Owner Awareness, Motivation and Ethical Considerations in the Choice of Brachycephalic Breeds: Evidence from an Italian Veterinary Teaching Hospital Survey

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. Design of the Questionnaire

- What was the main reason for choosing a brachycephalic breed? (aesthetics/fashion; intelligence/behavior; other)

- Given the current popularity of this breed, do you think your choice may have been influenced by public figures who own brachycephalic dogs? (No; Yes)

- Are you aware of the genetic modifications affecting this breed? (No; Yes)

- Did you consult a veterinarian before purchasing your dog to learn about proper breed management? (No; Yes)

- Did you consult a veterinarian after purchasing your dog to learn about proper breed management? (No; Yes)

- Are you aware that this breed may have nasal stenosis (narrow nostrils that restrict airflow)? (No; Yes)

- Are you aware that these breeds may have an elongated soft palate, which can cause breathing difficulties? (No; Yes)

- Are you aware that these breeds may suffer from tracheal hypoplasia (smaller trachea), leading to breathing difficulties? (No; Yes)

- Have you ever had specific diagnostic tests performed to assess breathing problems (e.g., X-ray, endoscopy, CT scan)? (No; Yes)

- Are you aware that surgery may be an option to address these breathing issues? (No; Yes)

- Have you already opted for surgical procedures? (No; Yes)

- Would prior knowledge of these respiratory symptoms have influenced your decision to choose this breed? (No; Yes)

- Would knowledge of the costs associated with these procedures have influenced your purchasing decision? (No; Yes)

