Abstract

International organizations, public authorities and researchers have increasingly been concerned with urban resilience and sustainability. We focus on the triangle retail, urban resilience and city sustainability, aiming to uncover how cities have coped with retail challenges to increase their resilience towards a sustainable path, highlighting the role played by public policy. The case study asks, is Central Lisbon strongly affected by processes of regeneration, touristification and gentrification, simultaneously with changes in retail. The analysis of planning and other policy documents complemented by fieldwork evidence shows a close link between public initiatives and private entrepreneurship and their impacts in the vitality of the core. The text shows that the policy outlined by local authorities to overcome the decline of the city center and to meet the aims of sustainability implies urban resilience. The transformation of retail is aligned with that vision and is supported its achievement, while the commercial fabric suffered an evolution from shopping to consumption spaces, polarized by culture and entertainment, targeting new consumers and lifestyles. However, new social and economic challenges arise due to escalating housing prices, change in retail supply, the excessive dependence of tourism and the danger of losing part of the city’s identity.

1. Introduction

Commerce is in the very nature of the urban. Besides other functions, retail gives character to townscapes and participates in the image locals and foreigners have of the places. However, retail, as a product of the social agency, has changed over time in the formats and places for practices, and the values associated with them.

Changes both in retail, and in the relationship between city and retailing, challenge urban resilience and sustainability because they affect the vitality and viability of the traditional shopping districts, marginalize some disadvantaged consumers (the less mobile, the elderly, the disabled, among others) and reduce social cohesion, besides inducing movements with disturbing ecological footprints [1,2,3].

The change in the urban retail structure from the mid-1950s onwards is reflected in a decline of the high street functions, simplification of the traditional intraurban hierarchy with the disappearance of many shops at convenience and neighborhood levels, but complexification of the retail system with the rise of new retail centers in peripheral locations, although with differences between regions [4,5,6,7,8,9]. Large retail premises located outside the city center began to play a crucial role in an urban model based on diffuse city regions, with the population traveling greater distances to acquire goods, with the associated expense of time and fuel. More recently, e-commerce brought new challenges to the traditional shopping venues, distribution logistics and consumers’ practices [10]. Consumers’ behavior has changed to a point that consumption became an imperative dimension in assessing the vitality and resilience of urban retail systems and different types of shopping districts or concentrations [11,12].

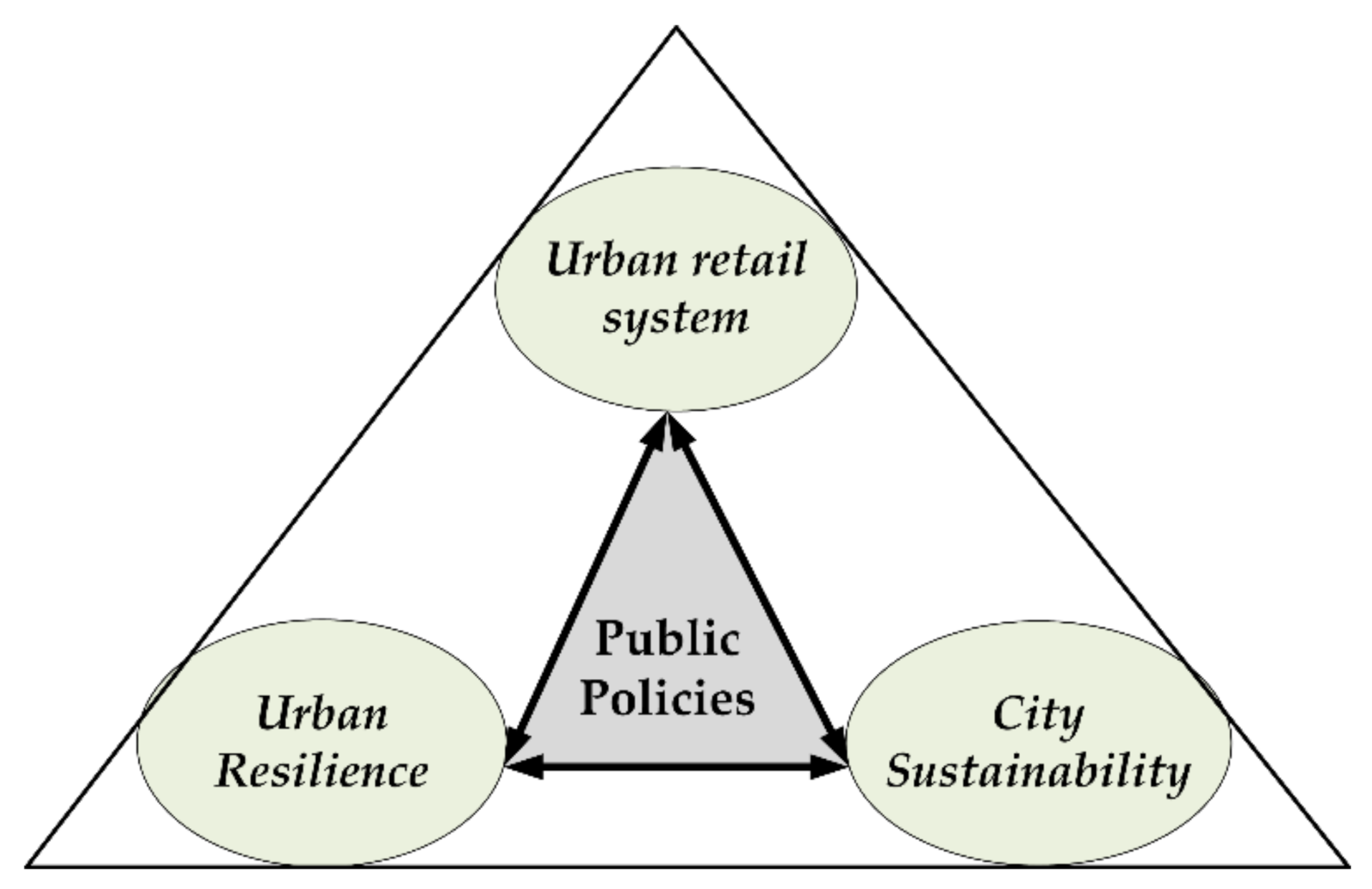

Our interest on the triangle of retail–urban resilience–city sustainability concerns the way retail systems contribute to cities’ resilience and sustainability, looking at retailing as a pillar in urban sustainability [13]. Much research has been produced on city resilience and city sustainability but not so much on the role of commerce for these urban dimensions, nor the role played by public policy in enhancing the retail system resilience (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Analytical framework. Source: authors (2020).

As geographers, we believe on the relevance of the concept of retail resilience for the study and understanding of urban sustainability with a territorial focus on the scale of the neighborhood, city center or other retail areas, at an urban meso-scale as Sharifi [14] calls. With the support of resilience theory, our aim is to discuss how cities have coped with retail challenges to increase their resilience and their path towards sustainability, giving special emphasis to the role played by public policy. Using Lisbon as case study, we will focus on the measures towards the revitalization of the town center.

We use a qualitative analysis based on literature, local planning documents and official regulations, surveys and interviews conducted along years of observation and data collection, although recently updated. The analytical framework of our research was performed through a thorough literature review on urban resilience and urban sustainability, with an emphasis on the value of both concepts to the analysis of urban retail. Furthermore, the analysis of grey literature (legislation, official reports and municipal documents on territorial planning and management) was particularly relevant to inform about policy guiding the evolution of the city center.

For several years, we have been following the urban and commercial transformation of the city of Lisbon. Thus, in addition to the data presented in this article, the discussion also benefits from the extensive consolidated knowledge about the city. Fieldwork and interviews were conducted with local retailers and key stakeholders at different moments. Within research projects on the economy or retail restructuring from 1992 onwards, many times the Lisbon city center has been used as a case study, in parallel with other neighborhoods, surveys and exploratory interviews with retailers and consumers conducted under the supervision of the authors. For this article, specifically, we used the following in-depth interviews from stakeholders: 21 with retailers with shops on Baixa and Chiado dating from 2013, 2015 and 2019; six with businesses associations at local, regional and national level in 2011, 2015, 2017, 2018; and five with municipal technicians from the Department of Economy and Retail, in 2011, 2015, 2018 and 2019. In January and February 2020, an upgrade of the survey of existent retail businesses in Lisbon city center and in the traditional covered market close by was conducted. We also used available data from the City Council on the number of retail business in the city in 2007, which were subsequently compared with data retrieved by the authors in 2015 and 2020.

