Abstract

Free jejunum is used for reconstruction after resection of advanced head and neck cancer. Postoperative transplanted mesenteric lymph nodes swelling is often experienced, but its clinical significance is unclear. This study included patients who underwent free jejunal reconstruction at Gifu University Hospital between March 2017 and November 2023. Regarding the size change of postoperative mesenteric lymph node and risk factors, the correlation with metastasis and prognosis was investigated. This study included 51 patients, of whom 16 cases (31.4%) had postoperative mesenteric lymph node swelling and 2 cases (3.9%) had metastasis. Only two cases with metastasis showed an increase in size of 5 mm or more. Many cases without extracapsular extension and cases of salvage surgery had postoperative mesenteric lymph node swelling (p = 0.0429, p = 0.0269). No correlation was found between postoperative mesenteric lymph node swelling and prognosis. However, because all cases with metastasis were included in cases of postoperative mesenteric lymph node swelling, this could be one factor in determining whether or not metastasis occurred. The transplanted mesenteric lymph node swelling is one of the important postoperative evaluation items, and additional evaluation such as PET-CT may be recommended.

1. Introduction

Total pharyngo-laryngectomy (TPL) and total pharyngo-laryngo-esophagectomy (TPLE) are performed for advanced cancer of the hypopharynx and larynx [1]. In addition, a free jejunal reconstruction (FJ) is performed in which the harvested jejunum is substituted for the defect in the esophagus from the pharynx and anastomosed to the cervical vessels [2,3]. The donor vessels of the jejunum are the mesenteric artery and vein that run through the mesentery, so the transplanted tissue also includes the lymph nodes of the mesentery. It is known that lymph node metastasis rarely occurs within the transplanted free tissue, and we previously reported a case of metastasis to the mesenteric lymph nodes of transplanted free jejunum [4]. Lymph node metastasis in the transplanted tissue is thought to occur due to lymph flow along the donor blood vessels after local recurrence around the resection margin [5].

Lymph node metastasis is generally accompanied by lymph node swelling, so the size of the lymph nodes is evaluated by regular imaging tests such as computed tomography (CT) scans to determine whether or not there is metastasis [6]. However, swelling of the transplanted mesenteric lymph nodes is often observed, and its management can be a clinical problem. The frequency of swelling in the transplanted mesenteric lymph nodes is 59.7%, but among them, cases of actual metastasis are rare [7]. However, the significance of lymph node swelling in transplanted tissues, its relationship with metastasis, and the risk factors remain unclear. In this study, we focused on transplanted mesenteric lymph node swelling in patients with hypopharynx cancer and larynx cancer who underwent FJ, and investigated its frequency, risk factors, and relationship with prognosis.

2. Results

2.1. Patient Characteristics

Fifty-five patients were included in this study (Table 1). The median age was 73 years, and 96% were male. The primary sites were the hypopharynx in 98% and the larynx in 1.9%. Since the procedure was targeted at advanced cancer, T3–4 accounted for 77.4%, and N1–3 accounted for 88.2%. TPL was performed in 45 cases (88.2%) and TPLE in 6 cases (11.8%), with 3 salvage cases (5.9%) included. Total thyroidectomy was performed in 15 cases (29.4%), lobectomy in 32 cases (62.7%). The median postoperative follow-up duration was 25.6 months (range: 1–88.6 months). There were 5 cases (9.1%) of local recurrence, 13 cases (25.4%) of cervical lymph node recurrence, and 11 cases (21.6%) of distant metastasis (with overlap).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

2.2. Cases with Postoperative Mesenteric Lymph Node Swelling/Metastasis

The vascular pedicle of the jejunum was the second jejunal artery (J2) in 6 cases (11.8%), the third jejunal artery (J3) in 23 cases (45.1%), and the fourth jejunal artery (J4) in 2 cases (3.9%) (Table 2). The median time at which the largest postoperative mesenteric lymph node was observed on CT was 8 months (range, 3 to 13 months) after surgery. 16 cases (31.4%) had swelling of the transplanted mesenteric lymph nodes after surgery, and 2 cases (3.9%) had metastasis in the transplanted mesenteric lymph nodes. Although there were cases in which multiple lymph nodes were enlarged, this study evaluated the largest lymph node regardless of the number. Table 3 summarizes the details of the 16 cases with postoperative mesenteric lymph node swelling. The size of the lymph nodes ranged from 5.0 mm to 16.9 mm, with a mean of 8.6 mm. In two cases with metastasis in the mesenteric lymph nodes, 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) accumulation was observed on positron emission tomography-CT (PET-CT), and the Standardized Uptake Value (SUV) max was 6.08 in Case 8 and 12.25 in Case 12 (Table 3). And these two cases also had local recurrences at the same time.

