Acute Inositol-Stabilized Arginine Silicate Improves Cognitive Outcomes in Healthy Adults

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

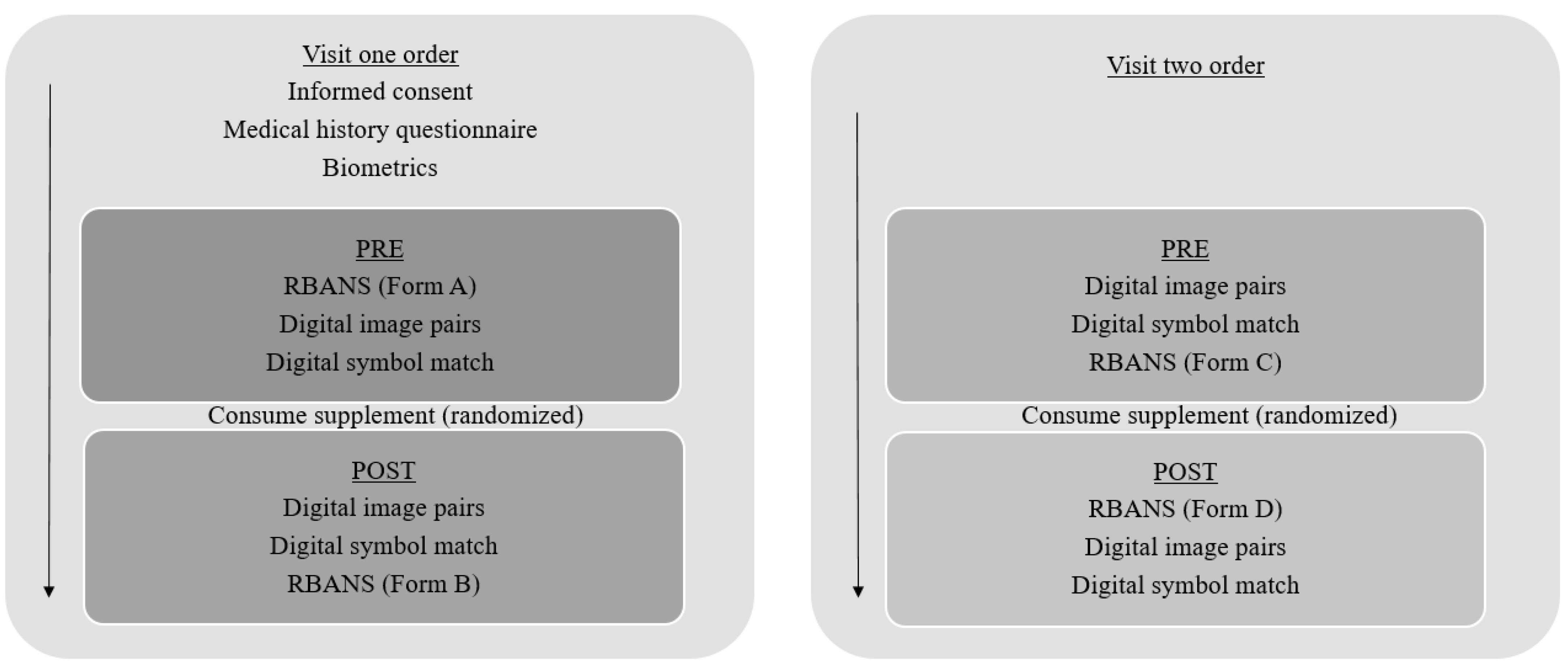

2.2. Procedures

2.3. Biometric Assessments

2.4. Cognitive Assessments

2.4.1. Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS)

