Technical Principles in Elective Surgical Treatment of Left Colon Diverticular Disease: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

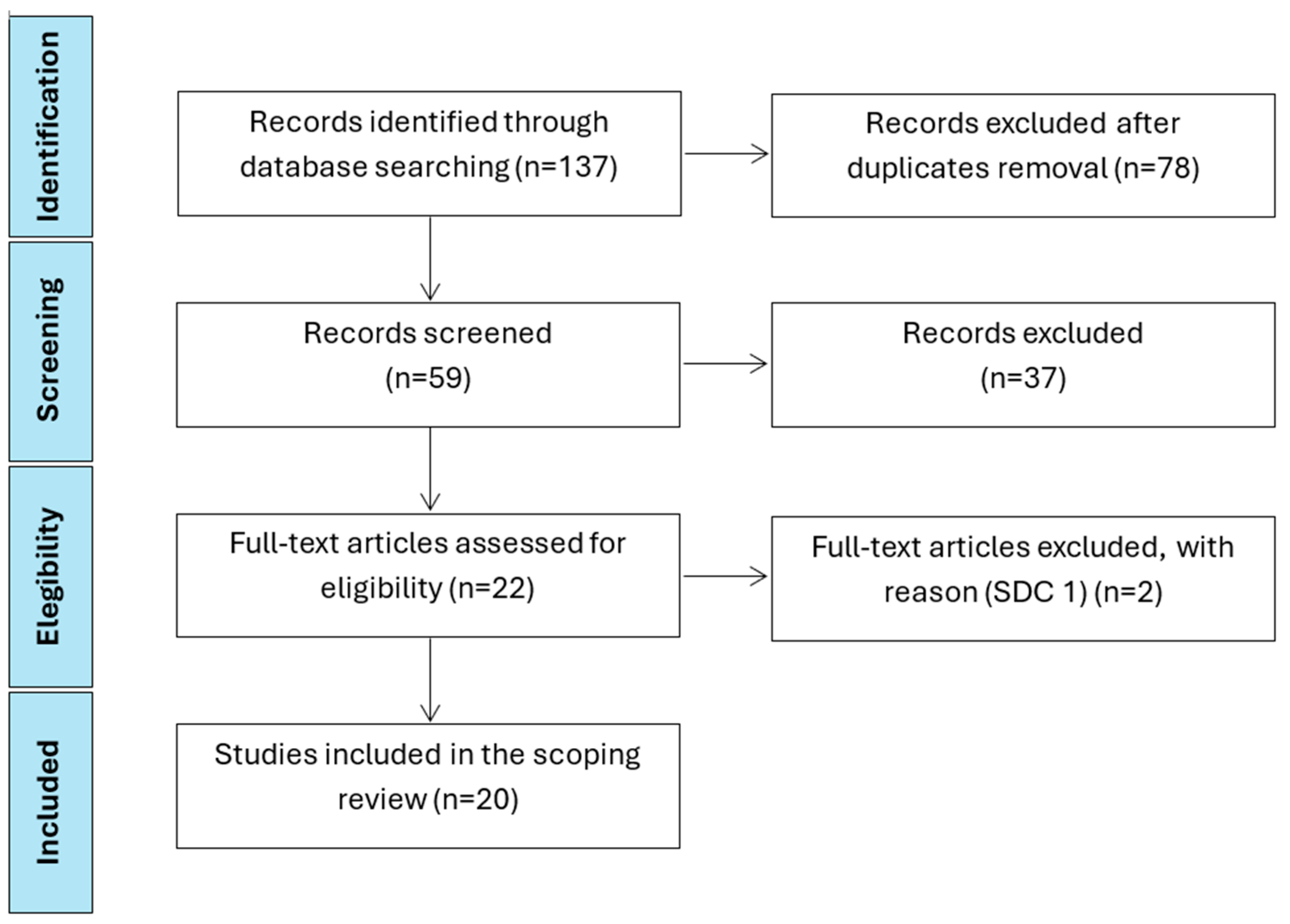

2. Methods

3. Results

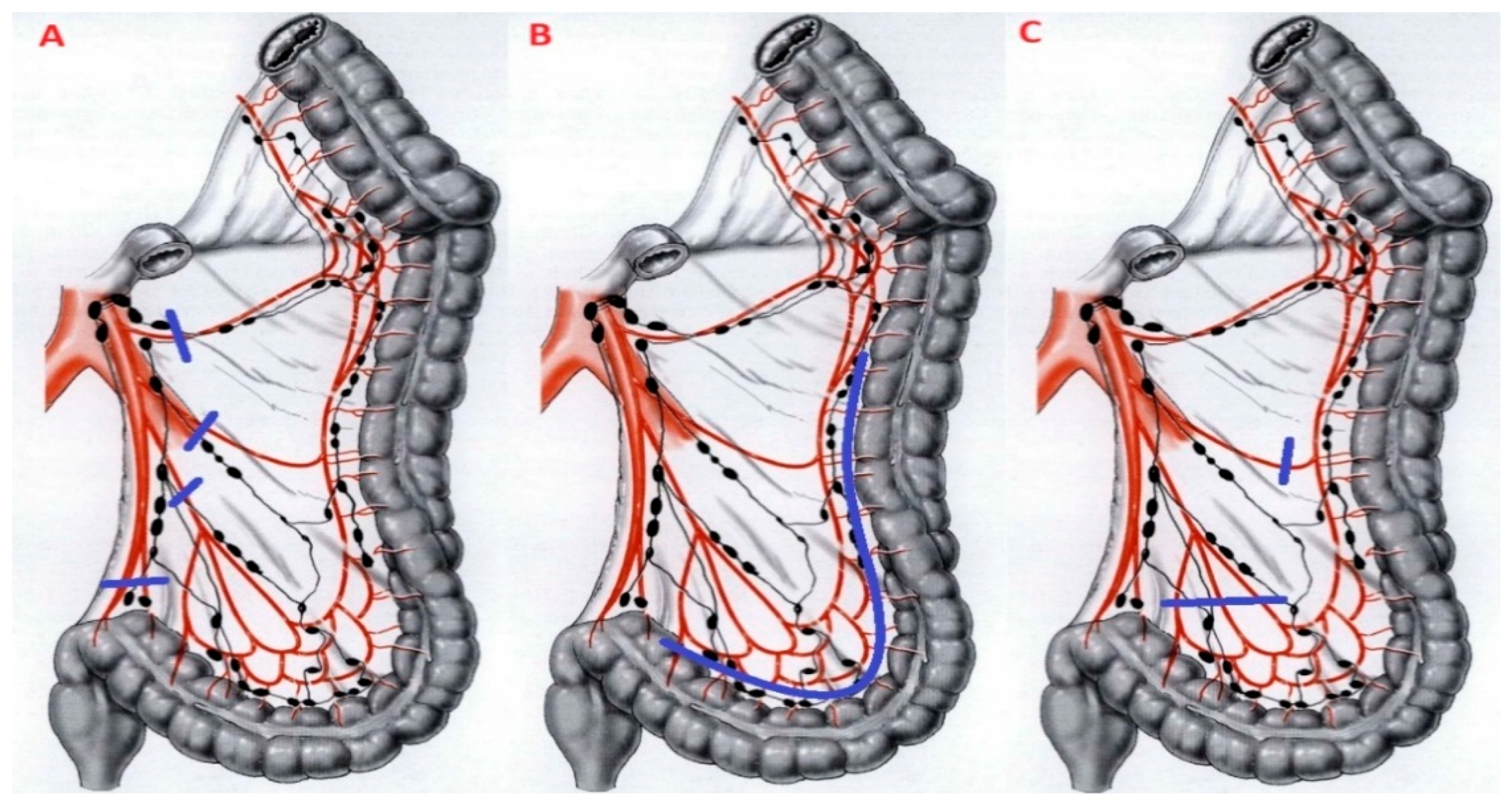

3.1. Inferior Mesenteric Artery (IMA) Ligation

3.2. Splenic Flexure Mobilization (SFM)

3.3. Extent of Resection and Anastomotic Level

3.4. Surgical Approach (Laparoscopic (LPS), Robotic (RBT), Open)

4. Discussion

4.1. Inferior Mesenteric Artery (IMA) Ligation

4.2. Splenic Flexure Mobilization (SFM)

4.3. The Extent of Colonic Resection

4.4. Surgical Approach (Laparoscopic (LPS), Robotic (RBT), Open)

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Heise, C.P. Epidemiology and pathogenesis of diverticular disease. J. Gastrointest. Surg. Off. J. Soc. Surg. Aliment. Tract 2008, 12, 1309–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciardi, R.; Baxter, N.N.; Read, T.E.; Marcello, P.W.; Hall, J.; Roberts, P.L. Is the decline in the surgical treatment for diverticulitis associated with an increase in complicated diverticulitis? Dis. Colon Rectum 2009, 52, 1558–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weizman, A.V.; Nguyen, G.C. Diverticular disease: Epidemiology and management. Can. J. Gastroenterol. 2011, 25, 385–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bollom, A.; Austrie, J.; Hirsch, W.; Nee, J.; Friedlander, D.; Ellingson, K.; Cheng, V.; Lembo, A. Emergency Department Burden of Diverticulitis in the USA, 2006–2013. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2017, 62, 2694–2703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzioni, D.A.; Mack, T.M.; Beart, R.W., Jr.; Kaiser, A.M. Diverticulitis in the United States: 1998–2005: Changing patterns of disease and treatment. Ann. Surg. 2009, 249, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghadamyeghaneh, Z.; Carmichael, J.C.; Smith, B.R.; Mills, S.; Pigazzi, A.; Nguyen, N.T.; Stamos, M.J. A comparison of outcomes of emergent, urgent, and elective surgical treatment of diverticulitis. Am. J. Surg. 2015, 210, 838–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, F.; Guerci, C.; Bondurri, A.; Spinelli, A.; De Nardi, P.; indexed collaborators. Emergency surgical treatment of colonic acute diverticulitis: A multicenter observational study on behalf of the Italian society of colorectal surgery (SICCR) Lombardy committee. Updates Surg. 2023, 75, 863–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nocera, F.; Haak, F.; Posabella, A.; Angehrn, F.V.; Peterli, R.; Müller-Stich, B.P.; Steinemann, D.C. Surgical outcomes in elective sigmoid resection for diverticulitis stratified according to indication: A propensity-score matched cohort study with 903 patients. Langenbeck’s Arch. Surg. 2023, 408, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, J.; Hardiman, K.; Lee, S.; Lightner, A.; Stocchi, L.; Paquette, I.M.; Steele, S.R.; Feingold, D.L.; Prepared on behalf of the Clinical Practice Guidelines Committee