Oral Health and Hygiene Status of Global Transgender Population: A Living Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

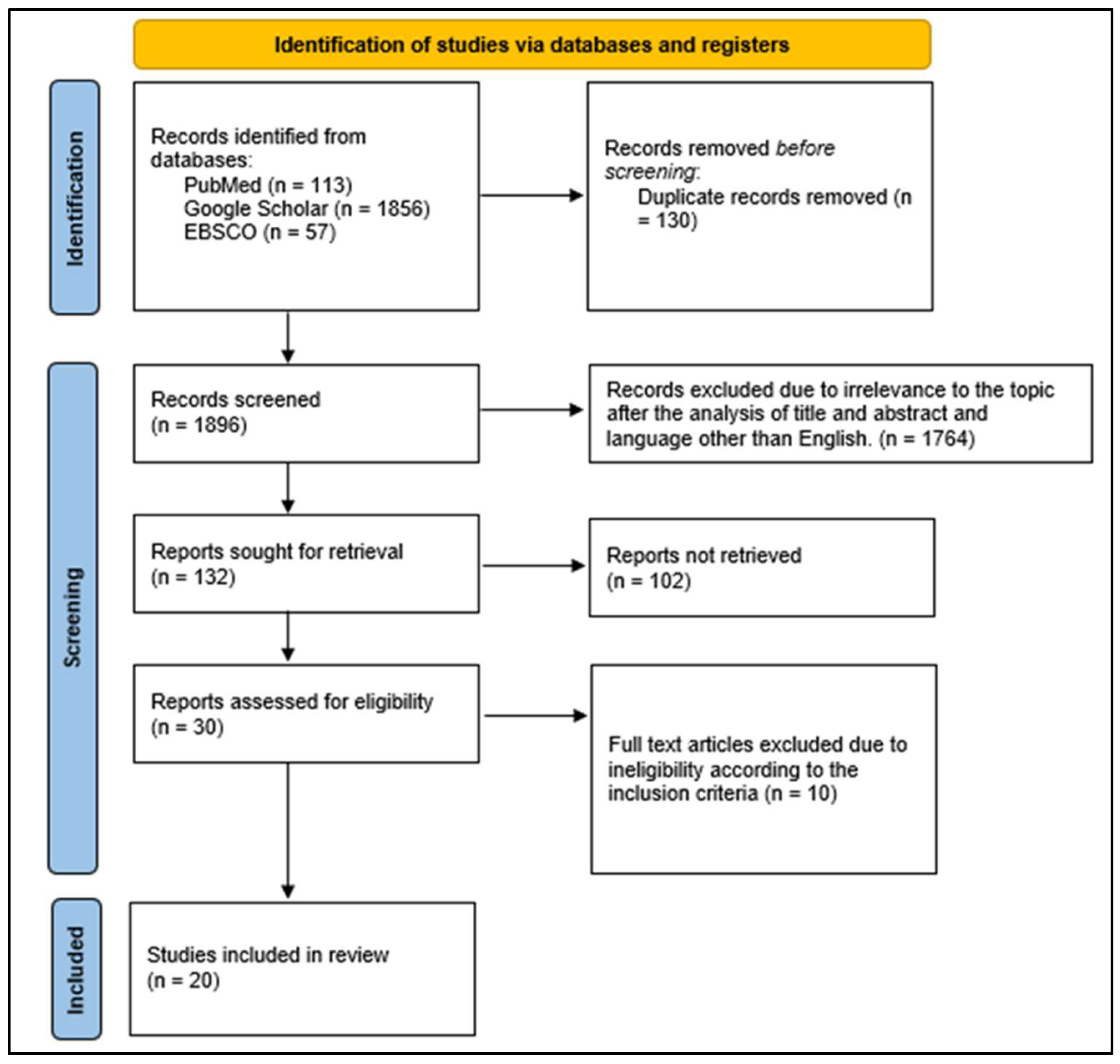

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Studies with Outdated or Inappropriate Terminology Such as ‘Eunuchs’

2.4. Mitigation Strategies to Address Terminology Concerns

- Standardization of Terminology in Data Synthesis: Regardless of the terminology used in the original studies, all extracted data were systematically categorized under standardized, inclusive terminology in our analysis and discussion.

- Transparent Reporting and Acknowledgment: We explicitly acknowledge that certain included studies employed outdated terminology and provided necessary clarifications to avoid misrepresentation or insensitivity.

- Sensitivity Review and Ethical Considerations: The manuscript has undergone a review to ensure that our synthesized findings use affirming and appropriate language in line with contemporary standards in transgender health research.

2.5. Search Databases

2.6. Data Extraction

- Identification of the study (article type; journal type; author; country of the study; language; publication year; host institution of the study);

- Methodological characteristics (study design; study objective; research question; sample characteristics, e.g., sample size, sex; age, statistical analysis);

- Main findings;

- Conclusions.

