Policies towards Migrants in the Yangtze River Delta Urban Region, China: Does Local Hukou Still Matter after the Hukou Reform?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- What are the differences in city level hukou access policies and how can these differences be explained?

- To what extent do the local hukou policies influence the permanent settlement and the hukou transfer intention of migrants?

2. Literature Review

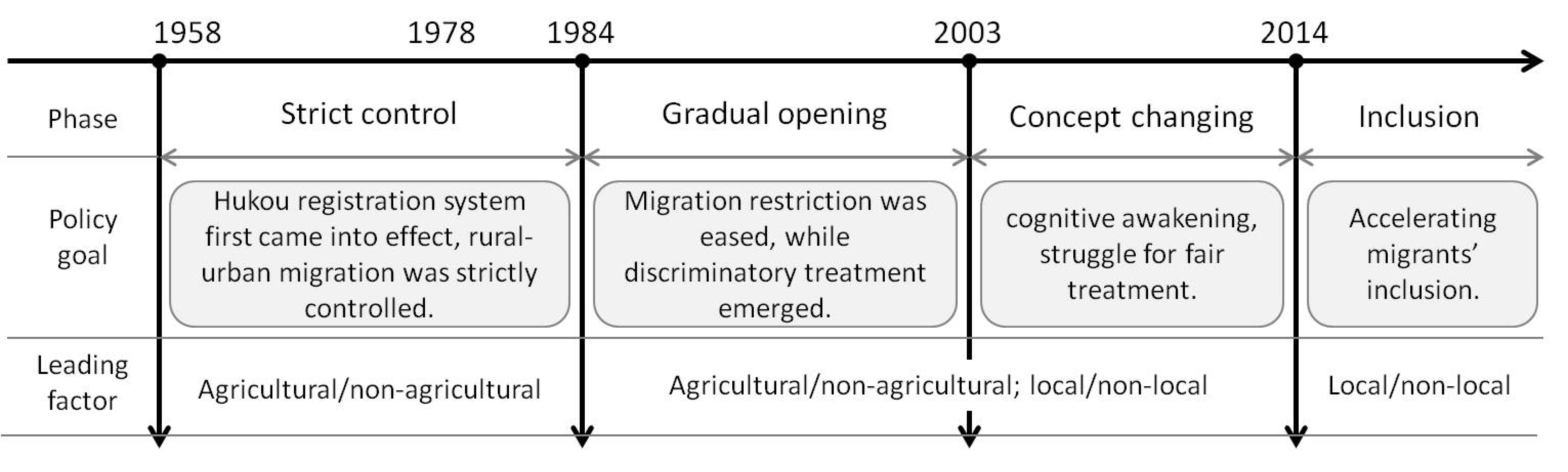

2.1. The Development of the Chinese Hukou System

2.1.1. Historical Development

2.1.2. The 2014 Hukou Reform

2.2. Permanent Settlement and Hukou Transfer Intentions of Migrants

3. Study Area and Data

3.1. Study Area

- The selected cities needed to have a balanced spread over the three provinces;

- The selected cities needed to represent different population sizes, economic characteristics, and administrative levels;

- Information on local hukou policies needed to be available.

