Topical Management of Cellulite (Edematous-Fibro-Sclerotic Panniculopathy, EFSP): Current Insights and Emerging Approaches

Abstract

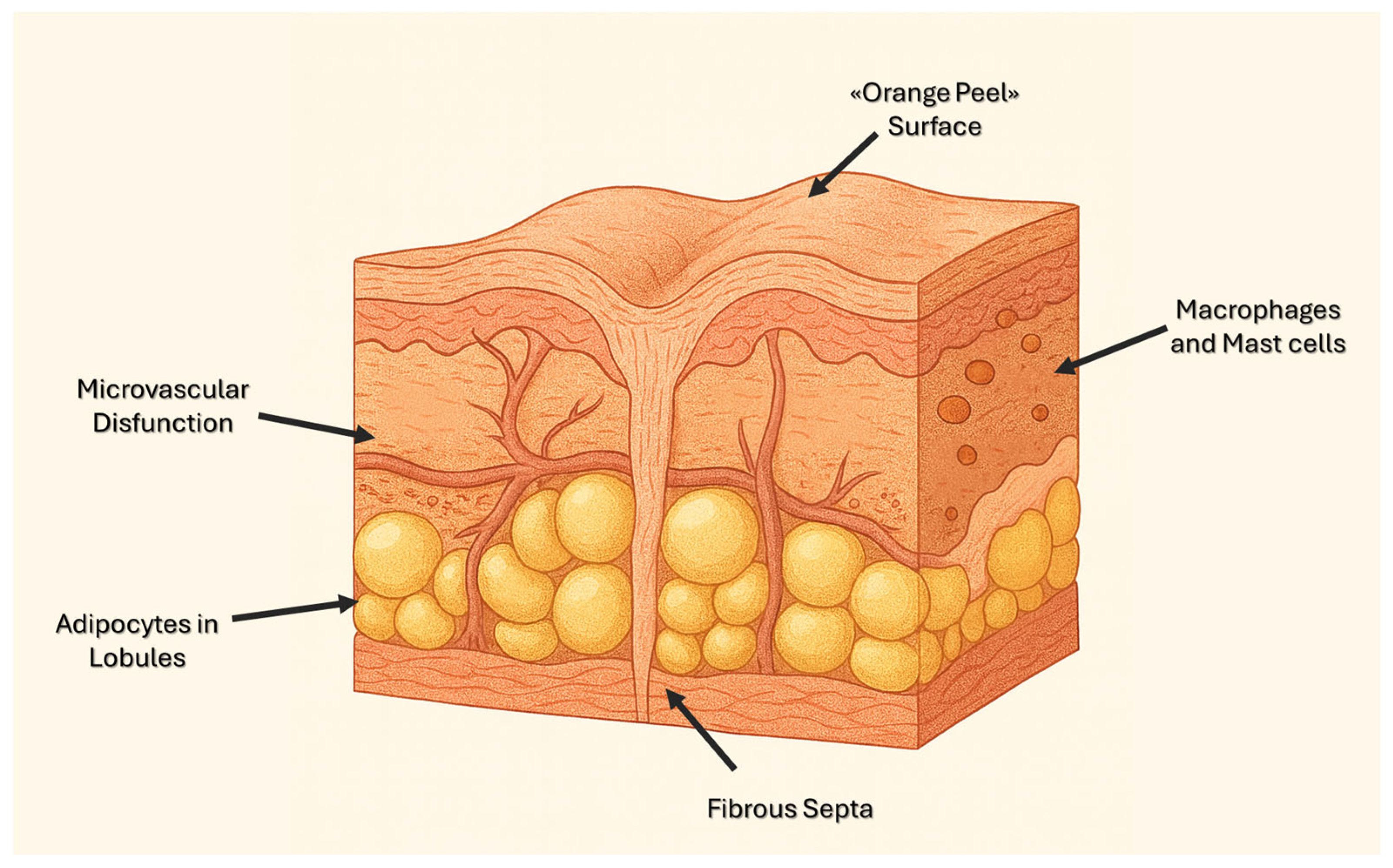

