1. Introduction

American Sign Language (ASL) is a complete visual natural language with linguistic properties similar to spoken languages, with its own unique rules of grammar and syntax [

1,

2]. ASL is expressed through facial expressions, body movements, and hand gestures. ASL is primarily used in North America by individuals who are deaf or have a hearing impairment, or Deaf and Hard of Hearing (DHH) people. This, however, does not stop regular people from learning ASL to enable them to communicate with DHH people. ASL is not a universal language for DHH people; other countries have their own sign languages and dialects, just like regular spoken languages [

3].

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that over 1.5 billion people currently suffer from hearing loss, and this number is projected to grow to around 2.5 billion by 2050 [

4]. As the need and interest to learn ASL for people with hearing impairments and without grows, it becomes increasingly important to facilitate these demands proportionately [

5]. Between 2016 and 2021, the number of U.S. higher education institutions reporting enrollment in ASL increased by 44 institutions, despite the decline of total foreign language enrollment [

6]. Research by Parton [

7] found that students with hearing impairments were highly interested and preferred learning sign languages through multimedia rather than traditional face-to-face classes. The author argues that technology is an ideal platform that provides an interactive and visually engaging experience, supporting students to learn at their own pace.

Parallel to this, gamification in virtual reality (VR) combines points, levels, challenges, and feedback with immersive 3D environments to enhance engagement and learning. Recent evidence synthesizes clear benefits. A systematic review on gamified VR in education reports improvements in motivation and learning across various levels and subjects. At the same time, a meta-analysis finds that gamified VR significantly enhances immersion, motivation, and overall learning performance compared to non-gamified controls [

8].

Beyond classrooms, gamified VR is gaining traction in health and rehabilitation. A randomized controlled trial in knee osteoarthritis found that a VR-mediated, disease-specific gamified program improved pain, disability, and balance versus control; iterative VR “serious games” have likewise shown promise for hand and finger rehabilitation; and reviews of VR exergaming highlight strong effects on enjoyment and motivation to be active [

9].

Several studies have been conducted, resulting in various interpretations of VR games that support learning several sign languages [

10,

11]. Most of these studies require access to some form of Motion Capture (MoCap) technology, which might not be readily accessible or affordable to everyone [

12,

13]. To address this shortcoming, this research offers an alternative solution using Inverse Kinematics (IK) and simple controller mappings for upper-body pose and hand gesture recognition. Consistent with the inclusive aim stated in the Abstract Section—lowering hardware barriers to ASL learning—we position this work as a case study demonstrating what can be achieved with minimal, commodity hardware.

Within the TUMSphere (TUMSphere project:

https://tumsphere.se.cit.tum.de/, accessed on 21 November 2025) project, we developed a compact ASL-learning minigame that showcases our key innovations: IK-only upper-body tracking from HMD/controllers (UBIKSolver), controller-driven hand-gesture synthesis, and a deterministic pelvis-anchored pose evaluator that is runnable on commodity headsets.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 reviews related work on motion-input devices and pose-recognition techniques for sign-language learning in VR.

Section 3 outlines our methodology, which includes requirements, the IK pipeline with Upper-Body IK Solver (UBIKSolver), controller-based hand-gesture mapping, pose recognition, and game flow.

Section 4 reports results from our user study and gameplay observations.

Section 5 discusses applications, limitations, and implications of our approach.

Section 6 outlines avenues for future work. Finally,

Section 7 concludes the paper.

2. Related Work

Research on the use case of VR technology has been conducted numerous times in recent decades in different fields, such as serious games [

14], training and simulation [

15], rehabilitation and mental health therapy [

16], education and STEM labs [

17], cultural heritage and museums [

18], and accessibility and language learning [

19]. Collectively, these application domains leverage VR’s controllable immersion, embodied interaction, and repeatable scenarios to improve engagement, retention, and real-world transfer of skills. Therefore, VR is a promising way to support the learning of ASL at different levels.

2.1. Devices for Motion Input

Mapping real-life body movement into a virtual world has always been a key challenge when implementing ASL or other sign language-themed games or applications in a VR environment. Alam et al. identified three central challenges for ASL recognition: the scarcity of purpose-built datasets (especially for ASL), limited diversity and fluency among signers, and practical issues in deployment—including occlusion, lighting variability, and color ambiguity [

20].

Examining the devices used in studies on sign languages in VR environments, we can categorize these devices roughly into two groups: those that utilize state-of-the-art MoCap systems and those that utilize readily available VR headsets or hand gesture recognition devices on the market. An example of a study that uses a state-of-the-art system can be seen in a project named “ASL Champ!” [

21]. They used a state-of-the-art system during the data collection of ASL poses, which ASL teachers also used. During motion capture sessions, the teacher utilized the Vicon system, which consisted of 18 high-resolution cameras, comprising 8 T160 cameras and 10 Vero cameras, with 73 markers placed on the teacher’s fingers, hands, and body. They also used Vicon Shogun 1.7 to significantly enhance the quality of capturing body, hand, and finger motions.

In the same way, another research by Qijia et al. [

22] aimed to create a teaching environment to teach ASL. They used a Vicon system with 16 cameras and 120 markers on the signer’s ASL to capture subtle movements from each joint of the fingers. While powerful, the Vicon system is not accessible or affordable to ordinary people. Thus, research using such high-end systems primarily utilizes this technology for capturing motion data from trained professional signers, rather than for the learners’ use case. For the learners’ use case, another group of devices is more commonly used and available to the public. The team of ASL Champ! Project, for instance, also utilized Oculus Quest 2, leveraging the built-in hand-tracking capabilities with the help of the MiVRy Unreal Engine (UE) plugin for learner hand recognition. This offers significantly better accessibility than the Vicon system, albeit at the expense of hand-tracking quality.

A study by Aurelijus Vaitkevičius utilized Leap Motion, a hand-tracking device that does not require markers or gloves [

23]. Leap Motion can capture 3D hand skeleton data with relatively high accuracy in close-range and is easy to setup, making it one of the popular devices for similar research. After mounting it on an HTC Vive headset, Leap Motion can extract features such as joint positions and distances, finger angles and bending degrees, and palm orientation.

2.2. Technologies for Pose Recognition

Another key challenge in similar research is pose recognition, which involves determining the meaning of a pose after it has been extracted. Further research shows that Machine Learning (ML) and Deep Learning (DL) models are the most popular means of working with these pose data.

According to research by Gongjin Lan et al., the DL model estimates human pose by analyzing images and videos [

24]. This can be utilized by feeding a DL model with a sufficient amount of video data from signers demonstrating a pose and comparing them against poses performed by learners.

Another DL model-powered approach can also be seen in research by Vasco Xu et al. to predict a full-body pose through joint rotations and positions [

25]. With the help of DL and ML, pose evaluation can be made more lenient for learners who miss subtle movements but still nail the pose as a whole, while minimizing false positives and maintaining a relatively robust evaluation system.

Another study proposed IK-AUG, a simulation-driven data augmentation framework for sign language recognition that reconstructs gestures using inverse kinematics and then applies biomechanically constrained perturbations (e.g., depth offsets, spatial jitter, and changes in IK sensitivity) to synthesize anatomically valid sequences [

26]. Trained across five architectures (CNN3D, TCN, Transformer, Informer, Sparse Transformer), IK-AUG consistently improved validation and test accuracy versus no augmentation and versus 2D rotation baselines.

Not only with ML or DL models, but there has also been research on domain-specific gesture description languages, or GDLs [

27]. They employed forward-chaining reasoning to classify newly incoming feature data, achieving very high accuracy in classifying a dataset of 1600 recorded movement sequences, with a range of 80.5% to 98.5%.

Another similar classical approach can be seen in another research by Michalis Lazarou et al. They researched a hand gesture recognition system that completely avoids any ML approach, but instead uses shape-matching techniques from computer vision to compare hand silhouettes [

28]. The purpose was to demonstrate that classical techniques can still work when data are scarce and training is impractical. This research adopted a similar approach to classical methods, keeping things lightweight with bone rotations and position range checks to evaluate each of the poses performed by the players.

