Abstract

Healthcare organisations in the United Kingdom must comply with national standards for food and drink, including sustainable sourcing and minimisation, mitigation, and management of food waste. Despite this, an estimated one in six plates of food served in hospitals are wasted daily, producing 12% of the UK’s food waste, equating to 6% of carbon dioxide emissions (CO2e) nationally, and a waste-management cost of GBP 230 m per annum. Within healthcare, there is a move towards the implementation of “plant-based diets by default” to reduce the environmental impact, improve nutritional outcomes, and reduce costs. However, plant-based diets are often perceived as being difficult to prepare by caterers, less enjoyable, and potentially resulting in more food waste. We conducted a scoping review to examine the influence of the social, medical, and physical environment on food intake during inpatient admission to a mental health hospital. Fourteen studies were included. We identified five critical knowledge areas: (i) food and socio-cultural environment, (ii) evidence-based measures and strategies to reduce food waste, (iii) economic food environment, (iv) inevitability of weight gain, and (v) applications of theoretical models for behaviour change. Future research should explore the development of a behaviour-change framework inclusive of training, education, and goal-setting components for staff, patients, and visitors.

1. Introduction

The goal of the Paris Agreement (2015), a legally binding international treaty, is to limit global warming to well below 2 °C compared with pre-industrial levels. Despite international commitment to the multilateral climate change process, it is anticipated that global temperatures will reach and exceed the 1.5 °C threshold by 2030 and 2 °C by 2050 [1]. Increasing global temperatures are predicted to have an irrevocable impact on the natural world as well as humankind. Rising temperatures are likely to lead to animal and plant extinctions, water and crop failures leading to rising food prices, poverty, famine, and extreme weather events resulting in mass displacement [2]. Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions are responsible for global warming and climate change [3]. Estimates of GHG emissions by economic sectors indicate that electricity and heat production account for 25%, industry for 21%, agriculture, forestry, and other land use for 24%, transportation for 14%, buildings for 6%, and other sources for 10% [4,5,6,7]. The healthcare sector, despite its dedication to enhancing health outcomes, plays a considerable role in the climate crisis, contributing 4.4% of global net emissions and ranking as the fifth-largest annual emitter of GHGs [8], with the United States, China and the European Union/United Kingdom (UK) comprising 56% of the total healthcare climate footprint [9]. Climate change is impacting the most vulnerable societies including those in the Global South, where existing adaptations may be insufficient to cope with the effect of rising temperatures on agriculture and water availability, leading to biodiversity loss and irrevocable changes to ecosystem structures [10,11]. The healthcare industry’s overall influence on the climate emergency is complex and significant, with emissions arising from energy use, transportation, waste production, and the manufacturing of pharmaceuticals and medical devices [12]. The sector’s dependence on fossil fuels and inadequate disposal practices for medications and medical waste further intensify environmental harm. Moreover, emissions from the global food system, food including medical nutrition ingredients, and medical supplies account for one-third of all human-generated GHG emissions, contributing to deforestation and loss of biodiversity, while chemical pollutants threaten water and soil quality [4,5,6,7].

Within the UK, the health and social care sector represents 6.3% of the total national carbon dioxide emissions (CO2e) [13]. National Health Service (NHS) hospitals must comply with national standards for healthcare food and drink, which include improving sustainable sourcing of foods and reducing food waste [14]. Food waste is a significant contributor to GHG emissions, including CO2 and methane [15]. Food waste occurs at every level of the supply chain; components associated with production (including water usage), processing, transportation, preparation, and storage of discarded food are also wasted [16,17]. With one in six plates of hospital food wasted [18], approximately 50% of the total waste generated in a ward environment comes from food [16,17]. Despite the use of food and drink standards, it is estimated the 1297 NHS hospitals and 515 private hospitals produce 12% of the total food waste generated in the UK. This equates to 1.1 million tonnes of food waste per annum [19], producing 1543 ktCO2e, approximately 6% of total NHS annual emission per annum [18], with NHS waste management costs of GBP 230 m per annum [19].

Numerous factors influence food consumption in hospitals, shaping both what is eaten and discarded. These factors include (i) food quality—encompassing aesthetic and sensory attributes such as texture, smell, colour, taste, and temperature; (ii) food quantity—the portion size of meals; (iii) ordering/service model—including the ability to accommodate individual preferences, system automation, and the time between meal ordering and delivery; (iv) quality assurance and control mechanisms—such as food waste audits; (v) dining environment—factors related to where and how meals are consumed; (vi) mealtime assistance—support available to patients during meals; and (vii) staff knowledge and training—ensuring that healthcare staff are equipped to promote adequate food intake and minimize waste [20,21,22,23,24]. Food waste may also serve as a proxy for declining nutritional status, impacting length of hospital stay [25,26]. Nutritional status may be negatively impacted by mental illness, because of the disease itself as well as treatment, including medications that have a deleterious impact on appetite dysregulation, sedation, and motivation, along with social and health determinants that increase the risk of nutrition-related diseases (i.e., obesity) [27]. In contrast, some severe mental health disorders such as schizophrenia may increase the risk of undernutrition, before and during admission to psychiatric hospital, with associated risk factors including lengthy hospital stay, food insecurity, and disordered eating [27,28], and extrapyramidal effects of medication on body composition (e.g., sarcopenia) [29]. As a result, individuals admitted to acute inpatient wards in psychiatric hospitals are at further risk of overnutrition, undernutrition, and micronutrient deficiencies [27,28,29,30,31]. High levels of food waste are associated with reduced energy and protein intake, impacting malnutrition-related complications and length of hospital stay [32,33], and significantly increasing mortality risk by two-fold if 25% or less of food served is eaten [34]. Food waste in hospitals is multifactorial, with associated factors including the following: (1) clinical issues (i.e., poor appetite, medication), special diets, changes in sense of smell, dysphagia, cognition and long length of stay; (2) food and menu issues—food quality, menu choice (i.e., lack of culturally appropriate food), food presentation; (3) service issues—physical problems, plated food systems, ordering problems, e.g., insufficient information of food or dietary requirements; (4) environmental issues—inappropriate mealtimes, insufficient time to eat, meal interruptions, and ward environment [32].

Meeting the dietary and nutritional needs of individuals requiring hospital care, along with those of visitors and staff, is challenging [35], with the triple burden of malnutrition (i.e., over-, undernutrition, and micronutrient deficiency) commonplace amongst those admitted to hospitals [28,35,36,37,38,39,40]. For individuals with severe mental illness, nutritional status may be further affected by longer hospital admission [39,40] and making changes to hospital food service is difficult, particularly for long-stay patients [41]. The average length of stay in a mental health bed is 39 days [42], compared with 8.3 days in an acute hospital bed (2022) [43]. This poses several problems including menu fatigue, high levels of food waste, and poor compliance with healthy diet recommendations [44].

Individuals with mental illness have increased risk of metabolic disease such as type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and increased levels of obesity [45], which may be further impacted by obesogenic psychiatric medication [46]. Healthcare professionals and staff working within these settings often feel they do not have sufficient knowledge and individuals admitted are resistant to engaging in healthy diet and physical activity programmes [40]. Changes to service provision including food are often met with resistance from staff, visitors, and patients [22,23].

The global expansion of the Western diet [47,48] has contributed to climate change, leading to unstainable agricultural practices [49,50], negatively impacting food systems, nutrient bioavailability, and food costs [50,51]. The International Panel on Climate Change [2], World Health Organisation (WHO) [52], and the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation [53] recognise the need to move towards plant-based diets. Currently, 65% of the world’s nitrous oxide emissions arise from animal agriculture. The expansion of plant-based diets would significantly reduce the impact of agriculture on GHG emissions [54]. In addition, plant-based agriculture is associated with improved individual, population, and planetary health [55]. Compared with a Western diet with high amounts of animal protein, plant-based diets are more sustainable and reduce the risk of chronic diseases (i.e., cancer, dementia, cardiovascular disease). They promote water conservation and reduce land use for agriculture, including deforestation, and they reduce pollution (due to producing less methane, nitrous oxide, and carbon dioxide (CO2)) [55,56]. The EAT-Lancet Commission (2019) provided a definition for a “planetary diet or plant-forward diet”, which they propose should be mainly composed of ‘vegetables, fruit, whole grains, legumes, nuts and unsaturated fats, limited amounts of fish and poultry, and low consumption of red meat, ultra processed foods [57] added sugars, refined cereals and starchy vegetables’ [58]. This has been translated into food-based dietary guidelines [59]. The most affordable foods are typically high-fat, -salt, -sugar ultra-processed foods [60], with plant-based diets potentially a more nutritious alternative but slightly less affordable in some socio-economic settings [49,61,62]. Despite the increased cost compared with an ultra-processed-food diet, a plant-based diet is more affordable compared with an omnivorous diet (i.e., meat and dairy) [63], and offers a large diversity of nutrients, being better for overall health and less obesogenic [64], with a lower environmental impact [49].

