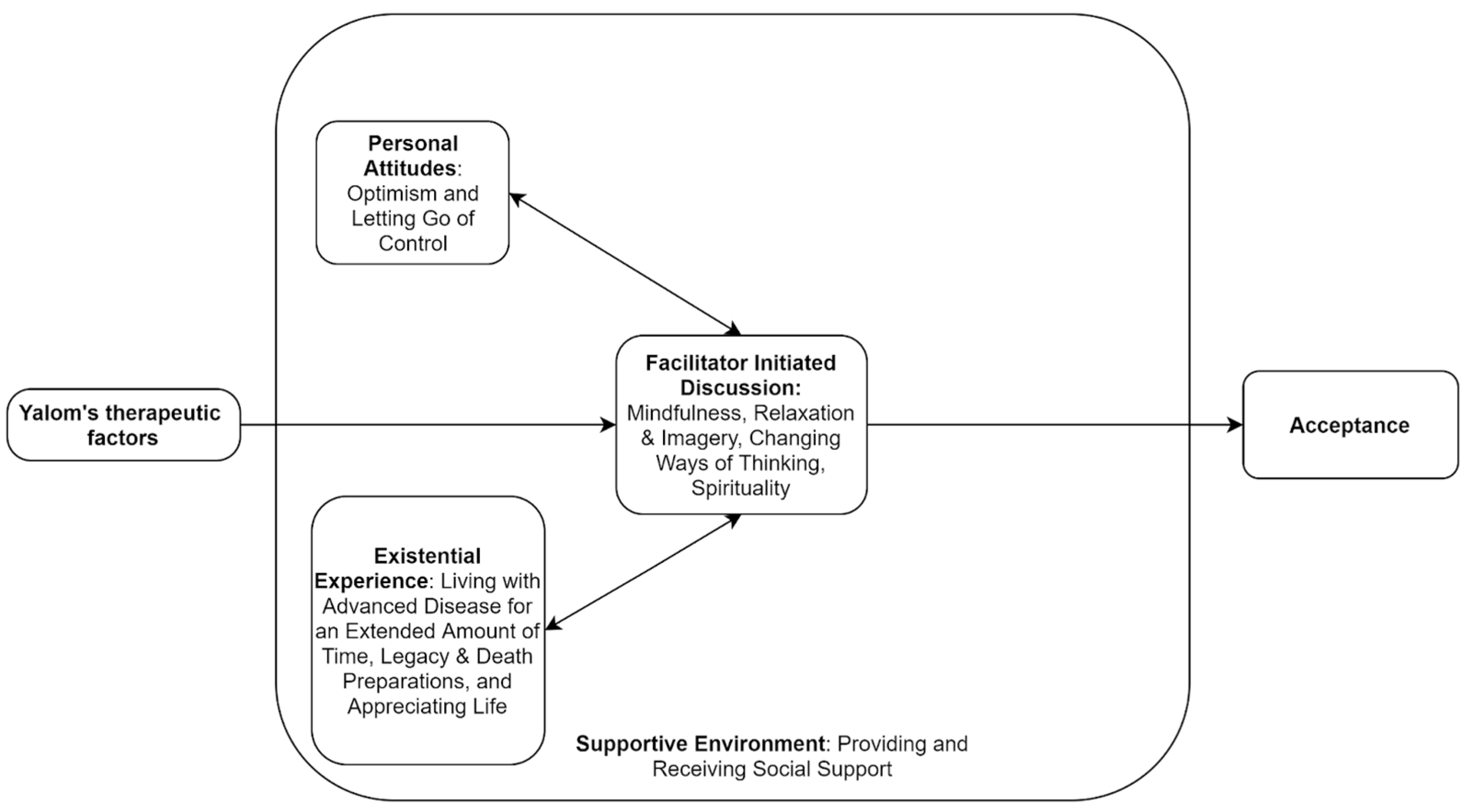

Pathways to Acceptance in Participants of Advanced Cancer Online Support Groups

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Objectives

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Data Analysis

2.3. Directed Content Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Theme 1: “Facilitator-Initiated Discussion”

3.1.1. Sub-Theme 1: Mindfulness

3.1.2. Sub-Theme 2: Relaxation and Imagery

3.1.3. Sub-Theme 3: Changing Ways of Thinking

3.1.4. Sub-Theme 4: Spirituality

3.2. Theme 2: “Personal Attitudes”

3.2.1. Sub-Theme 1: Optimism

3.2.2. Sub-Theme 2: Letting Go of Control

3.3. Theme 3: “Supportive Environment”

3.3.1. Sub-Theme 1: Providing Support for Others

3.3.2. Sub-Theme 2: Receiving Support from Others

3.4. Theme 4: “Existential Experience”

3.4.1. Sub-Theme 1: Living with Diagnosis for an Extended Amount of Time

3.4.2. Sub-Theme 2: Legacy and Death Preparations

3.4.3. Sub-Theme 3: Appreciating Life

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Acceptance Coding Guide

- “Acceptance of cancer, or making peace with the disease, is one factor that may play an important role in reducing patients’ distress” [3].

- “Acceptance of illness was defined as a process of a value change by which the patient accepts the losses related to the illness while maintaining a sense of self-worth” [6].

- “Willingness to be present with one’s illness-related thoughts, feelings, and bodily sensations without judging or making unnecessary attempts to control them” [5].

- “An accepting patient does not judge, avoid, or deny the illness but continues feasible engagement in everyday activities” [33].

- Acceptance differs from resignation (i.e., fatalism) [3]. Acceptance does not necessarily include efforts of positive reframing or aiming to change the course of the disease.

- “Expression of emotional willingness: an active approach of making room for difficult feelings, memories, and physical sensations in order to pursue a valued goal” [34].

- “Acceptance involves the active and aware embrace of experience without unnecessary attempts to change their form” [19].

- “To be aware of thoughts and feelings but not to change, avoid, or otherwise control them” [35].

- “It involves a conscious decision to abandon one’s agenda to have a different experience and an active process of ‘allowing’ current thoughts, feelings, and sensations” [36].