2.7. Quality Assessment

- Risk of Bias

2.8. Statistical Analysis

- Assessment of Heterogeneity

3. Results

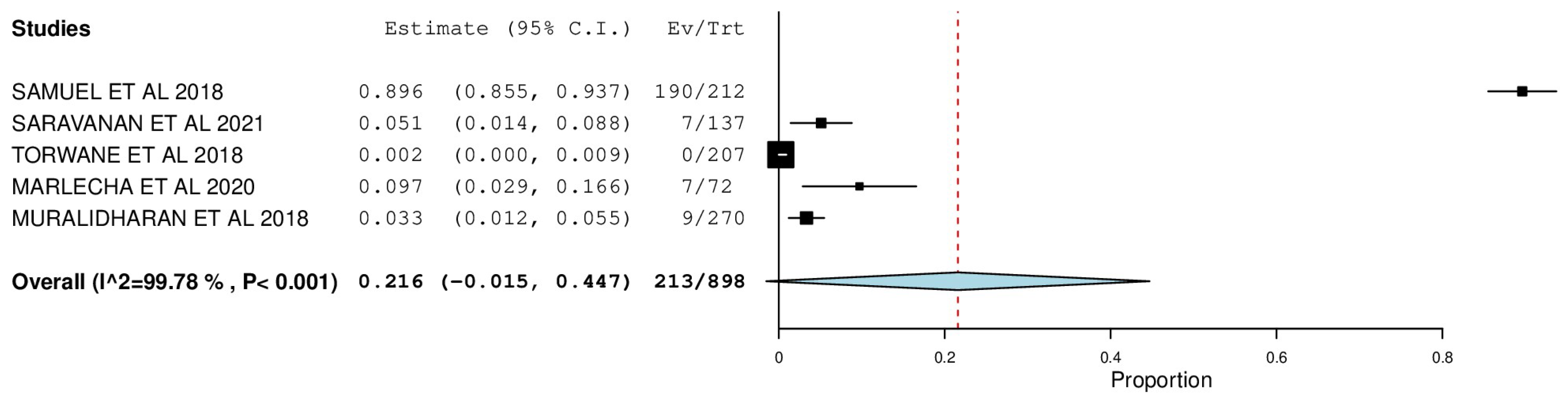

3.1. Oral Mucosal Lesions

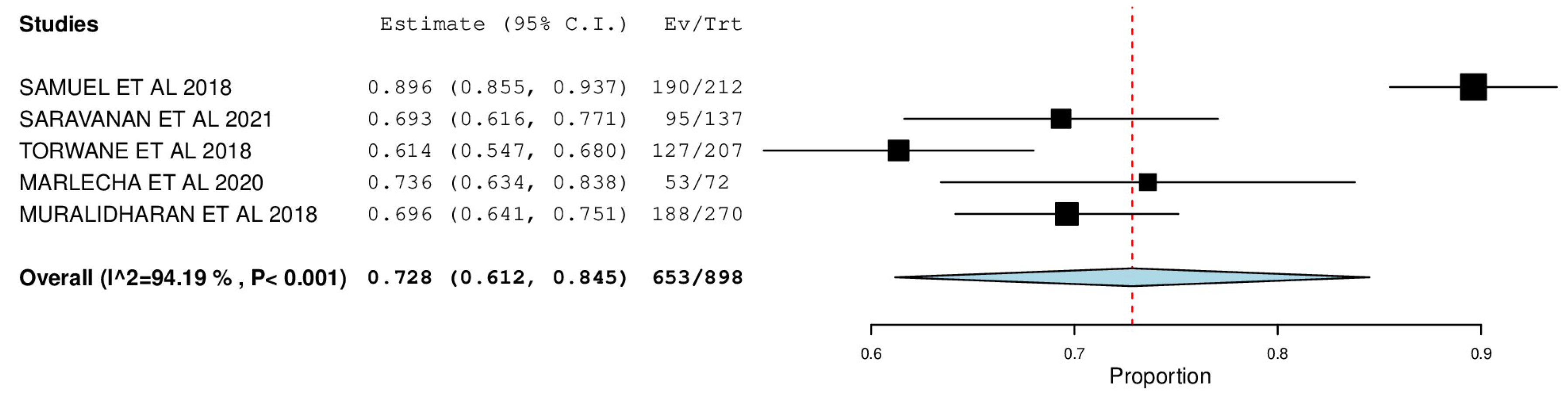

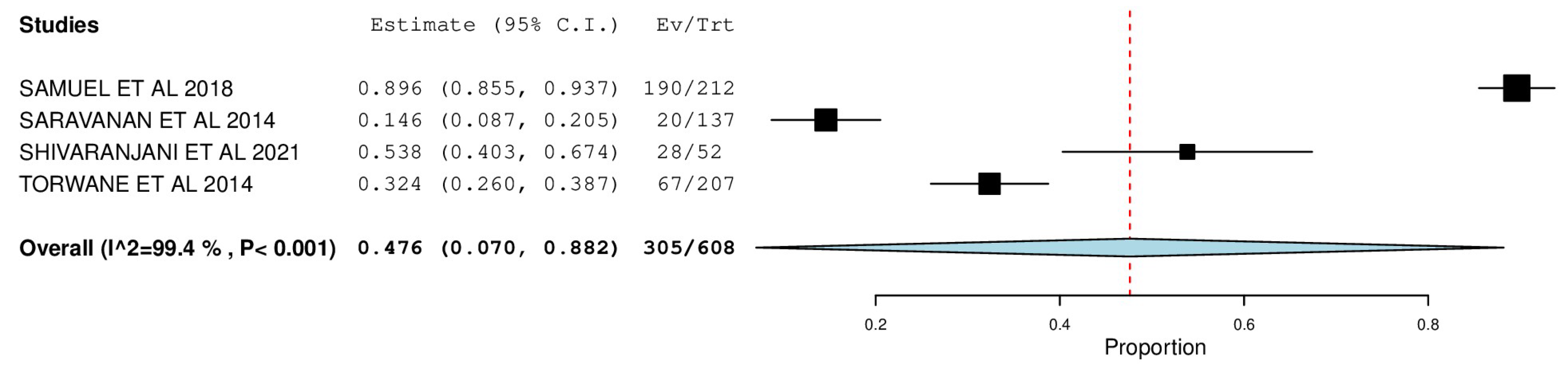

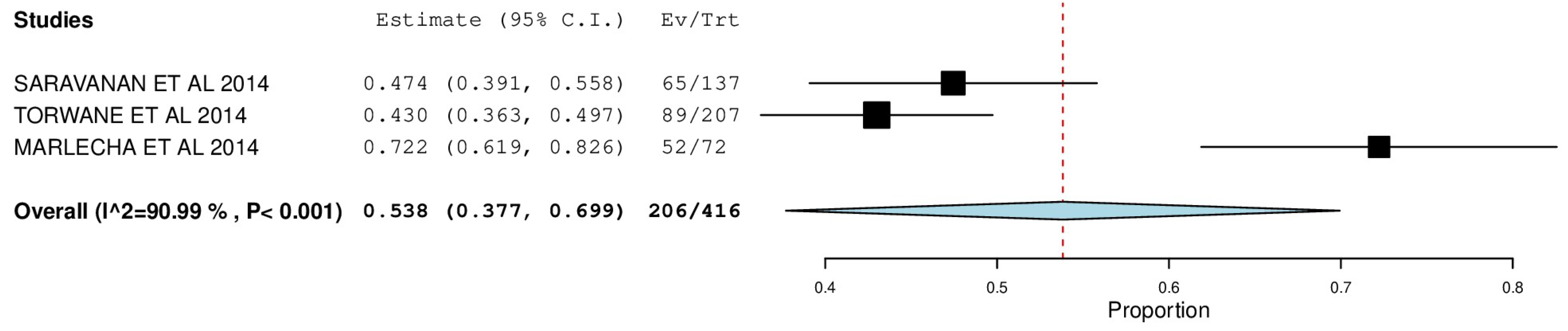

3.2. Periodontal Status

3.3. Dental Caries

3.4. Risk of Bias Assessment

- Expected Heterogenous Variability in Global Meta-Analyses

3.5. Diverse Study Designs and Populations

3.6. Variability in Oral Health Determinants

3.7. Statistical Handling of Heterogeneity

- Reporting Limitations and Data Constraints Regarding Subgroup Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Oral Health Disparities Between Transgender and Cisgender Populations

- Prevalence and General Trends

- Social Determinants of Health (SDOH) and Their Role in Oral Health Disparities

- Inclusion of Contextual Data from Existing Literature

4.1.1. Comparison of Dental Visit Frequency and Preventive Care Utilization

4.1.2. Specific Recommendations to Improve the Field

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bockting, W.O.; Miner, M.H.; Swinburne Romine, R.E.; Hamilton, A.; Coleman, E. Stigma, Mental Health, and Resilience in an Online Sample of the US Transgender Population. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103, 943–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheiham, A. Oral Health, General Health and Quality of Life. Bull. World Health Organ. 2005, 83, 644. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kumar, V.; Jain, R.; Singh, S. Kartavya: An Innovative Model to Deliver Oral Health Services to the Transgender Community in India. Spec. Care Dentist 2021, 41, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandya, A.K.; Redcay, A. Access to Health Services: Barriers Faced by the Transgender Population in India. J. Gay Lesbian Ment. Health 2021, 25, 132–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kass, N.E.; Faden, R.R.; Fox, R.; Dudley, J. Homosexual and Bisexual Men’s Perceptions of Discrimination in Health Services. Am. J. Public Health 1992, 82, 1277–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heima, M.; Heaton, L.J.; Ng, H.H.; Roccoforte, E.C. Dental Fear Among Transgender Individuals—A Cross-Sectional Survey. Spec. Care Dentist 2017, 37, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Group, T.P. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arjun, T.N.; Dayma, A.; Joshi, K.R.; Mishra, M.; Singh, V.R.; Khanal, L.R. Assessment of Dentition Status and Treatment Needs Among Eunuchs Residing in Bhopal City, Madhya Pradesh, India: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Int. J. Prev. Clin. Dent. Res. 2018, 5, S28–S34. [Google Scholar]

- Mohd, F.N.; Said, A.H.; Ali, A.; Draman, W.L.; Aznan, M.; Aris, M. Oral Health-Related Quality of Life Among Transgender Women in Malaysia. Alcohol 2022, 47, 47–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kalyan, P.; Dave, B.; Deshpande, N.; Panchal, D. A Study to Assess the Periodontal Status of Eunuchs Residing in Central Gujarat, India: A Cross-Sectional Study. Adv. Hum. Biol. 2020, 10, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravanan, N.; Thiruneervannan, R.; Christopher, P. A Study to Assess the Periodontal Status of Transgender in Chennai City. Biosci. Biotech. Res. 2014, 11, 1673–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeran, S.W.; Thiruneervannan, M.; Kumar, N.; Almarshoudi, S.; Ahmed, F.M. Oral Hygiene and Periodontal Status Among Eunuchs in Chennai, India. EC Dent. Sci. 2017, 15, 123–126. [Google Scholar]

- Prasanth, B.K.; Mahalakshmi, K.; Umadevi, R.; Kalpana, S.; Anantha, V.M. Knowledge on Oral Hygiene Practices and Assessment of Oral Health Status Among Transgender Community Residing in Chennai Metropolitan City—A Descriptive Cross-Sectional Study. Eur. J. Mol. Clin. Med. 2020, 7, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, G.; Sethi, A.K.; Bagchi, A.; Rai, S.; Tamilselvan, P. Knowledge, Attitudes and Behaviour Towards Oral Hygiene of Transgenders in Bhubaneswar During COVID-19. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2021, 10, 1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hongal, S.; Torwane, N.A.; Goel, P.; Byarakele, C.; Mishra, P.; Jain, S. Oral Health-Related Knowledge, Attitude and Practices Among Eunuchs (Hijras) Residing in Bhopal City, Madhya Pradesh, India: A Cross-Sectional Questionnaire Survey. J. Indian Soc. Periodontol. 2014, 18, 624. [Google Scholar]