1. Introduction

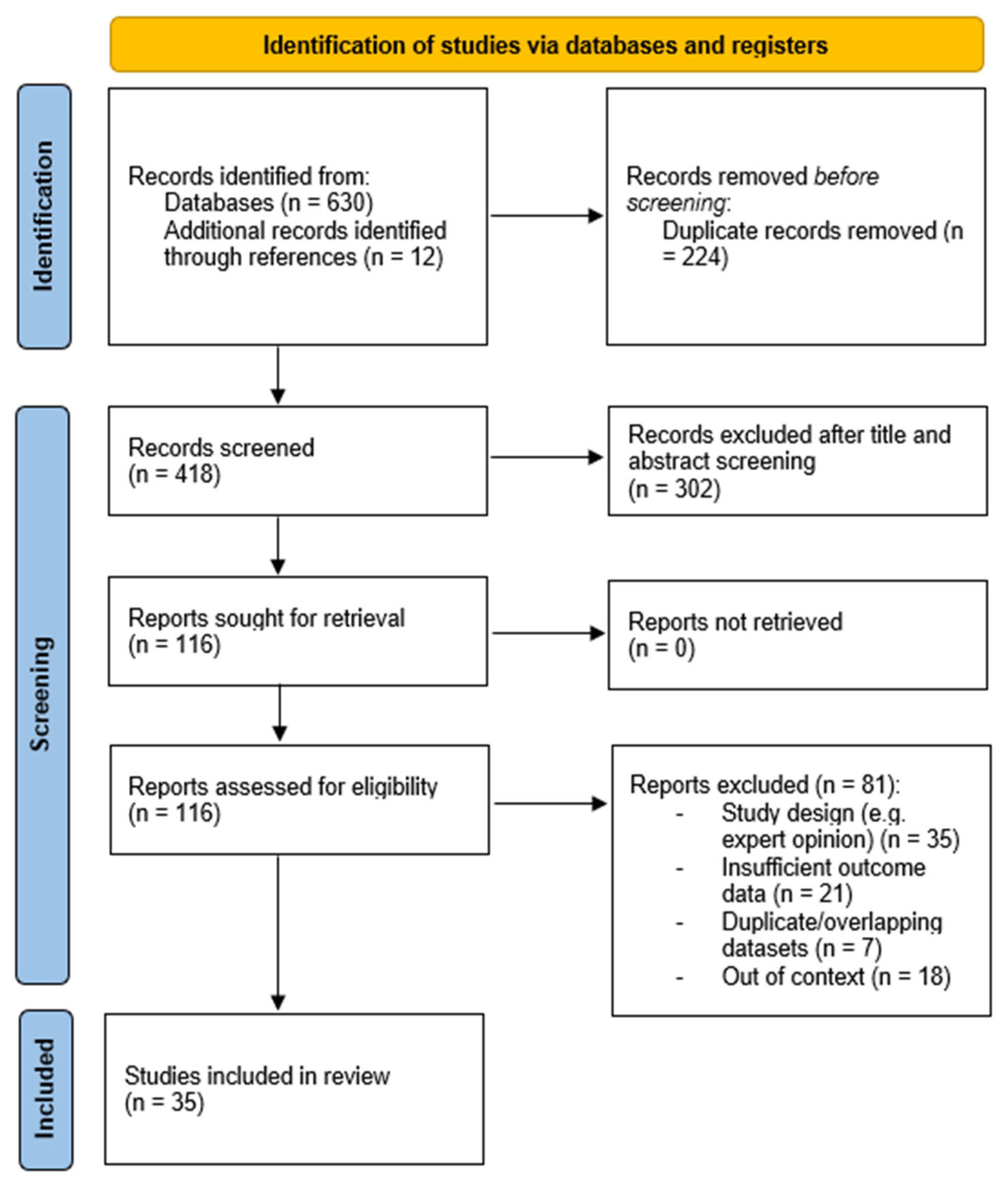

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Microcirculation and Interstitial Edema

