A Review of Beneficial Use and Management of Dredged Material

Abstract

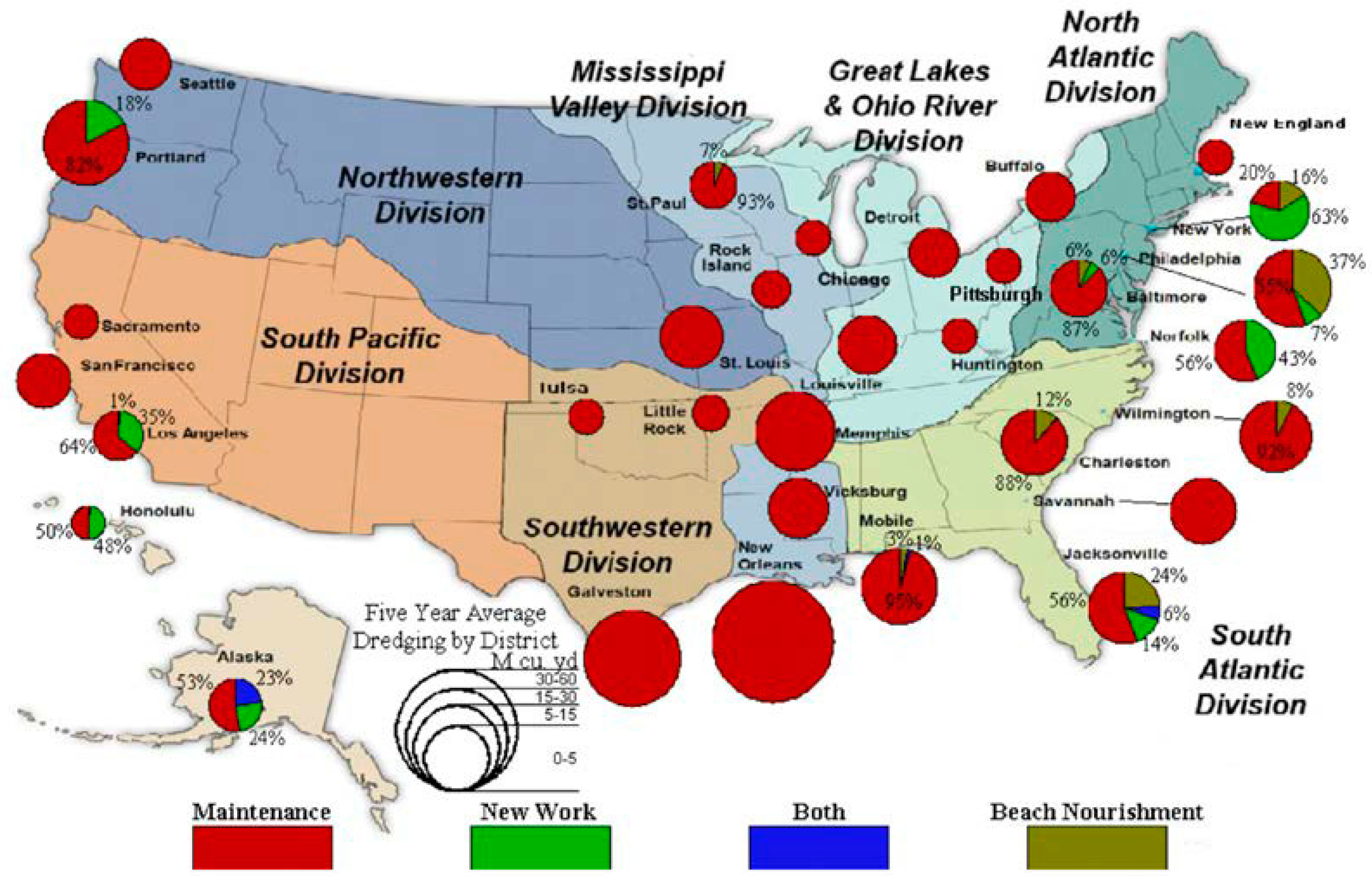

:1. Introduction

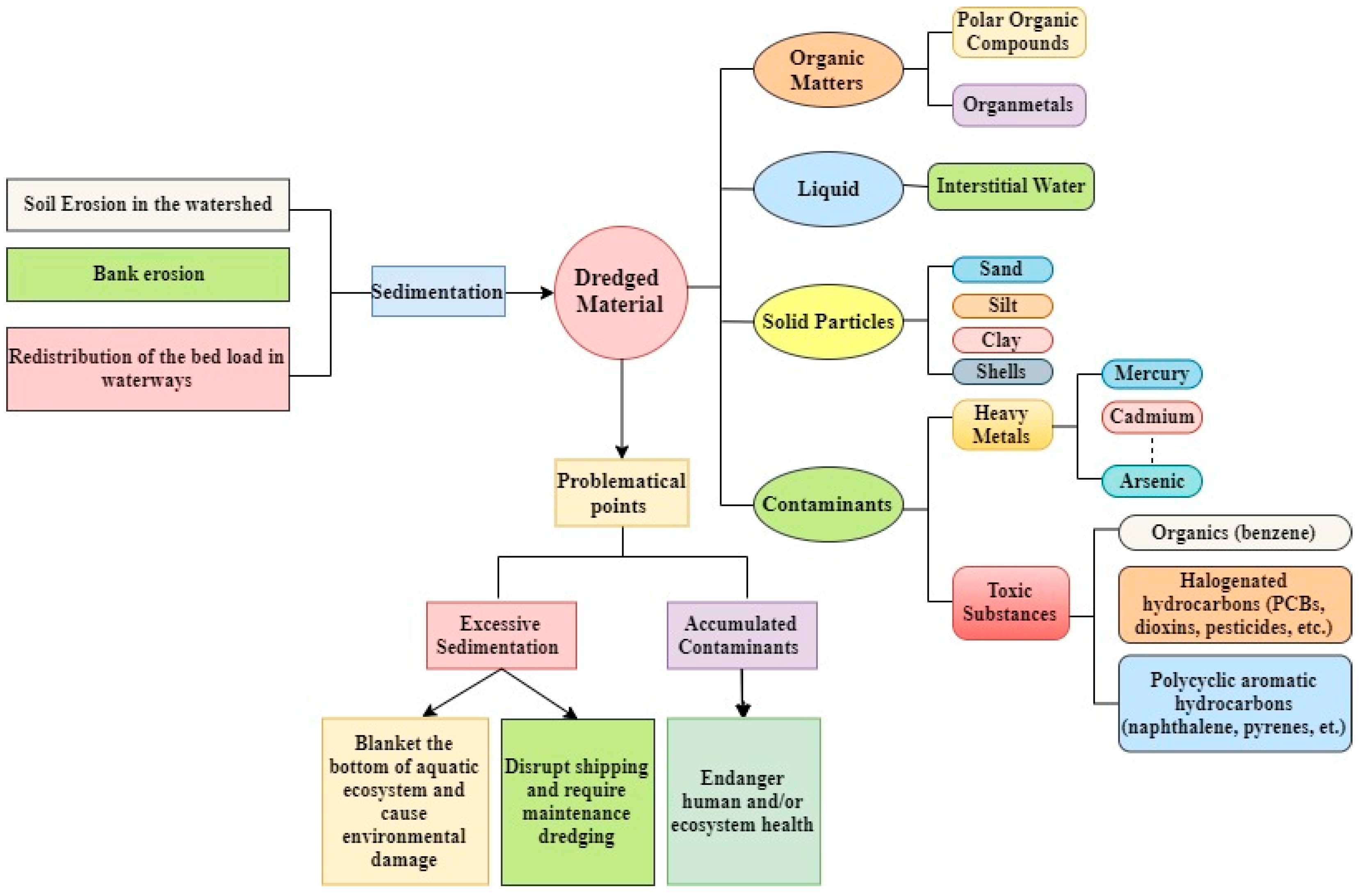

2. Dredged Material

2.1. Sources

2.2. Types and Classification

2.3. Chemical Composition

3. Policy Related to Beneficial Use

4. Beneficial Uses

4.1. Concrete Materials

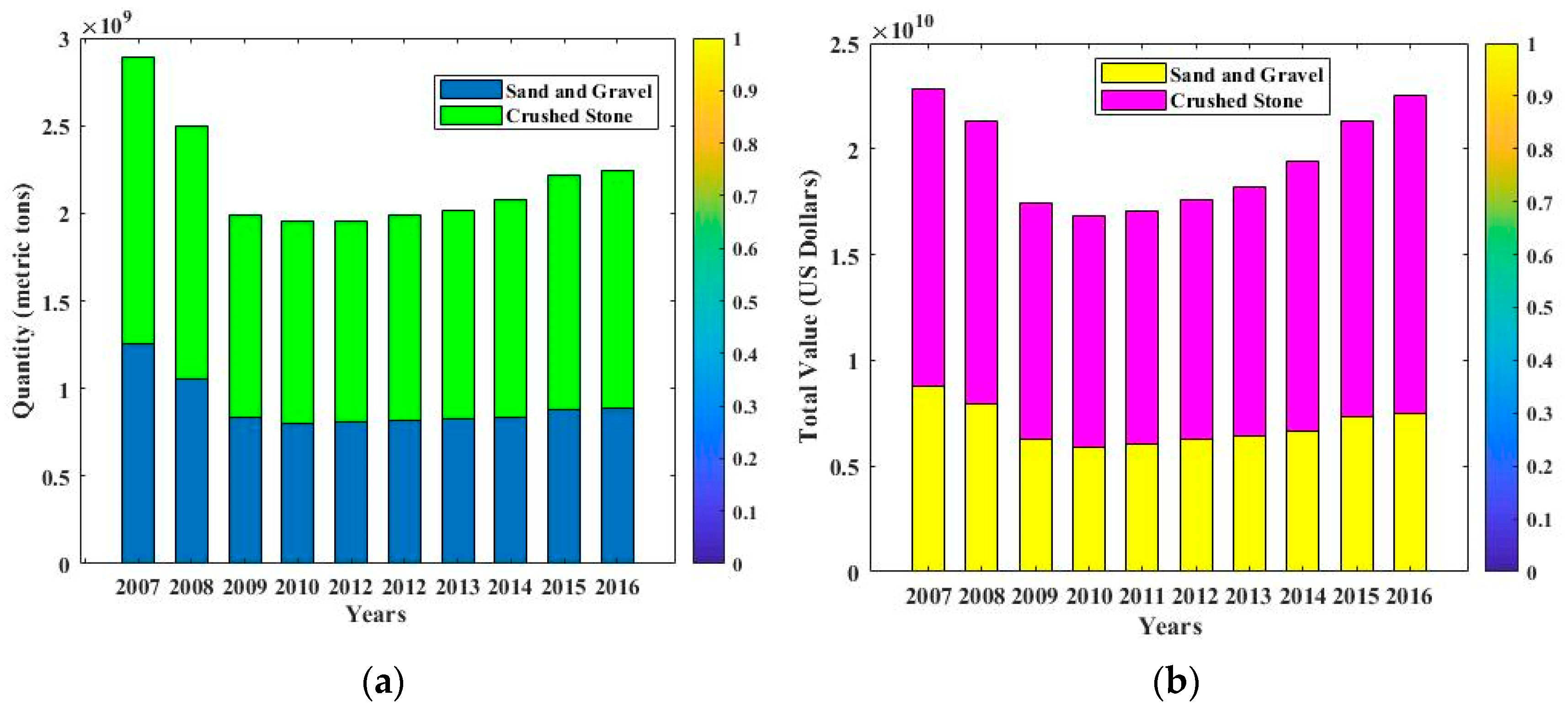

4.1.1. Sand Substitute

4.1.2. Cement Substitute/Supplementary Cementitious Material

4.2. Construction Products

4.2.1. Composite Material

4.2.2. Green Infrastructure Material

4.3. Roadway Construction

4.3.1. Fill Material

4.3.2. Stabilized Soil Subgrade

4.4. Habitat Building

4.5. Landfill Liner or Cap

4.6. Agriculture: Soil Reconstruction/Remediation

4.7. Beach Nourishment

4.8. Other Beneficial Uses

4.8.1. Embankment Fill

4.8.2. For Making Cement

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Beneficial Use of Dredged Material

- DM is composed of sorted solid particles, namely sand, silt, and clay derived from the watershed. It may contain heavy metals (e.g., mercury, cadmium, arsenic) and organics (e.g., benzene, naphthalene, dioxins);

- Based on the levels of heavy metals and toxic substances, DM can be categorized into three management levels, namely: Level 1—use, reuse for residential and recreational purposes; Level 2—use, reuse for industrial purposes; and Level 3—significant contamination with no use and reuse;

- Depending on the gradation and contamination level, DM can replace sand up to 50% with treatment and 100% after treatment in concrete materials. Specifically, if chloride content is less than 0.18% or the total chloride content in concrete is less than 0.34%, then it is safe in concrete against reinforcement corrosion;

- Contaminated DM could be treated by washing, grinding, and calcination to obtain the permissible limit of heavy metals. Washing the DM reduces free chloride content by up to 80%. Calcination is the heating of DM to a high temperature for the purpose of removing volatile substances. Calcination after grinding helps with the activation of clay minerals;

