The Prevalence of Falls Among Older Adults Living in Long-Term Care Facilities in the City of Cape Town

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Procedure

2.2. Fall-Risk Assessment Tool

2.3. Data Analysis

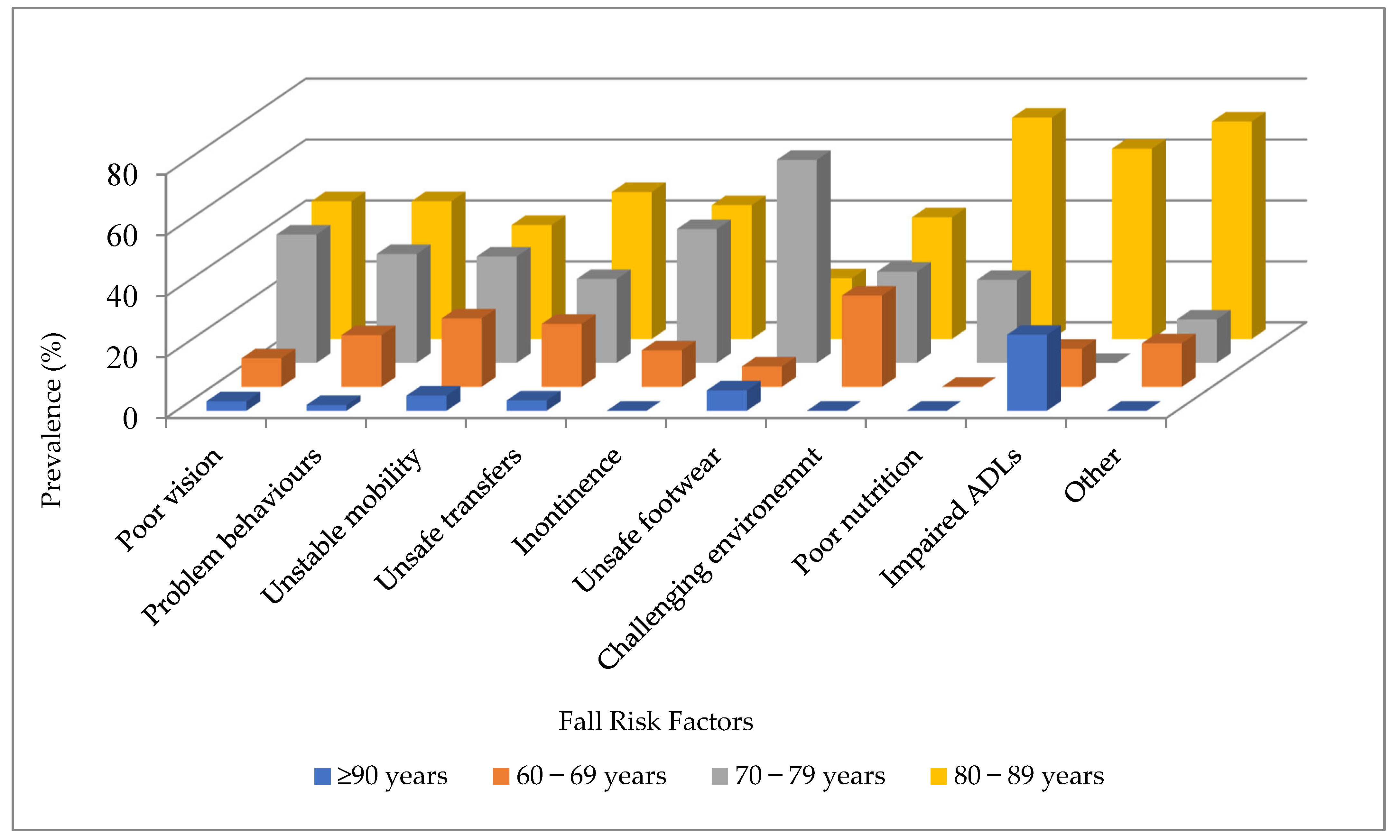

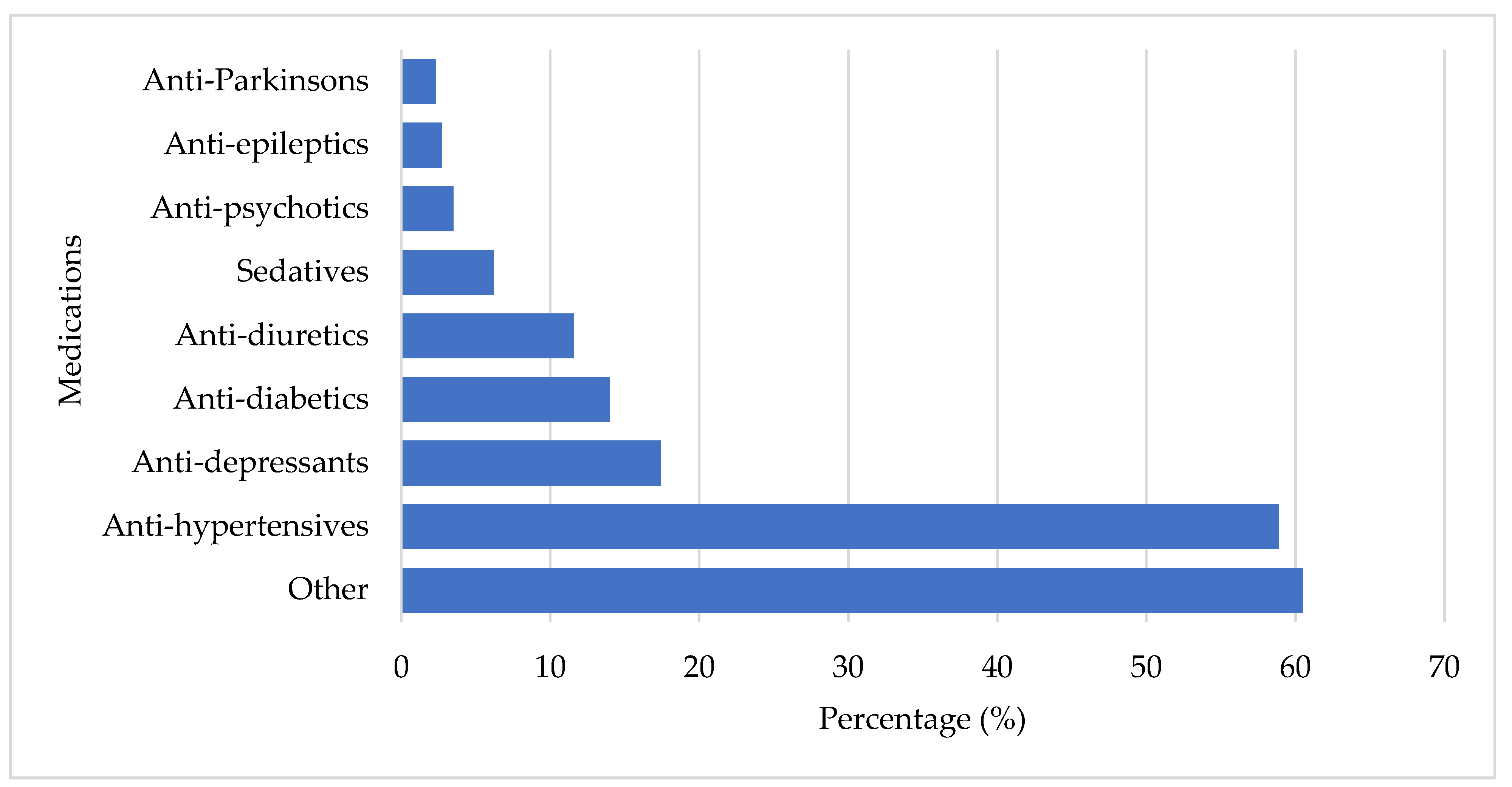

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LTC | Long-term care |

| FRAT | Fall-risk assessment tool |

References

- Jiang, Y.; Xia, Q.; Zhou, P.; Jiang, S.; Diwan, V.K.; Xu, B. Falls and Fall-Related Consequences among Older People Living in Long-Term Care Facilities in a Megacity of China. Gerontology 2020, 66, 523–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damián, J.; Roberto Pastor-Barriuso, E.V.-G.; Roberto Pastor-Barriuso, E.V.-G.; de Pedro-Cuesta, J. Factors associated with falls among older adults living in institutions. BMC Geriatr. 2013, 13, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guoqing, S.; Kun, D.; Hao, C.; Jingwei, X. A Study of Fall Risk Assessment in the Elderly. In Proceedings of the 2020 9th International Conference on Applied Science, Engineering and Technology (ICASET 2020), Chennai, India, 16–17 May 2020; pp. 176–183. [Google Scholar]