- Muralidharan, S.; Acharya, A.; Koshy, A.V.; Koshy, J.A.; Yogesh, T.L.; Khire, B. Dentition Status and Treatment Needs and Its Correlation with Oral Health-Related Quality of Life Among Men Having Sex with Men and Transgenders in Pune City: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Oral Maxillofac. Pathol. 2018, 22, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravanan, N.; Reddy, C.V.; Veeresh, D.J. A Study to Assess the Oral Health Status and Treatment Needs of Eunuchs in Chennai City. J. Indian Assoc. Public Health Dent. 2006, 4, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivaranjani, K.; Pratebha, B.; Muthu, J.; Saravanakumar, R.; Karthikeyan, I. Change in Periodontal Status, Oral Health Knowledge, Attitude, and Practices Following Video-Based Counseling: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Mahatma Gandhi Inst. Med. Sci. 2021, 26, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovia, M.; Revathi, D.; Ganapathty, D. Oral Hygiene in Transgender of Chennai City. Drug Invent. Today 2019, 11, 235–240. [Google Scholar]

- Marlecha, R.; Mary, V.; An, K.; Christopher, P.; Nagavalli, K.; Salam, H. Oral Health Status, Dental Awareness, and Dental Services Utilization Barriers Among Transgender Population in Chennai. Drug Invent. Today 2020, 14, 1143–1148. [Google Scholar]

- Adekugbe, O.C. Oral Health Status and Dental Service Utilization of Persons Who Identify as Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer in Iowa City. ProQuest Diss. Publ. 2020, 28030187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, S.R.; Muragaboopathy, V.; Patil, S. Transgender HIV Status, Self-Perceived Dental Care Barriers, and Residents’ Stigma, Willingness to Treat Them in a Community Dental Outreach Program: Cross-Sectional Study. Spec. Care Dentist 2018, 38, 307–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivaranjani, K.; Balu, P.; Kumar, R.S.; Muthu, J.; Devi, S.S.; Priyadharshini, V. Correlation of Periodontal Status with Perceived Stress Scale Score and Cortisol Levels Among Transgenders in Puducherry and Cuddalore. SRM J. Res. Dent. Sci. 2020, 11, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, E.; Chandrashekhar, B.R.; Hongal, S.; Torwane, N.; Goel, P.; Mishra, P. A Study of the Palatal Rugae Pattern Among Male, Female, and Transgender Population of Bhopal City. J. Forensic Dent. Sci. 2015, 7, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torwane, N.A.; Hongal, S.; Goel, P.; Chandrashekar, B.; Saxena, V. Assessment of Oral Mucosal Lesions Among Eunuchs Residing in Bhopal City, Madhya Pradesh, India: A Cross-Sectional Study. Indian J. Public Health 2015, 59, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasanth, B.K.; Mahalakshmi, K.; Umadevi, R.; Kalpana, S.; Anantha Eashwar, V.M. Assessment of Micronuclei in the Exfoliated Buccal Mucosal Cells Based on the Personnel Behavior Among the Transgender Population of Tamil Nadu. Ann. Rom. Soc. Cell Biol. 2021, 25, 4307–4313. [Google Scholar]

- Torwane, N.; Hongal, S.; Saxena, E.; Rana, P.; Jain, S.; Gouraha, A. Assessment of Periodontal Status Among Eunuchs Residing in Bhopal City, Madhya Pradesh, India: A Cross-Sectional Study. Oral Health Dent. Manag. 2014, 13, 628–633. [Google Scholar]

- Żyła, T.; Kawala, B.; Antoszewska-Smith, J.; Kawala, M. Black Stain and Dental Caries: A Review of the Literature. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 469392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, S.J. Health Care of Sexual Minority Women. Nurs. Clin. North Am. 2018, 53, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheit, T.; Rollo, F.; Brancaccio, R.N.; Robitaille, A.; Galati, L.; Giuliani, M.; Latini, A.; Pichi, B.; Benevolo, M.; Cuenin, C.; et al. Oral Infection by Mucosal and Cutaneous Human Papillomaviruses in Men Who Have Sex with Men from the OHMAR Study. Viruses 2020, 12, 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauth, M.R.; Barrera, T.L.; Denton, F.N.; Latini, D.M. Health Differences Among Lesbian, Gay, and Transgender Veterans by Rural/Small Town and Suburban/Urban Setting. LGBT Health 2017, 4, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Shammari, K.F.; Al-Ansari, J.M.; Al-Khabbaz, A.K.; Dashti, A.; Honkala, E.J. Self-Reported Oral Hygiene Habits and Oral Health Problems of Kuwaiti Adults. Med. Princ. Pract. 2007, 16, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segal, N.L. Performing Together: Monozygotic Twin Comedians/Twin Research: Mirror-Image Cleft Lip and Palate; Dental Caries; Noninvasive Prenatal Testing; Capgras Syndrome with Folie à Deux/In the News: Athletic Twins; Transgendered Twins; Crib-Sharing; Common Careers. Twin Res. Hum. Genet. 2019, 22, 70–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, D.W.; Grossoehme, D.H.; Mazzola, A.; Pestian, T.; Schwartz, S.B. Transgender Youth and Oral Health: A Qualitative Study. J. LGBT Youth 2020, 17, 92–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, S.; More, F. Addressing Health Disparities via Coordination of Care and Interprofessional Education: Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health and Oral Health Care. Dent. Clin. North Am. 2016, 60, 891–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parish, C.L.; Santella, A.J. A Qualitative Study of Rapid HIV Testing and Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Competency in the Oral Health Setting: Practices and Attitudes of New York State Dental Directors. Oral Health Prev. Dent. 2018, 16, 343–350. [Google Scholar]