- Treated DM could be used as a partial cement substitute in concrete materials. However, it is not clear if the beneficial reuse of DM as raw material for cement production is economically acceptable for real practices;

- DM could be used for making products such as tiles, bricks, and blocks, but the cost associated with each product was not available in the literature;

- DM with less than 20% water content can be used as fill material in both the foundation and base layer of pavements;

- For pavement applications, DM could be used as subgrade after treating with class C fly ash;

- DM is suitable for many agricultural applications;

- Another application of DM is habitat building, landfill liner or cap, and beach nourishment.

5.2. Practical Challenges/Limitations in Using and Managing Dredged Material

5.3. Tips/Resources to Help Communities Become Involved with Beneficial Use

- Form a committee, task force, or subgroup within existing local government agencies such as the Farm Bureau or Environmental Protection Agency at a state administration level. For instance, the Illinois Farm Bureau can invite farmers, port authorities, economic development groups, institutional researchers or scientists, college students, etc., from different areas in the state to participate in the discussion and proposal-making in terms of using DM along with other wastes to custom more productive soils for farming;

- Develop a web-based tool like a website to provide the public with the most accessible and up-to-date information about the beneficial reuse of DM and potential risks affiliated with it, the frequently asked questions and corresponding answers, and a map finder that gives specific location information about the sediments nearby. The Natural Infrastructure Opportunities Tool (NIOT) is one example that helps match available resources for natural infrastructure projects by compiling placement area capacities, dredging plans, and sediment characteristic descriptions and help to identify beneficial use and infrastructure opportunities;

- Organize a seminar series at nearby higher education institutions or professional organizations to systematically educate the public about the economic benefits of using DM.