of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons. The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Treatment of Left-Sided Colonic Diverticulitis. Dis. Colon Rectum 2020, 63, 728–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrara, F.; Bollo, J.; Vanni, L.V.; Targarona, E.M. Diagnosis and management of right colonic diverticular disease: A review. Diagnóstico y tratamiento de la enfermedad diverticular del colon derecho: Revisión de conjunto. Cir. Esp. 2016, 94, 553–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Wall, B.J.M.; Stam, M.A.W.; Draaisma, W.A.; Stellato, R.; Bemelman, W.A.; Boermeester, M.A.; Broeders, I.A.M.J.; Belgers, E.J.; Toorenvliet, B.R.; Prins, H.A.; et al. Surgery versus conservative management for recurrent and ongoing left-sided diverticulitis (DIRECT trial): An open-label, multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 2, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leifeld, L.; Germer, C.T.; Böhm, S.; Dumoulin, F.L.; Frieling, T.; Kreis, M.; Meining, A.; Labenz, J.; Lock, J.F.; Ritz, J.P.; et al. S3-Leitlinie Divertikelkrankheit/Divertikulitis—Gemeinsame Leitlinie der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Gastroenterologie, Verdauungs- und Stoffwechselkrankheiten (DGVS) und der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Allgemein- und Viszeralchirurgie (DGAV). Z. Gastroenterol. 2022, 60, 613–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feingold, D.; Steele, S.R.; Lee, S.; Kaiser, A.; Boushey, R.; Buie, W.D.; Rafferty, J.F. Practice parameters for the treatment of sigmoid diverticulitis. Dis. Colon Rectum 2014, 57, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munson, K.D.; Hensien, M.A.; Jacob, L.N.; Robinson, A.M.; Liston, W.A. Diverticulitis. A comprehensive follow-up. Dis. Colon Rectum 1996, 39, 318–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergamaschi, R. Uncomplicated diverticulitis of the sigmoid: Old challenges. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 1997, 32, 1187–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benn, P.L.; Wolff, B.G.; Ilstrup, D.M. Level of anastomosis and recurrent colonic diverticulitis. Am. J. Surg. 1986, 151, 269–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergamaschi, R.; Arnaud, J.P. Anastomosis level and specimen length in surgery for uncomplicated diverticulitis of the sigmoid. Surg. Endosc. 1998, 12, 1149–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaler, K.; Baig, M.K.; Berho, M.; Weiss, E.G.; Nogueras, J.J.; Arnaud, J.P.; Wexner, S.D.; Bergamaschi, R. Determinants of recurrence after sigmoid resection for uncomplicated diverticulitis. Dis. Colon Rectum 2003, 46, 385–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Parker, D.; Soares, C.B. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int. J. Evid.-Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. IS 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tocchi, A.; Mazzoni, G.; Fornasari, V.; Miccini, M.; Daddi, G.; Tagliacozzo, S. Preservation of the inferior mesenteric artery in colorectal resection for complicated diverticular disease. Am. J. Surg. 2001, 182, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehmann, R.K.; Brounts, L.R.; Johnson, E.K.; Rizzo, J.A.; Steele, S.R. Does sacrifice of the inferior mesenteric artery or superior rectal artery affect anastomotic leak following sigmoidectomy for diverticulitis? A retrospective review. Am. J. Surg. 2011, 201, 623–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirocchi, R.; Trastulli, S.; Farinella, E.; Desiderio, J.; Listorti, C.; Parisi, A.; Noya, G.; Boselli, C. Is inferior mesenteric artery ligation during sigmoid colectomy for diverticular disease associated with increased anastomotic leakage? A meta-analysis of randomized and non-randomized clinical trials. Color. Dis. Off. J. Assoc. Coloproctol. Great Br. Irel. 2012, 14, e521–e529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mari, G.; Crippa, J.; Costanzi, A.; Mazzola, M.; Magistro, C.; Ferrari, G.; Maggioni, D. Genito-Urinary Function and Quality of Life After Elective Totally LPS Sigmoidectomy After at Least One Episode of Complicated Diverticular Disease According to Two Different Vascular Approaches: The IMA Low Ligation or the IMA Preservation. Chirurgia 2017, 112, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolivet, M.; Trilling, B.; Sage, P.Y.; Boussat, B.; Girard, E.; Faucheron, J.L. Prospective evaluation of functional outcomes after LPS sigmoidectomy with high tie of the inferior mesenteric artery for diverticular disease in consecutive male patients. Tech. Coloproctol. 2020, 24, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Nardi, P.; Gazzetta, P. Does inferior mesenteric artery ligation affect outcome in elective colonic resection for diverticular disease? ANZ J. Surg. 2018, 88, E778–E781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cirocchi, R.; Mari, G.; Amato, B.; Tebala, G.D.; Popivanov, G.; Avenia, S.; Nascimbeni, R. The Dilemma of the Level of the Inferior Mesenteric Artery Ligation in the Treatment of Diverticular Disease: A Systematic Review of the Literature. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestri, V.; Pontecorvi, E.; Sciuto, A.; Pacella, D.; Peltrini, R.; D’Ambra, M.; Lionetti, R.; Filotico, M.; Lauria, F.; Sarnelli, G.; et al. Preservation of the inferior mesenteric artery VS ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery in left colectomy: Evaluation of functional outcomes-a prospective non-randomized controlled trial. Updates Surg. 2023, 75, 1569–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnesi, S.; Virgilio, F.; Frontali, A.; Zoni, G.; Giugliano, M.; Missaglia, C.; Balla, A.; Sileri, P.; Vignali, A. Inferior mesenteric artery preservation techniques in the treatment of diverticular disease: A systematic review of the literature. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2024, 39, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mari, F.S.; Chiarini, L.; Trampetti, L.; Savina, C.; Cosmi, F.; Cicolani, A.; Gasparrini, M.; Brescia, A. Preservation of inferior mesenteric artery reduces short- and long-term defecatory dysfunction after LPS colorectal resection for diverticular disease: An RCT. Surg. Endosc. 