Mechanisms from Growth Mindset to Psychological Well-Being of Chinese Primary School Students: The Serial Mediating Role of Grit and Academic Self-Efficacy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. Growth Mindset and Psychological Well-Being

2.2. Grit as a Mediator Between Growth Mindset and Psychological Well-Being

2.3. Academic Self-Efficacy as a Mediator Between Growth Mindset and Psychological Well-Being

2.4. The Serial Mediation by Grit and Academic Self-Efficacy

2.5. The Current Study

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design and Approach

3.2. Participant and Procedures

3.3. Materials

3.3.1. Growth Mindset

3.3.2. Grit

3.3.3. Academic Self-Efficacy

3.3.4. Psychological Well-Being

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Common Method Bias Test

4.2. Normality and Multicollinearity Assumption Test

4.3. Validity and Reliability Testing

4.4. Statistical Description and Correlation Analysis

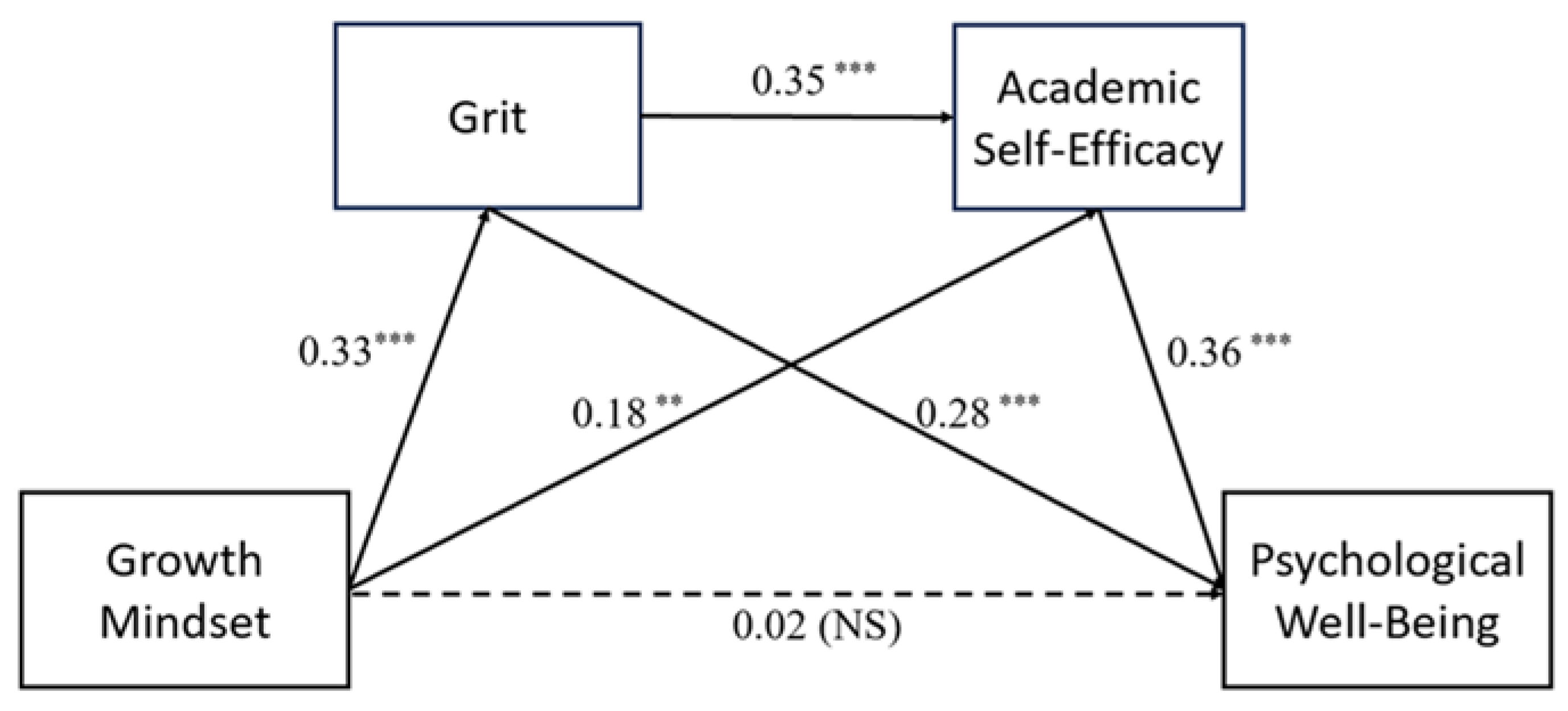

4.5. Hypotheses and Serial Mediation Model Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Correlations Between Growth Mindset and Psychological Well-Being

5.2. The Mediating Roles of Grit and Academic Self-Efficacy

5.3. Contributions and Implications

5.4. Limitations and Future Recommendations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GM | Growth mindset |

| ASE | Academic self-efficacy |

| PWB | Psychological well-being |

| SDT | Self-Determination Theory |

| CFA | Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

References

- Andales, R. C., Capuno, R. M., Cerbas, M. K., Mulit, J., Embradora, K. J., & Bacatan, J. (2025). Grit and resilience as predictors of psychological well-being among students. European Journal of Public Health Studies, 8(1), 98–102. [Google Scholar]

- Ariani, D. W. (2021). How achievement goals affect students’ well-being and the relationship model between achievement goals, academic self-efficacy and affect at school. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education, 14(1), 111–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aristotle. (350 BCE/1984). Nicomachean ethics. In J. Barnes (Ed.), The complete works of Aristotle: The revised Oxford translation (Vol. 2, pp. 1729–1867). Princeton University Press. (Original in 350 BCE). [Google Scholar]

- Azila-Gbettor, E. M., Mensah, C., Abiemo, M. K., & Bokor, M. (2021). Predicting student engagement from self-efficacy and autonomous motivation: A cross-sectional study. Cogent Education, 8(1), 1942638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W.H. Freeman and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Belsley, D. A., Kuh, E., & Welsch, R. E. (1980). Regression diagnostics: Identifying influential data and sources of collinearity. Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Benny, E. (2024). Examining the mediational role of self-efficacy in the relation between grit and well-being among non-traditional (working) university students in the UAE [Unpublished master’s thesis, United Arab Emirates University]. [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell, L. S., Trzesniewski, K. H., & Dweck, C. S. (2007). Implicit theories of intelligence predict achievement across an adolescent transition: A longitudinal study and an intervention. Child Development, 78(1), 246–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burnette, J. L., Billingsley, J., & Hoyt, C. L. (2022). Harnessing growth mindsets to help individuals flourish. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 16(3), e12657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnette, J. L., O’boyle, E. H., VanEpps, E. M., Pollack, J. M., & Finkel, E. J. (2013). Mind-sets matter: A meta-analytic review of implicit theories and self-regulation. Psychological Bulletin, 139(3), 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnette, J. L., Pollack, J. M., Forsyth, R. B., Hoyt, C. L., Babij, A. D., Thomas, F. N., & Coy, A. E. (2019). A Growth mindset intervention: Enhancing students’ entrepreneurial self-efficacy and career development. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 44, 878–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J., & Lian, R. (2022). Social support and a sense of purpose: The role of personal growth initiative and academic self-efficacy. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 788841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J. (2024, June 28–30). Analysis of the influence of different education models on the construction of students’ ability models in China. 2024 3rd International Conference on Science Education and Art Appreciation (SEAA 2024) (pp. 569–575), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, D. W., Sun, X., & Chan, L. K. (2022). Domain-specific growth mindsets and dimensions of psychological well-being among adolescents in Hong Kong. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 17(2), 1137–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L., Mak, M. C., Li, T., Wu, B. P., Chen, B. B., & Lu, H. J. (2011). Cultural adaptations to environmental variability: An evolutionary account of East–West differences. Educational Psychology Review, 23, 99–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemers, M. M., Hu, L., & Garcia, B. F. (2001). Academic self-efficacy and first year college student performance and adjustment. Journal of Educational Psychology, 93(1), 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X., & Lin, H. (2023). Mechanisms from academic stress to subjective well-being of Chinese adolescents: The roles of academic burnout and internet addiction. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 16, 4183–4196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, S., & Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98(2), 310–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. W. (2015). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research. Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, S. (2022). Comparison of normality tests in terms of sample sizes under different skewness and kurtosis coefficients. International Journal of Assessment Tools in Education, 9(2), 397–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derakhshan, A., & Fathi, J. (2024). Grit and foreign language enjoyment as predictors of EFL learners’ online engagement: The mediating role of online learning self-efficacy. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 33(4), 759–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, C., Zhou, W., & Huang, Z. (2020). The relationship between primary school students’ growth mindset, academic performance, and life satisfaction: The mediating role of academic self-efficacy. Studies of Psychology and Behavior, 18(4), 524–529. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95(3), 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E. (2000). Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. American Psychologist, 55(1), 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E. (2009). Assessing well-being: The collected works of Ed Diener (Vol. 39). Springer Science & Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E., Lucas, R. E., & Scollon, C. N. (2006). Beyond the hedonic treadmill: Revising the adaptation theory of well-being. American Psychologist, 61(4), 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, E., Wirtz, D., Tov, W., Kim-Prieto, C., Choi, D. W., Oishi, S., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2010). New well-being measures: Short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Social Indicators Research, 97, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y. Z., Kao, T. F., Fang, B. J., Shen, Y. C., & Cai, Q. Y. (2023, March 17–19). Study on the situation, prevention and strategy of learning anxiety in primary school students. 2023 2nd International Conference on Educational Innovation and Multimedia Technology (EIMT 2023) (pp. 1076–1082), Nanchang, China. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, W., & Xie, D. (2019). Measuring adolescent flourishing: Psychometric properties of flourishing scale in a sample of Chinese adolescents. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 37(1), 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duckworth, A. (2016). Grit: The power of passion and perseverance (Vol. 234). Scribner. [Google Scholar]