2.4.2. Digital Image Pairs

2.4.3. Digital Symbol Match

2.5. Nutritional Data

3. Statistical Analysis

4. Results

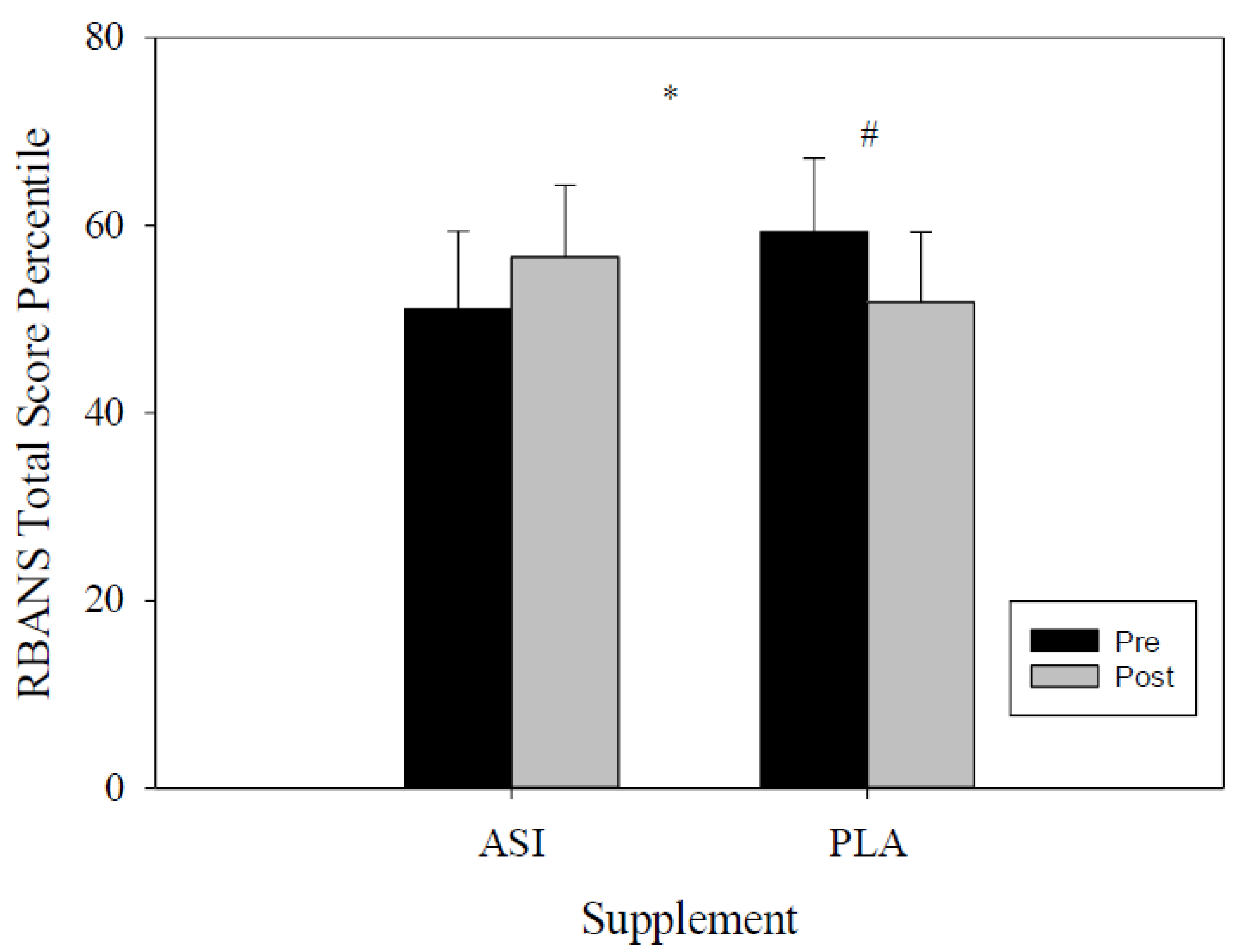

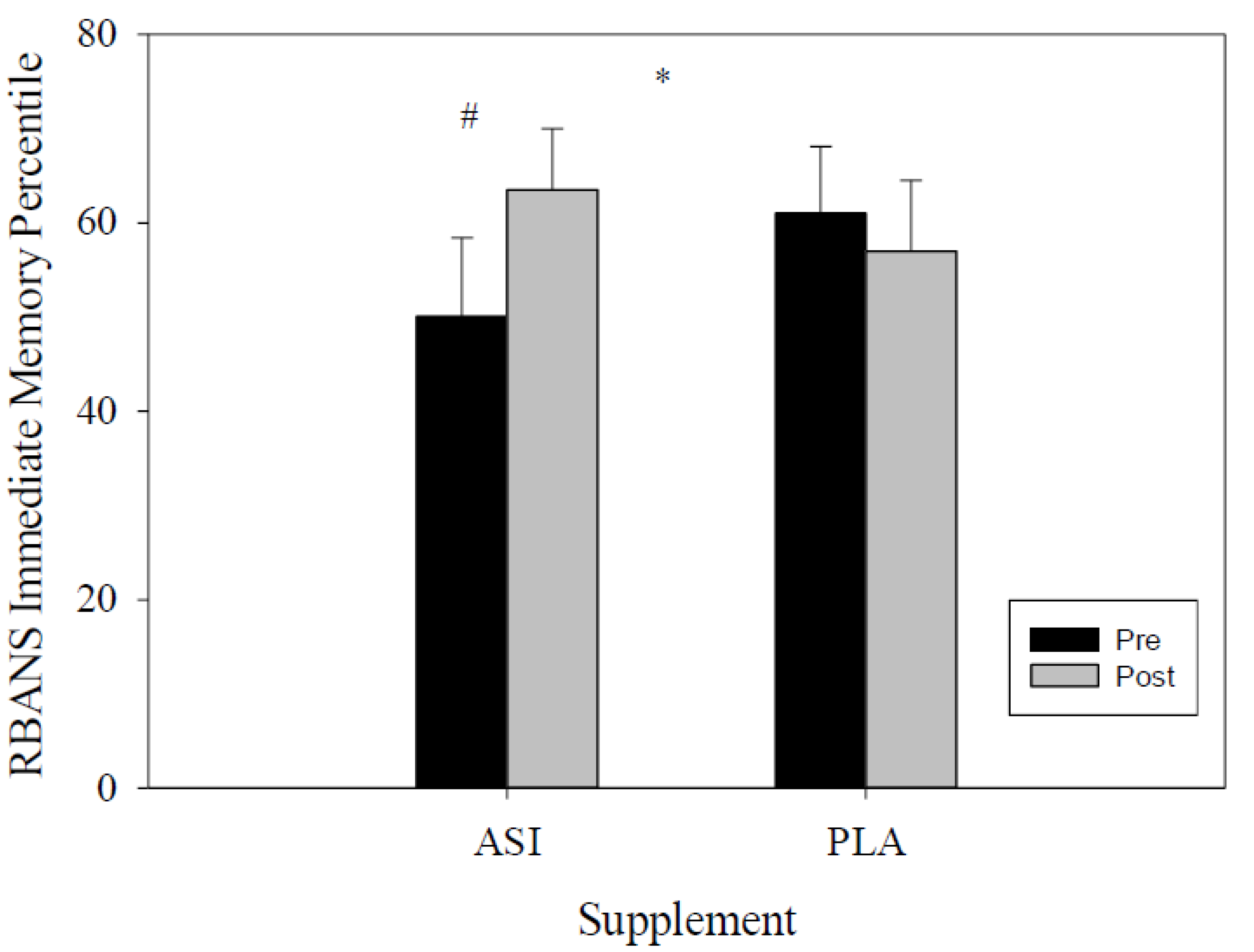

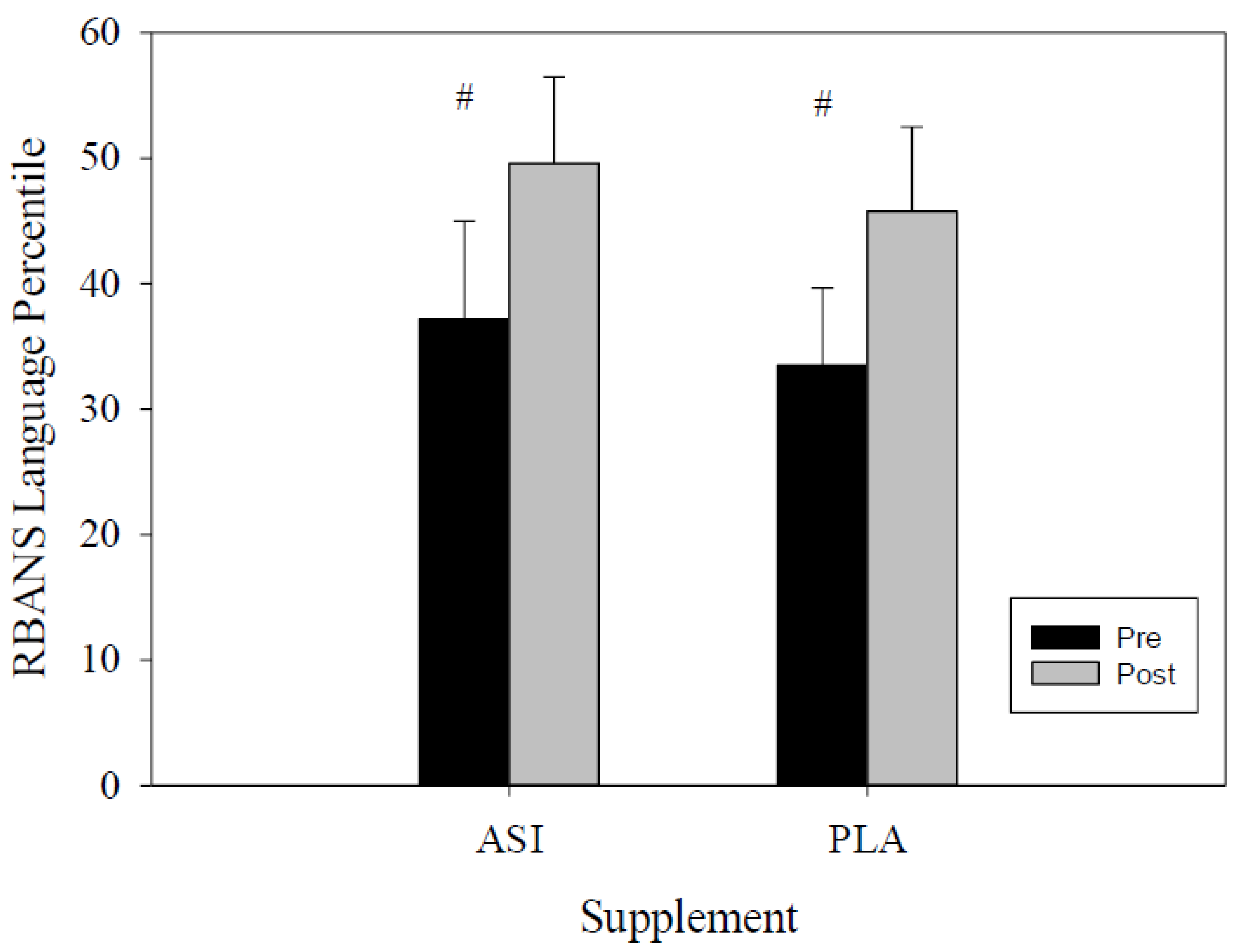

4.1. RBANS

4.2. Digital Image Pairs and Symbol Match

4.3. Nutritional Analysis

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Evans, M.; Zakaria, N.; Marzuk, M.; Ojalvo, S.P.; Sylla, S.; Komorowski, J. An Evaluation of the Effects of Inositol-Stabilized Arginine Silicate (ASI; Nitrosigine®) in Preventing the Decline in Cognitive Function Caused by Strenuous. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Society of Sports Nutrition Conference, Clearwater Beach, FL, USA, 7–9 June 2018; Available online: https://blog.priceplow.com/wp-content/uploads/nitrosigine-preventing-cognitive-decline-caused-by-strenuous-exercise.pdf) (accessed on 20 April 2019).

- Komorowski, J.; Ojalvo, S.P. A Pharmacokinetic Evaluation of the Duration of Effect of Inositol-Stabilized Arginine Silicate and Arginine Hydrochloride in Healthy Adult Males. FASEB J. 2016, 30, 690.17. [Google Scholar]

