Abstract

Previous evidence from in vivo and observational research suggested how dietary factors might affect DNA methylation signatures involved in obesity risk. However, findings from experimental studies are still scarce and, if present, not so clear. The current review summarizes studies investigating the effect of dietary interventions on DNA methylation in the general population and especially in people at risk for or with obesity. Overall, these studies suggest how dietary interventions may induce DNA methylation changes, which in turn are likely related to the risk of obesity and to different response to weight loss programs. These findings might explain the high interindividual variation in weight loss after a dietary intervention, with some people losing a lot of weight while others much less so. However, the interactions between genetic, epigenetic, environmental and lifestyle factors make the whole framework even more complex and further studies are needed to support the hypothesis of personalized interventions against obesity.

1. Introduction

Obesity is defined as excessive body fat deposition resulting in a disproportionate body weight for height [1]. This condition is usually associated with metabolic disorders, some type of cancer, and cardiovascular diseases [2], which account for a substantial burden for overweight and obese individuals [3]. In the past, the imbalance between caloric intake and energy expenditure was considered the main–and perhaps only–cause of excessive body fat accumulation. More recently, however, this simplistic view is gradually moving towards a more complex scenario involving environmental exposures, socioeconomic factors, and behaviors [4,5]. Among the latter, for instance, the quality of diet, level of physical activity, abuse of alcohol, and lack of sleep play a crucial role in maintaining an appropriate body weight [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. As reported by the World Health Organization (WHO), more than 1.9 billion adults were overweight and of these 650 million were obese in 2016 [14]. These figures make overweight and obesity a priority for public health [3], raising the need for interventions aimed to tackle the progress of what can be considered a global epidemy [14]. Accordingly, several approaches and treatments have been proposed, such as dietary interventions, physical activity programs, drug administration, and bariatric surgery.

In the past decades, several randomized controlled trials evaluated the effects of dietary interventions on body weight management and weight loss [15,16]. Although caloric restriction represents the easiest option to lose weight, improving the quality of diet can also be helpful [17]. However, there is high interindividual variation in weight loss after a dietary intervention, with some people losing a lot of weight while others much less so [15]. What makes this even more complex is that the interactions between genetic, epigenetic and the environmental factors might sustain important individual differences in body weight [18,19]. Genetic variants, for example, might explain important interindividual variation in the response to the same intervention [18,20], even if epidemiological research is needed to estimate the value of their contribution. In the same way, epigenetic mechanisms – including DNA methylation, histone modifications and noncoding RNAs – might play an important role in development of obesity from the early stages of life. Among these mechanisms, DNA methylation is one of the most extensively studied and best characterized. In mammals, DNA methylation is regulated by the activity of three DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs): while DNMT1 has a maintenance role, DNMT3a and 3b are de novo methylases. DNMT functions are associated with several key physiological processes, including genomic imprinting, X-chromosome inactivation, regulation of gene expression, maintenance of chromosome integrity through chromatin modulation, DNA stabilization and DNA-protein interactions [21]. Aberrant DNMT expression and activity are involved in several diseases including cardiovascular diseases, obesity, type-2 diabetes and cancer [22,23,24]. Mounting evidence from observational research has suggested a role in the DNA methylation process of nutrients and foods involved in one-carbon metabolism, as well as that of healthy dietary patterns [25]. In line, some experimental studies investigated the effect of dietary interventions, for example based on folate supplementation and adherence to the Mediterranean diet. In 2018, ElGendy and colleagues summarized experimental studies investigating the effects of dietary interventions on DNA methylation [26]. Specifically, the authors indicated that supplementation with folic acid - an important methyl donor in the DNA methylation process - differently but markedly affects DNA methylation levels in blood samples. Differences, however, depended on study population, sample type, and DNA methylation signature analyzed [26]. ElGendy and colleagues also described early results from experimental studies on the effect of weight-loss programs on DNA methylation signatures [26]. In fact, changes in DNA methylation might be involved in predisposition to obesity and in different response to dietary interventions. It has been already suggested that epigenomic programming of metabolism during the prenatal period – also known as metabolic imprinting – might affect the risk of obesity and other disorders over the lifetime [27,28]. Excessive maternal gestational weight during pregnancy, for example, is a risk factor for developing obesity at birth, as well as during infancy and adolescence [29]. Given that, birthweight can also be considered as a useful surrogate marker of fetal nutrition with a dual effect on the risk of obesity in the later phases of life: in fact, previous studies associated both high and low birthweight to the risk of obesity, excessive body fat, and metabolic disorders [30,31,32,33]. However, how much this transgenerational effect depends on epigenetics still remains to be elucidated [34,35,36].

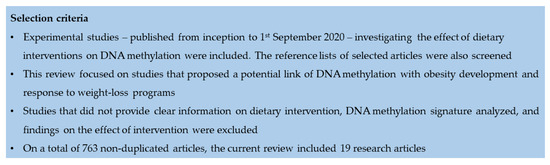

Here, I first described recent findings on the potential relationship between dietary interventions during pregnancy and DNA methylation in cord blood of newborns. Next, I collected experimental studies investigating whether DNA methylation changes - following dietary interventions in adults - might vary according to their birthweight. Finally, I summarized evidence on the effects of weight-loss programs on DNA methylation signatures, taking into account their potential relationship with response to treatment. To do that, a literature search was carried out on PubMed and Web of Science databases by using the MESH terms “Diet” and “DNA Methylation”. Inclusion and exclusion criteria used for study selection are reported in the Figure 1, while methodological characteristics of included studies are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Literature search and selection criteria for experimental studies examining the effects of dietary interventions on DNA methylation.

Table 1.

Summary of experimental studies examining the effects of dietary interventions on DNA methylation.

2. Dietary Interventions during Pregnancy

Potential preventive strategies against obesity should start as early as possible, even during the perinatal period [1]. A recent review of observational studies on mother-child pairs summarized how the interaction between dietary factors and DNA methylation might be related to pregnancy outcomes [25]. Interestingly, the main diet-associated changes in DNA methylation regarded genes in the metabolic and growth pathways, such as insulin-like growth factor 2 (IGF2). This gene encodes for a protein hormone with growth-regulating, insulin-like and mitogenic activities, especially during pregnancy [25].

