4.1. The State of Digital Financial Inclusion in Developing Economies

Digital transformation has resulted in changes in the financial services industry and enhanced access to the utilization of financial services because of rapid technical breakthroughs such as artificial intelligence, the internet, and cloud technology, among others. Sub-Saharan Africa’s developing financial industry, in collaboration with banks, governments, and other organizations, has established a digital payment ecosystem. The Ecocash system in Zimbabwe is used as an example by academics. A well-publicized success story, the network processed over USD 78.4 billion in 2019, increasing financial inclusion from 32 percent to almost 90 percent. As a result, financial, economic, and social inclusiveness have improved.

The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 increased the importance of innovation in financial services. First, limits on migration and the shutdown of bank offices in several countries underlined the necessity of digital payment services and electronic banking. Furthermore, many SMEs in poor nations continue to pay staff salaries with cash and checks. Nevertheless, e-wallets may readily be used for such reasons in order to assist the unbanked population, which is highly reliant on cash. In Jordan, for instance, the government suggested that citizens use digital wallets to pay their wages and make purchases. The Central Bank of Jordan (CBJ) has authorized seven different telecommunications and payment service companies to supply these wallets [

32]. To encourage digital payment service suppliers and retailers to embrace digital payments, the CBJ introduced Mobile Money for Resilience (MM4R) (COVID-19 Response Challenge Fund) (CBJ, 2020). One service provider in the nation reported a 300% rise in digital wallet account applications during the initial month of the crisis. These initiatives resulted in a considerable rise in transaction volume (over 36.5 million JOD), and the number of newly enrolled wallets exceeded 190,000 between the end of March and the end of April 2020. Additionally, the government said that roaming groups will be sent around the country to instruct individuals on how to use digital wallets, emphasizing the significance of financial literacy in deciding the viability of such operations.

An inclusive financial sector is seen as critical for the growth and development of economies in all nations throughout the world, as it facilitates access to, the availability of, and the use of financial services by all members of the population. Population groupings include the banked, underbanked, and financially excluded, as well as individuals of all genders. Sustainable Development Goal 5 (SDG5), which emphasizes the necessity of tackling gender equality, is made possible through financial inclusion. According to Ref. [

33], women and girls are still marginalized, defenseless, and disadvantaged. They are regarded as lacking economic, financial, and societal independence, indicating a gender discrepancy in African financial inclusion. Notwithstanding the fourth industrial revolution making advances in Africa, women are still struggling to attain digital financial inclusion in countries such as Kenya, Lesotho, Ghana, Namibia, South Africa, and Zimbabwe.

In the past few decades, African countries’ abilities to access monetary services have grown dramatically. Individuals and organizations are receiving a growing amount of financial services, notably credit. Modern technologies such as mobile currency have, however, contributed to improving the availability of financial services, including savings and remittance options. Nevertheless, until recently, very little was known concerning the banking industry’s reach—the extent to which vulnerable populations such as the poor, women, and young are barred from official banking firms in Africa and elsewhere. In recent years, technology improvements such as mobile money, innovation, and the development of new distribution channels such as “mobile branches” or banking services using third-party agents have played a significant role in increasing access to finance in Africa. Mobile money, for example, has had the most widespread success in Africa, where 14% of people reported using mobile money in the previous 12 months.

Although people who do not possess an official bank account may lack the assurance and trust that such a relationship provides, they regularly employ sophisticated strategies to control their everyday finances and make future plans. A growing number of Africans are resorting to new funding options readily accessible through mobile phone use. The fast growth of mobile money, commonly known as “branchless banking,” has allowed millions of people who are ordinarily prohibited from using mainstream banking applications to perform monetary transactions cheaply, safely, and reliably. In sub-Saharan Africa, 16% of individuals estimate utilizing mobile devices to pay invoices or send or receive funds across the preceding 12 months (in Africa, 14% of adults used digital payments in the prior 12 months), and about 44% of the adult population in the developing economy is unbanked [

34,

35]. In Kenya, where M-Pesa was initially commercially available in 2007, 68% of adults utilize digital payments. Likewise, in Sudan, mobile money is utilized by more than 50% of individuals, and over 35% of adults in East Africa indicate utilizing mobile money. North Africa is one of the regions with low mobile money use (with the exception of Algeria, where 44% of people report using a mobile device to pay expenses or send or receive money), which might be attributed to governmental restrictions put on mobile money carriers and banks. Adults use mobile money at a rate of barely 3%. In all other locations, the proportion of adults utilizing mobile money is a little less than 6% [

36].

