Abstract

Though it is well documented that antidepressants are associated with an increased risk of falls in older adults at the drug class level, the comparative risk between individual antidepressants for fall injury in older adults with depression is unknown. Currently, clinicians are making decisions at the drug class level without consideration of the potential that there could be safer choices within classes. We compared the risk of fall injury among initiators of bupropion, duloxetine, fluoxetine, paroxetine, and venlafaxine to those of (es)citalopram and, separately, sertraline. We performed a retrospective cohort study using the MarketScan® Medicare Supplemental claims from 2007 to 2019. Individuals had incident depression (washout in previous continually enrolled year) with a first antidepressant claim up to three months after depression diagnosis. Individuals were followed for the first three months of antidepressant use until the first occurrence of fall injury, change/discontinuation of antidepressant, discontinued insurance coverage, or end of study. Propensity score inverse probability of treatment-weighted Cox proportional hazards models estimated hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals for each antidepressant comparison and fall injury. We identified 114,505 individuals (mean age 76.6 years, 68% female, 97% without prior fall). A higher risk of fall injury was associated with initiating bupropion (HR 1.20 to 1.61), duloxetine (HR 1.27 to 1.36), paroxetine (HR 1.14 to 1.22), and venlafaxine (HR 1.22 to 1.34) when compared to (es)citalopram or sertraline. New use of duloxetine, bupropion, paroxetine, and venlafaxine was associated with a higher risk of fall injury compared to (es)citalopram and sertraline.

1. Introduction

Depression is common in later life, with approximately 15% of community-dwelling older adults reporting clinically significant depressive symptoms [1]. Depression is an independent risk factor for falls [2]. Each year, an average of 170 fall injuries are reported per 1000 adults aged 65 years and older, translating to 8.4 million fall injuries [1]. Depression and falls both contribute to impairing functioning, lowering quality of life, and increasing mortality [2,3,4].

One in five older adults in the community are prescribed an antidepressant, higher than any other age group [5]. Antidepressants are prescribed based on patient preferences and the drug’s safety profile, among other factors [6,7]. These medications include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (i.e., citalopram, escitalopram, fluoxetine, paroxetine, and sertraline), serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) (i.e., desvenlafaxine, duloxetine, venlafaxine), and bupropion, a norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake inhibitor, along with some less frequently used drug classes such as monoamine oxidase inhibitors. Antidepressant-related adverse events, specifically in older adults, include impaired alertness, gait, balance, and blood pressure regulation, thereby increasing the risk of falls [8]. The association between antidepressants and falls or fall injuries has been reported in previous observational studies, and the American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medications in Older Adults recommend avoiding prescriptions for antidepressants in older adults with a history of falls or fractures [9,10,11]. Therefore, one modifiable risk factor for fall injuries is the reduction in medications acting on the central nervous system, such as antidepressants [12]. This scenario presents a paradox for clinicians considering prescribing an antidepressant for an older adult with depressive symptoms who is also at risk for a fall.

However, while drug class level risk has been established, little is known about how fall injury risk differs between individual antidepressants. The risk may vary due to differences in pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic effects [12]. As a result, clinicians are making decisions “in the dark” at the individual drug choice level. This lack of knowledge is due to the fact that not only do randomized trials of antidepressants rarely collect fall injury outcomes, but few studies compare antidepressants to one another [13,14]. Thus, observational analysis is the primary approach to learning about fall injury risk. However, these studies face a high risk of bias from confounding by indication when comparing antidepressant users versus non-users.

Previous studies have shown that the risk of falls and fall-related injuries are highest during the first weeks of treatment. In fact, a case–control and case-series analysis of a large UK primary care database found that the risk of falls was increased almost twofold in people prescribed an antidepressant, and that this increased risk occurred in the first few weeks after the first prescription among all antidepressant classes [15]. In addition, a systematic review of over 200 studies of psychotropics concluded that initiation of antidepressants and benzodiazepines appear to increase fall-risk [16]. It is hypothesized that this pronounced risk may be due to the presence of both antidepressant- and depression-associated fall risk in this timeframe. Furthermore, it is known that adverse events, such as orthostatic hypotension and hyponatremia, are strongest upon antidepressant initiation or dose increase [17].

Taken together, this study compared the risk of fall injury among initiators of antidepressants (bupropion, fluoxetine, paroxetine, venlafaxine, and duloxetine) in separate pairwise comparisons to citalopram or escitalopram ((es)citalopram) and (again in separate pairwise comparisons) to sertraline during the acute treatment phase (i.e., the first three months of treatment), overall and within subgroups by age, sex, and previous fall injury. Escitalopram and sertraline were selected as separate referent exposure groups since they were the most commonly prescribed antidepressants.

