Abstract

Orofacial myofunctional therapy (OMT) for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a promising, new treatment. We aimed to study patients’ experiences and adherence to OMT. Twelve patients with OSA were included in the study, and they engaged in OMT exercises three times daily for 12 weeks. Participants tracked their sleep and OMT exercise activities in an electronic diary. Exercise techniques were guided by a certified therapist. Patients’ experiences with OMT were assessed through semi-structured individual interviews conducted after a 12-week intervention, and the transcripts were analyzed using thematic analysis. The findings revealed an overarching theme that captured both facilitators of and barriers to OMT, organized into three subthemes: (1) motivation, (2) perceived support, and (3) perceived effects. Motivation was driven by a desire to improve general health and avoid continuous positive airway pressure treatment, and was supported by a sense of mastery and perceived effectiveness. Key facilitators included a trusting patient–therapist relationship, as well as developing routines and a sense of control. Barriers involved managing the comprehensive treatment protocol, insecurities around exercise execution and the potential impact of OMT, sickness burden, and previous negative healthcare experiences. These themes were supported by quantitative findings, which demonstrated high treatment adherence, while sleep data indicated modest individual improvements in subjective sleep quality and efficiency. By recognizing facilitators and barriers and addressing the individual differences among OSA patients, healthcare providers can better tailor their approach to meet diverse patient needs. This personalized approach, supported by emerging sleep improvements, may enhance patient engagement and improve adherence to OMT.

1. Introduction

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) affects nearly 1 billion people globally [1] and involves recurrent upper airway obstruction during sleep, leading to excessive daytime sleepiness, cognitive impairment, mental health issues, cardiovascular disease, and metabolic dysregulation [2]. Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy is considered the gold standard and effectively reduces apneic events and health risks [3], although long-term adherence remains a challenge [4,5]. Complementary, less efficient treatment modalities for OSA include lifestyle change [6], positional therapy [7], mandibular advancement devices (MAD) [8], and surgery [9]. Exploring alternative and adjunctive treatments is essential to address the varied needs of OSA patients [3].

Orofacial myofunctional therapy (OMT) is an emerging alternative treatment for OSA [6,10,11]. It focuses on exercises to strengthen pharyngeal, velar, tongue, and facial muscles to improve airway function and enhance nasal breathing, aiming to reduce apneic events and improve sleep quality [12,13]. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses indicate that OMT can reduce AHI and improve oxygen saturation levels, especially in cases of mild to moderate OSA [8,9,10]. Despite emerging evidence for the effect, we are not aware of any study of the OSA patients’ experience with OMT treatment.

This pilot study was conducted within the Sleep Revolution project, a Horizon 2020-funded initiative by the European Union that aims to transform the clinical management of sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) through innovative diagnostic tools and digital treatment strategies [14]. As a preparatory step toward a larger randomized controlled trial (RCT) evaluating the effect of OMT on OSA, this study was conducted to adjust and refine the design of the forthcoming RCT.

The aim of this study was to understand patients’ experiences and adherence to OMT.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Ethics

This mixed-methods study was designed to gain an in-depth understanding of patients’ experiences with OMT. We designed a qualitative study and used quantitative data on treatment adherence and self-reported sleep outcomes collected via a digital diary to complement our findings. The primary component was qualitative, based on individual semi-structured interviews following the completion of a 12-week OMT program. These interviews were conducted face-to-face by the first author, who also served as the participants’ OMT therapist.

To mitigate potential bias stemming from this dual role of therapist as interviewer, three measures were implemented. First, the interview guide (Appendix A) was developed collaboratively through an iterative process. An initial draft was prepared by the last author and subsequently reviewed and revised independently by all co-authors. The guide was then refined through a series of discussions, ensuring relevance with the study’s objectives. Our method followed the approach outlined by Brinkmann and Kvale [15] and was thoughtfully designed to include key themes, sub-questions, and open-ended prompts. The guide was tested with a convenience sample of seven volunteers. Their feedback was used to review and finalize the interview guide. Second, during the interviews, efforts were made to establish a safe and non-judgmental environment by emphasizing that both positive and negative feedback were equally valuable and appreciated. Third, the interpretation of the interview data followed a collaborative process by the author group to ensure a balanced and credible qualitative analysis.

In addition, baseline and post-intervention clinical assessments were conducted using standardized orofacial measurements. These were included for examiner training and calibration purposes in preparation for the forthcoming RCT, and results were not included in this study.

The study protocol was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics South East Norway (reference number: 377317) and adhered to Good Clinical Practice rules according to the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent.

2.2. Participants

Twelve motivated individuals who contacted the project leader following media coverage about the project were considered for participation. The inclusion criteria included (1) a verified OSA diagnosis according to the current International Classification of Sleep Disorders version 3 criteria [16,17], (2) written informed consent, (3) an age ≥ 18 years, (4) willingness to complete baseline and follow-up tests, (5) interest in trying OMT exercises, and (6) the ability to use and own a smartphone.

The exclusion criteria included (1) a BMI ≥ 40, (2) congenital craniofacial malformations, (3) active malignant disease, (4) blindness or hearing loss, (5) unstable cardiometabolic disease, (6) substance abuse, and (7) medical issues interfering with the study protocol, as judged by project leader.

Twelve participants were included in the study: eight females and four males aged between 37 and 68 years (median 59 years). Two participants withdrew shortly after the baseline evaluation due to low capacity to participate in the study. Most were employed full-time in high-responsibility roles, with four needing a varying degree of reduced workload due to long-term sick leave. All patients had tried CPAP treatment, but only six were CPAP-adherent. One participant was MAD non-adherent, and in addition, two of the participants used MAD devices but did not view this as a good treatment option. Participants’ BMI values ranged from 19.3 to 37.6 (median 27.4), and their AHI values varied from 6.9 to 81.4 (median 30.9). Participants reported sleep-related issues that had lasted from 1.5 to 31 years (median 10.8 years).

Participants exhibited a range of comorbidities in addition to OSA, including rheumatoid arthritis, Meniere’s disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, migraines, hypertension, gastroesophageal reflux disease, celiac disease, irritable bowel syndrome, hormonal disturbances, psoriasis, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, burnout, asthma, depression, allergies, and congenital heart disease. Participants’ characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participants’ characteristics.

2.3. Intervention

Participants engaged in a standardized OMT intervention package designed to address both the physical and behavioral aspects of OMT. The program featured a structured exercise regimen that consisted of a revised version of exercises described by Guimarães [12] that target the pharyngeal, soft palate, tongue, and facial muscles. These exercises were performed over a twelve-week period. The intervention also included self-monitoring through the use of a digital sleep diary [18] that incorporated an exercise log. By combining targeted OMT exercises, ongoing therapist support, and integrated self-monitoring, the intervention aimed to promote adherence and achieve the broader therapeutic goals of OMT, such as enhanced physical function and improved sleep health. This approach sought to assess the feasibility of implementing a structured and multifaceted program for patients undergoing OMT.

The therapist, who is a dentist by primary training and was certified as an orofacial myofunctional therapist by the Academy of Orofacial Myofunctional Therapy (AOMT), instructed participants in proper exercise techniques following the baseline evaluation. The OMT module included seven exercises: (1) brushing the tongue while holding it in different positions, (2) sliding the tongue against the hard palate behind the upper front teeth, (3) performing a tongue-to-palate vacuum hold, (4) pressing the back of the tongue down while touching the lower front teeth with the tip of the tongue, (5) raising the soft palate and uvula while saying “ah” both intermittently (“a-a-a”) and continuously (“aaa”), (6) blowing balloons or performing forced lip blowing, and (7) performing cheek resistance exercises. Participants performed these exercises at home three times daily for a total of 30–40 min per day over 12 weeks. Instructional videos describing the exercises were made by our research group and were provided through a YouTube link [19]. Telemedicine consultations were made available as needed over the 12-week period. Participants registered their sleep and exercise activity in an electronic diary. Follow-up video consultations with the OMT therapist, which lasted 15 to 54 min, provided support for continued training, with most consultations occurring every two to three weeks.

