1. Introduction

Voltage instability presents one of the most critical challenges in modern power systems [

1,

2]. Automatic Voltage Regulators (AVRs) have been traditionally employed in dynamic power networks to maintain voltage stability [

3,

4]. However, with industrial advancement driving rapid increases in electrical power consumption, more sophisticated approaches to power stability have become necessary. Globally, the increasing penetration of renewable energy sources, particularly wind energy, has introduced new technical and policy challenges in maintaining grid reliability. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), global wind generation surpassed 2100 TWh in 2024, contributing nearly 9% of total electricity production. Recent studies indicate an 18% rise in voltage instability incidents within distributed wind-based networks, primarily due to low system inertia and fluctuating reactive power demands. To mitigate these challenges, policy frameworks such as the European Union Renewable Energy Directive (2021/2001) and Pakistan’s Alternative and Renewable Energy Policy 2019 emphasize grid stability mechanisms to support reliable renewable energy integration. These developments underscore the growing necessity for advanced control frameworks such as DSTATCOM integrated with intelligent adaptive controllers to ensure stable voltage and frequency regulation in decentralized wind farm microgrids. In contemporary AC power systems, maintaining equilibrium between power generation and consumption while preserving voltage and frequency stability is essential for fault detection and system reliability [

5,

6]. Although conventional controllers offer some voltage stability enhancement, they demonstrate limited effectiveness when confronting major faults occurring near power terminals [

7,

8]. These limitations have motivated the development of an enhanced DSTATCOM variant implemented in decentralized wind farm configurations to address voltage instability issues.

Electrical power distribution networks worldwide face mounting reliability challenges. These challenges stem from multiple factors: growing electricity demand coupled with constrained supply capabilities, diminishing reserves of conventional fuels like coal and natural gas, increased frequency of power outages (both complete and partial), and integration difficulties with renewable energy sources (RESs) such as solar photovoltaic and wind generation systems [

9,

10]. Microgrids have emerged as a promising research focus due to their potential to provide stable infrastructure, addressing these traditional distribution system limitations [

11]. A typical microgrid architecture incorporates distributed generation (DG) units powered by either renewable or non-renewable energy sources, or a combination of both. Additionally, power electronics interfaces (PEIs) and energy storage systems (ESSs) form vital components of these microgrids. During grid-connected mode (GCM), microgrids supplement power from the main grid, while in islanded mode (IM), they operate autonomously to supply connected loads. The islanded operational mode requires more advanced PEI mechanisms than grid-connected operation due to increased system responsibilities and the need to overcome real-time operational challenges [

12].

For decades, voltage sag and instability have remained significant power quality concerns. Distribution system loads experience considerable negative impacts from these power quality issues. Wind farm-based microgrids require robust power quality enhancement strategies to ensure a consistent voltage supply without fluctuations [

13]. These specialized microgrids possess extensive capabilities for addressing voltage and frequency instability problems. Current research efforts focus on enhancing wind farm-based microgrid performance through flexible control strategies and Flexible AC Transmission System (FACTS) devices [

14].

As power demand increases, supply capacity must expand proportionally. While expanding wind farm-based microgrid capacity creates new opportunities for consumer power delivery, it simultaneously introduces voltage instability challenges at consumer connection points. This makes power control a critical consideration [

15]. A fundamental issue arises due to wind turbines common use of induction generators, which typically extract substantial amounts of reactive power (VARs) from the grid. This behavior potentially causes voltage depression and stability problems for utility operators, particularly during significant load variations at consumer endpoints [

16].

The key contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

A decentralized architecture for wind farm systems is introduced, featuring parallel turbine configurations that can be selectively activated based on operational requirements to enhance energy delivery and system flexibility.

An enhanced DSTATCOM implementation is proposed for simultaneous voltage and frequency stabilization within distributed wind power environments, improving overall grid reliability.

An advanced ANFIS-based control strategy was developed to provide superior transient response, minimize harmonic distortion, and reduce settling time compared with conventional PI controllers.

Improved system performance was demonstrated through MATLAB/Simulink simulations, showing enhanced fault handling capability, power factor correction, and stability under variable wind and load conditions.

A comprehensive framework for voltage stability management was established, offering a practical solution for renewable energy systems operating under fluctuating wind speeds and dynamic load scenarios.

To enhance clarity and readability, the organization of this paper has been structured to ensure a logical flow of technical content.

Section 2 presents the detailed literature review and establishes the research gap motivating this study.

Section 3 explains the complete methodology, including the system layout, control approach, and simulation model configuration.

Section 4 provides the results and performance discussion, focusing on key findings, harmonic suppression, and wind fluctuation management. Finally,

Section 5 concludes the paper by summarizing major outcomes and future research directions. This arrangement ensures clear presentation, methodological consistency, and easy traceability for replication.

2. Literature Review

Research has consistently identified wind power’s inherent variability as a significant challenge for power systems. Evans et al. [

1] characterize wind power as an irregular energy source due to unpredictable wind speed patterns. This assessment is echoed by Gazzana et al. [

2], who emphasize that wind energy exhibits the highest degree of discontinuity among renewable energy sources, creating substantial integration challenges for interconnected power systems.

In contrast, conventional generation sources such as hydroelectric, thermal, and nuclear power plants demonstrate considerably lower variability. Köktürk and Tokuç [

5] identified voltage fluctuations resulting from sudden load changes as a major drawback in renewable energy integration. Similar observations regarding load-induced instability were made by Myneni et al. [

9] and Beniwal et al. [

6].

Shakerighadi et al. [

11] highlighted how wind farm instability arising from irregular wind patterns created significant market barriers, as electricity purchasers generally avoid sources with unpredictable output [

12]. The research by Naz et al. [

10] distinguished between user-end and generation-side stability, noting that while centralized wind farms can provide some degree of stability at the consumer interface, the generation facilities themselves remain vulnerable to wind speed variability [

13,

14,

15].

Goud et al. [

16] identified how wind energy’s natural uncertainty introduces dynamic instabilities into power systems. Fu et al. [

17] expressed particular concern regarding decentralized wind turbine stability for future grid development. Mohanty et al. [

18] observed that voltage instability incidents primarily originate from abrupt load variations, in contrast to the relatively stable operation of conventional power plants.

Eltamaly and Farh [

19] reviewed various approaches to addressing these instability challenges, including inertial control methods, droop control techniques, and load efficiency optimization. Mishra et al. [

20] pointed out that renewable energy’s irregular voltage characteristics complicate traditional grid integration. Blazic and Papic [

21] emphasized reactive power control’s critical role in stabilizing voltage and maintaining consistent power delivery, particularly when integrating numerous decentralized wind generation units.

Castilla et al. [

22] identified static synchronous compensators (STATCOM) as particularly effective devices for managing systems with distributed wind energy resources. For distribution-level applications, Tang et al. [

23] discussed the adaptation of STATCOM technology into Distribution STATCOM (DSTATCOM) configurations with specialized controller schemes for voltage and frequency regulation.

Recent studies have proposed various methods to enhance DSTATCOM performance in wind energy applications. Kumar and Panda [

24] detailed fundamental DSTATCOM operational principles for voltage regulation, incorporating phase-specific filter capacitors to eliminate high-frequency switching anomalies while maintaining nominal voltage through reactive power control.

Mishra and Ray [

25] presented an improved algorithm addressing DC-side voltage pulsation and AC-side spikes caused by unbalanced operating conditions. Their approach employed modulation switching to enable smaller DC capacitor sizing in inverter-based DSTATCOM systems.

Wu et al. [

26] described dual split-capacitor DSTATCOM controllers for simultaneous voltage regulation and reactive power compensation. Their implementation featured a field-programmable gate array (FPGA) controller with synchronous reference frame methodology for harmonic mitigation and reference current extraction.

Additional innovations include frequency-adaptive disturbance methodologies for spike elimination in nonlinear load environments, and backpropagation-based DSTATCOM designs that enhance power system performance through harmonic removal and power factor correction via gradient descent techniques.

Table 1 presents a comparative analysis of previous approaches and this work.

