1. Introduction

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, the need for emergency medicine (EM) doctors has become a pressing issue. A 2023 joint statement from the American College of Physicians highlighted the severe shortfall in residents to fill EM positions and suggested a number of factors driving medical students away from EM careers, including increased clinical demands, economic challenges, and the COVID-19 pandemic itself [

1]. Indeed, a large number of studies attest to the devastating effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on EM professionals and students worldwide in terms of burnout and mental health problems [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. To meet the growing demand for physicians to work in emergency care, it is vital for medical educators to explore different pedagogical approaches for motivating medical students towards careers in EM.

Within the broader field of medical education, there appears to be a growing interest in competitive learning as a way to motivate students and increase their performance. A number of studies have reported the positive impact of competitive learning methods on various disciplines within the medical curricula including immunology [

7], anatomy [

8], infection biology [

9], and surgery [

10]. Corell and colleagues concluded that competitive learning not only motivated their medical students but also improved their academic performance [

7]. A study of a national-scale, clinical skills competition for Chinese medical students also attested to the competition’s positive impact beyond just the participating students and found that it benefited all medical students by influencing downstream improvements in the medical education curriculum, resources, instructional methods, and faculty development [

11].

The Khon Kaen University International Challenge of Emergency Medicine (KKU ICEM), which was established in 2016, is a student-initiated competition for medical students, held annually at the Khon Kaen University, Thailand [

12]. The KKU ICEM is the world’s first international EM-focused competition for medical students. It was designed to foster international friendships and pave the way for future collaborative endeavors in the medical field. The competition’s structure was designed to enhance the educational experience of medical students, with a particular emphasis on stimulating a deep and practical understanding of EM. Given the universal applicability of EM—a discipline that forms the cornerstone of healthcare systems worldwide—the competition was strategically focused on this area to ensure relevance across diverse geographical contexts and, thus, appeal to medical students from various countries. The competition format included not only written assessments that tested theoretical knowledge but also a clinical practice component aimed at fostering active learning. This hands-on segment was intended to simulate real-world EM scenarios, thereby allowing participants to apply their theoretical knowledge in practical settings.

The current report aims to give an overview of the KKU ICEM and offer reflections from the perspectives of those involved in its organization and also from some participating students. Ours is the first report to introduce this novel educational initiative, which could be used as a model for similar programs and contribute to meeting the growing demand for highly trained and motivated EM professionals.

2. Participants and Event Details

2.1. Event Organization

Every year, the KKU ICEM is organized entirely by medical students of Khon Kaen University. This large-scale competition requires a dedicated year-long planning process overseen by a core team of student leaders. The KKU ICEM leadership structure begins with the selection of the president. Each year, the outgoing organizing committee chooses a successor with the endorsement of both program advisors and faculty members. This ensures continuity and fosters the transfer of valuable institutional knowledge. Following the appointment of the president, the formation of the board of directors takes place. This executive board plays a crucial role in steering the competition’s overall direction. Once this core leadership team is established, recruitment of volunteers begins. The heart of KKU ICEM lies in its passionate student volunteer force. Organizational duties are divided across approximately 20 groups, each with its own designated head. The recruitment process for these volunteer positions typically begins at least eight months before the competition date, allowing ample time for team building and training. With over 200 students actively participating, the KKU ICEM fosters a collaborative spirit and provides valuable leadership experience for these dedicated medical students.

By following a well-defined year-long process, the student-run KKU ICEM has established itself as a successful event in the international medical student competition landscape. It provides a valuable platform for medical students to test their knowledge, refine their skills, and foster lasting professional connections with their peers from around the world. The year-long organizing process can be broadly categorized into three distinct phases, described below.

2.1.1. Preparation Phase

This initial phase, which begins around 8 months before the competition, lays the groundwork for the entire competition. Key activities include (1) fundraising, securing financial resources to support the event’s operation; (2) team registration, facilitating the registration process for participating medical student teams; (3) the opening ceremony, planning and executing an engaging opening ceremony; (4) accommodations, securing and managing hotel accommodations for participants; (5) information technology services, developing and maintaining the competition’s exam program, competition program website, and other essential IT infrastructure elements; (6) graphic design, creating all the competition’s visual elements, including logos, team shirts, and event bags; (7) the academic team initiating communication with EM professors from Khon Kaen University who will subsequently engage with their counterparts from various institutions to develop questions for each stage of the competition; and (8) public relations, actively managing KKU ICEM’s social media presence to generate excitement and keep participants informed of the latest event updates.