- “It is an active process in that the client chooses to take what is offered with an attitude of openness and receptivity to whatever happens to occur in the field of awareness” [18].

| Acceptance Examples | Justification and Reasoning |

|---|---|

| “Go with the flow” | It sounds like they are accepting, and the phrase “go with the flow” is usually used in a more relaxed context as opposed to the phrase “it is what it is”, which might be said with more of a negative undertone. |

| “Count my blessings” | This is accepting that you have to take the good with the bad, and they are choosing to focus on the good. |

| “life is good” | |

| “I’m making the most of my time left being happy and filled with [joy]” | This makes it sound like they are aware that death may be approaching, but they have chosen to accept that and enjoy what they have left. |

| “It just made me glad I have the ability to enjoy what I have left, death comes to all in time” | Using the word “glad” to express how they feel about the time they have left gave the sense that they are accepting that death is coming but are not dwelling on it. Also, when they say “death comes to all”, again, they are accepting that everyone eventually dies, and their time is coming. |

| “it is what you do to live without fear that brings [joy]” | It sounds like they acknowledge the idea that death is coming and are at peace with it, hence “live without fear”. |

| Any positive talk about death Ex. “Death is going to be a new adventure”; “I will face it with my spiritual culture” | To talk positively about death sounds like they have come to terms with/accepted the situation and have let go of their negative feelings about it. |

| “just have to keep going” or “keep moving forward’ | Despite the situation they are in, it sounds like they are accepting what is happening and continuing on with their life. They are not letting negative feelings/experiences allow them to give up. |

| “I think anger is healthy and part of the process” | This fits really well with the textbook definition of acceptance; they are recognizing that negative emotions come with their experience but do not dwell on them/punish themselves for having these feelings. |

| “Roll with the punches” | |

| “It gets easier after a while” or “It gets better with time” | This sounds like they have been going through this for a while and are now starting to accept the situation. |