Table 2.

Jejunum and mesenteric lymph nodes.

Table 3.

Cases with mesenteric lymph node swelling.

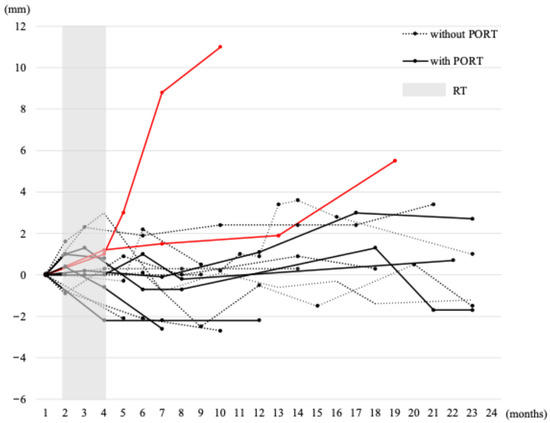

The change in size of the mesenteric lymph nodes confirmed by CT within one month after surgery is shown in Figure 1. Regardless of whether postoperative radiotherapy (PORT) was performed or not, lymph nodes in cases without metastasis showed little change in size, with most showing a change of ±2 mm or less. However, only two cases with metastasis showed an increase in size of 5 mm or more.

Figure 1.

This is a line graph showing the change in size of mesenteric lymph nodes confirmed by computed tomography within one month after surgery. The red line represents cases with mesenteric lymph node metastasis, the solid line represents cases with PORT, and the dotted line represents cases without PORT. PORT: postoperative radiotherapy.

2.3. Risk Factors for Postoperative Mesenteric Lymph Node Swelling

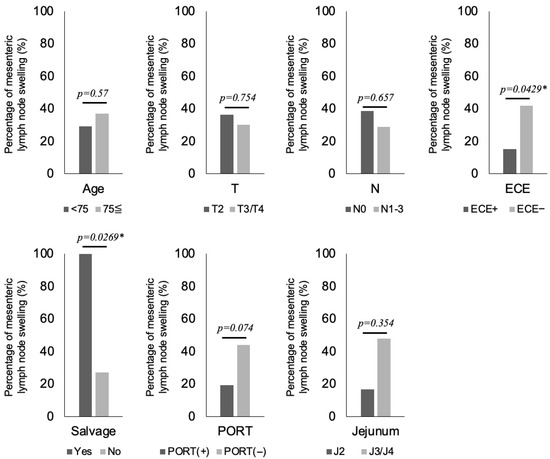

Risk factors for postoperative mesenteric lymph node swelling were evaluated. Cases without extracapsular extension (ECE) were statistically significantly more likely to have postoperative mesenteric lymph node swelling than those with ECE (with ECE: 15.0%, without ECE: 41.9%, p = 0.0429), and cases without PORT tended to have postoperative mesenteric lymph node swelling compared to cases with PORT (with PORT: 19.2%, without PORT: 44.0%, p = 0.074) (Figure 2). Multivariate analysis using age, stage, and the presence or absence of recurrence as confounding factors showed that the hazard ratio was lower in cases with ECE (HR: 0.206, 95% CI: 0.042–0.999, p = 0.049) (Table 4). Additionally, in cases where TPL/TPLE was performed as a salvage surgery for recurrence after RT, postoperative mesenteric lymph node swelling was observed in all cases (Salvage: 100.0%, not Salvage: 27.1%, p = 0.0269). No significant differences were observed in age, T classification, N classification, or vascular pedicle of the free jejunum.

Figure 2.