2. Results

2.1. Study Sample

A total of 114,505 individuals were included in the analysis. Descriptive statistics demonstrated uniformity across all seven antidepressant groups (Table 1). The mean age of all individuals was 76.6 (standard deviation (SD), 7.87), 67.6% were female, the mean CCI was 2.64 (SD, 2.63), and 97.3% did not have a previous fall (Table 1). The distribution of antidepressants among the sample was as follows: 34.2% on citalopram or escitalopram, 21.8% on sertraline, 10.4% on duloxetine, 10.0% on fluoxetine, 8.5% on bupropion, 8.1% on venlafaxine, and 6.9% on paroxetine (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics at cohort entry overall and by antidepressant.

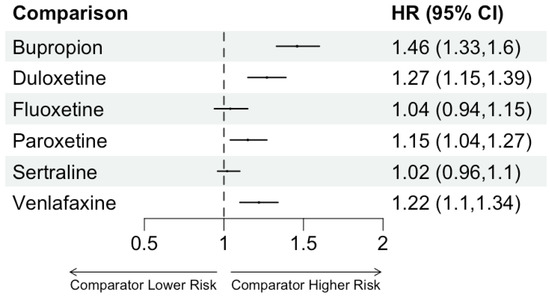

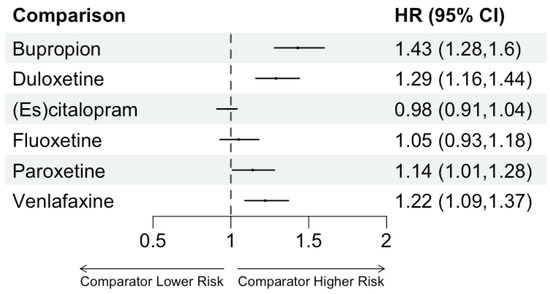

2.2. Primary Analysis

In the primary analysis, a statistically significantly higher risk of fall injury was associated with initiating bupropion (HR 1.43 to 1.46), duloxetine (HR 1.27 to 1.29), paroxetine (HR 1.14 to 1.15), and venlafaxine (HR 1.22) when compared to (es)citalopram or sertraline (Figure 1 and Figure 2; Table S1) in the acute phase of treatment.

Figure 1.

Forest plot of hazard ratios for the risk of fall injury compared to (es)citalopram. Note: All comparisons estimated using propensity scores of an individual’s likelihood to be prescribed a specific antidepressant, using multinomial logistic regression with age, sex, health plan type, region, year of diagnosis, CCI, and number of prior falls as the independent variables.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of hazard ratios for the risk of fall injury compared to sertraline. Note: All comparisons estimated using propensity scores of an individual’s likelihood to be prescribed a specific antidepressant, using multinomial logistic regression with age, sex, health plan type, region, year of diagnosis, CCI, and number of prior falls as the independent variables.

2.3. Secondary Analyses

Results were consistent for subgroups defined by age, sex, and injurious fall history.

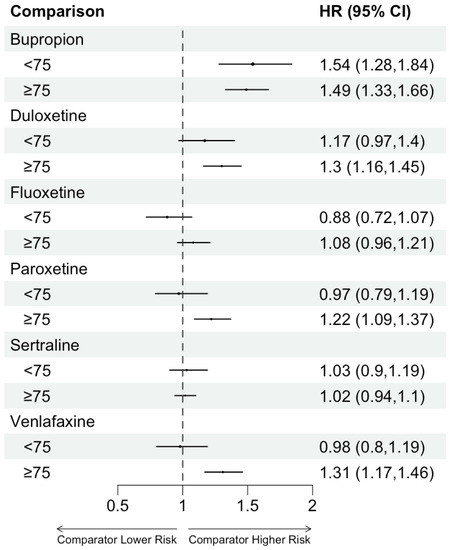

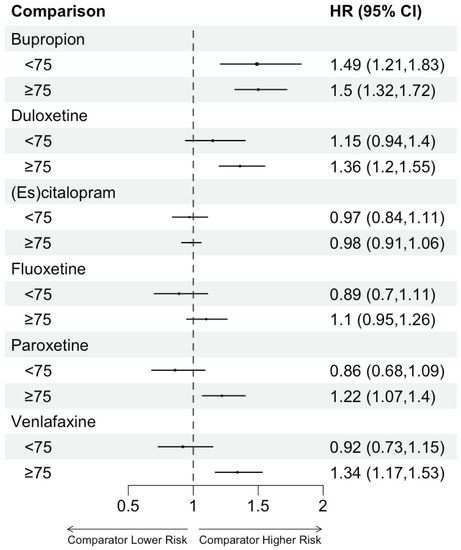

2.3.1. Age

There was a statistically significantly higher risk of fall injury for bupropion, regardless of age group (HR: 1.49 to 1.54 vs. (es)citalopram; 1.49 to 1.50 vs. sertraline). For individuals with age ≥75 years, there was a statistically significantly higher risk of fall injury for duloxetine (HR: 1.30 vs. (es)citalopram; 1.36 vs. sertraline), paroxetine (HR: 1.22 vs. (es)citalopram; 1.22 vs. sertraline), and venlafaxine (HR: 1.31 vs. (es)citalopram; 1.34 vs. sertraline) (Figure 3 and Figure 4; Tables S2 and S3).