2.1.2. Competition Phase

The competition phase is the culmination of all the planning efforts, where the competition itself comes to life. Activities during this phase include (1) competition day management, overseeing the smooth execution of the competition days and ensuring all events run according to schedule; (2) volunteer coordination, effectively managing the volunteer force to ensure all tasks are completed efficiently; and (3) backstage management, preparing and managing the backstage area to ensure a seamless competition experience.

2.1.3. Evaluation Phase

Following the competition, a dedicated evaluation phase takes place. This phase involves collecting feedback from participants on all aspects of the event. This valuable feedback is then meticulously analyzed and incorporated into the planning process for the following year’s KKU ICEM, ensuring continuous improvement and a consistently exceptional competition experience.

2.2. Competition Theme

The KKU ICEM has undergone an interesting thematic evolution since its inception. During the inaugural year, the competition encompassed the broad spectrum of EM. This initial approach allowed for a comprehensive assessment of medical student knowledge across various emergency scenarios. However, in subsequent years, a strategic shift was implemented to introduce a designated theme for each iteration of the KKU ICEM. This thematic focus serves to narrow the competition’s scope, enabling a more in-depth exploration of specific EM subfields. Recent themes chosen for the KKU ICEM have included toxicology (2022), cardiology (2023), and trauma (2024).

2.3. Participants

The KKU ICEM competition is open to medical students from medical schools within Thailand and institutions overseas. Participating universities competitively select a group of medical students to represent them. These representatives are then divided into teams of 3–5 members, in accordance with the competition’s annual rules. Each university is limited to sending a maximum of two teams to participate in the competition. In total, approximately 100 medical students participate in the competition each year. Alongside the medical students, EM doctors from each university, as well as teaching and administrative staff from Khon Kaen University, join in the KKU ICEM activities. The EM doctors act as advisors for each team and are involved in discussions after practical exams.

2.4. Components of the KKU ICEM Event

There are two main aspects to the KKU ICEM event. The first is the academic aspect, involving the competition and two workshops. The second is the cultural exchange aspect, involving cultural events and local sightseeing to foster international friendships and collaboration between the students and faculty. The KKU ICEM competition comprises preliminary, semifinal, and final rounds. While one team will go on to be crowned winners of the competition, those who do not make it through to the second or final rounds are still able to learn as spectators and garner knowledge from the exciting competition as it unfolds. In the workshops, taught by professors and EM residents from Khon Kaen University, each participant is given hands-on experience in many EM procedures (some general and some specific to that year’s theme).

The KKU ICEM is also an opportunity for all participants and staff to learn about different cultures and create lasting relationships; thus, the non-academic aspects of the program are also a vitally important component of the program. As an international event, the KKU ICEM fosters cultural exchange among the participating medical students. Beyond the competition, participants form six mixed-country teams for the workshops and mini-games. This encourages collaboration and discussion on common tasks regardless of teams and countries. One evening during the event, a cultural show dinner is held in which students from each participating country showcase their country’s culture through performances of traditional music, dance, and games. Details of the activities, ice-breaking, cultural exchange, food, sightseeing, and accommodation are meticulously planned and implemented during the whole competition. Combining both academic and non-academic elements, the KKU ICEM has proven to be a challenging, fulfilling, and enjoyable experience for all participants and organizers.

2.5. Overview of the KKU ICEM in 2024

Since its first incarnation, the KKU ICEM has been held in the form of a five-day program. To illustrate a typical program schedule, here, we describe the event as it was held in 2024.

Table 1 details the 2024 event schedule. On the first day, participants attended the opening ceremony and welcome dinner. Following the dinner, participants were grouped into six teams, each comprising a mix of students from different universities and countries. These teams collaborated on workshops and mini-games scheduled for later sessions.

