A Sampling Method Considering Body Size for Detecting the Associated Microbes in Plankton Populations: A Case Study, Using the Bloom-Forming Cyanobacteria, Microcystis

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Microcystis Colony Size Measurements

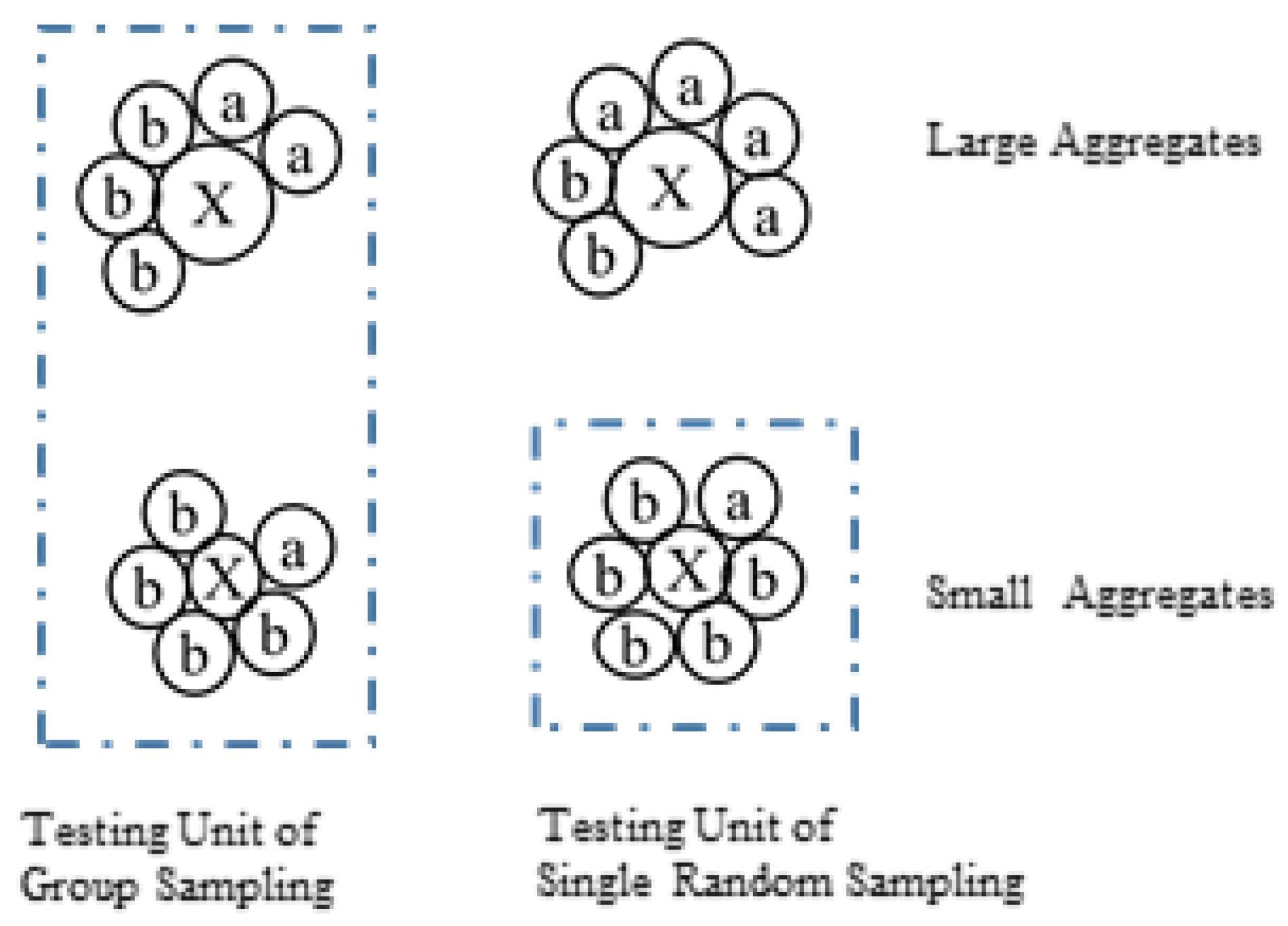

2.2. Detection of Associated Microbes in Microcystis Colonies

2.3. Simulated Population Construction

- (1)

- A sequence was created with a length of 500,000, averaging Mean(log(SM.a.)), and the standard deviation was SD(log(SM.a.)); was the simulated SX. SY was calculated in the same step based on Mean(log(SM.w.)) and SD(log(SM.w.)). RX and RY were calculated based on Mean(log(RM.a.)) and Mean(log(RM.w.)).

- (2)

- , which presents the actual RT value of the community in this sub-dataset.

- (3)

- .

- (4)

- . A is a lognormally distributed sequence based on P.

- (5)

- . The RT of the community with A obtained from step (4) was obtained as an Rpositive sequence and SX as an S sequence.

- (6)

- .

- (7)

- was simulated according to steps (2) to (6), with the constants B in step (2) being negative.