Although there is evidence suggesting a positive relationship between the EAT-Lancet Commission [65] healthy diet (i.e., high in fruit, vegetables, fish, and whole grains) and improved mental health outcomes (i.e., reduced risk of depression, anxiety) [66,67], increased life expectancy [68], and reduced risk of cardiovascular disease [65], there is also contrasting evidence from meta-analyses suggesting that for some individuals, the consumption of vegetarian and vegan diets is associated with poorer mental health outcomes [69,70]. These longevity-associated dietary patterns include moderate amounts of wholegrains, fruits, fish, and white meat, a higher intake of milk and dairy, vegetables, nuts, and pulses, with a lower intake of eggs, red meat, and sugar-sweetened beverages and limited amounts of ultra-processed foods [68]. Although there are links between dietary inadequacy in mental ill health and poor recovery, the evidence of benefit within a psychiatric setting is not equivocal [71] and requires further research especially around the unintended consequences of plant-based diets with regards to dysphagia, constipation, disordered eating [27], dietary inadequacy, and increased nutritional risk (macro- and micronutrient deficiency) [72], especially as factors associated with treatment, such as anti-psychotic medication, are reported to increase appetite, decrease satiety, and increase the craving for sweet foods and beverages [73], with up to 75% of inpatients consuming an unhealthy diet (i.e., high levels of sugar), correlating with higher body mass index (BMI) and lower levels of education [74].

However, there is a paucity of data considering the use of plant-based diets within mental health/psychiatric facilities to improve dietary, physical, and mental health outcomes [75], particularly as there is a lack of evidence of the effects of plant-based diets on nutrition related diseases [76]. Research using integrative omics to explore mechanist pathways [77] of the impact of poor dietary habits and diet diversity [78] on mood, cognition, and nutrition-related disease may be useful [46,79], especially as a high intake of ultra-high-processed foods [79] and lower intake of foods rich in methyl-group donors (choline, betaine, methionine, folate, vitamins B6 and B12) [78,80] may lead to dysbiosis of the gut microbiome, altering the gut–brain axis [79], with downstream effects on inflammatory pathways, oxidative stress, and important neurological metabolism [77]. However, the use of plant-based diets to modulate the gut microbiome, increasing its abundance and diversity, with subsequent impact on cognition, mental, and neurological health, is speculative [81].

Poor dietary habits and nutritional deficiencies are common amongst individuals with mental ill health, including substance use disorders, impacting on recovery [82]. Although dietary patterns prioritising plant foods may improve mental health outcomes in substance use disorders [67], there is a paucity of research considering the impact of plant-based important nutritional and mental health outcomes [67,82]. Kemp et al. delivered a 10-week plant-based (vegan diet) in the context of an intensive psychiatric inpatient and outpatient substance use disorder programme for women (n = 33), with reported improvements in mental health measures, although the impact on nutritional status was not reported [83]. As a result, future research should focus on undertaking randomised controlled trials within community and acute inpatient mental health settings to explore the impact of plant-based or plant-forward diets on improving physical and mental health, their impact on recovery outcomes and relapse rates and nutritional biomarkers [82], along with impact of the use of these diets on important health, social, and sustainability outcomes.

Nutritional status may be negatively impacted by mental illness, because of the disease itself, treatments, including medication which may have a deleterious impact on appetite dysregulation, sedation, and motivation, and social and health determinants that increase the risk of nutrition-related diseases (i.e., obesity) [27]. In contrast, some severe mental health disorders such as schizophrenia may increase the risk of undernutrition, before and during admission to a psychiatric hospital, with associated risk factors including lengthy hospital stay, food insecurity, and disordered eating [27,28].

On admission to hospital, nutrition risk screening is usually completed by ward staff. The most common nutrition risk screening tool is the malnutrition universal screening tool (MUST). In an acute hospital setting this demonstrates the highest level of sensitivity for adults, although it should be noted there are high levels of bias reported [84]. Within psychiatric hospitals nutrition screening methods to detect risk include the use of tools to reveal overnutrition, malnutrition, dysphagia, constipation, and disordered eating. These tools include the approaches to schizophrenia communication (ASC) and self-report (ASC-SR) checklist, MNRS, NutriMental screener, and others [27], although more research is required to better understand the sensitivity and specificity of these tools in identifying nutrition risk in psychiatric inpatient settings [27,85]. Following identification of nutrition risk, an individual is usually then referred to a dietitian for further assessment, diagnosis, and dietary intervention. As part of a nutrition focused assessment usually includes a review of the following:

- (i)

- Anthropometry—i.e., body mass index, waist-to-hip ratio [85];

- (ii)

- Biochemistry—routine bloods (i.e., liver function test, urea and electrolytes, full blood count, vitamin D, and other micronutrients where indicated) [72];

- (iii)

- Clinical status—diagnosis and associated co-morbidities, using mental health screening tools such as the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) or Health of the Nation Outcomes Scales (HoNOS) [85];

- (iv)

- Dietary intake—using a social functioning scale [85] and validated food frequency questionnaires such as EPIC-Norfolk [86] or 15-items FFQ [87], along with the “practical nutrition knowledge about balanced meals” (PKB-7) scale [88] to assess nutritional literacy, dietary adequacy, and adherence to dietary recommendations, respectively; the results can then be used as part of:

- (v)

- Goal setting—with the patient or client [89,90].

In addition, recent research suggests that people may be reluctant to change the type of food eaten [91] especially as many people may have an attachment to meat [92,93]. Some of this may be rooted in food neophobia and a general reluctance (i.e., the disgust factor) to try something new [94], representing a barrier to the transition to a more sustainable diet [91], compounding factors that may be more prevalent in mental ill health. In addition, specialist diets, food sensitivities, disordered eating, and eating disorders make plant-based diets inappropriate for use by default [44,74]. Adherence to dietary interventions, even ones considered easy to implement and sustainable, are complex, and may be more so in individuals with mental illness, due to symptoms of depression or psychosis [95,96]. In order to comply with dietary recommendations, individuals need to be able to change what, how, and with whom they eat meals. Food choices do not just represent health literacy and nutritional intake but are also a way of communicating preference, identity, and cultural meaning [95], all of which may be negatively impacted by social determinants of mental health [97].

To understand the direction of these relationships, urgent research is required on the role diet of plant-forward diets in improving mental health outcomes for those admitted to mental health hospitals [81]. Future studies should explore what information, training and knowledge is required to support adherence to dietary recommendations [95], as well as the ideal duration for a dietary intervention [81] that is acceptable to patients and staff [98,99]. It may be useful to measure clinical outcomes and biomarkers, to help inform the effects of plant-forward diets on improving dietary and clinical outcomes for individuals admitted to mental health hospitals [51,96]. This is especially important as individual dietary habits, food cultures, and local environmental considerations can affect the promotion of plant-based diets, requiring context-specific solutions, especially as familiarity is a key factor driving individual acceptance of food-related behaviour change. This is especially relevant as individual social determinants of health equity as defined by WHO [100] may negatively impact on dietary intake and health outcomes [101,102]. The use of local foods may result in higher levels of acceptability [103] and environmental benefits [49]. Although there is a move to implement plant-based diets by default within the hospital setting [104,105,106,107], factors associated with the success of this approach in mental health hospitals amongst patients with severe mental illness remain unknown, especially with regards to potential unintended consequences including nutritional inadequacy [49,108] and increased food waste [25].