| “I think grief is part of the illness. I ****** for the person I was before cancer. I can’t go back to being that person ever again” | I think any acknowledgement that a negative emotion is part of the process is acceptance. Also, they have come to terms that they are not the same person they were before. |

| “it’s just a new me ****. I will adjust” |

| Fatalism Examples | Justification and Reasoning |

|---|---|

| “sometimes it makes me depressed but that’s just normal for me” | Although they are acknowledging that this experience of these negative emotions is normal, it could still be considered distress. Talking about how “normal” a negative experience is does not necessarily mean that they are coping well with this truth. |

| “It doesn’t really matter” | It sounds like they are not worried about trying to change the situation but not because they are accepting it; it is more like they have given up. |

| “It is what it is” | This sounds very much like giving up. |

| “I’m going to die anyway” | Sounds like they are hopeless just because death is coming; they have stopped caring about what they are going through. They are not trying to change their situation, which is similar to acceptance; however, they are still in a great deal of distress. |

References

- Krzyszczyk, P.; Acevedo, A.; Davidoff, E.J.; Timmins, L.M.; Marrero-Berrios, I.; Patel, M.; White, C.; Lowe, C.; Sherba, J.J.; Hartmanshenn, C.; et al. The Growing Role of Precision and Personalized Medicine for Cancer Treatment. Technology 2018, 6, 79–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kirkova, J.; Walsh, D.; Rybicki, L.; Davis, M.P.; Aktas, A.; Jin, T.; Homsi, J. Symptom Severity and Distress in Advanced Cancer. Palliat. Med. 2010, 24, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secinti, E.; Tometich, D.B.; Johns, S.A.; Mosher, C.E. The Relationship between Acceptance of Cancer and Distress: A Meta-Analytic Review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2019, 71, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.C.; Lynn, S.J. Acceptance: An Historical and Conceptual Review. Imagin. Cogn. Personal. 2010, 30, 5–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S.C.; Jacobson, N.S.; Follette, V.M.; Dougher, M.J. Acceptance and Change: Content and Context in Psychotherapy; Context Press: Reno, NV, USA, 1994; p. 272. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, B.A. Physical Disability: A Psychosocial Approach, 2nd ed.; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Livneh, H. Psychosocial Adaptation to Cancer: The Role of Coping Strategies. J. Rehabil. 2000, 66, 40–49. [Google Scholar]

- Ray, A.; Block, S.D.; Friedlander, R.J.; Zhang, B.; Maciejewski, P.K.; Prigerson, H.G. Peaceful Awareness in Patients with Advanced Cancer. J. Palliat. Med. 2006, 9, 1359–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philipp, R.; Mehnert, A.; Lo, C.; Müller, V.; Reck, M.; Vehling, S. Characterizing Death Acceptance among Patients with Cancer. Psychooncology 2019, 28, 854–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upasen, R.; Thanasilp, S. Death Acceptance among Patients with Terminal Cancer. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2018, 56, e71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tang, S.T.; Chang, W.-C.; Chen, J.-S.; Chou, W.-C.; Hsieh, C.-H.; Chen, C.H. Associations of Prognostic Awareness/Acceptance with Psychological Distress, Existential Suffering, and Quality of Life in Terminally Ill Cancer Patients’ Last Year of Life. Psychooncology 2016, 25, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torous, J.; Myrick, K.J.; Rauseo-Ricupero, N.; Firth, J. Digital Mental Health and COVID-19: Using Technology Today to Accelerate the Curve on Access and Quality Tomorrow. JMIR Ment. Health 2020, 7, e18848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephen, J.; Rojubally, A.; MacGregor, K.; McLeod, D.; Speca, M.; Taylor-Brown, J.; Fergus, K.; Collie, K.; Turner, J.; Sellick, S.; et al. Evaluation of CancerChatCanada: A Program of Online Support for Canadians Affected by Cancer. Curr. Oncol. 2013, 20, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yalom, I.D. The Theory and Practice of Group Psychotherapy, 5th ed.; Basic Books/Hachette Book Group: New York, NY, USA, 2005; ISBN 978-0-465-09284-0. [Google Scholar]

- de Souza Institute Support Center Nucare Manual-Mixed Diagnosis. Available online: https://support.desouzainstitute.com/kb/article/54-nucare-manual (accessed on 27 June 2021).