- Kalman, D.; Harvey, P.D.; Ojalvo, S.P.; Komorowski, J. Randomized Prospective Double-Blind Studies to Evaluate the Cognitive Effects of Inositol-Stabilized Arginine Silicate in Healthy Physically Active Adults. Nutrients 2016, 8, 736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sylla, S.; Ojalvo, S.P.; Komorowski, J. An Evaluation of the Effect of Inositol-Stabilized Arginine Silicate on Heart Rate and Blood Pressure. FASEB J. 2018, 32, 724.12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, S.A.; Santhanam, A.V.; Katusic, Z.S. Endothelial Nitric Oxide Modulates Expression and Processing of Amyloid Precursor Protein. Circ. Res. 2010, 107, 1498–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Talarowska, M.; Gałecki, P.; Maes, M.; Orzechowska, A.; Chamielec, M.; Bartosz, G.; Kowalczyk, E. Nitric oxide plasma concentration associated with cognitive impairment in patients with recurrent depressive disorder. Neurosci. Lett. 2012, 510, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calabrese, V.; Mancuso, C.; Calvani, M.; Rizzarelli, E.; Butterfield, D.A.; Stella, A.M.G. Nitric oxide in the central nervous system: Neuroprotection versus neurotoxicity. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2007, 8, 766–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smriga, M.; Ando, T.; Akutsu, M.; Furukawa, Y.; Miwa, K.; Morinaga, Y. Oral treatment with L-lysine and L-arginine reduces anxiety and basal cortisol levels in healthy humans. Biomed. Res. 2007, 28, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Proctor, S.D.; Kelly, S.E.; Vine, D.F.; Russell, J.C. Metabolic effects of a novel silicate inositol complex of the nitric oxide precursor arginine in the obese insulin-resistant JCR:LA-cp rat. Metabolism 2007, 56, 1318–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jugdaohsingh, R. Silicon and bone health. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2007, 11, 99. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Buffoli, B.; Foglio, E.; Borsani, E.; Exley, C.; Rezzani, R.; Rodella, L.F. Silicic acid in drinking water prevents age-related alterations in the endothelium-dependent vascular relaxation modulating eNOS and AQP1 expression in experimental mice: An immunohistochemical study. Acta Histochem. 2013, 115, 418–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rondeau, V.; Jacqmin-Gadda, H.; Commenges, D.; Helmer, C.; Dartigues, J.-F. Aluminum and Silica in Drinking Water and the Risk of Alzheimer’s Disease or Cognitive Decline: Findings From 15-Year Follow-up of the PAQUID Cohort. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2008, 169, 489–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dickerson, F.; Boronow, J.J.; Stallings, C.; Origoni, A.E.; Cole, S.K.; Yolken, R.H. Cognitive functioning in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: Comparison of performance on the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status. Psychiatry Res. 2004, 129, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobart, M.P.; Goldberg, R.; Bartko, J.J.; Gold, J.M. Repeatable battery for the assessment of neuropsychological status as a screening test in schizophrenia, II: Convergent/discriminant validity and diagnostic group comparisons. Am. J. Psychiatry 1999, 156, 1951–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilk, C.M.; Gold, J.M.; Bartko, J.J.; Dickerson, F.; Fenton, W.S.; Knable, M.; Randolph, C.; Buchanan, R.W. Test-Retest Stability of the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status in Schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry 2002, 159, 838–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bott, N.; Madero, E.N.; Glenn, J.; Lange, A.; Anderson, J.; Newton, D.; Brennan, A.; Buffalo, E.A.; Rentz, D.; Zola, S. Device-Embedded Cameras for Eye Tracking–Based Cognitive Assessment: Validation with Paper-Pencil and Computerized Cognitive Composites. J. Med. Internet Res. 2018, 20, e11143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gills, J.L.; Glenn, J.M.; Madero, E.N.; Bott, N.T.; Gray, M. Validation of a digitally delivered visual paired comparison task: Reliability and convergent validity with established cognitive tests. GeroScience 2019, 41, 441–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gills, J.L.; Bott, N.T.; Madero, E.N.; Glenn, J.M.; Gray, M. A short digital eye-tracking assessment predicts cognitive status among adults. GeroScience 2020, 43, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myers, J.R.; Glenn, J.M.; Madero, E.N.; Anderson, J.; Mak-McCully, R.; Gray, M.; Gills, J.; Harrison, J.E. Rising to the challenge: Asynchronous remote assessment for cognitive impairment. J. Prev. Alzheimer Dis. 2021. Under Review. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, J.M.; Gills, J.; Gray, M. Acute effects of Nitrosigine® and citrulline malate on vasodilation in young adults. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2020, 17, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, K.K.; Atkinson, T.M.; Ryan, J.P. Evidence of practice effects in variants of the Trail Making Test during serial assessment. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 2008, 30, 312–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascalis, O.; De Haan, M.; Nelson, C.A.; De Schonen, S. Long-term recognition memory for faces assessed by visual paired comparison in 3-and 6-month-old infants. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 1998, 24, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Supplement | Pre | Post | Lower CI | Upper CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Score Index | ASI | 102.7 ± 4.8 | 105.5 ± 4.6 | −6.67 | 1.14 | 0.017 * |