As such, the objective of this scoping review was to examine the influence of the social, medical, and physical environment on food during inpatient admissions to mental health hospitals, with the intention of identifying gaps in the existing evidence related to the default implementation of plant-based diets.

2. Methods

2.1. Preparing to Scope the Literature and Protocol Development

A scoping review was conducted to identify the key concepts within this area of research [109]. This design was chosen because it offers a framework to identify and synthesize a broad range of evidence. Primary outcomes of interest in the literature that we explored as part of this scoping review were aligned within three broad areas of interest as follows: (1) changing body habitus on admission to a mental health hospital, (2) exploring food waste in mental health hospitals, and (3) knowledge and training needs of stakeholders for a plant-based diet to be implemented (Table 1) [110,111].

Table 1.

Outcome measures of interest influencing food intake in mental health inpatient settings [27,90,111,112].

2.2. Identifying the Research Questions

1. What influence do social, medical, and physical environmental factors have on food intake during hospitalization in a mental health facility?

An a priori scoping review protocol was developed and included (1) the research question, (2) eligibility criteria of the studies be to included, (3) information sources to be searched, (4) description of a full electronic search strategy, (5) data charting process with data items included, and (6) critical appraisal and synthesis of the data in order to answer the question posed [109,113]. This scoping review is reported in line with PRISMA-ScR (Table S1).

2.3. Data Sources—Stage 1

Following the finalisation of the research question and objectives, a literature search was completed to identify studies in scope. A search strategy was devised for PubMed using key words from the grey literature and modified for additional electronic data bases using the NHS Knowledge and Library Hub website (https://library.nhs.uk/knowledgehub/ 30 September 2024). A grey literature search was also conducted in OpenGrey to expand the scope of this subject. Forward and backward citation searching was completed on studies exploring food waste in a psychiatric/mental health hospital setting. A twenty-four-year time limit was set, from 2000 to September 2024, to ensure the use of relevant contemporaneous evidence.

2.4. Search Strategy—Stage 2

A search strategy was devised for PubMed using key words including food waste, sustainability, plant-based diets (including vegan and vegetarian), psychiatric/mental health, obesity, behaviour change, and food systems, modified for additional electronic data bases, and the search was completed on 30 September 2024 (Table S1).

2.5. Study Selection—Stage 3

Titles and abstracts were screened (LVM, RM). Duplicates were deleted, and full-text articles were reviewed for eligibility.

2.5.1. Inclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria included any study which used a qualitative or quantitative design, studies in English including published theses and conference abstracts, involving food waste, sustainability, plant-based diets, psychiatric/mental health, obesity, behaviour change, and food systems. Systematic reviews were not included, but the references of studies were hand searched for any references which may have fulfilled the inclusion criteria.

2.5.2. Exclusion Criteria

Exclusion criteria were publications not in English or those that did not relate to food systems within psychiatric/mental health hospitals [113].

2.6. Data Extraction—Stage 4

Data extraction was completed using a two-stage process. A data extraction template (Microsoft Excel 2010, Redmond, WA, USA) was created and used to capture the study design, results, and conclusions, followed by content analysis.

2.7. Collating, Summarizing, and Reporting the Results—Stage 5

Data synthesis was completed using an established content analysis approach [114]; this method was chosen to report common themes within the data [115]. This approach captured descriptive aspects of the study, methodology, outcomes, and any key findings, which were coded. The content analysis was completed by selecting, coding, and creating initial codes, sub-categories, and overarching themes to develop into a conceptual framework.

3. Results

3.1. Selection and Characteristics of Included Articles

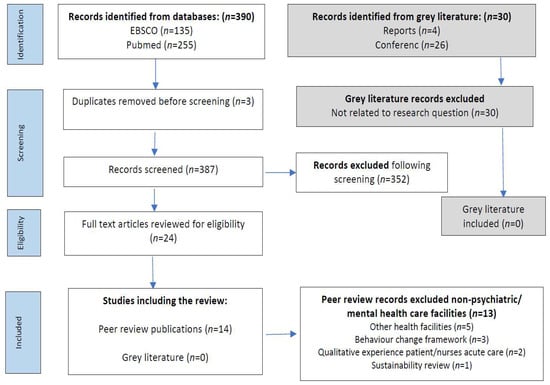

In total, 420 articles were identified. Following the removal of duplicate records, 411 titles and abstracts were screened for inclusion. The full texts of 24 articles were reviewed for eligibility and 14 studies were included in the review (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Search results through to inclusion.

3.2. Study Characteristics

The 14 included studies explored factors associated with food waste within a psychiatric/mental health hospital setting, including ward environment [116,117,118,119,120,121,122], food environments [44,123], nutrition knowledge, skills, and eating behaviours [85], theoretical framework of behaviour change [124], sustainable practices [125,126], and food waste [127]. Included in this scoping review are five qualitative studies [120,122,123,124,125], two audits [126,127], and seven quantitative studies [85,116,117,118,119,121,128] from years 2004 to 2024 from various countries including Australia [124], Canada [127,129], Denmark [119], Switzerland [85,126], the Netherlands [123], the United Kingdom [116,117,120], and the United States of America [118,121,122,125]. Several studies used qualitative interviews to examine factors associated with food waste [124,126,127], obesogenic environments in psychiatric hospitals [120,122,123], dietary habits, knowledge, and skills [85], and barriers to and facilitators of change [125], with a range of sample sizes (n = 20 to n = 196). Retrospective studies exploring changes in body habitus within psychiatric facilities covered a range of sample sizes (n = 96 to n = 328), considering changes in body weight over time (mean range: 17.2 days–5.4 years) [116,118,119,121] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Development of codes, sub-categories, and overarching themes [44,85,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127].

3.3. Content Analysis: Conceptual Framework and Overarching Themes

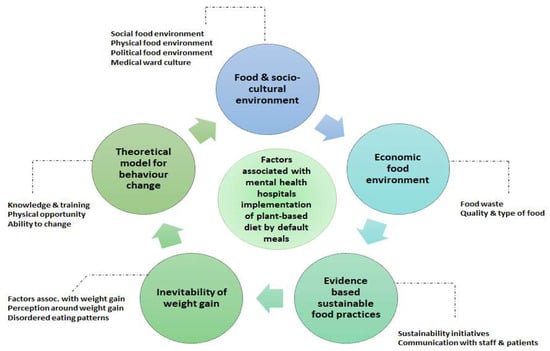

A content analysis identified 68 initial codes, 12 sub-categories, and five overarching themes (Table 2), which were identified as follows:

- Food and socio-cultural environment: (i) physical food environment, (ii) political food environment, (iii) medical ward culture;

- Evidence-based measures to reduce food waste: (i) sustainability initiatives, (ii) communication with staff and patients;

- Economic food environment: (i) quality and type of food, (ii) food waste;

- Inevitability of weight gain: (i) factors associated with weight gain, (ii) perceptions around weight gain;

- Theoretical model for behaviour change: (i) knowledge and training, (ii) physical opportunity, (iii) ability to change.

These five themes were used to explore interdependencies associated with the social, medical, and physical food environments within a psychiatric/mental health hospital setting (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Interdependencies associated with social, medical, and physical food environment within a psychiatric/mental health hospital setting [44,85,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127].

3.3.1. Food and Socio-Cultural Environment

- (i)

- Physical food environment

Food (nutrition) is seen by healthcare professionals as an important component of recovery, pre-/rehabilitation, and prevention, with compliance to nutritional standards an essential component of treatment [123]. Most hospitals have rigid structures for mealtimes [123], with three main meals and between-meal snacks [120,123]. Food preparation varies considerably, including cook-to-order, cook–chill or freeze systems, with plated, tray, or self-service [123,125]. Physical food environments vary from household-like settings [123] to clinical institutionalized communal eating areas, impacting on the mealtime experience (i.e., staff and patients eating together with conversation or patients eating meals quickly, with little opportunity for relaxation or social interaction) [120,122]. Individual patients may have the opportunity (with support) to cook their own meals once a week. Limited cooking facilities and equipment (e.g., blunt knives) may hamper skill acquisition, reducing patients’ ability to cook independently [120]. Patients appear to enjoy the creative experience of cooking, although this is seldom available to those in a secure environment, highlighting pressures around ward cohesion and skills development. Usings a systems-based approach to recognising the obesogenic nature of psychiatric inpatient stay, especially with regards to food available for very-long-stay patients [123] along with the environmental and economic impact of food waste, may also be required [120,123].