- Kalula, S.; Ferreira, M.; Swingler, G.H.; Badri, M.; Sayer, A.A. Methodological challenges in a study on falls in an older population of cape town, South Africa. Afr. Health Sci. 2017, 17, 912–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics South Africa. Mid-Year Population Estimates. 2022. Available online: https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0302/P03022022.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- Aboderin, I. Understanding and advancing the health of older populations in sub-Saharan Africa: Policy perspectives and evidence needs. Public Health Rev. 2011, 33, 357–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, G.; Mrengqwa, L.; Geffen, L. “they don’t care about us”: Older people’s experiences of primary healthcare in Cape Town, South Africa. BMC Geriatr. 2019, 19, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraix, M. Role of the musculoskeletal system and the prevention of falls. J. Am. Osteopath. Assoc. 2012, 112, 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Iamtrakul, P.; Chayphong, S.; Jomnonkwao, S.; Ratanavaraha, V. The association of falls risk in older adults and their living environment: A case study of rural area, Thailand. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, R.S.; Al-daour, D.S. Falls in the Elderly: Assessment of Prevalence and Risk Factors. Pharm. Pract. 2018, 16, 1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kioh, S.H.; Rashid, A. The prevalence and the risk of falls among institutionalised elderly in penang, malaysia. Med. J. Malays. 2018, 73, 212–219. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health Victoria. Falls Risk Assessment Tool (FRAT) Victoria. 2015. Available online: https://www.health.vic.gov.au/publications/falls-risk-assessment-tool-frat (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Stapelton, C.; Hough, P.; Oldmeadow, L.; Bull, K.; Hill, K.; Greenwood, K. Innovations in Aged Care. Four-item fall risk screening tool for subacute and residential aged care: The first step in fall prevention. Australas. J. Ageing 2009, 28, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almegbel, F.Y.; Alotaibi, I.M.; Alhusain, F.A.; Masuadi, E.M.; Al Sulami, S.L.; Aloushan, A.F.; Almuqbil, B.I. Period prevalence, risk factors and consequent injuries of falling among the Saudi elderly living in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e019063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Firpo, G.; Duca, D.; Ledur Antes, D.; Curi, P.; Ii, H. Quedas e fraturas entre residentes de instituições de longa permanência para idosos Falls and fractures among older adults living in long-term care. Rev. Bras. Epidemiol. 2013, 16, 68–76. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Zeng, Y.; Weng, C.; Yan, J.; Fang, Y. Epidemiological characteristics and factors influencing falls among elderly adults in long-term care facilities in Xiamen, China. Medicine 2019, 98, e14375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orces, C.H. Prevalence and determinants of falls among older adults in ecuador: An analysis of the SABE i survey. Curr. Gerontol. Geriatr. Res. 2013, 2013, 495468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, C.R.; Cooper, C.; Sayer, A.A. Prevalence and risk factors for falls in older men and women: The English longitudinal study of ageing. Age Ageing 2016, 45, 789–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salari, N.; Darvishi, N.; Ahmadipanah, M.; Shohaimi, S.; Mohammadi, M. Global prevalence of falls in the older adults: A comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2022, 17, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imaginário, C.; Martins, T.; Araújo, F.; Rocha, M.; MacHado, P.P. Risk Factors Associated with Falls among Nursing Home Residents: A Case-Control Study. Port. J. Public Health 2021, 39, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustavsson, J.; Jernbro, C.; Nilson, F. There is more to life than risk avoidance—Elderly people’s experiences of falls, fall-injuries and compliant flooring. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2018, 13, 1479586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhargave, P.; Sendhilkumar, R. Prevalence of risk factors for falls among elderly people living in long-term care homes. J. Clin. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2016, 7, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazi, H.F.; Elnajeh, M.; Abdalqader, M.A.; Baobaid, M.F.; Rahimah Rosli, N.S.; Syahiman, N. The prevalence of falls and its associated factors among elderly living in old folks home in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Int. J. Community Med. Public Health 2017, 4, 3524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satariano, W.A. The Ecological Model in the Context of Aging Populations: A Portfolio of Interventions. Jasp 2010, 1–20. Available online: https://www.inspq.qc.ca/sites/default/files/jasp/archives/2010/WilliamSatariano.pdf (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- Castaldo, A.; Giordano, A.; Antonelli Incalzi, R.; Lusignani, M. Risk factors associated with accidental falls among Italian nursing home residents: A longitudinal study (FRAILS). Geriatr. Nurs. 2020, 41, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cumming, R.G.; Salkeld, G.; Thomas, M.; Szonyi, G. Prospective Study of the Impact of Fear of Falling on Activities of Daily Living, SF-36 Scores, and Nursing Home Admission. J. Gerontol. Med. Sci. 2000, 55, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tolson, D.; Morley, J.E. Medical Care in the Nursing Home. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2011, 95, 595–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callis, N. Falls prevention: Identification of predictive fall risk factors. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2016, 29, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deandrea, S.; Bravi, F.; Turati, F.; Lucenteforte, E.; La Vecchia, C.; Negri, E. Risk factors for falls in older people in nursing homes and hospitals. A Syst. Rev. Meta-Analysis. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2013, 56, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubenstein, L.Z. Falls in older people: Epidemiology, risk factors and strategies for prevention. Age Ageing 2006, 35 (Suppl. S2), 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.S.; Kowal, P.; Hestekin, H.; Driscoll, T.O.; Peltzer, K.; Yawson, A. Prevalence, risk factors and disability associated with fall-related injury in older adults in low- and middle-incomecountries: Results from the WHO Study on global AGEing and adult health (SAGE). BMC Med. 2015, 13, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.T.; Abd Elltef, M.A.B.; Miky, S.F. Prevention Program Regarding Falls among Older Adults at Geriatrics Homes. Evid.-Based Nurs. Res. 2020, 2, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapp, K.; Becker, C.; Cameron, I.D.; König, H.-H.; Büchele, G. Epidemiology of falls in residential aged care: Analysis of more than 70,000 falls from residents of bavarian nursing homes. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2012, 13, 187.e1-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, L.; Shi, Y.; Xie, X.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, J. Incidence and Risk Factors of Falls Among Older People in Nursing Homes: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2023, 24, 1708–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, B.; Pecanac, K.; Krupp, A.; Liebzeit, D.; Mahoney, J. Impact of Fall Prevention on Nurses and Care of Fall Risk Patients. Gerontologist 2018, 58, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizka, A.; Indrarespati, A.; Dwimartutie, N.; Muhadi, M. Frailty among older adults living in nursing homes in indonesia: Prevalence and associated factors. Ann. Geriatr. Med. Res. 2021, 25, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, R.; Ashwell, A.; Docrat, S.; Schneider STRiDE South Africa, M.; Candidate, M.; Schneider, M. The Impact of COVID-19 on Long-Term Care Facilities in South Africa with a Specific Focus on Dementia Care. 2020. Available online: https://ltccovid.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/COVID-19-Long-Term-Care-Situation-in-South-Africa-10-July-2020.pdf (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- Wen, Y.; Liao, J.; Yin, Y.; Liu, C.; Gong, R.; Wu, D. Risk of falls in 4 years of follow-up among Chinese adults with diabetes: Findings from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e043349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu, H.C.D.A.; Reiners, A.A.O.; Azevedo, R.C.D.S.; da Silva, A.M.C.; Abreu, D.R.d.O.M.; de Oliveira, A.D. Incidence and predicting factors of falls of older inpatients. Rev. Saude Publica 2015, 49, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloch, F.; Thibaud, M.; Dugué, B.; Brèque, C.; Rigaud, A.S.; Kemoun, G. Episodes of falling among elderly people: A systematic review and meta-analysis of social and demographic pre-disposing characteristics. Clinics 2010, 65, 895–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, D.; Springer, K.W. Advances in families and health research in the 21st century. J. Marriage Fam. 2010, 72, 743–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, E.A.; Chinogurei, C.; Adams, L. Marital experiences and depressive symptoms among older adults in rural South Africa. SSM Ment. Health 2022, 2, 100083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics South Africa. Census 2011: Profile of Older Persons in South Africa. 2014. Available online: http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/Report-03-01-60/Report-03-01-602011.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Costa-Dias, M.J.; Oliveira, A.S.; Martins, T.; Araújo, F.; Santos, A.S.; Moreira, C.N.; José, H. Medication fall risk in old hospitalized patients: A retrospective study. Nurse Educ. Today 2014, 34, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obayashi, K.; Araki, T.; Nakamura, K.; Kurabayashi, M.; Nojima, Y.; Hara, K.; Nakamura, T.; Yamamoto, K. Risk of falling and hypnotic drugs: Retrospective study of inpatients. Drugs R D 2013, 13, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalula, S.Z.; Ferreira, M.; Swingler, G.H.; Badri, M. Risk factors for falls in older adults in a South African Urban Community. BMC Geriatr. 2016, 16, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Wolf, I.K.; Knopf, H. Association of psychotropic drug use with falls among older adults in Germany. Results of the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Adults 2008-2011 (DEGS1). PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0182432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, K.D.; Wee, R. Psychotropic drug-induced falls in older people: A review of interventions aimed at reducing the problem. Drugs Aging 2012, 29, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mapira, L.; Kelly, G.; Geffen, L.N. A qualitative examination of policy and structural factors driving care workers’ adverse experiences in long-term residential care facilities for the older adults in Cape Town. BMC Geriatr. 2019, 19, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahim, N. The Determinants of Falls Among the Elderly Living in Long-Term Care Facilities in the City of Cape Town. Master’s Thesis, University of the Western Cape, Cape Town, South Africa, 2023. [Google Scholar]