| PLA | 104.9 ± 3.8 | 100.9 ± 3.5 | −0.10 | 8.22 | ||

| Total Score Percentile | ASI | 51.1 ± 8.3 | 56.6 ± 7.6 | −13.71 | 2.70 | 0.024 * |

| PLA | 59.3 ± 7.9 | 51.8 ± 7.5 | 0.35 | 14.65 | ||

| Immediate Memory Index | ASI | 101.8 ± 4.7 | 107.2 ± 3.7 | −11.44 | 0.61 | 0.108 |

| PLA | 105.8 ± 4.1 | 103.5 ± 3.9 | −4.69 | 9.16 | ||

| Immediate Memory Percentile | ASI | 50.1 ± 8.3 | 63.5 ± 6.5 | −23.45 | −3.4 | 0.047 * |

| PLA | 59.3 ± 7.9 | 51.8 ± 7.5 | −8.04 | 15.9 | ||

| Visuospatial/Constructional Index | ASI | 107.5 ± 3.1 | 106.3 ± 4.1 | −4.79 | 7.15 | 0.270 |

| PLA | 110.9 ± 4.3 | 105.0 ± 3.6 | 0.98 | 10.79 | ||

| Visuospatial/Constructional Percentile | ASI | 63.9 ± 6.3 | 61.9 ± 8.1 | −10.39 | 14.52 | 0.186 |

| PLA | 75.4 ± 7.4 | 61.2 ± 6.7 | 5.15 | 23.32 | ||

| Language Index | ASI | 90.2 ± 4.9 | 99.6 ± 3.2 | −15.71 | −3.12 | 0.689 |

| PLA | 90.1 ± 3.8 | 98.2 ± 3.1 | −15.88 | −0.24 | ||

| Language Percentile | ASI | 37.2 ± 7.8 | 49.6 ± 6.9 | −23.14 | −1.69 | 0.148 |

| PLA | 33.5 ± 6.2 | 45.8 ± 6.7 | −26.24 | 1.58 | ||

| Attention Index | ASI | 109.1 ± 4.1 | 110.5 ± 5.2 | −8.59 | 5.89 | 0.521 |

| PLA | 109.0 ± 3.7 | 107.8 ± 3.6 | −3.13 | 5.60 | ||

| Attention Percentile | ASI | 63.4 ± 6.9 | 63.4 ± 7.7 | −11.29 | 11.19 | 0.960 |