In the study by Yun et al., while MoCap, particularly IMU MoCap (Xsens), outperformed IK in pose fidelity, giving a better sense of agency, IK outperforms IMU MoCap in performing tasks that require precision, such as picking up things, likely because IK offers lower latency and minimizes positional drift [

29]. Similarly to a study by Borzelli et al. [

30], where MoCap may exhibit position biases and velocity overestimations, giving IK an edge in precision. This provides IK with a basis for comparison with MoCap technologies.

Table 1 summarizes principal applications, limitations, and key studies.

Across these studies, a clear trend emerges that every single one greatly emphasizes the movement and placement of the hands, while the movement of the whole body is an essential aspect of sign languages, including ASL, as long as the placement of the hands can be detected and the position of the rest of the body can be roughly calculated. This is the gap that this research aims to fill, as most research has focused primarily on MoCap and hand recognition technology; we strive to utilize IK and push the boundaries of this technology as far as possible.

In contrast to prior VR sign-language systems that either rely on high-end MoCap infrastructures (e.g., Vicon) for data capture and/or runtime operation [

21,

22], or hinge on dedicated hand-tracking sensors such as Leap Motion [

23], our work explores a deliberately minimalist pipeline: upper-body animation driven by UBIKSolver plus controller-based hand-gesture mappings, running on commodity standalone VR hardware. Rather than training data-hungry ML/DL models or deploying bespoke rule languages [

27,

28], we introduce a deterministic, pelvis-anchored range-checking scheme for positions, rotations, and controller-defined hand shapes that is simple to implement, portable across headsets, and transparent to debug. This design choice targets accessibility—reducing hardware cost and setup complexity—while leveraging known IK strengths in precision and latency [

29,

30]. Our contribution is therefore twofold:

A practical demonstration that IK-only upper-body tracking, combined with intuitive controller mappings, is sufficient to support a beginner-oriented ASL learning experience without full-body MoCap or camera-based hand tracking; and

An implementation blueprint (UE/MetaHuman/UBIKSolver) that others can reproduce and extend. Together, these choices position our approach as a complementary, low-barrier alternative to prior MoCap- or sensor-heavy systems, filling a gap in the literature for scalable, cost-effective VR sign language learning.

3. Methodology

This section describes the technical design and implementation of our ASL-learning module using IK.

3.1. Inverse Kinematics

We implemented the Inverse Kinematics (IK) system using the UBIKSolver plugin (UBIKSolver plugin repository:

https://github.com/JonasMolgaard/UBIKSolver, accessed on 21 November 2025) [

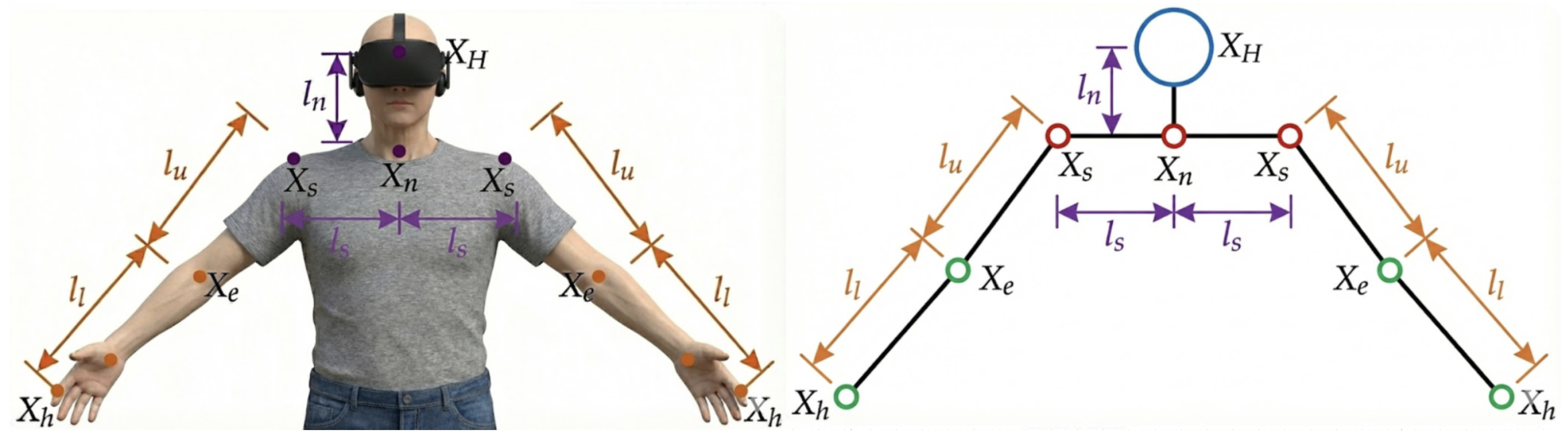

32]. The primary objective of this plugin is to estimate the position and rotation of the upper-body limbs based on the position and rotation data collected from the Head-Mounted Display (HMD) and the two controllers. As such, a kinematic chain is used as the solver calculates the solution from the head down to the hand as seen in

Figure 1. To calibrate the solver for each user’s body shape, the user’s arm length and height must be provided as input. On the other hand, the distance between the neck and the head, as well as the width of the shoulder, is fixed.

3.1.1. Neck Joint

With the assumption that the neck joint is approximately the center of rotation of the head, the neck position is calculated using a fixed offset in local HMD coordinates. It depends solely on the HMD’s position and orientation. Regarding the orientation, only the pitch and yaw of the neck are calculated. Due to the complexity of roll estimation, as well as its negligible role compared to yaw and pitch in VR applications, the roll of the neck is assumed to be 0.

Pitch of the neck refers to the movement made when we move the head vertically, such as nodding. As such, it can be assumed that pitch is primarily dependent on the distance of the HMD to the ground. When this distance becomes smaller, it means the user is looking down and vice versa.

Yaw of the neck refers to the horizontal movement of the head, such as shaking your head. Instead of using the HMD’s local orientation to derive the yaw, which causes the shoulder to move unnaturally whenever the user turns their head, the solver derives the yaw based on the direction of the hand, as can be observed in

Figure 2. In short, the yaw is derived from the sum of the normalized directions from the HMD to the motion controllers.

3.1.2. Shoulder Joint

Movement of the shoulder joints is assumed to mostly happen when the arm is fully stretched out. Firstly, a neutral shoulder position is defined as a simple translation sideways along the neck’s position. When the distance between the neutral shoulder and the hand exceeds a certain threshold, the shoulder will be rotated towards the hand, simulating a position as if the user is reaching out for something. A similar calculation is also performed for the roll of the shoulders, allowing them to move forward and upward.

3.1.3. Elbow Joint

Figure 3 illustrates how the elbow can be estimated, given the position of the hand and shoulder, by computing the angle

using the cosine rule. The more difficult part of assessing the elbow joint is to find the direction of the elbow’s orientation. In the paper, the author solves the direction of the elbow using a three-step heuristic process.

The first one is calculating elbow rotation from a relative hand position. A fundamental rule of thumb is that the elbow should always face away from the center of the body and should face backward when the hand is in front of the shoulders. This, however, still leaves a big range of rotation angles of the elbow movement.

To narrow down the rotation angle of the elbow, it employs a function inspired by neural networks to calculate the angle based on the hand position relative to the shoulder’s local coordinate system. Next is correcting the rotation singularity. Such singularity occurs when the user is stretching the arm with the hand either directly above or below the shoulder. In this state, even the slightest movement causes the arm to rotate abruptly 360 degrees around the shoulder. To fix this, as the hand approaches the vertical axis, the calculated elbow direction is linearly blended with a fixed, predefined direction. A similar correction is also applied when the hand moves behind the shoulder.

The final step is to ensure the arm pose is relaxed and does not force the wrist into an unnatural angle. The rotation of the hand relative to the forearm is checked, such that if the yaw or the roll of the wrist exceeds a predefined threshold, it applies a minor correction to the elbow’s rotation to “untwist” the arm and bring the wrist back into a comfortable range.