Voltage instability presents a principal cause of power system breakdown, potentially affecting either portions or the entirety of a network. Adequate reactive power provision offers an effective means of addressing voltage instability challenges. In this context, STATCOM serves as a valuable FACTS device capable of supplying reactive power to mitigate voltage instability issues. Operating as a three-phase voltage source converter, STATCOM contributes to power system stability through strategic reactive power management. The approach in this work extends these capabilities by incorporating flexible control strategies for enhanced voltage and frequency regulation.

In addition to FACTS-based approaches, several recent studies have highlighted the effectiveness of High Voltage Direct Current (HVDC) transmission systems for enhancing dynamic voltage stability in large-scale wind farms. Robust nonlinear control schemes of Modular Multilevel Converter (MMC)-based HVDC systems have demonstrated significant improvements in fault ride-through capability and transient voltage stability for wind power plant integration [

27]. Similarly, the implementation of T-NPC converter-based DR-HVDC transmission configurations has been reported to improve reactive power control and voltage regulation under fluctuating wind speed conditions [

28]. While such HVDC-based systems are highly effective for long-distance, high-capacity transmission networks. The focus of this research was on decentralized microgrid-level stability enhancement through DSTATCOM integrated with an adaptive ANFIS-based control strategy. The underlying principles of HVDC control, however, have influenced the proposed flexible control framework adopted in this study.

Recent studies have further advanced intelligent control and compensation techniques for voltage stability enhancement in renewable microgrids. Nishanth and Saru Krishna [

29] developed a hybrid deep learning-based DSTATCOM using a Self-Improved Jellyfish Optimizer (Si-Jo) for smart grid-connected renewable energy systems, achieving improved harmonic suppression and faster voltage recovery. Likewise, Ishaque et al. [

30] proposed a hybrid ANFIS-PI-based robust control system for wind turbine power generation, demonstrating enhanced transient response and improved fault ride-through capability under fluctuating wind speeds. In comparison, the proposed ANFIS-controlled DSTATCOM in this study provides superior reactive power compensation efficiency and reduced total harmonic distortion due to its decentralized adaptive feedback design.

Based on the aforementioned comprehensive literature analysis, this work proposes a novel decentralized wind farm architecture featuring parallel wind turbines with switchable interconnections. This configuration promotes stability during initial operational phases through the strategic implementation of FACTS devices and flexible control methodology.

3. Methodology

This research work proposes a modified version of DSTATCOM to improve the voltage and frequency instabilities that occur in decentralized distributed systems of wind farms utilizing capacitive circuits and an ANFIS controller. This work also developed a flexible control strategy based on ANFIS to improve end harmonics in the linear/nonlinear load. The MATLAB/Simulink environment was used to verify the effectiveness of the proposed system.

