Behavioral Activation Therapy for Multiple Sclerosis: Potential Effects on Cognition, Neuropsychiatric Symptoms, and Quality of Life

Abstract

1. Introduction

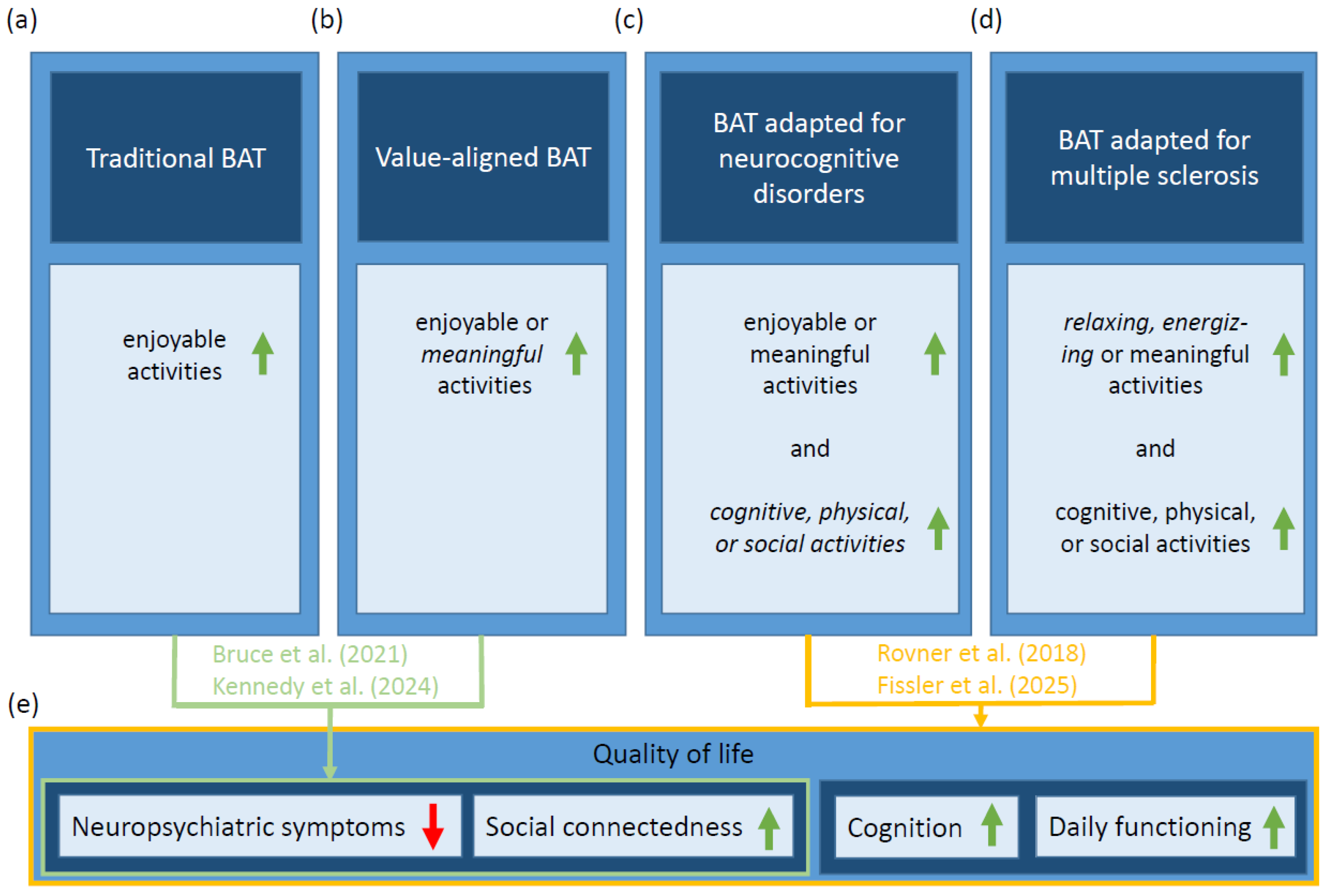

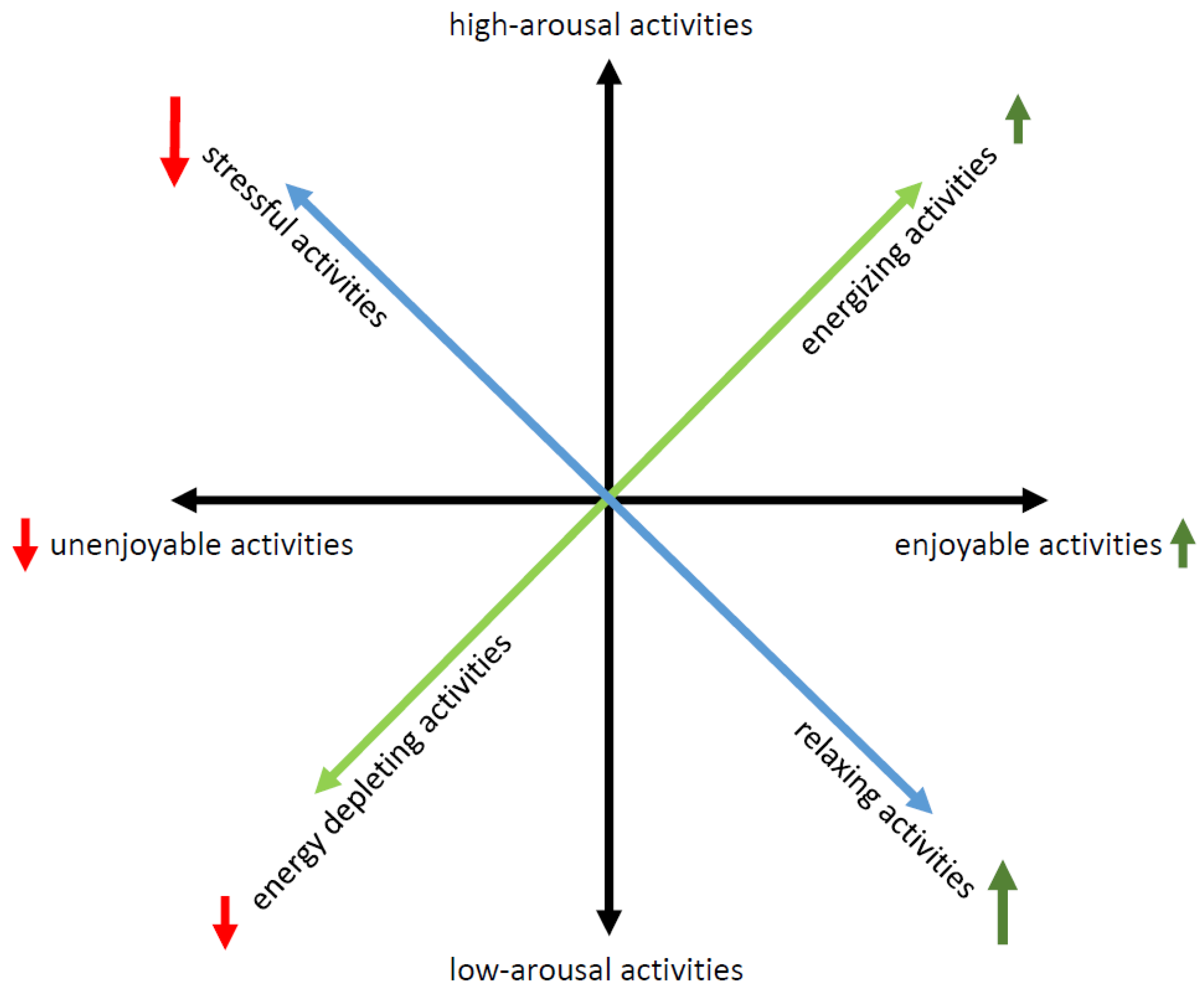

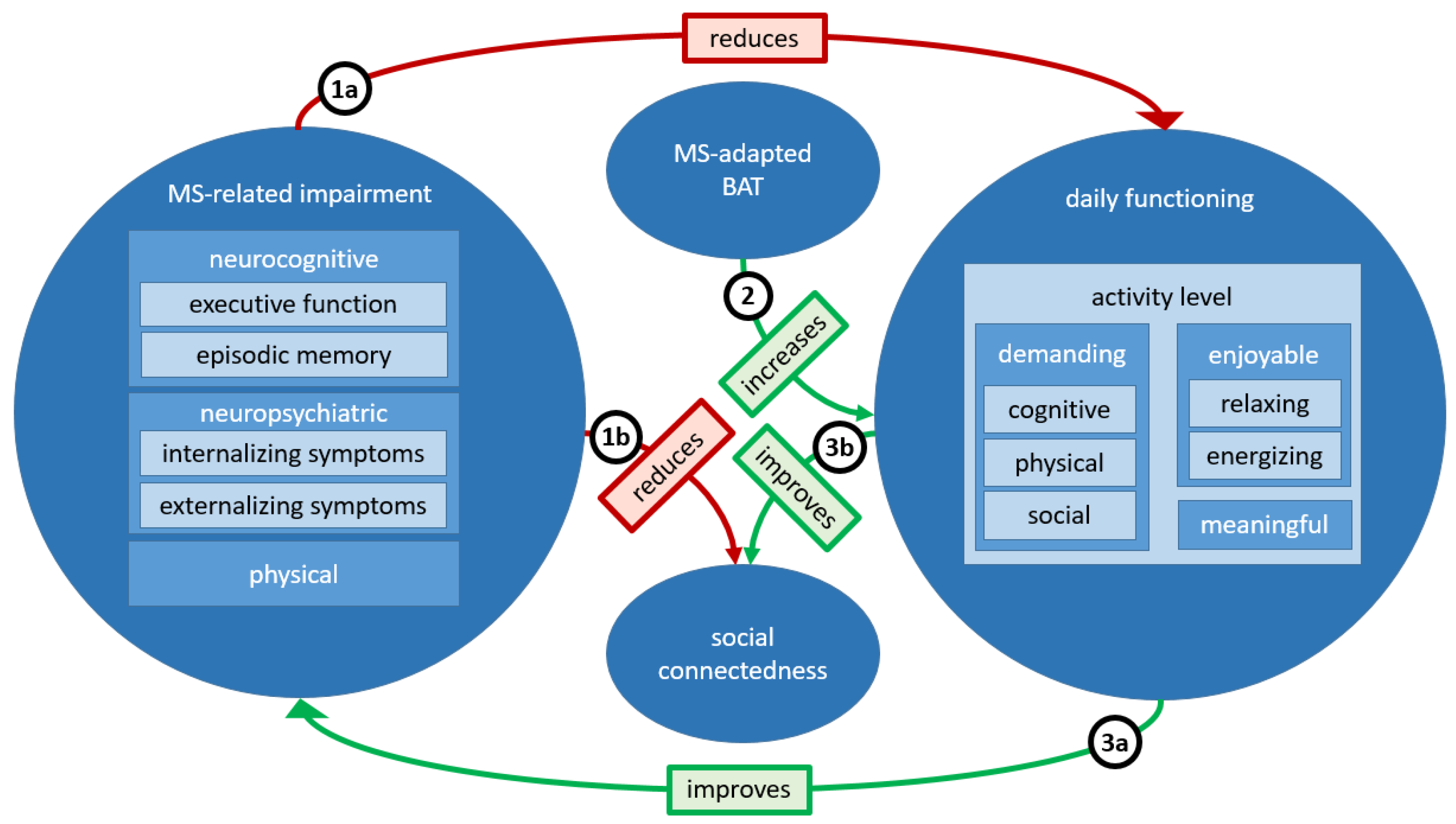

2. Proposed MS-Adapted Behavioral Activation Therapy

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lewinsohn, P.M. The Behavioral Study and Treatment of Depression. In Progress in Behavior Modification; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1975; Volume 1, pp. 19–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, N.S.; Martell, C.R.; Dimidjian, S. Behavioral Activation Treatment for Depression: Returning to Contextual Roots. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2001, 8, 255–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, D.A.; Ekers, D.; McMillan, D.; Taylor, R.S.; Byford, S.; Warren, F.C.; Barrett, B.; Farrand, P.A.; Gilbody, S.; Kuyken, W.; et al. Cost and Outcome of Behavioural Activation versus Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for