In spite of promising findings from observational studies, evidence from experimental research is still scarce. To my knowledge, the study by Lee and colleagues was the first investigating the effect of dietary interventions during pregnancy on DNA methylation in newborns [37]. The intervention consisted in dietary supplementation with ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) at 18–22 weeks of gestation. The authors reported an association between ω-3 PUFA supplementation and long interspersed nucleotide elements 1 (LINE-1) methylation levels, especially among newborns of smoker women. It is worth mentioning that observational research associated LINE-1 methylation with several disease in adulthood, including cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, obesity, and metabolic disorders [49,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64]. In 2018, Geraghty and colleagues evaluated the effect of an intervention based on dietetic consulting and written resources to promote healthy dietary habits in general, and low glycemic index diet in particular [38]. Specifically, women in the intervention group were recommended to follow an eucaloric diet but replacing high glycemic foods with low glycemic alternatives. In the discovery cohort of 60 mother-child pairs, children born from mothers in the intervention group exhibited high variation in DNA methylation, especially in genes related to cardiac and immune functions. These results, however, were inconsistent with those obtained in the replication cohort, and no associations with maternal body mass index (BMI), infant sex, or birthweight were evident [38].

3. The Effect of Interventions in Adults According to Their Birthweight

With this in mind, a peculiar study design has been adopted to compare the effect of dietary interventions on DNA methylation between Danish men with normal or low birthweight [39]. Both groups were subjected to a control diet followed by a five-day high-fat overfeeding diet or vice versa, while skeletal muscle biopsies were collected to measure methylation of proliferator-activated receptor-γ, coactivator-1α (PPARGC1A) gene. During the control diet, PPARGC1A methylation was markedly higher in low birthweight individuals than in their counterpart. However, after the overfeeding diet, its methylation level increased only in normal birthweight men [39]. The same research group then evaluated PPARGC1A methylation level in the subcutaneous adipose tissue but achieving opposite findings [40]. Indeed, the high-fat overfeeding intervention increased PPARGC1A methylation level in low birthweight but not in normal birthweight individuals [40]. Nevertheless, these results were important since they suggested that dietary interventions might differently act depending on tissues. It is worth mentioning that PPARGC1A encodes for an important transcriptional coactivator involved in mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative phosphorylation [65,66]. For this reason, PPARGC1A is highly expressed in tissues with high energy demand (e.g. skeletal muscle) [65] and lowly expressed in other tissues, such as white adipose tissue and pancreas [67]. In particular, decreased expression of PPARGC1A might cause insulin resistance by influencing several cellular functions (i.e. mitochondrial function, lipid oxidation, microvascular flow, and oxidative stress) [68,69,70]. However, it could play different roles in skeletal muscle and subcutaneous adipose tissue. To deeply understand how high-fat overfeeding affected DNA methylation in skeletal muscle, the authors also conducted two separate genomewide methylation studies [41,42]. In the first one, no significant differences in DNA methylation were evident between low and normal birthweight individuals. Yet, the overfeeding diet produced more DNA methylation changes in normal birthweight individuals than in those with low birthweight [42]. According to their results, the authors speculated that the decreased plasticity observed in low birthweight individuals might interfere with protective functions of various pathways (e.g. inflammation) and thus might increase their risk for insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes [42]. In the second genomewide study, the authors evaluated the effect of a three-day weight-maintaining diet followed by a five-day high-fat overfeeding diet only in men with normal birthweight [41]. Interestingly, the intervention was associated with more than 6500 differentially methylated regions and only a part of these changes reversed after two months from the intervention. Further analysis underlined that the majority of these differentially methylated regions were associated with pathways involved in inflammation, reproductive activities and cancer [41].

A similar but more complex approach has been adopted to uncover how overfeeding diet affected DNA methylation signatures in subcutaneous adipose tissue [43]. In 2016, the study by Gillberg and colleagues included a discovery cohort (made of low-birthweight men and BMI-matched control men with normal birthweight) and two replication cohorts (composed of elderly monozygotic and dizygotic twins and healthy young individuals, respectively) [43]. In the discovery cohort, there were 53 differentially methylated regions associated with birthweight, such as loci within Fatty Acid Desaturase 2 (FADS2) and Complexin 1 (CPLX1) genes [43], which in turn have been associated with type 2 diabetes [71] and glucose-stimulated insulin release [72], respectively. In the replication cohorts, instead, the intervention was linked to 652 differentially methylated regions within genes that were predominantly related to metabolic pathways (e.g. insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 5, IGFBP5; Solute Carrier Family 2 Member 4, SLC2A4) [43]. More recently, Hjort and colleagues compared the effects of a 72 h control diet of precooked meals followed by 36 h of fasting between men with normal and low birthweight [44]. They showed that leptin (LEP) and adiponectin (ADIPOQ) methylation levels were higher in subcutaneous adipose tissue of low birthweight subjects than in their normal birthweight counterpart. Interestingly, 36 h fasting was associated with increasing DNA methylation levels only in normal birthweight individuals. It is worth mentioning that LEP and ADIPOQ are among the most important adipokines correlated with adipose tissue mass, visceral adiposity, and body fat percentage [73,74].

4. Dietary Interventions against Obesity and Related Disorders

In the last decade, the research on dietary risk factors for obesity also aimed to understand diet-associated changes in DNA methylation. In the context of experimental research, studying DNA methylation could be helpful to uncover molecular mechanisms underpinning different response to weigh loss programs and interventions. In 2011, Milagro and colleagues analyzed the genomewide methylation profile in blood samples of 25 overweight or obese men subjected to an energy-restricted program [22]. The intervention consisted of an eight-week energy-restricted diet with 53% of energy from carbohydrates, 30% from fats, and 17% from proteins. Prior to intervention, ATPase Phospholipid Transporting 10A (ATP10A) and CD44 methylation levels differed between responders and nonresponders. After eight weeks of intervention, instead, the response was associated with methylation status of Wilms’ tumor 1 (WT1) gene [22]. These findings were partially confirmed by Samblas and colleagues in 2018. In fact, the authors demonstrated that CD44 methylation level was lower in individuals who responded less to a weight-loss program if compared with high responders [45]. Interestingly, ATP10A encodes an amino-phospholipid translocase related to lipid trafficking and maintenance of the plasma membrane, which is probably involved in modulating body fat [75]. For this reason, the depletion of ATP10A was used to induce clinical traits of obesity in mice [76]. CD44, instead, is a cell-surface glycoprotein indirectly involved in inflammation and fibrosis [77]. For instance, CD44 expression was upregulated in the liver of obese patients with steatohepatitis, while it was downregulated in subcutaneous adipose tissue after weight loss [78]. WT1 encodes for Kruppel-like zinc-finger protein that can act as oncosuppressor or oncogene in relation to cell type [79]. In line, methylation status of WT1 was extensively investigated in cancer research, but much less in obese patients. This encourage further studies investigating the molecular basis underlying the association observed by Milagro and colleagues. In the same year, Cordero and colleagues analyzed Leptin and Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha (TNF-α) methylation levels in adipose tissue of 27 obese women subjected to a similar eight-week energy-restricted diet [46]. Interestingly, better response to the intervention was associated with lower Leptin and TNF-α methylation. Previous studies already demonstrated that the proinflammatory cytokine TNF-α was overexpressed in obesity and related metabolic disorders and that its production was mediated by epigenetic modifications [80]. Moreover, methylation status of TNF-α in blood samples was previously associated with the response to a low-calorie diet [47].