3.2. Functional and Non-Functional Requirements

Table 2 groups what the system

does (FR) and how

well/where it must run (NFR). The FRs define an end-to-end loop: mapping the player’s motion to the avatar, recognizing the intended ASL word, evaluating correctness with scoring, and supporting learning via visual demonstrations. The NFRs specify the target stack (UE(5+), Meta Quest 3, MetaHuman) and the desired qualities: robust and consistent pose evaluation, along with an intuitive and engaging experience for beginners. In short, the FRs specify the learning workflow, while the NFRs set the platform and usability constraints that shape our IK-centered architecture.

3.3. Transforming the Player’s Real-Life Gestures into In-Game Animations

We implement the system in Unreal Engine (UE) to minimize motion-to-photon latency and ensure stable HMD presentation, both of which directly shape users’ perceived precision and micro-corrections during pose matching [

33]. UE’s VR pipeline (native OpenXR support, async reprojection, fixed-foveation on Quest) plus its high-performance renderer help reduce presentation artifacts that can otherwise inflate pose-evaluation errors. In addition, UE’s animation stack (Animation Blueprints, Control Rig) and ecosystem support our IK setup (UBIKSolver) and MetaHuman-based visual feedback with minimal glue code, improving reproducibility across commodity headsets. These platform characteristics are therefore instrumental to the study’s goals of accessibility, precision, and low setup complexity.

3.3.1. Upper Body Animation with UBIKSolver

We used UBIKSolver for the implementation of IK. To do this, we first setup an Animation Blueprint (ABP) for the

pawn (the player-controlled character in UE) as seen in

Figure 4. For this research, we are setting up two pawns, one using the default Mannequin skeletal mesh from UE and the other using the MetaHuman skeletal mesh. These two pawns use different skeletons, so creating two distinct ABPs and animation assets is essential.

The parameter settings are critical for tuning IK animation sensitivity. Notably, “Elbow Rot from Hand Rot Alpha” controls the influence of hand rotation on elbow rotation. It is also necessary to adjust “Local Hand Offset” and “Base Char Offset,” as skeleton-specific differences can cause the hand and head meshes to deviate from the physical controller and headset positions. Further, we create a pawn blueprint, apply the ABP, and map the controller and camera transforms to the pawn’s head and hands as

Figure 5 illustrates. The hands and head follow the headset and controller poses, while UBIKSolver computes the remaining body via inverse kinematics.

3.3.2. Hand Gestures with Controller Button Mappings

Because the controllers serve as references for hand position and orientation, participants must hold them throughout the experience. This requirement constrains natural hand-gesture recognition, as unrestricted hand motion is not possible. Instead, we encode intuitive gestures via controller inputs. The Meta Quest 3 controllers feature touch- and press-sensitive buttons, allowing for various input combinations to represent hand poses.

The hand-gesture animations are scoped to the specific bones that are affected. Controller inputs are stored in variables that drive animation-blend weights, as

Figure 6 illustrates. The final blended pose is then provided to UBIKSolver.

UBIKSolver and the button mapping enable users to synthesize poses through the pawn. Button–gesture mappings are designed for intuitive correspondence—e.g., avoiding arbitrary assignments such as pressing “A” to clench a fist. The mappings are shown in

Figure 7.

3.4. Pose Recognition and Evaluation

ASL comprises facial expression, hand placement, and body movement. Facial cues are omitted here because the Meta Quest 3 lacks visual facial-tracking capability. Pose recognition can be implemented in several ways; as noted in Related Work, ML-based classifiers are standard. This study assesses pose correctness using deterministic bone-rotation and position range checks. To decouple evaluation from IK fidelity, we restrict the assessment to the positions and orientations of the hand bones; IK generates the remainder of the body and does not accurately reflect limb kinematics.

Figure 8 shows an example position check.

Using raw hand positions and rotations directly is unreliable, as start pose, player height, and other factors introduce run-to-run variance. To stabilize position checks, each hand’s world-space location is compared to the pelvis’s world-space location, treating the pelvis as the positional anchor (see

Figure 9).

For rotations, consistency is maintained if the participant faces the main console widget orthogonally since UBIKSolver anchors joint rotations to the unrotated spawn point’s forward vector. This constraint introduces a limitation discussed in the

Section 5.

An additional determinant of pose correctness is the hand gesture. In ASL, identical hand placements can convey different meanings depending on the gesture. After evaluating the gesture, along with the positions and rotations of the hand bones, we determine whether the pose is correct. These checks are performed iteratively for each candidate pose until a unique match is identified—i.e., both placement and gesture align—or no match is found. The combined procedure for checking the pose of “Please” is shown in

Figure 10.

This deterministic binary check is primarily suited for static poses. Difficulties arise for temporally sequenced poses (two or more constituent movements), such as the ASL sign “thank you.” We implement a timer that starts once the first sub-check passes (see

Figure 11) to address this, while the timer is active, the participant must complete the subsequent movement(s); otherwise, the pose resets and must be repeated.

3.5. Game Flow

With the core components implemented, we integrate them into a cohesive game loop featuring two modes. In Classic mode, the player reads a prompt on the widget console and performs the indicated pose while the system evaluates it in real-time. The loop has two phases.

Phase 1: The game selects a pose randomly; the player attempts it continuously and receives immediate feedback upon success or when the phase timer expires.

Phase 2: the system computes the round score and displays an outcome (“

Perfect!” or “

Missed”) based on Phase-1 performance. After all prompts are completed, the cumulative score is presented.

Figure 12 shows the Classic mode blueprint and

Figure 13 shows the timer-controller.

Because Classic mode evaluates poses continuously, an “almost” score is impractical: as players adjust toward the target, they would repeatedly traverse the “almost” state before achieving “perfect.” Accordingly, we introduce

Snapshot mode. As the name implies, it operates like holding a pose for a photograph. Its logic mirrors Classic mode and uses the same two-phase timers, but feedback is deferred: the pose is evaluated only after Phase 1 ends, requiring players to hold the pose until the timer expires. Players must pass the initial sub-check for dynamic poses and keep the final configuration until timeout. Outcomes are “Miss…,” “Perfect!,” and “Great!” (the “almost” tier). Both pose results and mid-pose passes trigger console notifications to keep players informed.

Figure 14 shows the Snapshot mode blueprint.

3.6. Miscellaneous

This section mentions other quality-of-life (QoL) features implemented to increase the player’s experience and ease of use.

3.6.1. MetaHuman NPC

This project implements an NPC that visually demonstrates the prompted poses. This NPC will repeat animations depending on the pose that the player needs to perform.

3.6.2. Small Widget Acting as a Mirror

The pawn animation can misrepresent real-world movement because IK may diverge from actual motion. Since pose acceptance relies solely on the in-game skeletal mesh, players must remain aware of the pawn’s state. Accordingly, we place a front-facing virtual camera and stream it to a small UI widget in real-time, enabling players to monitor their in-game posture and align movements with the evaluated pose.

3.6.3. Spawn and Despawn Mechanism for Multiple Pawns

Because UBIKSolver requires a custom pawn, we implement a mechanism to switch between TUMSphere is native pawn and the study-specific pawn, preserving loose coupling. Spawning the game pawn at a designated point also guarantees its forward vector is orthogonal to the main console widget, improving pose-recognition reliability. Using separate pawns further constrains player actions to reduce unintended behaviors: the game pawn disables locomotion, is active only during gameplay, and is despawned at completion, after which control returns to TUMSphere is pawn.