3.2. Adipocyte Metabolism and Lipolysis

3.3. Extracellular Matrix Remodeling, Dermal Thickening, and Skin Laxity

3.4. Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, and Glycation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rossi, A.B.; Vergnanini, A.L. Cellulite: A review. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2000, 14, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, S.; Galadari, H.I. Cellulite: An Update on Pathogenesis and Management. Dermatol. Clin. 2024, 42, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, L.S.; Hibler, B.P.; Khalifian, S.; Shridharani, S.M.; Klibanov, O.M.; Moradi, A. Cellulite Pathophysiology and Psychosocial Implications. Dermatol. Surg. 2023, 49, S2–S7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, L.S.; Kaminer, M.S. Insights Into the Pathophysiology of Cellulite: A Review. Dermatol. Surg. 2020, 46, S77–S85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tokarska, K.; Tokarski, S.; Woźniacka, A.; Sysa-Jędrzejowska, A.; Bogaczewicz, J. Cellulite: A cosmetic or systemic issue? Contemporary views on the etiopathogenesis of cellulite. Postepy Dermatol. Alergol. 2018, 35, 442–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabriel, A.; Chan, V.; Caldarella, M.; Wayne, T.; O’Rorke, E. Cellulite: Current Understanding and Treatment. Aesthet. Surg. J. Open Forum. 2023, 5, ojad050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avram, M.M. Cellulite: A review of its physiology and treatment. J. Cosmet. Laser. Ther. 2004, 6, 181–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currî, S.B. Cellulite and fatty tissue microcirculation. Cosmet. Toilet. 1993, 108, 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Emanuele, E.; Bertona, M.; Geroldi, D. A multilocus candidate approach identifies ACE and HIF1A as susceptibility genes for cellulite. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2010, 24, 930–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, G.; Patil, A.; Hooshanginezhad, Z.; Fritz, K.; Salavastru, C.; Kassir, M.; Goldman, M.P.; Gold, M.H.; Adatto, M.; Grabbe, S.; et al. Cellulite: Presentation and management. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2022, 21, 1393–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, G.; Zingaretti, N.; Amuso, D.; Dai Prè, E.; Brandi, J.; Cecconi, D.; Manfredi, M.; Marengo, E.; Boschi, F.; Riccio, M.; et al. Proteomic and Ultrastructural Analysis of Cellulite-New Findings on an Old Topic. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terranova, F.; Berardesca, E.; Maibach, H. Cellulite: Nature and aetiopathogenesis. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2006, 28, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsen, B.A.; Klinedinst, B.S.; Le, S.T.; Pappas, C.; Wolf, T.; Meier, N.F.; Lim, Y.L.; Willette, A.A. Beer, wine, and spirits differentially influence body composition in older white adults-a United Kingdom Biobank study. Obes. Sci. Pract. 2022, 8, 641–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamidis, N.; Papalexis, P.; Adamidis, S. Exploring the Link Between Metabolic Syndrome and Cellulite. Cureus 2024, 16, e63464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roure, R.; Oddos, T.; Rossi, A.; Vial, F.; Bertin, C. Evaluation of the efficacy of a topical cosmetic slimming product combining tetrahydroxypropyl ethylenediamine, caffeine, carnitine, forskolin and retinol, In vitro, ex vivo and in vivo studies. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2011, 33, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Guardo, A.; Solito, C.; Cantisani, V.; Rega, F.; Gargano, L.; Rossi, G.; Musolff, N.; Azzella, G.; Paolino, G.; Losco, L.; et al. Clinical and Ultrasound Efficacy of Topical Hypertonic Cream (Jovita Osmocell®) in the Treatment of Cellulite: A Prospective, Monocentric, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. Medicina 2024, 60, 781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertin, C.; Zunino, H.; Pittet, J.C.; Beau, P.; Pineau, P.; Massonneau, M.; Robert, C.; Hopkins, J. A double-blind evaluation of the activity of an anti-cellulite product containing retinol, caffeine, and ruscogenine by a combination of several non-invasive methods. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2001, 52, 199–210. [Google Scholar]