3.2. Data

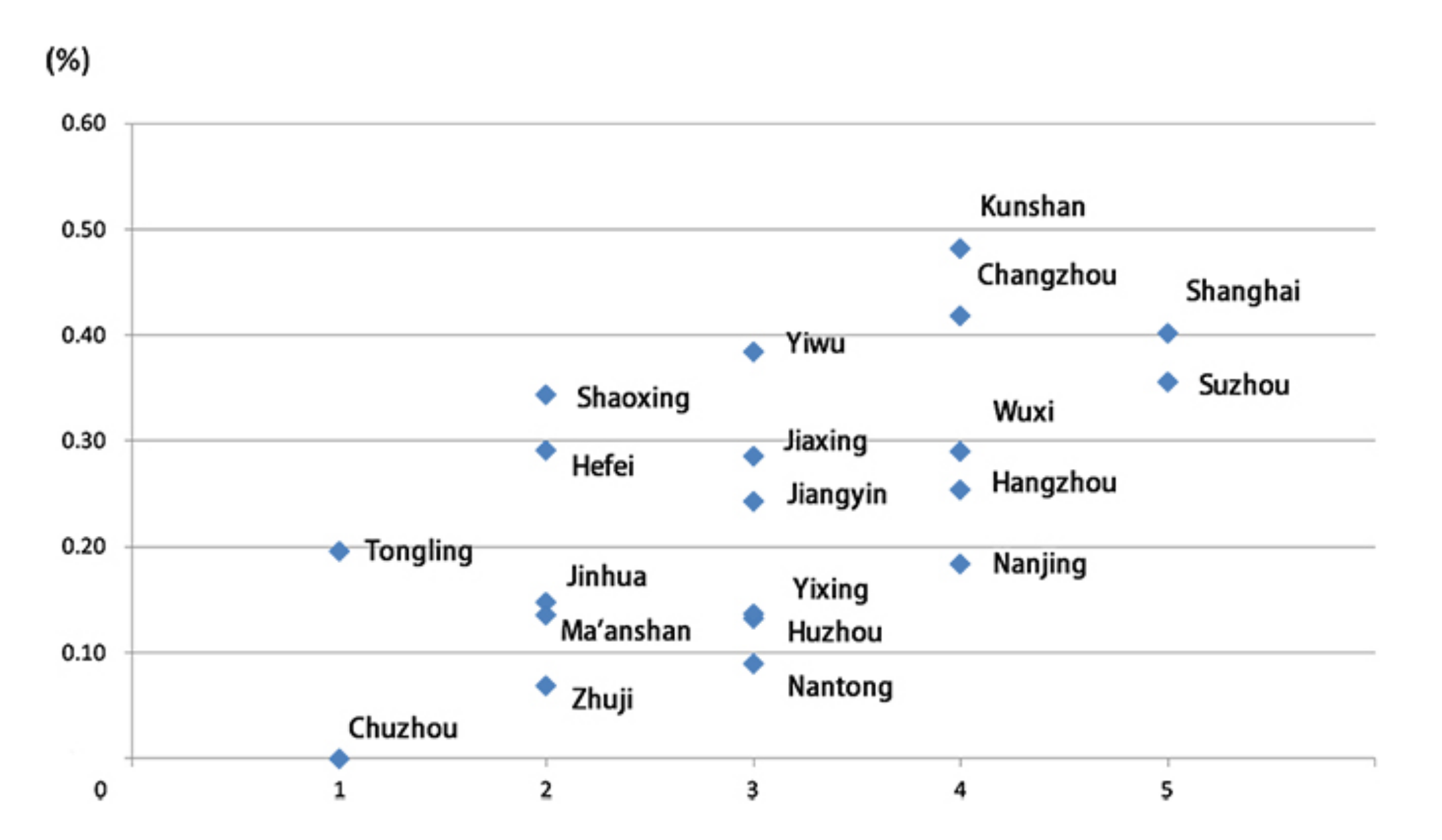

4. Explaining Stringency of Local Hukou Access Policies

4.1. Methods

4.2. Determinants of the Strictness of Local Hukou Policies

5. Local Hukou Policy and Intentions of Migrants

5.1. Introduction and Bivariate Analysis

5.2. Multivariate Analysis

Independent Variables

5.3. Regression Results

5.3.1. Influence of Strictness of Hukou Access Policies

5.3.2. Influence of Socio-Demographic Features

5.3.3. Influence of Migration Factors

5.3.4. Influence of Financial Factors

5.3.5. Influence of Housing Factors

5.3.6. Influence of Integration Factors

6. Conclusions

7. Discussion and Policy Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| No. | City | Index Value by Zhang | Stringency Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Shanghai | 2.1385 | 5 |