2.4. Materials and Measurements

Semi-structured interviews were conducted to explore participants’ experiences, including their thoughts on receiving a sleep apnea diagnosis, their perceptions of sleep before and after the intervention, their experiences with the OMT exercises, and the digital sleep diary. Additionally, we asked them about the role of their partners throughout the study, as well as participants’ interactions with healthcare professionals.

Quantitative data were collected via a digital sleep diary (Appendix B), which participants completed once daily throughout the 12-week intervention period. The digital sleep diary used in this study was adapted from the Consensus Sleep Diary [18]. The diary included a text box where participants recorded their OMT exercises to document adherence to the prescribed regimen of three sessions per day. Adherence was categorized based on the number of sessions completed: 0/3, 1/3, 2/3, or 3/3. Additional information was gathered through video consultations and interviews, when relevant.

The participants also registered their sleep in the diary, in which they calculated and reported total sleep time, sleep efficiency (SE), and sleep quality (SQ). SE was calculated as total sleep time divided by the duration of the sleep episode, following the method proposed by Reed and Sacco 2016 [20]. Participants’ perceived SQ was reported using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = very poor; 5 = very good). This sleep data was visualized in the diary.

Baseline and outcome assessments, using the Extended Orofacial Myofunctional Evaluation with Scores (OMES-E), the Iowa Oral Performance Instrument (IOPI), and the Tongue Range of Motion Ratio (TRMR), were conducted for therapist training purposes prior to the forthcoming RCT. Accordingly, data collected from these assessments were not included in the analysis of the present study.

2.5. Data Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using an inductive thematic approach described by Braun and Clarke [21]. The interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed using NVivo software version 14 by the first and second authors. The transcription process included repeated reading and comparison of the recordings to ensure accuracy, aligning with Braun and Clarke’s [21] recommendation of familiarization through immersion in the data (step 1).

The initial coding (step 2) began with all authors independently reading the transcripts to develop initial impressions. Preliminary codes were then suggested and discussed during group meetings until a consensus on codes and categories was reached. The first author refined and organized the codes based on these discussions, ensuring consistency and relevance to the data. Subthemes and overarching themes were identified through the combination and grouping of related codes (step 3).

Throughout the process, themes were continually refined by revisiting the transcripts and ensuring that there was sufficient supporting data for each theme. The authors collaborated to finalize the themes, creating a clear and comprehensive representation of the data through discussions and visual mapping of themes and subthemes (step 4).

The final themes were defined and named collectively and illustrated with direct quotes from the interviews (step 5). A selection of relevant literature was used as an interpretive base for the defined themes. Following this, the drafting of the article took place to document the findings and the systematic approach used throughout the study (step 6).

Exercise adherence was defined as the completion of more than 80% of the 252 planned exercise sets over the 12-week intervention period. Sleep diary data analysis began on the first Monday following each participant’s registration, marking the start of Week 1. From this point, data from the following 12 consecutive weeks were included in the analysis. Missing entries for the daily number of exercises were interpreted as the training not being performed, unless participants indicated otherwise during interviews or video consultations. If one or more diary entries were missing within a given week, the averages for SE and SQ were calculated based on the available entries.

3. Results

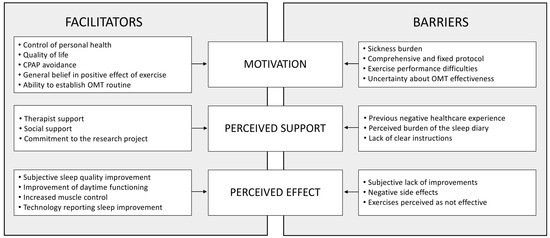

A total of 10 patients (P1–P10) were interviewed. Interviews lasted approximately 30–80 min. The analysis revealed an overarching theme centered on the barriers and facilitators influencing adherence to OMT, organized into three main themes: (1) motivation, (2) perceived support, and (3) perceived effect. This overarching theme captured participants’ experiences throughout the 12-week OMT program, shedding light on the complexity of the factors that impacted their commitment and engagement with the OMT intervention process. Detailed overview of facilitators and barriers to OMT is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Factors influencing adherence to orofacial myofunctional therapy. CPAP: Continuous airway pressure. OMT: Orofacial myofunctional therapy. The figure displays an overview of the overarching theme and subthemes developed in the thematic analysis.

3.1. Motivation Facilitators

3.1.1. Control of Personal Health

Ten out of ten patients expressed a strong desire to take control of their own health, which served as a central motivation for joining the study. As one participant stated:

“Give me something I can work on by myself. I’ll do anything… as long as I can influence it.”(P5)

For three patients, the limited availability of alternative treatment options further fueled participants’ interest in OMT. These participants aspired to achieve better sleep and enhanced daytime functioning, believing that this could reduce related health risks.

“I don’t mind snoring; that doesn’t bother me. But those breathing pauses—I definitely don’t want those.”(P6)

3.1.2. Quality of Life

While half of the patients reported a desire to actively improve their quality of life, all consistently described how sleep apnea had diminished their quality of life, citing challenges such as low energy, persistent daytime drowsiness, and poor overall sleep quality. Four participants highlighted the strain that sleep apnea had placed on their relationships, which often led to sleeping in separate rooms.

“This has done something with the nights. It has done something with my relationship… It has actually been very damaging.”(P1)

3.1.3. CPAP Avoidance

The avoidance of CPAP therapy emerged as a key motivator for adherence to OMT, driven by both physical and psychological challenges. All participants reported discomfort with CPAP, including mask irritation, stomach pain, and chest discomfort, making the therapy difficult to tolerate: “I’m constantly adjusting it, and either it’s too tight or too loose” (P2). All of the six participants who used CPAP in the project described CPAP as a “necessary inconvenience,” something they adapted to, but found far from ideal. For four patients, however, psychological barriers like panic and claustrophobia made CPAP completely unmanageable. As one participant explained,

“I didn’t try it any nights because I didn’t dare to lie down… I basically panicked just from thinking about having the mask on while lying down.”(P1)

3.1.4. General Belief in the Positive Effect of Exercise

Eight out of ten participants expressed a strong belief in the positive impact of exercise on their health, which influenced their engagement with the OMT program. As one participant noted,

“I exercise my body, I go for walks, and I do mouth exercises, because these three things are so important for me.”(P5)

Nine out of ten participants expressed a desire to continue their exercises beyond the project’s duration, despite variations in perceived effectiveness.

3.1.5. Ability to Establish OMT Routines

Six out of ten participants established routines to fit the time-consuming OMT exercises into their busy schedules. Most found specific times that “naturally fit,” emphasizing that without a routine, “You suddenly just drop out of it, forget it and then get distracted by something else” (P9). Three patients incorporated exercises into commutes, while two patients ensured that they completed sessions within a set timeframe to avoid feeling like they were exercising all day.

3.2. Motivation Barriers

3.2.1. Sickness Burden

Eight out of ten participants had comorbid illnesses, and six of them described how additional diagnoses exacerbated their overall sickness burden, complicating OMT and daily life. Comorbidities often hindered adherence to the OMT regimen. One patient described the following scenario:

“I had intense headache. I couldn’t handle light. I couldn’t handle sound… I was just in pain, nothing worked, and nothing helped.”(P1)

The two patients who did not have comorbid illnesses described their overall health as good.