- Dupont, E.; Journet, M.; Oula, M.L.; Gomez, J.; Léveillé, C.; Loing, E.; Bilodeau, D. An integral topical gel for cellulite reduction: Results from a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled evaluation of efficacy. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2014, 7, 73–88. [Google Scholar]

- Ngamdokmai, N.; Waranuch, N.; Chootip, K.; Jampachaisri, K.; Scholfield, C.N.; Ingkaninan, K. Efficacy of an Anti-Cellulite Herbal Emgel: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piérard-Franchimont, C.; Piérard, G.E.; Henry, F.; Vroome, V.; Cauwenbergh, G. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of topical retinol in the treatment of cellulite. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2000, 1, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenway, F.L.; Bray, G.A.; Heber, D. Topical fat reduction. Obes. Res. 1995, 3 (Suppl. S4), 561S–568S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Artz, J.S.; Dinner, M.I. Treatment of cellulite deformities of the thighs with topical aminophylline gel. Plast. Surg. 1995, 3, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, M.K.; Pekarovic, S.; Raum, W.J.; Greenway, F. Topical fat reduction from the waist. Diabetes. Obes. Metab. 2007, 9, 300–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escalante, G.; Bryan, P.; Rodriguez, J. Effects of a topical lotion containing aminophylline, caffeine, yohimbe, l-carnitine, and gotu kola on thigh circumference, skinfold thickness, and fat mass in sedentary females. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2019, 18, 1037–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogelgesang, B.; Bonnet, I.; Godard, N.; Sohm, B.; Perrier, E. In vitro and in vivo efficacy of sulfo-carrabiose, a sugar-based cosmetic ingredient with anti-cellulite properties. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2011, 33, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupi, O.; Semenovitch, I.J.; Treu, C.; Bottino, D.; Bouskela, E. Evaluation of the effects of caffeine in the microcirculation and edema on thighs and buttocks using the orthogonal polarization spectral imaging and clinical parameters. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2007, 6, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, J.S.; Mermelstein, H.; Thomas, A.; Trow, R. Use of intense pulsed light and a retinyl-based cream as a potential treatment for cellulite: A pilot study. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2006, 5, 254–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bylka, W.; Znajdek-Awiżeń, P.; Studzińska-Sroka, E.; Brzezińska, M. Centella asiatica in cosmetology. Postepy Dermatol. Alergol. 2013, 30, 46–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkhaus, B.; Lindner, M.; Schuppan, D.; Hahn, E.G. Chemical, pharmacological and clinical profile of the East Asian medical plant Centella asiatica. Phytomedicine 2000, 7, 427–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallol, J.; Belda, M.A.; Costa, D.; Noval, A.; Sola, M. Prophylaxis of Striae gravidarum with a topical formulation. A double blind trial. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 1991, 13, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li Pomi, F.; Papa, V.; Borgia, F.; Vaccaro, M.; Allegra, A.; Cicero, N.; Gangemi, S. Rosmarinus officinalis and Skin: Antioxidant Activity and Possible Therapeutical Role in Cutaneous Diseases. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yimam, M.; Lee, Y.C.; Jiao, P.; Hong, M.; Brownell, L.; Jia, Q. A Standardized Composition Comprised of Extracts from Rosmarinus officinalis, Annona squamosa and Zanthoxylum clava-herculis for Cellulite. Pharmacognosy Res. 2017, 9, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoskin, R.; Pambianchi, E.; Pecorelli, A.; Grace, M.; Therrien, J.P.; Valacchi, G.; Lila, M.A. Novel Spray Dried Algae-Rosemary Particles Attenuate Pollution-Induced Skin Damage. Molecules 2021, 26, 3781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escudier, B.; Fanchon, C.; Labrousse, E.; Pellae, M. Benefit of a topical slimming cream in conjunction with dietary advice. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2011, 33, 334–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlosek, R.K.; Dębowska, R.M.; Lewandowski, M.; Malinowska, S.; Nowicki, A.; Eris, I. Imaging of the skin and subcutaneous tissue using classical and high-frequency ultrasonographies in anti-cellulite therapy. Skin. Res. Technol. 2011, 17, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparavigna, A.; Guglielmini, G.; Togni, S.; Cristoni, A.; Maramaldi, G. Evaluation of anti-cellulite efficacy: A topical cosmetic treatment for cellulite blemishes—A multifunctional formulation. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2011, 62, 305–316. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Bader, T.; Byrne, A.; Gillbro, J.; Mitarotonda, A.; Metois, A.; Vial, F.; Rawlings, A.V.; Laloeuf, A. Effect of cosmetic ingredients as anticellulite agents: Synergistic action of actives with in vitro and in vivo efficacy. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2012, 11, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Distante, F.; Bacci, P.A.; Carrera, M. Efficacy of a multifunctional plant complex in the treatment of the so-called ’cellulite’: Clinical and instrumental evaluation. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2006, 28, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achete de Souza, G.; de Marqui, S.V.; Matias, J.N.; Guiguer, E.L.; Barbalho, S.M. Effects of Ginkgo biloba on Diseases Related to Oxidative Stress. Planta Med. 2020, 86, 376–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertuccioli, A.; Bressan, A.; Biagi, A.; Neri, M.; Zonzini, B.G. Use of a highly standardized mixture of Vitis vinifera, Ginkgo biloba and Melilotus officinalis extracts in the treatment of cellulite: A biopharmaceutical approach. Nutrafoods 2021, 1, 220–226. [Google Scholar]