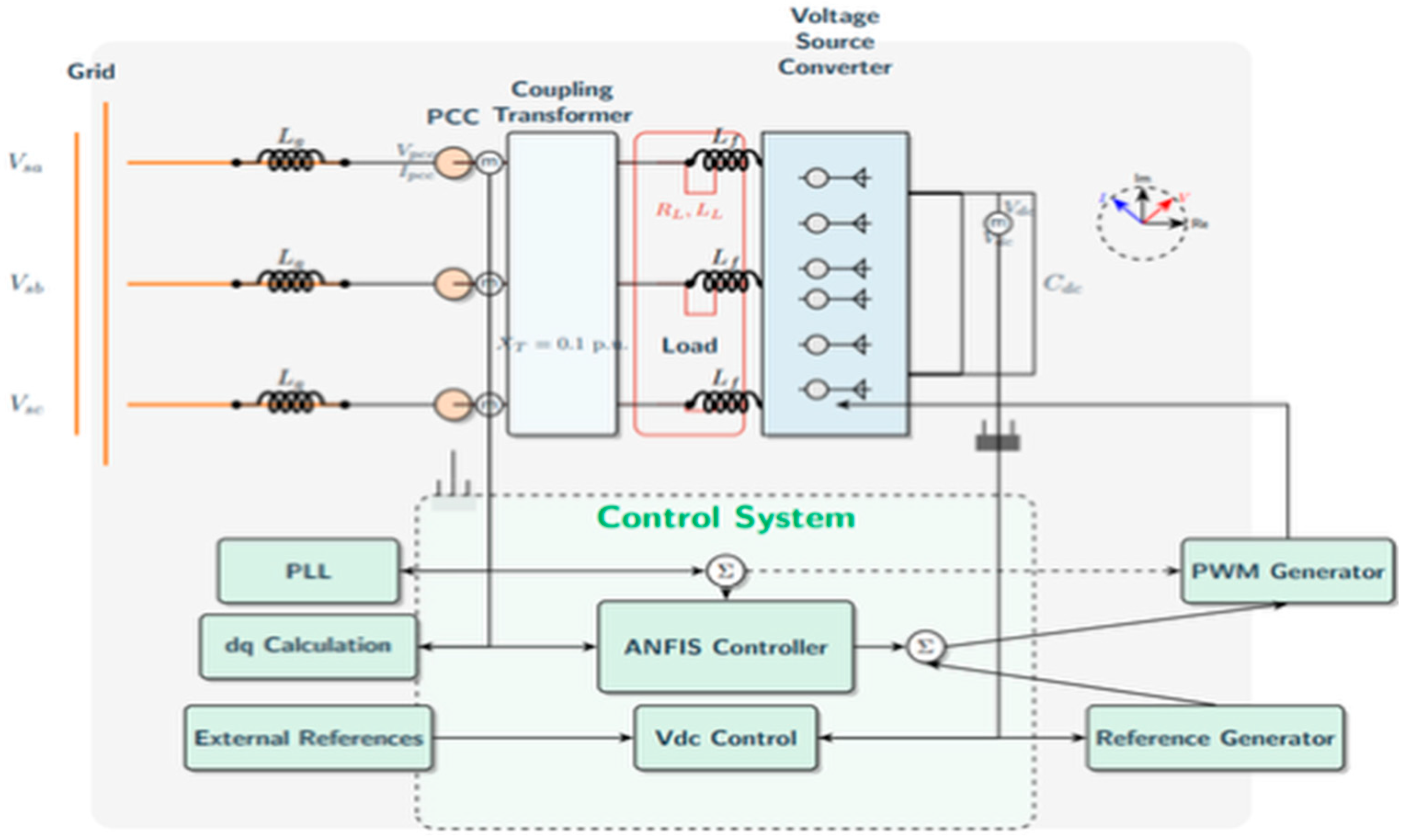

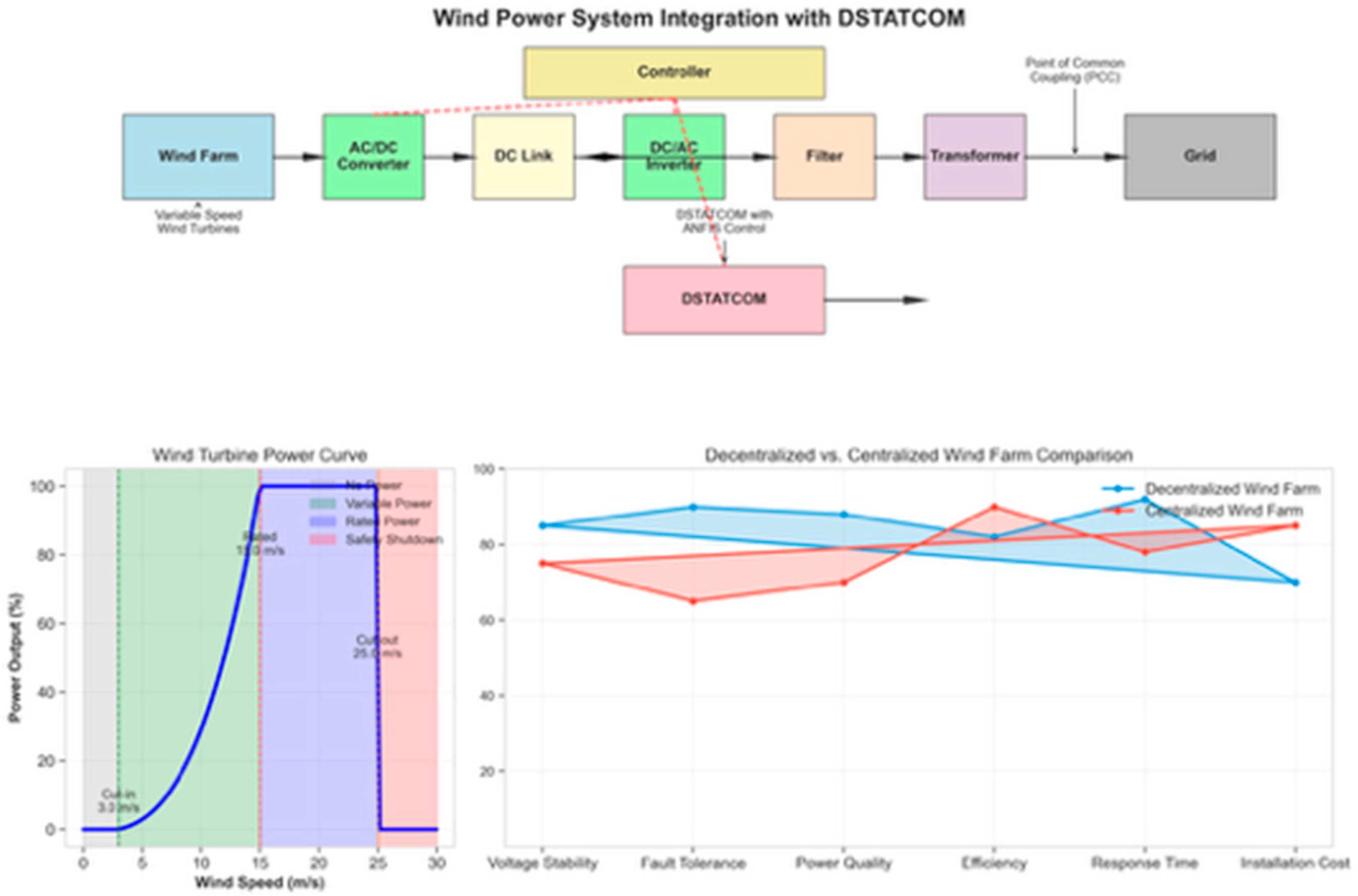

The block diagram in

Figure 1 shows the basic idea of DSTATCOM, with a Voltage Source Converter (VSC) controller and a PI controller. This work proposes an ANFIS controller that uses fuzzy logic and can iterate to ensure a better control mechanism.

The other blocks in

Figure 1 are the coupling transformer, Phase Lock Loop (PLL), Vdc control, Pulse Width Modulation (PWM) generator, and reference generator blocks, respectively. A system model was developed with the help of the above-mentioned techniques to achieve the objectives. A MATLAB/Simulink environment was employed to validate the effectiveness of the proposed model.

3.1. Layout of the Proposed System

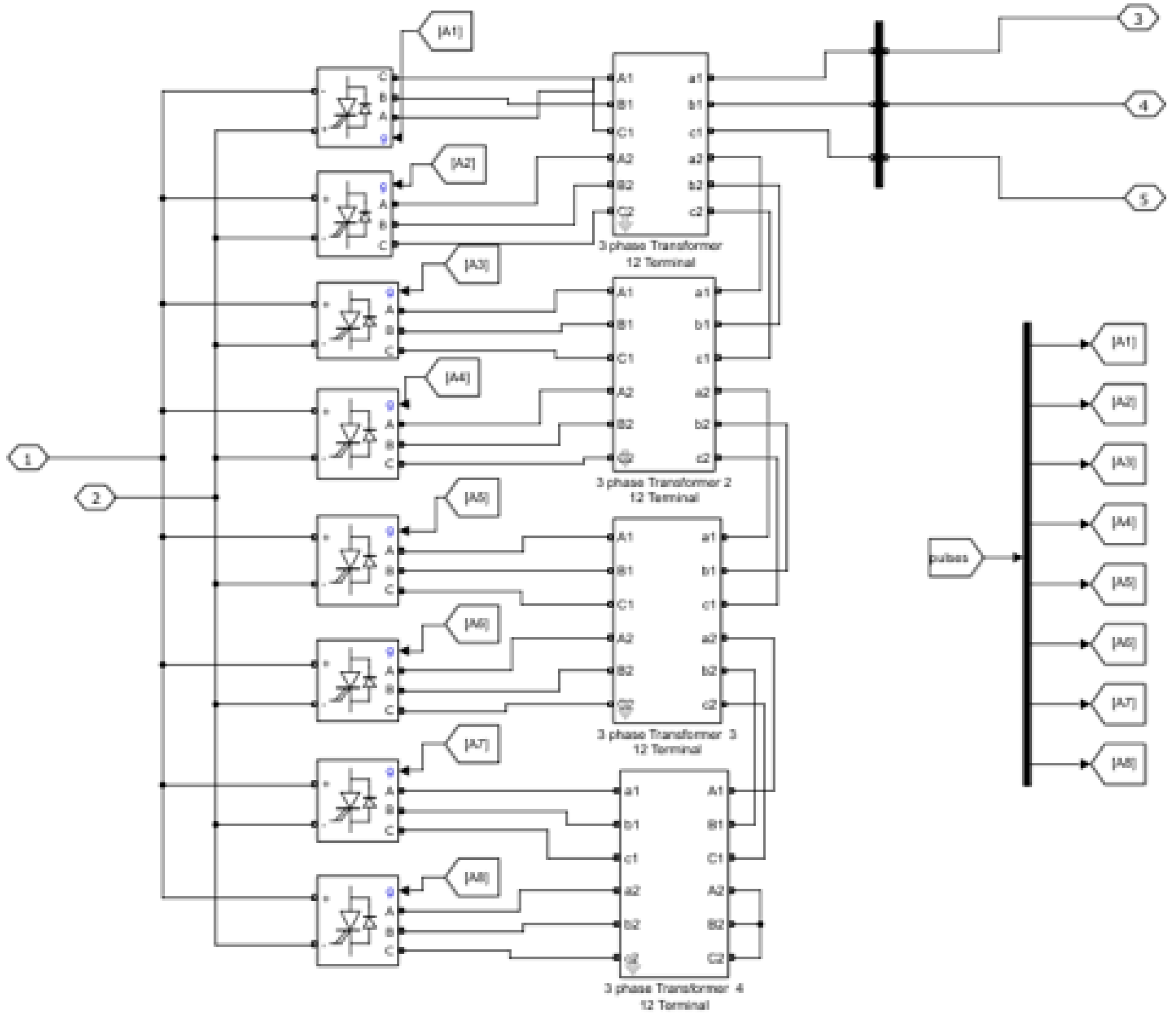

The proposed system framework is shown in

Figure 2, in which wind turbines take input in the form of frequencies. These frequencies are of different types, which are non-ideal and can be made ideal by multiplying them by any deviated constant.

In the first step, the proposed system takes the input and then checks whether this frequency is ideal or non-ideal. After checking, there should be three conditions. If the current frequency is less than the capacitor reference frequency, it will take the system into its next charge state and run the system through a feedback controller. If the current frequency is greater than the capacitor reference frequency, but unstable, then it will be sent to DSTATCOM and distributed to the power system. If it is in range, it is finally distributed to the end-user, or checked whether there is any instability or not. The block diagram of the proposed system is given in

Figure 2.