- Coulter, R.W.S.; Kenst, K.S.; Bowen, D.J. Research Funded by the National Institutes of Health on the Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Populations. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, e105–e112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, A.; Stronks, K.; Tromp, N.; Bhopal, R.; Zaninotto, P.; Unwin, N.; Nazroo, J.; Kunst, A. A Cross-National Comparative Study of Smoking Prevalence and Cessation Between English and Dutch South Asian and African Origin Populations: The Role of National Context. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2010, 12, 557–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangi, J.; Kinnunen, T.H.; Zavras, A.I. Challenges in Global Improvement of Oral Cancer Outcomes: Findings from Rural Northern India. Tob. Induc. Dis. 2012, 10, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, K.; Mehrotra, M.; Kumar, P.; Gogia, A.R.; Prasad, A.; Fisher, J.A. Smoke Inhalation Injury: Etiopathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Management. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 22, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, M.G.; Takei, H.; Carranza, F.A. (Eds.) Clinical Periodontology, 9th ed.; WB Saunders Company: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2002; pp. 245–252. [Google Scholar]

- Kotronia, E.; Brown, H.; Papacosta, A.O.; Lennon, L.T.; Weyant, R.J.; Whincup, P.H.; Wannamethee, S.G.; Ramsay, S.E. Oral Health and All-Cause, Cardiovascular Disease, and Respiratory Mortality in Older People in the UK and USA. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 16452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gianos, E.; Jackson, E.A.; Tejpal, A.; Aspry, K.; O’Keefe, J.; Aggarwal, M.; Jain, A.; Itchhaporia, D.; Williams, K.; Batts, T.; et al. Oral Health and Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease: A Review. Am. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2021, 7, 100179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarasena, N.; Ekanayaka, A.N.; Herath, L.; Miyazaki, H. Tobacco Use and Oral Hygiene as Risk Indicators for Periodontitis. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2002, 30, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, S.; Malhotra, R.; Malhotra, R.; Kaur, H.; Battu, V.S.; Kaur, A. Oral Hygiene Status of Mentally and Physically Challenged Individuals Living in a Specialized Institution in Mohali, India. Indian J. Oral Sci. 2013, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, L.E.; Almeida, P.F.; Oliveira, V.D.; Mialhe, F.L. Oral Health-Related Quality of Life in the LGBTIQ+ Population: A Cross-Sectional Study. Braz. Oral Res. 2024, 38, e041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dysart-Gale, D. Cultural Sensitivity Beyond Ethnicity: A Universal Precautions Model. Int. J. Allied Health Sci. Pract. 2006, 4, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Manpreet, K.; Ajmal, M.B.; Raheel, S.A.; Saleem, M.C.; Mubeen, K.; Gaballah, K.; Kujan, O. Oral health status among transgender young adults: A cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health. 2021, 21, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| S. No | Author/ Year | Country | Number of Participants (N) | Parameters Assessed | Outcomes (Expressed as Percentages and/or Mean ± Standard Deviation) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Arjun et al. [8] | Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh, India | N = 207 | Visit to the dentist Dental facility availability Frequency of sugar intake DMFT 1 index Treatment needs | GENDER (%) Visit to the dentist—67 (32.4) Dental facility availability Government hospital—11 (5.3) Private clinic—173 (84) None—14 (6.8) Do not know—8 (3.9) Frequency of sugar intake Everyday—8 (3.9) Several times a week—30 (14.5) Once in a week—26 (12.6) Rarely—88 (42.5) Never—55 (26.6) D 2—127 (61.4) M 3—53 (25.6) F 4—0 DMFT total—139 (67.1) Treatment needs Fissure sealant—45 (21.7) One surface filling—122 (58.9) Two surface filling—40 (19.3) Pulp care and restoration—38 (18.4) Extraction—70 (33.8) Need for any other care—76 (36.7) |

| 2 | Farah et al. [9] | Terengganu state, Malaysia | N = 100 | Habits Discrimination during dental treatment Frequency of brushing teeth | N (%) Smoking status 52 (52.5) Alcohol consumption 11 (11.1) Discrimination during dental treatment 21 (21.9) Frequency of brushing teeth

|

| 3 | Kalyan et al. [10] | Central Gujarat | N = 384 | Periodontal pocket depth Clinical attachment loss Oral hygiene Habits | Mean value of Periodontal pocket depth—3.12 ± 0.89 Clinical attachment loss—2.88 ± 0.74 N (%) Cleaning of teeth with Toothbrush—302 (78.64) Finger/stick—82 (21.35) Material used for cleaning Toothpaste—381 (99.2) Others—03 (0.78) Habit Smokeless tobacco—142 (36.97) Smoking tobacco—44 (11.45) Both smoking and smokeless tobacco—198 (51.56) Frequency of tobacco Once a day—16 (4.16) Multiple times in a day—368 (9.37) |

| 4 | Saravanan et al. [11] | Chennai city | N = 137 | Oral Hygiene Habits Personal Habits Periodontal status | N (%) Oral Hygiene Habits a. Cleaning Toothbrush—86.1 Finger-11.7 Toothbrush & finger—11.8 Others—0.7 b. Materials Toothpaste—76.6 Tooth powder—16.8 Toothpaste & tooth powder—5.8 Others—0.8 Personal Habits Alcohol No—37.2, Yes—62.8 Gutka No—65.0, Yes—35.0 Tobacco No—70.1, Yes—29.9 Smoking No—93.4, Yes—6.6 Pan No—94.2, Yes—5.8 Periodontal status Healthy—27 Bleeding—8.8 Calculus—47.4 4–5 mm—12.4 6 mm—2.2 Excluded—2.2 |