5.4. Next Steps

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Al2O3 | Alumina |

| As | Arsenic |

| BCDC | Bay Conservation and Development Commission |

| BOF | Basic Oxygen Furnace |

| CaO | Calcium Oxide |

| CDFs | Confined Disposal Facilities |

| Cr | Chromium |

| C-S-H | Calcium-Silicate-Hydrate |

| Cu | Copper |

| CWA | Clean Water Act |

| CZMA | Coastal Zone Management Act |

| DM | Dredged Materials |

| DOT | Department of Transportation |

| Fe2O3 | Iron Oxide |

| GI | Green Infrastructure |

| H3PO4 | Phosphoric Acid |

| MPCA | Minnesota Pollution Control Agency |

| Ni | Nickel |

| Pb | Lead |

| RCRA | Resource Conservation and Recovery Act |

| SiO2 | Silica |

| SRV | Soil Reference Value |

| TSCA | Toxic Substances Control Act |

| USACE | United States Army Corps of Engineers |

| USEPA | United States Environmental Protection Agency |

| USGS | United States Geological Survey |

| Zn | Zinc |

References

- Sheehan, C.; Harrington, J.J.W.M. Management of dredge material in the Republic of Ireland—A review. Waste Manag. 2012, 32, 1031–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USEPA; USACE. Identifying, Planning, Financing Beneficial Use Projects Using Dredged Material: Beneficial Use Planning Manual; Defense Technical Information Center: Fort Belvoir, VA, USA, 2007; p. 115.

- Dia, M.; Ramaroson, J.; Nzihou, A.; Zentar, R.; Abriak, N.E.; Depelsenaire, G.; Germeau, A. Effect of Chemical and Thermal Treatment on the Geotechnical Properties of Dredged Sediment. Procedia Eng. 2014, 83, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa-Pierce, B.A.; Weinstein, M.P. Use of dredge materials for coastal restoration. Ecol. Eng. 2002, 19, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limeira, J.; Etxeberria, M.; Agulló, L.; Molina, D. Mechanical and durability properties of concrete made with dredged marine sand. Constr. Build. Mater. 2011, 25, 4165–4174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Army Corps of Engineers. Dredging and Dredged Material Management; United States Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2015; p. 920. Available online: http://www.publications.usace.army.mil/Portals/76/Publications/EngineerManuals/EM_1110-2-5025.pdf (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE). Inner Harbor Navigation Canal Lock. 2017. Available online: https://www.mvn.usace.army.mil/Portals/56/docs/Projects/IHNC/IHNC%20Lock%20Study-%20Eng%20Appendix%20B%20.pdf?ver=2016-12-30-131854-877 (accessed on 29 November 2020).

- Mostafa, Y.E.S. Environmental impacts of dredging and land reclamation at Abu Qir Bay, Egypt. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2012, 3, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Y.C.; Lin, S.K.; Ju, Y.R.; Wu, C.H.; Lin, Y.L.; Chen, C.W.; Di Dong, C. Reutilization of dredged harbor sediment and steel slag by sintering as lightweight aggregate. Process. Saf. Environ. Prot. 2019, 126, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolam, S.G.; Rees, H.L.; Somerfield, P.; Smith, R.; Clarke, K.R.; Warwick, R.M.; Atkins, M.; Garnacho, E. Ecological consequences of dredged material disposal in the marine environment: A holistic assessment of activities around the England and Wales coastline. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2006, 52, 415–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cesar, A.; Lia, L.R.B.; Pereira, C.D.S.; Santos, A.R.; Cortez, F.S.; Choueri, R.B.; De Orte, M.R.; Rachid, B.R.F. Environmental assessment of dredged sediment in the major Latin American seaport (Santos, São Paulo—Brazil): An integrated approach. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 497–498, 679–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, G.R.; Knight, D.L.; Commission, G.L.; Clark, G.R. Summit on the Beneficial Use of Dredged Materials: Turning a Surplus Material into a Commodity of Value; U.S. Department of Transportation: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. Available online: https://rosap.ntl.bts.gov/view/dot/27782 (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Bhairappanavar, S.; Liu, R.; Coffman, R. Beneficial Uses of Dredged Material in Green Infrastructure and Living Architecture to Improve Resilience of Lake Erie. Infrastructures 2018, 3, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amar, M.; Benzerzour, M.; Kleib, J.; Abriak, N.E. From dredged sediment to supplementary cementitious material: Characterization, treatment, and reuse. Int. J. Sediment Res. 2021, 36, 92–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA). Handbook—Remediation of Contaminated Sediments; United States Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 1991.

- Agostini, F.; Skoczylas, F.; Lafhaj, Z. About a possible valorisation in cementitious materials of polluted sediments after treatment. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2007, 29, 270–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebbs, S.; Talbott, J.; Sankaran, R. Cultivation of garden vegetables in Peoria Pool sediments from the Illinois River: A case study in trace element accumulation and dietary exposures. Environ. Int. 2006, 32, 766–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oudejans, L. Report on the 2016 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) International Decontamination Research and Development Conference; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2017.

- Minnesota Pollution Control Agency Report. 2015. Available online: https://www.pca.state.mn.us/sites/default/files/lrw-sw-1sy15.pdf (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Lee, C.R.; Brandon, D.L.; Price, R.A. Manufactured Soil Field Demonstration for Constructing Wetlands to Treat Acid Mine Drainage on Abandoned Minelands; U.S. Army Corps of Engineers: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. Available online: https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA474492.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- Ghiorso, M. Magmatic Process Modeling. In Encyclopedia of Geochemistry; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibold, E.; Berger, W. The Sea Floor; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, W.M. Encyclopedia of Geochemistry; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; Available online: https://www.springer.com/gp/book/9783319393117 (accessed on 12 June 2021).

- Gallmetzer, I.; Haselmair, A.; Stachowitsch, M.; Zuschin, M. An innovative piston corer for large-volume sediment samples. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 2016, 14, 698–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustyn, A.; Chopra, S.; Curley, R.; Jain, P.; Lotha, G.; Cunningham, J.M.; Manchanda, K.; Rafferty, J.P.; Pallardy, R.; Sampaolo, M.; et al. Sedimentary Rock, (n.d.). Available online: https://www.britannica.com/science/sedimentary-rock (accessed on 12 June 2021).