- Duckworth, A., & Gross, J. J. (2014). Self-control and grit: Related but separable determinants of success. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 23(5), 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duckworth, A. L., Peterson, C., Matthews, M. D., & Kelly, D. R. (2007). Grit: Perseverance and passion for long-term goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(6), 1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duckworth, A. L., & Quinn, P. D. (2009). Development and validation of the Short Grit Scale (GRIT–S). Journal of Personality Assessment, 91(2), 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duckworth, A. L., Quirk, A., Gallop, R., Hoyle, R. H., Kelly, D. R., & Matthews, M. D. (2019). Cognitive and noncognitive predictors of success. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(47), 23499–23504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, C. S. (1999). Self-theories: Their role in motivation, personality, and development. Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dweck, C. S. (2002). The development of ability conceptions. In Development of achievement motivation (pp. 57–88). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Dweck, C. S., Chiu, C. Y., & Hong, Y. Y. (1995). Implicit theories and their role in judgments and reactions: A word from two perspectives. Psychological Inquiry, 6(4), 267–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, C. S., & Leggett, E. L. (1988). A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychological Review, 95(2), 256–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. (2013). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics (4th ed.). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Fleurizard, T. A., & Young, P. R. (2018). Finding the right equation for success: An exploratory study on the effects of a growth mindset intervention on college students in remedial math. Journal of Counseling & Psychology, 2(1), 3. [Google Scholar]

- Garren, S. T., & Osborne, K. M. (2021). Robustness of t-test based on skewness and kurtosis. Journal of Advances in Mathematics and Computer Science, 36(2), 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- General Office of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China & General Office of the State Council. ((2021,, July 24)). Opinions on further reducing the homework and off-campus training burdens of students in compulsory education (Document No. 37). Available online: http://www.moe.gov.cn/jyb_xxgk/moe_1777/moe_1778/202107/t20210724_546576.html (accessed on 24 December 2024).