- Lis-Balchin, M. Parallel placebo-controlled clinical study of a mixture of herbs sold as a remedy for cellulite. Phytother. Res. 1999, 13, 627–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, A.; Herman, A.P. Caffeine’s mechanisms of action and its cosmetic use. Skin Pharmacol. Physiol. 2013, 26, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otlewska, A.; Baran, W.; Batycka-Baran, A. Adverse events related to topical drug treatments for acne vulgaris. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2020, 19, 513–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaminer, M.S.; Coleman, W.P., 3rd; Weiss, R.A.; Robinson, D.M.; Grossman, J. A Multicenter Pivotal Study to Evaluate Tissue Stabilized-Guided Subcision Using the Cellfina Device for the Treatment of Cellulite With 3-Year Follow-Up. Dermatol. Surg. 2017, 43, 1240–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiBernardo, B.E.; Sasaki, G.H.; Katz, B.E.; Hunstad, J.P.; Petti, C.; Burns, A.J. A Multicenter Study for Cellulite Treatment Using a 1440-nm Nd:YAG Wavelength Laser with Side-Firing Fiber. Aesthet. Surg. J. 2016, 36, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman-Janette, J.; Joseph, J.H.; Kaminer, M.S.; Clark, J.; Fabi, S.G.; Gold, M.H.; Goldman, M.P.; Katz, B.E.; Peddy, K.; Schlessinger, J.; et al. Collagenase Clostridium Histolyticum-aaes for the Treatment of Cellulite in Women: Results From Two Phase 3 Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trials. Dermatol. Surg. 2021, 47, 649–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenc, Z.P.; Black, J.M.; Cheung, J.S.; Chiu, A.; Del Campo, R.; Durkin, A.J.; Graivier, M.; Green, J.B.; Kwok, G.P.; Marcus, K.; et al. Skin Tightening With Hyperdilute CaHA: Dilution Practices and Practical Guidance for Clinical Practice. Aesthet. Surg. J. 2022, 42, NP29–NP37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swearingen, A.; Medrano, K.; Ferzli, G.; Sadick, N.; Arruda, S. Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study of Poly-L-Lactic acid for Treatment of Cellulite in the Lower Extremities. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2021, 20, 529–533. [Google Scholar]

- Russe-Wilflingseder, K.; Russe, E.; Vester, J.C.; Haller, G.; Novak, P.; Krotz, A. Placebo controlled, prospectively randomized, double-blinded study for the investigation of the effectiveness and safety of the acoustic wave therapy (AWT(®)) for cellulite treatment. J. Cosmet. Laser Ther. 2013, 15, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knobloch, K.; Kraemer, R. Extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT) for the treatment of cellulite—A current metaanalysis. Int. J. Surg. 2015, 24 Pt B, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casabona, G.; Pereira, G. Microfocused Ultrasound with Visualization and Calcium Hydroxylapatite for Improving Skin Laxity and Cellulite Appearance. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2017, 5, e1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busso, M.; Born, T. Combined Monopolar Radiofrequency and Targeted Pressure Energy for the Treatment and Improvement of Cellulite Appearance on Multiple Body Parts. J. Clin. Aesthet. Dermatol. 2023, 16, 35–39. [Google Scholar]