- Krause, P.R.; Mcdonnell, K.A. The Beneficial Reuse of Dredged Material for Upland Disposal; Harding Lawson Associates: Novato, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez, A.; Kot, C.; Piatkowski, D. Review of Sea Turtle Entrainment Risk by Trailing Suction Hopper Dredges in the US Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico and the Development of the ASTER Decision Support Tool; US Department of the Interior, Bureau of Ocean Energy Management: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; p. 266. Available online: https://espis.boem.gov/final%20reports/5652.pdf (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- USEPA. Evaluating Environmental Effects of Dredged Material Management Alternatives—A Technical Framework. 2004. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2015-09/documents/2004_08_20_oceans_regulatory_dumpdredged_framework_techframework.pdf (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Hails, J.R. Grab samplers. In Beaches and Coastal Geology, 1986th ed.; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2006; pp. 454–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folk, R.L. Petrology of Sedimentary Rocks; Austin Hemphill Publishing Company: Austin, TX, USA, 1974; p. 182. [Google Scholar]

- Naqvi, S.M.; Pullen, E.J. Effects of Beach Nourishment and Borrowing on Marine Organisms; National Technical Information Service, Operations Division: Fort Belvoir, VA, USA, 1982. [CrossRef]

- Wentworth, C.K. A Scale of Grade and Class Terms for Clastic Sediments. J. Geol. 1922, 30, 377–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepard, F.P. Nomenclature Based on Sand-silt-clay Ratios. J. Sediment. Res. 1954, 24, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grubb, D.G.; Davis, A.F.; Sands, S.C.; Carnivale, M.; Wartman, J.; Gallagher, P.M. Field Evaluation of Crushed Glass–Dredged Material Blends. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2006, 132, 577–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malasavage, N.E.; Jagupilla, S.; Grubb, D.G.; Wazne, M.; Coon, W.P. Geotechnical Performance of Dredged Material—Steel Slag Fines Blends: Laboratory and Field Evaluation. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2012, 138, 981–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folk, L. The Distinction between Grain Size and Mineral Composition in Sedimentary-Rock Nomenclature. J. Geol. 1954, 62, 344–359. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/30065016 (accessed on 30 May 2023). [CrossRef]

- Schlee, J. Atlantic Continental Shelf and Slope of the United States—Sediment Texture of the Northeastern Part; United States Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 1973. [CrossRef]

- Poppe, L.J.; Williams, S.J.; Paskevich, V.F. USGS East-Coast Sediment Analysis. Procedures, Database, and GIS Data: U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2005-1001; United States Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2005.

- Ramaroson, J.; Dirion, J.L.; Nzihou, A.; Depelsenaire, G. Characterization and kinetics of surface area reduction during the calcination of dredged sediments. Powder Technol. 2009, 190, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, M.H.F.; Gobbi, A.; Réus, G.C.; Helene, P. Reinforced concrete in marine environment: Effect of wetting and drying cycles, height and positioning in relation to the sea shore. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 44, 452–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoual-Benslafa, F.K.; Kerdal, D.; Ameur, M.; Mekerta, B.; Semcha, A. Durability of Mortars Made with Dredged Sediments. Procedia Eng. 2015, 118, 240–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.Y. Durability of self-consolidating lightweight aggregate concrete using dredged silt. Constr. Build. Mater. 2009, 23, 2332–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Geological Survey (USGS). Aggregates Data by State, Type, and End Use; 1971–2016, (n.d.). Available online: https://www.usgs.gov/atom/99519 (accessed on 29 November 2020).

- Siham, K.; Fabrice, B.; Edine, A.N.; Patrick, D. Marine dredged sediments as new materials resource for road construction. Waste Manag. 2008, 28, 919–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illinois Environmental Protection Agency. Tiered Approach to Corrective Action Objectives; Illinois Environmental Protection Agency: Springfield, IL, USA, 1997.

- Clare, K.E.; Sherwood, P.T. The effect of organic matter on the setting of soil-cement mixtures. J. Appl. Chem. 1954, 4, 625–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, N.; Jin, F.; Kong, X.; Xu, Y.; Zhou, J.; Wang, B.; Wu, H. Interface and anti-corrosion properties of sea-sand concrete with fumed silica. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 188, 1085–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, T.A.; Kamali-Bernard, S.; Prince, W.A. Design of new blended cement based on marine dredged sediment. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 41, 602–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couvidat, J.; Benzaazoua, M.; Chatain, V.; Bouamrane, A.; Bouzahzah, H. Feasibility of the reuse of total and processed contaminated marine sediments as fine aggregates in cemented mortars. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 112, 892–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millrath, K.; Kozlova, S.; Meyer, C.; Shimanovich, S. Beneficial Use of Dredge Material, Progress Report; Columbia University: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ozer-Erdogan, P.; Basar, H.M.; Erden, I.; Tolun, L. Beneficial use of marine dredged materials as a fine aggregate in ready-mixed concrete: Turkey example. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 124, 690–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Huang, R.; Fu, J.; Tang, W.; Dong, Z.; Cui, H. Discussion and experiments on the limits of chloride, sulphate and shell content in marine fine aggregates for concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 159, 725–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chen, L.; Tsang, D.C.W.; Li, J.S.; Baek, K.; Hou, D.; Ding, S.; Poon, C.S. Recycling dredged sediment into fill materials, partition blocks, and paving blocks: Technical and economic assessment. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 199, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stollenwerk, J.; Smith, J.; Ballavance, B.; Rantala, J.; Thompson, D.; McDonald, S.; Schnick, E. Managing Dredged Materials; Minnesota Pollution Control Agency: Baxter, MN, USA, 2014. Available online: https://www.pca.state.mn.us/sites/default/files/wq-gen2-01.pdf (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Park, J.; Son, Y.; Noh, S.; Bong, T. The suitability evaluation of dredged soil from reservoirs as embankment material. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 183, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, M.; Sun, C.; Xu, J.; Dong, J.; Ke, W. Role of Fe oxides in corrosion of pipeline steel in a red clay soil. Corros. Sci. 2013, 80, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achour, R.; Zentar, R.; Abriak, N.E.; Rivard, P.; Gregoire, P. Durability study of concrete incorporating dredged sediments. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2019, 11, e00244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Zhou, Y.; Jia, R.; Wang, W.; Wu, Y. Preparation of non-sintered lightweight aggregates from dredged sediments and modification of their properties. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 132, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwers, H.J.H.; Augustijn, D.C.M.; Krikke, B.; Honders, A. Use of cement and quicklime to accelerate ripening and immobilize contaminated dredging sludge. J. Hazard. Mater. 2007, 145, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Junakova, N.; Junak, J. Recycling of Reservoir Sediment Material as a Binder in Concrete. Procedia Eng. 2017, 180, 1292–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Pang, S.D. Value-added utilization of marine clay as cement replacement for sustainable concrete production. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 198, 867–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lirer, S.; Liguori, B.; Capasso, I.; Flora, A.; Caputo, D. Mechanical and chemical properties of composite materials made of dredged sediments in a fly-ash based geopolymer. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 191, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mymrin, V.; Stella, J.C.; Scremim, C.B.; Pan, R.C.Y.; Sanches, F.G.; Alekseev, K.; Pedroso, D.E.; Molinetti, A.; Fortini, O.M. Utilization of sediments dredged from marine ports as a principal component of composite material. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 4041–4049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mymrin, V.; Pan, R.C.Y.; Alekseev, K.; Avanci, M.A.; Stella, J.C.; Scremim, C.B.; Schiavini, D.N.; Pinto, L.S.; Berton, R.; Weber, S.L. Overburden soil and marine dredging sludge utilization for production of new composites as highly efficient environmental management. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 236, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, R.; He, Z.; Ba, M.; Li, Y. Preparation and microstructure of green ceramsite made from sewage sludge. J. Wuhan Univ. Technol. Sci. Ed. 2012, 27, 149–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamer, K.; Karius, V. Brick production with dredged harbour sediments. An industrial-scale experiment. Waste Manag. 2002, 22, 521–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Coffman, R. Lightweight Aggregate Made from Dredged Material in Green Roof Construction for Stormwater Management. Materials 2016, 9, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colin, D. Valorisation de sédiments fins de dragage en technique routière. Doctoral Dissertation, Université de Caen, Caen, France, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Davidovits, J. Properties of Geopolymer Cements. In Proceedings of the First International Conference on Alkaline Cements and Concretes, Kiev, Ukraine, 11–14 October 1994; pp. 131–149. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Zentar, R.; Abriak, N.E. Durability and Swelling of Solidified/Stabilized Dredged Marine Soils with Class-F Fly Ash, Cement, and Lime. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2018, 30, 04018013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natural Resources Conservation Services (NRCS). Hydric Soils—Introduction, (n.d.). Available online: https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/detail/soils/use/hydric/?cid=nrcs142p2_053961 (accessed on 29 November 2020).