- (8)

- Datasets Y and Z were simulated in a similar manner.

2.4. The Calculation of Microbe/Microcystis via Different Sampling Plans

2.5. Statistical Efficiency of Different Sampling Plans

3. Results

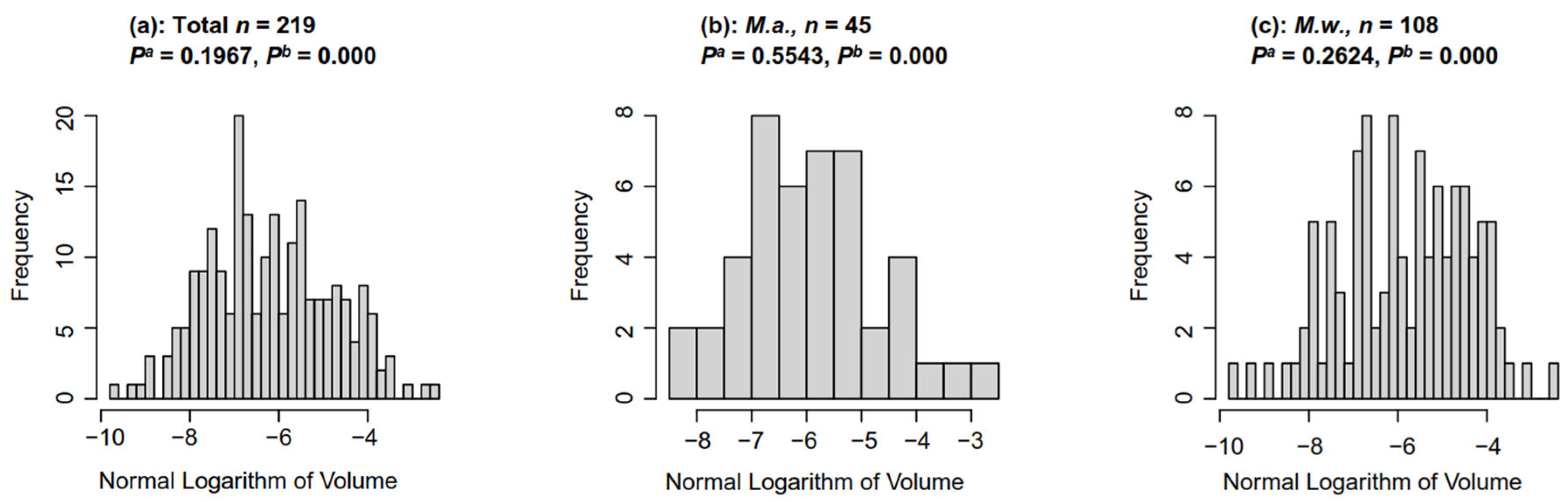