| 2 | Nanjing | 0.7379 | 4 |

| 3 | Hangzhou | 0.8621 | 4 |

| 4 | Suzhou | 1.3032 | 5 |

| 5 | Changzhou | 0.7917 | 4 |

| 6 | Hefei | 0.4403 | 2 |

| 7 | Wuxi | 0.8621 | 4 |

| 8 | Shaoxing | - | 2 |

| 9 | Nantong | 0.5886 | 3 |

| 10 | Kunshan | - | 4 |

| 11 | Jiangyin | - | 3 |

| 12 | Yiwu | - | 3 |

| 13 | Huzhou | 0.5908 | 3 |

| 14 | Jiaxing | 0.4694 | 3 |

| 15 | Yixing | - | 3 |

| 16 | Zhuji | - | 2 |

| 17 | Jinhua | - | 2 |

| 18 | Ma’anshan | 0.3897 | 2 |

| 19 | Tongling | 0.3243 ∗ | 1 |

| 20 | Chuzhou | 0.4306 ∗ | 1 |

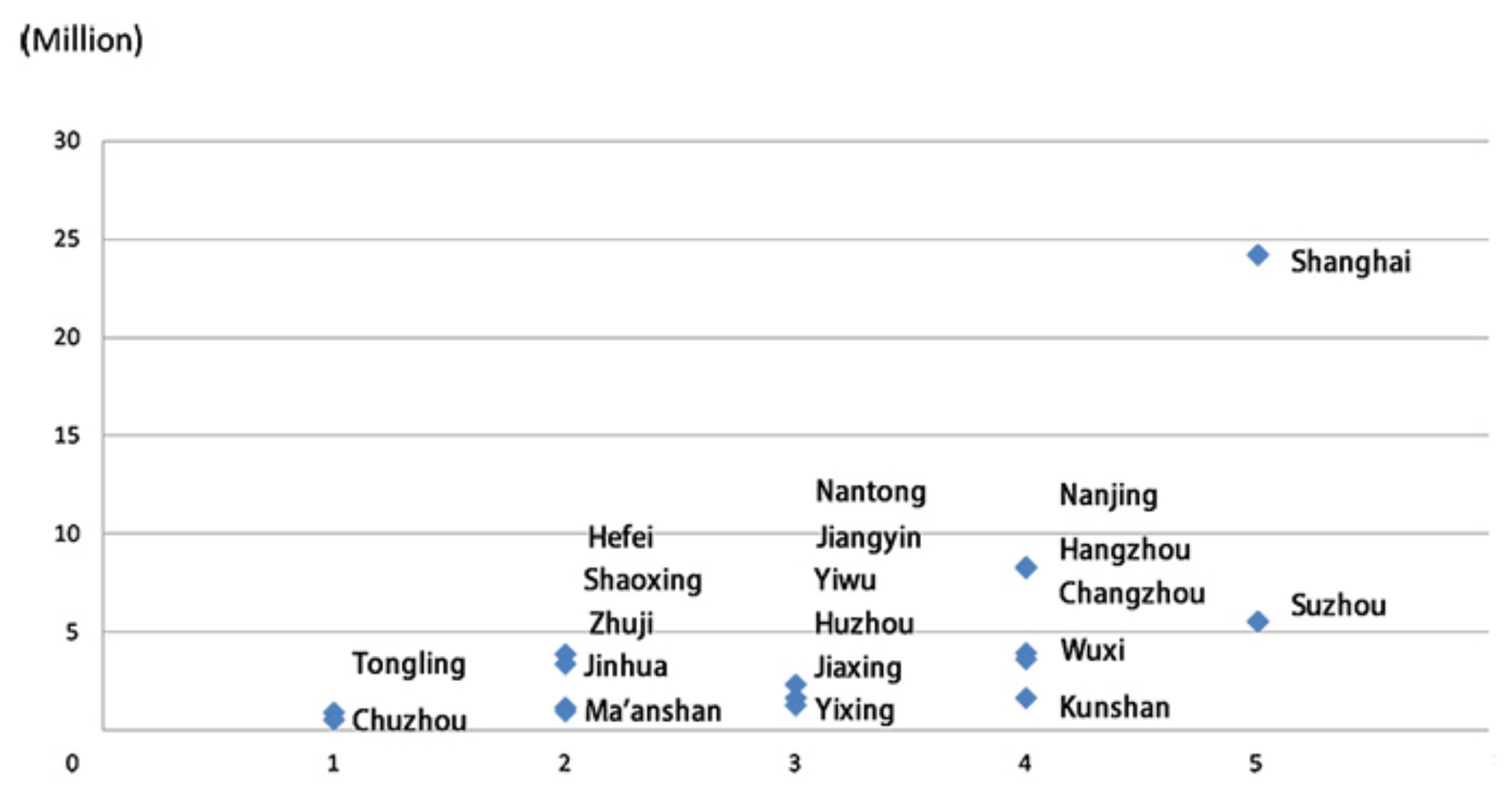

Appendix B

| No. | City Name | De Facto Population (Million) | De Jure Population (Million) | Proportion of Migrant Population (%) | City District Area (km2) | GDP (Billion Yuan) | Per Capita GDP (Yuan) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Shanghai | 24.18 | 14.46 | 0.40 | 6340.5 | 3063.3 | 126,687 |

