Abstract

Background/Objectives: Tongue thrust (TT) occurs when abnormal tongue movements cause anterior tongue placement with pressure and contact against or between the teeth, potentially affecting the oral phase of swallowing, impacting eating, breathing and speaking. There is limited literature on the diagnostic and treatment approaches for TT, as well as involvement of health practitioners in its management. This study aims to examine the current knowledge and practices related to TT diagnosis and treatment among health professionals in Australia. Methods: A two-phase explanatory sequential mixed methods approach was adopted, comprising an online survey that collected participants’ demographic information and details on assessment, diagnosis, management, referral practices, and relevant experience and training. Phase one involved 47 health professionals from various disciplines in Australia who completed an online survey in its entirety. Phase two included in-depth interviews with seven speech-language pathologists (SLPs) to gain further insights into their experiences in managing TT. Survey data were analysed descriptively, and interview data was analysed thematically. Results: Most participants diagnosed TT using clinical assessments, such as general observation and oral motor examinations. Treatment approaches commonly included orofacial myofunctional therapy and the use of myofunctional devices. Interviews with SLPs identified four key themes: tongue thrust as a symptom rather than a diagnosis, facilitators to effective treatment, multidisciplinary approaches to management, and training and education gaps in clinical practice. Conclusions: This study provides valuable insights into how TT is identified, assessed, diagnosed, and managed by health professionals in Australia. It highlights the perspectives of SLPs on treatment approaches, as well as their views on the availability and adequacy of training and education in this field. The findings suggest the need for a broader understanding of TT management, emphasising the importance of multidisciplinary collaboration and professional development. These insights are globally relevant, as they stress the shared challenges and the value of international collaboration in improving TT diagnosis and treatment practices.

1. Introduction

Tongue thrust (TT) is defined as an atypical movement pattern that involves the individual placing the tongue against or between their teeth during swallowing and speech production [1]. TT can be categorised as one of the conditions that fall under the umbrella term of orofacial myofunctional disorders and is also referred to as a reversed swallow, anterior swallow, infantile swallowing pattern, deviated swallow, deviated deglutition, or abnormal swallow in the oral phase; it has been described as a type of swallowing pattern that infants use in the very early developmental stages of life [2]. Many of these terms are drawn from legacy descriptions and do not reflect current physiological understanding and contemporary perspectives. If the tongue function and infantile swallow pattern does not develop into a more mature swallow over time, it can turn into a persistent habit [2,3]. The tongue plays a vital role in several bodily functions, such as safe breathing, swallowing, chewing, and speech. Adults report that functional improvements in oral behaviours may contribute to perceived quality of life changes and improved quality of life [2,3,4,5,6]. Therefore, adverse effects associated with TT include dental deformities from the tongue consistently placing pressure on the teeth, breathing difficulties, anterior open bite and articulation inaccuracies.

The prevalence of TT varies by age and gender [7]. A study from India reported a prevalence rate of 4.9% in children aged six to ten years with TT, and this rate typically decreases between 10 and 12 years of age [7]. TT is most common in children aged eight to ten years old and is also more common in females compared to males [8]. TT can persist in later childhood, adolescence and adulthood; however, prevalence rates are lacking for older patients [9]. Overall, there is a significant lack in the literature surrounding the prevalence and developmental nature of TT, particularly in Australia.

Research suggests that there are multiple contributing factors to the aetiology of TT. Airway obstruction and habitual mouth breathing, enlarged tonsils, anterior malocclusion, marked lip movement during swallowing, and digit and dummy sucking have all been found to be associated with TT [10,11,12]. Referral to allergists and ENT specialists is recommended for patients with mouth breathing to assess for enlarged adenoids and other nasal or pharyngeal obstructions that may contribute to tongue thrusting. It remains unclear whether TT affects speech or if a speech or articulation impairment increases the likelihood of TT. However, individuals with TT often experience speech issues to some extent [11].

A multidisciplinary team is reported to be advantageous with assessment and differential diagnosis of TT due to the complex nature of diagnosis and contributing factors [13,14]. The practitioners typically involved in the diagnosis and treatment of TT or interdental tongue placement during the oral phase of swallowing includes dentists, orthodontists, SLPs, ear nose and throat specialists (ENT), orofacial myofunctional therapists, paediatricians and general practitioners [13,14,15,16]. Several methods for diagnosing and assessing the severity of TT have been reported; however, the literature is ambiguous around which methods are most efficacious. Ultrasound measures and devices or appliances, such as intraoral sensory instruments, have been reported as effective diagnostic methods [7,9,17,18,19,20,21,22]. Rating scales including the Expanded Orofacial Myofunctional Evaluation with Scores (OMES-E) Scale [23] and the Tongue Thrust Rating Scale (TTRS) [24] have also been highlighted as useful diagnostic tools for identifying the presence and severity of TT.