Figure 3.

Forest plot of hazard ratios for subgroup by age (<75 and ≥75) for the risk of fall injury compared to (es)citalopram. Note: All comparisons estimated using propensity scores of an individual’s likelihood to be prescribed a specific antidepressant, using multinomial logistic regression with age, sex, health plan type, region, year of diagnosis, CCI, and number of prior falls as the independent variables.

Figure 4.

Forest plot of hazard ratios for subgroup by age (<75 and ≥75) for the risk of fall injury compared to sertraline. Note: All comparisons estimated using propensity scores of an individual’s likelihood to be prescribed a specific antidepressant, using multinomial logistic regression with age, sex, health plan type, region, year of diagnosis, CCI, and number of prior falls as the independent variables.

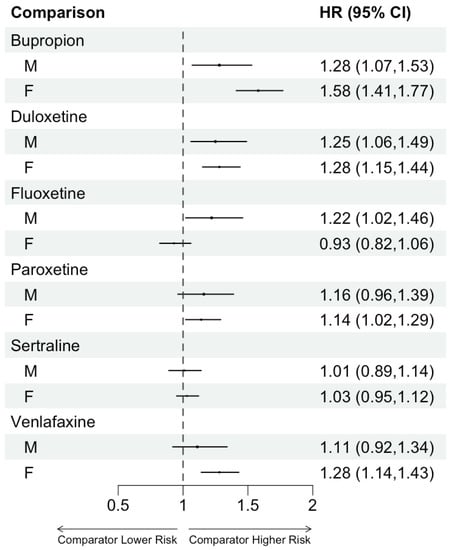

2.3.2. Sex

Compared to (es)citalopram, regardless of sex, there was a statistically significantly higher risk of fall injury for bupropion, with the risk being higher in females (HR: 1.28 vs. 1.58 for males vs. females, respectively). Duloxetine was also associated with a higher risk of fall injury in both sexes (HR: 1.25 to 1.28). Among males, fluoxetine was associated with a higher risk of fall injury (HR: 1.22), but this risk was not present in females. Females who took paroxetine (HR: 1.14) and venlafaxine (HR: 1.28) were at a higher risk of fall injury, but we did not observe significant associations between these drugs and fall injury in males (Figure 5; Table S4).

Figure 5.

Forest plot of hazard ratios for subgroup by sex for the risk of fall injury compared to (es)citalopram. Note: All comparisons estimated using propensity scores of an individual’s likelihood to be prescribed a specific antidepressant, using multinomial logistic regression with age, sex, health plan type, region, year of diagnosis, CCI, and number of prior falls as the independent variables.

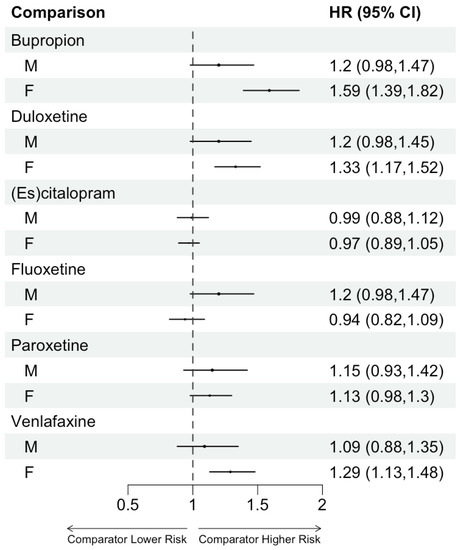

Compared to sertraline, there was no difference in risk of fall injury among antidepressants in males. However, females who took bupropion (HR: 1.59), duloxetine (HR: 1.33), and venlafaxine (HR: 1.29) had a statistically significantly increased risk of fall injury (Figure 6; Table S5).

Figure 6.

Forest plot of hazard ratios for subgroup by sex for the risk of fall injury compared to sertraline. Note: All comparisons estimated using propensity scores of an individual’s likelihood to be prescribed a specific antidepressant, using multinomial logistic regression with age, sex, health plan type, region, year of diagnosis, CCI, and number of prior falls as the independent variables.

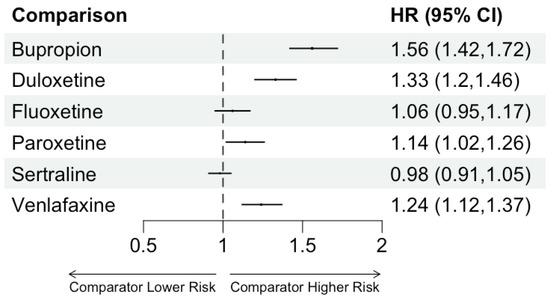

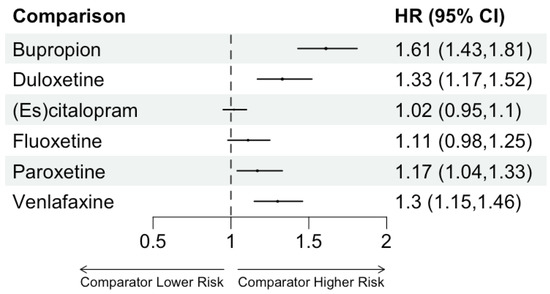

2.3.3. No Prior Falls

In individuals with no prior falls, the risk of fall injury is higher among those who took bupropion (HR: 1.56 vs. (es)citalopram; 1.61 vs. sertraline), duloxetine (HR: 1.33 vs. (es)citalopram; 1.33 vs. sertraline), paroxetine (HR: 1.14 vs. (es)citalopram; 1.17 vs. sertraline), and venlafaxine (HR: 1.24 vs. (es)citalopram; 1.30 vs. sertraline) (Figure 7 and Figure 8; Table S6).