| 2 | Nanjing | 8.34 | 6.81 | 0.18 | 6596 | 1171.51 | 141,103 |

| 3 | Hangzhou | 8.24 | 6.15 | 0.25 | 8000 | 1162.15 | 143,392 |

| 4 | Suzhou | 5.53 | 3.56 | 0.36 | 4652.84 | 777.7 | 140,632 |

| 5 | Changzhou | 3.95 | 2.3 | 0.42 | 2837.63 | 576.04 | 145,833 |

| 6 | Hefei | 3.85 | 2.73 | 0.29 | 1283 | 481.25 | 88,456 |

| 7 | Wuxi | 3.65 | 2.59 | 0.29 | 1643.88 | 546.53 | 149,734 |

| 8 | Shaoxing | 3.37 | 2.21 | 0.34 | 2965 | 295.17 | 87,588 |

| 9 | Nantong | 2.35 | 2.14 | 0.09 | 1629 | 286.26 | 121,813 |

| 10 | Kunshan | 1.66 | 0.86 | 0.48 | 931.51 | 352.04 | 212,072 |

| 11 | Jiangyin | 1.65 | 1.25 | 0.24 | 986.97 | 348.83 | 211,412 |

| 12 | Yiwu | 1.3 | 0.8 | 0.38 | 1105 | 115.52 | 88,862 |

| 13 | Huzhou | 1.29 | 1.12 | 0.13 | 1565 | 108.5 | 97,457 |

| 14 | Jiaxing | 1.26 | 0.9 | 0.29 | 987 | 112.55 | 89,889 |

| 15 | Yixing | 1.25 | 1.08 | 0.14 | 1996.61 | 155.83 | 124,664 |

| 16 | Zhuji | 1.17 | 1.09 | 0.07 | 2311 | 116.54 | 99,607 |

| 17 | Jinhua | 1.15 | 0.98 | 0.15 | 2094 | 74.14 | 64470 |

| 18 | Ma’anshan | 0.96 | 0.83 | 0.14 | 704 | 104.25 | 74,709 |

| 19 | Tongling | 0.92 | 0.74 | 0.20 | 1064.47 | 88.5 | 96,196 |

| 20 | Chuzhou | 0.56 | 0.56 | 0.00 | 1405.5 | 19.32 | 34,500 |

References

- National Health Commission. Report on China’s Migration Population Development, 1st ed.; China Population Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2018.

- Guo, Y.; Qiao, W. Rural Migration and Urbanization in China: Historical Evolution and Coupling Pattern. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Démurger, S.; Gurgand, M.; Li, S.; Yue, X. Migrants as second-class workers in urban China? A decomposition analysis. J. Comp. Econ. 2009, 37, 610–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Combes, P.-P.; Démurger, S.; Li, S.; Wang, J. Unequal migration and urbanisation gains in China. J. Dev. Econ. 2020, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, R.; Lu, C. A quantitative analysis of Hukou reform in Chinese cities: 2000–2016. Growth Chang. 2019, 50, 201–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Deng, W.; Hoekstra, J.; Elsinga, M. Redistribution, Growth, and Inclusion: The Development of the Urban Housing System in China, 1949–2015. Curr. Urban Stud. 2017, 5, 423–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chan, K.W.; Zhang, L. The hukou system and rural-urban migration in China: Processes and changes. China Q. 1999, 160, 818–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Xu, Q.; Guan, X.; Yao, F. Welfare program participation among rural-to-urban migrant workers in China. Int. J. Soc. Welf. 2011, 20, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, R.E. Life earnings and rural-urban migration. J. Political Econ. 2004, 112, 29–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Opinions on Further Promoting the Reform of Hukou Registration System. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2014-07/30/content_8944.htm (accessed on 1 May 2019).

- Chan, K.W.; Wang, M. Remapping China’s regional inequalities, 1990–2006: A new assessment of de facto and de jure population data. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 2008, 49, 21–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, X. Living Space Analysis for Migrant Population in China’s Megacities, 1st ed.; Southeast University Press: Nanjing, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, X. Labor Market Outcomes and Reforms in China. J. Econ. Perspect. 2012, 26, 75–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Qiu, L.; Zhao, D. Urban inclusiveness and income inequality in China. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2019, 74, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Guo, F. Breaking the barriers: How urban housing ownership has changed migrants’ settlement intentions in China. Urban Stud. 2018, 55, 3689–3707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xu, W. Destination Choices of Permanent and Temporary Migrants in China, 1985–2005. Popul. Space Place 2017, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provisional Regulations on Residence Permit. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2015-12/12/content_10398.htm (accessed on 1 May 2019).