Whilst TT itself may not directly cause significant health complications, its persistence can contribute to functional issues; therefore, timely identification and intervention may help mitigate these outcomes, particularly when TT is part of a broader orofacial myofunctional disorder. However, it is important to note that successful treatment outcomes are also achievable in older children, adolescents, and adults. Research and clinical experience suggest that while early intervention may support developmental alignment and habit correction, therapy initiated at later stages can still be effective, especially when tailored to individual needs and motivation levels. Different treatment methods to remediate and/or minimise TT and related orofacial myofunctional disorders include orofacial myofunctional therapy (OMT), use of myofunctional devices [20] and orthodontic treatment including tongue cribs [20,25]. The aim of these treatment approaches is to improve oral functions and remediate the TT by correction or repositioning tongue placement during swallowing and speech production [26]. The use of appliances like tongue cribs in TT treatment remains controversial. The IAOM opposes such devices, noting they may disrupt oral rest posture and freeway space, potentially worsening TT [27]. Additionally, many clinicians question the effectiveness of removable myofunctional devices. Foundational research by Proffit suggests tongue pressure during function is insufficient to move teeth, highlighting the greater impact of anterior tongue rest posture on dentoalveolar changes [28]. It is important to distinguish between tongue thrust during function and anterior interdental tongue rest posture. Anterior interdental tongue rest posture is more strongly implicated in dentoalveolar changes due to prolonged, low-force pressure. While tongue thrust is often visible and more readily observed, it is the resting posture that can have more persistent effects on craniofacial development and malocclusion [29]. Additionally, aesthetic concerns, such as visible tongue positioning during speech or rest, may also motivate individuals or parents to seek treatment. Despite increasing clinical interest, there is still limited knowledge about other interventions used by health professionals managing TT in practice.

Health professionals involved in the assessment, differential diagnosis, and treatment of TT require a comprehensive understanding of TT to provide effective patient care [2]. For instance, if TT is not recognised as a contributing factor—or if an underlying orofacial myofunctional disorder is missed in a client with an articulation disorder—treatment outcomes may be suboptimal, as the root cause may not be adequately addressed [30]. There is a notable overlap in the scope of practice among orthodontists, SLPs, and ENTs in the identification and management of TT [15]. Additionally, a lack of consensus exists regarding the processes and methods used in TT management, highlighting a significant gap in the knowledge, education, and practices of health professionals managing TT in Australia.

- Aim

The aim of this study was to explore current approaches to TT assessment, diagnosis and treatment, experience and training by health professionals, particularly in SLPs managing TT in Australia.

- Objectives

To investigate the current practices of Australian health professionals with the identification, assessment, diagnosis and management of TT.

To explore Australian health professionals’ perceptions and experiences of training and education in TT management.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

This study incorporated a two-phase explanatory sequential mixed methods approach [31]. Phase one was an online survey, which included quantitative and qualitative components. The second qualitative phase, informed by phase one, involved online semi-structured interviews [32].

2.2. Participants

Phase One—Online Survey: Health practitioners based in Australia involved in the assessment, diagnosis and treatment of TT were eligible to participate in the online survey. This included SLPs, orthodontists, dentists and orofacial myofunctional therapists. A total of 58 participants commenced the online survey, but 11 health professionals did not complete the survey in its entirety, resulting in a sample of 47 participants who completed the survey in full. Results will be reported for the maximum sample sizes who completed each question in the survey

Phase Two—Clinician Interviews: A total of 17 SLPs who completed the survey expressed interest in participating in an online interview and were then invited to participate in an online interview. Seven responded to the invitation and participated in online interviews. Though our goal was to recruit 12 to 15 participants, consistent with recommendations for achieving thematic saturation in qualitative research [32], we were only able to secure seven interviews.

2.3. Materials

Phase One—Online Survey: Survey questions were developed to gather demographic information on participants and details on assessment, diagnosis, management, referral, experience and training in TT. Survey questions were entered into the Qualtrics online software to create and distribute the online surveys to participants.

Phase Two—Clinician Interviews: Interview questions were generated based on survey responses, to expand on survey answers and provide more in-depth explanations of SLPs experiences with TT. Data was coded using NVivo 15 software prior to analysis.

2.4. Procedures

Phase One—Online Survey: A recruitment flyer was prepared which included a link to an online survey in Qualtrics. The flyer was distributed to special interest groups on Facebook, which were identified as significant for targeting potential participants. Survey links were also disseminated via professional organisations including the Australian Association of Orofacial Myology, Australian Dental Association, Australian Society of Orthodontics and Speech Pathology Australia. Participants were advised to click ‘next’ if they consented to proceed to participate in the survey. This concluded the section of research that gathered data allowing the comparison of assessment and treatment methods between the different health professionals. At conclusion of the online survey, only SLPs were invited to provide contact details if they were interested in participating in a follow-up individual online interview. The online survey was open from February to April 2024.

Phase Two—Clinician interviews: Seventeen (17) SLPs provided contact details to participate in a follow-up interview. Since the research team consisted of SLPs, this discipline specific knowledge and experience was used by the SLP interviewers to gather more in-depth information regarding SLP management of TT. Consenting interview participants were emailed a participant information sheet to take part in an online interview and return an electronic consent form. They were then contacted by a member of the research team by email or phone to schedule a suitable interview date and time. No prior relationship was established between the interviewers and interviewees. Online interviews were conducted by two of the study supervisors who are highly experienced female SLPs with extensive knowledge and experience in TT assessment and management. The nature of the semi-structured interview guide was open-ended to reduce interviewer bias. These were pilot tested with the researchers prior to the interviews commencing. All interviews were video recorded with a backup audio recording on an iPhone and de-identified field notes were taken. No interviews were conducted more than once. The transcripts were then checked for accuracy and de-identified by the project team. Interview transcripts were emailed to each participant for cross-checking, and they were given the opportunity to make amendments, to which two of the seven participants made brief changes. Interview transcripts were then coded by four researchers using NVivo 15 software.