Figure 7.

Forest plot of hazard ratios for subgroup of no prior fall for the risk of fall injury compared to (es)citalopram. Note: All comparisons estimated using propensity scores of an individual’s likelihood to be prescribed a specific antidepressant, using multinomial logistic regression with age, sex, health plan type, region, year of diagnosis, CCI, and number of prior falls as the independent variables.

Figure 8.

Forest plot of hazard ratios for subgroup of no prior fall for the risk of fall injury compared to sertraline. Note: All comparisons estimated using propensity scores of an individual’s likelihood to be prescribed a specific antidepressant, using multinomial logistic regression with age, sex, health plan type, region, year of diagnosis, CCI, and number of prior falls as the independent variables.

3. Discussion

In this retrospective cohort comparative safety study of individual antidepressants, bupropion, duloxetine, paroxetine, and venlafaxine were most frequently associated with a higher risk of fall injury in older adults with depression (14% to 61% higher risk) as compared to (es)citalopram and sertraline. Bupropion had the highest point estimate of risk overall and across all subgroups. Fluoxetine had a similar risk of fall injury when compared to (es)citalopram or sertraline. Sertraline and (es)citalopram did not differ in their risk of fall injury when compared to each other. These findings were consistent overall and across all subgroups.

We found evidence that individuals aged ≥75 years had a greater risk of fall injury when prescribed duloxetine, paroxetine, and venlafaxine compared to either (es)citalopram or sertraline. Moreover, females who filled prescriptions for venlafaxine were at higher risk of fall injury, but we did not observe this association in males. For individuals with no prior falls, results were similar to the primary analysis.

It is important to interpret these results in the context of the published literature. Unfortunately, there is limited literature on the risk of fall-related injury in older adults who take bupropion, adding to the unique contribution of our study results to the literature. We hypothesize that our findings may be related to the association of bupropion with insomnia, which itself increases fall risk by impaired reaction capability [17,18]. In terms of efficacy, a meta-analysis of seven randomized controlled trials demonstrated that bupropion produced similar depression remission rates when compared to SSRIs with a median time to relapse of 44 weeks [19]. If efficacy is in fact similar between bupropion and SSRIs, future research is needed to further elucidate the potential causal mechanisms between bupropion and falls in older adults to better inform clinical decisions.

The SSRIs are considered to be relatively safe antidepressants. For example, a systematic review of adverse events of pharmacological treatments of major depression in older adults found that SSRIs led to a statistically similar frequency of overall adverse events (e.g., hospitalization, mortality, and falls) vs. placebo [13]. This is consistent with our findings, except for paroxetine, which was consistently associated with a higher risk of fall injury when compared to other SSRIs, (es)citalopram and sertraline. This finding is expected as paroxetine is defined as a high-risk medication according to the US Pharmacy Quality Alliance. Furthermore, a previous South Korean study found that, among SSRIs, paroxetine had the highest risk of fall-related injuries [20]. These results are likely due to paroxetine’s strong anticholinergic and antihistaminergic activity linked with more sedation compared to other SSRIs [21,22]. Paroxetine also has the highest incidence of SSRI-associated hyponatremia among SSRIs [17,23].

Among serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) (i.e., duloxetine and venlafaxine), results are consistent compared to (es)citalopram and sertraline. An AHRQ review based on a systematic review of 19 RCTs and two observational studies, and a meta-analysis of comparative antidepressant safety (including falls and fractures) found that SNRIs are associated with a greater number of overall adverse events, and that duloxetine and venlafaxine lead to more falls compared to placebo. However, this same study concluded no difference in adverse events between venlafaxine and SSRIs [13]. Furthermore, none of the RCTs were powered or designed to capture adverse events and most studied low doses of antidepressants, and observational data were limited by residual confounding. Our finding that duloxetine was associated with an increased risk of injurious falls is also in line with clinical trials that have shown its association with adverse events such as dizziness and insomnia, which can increase the risk of falling [24,25,26].

