Design of Low-Power Vertical-Axis Wind Turbine Based on Parametric Method

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Framework

2.1. VAWT Aerodynamics

2.2. VAWT Velocities

Velocities

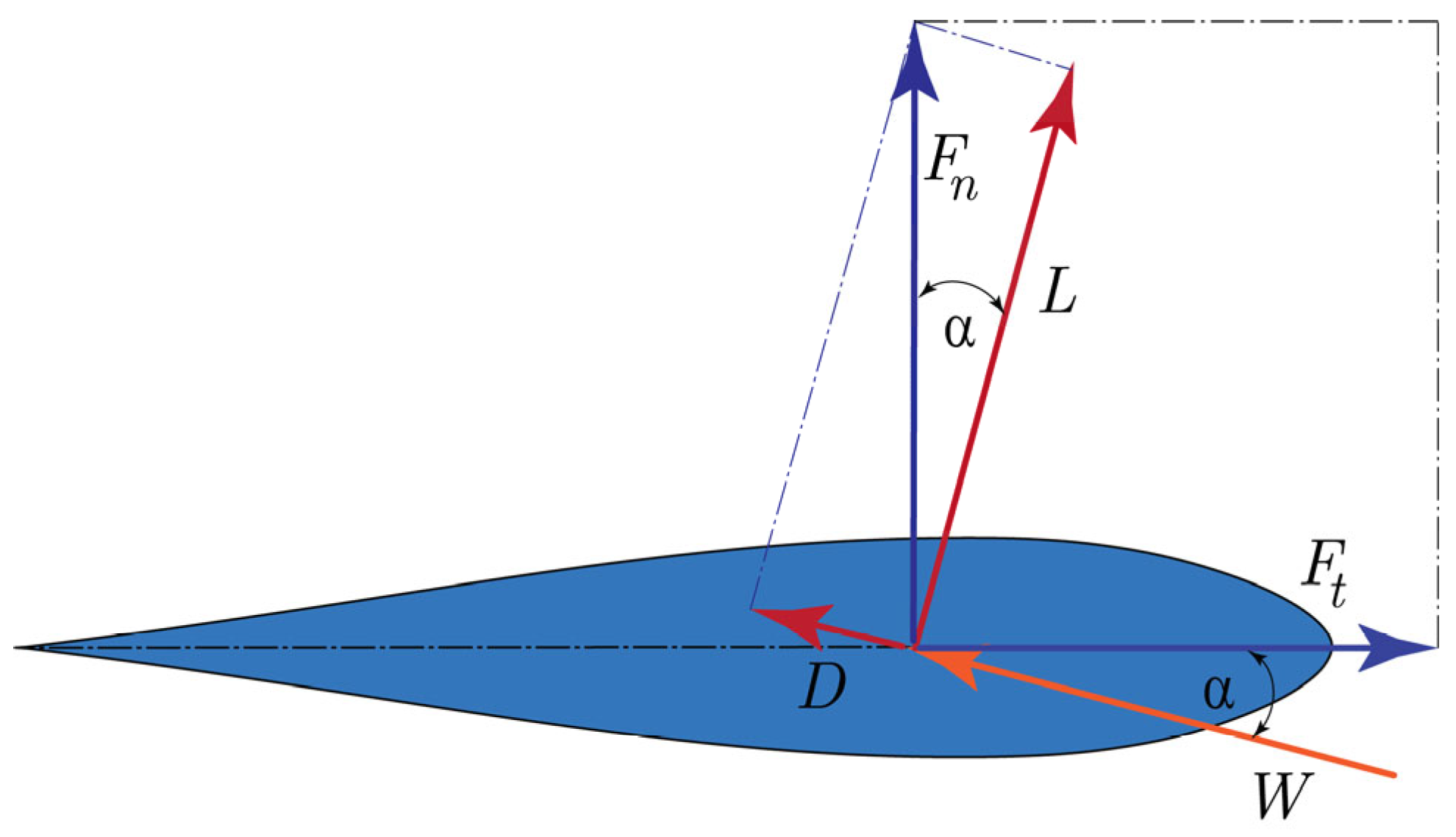

2.3. Forces Acting on the VAWT

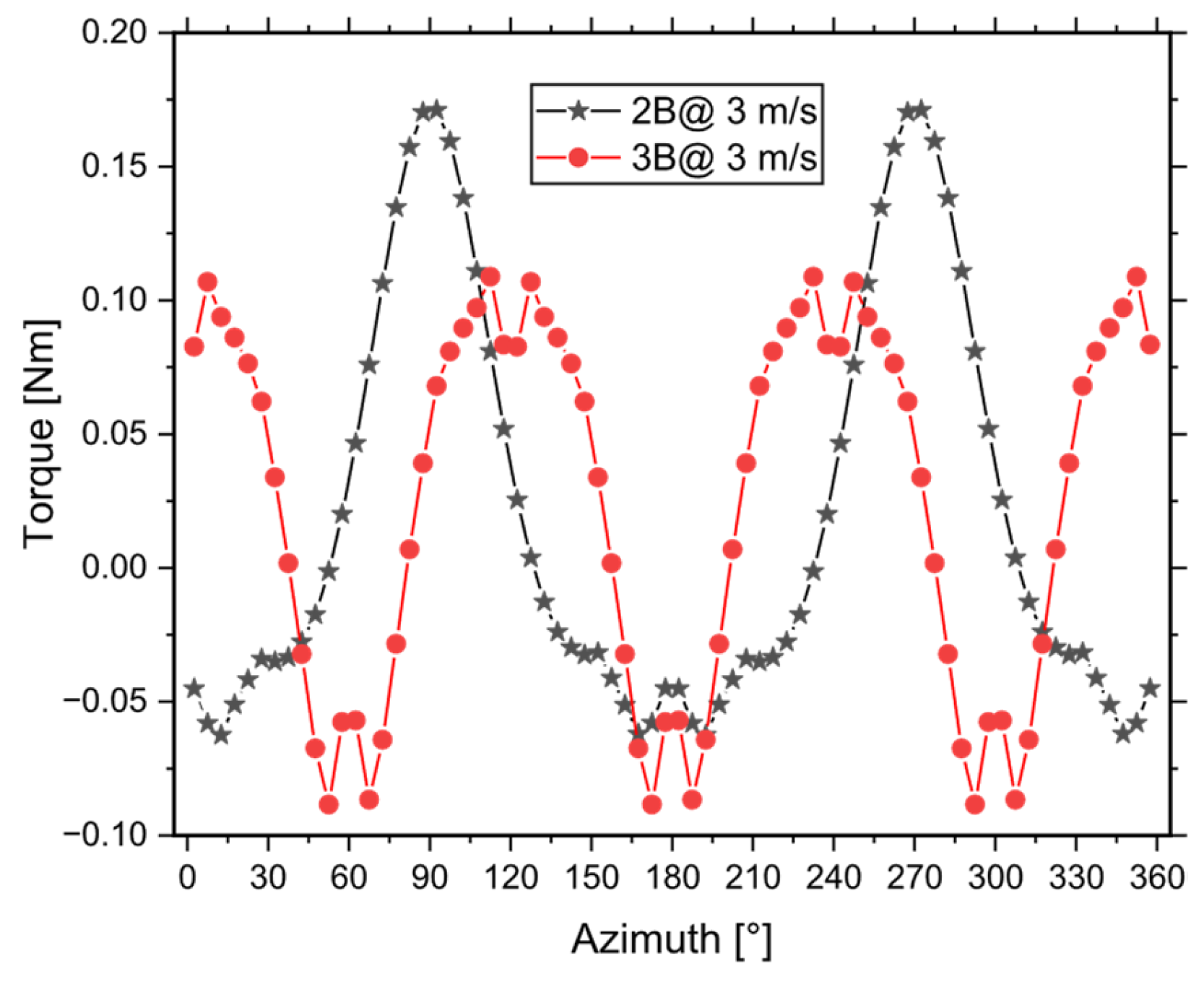

2.4. Torque

3. Development

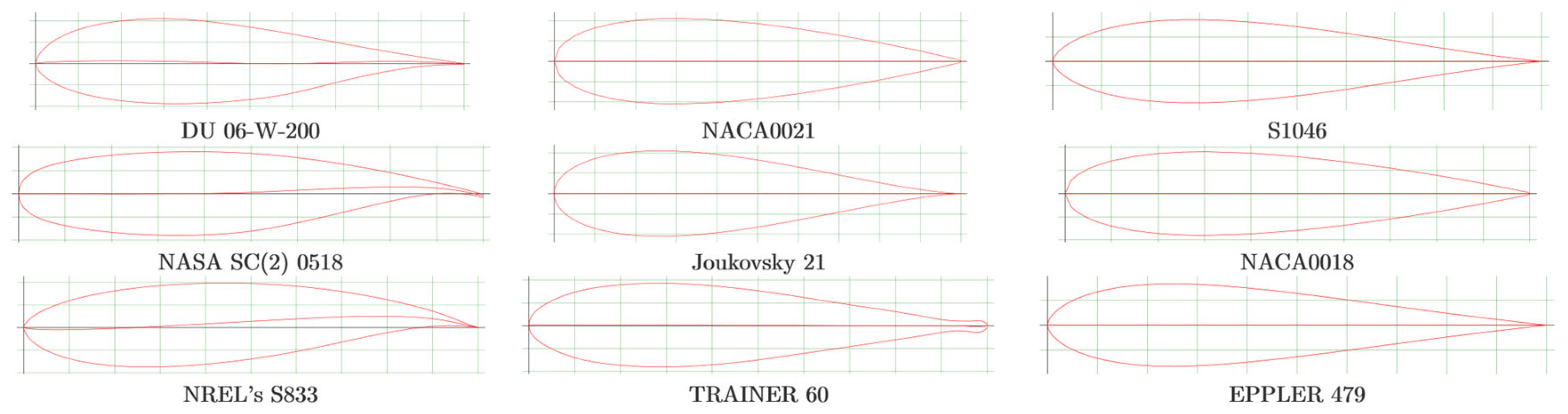

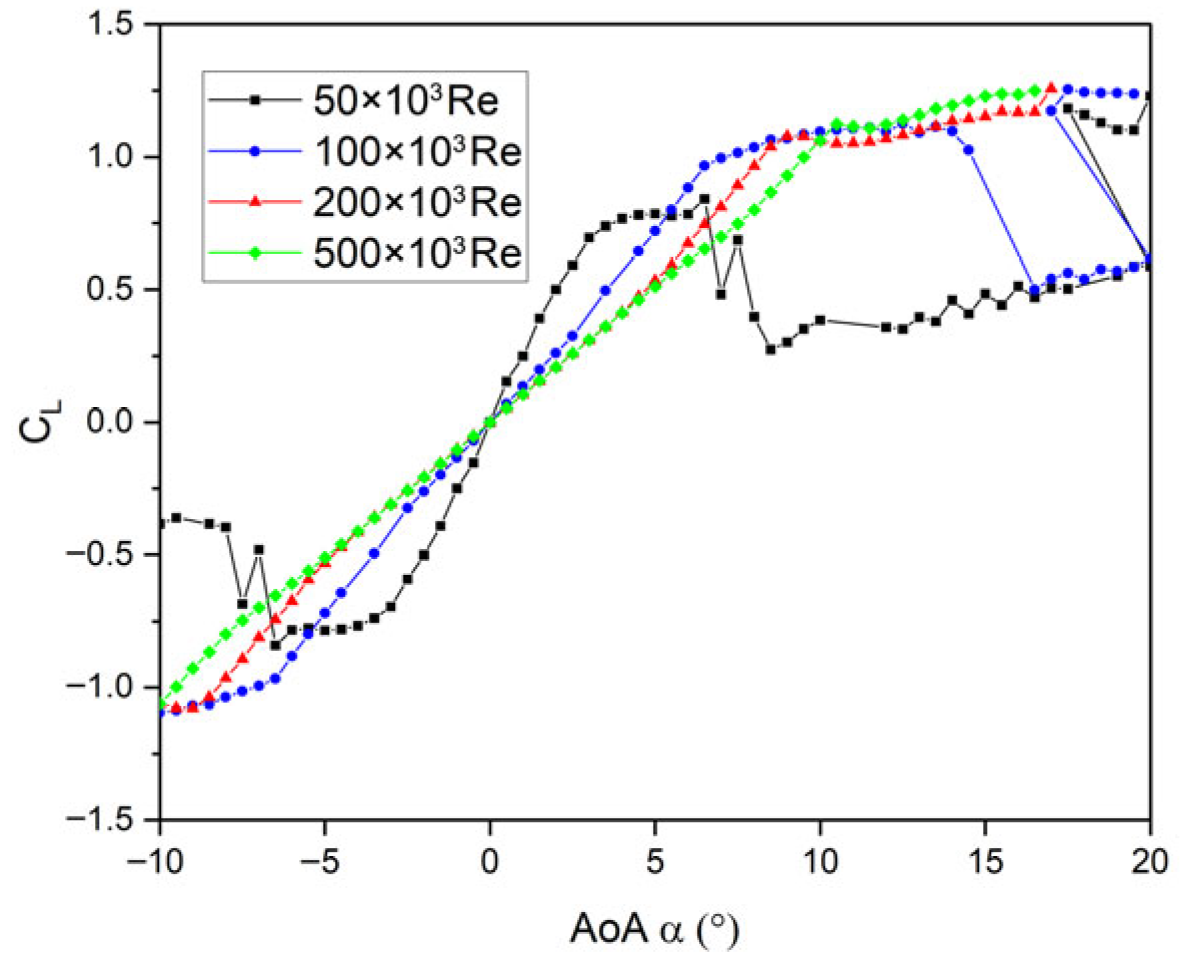

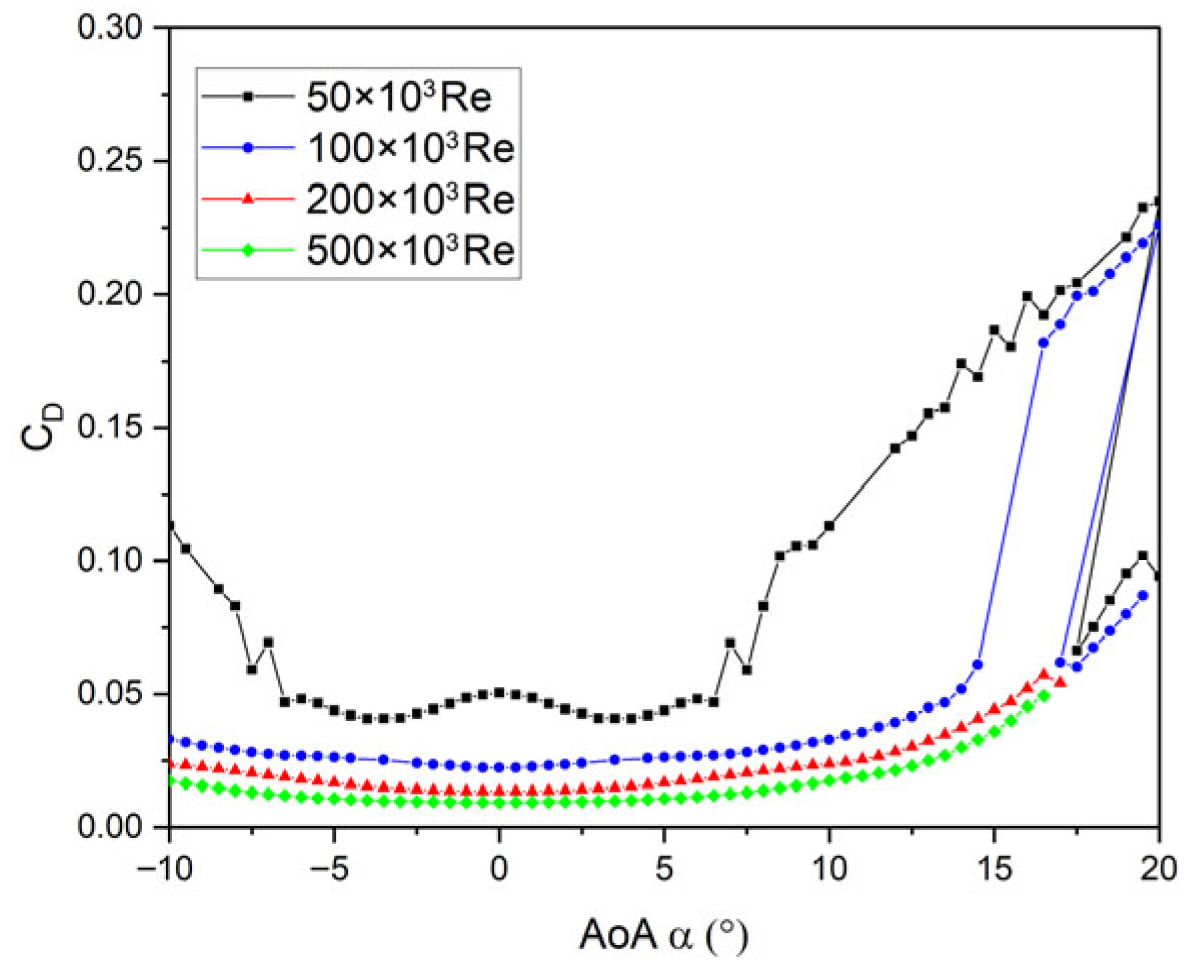

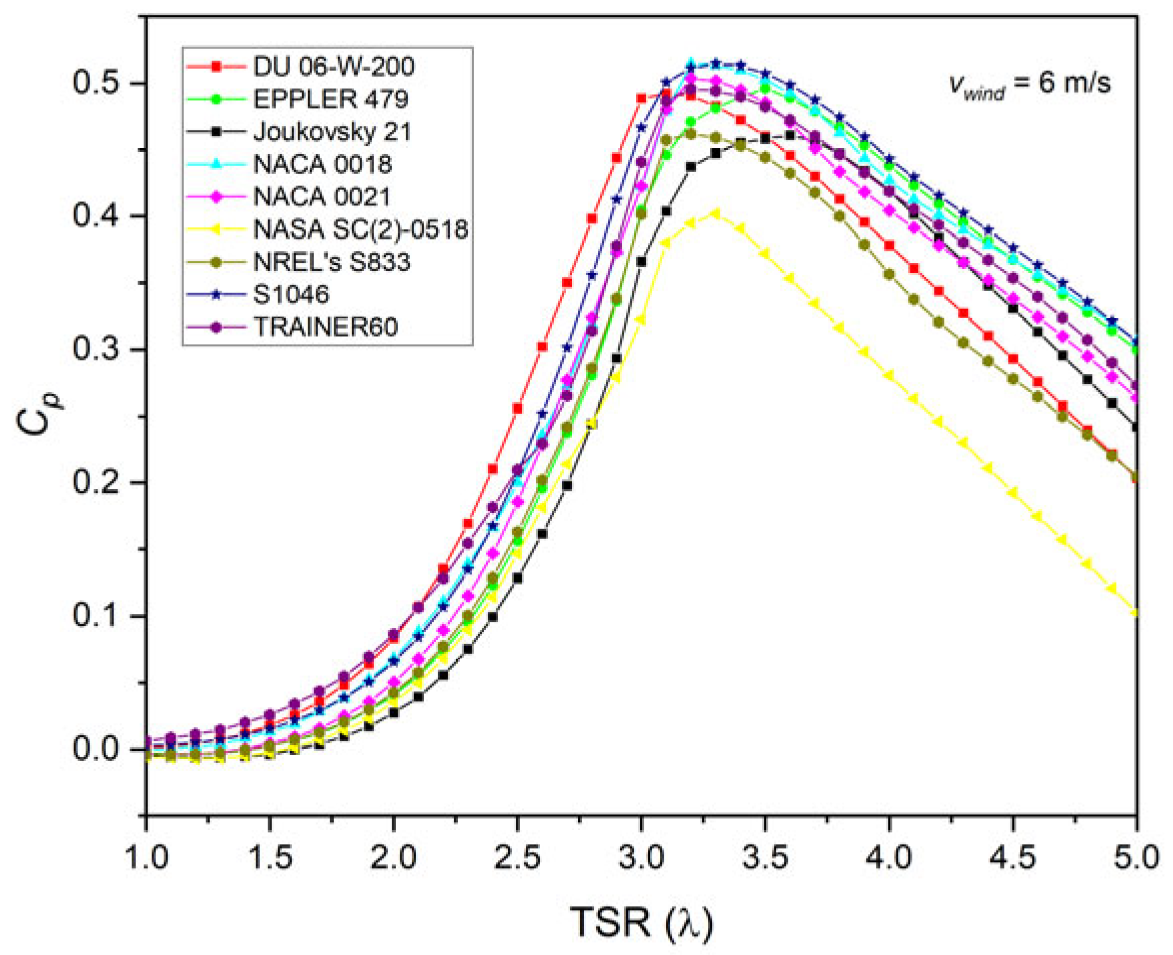

3.1. Airfoil Selection and Evaluation

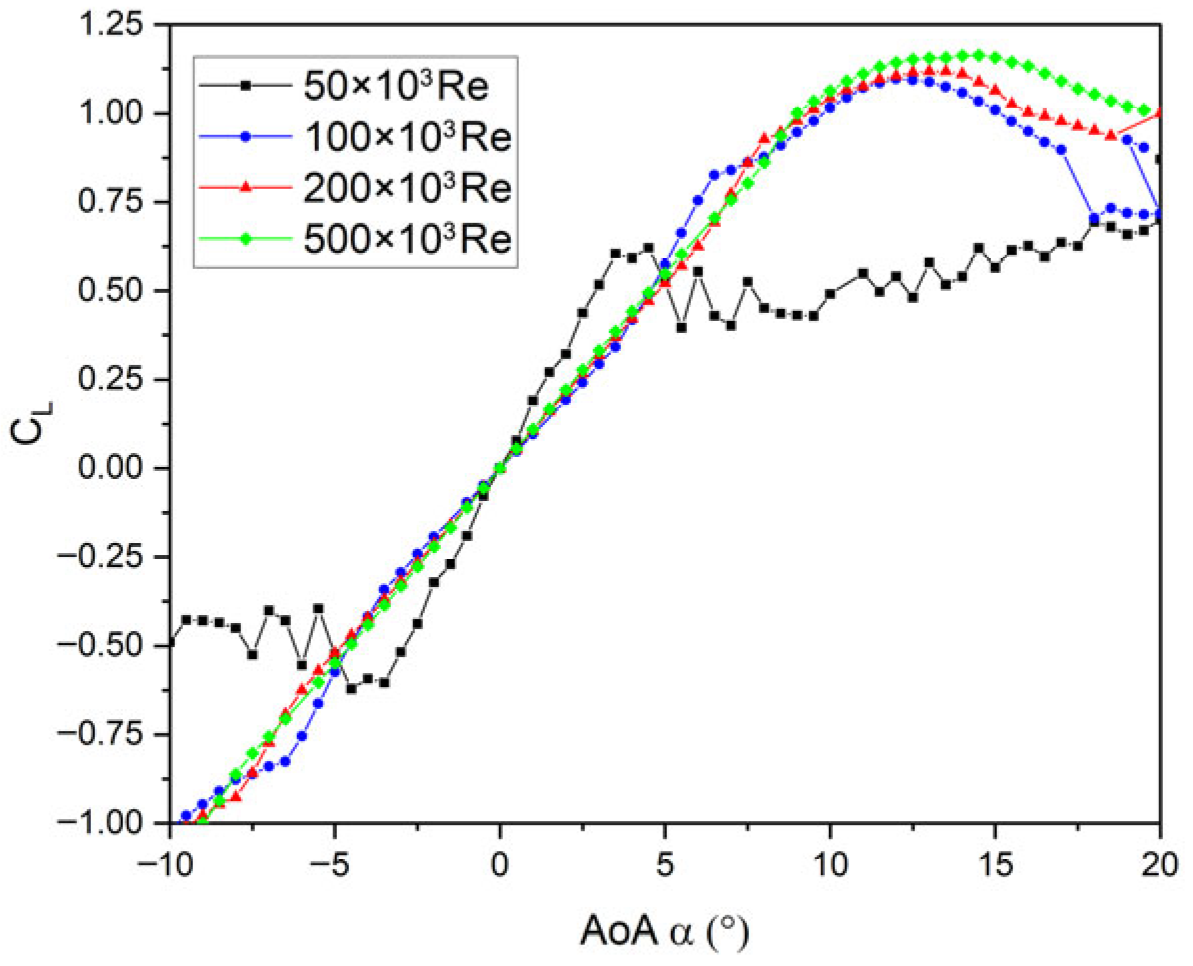

3.1.1. NACA 0021

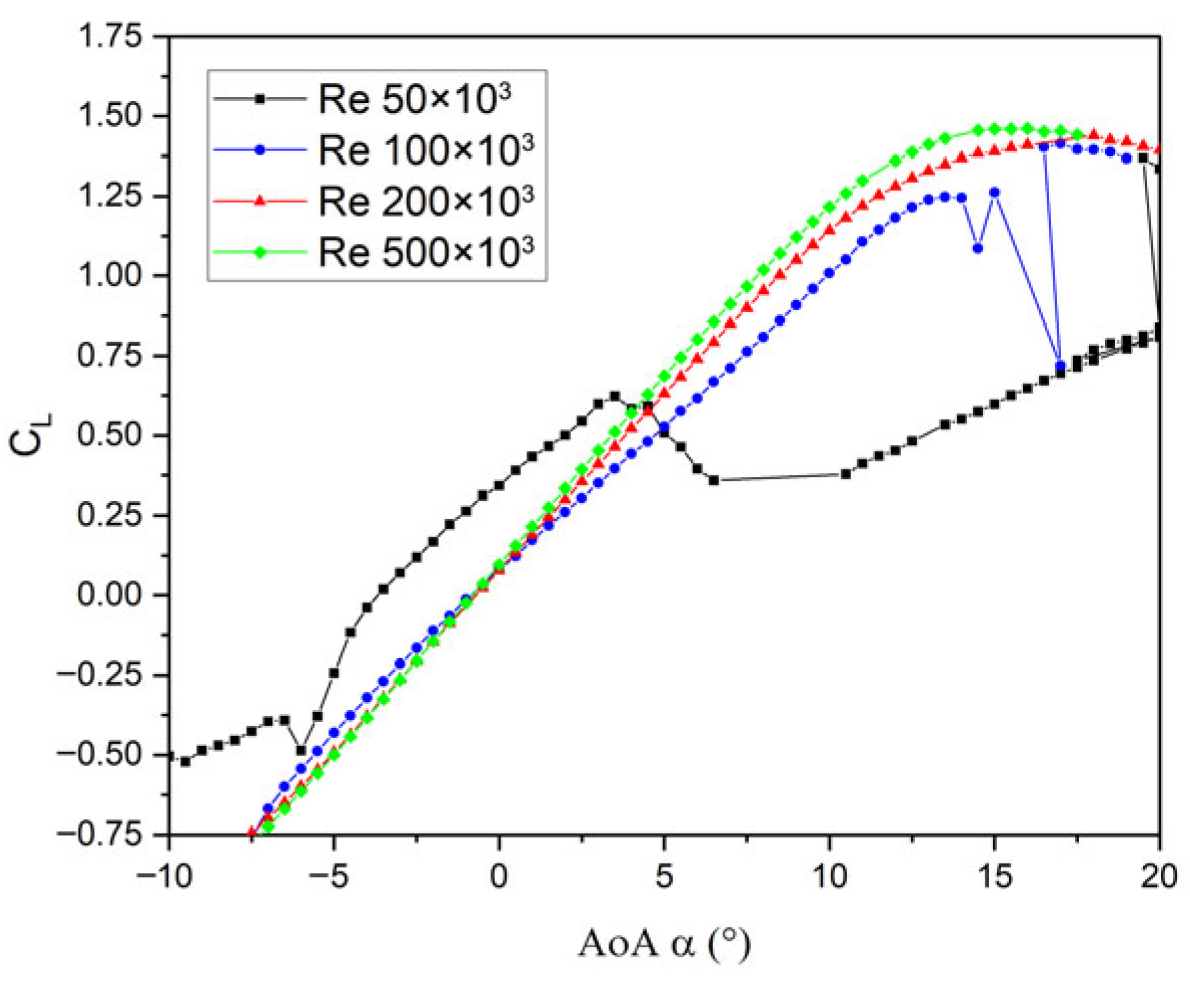

3.1.2. S1046

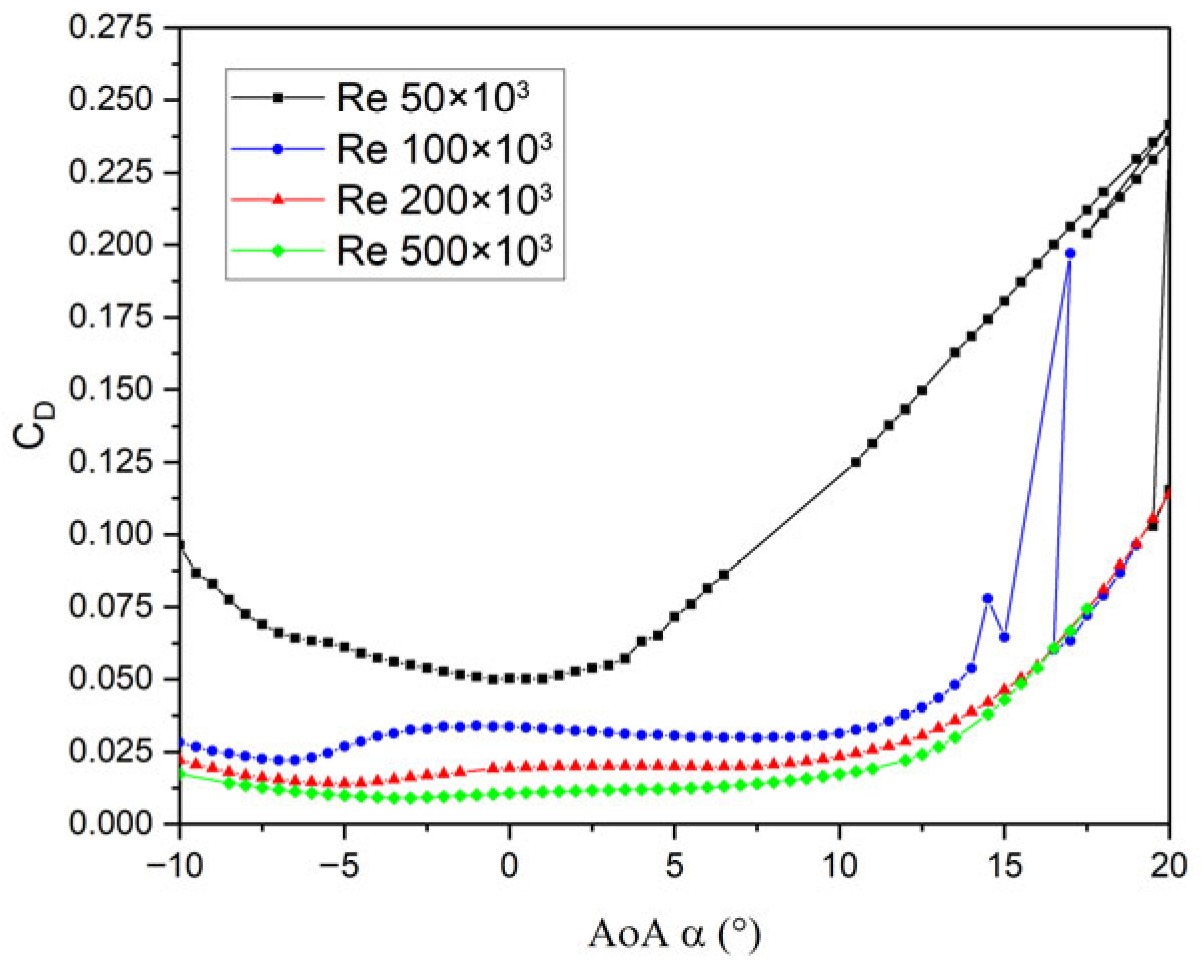

3.1.3. DU 06-W-200

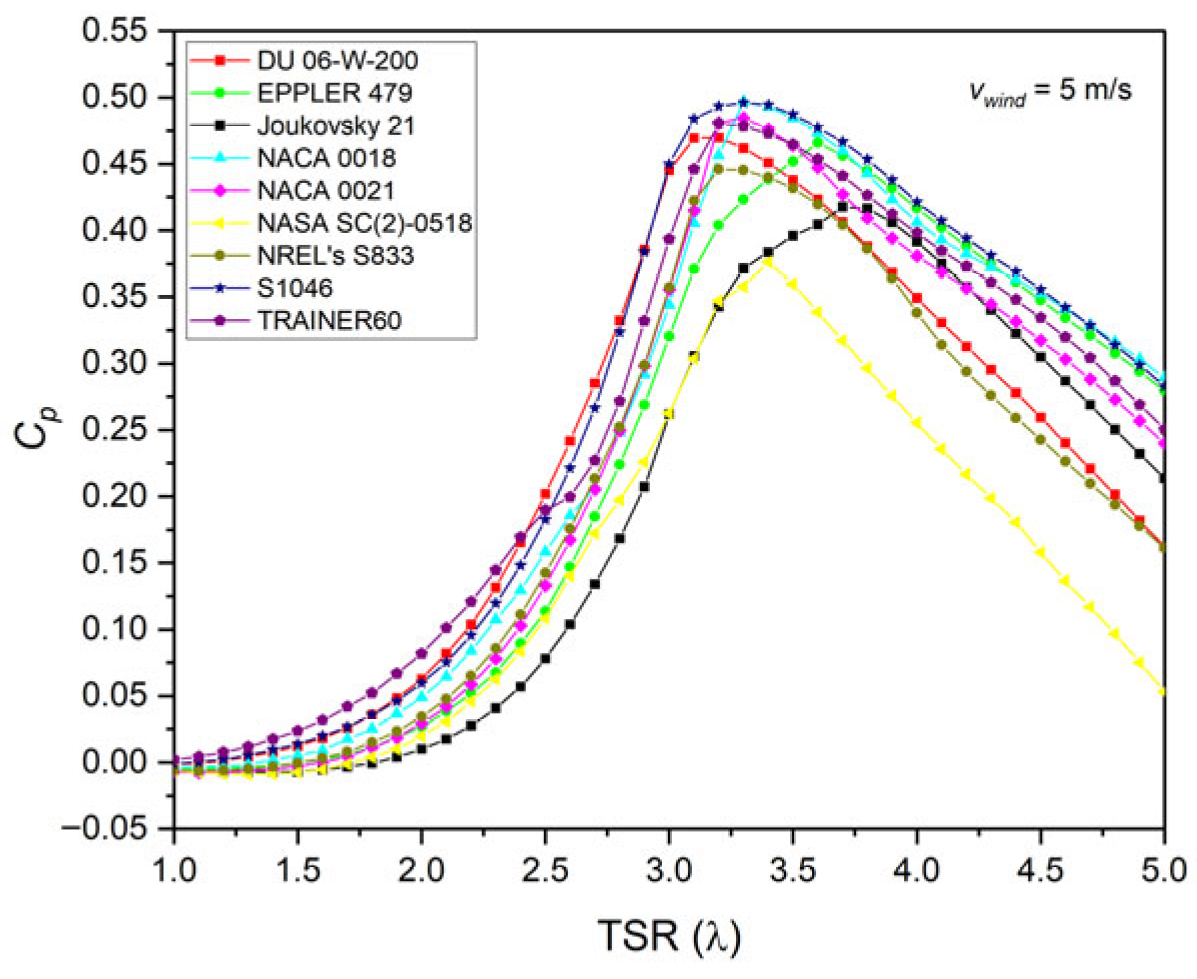

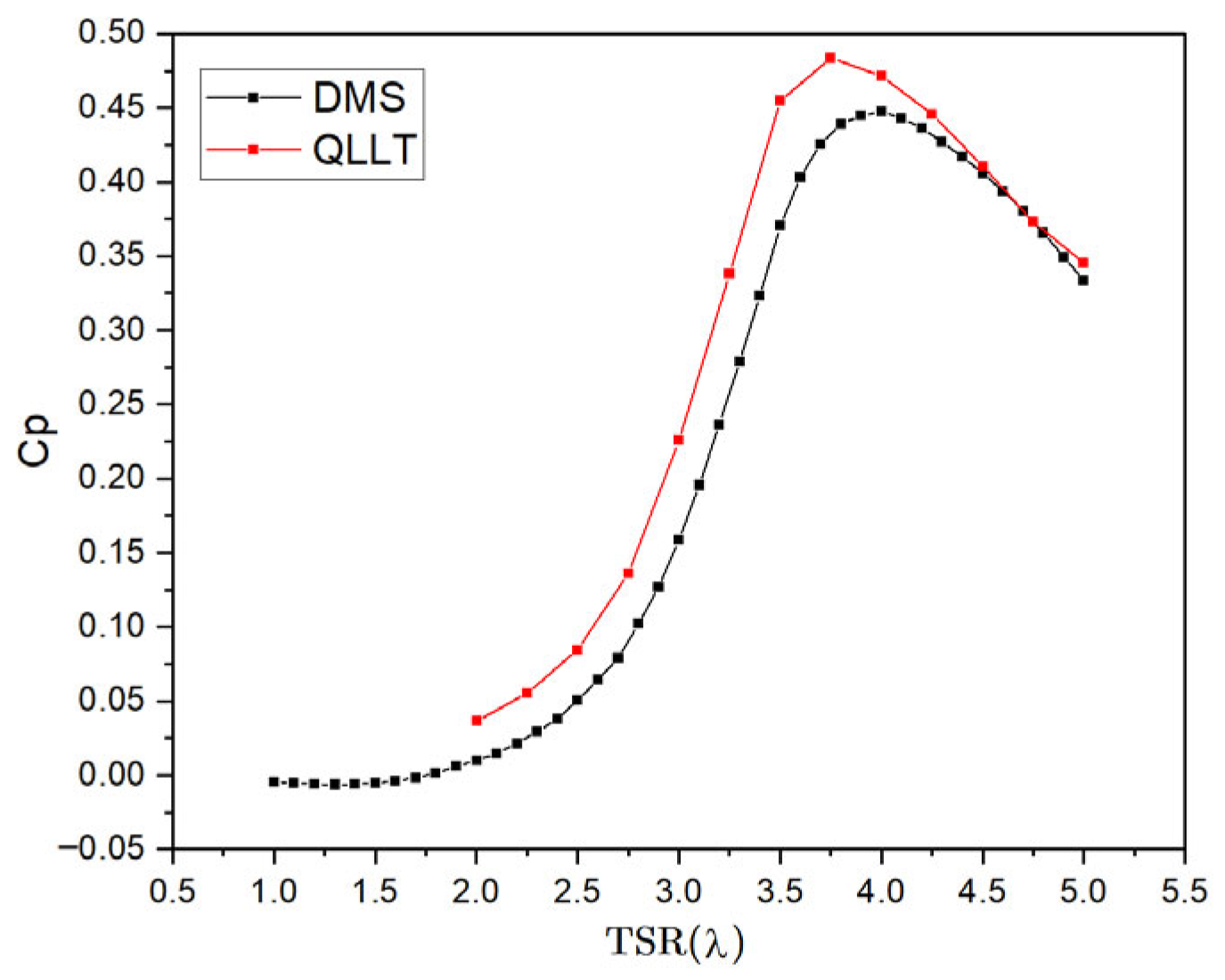

3.2. Power Coefficient Evaluation

3.3. Wind Turbine Design Parameters

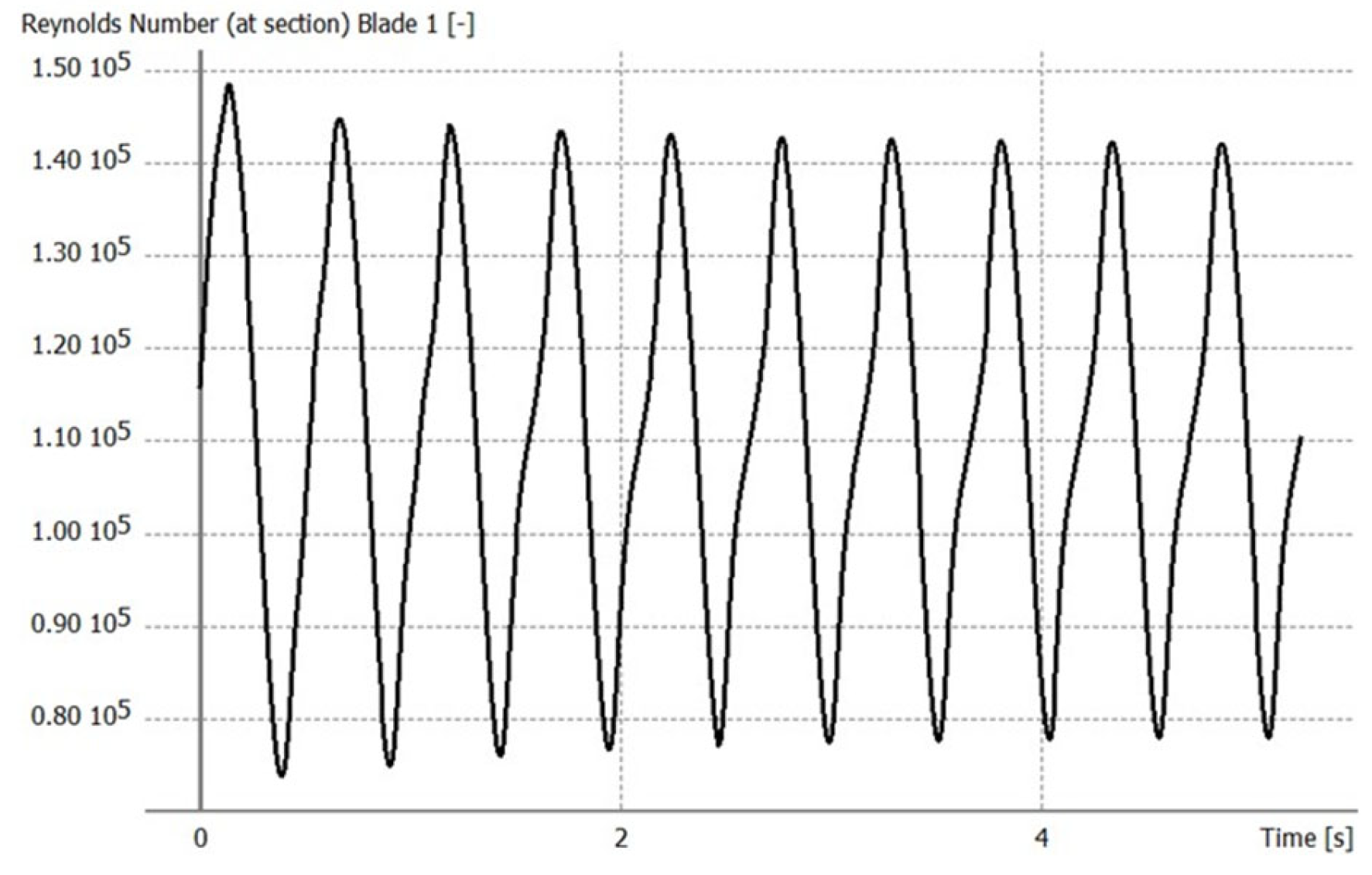

3.3.1. Qblade Configuration

3.3.2. Rotor Aspect Analysis

3.4. Description of the Solidity Analysis

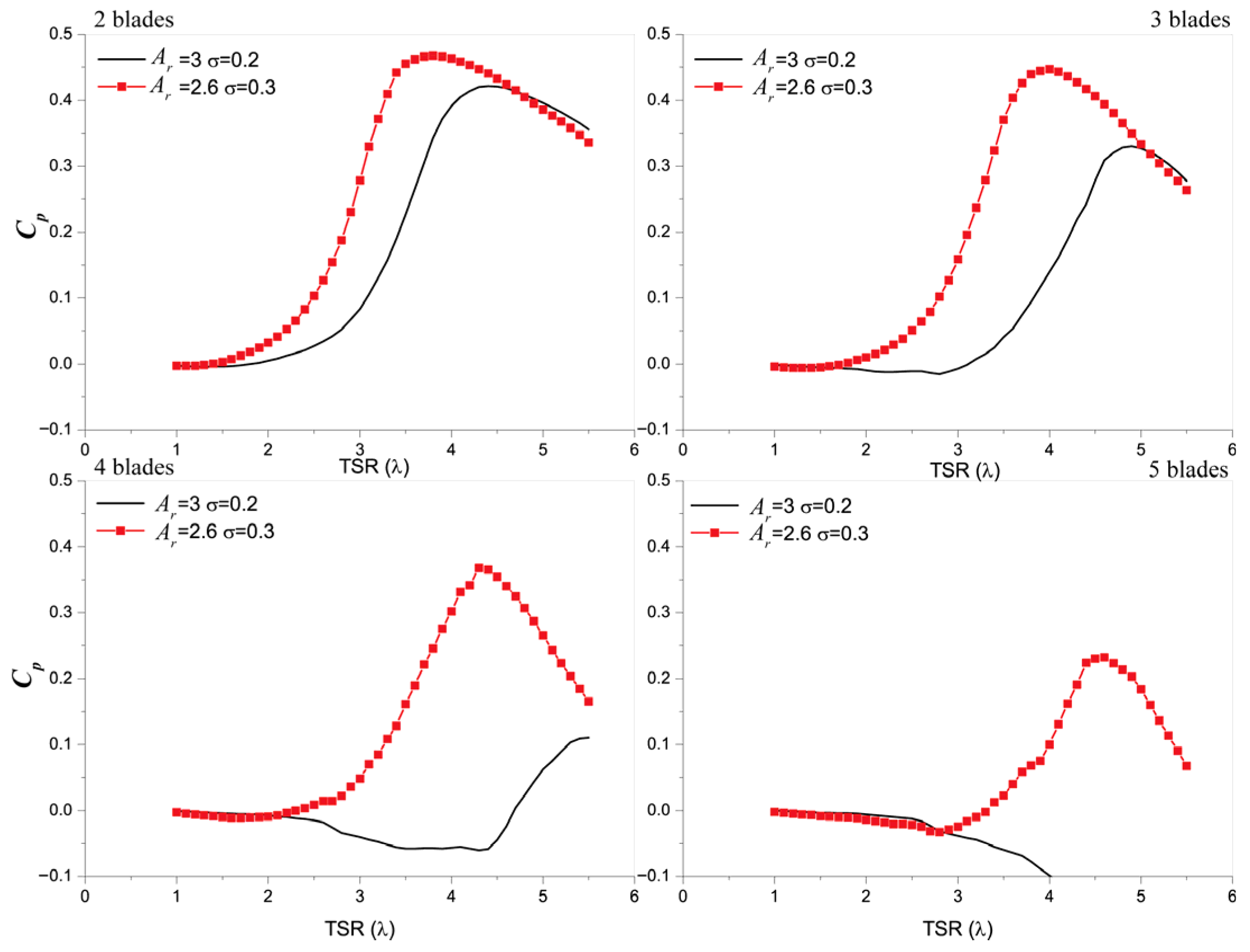

3.5. Solidity Analysis of the VAWT

3.5.1. First Stage Simulation

3.5.2. Second Stage Simulation

- ➢

- Area = 4 m2

- ➢

- Blades = 2–3

- ➢

- Solidity σ = 0.200, 0.225, 0.25, 0.275 and 0.300

- ➢

- Blade aspect ratio AR = 2.6, 2.7, 2.8, 2.9 and 3.0