3.1. Distribution of Microcystis Colony Size

3.2. Characteristics of Simulated Datasets

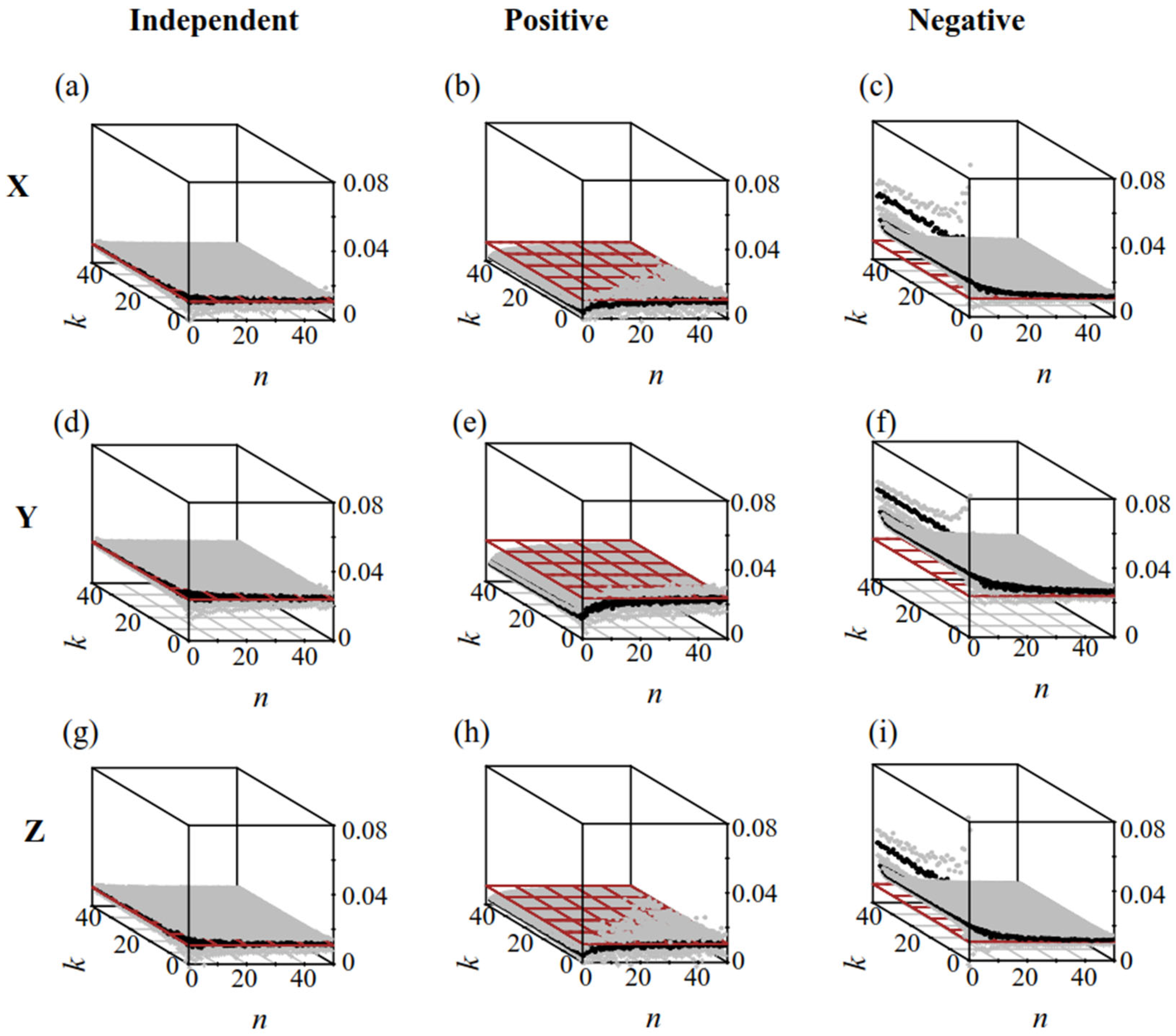

3.3. Accuracy of Different Sampling Plans

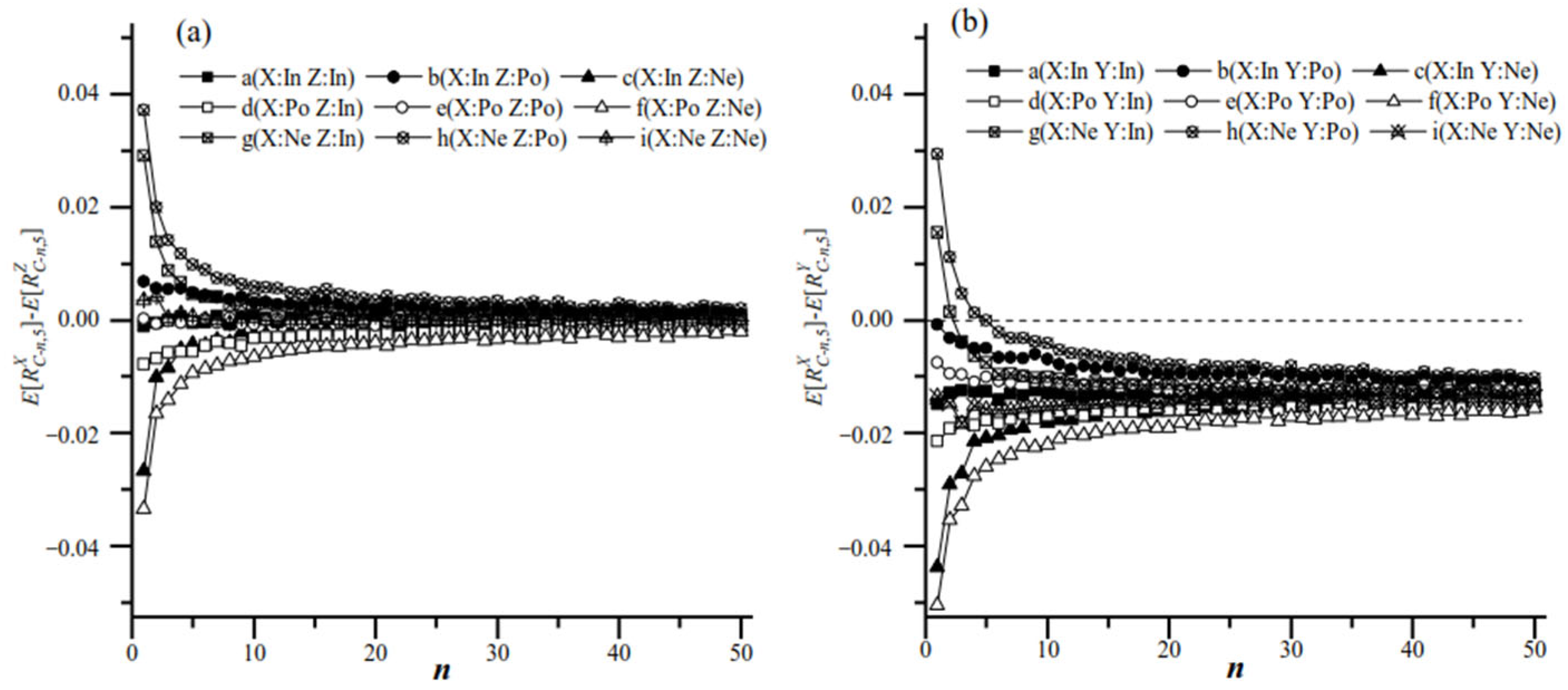