| 5 | Syed et al. [12] | Chennai city | N = 165 | OHI 5 Calculus index Clinical attachment loss Pocket depth | Mean ± S.D OHI Index—2.69 ± 2.62 Calculus index—2 ± 2.35 Clinical attachment loss (CAL)—2.39 ± 0.490 Pocket depth (PD)—2.41 ± 0.4 |

| 6 | Prasanth et al. [13] | Kancheepuram district | N = 75 | OHI-S 6 Knowledge related to oral health | N (%) OHI—S Good—22.7 Fair—37.3 Poor—40 Cleaning of teeth Once in a week—14.7 Many times in a week—5.3 Once in a day—57.3 More than once a day—22.7 Material used to clean the teeth Toothpaste with brush—82.7 Tooth powder—13.3 Finger—4.0 Causes of dental caries Toothpaste without fluoride—56.0 Frequent use of sugar—29.3 Causes for bleeding during brushing Inadequate bruising—8.0 Don’t know—6.7 Natural physiological phenomenon—14.7 Periodontal disease—13.3 Brushing too hard—13.3 Systemic diseases—18.7 Don’t know—40.0 Measures that prevent oral diseases Application of fluoride—9.3 Tooth scaling—44.0 Don’t know—46.7 Systemic diseases that may be related to oral diseases Diabetic—13.3 Hypertension—12.0 Cancer—20.0 Other diseases—17.3 Don’t know—37.3 |

| 7 | Kumar et al. [14] | Bhubaneswar | N = 205 | Oral hygiene habits | N (%)- Rural/Urban Material used for cleaning the teeth Finger—14.3%/4.7% Neem—22.4%/8.4% Twig—27.6%/22.4% Tooth powder—13.3%/17.8% Toothpaste—13.3%/43% Brushing of teeth regularly Yes—87.8%/91.6% No—12.2%/9.4% Visit to the dentist Once—12.2%/25.2% Twice—3.1%/17.8% Never—81.6%/43.9% Other—3.1%/13.1% |

| 8 | Hongal et al. [15] | Bhopal City, Madhya Pradesh | N = 207 | Knowledge, Attitude, Practice regarding oral hygiene | N (%) KNOWLEDGE Good oral health can improve general health- Yes 168 (81.2), No 19 (9.2), Don’t know 20 (9.7) Main cause of tooth decay Sweet/wafers/biscuits/cakes—157 (75.8) Fresh fruit—7 (3.4) Raw vegetables—14 (6.8) Don’t know—29 (14) Tooth decay Tiny black spot in tooth—44 (21.3) Large hole in tooth—71 (34.3) Occurrence of pain—72 (34.8) Don’t know—20 (9.7) Cause of mouth cancer Usage of betel nut and betel quid—50 (24.2) Usage of tobacco—88 (42.5) Alcohol—21 (10.1) Don’t know—48 (23.2) ATTITUDE Condition of mouth Excellent—5 (2.4) Good—82 (39.6) Fair—38 (18.4) Poor—75 (36.2) Don’t know—7 (3.4) Ever visited a dentist for any problem Yes—67 (32.4) No—140 (67.6) Visit to dentist in last year Once—36 (17.4) Twice—4 (1.9) Three times—0 More than three times—1 (0.5) Not visited—166 (80.2) Would like to treat the deep painful decay by Root canal treatment—48 (23.2) Removal of teeth—107 (51.7) At present postpone the treatment—4 (1.9) Don’t know—48 (23.2) PRACTICES Cleaning of teeth with Toothbrush—176 (85) Finger—31 (15) Chew stick/neem stick—0 Others—0 Material use for cleaning of teeth Toothpaste/powder—205 (99) Charcoal—2 (1) Lime salt—0 Others—0 Frequency of brushing Once—181 (87.4) Twice—26 (12.6) After meal—0 Don’t know—0 Frequency of changing toothbrush 1–3 months—119 (57.5) 4–6 months—1 (0.5) 1 year and above—0 After wear—58 (20) Don’t know—29 (14) Use of any other oral hygiene aid Dental floss—4 (1.9) Inter-dental brush—0 Toothpick—27 (13) Mouth wash—1 (0.5) None—176 (86.3) Frequency of sugar intake Everyday—8 (3.9) Several times a week—30 (14.5) Once in a week—26 (12.6) Rarely—88 (42.5) Never—55 (26.6) Use of tobacco Smokeless tobacco—113 (54.6) Smoking tobacco—0 Both smokeless and smoking tobacco—74 (35.7) Total tobacco usage—187 (90.3) Frequency of tobacco usage Once in a day—6 (2.9) Many times a day—181 (87.4) Several times a week—0 |

| 9 | Muralidharan et al. [16] | Pune | N = 270 | DMFT 7 | MEAN ± SD DT 8 —4.6741 ± 4.39724 MT 9 —0.2667 ± 0.96558 FT 10 —0.1407 ± 1.32835 DMFT—5.0778 ± 4.81377 N (%) Type of treatment required Pit and fissure sealant—0 One surface filling—159 (58.9) Two surface filling—46 (17.0) Pulp care and restoration—71 (26.3) Extraction—56 (20.7) Prosthetic need—66 (24.2) |