In recent history, increasing digital banking services have caught the attention of various stakeholders (particularly politicians and scholars) as a method for achieving financial engagement. Particularly, digital payment channels, internet-enabled remittance service systems, and the use of smartphone technology have all made banking firms more accessible. The promotion and utilization of digital services may have an impact on and shape everyday financial activities, which may play a role in a society’s economic progress. Financial inclusion looks to be a potentially revolutionary force in many developing nations, with the ability to reduce poverty and provide a more financially inclusive society. Although financial inclusion is frequently seen as a critical component of development, Bangladesh continues to lag in ensuring financial institutions’ access to a broader environment. The World Bank Group (WBG) designated Bangladesh as one of twenty-five nations where 73% of the world’s economically disadvantaged people reside under the Universal Financial Access framework (UFA). A recent Financial Inclusion Insights (FII) study on Bangladesh found that 47% of the population is economically included via digital payments (17%), banking (5%), and non-bank financial firms (23%). It also found that fewer than one-third of women (32%), compared with 56% of men, have complete payment systems [

37].

Moreover, this country has witnessed significant development in the MFS market, accounting for more than 8% of all registered mobile money accounts worldwide. MFS has proven and revolutionized digital finance in Bangladesh, which is the eighth-largest payment country in the world. While all of these MFSs are supplied by private and commercial banks, the government has launched an effort called Nagad in collaboration with the Bangladesh Post Office to deliver digital financial services. Furthermore, MFS providers play a critical role in minimizing the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in Bangladesh. In April 2020, MFS operators opened approximately 0.3 million additional accounts to disperse the government’s catalyst package for export-oriented companies. From 20 March to 20 April 2020, 163,924 people gave more than TK 50 million to various charity organizations via bKash. The COVID-19 pandemic has necessitated the closure of countless smaller companies, causing unprecedented disturbance to young businesses, ranging from stores to road hawkers, who use MFSs for everyday transactions and transfer funds to support their loved ones, who reside in rural areas [

37].

In West Africa, very few countries (such as Nigeria and Ghana) have made significant progress in DFI. For instance, in Nigeria, the banked population increased steadily from 30 percent in 2010 to 32.5 percent, 36 percent, and 38.3 percent in 2012, 2014, and 2016. Between 2010 (6.3 percent) and 2016 (10.3 percent), the number of institutions, which includes microfinance banks, insurance firms, retirement funds, and related service providers, increased. However, the informal sector (NGOs and financial cooperatives) fell from 17.4 percent in 2010 to 9.8 percent in 2016. This demonstrated that, as anticipated by this strategy, more Nigerians are already accessing formal banking services [

38].

According to the ACI Worldwide Report (2022), in 2021, the Nigerian country reported 3.7 billion real-time transactions, placing it sixth in the world’s most advanced real-time financial markets, below India, China, Brazil, Thailand, and South Korea. The broad use of innovative digital and real-time payment technologies enabled Nigeria to generate an additional USD 3.2 billion worth of economic production in 2021 or 0.67% of the nation’s GDP. Real-time transactions are expected to reach 8.8 billion per year by 2026, representing an 18.6% 5-year compound annual growth rate (CAGR). This would generate an additional USD 6 billion in GDP in 2026, approximately 1.01% of the nation’s GDP, putting Nigeria in fourth place among the world’s nations reaping the full economic advantages of real-time transactions. Nigeria is quickly becoming a model for the effective digital transformation of the economic growth of the country throughout Africa. Nigerians are now expecting better speeds, more simplicity, and current thinking from financial institutions thanks to the COVID-19 epidemic. While cash is still commonly utilized, the trend toward digital and real-time financial transactions demonstrates government authorities’ achievement in supporting rapid development in digital transparency, especially transactions. Moreover, according to the 2020 Access to Financial Institutions in Nigeria Survey, half (45%) of Nigeria’s adult population uses banking institutions, while 33 percent uses informal banking services, including savings organizations, village organizations, and cooperatives. About 64.7% and 38.9% of people possess and utilize a mobile phone in Nigeria and Ghana, respectively.