3.3.1. Systematic and Stochastic Errors of Different Sampling Plans

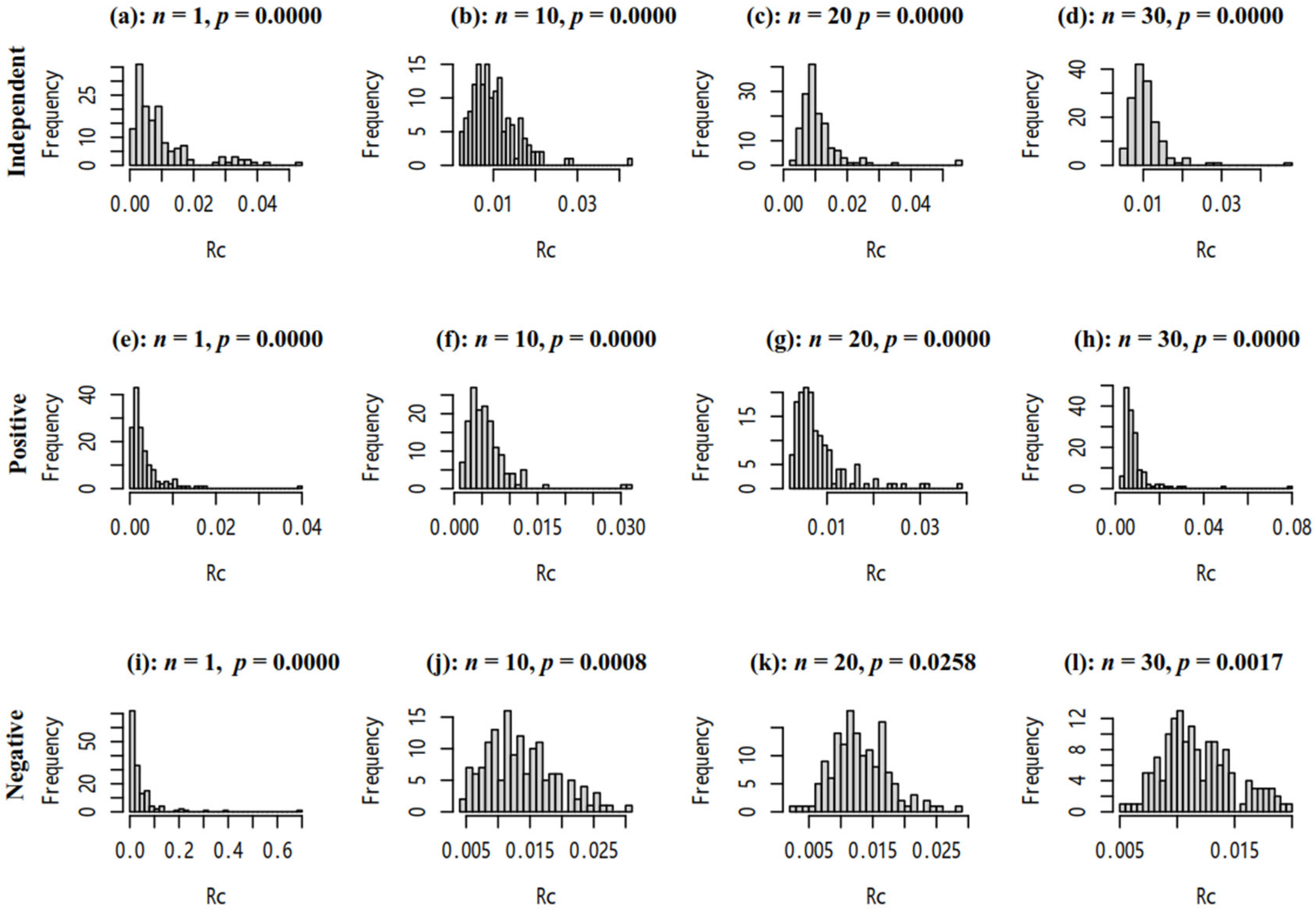

3.3.2. The Distribution of RC

3.4. Permutation Test Between Two Populations

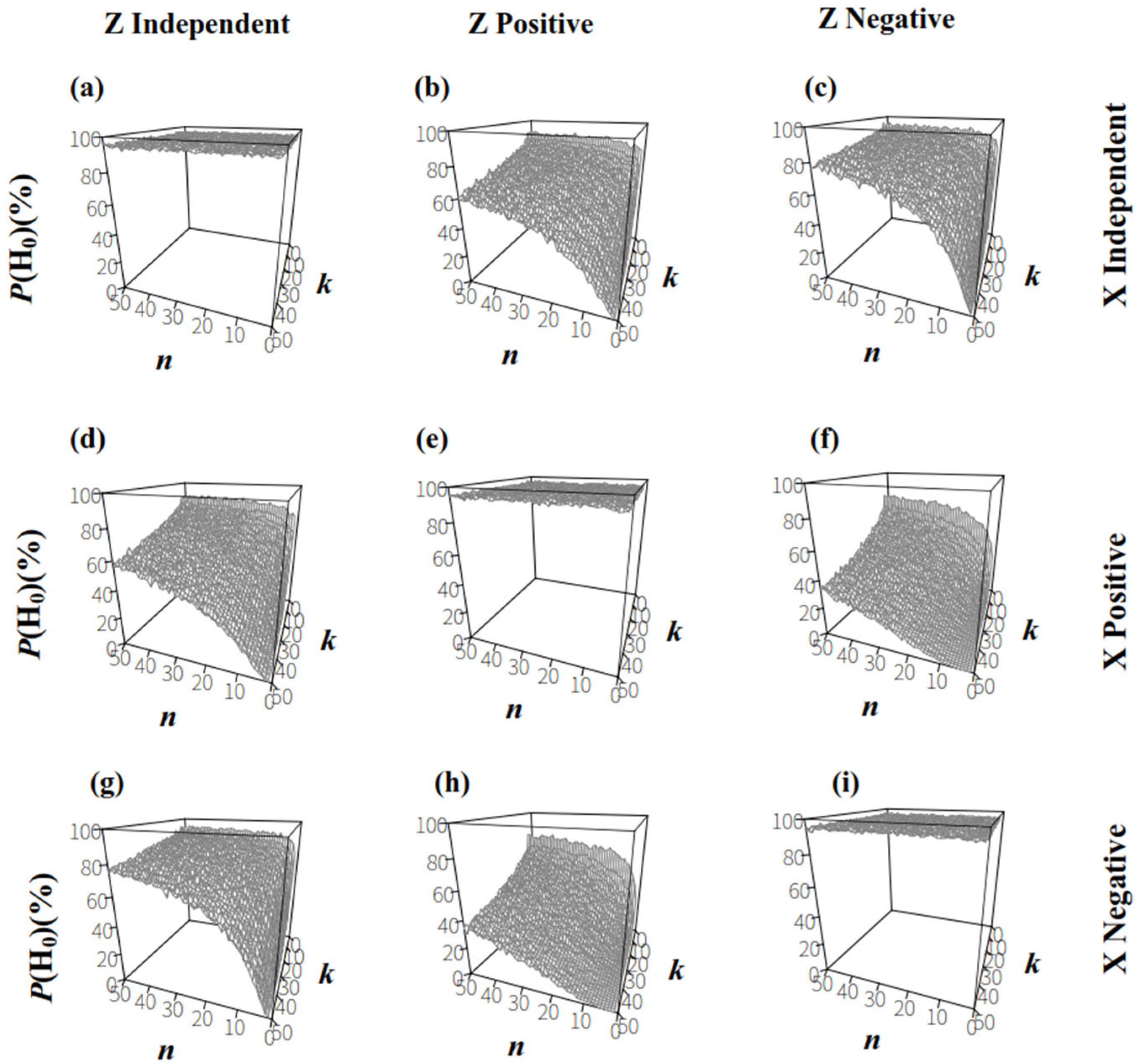

3.4.1. Two Populations Had the Same Microbe/Microcystis Ratios