| 10 | Saravanan et al. [17] | Chennai city | 137 participants | DMFT Sweet consumption Oral hygiene practices Dental visit Habits Oral mucosal lesions Periodontal status | Decayed teeth—69.3% Filled teeth—5.1% Missing teeth—23.4% Sweet consumption—83.2% Cleaning habits Toothbrush—86.1% Finger—11.7% Material used Toothpaste—76.6% Tooth powder—16.8% Dental visit—42.3% Personal habits Alcohol—62.8% Gutka—35% Tobacco—29.9% Smoking—6.6% Pan chewing—5.8% Oral mucosal lesions Candidiasis—13.9% Ulceration—12.4% Leukoplakia—1.5% OSMF—0.7% Lichen planus—0.7% Periodontal status Bleeding—8.8% Calculus—47.4% Pocket depth—14.6% Loss of attachment— 0–3 mm—83.2% 4–5 mm—12.4% 6–8 mm—2.2% |

| 11 | Shivaranjani et al. [18] | Puducherry | N = 52 | Knowledge, Attitude, Practice regarding oral health Periodontal pocket depth Clinical attachment loss Bleeding Marginal gingival index | N (%) Oral health knowledge—PRE/POST 1 Good oral health leads to good general health—85.2/100 2 Sweets as the main cause of dental caries—61.1/92.6 3 Tiny black spot in the tooth indicates dental caries—35.2/89 4 Removal of teeth as the treatment of painful decay—31.5/83.3 5 Vigorous brushing can cause tooth sensitivity—46.3/88.5 6 Tobacco usage causes mouth cancer—46.3/61.1 7 Dental facilities in their locality—5.6/100 Oral health attitude 8 Unaware of bad breath—25.9/11.1 9 Visited dentist—28.8/90.7 10 No dentist visit last year—61.1/0 Oral health practices 11 Increased frequency of sugar intake—57.9/51.9 12 Using toothbrush—81.5/90.7 13 Using toothpaste—91.4/94.4 14 Habit of brushing twice a day—18.5/55.6 15 Change toothbrush every 3 months—33.3/74.1 16 Use of oral hygiene aids—5.6/33.3 Pre/Post MGI 11 —1.72 ± 0.80 0.93 ± 0.9 Bleeding site—21.80 14.70 PPD 12 0—13/21 1—10/4 2—5/3 CAL 13 0—31.1/56.78 1—32.1/24.7 2—24.3/5.2 3—0.31/1.23 4—7.4/5.56 X—0.63/2.48 9—4.03/3.1 |

| 12 | Ovia et al. [19] | Chennai city | 100 | Oral hygiene | 78%—brush teeth everyday 57%—use toothpick regularly 87%—have dental caries 69%—bleeding gums |

| 13 | Marlecha et al. [20] | Chennai city | N = 72 | DMF 14, ROOT STUMPS, IMPACTED TEETH, ABRASION, ATTRITION, PLAQUE, CALCULUS, Loss of attachment, GINGIVAL INFLAMMATION, MALOCCLUSION | N (%) Without dental caries—26.4 With dental caries—73.6 Teeth missing due to dental caries—27.8 Filled teeth—9.7 Root stumps—29.2 Impacted teeth—15.3 Abrasion—44.4 Attrition—37.5 Presence of plaque—68.1 Presence of calculus—72.2 With gingival inflammation—38.9 With loss of attachment—40.3 Malocclusion findings Class 1—80.55 Class 2—12.50 Class 3—6.95 |

| 14 | Olayinka et al. [21] | IOWA city | N = 769 | The rate of oral HPV 15 was higher in gay and lesbian individuals (11.3%) relative to bisexual (8.6%) and heterosexual individuals (7.1%). There was a significant difference in self-reported oral health measures: bisexual and homosexual individuals had higher rates (40.9% and 35.8%, respectively) of self-reported fair/poor oral health compared to 27% in heterosexual individuals. Bisexual individuals were more likely to confront barriers to accessing dental care (30%) versus heterosexual adults (19%). Gay men reported a higher rate of a history of “bone loss around teeth” (35%) when compared to their heterosexual counterparts (11%). | |

| 15 | Samuel et al. [22] | South India | N = 212 | Periodontal Health: Pocket Depth Caries Experience: DMF 16 Lesions Tobacco use Previous dental visit Perceived Barriers HIV 17 Status | N (%) Periodontal Health Pocket Depth—190 Caries Experience Decayed Teeth—190 Missing teeth—190 Filled teeth—190 Lesions Candida—33 (17.3) Leukoplakia—5 (26) Lichen Planus—1 (0.5) Tobacco Pouch Keratosis—4 (2.1) Tobacco use—Yes—93.2, No—6.8 Form of Tobacco use Chewable—82.4 Smoked—0 Both—17.6 Previous dental visit—No—95.3, Yes—4.7 Perceived Barriers Non-Admittance—60.5 Economic—35.8 Others—3.7 Perceived OH Very poor—14.2 Poor—52.1 Neither—23.7 Good—8.4 Very good—1.6 N HIV Status—Yes—4, No—5, Don’t know—181 |

| 16 | Sivaranjani et al. [23] | Puducherry and Cuddalore | N = 75 | Periodontal pocket depth Clinical attachment loss | The mean PPD 18 and CAL 19 of participants were 4.06 ± 0.70 and 3.97 ± 0.68, respectively. The mean cortisol level was 6.02 ng/mL. A strong, positive correlation was observed between mean cortisol level and periodontal parameters assessed (probing depth and cortisol –r = 0.592, p = 0.000; clinical attachment loss and cortisol levels –r = 0.618, p = 0.000) |