- Bennardo, L.; Fusco, I.; Cuciti, C.; Sicilia, C.; Salsi, B.; Cannarozzo, G.; Hoffmann, K.; Nisticò, S.P. Microwave Therapy for Cellulite: An Effective Non-Invasive Treatment. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pianez, L.R.; Custódio, F.S.; Guidi, R.M.; de Freitas, J.N.; Sant’Ana, E. Effectiveness of carboxytherapy in the treatment of cellulite in healthy women: A pilot study. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2016, 9, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, D.S.; Boen, M.; Fabi, S.G. Cellulite: Patient Selection and Combination Treatments for Optimal Results-A Review and Our Experience. Dermatol. Surg. 2019, 45, 1171–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassem, A.A.; Asfour, M.H.; Abd El-Alim, S.H.; Khattab, M.A.; Salama, A. Topical caffeine-loaded nanostructured lipid carriers for enhanced treatment of cellulite: A 32 full factorial design optimization and in vivo evaluation in rats. Int. J. Pharm. 2023, 643, 123271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouad, S.A.; Badr, T.A.; Abdelbary, A.; Fadel, M.; Abdelmonem, R.; Jasti, B.R.; El-Nabarawi, M. New Insight for Enhanced Topical Targeting of Caffeine for Effective Cellulite Treatment: In Vitro Characterization, Permeation Studies, and Histological Evaluation in Rats. AAPS PharmSciTech 2024, 25, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, L.M.; El-Refaie, W.M.; Elnaggar, Y.S.R.; Abdelkader, H.; Al Fatease, A.; Abdallah, O.Y. Non-invasive caffeinated-nanovesicles as adipocytes-targeted therapy for cellulite and localized fats. Int. J. Pharm. X 2024, 7, 100236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albash, R.; Abdelbari, M.A.; Elbesh, R.M.; Khaleel, E.F.; Badi, R.M.; Eldehna, W.M.; Elkaeed, E.B.; El Hassab, M.A.; Ahmed, S.M.; Mosallam, S. Sonophoresis mediated diffusion of caffeine loaded Transcutol® enriched cerosomes for topical management of cellulite. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2024, 201, 106875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandran, R.; Mohd Tohit, E.R.; Stanslas, J.; Salim, N.; Tuan Mahmood, T.M. Investigation and Optimization of Hydrogel Microneedles for Transdermal Delivery of Caffeine. Tissue Eng. Part C Methods 2022, 28, 545–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hameed, H.I.; Al-Mayahy, M.H. Combined approach of nanoemulgel and microneedle pre-treatment as a topical anticellulite therapy. ADMET DMPK 2024, 12, 903–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pareek, A.; Kapoor, D.U.; Yadav, S.K.; Rashid, S.; Fareed, M.; Akhter, M.S.; Muteeb, G.; Gupta, M.M.; Prajapati, B.G. Advancing Lipid Nanoparticles: A Pioneering Technology in Cosmetic and Dermatological Treatments. Colloid Interface Sci. 2025, 64, 100814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Zhao, N.; Song, Q.; Du, Z.; Shu, P. Topical retinoids: Novel derivatives, nano lipid-based carriers, and combinations to improve chemical instability and skin irritation. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2024, 23, 3102–3115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, J.; Hoq, M.N.; Mulcahy, J.; Tofail, S.A.M.; Gulshan, F.; Silien, C.; Podbielska, H.; Akbar, M.M. Implementation of artificial intelligence and non-contact infrared thermography for prediction and personalized automatic identification of different stages of cellulite. EPMA J. 2020, 11, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Koban, K.C.; Schenck, T.L.; Giunta, R.E.; Li, Q.; Sun, Y. Artificial Intelligence in Dermatology Image Analysis: Current Developments and Future Trends. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 6826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, K.; Zappia, E.; Bonan, P.; Coli, F.; Bennardo, L.; Clementoni, M.T.; Pedrelli, V.; Piccolo, D.; Poleva, I.; Salsi, B.; et al. Microwave-Energy-Based Device for the Treatment of Cellulite and Localized Adiposity: Recommendations of the “Onda Coolwaves” International Advisory Board. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Guardo, A.; Trovato, F.; Cantisani, C.; Dattola, A.; Nisticò, S.P.; Pellacani, G.; Paganelli, A. Artificial Intelligence in Cosmetic Formulation: Predictive Modeling for Safety, Tolerability, and Regulatory Perspectives. Cosmetics 2025, 12, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, H.; Virk, A.S.; Virk, S.S.; Akin-Ige, F.; Amin, S. Applications of artificial intelligence and machine learning on critical materials used in cosmetics and personal care formulation design. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2024, 73, 101847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study (Design, Duration) | N | Population/Regimen | Main Outcomes | Safety | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Di Guardo et al. (DB-RCT, 12 wk; hypertonic NaCl vs. placebo) | 30 | Grade II–III cellulite | ↓ Thigh circumference (up to −2.1 cm); US: ↓ hypodermal thickness, improved echogenicity; more pronounced effect in BMI ≥ 25 | No AEs | [16] |