Eight items were evaluated as risk factors for postoperative mesenteric lymph node swelling. ECE: extracapsular extension, PORT: postoperative radiotherapy, * p < 0.05.

Table 4.

Risk factors for mesenteric lymph node swelling.

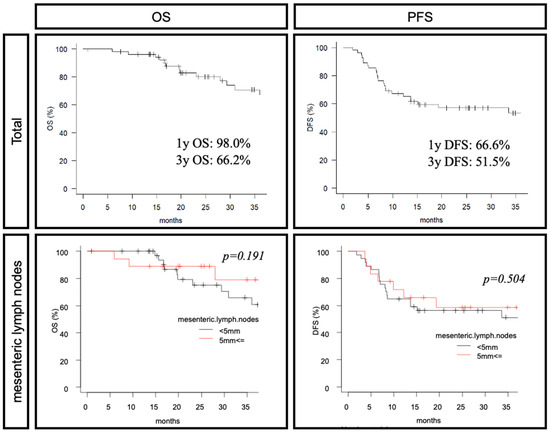

2.4. Prognosis and Postoperative Mesenteric Lymph Node Swelling

The correlation between postoperative mesenteric lymph node swelling and prognosis was investigated. The prognosis in all cases showed 1-year overall survival (OS) of 98.0%, 3-year OS of 66.2%, 1-year disease-free survival (DFS) of 66.6%, and 3-year DFS of 51.5% (Figure 3). However, no correlation was found between the presence or absence of postoperative mesenteric lymph node swelling and prognosis.

Figure 3.

The correlation between postoperative mesenteric lymph node swelling and prognosis was evaluated. OS: overall survival, DFS: disease-free survival.

3. Discussion

In this study, postoperative mesenteric lymph node swelling was observed in approximately 30% of cases, and metastasis was observed in 11% of these cases. All cases with metastasis also experienced local recurrence, and cases with local recurrence near the resection margin require careful attention. There have been 8 cases of lymph node metastasis in free tissue in 6 previous reports [4,5,8,9,10,11] (Table 5). In previous reports, local recurrence was also observed in 75% of cases. These facts may support the hypothesis that lymph node metastasis in transplanted tissues metastasizes into transplanted tissues via reperfused lymph flow after local recurrence near the resection margin. In previous reports, all cases in which preoperative PET-CT was performed showed FDG accumulation, and all cases underwent surgery, and half of the cases showed a favorable prognosis.

Table 5.

Previous reports of lymph node metastasis in transplanted free tissue.

Risk factors for postoperative mesenteric lymph node swelling were cases without ECE on postoperative pathological examination and cases with salvage surgery. The reason why postoperative mesenteric lymph node swelling was more common in cases without PORT is that the cases without ECE and the cases without PORT were almost the same patient group; in short, the presence of ECE is one of the criteria for PORT [12]. PORT may cause inhibition of lymphangiogenesis, leading to impaired lymphatic flow into the mesentery [13]. As a result, cases with PORT, which were also those with ECE, might have shown fewer cases of postoperative mesenteric lymph node swelling. In cases of salvage surgery, the resected edges of the pharynx and esophagus are post-RT and have strong inflammatory changes, which lead to a stronger reaction of the transplanted tissue (FJ) to the surrounding environment. Furthermore, since the FJ itself has not received RT and lymphangiogenesis was not suppressed, it is thought that there were more cases of postoperative mesenteric lymph node swelling in the salvage surgery group.

In addition, this study showed no correlation between the postoperative mesenteric lymph node swelling and prognosis. However, cases with postoperative mesenteric lymph node metastasis cannot be considered to have a good prognosis. All cases with postoperative mesenteric lymph node metastasis were included in the group with postoperative mesenteric lymph node swelling, with a cutoff of 5 mm, and showed an increase of 5 mm or more during follow-up. Furthermore, consistent with previous reports, cases of postoperative mesenteric lymph node metastasis showed FDG accumulation on PET-CT [4,11]. In the group with postoperative mesenteric lymph node swelling, close attention should be paid to any increase in lymph node size, and in cases with an increase in size of 5 mm or more, further evaluation such as PET-CT may be helpful in making a diagnosis. An alternative or adjunctive approach to PET-CT is ultrasound (US). It is considered a more cost-effective and less invasive option than PET-CT, but US data were not included in this study. Another method is fine-needle aspiration (FNA), but its availability is limited due to the risk of puncturing flap vessels.