In 2015, Nicoletti and colleagues recruited 45 women grouped as follows: 22 obese women subjected to a six-month energy restriction program; 14 obese women subjected to a hypocaloric diet followed by bariatric surgery; nine normal weight women [48]. According to this classification, the authors compared IL-6, Serpin Family E Member 1 (SERPINE-1), and LINE-1 methylation level in blood samples. In particular, SERPINE-1 and LINE-1 methylation levels were similar between different groups and not associated with obesity traits. However, LINE-1 methylation was associated with serum glucose levels prior to interventions. Nicoletti and colleagues also noted that IL-6 methylation level was higher in obese women subjected to energy restriction and lower in those who underwent to bariatric surgery [48]. In general, obesity is associated with the release of inflammatory factors - such as IL6 - which in turn induce a chronic state of low-grade inflammation [81,82]. On the contrary, weight loss programs might reduce the inflammatory state of obese patients [83,84]. This evidence partially supports the increased IL6 methylation level observed in the energy-restricted group [48], which may be associated with lower gene expression and protein level. The opposite effect observed in the bariatric surgery group, instead, should be confirmed by future studies. Although the authors speculated that both surgical procedure and fast weight loss could promote an inflammatory state [48], further research is needed to support this hypothesis.

Results on LINE-1 methylation reported by Nicoletti and colleagues were in line with those from observational studies [85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92]. Accordingly, Delgado-Cruzata and colleagues treated 24 overweight and sedentary female breast cancer survivors with a six-month weight loss program. The interventions aimed to increase physical activity and to reduce caloric intake in general and from fats in particular. The authors showed that LINE-1 methylation in blood samples significantly increased after 6–12 months from the intervention, and that its level was positively associated with changes in percentage of body fat and fasting glucose concentration [49]. These findings were consistent with those obtained by researcher of the Metabolic Syndrome Reduction in Navarra (RESMENA) project [50]. In this study, the intervention group consisted of adults subjected to seven meals per day with a macronutrient distribution of 40% total caloric value from carbohydrates, 30% from proteins and 30% from lipids. Subjects in the control group, instead, were asked to adhere to the American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines (i.e. three to five meals per day and a macronutrient distribution of 55% total caloric value from carbohydrates, 15% from proteins, and 30% from lipids). Interestingly, baseline LINE-1 methylation level was higher in patients with higher weight loss independent of intervention [50]. Yet, other studies found opposite or inconsistent results about the putative association between dietary interventions and LINE-1 methylation. For instance, Martin-Nunez and colleagues showed a reduction in LINE-1 methylation level after a 12-month intervention aiming to promote adherence to the Mediterranean diet and exercise [51]. Duggan and colleagues, instead, failed in demonstrating any significant difference in LINE-1 methylation level among overweight women randomized to three different intervention groups [52].

Finally, there were other studies that needed further confirmation due to their specific nature. This was the case, for example, of the study by Samblas and colleagues in 2016. The author, indeed, investigated the effect of dietary interventions on DNA methylation of genes involved in the circadian clock system [53]. The intervention consisted in the promotion of Mediterranean diet and physical activity among 61 overweight or obese women. This research, for the first time, pointed out an association between BMAL1 (brain and muscle aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator like protein 1) methylation and an intervention, which in turn resulted in weight loss and decreased blood lipids levels. BMAL1 is a transcription factor that regulates the mammalian clock machinery. Interestingly, previous studies already demonstrated the involvement of BMAL1 in the regulation of adipogenesis and lipid metabolism, as well as in hyperlipidemic and hyperglycemic periods in obese subjects [53]. Another peculiar study was that by Sun and colleagues, which tested the potential interactions between dietary interventions and NFATC2IP (Nuclear Factor Of Activated T Cells 2 Interacting Protein) genotype, DNA methylation, and gene expression on two-year weight change [54]. Dietary interventions consisted of four low-calorie diets with different macronutrient composition. Interestingly, NFATC2IP methylation exhibited an opposite effect on weight-loss in response to high-fat or low-fat diets. Moreover, NFATC2IP methylation mediated about half of the effect of rs11150675 NFATC2IP genetic polymorphism on two-year weight-loss following the high-fat diet [54]. To my knowledge, this is the first evidence of an interaction between genetic variants and DNA methylation on response to weight-loss programs, and hence further studies should be encouraged to corroborate these findings.

5. Discussion

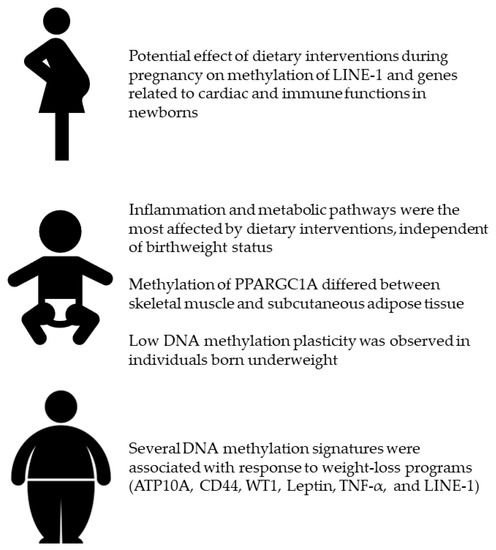

Several lines of evidence already described the relationship of dietary factors (i.e. nutrients, foods, and dietary patterns) with DNA methylation signatures that might be involved in health and diseases [25]. Although the majority of findings originated from in vivo and observational research, ElGendy and colleagues summarized experimental studies conducted to elucidate the effect of various dietary interventions [26]. Their compelling work demonstrated how different interventions differentially affected DNA methylation signatures in blood samples and other specimens. For instance, a lot of studies conducted among “healthy” people evaluated the effect of folate supplementation [93,94] and Mediterranean diet promotion [95,96]. Interestingly, folate intake and supplementation differently affected DNA methylation signatures, and this difference was due to participants’ characteristics, sample types and genomic sites under investigation [93,94]. With respect to the Mediterranean diet, the PREDIMED study produced the most interesting results, suggesting that the majority of differentially methylated regions were located in genes involved in inflammation, immunocompetence, signal transduction and metabolic pathways [95,96]. ElGendy and colleagues also reported that some DNA methylation changes might be associated with obesity development and response to weight-loss program [26]. For this reason, the present review collected all the experimental studies investigating the effect of dietary interventions on DNA methylation, with a particular focus on those suggesting a potential link with obesity. Specifically, I focused on (i) dietary interventions during pregnancy (i.e. a crucial period for developing obesity later in life); (ii) studies evaluating if birthweight might affect DNA methylation changes following a dietary intervention; (iii) and those investigating the effect of weight-loss and/or energy-restricted programs. Figure 2 illustrates the most important findings presented in the current review.