- Ghasemi, A., & Zahediasl, S. (2012). Normality tests for statistical analysis: A guide for non-statisticians. International Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism, 10(2), 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez-Lopez, M., Viejo, C., Romera, E. M., & Ortega-Ruiz, R. (2022). Psychological well-being and social competence during adolescence: Longitudinal association between the two phenomena. Child Indicators Research, 15(3), 1043–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, N., Khan, H., & Niwaz, A. (2021). Parenting styles out comes on psychological well-being of children. Rawal Medical Journal, 46(3), 652–655. [Google Scholar]

- Gülşen, F. U., & Şahin, E. E. (2023). Gender difference in the relationship between academic self-efficacy, personal growth initiative, and engagement among Turkish undergraduates: A multigroup modeling. Psychology in the Schools, 60(10), 3840–3857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W., Altalbe, A., Rehman, N., Rehman, S., & Sharma, S. (2024). Exploring the longitudinal impacts of academic stress and lifestyle factors among Chinese students. Journal of Pharmaceutical Policy and Practice, 17(1), 2398706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2012). PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling (White paper). Available online: http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (2nd ed.). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- He, J., Iskhar, S., Yang, Y., & Aisuluu, M. (2023). Exploring the relationship between teacher growth mindset, grit, mindfulness, and EFL teachers’ well-being. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1241335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X., Fang, S., & Du, L. (2023). Study on the relationship between self-efficacy and psychological well-being among Chinese college students. Studies in Psychological Science, 1(3), 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herdian, H., Chen, Q., & Nuryana, Z. (2023). Unlocking the power of growth mindset: Strategies for enhancing mental health and well-being among college students during COVID-19. Current Psychology, 43(19), 17956–17966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himmelberger, Z. M., Tibbetts, Y., Barron, K. E., Hulleman, C. S., Harootunian, G., & Speicher, M. R. (2024). How can a growth mindset-supportive learning environment in medical school promote student well-being? Families. Systems, & Health, 42(3), 343. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, Y., Chiu, C., Dweck, C. S., & Lin, D. (1999). Implicit theories, attributions, and coping: A meaning system approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(3), 588–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S., Liu, R., Zhen, R., Hong, W., & Jin, F. (2019). Relations between fixed mindset and engagement in math among high school students: Roles of academic self-efficacy and negative academic emotions. Psychological Development and Education, 35, 51–59. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M. S., & Park, S. (2021). Growth of fixed mindset from elementary to middle school: Its relationship with trajectories of academic behavior engagement and academic achievement. Psychology in the Schools, 58(11), 2175–2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. H., & Koh, T. S. (2014). Influence of psychological well-being and emotional expressiveness in middle school students on their peer relationships. Journal of the Korea Academia-Industrial Cooperation Society, 15(10), 6142–6149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, R. B., & Trinidad, J. E. (2021). Growth mindset predicts achievement only among rich students: Examining the interplay between mindset and socioeconomic status. Social Psychology of Education, 24(3), 635–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klainin-Yobas, P., Vongsirimas, N., Ramirez, D. Q., Sarmiento, J., & Fernandez, Z. (2021). Evaluating the relationships among stress, resilience and psychological well-being among young adults: A structural equation modelling approach. BMC Nursing, 20, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H. J., & Mendoza, N. B. (2025). Does parental support amplify growth mindset predictions for student achievement and persistence? Cross-cultural findings from 76 countries/regions. Social Psychology of Education, 28(1), 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. C. K., Yin, H., & Zhang, Z. (2010). Adaptation and analysis of motivated strategies for learning questionnaire in the Chinese setting. International Journal of Testing, 10(2), 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T., & Wang, J. (2024). Parents’ expectation, self-expectation, and test anxiety among primary school students in China: A moderated mediation model. Current Psychology, 43(38), 30359–30365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C. C. (2015). Validation of the psychological well-being scale for use in Taiwan. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 43(5), 867–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X., Fan, H., Shang, X., Li, W., He, X., Cao, P., & Ding, X. (2024). Parental involvement and children’s subjective well-being: Mediating roles of the sense of security and autonomous motivation in chinese primary school students. Behavioral Sciences, 14(7), 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Liu, H., & Zhang, P. (2021). Study on the relationship between growth mindset, grit and subjective well-being of adolescents. Journal of Jimei University (Natural Science), 22, 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Llorca, A., Cristina Richaud, M., & Malonda, E. (2017). Parenting, peer relationships, academic self-efficacy, and academic achievement: Direct and mediating effects. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lombas, A. S., García-Sancho, E., & Fuentes, M. C. (2019). Impact of the happy classrooms programme on psychological well-being, school aggression, and classroom climate: A randomized controlled trial. Mindfulness, 10(10), 1642–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H., Nie, P., & Sousa-Poza, A. (2021). The effect of parental educational expectations on adolescent subjective well-being and the moderating role of perceived academic pressure: Longitudinal evidence for China. Child Indicators Research, 14(1), 117–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z. G. ((2018,, January 19)). The survey shows that nearly 30% of Chinese primary school students spend more than two hours on homework every day. China Youth Daily. p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Luxia, Q. (2007). Is testing an efficient agent for pedagogical change? Examining the intended washback of the writing task in a high-stakes English test in China. Assessment in Education, 14(1), 51–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macnamara, B. N., & Burgoyne, A. P. (2023). Do growth mindset interventions impact students’ academic achievement? A systematic review and meta-analysis with recommendations for best practices. Psychological Bulletin, 149(3–4), 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, W. E., & Bridgmon, K. D. (2012). Quantitative and statistical research methods: From hypothesis to results. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Maslow, A. H. (1954). Motivation and personality. Harper & Brothers. [Google Scholar]