- Hsieh, H.-F.; Shannon, S.E. Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Wildemuth, B.M. Qualitative Analysis of Content. In Applications of Social Research Methods to Questions in Information and Library Science; Libraries Unlimited: Westport, CT, USA, 2009; pp. 308–319. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, S.R.; Lau, M.; Shapiro, S.; Carlson, L.; Anderson, N.D.; Carmody, J.; Segal, Z.V.; Abbey, S.; Speca, M.; Velting, D.; et al. Mindfulness: A Proposed Operational Definition. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2004, 11, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S.C.; Luoma, J.B.; Bond, F.W.; Masuda, A.; Lillis, J. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: Model, Processes and Outcomes. Behav. Res. Ther. 2006, 44, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Leung, Y.W.; Wouterloot, E.; Adikari, A.; Hirst, G.; De Silva, D.; Wong, J.; Bender, J.L.; Gancarz, M.; Gratzer, D.; Alahakoon, D.; et al. Natural Language Processing–Based Virtual Cofacilitator for Online Cancer Support Groups: Protocol for an Algorithm Development and Validation Study. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2021, 10, e21453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clay, L.; Hay-Smith, E.J.C.; Treharne, G.J.; Milosavljevic, S. Unrealistic Optimism, Fatalism, and Risk-Taking in New Zealand Farmers’ Descriptions of Quad-Bike Incidents: A Directed Qualitative Content Analysis. J. Agromed. 2015, 20, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. Mindfulness. Mindfulness 2015, 6, 1481–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, P.T.P.; Tomer, A. Beyond Terror and Denial: The Positive Psychology of Death Acceptance. Death Stud. 2011, 35, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.; Staps, T.; Hijmans, E. Existential Crisis and the Awareness of Dying: The Role of Meaning and Spirituality. OMEGA-J. Death Dying 2010, 61, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmody, J.; Reed, G.; Kristeller, J.; Merriam, P. Mindfulness, Spirituality, and Health-Related Symptoms. J. Psychosom. Res. 2008, 64, 393–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, M.; Chebiyyam, S. Posttraumatic Growth: Positive Changes Following Adversity—An Overview. Int. J. Psychol. Behav. Sci. 2006, 6, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RELIGIONI, U.; CZERW, A.; DEPTAŁA, A. Acceptance of Cancer in Patients Diagnosed with Lung, Breast, Colorectal and Prostate Carcinoma. Iran. J. Public Health 2015, 44, 1135–1142. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Chapter 6—Brief Humanistic and Existential Therapies; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US): Rockville, MD, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel, D.; Butler, L.D.; Giese-Davis, J.; Koopman, C.; Miller, E.; DiMiceli, S.; Classen, C.C.; Fobair, P.; Carlson, R.W.; Kraemer, H.C. Effects of Supportive-Expressive Group Therapy on Survival of Patients with Metastatic Breast Cancer. Cancer 2007, 110, 1130–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, R.W.L.; Cheng, S.-T. Gratitude Lessens Death Anxiety. Eur. J. Ageing 2011, 8, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Daher, M. Cultural Beliefs and Values in Cancer Patients. Ann. Oncol. 2012, 23, iii66–iii69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kübler-Ross, E. On Death and Dying; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1970; ISBN 978-0-02-089130-7. [Google Scholar]