During the morning session of the second day, participants took part in general emergency workshops. The workshops covered four hands-on practices: endotracheal tube (ETT) intubation/ airway management, advanced cardiovascular life support, nasal packing, and plain radiograph interpretation. In the afternoon, participants experienced traditional Thai cultural activities, including Thai massages and craft making during the Explore Khon Kaen Trip. Later that evening, the Cultural Dinner Show was held for students to share their unique cultural heritage.

On the third day, participants took part in the preliminary round of the competition, which included multiple choice question (MCQ), modified essay question (MEQ), and short answer question (SAQ) examinations. The MCQ examination was an individual online test with 120 questions on various aspects of EM, each with five answer choices. Participants must choose the best answer for each question within a 180 min time period. The MEQ examination was an individual, paper-based test. It included a clinical case composed of four questions, and participants had to submit their answers sequentially within an 8 min time frame. The SAQ examination was an individual, paper-based, and station-based test conducted at 20 stations, including 17 graded stations and 3 nongraded “rest” stations. Participants had 1.5 min to answer each question, for a total of 30 min. Following the three examinations, the individual scores were calculated, and the team scores were determined by combining the scores of all three team members.

In the morning session of the fourth day, the top eight teams with the highest cumulative team scores participated in the semifinal round, a team-based and computer-based competition. Teams were required to submit their answers to each question using the provided computers within 1.5 min, with scores calculated based on both accuracy and remaining time. Participants who did not advance to the semifinal round had the opportunity to observe this stage of the competition and listen to explanations provided by the judges from Khon Kaen University. In the afternoon, participants attended trauma emergency workshops, which emphasized patient care in trauma cases. They included extended focused assessment with sonography in trauma (eFAST), patient packaging, wound suturing, and needle thoracocentesis. Following the academic sessions, participants visited the night market in Khon Kaen and enjoyed local food and shopping on the program’s final night.

On the fifth and final day, the four teams with the highest scores in the semifinal round competed in the final round. The final round was a team-based emergency simulation examination, where finalists were expected to work as a team to manage the simulated emergency conditions in a simulated patient. Each team was given 30 min to complete the tasks. After the judges evaluated each team’s explanation and demonstration, the top three teams from the final round and individuals with the cumulative scores ranked from 1st to 18th in the preliminary round received awards during the closing ceremony. Following the ceremony, participants attended the farewell party wearing traditional clothes and celebrated together.

2.6. Program Assessment

For the purposes of this brief report, feedback was attained from the Thai organizers and Japanese participants of the 2023 or 2024 program in order to reflect upon the KKU ICEM from those dual perspectives. The students were medical students of the University of Tsukuba, a large national University in Tsukuba City, Japan. The University of Tsukuba, a partner institution of Khon Kaen University, has been sending students to participate in the KKU ICEM since the early years of the program. Feedback from the students was collected using short essays, written in English, which were read, and the content was analyzed, compared, contrasted, and discussed between the authors using a collaborative autoethnography methodology [

13,

14]. Similarly, a number of KKU ICEM organizers and faculty members of Khon Kaen University provided a written reflection on the KKU ICEM from their unique perspectives. The results of the organizer and participant feedback are presented in the

Section 3.