- Dubois, V.; Abriak, N.E.; Zentar, R.; Ballivy, G. The use of marine sediments as a pavement base material. Waste Manag. 2009, 29, 774–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantre, S.; Saathoff, F. Investigation of Dredged Materials in Combination with Geosynthetics Used in Dike Construction. Procedia Eng. 2013, 57, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Abriak, N.E.; Zentar, R. Dredged marine sediments used as novel supply of filling materials for road construction. Mar. Georesour. Geotechnol. 2016, 35, 472–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Yin, J.; Soleimanbeigi, A.; Likos, W.J. Effects of Curing Time and Fly Ash Content on Properties of Stabilized Dredged Material. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2017, 29, 04017199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.M.; Rabbanifar, S.; Brake, N.A.; Qian, Q.; Kibodeaux, K.; Crochet, H.E.; Oruji, S.; Whitt, R.; Farrow, J.; Belaire, B.; et al. Stabilization of Silty Clayey Dredged Material. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2018, 30, 04018199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maherzi, W.; Abdelghani, F.B. Dredged Marine Sediments Geotechnical Characterisation for Their Reuse in Road Construction. Eng. J. 2014, 18, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, C.; Deng, Y.; Zhou, A.; Feng, Q.; Ye, H.; Zha, F. Backfilling performance of mixtures of dredged river sediment and iron tailing slag stabilized by calcium carbide slag in mine goaf. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 189, 849–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Develioglu, I.; Pulat, H.F. Compressibility behaviour of natural and stabilized dredged soils in different organic matter contents. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 228, 116787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yozzo, D.J.; Wilber, P.; Will, R.J. Beneficial use of dredged material for habitat creation, enhancement, and restoration in New York–New Jersey Harbor. J. Environ. Manag. 2004, 73, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, D.; Kasul, R. Value of Offshore Dredged Material Berms for Fishery Resources. In Proceedings of the Dredging’94 International Conference, Lake Buena Vista, FL, USA, 13–16 November 1994; pp. 938–945. [Google Scholar]

- Marlin, J.C. Evaluation of sediment removal options and beneficial use of dredged material for Illinois river restoration: Preliminary report. In Proceedings of the Western Dredging Association Twenty-Second Technical Conference and Thirty-Fourth Texas A&M Dredging Seminar, Denver, CO, USA, 15–18 June 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Koropchak, S.C.; Daniels, W.L.; Wick, A.; Whittecar, G.R.; Haus, N. Beneficial Use of Dredge Materials for Soil Reconstruction and Development of Dredge Screening Protocols. J. Environ. Qual. 2016, 45, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, R.K.; Herbich, J.B.; Hossner, L.R. With Dredged Material. J. Hazard. Mater. 1997, 53, 141–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Analysis Potential for Use of Dredged Materials at Landfills, n.d. Available online: https://bcdc.ca.gov/planning/reports/AnalysisPotentialForUseOfDredgedMaterialsAtLandfills1995.pdf (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Darmody, R.G.; Marlin, J.C. Illinois River dredged sediment: Characterization and utility for brownfield reclamation. In Proceedings of the 25th Annual Meetings of the American Society of Mining and Reclamation and 10th Meeting of IALR, Richmond, VA, USA, 14–19 June 2008; American Society of Mining and Reclamation: Champaign, UL, USA, 2008; pp. 253–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darmody, R.G.; Marlin, J.C.; Talbott, J.; Green, R.A.; Brewer, E.F.; Stohr, C. Dredged Illinois River Sediments. J. Environ. Qual. 2004, 33, 458–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diaz, D.R.; Darmody, R. Illinois River Dredged Sediments and Biosolids Used as Greenhouse Soil Mixtures; (TR Series (Illinois Waste Management and Research Center); No. TR-038); Waste Management and Research Center: Champaign, IL, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Marlin, J.C.; Darmody, R.G. Beneficial Use of Illinois River Sediment for Agricultural and Landscaping Application; Illinois Sustainable Technology Center: Champaign, IL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Aouad, G.; Laboudigue, A.; Gineys, N.; Abriak, N.E. Dredged sediments used as novel supply of raw material to produce Portland cement clinker. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2012, 34, 788–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sources | Attribute | Description | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Formation and Sedimentation | Land Areas | Soil erosion in the waterbed, band erosion, and redistribution of the bedload in the waterways. | [15] |

| Weathering and erosion of minerals, organic material, soil in upstream areas, and riverbanks. | [16] | ||

| Mud, sand, and silt that accumulate in navigable channels, bay inlets, and marinas from the erosion of upstream sediments. | [17] | ||

| Soil erosion from uplands and hillslopes, as well as infrequent events such as mass wasting and erosion from areas affected by fire; streambank erosion in the stream corridor. | [18] | ||

| Sheet, rill, and gully erosion from upland; ravine, bluff, and streambank erosion near channels. | [19] | ||

| Marine Areas | Rocks and soil particles transported from land areas, as well as the remains of marine organisms, products of submarine volcanism, chemical precipitates from seawater, and materials from outer space that accumulate on the seafloor. | [20] | |

| A mixture of material deposited on the seafloor that originated from the erosion of continents, volcanism, biological productivity, hydrothermal vents, and/or cosmic debris. | [21] | ||

| Deposits accumulating below the sea, including debris from weathering and erosion on land, organisms, organic matter, minerals precipitated from seawater and volcanic products such as ash and pumice. | [22] | ||

| Artificial Dredging | Coring | Use a plunger to extract sediments and their faunas from open marine, estuarine, and limnic environments for performing tests on dredged material. | [7,18,23] |

| Grab | A more ideal way to collect fine-grained cohesive sediments, such as silt and clay, than noncohesive sands, comminuted shells, and gravel from a variety of aquatic environments for chemical and toxicological analyses of sediments or other purposes. | [18,24] | |

| Suction | The most commonly used method to dredge sediments on a large scale | [25] |

| Classification Standard | Attribute | Description | Emphasis | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Particle Size (Texture) | Wentworth Grade Scale | Standardized definitions of the fractions. Gravel (dn > 2 mm); sand (62.5 um< dn < 2 mm); silt (4 um <dn< 62.5 um); clay (dn < 4 um). | [28] | ||

| Shepard’s Classification Scheme | Original | A single ternary diagram with sand, silt, and clay to graphically show the relative proportions among them within a sample. | The ratios of sand, silt, and clay | [29,30] | |

| Modified | Addition of a second ternary diagram to account for the gravel fraction. | [31] | |||

| Folk’s Classification Scheme | Two triangular diagrams with 21 major categories and uses the term mud (defined as silt plus clay). | Gravel | [30,32,33] | ||

| Composition/Formation | Lithogenous | Sediments from the land form through the weathering process (terrigenous and red clay). | [34,35] | ||

| Biogenous | Remnants of organisms that refused to be dissolved (shells). | ||||

| Hydrogenous | Chemical precipitates or minerals solidified out of ocean water. | ||||

| Cosmogenous | Materials such as meteorites or asteroids from outer space. | ||||