- McWilliams, E. C. (2014). Self-efficacy, implicit theory of intelligence, goal orientation and the ninth-grade experience [Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Northeastern University]. [Google Scholar]

- Meijerink, E. M., Aalderen-Smeets, S., & Molen, J. W. (2016). Set your mind! Effects of an intervention on mindset, self-efficacy, and intended STEM choice of students [Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Twente]. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, Q., & Zhang, Q. (2023). The influence of academic self-efficacy on university students’ academic performance: The mediating effect of academic engagement. Sustainability, 15(7), 5767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohtasham, S., Hatami Rad, S. S., Hormozi, A., Moodi Ghalibaf, A., & Mohammadi, Y. (2024). Academic self-efficacy and psychological well-being in medical students: A cross-sectional study. Canon Journal of Medicine, 4(3), 87–90. [Google Scholar]

- Molden, D. C., & Dweck, C. S. (2006). Finding “meaning” in psychology: A lay theories approach to self-regulation, social perception, and social development. American Psychologist, 61(3), 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosanya, M. (2021). Buffering academic stress during the COVID-19 pandemic related social isolation: Grit and growth mindset as protective factors against the impact of loneliness. International Journal of Applied Positive Psychology, 6(2), 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, M. B. (2020). The effect of learning environment towards psychological wellbeing and academic achievement of university students. PalArch’s Journal of Archaeology of Egypt/Egyptology, 17(9), 3113–3124. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, R. H. (1990). Classical and modern regression with applications (2nd ed.). PWS-Kent Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Nagaoka, J., Farrington, C. A., Ehrlich, S. B., & Heath, R. D. (2015). Foundations for young adult success: A developmental framework. Concept paper for research and practice. University of Chicago Consortium on Chicago School Research.

- Navarro-Carrillo, G., Alonso-Ferres, M., Moya, M., & Valor-Segura, I. (2020). Socioeconomic status and psychological well-being: Revisiting the role of subjective socioeconomic status. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, G., He, J., Lin, S., Sun, X., & Longobardi, C. (2020). Cyberbullying victimization and adolescent depression: The mediating role of psychological security and the moderating role of growth mindset. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(12), 4368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, D., Tsukayama, E., Yu, A., & Duckworth, A. L. (2020). The development of grit and growth mindset during adolescence. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 198, 104889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, D., Yu, A., Baelen, R. N., Tsukayama, E., & Duckworth, A. L. (2018). Fostering grit: Perceived school goal-structure predicts growth in grit and grades. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 55, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y. (2022, May 13–15). Parenting styles and self-acceptance of high school students: The mediating role of academic self-efficacy. 2022 International Conference on Science and Technology Ethics and Human Future (STEHF 2022) (pp. 39–43), Dali, China. [Google Scholar]