3.2.2. Comprehensive and Fixed Protocol

Seven out of ten participants found the comprehensive and fixed OMT training protocol challenging, particularly the requirement to exercise three times a day. One patient shared,

“What I found most challenging was actually doing the exercises… Just getting them done three times a day, that has been very difficult for me.”(P2)

Key challenges included fitting the exercises into midday schedules and the mental burden of maintaining the regimen.

“It was mentally exhausting… it was tiresome to do, but also constantly feeling like: Now I have to do exercises, now I have to do exercises.”(P7)

3.2.3. Exercise Performance Difficulties

Half of the participants found three exercises—caves, soft palate lift, and tongue down—particularly difficult to master. One participant noted,

“I couldn’t do that [lifting soft palate exercise… That was the heaviest and most difficult one.”(P7)

Three patients also emphasized the importance of mental focus. This corresponded with the therapist’s observation that participants took several weeks to effectively master certain exercises, with some struggling throughout the 12-week program.

“During the first week the exercises were difficult… it was frustrating… I had to focus immensely to perform the exercises.”(P5)

3.2.4. Uncertainty About OMT Effectiveness

During interviews, one participant questioned the quality of the Guimarães study [12], expressing doubts about the reported adherence: “No way that they have exercised three times a day for 12 weeks” (P8). Two additional participants also expressed uncertainty about the effectiveness of OMT for others. Despite these doubts, there was curiosity and anticipation about the project’s potential outcomes.

3.3. Perceived Support Facilitators

3.3.1. Therapist Support

All participants experienced therapist support as a positive part of the process, valuing the opportunity to ask questions and receive clear answers.

“I feel like I can talk about all sorts of things. Also in a professional sense, you [the therapist] can answer so many questions about sleep apnea… I’ve really appreciated that.”(P2)

Video consultations were described as warm and inviting, and eight out of ten participants looked forward to these meetings. Half of the group highlighted their relationship with the therapist as a key motivator for performing the exercises.

“It turns into a conversation… it’s been really nice. And maybe that’s also made me more committed, you know, because you feel like you have a relationship.”(P5)

Five out of ten participants also emphasized the importance of consultation frequency, seeking enough contact for support but not so much that it became overwhelming. Additionally, two participants found that frequent consultations served as a helpful reminder to stay committed to the program. Lastly, four participants mentioned feeling a sense of obligation to the therapist, which further motivated their adherence to treatment.

“When I’m part of a project like this, I’d really like to see an effect, you know… and it’s partly out of respect for you.”(P4)

3.3.2. Social Support

Eight out of ten participants were in relationships, and all eight felt that their partners were positive about the intervention, although they mainly credited their commitment to their own motivation. One participant stated,

“He’s been involved, but not actively. This has to come from within myself… for my own benefit.”(P6)

Two of the partners had concerns about the general negative health effects of sleep apnea and motivated their spouses to seek medical treatment and commit to the OMT protocol. One of these eight participants expressed a desire for more support from their partner but admitted that they had not communicated this need clearly. Two participants also suggested that group-based OMT sessions could provide a valuable support system and motivation through shared experiences.

“I kind of wish there was a group where we could share experiences… When you’re in a group, you motivate each other… I think that would have been really, really useful.”(P10)

3.3.3. Commitment to the Research Project

For three patients, the fact that this process was part of a research project provided additional support. They felt that being part of a research project motivated them to adhere to the OMT regimen.

“I want to stick with the exercises because I’m involved in this study, and I want to see it through.”(P5)

These participants also expressed a desire to contribute positively to the study, and similar sentiments were observed by the therapist during video consultations.

3.4. Perceived Support Barriers

3.4.1. Previous Negative Healthcare Experience

Eight out of ten participants reported years of interaction with the healthcare system for sleep-related issues, often feeling abandoned, frustrated, and dissatisfied due to delayed diagnoses and inadequate treatment. Six of these eight patients also described a lack of trust in the system, with one participant stating,

“I’ve totally stopped going to the doctor… I don’t share anything because I don’t trust the system anymore.”(P5)

Despite this, these six participants trusted specific healthcare practitioners who provided thorough follow-up and demonstrated expertise.

“There’s a lot of variation in general practitioners … I don’t have very good experience [laughs]. I go there as rarely as I can, and when I leave, I regret that I went… A GP… is supposed to be a bit of an expert on everything, but at the same time maybe nothing [laughs]. I have much more trust in someone who has spent time specifically on one subject.”(P2)

The two participants who did not report negative experiences, both of whom had no additional health issues, described a high level of trust in the healthcare system.

3.4.2. Perceived Burden of the Sleep Diary

Nine out of ten participants recorded their sleep using the electronic diary, while one participant (P4) chose not to. All participants found the sleep diary more or less irrelevant, but two participants appreciated the initial sleep efficiency statistics. Five of the patients reported the sleep diary as a barrier to the intervention, three of whom emphasized that regular entries were disruptive and stressful.

“It became very tiring to have to register everything… I hardly had time to sleep when I had to register all the times I was awake… it became very stressful.”(P1)

The last two patients expressed frustration with unclear phrases and the rigid input system, especially the wake-up time limitations.

3.4.3. Lack of Clear Instructions

Patients received OMT guidance from the therapist, supported by video and written instructions. Two out of ten patients expressed confusion due to perceived discrepancies between the information provided by the videos and the written instructions. These patients expressed uncertainty about how to properly perform the exercises that needed to be addressed during video consultations.

“I couldn’t quite get the video and the descriptions to add up.”(P2)

3.5. Perceived Effect Facilitators

3.5.1. Subjective Sleep Quality Improvement

Eight out of ten participants reported fewer awakenings and improved sleep quality after 12 weeks of OMT training, with some even sleeping through the night. One participant shared, “I feel like I sleep more continuously… I feel that I sleep better” (P3). Two of these participants experienced such improvement that they discontinued CPAP use and sleep medication.

“Now I sleep through the night without waking up, and I don’t need to take Oxazepam. I have nights where I don’t use melatonin either, but rather drink milk with honey in it. I also don’t need to sleep in the middle of the day anymore… but I don’t know… it could be related to my sick leave.”(P8)

3.5.2. Improvements in Daytime Functioning

Seven out of ten patients reported feeling more energized, less tired, and better able to manage daily activities. One participant noted, “I am […] much more well-rested… I don’t pass out in the chair as much” (P4). Two patients also described improvements in general well-being and more effective rest.

3.5.3. Increased Muscle Control

Five out of ten participants noted increased muscle control and strength during the program.

“I have much better control over my tongue, and I control my muscles much better. And I feel the muscles better… I also think that they are much stronger now.”(P9)

This improvement encouraged continued adherence to the exercise regime. Three patients also reported general improvement in oral motor function.

“My motivation got better when the facial palsy [long time diagnosis] disappeared.”(P8)

3.5.4. Technology Reporting Sleep Improvement

Five of the ten participants reported increased motivation in response to objectively measured improvements captured by different technologies. These included the project-specific electronic sleep diary, medical treatment devices, such as CPAP (used independently of the study), and personally owned consumer technologies (e.g., snoring apps and Garmin watches), as illustrated by patient 5:

“It’s clear that I have had an improvement in the end of this [project] and that is a motivation… I actually haven’t had such low numbers [data from CPAP] since I got that machine.”(P5)

3.6. Perceived Effect Barriers

3.6.1. Subjective Lack of Improvements

Patients differentiated between a lack of improvement in daytime functioning and sleep. Eight out of ten experienced some improvements in at least one category. Two of these patients were uncertain whether these changes were related to OMT exercises.

“I’m sleeping well. How much this program has contributed to this change, I don’t really know. So, if it stays like this, I’ll be very happy, but from what I know about my illness, I think it will probably fluctuate.”(P5)

The remaining two participants, both of whom reported good sleep quality at baseline, perceived no changes following OMT. They attributed this to already functioning well and difficulties in recognizing subtle improvements, particularly in relation to their energy levels and daily functioning. Participants who reported fewer or no subjective improvements expressed the need for objective measurements to assess OMT effectiveness, while those with noticeable improvements relied more on personal experiences to sustain motivation.