3.6.4. Game Structure

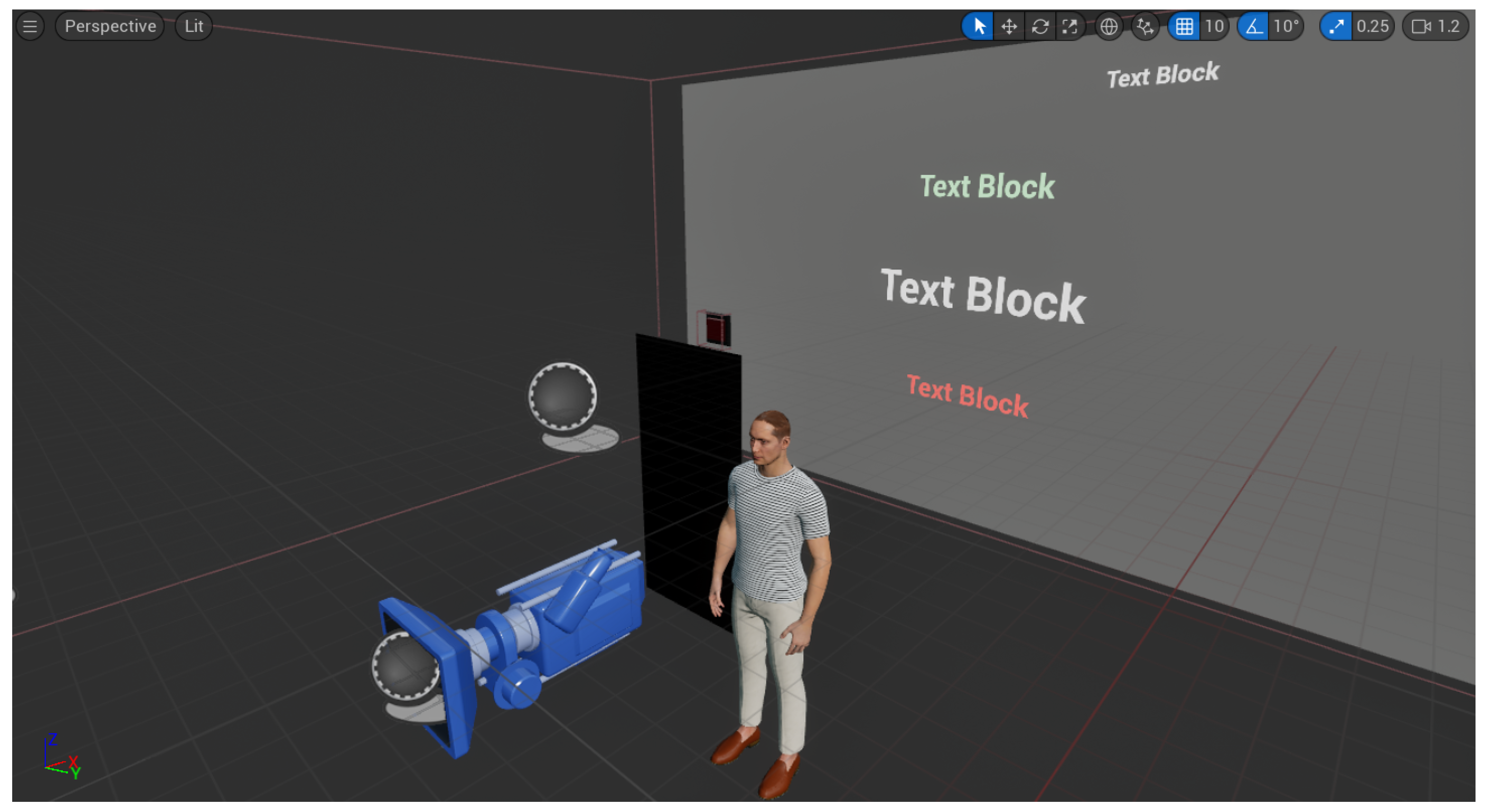

The game is encapsulated in the ASLGameManager blueprint (viewport in

Figure 15). It implements the core logic controlling the entire game flow and contains all ancillary elements, including pawn spawn points, UI widgets, start-button meshes, and the NPC. This design ensures high cohesion, low coupling, and straightforward deployment anywhere within TUMSphere.

3.6.5. Main Menu Window

After pressing the Start mesh and possessing the study-specific pawn, the player can access the main menu by pressing the Menu button. A compact widget appears in front of the camera with three controls (

Figure 16). The mode selector toggles between Classic and Snapshot, and the remaining buttons start and end the session, respectively. This interface follows established best practices for VR UI design [

34].

3.7. Experiment

3.7.1. Apparatus and Environment

We conducted the study in a quiet lab room with clearly marked play-space boundaries on the floor. Participants used a Meta Quest 3 running the standalone build of our Unreal Engine project (UE 5.5). The application targeted 90 Hz; the average framerate during tasks was 120 FPS, with frame timing logged for each frame. Hand tracking was disabled; controller tracking mode was 6DoF. We captured system logs (including timestamps, pose IDs, trial outcomes, controller, and HMD poses) in a CSV file per session, and video-recorded the headset view for audit purposes.

Licensing and third-party assets. We used engine components and character assets under their respective vendor open-source libraries under their stated licenses; we did not redistribute third-party meshes, textures, or sign recordings. If future work incorporates external sign datasets or instructor videos, we will ensure that the rights are suitable for research dissemination and include attribution and license metadata within the repository.

3.7.2. Participants

We recruited 10 university participants (five female, five male). Two participants reported prior VR experience, while several had heard of ASL; none could produce any ASL vocabulary.

All participants provided written informed consent prior to participating in the study. The consent process explained the study’s purpose, procedures, expected duration, and any reasonably foreseeable risks or benefits. Participants were informed that their involvement was voluntary, that they could decline to answer any question, and that they could withdraw at any time without penalty or loss of benefits. The consent form described how data would be collected, de-identified, and stored securely, who would have access to it, and how results might be reported. Only adults (18+) were enrolled.

Consent, privacy, and data governance. The current study logs only de-identified telemetry (timestamps, pose IDs, success flags); no audio/video was stored without explicit consent. Future releases will (i) default to on-device processing; (ii) make any video capture opt-in with clear purpose/retention windows; and (iii) publish a data schema and retention schedule. Any dataset collection will obtain written consent for the intended research/teaching use, allow withdrawal, and specify sharing terms.

3.7.3. Task and Protocol

Each session lasted 20 min, including briefing and breaks. After a 3 min calibration (height, IPD check, arm-span entry), participants completed:

Practice block (unscored): one guided attempt per sign to learn the UI.

Main task: 2 blocks × all signs. Each sign trial began with an on-screen prompt and a 3-2-1 countdown. Participants attempted the sign until either (a) the system detected a correct pose, or (b) 30 s elapsed (timeout). A 10 s rest followed each trial; a 2 min break occurred between blocks. Participants remained standing, facing a fixed forward direction indicated by a floor marker.

3.7.4. Pose Set and Counterbalancing

The in-game interface and the currently supported poses are shown in

Figure 17. The game currently supports several ASL poses, including “Hello”, “Thank you”, “Sorry”, “Please”, and “Help”.

To control order effects, we used a 5 × 5 Latin square to generate five unique pose orders. Participants were evenly assigned to orders (n = 2 per order). Block 2 reversed the order of Block 1 to reduce sequential learning effects. Out of these 5, only the “Help” pose requires both hands, while the rest can be performed with one hand. Additionally, only the “Thank you” pose is a dynamic pose, while the rest are static poses.

3.7.5. Objective Measures

Success rate (%): proportion of trials completed correctly within 30 s.

Time-to-first-success (TTFS): seconds from prompt onset to first valid detection.

Attempts: discrete attempts until success/timeout (attempt = pose-enter event separated by ≥0.75 s).

Hold stability: proportion of a 1.0 s validation window meeting all thresholds.

False positives: detections when performing a different sign on catch trials.

Tracking loss time: cumulative seconds of controller/HMD tracking loss per trial.

All raw events (timestamps, hand poses, threshold status—passed/failed) were serialized to trials.csv with columns: participant_id, block, order_id, pose_id, trial_idx, success (0/1), t_success (s), attempts (n), hold_stability, false_positive (0/1), track_loss (s), framerate_mean, and framerate_sd.

3.7.6. Statistical Analysis

For each pose, we computed the success rate as the proportion of trials completed correctly within the 30 s limit and reported 95% confidence intervals using the Wilson score interval (which is better calibrated than the Wald interval for proportions). Time-to-first-success (TTFS) was defined as the elapsed time from prompt onset to the first valid detection and was summarized as the mean ± SD over successful trials only (trials that timed out were excluded from the TTFS calculation). Attempts were the count of distinct pose-entry attempts per trial and were averaged across all trials (successes and timeouts). Hold stability was the mean fraction of the 1.0 s validation window that met all thresholds. Per-pose descriptives in

Table 3 thus show: (i) success % with Wilson 95% CIs, (ii) TTFS mean ± SD on successful trials, (iii) Attempts mean ± SD on all trials, and (iv) mean Hold stability.