- Zhou, J. The New Urbanisation Plan and permanent urban settlement of migrants in Chongqing, China. Popul. Space Place 2018, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xiao, L.; Qiu, Q.; Gao, L. Chinese Housing Reform and Social Sustainability: Evidence from Post-Reform Home Ownership. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gu, H.; Liu, Z.; Shen, T. Spatial pattern and determinants of migrant workers’ interprovincial hukou transfer intention in China: Evidence from a National Migrant Population Dynamic Monitoring Survey in 2016. Popul. Space Place 2019, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Wang, J. Bringing city size in understanding the permanent settlement intention of rural–urban migrants in China. Popul. Space Place 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Deng, W.; Song, X. Influence factor analysis of migrants’ settlement intention: Considering the characteristic of city. Appl. Geogr. 2018, 96, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Tao, L. Barriers to the Acquisition of Urban Hukou in Chinese Cities. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2012, 44, 2883–2900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Zhang, L. Developmental governance and urban hukou registration barrier. Sociol. Study 2010, 6, 58–85. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Fan, C.C. China’s Hukou Puzzle: Why Don’t Rural Migrants Want Urban Hukou. China Rev. 2016, 16, 9–39. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, L.; Zhao, M.Q. Permanent and temporary rural–urban migration in China: Evidence from field surveys. China Econ. Rev. 2018, 51, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Xu, W.; Liu, Y.; Ning, Y.; Klein, K.K. Staying in the countryside or moving to the city: The deternminants of villagers’ urban settlement intention in China. China Rev. 2016, 16, 41–68. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, C.; Wallace, J.L. Toward Human-Centered Urbanization? Housing Ownership and Access to Social Insurance Among Migrant Households in China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xie, S.; Chen, J. Beyond homeownership: Housing conditions, housing support and rural migrant urban settlement intentions in China. Cities 2018, 78, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Liu, Y.; Xue, D.; Li, Z.; Shi, Z. The effects of social ties on rural-urban migrants’ intention to settle in cities in China. Cities 2018, 83, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, P.; Tang, S. Migration destinations in the urban hierarchy in China: Evidence from Jiangsu. Popul. Space Place 2018, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Development Plan of Yangtze River Delta Urban Region. Available online: https://www.ndrc.gov.cn/xxgk/zcfb/ghwb/201606/W020190905497826154295.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2019).

- Li, Y.; Wu, F. Understanding city-regionalism in China: Regional cooperation in the Yangtze River Delta. Reg. Stud. 2018, 52, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.W. Misconceptions and complexities in the study of China’s cities: Definitions, statistics, and implications. Eurasian Geography and Economics 2007, 48, 383–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Zhang, L.; Chen, X. Barriers in hukou registration reform. China Popul. Sci. 2010, 1, 66–74. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, K.W. The Global Financial Crisis and Migrant Workers in China: ‘There is No Future as a Labourer; Returning to the Village has No Meaning’. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2010, 34, 659–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Z.; Yang, S. Characteristics of Urban Expansion in the Yangtze River Delta in a High Economics Growth Period: A Comparison Between Wuxi and Kunshan in Metropolitan Fringe of Shanghai. In Urban Development Challenges, Risks and Resilience in Asian Mega Cities; Singh, R.B., Ed.; Springer: Tokyo, Japan, 2015; pp. 251–272. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, S.; Feng, J. Cohort differences in the urban settlement intentions of rural migrants: A case study in Jiangsu Province, China. Habitat Int. 2015, 49, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Liu, Z. What determines the settlement intention of rural migrants in China? Economic incentives versus sociocultural conditions. Habitat Int. 2016, 58, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, G.; Li, M.; Ma, Y.; Tao, R. Self-employment and intention of permanent urban settlement: Evidence from a survey of migrants in China’s four major urbanising areas. Urban Stud. 2014, 52, 639–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opinions on the Reform of the System and Mechanism for Promoting the Social Mobility of Labor and Talent. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2019-12/25/content_5463978.htm (accessed on 1 March 2020).