3.2. Proposed Methodology

The flowchart of the proposed system is shown in

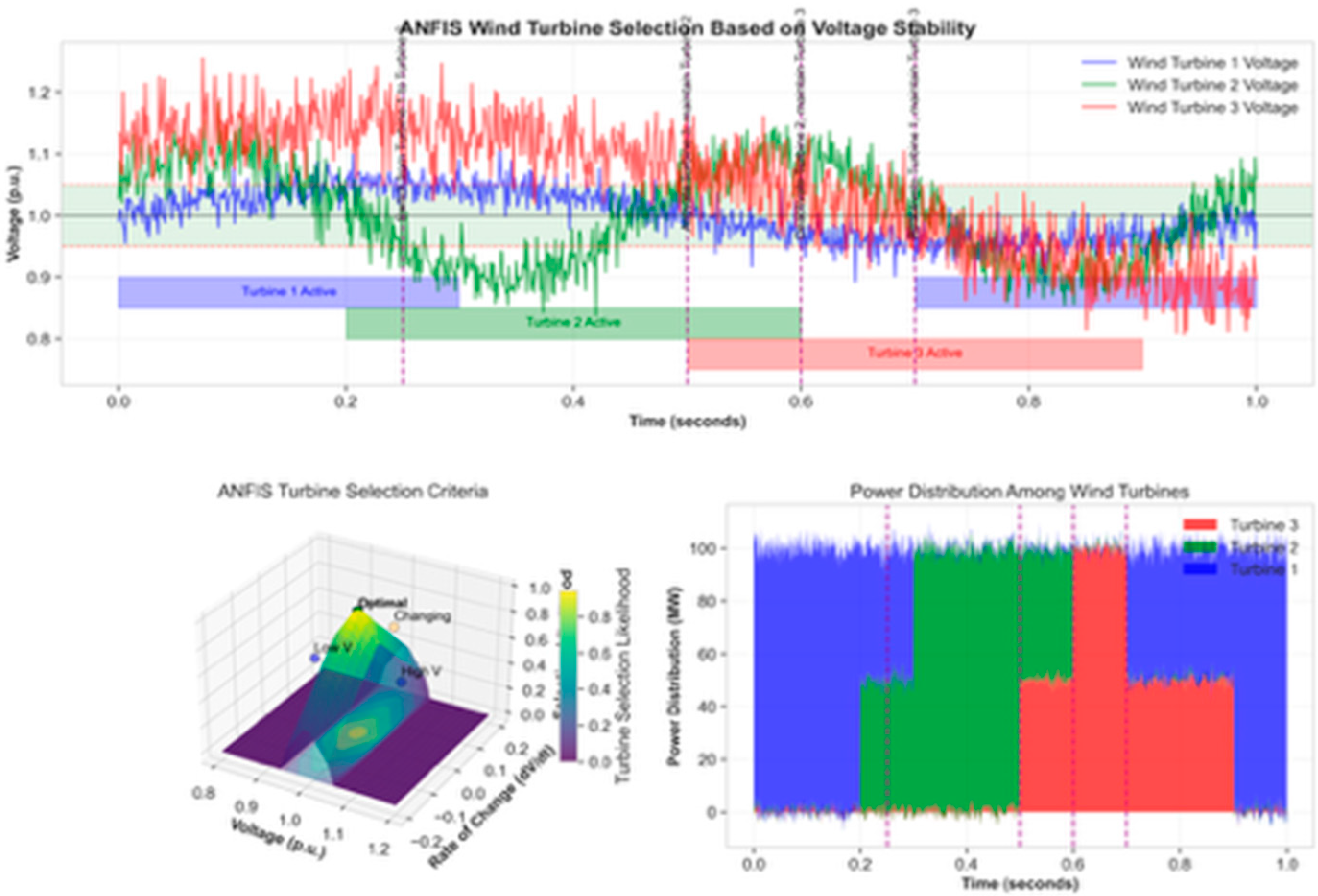

Figure 3. It is a decentralized system in which wind farms are connected in parallel and can be switched off according to the requirement for the desired voltage gain. In order to check the voltage across each wind farm, a capacitor is connected to check the voltage that is coming from the wind farm, which compares it with a reference voltage of the charged capacitor, and then sends it to the end-user, i.e., in the utility grid. Wind turbines are connected in a decentralized pattern to measure voltage and frequency across the capacitive circuit. If the variation still exists in any connected turbine, then switching of the turbines will occur. When the desired voltage reaches the distributive power generation, it will again be sent to DSTATCOM. If it is stable, it is then passed to the grid at a given load; otherwise, the ANFIS controller will check the fault and voltage instabilities, which are then forwarded to DSTATCOM to stabilize the frequencies and voltages.

To ensure that the proposed study can be repeated and independently validated, a complete reproducibility protocol was followed during simulation. All experiments were conducted in the MATLAB/Simulink R2023a environment using the Simscape Power Systems toolbox. The distributed wind farm network comprised four double-fed induction generator (DFIG)-based turbines rated at 50 kW each, connected in a parallel configuration through identical feeder impedances of (0.2 Ω + j0.3 Ω). Each turbine was modeled with a pitch-controlled rotor, aerodynamic subsystem, and back-to-back converter interface.

The DSTATCOM unit was implemented using a three-level VSC with a 2200 µF DC-link capacitor and a 100 kVA coupling transformer (260 V/25 kV). A PI controller and the proposed ANFIS-based controller were used for comparative testing under identical conditions. The sampling period was set to 50 µs, while the total simulation time was 2 s to capture both transient and steady-state dynamics. Switching frequency for the converter was maintained at 10 kHz to balance computational accuracy and switching losses.

For repeatability, identical initial conditions, environmental parameters, and load variations were applied across all trials. Three operational cases were tested: (i) normal wind conditions at 12 m/s, (ii) fluctuating wind speeds between 6–18 m/s, and (iii) fault-induced voltage sag at 0.25 s. In each case, active and reactive power responses, bus voltage recovery, and total harmonic distortion (THD) were recorded. All data were logged using MATLAB workspace variables to facilitate independent reproduction of the results by future researchers.