Next, we will briefly analyze the conceptual connection between urban resilience and urban sustainability, whose discussion will frame our research, underlining the value of both concepts to urban planning and their usefulness for the study of retail changes and urban retail policies. After shedding light on the concerns with the resilience of urban retail fostered by public policies, both in general and in Portugal, on part three, in the fourth section we proceed with the analysis of the retail evolution in the Lisbon city center in the last decade. This analysis is framed by the recent evolution of urban rehabilitation policies in Lisbon, to show that retail change was fundamental for the fulfilment of the strategic vision of the city’s development aiming the attraction of foreign investments and visitors. The text ends with some concluding remarks.

2. Conceptual Discussion

Resilience is an old concept in psychology and physics and was (re)discovered by other scientific fields with the growth of disasters and unpredictability that characterise the risk society as theorised by Beck [15] and Giddens [16]. International organizations such as UN, OECD, EU, played a major role in the dissemination of the ideas of resilience and sustainability, and are also responsible for transferring the concepts to public policies.

Pu and Qiu [17] analyse 1296 articles on urban resilience, published between 1986 and 2015, and found two main clusters: the larger has its focus on ecology or socioecology perspectives; the other is related with psychology. According to Zhang and Li [18], the first article on urban sustainability dates from 1968 [19] and deals with the importance of ecology in land use planning, while the first article on resilience, in the contemporary sense, is the much-cited text by Holling [20]. The mentioned literature reviews show that publications on urban sustainability grew progressively until they reached a peak near the beginning of the new millennium, while those related to resilience began to grow more sharply since 2003 and exceeded in number those of sustainability in 2006.

2.1. Resilience

The concept of resilience was adapted from physics to ecology by Holling [20], where the focus is placed on the state of balance to which the system will return after having recovered from a shock; this concept is predominantly used in physical sciences and became known as “engineering resilience”. Later, the concerns with the functioning of the ecosystems, the conditions for persistence of a system continually confronted by the unexpected, led to a dynamic vision of resilience: the “ecological resilience”. The system’s resilience therefore would be the ability of a system to absorb change and disturbance without changing its structure, and could be measured either by the speed to return to the equilibrium (old or new) or to the intensity of the shock it can absorb [21]. This understanding has been adapted to the social sciences, in relation to resource management [22,23,24] and natural disasters [25,26] and later to face economic crises and generating sustainability [27].

The third type of resilience is the adaptive resilience based in the complex systems theory which states the ability of these systems to anticipate or recognize shocks and to adapt or reorganize in face of them. It is close to the evolutionary approaches in regional economy, geography and other social sciences (Polèse 2010, in Mendez [28,29,30,31]). In this view, resilience is a dynamic and evolutionary process of continual adjustment that takes place in the long run in a complex, uncertain and unpredictable world [32,33].

2.2. Retail Resilience

Retail systems are constantly changing and, more or less successfully, adapting themselves to competitive and technological challenges and market pressures, so the adaptive resilience perspective was favored in the development of the concept of retail resilience [13,34,35,36]. This concept was applied to urban policy and planning for retail resilience [27,37,38,39] and to evaluate the performance of UK town centers to the shock of the Global Financial Crisis by Wrigley and Dolega [40] which suggest a movement of ‘bounce forward’ within a dynamic and evolutionary process of the high street evolution, rather than ‘bounce back’ to the preshock configuration. Moreover, some disaster management studies show that people often do not wish to move to the previous condition; they rather prefer to move forward to a new, better one [41]. Some literature assigns this type of reading to the conservative nature of resilience [42,43,44] or the apolitical ecological resilience thinking which tends to perpetuate an established and unjust status quo and social processes at the expense of social transformation [45], once they do not question resilience “of what, to what and at what scales” [46].

Resilience is a multiscale concept that can be applied to a firm or to an economic sector. Rousseau [47] looked for the elements that could help to understand the resilience of the stores founded in Lisbon before 1915. Ntounis et al. [48] presented a composite score of business’ resilience with which it is possible to oppose the less resilient categories, food and beverage, retail trade, to the more resilient ones. From the spatial perspective, one may study the retail system of one region or city, or the commercial offer of a specific area, normally the town center or the district main shopping street.

After looking at the retail system at city level [49], in this text we perform a two scales analysis, focusing on the retail change of the commercial fabric of the city center and on a specific retail format, a traditional market also located in the central city, to show how the evolution of both come from the same policy will of rehabilitation and enhancing urban retail for city resilience and sustainability.

Accepting that the resilience of a commercial area depends on its ability to adapt to changes, crises or shocks without failing to perform its functions in a sustainable way, there are three considerations to have in mind. The first refers to the functions of retail within a city. It is common to underline the economic, social and urbanistic functions [50] that must guarantee the mostly private exchange of goods and services in an efficient manner, and the public good function trying to equilibrate profit making and public service [36,51]. The second points to the way to do it. In answering to a wide range of needs from different types of people and businesses, commercial systems (retail and services) must respect the dimensions of sustainability. Finally, the resilience of an area does not imply keeping the same characteristics because society is dynamic, and both the people demands and the way to deliver them change.

In contemporary societies, the drive of competitiveness and attraction to overcome the process of decline explains the rehabilitation of town centers and retail systems in response to external shocks such as out-of-town shopping, online sales, economic crisis or physical obsolescence by reposition, redefining the strategic priorities to attract new customers, reinventing themselves, reorienting their offer, focusing on the visitor’s economy, leisure or convenience, being an example of retail adaptive resilience [33,52,53] and a sign of urban resilience as a whole.

2.3. Sustainability

First presented in 1980 in the United Nations and in the World Wildlife Fund reports, ‘sustainability’ did not attract general attention until the publication of The World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED) report known as the Brundtland Report, in 1987. This report claims that for the development of a given territory to be considered sustainable, three dimensions (natural environment, social and economic conditions) and their interfaces (viability, equity and livability) need to be considered. The idea of sustainable development has been integrated the policy debates all over the world since the Earth Summit Conference in Rio (1992), which underlines the potential of policy action to achieve sustainable development.

Urban sustainability has been associated with preserving balanced retail systems set in diverse facilities and shopping environments [54,55,56] that are able to respond efficiently to the needs, wants and desires of different types of consumers. Cities with an efficient network of centers that deliver goods and services to the vicinity should be more sustainable than those without such a network.

2.4. Similarities and Differences Between Resilience and Sustainability

In 2018, two literature reviews discuss the concepts of urban (or city) resilience and urban (or city) sustainability. Zhang and Li [18] found about 950 papers (272 on urban or city resilience and 679 on urban or city sustainability) since 1968, while Rogov and Rozenblat [57] treated the Scopus data base, since 1973, and identified 800 articles.

With the wide dissemination of the concepts, both in the academia and the media, and the attempts for its operationalization by political authorities and organizations, we witnessed a conceptual diversification and enlargement of research perspectives, sometimes an overlap between the two concepts which threatens to weaken both [32,44,46]. They present similarities but also differences as Meerow and Newell [58] deeply explains.

Both resilience and sustainability are multidimensional as they deal with the three conditional dimensions required for a sustainable development of a place, the natural environment, the economic, and the social realms. Both concepts are multiscale, as one founds studies from one unit (building, firm, shop) to the global scale, passing through the neighborhood, the city and the region, naturally with different aims and focus, as Zhang and Li [18] evidence. The scale of analysis condition the topic in the analysis. So, Rogov and Rozenblat [57] show that the urban resilience papers tend to focus the local level and topics connected with ecology, such as the consequences of natural disasters; while in the regional resilience texts, economic aspects of external origin dominate. Some authors, such as Kärrholm [59], claim that the relationship of retail spaces with urban agglomerations must be seen at regional rather than city-level, because of the different size of catchment areas. We agree with this vision because we study a city center of a capital city which has, at least, a regional catchment area. It is also important to underline that we privilege the economic and social challenges, instead of the threats that arise from risks of natural origin.

Other authors point to differences in both concepts, associated with the temporal dimension and the threats and crisis involved. Engineering and ecological resilience studies tend to see resilience as problem-solving and short term oriented, therefore claiming that resilience would be more associated with management and civil defense, while sustainability with planning [60]. In fact, most definitions of resilience refer to the adaptation capacity of the system to keep working, following the same path or through the design of a new one. In the opposite, sustainability is considered a normative concept that implies transformation, offering visions of a desirable future, setting goals to be achieved in a certain period. One good example is the Sustainable Development Goals set by the United Nations, in 2015. Although sustainability may have a dimension implicating the behavior of individuals and organizations, in order to reduce their footprints, it is set in the context of long-term strategies related to a process of system’s transformation oriented by planning, duality noticed by Rogov and Rozenblat [57], and Redman [61], among others. In the same way, resilience also requires a strategy, organization and individual commitment to strengthen capacities and forces, not only for short-term response but also in the long-term adaptation [62]. When both concepts integrate spatial planning and urban management, they reinforce each other.

