazhar, M. K. A., Smith, M. D., Lithander, F. E., Ó Breasail, M., & Henderson, E. J. (2022). Wearable and Portable GPS Solutions for Monitoring Mobility in Dementia: A Systematic Review. Sensors, 22(9), 3336. https://doi.org/10.3390/s22093336