Figure 2.

Effect of dietary interventions during pregnancy, in adults according to their birthweight, and in overweight or obese individuals.

With regard to the first point, however, experimental studies on mother-child pairs were scarce, with some controversial results that therefore required further investigation [38]. Yet, birthweight is one of the main neonatal outcomes associated with the risk of obesity and related disorders in the childhood, adolescence, and adulthood [97]. For this reason, several studies compared the effect of dietary interventions on DNA methylation between individuals born underweight or normal weight [39,40,41,42]. The main purpose of these studies was to provide an explanation of differences in the response to different dietary interventions when patients were stratified by their birthweight. These studies – conducted with a similar study design – indicated several DNA methylation signatures that differed between individuals with normal or low birthweight [39,40,41,42]. In this framework, methylation of PPARGC1A was that has attracted more interest due to its opposite path in skeletal muscle and subcutaneous adipose tissue [39,40]. However, tissue-specific effects of PPARGC1A methylation still remain to be elucidated. Another hypothesis to test regards the low DNA methylation plasticity observed in individuals born underweight. Indeed, subjects with low birthweight exhibited a less marked effect of dietary intervention on their DNA methylation profile [42]. In fact, DNA methylation changes-induced by dietary interventions in individuals with normal birthweight-might stimulate some pathways (e.g. inflammation) with protective functions against obesity-related disorders [42]. By contrast, the low plasticity observed in those with low birthweight might increase their risk for insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes [42]. Of note, inflammation and metabolic pathways seemed the most affected by dietary interventions independent of birthweight status [39,40,41,42]. Overall, these findings provide grounds to hypothesize that dietary interventions might modulate the DNA methylation processes, and that their effects are likely related to the risk of obesity and to different response to weight loss programs. In line, some studies evaluated how dietary interventions based on energy restriction might induce changes in DNA methylation. Interestingly, several DNA methylation signatures seemed associated with weight-loss response (e.g. ATP10A, CD44, WT1, Leptin, TNF-α, and LINE-1) [22,46,48,49,50]. However, the current review also raised several aspects that might prevent the comparison between different studies. Several studies were not randomized, while others did not report clearly report some important methodological aspects. This was important because differences in study design and dietary interventions, peculiar characteristics of the study population, as well as heterogeneity in sample types, loci analyzed, and methods used for estimating DNA methylation, might lead to different - and sometimes opposing - results.

In conclusion, findings described in the present review are promising, suggesting the possibility to individualize the weight-loss interventions according to specific DNA methylation signatures. However, further studies conducted on large-size populations with a standardized protocol are necessary to produce robust evidence and to integrate DNA methylation data with genetic profile and other characteristics of patients.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| DNMTs | DNA methyltransferases |

| IGF2 | Insulin-like growth factor 2 |

| LINE-1 | Long interspersed nuclear elements 1 |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| PPARGC1A | Proliferator-activated receptor-γ, coactivator-1α |

| FADS2 | Fatty Acid Desaturase 2 |

| CPLX1 | Complexin 1 |

| IGFBP5 | Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 5 |

| SLC2A4 | Solute Carrier Family 2 Member 4 |

| LEP | Leptin |

| ADIPQ | Adiponectin |

| MTHFR | Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase |

| PREDIMED | Prevención con Dieta Mediterránea |

| GOLDN | Genetics of Lipid Lowering Drugs and Diet Network |

| LPP | Lipoma-preferred partner |

| APOA5 | Apolipoprotein A-5 |

| SREBF1 | Sterol regulatory element-binding transcription factor 1 |

| ABCG1 | ATP-binding cassette sub-family G member 1 |

| CPT1A | Carnitine palmitoyl-transferase 1-A |

| PUFA | Polyunsaturated fatty acids |

| SFA | Saturated fatty acids |

| FTO | Alpha-ketoglutarate dependent dioxygenase |

| IL6 | Interleukin 6 |

| INSR | Insulin receptor |

| NEGR1 | Neuronal growth regulator 1 |

| POMC | Proopiomelanocortin |

| ATP10A | ATPase Phospholipid Transporting 10A |

| WT1 | Wilms’ tumor 1 |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha |

| SERPINE-1 | Serpin Family E Member 1 |

| RESMENA | Metabolic Syndrome Reduction in Navarra |

| AHA | American Heart Association |

| BMAL1 | Brain and muscle aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator–like protein 1 |