- (ii)

- Political food environment

Organisation-specific food policies play a pivotal role with regards to (i) implementation of food policies, (ii) improving food provision and meal ambience, (iii) sustainable and healthier food choices, (iv) knowledge and skills transfer for staff, visitors, and patients, and (v) co-creation of food policy [123]. Interventions should also explore environments by type, i.e., (i) physical—what is available, (ii) economic—what are the costs, (iii) political—what are the rules, and (iv) sociocultural—what are the attitudes and beliefs? [122]. Within the budgeting process, healthy and sustainable procurement often lacks priority [123].

- (iii)

- Medical ward culture

Ward staff are role models and create the ‘family’ ambience within clinical environments, bringing high-fat, high-calorie foods for their own consumption or to celebrate ward activities [118,120,122]. This may create problems for patients, especially in environments where staff are also experiencing excess weight [118]. Vieweg et al. reported 89% of subjects in their study were overweight and of these, 65% were obese, suggesting staff may inadvertently model poor dietary habits [118]. Low staffing levels may impact on the quality of food and staff acquiescing to patient requests for additional food servings, creating tension between staff and patients. Purchasing takeaway foods to consume on wards within the NHS is common, with some wards having no constraints on orders and evening and weekend orders being popular [120,122]. Staff broadly support the rights of patients to choose the type of food they wish to eat [122], although others are in favour of setting limits [123]. Initiatives such as staff, visitor, and patient education are considered important to reduce unhealthy food consumption, as well as helping with skills development [85,122,123]. Inpatients can benefit from nutritional support that aims at improving their daily structure and social inclusion, using behavioural approaches related to meal planning and social eating [85].

3.3.2. Evidence-Based Sustainable Food Practices

- (i)

- Sustainability initiatives

Initiatives implemented to reduce food waste have included (i) communication of food waste reduction efforts to staff, patients, and visitors, (ii) sustainable sourcing for food procurement, (iii) feedback mechanisms where staff and patients provide input and ratings on food quality and preference to minimize waste, (iv) regular monitoring by staff along with staff sustainability champions, (v) training of kitchen staff in food preparation techniques to reduce waste, (vi) cook-to-order to reduce overproduction, (vii) collaboration with nutritionists to develop appropriate meal plans, educate staff and patients about nutrition, and address challenges regarding food waste, (viii) selling surplus food in the employee cafeteria at reduced prices, and (ix) smaller portion sizes with the option of extra food for patients as required [125,126]. These initiatives led to significantly reduced food waste of 5.9% per kg, or 9% per patient, along with a 22% reduction in environmental pollution points, 23% in CO2e/kg emissions, and 21% in water usage (H2O—L/kg) [126].

Increasing plant-based dishes may support environmental sustainability as well as providing healthier meals [123,125]. However, associated barriers to plant-based meals by default include patient preference for dishes containing meat, challenges around planning plant-based meals, and difficulty in buying plant-based products. Associated facilitators of plant-based meals included taste-testing recipes, young patients with plant-based preferences, reducing meat portion sizes compared with vegetables, blending plant and meat protein together [125], and educations of staff, visitors, and patients [123].

- (ii)

- Communication with staff and patients

A ‘one size fits all’ approach fails to address individual patient needs, and efforts by some staff to curb patients eating patterns are ineffective as patients buy snacks and takeaways to supplement their intake [120]. Food is also used by staff to promote ward cohesion and build positive relationships [120,123]. Effective communication, including feedback mechanisms, education for visitors and patients, and training ward and kitchen staff around food waste initiatives leads to healthier food choices [123,126].

3.3.3. Economic Food Environment

- (i)

- Quality and type of food

The importance of food quality, taste, and appearance is a central theme and despite the reliance of many hospitals on centralised food production, the poor quality of food served (e.g., lack of variety, small portion sizes, low food quality) often fails to meet patient requirements [120,122,123,126]. Dissatisfaction with catering services is often a long-standing concern amongst staff and patients [120,122]. For some patients within a low secure ward environment, trips outside the ward may be allowed, which often involve purchasing high-fat, high-calorie foods or meals (i.e., on-site hospital canteen for a cooked breakfast, visit to a fast-food outlet or supermarket). Healthier options, including lower fat options, should be made available in vending machines [122]. Freshly cooked meals and fresh foods were perceived by staff and patients as the best option, providing an opportunity to tailor towards individual preference [123]. In addition, greater availability of water was considered helpful as an alternative to sugar-rich beverages, although safety concerns relating to water intoxication were noted [122]. Patient food preparation was frequently associated with poor hygiene standards, with unhealthy meals eaten in large quantities negatively impacting on physical health outcomes [120].

- (ii)

- Food waste

Food waste affects the environment and represents considerable economic loss [126]. Average plate waste has been described as between 20–28% [126,127], with lunch meals and afternoon snacks having the greatest amount of waste at 31% and 45% respectively. Delayed breakfast serving may impact on hunger at lunch [127]. Vegetables, salad, and fruits made up the greatest proportion of food wasted (11.8%). Overproduction of meals contributed a relatively small amount at 5.7% of total waste within psychiatric hospitals. Food waste is associated with a suboptimal dining environment and reduced patient satisfaction increasing, the risk of malnutrition and poorer patient outcomes [126].

3.3.4. Inevitability of Weight Gain

- (i)

- Factors associated with weight gain

On admission to mental health hospital, patients who were overweight were significantly more likely to gain weight with body mass index (BMI) worsening to obesity during an inpatient stay [116,117,118,119,121], which was proportional to the duration of admission [116,119,121]. Weight gain of 1.8 kg ± 6.0 kg [121] or 0.03 kg per day [116] occurred, with weight gain more common than weight loss [85,116] amongst patients admitted to a mental health hospital. Weight gain was often viewed as inevitable [120], with associated factors including medication (e.g., antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, and anti-depressants) [116,117,118,121], gender (e.g., males), cigarette smoking, [116,121], duration of illness, length of hospital stay, age at disease onset (i.e., younger patients had the greatest risk) [117] and high-fat, high-calorie dietary intake [119]. In addition, patients are often reported to show little interest in personal appearance, with the ubiquitous presence of tracksuits with elasticated waist-bands accommodating weight gain [120]. To reduce conflict, patients may be permitted to skip breakfast, which was associated with the consumption of higher-fat, higher-calorie foods between meals, reduced physical activity, and missed appointments [122].

- (ii)

- Perceptions around weight gain

Patients are assigned responsibility for maintaining a healthy weight or weight loss. However, this strategy suffers when there are high levels of overweight/obesity amongst ward staff [118]. With an abundance of high-calorie snacks, beverages, and takeaways, weight gain is perceived as inevitable [118,120,122].

3.3.5. Theoretical Model for Behaviour Change

- (i)

- Knowledge and training

The Behaviour Change Wheel (BCW) with theoretical components of capability (physical or psychological), opportunity (physical or social), and motivation (emotional or reflective) revealed that the dominant COM-B constructs were psychological capability (knowledge, skills), physical opportunity (environmental context and resources), and reflective motivation (social/professional role and identity beliefs about capabilities). Participants including those who worked in or managed food services reported food service staff’s lack of knowledge with regards to healthy eating, insufficient labour and time, and hospitals avoiding the need to complete audits were barriers to change. Interventions which may have the greatest impact around the implementation of waste audits include education, training, environmental restructuring, modelling, and enablement [124].

- (ii)

- Physical opportunity

There may be limited opportunities to engage in sufficient physical activity to prevent weight gain, particularly in a locked ward environment, with low levels of activity recorded [118,119,120]. Activities such as climbing stairs may be rare, contributing to physical deconditioning [120] and weight gain [119,120,122]. For individuals with ward leave, visits to the on-site gym or walks around the hospital groups may be possible but these are often constrained by staff availability to accompany patients [120]. Dysregulated sleeping patterns and social deprivation may result in night eating and reduced social eating or activities during the day. This may be associated with higher calorie intake and increased risk of metabolic syndrome. Social aspects of eating are associated with feelings of inclusion and psychological well-being and may lead to preferable food choices and healthier eating patterns [85].