2.5. Data Analysis

Online survey responses were analysed to describe demographic information and data on knowledge and approaches to TT management. NVivo 15 was used to code the qualitative data from the clinician interviews, which highlighted the most frequently discussed topics across the interviews. Due to the nature of the semi-structured interviews, data was then analysed using Braun and Clarke’s six phases of reflexive thematic analysis, i.e., familiarising the data, generation of initial codes, searching for themes, review of themes, defining and naming themes and producing the report [33]. The research team met on several occasions to search, review, define and rename themes, which was accomplished by placing prevalent codes into tables, looking for similarities, differences and most significant areas among these, and defining/naming. Once themes were identified and defined, themes were organised with indicative quotes from participant transcripts.

2.6. Ethical Considerations

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Curtin University Human Research Ethics Committee prior to commencing the study (HRE2023-0225 on the 9 May 2023). All survey data was de-identified prior to analysis. Interview participants were identifiable and were provided with a participant number. All electronic documents and data with participant details were stored electronically in a password-protected folder on a secure network.

3. Results

3.1. Phase One—Online Survey

3.1.1. Participant Demographics

Table 1 presents the university qualifications and additional training of the 47 participants in this study. The majority of participants were located Western Australia (n = 22) followed by New South Wales (n = 11; 20%), and Queensland and Victoria, each contributing seven participants (13%).

Table 1.

University qualifications and other training of participants (n = 47).

3.1.2. Assessment and Diagnosis of Tongue Thrust

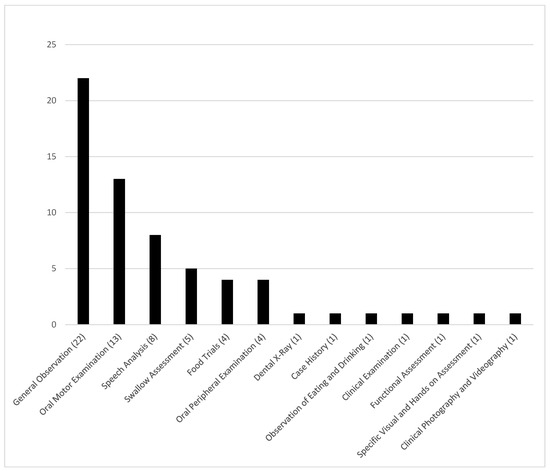

Clinical assessments were employed by 37 survey participants for a total of 63 responses to clinical assessments to evaluate and diagnose TT. The most frequently used clinical assessments were swallow assessments and observations, oral motor evaluations, speech observations and analyses, and observations of malocclusion or facial structure (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Clinical assessments used to diagnose and assess tongue thrust (n = 63).

Across 37 participants, a total of 59 types of clinical assessments were reported. Table 2 provides a breakdown by profession.

Table 2.

Total number of clinical assessments used to diagnose and assess tongue thrust by profession (n = 37).

The top three clinical assessments used by SLPs to assess TT were swallowing assessments and observations, oral motor evaluations and speech analysis and observation. The most frequently used clinical evaluations used by dentists and orthodontists were malocclusion and swallowing observations with one orthodontist reporting also using speech observations as evidence of TT. OMTs reported using mainly oral motor evaluations and swallowing observations in TT assessments.

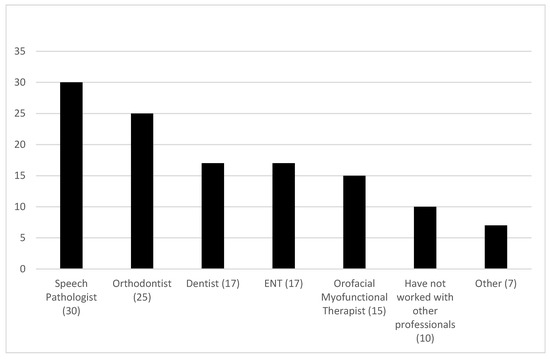

Collaboration with other health professionals regarding assessment and diagnosis of TT was reported by participants in the survey. Interdisciplinary liaising in TT management was prominent (n = 121) with participants collaborating with SLPs (23%), orthodontists (20%), dentists (13%), ENT’s (13%), and orofacial myofunctional therapists (12%). An additional 5% reported consulting with other professionals, including naturopaths, chiropractors, craniosacral therapists and osteopaths. While these professions may not have formal expertise in TT, their inclusion reflects participant-reported practices. Notably, 10 respondents—all of whom were SLPs—reported not collaborating with other professionals. This likely reflects their confidence and autonomy in diagnosing TT within their scope of practice (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Health professionals involved in diagnosing and assessing tongue thrust (n = 121).

3.1.3. Confidence in the Assessment and Diagnosis of Tongue Thrust

Participants rated their confidence in the assessment and diagnosis of TT on a scale from zero (not confident at all) to 10 (very confident). The overall average score was 7.81 (SD = 2.41). Orofacial myofunctional therapists (n = 3) had the highest confidence (M = 10, SD = 0), followed by orthodontics (n = 3) (M = 9, SD = 1). The average confidence scores of SLPs (n = 40) were 7.63 (SD = 2.34), followed by dentists (n = 4) with an average confidence of six (SD = 4). Two other health professionals, including an oral health therapist and dual qualified SLP and orofacial myofunctional therapist (n = 2) reported an average confidence of 8.5 (SD = 2.12).