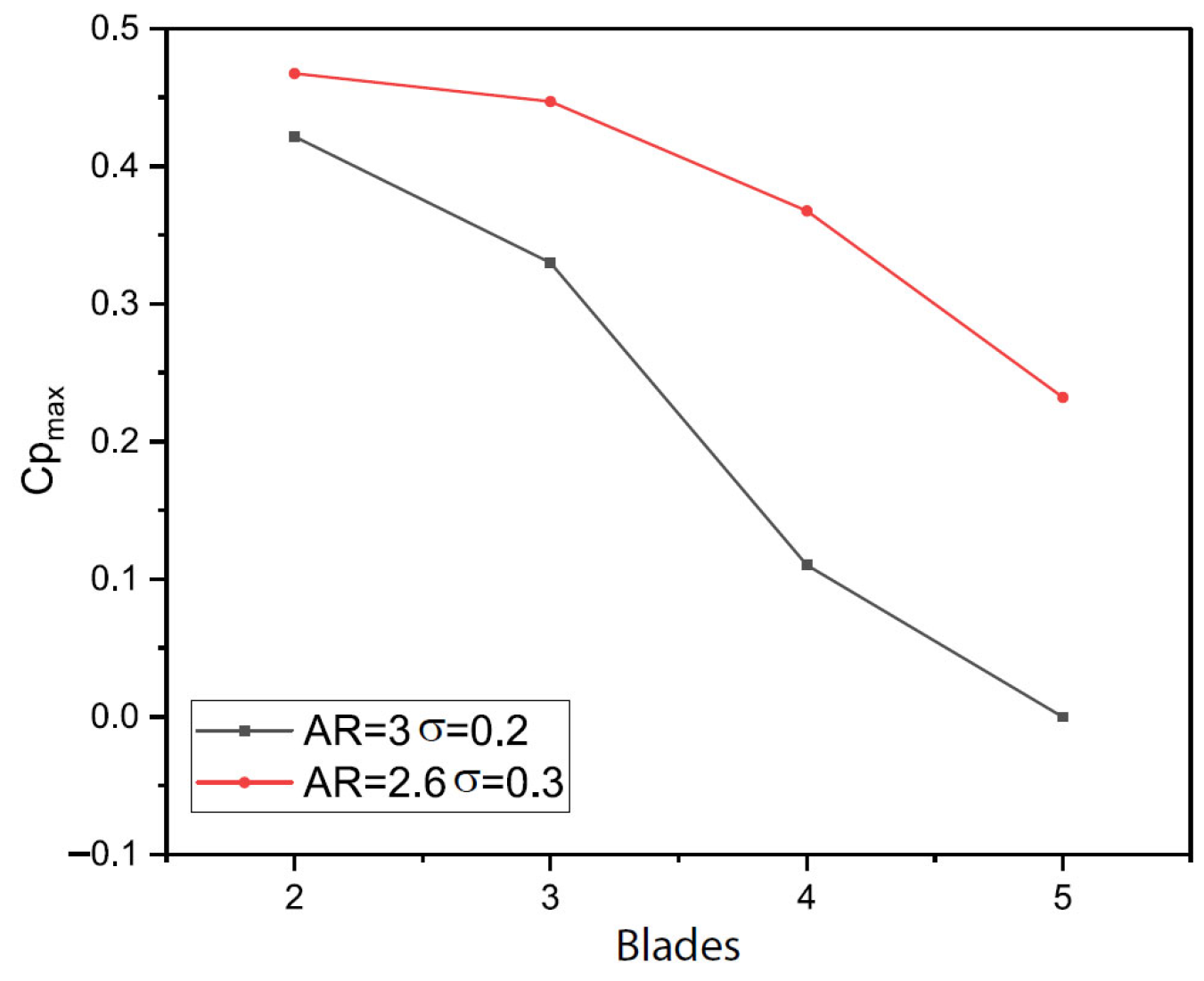

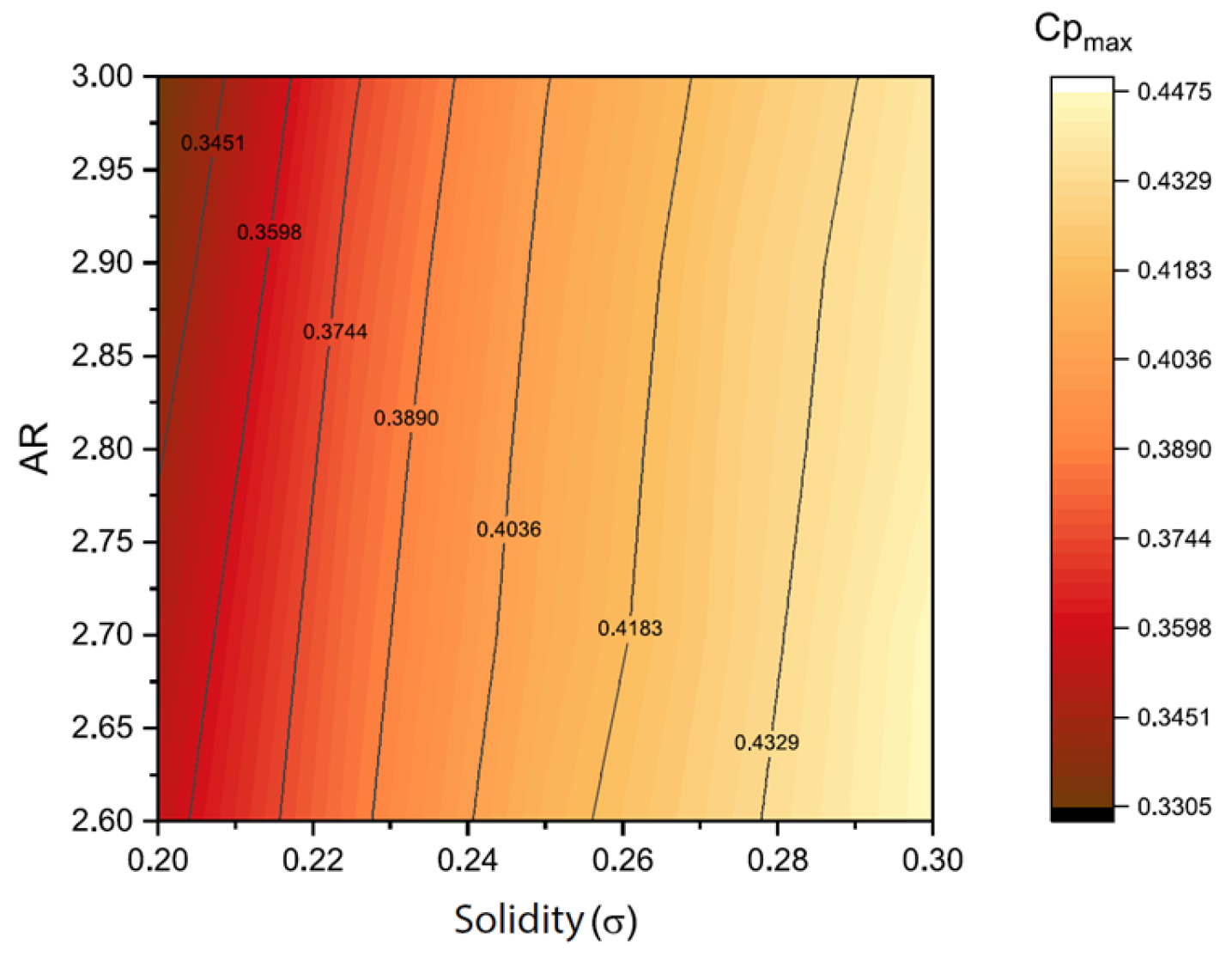

3.5.3. Two Blade VAWT

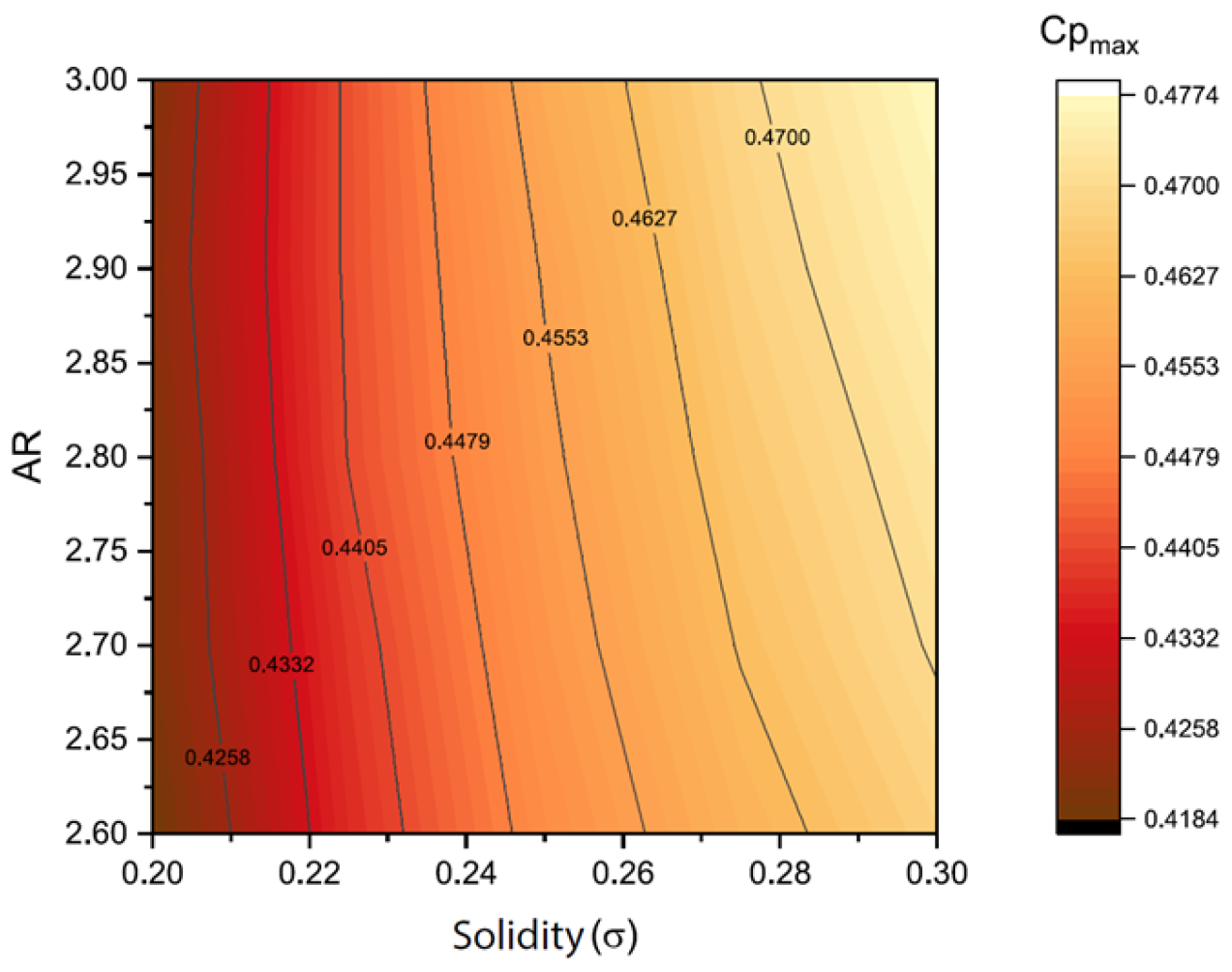

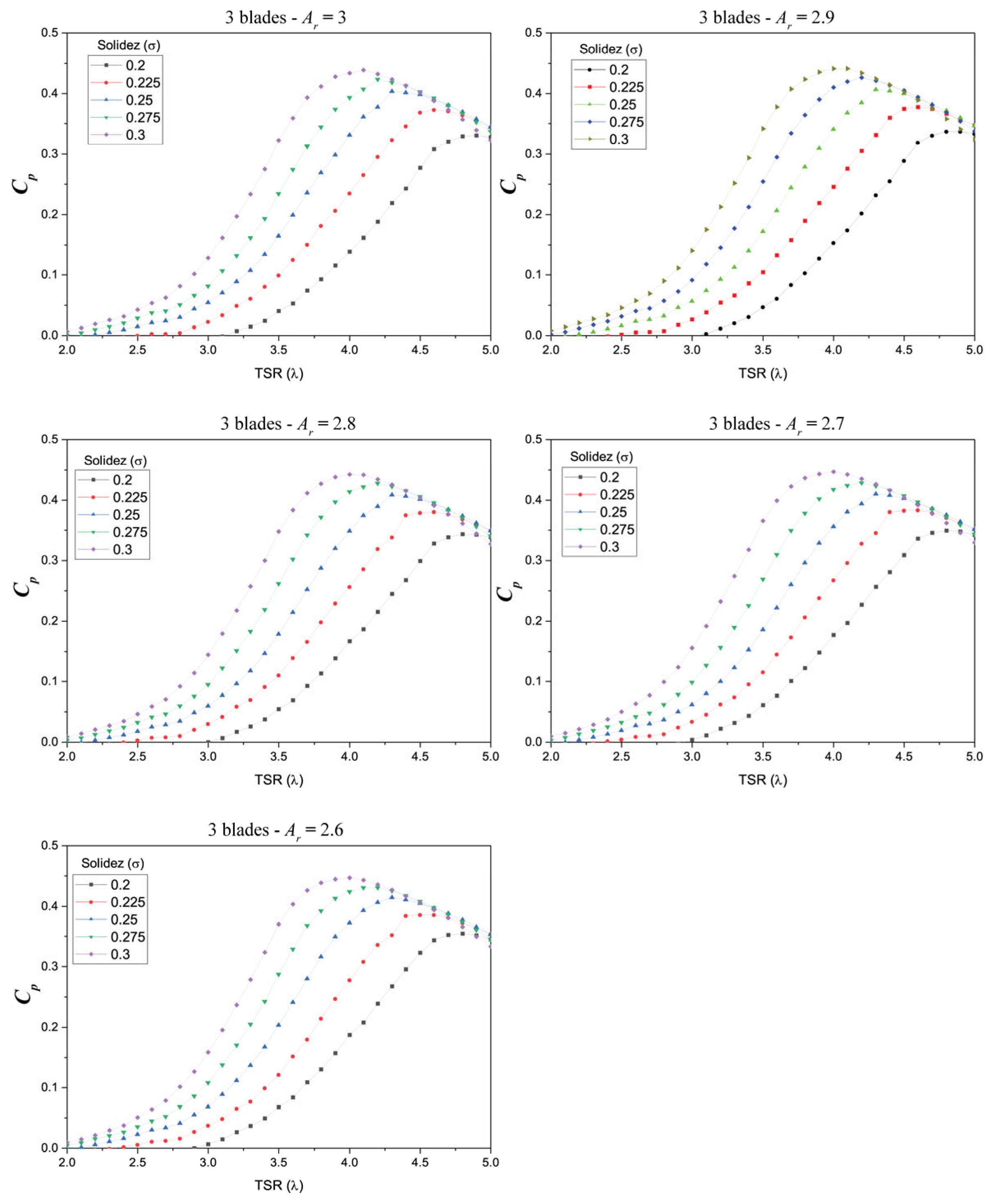

3.5.4. Three Blade VAWT

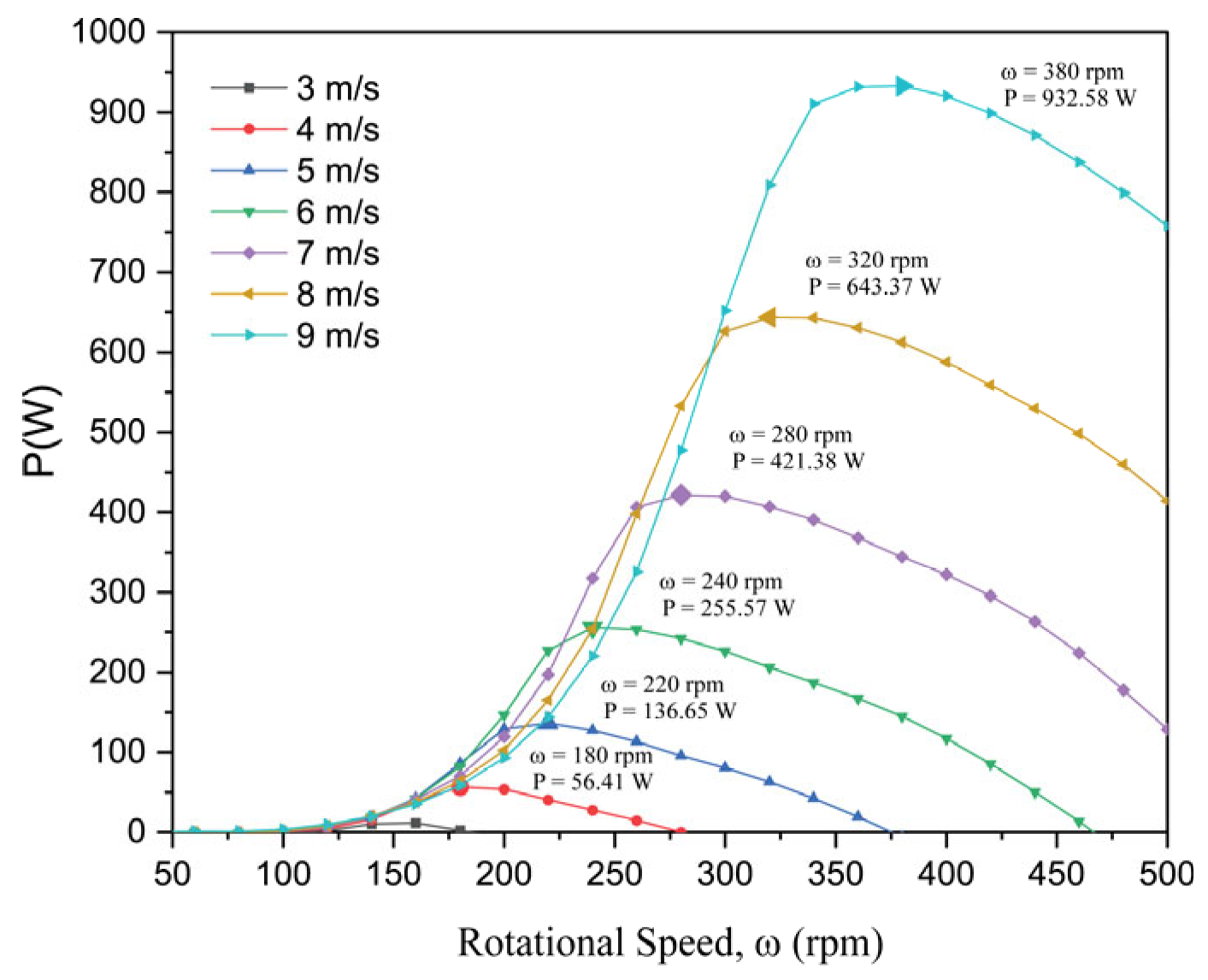

4. Analysis of Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| A | Rotor swept area (m2) |

| AR | Aspect ratio (H/R) |

| C | Airfoil chord (m) |

| CD | Drag coefficient |

| CL | Lift Coefficient |

| Cp | Power coefficient |

| D | Rotor diameter (m) |

| DMS | Double Multiple Stream tube |

| FD | Drag force (N) |

| FL | Lift force (N) |

| Fn | Normal force (N) |

| Ft | Tangential force (N) |

| H | Rotor height (m) |

| N | Number of blades |

| P | VAWT Power |

| QLLT | Qblade Lifting Line Theory |

| R | Rotor radius (m) |

| T | VAWT torque (N m) |

| vc | Chord velocity (m/s) |

| vn | Normal velocity (m/s) |

| va | Axial velocity (m/s) |

| W | Relative airflow velocity (m/s) |

| VAWT | Vertical Axis Wind Turbine |

| Greeks | |

| α | Angle of attack (°) |

| λ | Tip Speed Ratio (TSR) |

| σ | Solidity |

| θ | Azimuth angle (°) |

| ϕ | Height/Diameter ratio (H/D) |

| ω | Rotational speed (rpm) |

References