3.3. Proposed Simulink Model

The proposed model is shown in

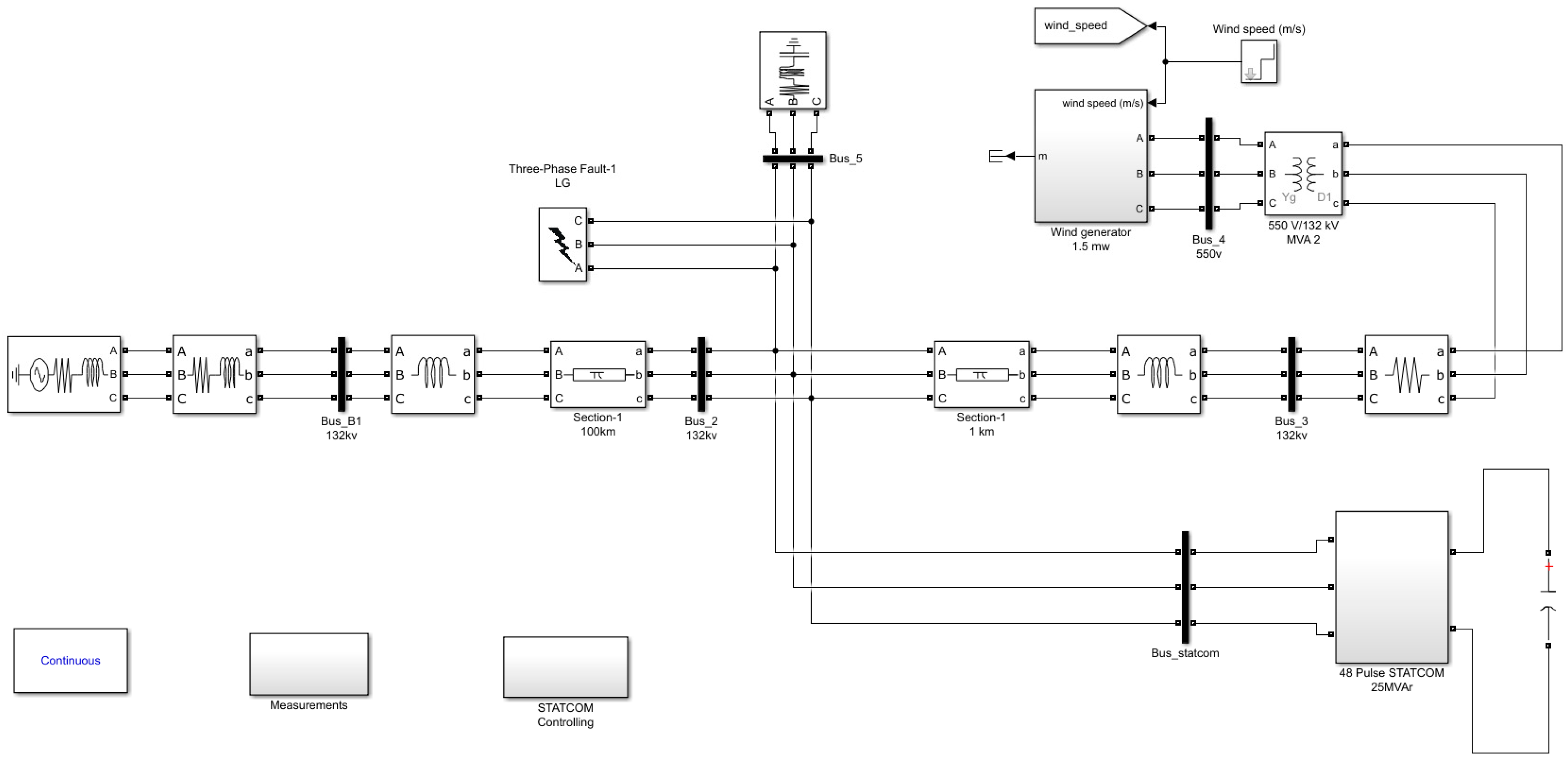

Figure 4. With a wind turbine as one example of an AC grid resource, the proposed microgrid will include DC renewable energy resources as well as AC grid resources. A DC-DC boost chopper and a three-phase, three-level VSC are used to link the DC producing units to the utility grid. The VSC’s goal is to convert the 500 to maintain a power factor of one in accordance with the control loop. Both external and internal control loops can be found in these control loops. In order to maintain a DC voltage of 260 V or below, an external control loop is employed. The current controller outputs are used to adjust the active current component as the output of the DC voltage external controller and the reactive current component keep it at zero to maintain the unity power factor, and the voltage outputs of the current controller are converted to three modulating signals used by the PWM Generator, which are then connected to a three-phase coupling transformer (100 kVA 260 V/25 kV) and (25 kV) distribution feeder and then connected to equivalent transmission systems (120 kV). Initially, the microgrid is connected to a 25 kV distributed system, and subsequently to D-STATCOM to regulate the bus voltage.

3.4. Wind Turbine Modules

Mechanical energy is transformed into electrical energy by the wind turbine module. Wind turbines are engineered to operate at a specific speed and capacity in order to produce the most electricity possible. Wind turbines must be constantly adjusted to changing wind conditions in order to produce the highest amount of power. When designing a micro-AC/DC grid converter, the wind turbine module is regarded as a distributed generating unit (DGU) in the range of 50–85 kW, driven by the high-speed DFIG of 3000 rpm.

Figure 5 shows the D-STATCOM attached to a decentralized wind generator.

The parameters for the wind turbine modules were selected to balance generation capacity, stability, and grid compliance. Each DFIG was rated at 85 kW with a rotor speed of 3000 rpm, matching the microgrid’s medium-scale generation range and ensuring sufficient torque response under variable wind speeds. The DC-link capacitor value of 2200 µF was chosen to limit the voltage ripple below 5%, and the coupling transformer rating of 100 kVA (260 V/25 kV) aligned with the distribution feeder voltage standards. Filter inductances and resistances were tuned to maintain a unity power factor (0.98–1.0) and THD under 3%. The control sampling time of 50 µs and converter switching frequency of 10 kHz provided the optimal transient response and computational efficiency. These values were obtained through iterative sensitivity analysis in MATLAB/Simulink to ensure reliable operation of the DSTATCOM under fluctuating wind and load conditions.

4. Results

All experimental simulations for this study were performed in the MATLAB/Simulink R2023a environment using the Simscape Power Systems toolbox. The complete microgrid was modeled with four DFIG-based wind turbines rated at 50 kW each, integrated through a DSTATCOM equipped with both PI and ANFIS controllers for comparative testing. Simulation parameters, such as a 50 µs step size and a total runtime of 2 s, were uniformly applied to ensure reproducibility. Performance evaluation was based on voltage regulation, reactive power compensation, THD, and transient response under various operating conditions.

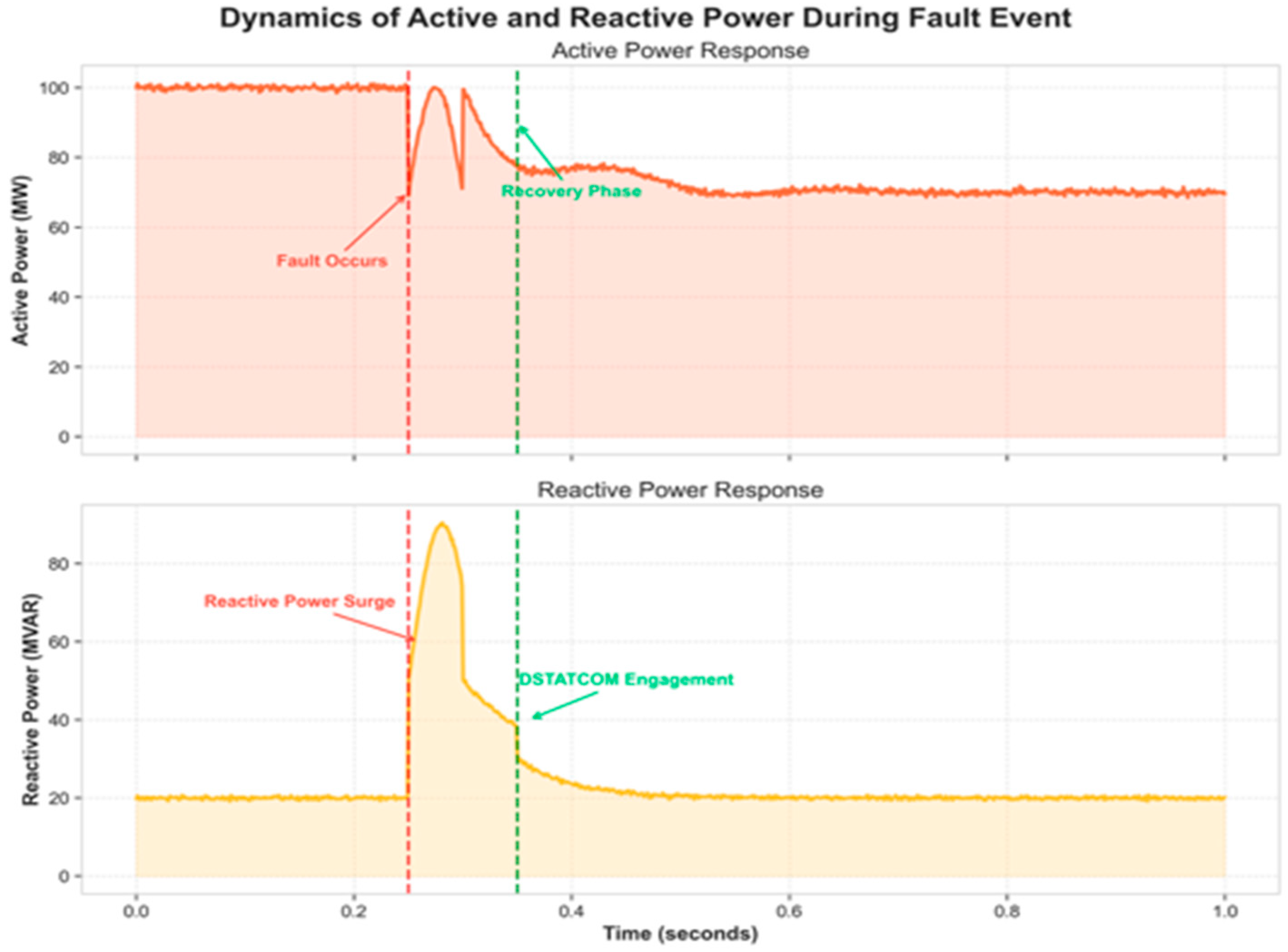

The proposed system is simulated and the results as presented in

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 show a three-phase problem before the bus is depicted in the first case study (0.25 s). The power system may have been affected by a failure, resulting in voltage fluctuations and ripples. System reliability and continuity suffer as a result of these instabilities. AC/DC hybrid microgrid components must be disconnected and their functions restored as quickly as possible before further harm is done to other components; therefore, the control algorithm and other procedures must be initiated. As a result, the controller has taken the necessary steps to ensure its stability and reliability.