- McCracken, L.M.; Eccleston, C. Coping or Acceptance: What to Do about Chronic Pain? Pain 2003, 105, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesser, H.; Westin, V.; Hayes, S.C.; Andersson, G. Clients’ in-Session Acceptance and Cognitive Defusion Behaviors in Acceptance-Based Treatment of Tinnitus Distress. Behav. Res. Ther. 2009, 47, 523–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keogh, E.; Bond, F.W.; Hanmer, R.; Tilston, J. Comparing Acceptance- and Control-Based Coping Instructions on the Cold-Pressor Pain Experiences of Healthy Men and Women. Eur. J. Pain 2005, 9, 591–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, S.C.; Strosahl, K.D.; Wilson, K.G. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: An Experiential Approach to Behavior Change; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999; p. xvi, 304. ISBN 978-1-57230-481-9. [Google Scholar]

| Characteristics | Value (n = 18), n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 17 (94.44) |

| Male | 1 (5.55) |

| Unknown | 0 (0) |

| Age group (years) | |

| 18–24 | 0 (0) |

| 25–34 | 1 (5.55) |

| 35–44 | 4 (22.22) |

| 45–54 | 2 (11.11) |

| 55–64 | 10 (55.55) |

| 65+ | 1 (5.55) |

| Location | |

| British Columbia | 6 (33.33) |

| Ontario | 7 (38.88) |

| Alberta | 2 (11.11) |

| Other province | 3 (16.66) |

| Type of cancer | |

| Breast | 11 (61.11) |

| Gynecological | 0 (0) |

| Colorectal | 4 (22.22) |

| Head and neck | 1 (5.55) |

| Other cancers | 1(5.55) |

| Unknown | 1 (5.55) |

| Treatment status | |

| Active treatment | 0 (0) |

| Post treatment | 0 (0) |

| Other | 18 (100) |

| Themes | Sub-Themes | Quotes from the Patients (Session, Participant ID Number, Sex, Age) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Facilitator-initiated discussion | Mindfulness | “I try to be mindful daily. It can be hard but I just really try to enjoy each moment and savour it. I’m so happy to be alive. I read some of the coping skills, and I like the saying ‘the present moment is the only time that any of us ever has’” (Advanced_Cancer_Session1_30 April 2021; User ID: 3100, female, 35–44) | “I have always been optimistic-not (sic) everyone is. I purposely find the good in people and in life. We really don’t have to look too far in our everyday lives to find that we are in fact very lucky to be living here in Canada.” (Advanced_Cancer_Sesson1_30 April 2021; User ID: 3212, female, 55–64) | “I think going through diagnosis, treatment etc (sic) taught me to let go of control/planning.” (Advanced_Cancer_Session1_30 April 2021; User ID: 3034, female, 55–64) | ||||||

| Relaxation and Imagery | “While I’m aware of my limitations, the power of the mind and being able to take ourselves away from our currently reality can make a difference-for (sic) me, anyway. Even for a brief amount of time. Can help a bit with the boredom too. lol.” (Advanced_Cancer_Session2_7 May 2021; User ID: 2338, female, 35–44) | “Mostly that my feelings are shared by others. I am not alone or isolated in my feelings. This disease sucks. Bad. We need to give ourselves moments of self calm. Even briefly.” (Advanced_Cancer_Session2_7 May 2021; User ID: 3197, male, 45–54) | ||||||||

| Ways of thinking (grief and loss, changing their cancer thoughts, | “I try to Live in the moment and appreciate the little things instead of wallowing in grief.” (Advanced_Cancer_Session3_14 May 2021; User ID: 3208, female, 35–44) | “The rewards of staying in the moment and recognizing and changing negative self talk are so stress reducing.” (Advanced_Cancer_Session3_14 May 2021; User ID: 3034, female, 55–64) | “I accept it right away. I have never been angry or asked why me. Why not me! Better that I have it and not my mom or sister. Then, i am thankful that there are treatments for me, and I just carry on. It is my new normal, and I am still thankful.” (Advanced_Cancer_Session3_14 May 2021; User ID: 3212, female, 55–64) | |||||||