| Source | SiO2 | Al2O3 | CaO | Fe2O3 | Na2O | K2O | MgO | MnO | TiO2 | P2O5 | SO3 | Cl | Cr2O7 | LOI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [39] | 44.17 | 14.18 | 12.17 | 4.72 | 4.70 | 3.84 | 2.617 | 0.08 | 0.50 | - | - | - | - | - |

| [40] | 50.48 | 14.89 | 14.39 | 1.40 | 2.04 | 5.89 | - | 0.79 | 0.24 | 1.93 | 1.43 | 0.05 | - | |

| [41] | 71.0 | 10.1 | 2.6 | 3.8 | 4.5 | 3.4 | - | 0.1 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.6 | - | 3.6 |

| [42] | 45 | 4.1 | 25 | 0.5 | - | - | 0.3 | - | - | - | 0.001 | 1.7 | - | - |

| [5] | 19.0 | 5.6 | 64.5 | 3.7 | 0.1 | 0.9 | 2.0 | - | - | - | 3.2 | - | 1 | |

| [37] | 53.48 | 25.91 | 0.93 | 9.41 | 0.49 | 3.81 | 2.12 | 0.11 | 1.16 | 0.14 | - | - | - | 1.99 |

| 54.48 | 24.37 | 1.57 | 8.01 | 1.04 | 2.89 | 1.82 | 0.14 | 1.05 | 0.39 | - | - | - | 3.43 | |

| 52.96 | 21.69 | 2.22 | 11.64 | 0.63 | 4.13 | 1.58 | 0.21 | 1.33 | 0.55 | - | - | - | 2.22 | |

| [43] | 70.11 | 11.76 | 0.91 | 4.89 | 1.26 | 1.76 | 0.89 | - | 0.87 | - | - | - | - | 4.5 |

| [44] | 56.65 | 15.31 | 5.37 | 6.15 | 1.25 | 1.54 | 2.67 | - | - | - | 2.05 | - | - | - |

| [45] | 56.87 | 22.93 | - | 10.79 | 0.33 | 2.66 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| [46] | 58.3 | 8.8 | 14.7 | 3.6 | 1.3 | 1.5 | 2.6 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 2.2 | 0.1 | - | 18.9 |

| [9] | 57.8 | 18.7 | 2.05 | 7.67 | 2.05 | 3.93 | 2.64 | 0.07 | - | 0.28 | 1.95 | - | - | 6.6 |

| [47] | 63.09 | 16.76 | 2.59 | 7.95 | - | 2.37 | 5.49 | 0.20 | 1.04 | 0.20 | - | - | - | - |

| [48] | 71.0 | 10.1 | 2.6 | 3.8 | 1.4 | 3.4 | 1.1 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 1.0 | - | 0.1 | 3.6 |

| [40] | 61.92 | 15.09 | 9.56 | 3.55 | 1.71 | 2.63 | 2.52 | 0.08 | 0.63 | 0.19 | 0.92 | 0.91 | - | <2.3 |

| 34.87 | 5.79 | 27.10 | 7.08 | 0.78 | 0.42 | 20.63 | 0.14 | 0.27 | 0.09 | 0.76 | 1.75 | 0.159 | 4.11 | |

| 53.24 | 18.33 | 8.93 | 6.45 | 1.50 | 2.30 | 4.01 | 0.20 | 1.19 | 0.30 | 1.26 | 1.91 | 0.049 | 4.72 | |

| 47.31 | 14.40 | 17.54 | 6.43 | 1.52 | 2.11 | 5.28 | 0.15 | 0.77 | 0.21 | 2.85 | 1.23 | 0.064 | 4.19 |

| Concentration Unit | Cd | Cu | As | Hg | Pb | Cr | Zn | Ni | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mg/kg | 1 | 22.87 | 6.80 | 0.557 | 15.93 | - | 81.60 | 34.50 | [37] |

| 1 | 5.70 | 7.13 | 0.242 | 14.43 | - | 76.30 | 7.80 | ||

| 1 | 18.97 | 5.97 | 0.227 | 47.20 | - | 93.30 | 19.07 | ||

| mg/kg | <0.1 | 15.2 | 7.9 | 0.3 | 11.8 | 85 | 42 | 37.3 | [39] |

| 0.1 | 17.4 | 8.43 | <0.01 | 5.64 | 905 | 34.8 | 687 | ||

| 0.43 | 23 | 347 | 2.33 | 13 | 140 | 128 | 132 | ||

| 0.17 | 46 | 12.80 | 0.09 | 35.4 | 111 | 77 | 55 | ||

| 0.08 | - | - | 1.64 | 42.24 | 34.16 | 390.8 | 342.5 | [42] | |

| 0.16 | - | - | 1.02 | 89.65 | 118.3 | 335.5 | 9.6 | ||

| mg/kg | <0.05 | - | <0.05 | - | <0.25 | <0.05 | - | <0.05 | [49] |

| mg/kg | 0.68 | 0.8 | 0.2 | - | 1.92 | 0.9 | 12.9 | 0.2 | [50] |

| mg/kg (dry) | 15.3 | - | - | - | 823 | 196.9 | 2532 | - | [51] |

| 38 | - | - | - | 1143 | 218 | 5438 | - | ||

| mg/kg | <0.42 | 27 | 18.03 | 0.18 | 39 | 44 | 151 | 25 | [52] |

| mg/kg | <0.1 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.01 | <1 | <0.1 | <0.5 | <0.4 | [53] |

| mg/kg | <0.1 | 15.2 | 7.9 | 0.3 | 11.8 | 85 | 42 | 37.3 | [40] |

| 0.1 | 17.4 | 8.43 | <0.01 | 5.64 | 905 | 34.8 | 687 | ||

| 0.43 | 23 | 347 | 2.33 | 13 | 140 | 128 | 132 | ||

| 0.17 | 46 | 12.80 | 0.09 | 35.4 | 111 | 77 | 55 |

| Name of Policies | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Clean Water Act (CWA) | Regulates discharge of pollutants into the waters (use of dredged material for artificial reef and berm development). |

| 2 | National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) | Environmental effects of proposed Federal agency actions (20 years dredged material management plan for the Calumet River and Harbor). |

| 3 | Endangered Species Act (ESA) | For protecting imperiled species (to conduct any new or maintenance activity or project that may require a permit). |

| 4 | Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) | Proper management of hazardous and non-hazardous solid waste (regarding the handling, transport, and disposal of wastes). |

| 5 | Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) | Regulates the introduction of new or already existing chemicals (regarding the handling, transport, and disposal of wastes). |

| 6 | Coastal Zone Management Act (CZMA) | Develop and implement coastal zone management plans. |

| Parameter | Level 1 Soil Reference Value (SRV) (mg/kg, Dry Weight) | Level 2 Soil Reference Value (SRV) (mg/kg, Dry Weight) |