3.6.2. Negative Side Effects

Six out of ten participants experienced no negative side effects during the 12-week OMT program.

“[When asked about negative side effects] No, no not at all [laughing].”(P4)

Three patients reported mild side effects, such as transient muscle soreness and tooth sensitivity. One patient with a history of headaches reported worsening symptoms after ten weeks, leading to discontinuation of the exercises.

3.6.3. Exercises Perceived as Not Effective

Therapist observations during video consultations revealed that most participants found certain exercises to be less effective, although only two out of ten patients mentioned this in interviews. Patients occasionally skipped or omitted the exercises they felt were ineffective. One patient shared their experience as follows:

“Blowing up a balloon was so easy that I felt it had no effect, or why am I doing this? So that it got a bit forgotten… and that tongue exercise was also so easy to perform that I didn’t feel it had any effect either.”(P7)

3.7. Distribution of Participants Across Identified Subthemes

To highlight reported responses, Table 2 provides a structured summary of the qualitative findings. The table shows the identified facilitators and barriers to OMT adherence, along with the number of participants who reported each subtheme.

Table 2.

Facilitators and barriers to orofacial myofunctional adherence: number of participants per subtheme.

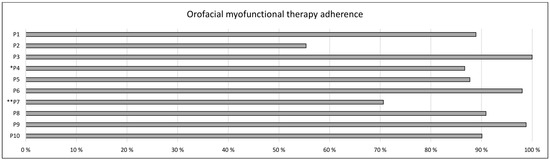

3.8. Exercise Adherence

Logs from the electronic sleep diary, supported by feedback from video consultations and interviews, showed that the majority of participants maintained high adherence to the OMT program.

Of the ten participants who completed the study, eight exceeded the defined 80% adherence threshold. Two participants were considered non-adherent: One participant (P7) discontinued OMT and stopped reporting after week 10 due to worsening of a pre-existing chronic headache, which the patient attributed to OMT. The other participant (P2) explained during video consultations that significant work-related stress made it difficult to consistently perform the exercises three times per day. Figure 2 illustrates the reported adherence to OMT.

Figure 2.

Adherence to orofacial myofunctional therapy (OMT) over 12 weeks. Each bar represents self-reported adherence as recorded in the digital sleep diary. P1–P10: Patients completing the project and interviews. * P4 did not use the sleep diary; adherence was estimated based on information provided during the interviews. ** P7 stopped OMT and sleep diary entries after week 10 due to side effects.

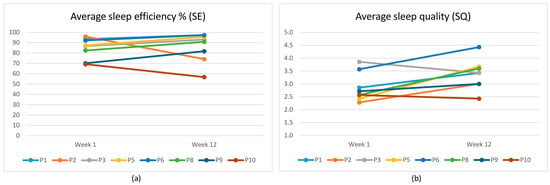

3.9. Sleep Efficiency and Sleep Quality

Seven of the eight exercise-adherent participants completed sleep diary registrations throughout the 12-week intervention period (P4 did not). Additionally, one exercise non-adherent participant (P2) provided complete sleep data. Based on calculated values from the sleep diary, six of the eight participants showed stable or slightly improved SE, while two exhibited a marked decrease. For SQ, the calculated scores indicated modest improvements in six participants, whereas two patients showed a decline. In total, three patients showed declines in SE, SQ, or both measures. Individual patient data are presented visually in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

P1–P10: Patients completing the project and interviews (P4 did not use the sleep diary, and P7 stopped using the diary during week 10). Self-reported sleep diary data has been calculated per week, comparing week 1 to week 12 after twelve weeks of orofacial myofunctional therapy. (a) Individual changes in average sleep efficiency (SE). Group average change from week 1 to week 12 for SE = 1.6% (standard deviation (SD) = 13.2%; range from −22.8% to 16.6%); (b) Individual changes in average sleep quality (SQ) (1 = very poor; 5 = very good). Group average change from week 1 to week 12 for SQ = 20.0% (SD = 20.0%; range from −11.1% to 51.0%).

4. Discussion

The aim of the study was to understand patients’ experiences and adherence to OMT.

Our main finding was that the overarching theme of facilitators and barriers to OMT adherence can be described according to the three main themes: motivation, perceived support, and perceived effect. Although patients receiving OMT were influenced by many of the same factors, there were marked individual differences in how these were interpreted, prioritized, and acted upon. In the following subsections, we discuss each of these themes in depth, highlighting commonalities, as well as differences in individual perspectives and experiences. The high level of OMT adherence observed among our participants provides a strong foundation, lending credibility and depth to the insights derived from their interview answers.

4.1. Motivation

Although this study did not employ a predefined theoretical framework, through our qualitative analysis, the Self-Determination Theory (SDT) emerged as a framework that can provide valuable insights into adherence to OMT. The SDT emphasizes autonomy, competence, and relatedness as critical drivers of intrinsic motivation [22], which may explain the participants’ ability to persist in this demanding intervention. We will illustrate how this framework guided our understanding of patient facilitators and barriers to adherence in this study.

Our participants described both intrinsic and extrinsic motivational factors that contributed to their decision to enroll in the study. Regaining control over their personal health was the clearest internal motivator, alongside a belief in the positive effects of general exercise. This fostered confidence in OMT’s potential effectiveness. For many of our patients, OMT represented not just a therapy to alleviate the OSA burden but also an empowering opportunity to take an active role in their treatment. This aligns with the SDT emphasis of autonomy [22], as they are driven by their belief in the therapy’s relevance to their personal health goals in choosing OMT as their preferred treatment option. Aversion to CPAP due to physical discomfort and psychological strain was identified as an external motivator that also contributed to OMT commitment. Many described CPAP avoidance as a powerful motivator to enroll in the study, that outweighed concerns about the effort required to complete the twelve-week structured exercise regimen. While extrinsic motivators like CPAP avoidance can be effective initially, SDT highlights the importance of fostering intrinsic motivation, such as a sense of competence and autonomy, to sustain long-term adherence [22]. Over time, CPAP avoidance may be replaced by a deeper sense of meaningful accomplishment as participants take active control of their OSA management.

Barriers to motivation were also evident, with the rigid and demanding nature of the OMT protocol emerging as the primary challenge. This was especially true for the patients who were managing comorbid illnesses or juggling already pressured daily routines. These findings emphasize the importance of tailoring interventions to accommodate individual health constraints and diverse schedules. In contrast, participants who successfully integrated the OMT program into their daily routines reported greater motivation and positivity and were more likely to continue exercising beyond the study period. The patients also reported that exercise-related insecurities added to the feeling of being overwhelmed during the first weeks, but that this feeling faded over time. According to the SDT, these barriers reflect the importance of fostering autonomy, building competence, and alleviating stress related to exercise performance to enhance adherence [23,24].

4.2. Perceived Support and Trust

We found that the concept of “perceived support” was closely linked to trust relationships, where trust toward the research project and the therapist was crucial. Trust was characterized by patients’ belief that the therapist administering the OMT intervention would act benevolently, honor commitments, and refrain from causing harm [25]. This trust allowed patients to entrust their health to the therapist, even without control over the therapist’s knowledge or motivation, regarding therapeutic recommendations [25,26,27]. Participants had to accept vulnerability, both in processing the overwhelming information about OMT and in navigating uncertainties due to limited research on this treatment. Interestingly, some patients viewed their participation in the research project as a positive motivator, driven by the opportunity to contribute to stronger evidence for the OSA patient community.