- Firdaus, R.; Kiwata, T.; Kono, T.; Nagao, K. Numerical and experimental studies of a small vertical-axis wind turbine with variable-pitch straight blades. J. Fluid Sci. Technol. 2015, 10, JFST0001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchini, A.; Ferrara, G.; Ferrari, L. Design guidelines for H-Darrieus wind turbines: Optimization of the annual energy yield. Energy Convers. Manag. 2015, 89, 690–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hand, B.; Kelly, G.; Cashman, A. Aerodynamic design and performance parameters of a lift-type vertical axis wind turbine: A comprehensive review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 139, 110699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miliket, T.A.; Ageze, M.B.; Tigabu, M.T. Aerodynamic performance enhancement and computational methods for H-Darrieus vertical axis wind turbines: Review. Int. J. Green Energy 2022, 19, 1428–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.; Ting, D.S.-K.; Fartaj, A. Design of a Special-Purpose Airfoil for Smaller-Capacity Straight-Bladed VAWT. Wind Eng. 2007, 31, 401–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirandaz, M.R.; Rezaeiha, A. Effect of airfoil shape on power performance of vertical axis wind turbines in dynamic stall: Symmetric Airfoils. Renew. Energy 2021, 173, 422–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davari, H.S.; Botez, R.M.; Davari, M.S.; Chowdhury, H. Blade height impact on self-starting torque for Darrieus vertical axis wind turbines. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2024, 24, 100814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaeiha, A.; Montazeri, H.; Blocken, B. Towards optimal aerodynamic design of vertical axis wind turbines: Impact of solidity and number of blades. Energy 2018, 165, 1129–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagharichi, A.; Zamani, M.; Ghasemi, A. Effect of solidity on the performance of variable-pitch vertical axis wind turbine. Energy 2018, 161, 753–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.A.; Duvvuri, S.; Hultmark, M. Solidity effects on the performance of vertical-axis wind turbines. Flow 2021, 1, E9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez, S. Diseño de un Microaerogenerador de Eje Vertical. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Ciudad Universitaria, Mexico, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández, M.R.; de la Torre, J.; Contreras, J.L.N.; Guzman, G.R.; Martínez, J.R.; Ruedas, F.B. Diseño y construcción de aerogenerador de eje horizontal de 1 kW. Rev. Difusión Científica Ing. Tecnol. 2012, 5, 51–59. [Google Scholar]

- García, L.; Treviño, A.; Lara, D.; Romero, G.; Ramírez, L.; Romero, L. Desarrollo de una plataforma experimental para una nueva configuración de un aerogenerador de eje vertical. In Proceedings of the SOMI Congreso de Instrumentacion XXIX Edicion, Puerto Vallarta, Mexico, 29–31 October 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Nugraha, A.D.; Garingging, R.A.; Wiranata, A.; Sitanggang, A.C.; Supriyanto, E. Comparison of “Rose, Aeroleaf, and Tulip” vertical axis wind turbines (VAWTs) and their characteristics for alternative electricity generation in urban and rural areas. Results Eng. 2025, 25, 103885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwell, B.F.; Sheldahl, R.E.; Feltz, L.V. Wind Tunnel Performance Data for the Darrieus Wind Turbine with NACA 0012 Blades; Sandia Laboratories Energy Report: Albuquerque, NM, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Canul, F.; Rosado-Hau, N.; Aguilar, J.O.; Becerra-Núñez, G.; Jaramillo, O.A. Diseño de un rotor Darrieus tipo Phi para aerogeneradores de baja potencia. Ing. Investig. Tecnol. 2024, 25, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.; Ting, D.S.-K.; Fartaj, A. Aerodynamic models for Darrieus-type straight-bladed vertical axis wind turbines. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2008, 12, 1087–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjiu, W.; Marnoto, T.; Mat, S.; Ruslan, M.H.; Sopian, K. Darrieus vertical axis wind turbine for power generation I: Assessment of Darrieus VAWT configurations. Renew. Energy 2015, 75, 50–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claessens, M.C. The Design and Testing of Airfoils for Application in Small Vertical Axis Wind Turbines. Master’s Thesis, Delft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, C.S.; Geurts, B. Aerofoil optimization for vertical-axis wind turbines. Wind Energy 2015, 18, 1371–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M.H. Performance investigation of H-rotor Darrieus turbine with new airfoil shapes. Energy 2012, 47, 522–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, Y.H.; Badah, M.R. Design vertical axis wind turbine rotorblade and simulation in (DMS) approach by QBlade software. AIP Conf. Proc. 2023, 2593, 020001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davari, H.S.; Botez, R.M.; Davari, M.S.; Chowdhury, H.; Hosseinzadeh, H. Numerical and experimental investigation of Darrieus vertical axis wind. Results Eng. 2024, 24, 103240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNaugthon, J.; Billard, F.; Revell, A. Turbulence modelling of low Reynolds number flow effects around a vertical turbine at a range of tip-speed ratios. J. Fluidos Structires 2014, 47, 121–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Maeda, T.; Kamada, Y.; Murata, J.; Shimizu, K.; Ogasawara, T.; Nakai, A.; Kasuya, T. Effect of solidity on aerodynamic forces around straight-bladed vertical axis wind turbine by wind tunnel experiments (depending on number of blades). Renew. Energy 2016, 96, 928–939. [Google Scholar]

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Height (m) | 2.6 |

| Chord (m) | 0.1 |

| Radius (m) | 1 |

| Solidity (-) | 0.3 |

| Number of blades | 3 |

| H/R ratio | 2.6 |

| No. of Blades | Cmin | Cmax |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | ||

| 3 | ||

| 4 | ||

| 5 |

| Number of Blades | Radius (m) | |

|---|---|---|

| Rmin = 0.81 | Rmax = 0.877 | |

| 2 | C = 0.081 m | C = 0.131 m |

| 3 | C = 0.054 m | C = 0.087 m |

| 4 | C = 0.040 m | C = 0.065 m |

| 5 | C = 0.032 m | C = 0.052 m |

| Ar | Solidity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.200 | 0.225 | 0.250 | 0.275 | 0.300 | |

| 3 | 0.081 | 0.091 | 0.102 | 0.112 | 0.122 |

| 2.9 | 0.083 | 0.093 | 0.103 | 0.114 | 0.124 |

| 2.8 | 0.084 | 0.095 | 0.105 | 0.116 | 0.126 |

| 2.7 | 0.086 | 0.096 | 0.107 | 0.118 | 0.129 |

| 2.6 | 0.087 | 0.098 | 0.109 | 0.120 | 0.131 |