- (iii)

- Ability to change

Modelling of desired behaviours for staff and patients with regards to healthy diet and reducing food waste will be required to support behaviour change [122,124]. Some patients with severe mental illness may have difficulty translating nutrition knowledge into action requiring greater support [85].

Some food service staff do not see food or food-related waste audits as part of their role, and they may have a lower willingness to implement new initiatives. This may be due to low levels of organisational interest or support from leadership teams. However, enablers of support for food service workers include coproduction/codesign of initiatives along with the development of champion roles to model organisational responsibility within the wider food service team [124] (Table 3).

Table 3.

Characteristics of studies describing the food environment within mental health hospitals.

4. Discussion

The results of this scoping review highlight a lack of research considering the use of plant-based diets by default within mental health hospitals and how this would improve nutrition outcomes for inpatients as well as reducing the ecological impact of animal-protein based diets and food waste. This review identified five overarching themes requiring further investigation: (i) the socio-cultural environment, (ii) evidence-based measures to reduce food waste, (iii) the economic food environment, (iv) inevitability of weight gain, and (v) theoretical models of behaviour change [44,85,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127]. Most mental health hospitals use contract caterers to provide food for staff, visitors, and patients typically offering an animal-protein/meat-dominated menu by default, with plant-based meals (vegetarian or vegan) as single menu options often only available on request, decreasing uptake [130]. Although there are compelling arguments for plant-based diets by default [131,132] there is a paucity of evidence regarding components associated with the successful implementation of plant-based by default within mental health hospitals. Insights from other healthcare settings, where such approaches have been successfully adopted [104,105,106,107] may offer valuable guidance. This includes understanding the impact on important physical and mental health outcomes, financial costs, GHG emissions, and the role of behaviour change models in supporting transitions. In secure mental health wards, restricted physical activities and deprivation of liberty further exacerbate these challenges [133,134]. Nutrition, knowledge, cooking, and food skills did not appear to be important barriers, although they may be prerequisites for healthy eating [85]. Staff may lack various resources or the will to implement the much-needed changes [116,117,118,119,120,121,122], resulting in mealtime environments unconducive for pleasant eating experiences [44,123]. Inpatients with severe mental illness can benefit from nutritional support that aims at improving their daily structure and social inclusion, using behavioural approaches related to meal planning and social eating [85], as admission to a mental health hospital for treatment of severe mental illness has a deleterious impact on body habitus, with an increased risk of obesity [116,117,118,119,120,121,122].

The use of a discrete choice experiment (DCE) [91,135,136,137,138] to explore food preferences in psychiatric hospitals and the trade-offs that staff, visitors, and patients would be willing to make for environmentally sustainable food choices may also support the development of behaviour-change interventions. Interventions targeting food waste and dietary changes rely on education, training, environmental restructuring, modelling, and enablement [124]. The use of theory in developing food-related interventions can identify barriers and facilitators to change [139]. The COM-B model suggests that in order to create successful behaviour change, aspects relating to capability (C)—physical, psychological—, opportunity (O)—social, physical and motivation—, and (M)—automatic, reflective—need to be present [140]. Within the theoretical domains frameworks, physical aspects include skills and the environmental context, and psychological aspects include knowledge, memory, attention, decision making, and social influences, reflective ability relates to goals, beliefs about capabilities, and consequences, automatic reinforcement, and emotions [141]. Using behavioural change frameworks such as the COM-B model [140,141,142] has indicated positive results by emphasising and obtaining staff buy-in, incentivising participation and positive behaviour, and establishing audit champions to support waste reduction [122,124]. Behavioural change techniques and theoretical domains frameworks [139] identified in dietary intervention studies may help inform future study design such as the following:

- (i)

- Knowledge exchange—opportunities to provide patients and staff with information on plant-forward diets and phased approaches to a planet-friendly diet [143];

- (ii)

- Motivational interviewing with prompts around goal setting for changes [144];

- (iii)

- Problem solving—helping patients and staff identify strategies to support advance planning of meals/food, organisation, and access to good quality food, including strategies to reduce the purchase of ultra-high-processed or fast foods [139] and self-monitoring of behaviour—through peer-led support [145].

A novel approach to engaging hospitalised patients in their nutritional care was described by Roberts et al. [143]; technology such as Nutri-Tec intervention was deployed in a tertiary teaching hospital in Queensland, Australia. This complex intervention was underpinned by theoretical frameworks, concepts (e.g., knowledge exchange and patient participation in care), and an established evidence base. Nutri-Tec provides patient participation through patient education and training with directed goal setting and patient-generated dietary intake tracking [146]. This patient-centred approach enhances collaboration between patients and staff, providing a structured framework for change. The first aspect of the Nutri-Tec intervention includes brief and impactful education on the significance of meeting energy and protein requirements during a hospital stay, with guidance on how the hospital’s electronic food service system works and how to access it via a bedside computer screen. The second aspect provides patients the opportunity to record their food intake after each meal via a bedside computer that helps track their intake relative to their individual nutrition goals. This in turn is supported by brief, daily goal setting with a healthcare professional to reinforce accountability and engagement.

Person/patient-centred approaches to staff and patient participation may help to support individualised approaches to improving patient engagement in achieving their nutrition goals [143] and can support behaviour change [124]. Patients within a secure environment may also lack the psychological or functional capacity to make better food choices [122]. This may be coupled with staff not having sufficient knowledge or experience around motivating behaviour change with regards to food choices and achieving or maintaining a healthy weight [120], as there may be considerable resistance to change [22,23,124]. However, a technological approach to engaging patients with regards to tailoring choice and education may work well with a mental health hospital, particularly as staff often feel conflicted around further encroaching on patients’ autonomy with regards to unhealthy foods choices (i.e., takeaways), portion sizes and numbers of servings at mealtimes, purchases from food carts or vending machines, or eating food from other patients’ untouched trays. At the same time, staff have expressed feelings of responsibility to restrict and control access to unhealthy food [120,122]. The development of technology-driven solutions in mental health hospitals could support person-centered participation, enabling patients and staff to actively engage in dietary changes and monitor progress to reinforce the long-term adoption of plant-based diets, but this requires further research with regards to accessibility of information in this format, with particular reference to digital literacy and skills [147,148,149] and functional ability [150,151].

An independent review of NHS hospital food [152] concentrated on local and seasonal (i.e., vegetable and fruit) food procurement and waste, rather than the need to reduce animal protein/meat consumption and promote plant-based menu cycles [132]. However, there is a move to flip this model by offering plant-based meals by default with the option for animal-based meals on request. This approach may help to prevent the obesogenic impact of inpatient admission to a mental health hospital [116,117,118,119,120,121,122], and reduce the risk of chronic diseases (e.g., diabetes) [153], simultaneously decreasing the environmental impact and economic consequences of food waste [104]. Smith et al. [104] suggest plant-based diets by default as a more sustainable way of providing food for staff, visitors, and patients; behaviour change techniques may help people to be healthier and they may be more ‘inclusive of all cultural, traditional, religious, and ethical preferences and can be free of common allergens’. Greener By Default, a movement supported by eleven hospitals in New York City, have implemented plant-based meals for staff, visitors and patients by default, reporting that after two years, more than 50% of patients chose plant-based meals, with a 36% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions, in addition to cost savings of 59 cents (46 pence) per meal [154]. Berardy et al. [155] explored the impact of plant-based diets offered to all patients in the first 24 h of admission to an acute hospital setting. A limited 7-day study suggested plant-based meals were associated with significantly reduced food waste compared with meat-based meals within this setting, although the mechanism leading to this reduction in food waste was unclear. Further to this, Sadler et al. [156] suggest that many NHS hospitals demonstrate little commitment to change to plant-based meals, referring to issues with implementation and barriers to change amongst staff and patients.