According to Ref. [

39], given the challenges caused by COVID-19, this accelerated push toward the digitalization of the banking system may bring an unanticipated gain for digital banking inclusion. Digital banking (especially mobile money) has been demonstrated to be a critical component of financial inclusion in developing nations. Because of the outbreak, the quick surge in demand for fintech services by authorities, companies, and the general public is projected to enhance opportunities for digital channels to promote global financial inclusion. When provided responsibly and sustainably within a well-regulated framework, digital economic inclusion promotes growth and accelerates the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Nonetheless, the problem is that achieving the SDGs to eliminate penury throughout nations would require global effort and partnership, whether from developed or developing countries. Young people in industrialized nations have over 90% access to and use of critical financial products, including internet banking. Meanwhile, people who may have inadequate access to digital financial services, such as rural dwellers, the impoverished, and the elderly, will hinder progress toward digital financial inclusion and, as a result, may fall short of meeting the SDGs by 2030. Digital financial inclusion has the potential to be critical in minimizing the economic and social consequences of the current COVID-19 crisis. Increasing low-income households’ and small businesses’ financial access may also contribute to a more inclusive financial recovery. Such opportunities, therefore, ought to not be underestimated because the pandemic could exacerbate forgoing concerns about economic prohibition and introduce new hazards to the use of digital banking services.

Under the banner of “digital Bangladesh”, the government of Bangladesh (GoB) adopted digital policies such as native connectivity, human capital development, and the digitalization of public services. To speed the growth of electronic frameworks for the promotion of public and financial services, a variety of online enterprises have formed in collaboration with international aid operations (such as UNDP and USAID), governed by a public–private partnership (PPP) framework. One of the notable government projects to assure financial services is the Digital Financial Service (DFS) Lab+. DFS Lab+ is a cooperative project launched by Bangladesh Bank (BB), the country’s central bank, to create and increase digital financial inclusion. DFS Lab + provides various suggestions for digital financial inclusion, such as launching “rural e-commerce” projects, strategies for behavior modification conversations and financial literacy, and reforming legal and regulatory frameworks. There are over 57 financial institutions in the nation, with about 10,000 branches. However, because the majority of bank clients reside in cities, these banking systems are more valuable to people in cities than to individuals in rural regions. Mobile Financial Services (MFS) were developed in 2011 to guarantee that financial services reach the underprivileged in rural regions. Furthermore, the overall MFS market in Bangladesh was estimated to be worth BDT 15 billion, with bKash (owned by Brac Bank) holding 75% of the market share, followed by Rocket at 18% [

37].

It is hardly surprising that Kenya, where electronic banking initially gained traction, would have the highest score in contactless transactions. Kenya has begun the development of its second generation of official digital remittance standards, which builds on and aspires to expand the previous one. In 2014, new legislation encouraged interoperability and introduced a new type of digital operator to mobile networks. Both initiatives promote a more competitive industry in order to offset Safaricom’s market dominance with its MPesa mobile payment service. Kenya, on the other hand, performs poorly in terms of consumer protection, particularly market behavior regulation. It lacks specialized financial consumer rights legislation and regulation. However, authorities are striving to implement systematic interest rate disclosure standards that will allow customers to compare rates more readily across organizations.

The adoption of financial products revolves around time.

Figure 1 shows the adoption of financial products by country. The adoption of a payment product is described as the possession of a private transactional account in which users may save, receive, and utilize money (for example, preloaded cards, digital payment accounts, and current accounts). Payment use is separated into two categories: payment inflows and payment outflows. The utilization of inflows relates to the use of payment systems to receive wages, state assistance, and remittances in non-cash ways. The use of payment services for outflows relates to the use of payment services for cashless expenditures (e.g., retail purchases, bill payments) and cashless transfers.