| NFATC2IP | Nuclear Factor Of Activated T Cells 2 Interacting Protein |

References

- González-Muniesa, P.; Mártinez-González, M.A.; Hu, F.B.; Després, J.P.; Matsuzawa, Y.; Loos, R.J.F.; Moreno, L.A.; Bray, G.A.; Martinez, J.A. Obesity. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2017, 3, 17034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, E.P.; Mesidor, M.; Winters, K.; Dubbert, P.M.; Wyatt, S.B. Overweight and obesity: Prevalence, consequences, and causes of a growing public health problem. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2015, 4, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroes, M.; Osei-Assibey, G.; Baker-Searle, R.; Huang, J. Impact of weight change on quality of life in adults with overweight/obesity in the United States: A systematic review. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2016, 32, 485–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genné-Bacon, E.A. Thinking evolutionarily about obesity. Yale J. Biol. Med. 2014, 87, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sellayah, D.; Cagampang, F.R.; Cox, R.D. On the evolutionary origins of obesity: A new hypothesis. Endocrinology 2014, 155, 1573–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maugeri, A.; Kunzova, S.; Medina-Inojosa, J.R.; Agodi, A.; Barchitta, M.; Homolka, M.; Kiacova, N.; Bauerova, H.; Sochor, O.; Lopez-Jimenez, F.; et al. Association between eating time interval and frequency with ideal cardiovascular health: Results from a random sample Czech urban population. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agodi, A.; Maugeri, A.; Kunzova, S.; Sochor, O.; Bauerova, H.; Kiacova, N.; Barchitta, M.; Vinciguerra, M. Association of dietary patterns with metabolic syndrome: Results from the Kardiovize Brno 2030 Study. Nutrients 2018, 10, 898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maugeri, A.; Barchitta, M.; Fiore, V.; Rosta, G.; Favara, G.; La Mastra, C.; La Rosa, M.C.; Magnano San Lio, R.; Agodi, A. Determinants of adherence to the Mediterranean diet: Findings from a cross-sectional study in women from Southern Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunzova, S.; Maugeri, A.; Medina-Inojosa, J.; Lopez-Jimenez, F.; Vinciguerra, M.; Marques-Vidal, P. Determinants of metabolic health across body mass index categories in Central Europe: A comparison between Swiss and Czech populations. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maugeri, A.; Barchitta, M.; Agrifoglio, O.; Favara, G.; La Mastra, C.; La Rosa, M.C.; Magnano San Lio, R.; Panella, M.; Cianci, A.; Agodi, A. The impact of social determinants and lifestyles on dietary patterns during pregnancy: Evidence from the “Mamma & Bambino” study. Ann. Ig. 2019, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maugeri, A.; Barchitta, M.; Favara, G.; La Rosa, M.C.; La Mastra, C.; Magnano San Lio, R.; Agodi, A. Maternal dietary patterns are associated with pre-pregnancy body mass index and gestational weight gain: Results from the “Mamma & Bambin” cohort. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Inojosa, J.R.; Vinciguerra, M.; Maugeri, A.; Kunzova, S.; Sochor, O.; Movsisyan, N.; Geda, Y.E.; Stokin, G.B.; Lopez-Jimenez, F. Prevalence of ideal cardiovascular health in a Central European community: Results from the Kardiovize Brno 2030 Project. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maugeri, A.; Medina-Inojosa, J.R.; Kunzova, S.; Agodi, A.; Barchitta, M.; Sochor, O.; Lopez-Jimenez, F.; Geda, Y.E.; Vinciguerra, M. Sleep duration and excessive daytime sleepiness are associated with obesity independent of diet and physical activity. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Obesity and Overweight. Available online: https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 10 September 2020).