2025, 39, 1761–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlussel, A.T.; Wiseman, J.T.; Kelly, J.F.; Davids, J.S.; Maykel, J.A.; Sturrock, P.R.; Sweeney, W.B.; Alavi, K. Location is everything: The role of splenic flexure mobilization during colon resection for diverticulitis. Int. J. Surg. 2017, 40, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barraud, A.; Sabbagh, C.; Beyer-Berjot, L.; Ouaissi, M.; Zerbib, P.; Bridoux, V.; Manceau, G.; Panis, Y.; Buscail, E.; Venara, A.; et al. Association Severe postoperative morbidity after left colectomy for sigmoid diverticulitis without splenic flexure mobilization. Results of a multicenter cohort study with propensity score analysis. Curr. Probl. Surg. 2024, 61, 101546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parks, T.G. Natural history of diverticular disease of the colon. A review of 521 cases. Br. Med. J. 1969, 4, 639–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, B.G.; Ready, R.L.; MacCarty, R.L.; Dozois, R.R.; Beart, R.W., Jr. Influence of sigmoid resection on progression of diverticular disease of the colon. Dis. Colon Rectum 1984, 27, 645–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoomi, H.; Buchberg, B.; Nguyen, B.; Tung, V.; Stamos, M.J.; Mills, S. Outcomes of LPS versus open colectomy in elective surgery for diverticulitis. World J. Surg. 2011, 35, 2143–2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaertner, W.B.; Kwaan, M.R.; Madoff, R.D.; Willis, D.; Belzer, G.E.; Rothenberger, D.A.; Melton, G.B. The evolving role of laparoscopy in colonic diverticular disease: A systematic review. World J. Surg. 2013, 37, 629–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giuliani, G.; Guerra, F.; Coletta, D.; Giuliani, A.; Salvischiani, L.; Tribuzi, A.; Caravaglios, G.; Genovese, A.; Coratti, A. Robotic versus conventional LPS technique for the treatment of left-sided colonic diverticular disease: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2022, 37, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkins, K.; Mohan, H.; Apte, S.S.; Chen, V.; Rajkomar, A.; Larach, J.T.; Smart, P.; Heriot, A.; Warrier, S. A systematic review and meta-analysis of robotic resections for diverticular disease. Color. Dis. Off. J. Assoc. Coloproctol. Great Br. Irel. 2022, 24, 1105–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cirocchi, R.; Sapienza, P.; Anania, G.; Binda, G.A.; Avenia, S.; di Saverio, S.; Tebala, G.D.; Zago, M.; Donini, A.; Mingoli, A.; et al. State-of-the-art surgery for sigmoid diverticulitis. Langenbeck’s Arch. Surg. 2022, 407, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messinetti, S.; Giacomelli, L.; Manno, A.; Finizio, R.; Fabrizio, G.; Granai, A.V.; Busicchio, P.; Lauria, V. Preservation and peeling of the inferior mesenteric artery in the anterior resection for complicated diverticular disease. Ann. Ital. Chir. 1998, 69, 479–483. [Google Scholar]