| Roure et al. (DB-RCT, 12 wk; THPE + caffeine + carnitine + forskolin + retinol) | 78 | Women, BID | ↓ Abdomen/waist (~−1 cm); improved hydration; clinical grading: orange-peel & stubborn cellulite improved; 79% vs. 56% responders | Well tolerated | [15] |

| Bertin et al. (DB-RCT; retinol + caffeine + ruscogenin) | 46 | Healthy women | Improved macro-relief, dermo-hypodermal & biomechanical metrics; ↑ microcirculation; active > placebo for orange-peel reduction | No AEs | [17] |

| Dupont (DB-RCT, 12 wk; multi-active gel) | 44 | Normal–overweight | ↓ Abdomen (−1.1 cm), thighs (−0.8 cm); tonicity ↑, orange-peel & stubborn cellulite ↓; 81% vs. 32% responders | Well tolerated | [18] |

| Ngamdokmai et al. (DB-RCT, 12 wk; herbal emgel) | 18 | Severe cellulite | ↓ Cellulite severity scores; modest cm changes both arms; patient satisfaction higher with active | No AEs | [19] |

| Piérard-Franchimont et al. (Split-body DB-RCT, 6 mo; topical retinol) | 15 | 26–44 y, mild–moderate | ↑ Elasticity (+10.7%), ↓ viscosity (−15.8%); histology: more FXIIIa+ dendrocytes; benefit mainly in mild cellulite | No AEs | [20] |

| Reference | Design/n/Duration | Active(s) & Class | Anti-inflammatory/Antioxidant Evidence | Clinical/Imaging Endpoints | Safety |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UP1307 screening (preclinical) [32] | In vitro (3T3-L1), in vivo Croton oil rat model | Rosmarinus officinalis, Annona squamosa, Zanthoxylum clava-herculis | Rosemary: −82% platelet aggregation, −71.8% NO inhibition, −91.8% radical scavenging; A. squamosa −68.8% lipid accumulation; Zanthoxylum improved microcirculation | — | — |

| Hoskin 2021 (ex vivo) [33] | Ex vivo human biopsies + diesel exhaust | Spirulina–rosemary spray-dried particles | ↓ 4-HNE adducts, ↓ MMP-9, preserved filaggrin | Prevention of pollution-induced oxinflammation | Well tolerated |

| Escudier 2011 [34] | Split-body RCT, n = 50, 4 wk | Multi-active slimming cream + diet | Rationale: antioxidant/vascular | Early cellulite score reduction (p < 0.001), tonicity ↑ (Ur, p = 0.006), thigh/hip/buttock volume ↓ (3D, all p ≤ 0.012), upper thigh −0.33 cm vs. −0.18 cm (p = 0.037) | Good tolerability |