The limitations of this study are that it is a single-center retrospective study with a small number of cases. Accumulating the number of cases may clarify the correlation between postoperative mesenteric lymph node size and recurrence rate and prognosis. The second is that the size of the mesenteric lymph nodes cannot be evaluated preoperatively or intraoperatively. The third issue is that the timing of the CT evaluation is not consistent. In some cases, mesenteric lymph node swelling can be identified at the time of transplantation, so it is necessary to evaluate changes in size before and after surgery, but it is difficult to identify the lymph nodes of the jejunum to be transplanted from the large abdominal cavity using a preoperative CT scan. In the future, through prospective studies such as taking baseline CT scans early after transplantation or measuring the size intraoperatively using some modality, it may be possible to perform a more detailed analysis.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Patients

This study included patients with hypopharyngeal cancer and laryngeal cancer who underwent TPL or TPLE and FJ at Gifu University Hospital from March 2017 to November 2023. All relevant clinical data were obtained from the patients’ medical records. This study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Gifu University Graduate School of Medicine (ID 2023-310).

4.2. Surgical Methods

For cases of hypopharyngeal cancer and laryngeal cancer, cervical lymph node dissection and TPL were first performed by an otolaryngologist, followed by the extraction of the jejunum by a gastrointestinal surgeon, and FJ was performed by a plastic surgeon. TPL included not only total pharyngolaryngectomy but also total pharyngolaryngectomy with cervical esophagectomy. In cases of hypopharyngeal cancer with extensive cervical esophageal invasion, in addition to FJ, total esophagectomy and gastric pull-up reconstruction (via the posterior mediastinal route) were performed by a gastrointestinal surgeon. The extent of thyroidectomy was determined based on the range of tumor infiltration. The jejunal vascular pedicle was selected from J2, J3, or J4, depending on the degree of mesenteric extension and the condition of the recipient vessels in the neck. Vascular anastomosis was generally performed using the healthy side of the neck vessels.

4.3. Evaluation

First, we evaluated the presence or absence of postoperative transplanted mesenteric lymph node swelling using CT. All CT scans were evaluated from immediately after surgery until the completion of follow-up or until death. Lymph node swelling was defined as a long diameter of 5 mm or more, and it was assessed by multiple specialists, including radiologists, otolaryngologists, and gastrointestinal surgeons. As risk factors for postoperative mesenteric lymph node swelling, we evaluated age, T classification, N classification, ECE, PORT, recurrence, vascular pedicle of the transplanted jejunum, and whether the patient underwent salvage surgery or not. Postoperative mesenteric lymph node metastasis was determined pathologically. As prognostic factors, OS and DFS were investigated.

4.4. Statistical Analysis

In the analysis of risk factors for postoperative mesenteric lymph node swelling, univariate analysis was performed using Fisher’s exact test to assess differences between the two groups, and multivariate analysis was conducted using the Cox proportional hazards model. Survival time analysis was performed using the Kaplan–Meier method, and differences between groups were analyzed using the log-rank test. Statistical analysis was performed using EZR (version 3.6.3). A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses.