- Key Tasks for the New Type of Urbanization. 2019. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2019-04/08/content_5380457.htm (accessed on 1 March 2020).

- Greenwood, M.J. Internal migration in developing countries. In Handbook of Population and Family Economics, 1st ed.; Rosenzweig, R.R., Stark, O., Eds.; North Holland Publishing Company: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1997; Volume 1, pp. 648–712. [Google Scholar]

- Molloy, R.; Smith, C.L.; Wozniak, A. Internal Migration in the United States. J. Econ. Perspect. 2011, 25, 173–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chandrasekhar, S.; Sharma, A. Urbanization and Spatial Patterns of Internal Migration in India. Spat. Demogr. 2015, 3, 63–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholten, P.; Van Ostaijen, M. Between mobility and migration: The consequences and governance of intra-European movement. In Between Mobility and Migration: The Multi-Level Governance of European Movement, 1st ed.; Scholten, P., Van Ostaijen, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

| No. | City | No. | City |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Shanghai | 11 | Jiangyin |

| 2 | Nanjing | 12 | Yiwu |

| 3 | Hangzhou | 13 | Huzhou |

| 4 | Suzhou | 14 | Jiaxing |

| 5 | Changzhou | 15 | Yixing |

| 6 | Hefei | 16 | Zhuji |

| 7 | Wuxi | 17 | Jinhua |

| 8 | Shaoxing | 18 | Ma’anshan |

| 9 | Nantong | 19 | Tongling |

| 10 | Kunshan | 20 | Chuzhou |

| No. | City | Sample Size | No. | City | Sample Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Shanghai | 7000 | 11 | Jiangyin | 560 |

| 2 | Nanjing | 2000 | 12 | Yiwu | 520 |

| 3 | Hangzhou | 1800 | 13 | Huzhou | 240 |

| 4 | Suzhou | 960 | 14 | Jiaxing | 360 |

| 5 | Changzhou | 760 | 15 | Yixing | 240 |

| 6 | Hefei | 1580 | 16 | Zhuji | 120 |

| 7 | Wuxi | 1120 | 17 | Jinhua | 240 |

| 8 | Shaoxing | 440 | 18 | Ma’anshan | 120 |

| 9 | Nantong | 200 | 19 | Tongling | 160 |

| 10 | Kunshan | 440 | 20 | Chuzhou | 240 |

| Level | Stringency | Criteria | City | Index Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Very low | Stable residence (including private rental) or legal stable employment. | Tongling, Chuzhou | <0.3 |

| 2 | Low | Requires 2 years (or less) of local residence, working and participation in social security scheme; or other additional conditions, such as education, housing purchase. | Hefei, Shaoxing, Zhuji, Jinhua, Ma’anshan | 0.3–0.5 |

| 3 | Medium | Requires 3 years (or less) of local residence, working and participation in social security scheme; or other additional conditions, such as education, housing purchase. | Jiangyin, Yiwu, Jiaxing, Yixing, Nantong, Huzhou | 0.5–0.7 |

| 4 | High | Requires 5 years (or less) of local residence, working and participation in social security scheme; or other additional conditions, such as education, housing purchase. | Nanjing, Hangzhou, Changzhou, Wuxi, Kunshan | 0.7–1.0 |

| 5 | Very high | Requires more than 5 years of local residence, working and participation in social security scheme or other additional conditions, such as education, housing purchase plus waiting in line. | Shanghai, Suzhou | >1.0 |

| Reasons for Permanent Settlement | Hukou Stringency Level | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Average | |

| 1. Career development and income | 14.4% | 13.6% | 34.8% | 35.6% | 33.2% | 30.3% |

| 2. Convenient urban life | 9.6% | 11.1% | 7.8% | 11.1% | 6.6% | 8.6% |

| 3. Better education for children | 38.9% | 46.6% | 29.3% | 28.6% | 27.7% | 31.2% |

| 4. Better medical care | 0.0% | 0.9% | 0.0% | 0.9% | 1.4% | 1.1% |

| 5. Local social network | 13.5% | 8.3% | 15.2% | 10.3% | 17.9% | 14.3% |

| 6. Better governance | 1.0% | 0.9% | 0.4% | 0.8% | 1.4% | 1.1% |

| 7. Family used to local situation | 18.8% | 16.6% | 10.4% | 10.2% | 10.2% | 11.4% |