| PLA | 66.6 ± 6.7 | 66.6 ± 7.5 | −7.11 | 6.96 | ||

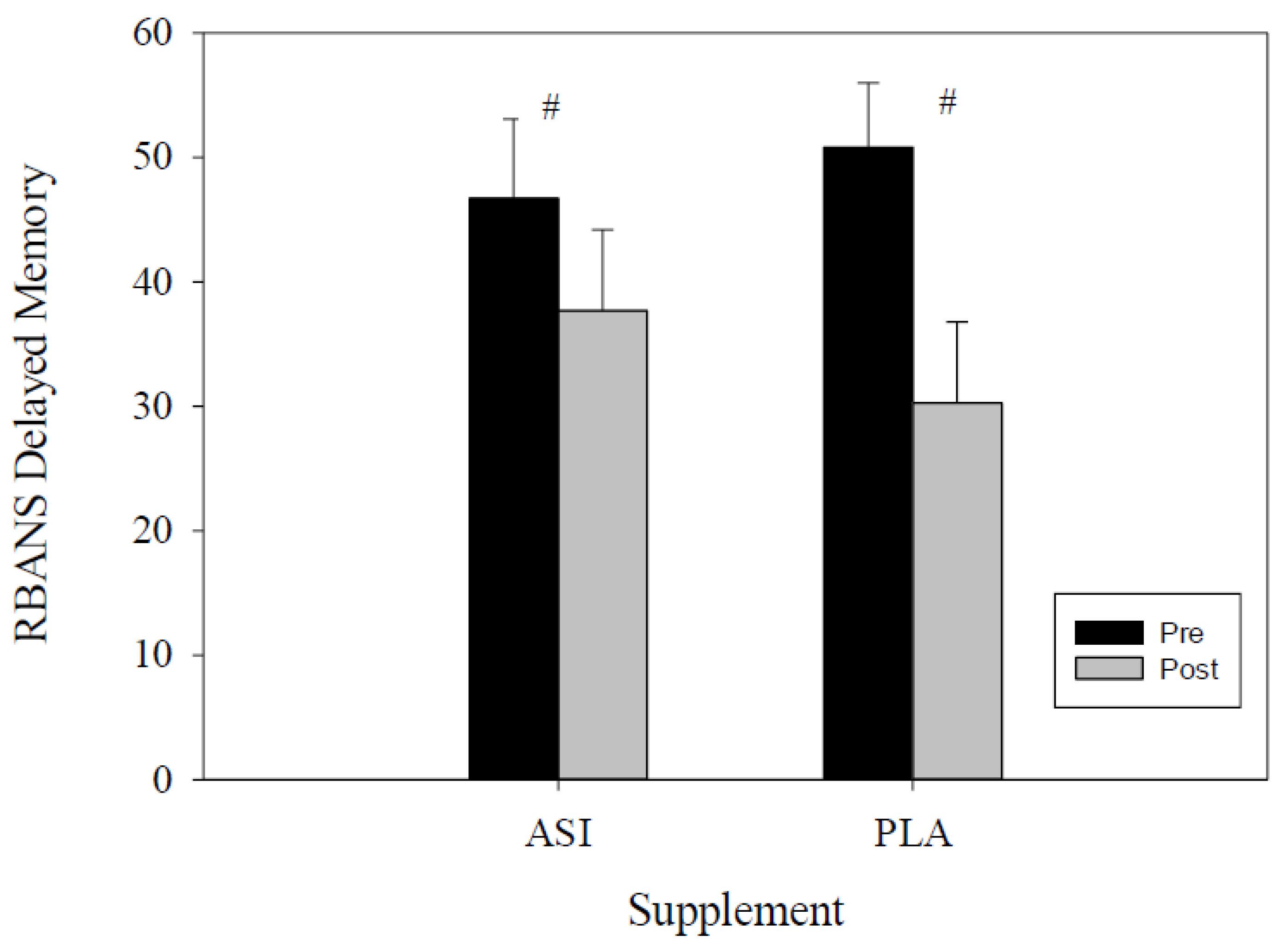

| Delayed Memory Index | ASI | 98.8 ± 3.1 | 92.8 ± 3.5 | 0.42 | 11.70 | 0.272 |

| PLA | 100.4 ± 2.3 | 89.4 ± 3.6 | 4.32 | 17.55 | ||

| Delayed Memory Percentile | ASI | 46.7 ± 6.4 | 37.7 ± 6.5 | −1.23 | 19.11 | 0.157 |

| PLA | 50.8 ± 5.2 | 30.3 ± 6.5 | 8.43 | 32.57 |

| Variable | Supplement | Pre | Post | Lower CI | Upper CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| List Learning (IM) | ASI | 29.9 ± 1.2 | 31.7 ± 1.1 | −4.41 | 0.81 | 0.169 |

| PLA | 31.7 ± 1.0 | 30.6 ± 0.9 | −1.06 | 3.18 | ||

| Story Memory (IM) | ASI | 18.5 ± 1.0 | 19.7 ± 0.9 | −2.99 | 0.73 | 0.476 |

| PLA | 19.4 ± 1.0 | 19.4 ± 1.0 | −1.59 | 1.38 | ||

| Figure Copy (VSC) | ASI | 19.7 ± 0.2 | 19.6 ± 0.3 | −0.32 | 0.46 | 0.308 |

| PLA | 19.4 ± 1.0 | 19.4 ± 0.7 | −0.13 | 0.83 | ||

| Line Orientation (VSC) | ASI | 17.5 ± 1.0 | 16.6 ± 1.1 | −0.68 | 2.42 | 0.741 |