3.1.4. Treatment of Tongue Thrust

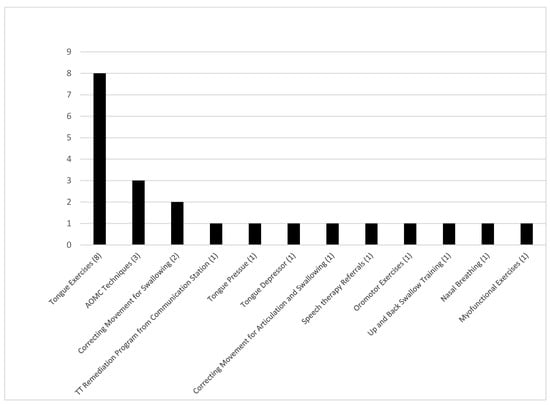

Participants (n = 39) reported three main treatment methods for TT, including orofacial myofunctional therapy (59%), myofunctional devices (20%), and orthodontic treatment (18%). One participant (3%) selected ‘other ‘and conducted tongue surgery. This is likely to be one of the dental practitioners surveyed. Of the eight participants who reported using myofunctional devices, eight used the MyoMunchee, one used Myospots and another a different band. Orthodontic treatment methods used (n = 7) included three reports of palate expansion, and one participant report each for fixed appliances, tongue crib brace, orthognathic surgery and stoma adhesives. Of participants who reported using OMT (n = 22), the most common (n = 8) was tongue exercises. Alternative OMT exercises are provided in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Orofacial myofunctional therapy methods used for treatment (n = 22).

Participants were asked to report how they measured the effectiveness of intervention with free text. Of the 40 participant who responded to this item, a total of 67 responses were reported and ranked from highest to lowest. Frequency reportedly used; observations (25%), assessment of current swallowing ability (21%), N/A or no method reported (16%), reassessment using same methods (13%), client/caregiver/stakeholder reports (9%), pre-treatment and post-treatment picture or video comparison (7%), accuracy of speech sounds in conversation (4%) comparison in efficacy of exercise performance pre-treatment and post-treatment (3%), and Payne paste (2%).

3.1.5. Education and Training in the Assessment and Treatment of Tongue Thrust

Participants (n = 21) reported their exposure to TT assessment and diagnosis whilst studying at university. Most reported no exposure (86%) at university and of three participants who reported exposure, one participant reported learning about clinical diagnosis and assessment (orthodontist), one within the university curriculum (SLP), and one from observations of the swallowing pattern (SLP).

Participants reported whether they had received further training to diagnose and assess TT (n = 54). Most received additional training (41%). Participants (n = 31) rated the level of adequacy of their further training from mostly and very adequate (46%), to mostly inadequate or not adequate at all (16%), with 19% reporting neutral responses.

Of the 47 participants, 51% reported having received further training to treat TT. Participants who had attended training (n = 24) reported attending formal training, (58%) informal training, (29%) or both informal and formal training (13%). Formal training (n = 23) included orofacial myofunctional therapy (87%), training in dental therapy (4%), research (4%) and training within an orthopaedic course (4%). Informal training (n = 15) included research (53%) and training from peers (47%).

SLPs (n = 46) reported whether they had received further training to diagnose and assess TT (n = 25). Other professionals including orthodontists, dentists, orofacial myofunctional therapists, dental therapists, dental hygienists, oral health therapists and orofacial myofunctional therapist/SLP (n = 14) also reported whether they had received further training to diagnose and assess TT (n = 7). Of the SLPs (n = 25) received formal training (n = 11), informal training (n = 5) or both formal and informal training (n = 8). One SLP gave no response on the type of further training they received. The most common further training for diagnosis and assessment methods among SLPs included partaking in orofacial myology courses (formal) (n = 17), reading literature/journal articles (informal) (n = 7) and mentoring/supervision (informal) (n = 4). Other professionals (n = 7) also reported receiving formal training (n = 4), informal training (n = 1) or both formal and informal training (n = 2). The most common further training method for TT diagnosis and assessment among other professionals included partaking in orofacial myofunctional therapy courses (both formal and informal) (n = 2).

SLPs (n = 46) reported whether they had received further training to treat TT (n = 18). Other professionals including orthodontists, dentists, orofacial myofunctional therapists, dental therapists, dental hygienists, oral health therapists and orofacial myofunctional therapist/SLP (n = 6) also reported whether they had received further training (n = 6). Of the SLPs (n =18) who reported receiving formal training (n = 10), informal training (n = 3) or both formal and informal training (n = 5). The most common further training methods for treatment of TT among SLPs also included partaking in orofacial myology courses (formal) (n = 11), reading literature/journal articles (informal) (n = 4) and mentoring/supervision (informal) (n = 3). Other professionals (n = 6) also reported receiving formal training (n = 4) or both formal and informal training (n = 2). The most common further training method for treatment of TT among other professionals included partaking in a variety of courses such as orthodontic and orthopaedic (formal) (n = 4).

Participants rated their level of adequacy of their further training in TT on a scale from zero (not adequate at all) to 10 (very adequate). The overall average adequacy rating was 7.71 (SD = 2.02). The single orthodontist and orofacial myofunctional therapist/SLP reported the highest adequacy of training with scores of 10, followed by orofacial myofunctional therapists (n = 2) and dental hygienists (n = 2) both with a score of 8.5 and standard deviations of 2.12. The average adequacy of training scores of SLPs (n = 24) was 7.42 (SD = 2.06), followed by a sole dentist (M = 7).

3.2. Phase Two—Clinician Interviews

Key themes were generated based on the 45-minute-long interviews with SLPs who shared their detailed experiences assessing, diagnosing and treating tongue thrust. The overarching themes generated were: (1) Tongue thrust is a symptom, not a diagnosis, (2) barriers to effective treatment, (3) multidisciplinary approaches to management, and (4) training and education gaps in clinical practice.

Table 3 provides details for the number of interviewees who referenced each theme and sub-theme, offering quantitative support for the thematic analysis presented in the manuscript.