| 8. Other | 3.8% | 1.9% | 2.2% | 2.5% | 1.6% | 2.0% |

| Variables | Number of Cases | (%)/Mean | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variables | |||

| Permanent settlement intention | Yes | 6180 | 32.4 |

| No | 12,920 | 67.6 | |

| Hukou transfer intention | Yes | 9627 | 50.4 |

| No | 9473 | 49.6 | |

| Independent variables | |||

| Institutional factors | |||

| Strictness of local hukou access policies | Very low (level 1) | 400 | 2.1 |

| Low (level 2) | 2500 | 13.1 | |

| Medium (level 3) | 2120 | 11.1 | |

| High (level 4) | 6120 | 32.0 | |

| Very high (level 5) | 7960 | 41.7 | |

| Sociodemographic factors | |||

| Gender | Male | 9804 | 51.3 |

| Female | 9296 | 48.7 | |

| Generation | First generation (born ≤1980) | 7669 | 40.2 |

| New generation (born > 1980) | 11,426 | 59.8 | |

| Marital status | Married | 15,999 | 83.8 |

| Single | 3101 | 16.2 | |

| Education | Primary school and below | 2741 | 14.4 |

| Junior high | 7924 | 41.5 | |

| Secondary school/senior high | 4010 | 21.0 | |

| College and above | 4425 | 23.2 | |

| Hukou type | Agricultural hukou | 14,830 | 77.7 |

| Non-agricultural hukou | 4263 | 22.3 | |

| Migration experiences | |||

| Migration scope | Inter-province | 14,505 | 75.9 |

| Intra-province | 4595 | 24.1 | |

| Local migration duration (years) | Average in years | 19,100 | 6.6 years |

| Total migration duration (years) | Average in years | 19,100 | 12.1 years |

| Total migration frequency | Average number of moves | 19,100 | 2.2 |

| Financial and employment situation | |||

| Monthly family income | <4000 yuan | 2233 | 11.7 |

| 4000–8000 yuan | 8528 | 44.6 | |

| 8000–12,000 yuan | 4647 | 24.3 | |

| ≥12,000 yuan | 3692 | 19.3 | |

| Employment status | Self-employed | 4370 | 22.9 |

| Employee | 12,100 | 63.4 | |

| Unemployed | 2630 | 13.8 | |

| Farmland | Farmland in possession | 8856 | 46.4 |

| No farmland in possession | 10,244 | 53.6 | |

| Housing factor | |||

| Housing tenure | Dormitory provided by employer | 2367 | 12.4 |

| Rental housing | 11,401 | 59.7 | |

| Home ownership housing | 4968 | 26.0 | |

| Home of relatives and friends | 201 | 1.1 | |

| Monthly housing expenditure(rents and loans) | 0 yuan | 4392 | 23.0 |

| 0–1000 yuan | 8561 | 44.8 | |

| 1000–2000 yuan | 2808 | 14.7 | |

| >2000 yuan | 3339 | 17.5 | |

| Integration factors | |||

| Perception of belonging | Yes | 12,297 | 64.4 |

| No | 6803 | 35.6 | |

| Degree of local interaction | Mainly with local friends | 4614 | 24.2 |

| Mainly with non-local friends | 9964 | 52.2 | |

| Rarely interacts with others | 4522 | 23.7 | |

| Participation in local social insurance schemes | Yes | 11,044 | 57.8 |

| No | 8056 | 42.2 | |

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | P | Exp (b) | b | P | Exp (b) | |

| Institutional factor | ||||||

| Hukou access stringency level (ref: Level 5) | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||

| Level 4 | −0.32 | 0.000 | 0.73 | −0.94 | 0.000 | 0.39 |

| Level 3 | −1.04 | 0.000 | 0.36 | −1.44 | 0.000 | 0.24 |

| Level 2 | −0.43 | 0.000 | 0.65 | −1.92 | 0.000 | 0.15 |

| Level 1 | −0.22 | 0.103 | 0.80 | −2.43 | 0.000 | 0.09 |

| Socio-demographic factors | ||||||

| Gender (ref: Female) | −0.20 | 0.000 | 0.82 | −0.12 | 0.001 | 0.89 |

| Generation (ref: New generation) | −0.44 | 0.000 | 0.65 | −0.12 | 0.006 | 0.89 |