- Gall, F.P. Die tubuläre Rectum-und Colonresektion. Eine neue Operationsmethode zur Entfernung von grossen Adenomen und Low Risk-Carcinomen [Tubular rectum and colon resection. A new operative method for the removal of large adenomas and low-risk carcinomas]. Chir. Z. Geb. Oper. Medizen 1982, 53, 489–494. [Google Scholar]

- Schumpelich, V. Tubular resection of the sigmoid colon. In Atlas of General Surgery; Enke: Stuttgart, Germany, 2009; pp. 334–339. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, A.; Macdonald, A.; Oliphant, R.; Russell, D.; Fogg, Q.A. Neurovasculature of high and low tie ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery. Surg. Radiol. Anat. 2018, 40, 1343–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Posabella, A.; Varathan, N.; Steinemann, D.C.; Göksu Ayçiçek, S.; Tampakis, A.; von Flüe, M.; Droeser, R.A.; Füglistaler, I.; Rotigliano, N. Long-term urogenital assessment after elective LPS sigmoid resection for diverticulitis: A comparison between central and peripheral vascular resection. Color. Dis. Off. J. Assoc. Coloproctol. Great Br. Irel. 2021, 23, 911–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, J.K.; Azhar, N.; Binda, G.A.; Barbara, G.; Biondo, S.; Boermeester, M.A.; Chabok, A.; Consten, E.C.J.; van Dijk, S.T.; Johanssen, A.; et al. European Society of Coloproctology: Guidelines for the management of diverticular disease of the colon. Color. Dis. Off. J. Assoc. Coloproctol. Great Br. Irel. 2020, 22 (Suppl. S2), 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brennan, D.J.; Moynagh, M.; Brannigan, A.E.; Gleeson, F.; Rowland, M.; O’Connell, P.R. Routine mobilization of the splenic flexure is not necessary during anterior resection for rectal cancer. Dis. Colon Rectum 2007, 50, 302–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.S.; Kang, S.B.; Kim, D.W.; Lee, K.H.; Kim, Y.H. LPS versus open resection without splenic flexure mobilization for the treatment of rectum and sigmoid cancer: A study from a single institution that selectively used splenic flexure mobilization. Surg. Laparosc. Endosc. Percutan. Tech. 2009, 19, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mari, G.; Sassun, R.; De Carli, S.M.; Miranda, A.; Gerosa, M.; Di Fratta, E.; Santonocito, M.; Roufael, F.; Gianino, M.; Vignati, B.; et al. Standardizing Elective Surgery in Diverticular Disease. Ann. Ital. Chir. 2025, 96, 1420–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author (Year) | Study Type | N. Patients | Technical Principles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agnesi S et al. (2024) [31] | Systematic review | 989 | IMA preservation |