Table 3.

Number of interviewees who mentioned each theme identified in the qualitative analysis (n = 7).

A detailed overview of the themes and sub-themes identified through thematic analysis, along with illustrative quotes from participants is outlined in Table 4.

Table 4.

Themes generated from interviews with speech-language pathologists on their experiences assessing, diagnosing and treating tongue thrust. (n = 7).

3.2.1. Tongue Thrust Is a Symptom, Not a Diagnosis

A common theme was that tongue thrust (TT) cannot be diagnosed alone, since it is usually an indicator of an underlying issue, with participants referring to it as a ‘symptom’ or ‘part of a bigger picture’.

“I think it’s really important to understand I see tongue thrust as a symptom, not a diagnosis.”P1

Participants explained the importance of considering the underlying issues when planning assessment and treatment, since treating a speech issue alone may be inefficient if the underlying cause, for example, low-lying tongue posture or limited tongue movement, is not addressed first within therapy.

Participants emphasised that it is critical to take a holistic approach to assessment and treatment, so that underlying problems can be prioritised and resolved rather than looking at only TT in isolation. Several participants shared similar opinions that TT should be viewed with equal importance as an orofacial myofunctional dysfunction as other areas of speech pathology due to the potential significant impacts if not addressed.

3.2.2. Facilitators to Effective Treatment

Participants discussed barriers and facilitators experienced when treating clients with tongue thrust, and how these restricted the capacity for the provision of effective management. Some participants reported that client attitudes impacted therapy, such as if a child is not engaged or motivated, they are unlikely to put the work in that is required to progress. One participant shared their experiences with a client who had previously received treatment when they were younger and later returned to resume therapy, motivated by external factors when they were at an older age (P1).

Another theme generated was finances as a barrier to effective treatment as some clients could not afford therapy. However, some participants reported providing pro-bono sessions to exceptionally motivated clients. The motivation and availability of parents or guardians to engage with treatment was also a barrier to effective therapy. As participants’ tongue thrust caseloads mainly consist of younger children, they report that it is critical for parents to have the capacity to prioritise therapy in order to see results for their child.

“When they go home, the parents are in charge of facilitating the practice and providing the feedback, so if the parents aren’t motivated to help the child, in that respect then it’s probably a later goal.”P3

Another recurring barrier reportedly experienced by participants was confidence levels and general support from other professionals. Participants discussed how having limited input or guidance from the multidisciplinary team (MDT) or professionals around them can hinder positive outcomes, whilst some expressed doubts with self-confidence.

“But I guess another barrier is my own confidence in doing the therapy, I’ve been doing it for ages, but I sometimes stop and I’m like ‘Is this actually working?’ because it’s really hard to see sometimes, I think sometimes I get those moments.”P3

3.2.3. Multidisciplinary Approaches to Management

Another theme across interviews was the importance of working in a multidisciplinary team, and the involvement of other health professionals, such as ENTs, dentists, orthodontists, GPs, paediatricians and the variation in management approaches.

Participants reported receiving referrals from other health professionals for issues such as speech and feeding difficulties. Participants also gave referrals to other health professionals for issues such as bite issues, snoring, tight muscles, breathing, tongue tie releases, and others. Other comments by participants involved the variation in management approaches between the multidisciplinary team, as well as between different SLPs. Participants reported that the difference in education and training is a possible link to the variation in management approaches, and the limited number of speech-language pathologists who look inside the mouth for a TT.

3.2.4. Training and Education Gaps in Clinical Practice

A recurring theme amongst participants was the significant lack of research, evidence and education in the management of TT. Participants commented on the strength in collaboration amongst health professionals, and different perspectives. One participant reported the benefit of living in a bigger city, and the availability of health professionals who specialise in TT.

There was a polarity of arguments, for and against OMT due to a perception of limited evidence in this area. Further research into the role of SLPs and the impact of orofacial myofunctional therapy on speech and feeding was suggested by all participants.

There was a sense of hesitation and fear by SLPs to talk about, or practice in orofacial myofunctional therapy, and more specifically, TT. Participants reported that the lack of research and the fierce controversy surrounding the functional impact of OMT made them hesitant to share their experiences with other health professionals and to advocate for therapy approaches in this area.

“I’m actually terrified at the thought of offering something more formal in terms of training because of that whole controversy and how firmly people who are not on the tongue thrust oromyofunctional train are not on it.”P7

Although therapies aligned with OMT for developing feeding and speech skills for underlying orofacial myofunctional disorders are within the scope of practice of SLPs, some practitioners reported lacking confidence to work in the area of TT to the limited education and evidence. Participants felt strongly about the need to include teaching of OMT in the undergraduate curriculum at university for Speech Pathology students.

“I think it’s really irresponsible, bordering on unethical, of us to be treating kids for years and years and years without actually looking at the full gamut of things that might be impacting that communication impairment. So yes, please, please get it in to the undergrad classes.”P7

4. Discussion

The current study was exploratory to investigate approaches to the assessment, diagnosis and management of TT in Australia, and health professionals’ perceptions and training experiences in TT. In the first phase, the key findings were that health professionals used a range of methods to assess, diagnose and treat TT and each possess a variety of training qualifications and experiences in the field. In the second phase (clinician interviews), four key themes were generated from interview data (1) Tongue thrust is a Symptom, not a Diagnosis, (2) Facilitators to Effective Treatment, (3) Multidisciplinary Approaches to Management, and (4) Training and Education Gaps in Clinical Practice. Each theme contributes to client-centred care in TT, highlighting that there are several factors influencing an individuals’ accessibility to assessment and treatment of their TT.