Average plate waste has been described as between 6–65% [32,126,127,132], with food making up 50% of the total waste generated within the ward environment [16,17]. Within mental health settings, common components of aspects contributing to food waste in hospitals include large portion sizes, vegetables, salad, and fruit [126,127,132]. Liwinski et al. reported economic losses associated with food waste arising from untouched or partially consumed meals. Salads, vegetables, soups, and sauces contributed to the high amount of food wasted. Food waste has significant environmental and economic implications; in order to implement sustainable practices [125,126] whilst reducing food waste, a multi-system implementation framework is needed, spanning from farm to fork [127]. Sustainability initiatives may support this, such as (i) communicating food waste reduction efforts to staff, patients, and visitors, (ii) feedback where staff and patients provide input and ratings of food quality and preferences in order to minimize waste, (iii) training kitchen staff in food preparation techniques to reduce waste, (v) collaboration with a nutritionist to develop appropriate meal plans, portion sizes, and education for staff and patients about nutrition and address challenges regarding food waste [125,126]. These initiatives can lead to significantly reduced food waste of −5.9% per kg or 9% per patient, along with 22% reductions in environmental pollution points, 23% in CO2e/kg emissions, and 21% in water usage (H2O–L/kg) [126]. However, this assumption would need to be explored in addition to the impact on nutritional status of using plant-based diets [49,108] within a mental health setting, especially when 32–48% of patients within mental health hospitals are at risk of malnutrition [157,158]. Patients with severe mental illness may be more vulnerable to unintended impacts on mental health due to plant-based meals by default [69]. As such, another approach to increasing the amount of plants in the diet is a plant-forward diet where whole-grains, fruits, vegetables, nuts, and legumes (i.e., beans and lentils) are eaten in bigger amounts. Meat, dairy, and eggs are still included in the diet but in smaller amounts [59]. These changes are associated with improved health of individuals, populations, and the planet [55,56]. Using this method, the amounts of plant proteins in the diet are increased through the use of textured soy protein, mushrooms, pulses, etc., with a phased introduction replacing a proportion of the meat product (i.e., 20% to 50%) with plant-based proteins [91]. Examples of this method can be found in the NHS recipe bank (https://foodplatform.england.nhs.uk/, accessed on 19 February 2025). However, the feasibility and acceptability of implementing these recipes within a mental health hospital setting has yet to be tested [159], particularly amongst patients whose may have entrenched food preferences for refined carbohydrates [126]. A phased approach to the implementation of plant-forward, low carbon meals within mental health hospitals may be more favourable than a system-wide implementation of offering only plant-based meals, as it will allow a gradual change which may be more acceptable to staff and patients, although this should be explored in future research studies. In addition, practical adaptions to ensure that food catering services within psychiatric hospitals settings are acceptable to all should include (i) mechanisms for continuous feedback including regular review of patient satisfactions of meals [160], (ii) access to multi-language menus including culturally appropriate and familiar meals [161], and (iii) patient representation on the catering forum responsible for meal/menu choices [44,126], which will help to support healthcare inclusion [162].

5. Research Limitations

There are several limitations to this work, relating to the paucity of evidence around the use of plant-based diets by default within mental health as well as reducing the environmental impact of food waste and animal-protein-based diets. Although the quality of the evidence within the studies examined varied was not formally assessed, some of the studies had small cohort sizes, and the quality of the evidence within the studies examined varied. Several studies used qualitative interviews to examine factors associated with food waste [124,126,127], obesogenic environments in psychiatric hospitals [120,122,123], dietary habits, knowledge, and skills [85], and barriers to and facilitators of change [125]. Although the research methods may have yielded rich data from qualitative interviews, the findings from these studies may not be translatable into other settings due to the small sample sizes ranging from 20 to 196 individuals. With regards to studies exploring changes in body habitus within psychiatric facilities, all were retrospective in nature with relatively small sample sizes [116,118,119,121] ranging from 96 to 328 individuals.

This scoping review identified a number of overarching themes associated with the (i) nutritional implications of plant-based diets, (ii) acceptability among staff, patients, and visitors and the feasibility of plant-based meal choices by default, (iii) training needs of staff, visitors, and patients around the benefits of plant-based diets and healthier food choices for maintaining or sustaining a healthy weight, (iv) the broader impact of food waste reduction, and (v) environmental and sustainability considerations aligning with frameworks such as One Health [52]. Future research should address these limitations by incorporating larger, more representative samples and robust methodologies to evaluate the impact of plant-based diets in these and other healthcare settings. This includes their potential to improve nutrition outcomes for patients, reduce the environmental impact of food waste and animal-protein-based diets, and lower the risk of chronic diseases associated with unhealthy eating behaviors in a secure mental health setting. Additionally, a holistic perspective is needed to integrate traditional knowledge with evidence-based innovations, ensuring the cultural acceptability, nutritional adequacy, and operational feasibility of plant-based diets in mental health hospitals across diverse settings.

Implications for clinical practice

Making changes to inpatient food provision within mental health hospitals is complex, with many hospitals showing little commitment to change [156]. However, effective strategies within clinical practice to improve food within mental health should consider including the following:

- (i)

- Information sharing around healthy and planet-friendly food: to staff, patients and visitors, increasing awareness and promoting support for food-based initiatives including maintaining a healthy weight;

- (ii)

- Procurement of sustainable/nutritious food: from local providers, reducing the environmental footprint and showcasing local seasonal foods;

- (iii)

- Quality improvement feedback mechanisms: offering staff, patients, and visitors the opportunity to comment on food quality along with food preferences, as this may help to improve satisfaction. This approach will also identify meals that are disliked, supporting renovation of recipes as well as areas where more information is required, as well as reducing food waste;

- (iv)

- Regular audit and monitoring and collaboration with nutritionist/dietitians: using a standardised approach and regular reviews to help organisations (including leadership teams) set targets for reducing food waste, as well as to identify meals with lower acceptance. This may be true for newer plant-based diets where more information for staff, visitors, and patients is required to increase acceptance of new dishes;

- (v)

- Kitchen staff training and knowledge exchange: to ensure food waste is minimised and to increase understanding of approaches to food waste reduction strategies;

- (vi)

- Ward staff training: to support patients and staff to make healthier planet-friendly food choices.

- (vii)

- Reduced portion sizes: have been shown to be effective in reducing food waste and the obesogenic nature of meals.

For patients with increased nutritional requirements, a flexible approach can be adopted to ensure individual needs are met [21,22,124,126]. Future research should explore a whole-systems approach to address the high levels of food waste within mental health hospitals [18,163], considering enablers of and barriers to change in relation to (i) capacity and capability; (ii) willingness to change, including staff and patient acceptance of food changes and how to gain buy-in and quick-wins; and (iii) processes, governance, and leadership to provide the opportunity for high-level support, policy, and structure to encourage a phased change towards plant-based meals [21,22,124]. Implementation science [164,165,166,167,168] along with the Com-B model and theoretical domains framework [122,124] should underpin a future study design for an implementation toolkit of plant-forward, low-carbon meals within mental health hospitals to (i) reduce food waste and associated costs, (ii) reduce greenhouse gas emissions, (iii) raise staff awareness of the benefits of plant-forward diets, and (iv) improve nutrition and health outcomes for patients and staff. Achieving these ambitions will require bold changes made at scale to mitigate the impact of climate change and support the transition to sustainable health systems [163]. Embedding reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, maintenance (RE-AIM), and a consolidated framework for implementation research (CFIR) using a structured checklist may help to support successful implementation of plant-forward diets within mental health settings. These include planning questions around who (i.e., which patients) the intervention is intended to benefit, what are the intended benefits (i.e., reduced plate waste, increased uptake of plant-forward diets), how fidelity to the intervention will be measured (i.e., plate waste or food choices), and how the benefits will be measured (i.e., physical and mental health outcome measures) [169].