- Pintrich, P. R., & De Groot, E. V. (1990). Motivational and self-regulated learning components of classroom academic performance. Journal of Educational Psychology, 82(1), 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rammstedt, B., Grüning, D. J., & Lechner, C. M. (2024). Measuring growth mindset: Validation of a three-item and a single-item scale in adolescents and adults. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 40(1), 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohmah, I. A., Formen, A., & Saraswati, S. (2024). The effects of self-acceptance, coping strategies, and social support on psychological well-being. Jurnal Bimbingan Konseling, 13(1), 32–38. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(6), 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C. D., & Keyes, C. L. M. (1995). The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(4), 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabouripour, F., Roslan, S., Ghiami, Z., & Memon, M. A. (2021). Mediating role of self-efficacy in the relationship between optimism, psychological well-being, and resilience among Iranian students. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 675645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savvides, H., & Bond, C. (2021). How does growth mindset inform interventions in primary schools? A systematic literature review. Educational Psychology in Practice, 37(2), 134–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schunk, D. H. (1989). Self-efficacy and cognitive achievement: Implications for students with learning problems. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 22(1), 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schunk, D. H. (1991). Self-efficacy and academic motivation. Educational Psychologist, 26(3–4), 207–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M. E. (2011). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, R., & Deshpande, A. (2022). Relationship between psychological well-being, resilience, grit, and optimism among college students in Mumbai. Journal of Psychosocial Research, 17(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shek, D. T. (1997). Family environment and adolescent psychological well-being, school adjustment, and problem behavior: A pioneer study in a Chinese context. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 158(1), 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Si, T. P., Yoon, S. H., & Kim, H. R. (2022). A study on the relationship between grit and well-being with the mediation effect of self-efficacy: A case of general hospital nurses in South Korea. Journal of Digital Convergence, 20(5), 537–546. [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui, S. (2015). Impact of self-efficacy on psychological well-being among undergraduate students. The International Journal of Indian Psychology, 2(3), 5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Singhal, S., & Prakash, N. (2021). Relationship between self-esteem and psychological well-being among Indian college students. Journal of Interdisciplinary Cycle Research, 12, 748–756. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X., Nancekivell, S., Gelman, S. A., & Shah, P. (2021). Growth mindset and academic outcomes: A comparison of US and Chinese students. NPJ Science of Learning, 6(1), 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2019). Using multivariate statistics (7th ed.). Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Q., Zhang, L., Li, W., & Kong, F. (2021). Longitudinal measurement invariance of the flourishing scale in adolescents. Current Psychology, 40, 5672–5677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L., & Zhu, X. (2024). Academic self-efficacy, grit, and teacher support as predictors of psychological well-being of Chinese EFL students. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1332909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M., Wang, D., & Guerrien, A. (2020). A systematic review and meta-analysis on basic psychological need satisfaction, motivation, and well-being in later life: Contributions of self-determination theory. PsyCh Journal, 9(1), 5–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejada-Gallardo, C., Blasco-Belled, A., Torrelles-Nadal, C., & Alsinet, C. (2020). Effects of school-based multicomponent positive psychology interventions on well-being and distress in adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 49(10), 1943–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C., Boyanton, D., Ross, A. S. M., Liu, J. L., Sullivan, K., & Anh Do, K. (2018). School climate, victimization, and mental health outcomes among elementary school students in China. School Psychology International, 39(6), 587–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S., Dai, J., Li, J., Wang, X., Chen, T., Yang, X., He, M., & Gong, Q. (2018). Neuroanatomical correlates of grit: Growth mindset mediates the association between gray matter structure and trait grit in late adolescence. Human Brain Mapping, 39(4), 1688–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y., Wang, L., Yang, L., & Wang, W. (2024). Influence of perceived social support and academic self-efficacy on teacher-student relationships and learning engagement for enhanced didactical outcomes. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 28396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittington, R. E., Rhind, S., Loads, D., & Handel, I. (2017). Exploring the link between mindset and psychological well-being among veterinary students. Journal of Veterinary Medical Education, 44(1), 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, Z., Tan, S., Kang, Q., Zhang, B., & Zhu, L. (2019). Longitudinal effects of examination stress on psychological well-being and a possible mediating role of self-esteem in Chinese high school students. Journal of Happiness Studies, 20, 283–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J., Wang, H., Liu, S., Hale, M. E., Weng, X., Ahemaitijiang, N., Hu, Y., Suveg, C., & Han, Z. R. (2023). Relations among family, peer, and academic stress and adjustment in Chinese adolescents: A daily diary analysis. Developmental Psychology, 59(7), 1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y., & Wang, J. (2024). The mediating role of teaching enthusiasm in the relationship between mindfulness, growth mindset, and psychological well-being of Chinese EFL teachers. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 11(1), 1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P. (2021). Exploring the relationship between Chinese EFL students’ grit, well-being, and classroom enjoyment. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 762945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X. (2013). Senior secondary students’ perceptions of mathematics classroom learning environments in China and their attitudes towards mathematics. The Mathematics Educator, 15(1), 66–80. [Google Scholar]