Effective approaches to assessing TT are an important consideration in this area. Across this study’s interviews, a range of assessment methods including oral motor examinations, speech analysis, observations of eating and drinking, swallowing during meals, speech during conversations, and oral structure and function (i.e., tongue movement and positioning of teeth) were reported to be used. An investigation of the literature shows that ultrasound [7,18,19,20] and TT rating scales [24,25] are used within TT assessment, which, as above, is contradictory with the most used assessment methods reported by Australian SLPs in the current study. This may be a geographical limitation due to a variety of research taking place in the United States, when the present study took place in Australia. Furthermore, this contradiction may support the theme that is present in existing research, suggesting that practitioners use a vast array of tools to assess their clients [21,34].

Participants in the online survey indicated OMT approaches to be commonly used for TT treatment, which aligns with previous literature [2]. Myofunctional devices and orthodontic treatment including tongue cribs are also reported and were discussed by several interview participants in the present study [21,27]. However, there is still limited research surrounding efficacy of assessment and treatment methods for TT. During interviews, participants were asked about barriers they experienced when managing TT so that factors impacting effective assessment and treatment could be identified and understood. The main barriers found in this study were financial burdens of the client, client motivation and engagement, parent engagement, confidence of the SLP, and clinical support from other health professionals. There is some existing literature further supporting this theme, although further investigation into this area from a broader range and larger number of professionals would be beneficial to increase both clinician and client awareness of challenges they may face when managing TT [21].

Working with other health professionals was reported to promote treatment efficacy for patients with TT. While there is insufficient research on the effects of multidisciplinary team approach on TT management, it is well-known that the collaboration of efforts from different professionals improves patient management, compared to global treatment delivered by a sole professional [35]. Maspero et al. [36] highlighted that orthodontic treatment alone is not sufficient to treat an atypical swallow, and a multidisciplinary approach such as orthodontic and myofunctional rehabilitation has the potential to lead to optimal long-term outcomes. The results from the survey and the interviews with professional practitioners support the notion that there is strength in collaboration.

A lack of knowledge and awareness in the management of TT eventually results in controversy and hesitation around the implementation of OMT for TT. Most participants in the current study did not have further training to diagnose and assess TT, and only some reported the adequacy of their training. Many clinicians may not be equipped with the training to confidently recognise a TT, which can impact on the efficacy of intervention provided to clients. This lack of definitive supporting evidence on the functional impact of OMT explains the polarity of views on OMT interventions between health care professionals and explains SLPs’ fears of practicing in OMT [37]. The scarcity of conclusive information on the efficacy of OMT in improving oral and tongue strength in patients with TT is noted both in the literature and within the current study [26,38]. While tongue strength alone may not be the sole determinant of functional outcomes, emerging research highlights the potential significance of orofacial myofunctional patterns—particularly tongue posture in relation to sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) in children. These findings suggest a need to consider a more comprehensive view of tongue function beyond isolated strength metrics. For example, Villa et al. [38] demonstrated that myofunctional therapy can reduce symptoms in children with SDB and improve measurable aspects of tongue function, such as strength, endurance and resting posture. Homem et al. [39] found there to be a significant lack of consistent scientific evidence demonstrating he efficacy of OMT on dentofacial and orofacial disorders, which impacts the treatment provided to clients, and the overall outcomes as a result. If the underlying issue of TT is left unrecognized, it may influence the efficacy or timing of other treatments, potentially delaying optimal outcomes. However, it is important to acknowledge that many individuals who begin treatment in later childhood, adolescence, or adulthood can still achieve successful results. Early identification may support more efficient care pathways, but positive outcomes are not limited to early intervention alone.

4.1. Clinical Implications

This study underscores the variability in management approaches among healthcare professionals assessing and treating clients with TT, identifying key barriers and highlighting the need for more standardised and enhanced education in this field. Given the limited existing literature, this study provides valuable data to support evidence-based practice, particularly for SLPs in Australia. However, discrepancies exist between the current literature and the real-world perspectives of professionals working in this area. The insights gained from this study—formulated from clinical perspectives—contribute to improved management outcomes for a diverse range of clients, including those with undiagnosed TT or related conditions.

The study’s findings are multifaceted, reflecting the diverse survey and interview responses from various professional groups with varying levels of experience. Notably, younger or less experienced professionals often differ in their approach compared to more experienced professionals. These differences are influenced by variations in education and training, which in turn affect clinical practice in the management of TT.

4.2. Limitations and Future Research

There are several acknowledged limitations with the present study, including a small sample size. While 58 participants commenced the online survey in phase one, only 47 completed the survey in its entirety, and seven participants were involved in the interviews during phase two. A larger sample size of 12 to 15 participants for the clinician interviews in phase two is necessary for increasing the depth of the results and allowing for improved generalisability [40,41]. Furthermore, interviewing health professionals beyond SLPs would have contributed to deeper insights and diverse perspectives, especially considering that one of the main themes found was ‘MDT approaches to management’. Strengths of the study included using a mixed-methods approach, allowing for quantitative and qualitative data to be integrated. This allowed for a comprehensive understanding of the topic from a range of health professionals as part of the online survey, and detailed exploration of perspectives and experiences from SLPs within clinician interviews. This enabled a thorough understanding as the survey results informed the interview questions. Furthermore, the diverse recruitment process through social media and professional bodies allowed for the targeting of a larger and wider audience involved in the field of TT.