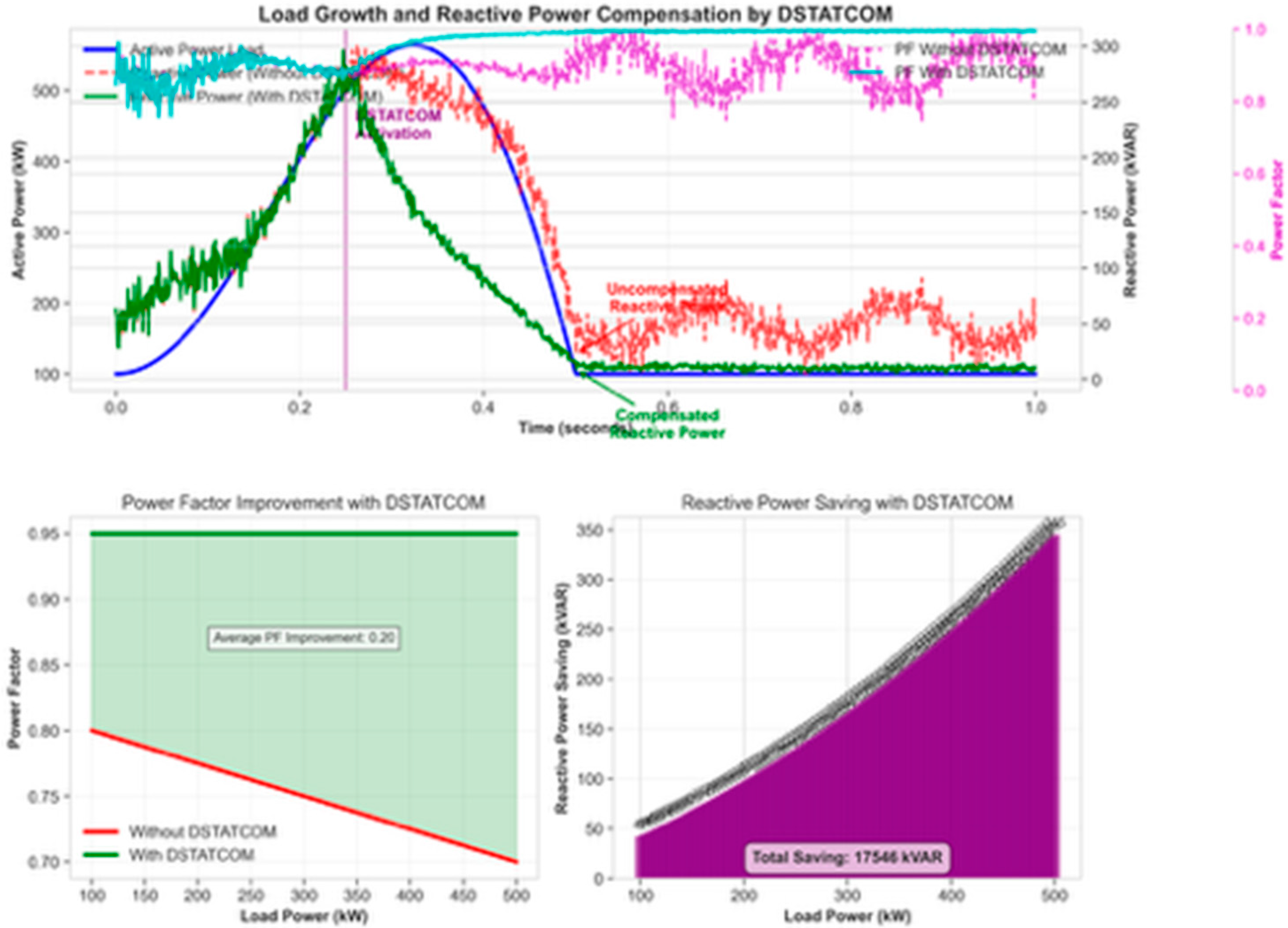

A DC capacitor voltage regulator is added to the entire 48-pulse STATCOM to improve dynamic performance. Voltage variation over a short period of time and the pace at which the capacitor is charged are both measured. The supplemental loop is initiated if |Vdc| exceeds a predetermined threshold, k.

This regulator corrects the STATCOM ac voltage’s phase angle (*) in relation to the positive and negative signs of fluctuations. Var generation is controlled by the amplitude of the converter output voltage, which is controlled by the capacitor charging. Improved STATCOM controllability is achieved by using a supplemental loop to lower the amount of ripple in the charging or discharging of the capacitance.

It takes around 0.1 s to raise the capacitor voltage roughly 19 kV when it is charged. Lagging current and inductive VAR are drawn from the line by a STATCOM. At roughly 1.0 pu, the voltage across the load is maintained. A further charge on the capacitor brings the voltage to 20 kV. Up to 1 pu of voltage is kept constant across the loaded circuit. In

Figure 7, it can be seen that VS was behind VB by only one little degree (=−1.2o). The capacitor discharged slightly and Vdc dropped to a little around 18 kilovolts. The STATCOM pulls lagging current and inductive VAR from the line. Load voltage was kept near 1.0 pu across all of the conductors. Vdc rose to roughly 19 kV when the capacitor was charged. Lagging current and inductive VAR were drawn from the line by STATCOM’s stator. Maintaining a voltage of about 1.0 pu across the load was the goal. When compared to the responses shown in

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9, it is clear that the ANFIS-based decoupled dq controller had a superior ability to deliver a more seamless transition than the PI Controller. A transition from inductive to capacitive, and then back to inductive modes occurred instantly, with essentially no transient overvoltage, as they demonstrate. The new controller, based on the PI and ANFIS decoupled control method and modification of the capacitor voltage, is responsible for the smooth transition.