| PLA | 18.3 ± 0.6 | 17.6 ± 0.7 | −0.24 | 1.65 | ||

| Semantic Fluency (Language) | ASI | 17.7 ± 1.3 | 18.1 ± 1.22 | −2.76 | 1.88 | 0.599 |

| PLA | 17.3 ± 1.3 | 18.7 ± 0.95 | −4.42 | 1.53 | ||

| Picture Naming (Language) | ASI | 9.5 ± 0.5 | 10.5 ± 0.5 | −2.54 | 0.54 | 0.236 |

| PLA | 8.8 ± 0.3 | 9.8 ± 0.1 | −1.48 | −0.52 | ||

| Coding (Attention) | ASI | 61.9 ± 2.5 | 63.3 ± 3.0 | −5.24 | 2.49 | 0.176 |

| PLA | 63.5 ± 2.5 | 61.2 ± 1.9 | −1.25 | −5.84 | ||

| Digit Span (Attention) | ASI | 12.2 ± 0.6 | 12.3 ± 0.72 | −1.55 | 1.43 | 0.578 |

| PLA | 11.7 ± 0.4 | 12.4 ± 0.5 | −1.81 | 0.25 | ||

| List Recall (DM) | ASI | 7.3 ± 0.5 | 5.7 ± 0.8 | 0.46 | 2.79 | 0.438 |

| PLA | 7.8 ± 0.4 | 6.9 ± 0.8 | −0.86 | 2.64 | ||

| Story Recall (DM) | ASI | 11.1 ± 0.6 | 10.9 ± 0.2 | −11.29 | 11.19 | 0.347 |

| PLA | 10.2 ± 0.4 | 10.3 ± 0.4 | −1.23 | 1.73 | ||

| Figure Recall (DM) | ASI | 18.3 ± 3.1 | 18.8 ± 0.3 | −1.54 | 0.66 | 0.337 |

| PLA | 17.8 ± 0.6 | 18.0 ± 0.5 | −1.50 | 1.00 | ||

| List Recognition (DM) | ASI | 19.6 ± 0.2 | 18.5 ± 0.5 | 0.03 | 2.22 | 0.560 |

| PLA | 19.8 ± 0.1 | 18.8 ± 0.3 | 0.44 | 1.67 | ||

| Image Pair (Digital) | ASI | 0.86 ± 0.04 | 0.91 ± 0.03 | −0.09 | 0.01 | 0.480 |

| PLA | 0.87 ± 0.04 | 0.93 ± 0.02 | −0.10 | −0.02 | ||

| Symbol Digit Match (Digital) | ASI | 0.86 ± 0.04 | 0.92 ± 0.04 | −0.14 | 0.03 | 0.546 |

| PLA | 0.91 ± 0.04 | 0.92 ± 0.05 | −0.09 | 0.07 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gills, J.L.; Campitelli, A.; Jones, M.; Paulson, S.; Myers, J.R.; Madero, E.N.; Glenn, J.M.; Komorowski, J.; Gray, M. Acute Inositol-Stabilized Arginine Silicate Improves Cognitive Outcomes in Healthy Adults. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4272. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13124272

Gills JL, Campitelli A, Jones M, Paulson S, Myers JR, Madero EN, Glenn JM, Komorowski J, Gray M. Acute Inositol-Stabilized Arginine Silicate Improves Cognitive Outcomes in Healthy Adults. Nutrients. 2021; 13(12):4272. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13124272

Chicago/Turabian StyleGills, Joshua L., Anthony Campitelli, Megan Jones, Sally Paulson, Jennifer Rae Myers, Erica N. Madero, Jordan M. Glenn, James Komorowski, and Michelle Gray. 2021. "Acute Inositol-Stabilized Arginine Silicate Improves Cognitive Outcomes in Healthy Adults" Nutrients 13, no. 12: 4272. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13124272