4. Result

Across poses with successful trials, time-to-first-success (TTFS) ranged from 1.86 s for

Hello to 2.83 s for

Sorry. Success rates with

Wilson 95% CIs and additional descriptives are reported in

Table 3. TTFS statistics are computed over successful trials only; attempts are averaged over all trials.

Overall, three poses—Hello, Please, and Sorry—were reliably completed (100% success; Wilson 95% CIs spanning 72–100%), with TTFS means between 1.86 s (Hello) and 2.83 s (Sorry). In contrast, Thank you and Help showed 0% success (TTFS undefined), indicating recognition or execution difficulties for those signs under the current thresholds. Attempts were similar across poses (approximately 1.8–2.1 per trial), and hold stability remained high (0.82–0.90), suggesting that participants could maintain detected poses once achieved. The primary performance gap lies in achieving initial recognition for Thank you and Help.

4.1. Learning Curve and Level of Mastery

The game supports two game modes: “Classic” and “Snapshot”.

Figure 18 indicates that out of the 10 participants, only four were able to do the first part of the “Thank you” pose consistently, but not the whole pose consistently, and none were able to do the “Help” pose consistently. All of these participants also said that they could play with the “Classic” mode comfortably, but not with “Snapshot”, with some also commenting that the “Snapshot” mode was not beginner-friendly, probably because of how the “Snapshot” mode does not give immediate feedback on the player’s inputs, but instead wait until the whole timer is up, increasing the frustration of the participants who seemingly achieved a “Miss…” everytime.

This suggests that the pose evaluation system may be too strict and will not tolerate minor movement errors. As for the other three poses, all participants were able to master the “Hello” pose relatively quickly. Once they were able to consistently perform either the “Please” or “Sorry” pose, they were also able to perform the other pose relatively quickly afterwards, probably because the “Please” and “Sorry” poses require the same hand positions, with only the hand forms as the difference.

4.2. Motivation to Learn ASL

The fact that it is a VR game turns out to be motivating enough for 9 of the participants to try the game, especially those who have little to no experience playing with VR games, while one of them has an interest in gaining knowledge about ASL. Although the excitement from most participants did not stem from learning ASL itself, it creates an interesting scenario where VR games can attract players who initially have no interest in the game’s content, but rather in its mechanics, and might develop an interest later on.

4.3. Comments on the Game

The participants gave out various comments and feedback about the game, some of which were critical. A recurring comment that we receive relatively often is that the NPC’s placement is a bit too far away, and the widget showing the pawn’s avatar in real-time is too far apart from the NPC, making it difficult to match the pawn’s pose with the NPC. A participant also commented on the placement of the camera that captures scenes to be rendered in the widget showing the pawn’s avatar, which is too close to the pawn spawn point, creating a fish-eye effect when the participant reached forward with their hand, almost touching the camera.

These changes were made immediately as the participants were trying the game to accommodate their requests. This suggests a possible improvement in the shape of a customizable game layout, allowing players to move objects around according to their preferences before starting the game.

5. Discussion

Gamification has experienced a surge in popularity over the past decade. From what can be observed in

Section 4, it is evident that participants are interested in trying out the game, despite their limited knowledge of ASL itself. Furthermore, studies found that gamified approaches can trigger psychological needs such as autonomy and relatedness [

35].

Through game mechanics, learners receive immediate feedback and several small goals that provide a sense of accomplishment upon completion, which significantly increases engagement and enthusiasm [

36,

37]. Another study also suggests that a gamified approach can enhance learning outcomes, as indicated by a Hedge’s g of 0.822, a statistical measure of effect size [

38]. Through the benefits of gamification, we can discuss a couple of use cases from the results of this project.

5.1. Wider Market Reach

With the IK approach, this research aims to facilitate and reach a wider number of ASL enthusiasts who wish to learn the language. By utilizing only IK and controller buttons, our game can be played on devices that lack built-in motion capture (MoCap) or hand gesture recognition, such as the Valve Index, Pimax, PICO 4, Oculus Rift S, and several others, thereby making it playable for a wider audience.

5.2. As an Alternative Technology

As stated in

Section 2, IK has its own advantages, while the pose fidelity of IK depends strongly on implementation and fine-tuning, it also offers lower latency, resulting in more precise movements. This precision can be a crucial factor at times when performing a string of complex ASL poses, giving it a fair chance to serve as an alternative to MoCap. The author hopes that this project sparks the interest of other researchers to dig more into IK technologies and their implementation in developing environments for sign language learners.

5.3. Limitations

This project, of course, is not without its own limitations, as sometimes we have to trade off functionalities. This section will provide an objective assessment of the project’s weaknesses.

Button mapping for hand gestures: A glaring issue that needs to be disaddressed the incompleteness of theping of all possible hand gestures to all possible hand gestures. Furthermore, we designed the mappings to be intuitive, allowing players to understand instantly which buttons to press for a specific hand gesture. This makes it very hard to capture the highly expressive hand movements into combinations of buttons while keeping the sense of immersion.

UBIKSolver performance: The quality of an IK depends strongly on its implementation. UBIKSolver offers customizations to some degree in its settings, allowing users and developers to fine-tune rotation sensitivity, offsets, and other parameters. However, UBIKSolver sensitivity fine-tuning presents a rather awkward option, where a high sensitivity causes the limbs to contort wildly, and lowering the sensitivity makes the limbs too rigid and unmovable before the contortion can be fully mitigated.

This results in low pose fidelity, and while pose recognition relies solely on the hands, which are controlled directly through the controllers’ position, it makes it harder for new players to match their pawn’s actions with those of the NPC. Furthermore, the logic behind UBIKSolver renders it impossible to rotate the ASLGameManager blueprint when it is placed in the game without breaking the pose recognition logic, as it alters the base rotation values.

MetaHuman render load: MetaHuman looks esthetically good even for today’s graphical standards. However, this brings a high render load that may cause jitters and lag, especially when rendering hair, whether starting the game or after playing for some time, particularly when using VR headsets. MetaHuman also has intricate inner states that may clash with other codes when integrated into another project. This is the reason for the decision to create two types of rigorous elements in two game managers. This way, developers can easily switch between implemented pawns when one implementation creates problems.

Classical pose recognition approach: The decision not to use any ML model for pose evaluation was made to create a lightweight system that is user-friendly across various types of headsets. However, based on feedback from participants who tried the game, it follows very strict position and rotation checks, so that poses, which are supposed to be humanly passable, are being rejected by the evaluation system. This creates unnecessary difficulty and frustration for beginners who have never played any VR games or are unfamiliar with ASL.

5.4. How This Work Differs from Prior VR–ASL Systems

Beyond lowering hardware barriers, our contribution departs from prior VR–ASL projects in four ways.

Deterministic, interpretable evaluation: We replace data-hungry black-box recognizers with a pelvis-anchored, rule-based checker over hand positions/rotations and controller-defined hand shapes. This makes thresholds explicit, debuggable, and portable across headsets, and it avoids privacy and dataset issues inherent to camera-based pipelines.

IK-centered interaction fidelity: Using IK for upper-body animation exploits its low latency and drift resistance, which are advantageous for precise, time-critical pose matching; our results highlight that latency/precision, not only fidelity, shape early-stage learnability.

Design insights for feedback timing: We introduce and compare two game loops—Classic (immediate feedback) vs. Snapshot (deferred evaluation)—and show that immediate, continuous feedback is measurably more beginner-friendly, a nuance underreported in prior VR–ASL work.

Reproducible, headset-agnostic blueprint: We provide an implementation recipe (UE5/MetaHuman/UBIKSolver) with spawn/despawn pawns, a mirror widget, and deterministic pose descriptors that can be dropped into other VR worlds without room-scale calibration or external sensors. This engineering pattern emphasizes maintainability and transfer rather than lab-only capture quality.

Together, these choices position our approach as an interpretable, latency-aware, and easily redeployable alternative to sensor-heavy or ML-only systems, complementing (not competing with) high-fidelity MoCap and learned recognizers.