Differences in fall-related injury by sex have also previously been published. In a study using the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System All Injury Program, Stevens et al. quantified gender differences for non-fatal unintentional fall-related injuries among US adults aged 65 years and older treated in hospital emergency departments [27]. They concluded that, among older adults, these injuries disproportionately affected women; they sustained fall-related injuries at rates 40–60% higher than those of men of comparable age, and their hospitalization rates for fall injuries were about 81% higher than men’s, suggesting that women sustained more severe injuries [27]. These differences in fall risk are thought to be due to physiological changes in post-menopausal women, such as poorer muscle strength, lower body mass index, and higher likelihood of having rheumatic diseases [28,29]. Our study uniquely provides differences in fall-related injury comparing individual antidepressants by sex. Most notably, we found that females, unlike males, who took bupropion, duloxetine, and venlafaxine had a statistically significantly increased risk of fall injury compared to sertraline. Results also showed that females who took paroxetine and venlafaxine were at a higher risk of fall injury compared to those taking (es)citalopram, but this was not true for males. In contrast, males taking fluoxetine had a higher risk of fall injury when compared to (es)citalopram, but this was not present in females.

3.1. Strengths

The robust observational study methodology that we used (i.e., inverse probability of treatment weighting using propensity scores) allowed us to compare individuals who were very similar to each other in terms of demographic and clinical characteristics. Furthermore, we controlled for the use of concomitant medications that may have confounded the association between antidepressants and fall-related injury. While we were not able to randomize our sample, we accounted for observed confounders in a robust way, primarily through the use of propensity scores. At the same time, it is important to note that it is unlikely that any future randomized clinical trial will be conducted comparing commonly prescribed individual antidepressants and the outcome of injurious falls. The clinical significance of the magnitude of the observed hazard ratios must be interpreted with the potential significance of a fall injury for an older adult, which can be debilitating.

3.2. Limitations

All results must be interpreted in light of the study’s limitations. First, some antidepressants examined have indications beyond depression (e.g., bupropion can be prescribed for smoking cessation; duloxetine for postherpetic neuralgia), introducing the possibility for confounding by indication. However, we attempted to minimize this bias by requiring people to have had a depression diagnosis no greater than 3 months prior to initiating the antidepressant. Second, we were unable to measure depression severity, which could lead to potential unmeasured confounding; however, this is unlikely to introduce differential bias [9]. Third, an important limitation of the MarketScan® Medicare Supplemental data is that the claims are for Medicare-eligible retirees with employer-sponsored Medicare Supplemental plans. Therefore, the results obtained are not generalizable to all Medicare patients or people without insurance. Fourth, we did not examine the dose–response associations between antidepressants and fall-injury outcome. This requires future research and would be an important next step. Finally, we did not adjust for multiple comparisons. Rather, consistent with recommendations [30,31,32,33], we provided comprehensive information on the study design, methods, and statistical analyses and reported point estimates and confidence intervals so that readers can interpret the findings in the context of published reports on this topic. This study is also intended to generate further hypotheses to ultimately facilitate clinical decision making.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Data Source

We used the MarketScan® Medicare Supplemental claims data between 2007 and 2019 (https://www.merative.com/documents/brief/marketscan-explainer-general; accessed on 19 June 2023). The MarketScan® databases include enrollment tables that track enrollee demographics and monthly insurance eligibility, linked to claims for medical services (inpatient, outpatient, home health, hospice, skilled nursing, and durable medical equipment), as well as outpatient pharmacy claims.

4.2. Sample Selection

Individuals were selected for inclusion into the study if they were aged 65 years or older and had an incident depression diagnosis code associated with an outpatient or inpatient visit as characterized by the International Classification of Disease codes 9th (ICD-9) and 10th (ICD-10) versions (ICD-9: 296.2, 296.20, 296.21, 296.22, 296.23, 296.24, 296.25, 296.26, 296.3, 296.30, 296.31, 296.32, 296.33, 296.34, 296.35, 296.36; ICD-10: F33, F330, F331, F332, F333, F334, F3340, F3341, F3342, F335, F336, F337, F338, F339), followed by an outpatient prescription claim within 3 months for either bupropion, escitalopram, citalopram, duloxetine, fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, or venlafaxine, and 12 months of continuous enrollment prior to the date the antidepressant was filled (defined as the index date). Individuals were excluded if prescriptions for more than one antidepressant were filled on the same day, or if there was an antidepressant prescription claim in the 12 months prior to the index or a diagnosis of depression prior to the incident depression diagnosis claim. A washout period was applied to ensure individuals had no diagnosis of depression in the 12 months prior to their incident depression diagnosis claim.