Figure 1 shows that the performance of the developing economy is relatively low in terms of payment adoption, lending adoption, long-term adoption, and insurance adoption. This has implications for digital financial inclusion, especially for the unbanked. Payment product penetration outpaces other forms of product uptake in all nations, indicating that transactions are the best access point for promoting worldwide financial inclusion. For instance, many people in each of these nations only possess a payment product (for example, at least 40% of adults in Kenya and approximately 20% in the United States). Rising payment product acceptance promotes the acceptance of payment services as the initial financial instrument as product acceptance increases over time. Some nations with very minimal adoption rates, such as Peru, Colombia, and Bangladesh, have generated more headway in payments by offering a savings option via microfinance institutions (MFIs). However, even within these nations, the savings account is a fictitious payment instrument since it is often the sole account by which individuals save money and make regular withdrawals to make payments. Additionally, as these nations progress, they will be required to focus on actual payment solutions that permit non-cash payments, similar to other nations. While adopting a payment product is in the preliminary stage, some use is likely to follow. Obtaining the product is often motivated by a particular payment requirement (e.g., receiving a salary), and the consumer is likely to utilize the product to solve that need at the very least. A remittance product could also function as a gateway for users to embrace other items. Moreover, digital remittance transactions can reveal valuable information about consumers (for example, creditworthiness) and allow suppliers to offer additional goods. All those other items entail remittances and the utilization of effective digital payment channels in order to enhance economics both for customers and suppliers. A greater association between remittance product usage (acceptance) and lending, prolonged savings and investment, and insurance product uptake across the nations studied supports this view.

Four stages of financial inclusion progression based on adoption are documented in

Figure 2. Countries seem to move through four phases. Considering that remittances are the best way to get started with financial inclusion, the above four phases are defined by the extent of payment product usage. The first stage is the early days. This level marks the start of the process. The acceptance of remittance products is lower than 50% in all nations, while the consumption of other goods is often quite low (below 25%). Bangladesh, Peru, and Colombia are ahead of their rivals in terms of savings because of their MFI concentration. The second is transitioning—payment usage begins to break through at this level, with more than 50% perforation. In a number of countries, the use of one or even more products is gaining pace and starting to catch up to remittance adoption (for example, prolonged savings and investments in China and credit in Italy). The third phase is ready payments: at this level, remittance adoption has reached a crucial bulk adoption threshold (over 75%). Countries are anticipated to be prepared in terms of payments (for example, infrastructure) to permit elevated stages of certain additional items. Developed levels differ per product and, thus, are determined by the previous levels of consumption in thirty nations, which are described as more than 60% for loans, more than 70% for prolonged savings or investments, and more than 45% for insurance. This is normal performance, with loans progressing and investments and insurance reaching completion. The last and most advanced phase is as follows: remittance adoption is widespread at this point, and the consumption of all other items is likely to progress. Sweden, Germany, and Belgium exhibit this predictable behavior, whereas Singapore and Japan are extremely close. The United Kingdom is ahead in financing and prolonged savings and investments but behind in insurance. This might be because of market-specific variables, which should be looked into further.

Furthermore, the reason for adoption should be stated explicitly. Product implementation is a critical first step toward monetary incorporation, but usage and the extent of utilization are equally crucial. As previously specified, the utilization of remittance products can, however, help people adopt and use additional new products. Nevertheless, adoption does not necessarily result in utilization, and not every individual who owns a payment product uses it for capital flows. Usage must be actively promoted. In all nations studied, the adult population that utilizes a remittance product to receive anything of their capital flows is lower than the number of adults who own a remittance product. The disparity varies by country.