| 17 | Saxena et al. [24] | Bhopal City, Madhya Pradesh | N = 48 | Palatal rugae pattern | mean ± SD Number of rugae—11.1 ± 2.1 Rugae length Primary—7.14 ± 1.44 Secondary—3.79 ± 2.37 Fragmentary—0.31 ± 0.71 Rugae shape Straight—0.35 ± 0.56 Curve—3.60 ± 2.05 Wavy—6.89 ± 1.47 Circular—0.00 ± 0.00 Rugae direction Forwardly directed—6.25 ± 1.80 Backwardly directed—3.68 ± 2.27 Perpendicular directed—0.66 ± 0.85 Unification of rugae Converging rugae—0.29 ± 0.61 Diverging rugae—0.37 ± 0.68 |

| 18 | Torwane et al. [25] | Bhopal City, Madhya Pradesh | N = 207 | Oral mucosal conditions | N (%) Oral Mucosal Condition No condition—148 Malignant tumor—1 (0.5) Leukoplakia—16 (7.7) Lichen planus—2 (1.0) Traumatic ulceration—12 (5.8) Abscess—6 (2.9) Other conditions OSMF 20—20 (10) Smoker’s Palate—0 Pouch Keratosis—2 (1) Burn—0 Total—59 (28.5) Total population—207 |

| 19 | Prasanth et al. [26] | Chennai city | N = 120 | Assessment of Micronuclei in the exfoliated Buccal Mucosal Cells | The mean age of the population was 29 ± 4.60 years. While comparing the mean micronuclei count, it was significantly less (mean 5.37 with SD 1.12) among those have the habit of only chewing tobacco or pan. But alcoholic and alcohol with tobacco cases had higher counts (mean 9.27 with SD 4.12 and 7.10 with SD 4.32, respectfully). |

| 20 | Torwane et al. [27] | Bhopal City, Madhya Pradesh | N = 207 | Periodontal Status Loss of Attachment | Periodontal Status Healthy—6.3% Bleeding—17.4% Calculus—43% Shallow pocket—22.7% Deep pocket—9.7% Loss of Attachment 0–3 mm—61.8% 4–5 mm—15.9% 6–8 mm—10.1% 9–11 mm—4.8% >12 mm—6.3% |

| S. No. | Study | Reason for Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tomasz Zyla et al. [28] | Literature Review |

| 2 | Roberts et al. [29] | Literature Review |

| 3 | Gheit et al. [30] | Not related to primary outcome |

| 4 | Michael R Kauth et al. [31] | Not related to primary outcome |

| 5 | Khalaf F Al-Shammari et al. [32] | Irrelevant study population |

| 6 | Segal et al. [33] | Review article |

| 7 | Macdonald [34] | Qualitative study |

| 8 | Russell et al. [35] | Literature Review |

| 9 | Parish et al. [36] | Qualitative study |

| 10 | Coulter et al. [37] | Literature Review |

| S. No. | Author (YR) | JOANNA BRIGGS Institute (JBI) Tool for Risk of Bias Assessment for Prevalent Studies | New Castle–Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | Total | % | Selection | Comparability | Outcome | ||

| 1 | Arjun et al. (2018) [8] | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 88.8 | *** | * | ** |

| 2 | Farah et al. (2020) [9] | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 88.8 | *** | NA | ** |

| 3 | Kalyan et al. (2021) [10] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 | 100 | *** | NA | ** |

| 4 | Saravanan et al. (2014) [11] | 1 | 0 | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 77.7 | ** | * | ** |

| 5 | Syed et al. (2017) [12] | 1 | 0 | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 77.7 | ** | * | ** |

| 6 | Prasanth et al. (2020) [13] | 1 | 1 | - | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 77.7 | ** | NA | ** |

| 7 | Kumar et al. (2021) [14] | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 88.8 | *** | * | ** |

| 8 | Hongal et al. [15] | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 88.8 | *** | * | ** |

| 9 | Muralidharan et al. [16] | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 88.8 | *** | NA | ** |

| 10 | Saravanan et al. [17] | 1 | 0 | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 77.7 | ** | * | ** |

| 11 | Shivaranjan et al. [18] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 | 100 | *** | NA | ** |

| 12 | Ovia et al. [19] | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 88.8 | *** | NA | ** |

| 13 | Marlecha et al. [20] | 1 | - | - | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 66.6 | ** | NA | ** |

| 14 | Olayinka et al. [21] | 1 | - | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 77.7 | ** | NA | ** |

| 15 | Samuel et al. [22] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 | 100 | *** | NA | ** |

| 16 | Sivaranjani et al. [23] | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 88.8 | *** | * | ** |

| 17 | Saxena et al. [24] | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 88.8 | *** | * | ** |

| 18 | Torwane et al. [25] | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 88.8 | *** | * | ** |

| 19 | Prasanth et al. [26] | 1 | 1 | - | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 77.7 | ** | * | ** |

| 20 | Torwane et al. [27] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 | 100 | *** | * | ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kumar, V.; Thakker, J.; Royal, A.; Bhanushali, N.; Baghdadi, Z.D. Oral Health and Hygiene Status of Global Transgender Population: A Living Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 433. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22030433

Kumar V, Thakker J, Royal A, Bhanushali N, Baghdadi ZD. Oral Health and Hygiene Status of Global Transgender Population: A Living Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(3):433. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22030433

Chicago/Turabian StyleKumar, Vaibhav, Jasleen Thakker, Abhishek Royal, Nikhil Bhanushali, and Ziad D. Baghdadi. 2025. "Oral Health and Hygiene Status of Global Transgender Population: A Living Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 3: 433. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22030433

APA StyleKumar, V., Thakker, J., Royal, A., Bhanushali, N., & Baghdadi, Z. D. (2025). Oral Health and Hygiene Status of Global Transgender Population: A Living Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(3), 433. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22030433