Chmutima et al. [63] underline the evolution of the practice of resilience from a governmental concept towards public responsibility with communities’ and stakeholder’s involvement. The proximity of the concepts when translated in collective practices points to the importance of governance to achieve the resilience and sustainability goals [64].

3. Sustainability and Resilience in Urban Retail Policy

The evolution of the relationship between retail and urban policy has been towards a greater connection. The shift from urban retail policies only focused on the regulation of the industry to a contemporary understanding of retail as a fundamental element of urban development has led to its greater incorporation in spatial planning. In the current phase of entrepreneurial management of cities and growth of tourism in which cities assert themselves as commodities, retail has proved to be fundamental to consolidate the new urban strategies.

After the mid-20th century, the sprawl that characterizes the outward expansion of cities, new patterns of retail location and decline of city centers mark the transition to a ‘modern’ car-based society. The first attempts at linking retail policy and urban planning emerge, giving emphasis on an efficient distribution of retail centers based upon central place theory, at that time adapted by Berry and Garrison [65] to the regional and city scales [66]. These principles kept going into land use planning, often in a more open and flexible application, aligned with the neoliberal ideas that spread in several countries. However, the meaning attributed to the ‘best location’ for a store had changed and is now perceived much more than a mere physical site and its accessibility, to include landscape and livability [67], in addition to symbolic connotations [68,69].

By the end of the 20th century, cities were struggling with urbanistic problems in the center and in the periphery, serious financial crises and job shortages. From an environmental point of view, this period was marked by energy crises and greater visibility of risks in urban areas. At the same time, there was an increase in environmental awareness and the need to build smart and sustainable cities, with more responsible and participatory citizens. From a social point of view, the challenges were centered on building inclusive cities where citizens had equal opportunities in the access to services and greater participation in collective decisions [70]. In 1993, the European Commission launched the European Sustainable Cities Program which identifies a set of principles to be respected in setting goals aimed at urban sustainability and highlights the need for the integration of policies, cooperation and partnership between actors, followed by progressive deeper and enlarged agreements towards the objectives of sustainability and cohesion.

The protection of the environment emerged as key factor for retail development control in France (Loi Raffarin, and Le Pacte de Relance pour la Ville, both from 1996). The same happened in the UK where one also finds new concerns in policy such as the quest for sustainability, the focus on regeneration and the need to eradicate social exclusion [71]. The new emphasis on the town center as the appropriate place for retail development led to the Town Center First policy in 1996, and the 4As (attraction, amenity, action and accessibility) guide for the vitality and viability of town centers [72]. Likewise, the environment comes to the front of the policy discourse in Finland, although the economic concerns on town center vitality, plus a possible oversupply of retail space came close by [73].

It is also important to highlight the idea of sustainability in terms of recycling or (re)use of the built environment related with the retail activity. The need to adapt to a new use, instead of demolition of industrial buildings, traditional markets, even some malls [74,75,76], derelict and functionally dead is the object of discussion and (re)investment. Big structures, often with a very interesting architecture, traditional markets are turning obsolete in many cities and object of innovative actions of revitalization and rehabilitation, normally also targeting its better connection with the district in which they are located.

The concern with resilience is more recent than the concept of sustainability in urban planning and retail policy, and it was also fostered by international organizations such as the UN. Initially linked to disaster risk management focused on emergency events, it implied the reorganization of the services of civil defense. Growth and the diversity of risks in urban areas often require a shift from the conservative mindset that maintain the status quo to perspectives that embrace change to enhance the overall performance of the system through a transformative adaptation, the combination of short-term response and long-term adaptation strategies, as already mentioned.

Besides changes in the way of doing, resilience thinking in urban retail is very much related with both sustainability and the territorial dimension. Literature on urban retail change and policy let us believe that from the urban retail perspective, the resilience idea works better when focused in retail areas and is quite interconnected with sustainability. From one side, it is not possible to think of a resilient city or district that is not sustainable in the long term. From the other, the requirements to change planning ways of doing to include the aims of sustainability and resilience thinking are very similar. In fact, both in the EU documents as in the literature, either on the experiences applied in Portugal in the 1990s and 2000s, to assure the sustainable development of cities and regions [77], or on the requirements to adopt resilience thinking in planning [62], one finds the need of coordination (between sectoral, spatial and temporal decisions or programs and between different levels of government), the necessity of communication, participation and citizen engagement in the process and the interest in the participation of the private sector.

Progressively, planning goals become more clearly related with sustainable economic growth and resilience, trying to enhance the viability and vitality of town centers as important places for local economies and communities. The evolution of retail policies showed the importance of public support to strengthen the resilience of town centers, and their contribution for sustainability, preventing sprawl and promoting forms of soft mobility, in favor of proximity [78,79]. Both discourse and practice of local authorities was increasingly directed towards city center revitalization with a special focus on physical improvements aiming beautification and comfort with pedestrian precincts and underground parking, safe and clean environments [71,80]. Moreover, we also witness some transformation of the stores to mix entertainment, tourism and the satisfaction of daily needs in forms called ‘funshopping or retailtainment’ [81], sometimes around the entrepreneurial exploitation of the consumption of culture and image [68], a whole set of initiatives aiming to attract more people and potential buyers.

Contemporary policy and management trends also show a better acknowledgement for the multidimensional characteristics and the richness of town center diversity, along with a claim for more systemic and holistic views of retail planning and town center management [53,82]. These ideas make use of both strategic planning, and collaborative models of planning and governance, [79,83,84,85] in which local business associations aiming for local improvements elevate in many cities around the world, since the 1980s, in new forms of urban governance. In a context of lacking financial resources from local authorities and a gap in coordination between authorities from different levels and different sectors, town center management schemes spread as a best practice to put in practice the town center vitality and viability goal [86,87,88,89] by engaging local retailers with other public and private stakeholders. Initially devised as an informal approach to partnership governance, in the last few years, one has witnessed the rise of more formal projects, such as business improvement districts (BIDs), whose main source of funding relies on the compulsory payment of a tax by existent businesses in a given area.

A Close Look to Portuguese Policies

Since the 1990s, concerns about sustainable growth have also been part of policies for cities and regions in Portugal. EU membership (1986) was important in boosting the territorial policies that benefited from European programs, the exchange of experiences and the progressive concertation of these policies until the approval of the Territorial Agenda, in 2007, which enshrined territorial cohesion as the third pillar of the cohesion policy, binding the priorities of a growth that must be smart, sustainable and inclusive, as well as resilient.

1994 is a milestone with both the creation of a program to support the consolidation of the urban system [90], through the strengthening of a network of medium-sized cities (PROSIURB–National program for consolidation of the national urban system), and the participation of neighborhoods with several problems of exclusion, in the EU Program URBAN. However, the evaluation made to the strategic plans of the cities covered by the PROSIURB showed that sustainability was not a concern neither a main aim of the designed strategy [91]. The economic component was at the center of concerns and appeared as a pivotal element due to its role in job creation and stability. The participation and involvement of civil society in planning and defining strategies was also weak.

The concerns with housing conditions were behind several programs focused on the deprived neighborhoods and urban rehabilitation initiatives which benefited from measures and funding, sometimes framed by comprehensive programs to enhance cities, until urban rehabilitation is the subject of a special legal regime, in 2009. This includes several components aimed at facilitating and stimulating the initiative of rehabilitation of properties by their owners.

With the entry into the 21st century, environmental issues are more valued as an element of quality of life, including the creation and conservation of green spaces, the preservation of the built environment and the ‘character’ of the historic city centers, the requalification of waterfronts, changes in urban mobility and reforms in deprived neighborhoods, in a more embracing view of sustainability and resilience that also recognizes the advantage of sharing responsibilities in its application. These concerns are very present in the policy called POLIS XXI (2006–2013), which was in favor of the multidimensionality and innovation of the answers, besides accepting an experimental character [92]. Urban regeneration attracted the larger part of the budget. Within POLIS XXI, between 2007 and 2013, 28 projects have been approved in the Lisbon metropolitan area, although the achievement was below what was expected, as Barata-Salgueiro et al. [70] explain. Around one-third of the actions went to the waterfront’s regeneration. It is noteworthy for the volume of the works and relevance for the city, the one in the central Lisbon riverfront.