4.3. Study Design

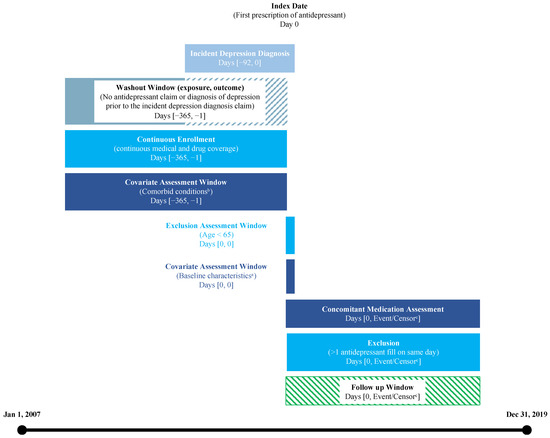

Subjects were selected based on their incident depression diagnosis (i.e., newly diagnosed depression). The index date for the study was defined as the date of service for the first antidepressant claim within three months following the incident depression claim. Both the follow-up time and 12 months of continuous enrollment were based on the index date (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Study Design. (a) Baseline characteristics included: age, sex, census region, insurance plan type, Charlson comorbidity index. (b) Comorbid conditions: alcohol abuse/dependence, opioid or non-opioid drug abuse/dependence, syncope, vertigo/dizziness, dementia/Alzheimer’s disease or mild cognitive impairment, Parkinson’s disease, diabetes, urinary incontinence, anxiety disorder, epilepsy, head trauma, hypotension, stroke or cerebrovascular accident, vision disorders, congestive heart failure, ischemic heart disease. (c) Enrollees changing (e.g., second antidepressant added) or discontinuing (gap in prescription fill >90 days) antidepressant treatment, not experiencing an outcome, or disenrollment from MarketScan. Outcome ascertainment ended after one year of follow-up after index.

4.4. Independent Variable (Exposure)

The exposures in this study were individual antidepressants, classified by generic ingredient: bupropion, escitalopram, citalopram, duloxetine, fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, and venlafaxine. These drugs were identified by therapeutic class, generic ID, and generic name in both the MarketScan® drug data files and the MarketScan Redbook® (https://www.merative.com/documents/brief/marketscan-explainer-general; accessed on 19 June 2023). Citalopram and escitalopram were combined due to their chemical formulation (i.e., they are mirror images of each other, or enantiomers). Individuals prescribed (es)citalopram or sertraline were selected as separate referent exposure groups since they were the most commonly prescribed antidepressants.

4.5. Outcome

Fall injury, the outcome of interest, was based on emergency department and inpatient claims as defined by ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes, a method previously published by Tinetti et al. [34]. The ICD-9 E-codes and ICD-10 codes of interest were events with a fall-related code (E8800-E8889; W00-W19 and V00141) along with a code for the following fractures: skull, facial, cervical, clavicle, thorax, humeral, forearm, pelvic, hip, fibula, tibia, or ankle (80000-80619, 8070-8072, 8080-8089, 81000-81419, 8180-8251, 8270-8291; S00-S09, S10-S19, S20-S29, S30-S39, S40-S49, S50-S59, S60-S69, S90-S99), brain injury (85200-85239; S06), or dislocation of the hip, knee, shoulder, or jaw (8300-83219, 83500-83513, 83630-83660; S70-S79, S80-S89).

4.6. Covariates

Covariates were measured in the year prior to the index date. The covariates included in the model were age at depression diagnosis, sex, health plan type, region, year of depression diagnosis, Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) at cohort entry, prior fall(s), and medical conditions (defined as present if ≥1 diagnosis code for the condition in any medical claims in the 12 months prior to index anti-depressant fill date; alcohol abuse/dependence, opioid or non-opioid drug abuse/dependence, syncope, vertigo/dizziness, dementia/Alzheimer’s disease or mild cognitive impairment, Parkinson’s disease, diabetes, urinary incontinence, anxiety disorder, epilepsy, head trauma, hypotension, stroke or cerebrovascular accident, vision disorders, congestive heart failure, ischemic heart disease). The use of concomitant medications alongside antidepressants was included by therapeutic class as time-dependent covariates (first-generation antihistamines (excluding over-the-counter products), muscle relaxants, diabetes medications, dementia medications, Parkinson’s medications, antipsychotics, sedative hypnotics and benzodiazepines, opioids, stimulants).

4.7. Analysis

All analyses evaluated comparative risk to (es)citalopram and sertraline, separately, during the acute (<85 days) treatment phase as defined by the NCQA HEDIS (National Committee for Quality Assurance Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set) measure for Antidepressant Medication Management [35].

The primary analysis compared all individuals with new use of the specified antidepressants adjusting for demographic and clinical characteristics at cohort entry. The secondary analyses assessed fall injury risk in subpopulations of interest: age (<75 years vs. ≥75), sex (female versus male), and whether the patient had a prior fall (unlike the outcome, we included non-injurious falls because we hypothesized that a history of these falls would increase the individual’s risk of a subsequent injurious fall).

To reduce confounding, we used the inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) using the propensity score [36,37]. IPTW was defined as the inverse probability of an individual’s likelihood to be prescribed a specific antidepressant, using multinomial logistic regression with age, sex, health plan type, region, year of diagnosis, CCI, and number of prior falls as the independent variables. Weighting created a sample in which treatment assignment was independent of the measured covariates and, thus, minimized confounding in the comparisons of antidepressant-specific fall injury risk [2,38].

We used time-to-event IPTW-weighted Cox proportional hazards models to estimate the adjusted hazard ratios and 95% CIs for the association between each antidepressant and the risk of the first fall-related injury. Censoring occurred from any of the following: enrollees changing (e.g., second antidepressant added) or discontinuing (gap in prescription fill >90 days) antidepressant treatment, not experiencing an outcome, or disenrollment from MarketScan® [39].