|---|---|---|

| Inorganic Metals | ||

| Arsenic | 9 | 20 |

| Cadmium | 25 | 200 |

| Chromium III | 44,000 | 100,000 |

| Chromium VI | 87 | 650 |

| Copper | 100 | 9000 |

| Lead | 300 | 700 |

| Mercury | 0.5 | 1.5 |

| Nickel | 560 | 2500 |

| Selenium | 160 | 1300 |

| Zinc | 8700 | 75,000 |

| Barium | 1100 | 18,000 |

| Cyanide | 60 | 5000 |

| Manganese | 3600 | 8100 |

| Organics | ||

| PCBs (Total) | 1.2 | 8 |

| Aldrin | 1 | 2 |

| Chlordane | 13 | 74 |

| Endrin | 8 | 56 |

| Dieldrin | 0.8 | 2 |

| Heptachlor | 2 | 3.5 |

| Lindane (Gamma BHC) | 9 | 15 |

| DDT | 15 | 88 |

| DDD | 56 | 125 |

| DDE | 40 | 80 |

| Toxaphene | 13 | 28 |

| 2,3,7,8-dioxin, 2,3,7,8-furan and 15 2,3,7,8-substituted dioxin and furan congeners | 0.00002 | 0.000035 |

| Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) | ||

| Quinoline | 4 | 7 |

| Naphthalene | 10 | 28 |

| Pyrene | 890 | 5800 |

| Fluorene | 850 | 4120 |

| Acenaphthene | 1200 | 5260 |

| Anthracene | 7800 | 45,400 |

| Fluoranthene | 1080 | 6800 |

| Benzo (a)pyrene (BAP)/BAP equivalent | 2 | 3 |

| * Benzo (a) anthracene | * Dibenz (a,h) anthracene | * 3-Methylcholanthrene |

| * Benzo (b) fluoranthene | * 7H-Dibenzo (c,g) carbazole | * 5-Methylchrysene |

| * Benzo (j) fluoranthene | * Dibenzo (a,e) Pyrene | * 5-Nitroacenaphthene |

| * Benzo (k) fluoranthene | * Dibenzo (a,h) Pyrene | * 1-Nitropyrene |

| * Benzo (a) pyrene | * Dibenzo (a,i) Pyrene | * 6-Nitrochrysene |

| * Chrysene | * Dibenzo (a,l) Pyrene | * 2-Nitrofluorene |

| * Dibenz (a,j) acridine | * 1,6-Dinitropyrene | * 4-Nitropyrene |

| * Dibenz (a,h) acridine | * 1,8-Dinitropyrene | |

| * 7,12- Dimethylbenz[a]anthrancene | * Indeno (1,2, 3-cd) pyrene | |

| Sources | Replacement Description | Supplementary Material | Optimum Result | Treatment | Outcome | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Port of Barcelona | 0%, 15%, 25%, 35%, 50% | Rapid-hardening type II cement, plasticizer | 50% replacement | No pre-treatment | Greater compressive and flexural strength than the control mix. | [5] |

| Turkish ports/harbors | 0%, 25%, 50%, 75%, 100% | Superplasticizer | ≤50% for untreated DM, 100% for treated DM | Sieving Oven drying washing | Cl−1, , TDS, Cr, and Sb beyond the limits of Class III (Inert waste) landfilling criteria; hence, treatment is required. | [40] |

| China | Chloride content in DM ranges from 0 to 1.07%. | Fosroc polycarboxylates (superplasticizer) | Safe from corrosion if chloride content in DM is less than 0.18% and total chloride in concrete is <0.34%. | - | - | [56] |

| A-Kung-Diann Reservoir in southern Taiwan | 100% replacement of coarse and fine aggregate | Fly ash, slag, superplasticizer | Optimum strength and durability achieved at 0.28 w/b ratio. | Drying, sieving, sintering | Density of DM aggregate obtained is 800 kg/m3 and 1060 kg/m3. | [45] |

| Port of Bohai Bay in China | 1% fumed silica and 1% polypropylene fiber | Fumed silica, polypropylene fiber | 1% addition of fume gives the optimum result | No treatment | Granular modifier should be preferred over the fibrous modifier. | [57] |

| Kaohsiung Harbor, Taiwan | Mass ratio of dredged sediment(7–14), oxygen furnace slag (0–7) and glass waste (1) | Basic oxygen furnace slag, waste glass | Preheating at 500 °C and sintering at 1175 °C with sediment, oxygen furnace slag, and glass waste in the ratio of 10:4:1 | Preheating (400–700 °C), sintering (1125–1200 °C) | If water-soluble chloride content is large, then it may reduce concrete strength and corrode the reinforcement. | [9] |

| Dianchi Lake in China, | - | Lime, phosphogypsum, fly ash, water glass, organosilicon solution, white glue | DM (80%), cement (3%), lime (3%), phosphogypsum (3%), fly ash (5%), and water glass (6%). | Crushing, pelletizing | A stable shell layer was extremely required for concrete made with lightweight aggregate to prevent crushing. | [43] |

| France | - | Phosphoric acid | 14–17% shrinkage | Treated with phosphates and then calcination (1000 °C for 3 h) | Converting Pb, Cd, Zn, and Cu to insoluble metallic phosphates. | [51] |

| Sources | Replacement | Supplementary Material | Optimum Result | Tests | Treatment | Outcome | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brazilian seaports (seaport of Paranagua in Parana State, Brazil) | Up to 60% replacement | Construction and demolition debris (20–35%), lime production wastes (15–30%) | 15.4 MPa compressive strength (50% Dredged material, 20% construction and demolition waste, and 30% lime production waste) | XRD, XRF, SEM, EDS, AAS, and LAMMA analysis | - | Up to 60% can be used. | [41] |

| Coastal area in Hong Kong | 80–95% replacement | Recycled fine aggregate, ordinary Portland cement, recycled glass, recycled coarse aggregate | Fill materials, partition blocks, and paving blocks use 5–10%, 20%, and 30% binder | TGA, XRD, ANOVA | - | Overall benefit for paving blocks (292 USD per m3), fill material (236 USD per m3), and partition blocks (117 USD per m3). | [50] |

| Port of Antonina, Brazil | Overburden soil (40–60 wt%), dredging sludge sediments (20–40%), and lime production waste (15–30%). | Overburden soil, lime production waste | Blended material attained 11.4 MPa strength on the 28th day | XRD, XRF, AAS, SEM, EDS, DTA–DTG | Dried in a vacuum at 100 °C and milled | New composites can be made from three types of industrial waste material (overburdened clayey soil, dredged marine sludge, and lime production waste). | [48] |

| Harbor of Dunkirk, France | 12.5% and 20% | Admixture | Limited to 12.5% of the concrete mix to prevent external sulfate attack and frost action | UPVT, frequency shift, CT, TT, ME, MIP, alkali-aggregate reaction, Sulfate test, Freeze-thaw reaction | Stored for 3 years duration before using | Less than 12.5% was declared non-economical; 20% was shown to be the maximum limit. | [14] |

| Urban waters, Arnhem, Netherlands | Cement (0–15%) and quicklime (0.5–1%) | Cement and quicklime | 7% cement and 0.5% lime accelerate the ripening process 3 times and make DM a category 1 material (≤3 m) | LT, XRD, XRF, | Ripening process | With the addition of binder, the total time for ripening is reduced by 70%; highly contaminated DM can be used as category 2 building material. | [46] |

| Sources | Replacement /Addition | Supplementary Material | Optimum Result | Tests | Treatment | Outcome | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dunkirk Harbor in France | ROLAC®645 binder (6–8%) | Hydraulic binder ROLAC®645, fly ash | With an increase in binder content strength also increases | Modified Proctor compaction, UCS test, ME, CT, TT, I-CBR | Natural dewatering, sieving | Dredged material stabilized by a chemical binder can be used for subbase or base course material. | [66] |