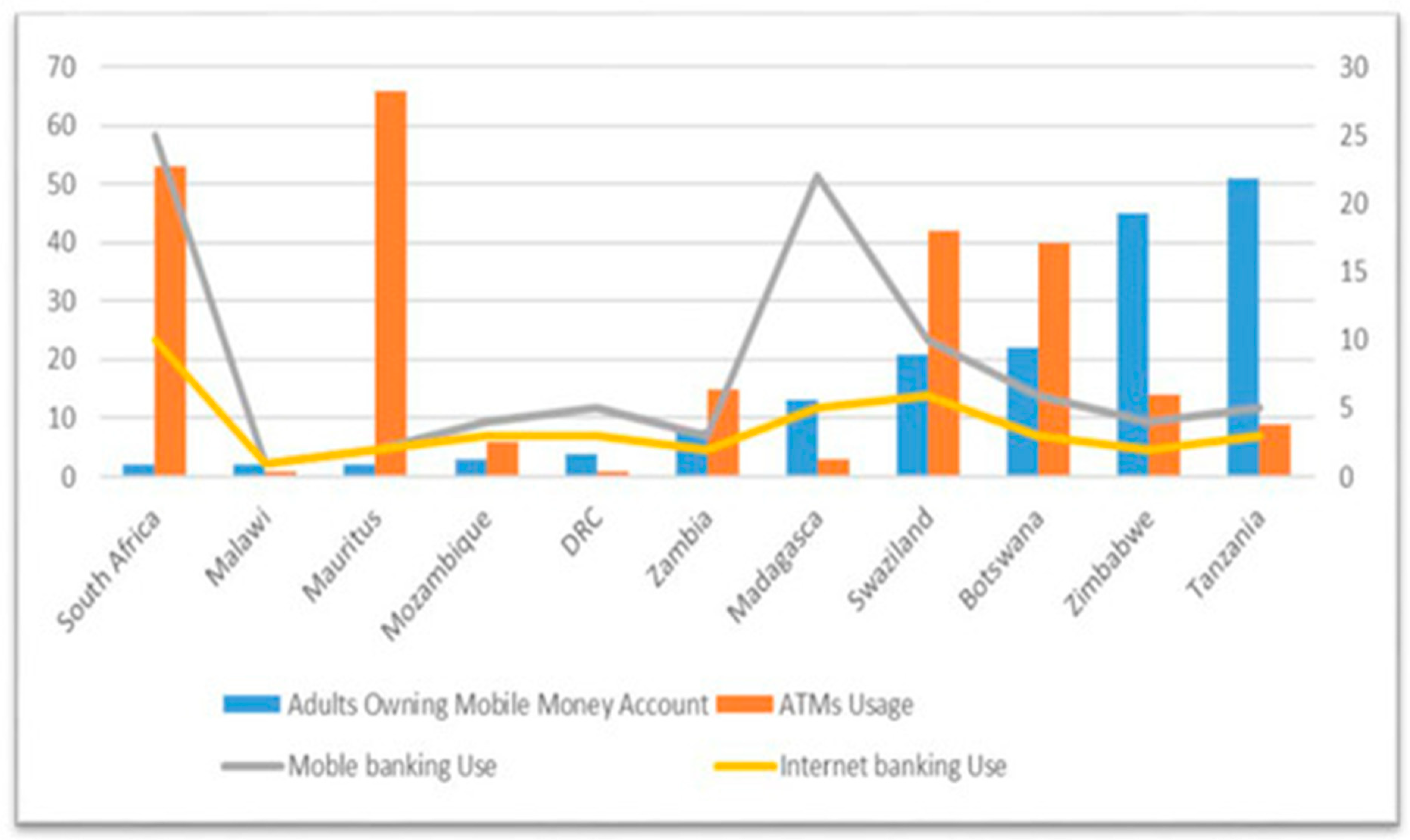

Figure 3 shows the proportion of adults owning mobile money accounts, ATM usage, mobile banking, and internet banking. The figure shows that Tanzania has the highest proportion of adults with accounts for mobile money (51% among the 11 SADC countries), followed by Zimbabwe (45%). Mauritius, South Africa, Malawi, Mozambique, Madagascar, the DRC, Swaziland, Zambia, and Botswana are the regions with the fewest people. Tanzania leads among these nations because 83% of its adult population who own smartphones have a mobile money account. This appears to indicate that the advancement of mobile money services necessitates both the progress of mobile telecommunication infrastructure and the availability of mobile money services. Digital financial technology has significant benefits. The advancement of automation has drastically altered the simplicity with which monetary services can be obtained. The introduction of automated teller machines (ATMs) has streamlined 24 h access to banking accounts, which has been extremely beneficial to consumers of financial products because clients continue to receive bank services after working hours when banks are closed. Furthermore, banks have launched banking applications and internet banking in order to further change how customers manage their bank accounts. Mobile and online banking is the next generation of ATMs because they allow customers to reach their financial transactions at any time and from any location, providing them with both time and place liberty. Moreover, with digital finance, the consumer can obtain banking services even without requiring a bank account. In what could be considered a search for even simpler and quicker forms of transaction, the smartphone has significantly reinvented the ecosystem of banking delivery services in Africa with a special niche that has tried to complement consumers’ preferences. As a result, when an innovative technology is introduced, it is critical to understand the level of customer satisfaction. In terms of consumer preference for utilizing Tanzanian mobile monetary services programs, 6 in 10 consumers were satisfied with electronic remittances in terms of cost, whereas around 4 in 10 customers found electronic remittance benefits to be overpriced or not delivering value for money [

40].