The statistical analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

5. Conclusions

In this large observational cohort study of older adults with depression in the U.S., initiation of bupropion, duloxetine, paroxetine, and venlafaxine, as compared to (es)citalopram and sertraline, increased the risk of fall-related injury in the first three months of treatment, especially among older and female individuals. Healthcare providers should routinely screen for and monitor fall risk in older adults starting antidepressants, especially in the acute phase of treatment.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/pharma2030018/s1, Table S1: Results for the full sample; Table S2: Results for subgroup by age (<75 and ≥75) for the risk of fall injury compared to (es)citalopram; Table S3: Results for subgroup by age (<75 and ≥75) for the risk of fall injury compared to sertraline; Table S4: Results for subgroup by sex for the risk of fall injury compared to (es)citalopram; Table S5. Results for subgroup by sex for the risk of fall injury compared to sertraline; Table S6. Results for subgroup without a prior fall for the risk of fall injury compared to (es)citalopram and sertraline.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.A.M. and R.N.H.; formal analysis, A.T. and L.S.G.; funding acquisition, A.T. and R.N.H.; methodology, A.T., Z.A.M. and R.N.H.; project administration, A.T.; supervision, Z.A.M. and R.N.H.; validation, L.S.G.; writing—original draft, A.T.; writing—review and editing, A.T., L.S.G., Z.A.M. and R.N.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported, in part, by the Harborview Injury Prevention and Research Center’s Frederick P. Rivara Endowed Injury Research Grant.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived because this study was exempt from review by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study are proprietary, not publicly available, and subject to Third-Party Data Restrictions. They were used under a license between Merative and the University of Washington. Data can be accessed through Merative (previously under IBM Watson, Truven, and Thompson Reuters) under their license and data use agreement. URL: https://www.merative.com/real-world-evidence (accessed on 19 June 2023).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Beekman, A.T.; Deeg, D.J.; van Tilburg, T.; Smit, J.H.; Hooijer, C.; van Tilburg, W. Major and minor depression in later life: A study of prevalence and risk factors. J. Affect. Disord. 1995, 36, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stuck, A.E.; Walthert, J.M.; Nikolaus, T.; Büla, C.J.; Hohmann, C.; Beck, J.C. Risk factors for functional status decline in community-living elderly people: A systematic literature review. Soc. Sci. Med. 1999, 48, 445–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorina, T.; Hoyert, D.; Lentzner, H.; Gounding, M. Trends in causes of death among older persons in the United States. Aging Trends 2005, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Peel, N.M. Epidemiology of falls in older age. Can. J. Aging 2011, 30, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, L.A.; Brody, D.J.; Gu, Q. Antidepressant Use among Persons Aged 12 and Over: United States, 2011–2014. NCHS Data Brief, No. 283; National Center for Health Statistics: Hyattsville, MD, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kovich, H.; Dejong, A. Common questions about the pharmacologic management of depression in adults. Am. Fam. Physician 2015, 92, 94–100. [Google Scholar]

- Dipiro, J.; Gary, C.; Poset, L.; Haines, S.; Nolin, T.; Ellingrod, V. Pharmacotherapy: A Pathophysiologic Approach, 11th ed.; McGraw-Hill: Columbus, OH, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, J.G. Drugs and falls in later life. Lancet 2003, 361, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coupland, C.; Dhiman, P.; Morriss, R.; Arthur, A.; Barton, G.; Hippisley-Cox, J. Antidepressant use and risk of adverse outcomes in older people: Population based cohort study. BMJ 2011, 343, d4551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamblyn, R.; Bates, D.; Buckeridge, D.; Dixon, W.; Girard, N.; Haas, J.; Habib, B.; Iqbal, U.; Li, J.; Sheppard, T. Multinational investigation of fracture risk with antidepressant use by class, drug, and indication. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2020, 68, 1494–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, S.L.; Marcum, Z.A.; Dublin, S.; Walker, R.; Golchin, N.; Rosenberg, D.E.; Bowles, E.J.; Crane, P.; Larson, E.B. Association between medications acting on the central nervous system and fall-related injuries in community-dwelling older adults: A new user cohort study. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 2020, 75, 1003–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexopoulos, G.S. Depression in the elderly. Lancet 2005, 365, 1961–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobieraj, D.M.; Martinez, B.K.; Hernandez, A.V.; Coleman, C.I.; Ross, J.S.; Berg, K.M.; Steffens, D.C.; Baker, W.L. Adverse effects of pharmacologic treatments of major depression in older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2019, 67, 1571–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, Y.K.; Kakara, R.; Marcum, Z.A. A comparative analysis of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and fall risk in older adults. J. Am. Ger. Soc. 2022, 70, 1450–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gribbin, J.; Hubbard, R.; Gladman, J.; Smith, C.; Lewis, S. Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor antidepressants and the risk of falls in older people: Case-control and case-series analysis of a large UK primary care database. Drugs Aging 2011, 28, 895–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seppala, L.J.; Wermelink, A.M.; de Vries, M.; Ploegmakers, K.J.; van de Glind, E.M.; Daams, J.G.; Thaler, H. Fall-risk-increasing drugs: A systematic review and meta-analysis: II. Psychotropics. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2018, 19, 371.e11–371.e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Poelgeest, E.P.; Pronk, A.C.; Rhebergen, D.; van der Velde, N. Depression, antidepressants and fall risk: Therapeutic dilemmas—A clinical review. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2021, 12, 585–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, S.M.; Pradko, J.F.; Haight, B.R.; Modell, J.G.; Rockett, C.B.; Learned-Coughlin, S. A review of the neuropharmacology of bupropion, a dual norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake inhibitor. Prim. Care Companion J. Clin. Psychiatry 2004, 6, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanMeter, S.; Harriett, A.E.; Wang, Y. Remission rates following antidepressant therapy with bupropion or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: A meta-analysis of original data from 7 randomized controlled trials. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2005, 66, 974–981. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, Y.S.; Suh, D.; Choi, H.S.; Park, H.D.; Jung, S.Y.; Suh, D.C. Risk of fall-related injuries associated with antidepressant use in elderly patients: A nationwide matched cohort study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilal-Dandan, R.; Brunton, L. Goodman and Gilman Manual of Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 2; McGraw Hill Professional: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2013; pp. 852–854. [Google Scholar]