3. Results

3.1. Participation

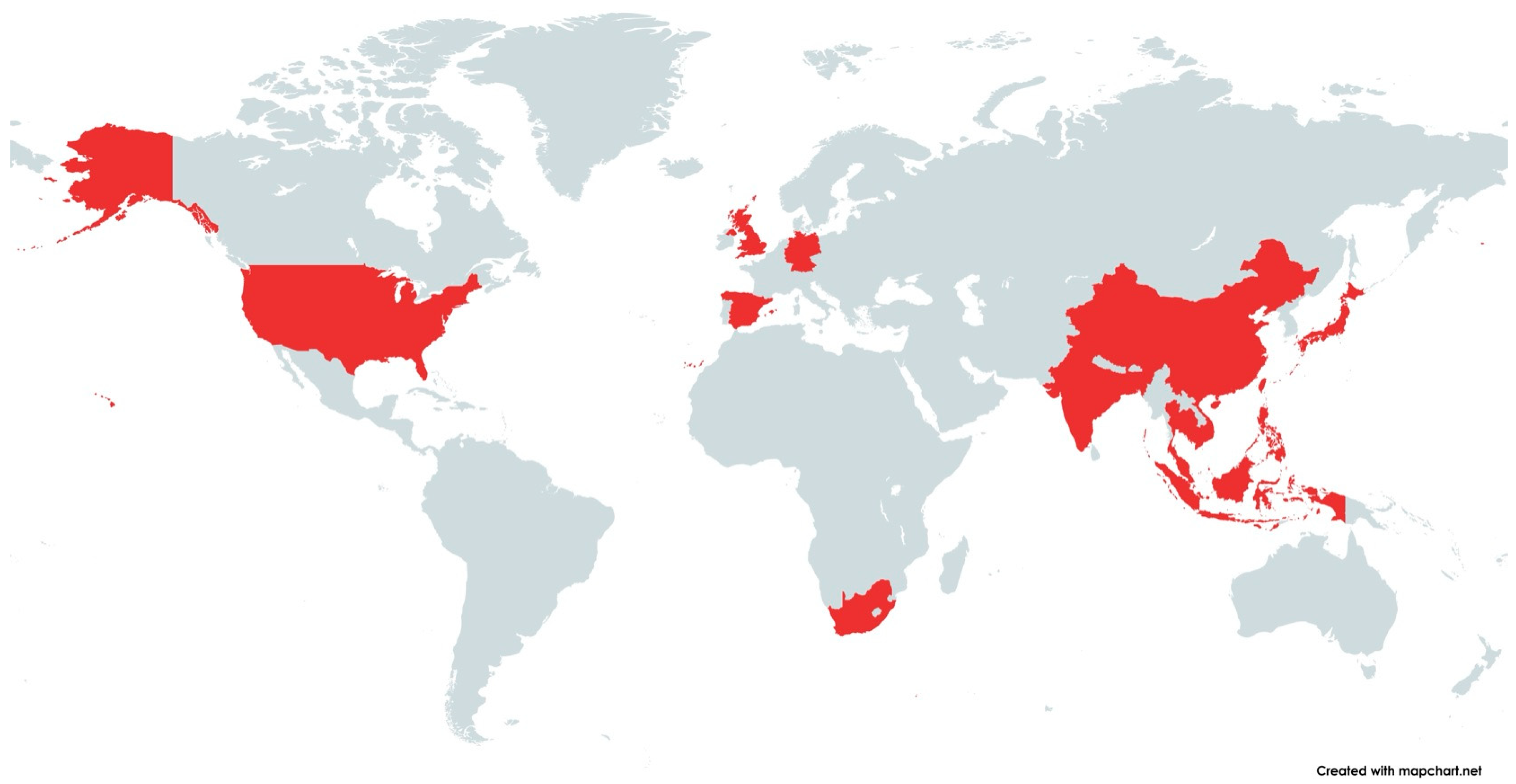

The KKU ICEM has been held annually eight times since 2016, with the exception of 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Since the first competition in 2016, a total of 18 countries, across Southeast Asia, East Asia, South Asia, Europe, North America, and Africa, have participated in the KKU ICEM; however, as shown in

Figure 1, the majority of participants have been from East and Southeast Asia.

Table 2 shows the number of teams from each country for each year of the competition. As can be seen in the table, most participants are from Thailand and international participants come from numerous countries within Asia. Prior to the pandemic, the number of teams showed an increasing trend from 23 teams from eight countries in 2016 to its height at 31 teams from ten countries in 2019. However, since 2021, the number of participating countries has decreased, with students coming only from Asian countries, despite a gradual recovery in participant numbers to pre-pandemic levels (

Table 2).

3.2. Organizer Feedback on the KKU ICEM

From the perspective of the KKU ICEM organizers, each program has been a great success. Putting aside the interruption caused by the pandemic, the KKU ICEM has shown a trend of growing and evolving each year, with more universities participating, more support garnered, and gradual improvements and refinements, building on previous experience.