- Yeager, D. S., & Dweck, C. S. (2012). Mindsets that promote resilience: When students believe that personal characteristics can be developed. Educational Psychologist, 47(4), 302–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeager, D. S., Hanselman, P., Walton, G. M., Murray, J. S., Crosnoe, R., Muller, C., Tipton, E., Schneider, B., Hulleman, C. S., Hinojosa, C. P., & Dweck, C. S. (2019). A national experiment reveals where a growth mindset improves achievement. Nature, 573(7774), 364–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C., Zhao, S., Jin, L., Wang, Y., & Lin, D. (2024). A single-session growth mindset intervention among Chinese junior secondary school students. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 16(4), 2397–2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J., Kreijkes, P., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2022). Students’ growth mindset: Relation to teacher beliefs, teaching practices, and school climate. Learning and Instruction, 80, 101616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, G., Hou, H., & Peng, K. (2016). Effect of growth mindset on school engagement and psychological well-being of Chinese primary and middle school students: The mediating role of resilience. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J., Liu, Y., & Cheong, C. M. (2024). The effect of growth mindset on motivation and strategy use in Hong Kong students’ integrated writing performance. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 39(3), 2915–2934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T., Park, D., Ungar, L. H., Tsukayama, E., Luo, L., & Duckworth, A. L. (2022). The development of grit and growth mindset in Chinese children. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 221, 105450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H., Zhang, M., Li, Y., & Wang, Z. (2023). The effect of growth mindset on adolescents’ meaning in life: The roles of self-efficacy and gratitude. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 16, 4647–4664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W., Shi, X., Jin, M., Li, Y., Liang, C., Ji, Y., Cao, J., Oubibi, M., Li, X., & Tian, Y. (2024). The impact of a growth mindset on high school students’ learning subjective well-being: The serial mediation role of achievement motivation and grit. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1399343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y., Niu, G., Hou, H., Zeng, G., Xu, L., Peng, K., & Yu, F. (2018). From growth mindset to grit in Chinese schools: The mediating roles of learning motivations. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y., Zhai, X., Zhang, G., Liang, X., & Xin, S. (2022). The relationship between growth mindset and grit: Serial mediation effects of the future time perspective and achievement motivation. Psychological Development and Education, 38(02), 216–222. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, B. J. (2000). Self-efficacy: An essential motive to learn. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 171 | 56.8 |

| Female | 130 | 43.2 | |

| Age | 9 | 108 | 35.9 |

| 10 | 153 | 50.8 | |

| 11 | 36 | 12.0 | |

| 12 | 4 | 1.3 | |

| Total | - | 301 | 100 |

| χ2 | df | χ2/df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | SRMR | α | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Growth Mindset | 0.722 | 2 | 0.361 | 1.000 | 1.018 | 0.000 [0.00–0.08] | 0.010 | 0.722 |