In the last 30 years, the history of public measures to support retail in Portugal is also related with EU funds. In a first moment (1989 to 1992), one program was designed, and financial support was provided to retail firms, aiming to improve their modernization and competitiveness. In a second moment, the increasing diversity and dissemination of store formats and concerns with environmental questions and town planning explain both the publication of laws aiming to constrain the out-of-town retail developments, and the redesign of the public programs to support retail, in order to strengthen the relationship between retail urbanism and urban planning [56,93,94,95], within an attitude of positive discrimination of traditional retail and service centers and their commercial fabric [96]. In this period, a second and third program (1994–2008) were implemented, involving the ‘special projects of commercial urbanism’, which have a spatial dimension, as they specifically focus on the central areas of cities. Therefore, the focus shifted from the support to isolate shops, regardless of their location, to the support of shops only if they were located within a delimited area, usually the high street. In addition to retail firms, these programs provided funds for municipalities to carry out some improvements, mainly in public spaces, and for retail associations to develop marketing campaigns, as well as other initiatives.

The shift of the focus means a close integration of retail into the urban planning with the revitalization of high streets, in the form of retail urbanism aiming for both the development of the retail function and the well-being of people [97,98]. With increasing competition between places and the need to offer unique and differentiating features, entrepreneurial urban management has also begun to use stores as a cultural resource, a distinctive sign of the city’s identity, an instrument to enhance the attractiveness of the city for tourists, other users and investors.

4. Rehabilitation and Retail in the Lisbon City Center

Lisbon is both a metropolitan area of 2.8 million inhabitants located in the two margins of the mouth of the Tagus river, covering 3128 km2 divided by 18 municipalities, and a municipality with 84 km2 and 550,000 inhabitants. The population of the Lisbon municipality, henceforth called the city of Lisbon, reached its peak in 1981 with 808,000 inhabitants. Lisbon lost 260,000 residents (32%) between 1981 and 2011 but some areas of the historical center lost almost 45%. The city’s resident loss is due to two interconnected processes: the tertiarization of the city core and the suburban growth, besides population-ageing. Furthermore, the inner city has suffered a deep decline in consequence of the crisis of the industrial model in the 1980s, with abandonment of industrial sites, lack of maintenance of buildings and structures and the displacement of offices, namely banks, from the traditional city center to the new office districts.

From the beginning of the 1990s (City’s Strategic Plan and Master Plan, respectively, from 1992 and 1994) there are many documents of policy at the scale of the whole city, specific neighborhoods or special areas where the aims of sustainability and resilience guide the proposals, emphasizing the need to increase the competitiveness of the city’s economic base to overcome existing needs in terms of housing and the requalification of public spaces, besides changes in transports and mobility to improve the quality of life of residents.

We will just refer two examples at the city level and one focusing in the studied area because they are directly connected with the aims of this paper. The first is the municipal master plan of 2012 because it gives a definition of urban resilience as the capacity of the system or the community to adapt to events, resisting or modifying to keep the structure working at an acceptable level [99]. The other is the Strategy for Lisbon Rehabilitation 2011–2024 [100], due to the strong relation we found between rehabilitation and retail change. This document introduces a new paradigm for action that aims to ensure investment in rehabilitation is attractive for private developers and also adopts the three R’s philosophy: the reuse of empty buildings, the rehabilitation of those in bad conditions and the requalification of the consolidated areas.

The municipal capacity to orient retail development is limited, although urban policy may create conditions to enhance the ‘reinvention’ and the resilience of the offer, by promoting rehabilitation, improving the quality of public spaces and fostering functional diversity, namely cultural, leisure and tourist venues.

The sharp dereliction of the central core and the will to improve tourism led the municipality to develop a detailed land-use plan for Baixa. Approved in 2010, it has sustainable and resilience concerns with the promotion of the residential function and the willingness to “increase the creation of new commercial areas, of leisure and tourist functions, to value the riverfront and the main plaza, (…) to guarantee the cyclical continuity along the river bank; revitalize the area with the increase in cultural functions and the increase in the provision of qualified public spaces and walking paths” [99]. This plan recommends a concentration of retail in certain streets to articulate with the new mobility facilities, aiming to minimize the effect of the different topographical levels in the area. There are also important measures for public space and noise reduction aiming to reinforce the historical and heritage image of the area, to promote soft mobility and the requalification of the river front. Following these ideas, some structural works were performed which created the conditions to attract investment in building rehabilitation. In a few years, the rehabilitation of existent buildings already exceeded the new construction in the city, in a process that favored gentrification and, at the same time, boosted tourism growth. The number of passengers in the airport increased from 14 million in 2010 to 26.7 million in 2017.

The environmental concerns, and the intention to enhance the riverbank, converged on a set of works between 2009 and 2015. We must highlight the meaningful transformation of the large square near the Tagus river which included the removal of most of the motorized transit, the occupations of the arcades with cafes and restaurants, and the licensing of a five-star hotel. To the east, the new cruise terminal has been built more recently and other improvements continue to be made. To the west, several works were completed in a rationale of landscaping quality, functional changes including the old market and reordering of mobility, trying to harmonize low car speed with soft mobilities, new green and leisure spaces close to the river.

In the context of the expansion of tourism, of the leisure economy and of the consumption of experiences, the use of culture grew as a resource in the city’s development path encouraging the opening of innovative museums and other cultural venues in the city center. In the same way, special old stores mostly located in downtown were valued as cultural and heritage elements, and were the target of a municipal program on historical shops to give them some support and visibility when their continuity was threatened by the new leasing law [101].

Although we will devote ourselves to retail change, the effects of the policies were more comprehensive and had direct and indirect effects in other sectors. The hotel sector is one of these sectors. In 1989, Lisbon had 34 hotels officially ranked with three stars or more. Between 1991 and 1998, the year Lisbon hosted the International Exhibition (Expo 98), 19 more were built. The new openings accelerated after that event, showing the results of the strategy of internationalization and tourism branding of the city. After 2013, the process sped-up again reaching 177 at the end of 2019. In the last decade there was an intense pressure from new hotels within the city main center where 83% of the hotels are located. Within this enlarged center, Baixa-Chiado district represents 24%, mainly outcome of building rehabilitation.

In the inner city of Lisbon, urban regeneration, touristification and gentrification processes were strongly under way until the beginning of 2020 [102,103,104,105]. New residents arrived, particularly young adults with university education, and tourists. The retail landscape has also changed.