- VandenBerg, A.M. Depressive Disorders. In DiPiro’s Pharmacotherapy: A Pathophysiologic Approach, 12th ed.; DiPiro, J.T., Yee, G.C., Haines, S.T., Nolin, T.D., Ellingrod, V.L., Posey, L., Eds.; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2023; Available online: https://accesspharmacy-mhmedical-com.offcampus.lib.washington.edu/content.aspx?bookid=3097§ionid=268013768 (accessed on 18 June 2023).

- Jacob, S.; Spinler, S.A. Hyponatremia associated with selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors in older adults. Ann. Pharm. 2006, 40, 1618–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, J.C.; Oakes, T.M.; Liu, P.; Ahl, J.; Bangs, M.E.; Raskin, J.; Perahia, D.G.; Robinson, M.J. Assessment of falls in older patients treated with duloxetine: A secondary analysis of a 24-week randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Prim. Care Companion CNS Disord. 2013, 15, 26662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Nikhil, N.; Prakash, M. Duloxetine: Review of its pharmacology, and therapeutic use in depression and other psychiatric disorders. Ann. Clin. Psychiatry 2007, 19, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shelton, R.C. Serotonin and Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors. In Antidepressants. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology; Macaluso, M., Preskorn, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, J.A.; Sogolow, E.D. Gender differences for non-fatal unintentional fall related injuries among older adults. Inj. Prev. 2005, 11, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geusens, P.; Autier, P.; Boonen, S.; Vanhoof, J.; Declerck, K.; Raus, J. The relationship among history of falls, osteoporosis, and fractures in postmenopausal women. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2002, 83, 903–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harmon, K.J.; Hakenewerth, A.M.; Waller, A.E.; Ising, A.; Tintinalli, J.E. Begin risk assessment for falls in women at 45, not 65. Inj. Prev. 2019, 25, 184–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothman, K.J. No adjustments are needed for multiple comparisons. Epidemiology 1990, 1, 43–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perneger, T.V. What’s wrong with Bonferroni adjustments. BMJ 1998, 316, 1236–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feise, R.J. Do multiple outcome measures require p-value adjustment? BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2002, 2, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Althouse, A.D. Adjust for Multiple Comparisons? It’s Not That Simple. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2016, 101, 1644–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinetti, M.E.; Han, L.; Lee, D.S.; McAvay, G.J.; Peduzzi, P.; Gross, C.P.; Zhou, B.; Lin, H. Antihypertensive medications and serious fall injuries in a nationally representative sample of older adults. JAMA Intern. Med. 2014, 174, 588–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvelde, T.; McVeigh, C.; Toson, B.; Greenaway, M.; Lord, S.R.; Delbaere, K.; Close, J.C. Depressive symptomatology as a risk factor for falls in older people: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2013, 61, 694–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreland, B.; Kakara, R.; Henry, A. Trends in nonfatal falls and fall-related injuries among adults aged ≥65 years—United States, 2012–2018. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 875–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartholt, K.A.; Lee, R.; Burns, E.R.; van Beeck, E.F. Mortality from falls among US adults aged 75 years or older, 2000–2016. JAMA 2019, 321, 2131–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens, J.A.; Burns, E.R. A CDC Compendium of Effective Fall Interventions: What Works for Community-Dwelling Older Adults, 3rd ed.; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Callahan, C.M.; Hui, S.L.; Nienaber, N.A.; Musick, B.S.; Tierney, W.M. Longitudinal study of depression and health services use among elderly primary care patients. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1994, 42, 833–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).