- Bray, G.A.; Siri-Tarino, P.W. The role of macronutrient content in the diet for weight management. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. North. Am. 2016, 45, 581–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, J.A.; Navas-Carretero, S.; Saris, W.H.; Astrup, A. Personalized weight loss strategies—The role of macronutrient distribution. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2014, 10, 749–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozaffarian, D. Dietary and policy priorities for cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and obesity: A comprehensive review. Circulation 2016, 133, 187–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, T.W.; Justice, A.E.; Graff, M.; Barata, L.; Feitosa, M.F.; Chu, S.; Czajkowski, J.; Esko, T.; Fall, T.; Kilpeläinen, T.O.; et al. The influence of age and sex on genetic associations with adult body size and shape: A large-scale genome-wide interaction study. PLoS Genet. 2015, 11, e1005378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Re, O.; Maugeri, A.; Hruskova, J.; Jakubik, J.; Kucera, J.; Bienertova-Vasku, J.; Oben, J.A.; Kubala, L.; Dvorakova, A.; Ciz, M.; et al. Obesity-induced nucleosome release predicts poor cardio-metabolic health. Clin. Epigenetics 2019, 12, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elks, C.E.; den Hoed, M.; Zhao, J.H.; Sharp, S.J.; Wareham, N.J.; Loos, R.J.; Ong, K.K. Variability in the heritability of body mass index: A systematic review and meta-regression. Front. Endocrinol. 2012, 3, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.H.; Fei, J.; Lan, M.S.; Lu, Z.P.; Liu, M.; Fan, W.W.; Gao, X.; Lu, D.R. Hypermethylation of hepatic Gck promoter in ageing rats contributes to diabetogenic potential. Diabetologia 2008, 51, 1525–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milagro, F.I.; Campión, J.; Cordero, P.; Goyenechea, E.; Gómez-Uriz, A.M.; Abete, I.; Zulet, M.A.; Martínez, J.A. A dual epigenomic approach for the search of obesity biomarkers: DNA methylation in relation to diet-induced weight loss. FASEB J. 2011, 25, 1378–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maier, S.; Olek, A. Diabetes: A candidate disease for efficient DNA methylation profiling. J. Nutr. 2002, 132, 2440S–2443S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowdhury, S.; Erickson, S.W.; MacLeod, S.L.; Cleves, M.A.; Hu, P.; Karim, M.A.; Hobbs, C.A. Maternal genome-wide DNA methylation patterns and congenital heart defects. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e16506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maugeri, A.; Barchitta, M. How dietary factors affect DNA methylation: Lesson from epidemiological studies. Medicina 2020, 56, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ElGendy, K.; Malcomson, F.C.; Lara, J.G.; Bradburn, D.M.; Mathers, J.C. Effects of dietary interventions on DNA methylation in adult humans: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Nutr. 2018, 120, 961–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanley, B.; Dijane, J.; Fewtrell, M.; Grynberg, A.; Hummel, S.; Junien, C.; Koletzko, B.; Lewis, S.; Renz, H.; Symonds, M.; et al. Metabolic imprinting, programming and epigenetics-a review of present priorities and future opportunities. Br. J. Nutr. 2010, 104, S1–S25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eriksson, J.G. Developmental origins of health and disease-from a small body size at birth to epigenetics. Ann. Med. 2016, 48, 456–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tielemans, M.J.; Garcia, A.H.; Peralta Santos, A.; Bramer, W.M.; Luksa, N.; Luvizotto, M.J.; Moreira, E.; Topi, G.; de Jonge, E.A.; Visser, T.L.; et al. Macronutrient composition and gestational weight gain: A systematic review. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 103, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dearden, L.; Ozanne, S.E. Early life origins of metabolic disease: Developmental programming of hypothalamic pathways controlling energy homeostasis. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2015, 39, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Lim, I.Y.; Wu, Y.; Teh, A.L.; Chen, L.; Aris, I.M.; Soh, S.E.; Tint, M.T.; MacIsaac, J.L.; Morin, A.M.; et al. Developmental pathways to adiposity begin before birth and are influenced by genotype, prenatal environment and epigenome. BMC Med. 2017, 15, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.B.; Han, S.P.; Zhu, G.Z.; Zhu, C.; Wang, X.J.; Cao, X.G.; Guo, X.R. Birth weight and subsequent risk of obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2011, 12, 525–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labayen, I.; Ruiz, J.R.; Vicente-Rodríguez, G.; Turck, D.; Rodríguez, G.; Meirhaeghe, A.; Molnár, D.; Sjöström, M.; Castillo, M.J.; Gottrand, F.; et al. Early life programming of abdominal adiposity in adolescents: The HELENA Study. Diabetes Care 2009, 32, 2120–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravelli, G.P.; Stein, Z.A.; Susser, M.W. Obesity in young men after famine exposure in utero and early infancy. N. Engl. J. Med. 1976, 295, 349–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tobi, E.W.; Lumey, L.H.; Talens, R.P.; Kremer, D.; Putter, H.; Stein, A.D.; Slagboom, P.E.; Heijmans, B.T. DNA methylation differences after exposure to prenatal famine are common and timing- and sex-specific. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2009, 18, 4046–4053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heijmans, B.T.; Tobi, E.W.; Stein, A.D.; Putter, H.; Blauw, G.J.; Susser, E.S.; Slagboom, P.E.; Lumey, L.H. Persistent epigenetic differences associated with prenatal exposure to famine in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 17046–17049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.S.; Barraza-Villarreal, A.; Hernandez-Vargas, H.; Sly, P.D.; Biessy, C.; Ramakrishnan, U.; Romieu, I.; Herceg, Z. Modulation of DNA methylation states and infant immune system by dietary supplementation with ω-3 PUFA during pregnancy in an intervention study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 98, 480–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geraghty, A.A.; Sexton-Oates, A.; O’Brien, E.C.; Alberdi, G.; Fransquet, P.; Saffery, R.; McAuliffe, F.M. A Low glycaemic index diet in pregnancy induces DNA methylation variation in blood of newborns: Results from the ROLO randomised controlled trial. Nutrients 2018, 10, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brøns, C.; Jacobsen, S.; Nilsson, E.; Rönn, T.; Jensen, C.B.; Storgaard, H.; Poulsen, P.; Groop, L.; Ling, C.; Astrup, A.; et al. Deoxyribonucleic acid methylation and gene expression of PPARGC1A in human muscle is influenced by high-fat overfeeding in a birth-weight-dependent manner. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 95, 3048–3056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillberg, L.; Jacobsen, S.C.; Rönn, T.; Brøns, C.; Vaag, A. PPARGC1A DNA methylation in subcutaneous adipose tissue in low birth weight subjects—impact of 5 days of high-fat overfeeding. Metabolism 2014, 63, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, S.C.; Brøns, C.; Bork-Jensen, J.; Ribel-Madsen, R.; Yang, B.; Lara, E.; Hall, E.; Calvanese, V.; Nilsson, E.; Jørgensen, S.W.; et al. Effects of short-term high-fat overfeeding on genome-wide DNA methylation in the skeletal muscle of healthy young men. Diabetologia 2012, 55, 3341–3349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, S.C.; Gillberg, L.; Bork-Jensen, J.; Ribel-Madsen, R.; Lara, E.; Calvanese, V.; Ling, C.; Fernandez, A.F.; Fraga, M.F.; Poulsen, P.; et al. Young men with low birthweight exhibit decreased plasticity of genome-wide muscle DNA methylation by high-fat overfeeding. Diabetologia 2014, 57, 1154–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillberg, L.; Perfilyev, A.; Brøns, C.; Thomasen, M.; Grunnet, L.G.; Volkov, P.; Rosqvist, F.; Iggman, D.; Dahlman, I.; Risérus, U.; et al. Adipose tissue transcriptomics and epigenomics in low birthweight men and controls: Role of high-fat overfeeding. Diabetologia 2016, 59, 799–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hjort, L.; Jørgensen, S.W.; Gillberg, L.; Hall, E.; Brøns, C.; Frystyk, J.; Vaag, A.A.; Ling, C. 36 h fasting of young men influences adipose tissue DNA methylation of. Clin. Epigenetics 2017, 9, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samblas, M.; Mansego, M.L.; Zulet, M.A.; Milagro, F.I.; Martinez, J.A. An integrated transcriptomic and epigenomic analysis identifies CD44 gene as a potential biomarker for weight loss within an energy-restricted program. Eur. J. Nutr. 2019, 58, 1971–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordero, P.; Campion, J.; Milagro, F.I.; Goyenechea, E.; Steemburgo, T.; Javierre, B.M.; Martinez, J.A. Leptin and TNF-alpha promoter methylation levels measured by MSP could predict the response to a low-calorie diet. J. Physiol. Biochem. 