5.5. Accessibility and Ethics

Participatory design with DHH users. A core limitation of the present study is the absence of Deaf/Hard-of-Hearing (DHH) co-designers. Going forward, we will adopt a participatory process: (i) recruit DHH advisors and novice/intermediate ASL learners as co-design partners; (ii) compensate them for design sprints and formative usability tests; and (iii) document design decisions that result from this collaboration.

Cultural and linguistic validity of signs. ASL is not a direct encoding of English and exhibits regional/idiolectal variation. The five signs used here (Hello, Thank you, Sorry, Please, Help) were chosen as beginner vocabulary and animated from reference materials by the authors; no external sign datasets were used. Prior to any broader release we will (a) review prompts, handshapes, movement paths, and non-manual markers with certified ASL instructors and DHH reviewers; (b) flag common variants in-app (e.g., alternative movement paths/handedness) instead of enforcing a single canonical form; and (c) add provenance notes that distinguish ASL from other signed languages to avoid “one-size-fits-all” assumptions.

6. Future Work

This research demonstrates how an ASL learning VR environment can be created using only IK and controller buttons. Being in an early stage, this research naturally has many things that can be improved in future work.

A more robust, reliable, and high-fidelity IK implementation: IK with high fidelity can give players a higher sense of self, making it easier for them to match their pawn with what the NPC demonstrates. Furthermore, a more robust and reliable IK system can increase the consistency of pose recognition.

Dedicated custom controllers: One solution to the incompleteness of hand gesture mapping is a dedicated custom controller, where each button corresponds to a specific finger. The combination of these buttons can cover a broader range of hand gestures, creating a more flexible button input system. Another alternative solution is a controller that can be stuck to the back of the hand, keeping the hands free and integrating hand recognition for complete hand gesture coverage.

ML models for pose evaluation: Pose evaluation can be significantly improved by implementing ML models to give more flexible evaluations, keeping false negatives to a minimum. This reduces the player’s frustration during the learning phase and allows them to try more intricate poses, such as those that use two hands and dynamic poses, more easily. Approaches using ML models can be realized, for instance, by collecting a sufficiently large dataset of body poses and using it to train a model, which enables the accurate identification of similar poses. The advantage of using an ML approach includes better scalability and more precise criteria for what is seen as correct for a pose. This leads to keeping both false positive and false negative rates low, making it easier to implement more poses in the game. Beyond pose classifiers, LLMs integrated with multimodal signals can mediate feedback, explanations, and error recovery in VR sign-learning scenarios.

Customizable game layout: Some participants who tested the games commented on how the layout of the game, such as where the NPC or the mirror widget should be. To accommodate every request, a customizable game layout that can be arranged while in-game is undoubtedly an outstanding QoL improvement.

Scalable pose system: Currently, adding a new pose must be performed manually by adding position, rotation, and hand gesture constraints to the pose recognition logic, which can be time-consuming to fine-tune. A solution that can be explored in future work is a new system where the game prompts the teacher to demonstrate a pose multiple times, extracts multiple pose data points, and automatically trains them with an ML model.

Mentorship integration (networked). Beyond making the evaluator more tolerant of natural variation, the app could allow learners to book short, periodic check-ins with a mentor (teacher, tutor, or advanced signer). A simple network feature would allow remote mentors to join a session, watch the learner’s avatar, leave time-stamped comments, and approve or suggest fixes. An optional recording/replay would help learners review progress between check-ins and support long-term learning plans.

Exploratory “Free Mode.” Add an open practice mode where learners freely “speak” in sign and the system tries to recognize and render the detected signs as on-screen text (with a confidence indicator). This mode would encourage experimentation outside of fixed prompts, while still offering gentle guidance (e.g., “likely HELLO,” “maybe PLEASE,” or “uncertain—try raising the hand”). It would complement the structured lesson modes and help bridge toward spontaneous communication.

7. Conclusions

Inverse Kinematics (IK) technology is an underexplored territory in the world of sign language. This project demonstrates that even without motion capture (MoCap) or hand recognition, we can still create an engaging and effective environment for those interested in learning American Sign Language (ASL) in Virtual Reality.

Despite its shortcomings, especially in pose fidelity, IK proves to have higher precision than MoCap due to its lower latency, giving it an edge over MoCap implementations. Without the requirement for a built-in MoCap or hand recognition feature, this project can be played with a broader array of headsets, potentially reaching and sparking the interest of a wider audience.

Hand gesture recognition technology also goes hand in hand with body pose recognition. This research presents an alternative approach to inputting hand gestures into pawn animations, utilizing controller button combinations to map hand gestures while maintaining an intuitive interface. This allows players to easily identify which buttons to press for each hand gesture. This approach may not cover all possible hand gestures completely, depending on the controller, but it enables a more straightforward method for hand recognition by checking which buttons are pressed.

Among the 10 participants who tried the game, only 4 of them could consistently complete the first part of “Thank you”. None of them can consistently perform the “Help” and “Thank you” poses, while with enough practice, all of them can master the other three poses, namely “Hello”, “Sorry”, and “Please”. This highlights the need for improvement in the pose evaluation system by minimizing false negatives to prevent giving beginner players a sense of frustration. All of them also preferred “Classic” mode over “Snapshot” mode, indicating the importance of immediate and clear feedback for learners who have just begun to learn ASL.

This research demonstrates the potential contributions of IK technology to the world of sign language. Despite its limitations, it serves as a starting point for future work aimed at making sign language more accessible to a broader audience.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.I. and S.B.-G.; methodology, J.I.; software, J.I.; valida-tion, J.I. and S.B.-G.; formal analysis, J.I.; investigation, J.I.; resources, S.B.-G.; data curation, J.I.; writing—original draft preparation, J.I.; writing—review and editing, S.B.-G.; visualization, J.I.; supervision, S.B.-G.; project administration, S.B.-G.; funding acquisition, S.B.-G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was financially supported by the TUM Campus Heilbronn Incentive Fund 2024 of the Technical University of Munich, TUM Campus Heilbronn. We gratefully acknowledge their support, which provided the essential resources and opportunities to conduct this study.

Institutional Review Board Statement

According to § 15 of the professional code of conduct for physicians (Berufsordnung der Ärzte) and common practice in Germany, ethical review is generally not required for studies based exclusively on anonymized retrospective data and routine quality assurance measures, as these activities do not fall under the scope of the German Medical Devices Act (MPG) or the German Drug Act (AMG), and do not constitute an experimental human subject study requiring prospective ethical approval.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Liddell, S.K. American Sign Language Syntax; Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co. KG: Berlin, Germany, 2021; Volume 52. [Google Scholar]

- Neidle, C.; Nash, J.C.P. American sign language. In Sign Languages of the World: A Comparative Handbook; Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co. KG: Berlin, Germany, 2015; pp. 31–70. [Google Scholar]

- Fenlon, J.; Wilkinson, E. Sign languages in the world. Socioling. Deaf Communities 2015, 1, 5–28. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. World Report on Hearing; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Newport, E.L.; Meier, R.P. The acquisition of American sign language. In The Crosslinguistic Study of Language Acquisition; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 881–938. [Google Scholar]

- Modern Language Association. Enrollments in Languages Other Than English in United States Institutions of Higher Education, Fall 2021; Report; Modern Language Association: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Parton, B. Facilitating Exposure to Sign Languages of the World: The Case for Mobile Assisted Language Learning. J. Inf. Technol. Educ. Innov. Pract. 2014, 13, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampropoulos, G.; Kinshuk. Virtual reality and gamification in education: A systematic review. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2024, 72, 1691–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özlü, A.; Ünver, G.; Tuna, H.İ.; Menekşeoğlu, A.K. The effect of a virtual reality-mediated gamified rehabilitation program on pain, disability, function, and balance in knee osteoarthritis: A prospective randomized controlled study. Games Health J. 2023, 12, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ghoul, O.; Othman, A. Virtual reality for educating Sign Language using signing avatar: The future of creative learning for deaf students. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), Tunis, Tunisia, 28–31 March 2022; pp. 1269–1274. [Google Scholar]