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

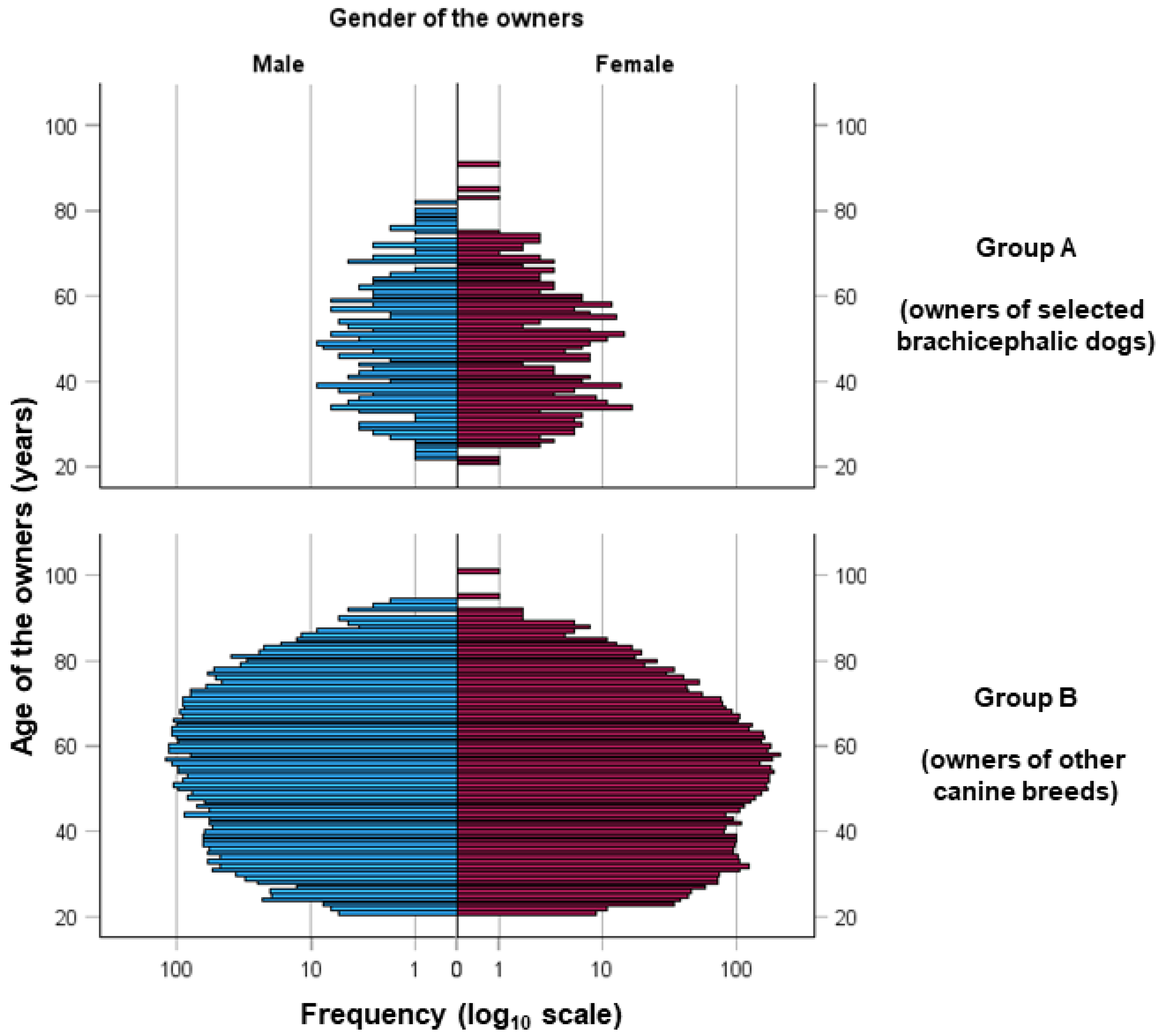

3.1. Study Population

3.2. Questionnaire Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Demographics

4.2. Owners’ Motivation

4.3. Veterinary Engagement

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BOAS | Brachycephalic Obstructive Airway Syndrome |