5. Conclusions

This study clarified the frequency of postoperative mesenteric lymph node swelling in cases of hypopharynx cancer and larynx cancer who underwent FJ and identified its risk factors. Although no correlation with prognosis was shown because cases of metastasis occurred among those with postoperative mesenteric lymph node swelling, it is thought that this could be one factor in determining whether or not metastasis occurs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.A., T.Y., M.K. and T.O.; methodology, Y.A., T.Y. and M.K.; software, T.Y.; validation, Y.A., T.Y. and M.K.; formal analysis, Y.A., T.Y. and M.K.; investigation, Y.A., T.Y., M.K., Y.S., M.M., S.A., R.K. (Rina Kato), R.I., R.K. (Ryo Kawaura), H.O., K.T., K.M. and N.U.; resources, Y.A., T.Y. and M.K.; data curation, Y.A., T.Y. and M.K.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.A., T.Y. and M.K.; writing—review and editing, Y.A., T.Y., M.K., Y.S., K.K. and T.O.; visualization, Y.A., T.Y. and M.K.; supervision, Y.T., H.S., H.K. and T.O.; project administration, T.O.; funding acquisition, T.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Gifu University Graduate School of Medicine (ID 2023-310, approval date: 10 March 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was not sought for this study because a waiver of consent was approved by the institutional review board due to an opt-out approach.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Roux, M.; Dassonville, O.; Ettaiche, M.; Chamorey, E.; Poissonnet, G.; Bozec, A. Primary total laryngectomy and pharyngolaryngectomy in T4 pharyngolaryngeal cancers: Oncologic and functional results and prognostic factors. Eur. Ann. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Dis. 2017, 134, 151–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim Evans, K.F.; Mardini, S.; Salgado, C.J.; Chen, H.C. Esophagus and hypopharyngeal reconstruction. Semin. Plast. Surg. 2010, 24, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Kohyama, K.; Ishihara, T.; Okuda, H.; Yasue, Y.; Ogawa, T.; Shibata, H.; Kuroki, M.; Iinuma, R.; Kato, H. Factors affecting the patency of the internal jugular vein after neck dissection for malignant hypopharyngeal tumors—Significance of free jejunal flap transfer using the internal jugular vein as the recipient vein. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2025, 103, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iinuma, R.; Kato, H.; Yamada, T.; Sato, Y.; Tanaka, Y.; Kato, H.; Kuroki, M.; Shibata, H.; Kohyama, K.; Ohashi, T.; et al. Usefulness of intraoperative monitoring for mesenteric lymph node metastasis in transplanted free jejunum. Auris Nasus Larynx 2023, 50, 827–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogawa, T.; Matsuura, K.; Kato, K.; Sariishi, T.; Goto, T.; Matsumoto, K.; Saijo, S. Survival of a free jejunal graft after the resection of its nutrient vessels. Auris Nasus Larynx 2010, 37, 125–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis-Jones, H.; Colley, S.; Gibson, D. Imaging in head and neck cancer: United Kingdom National Multidisciplinary Guidelines. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2016, 130, S28–S31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, S.; Mochiki, M.; Nakao, K.; Sakamoto, T.; Ando, M.; Sugasawa, M. Clinical inspection of metastasis to the mesenteric lymph nodes in patients with hypopharyngeal cancer after pharyngolaryngectomy with free jejunal graft—136 cases. Nippon Jibiinkoka Gakkai Kaiho 2006, 109, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Kitano, D.; Hashikawa, K.; Furukawa, T.; Nomura, T.; Tamagawa, K.; Sakakibara, S.; Nibu, K.I.; Terashi, H. Salvage surgery for mesenteric lymph node metastasis by resection of the first jejunal flap and reconstruction with the second jejunal flap. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2023, 2023, rjad686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, S.; Mochiki, M.; Nakao, K.; Sakamoto, K.; Ando, M.; Sugasawa, M. A case of hypopharyngeal carcinoma metastasizing to transplanted jejunal and mesenteric lymph nodes. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2004, 76, 162–163. [Google Scholar]

- Yasuhara, K.; Uranaka, T.; Ichijo, K.; Horikiri, K. Recurrent metastasis in the mesenteric lymph node of a free jejunal graft. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2017, 89, 1045–1048. [Google Scholar]

- Matsui, Y.; Kamiyama, R.; Mitani, H.; Fukushima, H.; Sasaki, T.; Shimbashi, W.; Seto, A.; Ichikawa, K.; Tori, J.; Hihara, K.; et al. Three cases of recurrent metastasis in the mesenteric lymph node of free jejunal grafts. J. Jpn. Soc. Head Neck Surg. 2023, 33, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.Q.; OuYang, P.Y.; Zhang, B.Y.; Chen, E.N.; Xiao, S.M.; Yang, S.S.; Yang, Z.Y.; Xie, F.Y. Role of postoperative chemoradiotherapy in head and neck cancer without positive margins or extracapsular extension: A propensity score-matching analysis. Radiat. Oncol. 2022, 17, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rockson, S.G. Lymphedema. Am. J. Med. 2001, 110, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).