| Category | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 74 (28.7) |

| Female | 184 (71.3) |

| Total | 258 (100) |

| Age (years) | |

| 60–69 | 34 (13.2) |

| 70–79 | 103 (39.9) |

| 80–89 | 111 (43.0) |

| ≥90 | 10 (3.9) |

| Total | 258 (100) |

| Obesity (kg/m2) | |

| Underweight | 10 (3.9) |

| Normal | 113 (43.8) |

| Overweight | 87 (33.7) |

| Obese | 48 (18.6) |

| Educational Level | |

| Grade 7 or lower | 32 (12.4) |

| Grades 8–11 | 43 (16.7) |

| Matriculated from mainstream school | 79 (30.6) |

| Matriculated from technical school | 51 (19.8) |

| Graduated with a bachelor’s degree | 42 (16.3) |

| Graduated with a master’s degree | 6 (2.3) |

| Graduated with a doctoral degree | 5 (1.9) |

| Total | 258 (100) |

| Marital Status | |

| Married | 63 (24.4) |

| Single | 44 (17.1) |

| Divorced | 39 (15.1) |

| Widowed | 112 (43.4) |

| Total | 258 (100) |

| Fall History | |

| No | 67.4 (174) |

| Yes | 32.6 (84) |

| Total | 258 (100) |

| Fall Mechanisms | |

| Slipping/tripping | 40 (15.5) |

| Loss of balance | 27 (10.5) |

| Collapse | 9 (3.5) |

| Legs give way | 2 (0.8) |

| Dizziness | 13 (5.0) |

| Total | 258 (100) |

| Variable | Category | Falls n (%) | p-Value | X2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||||

| Facility type | Non-profit organization | 58 (39.4) | 89 (55.1) | 0.007 * | 7.403 |

| Private | 26 (23.4) | 85 (80.1) | |||

| Gender | Male | 23 (31.0) | 51 (68.9) | 0.748 | 0.103 |

| Female | 61 (33.1) | 123 (66.8) | |||

| Age (years) | 60–69 | 12 (35.2) | 22 (64.7) | 0.806 | 0.982 |

| 70–79 | 35 (33.9) | 68 (66.0) | |||

| 80–89 | 35 (31.5) | 76 (68.4) | |||

| ≥90 | 2 (20) | 8 (80) | |||

| Educational level | Junior school or lower | 19 (59.3) | 13 (40.6) | 0.029 * | 14.05 |

| Some high school, did not graduate | 11 (25.5) | 32 (74.4) | |||

| Matriculated from mainstream school | 24 (30.3) | 55 (69.6) | |||

| Technical school | 12 (23.5) | 39 (76.4) | |||

| Bachelor’s degree | 15 (35.7) | 27 (64.2) | |||

| Master’s degree | 2 (33.3) | 4 (66.6) | |||

| Doctoral degree | 1 (20) | 4 (80) | |||

| Marital status | Married | 16 (25.3) | 47 (74.6) | 0.001 * | 16.49 |

| Single | 20 (45.4) | 24 (54.5) | |||

| Divorced | 21 (53.8) | 18 (46.1) | |||

| Widowed | 27 (24.1) | 85 (75.8) | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ebrahim, N.; Ras, J.; November, R.; Leach, L. The Prevalence of Falls Among Older Adults Living in Long-Term Care Facilities in the City of Cape Town. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 432. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22030432

Ebrahim N, Ras J, November R, Leach L. The Prevalence of Falls Among Older Adults Living in Long-Term Care Facilities in the City of Cape Town. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(3):432. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22030432

Chicago/Turabian StyleEbrahim, Nabilah, Jaron Ras, Rucia November, and Lloyd Leach. 2025. "The Prevalence of Falls Among Older Adults Living in Long-Term Care Facilities in the City of Cape Town" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 3: 432. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22030432

APA StyleEbrahim, N., Ras, J., November, R., & Leach, L. (2025). The Prevalence of Falls Among Older Adults Living in Long-Term Care Facilities in the City of Cape Town. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(3), 432. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22030432