One of the objectives of this event is to welcome international students from various universities to Khon Kaen University’s campus. This initiative aims to foster mutual learning while expanding and strengthening the international partnership network. Additionally, the event encourages teamwork among Khon Kaen University medical students, allowing them to gain valuable experience in managing large-scale international events, thereby enhancing their organizational and leadership skills. The collaborative nature of the event promotes unity and improves interpersonal skills, essential for working effectively in diverse, multicultural environments. Moreover, handling such an event trains our students to solve unexpected or immediate problems, a critical skill in any dynamic setting. The organizers have found that each year, the KKU ICEM program attracts more universities to participate, and the positive feedback from all participating institutions and participants indicates the program’s success in fulfilling this objective. Indeed, each year, the KKU ICEM gains increased support from both the volunteers and the faculty members of Khon Kaen University’s medical school who see the potential of the KKU ICEM and appreciate the benefits it brings to the university and to medical students around the world.

Through the evaluation phase, the KKU ICEM committees diligently incorporate feedback from participants and staff to enhance the program annually. This iterative process is crucial for continuous improvement and suggests that the KKU ICEM will continue to evolve and become more refined in the future. In conclusion, the KKU ICEM, as a student-led initiative, has been a major accomplishment of Khon Kaen University and allowed the university to showcase the potential of hundreds of aspiring medical students. The organizers believe that the KKU ICEM will grow bigger as an international competition and gain reputation across the world.

3.3. Participants’ Feedback on the KKU ICEM

Three Japanese students, who are authors of this paper and also participated in the KKU ICEM in 2023 or 2024 (one in the pre-clinical year, and the others in the mid-clinical year), wrote essays reflecting on their experiences of the program. The essays are presented in full in

Appendix A. After comparing, analyzing, and discussing the content of the essays, a number of themes and points of agreement regarding the experiences and observations emerged, which are presented in

Table 3 and the findings discussed below.

Firstly, during the students’ participation in the KKU ICEM, they discovered certain disparities between medical education in Thailand and Japan, especially when it came to practical training in EM. Prior to the competition, participants were concerned about their ability to manage emergency situations. They discovered that the primary issue was not a lack of theoretical knowledge, but rather a deficiency in practical experience. During the competition and workshop sessions, it became clear how Thai and Japanese medical students differed in their clinical proficiency. As they practiced alongside students from Khon Kaen University, they observed how skilled the Thai students were at suturing and chest-tube procedures—skills that came from having so much experience with clinical work. Thai students are afforded more opportunities for practical training than Japanese students, who are subject to regulatory limits.

Secondly, Japanese students at the KKU ICEM felt at a considerable disadvantage due to the language barrier, with English being the lingua franca of the competition. This experience brought home the importance of English language competency for gaining access to international medical education. The discrepancy in language proficiency highlights the necessity of thorough language instruction in the Japanese medical curriculum in order to equip students for international exchanges and cooperation, and even access to the latest medical knowledge published in medical journals. The types of exams and evaluation techniques used at the KKU ICEM shed light on the various approaches to medical education. Beyond the boundaries of Japanese medical education, the students’ understanding of evaluation methodologies was broadened through exposure to interactive workshops and competition stages. Furthermore, Khon Kaen University’s collaborative learning environment demonstrated the numerous advantages of practical training over theoretical training alone, especially when supported by enthusiastic instructors in cutting-edge facilities.

As the Japanese participants reflected on their experiences, they all felt inspired to suggest changes in Japanese medical education, particularly as it pertains to EM, to place greater emphasis on hands-on training and improving language and communication skills. One author pointed out the restrictive guidelines from the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare that limit the range of procedures Japanese medical students can perform (

Appendix A). These restrictions on invasive procedures hinder the ability of Japanese students to gain essential hands-on experience. The essay argued for a revision of these guidelines to allow more practical training opportunities, which are crucial for developing the necessary skills for EM.

Finally, in their essays, the students reflected on the motivational and inspirational impact of participating in the KKU ICEM. Interaction with international peers and exposure to different medical education systems provided them with invaluable insights and inspirations. They expressed feeling motivated by the skills and knowledge of other students and recognized the benefits of a collaborative and competitive learning environment. They suggest that this international exposure not only enhanced their practical skills but also broadened their perspectives on medical education and practice. Adopting a more collaborative learning environment and increasing opportunities for practical experience for medical students may better prepare those aspiring doctors to meet the changing needs of the global healthcare system.

4. Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic has emphasized the pressing need for more EM doctors, revealing significant shortfalls in resident positions. Factors deterring medical students from pursuing EM careers include increased clinical demands, economic challenges, and the pandemic’s impact on mental health [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. As medical educators seek innovative ways to motivate students towards careers in EM, the KKU ICEM presents a valuable case study in competitive learning and fruitful international exchange for medical students.

The KKU ICEM has achieved remarkable success as a student-initiated international EM competition. Competitions can serve as effective extracurricular activities, enhancing learning motivation and fostering the development of soft skills for medical students [

15]. The National Clinical Skills Competition in China led to increased medical students’ interest and enthusiasm in the competed material [

11]. In Russia, the Surgical Olympiad demonstrated positive outcomes, influencing students to pursue surgical specialties after graduation [

10]. Since 2016, the KKU ICEM has attracted participation from approximately 500 medical students across 18 countries. Each stage of the competition, organized in three rounds, works to increase the students’ motivation, their sense of anticipation, and level of competitiveness.

Previously, we reported on a small-scale annual competition that forms part of resident training at a Japanese hospital in Tsukuba City [

16]. This program, known as the Medical Rally, features a number of medical scenarios, or stations, that the students, in pairs, rotate through. A number of these stations are designed to simulate EM situations or demonstrate EM-related clinical skills. Similar to the KKU ICEM, the Medical Rally has proved useful for motivating students and making them aware of the demands on the modern physician [

16]. However, at that stage of their careers, most residents have already decided on their future direction and area of specialism. Such programs are needed at an earlier stage of medical education to inspire students towards pursuing careers in EM. The motivational impact of participating in an international competition like the KKU ICEM cannot be overstated. The students’ essays describe how interactions with peers from different countries, exposure to diverse medical practices, and the competitive environment itself were highly motivating and inspiring. These experiences not only enhanced the students’ practical skills but also broadened their perspectives on medical education and practice, reinforcing the value of international collaboration and cultural exchange.

One of the successes and key components of the KKU ICEM event is the international collaboration it fosters between the participating students and faculty, which yields benefits for the competition itself, the host university, and the participants. The KKU ICEM organizers revealed that the KKU ICEM has consistently been successful, growing each year, with the increasing trend towards greater participation from international students. Multinational participation sparks fascinating cross-cultural discussions during workshops and competitions. During the EM workshops, the participants break from their university teams to form groups with students from other countries, and the diversity of educational and cultural backgrounds results in active discussions. Additionally, during the competition, EM doctors from each participating university give feedback and advice, which further enriches the cross-cultural educational aspect of the KKU ICEM. Given variations in EM systems, needs, and education across countries [

17], the multidimensional feedback from EM doctors deepens the participants’ understanding of EM. Feedback from the participating medical students revealed that engaging in this international competition was a strongly motivational experience. In their essays, one student described how, during the workshops, the students would talk about the medical education or medical systems in their countries even during break times (

Appendix A). Furthermore, mid-clinical-year students highlighted the difference in the clinical experience system and hands-on practice opportunities:

“…participating in the event made me realize that my actual deficiency was in practical experience rather than theoretical knowledge.”

“Considering how much time and effort they are putting in practical duties around the hospital, it is not surprising that their clinical performance and success in the KKU ICEM was so remarkable compared with that of the Japanese students.”

This finding suggests the importance of interacting with students from other countries or contexts who are of the same generation as a means to reflect on one’s learning and attitudes to medicine. In particular, the face-to-face interactions that took place during workshops positively impacted their motivation to learn medicine. Collaborating with students from different countries not only promoted cultural exchange but also encouraged the acquisition of more practical communication skills and medical knowledge that could be applied in international medical fields in the future.