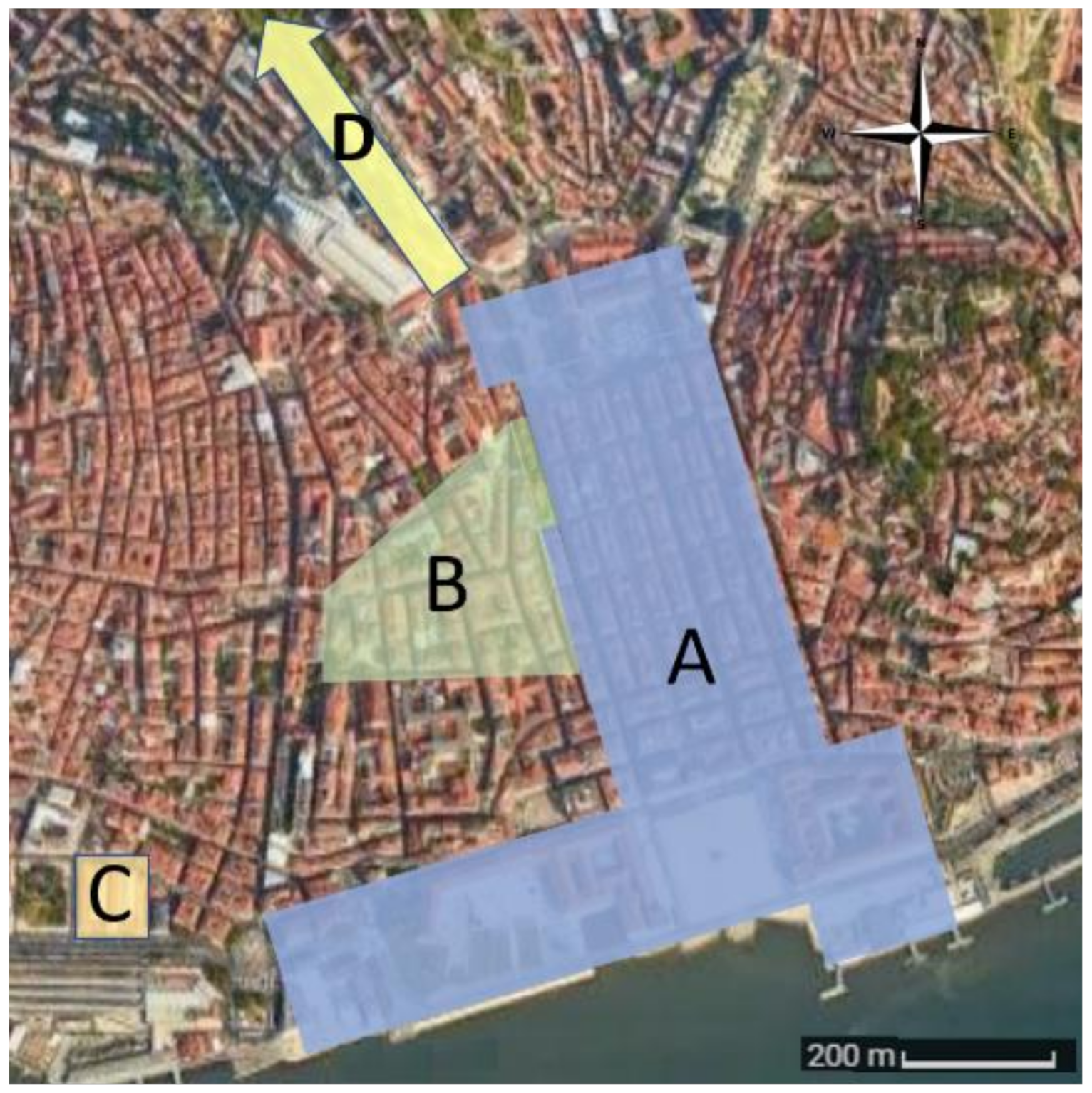

The traditional city center (Baixa-Chiado district, Figure 2) keeps the main characteristics of a city retail core, despite the observed changes in the functional composition and the retail structure. It is possible to distinguish two subareas in the district because of their different evolution in past decades. Chiado suffered a huge fire in 1988, so part of this area was rebuilt before the aforementioned plan and quickly began to experience some residential and retail gentrification. Many traditional shops had closed and disappeared. Some of them carried valuable heritage and played an important role in the identity of the place, shaping its specificity. At the same time, what Zukin et al. [106] called ‘entrepreneurial retail capital’ (boutiques) started appearing, closely followed by ‘corporate retail capital’ (chain stores) and the retail tenant mix also changed, with a substantial growth of stores associated with leisure, such as restaurants, pastries and similar retail spaces, and their terraces now occupy a large part of the main high streets.

Figure 2.

Lisbon city center. Source: authors (2020) on Google. Legend: A—Baixa; B—Chiado; C—Time Out Market; D—Liberdade avenue.

Retail change benefited and was boosted from the rehabilitation measures but, at the same time, contributed to their success, in a dialectic process essential to understand the different meanings of urban space transformation [107]. Chiado is an example of such relation, as some argue that the current vitality and viability of the area is due to a retail-led urban regeneration project. The main flagship of the improvement of Chiado is the opening of Armazéns do Chiado, a shopping center that replaced an ancient department store burned in the mentioned fire. This shopping center was inaugurated in October 1999 with three anchors, FNAC, a fashion superstore from a Spanish chain CorteFiel and a sport’s equipment shop, Sport Zone. Quickly, Armazéns do Chiado became the anchor for the increasing vitality of the area, transforming Chiado into a meeting point for the youth and less young people.

The surveys of the main streets on Baixa-Chiado show that the number of retail units and related services in the beginning of 2020 is quite similar to the one in 2007, which points to the general resilience of the area, despite changes in its functional composition; it also points to some differences between the two subareas that should be underlined. Some trends are observed in the center’s retail and services complex in terms of the size and composition of the commercial fabric.

4.1. Size of the Commercial Fabric

The first trend is the reduction of the number of stores in Baixa and the opposite evolution in Chiado. Between 2007 and 2020, Chiado increased the size of the commercial fabric by 22.2% while Baixa lost 17.5% (Table 1). The number of stores closed in Chiado is smaller than the new openings, while in Baixa it is the opposite. In part, this difference is due to the rhythm of requalification works in both areas, where they are much more advanced in Chiado. Overall, the rehabilitation works are still visible now with a significant pace; during the fieldwork, 20 retail spaces were suffering physical renovation (7.7% of those in activity) and mainly located in Baixa.

Table 1.

Some features of the commercial fabric in Baixa and Chiado.

In 2007, Chiado was already a livable central area with a diversified retail offer, meeting and leisure spaces. Its vitality explains the important increase in the number of retail units, mostly until 2015, while Baixa was still losing. However, in both subareas the retail decrease is higher in the last 5 years which may point to a turning point, only possible to confirm in the coming years.

4.2. Composition of the Commercial Fabric

The second change to register refers to the composition of the commercial fabric, namely the growing relevance of some retail typologies, the entrepreneurial characteristics of existent retail businesses and the specialization of some shopping areas.

4.2.1. Evolution of the Tenant Mix

Until 2020 almost all retail categories lost representation while restaurants and other food and beverages spaces register a huge increase, significantly pronounced in the last 5 years.

In 2007, the area shows a dominance of personal goods (clothing, jewelry, accessories), followed by goods and services of culture and leisure. Household goods, health and beauty, as well as restaurants and other food and beverages establishments emerge afterwards with a similar weight, which is in line with the composition of a traditional city center commercial fabric (Table 2).

Table 2.

Evolution of the commercial fabric of Baixa and Chiado.

In 2020, personal goods still occupy the first place, with food and beverages establishments in second, followed by culture and leisure goods. Health and beauty and nonspecialized stores occupy the fourth position. Household goods lost position. This change is articulated with two other transformations: homogenization of the commercial fabric and shift in customers’ target.

The disappearance of traditional shops selling personal goods, household goods and professional equipment and services gave place to stores in line with new lifestyles and concerns. Occasionally, more than the retail typologies, the change refers to the type of product sold. The appearance of more sophisticated shops, usually designed as concept stores, selling clothing, handmade and design products, especially in Chiado, is a good example of this evolution. In the same way, one witnesses the opening of stores from sportswear, health and beauty goods, or even the presence of a Bio supermarket and a gym, which must be seen as signs of new lifestyles and enlarged concerns with people’s appearance, healthier food and life styles, besides the construction of identities, using goods as a resource [11].

Given the importance of the tourism industry to the urban economy, the modification of stores is also aligned with the needs of tourists. This is reflected in the important increase in the number of restaurants and coffee shops and in the modernization of the stores selling household goods, aiming simultaneously at national clients and tourists. The same trend is seen in the eating places which sell traditional or pseudo traditional pastries.

Another example of this evolution is the nonspecialized retail, practically nonexistent in 2007 and currently with a significant number of units, mainly in Baixa. Owned by immigrants from Asian countries, especially Bangladesh, Nepal and India, these retail units that aim foreigners and sell souvenirs and scrambled merchandise are very similar to the ones that are expected to be found in all tourist cities around the world.

4.2.2. Entrepreneurial Features

Another trend of the retail change in Lisbon city center is the increase of chains or brands, in retail as in food and beverage spaces. Particularly relevant in Chiado but also important in Baixa, new stores are usually associated with a franchise or part of a national or international chain. This evolution contradicts the model of retail modernization and resilience in a shopping district based mostly on the physical transformation of the shops and its equipment.

As Table 1 shows, in 2015, the percentage of chain stores already reached almost a third of the premises with a big difference between the two subareas. In 2020, there has been a stabilization, although in Chiado, one even saw a slight increase. Related with the rotation of the spaces, the retail landscape changes from a network of small, unique shops to a more standardized type with units belonging to chains, either with national or international origin, which accentuates the tension between homogenization and differentiation, in the current global context [108]. Without appreciable variation in the last 5 years, the international chains largely dominate, being much more important in Chiado. This confirms the importance of foreign investment in Chiado rehabilitation, namely in retail.

We must also be aware of antagonistic perspectives by the different types of retailers regarding the evaluation of the Baixa–Chiado change. On the one hand, new businesses from large international chains benefit from the evolution of the area into a leisure and consumption destination. Under the same perspective, some national chains were also able to adapt and assume a prominent role in that process, expanding their businesses through the acquisition or rental of new spaces. On the other hand, we may find some independent retailers that still represent most of retail spaces, especially the ones that rent the space and are under pressure for displacement due to the changes in the leasing law. According to the interviewees, most of them are in the area for several decades and their business model is traditionally based on clients from the city and region. Even with modifications, several of these businesses can hardly adjust to comply with the necessary money flow and profit that is necessary to handle the increasing valorization of the area. This affects home fabric stores but also jewelries, and others. Other stores, such as drugstores, complain with the decrease in the number of customers due to the reduction of employees in the area, especially in Baixa. Here the decrease of retail stores, in a certain way, happened after public services and financial institutions left the district.