2011, 67, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campión, J.; Milagro, F.I.; Goyenechea, E.; Martínez, J.A. TNF-alpha promoter methylation as a predictive biomarker for weight-loss response. Obesity 2009, 17, 1293–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicoletti, C.F.; Nonino, C.B.; de Oliveira, B.A.; Pinhel, M.A.; Mansego, M.L.; Milagro, F.I.; Zulet, M.A.; Martinez, J.A. DNA methylation and hydroxymethylation levels in relation to two weight loss strategies: Energy-restricted diet or bariatric surgery. Obes. Surg. 2016, 26, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Cruzata, L.; Zhang, W.; McDonald, J.A.; Tsai, W.Y.; Valdovinos, C.; Falci, L.; Wang, Q.; Crew, K.D.; Santella, R.M.; Hershman, D.L.; et al. Dietary modifications, weight loss, and changes in metabolic markers affect global DNA methylation in Hispanic, African American, and Afro-Caribbean breast cancer survivors. J. Nutr. 2015, 145, 783–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Lacarte, M.; Milagro, F.I.; Zulet, M.A.; Martinez, J.A.; Mansego, M.L. LINE-1 methylation levels, a biomarker of weight loss in obese subjects, are influenced by dietary antioxidant capacity. Redox Rep. 2016, 21, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Núñez, G.M.; Cabrera-Mulero, R.; Rubio-Martín, E.; Rojo-Martínez, G.; Olveira, G.; Valdés, S.; Soriguer, F.; Castaño, L.; Morcillo, S. Methylation levels of the SCD1 gene promoter and LINE-1 repeat region are associated with weight change: An intervention study. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2014, 58, 1528–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duggan, C.; Xiao, L.; Terry, M.B.; McTiernan, A. No effect of weight loss on LINE-1 methylation levels in peripheral blood leukocytes from postmenopausal overweight women. Obesity 2014, 22, 2091–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samblas, M.; Milagro, F.I.; Gómez-Abellán, P.; Martínez, J.A.; Garaulet, M. Methylation on the circadian gene BMAL1 is associated with the effects of a weight loss intervention on serum lipid levels. J. Biol. Rhythm. 2016, 31, 308–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Heianza, Y.; Li, X.; Shang, X.; Smith, S.R.; Bray, G.A.; Sacks, F.M.; Qi, L. Genetic, epigenetic and transcriptional variations at NFATC2IP locus with weight loss in response to diet interventions: The POUNDS Lost Trial. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2018, 20, 2298–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barchitta, M.; Quattrocchi, A.; Maugeri, A.; Vinciguerra, M.; Agodi, A. LINE-1 hypomethylation in blood and tissue samples as an epigenetic marker for cancer risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e109478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barchitta, M.; Quattrocchi, A.; Maugeri, A.; Canto, C.; La Rosa, N.; Cantarella, M.A.; Spampinato, G.; Scalisi, A.; Agodi, A. LINE-1 hypermethylation in white blood cell DNA is associated with high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. BMC Cancer 2017, 17, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollati, V.; Schwartz, J.; Wright, R.; Litonjua, A.; Tarantini, L.; Suh, H.; Sparrow, D.; Vokonas, P.; Baccarelli, A. Decline in genomic DNA methylation through aging in a cohort of elderly subjects. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2009, 130, 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollati, V.; Galimberti, D.; Pergoli, L.; Dalla Valle, E.; Barretta, F.; Cortini, F.; Scarpini, E.; Bertazzi, P.A.; Baccarelli, A. DNA methylation in repetitive elements and Alzheimer disease. Brain Behav. Immun. 2011, 25, 1078–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carraro, J.C.; Mansego, M.L.; Milagro, F.I.; Chaves, L.O.; Vidigal, F.C.; Bressan, J.; Martínez, J.A. LINE-1 and inflammatory gene methylation levels are early biomarkers of metabolic changes: Association with adiposity. Biomarkers 2016, 21, 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.Y.; James, S.R.; Link, P.A.; McCann, S.E.; Hong, C.C.; Davis, W.; Nesline, M.K.; Ambrosone, C.B.; Karpf, A.R. Association between global DNA hypomethylation in leukocytes and risk of breast cancer. Carcinogenesis 2009, 30, 1889–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maugeri, A.; Barchitta, M.; Fallico, M.; Castellino, N.; Reibaldi, M.; Agodi, A. Characterization of SIRT1/DNMTs functions and LINE-1 methylation in patients with age-related macular degeneration. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreira, P.E.; Richardson, S.R.; Faulkner, G.J. L1 retrotransposons, cancer stem cells and oncogenesis. FEBS J. 2014, 281, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barchitta, M.; Maugeri, A.; Li Destri, G.; Basile, G.; Agodi, A. Epigenetic biomarkers in colorectal cancer patients receiving adjuvant or neoadjuvant therapy: A systematic review of epidemiological studies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agodi, A.; Barchitta, M.; Maugeri, A.; Basile, G.; Zamboni, M.; Bernardini, G.; Corona, D.; Veroux, M. Unveiling the role of DNA methylation in kidney transplantation: Novel perspectives toward biomarker identification. Biomed. Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 1602539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puigserver, P.; Wu, Z.; Park, C.W.; Graves, R.; Wright, M.; Spiegelman, B.M. A cold-inducible coactivator of nuclear receptors linked to adaptive thermogenesis. Cell 1998, 92, 829–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Puigserver, P.; Andersson, U.; Zhang, C.; Adelmant, G.; Mootha, V.; Troy, A.; Cinti, S.; Lowell, B.; Scarpulla, R.C.; et al. Mechanisms controlling mitochondrial biogenesis and respiration through the thermogenic coactivator PGC-1. Cell 1999, 98, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esterbauer, H.; Oberkofler, H.; Krempler, F.; Patsch, W. Human peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma coactivator 1 (PPARGC1) gene: cDNA sequence, genomic organization, chromosomal localization, and tissue expression. Genomics 1999, 62, 98–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mootha, V.K.; Handschin, C.; Arlow, D.; Xie, X.; St. Pierre, J.; Sihag, S.; Yang, W.; Altshuler, D.; Puigserver, P.; Patterson, N.; et al. Erralpha and Gabpa/b specify PGC-1alpha-dependent oxidative phosphorylation gene expression that is altered in diabetic muscle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 6570–6575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koves, T.R.; Li, P.; An, J.; Akimoto, T.; Slentz, D.; Ilkayeva, O.; Dohm, G.L.; Yan, Z.; Newgard, C.B.; Muoio, D.M. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma co-activator 1alpha-mediated metabolic remodeling of skeletal myocytes mimics exercise training and reverses lipid-induced mitochondrial inefficiency. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 33588–33598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St-Pierre, J.; Drori, S.; Uldry, M.; Silvaggi, J.M.; Rhee, J.; Jäger, S.; Handschin, C.; Zheng, K.; Lin, J.; Yang, W.; et al. Suppression of reactive oxygen species and neurodegeneration by the PGC-1 transcriptional coactivators. Cell 2006, 127, 397–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, M.; Li, J.; Xie, T.; He, T.; Fang, L.; Shi, Y.; Hou, L.; Lian, K.; Wang, R.; Jiang, L. Polymorphisms of rs174616 in the FADS1-FADS2 gene cluster is associated with a reduced risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in northern Han Chinese people. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2015, 109, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abderrahmani, A.; Niederhauser, G.; Plaisance, V.; Roehrich, M.E.; Lenain, V.; Coppola, T.; Regazzi, R.; Waeber, G. Complexin I regulates glucose-induced secretion in pancreatic beta-cells. J. Cell Sci. 2004, 117, 2239–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.M. Leptin and the regulation of body weigh. Keio J. Med. 2011, 60, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuzawa, Y. Adiponectin: A key player in obesity related disorders. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2010, 16, 1896–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuBose, A.J.; Johnstone, K.A.; Smith, E.Y.; Hallett, R.A.; Resnick, J.L. Atp10a, a gene adjacent to the PWS/AS gene cluster, is not imprinted in mouse and is insensitive to the PWS-IC. Neurogenetics 2010, 11, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, M.S.; Sommardahl, C.S.; Kirkland, T.; Nelson, S.; Donnell, R.; Johnson, D.K.; Castellani, L.W. Mice heterozygous for Atp10c, a putative amphipath, represent a novel model of obesity and type 2 diabetes. J. Nutr. 2004, 134, 799–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satoh, T.; Ichida, T.; Matsuda, Y.; Sugiyama, M.; Yonekura, K.; Ishikawa, T.; Asakura, H. Interaction between hyaluronan and CD44 in the development of dimethylnitrosamine-induced liver cirrhosis. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2000, 15, 402–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertola, A.; Deveaux, V.; Bonnafous, S.; Rousseau, D.; Anty, R.; Wakkach, A.; Dahman, M.; Tordjman, J.; Clément, K.; McQuaid, S.E.; et al. Elevated expression of osteopontin may be related to adipose tissue macrophage accumulation and liver steatosis in morbid obesity. Diabetes 2009, 58, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Han, Y.; Suarez Saiz, F.; Saurez Saiz, F.; Minden, M.D. A tumor suppressor and oncogene: The WT1 story. Leukemia 2007, 21, 868–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, K.E.; Reddy, A.B.; Dietzmann, K.; Suriano, A.R.; Kocieda, V.P.; Stewart, M.; Bhatia, M. Epigenetic regulation of tumor necrosis factor alpha. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007, 27, 5147–5160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonet, A.C.; Karnikowski, M.; Moraes, C.F.; Gomes, L.; Karnikowski, M.G.; Córdova, C.; Nóbrega, O.T. Association between the -174 G/C promoter polymorphism of the interleukin-6 gene and cardiovascular disease risk factors in Brazilian older women. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2008, 41, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moleres, A.; Rendo-Urteaga, T.; Azcona, C.; Martínez, J.A.; Gómez-Martínez, S.; Ruiz, J.R.; Moreno, L.A.; Marcos, A.; Marti, A.; AVENA group. Il6 gene promoter polymorphism (-174G/C) influences the association between fat mass and cardiovascular risk factors. J. Physiol. Biochem. 2009, 65, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roth, C.L.; Kratz, M.; Ralston, M.M.; Reinehr, T. Changes in adipose-derived inflammatory cytokines and chemokines after successful lifestyle intervention in obese children. Metabolism 2011, 60, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bocca, G.; Corpeleijn, E.; Stolk, R.P.; Wolffenbuttel, B.H.; Sauer, P.J. Effect of obesity intervention programs on adipokines, insulin resistance, lipid profile, and low-grade inflammation in 3- to 5-y-old children. Pediatr. Res. 2014, 75, 352–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Zhang, F.F.; Santella, R.M.; Wolff, M.; Kappil, M.A.; Markowitz, S.B.; Morabia, A. White blood cell global methylation and IL-6 promoter methylation in association with diet and lifestyle risk factors in a cancer-free population. Epigenetics 2012, 7, 606–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, M.S.; McConnell, J.C.; Potter, C.; Barrett, L.M.; Parker, L.; Mathers, J.C.; Relton, C.L. Global LINE-1 DNA methylation is associated with blood glycaemic and lipid profiles. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2012, 41, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barchitta, M.; Maugeri, A.; Magnano San Lio, R.; Favara, G.; La Rosa, M.C.; La Mastra, C.; Quattrocchi, A.; Agodi, A. Dietary patterns are associated with leukocyte LINE-1 methylation in women: A cross-sectional study in Southern Italy. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barchitta, M.; Maugeri, A.; Quattrocchi, A.; Barone, G.; Mazzoleni, P.; Catalfo, A.; De Guidi, G.; Iemmolo, M.G.; Crimi, N.; Agodi, A. Mediterranean diet and particulate matter exposure are associated with LINE-1 methylation: Results from a cross-sectional study in women. Front. Genet. 2018, 9, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maugeri, A.; Barchitta, M.; Magnano San Lio, R.; Favara, G.; La Rosa, M.C.; La Mastra, C.; Basile, G.; Agodi, A. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet partially mediates socioeconomic differences in leukocyte LINE-1 methylation: Evidence from a cross-sectional study in Italian women. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 14360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maugeri, A.; Mazzone, M.G.; Giuliano, F.; Vinciguerra, M.; Basile, G.; Barchitta, M.; Agodi, A. Curcumin modulates DNA methyltransferase functions in a cellular model of diabetic retinopathy. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 5407482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maugeri, A.; Barchitta, M.; Mazzone, M.G.; Giuliano, F.; Basile, G.; Agodi, A. Resveratrol modulates SIRT1 and DNMT functions and restores LINE-1 methylation levels in ARPE-19 cells under oxidative stress and inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agodi, A.; Barchitta, M.; Quattrocchi, A.; Maugeri, A.; Canto, C.; Marchese, A.E.; Vinciguerra, M. Low fruit consumption and folate deficiency are associated with LINE-1 hypomethylation in women of a cancer-free population. Genes Nutr. 2015, 10, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Axume, J.; Smith, S.S.; Pogribny, I.P.; Moriarty, D.J.; Caudill, M.A. Global leukocyte DNA methylation is similar in African American and Caucasian women under conditions of controlled folate intake. Epigenetics 2007, 2, 66–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Shin, W.; Yan, J.; Abratte, C.M.; Vermeylen, F.; Caudill, M.A. Choline intake exceeding current dietary recommendations preserves markers of cellular methylation in a genetic subgroup of folate-compromised men. J. Nutr. 2010, 140, 975–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arpón, A.; Riezu-Boj, J.I.; Milagro, F.I.; Marti, A.; Razquin, C.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Corella, D.; Estruch, R.; Casas, R.; Fitó, M.; et al. Adherence to Mediterranean diet is associated with methylation changes in inflammation-related genes in peripheral blood cells. J. Physiol. Biochem. 2016, 73, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arpón, A.; Milagro, F.I.; Razquin, C.; Corella, D.; Estruch, R.; Fitó, M.; Marti, A.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Ros, E.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; et al. Impact of consuming extra-virgin olive oil or nuts within a Mediterranean diet on DNA methylation in peripheral white blood cells within the PREDIMED-Navarra randomized controlled trial: A Role for dietary lipids. Nutrients 2017, 10, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Druet, C.; Stettler, N.; Sharp, S.; Simmons, R.K.; Cooper, C.; Smith, G.D.; Ekelund, U.; Lévy-Marchal, C.; Jarvelin, M.R.; Kuh, D.; et al. Prediction of childhood obesity by infancy weight gain: An individual-level meta-analysis. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 2012, 26, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).