- Kasapakis, V.; Dzardanova, E.; Vosinakis, S.; Agelada, A. Sign language in immersive virtual reality: Design, development, and evaluation of a virtual reality learning environment prototype. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2024, 32, 6657–6671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quandt, L. Teaching ASL signs using signing avatars and immersive learning in virtual reality. In Proceedings of the 22nd international ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility, Virtual Event, 26–28 October 2020; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Jedlička, P.; Krňoul, Z.; Kanis, J.; Železnỳ, M. Sign language motion capture dataset for data-driven synthesis. In Proceedings of the LREC2020 9th Workshop on the Representation and Processing of Sign Languages: Sign Language Resources in the Service of the Language Community, Technological Challenges and Application Perspectives, Marseille, France, 11–16 May 2020; pp. 101–106. [Google Scholar]

- Damianova, N.; Berrezueta-Guzman, S. Serious Games supported by Virtual Reality-Literature Review. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 38548–38561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, L.S.; Thomas, E.J. Navigating towards improved surgical safety using aviation-based strategies. J. Surg. Res. 2008, 145, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrezueta-Guzman, S.; Chen, W.; Wagner, S. A Therapeutic Role-Playing VR Game for Children with Intellectual Disabilities. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Metaverse Computing, Networking and Applications (MetaCom), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27–29 August 2025; pp. 389–396. [Google Scholar]

- Duarte, M.; Santos, L.; Júnior, J.G.; Peccin, M. Learning anatomy by virtual reality and augmented reality. A scope review. Morphologie 2020, 104, 254–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debailleux, L.; Hismans, G.; Duroisin, N. Exploring cultural heritage using virtual reality. In Proceedings of the Digital Cultural Heritage: Final Conference of the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Initial Training Network for Digital Cultural Heritage, ITN-DCH 2017, Olimje, Slovenia, 23–25 May 2017; Revised Selected Papers. Springer: Abingdon, UK, 2018; pp. 289–303. [Google Scholar]

- Parmaxi, A. Virtual reality in language learning: A systematic review and implications for research and practice. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2023, 31, 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.S.; De Bastion, M.; Malzkuhn, M.; Quandt, L.C. Recognizing highly variable American Sign Language in virtual reality. In Proceedings of the 8th International Workshop on Sign Language Translation and Avatar Technology (SLTAT), Rhodes, Greece, 10 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, M.S.; Lamberton, J.; Wang, J.; Leannah, C.; Miller, S.; Palagano, J.; de Bastion, M.; Smith, H.L.; Malzkuhn, M.; Quandt, L.C. ASL Champ!: A Virtual Reality Game with Deep-Learning Driven Sign Recognition. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2401.00289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Q.; Sniffen, A.; Blanchet, J.; Hillis, M.E.; Shi, X.; Haris, T.K.; Liu, J.; Lamberton, J.; Malzkuhn, M.; Quandt, L.C.; et al. Teaching american sign language in mixed reality. Proc. ACM Interac. Mob. Wearable Ubiquitous Technol. 2020, 4, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaitkevičius, A.; Taroza, M.; Blažauskas, T.; Damaševičius, R.; Maskeliūnas, R.; Woźniak, M. Recognition of American Sign Language Gestures in a Virtual Reality Using Leap Motion. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, G.; Wu, Y.; Hu, F.; Hao, Q. Vision-Based Human Pose Estimation via Deep Learning: A Survey. IEEE Trans. Hum.-Mach. Syst. 2023, 53, 253–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, V.; Gao, C.; Hoffmann, H.; Ahuja, K. MobilePoser: Real-Time Full-Body Pose Estimation and 3D Human Translation from IMUs in Mobile Consumer Devices. In Proceedings of the 37th Annual ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 13–16 October 2024; UIST ’24. pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Jing, L.; Li, X. Inverse Kinematics-Augmented Sign Language: A Simulation-Based Framework for Scalable Deep Gesture Recognition. Algorithms 2025, 18, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hachaj, T.; Ogiela, M.R. Rule-based approach to recognizing human body poses and gestures in real time. Multimed. Syst. 2013, 20, 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarou, M.; Li, B.; Stathaki, T. A novel shape matching descriptor for real-time hand gesture recognition. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2101.03923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, H.; Ponton, J.L.; Andujar, C.; Pelechano, N. Animation fidelity in self-avatars: Impact on user performance and sense of agency. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Conference Virtual Reality and 3D User Interfaces (VR), Shanghai, China, 25–29 March 2023; pp. 286–296. [Google Scholar]

- Borzelli, D.; Boarini, V.; Casile, A. A quantitative assessment of the hand kinematic features estimated by the Oculus Quest 2. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 8842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrezueta-Guzman, S.; Daya, R.; Wagner, S. Virtual Reality in Sign Language Education: Opportunities, Challenges, and the Road Ahead. Front. Virtual Real. 2025, 6, 1625910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parger, M.; Mueller, J.H.; Schmalstieg, D.; Steinberger, M. Human Upper-Body Inverse Kinematics for Increased Embodiment in Consumer-Grade Virtual Reality. In Proceedings of the 24th ACM Symposium on Virtual Reality Software and Technology, Tokyo, Japan, 28 November–1 December 2018. VRST ’18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobchyshak, O.; Berrezueta-Guzman, S.; Wagner, S. Pushing the boundaries of immersion and storytelling: A technical review of Unreal Engine. Displays 2026, 91, 103268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmedova, E.; Berrezueta-Guzman, S.; Wagner, S. Virtual Reality User Interface Design: Best Practices and Implementation. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.09358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Hew, K.F.; Du, J. Gamification enhances student intrinsic motivation, perceptions of autonomy and relatedness, but minimal impact on competency: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2024, 72, 765–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; Hew, K.F.; Huang, B. Does gamification improve student learning outcome? Evidence from a meta-analysis and synthesis of qualitative data in educational contexts. Educ. Res. Rev. 2020, 30, 100322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo-Mediavilla, L.; Basantes-Andrade, A.; Cabezas-González, M.; Casillas-Martín, S. Impact of Gamification on Motivation and Academic Performance: A Systematic Review. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Ma, S.; Shi, Y. Examining the effectiveness of gamification as a tool promoting teaching and learning in educational settings: A meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1253549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

The kinematics chain consists of the head

, neck

and, for each arm, a shoulder

, elbow

and hand

, which are at a calibrated distance

and

, the upper and lower arm lengths [

32].

Figure 1.

The kinematics chain consists of the head

, neck

and, for each arm, a shoulder

, elbow

and hand

, which are at a calibrated distance

and

, the upper and lower arm lengths [

32].

Figure 2.

Examples of hand and head configurations with the resulting neck orientation. Among these cues, hand location provides the most dependable estimate of the neck’s forward direction. In the lower-right panel, the red line depicts how this direction is clamped with respect to the head’s orientation [

32].

Figure 2.

Examples of hand and head configurations with the resulting neck orientation. Among these cues, hand location provides the most dependable estimate of the neck’s forward direction. In the lower-right panel, the red line depicts how this direction is clamped with respect to the head’s orientation [

32].

Figure 3.

A simplified diagram of the angles to be solved by the arm IK; the blue circle marks the locus of all feasible elbow positions [

32].

Figure 3.

A simplified diagram of the angles to be solved by the arm IK; the blue circle marks the locus of all feasible elbow positions [

32].

Figure 4.

ABP with UBIKSolver maps HMD/controller transforms to upper-body IK (neck–wrist), blends via Alpha, converts to local space, and outputs the pose using skeleton-specific settings.

Figure 4.

ABP with UBIKSolver maps HMD/controller transforms to upper-body IK (neck–wrist), blends via Alpha, converts to local space, and outputs the pose using skeleton-specific settings.

Figure 5.

Blueprint wires the camera and left/right controller world transforms into the ABP each tick—feeding Head/Left/Right Hand inputs—so the skeletal mesh follows the HMD/controllers while UBIKSolver solves the remaining upper body.

Figure 5.

Blueprint wires the camera and left/right controller world transforms into the ABP each tick—feeding Head/Left/Right Hand inputs—so the skeletal mesh follows the HMD/controllers while UBIKSolver solves the remaining upper body.

Figure 6.

Controller inputs drive sequence poses (idle, index/thumb touch/press, grip variants) that are layered per-bone via scalar weights to compose the final hand pose before forwarding to UBIKSolver.

Figure 6.