6. Conclusions

Inpatient wards within mental health hospitals are obesogenic environments, with limited opportunity for meaningful engagement with physical activity, food choices that may not be tailored to individual preferences, and unrestricted access to nutritiously poor, high-fat, high-calorie foods from vending machines or takeaways, resulting in high levels of food waste. The use of plant-based diets may provide an opportunity to reduce waste management costs associated with food waste, reduce the enviromental impact of animal-protein-based diets, and offer a healthier, less obesogenic diet for patients and staff. However, patient and staff engagement using a behaviour change framework should underpin interventions aimed at addressing these challenges, incorporating training, education, and goal-setting components for staff, patients, and visitors to foster more nutritious dietary choices within an improved food environment. Future efforts should also consider integrating culturally appropriate and evidence-based innovations to enhance the feasibility and acceptability of such interventions within diverse inpatient settings. Making changes to inpatient food provision within mental health hospitals is complex, with many hospitals showing little commitment to change. However, effective strategies within clinical practice to improve food within mental health inpatient services include the following: (i) communication around healthy and planet-friendly food; (ii) sourcing of sustainable/nutritious food; (iii) quality improvement feedback mechanisms; (iv) regular audit and monitoring and collaboration with nutritionist/dietitians; (v) kitchen staff training and knowledge exchange; and (vi) ward staff training to support patients to make healthier planet friendly food choices, in addition to reduced portion sizes.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/dietetics4020018/s1, Table S1: Search strategy for PuBMed and study inclusion criteria.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.V.M.; methodology, L.V.M.; formal analysis, L.V.M. and R.M.; investigation, L.V.M.; data extraction and curation L.V.M. and R.M.; writing—original draft preparation, L.V.M.; writing—review and editing, J.V.E.B., S.V. and R.M.; project administration, L.V.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No data is available.

Conflicts of Interest

Luise Marino has received honoraria to give lectures for Abbott Laboratories, Danone, and Nestle, who had no role in role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results. None of the other authors have any conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- UNFCCC. The Paris Agreement. Available online: https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement/the-paris-agreement (accessed on 21 December 2022).

- CCARDESA. IPCC Special Report: Global Warming of 1.5 °C—Summary for Policymakers. 2019. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/chapter/spm/ (accessed on 21 December 2022).

- How Do Greenhouse Gases Actually Warm the Planet? 2022. Available online: https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/how-do-greenhouse-gases-actually-warm-planet (accessed on 28 January 2025).

- Wu, R. The carbon footprint of the Chinese health-care system: An environmentally extended input-output and structural path analysis study. Lancet Planet Health 2019, 10, e413–e419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Climate Change and Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/climate-change-and-health (accessed on 21 December 2022).

- Erol, A.; Karahan, H. Energy consumption and emission factors of a hospital in Turkey. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 207, 384–393. [Google Scholar]

- Health-Care Waste. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/health-care-waste (accessed on 16 December 2023).

- Health Care Without Harm. The Role of the Health Care Sector in Climate Change Mitigation. In London. 2022. Available online: https://healthcareclimateaction.org/node/115 (accessed on 16 December 2023).

- Health Care Without Harm (Global). Health Care Climate Footprint Report. Available online: https://global.noharm.org/resources/health-care-climate-footprint-report (accessed on 29 January 2025).

- Ngcamu, B.S. Climate change effects on vulnerable populations in the Global South: A systematic review. Nat. Hazards 2023, 118, 977–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbass, K.; Qasim, M.Z.; Song, H.; Murshed, M.; Mahmood, H.; Younis, I. A review of the global climate change impacts, adaptation, and sustainable mitigation measures. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 42539–42559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tennison, I.; Roschnik, S.; Ashby, B.; Boyd, R.; Hamilton, I.; Oreszczyn, T.; Owen, A.; Romanello, M.; Ruyssevelt, P.; Sherman, J.D.; et al. Health care’s response to climate change: A carbon footprint assessment of the NHS in England. Lancet Planet. Health 2021, 5, e84–e92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wooldridge, G.; Murthy, S. Pediatric Critical Care and the Climate Emergency: Our Responsibilities and a Call for Change. Front. Pediatr. 2020, 8, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- England NHS. National Standards for Healthcare Food and Drink. 2022. Available online: https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/national-standards-for-healthcare-food-and-drink/ (accessed on 16 January 2025).

- From Farm to Kitchen: The Environmental Impacts of U.S. Food Waste. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/land-research/farm-kitchen-environmental-impacts-us-food-waste#:~:text=Impacts%20include%3A%20greenhouse%20gas%20emissions,to%20California%20and%20New%20York (accessed on 16 January 2025).

- Alam, M.M.; Sujauddin, M.; Iqbal, G.M.A.; Huda, S.M.S. Report: Healthcare waste characterization in Chittagong Medical College Hospital, Bangladesh. Waste Manag. Res. 2008, 26, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattoso, V.D.; Schalch, V. Hospital waste management in Brazil: A case study. Waste Manag. Res. 2001, 19, 567–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutrition and Hydration Digest, 3rd ed.; British Dietetic Association: Birmingham, UK, 2023; Available online: https://www.bda.uk.com/static/176907a2-f2d8-45bb-8213c581d3ccd7ba/06c5eecf-fa85-4472-948806c5165ed5d9/Nutrition-and-Hydration-Digest-3rd-edition.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2024).

- Food Surplus and Waste in the UK—Key Facts. 2020. Available online: https://www.wrap.ngo/sites/default/files/2020-11/Food-surplus-and-waste-in-the-UK-key-facts-Jan-2020.pdf (accessed on 13 August 2024).

- Chatzipavlou, M.; Karayiannis, D.; Chaloulakou, S.; Georgakopoulou, E.; Poulia, K.A. Implementation of sustainable food service systems in hospitals to achieve current sustainability goals: A scoping review. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2024, 61, 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, N.; Collins, J.; Goodwin, D.; Porter, J. A systematic review of food waste audit methods in hospital foodservices: Development of a consensus pathway food waste audit tool. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2022, 35, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, N.; Collins, J.; Goodwin, D.; Porter, J. Factors influencing implementation of food and food-related waste audits in hospital foodservices. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1062619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, N.; Porter, J.; Goodwin, D.; Collins, J. Diverting Food Waste From Landfill in Exemplar Hospital Foodservices: A Qualitative Study. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2024, 124, 725–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudifar, K.; Raeesi, A.; Kiani, B.; Rezaie, M. Food waste in hospitals: Implications and strategies for reduction: A systematic review. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2025, 36, 50–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinninella, E.; Raoul, P.; Maccauro, V.; Cintoni, M.; Cambieri, A.; Fiore, A.; Zega, M.; Gasbarrini, A.; Mele, M.C. Hospital Services to Improve Nutritional Intake and Reduce Food Waste: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simzari, K.; Vahabzadeh, D.; Nouri Saeidlou, S.; Khoshbin, S.; Bektas, Y. Food intake, plate waste and its association with malnutrition in hospitalized patients. Nutr. Hosp. 2017, 34, 1376–1381. [Google Scholar]

