Lateral Patellar Compression Syndrome: Surgical Techniques and Treatment

Abstract

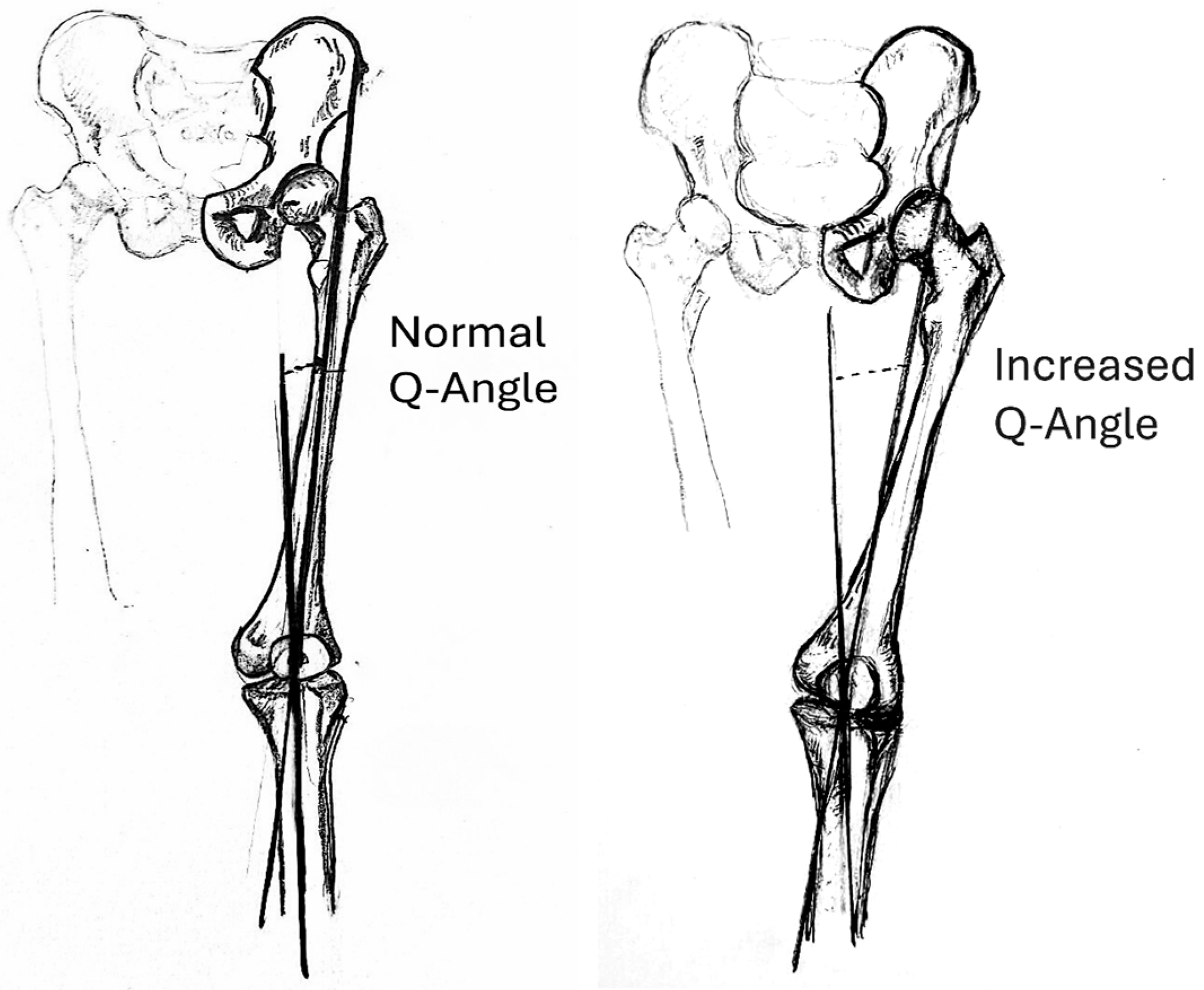

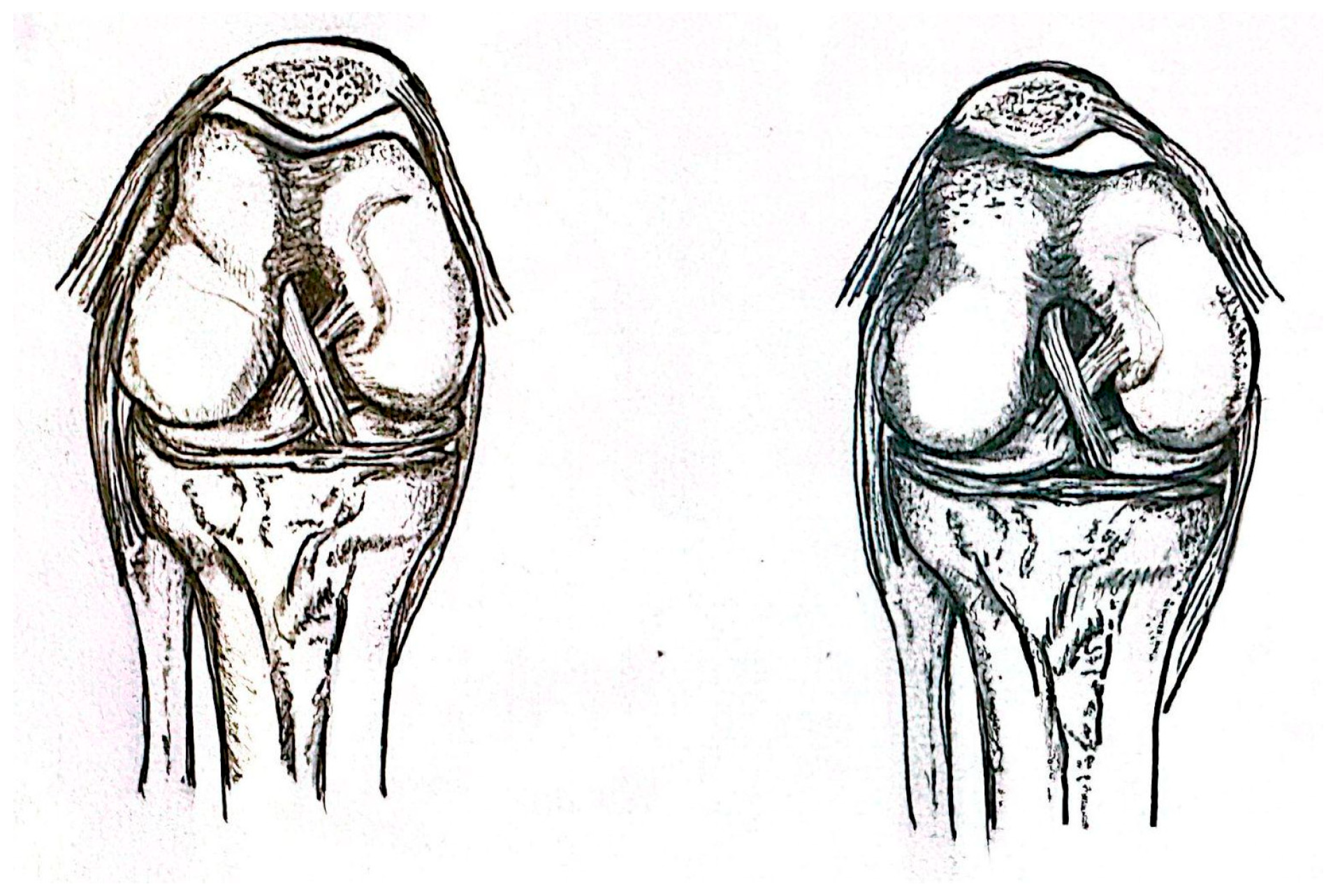

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

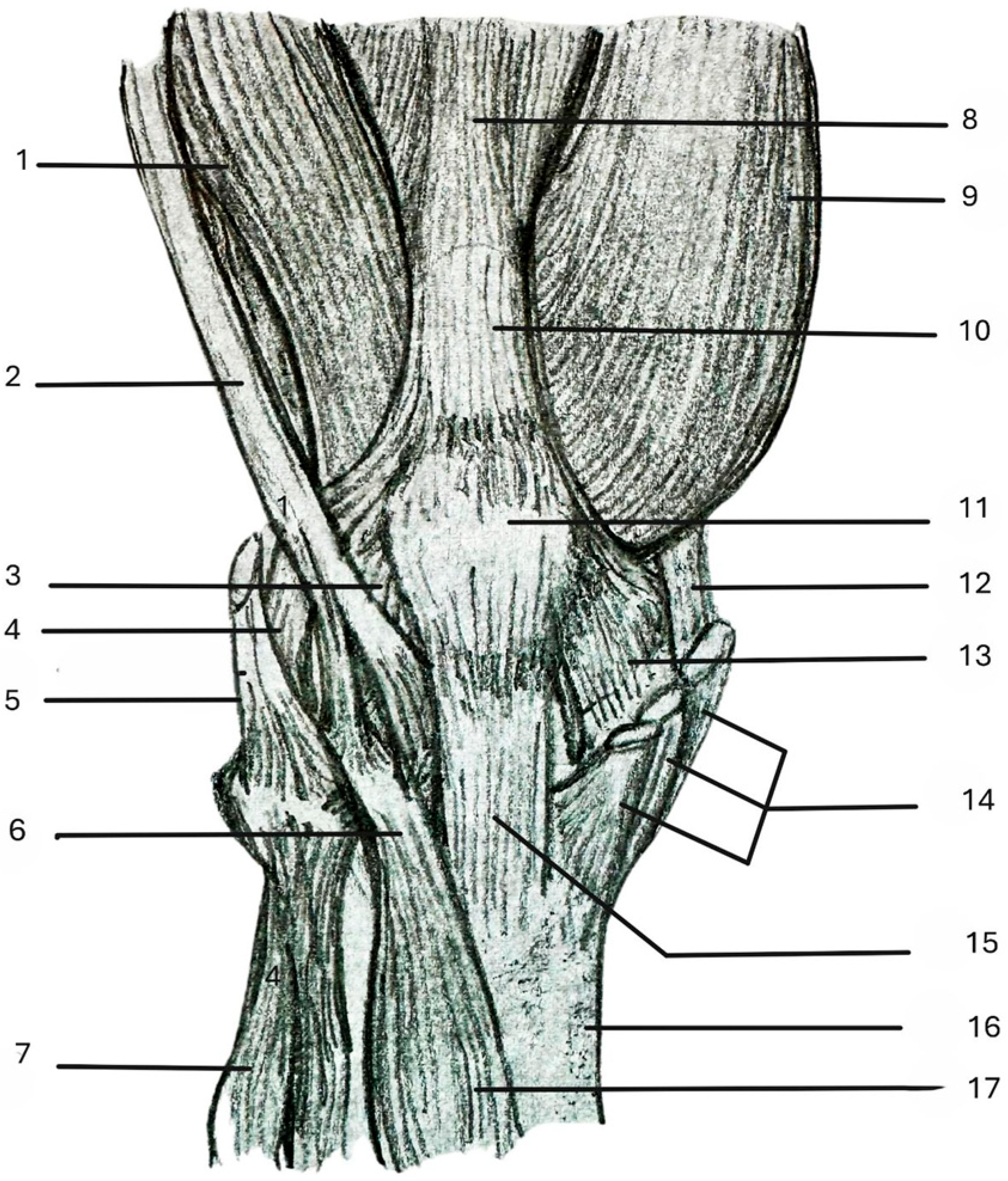

3. Surgical Techniques

3.1. Open Lateral Retinaculum Release Outside-In Technique

3.2. Arthroscopic Lateral Retinaculum Release Inside-Out Technique

3.3. Open Lateral Patellar Retinaculum Lengthening

3.4. Capsule-Uncut Immaculate (CUI)

3.5. Open Lateral Retinacular Release with IT Band Rotational Flap Repair—Flexed Knee Position

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yeung, A.Y.; Arbor, T.C.; Garg, R. Anatomy, Sesamoid Bones. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Saper, M.G.; Shneider, D.A. Diagnosis and treatment of lateral patellar compression syndrome. Arthrosc. Tech. 2014, 3, e633–e638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolowich, P.A.; Paulos, L.E.; Rosenberg, T.D.; Farnsworth, S. Lateral release of the patella: Indications and contraindications. Am. J. Sports Med. 1990, 18, 359–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, A.; Subhawong, T.K.; Carrino, J.A. A systematised MRI approach to evaluating the patellofemoral joint. Skelet. Radiol. 2011, 40, 375–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maniar, R.N.; Singhi, T.; Rathi, S.S.; Baviskar, J.V.; Nayak, R.M. Surgical technique: Lateral retinaculum release in knee arthroplasty using a stepwise, outside-in technique. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2012, 470, 2854–2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Migliorini, F.; Lüring, C.; Eschweiler, J.; Baroncini, A.; Driessen, A.; Spiezia, F.; Tingart, M.; Maffulli, N. Isolated Arthroscopic Lateral Retinacular Release for Lateral Patellar Compression Syndrome. Life 2021, 11, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.L.; Chen, J.B.; Li, T. Outcome and experience of arthroscopic lateral retinacular release combined with lateral patelloplasty in the management of excessive lateral pressure syndrome. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2021, 16, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhanasekararaja, P.; Soundarrajan, D.; Jisanth, J.B.; Rajkumar, N.; Rajasekaran, S. Influence of Lateral Retinacular Release in Realigning the Patella Between Varus and Valgus Knees in Primary Total Knee Arthroplasty. Indian J. Orthop. 2023, 57, 2073–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, J.H.; Kim, N.Y.; Song, K.I. Intraoperative patellar maltracking and postoperative radiographic patellar malalignment were more frequent in cases of complete medial collateral ligament release in cruciate-retaining total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg. Relat. Res. 2021, 33, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragoo, J.L.; Hirpara, A.; Sylvia, S.; McCarthy, T.; Constantine, E.; Pappas, G. Arthroscopic Lateral Retinacular-Lengthening Procedure. Arthrosc. Tech. 2024, 13, 102967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, D.J.; Doshi, C.; Parikh, S.N. Lateral Patellar Retinaculum Z-Lengthening. Arthrosc. Tech. 2021, 10, e1883–e1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merican, A.M.; Amis, A.A. Anatomy of the lateral retinaculum of the knee. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Br. 2008, 90–B, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagenstert, G.; Wolf, N.; Bachmann, M.; Gravius, S.; Barg, A.; Hintermann, B.; Wirtz, D.C.; Valderrabano, V.; Leumann, A.G. Open lateral patellar retinacular lengthening versus open retinacular release in lateral patellar hypercompression syndrome: A prospective double-blinded comparative study on complications and outcome. Arthroscopy 2012, 28, 788–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Shao, Z.; Liu, Q.; Cui, G. Lateral Retinacular Release for Treatment of Excessive Lateral Pressure Syndrome: The Capsule-Uncut Immaculate (CUI) Technique. Arthrosc. Tech. 2023, 12, e1991–e1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, D.H.; Post, W.R. Open or arthroscopic lateral release: Indications, techniques, and rehabilitation. Clin. Sports Med. 1997, 16, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, L.P.R.M.D.; Kawatake, E.H.; Pochini, A.C. Lateral patellar retinacular release: Changes over the last ten years. Rev. Bras. Ortop. 2017, 52, 442–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkousy, H. Complications in brief: Arthroscopic lateral release. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2012, 470, 2949–2953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Liu, Q.; Cui, G. Lateral patellar tilting can also result in cartilage lesions of tibial plateau—The characteristic features of excessive lateral pressure syndrome: A retrospective study of 141 cases. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2025, 26, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Shi, W.; Gao, J.; Hou, Y.; Yang, Y.; Cui, G. To compare the clinical outcomes of intra-capsular vs. extra-capsular lateral retinacular release in the treatment of excessive lateral pressure syndrome of patella using two novel surgical techniques: A retrospective comparative study. Chin. J. Traumatol. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamawandi, S.A.; Amin, H.I.; Al-Humairi, A.K. Open versus arthroscopic release for lateral patellar compression syndrome: A randomized-controlled trial. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2022, 142, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, D.B. Open lateral retinacular lengthening compared with arthroscopic release. A prospective, randomized outcome study. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 1997, 79, 1759–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, N.C. An analysis of complications in lateral retinacular release procedures. Arthroscopy 1989, 5, 282–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vialle, R.; Tanguy, J.Y.; Cronier, P.; Fournier, H.D.; Papon, X.; Mercier, P. Anatomic and radioanatomic study of the lateral genicular arteries: Application to prevention of postoperative hemarthrosis after arthroscopic lateral retinacular release. Surg. Radiol. Anat. 1999, 21, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shellock, F.G.; Mink, J.H.; Deutsch, A.L.; Fox, J.; Molnar, T.; Kvitne, R.; Ferkel, R. Effect of a patellar realignment brace on patellofemoral relationships: Evaluation with kinematic MR imaging. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 1994, 4, 590–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Technique | Indication(s) | Complication Rate | Cited Works |