In terms of the empowerment of students who are considering pursuing a career in EM, the KKU ICEM offers tremendous opportunities for acquiring knowledge and mastering EM procedures. While the demand for EM doctors has increased due to COVID-19 [

1], there is a current shortage of residents to fill EM positions, and it is anticipated that the need for physicians capable of responding to unforeseen situations such as natural disasters will continue to grow. Medical students’ specialty choices often hinge on factors like clinical exposure, time spent in their desired field, and perceived prospects of success [

18]. Therefore, early exposure and positive experiences related to EM may significantly impact students’ career decisions [

19]. At the KKU ICEM, participants can gain foundational knowledge of EM during exam preparation and then systemize it to practical knowledge through the competition. Additionally, the workshops provide hands-on experiences in essential EM procedures, including ETT intubation, nasal packing, eFAST, and wound suturing. Engaging in these procedures alongside peers from diverse backgrounds during the workshops also helps build clinical confidence. This confidence, in turn, can serve as a catalyst for prompting medical students to consider EM as a career option.

Simulation plays a pivotal role in EM education, as it gives students a safe environment in which to hone their skills and expand their knowledge of EM procedures, while giving the medical educator an opportunity to appraise and evaluate them [

20,

21,

22,

23]. A key theme to emerge from the analysis of the participants’ feedback was “Recognition of Practical Experience Over Theoretical Knowledge” (

Table 3), with the students recognizing that their education had placed a greater emphasis on the latter. One participant wrote about how the KKU ICEM experience gave them access to Khon Kaen University’s teaching facilities including patient simulators, manikins, and other equipment, noting that the “facilities likely help medical students move from theoretical learning to more practical hands-on instruction” (

Appendix A). While these observations may seem quite obvious, it is interesting to note that Japan has been quite slow in its uptake of simulation-based learning. A 2009 study by Nara and colleagues, comparing medical education in Japan to other countries across the world, noted how simulation training is uncommon in Japan, finding that not all Japanese medical schools had a skills laboratory for simulation training, and of those that did, not all utilized the skills laboratory in their curriculum [

23].

On a similar note, two of the related themes that emerged from the analysis of student feedback were “Superior Practical Skills of Thai Students” and “Importance of Clinical Training Time” (

Table 3). In his study with EM services education in Asia, Hara found that Japan had the shortest duration of Advanced Emergency Medical Technician education, at 850 h, while the Philippines had the longest, at 4740 h [

24]. Likewise, one of the participants noted how “Thai medical students spend more time doing clinical training in hospitals than Japanese medical students” (

Appendix A). It is little wonder that the Japanese participants’ experience of the KKU ICEM led to the emergence of the theme of “Need for Reform in Japanese Medical Training” in their essays (

Table 3). This observation suggests that giving students the opportunity to compare and contrast medical systems and medical education curricula between different countries could be a good way to encourage their international posture.

Even though the KKU ICEM had been growing every year in terms of number of participants and growing reputation as a well-organized event with a high-level of competition, it was significantly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. In the context of medical education, the pandemic brought about substantial changes for medical students, including the large-scale introduction of online learning, disruptions in clinical rotation, and increased stress among students [

25,

26,

27,

28]. The 2020 KKU ICEM was canceled because of the pandemic; however, despite the number of participating countries diminishing post-pandemic, the 2024 competition saw participant numbers recovering to pre-pandemic levels. The KKU ICEM has played a crucial role in providing students with a long-awaited opportunity for international exchange, which had been temporarily lost. The COVID-19 pandemic has led to an increased recognition of the importance of EM and made us as a medical community acknowledge the significance of international collaboration in addressing global health crises. By providing an overview of the KKU ICEM, a successful student-initiated international EM competition, this report highlights the importance of such international initiatives.

Limitations

This report has a number of limitations that must be mentioned. Firstly, the participant feedback data are limited to three Japanese medical students from a single institution. To obtain a more detailed assessment of the program, detailed qualitative studies involving larger participant populations from different countries and institutions are necessary. In addition, mid-program surveys might help to increase the response rate and obtain more accurate data. However, the systematic, autoethnographic approach to assembling the data from these participants offers some interesting and useful observations that point to the success of the program in inspiring and motivating the students in their EM education. Secondly, the feedback from the KKU ICEM is unavoidably biased towards a favorable appraisal of the program; that said, the insights are extremely helpful to give a perspective of the purpose of the program and its positive impact upon the students and staff of Khon Kaen University’s medical school. Given the limitations of this report, the findings and conclusions presented here are not strongly evidenced. Further studies are needed to thoroughly assess the successes and areas of improvement for this program.