The therapist worked specifically to create a safe and positive environment, adapting the frequency and duration of telemedicine consultations to the participants’ needs. These meetings aimed to monitor OMT progress and address patients’ questions or concerns related to their OSA diagnosis. Participants also had email access to the therapist throughout the study. Our findings suggest that the patients’ perception of being supported during the intervention strongly influenced both their trust in the therapist and their ability to stay committed to the program. Particularly, the patient–therapist relationship was emphasized as a catalyst for sustained motivation. All patients described their therapist relationship as open and trusting. Skirbekk et al. [27] has described such relationships as characterized by mutual and open mandates of trust, where the therapist is perceived as both professional and relatable by the patient. Open mandates of trust are necessary for interventions and treatments where uncertainties are common. Preferences for therapist support varied; while some valued direct encouragement, others preferred knowing that support was available when needed [28].

While partner support was anticipated to affect adherence, it did not appear critical for this study group, likely due to their strong internal motivation. All partners played passive but positive roles, and any potentially negative attitudes from partners were hypothetical rather than observed. However, participants noted that social stigma from sleeping separately due to OSA symptoms and snoring motivated their pursuit of treatment. This stigma might have influenced their engagement with OMT, although partner perspectives on this issue were not explored. In the context of the SDT, a partner’s acceptance could significantly affect the sense of relatedness, which is an essential driver of motivation [28].

The primary barrier to perceived support stemmed from previous negative healthcare experiences, which had significantly undermined trust in the healthcare system and healthcare practitioners. The lack of trust in the relationship between an OMT therapist and a patient presented a risk that the patient would be unlikely to follow the advice given, and as a result would not adhere to treatment [27]. In our study, the necessary elements, described by Skirbekk et al. [27], to create an open trust relationship were observed in both evaluation consultations and video consultations. Many reported disappointments in accessing quality healthcare, and specific healthcare providers, often their GP, had failed to become an ally in their healthcare. Many participants reported long struggles with OSA symptoms and frustration with delays in receiving a diagnosis. Patients with negative experiences might be more reluctant and need more time before being able to give their therapist an open mandate of trust [27]. However, when these patients got to know the therapist, they reported appreciation for the open dialogue the most. One of the most crucial aspects of this dialogue was providing honest responses, whether answers to specific questions were available or not. Taking the time to follow up on unanswered questions and later updating the patient fostered a sense of being heard and valued, ultimately building a greater sense of trust. In the context of the SDT [29], we noticed that some of these patients described an increased need for autonomy to compensate for the lack of trust in medical decisions. This became apparent in some of our interviews when they stated that specific exercises that felt ineffective for them were omitted from their daily routine.

4.3. Perceived Effect

We expected the electronic diary to serve as a supportive motivational tool; however, all participants perceived it as irrelevant, and half even described it as bothersome or a source of stress. Although the diary has previously been used successfully in enhancing awareness and improving sleep quality in patients with insomnia [30], it was not interpreted as helpful for patients in our group, likely due to small nightly variations in sleep quality. However, the two patients with the greatest variation in sleep quality found it more beneficial. According to the SDT, the need for feedback on treatment effects is related to competence building, which helps sustain motivation. Our findings suggest that most participants valued some form of objective measurements, although preferences for specific tools varied.

Most participants reported subjective improvements in sleep quality and daytime functioning. These perceived benefits supported high adherence to OMT. However, a minority reported a lack of noticeable improvement. The group showed modest improvements in both SE and SQ. However, these trends were not consistent across all participants, underscoring variability in individual responses. All three patients who displayed worsening in SE or SQ reported unusual stress or illness, which could account for worsening sleep outcomes despite strong adherence in two of the three. While higher OMT adherence may have facilitated better sleep for this group, there are multiple complex factors that contribute to changes in perceived sleep quality.

Our findings are consistent with those reported in the existing literature [10], suggesting that OMT can positively influence subjective sleep. At the same time, the variability observed within the group highlights the importance of considering individual contexts and responses when evaluating the effectiveness of such interventions. Further exploration may help clarify the mechanisms behind these effects and shed light on factors that influence how different individuals respond to OMT in relation to sleep.

Improved muscle control, which was reported by half of the participants as the first notable change, suggests that OMT can enhance oral motor precision relatively fast, which in turn may motivate continued adherence to the program. A few participants also reported unexpected positive outcomes, such as enhanced facial appearance, which was regarded as a welcome effect, highlighting the potential impact of OMT exercises beyond their primary therapeutic goals.

We observed a greater motivation to continue OMT training after the project among participants who felt that the intervention had increased their competence by confirming the expectation of a positive OMT treatment effect. In contrast, those who remained uncertain about the benefits of OMT showed lower motivation to continue. Instead, they expressed a need to further build competence by continuing to evaluate their sleep in relation to whether or not they perform the exercises in the time ahead.

4.4. Instructions and Follow-Up

The OMT exercises used in the intervention were compiled to activate the stomatognathic muscles related to upper airway function [12]. The fact that all study participants needed some time to master the defined exercises illustrates a significant challenge in OMT, which is related to the fact that oral muscles in everyday life are mostly automatically rather than consciously controlled in functions like talking, eating, swallowing, and breathing. This automaticity means that most individuals have low proprioceptive awareness of their oral muscles, which can make it difficult to master new muscle patterns during therapy [31]. A few of our participants expressed that the video instructions that were available for home training were unclear, even if they had tested all exercises in a physical meeting with the therapist at the start of the intervention. According to the SDT, this kind of uncertainty would be a barrier that affects motivation negatively, as the sense of mastery and control is reduced [22]. Even if only a few patients mentioned this issue in their interviews, the therapist reported that all patients in the study had questions regarding correct muscle technique for several weeks during video consultations. It is unclear if this observation could indicate that more of the patients found the video instructions to be unclear at the start of the intervention, before the exercises were internalized. Another interpretation is that patients may require time to build the sensory awareness, muscle control, and strength necessary to accurately perform the exercises.

Although research on the adverse effects of OMT is limited, potential side effects may arise similarly to other muscle-training interventions [32]. This would, in our opinion, particularly be the case for individuals with pre-existing conditions that affect the head, neck, shoulder, or oropharyngeal muscles, or if harmful compensatory techniques or excessive exertion are used. In our study, one patient who had a history of long-lasting headaches reported exacerbation due to OMT. Even though the patient discontinued OMT, the patient expressed motivation to resume treatment with a modified program to avoid triggering these headaches.

The reported changes in sleep quality and daytime functioning following OMT show the variability in subjective experiences among participants. Most of our patients reported fewer awakenings and more continuous sleep, with some even discontinuing CPAP or medication use, suggesting significant therapeutic benefits for certain individuals. However, for a few, attributing unchanged symptoms to limited observational skills might reflect an effort to rationalize the experience, particularly among patients with minimal pre-treatment complaints who may struggle to notice changes when trying a new treatment. Interestingly, these patients expressed a stronger need for objective measurements to evaluate OMT effectiveness, pointing to the potential need for tools to better detect such changes. We also reflected on the possibility that this self-attribution could represent an attempt to protect the feelings of the interviewer, who also served as the therapist [33,34], and how the therapeutic relationship may influence patient-reported outcomes, consciously or subconsciously. From an SDT perspective, strong personal experiences can outweigh the need for objective medical assessment by building the necessary perceived competence to sustain motivation.