|---|---|---|---|

| Open Lateral Retinacular Release Outside-in Technique | All grades of patellar tracking (1–4) | Study reported no complications during observation period | Maniar et al. [5] |

| Arthroscopic Retinacular Release Inside-out Technique | LPCS | 29% (9 of 31) | Migliorini et al. [6] |

| ELPS/LPCS | Not reported | Wang et al. [7] | |

| Open Lateral Patellar Retinaculum Lengthening Technique | * LPCS, patellofemoral pain syndrome, lateral patellar arthritis | N/A | Dragoo et al. [10] |

| * LPCS | N/A | Hayden et al. [11] | |

| * LPCS, painful tight lateral retinaculum | Study reported no complications during observation period | Pagenstert et al. [13] | |

| Capsule-Uncut Immaculate | ELPS/LPCS | N/A | Minghao et al. [14] |

| Open Lateral Retinacular Release with IT Band Rotational Flap Repair | LPCS | N/A | Saper et al. [2] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Nolan, M.; Marting, E.; Willard, S.; Applegate, J.; Turnow, M.; Manes, T.; Taylor, B.C. Lateral Patellar Compression Syndrome: Surgical Techniques and Treatment. Anatomia 2026, 5, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/anatomia5010004

Nolan M, Marting E, Willard S, Applegate J, Turnow M, Manes T, Taylor BC. Lateral Patellar Compression Syndrome: Surgical Techniques and Treatment. Anatomia. 2026; 5(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/anatomia5010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleNolan, Mason, Ethan Marting, Sarah Willard, James Applegate, Morgan Turnow, Taylor Manes, and Benjamin C. Taylor. 2026. "Lateral Patellar Compression Syndrome: Surgical Techniques and Treatment" Anatomia 5, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/anatomia5010004

APA StyleNolan, M., Marting, E., Willard, S., Applegate, J., Turnow, M., Manes, T., & Taylor, B. C. (2026). Lateral Patellar Compression Syndrome: Surgical Techniques and Treatment. Anatomia, 5(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/anatomia5010004