Depression (COBRA): A Randomised, Controlled, Non-Inferiority Trial. Lancet 2016, 388, 871–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimidjian, S.; Hollon, S.D.; Dobson, K.S.; Schmaling, K.B.; Kohlenberg, R.J.; Addis, M.E.; Gallop, R.; McGlinchey, J.B.; Markley, D.K.; Gollan, J.K.; et al. Randomized Trial of Behavioral Activation, Cognitive Therapy, and Antidepressant Medication in the Acute Treatment of Adults with Major Depression. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2006, 74, 658–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, M.A.; Stevens, C.J.; Pepin, R.; Lyons, K.D. Behavioral Activation: Values-Aligned Activity Engagement as a Transdiagnostic Intervention for Common Geriatric Conditions. Gerontologist 2024, 64, gnad046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, D.; Litvin, B.; Allegrante, J. Behavioral Activation, Depression, and Promotion of Health Behaviors: A Scoping Review. Health Educ. Behav. 2024, 51, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, A.T.; Carl, E.; Cuijpers, P.; Karyotaki, E.; Smits, J.A.J. Looking Beyond Depression: A Meta-Analysis of the Effect of Behavioral Activation on Depression, Anxiety, and Activation. Psychol. Med. 2021, 51, 1491–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daughters, S.B.; Magidson, J.F.; Anand, D.; Seitz-Brown, C.J.; Chen, Y.; Baker, S. The Effect of a Behavioral Activation Treatment for Substance Use on Post-treatment Abstinence: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Addiction 2018, 113, 535–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, M.L.; Pepin, R.; Marti, C.N.; Stevens, C.J.; Choi, N.G. One Year Impact on Social Connectedness for Homebound Older Adults: Randomized Controlled Trial of Tele-Delivered Behavioral Activation Versus Tele-Delivered Friendly Visits. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2021, 29, 771–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovner, B.W.; Casten, R.J.; Hegel, M.T.; Leiby, B. Preventing Cognitive Decline in Black Individuals with Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Neurol. 2018, 75, 1487–1493. [Google Scholar]