| Education (ref: College and above) | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||

| Secondary school/senior high | −0.54 | 0.000 | 0.58 | −0.36 | 0.000 | 0.70 |

| Junior high | −0.83 | 0.000 | 0.44 | −0.65 | 0.000 | 0.52 |

| Primary school and below | −0.94 | 0.000 | 0.39 | −0.74 | 0.000 | 0.48 |

| Hukou type (ref: Non-agricultural hukou) | −0.32 | 0.000 | 0.73 | −0.45 | 0.000 | 0.64 |

| Migration feature | ||||||

| Migration scope (ref: intra-province) | −0.24 | 0.000 | 0.79 | 0.18 | 0.000 | 1.20 |

| Local migration duration in years | 0.04 | 0.000 | 1.04 | 0.03 | 0.000 | 1.03 |

| Total migration duration in years | 0.02 | 0.000 | 1.02 | 0.02 | 0.000 | 1.02 |

| Total migration frequency | −0.04 | 0.004 | 0.96 | −0.01 | 0.294 | 0.99 |

| Financial factors | ||||||

| Monthly family income (ref: >12000 yuan) | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||

| 8000–12000 yuan | −0.23 | 0.010 | 0.79 | −0.28 | 0.000 | 0.76 |

| 4000–8000 yuan | −0.39 | 0.000 | 0.68 | −0.35 | 0.000 | 0.70 |

| <4000 yuan | −0.46 | 0.000 | 0.63 | −0.46 | 0.000 | 0.63 |

| Employment status (ref: Self-employed) | 0.000 | 0.007 | ||||

| Employee | −0.21 | 0.000 | 0.81 | −0.11 | 0.012 | 0.90 |

| Unemployed | 0.15 | 0.031 | 1.16 | 0.02 | 0.736 | 1.14 |

| Farmland (ref: No farmland) | 0.04 | 0.369 | 1.04 | −0.13 | 0.000 | 0.88 |

| Housing factors | ||||||

| Housing tenure (ref: Dormitory provided by employer) | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||

| Rental housing | 0.66 | 0.000 | 1.93 | 0.41 | 0.000 | 1.51 |

| Home ownership | 2.16 | 0.000 | 8.71 | 0.34 | 0.000 | 1.40 |

| Relatives and friends’ home | 1.11 | 0.000 | 3.04 | 0.18 | 0.295 | 1.20 |

| Monthly housing expenditure (ref: >2000 yuan) | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||

| 1000–2000 yuan | −0.13 | 0.043 | 0.88 | 0.65 | 0.304 | 1.07 |

| 0–1000 yuan | −0.60 | 0.000 | 0.55 | −0.29 | 0.000 | 0.75 |

| 0 yuan | −0.04 | 0.536 | 0.96 | −0.02 | 0.787 | 0.98 |

| Integration factors | ||||||

| Perception of belonging (ref: No) | 0.93 | 0.000 | 2.53 | 0.55 | 0.000 | 1.72 |

| Local interaction (ref: Local friends) | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||

| Non-local friends | −0.56 | 0.000 | 0.57 | −0.30 | 0.000 | 0.74 |

| Rarely interacting with others | −0.52 | 0.000 | 0.60 | −0.37 | 0.000 | 0.69 |

| Participation in local social insurance scheme? (ref: No) | 0.23 | 0.000 | 1.26 | 0.04 | 0.272 | 1.04 |

| Constant | −0.52 | 5.300 | 0.56 | 1.24 | 0.000 | 3.46 |

| Nagelkerke R-square | 0.47 (p < 0.001) | 0.30 (p < 0.001) | ||||

| Number of valid cases | 19,100 | 19,100 | ||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Q.; Hoekstra, J. Policies towards Migrants in the Yangtze River Delta Urban Region, China: Does Local Hukou Still Matter after the Hukou Reform? Sustainability 2020, 12, 10448. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410448

Zhang Q, Hoekstra J. Policies towards Migrants in the Yangtze River Delta Urban Region, China: Does Local Hukou Still Matter after the Hukou Reform? Sustainability. 2020; 12(24):10448. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410448

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Qian, and Joris Hoekstra. 2020. "Policies towards Migrants in the Yangtze River Delta Urban Region, China: Does Local Hukou Still Matter after the Hukou Reform?" Sustainability 12, no. 24: 10448. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410448