| SDB | Social Desirability Bias |

References

- American Kennel Club. The Most Popular Dog Breeds of 2024. Available online: https://www.akc.org/expert-advice/news/most-popular-dog-breeds-2024/ (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- O’Neill, D.G.; Baral, L.; Church, D.B.; Brodbelt, D.C.; Packer, R.M.A. Demography and disorders of the French Bulldog population under primary veterinary care in the UK in 2013. Canine Genet. Epidemiol. 2018, 5, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Royal Kennel Club. About The Kennel Club. Available online: https://www.thekennelclub.org.uk/about-us/about-the-kennel-club/ (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Onar, V.; Öztürk, N.; Chrószcz, A.; Poradowski, D.; Mutlu, Z. Skull of a brachycephalic dog unearthed in the ancient city of Tralleis, Türkiye. J. Archaeol. Sci.-Rep. 2023, 49, 103969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecht, J.; Horowitz, A. Seeing Dogs: Human Preferences for Dog Physical Attributes. Anthrozoos 2015, 28, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, E.S.; Coombe, E.; McGreevy, P.D.; Packer, R.M.A.; Neville, V. Are Brachycephalic Dogs Really Cute? Evidence from Online Descriptions. Anthrozoos 2023, 36, 533–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teng, K.T.; McGreevy, P.D.; Toribio, J.A.; Dhand, N.K. Trends in popularity of some morphological traits of purebred dogs in Australia. Canine Genet. Epidemiol. 2016, 3, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Federation of Veterinarians of Europe; Federation of European Companion Animal Veterinary Associations. FECAVA, FVE Position Paper on Breeding Healthy Dogs: The Effect of Selective Breeding on the Health and Welfare of Dogs. Available online: https://www.fecava.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/2018_06_Extreme_breeding_Final_adopted.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Wallace, M.L. Surgical management of brachycephalic obstructive airway syndrome: An update on options and outcomes. Vet. Surg. 2024, 53, 1173–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poncet, C.M.; Dupre, G.P.; Freiche, V.G.; Estrada, M.M.; Poubanne, Y.A.; Bouvy, B.M. Prevalence of gastrointestinal tract lesions in 73 brachycephalic dogs with upper respiratory syndrome. J. Small Anim. Pract. 2005, 46, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaye, B.M.; Rutherford, L.; Perridge, D.J.; Ter Haar, G. Relationship between brachycephalic airway syndrome and gastrointestinal signs in three breeds of dog. J. Small. Anim. Pract. 2018, 59, 670–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appelgrein, C.; Hosgood, G.; Thompson, M.; Coiacetto, F. Quantification of gastroesophageal regurgitation in brachycephalic dogs. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2022, 36, 927–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, J.; Steinmetz, A.; Delgado, E. Clinical signs of brachycephalic ocular syndrome in 93 dogs. Ir. Vet. J. 2021, 74, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlensker, E.; Distl, O. Prevalence, grading and genetics of hemivertebrae in dogs. EJCAP 2013, 23, 119–123. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:11176517 (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Mitze, S.; Barrs, V.R.; Beatty, J.A.; Hobi, S.; Beczkowski, P.M. Brachycephalic obstructive airway syndrome: Much more than a surgical problem. Vet. Q. 2022, 42, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commision. Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of tht Council on the Welfare of Dogs and Cats and Their Traceability. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:c16e01a8-94d9-11ee-b164-01aa75ed71a1.0001.02/DOC_1&format=PDF (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Packer, R.M.A.; Hendricks, A.; Burn, C.C. Do dog owners perceive the clinical signs related to conformational inherited disorders as ‘normal’ for the breed? A potential constraint to improving canine welfare. Anim. Welf. 2012, 21, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packer, R.M.A.; O’Neill, D.G.; Fletcher, F.; Farnworth, M.J. Great expectations, inconvenient truths, and the paradoxes of the dog-owner relationship for owners of brachycephalic dogs. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0219918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannas, S.; Palestrini, C.; Boero, S.; Garegnani, A.; Mazzola, S.M.; Prato-Previde, E.; Berteselli, G.V. Italians Can Resist Everything, Except Flat-Faced Dogs! Animals 2025, 15, 1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packer, R.M.; Hendricks, A.; Tivers, M.S.; Burn, C.C. Impact of Facial Conformation on Canine Health: Brachycephalic Obstructive Airway Syndrome. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0137496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carabalona, J.P.R.; Le Boedec, K.; Poncet, C.M. Complications, prognostic factors, and long-term outcomes for dogs with brachycephalic obstructive airway syndrome that underwent H-pharyngoplasty and ala-vestibuloplasty: 423 cases (2011-2017). J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2021, 260, S65–S73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Associazione Nazionale Medici Veterinari Italiani. Sindrome Brachicefalica: Indagine Nazionale Fra I Veterinari. Available online: https://www.anmvi.it/anmvi-notizie/973-sindrome-brachicefalica-indagine-nazionale-fra-i-veterinari.html (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- European Parliament and the Council of the European Union. Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation). Off. J. Eur. Union 2016, L 119/111–188. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32016R0679&qid=1749445762078 (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Holland, K.E.; Mead, R.; Casey, R.A.; Upjohn, M.M.; Christley, R.M. Why Do People Want Dogs? A Mixed-Methods Study of Motivations for Dog Acquisition in the United Kingdom. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 877950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandøe, P.; Kondrup, S.V.; Bennett, P.C.; Forkman, B.; Meyer, I.; Proschowsky, H.F.; Serpell, J.A.; Lund, T.B. Why do people buy dogs with potential welfare problems related to extreme conformation and inherited disease? A representative study of Danish owners of four small dog breeds. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0172091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Åsbjer, E.; Hedhammar, A.; Engdahl, K. Awareness, experiences, and opinions by owners, breeders, show judges, and veterinarians on canine Brachycephalic Obstructive Airway Syndrome (BOAS). Canine Med. Genet. 2024, 11, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallis, L.J.; Szabo, D.; Erdelyi-Belle, B.; Kubinyi, E. Demographic Change Across the Lifespan of Pet Dogs and Their Impact on Health Status. Front. Vet. Sci. 2018, 5, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bognár, Z.; Kubinyi, E. The brachycephalic paradox: The relationship between attitudes, demography, personality, health awareness, and dog-human eye contact. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2023, 264, 105948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packer, R.M.A.; Wade, A.; Neufuss, J. Nothing Could Put Me Off: Assessing the Prevalence and Risk Factors for Perceptual Barriers to Improving the Welfare of Brachycephalic Dogs. Pets 2024, 1, 458–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, H. Forty-two thousand and one Dalmatians: Fads, social contagion, and dog breed popularity. Soc. Anim. 2006, 14, 383–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Cioccio, M.; Pozharliev, R.; De Angelis, M. Pawsitively powerful: Why and when pet influencers boost social media effectiveness. Psychol. Mark. 2024, 41, 1614–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, V.; Huis in’t Veld, E.M.; Vingerhoets, A.J. The human and animal baby schema effect: Correlates of individual differences. Behav. Process 2013, 94, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vodičková, B.; Večerek, V.; Voslářová, E. The effect of adopter’s gender on shelter dog selection preferences. Acta Vet. Brno 2019, 88, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, M. “My Dog’s Just Like Me”: Dog Ownership as a Gender Display. Symb. Interact. 2006, 29, 373–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulhus, D.L. Two-component models of socially desirable responding. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1984, 46, 598–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bir, C.; Olynk Widmar, N.; Croney, C. Exploring Social Desirability Bias in Perceptions of Dog Adoption: All’s Well that Ends Well? Or Does the Method of Adoption Matter? Animals 2018, 8, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youens, E.; O’Neill, D.G.; Belshaw, Z.; Mochizuki, S.; Neufuss, J.; Tivers, M.S.; Packer, R.M.A. Beauty versus the beast: The UK public prefers less-extreme body shapes in brachycephalic dog breeds. Vet. Rec. 2025, e5671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mead, R.; Holland, K.E.; Casey, R.A.; Upjohn, M.M.; Christley, R.M. UK Dog Owners’ Pre-Acquisition Information- and Advice-Seeking: A Mixed Methods Study. Animals 2024, 14, 1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pound, L.; Farrow, M.; O’Neill, D.; Deane, D.J.; Packer, R.M.A. ‘All I do is fight fires’: Qualitative exploration of UK veterinarians’ attitudes towards and experiences of pre-purchase consultations regarding brachycephalic dogs. Vet Rec. 2024, 194, e3897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Breeds or Types of Dogs That Are Owned | Descriptive Statistics | Gender of Owner | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | |||