| Grit | 25.211 | 18 | 1.401 | 0.980 | 0.970 | 0.037 [0.00–0.07] | 0.043 | 0.707 |

| Academic Self-efficacy | 22.673 | 12 | 1.889 | 0.988 | 0.979 | 0.054 [0.02–0.09] | 0.025 | 0.873 |

| Psychological Well-being | 33.073 | 20 | 1.654 | 0.980 | 0.972 | 0.047 [0.01–0.07] | 0.033 | 0.825 |

| Variables | M | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | 1.432 | 0.496 | 0.276 | −1.937 | 1 | |||||

| 2. Age | 9.790 | 0.699 | 0.554 | 0.048 | −0.244 ** | 1 | ||||

| 3. GM | 4.390 | 1.236 | −0.641 | −0.281 | −0.026 | 0.025 | 1 | |||

| 4. Grit | 4.116 | 0.812 | −0.073 | −0.370 | −0.030 | −0.104 | 0.330 ** | 1 | ||

| 5. ASE | 3.604 | 0.826 | −0.234 | −0.020 | 0.012 | −0.108 | 0.289 ** | 0.415 ** | 1 | |

| 6. PWB | 5.467 | 1.088 | −0.695 | 0.147 | 0.005 | 0.037 | 0.222 ** | 0.426 ** | 0.475 ** | 1 |

| Variables | Predictors | R | R2 | F | β | t | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grit | GM | 0.352 | 0.124 | 14.001 *** | 0.331 | 6.099 *** | 0.148 | 0.288 |

| ASE | GM | 0.452 | 0.204 | 18.974 *** | 0.176 | 3.194 ** | 0.045 | 0.190 |

| Grit | 0.350 | 6.316 *** | 0.254 | 0.467 | ||||

| PWB | GM | 0.549 | 0.302 | 25.490 *** | 0.022 | 0.424 | −0.071 | 0.111 |

| GRIT | 0.281 | 5.076 *** | 0.231 | 0.523 | ||||

| ASE | 0.364 | 6.665 *** | 0.337 | 0.620 |

| Path | Effect Value | Boot SE | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLCI | ULCI | |||

| GM → Grit→ PWB | 0.082 | 0.021 | 0.044 | 0.124 |

| GM → ASE → PWB | 0.056 | 0.022 | 0.018 | 0.104 |

| GM → Grit→ ASE → PWB | 0.037 | 0.011 | 0.020 | 0.061 |

| Direct effect (GM → PWB) | 0.020 | 0.046 | -0.071 | 0.111 |

| Indirect effect | 0.175 | 0.033 | 0.113 | 0.243 |

| Total effect | 0.195 | 0.050 | 0.097 | 0.293 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Meng, Y.; Sun, Y.; Yang, L.; Othman Mydin, Y. Mechanisms from Growth Mindset to Psychological Well-Being of Chinese Primary School Students: The Serial Mediating Role of Grit and Academic Self-Efficacy. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 621. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050621

Meng Y, Sun Y, Yang L, Othman Mydin Y. Mechanisms from Growth Mindset to Psychological Well-Being of Chinese Primary School Students: The Serial Mediating Role of Grit and Academic Self-Efficacy. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(5):621. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050621

Chicago/Turabian StyleMeng, Yicen, Yan Sun, Lizhu Yang, and Yasmin Othman Mydin. 2025. "Mechanisms from Growth Mindset to Psychological Well-Being of Chinese Primary School Students: The Serial Mediating Role of Grit and Academic Self-Efficacy" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 5: 621. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050621

APA StyleMeng, Y., Sun, Y., Yang, L., & Othman Mydin, Y. (2025). Mechanisms from Growth Mindset to Psychological Well-Being of Chinese Primary School Students: The Serial Mediating Role of Grit and Academic Self-Efficacy. Behavioral Sciences, 15(5), 621. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050621