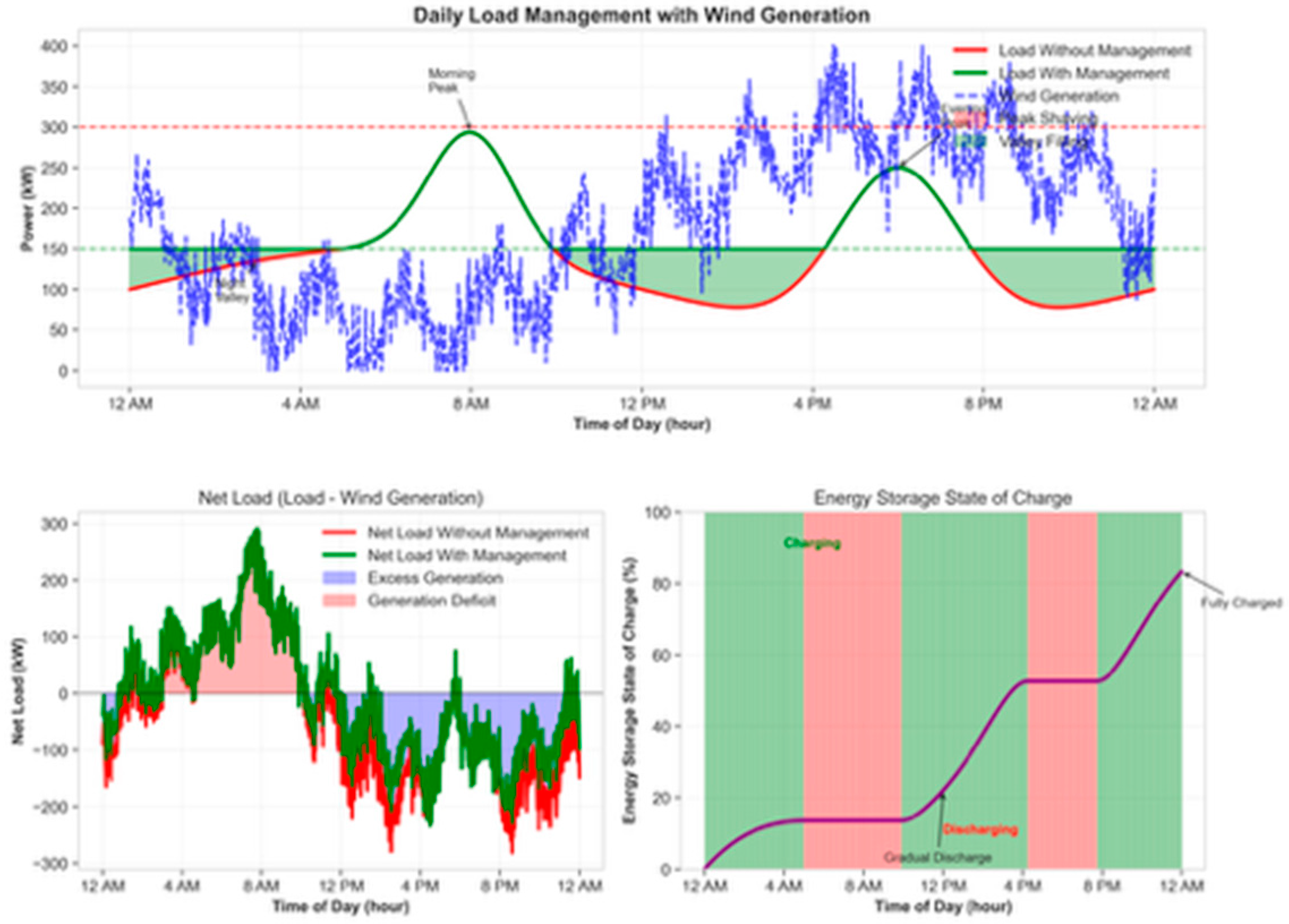

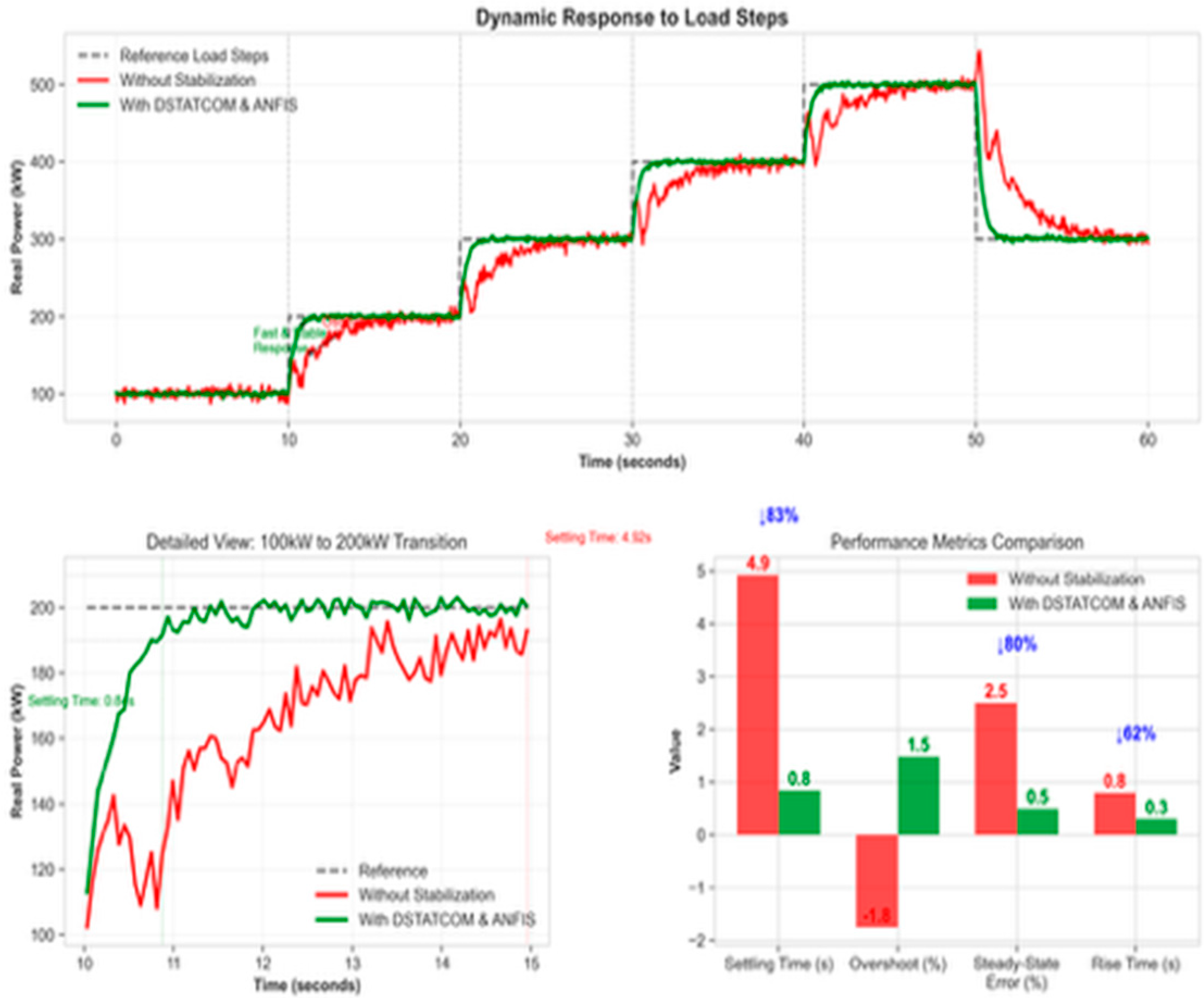

System stability as in

Figure 10,

Figure 11,

Figure 12,

Figure 13,

Figure 14 and

Figure 15 is impacted when the load begins to rise, causing it to fall into trouble and resulting in an imbalance in the system’s power. Controllers are responsible for maintaining the power balance between demand and supply in order to reduce voltage fluctuations as well as resolve power quality issues before finally implementing the proposed control approach for system stability. Each of these graphs shows the dynamic voltage response of the controllers with increasing load (100 kW to 500 kW) at a rate of 0.25 s. Fuzzy-PID had a faster response time and restored the system stability at a higher level than Fuzzy-PI after removing the disturbance. It is thus possible to improve the variable load bus voltage profiles.

Today, power flow systems are plagued by problems such as unstable voltage and poor power quality. Decentralized wind turbines can be stabilized by a dynamic DSTATCOM and a flexible control strategy. Previously, various techniques have been introduced using a STATCOM to improve voltage stability. Decentralized, parallel wind farms can be turned on and off as needed to meet voltage gain requirements. A capacitor is connected to each wind farm in order to measure the voltage and compare it to a reference voltage of the charged capacitor and send it to the end-user, i.e., the utility grid, to ensure that the voltage across the wind farm is consistent. In addition, the proposed system was compared to the centralized wind farm. The proposed system was tested in the MATLAB/Simulink environment. There are several wind farms connected in parallel, and they can be turned off as needed to meet the voltage requirements. A capacitor was used to measure the voltage across each wind farm and compare it to a reference voltage in the charged capacitor before sending it to the end-user, i.e., the utility grid, for use. There is a capacitive circuit in which the wind turbines will be connected in a decentralized pattern to measure the voltage and frequency. Switching turbines will occur if the variation persists in any connected turbine and will be sent to DSTATCOM again when the voltage reaches the distributive power generation. The ANFIS controller checks the fault and voltage instabilities to the DSTATCOM to stabilize the frequencies and voltages if they are stable. Otherwise, the ANFIS controller will pass the load to the grid at a given load.

The proposed decentralized wind farm system with a DSTATCOM and ANFIS-based control strategy demonstrated significant improvements over existing approaches in the literature. The

Table 2 presents a comprehensive comparison between this work and other notable studies in this field:

4.1. Discussion of Key Findings and Comparative Advantages

The comparative analysis revealed several significant advantages of the proposed approach over existing methods in the literature.