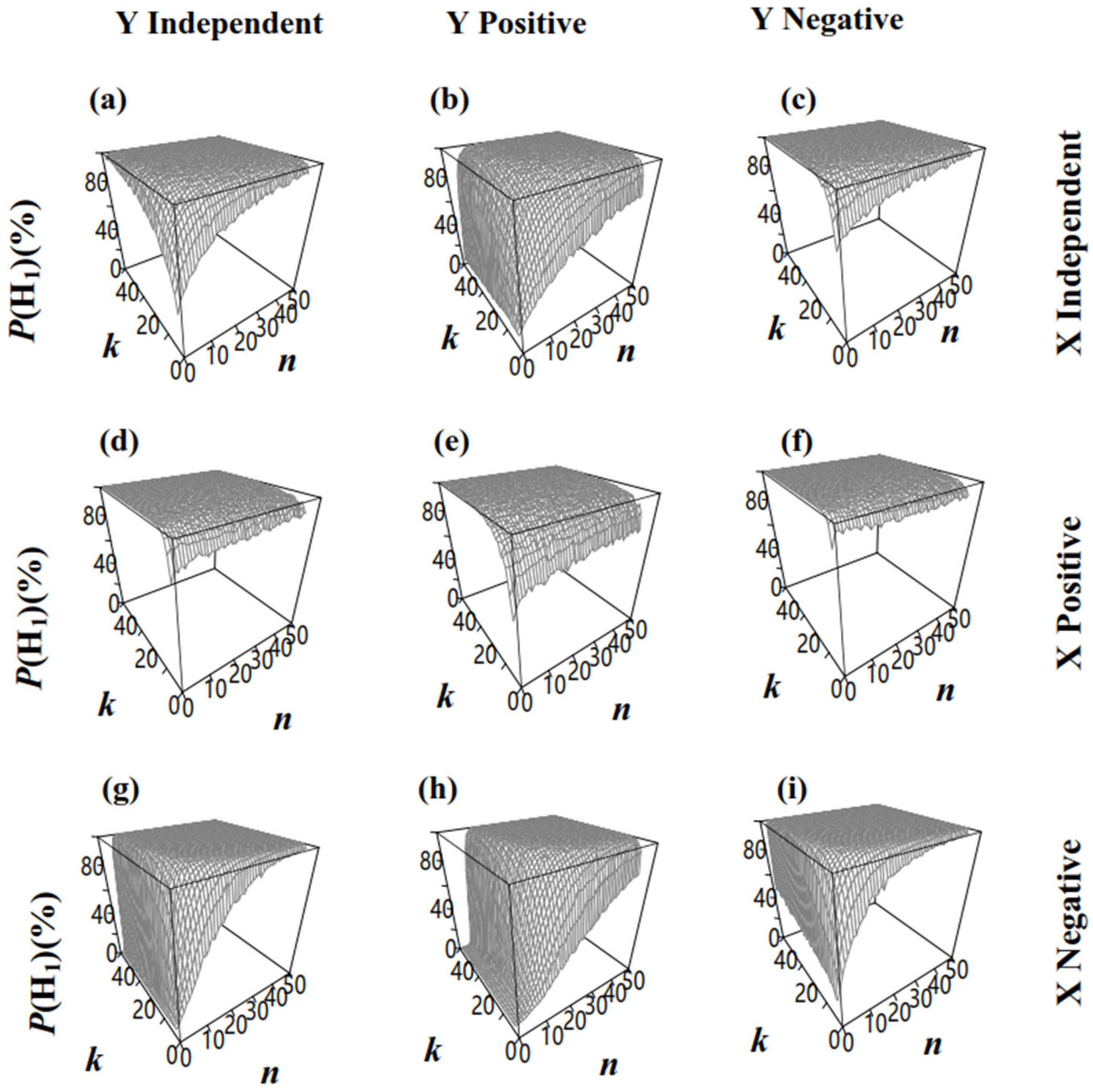

3.4.2. Two Populations Had Different Microbe/Microcystis Ratios

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of Sampling Plans on the Detection of Associated Microbes in Populations