| Ar | Solidity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.200 | 0.225 | 0.250 | 0.275 | 0.300 | |

| 3 | 0.054 | 0.061 | 0.068 | 0.074 | 0.081 |

| 2.9 | 0.055 | 0.062 | 0.069 | 0.076 | 0.083 |

| 2.8 | 0.056 | 0.063 | 0.070 | 0.077 | 0.084 |

| 2.7 | 0.057 | 0.064 | 0.071 | 0.078 | 0.086 |

| 2.6 | 0.058 | 0.065 | 0.073 | 0.080 | 0.087 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Díaz-Canul, F.; Aguilar, J.O.; Rosado-Hau, N.; Simá, E.; Jaramillo, O.A. Design of Low-Power Vertical-Axis Wind Turbine Based on Parametric Method. Wind 2025, 5, 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/wind5040035

Díaz-Canul F, Aguilar JO, Rosado-Hau N, Simá E, Jaramillo OA. Design of Low-Power Vertical-Axis Wind Turbine Based on Parametric Method. Wind. 2025; 5(4):35. https://doi.org/10.3390/wind5040035

Chicago/Turabian StyleDíaz-Canul, F., J. O. Aguilar, N. Rosado-Hau, E. Simá, and O. A. Jaramillo. 2025. "Design of Low-Power Vertical-Axis Wind Turbine Based on Parametric Method" Wind 5, no. 4: 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/wind5040035

APA StyleDíaz-Canul, F., Aguilar, J. O., Rosado-Hau, N., Simá, E., & Jaramillo, O. A. (2025). Design of Low-Power Vertical-Axis Wind Turbine Based on Parametric Method. Wind, 5(4), 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/wind5040035