| French Bulldog | no. of owners (%) | 98 (33.6) | 194 (66.4) | 292 |

| Median age (years) | 46 | 47 | 47 | |

| Range (min–max) | 24–79 | 21–91 | 21–91 | |

| Bulldogs | no. of owners (%) | 57 (56.4) | 44 (43.6) | 101 |

| Median age (years) | 49 | 40 | 46 | |

| Range (min–max) | 22–82 | 26–74 | 22–82 | |

| Pugs | no. of owners (%) | 29 (34.1) | 56 (65.9) | 85 |

| Median age (years) | 51 | 48 | 50 | |

| Range (min–max) | 30–76 | 27–85 | 27–85 | |

| Boston Terriers | no. of owners (%) | 7 (36.8) | 12 (63.2) | 19 |

| Median age (years) | 52 | 56 | 56 | |

| Range (min–max) | 32–70 | 45–71 | 32–71 | |

| Selected brachycephalic dog breeds (Group A) | no. of owners (%) | 191 (38.4) | 306 (61.6) | 497 |

| Median age (years) | 49 | 47 | 48 | |

| Range (min–max) | 22–82 | 21–91 | 21–91 | |

| Other canine breeds (Group B) | no. of owners (%) | 4257 (40.9) | 6140 (59.1) | 10,397 |

| Median age (years) | 57 | 53 | 54 | |

| Range (min–max) | 21–94 | 21–101 | 21–101 | |

| Questions | Groups | Yes | No | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Given the current popularity of this breed, do you think your choice may have been influenced by public figures who own brachycephalic dogs? | Aesthetics/Fashion | 3 (14.3) | 18 (85.7) | 0.018 |

| Intelligence/Behavior | 0 (0.0) | 31 (100) | |||

| Other 1 | 0 (0.0) | 23 (100) | |||

| Total | 3 (4.0) | 72 (96.0) | |||

| 3 | Are you aware of the genetic modifications affecting this breed? | Aesthetics/Fashion | 17 (81.0) | 4 (19.0) | 0.319 |

| Intelligence/Behavior | 27 (87.1) | 4 (12.9) | |||

| Other 1 | 22 (95.7) | 1 (4.3) | |||

| Total | 66 (88.0) | 9 (12.0) | |||

| 4 | Did you consult a veterinarian before purchasing your dog to learn about proper breed management? | Aesthetics/Fashion | 5 (23.8) | 16 (76.2) | <0.001 |

| Intelligence/Behavior | 21 (67.7) | 10 (32.3) | |||

| Other 1 | 1 (4.3) | 22 (95.7) | |||

| Total | 27 (36.0) | 48 (64.0) | |||

| 5 | Did you consult a veterinarian after purchasing your dog to learn about proper breed management? | Aesthetics/Fashion | 18 (85.7) | 3 (14.3) | 0.350 |

| Intelligence/Behavior | 30 (96.8) | 1 (3.2) | |||

| Other 1 | 21 (91.3) | 2 (8.7) | |||

| Total | 69 (92.0) | 6 (8.0) |

| Questions | Groups | Yes | No | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | Are you aware that this breed may have nasal stenosis (narrow nostrils that restrict airflow)? | Aesthetics/Fashion | 20 (95.2) | 1 (4.8) | 0.600 |