| Spirituality (religious, non-religious, and death) | “Faith is important to me. And it helps me” (Advanced_Cancer_Session7_11 June 2021; User ID: 3212, female, 55–64) | “***** I cope with it by going outside and enjoying nature. Spending as much time with my kids as well.” (Advanced_Cancer_Sesson1_30 April 2021; User ID: 3100, female, 35–44) | “Actually laughter and spirituality can be linked […] Not taking yourself so seriously, enjoying life, living in the moment.” (Advanced_Cancer_Session7_11 June 2021; User ID: 3203, female, 55–64) | “We are [a death-denying society], but [death] does not scare me at all […] I have had a near-death experience so I have no fear left […] No fear at all actually. It was one of the most profound moments of my life.” (Advanced_Cancer_Session7_11 June 2021; User ID: 3203, female, 55–64) | “i have a good relationship with death” (Advanced_Cancer_Session7_11 June 2021; User ID: 3203, female, 55–64) | “Death does not bother me a lot.” (Advanced_Cancer_Ssession7_11 June 2021; User ID: 2987, female 65+) | ||||

| Personal attitudes | Optimism | “We all have choices ****. Most day (sic) I choose to find the good. Everyday I find something good. Start with simple things. Focus on others and not me.” (Advanced_Cancer_Session3_14 May 2021; User ID: 3212, female, 55–64) | “** I was also scared about the word “Palliative” and the added team on my already overwhelming list. But I have quickly realized that palliative can also be years and years of continued life.” (Advanced_Cancer_Session1_30 April 2021; User ID: 3215, female, 25–34) | “This is our new normal, unfortunately. But it does not have to be all bad and negative. I find positivity every day. I have to. It really helps me.” (Advanced_Cancer_Session1_30 April 2021; User ID: 3212, female, 55–64) | ||||||

| Letting Go of Control | “Me tooI (sic) was always planning and controlling things but now I Have totally let go.” (Advanced_Cancer_Sesson1_30 April 2021; User ID: 3100, female, 35–44) | “I have a 15 year old daughter with autism. I stay positive for her. I also take one day at a time now. Which was hard as I was a chronic “planner” person. lol. But taking things step by step now keeps me more positive as well as reaching out to others.” (Advanced_Cancer_Sesson1_30 April 2021; User ID: 2338, female, 35–44) | “i always try to push through and be the hero… that I can do this… and i do love my kitchen, cooking etc… but I bit the bullet and wow… I feel so free knowing its (sic) one less thing I have to worry about.” (Advanced_Cancer_Session5_28 May 2021; User ID: 3215, female, 25–34) | “I find that my lists allow me to keep track of things and I feel less stressed as I often forget things.” (Advanced_Cancer_Session5_15 July 2020; User ID: 2557, female, 55–64) | ||||||

| Supportive environment | Receiving Support from Others | “Thanks! I wish that everyone finds some peace and hope to enjoy each days (sic) as it comes…, Thanks everyone!.,Ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha.,Feeling very supported!” (Advanced_Cancer_Session7_29 July 2020; User ID: 2417, female, 55–64) | “Feeling very supported!.,Bye everybody! Have a good week!”(Advanced_Cancer_Session6_22 July 2020; User ID: 2417, female, 55–64) | “MoStly that my feelings are shared by others. I am not alone or isolated in my feelings. This disease sucks. Bad. We need to give ourselves moments of self calm. Even briefly.” (Advanced_Cancer_Session2_7 May 2021; User ID: 3197, male, 45–54) | “***** - I cope with it by going outside and enjoying nature. Spending as much time with my kids as well.” (Advanced_Cancer_Sesson1_30 April 2021; User ID: 3100, female, 35–44) | “I have great support from my immediate family and friends.” (Advanced_Cancer_Session5_28 May 2021; User ID: 3215, female, 25–34) | “Yes I am surrounded by love and support. That’s one reason that I can help support others.” (Advanced_Cancer_Session8_18 June 2021; User ID: 3212, female, 55–64) | “I find talking to my close friends and sister very helpful to ease the thoughts… chocolate yes!” (Advanced_Cancer_Session3_24 June 2020; User ID: 2557, female, 55–64) | “I really appreciate being in this group. As I read all of your stories I feel less alone.” (Advanced_CancerSession1_30 April 2021; User ID: 2338, female, 35–44) | “Scary though[t] but we are in it together.” (Advanced_Cancer_Session1_30 April 2021; User ID: 3197, male, 45–54) |