In 2015, the municipality launched the already mentioned program to support some of the old stores. Overall, it recognizes their importance for the memory and heritage of the area. Despite some positive results, the effectiveness of the program is low in the sense it did not prevent the closure or the displacement of the stores in a medium term, but just postponed it. An interviewee, whose store fits this context and is a member of an association of retailers of Baixa, showed his concern as he asserted that a significant number of stores were in the same situation. He further argued that a set of complementary measures are required in order to preserve the commercial diversity of the area, a feature that is identified in the literature as key for the resilience of urban retail systems.

If most of the retailers recognize that the secret for the success and resilience is the quality of the offer and the ability to understand the trends and adjust to them, better if in anticipation, it is also important to realize that some shops don’t have the motivation or the conditions to do it. So, some stakeholders told us about the advantage to have an organization to give orientation and support for old retailers or new investors interested in starting a new business, within a strategy for the whole area. They recognize the good collaboration that exists between the municipality and the retailer’s association, but many retailers are not members of the association and they do not have legal support to perform this function. There are several local associations in the city, at street or neighborhood level which organize events in special days (in Baixa, the Christmas fair) that attract people, but they feel the necessity of a more organized and ‘professional’ structure.

4.2.3. The Specialization of Shopping Districts

Besides the growing specialization of the retail fabric of Baixa-Chiado, aligned with the expansion of the tourism industry, it is worth mentioning the changes in two other areas in close proximity with the considered core, that can be viewed as part of an enlarged city center. Towards the north of Baixa, a luxury strip has consolidated in Liberdade avenue, mostly with international well-known luxury brands in fashion and accessories [109]. This avenue was known by its hotels and prestigious office buildings; the rehabilitation works not only reinforce this previous occupation but also the offer of high standard apartment buildings and luxury shops. The information on the price of real estate points to the high level of buyers, eventually some foreigners using the facilities of the so-called golden visa and nonpermanent residents, while in the shops, wealthy clients, often tourists from Brazil, Angola and Eastern European countries are side by side with some rich nationals.

A little further to the west of the city’s main square, close to the transport interface, lies an old market hall (Mercado da Ribeira) from 1882, rebuilt in the 1920s with a remarkable iron architecture. It worked as wholesale and retail market for the city until July 2000, when a big wholesale complex opened in the outskirts. In the last decades of the 20th century, the market suffered from disinvestment from the municipality who owns the space, and vacancy rates increased, such as in other traditional markets [110]. This devaluation decreased its value, which in combination with its symbolic and architectural importance, endowed this equipment with a significant rent gap. This evolution is similar in a wide array of countries world-wide, leading several researchers to study the rehabilitation of traditional markets using gentrification theory [111,112,113].

The municipal strategy for markets implies the rehabilitation of the buildings and an increase of its attractiveness by installing anchors. A total of two main types of anchors have been identified, the opening of a supermarket chain and the creation of a food court. The first is usually applied in residential districts, while the food court model is used in areas with tourism. This last example was applied in Ribeira market, now renamed as Time Out Market.

In January 2012, a private company was granted with the concession right to explore the market for 20 years, supporting the rehabilitation costs. This company was the same that had the right for the Portuguese version of the Time Out magazine. This was the origin of the rebranding of Ribeira market to Time Out Market. After adaptation works, the space opened in 2014 with a ‘gourmet’ food court with several and diverse types of cuisine, including renowned chefs and spaces with typical Portuguese goods, including wine, oil, canned fish, but also crafts (Table 3). There is a purposeful rotation in the occupation of spaces to introduce novelty.

Table 3.

The occupation of Time Out Market.

The innovation of the Time Out concept in relation to traditional food courts is both on the valorization of a high-quality offer and on the articulation with the magazine. The magazine’s writers must observe the offer of the city to recommend places and attractions. What the managers do is to bring to the market the best ideas and businesses for a certain period (from 1 week to 3 years) so people could find, under the same roof, the best of the magazine hits or as referred by a Time Out director:

“Our concept is to create a magazine in 3D, i.e., to make this huge and fantastic building a place where the visitor has the same kind of experience that the reader has while browsing our magazine”(Ruas, 2014 in Guimarães [114])

In 2014, Time Out Market was already the second biggest commercial attraction in Lisbon in TripAdvisor, right after the Oceanarium. For the managers of Time Out, the biggest advantages of the market are the location, the accessibility by public transports, the position in the triangle Baixa–Chiado–Sodré Interface, the architecture of the building, the traditional market selling fresh products and being ‘the most innovative media project in the world’ [115]. The municipality also considered the rehabilitation completed by Time Out a success, measured by the occupancy rate, which increased from 65% in 2012 to 94% in only 3 years.

Overall, the rehabilitation of Ribeira market is the consolidation of the strategy to (re)use the built environment, as discussed previously. However, the rebranded Time Out Market went from being a market whose rehabilitation results from experiences in other markets to be a model of a successful business, transferable to other cities, such as Chicago, New York, Montreal, London or Prague. Resulting from a benchmarking analysis, it culminated in being a mechanism of capital reproduction.

The transformation happening in the markets denounces what Gonzalez and Waley [111] call the ‘commodification of the market experience’. The disinvestment and marginalization, coupled with the often very central and strategic location of marketplaces in cities, has driven marketplaces towards a ‘gentrification frontier’ [76]. In fact, in Lisbon, the current transformations are narrowing the functions of the markets turning these retail precincts into places for leisure and consumption experiences for middle and upper classes and tourists [114].

5. Discussion and Concluding Remarks

Recently, urban resilience and urban sustainability entered the discourse of urban policies. Simultaneously, neoliberal tendencies of government and shared forms of governance have dominated much of the world. The retail sector is influenced by the different planning and legal traditions of each country, however the evolution of retail in the last decades is deeply affected by the increasing integration of local and national economies into the global economy.

In this article, we focused on retail and aimed to unfold how urban policy, committed to a resilient and sustainable city, dealt with the challenges enhancing the vitality of the city center. Our empirical study was developed in the city center of Lisbon, which suffered decline with the transition to a postindustrial economic base and more recently to a new one based on tourism and leisure economy. Our findings showed the important role played by the public sector at all levels of government, the deepness of the links between public initiatives and private entrepreneurship and their impacts in the image of the city and the vitality of the core.

The local administration was particularly active through several planning documents that triggered and unlocked the transformations in the inner city over the last decade. The first strategic plan for the city (1992) paved the way for the rise of the tourism industry and other documents recognized the relevance of the private sector in the fulfilment of this endeavor and in the rehabilitation of the built environment.

The rehabilitation procedures enabled by the detailed plan and other public measures, such as the liberalization of the rental law, incentives to expand cultural facilities in Lisbon city center, municipal investments on mobility and the rehabilitation of specific areas in the riverbank and other public spaces, in combination with the growing number of tourists, created the necessary conditions for the area to be considered attractive for private investors, overcoming the rent gap formed by years of dereliction and abandonment.

At a national level, some laws were approved to give incentives to international residents and investments. The facilities given by the special regime of urban rehabilitation and the changes in the urban lease law towards the liberalization of the rental market, converged in fostering the rehabilitation of central cities, despite many critics.

Retail is a part of this equation, as it contributes to increase the vitality of the studied area. The commercial fabric suffered a deep renovation, even though with differences between the two subareas of the district due to disparities in the pace of rehabilitation of Baixa and Chiado. In general, there is a clear evolution from shopping space strictu sensu to consumption spaces polarized by culture and entertainment, with the change in occupancy from retail to restaurants, cafés and other eating spaces, beyond the increase of cultural venues and public spaces open to the river. There was also a (re)composition of the retail offer to answer new lifestyles, more concerned with the personal care, appearance, and health. From the organizational perspective, the increasing presence of chains and brands, puts into question the identity of the city core in favor of a more standard international retailscape which may threat its resilience.