- Fissler, P.; Küster, O.; Brandt, M.; Döring-Brandl, E.J.; Fründt, O.; Haeckert, J.; Haußmann, R.; Heinrich, I.; Lehfeld, H.; Miklitz, C.; et al. Effect of MindAhead’s Digital Behavioral Activation Therapy on Quality of Life in MCI and Mild Dementia. In Proceedings of the AD/PD™ 2025 International Conference on Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Diseases and Related Neurological Disorders, Vienna, Austria, 1–5 April 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Orgeta, V.; Tuijt, R.; Leung, P.; Verdaguer, E.S.; Gould, R.L.; Jones, R.; Livingston, G. Behavioral Activation for Promoting Well-Being in Mild Dementia: Feasibility and Outcomes of a Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2019, 72, 563–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, H.E.M.; Bay, C.P.; McFeeley, B.M.; Krivanek, T.J.; Daffner, K.R.; Gale, S.A. The Brain Health Champion Study: Health Coaching Changes Behaviors in Patients with Cognitive Impairment. Alzheimer’s Dement. Transl. Res. Clin. Interv. 2019, 5, 771–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, A.P.; Hartoonian, N.; Hughes, A.J.; Arewasikporn, A.; Alschuler, K.N.; Sloan, A.P.; Ehde, D.M.; Haselkorn, J.K. Physical Activity and Depression in MS: The Mediating Role of Behavioral Activation. Disabil. Health J. 2019, 12, 635–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yik, M.S.M.; Russell, J.A.; Barrett, L.F. Structure of self-reported current affect: Integration and beyond. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 77, 600–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagkouni, A.; Alevizos, M.; Theoharides, T.C. Effect of Stress on Brain Inflammation and Multiple Sclerosis. Autoimmun. Rev. 2013, 12, 947–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, J.; Abduljabbar, S.; Zhang, C.; Osier, N. The Relationship between Stress and Disease Onset and Relapse in Multiple Sclerosis: A Systematic Review. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord 2022, 67, 104142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morath, J.; Gola, H.; Sommershof, A.; Hamuni, G.; Kolassa, S.; Catani, C.; Adenauer, H.; Ruf-Leuschner, M.; Schauer, M.; Elbert, T.; et al. The Effect of Trauma-Focused Therapy on the Altered T Cell Distribution in Individuals with PTSD: Evidence from a Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2014, 54, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picard, M.; McEwen, B.S. Psychological Stress and Mitochondria: A Systematic Review. Psychosom. Med. 2018, 80, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Barcelos, I.P.; Troxell, R.M.; Graves, J.S. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Multiple Sclerosis. Biology 2019, 8, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippi, M.; Scholkmann, F.; Tachtsidis, I.; Vandersmissen, A.; Wenzel, M.; Bernhardt, M.; Neff, T.; Karabatsiakis, A.; Pruessner, J.C.; Krähenmann, R.; et al. Frontal Brain Mitochondrial Activity as a Transdiagnostic Biomarker of Psychopathology and Impaired Cognition: A Proof-of-Concept Study Using Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy. PsyArXiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, H. Modifiable Risk and Protective Factors and Biomarkers for Neuropsychiatric Symptoms and Neurocognitive Disorders. Ph.D. Thesis, Universität Ulm, Ulm, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shohani, M.; Kazemi, F.; Rahmati, S.; Azami, M. The Effect of Yoga on the Quality of Life and Fatigue in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2020, 39, 101087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, R.; Posa, S.; Langer, L.; Bruno, T.; Simpson, S.; Lawrence, M.; Booth, J.; Mercer, S.W.; Feinstein, A.; Bayley, M. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Exploring the Efficacy of Mindfulness-Based Interventions on Quality of Life in People with Multiple Sclerosis. J. Neurol. 2023, 270, 726–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cotler, J.; Holtzman, C.; Dudun, C.; Jason, L.A. A Brief Questionnaire to Assess Post-Exertional Malaise. Diagnostics 2018, 8, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Melero, S.; Caballero-Villarraso, J.; Escribano, B.M.; Galvao-Carmona, A.; Túnez, I.; Agüera-Morales, E. Impact of Cognitive Impairment on Quality of Life in Multiple Sclerosis Patients—A Comprehensive Review. JCM 2024, 13, 3321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalb, R.; Brown, T.R.; Coote, S.; Costello, K.; Dalgas, U.; Garmon, E.; Giesser, B.; Halper, J.; Karpatkin, H.; Keller, J.; et al. Exercise and Lifestyle Physical Activity Recommendations for People with Multiple Sclerosis throughout the Disease Course. Mult. Scler. 2020, 26, 1459–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, T.-M.; Peng, P.-C.; Su, Y.-K.; Lin, S.-H.; Tseng, Y.-L. Exploring Inter-Brain Electroencephalogram Patterns for Social Cognitive Assessment During Jigsaw Puzzle Solving. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2024, 32, 422–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Burgos, L.; Lozano-Rodriguez, C.; Molina, Y.; Garcia-Cabello, E.; Aciego, R.; Barroso, J.; Ferreira, D. The Effect of Chess on Cognition: A Graph Theory Study on Cognitive Data. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1407583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fissler, P.; Küster, O.C.; Laptinskaya, D.; Loy, L.S.; von Arnim, C.A.F.; Kolassa, I.-T. Jigsaw Puzzling Taps Multiple Cognitive Abilities and Is a Potential Protective Factor for Cognitive Aging. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2018, 10, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonough, I.M.; Haber, S.; Bischof, G.N.; Park, D.C. The Synapse Project: Engagement in Mentally Challenging Activities Enhances Neural Efficiency. RNN 2015, 33, 865–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Taranu, D.; Tumani, H.; Tumani, V.; Fissler, P. Behavioral Activation Therapy for Multiple Sclerosis: Potential Effects on Cognition, Neuropsychiatric Symptoms, and Quality of Life. Sclerosis 2025, 3, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/sclerosis3020012

Taranu D, Tumani H, Tumani V, Fissler P. Behavioral Activation Therapy for Multiple Sclerosis: Potential Effects on Cognition, Neuropsychiatric Symptoms, and Quality of Life. Sclerosis. 2025; 3(2):12. https://doi.org/10.3390/sclerosis3020012

Chicago/Turabian StyleTaranu, Daniela, Hayrettin Tumani, Visal Tumani, and Patrick Fissler. 2025. "Behavioral Activation Therapy for Multiple Sclerosis: Potential Effects on Cognition, Neuropsychiatric Symptoms, and Quality of Life" Sclerosis 3, no. 2: 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/sclerosis3020012

APA StyleTaranu, D., Tumani, H., Tumani, V., & Fissler, P. (2025). Behavioral Activation Therapy for Multiple Sclerosis: Potential Effects on Cognition, Neuropsychiatric Symptoms, and Quality of Life. Sclerosis, 3(2), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/sclerosis3020012