| Harbor located in the South of France | Non-structural cemented mortar | Blast furnace slag, ordinary Portland cement | Processed sediments with 80 μm size, 80% replacement of slag with standard Portland cement | MIP, TGA/DSC tests, UCS test | Bioremediation, stored for 5 years in darkness at 4 °C, dried in a furnace at 45 °C | - | [62] |

| Eight French ports of the English channel | - | Quicklime, CEMII 32.5 | 3% of quicklime and 6% of cement CEMII 32.5 | Standard Proctor test | Grinding (under 2 mm), dehydration in the oven at 40 °C, sediments crushing | Sediments are fine materials with high organic matter and clay activity. | [68] |

| South end of Milwaukee Harbor in Wiscon-sin | 10, 20, and 30% FA and cured for 2 h, 7 days, and 28 days | Class C fly ash | 30% | UCS, CBR, AL, FT, Resilient Modulus Tests, Unconsolidated Undrained Strength Tests | - | Stabilization with Class C fly ash can significantly improve the engineering properties of DM. | [69] |

| East Port of Dunkirk Harbor in France | 0–30% binder | Cement, lime, Class-F fly ash. | Dredged soil mix with 9% cement | Water Immersion Ageing, FT, stress-strain curve, Swelling test | - | Class-F fly ash is incapable of improving the resistance to thawing-freezing and water immersion. | [67] |

| Dunkirk Harbor, North of France | - | 20% and 80% phosphoric acid | Both acids gave the same results | Specific surface area, density test, WA, organic Matter test, AL, XRD, pH, I-CBR | Novosol® process, calcination | 100% substitution after treatment. | [3] |

| Dunkirk Harbour, North of France | Replacing up to 60 fine sediment with dredged material | Cement and quicklime | Optimum result was obtained when adding both lime and cement | AL, CBR index, TT, ME, wetting and freezing cycles test, UCS, a Lime Fixation Point test | Decantation | Addition of lime with cement can change mechanical classification after 360 days. | [70] |

| Dunkirk marine dredged, France | 6% OPC or blended cement with limestone and slag | Limestone, slag, lime | Max dry unit wt. 2.04 g/cm3 Optimum water content is 11.6% | Modified Proctor tests, ME, TT | Dewatering, lime addition | Salinity of the sediments is equal to 31.4 g/L; 4.5% of organic matter. | [65] |

| Ansung, Jechon, and Mulwang Reservoirs in Korea. | Contents of heavy metals in dredged soil samples were lower than the environmental standards | XRD, XRF, heavy metal contamination, pH, electrical conductivity, wet sieve and hydrometer analysis, falling head permeability, CU triaxial compression tests | Air-dried in the laboratory at room temperature | pH value of the soil samples ranged from 4.25 to 5.39, and the electrical conductivity ranged between 83.3 and 265.0 mS/cm, indicating suitability for use as construction material with steel and concrete. | [37] | ||

| HuangBei Lake, China | Replace cement up to 100%. | Iron tailing slag, calcium carbide slag | When the ratio of DM, iron tailing slag, cement, and calcium carbide slag is 60:40:16:4 | UCS, slump, AL, test, XRF, XRD | Calcium carbide slag elevates the flowability. Solve the problem of subsidence. Calcium carbide slag is similar to hydraulic lime. | [44] | |

| Mouth of Neches River, Texas | Lime mixed at 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12% of dry weight of DM. Other additives (PC and FA) were mixed at 1.5, 3.0, 4.5, 6.0, and 7.5% of DM. | Quicklime, Hydrated lime, Portland cement, Class F fly ash | DM with 6% Portland Cement | UCS, ANOVA, chemical analysis | Cost-effective and environmentally friendly and reduces the overall use of cement products. | [49] | |

| Peoria Lakes Illinois River, USA | 20–100% replacement | Compost, Bio-solid, horse manure | 50% sediment and 50% bio-solid for Barley; 70% sediment and 30% bio-solid for Snapbean. | Water holding capacity, soil texture, pH, salt content, metal content | Sieving DM with a 10 mm sieve | Barley crops gave a good yield compared to snap beans. | [71] |

| Izmir Bay, Turkey | 5–20% mixing of each material (Lime, fly ash, and volcanic slag) separately in 4 types of dredged soil | Lime, Fly ash, and volcanic slag | Thermal power plant fly ash is the most effective additive | SEM, XRD, FTIR, AL, pH, specific gravity | Mixed dredged samples have better geotechnical properties and lower compression indexes than natural samples, except for volcanic slag. | [72] | |

| South Baltic Sea | Replace 100% stabilized natural soil | Geo-synthetic grid, | 1 year of dewatering | Hydraulic conductivity of about 5 × 10–6 m/s; turbulent and supercritical flow conditions showed a medium erosion resistance. | [73] |

| Sources | Types of Cement Replaced | Replacement Description | Supplementary Material | Optimum Result | Treatment | Outcome | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northern coast of Brittany, France | - | 8%, 16% and 33% of CEM I (52.5) | Limestone | 8% replacement with heating at 650 °C | Treated at high-temperatures (650 °C and 850 °C) to eliminate all organic compounds and activate the clay minerals; washing to remove chloride content | Hydration process required more time to complete; apparent porosity increased; at 33%, blended cement permeability decreased; strength decreased but within limits. | [52] |

| Ulu Pandan, Singapore. | Ordinary Portland cement | 30% cement replacement by marine clay or quartz | Quartz; CEM I (52.5) | 30% calcined dredged material at 700 °C | Drying for 72 h, ball mill grinding, calcination at namely 600 °C, 700 °C and 800 °C | Strength is reduced when replaced with dredged marine clay. | [58] |

| Port of Oran, Mediterranean Sea | Cement in mortar | DM replaces cement (5%,10%,15% and 20%) | 3% phosphoric acid by mass | 5% replacement (strength decreases as the DM increases) | Chemical treatments, leaching, dewatering, sieving (Φ ≤ 80 μ) | Polluted by both heavy metals and hydrocarbons; DS can be substituted partially for the cement used in the manufacture of cement. | [42] |

| Ruzin Reservoir in Slovakia | Portland cement | 40% sediment replaces cement with and without granulated NaOH milled for 3 min | Granulated NaOH | 20% and 40% lower compressive strength after 28 and 90 days, respectively. | Dry milling, milling with granulated NaOH | Strength of cement is reduced by adding dredged sediment. | [47] |

| Harbor of Napoli (South of Italy) | Fly ash | Fly ash, HNO3, HCl, HF, H3BO3 | 10% fly ash replaced by dredged material | Calcination at 550 °C for two hours | Reducing emissions by 80% compared to Portland cement. | [39] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Solanki, P.; Jain, B.; Hu, X.; Sancheti, G. A Review of Beneficial Use and Management of Dredged Material. Waste 2023, 1, 815-840. https://doi.org/10.3390/waste1030048

Solanki P, Jain B, Hu X, Sancheti G. A Review of Beneficial Use and Management of Dredged Material. Waste. 2023; 1(3):815-840. https://doi.org/10.3390/waste1030048

Chicago/Turabian StyleSolanki, Pranshoo, Bhupesh Jain, Xi Hu, and Gaurav Sancheti. 2023. "A Review of Beneficial Use and Management of Dredged Material" Waste 1, no. 3: 815-840. https://doi.org/10.3390/waste1030048

APA StyleSolanki, P., Jain, B., Hu, X., & Sancheti, G. (2023). A Review of Beneficial Use and Management of Dredged Material. Waste, 1(3), 815-840. https://doi.org/10.3390/waste1030048