4.2. Cost and Efficiency of Different Sampling Plans

4.3. Effects of Sampling Plans on the Limit of Detection

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ger, K.A.; Urrutia-Cordero, P.; Frost, P.C.; Hansson, L.A.; Sarnelle, O.; Wilson, A.E.; Lurling, M. The interaction between cyanobacteria and zooplankton in a more eutrophic world. Harmful Algae 2016, 54, 128–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirri, E.; Pohnert, G. Algae-bacteria interactions that balance the planktonic microbiome. New Phytol. 2019, 223, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siano, R.; Alves-de-Souza, C.; Foulon, E.; Bendif, E.M.; Simon, N.; Guillou, L.; Not, F. Distribution and host diversity of Amoebophryidae parasites across oligotrophic waters of the Mediterranean Sea. Biogeosciences 2011, 8, 267–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chorazyczewski, A.M.; Huang, I.-S.; Abdulla, H.; Mayali, X.; Zimba, P.V. The Influence of Bacteria on the Growth, Lipid Production, and Extracellular Metabolite Accumulation by Phaeodactylum tricornutum (Bacillariophyceae). J. Phycol. 2021, 57, 931–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimbrel, J.A.; Samo, T.J.; Ward, C.; Nilson, D.; Thelen, M.P.; Siccardi, A.; Zimba, P.; Lane, T.W.; Mayali, X. Host selection and stochastic effects influence bacterial community assembly on the microalgal phycosphere. Algal Res. 2019, 40, 101489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallegraeff, G.M.; Blackburn, S.I.; Doblin, M.A.; Bolch, C.J.S. Global toxicology, ecophysiology and population relationships of the chainforming PST dinoflagellate Gymnodinium catenatum. Harmful Algae 2012, 14, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreidah, C.M.; Ratnayake, K.; Senarath, K.; Karunarathne, A. Microcystins: Biogenesis, Toxicity, Analysis, and Control. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2020, 33, 2225–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Shan, K.; Lin, L.; Shen, W.; Huang, L.; Gan, N.; Song, L. Multi-Year Assessment of Toxic Genotypes and Microcystin Concentration in Northern Lake Taihu, China. Toxins 2016, 8, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Chen, H.; Yang, J.R.; Liu, M.; Huang, B.; Yang, J. Distinct patterns and processes of abundant and rare eukaryotic plankton communities following a reservoir cyanobacterial bloom. ISME J. 2018, 12, 2263–2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eiler, A.; Heinrich, F.; Bertilsson, S. Coherent dynamics and association networks among lake bacterioplankton taxa. ISME J. 2012, 6, 330–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivkin, R.B.; Phinney, D.A.; Yentsch, C.M. Effects of Flow Cytometric Analysis and Cell Sorting on Photosynthetic Carbon Uptake by Phytoplankton in Cultures and from Natural Populations. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1986, 52, 935–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, F.H.; Uddstrom, M.J.; Pinkerton, M.H.; Richardson, K.M. Characterising the 2002 toxic Karenia concordia (Dinophyceae) outbreak and its development using satellite imagery on the north-eastern coast of New Zealand. Harmful Algae 2008, 7, 532–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Chen, T. A novel hematoxylin and eosin stain assay for detection of the parasitic dinoflagellate Amoebophrya. Harmful Algae 2017, 62, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitatsuji, S.; Yamaguchi, H.; Asahi, T.; Ichimi, K.; Onitsuka, G.; Tada, K. Does Noctiluca scintillans end the diatom bloom in coastal water? J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2019, 510, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wu, Z.; Yu, B.; Peng, X.; Yu, G.; Wei, Z.; Wang, G.; Li, R. Non-microcystin producing Microcystis wesenbergii (Komarek) Komarek (Cyanobacteria) representing a main waterbloom-forming species in Chinese waters. Environ. Pollut. 2008, 156, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shia, L.; Cai, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, P.; Yu, Y.; Kong, F. Community Structure of Bacteria Associated with Microcystis Colonies from Cyanobacterial Blooms. J. Freshw. Ecol. 2010, 25, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Cai, Y.; Kong, F.; Yu, Y. Specific association between bacteria and buoyant Microcystis colonies compared with other bulk bacterial communities in the eutrophic Lake Taihu, China. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2012, 4, 669–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Via-Ordorika, L.; Fastner, J.; Kurmayer, R.; Hisbergues, M.; Dittmann, E.; Komarek, J.; Erhard, M.; Chorus, I. Distribution of microcystin-producing and non-microcystin-producing Microcystis sp. in European freshwater bodies: Detection of microcystins and microcystin genes in individual colonies. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2004, 27, 592–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welker, M.; Brunke, M.; Preussel, K.; Lippert, I.; von Dohren, H. Diversity and distribution of Microcystis (Cyanobacteria) oligopeptide chemotypes from natural communities studied by single-colony mass spectrometry. Microbiology 2004, 150, 1785–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Chen, R.; Sun, H.; Xue, Y.; Diao, Z.; Song, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, C.; Ma, B.; et al. Culture-free identification of fast-growing cyanobacteria cells by Raman-activated gravity-driven encapsulation and sequencing. Synth. Syst. Biotechnol. 2023, 8, 708–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Sun, M.; Xie, M.; Liu, M.; Luo, L.; Li, P.; Kong, F. Differences in microcystin production and genotype composition among Microcystis colonies of different sizes in Lake Taihu. Water Res. 2013, 47, 5659–5669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, W.; Dai, X.; Li, M. Relationship between extracellular polysaccharides (EPS) content and colony size of Microcystis is colonial morphology dependent. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2014, 55, 346–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Jia, S.; Li, J.; Li, P. Effects of the cultivable bacteria attached to Microcystis colonies on the colony size and growth of Microcystis. J. Freshw. Ecol. 2019, 34, 663–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klawonn, I.; Bonaglia, S.; Bruchert, V.; Ploug, H. Aerobic and anaerobic nitrogen transformation processes in N2-fixing cyanobacterial aggregates. ISME J. 2015, 9, 1456–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, J.L.; Althammer, J.; Skaar, K.S.; Simonelli, P.; Larsen, A.; Stoecker, D.; Sazhin, A.; Ijaz, U.Z.; Quince, C.; Nejstgaard, J.C.; et al. Metabarcoding and metabolome analyses of copepod grazing reveal feeding preference and linkage to metabolite classes in dynamic microbial plankton communities. Mol. Ecol. 2016, 25, 5585–5602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komárek, J.; Komárková, J. Review of the European Microcystis-morphospecies (Cyanoprokaryotes) from nature. Czech Phycol. 2002, 2, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, W.; Ruan, W.; Bi, X.; Zhang, D. The role of attached bacteria in the formation of Microcystis colony in Chentaizi River. Water Sci. Technol. 2022, 86, 968–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Cai, Y.; Gao, S.; Fang, D.; Lu, Y.; Li, P.; Wu, Q.L. Gene expression in the microbial consortia of colonial Microcystis aeruginosa-a potential buoyant particulate biofilm. Environ. Microbiol. 2022, 24, 4931–4945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Lin, L.Z.; Zeng, Y.; Teng, W.K.; Chen, M.Y.; Brand, J.J.; Zheng, L.L.; Gan, N.Q.; Gong, Y.H.; Li, X.Y.; et al. The facilitating role of phycospheric heterotrophic bacteria in cyanobacterial phosphonate availability and Microcystis bloom maintenance. Microbiome 2023, 11, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.J.; Tan, J.Y.; Powers, M.A.; Lin, X.N.; Davis, T.W.; Dick, G.J. Individual Microcystis colonies harbour distinct bacterial communities that differ by Microcystis oligotype and with time. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 23, 3020–3036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Carrascal, O.M.; Tromas, N.; Terrat, Y.; Moreno, E.; Giani, A.; Marques, L.C.B.; Fortin, N.; Shapiro, B.J. Single-colony sequencing reveals microbe-by-microbiome phylosymbiosis between the cyanobacterium Microcystis and its associated bacteria. Microbiome 2021, 9, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maury, Y.; Duby, C.; Bossennec, J.-M.; Boudazin, G. Group analysis using ELISA: Determination of the level of transmission of SOybean Mosaic Virus in soybean seed. Agronomie 1985, 5, 405–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Li, J.; Pan, S. Progress in sampling inspection by Group Attributes. J. Appl. Stat. Manag. 2011, 30, 1132–1140. [Google Scholar]