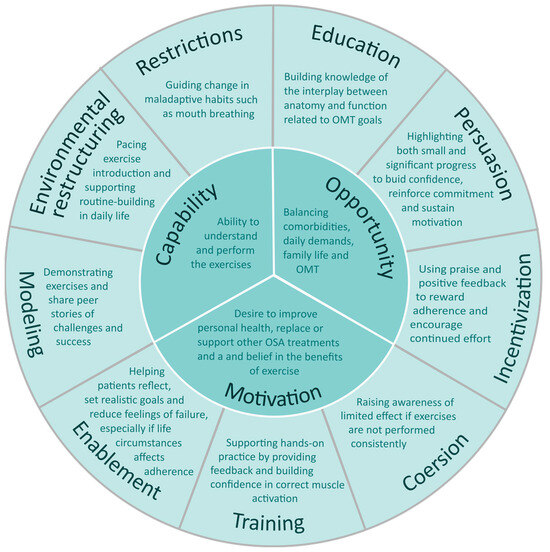

Our discussion has revolved around the foundational elements of motivation influencing OMT adherence, framed by the SDT [29]. Mutual trust in the patient–therapist relationship emerged as a potentially impactful facilitator to intervention compliance. The SDT, in combination with a practical tool like the “Behavior Change Wheel” (BCW), could support OMT therapists in creating structured personalized interventions by fostering long-term adherence through collaborative, patient-centered care. The BCW is designed as a wheel with three layers that focuses on core sources of behavior in the inner layer, intervention functions to facilitate behavior change in the middle layer, and overarching aspects of health care systems as the outer layer [35]. Although the BCW was not used to design the intervention, we see in hindsight that many of the therapist’s actions aligned with components from the model’s two inner layers: the core (capability, opportunity, and motivation as core drivers of behavior) and the associated intervention functions (such as education, training, enablement, and environmental restructuring). These components appear to capture important aspects of how the therapist’s actions may have supported the high adherence observed in our sample, where eight out of ten participants completed over 80% of the prescribed OMT program. The outer policy layer of the BCW was not relevant in this context, as OMT is not yet an established or system-level treatment for OSA. Figure 4 provides a summary of how the BCW framework may help structure and understand OMT-supportive strategies in clinical practice.

Figure 4.

Behavior Change Wheel adaptation to illustrate therapist strategies used to support orofacial myofunctional therapy (OMT) adherence in obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) patients. This figure highlights the inner two layers of the model: sources of behavior and intervention functions.

We also find that the concept of shared decision-making (SDM) could potentially be a valuable tool to further enhance intervention effectiveness. SDM empowers patients to actively participate in their treatment planning, aligning therapeutic goals with their personal values, preferences, and life circumstances [36]. In the context of OSA treatment, first-line options like CPAP and MAD require substantial adaptation and consistent use, with significant variation in patient satisfaction and adherence [37]. By incorporating SDM, therapists can work with patients to evaluate these treatment options alongside OMT, fostering realistic expectations and tailored strategies that better address individual needs. This collaborative process ensures that patients are supported not only in selecting a treatment that aligns with their preferences but also in managing the challenges inherent to any intervention, ultimately promoting adherence and long-term health outcomes [38].

4.5. Clinical Implications

The variability in symptoms and adherence capacity among OSA patients suggests tailored intervention strategies. While our participants met the program’s demands, individuals with more severe symptoms or lower motivation may struggle, emphasizing the importance of accessible and supportive therapy designs. Our findings highlight the pivotal role of the therapist, emphasizing the need for personalized, empathetic, and adaptable approaches in clinical practice to better support patients and enhance intervention success. Interviews further revealed the interplay between patients’ unique conditions and the therapist’s influence in shaping the intervention process. Despite high motivation, several participants required more support than we anticipated. We found no previous research on patient experiences or the therapist’s role in OMT interventions. Given the complexity of the physical and behavioral factors affecting adherence to OMT that were revealed in our study, we recommend that future OMT treatment programs consider using the BCW framework to assist in intervention design. The BCW offers a comprehensive approach to identifying key drivers of behavior and guides the selection of effective strategies to support patients, making it well-suited to address the multifaceted challenges of OMT adherence [35]. We view the BCW, the SDT, and SDM as complementary, and when used together, these theories can provide a cohesive and comprehensive approach to designing patient-centered OMT interventions that can improve accessibility, adherence, and outcomes across diverse OSA populations.

4.6. Strengths and Limitations

This study demonstrated high adherence to a rigorous OMT protocol among a highly motivated group, showcasing the feasibility of this intervention. This study also benefited from a rich qualitative analysis, with multiple authors revisiting the data over time to enhance the robustness of the findings. Moreover, integrating both patient and therapist perspectives offered valuable insights into the dynamics of adherence and intervention processes.

However, the study has notable limitations. Our participant group is small, and compared to the broader OSA population, it exhibited a large proportion of females. Our goal in the recruitment of patients was an even distribution of genders, but we found that fewer males were motivated to participate. Our study group was highly motivated for OMT training, either due to a lack of other treatment options or a desire to avoid CPAP treatment. This high motivation might not be representative of the average OSA patient. Six participants in this study were undergoing active CPAP treatment and reported fewer of the classical OSA symptoms [39,40]. The remaining four participants were CPAP-non-adherent and reported more of the expected symptoms.

The differences between our sample and a typical OSA population likely influenced their experiences and adherence to the intervention. For instance, their high motivation for OMT could stem from a strong desire to maintain or continue performing in high-responsibility jobs, reflecting a greater commitment to positive outcomes. However, despite their motivation, participants faced significant challenges associated with adhering to the demanding OMT protocol, reporting muscle soreness, difficulty maintaining focus, and the time commitment required for the exercises. These barriers, which are consistent with those found in other intensive interventions [41], may be even more pronounced for patients with lower motivation, greater symptom severity, or additional physical and psychological burdens [42]. It is our understanding that this adds to the importance of identifying patient-specific facilitators and barriers for each individual patient.

The dual role of the interviewer as therapist introduced a potential source of bias, possibly leading to an over-reporting of positive experiences due to social desirability. The interpretation of patient replies could also be filtered through the lens of the therapist’s understanding of the situation. To mitigate these risks, we used a semi-structured interview guide designed to avoid leading questions, fostered an open and trustful interview environment, and conducted the analysis collaboratively within the author group. During the analyses, we particularly searched for minority views that were negative toward the therapist [43]. While these measures reduced the potential for bias, we acknowledge that not all risks can be fully eliminated. Furthermore, the limited existing research on patient experiences and therapist roles in OMT interventions has restricted our ability to compare findings more broadly.

While comparing objective metrics, such as OSA severity measurements or anatomical features, would have provided valuable insights, it was not the focus of this study. Consequently, pre- and post-treatment polygraphies were not conducted. Although some objective measurements were collected, they primarily served as calibration tools to align assessments between the therapist and researcher in preparation for our upcoming RCT, where evaluating the effects of OMT will be the primary outcome. It remains uncertain whether including more objective measurements in this study would have influenced our findings. However, a comprehensive assessment of these factors was beyond the scope of this study. Future research, particularly the planned trial, will further explore the effects of OMT while incorporating more rigorous objective evaluations to address this gap.

5. Conclusions

This study provides new insight into how patients experience OMT during the treatment of OSA, as well as the facilitators and barriers that influence their adherence during 12 weeks of intervention. The main motivating factors were the desire to take control of personal health and improve quality of life. One of the most important motivating factors for CPAP users was the possibility of discontinuing CPAP therapy. The most significant barriers were the rigid structure of the 12-week OMT protocol, sickness burden, and previous negative healthcare experiences. Emerging subjective improvements in sleep quality and muscle control, which were supported by the relationship between the patient and the therapist, were especially important for sustained motivation.