| Providing Support to Others | “*****- it has been somewhat helpful for me to look in to some supports around death. It may be very early but it helps to feel like I have my ducks in a row. I’ve looked into Greensleeves, MAID etc.” (Advanced_Cancer _Session7_11 June 2021; User ID: 3034, female, 55–64) | “******- that is totally fair and everyone’s risk level is different. You may change in the future and not now so that is okay.” (Advanced_Cancer_Session3_ 19 Aug 2020; User ID: 2799, unknown, unknown) | “Unfortunately I know a lot of people in the cancer world, friends and two sisters, so many around me can relate and support. I tend to help support others who are going through non cancer problems… pain is pain.”(Advanced_Cancer_Session6_22 July 2020; User ID: 2877, female, 45–54) | “I always find comfort in supporting others who are going through the same thing.” (Advanced_Cancer_Session4_21 May 2021; User ID: 3215, female, 25–34) | ||||||

| Existential Experiences | Living with Diagnosis for an Extended Amount of Time | “Three years stable and feeling blessed.” (Advance_Cancer_Session1_5 Aug 2020; User ID: 2877, female, 45–54) | “I never got angry when first diagnosed 11 years ago. I am still not angry as it won’t do me any good. This is what I have been dealt with and so this is what I have to do. And i would rather have this than my mom or sister. I can do this, and I am.” (Advanced_Cancer_Session1_30 April 2021; User ID: 3212, female, 55–64) | |||||||

| Legacy and Death Preparations | “I have taken over someone else’s legacy and am adding to it and then will pass it on to the next person when the time comes.” (Advanced_Cancer_Session6_4 June 2021; User ID: 3203, female,55–64) | “I’d like to leave behind something that may help others in similar situations. Yes, I am also beginning a big purge project and try to reorganize my stuff.” (Advanced_Cancer_Session6_4 June 2021; User ID: 2987, female 65+) | “I have started an EOL plan… it’s hard but needs to be done.” (Advanced_Cancer_Session4_21 May 2021; User ID: 3215, female, 25–34) | |||||||

| Appreciating Life | “I am thankful that I am still here enjoying life. I just had another friend lose her battle on wednesday and it makes me appreciate life so much!” (Advanced_Cancer_Session3_14 May 2021; User ID: 3203, female, 55–64) | “I can’t work anymore, so I’m trying to see myself as retired, but with some health problems.” “Advanced _Cancer_Session2_12 August 2020; User ID: 2417, female, 55–64) | “Will always be in treatment but thankful and happy to be here. Side effects and all.” (Advanced_Cancer_Session1_30 April 2021; User ID: 3212, female,55–64) | “as I can’t change the past - I’ve worked hard at releasing the negative energy that it brings.that’s (sic) true Sue—I enjoy ‘everyday\\” and think of it as a [gift].” (Advanced_Cancer_Session7_16 September 2020; User ID: 2557, female, 55–64) | “[Cancer] has definitely allowed me to experience life more fully.” (Advanced_Cancer_Session7_11 June 2021; User ID: 3203, female, 55–64) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pereira, C.F.; Cheung, K.; Alie, E.; Wong, J.; Esplen, M.J.; Leung, Y.W. Pathways to Acceptance in Participants of Advanced Cancer Online Support Groups. Medicina 2021, 57, 1168. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina57111168

Pereira CF, Cheung K, Alie E, Wong J, Esplen MJ, Leung YW. Pathways to Acceptance in Participants of Advanced Cancer Online Support Groups. Medicina. 2021; 57(11):1168. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina57111168

Chicago/Turabian StylePereira, Christina Francesca, Kate Cheung, Elyse Alie, Jiahui Wong, Mary Jane Esplen, and Yvonne W. Leung. 2021. "Pathways to Acceptance in Participants of Advanced Cancer Online Support Groups" Medicina 57, no. 11: 1168. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina57111168