- Remund, K.M.; Dixon, D.A.; Wright, D.L.; Holden, L.R. Statistical considerations in seed purity testing for transgenic traits. Seed Sci. Res. 2001, 11, 101–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobilinsky, A.; Bertheau, Y. Minimum cost acceptance sampling plans for grain control, with application to GMO detection. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2005, 75, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venrick, E.L. How many cells to count? In Phytoplankton Manual; Sournia, A., Ed.; UNESCO Press: Paris, France, 1978; pp. 167–180. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, A.E.; Kaul, R.B.; Sarnelle, O. Growth rate consequences of coloniality in a harmful phytoplankter. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e8679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klindworth, A.; Pruesse, E.; Schweer, T.; Peplies, J.; Quast, C.; Horn, M.; Glőckner, F.O. Evaluation of general 16S ribosomal RNA gene PCR primers for classical and next-generation sequencing-based diversity studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rognes, T.; Flouri, T.; Nichols, B.; Quince, C.; Mahé, F. VSEARCH: A versatile open source tool for metagenomics. PeerJ 2016, 4, e2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, M. CUTADAPT removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet. J. 2011, 17, 10–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.A.; Holmes, S.P. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, K.R. Non-parametric multivariate analyses of changes in community structure. Aust. J. Ecol. 1993, 18, 117–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.J. A new method for non-parametric multivariate analysis of variance. Austral Ecol. 2001, 26, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dataset | Sub-Dataset | RT | Pearson Correlation Between R and S | Lilliefors Test Ln(S) | Lilliefors Test Ln(R) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | P | D | P | D | P | |||

| X | Sub-dataset 1 | 0.0108 | −0.0008 | 0.5863 | 0.0009 | 0.4058 | 0.0011 | 0.1372 |

| Sub-dataset 2 | 0.0108 | 0.9463 | 0.0000 ** | 0.0010 | 0.2327 | |||

| Sub-dataset 3 | 0.0108 | −0.2671 | 0.0000 ** | 0.0012 | 0.0640 | |||

| Y | Sub-dataset 1 | 0.0238 | −0.0007 | 0.6069 | 0.0013 | 0.0949 | 0.0010 | 0.2704 |

| Sub-dataset 2 | 0.0238 | 0.7655 | 0.0000 ** | 0.0011 | 0.1194 | |||

| Sub-dataset 3 | 0.0238 | −0.3464 | 0.0000 ** | 0.0011 | 0.1288 | |||

| Z | Sub-dataset 1 | 0.0108 | −0.0008 | 0.5863 | 0.0009 | 0.4058 | 0.0011 | 0.1372 |

| Sub-dataset 2 | 0.0108 | 0.8239 | 0.0000 ** | 0.0009 | 0.3640 | |||

| Sub-dataset 3 | 0.0108 | −0.2549 | 0.0000 ** | 0.0013 | 0.0839 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lin, L.; Gan, N.; Huang, L.; Song, L.; Zhao, L. A Sampling Method Considering Body Size for Detecting the Associated Microbes in Plankton Populations: A Case Study, Using the Bloom-Forming Cyanobacteria, Microcystis. Biology 2025, 14, 1493. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14111493

Lin L, Gan N, Huang L, Song L, Zhao L. A Sampling Method Considering Body Size for Detecting the Associated Microbes in Plankton Populations: A Case Study, Using the Bloom-Forming Cyanobacteria, Microcystis. Biology. 2025; 14(11):1493. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14111493

Chicago/Turabian StyleLin, Lizhou, Nanqin Gan, Licheng Huang, Lirong Song, and Liang Zhao. 2025. "A Sampling Method Considering Body Size for Detecting the Associated Microbes in Plankton Populations: A Case Study, Using the Bloom-Forming Cyanobacteria, Microcystis" Biology 14, no. 11: 1493. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14111493

APA StyleLin, L., Gan, N., Huang, L., Song, L., & Zhao, L. (2025). A Sampling Method Considering Body Size for Detecting the Associated Microbes in Plankton Populations: A Case Study, Using the Bloom-Forming Cyanobacteria, Microcystis. Biology, 14(11), 1493. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14111493