| Intelligence/Behavior | 30 (96.8) | 1 (3.2) | |||

| Other 1 | 23 (100) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| Total | 73 (97.3) | 2 (2.7) | |||

| 7 | Are you aware that these breeds may have an elongated soft palate, which can cause breathing difficulties? | Aesthetics/Fashion | 18 (85.7) | 3 (14.3) | 0.115 |

| Intelligence/Behavior | 31 (100) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| Other 1 | 21 (91.3) | 2 (8.7) | |||

| Total | 70 (93.3) | 5 (6.7) | |||

| 8 | Are you aware that these breeds may suffer from tracheal hypoplasia (a smaller trachea), leading to breathing difficulties? | Aesthetics/Fashion | 15 (71.4) | 6 (28.6) | 0.718 |

| Intelligence/Behavior | 25 (80.6) | 6 (19.4) | |||

| Other 1 | 17 (73.9) | 6 (26.1) | |||

| Total | 57 (76.0) | 18 (24.0) | |||

| 9 | Have you ever had specific diagnostic tests performed to assess breathing problems (e.g., X-ray, endoscopy, CT scan)? | Aesthetics/Fashion | 8 (38.1) | 13 (61.9) | 0.144 |

| Intelligence/Behavior | 19 (61.3) | 12 (38.7) | |||

| Other 1 | 15 (65.2) | 8 (34.8) | |||

| Total | 42 (56.0) | 33 (44.0) | |||

| 10 | Are you aware that surgery may be an option to address these breathing issues? | Aesthetics/Fashion | 17 (81.0) | 4 (19.0) | 0.190 |

| Intelligence/Behavior | 29 (93.5) | 2 (6.5) | |||

| Other 1 | 22 (95.7) | 1 (4.3) | |||

| Total | 68 (90.7) | 7 (9.3) | |||

| 11 | If so, have you already opted for surgical procedures? | Aesthetics/Fashion | 6 (28.6) | 15 (71.4) | 0.705 |

| Intelligence/Behavior | 12 (38.7) | 19 (61.3) | |||

| Other 1 | 9 (39.1) | 14 (60.9) | |||

| Total | 27 (36.0) | 48 (64.0) | |||

| 12 | Would prior knowledge of these respiratory symptoms have influenced your decision to choose this breed? | Aesthetics/Fashion | 5 (23.8) | 16 (76.2) | <0.001 |

| Intelligence/Behavior | 1 (3.2) | 30 (96.8) | |||

| Other 1 | 11 (47.8) | 12 (52.2) | |||

| Total | 17 (22.7) | 58 (77.3) | |||

| 13 | Would knowledge of the costs associated with these procedures have influenced your purchasing decision? | Aesthetics/Fashion | 5 (23.8) | 16 (76.2) | 0.080 |

| Intelligence/Behavior | 1 (3.2) | 30 (96.8) | |||

| Other 1 | 4 (17.4) | 19 (82.6) | |||

| Total | 10 (13.3) | 65 (86.7) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martelli, G.; Ostanello, F.; Capitelli, M.; Pietra, M. Owner Awareness, Motivation and Ethical Considerations in the Choice of Brachycephalic Breeds: Evidence from an Italian Veterinary Teaching Hospital Survey. Animals 2025, 15, 2288. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15152288

Martelli G, Ostanello F, Capitelli M, Pietra M. Owner Awareness, Motivation and Ethical Considerations in the Choice of Brachycephalic Breeds: Evidence from an Italian Veterinary Teaching Hospital Survey. Animals. 2025; 15(15):2288. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15152288

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartelli, Giovanna, Fabio Ostanello, Margherita Capitelli, and Marco Pietra. 2025. "Owner Awareness, Motivation and Ethical Considerations in the Choice of Brachycephalic Breeds: Evidence from an Italian Veterinary Teaching Hospital Survey" Animals 15, no. 15: 2288. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15152288

APA StyleMartelli, G., Ostanello, F., Capitelli, M., & Pietra, M. (2025). Owner Awareness, Motivation and Ethical Considerations in the Choice of Brachycephalic Breeds: Evidence from an Italian Veterinary Teaching Hospital Survey. Animals, 15(15), 2288. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15152288