4.2. What Are the Challenges to the Inclusion of Digital Finance in Africa?

According to Ref. [

41], despite the advantageous effects of financial inclusion, there are certain challenges and debates in the policymaking arena. These disputes are related to the difficulties that policymakers face on a daily basis, and they also explain why various nations have diverse financial inclusion approaches. The discussion of the most important challenges is below.

(a) Lack of digital infrastructure and services: One major barrier to digital applications in the developing world, particularly in Africa, is a lack of digital infrastructure, including network connections to digital devices as well as software and applications. For example, it has been recorded that more than half of the world’s population does not have access to a network [

42].

Furthermore, unlike in the developed world, there is a significant barrier to establishing high-speed connections in areas where network connections have been expanded [

43].

(b) The “inactive users of financial services’ problem: The inactive user problem is one developing issue in policy debates about financial inclusion. When united, individuals become either engaged or inactive consumers of banking services in the official financial system. Even when an enormous effort is expended to integrate the excluded into the financial sector, these individuals may opt to become passive consumers of financial goods and services after a period of time. People open formal accounts but refuse to obtain card payments; they do not even maintain deposits in their official accounts, and they do not conduct financial transactions from their official accounts. They only use their official accounts to earn income and do not use them to transfer money to others. These inactive consumers provide a new dilemma for policymakers since the financial inactivity they generate diminishes the number of financial transactions, income to financial institutions, and tax revenue to the government, all of which have an impact on economic production.

(c) Lack of cooperation by banks: Another concern is that financial firms may refuse to collaborate with policymakers aiming to promote financial inclusion using banks. Before engaging in financial inclusion programs, banks will often perform internal cost–benefit studies. Banks may be hesitant to engage in financial inclusion programs if the expense outweighs the benefit, particularly if the government is reluctant to pay the cost to banks. In nations with both private and state-owned banks, private-sector banks may be hesitant to engage in financial inclusion programs because they believe the government will utilize its own public-sector banks to fulfill its financial inclusion goals. Although bank regulators oblige all banks to engage in the country’s financial inclusion program, many banks tend to utilize government cash and enable the use of their banking facilities to meet the program’s objectives. In other circumstances, private-sector banks may only engage in the public economic inclusion program during the first two years before withdrawing gradually owing to mounting expenses and sustainability difficulties, similar to the scenario in India. In India, the government established Pradhan Mantri Jan-Dhan Yojana (PMJDY) as the country’s financial inclusivity framework. Commercial and government banks had a great number of Jan Dhan account recipients within the first two years, but during the third and fourth years, the number of Jan Dhan account recipients decreased dramatically for private-sector banks.

(d) Difficulty in identifying the excluded population: When excluded individuals of the community are not recognized, the identification challenge of financial inclusion emerges. Even though researchers do not have complete information about which members of the general public are rejected from the formal financial sector, it can be challenging to precisely identify the excluded population and even harder to depend on the results of studies for which the methodologies and hypotheses are unknown. Financial inclusion studies are frequently confounded by the procedures, assumptions, methodologies, and other unobservable characteristics used to determine the “excluded members of society” in the sample size of the many other studies.

(e) Lack of coordinated efforts (public–private partnerships): In most emerging countries, particularly in Africa, there is a significant lack of coordinated effort by governments, businesses, research institutions, and civil society groups to promote social and economic inclusion and equality. For example, when internet service providers (ISPs) enable greater access to the internet for many people but do not provide relevant government agencies with oversight of these service providers’ activities, the result can be greater control by the ISPs rather than digital empowerment and inclusion. Similarly, the absence of checks and balances between enterprises that benefit from economies of scale may result in a market monopoly that is often characterized by inefficiency owing to a lack of competition [

43].

(f) Lack of digital skills: A lack of digital literacy in Africa makes it difficult for people to effectively use modern technologies and provide value in the ICT or internet space. Physical internet connectivity is a must, but Ref [

37] argue that one of the biggest obstacles to fully participating in the digital economy is a lack of skills. For instance, fewer than half of internet users in Africa have the most recent skills necessary to keep up with the rapidly evolving digital landscape. It is important to note that it is challenging to fully use digital technology without the right education and skill development.