The findings from the current study and existing literature highlight variability in the approaches of assessment and treatment Australian health professionals use to manage TT. The lack of comprehensive TT training for SLPs in Australia despite the identified clinical need to address TT in practice was an overwhelming finding in the study. This gap in research presents an opportunity for not only the role of SLPs in TT management to be explored, but also for other health professionals involved in TT. Future research should consider conducting interviews with all health professionals involved in TT, including internationally, so a deeper understanding of how disciplines differ in their approaches to TT management can be gained. Future research should also evaluate the effectiveness of commonly used OMT practices in SLP treatment and the alignment to clinical practice. This research will enhance the treatment provided to individuals experiencing TT and contribute to improvements in their quality of life.

5. Conclusions

This study describes the varied approaches to the management of tongue thrust among Australian health professionals, with a particular focus on the perspectives and practices of speech-language pathologists (SLPs). The themes generated provide valuable insights into the experiences of SLPs, highlighting key barriers to treatment such as limited efficacy data, the need for a broader clinical perspective on the underlying causes of TT, and the importance of an MDT involvement.

Importantly, the findings support a growing recognition that TT may not be a standalone diagnosis but rather a symptom of more complex orofacial and airway-related conditions, such as a potential clinical indicator of posterior airway obstruction or allergic responses, underscoring the need for timely referral to ENT or allergy specialists when appropriate.

A strong consensus among SLPs is that TT remains an area with limited awareness and education. This gap may serve as a catalyst for expanding education, training and research opportunities for both practicing and student SLPs, ultimately enhancing clinical confidence and patient care.

While this study focuses on the Australian context, the identified themes—barriers to treatment, the need for interdisciplinary collaboration, and the limited awareness surrounding TT—are likely relevant across global healthcare systems.