| Barraud et al. (2024) [34] | Multicentric retrospective cohort | 1014 | SFM |

| Benn et al. (1986) [16] | Retrospective cohort | 501 | Extent of resection and anastomotic level |

| Cirocchi et al. (2012) [25] | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 400 | IMA preservation vs. ligation |

| Cirocchi et al. (2022) [41] | Systematic review | 2812 | IMA preservation vs. ligation |

| De Nardi et al. (2018) [28] | Retrospective cohort | 219 | IMA preservation vs. ligation |

| Gaertner et al. (2013) [38] | Systematic review | 931 | Surgical approach: LPS vs. open |

| Giuliani G et al. (2022) [39] | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 4177 | Surgical approach: LPS vs. RBT |

| Jolivet et al. (2020) [27] | Prospective non-randomized controlled trial | 52 | IMA preservation |

| Larkins et al. (2022) [40] | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 3711 | Surgical approach: LPS vs. RBT |

| Lehmann et al. (2011) [24] | Retrospective cohort | 130 | IMA preservation vs. ligation |

| Mari et al. (2017) [26] | Prospective multicenter parallel study | 66 | IMA preservation vs. ligation |

| Mari et al. (2025) [32] | RCT | 219 | IMA preservation vs. ligation |

| Masoomi et al. (2011) [37] | Retrospective cohort | 124,734 | Surgical approach: LPS vs. open |

| Parks (1969) [35] | Retrospective cohort | 521 | Extent of resection and natural history |

| Schlussel et al. (2017) [33] | Retrospective cohort | 208 | SFM |

| Silvestri et al. (2023) [30] | Prospective non-randomized controlled trial | 122 | IMA ligation vs. preservation |

| Thaler et al. (2003) [18] | Retrospective cohort | 236 | Extent of resection |

| Tocchi A et al. (2001) [23] | RCT | 163 | IMA preservation vs. ligation |

| Wolff et al. (1984) [36] | Retrospective cohort | 61 | Extent of resection |

| Technical Principles | Main Results |

|---|---|

| IMA preservation | Higher conversion rate and longer operative times, with comparable bleeding rate. Lower AL rate. Comparable functional outcomes and overall QoL. |

| SFM | Longer operative times and comparable bleeding rate. Higher rate of minor postoperative complications, comparable rate of major postoperative complications. To perform according to operating surgeon’s judgment. |

| The extent of colonic resection | Resection of the segment of the left colon involved diverticular inflammation, extending distally to the level of the rectosigmoid junction. |

| Surgical approach | LPS vs. Open: longer operative time, reduced intraoperative blood loss and lower physiological stress. Lower incidence of postoperative complications, lower postoperative mortality, shorter hospital stays and reduced overall healthcare costs RBT vs. LPS: longer operative time, lower conversion rate. Shorter LOS and lower overall costs |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Amodio, L.E.; Rizzo, G.; Marzi, F.; Marandola, C.; Ferrara, F.; Tondolo, V. Technical Principles in Elective Surgical Treatment of Left Colon Diverticular Disease: A Scoping Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8645. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248645

Amodio LE, Rizzo G, Marzi F, Marandola C, Ferrara F, Tondolo V. Technical Principles in Elective Surgical Treatment of Left Colon Diverticular Disease: A Scoping Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8645. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248645

Chicago/Turabian StyleAmodio, Luca Emanuele, Gianluca Rizzo, Federica Marzi, Camilla Marandola, Francesco Ferrara, and Vincenzo Tondolo. 2025. "Technical Principles in Elective Surgical Treatment of Left Colon Diverticular Disease: A Scoping Review" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8645. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248645

APA StyleAmodio, L. E., Rizzo, G., Marzi, F., Marandola, C., Ferrara, F., & Tondolo, V. (2025). Technical Principles in Elective Surgical Treatment of Left Colon Diverticular Disease: A Scoping Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8645. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248645