However, with the decrease in the number of retail units and the growth of services connected with leisure and consumption, the core once again has the multifunctionality that used to be its trademark, although with a different content. Banks and other corporate headquarters were relocated to new emerging office’s districts in the city or in the edge, and the new diversity of the tenant mix revolves around consumption functions. In European cities, despite the steady growth in the leisure sector, downtown areas have remained a regional comparison-shopping destination as Kickert and vom Hofe [116] observed when comparing The Hague and Detroit. Lisbon city center still is a comparison-shopping destination, although much weaker than it used to be. Furthermore, if many traditional retail units compose the character of the district, the new retail offer seeks to use in its benefit the heritage value that exists in the area. In this sense, retail is now merged with other elements representative of the local identity and is part of the strategy to sell history in a consumption environment [117]. The wide opening of several establishments devoted to sell specific traditional pastry, the rehabilitation of commercial spaces keeping historical elements both inside and on its façade and the rehabilitation of Time Out Market are examples of this evolution.

The focus on urban policy for the city-center enabled us to highlight how city government applied the ideas of resilience and sustainability and to argue that the transformation of retail structure was in line with the advocated strategic growth. Supported by a vision of urban resilience to overcome the decline of the city center and to meet the aims of sustainability, in which resilience does not imply the preservation of the same characteristics, as the evolution of the retail fabric shows, planning and other political practices enhanced a deep transformation of the area. In the timespan of a decade, the measures taken proved to foster some aspects important for the resilience and sustainability of the central city. Economically, there was a renewal of existent businesses; the environmental dimension was reinforced through the rehabilitation and qualification of public spaces with a clear bias in favor of pedestrian circulation and the reuse of buildings, such as the one that is now occupied with Time Out Market. Moreover, the city also gained several open spaces near the river, and the core turned to be again alive and used by residents and visitors.

However, other aspects are going in the opposite way, calling into question the effectiveness of the undertaken public policies in what concerns the fulfilment of all dimensions of sustainability. The transformation of the Lisbon city center has been made at the expense of an excessive dependence on tourism and transnational migrants, such as digital nomads, which sets several challenges. The first is social and relates with the nonaccomplishment of the planning goal to increase the proportion of residents and the exclusion of some groups to access the inner city, both due to the escalating housing prices and the change in retail supply. In fact, the rental or acquisition values of housing are unaffordable for most of the city inhabitants and the commercial fabric is more oriented towards tourism and some other types of lifestyles. The second is economic and concerns the risk that arises from an economy largely based on tourism and consumption. The urban works performed in Lisbon ended to serve best the interests of real estate and corporate capital accumulation, without the adequate social and economic precautions. As the recent COVID-19 pandemic showed, this option clearly jeopardizes the urban economy and the social sustainability in face of a crisis, in addition to threatening the city center’s own identity.

Looking back to the last decade, one must recognize the improvements made in the city center to design a path towards its resilience and sustainability; however, they must imply a greater diversity, more concerns with social and cultural dimensions of the urban life and more collaboration between stakeholders. If the economic theory warns about the excessive specialization of a territory, retailers could do better together with other businesses and the municipality should be able to find more comprehensive paths of growth that respond to residents and visitors, and keep the central city alive and interesting both to visit, to shop, to give money to businesses and even to live in. If sustainability goals are already accepted in planning and as a collective responsibility, resilience thinking is not so much shared; this points to the importance of resilience management, namely the necessary increase of public information and stakeholder’s initiatives that broaden the collaborative modes of urban space production and appropriation.

Author Contributions

Both authors contributed equally to all parts of the article. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia: Project “PHOENIX—Retail-Led Urban Regeneration and the New Forms of Governance”—PTDC/GES-URB/31878/2017.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bromley, R.D.F.; Thomas, C.J. The Retail Revolution, the Carless Shopper and Disadvantage. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 1993, 18, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Findlay, A.; Sparks, L. Literature Review: Policies Adopted to Support a Healthy Retail Sector and Retail-Led Regeneration and the Impact of Retail on the Regeneration of Town Centres and Local High Streets. 2009. Available online: https://dspace.stir.ac.uk/bitstream/1893/11857/1/Sparks_2009_Literature_review_main_report.pdf (accessed on 8 June 2020).

- Ozuduru, B.; Guldmann, J.M.; Duchemin, E.; Barroca, B.; Serre, D. Retail location and urban resilience: Towards a new framework for retail policy. SAPIENS–Surv. Perspect. Integr. Environ. Soc. 2013, 6, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Beaujeu-Garnier, J.; Delobez, A. La Géographie du Commerce; Masson: Paris, France, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Metton, A. Le Commerce Urbain Français; PUF: Paris, France, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Barata-Salgueiro, T. Novas Formas de Comércio. Finisterra, Revista Portuguesa de Geografia 1989, XXIV. Available online: http://revistas.rcaap.pt/finisterra/article/view/1944/1621 (accessed on 8 June 2020).

- Barata-Salgueiro, T. Do Comércio à Distribuição; Roteiro de uma Mudança; Celta: Oeiras, Portugal, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, R. Retail Planning Policies in Western Europe; Routledge: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Erkip, F.; Ozuduru, B.H. Retail development in Turkey: An account after two decades of shopping malls in the urban scene. Prog. Plan. 2015, 102, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrigley, N.; Lambiri, D. British High Streets: From Crisis to Recovery: A Comprehensive Review of the Evidence; University of Southampton: Southampton, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cachinho, H. Consumactor: Da condição do indivíduo na cidade pós-moderna. Finisterra Rev. Port. Geogr. 2006, 81, 33–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cachinho, H. Consumerscapes and the resilience assessment of urban retail systems. Cities 2014, 36, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barata-Salgueiro, T. The Resilience of Urban Retail Areas. In Retail Planning for the Resilient City. Consumption and Urban Regeneration; Barata-Salgueiro, T., Cachinho, H., Eds.; Centro de Estudos Geográficos: Lisbon, Portugal, 2011; pp. 19–44. [Google Scholar]

- Sharifi, A. Urban form resilience: A meso-scale analysis. Cities 2019, 93, 238–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, U. The Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity; Sage Publications: London, UK, 1992; (German original, 1986). [Google Scholar]

- Giddens, A. The Consequences of Modernity; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1990; (Portuguese translation: Celta Eds.: Oeiras, Portugal, 1992). [Google Scholar]

- Pu, B.; Qiu, Y. Emerging Trends and New Developments on Urban Resilience: A Bibliometric Perspective. Curr. Urban Stud. 2016, 4, 36–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, H. Urban resilience and urban sustainability: What we know and what do not know? Cities 2018, 72, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cain, S.A. The importance of ecological studies as a basis for land-use planning. Biol. Conserv. 1968, 1, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holling, C.S. Resilience and Stability of Ecological Systems. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1973, 4, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, R. Resilient regions in an uncertain world: Wishful thinking or a practical reality? Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2009, 3, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adger, W.N. Social and ecological resilience: Are they related? Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2000, 24, 347–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holling, C.S. Understanding the Complexity of Economic, Ecological, and Social Systems. Ecosystems 2001, 4, 390–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C. Resilience: The emergence of a perspective for social–ecological systems analyses. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2006, 16, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campanella, T.J. Urban Resilience and the Recovery of New Orleans. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2006, 72, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manyena, S.B. The concept of resilience revisited. Disasters 2006, 30, 434–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, F.; Summers, R. Planning for retail resilience: Comparing Edmonton and Portland. Cities 2016, 58, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendez, R. Ciudades y metáforas: Sobre el concepto de resiliencia urbana. Ciudad Territ. Estud. Territ.-CyTET 2012, 172, 215–231. [Google Scholar]

- Pike, A.; Dawley, S.; Tomaney, J. Resilience, adaptation and adaptability. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2010, 3, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmie, J.; Martin, R. Editor’s choice: The economic resilience of regions: Towards an evolutionary approach. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2010, 3, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R. Regional economic resilience, hysteresis and recessionary shocks. J. Econ. Geogr. 2011, 12, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoudi, S.; Shaw, K.; Haider, L.J.; Quinlan, A.E.; Peterson, G.D.; Wilkinson, C.; Fünfgeld, H.; McEvoy, D.; Porter, L. Resilience: A Bridging Concept or a Dead End? “Reframing” Resilience: Challenges for Planning Theory and Practice Interacting Traps: Resilience Assessment of a Pasture Management System in Northern Afghanistan Urban Resilience: What Does it Mean in Planning Practice? Resilience as a Useful Concept for Climate Change Adaptation? The Politics of Resilience for Planning: A Cautionary Note. Plan. Theory Pract. 2012, 13, 299–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolega, L.; Celińska-Janowicz, D. Retail resilience: A theoretical framework for understanding town centre dynamics. Stud. Reg. I Lokal. 2015 2015, 2, 8–31. [Google Scholar]