Controller inputs drive sequence poses (idle, index/thumb touch/press, grip variants) that are layered per-bone via scalar weights to compose the final hand pose before forwarding to UBIKSolver.

Figure 7.

Quest controller touch/press combinations drive avatar hand poses—Neutral, Index Curl/Full Curl, OK, Hand-Gun, Pointing, Thumbs-Up, and Clench—used as discrete gestures in the evaluator.

Figure 7.

Quest controller touch/press combinations drive avatar hand poses—Neutral, Index Curl/Full Curl, OK, Hand-Gun, Pointing, Thumbs-Up, and Clench—used as discrete gestures in the evaluator.

Figure 8.

Position check by checking if the passed position value is inside the passed interval values.

Figure 8.

Position check by checking if the passed position value is inside the passed interval values.

Figure 9.

The world position of a bone is first subtracted by the world position of the pelvis bone so that the hand bone’s position is relative to the pelvis bone.

Figure 9.

The world position of a bone is first subtracted by the world position of the pelvis bone so that the hand bone’s position is relative to the pelvis bone.

Figure 10.

Combination of hand gesture check, position check, and rotation check to determine if current pose is the ASL pose for “Please”.

Figure 10.

Combination of hand gesture check, position check, and rotation check to determine if current pose is the ASL pose for “Please”.

Figure 11.

A mutex is on while the timer is running, switching the state of pose evaluation to expect the second pose.

Figure 11.

A mutex is on while the timer is running, switching the state of pose evaluation to expect the second pose.

Figure 12.

Classic game mode blueprints. Event-driven graph for classic mode—initialization, input, scoring, actor spawn/cleanup, and state transitions (play/pause/end).

Figure 12.

Classic game mode blueprints. Event-driven graph for classic mode—initialization, input, scoring, actor spawn/cleanup, and state transitions (play/pause/end).

Figure 13.

Timer-controlled subgraph with internal state switches handling round timing, countdowns, win/lose checks, and reset to idle.

Figure 13.

Timer-controlled subgraph with internal state switches handling round timing, countdowns, win/lose checks, and reset to idle.

Figure 14.

Game logic for snapshot mode. The blueprint runs a short countdown, opens a capture window, and evaluates the pose only at timeout—requiring the player to hold the prompted configuration.

Figure 14.

Game logic for snapshot mode. The blueprint runs a short countdown, opens a capture window, and evaluates the pose only at timeout—requiring the player to hold the prompted configuration.

Figure 15.

Viewport of the ASLGameManager. Editor view of the self-contained scene hub showing the MetaHuman NPC, start/stop interactable meshes, capture camera for the “mirror” widget, and the console wall with UI text blocks.

Figure 15.

Viewport of the ASLGameManager. Editor view of the self-contained scene hub showing the MetaHuman NPC, start/stop interactable meshes, capture camera for the “mirror” widget, and the console wall with UI text blocks.

Figure 16.

Main menu that the player can access after starting the game. Compact in-headset widget with three controls: Play (starts the round), Game mode (toggles Classic/Snapshot and shows the current selection), and End Minigame (returns control to the base TUMSphere pawn).

Figure 16.

Main menu that the player can access after starting the game. Compact in-headset widget with three controls: Play (starts the round), Game mode (toggles Classic/Snapshot and shows the current selection), and End Minigame (returns control to the base TUMSphere pawn).

Figure 17.

In-game look while playing. Panels (a–e) show the five supported signs performed in front of the console: (a) Hello (single-hand wave), (b) Thank you (dynamic, two-step mouth-to-out gesture), (c) Help (two-hand configuration with supporting palm), (d) Please (flat hand on chest), and (e) Sorry (circular fist on chest). The on-wall UI provides the prompt and countdown; results are computed from combined hand-gesture and position/rotation thresholds, with feedback (“Miss…/Great!/Perfect!”) displayed after each attempt.

Figure 17.

In-game look while playing. Panels (a–e) show the five supported signs performed in front of the console: (a) Hello (single-hand wave), (b) Thank you (dynamic, two-step mouth-to-out gesture), (c) Help (two-hand configuration with supporting palm), (d) Please (flat hand on chest), and (e) Sorry (circular fist on chest). The on-wall UI provides the prompt and countdown; results are computed from combined hand-gesture and position/rotation thresholds, with feedback (“Miss…/Great!/Perfect!”) displayed after each attempt.

Figure 18.

Participant performance across five poses. Stacked bars (N = 10) show the count of participants rated Consistent (blue), Partial (orange), or None (green) for each sign.

Figure 18.

Participant performance across five poses. Stacked bars (N = 10) show the count of participants rated Consistent (blue), Partial (orange), or None (green) for each sign.

Table 1.

Summary of key findings and limitations of Virtual Reality in sign language learning [

31].

Table 1.

Summary of key findings and limitations of Virtual Reality in sign language learning [

31].

| Category | Principal Findings | Limitations |

|---|

| Gesture recognition and feedback mechanisms | Advanced gesture recognition using CNNs, LSTMs, HMMs, and 3D CNNs enables real-time sign evaluation with high accuracy. Visual feedback facilitates learning, and Unity and Oculus are commonly used platforms for this purpose. | Hardware dependency, limited gesture datasets, no haptic feedback, challenges with dynamic gestures, and low facial expression tracking accuracy. |

| Interactive VR environments for practice | Gamified VR with contextual scenarios enables immersive practice; avatar-based multiplayer design fosters realistic interactions and engagement. | It is primarily used for individual use, has limited multiplayer integration, and lacks culturally adapted communication models. |

| Immersive learning through gamification | Gamification improves motivation, engagement, and retention; gesture-triggered puzzles and animations reinforce sign-memory links. | Some gamified elements are superficial; they may not address learner autonomy, confusion in 3D environments, or meet the needs of novice users. |

| Personalized learning and adaptive systems | Some systems allow manual replay, camera control, and non-linear navigation; conceptual frameworks for adaptive learning exist. | Lack of AI-based adaptation, minimal real-time performance tracking, and no intelligent feedback loops. |

| Accessibility and inclusivity | VR avatars and visual feedback support DHH learners; they report improved motivation and support for proposed multilingual environments. | High hardware cost, limited support for interpreter avatars, absence of standardized academic signs, and limited support for users with multiple disabilities. |

Table 2.

Functional and non-functional requirements for the ASL-learning accessibility module.

Table 2.

Functional and non-functional requirements for the ASL-learning accessibility module.

| Requirement | Description |

|---|

| FR | Maps the player’s real-world body gestures to in-game avatar animations. |

| FR | Recognizes the ASL word expressed via the avatar’s animations. |

| FR | Evaluates pose correctness and provides feedback and score. |

| FR | Shows visual demonstrations of prompted poses to support learning. |

| NFR | Built with Unreal Engine (UE). |

| NFR | Runs on Meta Quest 3 headset. |

| NFR | Uses MetaHuman for both the player character and NPC. |

| NFR | Provides a robust, consistent ASL pose-evaluation system. |

| NFR | Offers an intuitive design for players with no ASL experience. |

| NFR | Delivers an engaging, immersive ASL learning flow. |

Table 3.

Objective performance across five ASL poses for : Success % (Wilson 95% CIs), TTFS (mean ± SD), Attempts (mean ± SD), and Hold stability.

Table 3.

Objective performance across five ASL poses for : Success % (Wilson 95% CIs), TTFS (mean ± SD), Attempts (mean ± SD), and Hold stability.

| Pose | Success % (95% CI) | TTFS (s) Mean ± SD | Attempts Mean ± SD | Hold Stability |

|---|

| Hello | 100.00% (72.25%, 100.00%) | 1.86 ± 0.39 | 1.94 ± 0.63 | 0.88 |

| Thank you | 0.00% (0.00%, 27.75%) | – | 1.96 ± 0.62 | 0.89 |

| Sorry | 100.00% (72.25%, 100.00%) | 2.83 ± 0.46 | 2.10 ± 0.53 | 0.82 |

| Please | 100.00% (72.25%, 100.00%) | 2.19 ± 0.38 | 2.06 ± 0.67 | 0.87 |

| Help | 0.00% (0.00%, 27.75%) | – | 1.85 ± 0.50 | 0.90 |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).