Patients exhibited substantial variation in anatomical features, muscle function, personality traits, and life circumstances. While participants identified some common influencing factors to OMT adherence, there was significant variation in individual experiences and needs. We found that theoretical frameworks like the BCW, the SDT, and SDM could be useful tools for understanding the complex interplay of physical, psychological, and social factors in designing OMT interventions. By applying these frameworks, therapists can effectively identify patient-specific facilitators and barriers, address diverse needs, and provide tailored support to help patients succeed with OMT therapy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.D.H., X.F., T.D., H.H.-S. and H.S.; data curation, D.D.H. and U.T.; formal analysis, D.D.H., U.T., T.D. and H.S.; investigation, D.D.H. and X.F.; methodology, D.D.H., U.T., X.F., T.D., H.H.-S. and H.S.; project administration, T.D., H.H.-S. and H.S.; supervision, T.D., H.H.-S. and H.S.; visualization, D.D.H., U.T., T.D., H.H.-S., H.S.; writing—original draft preparation, D.D.H., U.T., T.D., H.H.-S. and H.S.; writing—review and editing, D.D.H., U.T., X.F., T.D., H.H.-S. and H.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement number 965417.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics South East Norway (reference number: 377317, approved 3 April 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Due to ethical reasons linked to patient privacy, the data presented in this study are only available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Academy of Orofacial Myofunctional Therapy for the training and guidance in the process of obtaining OMT certifications for the first and second authors. We would also like to acknowledge the valuable contributions of our colleagues in the Sleep Revolution project. In working with this manuscript, the authors used an artificial intelligence language model developed by OpenAI (ChatGPT 3.5 free version, June 2025 version) as a tool to improve readability and language. The authors have reviewed and edited the manuscript as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the published article.

Conflicts of Interest

H.H.S. reports grants from Innovative Health Initiative: Collaborator in the BEAMER project, Interreg ØKS: Collaborator in the InnoSleep project, and Eurostars: Collaborator in the Hypnos project, as well as honoraria from Lilly, Novo Nordisk, ResMed, and Phillips Respironics.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| OSA | Obstructive sleep apnea |

| CPAP | Continuous positive airway pressure |

| MAD | Mandibular advancement devices |

| OMT | Orofacial myofunctional therapy |

| SDB | Sleep-disordered breathing |

| AOMT | Academy of Orofacial Myofunctional Therapy |

| P1–P10 | Patients 1 to 10 |

| SDT | Self-Determination Theory |

| BCW | Behavior Change Wheel |

| SDM | Shared decision-making |

| RCT | Randomized controlled trial |

Appendix A

A.1. Interview Guide

[General Introduction] We need to learn more about what you know about sleep apnea and how you have experienced the treatment you have received. We are interested in your experiences. There are no right or wrong answers. This is important to help us offer the best possible treatment in the future.

- Background

- Gender

- Age

- Family

- Occupation

- Marital status

- How did you first hear about this project?

- How did you experience receiving the sleep apnea diagnosis?

- What was it like to start CPAP treatment?

- Are you aware of any health risks related to sleep apnea? Could you elaborate?

- Has this information affected your motivation to participate in this project?

- Tell us a bit about your sleep three months ago.

- What did you do on your own to improve your sleep before the project started?

- To what extent did your sleep problems affect your daily functioning?

- Have you thought about your breathing patterns?

- Tell us a bit about your sleep now.

- Has the OMT treatment contributed to any changes in your sleep?

- In what way has the OMT treatment improved or worsened your sleep?

- If you have noticed any changes in daily functioning, could you elaborate?

- Have you thought about your current breathing patterns?

- Tell us about the exercise routines.

- What was difficult, and what was easy?

- Did you complete all the exercises every time?

- What motivated you the most to keep performing the exercises?

- How has your motivation changed during the training period?

- What are your thoughts on continuing the exercises after the project?

- Tell us about your experiences with the sleep diary and tracking the exercises.

- Has the sleep and exercise diary contributed to changes in your sleep?

- What was most useful?

- What were the disadvantages?

- How often did you fill out the sleep diary and record your exercises?

- How much time did it take to log the information?

- Is there anything you feel is missing in the sleep diary?

- Did you keep track of your sleep before the project?

- [Only if the participant has a partner] Describe your partner’s role in the treatment over these 12 weeks.

- Can you describe if and how your partner supported you during this project?

- Could your partner have supported or motivated you more?

- Would you have liked your partner to have received information about the OMT treatment from us before the project began?

- If yes, how would you have preferred this information to be shared?

- Tell us about your encounters with healthcare personnel.

- How did you experience the first meeting with the OMT therapist?

- Can you think of anything that was missing or should have been explained during that meeting?

- How did you experience the video consultations with the OMT therapist?

- What were the pros and cons of those meetings?

- How would you describe your collaboration with the OMT therapist regarding the treatment? Is there anything that could have been different?

- Do you have any thoughts on how sleep guidance could have been provided before, during, or after the project?

- Have you used any other sources of information about OSA and sleep during the project?

- Let us shift slightly and ask a few questions about general health: Who or what do you trust most when it comes to health information?

- Why?

- Back to the project: How has it been to participate in the project?

- Is there anything important you would like to add that we have not asked about?

Appendix B

B.1. Sleep Diary

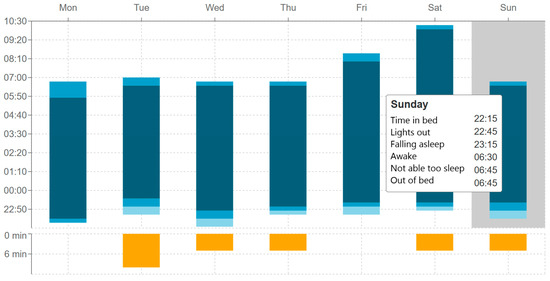

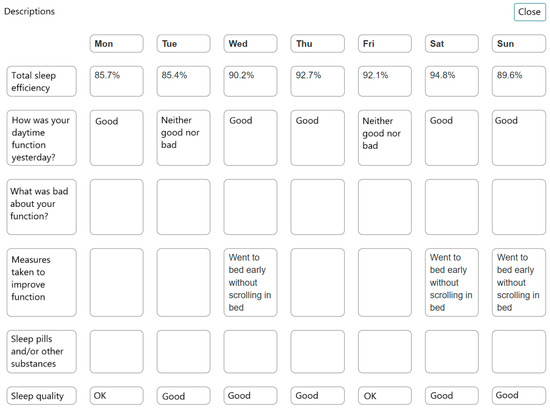

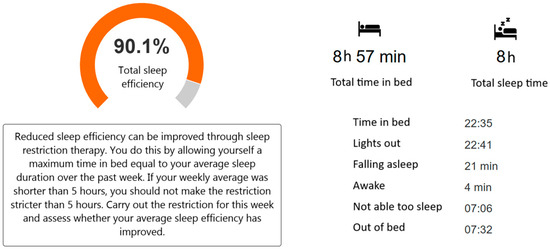

Figure A1.

Overview of one week of registrations by a test patient presented in the sleep diary. Each column represents one night. When the cursor is hovered over one column, the text box with sleep details appears. Yellow color represents time awake (minutes); light blue represents time between going to bed and trying to sleep; medium blue represents time from trying to sleep to falling asleep; dark blue represents duration of sleep.

Figure A2.

Overview of one week of test patient answers to sleep diary questions.

Figure A3.

Calculated average of sleep efficiency in %, total time in bed, and total sleep time for one week. The calculation of sleep efficiency requires a minimum of three entries per week.