- Hancox, L.E.; Lee, P.S.; Armaghanian, N.; Hirani, V.; Wakefield, G. Nutrition risk screening methods for adults living with severe mental illness: A scoping review. Nutr. Diet. 2022, 79, 349–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.; Ker, S.; Archer, D.; Gilbody, S.; Peckham, E.; Hardman, C.A. Food insecurity and severe mental illness: Understanding the hidden problem and how to ask about food access during routine healthcare. BJPsych Adv. 2023, 29, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamoi, R.; Mifune, Y.; Soriano, K.; Tanioka, R.; Yamanaka, R.; Ito, H.; Osaka, K.; Umehara, H.; Shimomoto, R.; Bollos, L.A.; et al. Association Between Dynapenia/Sarcopenia, Extrapyramidal Symptoms, Negative Symptoms, Body Composition, and Nutritional Status in Patients with Chronic Schizophrenia. Healthcare 2024, 13, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seiler, N.; Tsiglopoulos, J.; Keem, M.; Das, S.; Waterdrinker, A. Prevalence of vitamin D deficiency among psychiatric inpatients: A systematic review. Int. J. Psychiatry Clin. Pract. 2022, 26, 330–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, Y.C.; Chou, L.S.; Lin, C.H.; Wu, H.C.; Li, D.J.; Tseng, P.T. Serum folate levels in bipolar disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2019, 19, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P.; Walton, K. Plate waste in hospitals and strategies for change. e-SPEN Eur. E-J. Clin. Nutr. Metab. 2011, 6, e235–e241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent-Smith, L.; Eisenbraun, C.; Wile, H. Hospital Patients Are Not Eating Their Full Meal: Results of the Canadian 2010–2011 nutritionDay Survey. Can. J. Diet. Pract. Res. 2016, 77, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiesmayr, M.; Schindler, K.; Pernicka, E.; Schuh, C.; Schoeniger-Hekele, A.; Bauer, P.; Laviano, A.; Lovell, A.; Mouhieddine, M.; Schuetz, T.; et al. Decreased food intake is a risk factor for mortality in hospitalised patients: The NutritionDay survey 2006. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 28, 484–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, A.; Kägi-Braun, N.; Tribolet, P.; Gomes, F.; Stanga, Z.; Schuetz, P. Individualised nutritional support in medical inpatients—A practical guideline. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2020, 150, w20204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cristancho, C.; Mogensen, K.M.; Robinson, M.K. Malnutrition in patients with obesity: An overview perspective. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2024, 39, 1300–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, M.; Long, Y.; Peng, R.; He, P.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, W.; Yu, X.; Deng, L.; Zhu, Z. Epidemiology, Controversies, and Dilemmas of Perioperative Nutritional Risk/Malnutrition: A Narrative Literature Review. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2025, 18, 143–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunderle, C.; Gomes, F.; Schuetz, P.; Stumpf, F.; Austin, P.; Ballesteros-Pomar, M.D.; Cederholm, T.; Fletcher, J.; Laviano, A.; Norman, K.; et al. ESPEN practical guideline: Nutritional support for polymorbid medical inpatients. Clin. Nutr. 2024, 43, 674–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giménez-Palomo, A.; Gomes-da-Costa, S.; Borràs, R.; Pons-Cabrera, M.T.; Doncel-Moriano, A.; Arbelo, N.; Leyes, P.; Forga, M.; Mateu-Salat, M.; Pereira-Fernandes, P.M.; et al. Effects of malnutrition on length of stay in patients hospitalized in an acute psychiatric ward. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2023, 148, 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.; Day, M.; Moholkar, R.; Gilluley, P.; Goyder, E. Tackling obesity in mental health secure units: A mixed method synthesis of available evidence. BJPsych Open 2018, 4, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, N.S.; Md Nor, N.; Md Sharif, M.S.; Hamid, S.B.A.; Rahamat, S. Hospital Food Service Strategies to Improve Food Intakes among Inpatients: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The King’s Fund. Mental Health 360|Acute Care for Adults. Available online: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/insight-and-analysis/long-reads/mental-health-360-acute-mental-health-care-adults (accessed on 13 August 2024).

- The Health Foundation. Longer Hospital Stays and Fewer Admissions. Available online: https://www.health.org.uk/publications/long-reads/longer-hospital-stays-and-fewer-admissions (accessed on 13 August 2024).

- Porter, J.; Collins, J. Nutritional intake and foodservice satisfaction of adults receiving specialist inpatient mental health services. Nutr. Diet. 2022, 79, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vancampfort, D.; Wampers, M.; Mitchell, A.J.; Correll, C.U.; De Herdt, A.; Probst, M.; De Hert, M. A meta-analysis of cardio-metabolic abnormalities in drug naïve, first-episode and multi-episode patients with schizophrenia versus general population controls. World Psychiatry 2013, 12, 240–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakshasa-Loots, A.M.; Steyn, C.; Swiffen, D.; Marwick, K.F.M.; Semple, R.K.; Reynolds, R.M.; Burgess, K.; Lawrie, S.M.; Lightman, S.L.; Luz, S.; et al. Metabolic biomarkers of clinical outcomes in severe mental illness (METPSY): Protocol for a prospective observational study in the Hub for metabolic psychiatry. BMC Psychiatry 2025, 25, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozaffarian, D. Defining a healthy diet globally: The good, the bad, and the ugly. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2024, 120, 1003–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanzo, J.; Rudie, C.; Sigman, I.; Grinspoon, S.; Benton, T.G.; Brown, M.E.; Covic, N.; Fitch, K.; Golden, C.D.; Grace, D.; et al. Sustainable food systems and nutrition in the 21st century: A report from the 22nd annual Harvard Nutrition Obesity Symposium. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 115, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viroli, G.; Kalmpourtzidou, A.; Cena, H. Exploring Benefits and Barriers of Plant-Based Diets: Health, Environmental Impact, Food Accessibility and Acceptability. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owino, V.; Kumwenda, C.; Ekesa, B.; Parker, M.E.; Ewoldt, L.; Roos, N.; Lee, W.T.; Tome, D. The impact of climate change on food systems, diet quality, nutrition, and health outcomes: A narrative review. Front. Clim. 2022, 4, 941842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente-Suárez, V.J.; Beltrán-Velasco, A.I.; Redondo-Flórez, L.; Martín-Rodríguez, A.; Tornero-Aguilera, J.F. Global Impacts of Western Diet and Its Effects on Metabolism and Health: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- One Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/one-health (accessed on 26 January 2025).

- Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Food Security and Nutrition and Sustainable Agriculture. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/topics/food-security-and-nutrition-and-sustainable-agriculture (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- Xu, X.; Sharma, P.; Shu, S.; Lin, T.S.; Ciais, P.; Tubiello, F.N.; Smith, P.; Campbell, N.; Jain, A.K. Global greenhouse gas emissions from animal-based foods are twice those of plant-based foods. Nat. Food 2021, 2, 724–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemler, E.C.; Hu, F.B. Plant-Based Diets for Personal, Population, and Planetary Health. Adv. Nutr. 2019, 10, S275–S283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibbs, J.; Cappuccio, F.P. Plant-Based Dietary Patterns for Human and Planetary Health. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food Compliance Solutions. Ultra-Processed Foods: Nova Classification. 2021. Available online: https://regulatory.mxns.com/en/ultra-processed-foods-nova-classification (accessed on 29 January 2025).

- Willett, W.; Rockström, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermeulen, S.; Garnett, T.; Tilman, D.; DeClerck, F.; Wood, A.; et al. Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT-Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet 2019, 393, 447–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EAT. EAT-Lancet Commission Brief for Everyone. Available online: https://eatforum.org/lancet-commission/eatinghealthyandsustainable/ (accessed on 4 February 2025).

- Hoenink, J.C.; Garrott, K.; Jones, N.R.V.; Conklin, A.I.; Monsivais, P.; Adams, J. Changes in UK price disparities between healthy and less healthy foods over 10 years: An updated analysis with insights in the context of inflationary increases in the cost-of-living from 2021. Appetite 2024, 197, 107290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drewnowski, A. Analysing the affordability of the EAT–Lancet diet. Lancet Glob. Health 2020, 8, e6–e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirvonen, K.; Bai, Y.; Headey, D.; Masters, W.A. Affordability of the EAT-Lancet reference diet: A global analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2020, 8, e59–e66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pais, D.F.; Marques, A.C.; Fuinhas, J.A. The cost of healthier and more sustainable food choices: Do plant-based consumers spend more on food? Agric. Food Econ. 2022, 10, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mambrini, S.P.; Penzavecchia, C.; Menichetti, F.; Foppiani, A.; Leone, A.; Pellizzari, M.; Sileo, F.; Battezzati, A.; Bertoli, S.; De Amicis, R. Plant-based and sustainable diet: A systematic review of its impact on obesity. Obes. Rev. 2025, p. e13901. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/obr.13901?msockid=12382da5a90f6ceb15f838b7ad0f67c3 (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Liu, J.; Shen, Q.; Wang, X. Emerging EAT-Lancet planetary health diet is associated with major cardiovascular diseases and all-cause mortality: A global systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Nutr. 2024, 43, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adan, R.A.H.; van der Beek, E.M.; Buitelaar, J.K.; Cryan, J.F.; Hebebrand, J.; Higgs, S.; Schellekens, H.; Dickson, S.L. Nutritional psychiatry: Towards improving mental health by what you eat. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2019, 29, 1321–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghighatdoost, F.; Mahdavi, A.; Mohammadifard, N.; Hassannejad, R.; Najafi, F.; Farshidi, H.; Lotfizadeh, M.; Kazemi, T.; Karimi, S.; Roohafza, H.; et al. The relationship between a plant-based diet and mental health: Evidence from a cross-sectional multicentric community trial (LIPOKAP study). PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0284446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]