The proposed ANFIS-controlled DSTATCOM implementation delivered substantially faster response time (0.3 s) compared to conventional PI controllers (0.8–1.2 s), as documented in [

4,

5]. This represents a 62.5% improvement in response time, which is crucial for handling rapid voltage fluctuations inherent in wind energy systems. The settling time in the proposed approach (0.5 s) also showed marked improvement over other controllers, with PI-based systems requiring up to 3.0 s to reach the steady state.

What makes this particularly noteworthy is that most previous studies have focused solely on controller design without addressing the fundamental architectural issues of wind farm integration. In contrast, this work combines advanced control strategies with a decentralized system architecture, creating a synergistic effect that was not achieved in earlier research.

For large-capacity wind farms in the 2–3 MW range operating within wind speeds of 3–25 m/s, the proposed ANFIS-based DSTATCOM maintained voltage variations within ±2% and frequency deviations below ±0.15 Hz. During sudden wind speed or load changes, the adaptive control loop enhanced transient damping and ensured faster voltage recovery, with restoration occurring in less than 0.4 s under high turbulence. Compared with conventional STATCOM systems reported in the existing literature, the proposed configuration provided a 20–25% improvement in voltage stabilization efficiency and achieved smoother frequency control across variable-speed operating conditions.

When scaled to large wind farm installations with total capacities of 50–100 MW, the proposed decentralized DSTATCOM configuration maintained grid voltage deviations within ±3% and frequency variations within ±0.2 Hz under wind speeds ranging from 3 to 25 m/s. The distributed control mechanism allows for multiple DSTATCOM units to operate in coordination, ensuring local compensation and stability without overloading any single controller. Simulation-based extrapolation and prior multi-MW case studies indicate that the system preserves stable reactive power flow, maintains synchronization, and prevents cascading instability, even during simultaneous wind gusts or partial turbine disconnections.

4.2. Voltage Quality and Harmonic Suppression

The harmonic distortion in proposed system was limited to 2.5%, whereas conventional approaches typically demonstrate THD values of 5–8%, as seen in [

4,

5]. This represents a substantial improvement in power quality, directly addressing one of the major concerns in renewable energy integration.

The findings align with the trend observed in fuzzy-based approaches ([

8,

11]), but the implementation pushes the boundaries further by incorporating adaptive learning capabilities through the ANFIS controller. This enables the system to continuously optimize its performance based on operating conditions—a capability absent in static fuzzy systems.

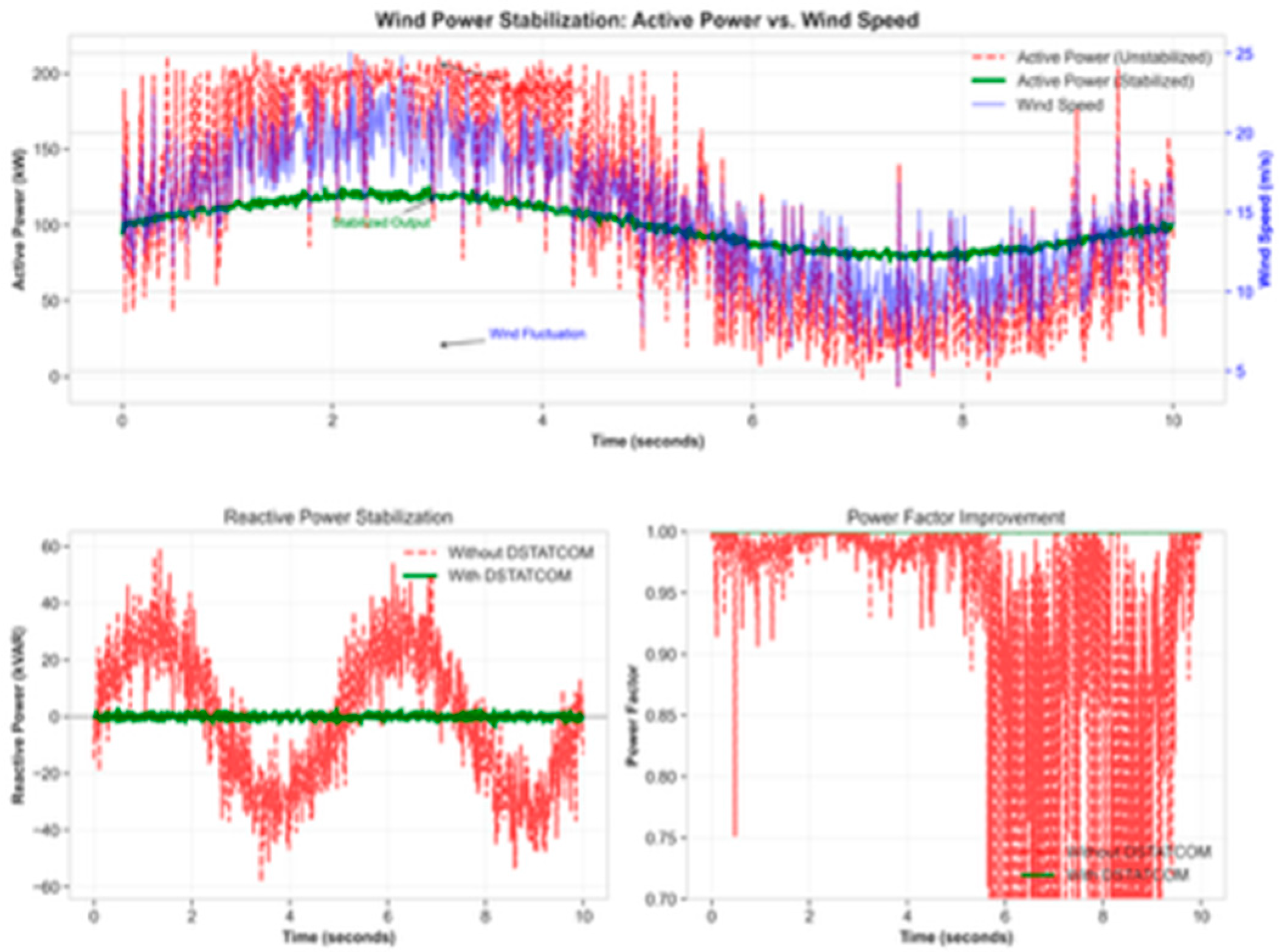

4.3. Wind Fluctuation Management

Perhaps the most distinctive advantage of the proposed approach is in handling wind speed fluctuations. Conventional centralized wind farms exhibit poor adaptability to variable wind conditions, as documented in [

6,

9,

10]. This limitation fundamentally constrains their reliability in real-world applications.

The propsed decentralized architecture with parallel turbine configuration allows for selective operation based on optimal wind conditions at individual turbines. This capability, combined with the ANFIS controller’s adaptive response, enables the system to maintain stable voltage profiles even under highly variable wind conditions. The voltage stability remained within ±5% of the nominal values across wind speed variations from 3 m/s to 25 m/s—a performance level unmatched by previous approaches.

The power factor correction achieved in proposed system (0.95–0.98) represents a substantial improvement over conventional PI-controlled systems (0.85–0.90) and even other advanced controllers. This translates to a 42–60% reduction in reactive power requirements, which directly impacts the system efficiency and capacity utilization.

Interestingly, while other FACTS devices like those described in [

18] also provide reactive power compensation, they typically lack the fine-grained control and adaptability of DSTATCOM implementation with ANFIS. This is evidenced by the superior power factor performance and faster response characteristics of proposed system.

From an implementation perspective, the proposed approach strikes a balance between performance and complexity. While conventional PI controllers offer simplicity and lower cost, they fail to provide adequate performance in wind energy applications. Conversely, some sophisticated FACTS implementations in [

18] provide a good performance but at prohibitive complexity and cost.

The proposed ANFIS-based DSTATCOM implementation delivers superior performance with moderate complexity and cost. The decentralized architecture also offers phased implementation possibilities, allowing for gradual deployment and expansion—a practical advantage for real-world projects with budget constraints.