References

- Benjafield, A.V.; Ayas, N.T.; Eastwood, P.R.; Heinzer, R.; Ip, M.S.M.; Morrell, M.J.; Nunez, C.M.; Patel, S.R.; Penzel, T.; Pepin, J.L.; et al. Estimation of the global prevalence and burden of obstructive sleep apnoea: A literature-based analysis. Lancet Respir. Med. 2019, 7, 687–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monahan, K.; Redline, S. Role of obstructive sleep apnea in cardiovascular disease. Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 2011, 26, 541–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spicuzza, L.; Caruso, D.; Di Maria, G. Obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome and its management. Ther. Adv. Chronic Dis. 2015, 6, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, T.E.; Grunstein, R.R. Adherence to continuous positive airway pressure therapy: The challenge to effective treatment. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2008, 5, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truby, H.; Edwards, B.A.; Day, K.; O’Driscoll, D.M.; Young, A.; Ghazi, L.; Bristow, C.; Roem, K.; Bonham, M.P.; Murgia, C.; et al. A 12-month weight loss intervention in adults with obstructive sleep apnoea: Is timing important? A step wedge randomised trial. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 76, 1762–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koka, V.; De Vito, A.; Roisman, G.; Petitjean, M.; Filograna Pignatelli, G.R.; Padovani, D.; Randerath, W. Orofacial Myofunctional Therapy in Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome: A Pathophysiological Perspective. Medicina 2021, 57, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilleminault, C.; Huang, Y.S.; Monteyrol, P.J.; Sato, R.; Quo, S.; Lin, C.H. Critical role of myofascial reeducation in pediatric sleep-disordered breathing. Sleep Med. 2013, 14, 518–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, M.; Certal, V.; Abdullatif, J.; Zaghi, S.; Ruoff, C.M.; Capasso, R.; Kushida, C.A. Myofunctional Therapy to Treat Obstructive Sleep Apnea: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Sleep 2015, 38, 669–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saba, E.S.; Kim, H.; Huynh, P.; Jiang, N. Orofacial Myofunctional Therapy for Obstructive Sleep Apnea: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Laryngoscope 2024, 134, 480–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueda, J.R.; Mugueta-Aguinaga, I.; Vilaro, J.; Rueda-Etxebarria, M. Myofunctional therapy (oropharyngeal exercises) for obstructive sleep apnoea. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 11, CD013449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Felicio, C.M.; de Oliveira, M.M.; da Silva, M.A. Effects of orofacial myofunctional therapy on temporomandibular disorders. Cranio 2010, 28, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guimaraes, K.C.; Drager, L.F.; Genta, P.R.; Marcondes, B.F.; Lorenzi-Filho, G. Effects of oropharyngeal exercises on patients with moderate obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2009, 179, 962–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakmakci, S.; Ozgen Alpaydin, A.; Ozalevli, S.; Oztura, I.; Itil, B.O. The effect of oropharyngeal exercise in patients with moderate and severe obstructive sleep apnea using CPAP: A randomized controlled study. Sleep Breath. 2022, 26, 567–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnardottir, E.S.; Islind, A.S.; Oskarsdottir, M.; Olafsdottir, K.A.; August, E.; Jonasdottir, L.; Hrubos-Strom, H.; Saavedra, J.M.; Grote, L.; Hedner, J.; et al. The Sleep Revolution project: The concept and objectives. J. Sleep Res. 2022, 31, e13630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkmann, S.; Kvale, S. InterViews: Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research Interviewing, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, R.B.; Brooks, R.; Gamaldo, C.E.; Harding, S.M.; Lloyd, R.M.; Quan, S.F.; Troester, M.M.; Vaughn, B.V. American Academy of Sleep Medicine. The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events: Rules, Terminology and Technical Specifications, Version 2.6; American Academy of Sleep Medicine: Darien, IL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sateia, M.J. (Ed.) International Classification of Sleep Disorders, 3rd ed.; American Academy of Sleep Medicine: Darien, IL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Carney, C.E.; Buysse, D.J.; Ancoli-Israel, S.; Edinger, J.D.; Krystal, A.D.; Lichstein, K.L.; Morin, C.M. The consensus sleep diary: Standardizing prospective sleep self-monitoring. Sleep 2012, 35, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orofacial Myofunctional Therapy. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLiwLLUadscDGs2dSzcXI6CEc-FItoXlPT (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Reed, D.L.; Sacco, W.P. Measuring Sleep Efficiency: What Should the Denominator Be? J. Clin. Sleep. Med. 2016, 12, 263–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, P.J.; Carraca, E.V.; Markland, D.; Silva, M.N.; Ryan, R.M. Exercise, physical activity, and self-determination theory: A systematic review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2012, 9, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyrlund, A.K.; Wininger, S.R. An Evaluation of Barrier Efficacy and Cognitive Evaluation Theory as Predictors of Exercise Attendance. J. Appl. Biobehav. Res. 2007, 11, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimen, H. Power, trust, and risk: Some reflections on an absent issue. Med. Anthropol. Q. 2009, 23, 16–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayer, R.C.; Davis, J.H.; Schoorman, F.D. An Integrative Model of Organizational Trust. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 709–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skirbekk, H.; Middelthon, A.L.; Hjortdahl, P.; Finset, A. Mandates of trust in the doctor-patient relationship. Qual. Health Res. 2011, 21, 1182–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadden, B.W.; Rodriguez, L.M.; Knee, C.R.; Porter, B. Relationship autonomy and support provision in romantic relationships. Motiv. Emot. 2014, 39, 359–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivations: Classic Definitions and New Directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 25, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorshov, T.C.; Overby, C.T.; Hansen, D.D.; Bong, W.K.; Skifjeld, K.; Hurlen, P.; Dammen, T.; Moen, A.; Hrubos-Strom, H. Experience with the use of a digital sleep diary in symptom management by individuals with insomnia -a pilot mixed method study. Sleep. Med. X 2023, 6, 100093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Kim, S.J. Orthodontics in Obstructive Sleep Apnea Patients; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Niemeijer, A.; Lund, H.; Stafne, S.N.; Ipsen, T.; Goldschmidt, C.L.; Jorgensen, C.T.; Juhl, C.B. Adverse events of exercise therapy in randomised controlled trials: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 1073–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giroldi, E.; Veldhuijzen, W.; Mannaerts, A.; van der Weijden, T.; Bareman, F.; van der Vleuten, C. “Doctor, please tell me it’s nothing serious”: An exploration of patients’ worrying and reassuring cognitions using stimulated recall interviews. BMC Fam. Pract. 2014, 15, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, M.J.; Simons, A.D.; Thase, M.E. Therapist Skill and Patient Variables in Homework Compliance: Controlling an Uncontrolled Variable in Cognitive Therapy Outcome Research. Cogn. Ther. Res. 1999, 23, 381–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michie, S.; van Stralen, M.M.; West, R. The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement. Sci. 2011, 6, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.N.S.; Todem, D.; Bottu, S.; Badr, M.S.; Olomu, A. Impact of patient and family engagement in improving continuous positive airway pressure adherence in patients with obstructive sleep apnea: A randomized controlled trial. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2022, 18, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pattipati, M.; Gudavalli, G.; Zin, M.; Dhulipalla, L.; Kolack, E.; Karki, M.; Devarakonda, P.K.; Yoe, L. Continuous Positive Airway Pressure vs Mandibular Advancement Devices in the Treatment of Obstructive Sleep Apnea: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cureus 2022, 14, e21759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, T.; Bakhit, M.; Michaleff, Z. Shared decision making and physical therapy: What, when, how, and why? Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2022, 26, 100382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krysta, K.; Bratek, A.; Zawada, K.; Stepanczak, R. Cognitive deficits in adults with obstructive sleep apnea compared to children and adolescents. J. Neural Transm. 2017, 124, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lal, C.; Weaver, T.E.; Bae, C.J.; Strohl, K.P. Excessive Daytime Sleepiness in Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Mechanisms and Clinical Management. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2021, 18, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodbridge, H.R.; Norton, C.; Jones, M.; Brett, S.J.; Alexander, C.M.; Gordon, A.C. Clinician and patient perspectives on the barriers and facilitators to physical rehabilitation in intensive care: A qualitative interview study. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e073061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMatteo, M.R.; Haskard, K.B.; Williams, S.L. Health beliefs, disease severity, and patient adherence: A meta-analysis. Med. Care 2007, 45, 521–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, D. Interpreting Qualitative Data; Sage publications: London, UK, 2024; 496p. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the International Association of Orofacial Myology (IAOM). Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).