- Barata-Salgueiro, T.; Erkip, F. Retail planning and urban resilience—An introduction to the special issue. Cities 2014, 36, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kärrholm, M.; Nylund, K.; De La Fuente, P.P. Spatial resilience and urban planning: Addressing the interdependence of urban retail areas. Cities 2014, 36, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobson, J. Britain’s town centres: From resilience to transition. J. Urban Regen. Renew. 2015, 8, 347–355. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, J.R.; Chamusca, P. Urban policies, planning and retail resilience. Cities 2014, 36, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soumagne, J. Aménagement et Résilience du Commerce Urbain en France; L’Harmattan: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Guimarães, P.P.C. The resilience of shopping centres: An analysis of retail resilience strategies in Lisbon, Portugal. Morav. Geogr. Rep. 2018, 26, 160–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrigley, N.; Dolega, L. Resilience, Fragility, and Adaptation: New Evidence on the Performance of UK High Streets during Global Economic Crisis and its Policy Implications. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2011, 43, 2337–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendall, R.; Foster, K.A.; Cowell, M. Resilience and regions: Building understanding of the metaphor. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2010, 3, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, K. “Reframing” Resilience: Challenges for Planning Theory and Practice. Plan. Theory Pract. 2012, 13, 308–312. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph, J. Resilience as embedded neoliberalism: A governmentality approach. Resilience 2013, 1, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzo, B. Problematizing resilience: Implications for planning theory and practice. Cities 2015, 43, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, J.; Cooper, M. Genealogies of resilience. Secur. Dialogue 2011, 42, 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weichselgartner, J.; Kelman, I. Geographies of resilience: Challenges and opportunities of a descriptive concept. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2015, 39, 249–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, A.J. Resiliência do Comércio. As lojas centenárias de Lisboa; Principia: Cascais, Portugal, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ntounis, N.; Parker, C.; Saga, R.; Warnaby, G. High Street Business Resilience; Institute of Place Management: Manchester, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Barata-Salgueiro, T.; Cachinho, H. Retail Planning for the Resilient City: Consumption and Urban Regeneration; Centro de Estudos Geográficos: Lisbon, Portugal, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Barata-Salgueiro, T. Comércio e cidade. Econ. Prospect. 1998, II, 69–83. [Google Scholar]

- Ozuduru, B.H.; Varol, C.; Ercoskun, O.Y. Do shopping centers abate the resilience of shopping streets? The co-existence of both shopping venues in Ankara, Turkey. Cities 2014, 36, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, C.; Ntounis, N.; Millington, S.; Quin, S.; Castillo-Villar, F.R. Improving the vitality and viability of the UK High Street by 2020. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2017, 10, 310–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolega, L.; Lord, A.L. Exploring the geography of retail success and decline: A case study of the Liverpool City Region. Cities 2020, 96, 102456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office of the Deputy Prime Minister (ODPM). Planning Policy Statement 6: Planning for Town Centres (PPS6). Available online: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20080306201620/http://www.communities.gov.uk/documents/planningandbuilding/pdf/147399 (accessed on 10 July 2020).

- Department for Communities and Local Government. Planning Policy Statement 4: Planning for Sustainable Economic Growth; The Stationery Office: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cachinho, H.; Salgueiro, T.B. Os sistemas comerciais urbanos em tempos de turbulência: Vulnerabilidades e níveis de resiliência. Finisterra 2016, 51, 89–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogov, M.; Rozenblat, C. Urban Resilience Discourse Analysis: Towards a Multi-Level Approach to Cities. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meerow, S.; Newell, J.P. Urban resilience for whom, what, when, where, and why? Urban Geogr. 2019, 40, 309–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kärrholm, M. Retailising Space. Architecture, Retail and the Territorialisation of Public Space; Ashgate: Farnham, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, G.C.D.; Guibrunet, L. Assessing the ecological dimension of urban resilience and sustainability. Int. J. Urban Sustain. Dev. 2017, 9, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redman, C.L. Should Sustainability and Resilience Be Combined or Remain Distinct Pursuits? Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, A.; Yamagata, Y. Resilience-Oriented Urban Planning. In Resilience-Oriented Urban Planning-Theoretical and Empirical Insights; Yamagata, Y., Sharifi, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 3–27. [Google Scholar]

- Chmutina, K.; Lizarralde, G.; Dainty, A.R.; Bosher, L. Unpacking resilience policy discourse. Cities 2016, 58, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaans, M.; Waterhout, B. Building up resilience in cities worldwide—Rotterdam as participant in the 100 Resilient Cities Programme. Cities 2017, 61, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, B.J.; Garrison, W.L. Recent developments of central palace theory. Pap. Reg. Sci. 2005, 4, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspar, J. Centros de comércio e serviços na cidade de Lisboa. Finisterra, Revista Portuguesa de Geografia. 1975. Available online: http://revistas.rcaap.pt/finisterra/article/view/2311/1960 (accessed on 29 September 2020).

- Balsas, C.J. Measuring the livability of an urban centre: An exploratory study of key performance indicators. Plan. Pract. Res. 2004, 19, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Simone, L. Espacios de Consumo y Urbanismo de Retail: Construyendo la Ciudad del Consumo en Santiago de Chile. In Ciudad, Comercio Urbano y Consumo. Experiencias Desde LatinoAmerica y Europa; Gasca, J., Olivera, P., Eds.; Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México: Ciudad de México, México, 2017; pp. 99–116. [Google Scholar]

- De-Juan-Vigaray, M.D.; Seguí, A.I.E. Retailing, Consumers, and Territory: Trends of an Incipient Circular Model. Soc. Sci. 2019, 8, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barata-Salgueiro, T.; André, I.; Brito Henriques, E. A Política de Cidades em Portugal: Instrumentos, Realizações e Perspectivas. In Políticas Públicas, Economia e Sociedade. Contributos para a Definição de Políticas no Período 2014–2020; Neto, P., Manuel, M., Eds.; Nexo Literário: Alcochete, Portugal, 2015; pp. 49–82. [Google Scholar]

- Guy, C. Planning for Retail Development, a Critical View of the British Experience; Routledge: Oxon, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- URBED. Vital and Viable Town Centres: Meeting the Challenge; HMSO: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Yrjänä, L.; Rashidfarokhi, A.; Toivonen, S.; Viitanen, K. Looking at retail planning policy through a sustainability lens: Evidence from policy discourse in Finland. Land Use Policy 2018, 79, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, D.; Paiva, D. The death and life of shopping malls: An empirical investigation on the dead malls in Greater Lisbon. Int. Rev. Retail. Distrib. Consum. Res. 2017, 35, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, P.P.C. Shopping centres in decline: Analysis of demalling in Lisbon. Cities 2019, 87, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, S. Contested marketplaces: Retail spaces at the global urban margins. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2019, 44, 877–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ECORYS. Desenvolvimento Urbano Sustentável em Portugal: Uma Abordagem Integrada; Comissão Europeia: Lisboa, Portugal, 2011; Available online: https://op.europa.eu/pt/publication-detail/-/publication/3ef52e9e-19ce-4fa4-947f-05ee14133000/language-pt (accessed on 23 August 2020).

- Guillemot, L. Centres Historiques, Commerce et Mobilités. De Nouvelles Mobilités Source de Résilience. In Aménagement et Résilience du Commerce Urbain en France; Soumagne, J., Ed.; L’Harmattan: Paris, France, 2014; pp. 41–82. [Google Scholar]

- Wrigley, N. Evolving High Streets: In What Ways Can Social Science Research Add Value? In Evolving High Streets: Resilience and Reinvention; Wrigley, N., Brookes, E., Eds.; University of Southampton: Southampton, UK, 2014; pp. 6–10. [Google Scholar]

- Gasnier, A.; Guillemot, L. Crisis and resilience of traditional city centres in France. In Retail Planning for the Resilient City. Consumption and Urban Regeneration; Barata-Salgueiro, T., Cachinho, H., Eds.; Centro de Estudos Geográficos: Lisbon, Portugal, 2011; pp. 63–79. [Google Scholar]

- Dugot, P.; Navereau, B. Toward a Reconciliation of Retail and City? The French Case. Revista Cidades. 2014. Available online: https://revista.fct.unesp.br/index.php/revistacidades/article/viewFile/4243/3221 (accessed on 25 May 2020).

- Peel, D.; Parker, C. Planning and governance issues in the restructuring of the high street. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2017, 10, 404–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Healey, P. Collaborative planning in a stakeholder society. Town Plan. Rev. 1998, 69, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]