Future research could explore whether these challenges and perspectives are shared in other countries. Ultimately, this study’s findings may contribute to more comprehensive and effective global management strategies for TT, improving patient outcomes across diverse environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S., J.D. and K.M.; methodology, S.S., J.D., K.M., A.J. and H.N.; formal analysis, S.S., J.D., K.M., A.J. and H.N.; investigation, S.S., J.D., K.M., A.J. and H.N.; writing—original draft preparation, S.S., J.D., K.M., A.J. and H.N.; writing—review and editing, S.S., J.D., K.M., A.J. and H.N.; supervision, S.S., J.D. and K.M.; project administration, S.S., A.J. and H.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Curtin University Human Research Ethics Committee prior to commencing the study (HRE2023-0225 on the 9 May 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data sets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to ethics only being provided for this study.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge and thank Joanne McVeigh, Emily Nguyen, Chloe Yong, and Eliza Periera for their contributions to this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Singaraju, G.; Kumar, C. Tongue thrust habit—A review. Ann. Essences Dent. 2009, 1, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Shah, S.S.; Nankar, M.Y.; Bendgude, V.D.; Shetty, B.R. Orofacial myofunctional therapy in tongue thrust habit: A narrative review. Int. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2021, 14, 298–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, C.L.; Jost-Brinkmann, P.G.; Yoshida, N.; Miethke, R.R.; Lin, C.T. Differential diagnosis between infantile and mature swallowing with ultrasonography. Eur. J. Orthod. 2003, 25, 451–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lichnowska, A.; Kozakiewicz, M. Speech disorders in dysgnathic adult patients in the field of severity of primary dysfunction. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 12084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Lierde, K.M.; Luyten, A.; D’haeseleer, E.; Van Maele, G.E.; Becue, L.; Fonteyne, E.; Corthals, P.; De Pauw, G. Articulation and oromyofunctional behaviour in children seeking orthodontic treatment. Oral Dis. 2015, 21, 483–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordoni, B.; Morabito, B.; Mitrano, R.; Simonelli, M.; Toccafondi, A. The Anatomical Relationships of the Tongue with the Body System. Cureus 2018, 10, e3695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garde, J.B.; Suryavanshi, R.K.; Jawale, B.A.; Deshmukh, V.; Dadhe, D.P.; Suryavanshi, M.K. An epidemiological study to know the prevalence of deleterious oral habits among 6- to 12-year-old children. J. Int. Oral. Health 2014, 6, 39–43. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3959135/ (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Peng, C.L.; Jost-Brinkmann, P.G.; Yoshida, N.; Chou, H.H.; Lin, C.T. Comparison of tongue functions between mature and tongue-thrust swallowing—An ultrasound investigation. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2004, 125, 562–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eslamian, L.; Leilazpour, A.P. Tongue to palate contact during speech in subjects with and without a tongue thrust. Eur. J. Orthod. 2006, 28, 475–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priede, D.; Roze, B.; Parshutin, S.; Arkliņa, D.; Pircher, J.; Vaska, I.; Folkmanis, V.; Tzivian, L.; Henkuzena, I. Association between maloclussion and orofacial myofunctional disorders of pre-school children in Lativa. Orthod. Craniofac. Res. 2020, 23, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, M.L.; Cohen, M.S. Effects of form and function on swallowing and the developing dentition. Am. J. Orthod. 1973, 64, 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.P.; Utreja, A.; Chawla, H.S. Distribution of malocclusion types among thumb suckers seeking orthodontic treatment. J. Indian Soc. Pedod. Prev. Dent. 2008, 26, 114–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, C.K.; Burklow, K.A.; Santoro, K.; Kirby, E.; Mason, D.; Rudolf, C.D. An interdisciplinary team approach to the management of paediatric feeding and swallowing disorders. Child. Health Care 2001, 30, 201–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riensche, L.L.; Lang, K. Treatment of swallowing disorders through a multidisciplinary team approach. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2006, 8, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crysdale, W.S.; McCann, C.; Roske, L.; Joeseph, M.; Semenuk, D.; Chair, P. Saliva control issues in the neurologically challenged: A 30 year experience in team management. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2006, 70, 519–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerich, K.; Wojtaszek-Slominska, A. Clinical practice: Later orthodontic complications caused by risk factors observed in the early years of life. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2010, 169, 651–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuhrmann, R.; Diedrich, P. B-mode ultrasound scanning of the tongue during swallowing. Dentomaxillofac. Radiol. 1994, 23, 211–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, M.; Patil, S.D.; Kakanur, M.; More, S.; Kumar, S.; Thakur, R. Effects of habit-breaking appliances on tongue movements during deglutition in children with tongue thrust swallowing using ultrasonography—A pilot study. Contemp. Clin. Dentistry 2020, 11, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volk, J.; Kadivec, M.; Mušič, M.M.; Ovsenik, M. Three-dimensional ultrasound diagnostics of tongue posture in children with unilateral posterior crossbite. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2010, 138, 608–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shortland, H.A.L.; Webb, G.; Vertigan, A.E.; Hewat, S. Speech-language pathologists’ use of myofunctional devices in therapy programs: Perspectives of the ASHA special interest groups. Am. J. Speech Lan Pathol. 2022, 7, 2012–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, H.; Tomoto, K.; Kawase, G.; Iitani, K.; Toma, K.; Arakawa, T.; Mitsubayashi, K.; Moriyama, K. Real-time continuous monitoring of oral soft tissue pressure with a wireless mouthguard device for assessing tongue thrusting habits. Sensors 2023, 23, 5027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentim, A.F.; Furlan, R.M.M.M.; Perilo TVde, C.; Motta, A.R.; Casas EBde, L. Relationship between the individual’s perception of tongue position and measures of tongue force on teeth. CoDAS 2016, 28, 546–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Felício CMde Folha, G.A.; Ferreira, C.L.P.; Medeiros, A.P.M. Expanded protocol of orofacial myofunctional evaluation with scores: Validity and reliability. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2010, 74, 1230–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arslan, S.; Demir, N.; Karaduman, A.A. Reliability and validity of a tool to measure the severity of tongue thrust in children: The tongue thrust rating scale. J. Oral Rehabil. 2017, 44, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoor, Z.; Wadhawan, A.; Nagar, S.; Kumar, A.; Singh, M. A modified tongue crib appliance for correction of tongue thrusting. Cureus 2023, 15, e40518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mozzanica, F.; Pizzorni, N.; Scarponi, L.; Crimi, G.; Schindler, A. Impact of oral myofunctional therapy on orofacial myofunctional status and tongue strength in patients with tongue thrust. Folia Phoniatr. Logop. 2022, 73, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, R.M.; Franklin, H. Position Statement of the International Association of Orofacial Myology Regarding: Appliance Use for Oral Habit Patterns. Int. J. Orofac. Myol. Myofunc. Therapy 2009, 35, 74–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proffit, W.R. Muscle pressures and tooth position: A review of current research. Aust. Orthod. J. 1973, 3, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, K.N. The effect of dental and occlusal anomalies on articulation in individuals with cleft lip and/or cleft palate. Perspect. ASHA Spec. Interest. Groups 2020, 5, 1492–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, J. Effects of orofacial myofunctional therapy on speech intelligibility in individuals with persistent articulation impairments. Int. J. Orofac. Myol. 2003, 29, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, S.; Woodman, J. Using mixed methods in health research. JRSM Short Rep. 2013, 4, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guest, G.; Bunce, A.; Johnson, L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods 2006, 18, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limbrick, N.; McCormack, J.; McLeod, S. Designs and decisions: The creation of informal measures for assessing speech production in children. Int. J. Speech Lang. Pathol. 2013, 15, 296–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taberna, M.; Gil Moncayo, F.L.; Jané-Salas, E.; Antonio, M.; Arribas, L.; Vilajosana, E.; Peralvez Torres, E.; Mesía, R. The multidisciplinary team (MDT) approach and quality of care. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maspero, C.; Giannini, L.; Farronato, G. Atypical swallow: A review. Minerva Stomatol. 2014, 63, 217–227. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Cinzia-Maspero/publication/266325016_Atypical_swallowing_A_review/links/543f6ec70cf2e76f02245386/Atypical-swallowing-A-review.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Sackett, D.L.; Rosenberg, W.M.C.; Gray, J.A.M.; Haynes, R.B.; Richardson, W.S. Evidence based medicine: What it is and what it isn’t. Br. Med. J. 1996, 312, 71–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, M.P.; Evangelisti, M.; Martella, S.; Barreto, M.; Del Pozzo, M. Can myofunctional therapy increase tongue tone and reduce symptoms in children with sleep-disordered breathing? Sleep Breath. 2017, 21, 1025–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homem, M.A.; Vieira-Andrade, R.G.; Falci, S.G.M.; Ramos-Jorge, M.L.; Marques, L.S. Effectiveness of orofacial myofunctional therapy in orthodontic patients: A systematic review. Dent. Press J. Orthod. 2014, 19, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, C. Sample size and its importance in research. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 2020, 42, 102–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasileiou, K.; Barnett, J.; Thorpe, S.; Young, T. Characterising and justifying sample size sufficiency in interview-based studies: Systematic analysis of qualitative health research over a 15-year period. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the International Association of Orofacial Myology (IAOM). Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).