| Mlosek 2011 [35] | RCT, cream n = 45 vs. placebo n = 16, 30 d | Cucurbita pepo, cranberry, herbal blend | ↑ Dermal echogenicity (p < 0.0001), edema prevalence ↓ (75.6%→24.4%, p < 0.0001) | Subcutaneous thickness −18.2%, dermis + subcutis −15.6%, epidermis −17%, dermis −18%, fascicle shortening −41%, thigh circumference −2.16 cm | No adverse events |

| Sparavigna 2011 [36] | Split-body, n = 23, 4 wk | Visnadine 0.25%, Ginkgo 0.5%, Escin 1% | Escin: anti-edema, anti-inflammatory; Ginkgo flavonoids antioxidant | Orange-peel ↓ (−14% upper, −23% mid-thigh, both p < 0.05), pain at pinch −82–100%, cellulite thermography −17%, circumferences −0.9/1.2/0.6 cm | Well tolerated |

| Al-Bader 2012 [37] | Split-body, 12 wk | Fucus, Furcellaria, retinoid, CLA, glaucine | In vitro: synergistic glycerol release; pro-collagen I ↑ 211–228% | Clinical cellulite grading −1.7 vs. −0.9 (vehicle) at 12 wk (p < 0.0001); ultrasound: adipose thickness ↓ | Safe |

| Brinkhaus 2000 [29] | Oral RCT, n = 35, 90 d | C. asiatica extract | Anti-inflammatory, antifibrotic | Adipocyte diameter ↓, interadipocyte fibrosis ↓ vs. placebo | Well tolerated |

| Piérard-Franchimont 2000 [20] | Split-body RCT, n = 15, 6 mo | Retinol cream (0.5 μM equivalent) | Increased FXIIIa+ dendrocytes (×2–5) in dermis/hypodermis | Elasticity ↑ 10.7%, viscosity ↓ 15.8%; effects greater in mild cellulite | No safety issues |

| Fink 2006 [27] | Pilot, n = 20, 12 wk | IPL ± retinyl cream | ECM remodeling via collagen deposition | 60% of patients reported ≥50% self-improvement; ultrasound: ↑ collagen deposition | Well tolerated |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Di Guardo, A.; Trovato, F.; Cantisani, C.; Rallo, A.; Proietti, I.; Greco, M.E.; Pellacani, G.; Dattola, A.; Nisticò, S.P. Topical Management of Cellulite (Edematous-Fibro-Sclerotic Panniculopathy, EFSP): Current Insights and Emerging Approaches. J. Aesthetic Med. 2025, 1, 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/jaestheticmed1020010

Di Guardo A, Trovato F, Cantisani C, Rallo A, Proietti I, Greco ME, Pellacani G, Dattola A, Nisticò SP. Topical Management of Cellulite (Edematous-Fibro-Sclerotic Panniculopathy, EFSP): Current Insights and Emerging Approaches. Journal of Aesthetic Medicine. 2025; 1(2):10. https://doi.org/10.3390/jaestheticmed1020010

Chicago/Turabian StyleDi Guardo, Antonio, Federica Trovato, Carmen Cantisani, Alessandra Rallo, Ilaria Proietti, Maria Elisabetta Greco, Giovanni Pellacani, Annunziata Dattola, and Steven Paul Nisticò. 2025. "Topical Management of Cellulite (Edematous-Fibro-Sclerotic Panniculopathy, EFSP): Current Insights and Emerging Approaches" Journal of Aesthetic Medicine 1, no. 2: 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/jaestheticmed1020010

APA StyleDi Guardo, A., Trovato, F., Cantisani, C., Rallo, A., Proietti, I., Greco, M. E., Pellacani, G., Dattola, A., & Nisticò, S. P. (2025). Topical Management of Cellulite (Edematous-Fibro-Sclerotic Panniculopathy, EFSP): Current Insights and Emerging Approaches. Journal of Aesthetic Medicine, 1(2), 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/jaestheticmed1020010