Impact of COVID-19 Outbreak on the Level of Worry and Its Association to Modified Active Mobility Behaviour among Australian Children: A Cross-Sectional National Study †

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Data

2.2. Workflow of the Survey

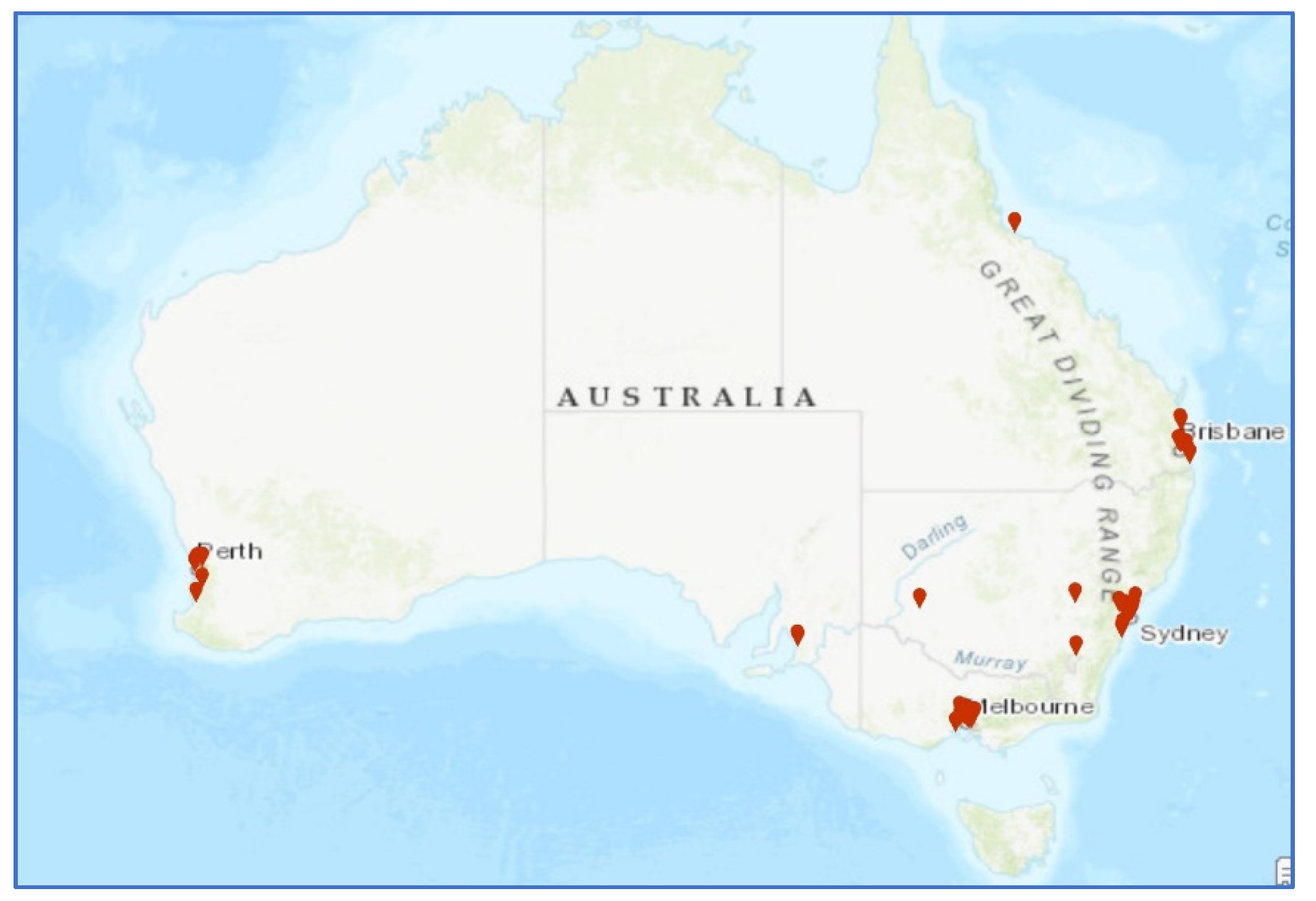

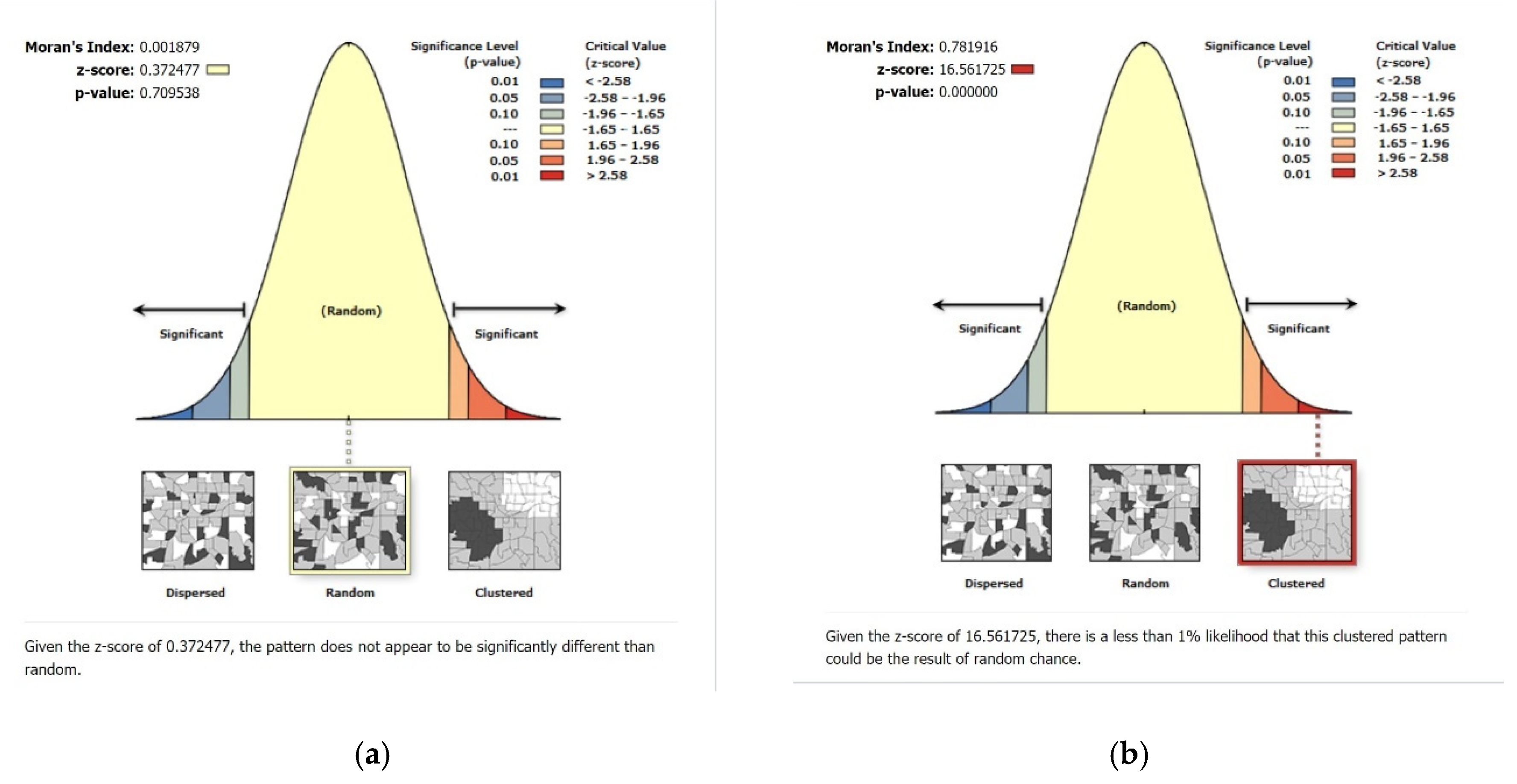

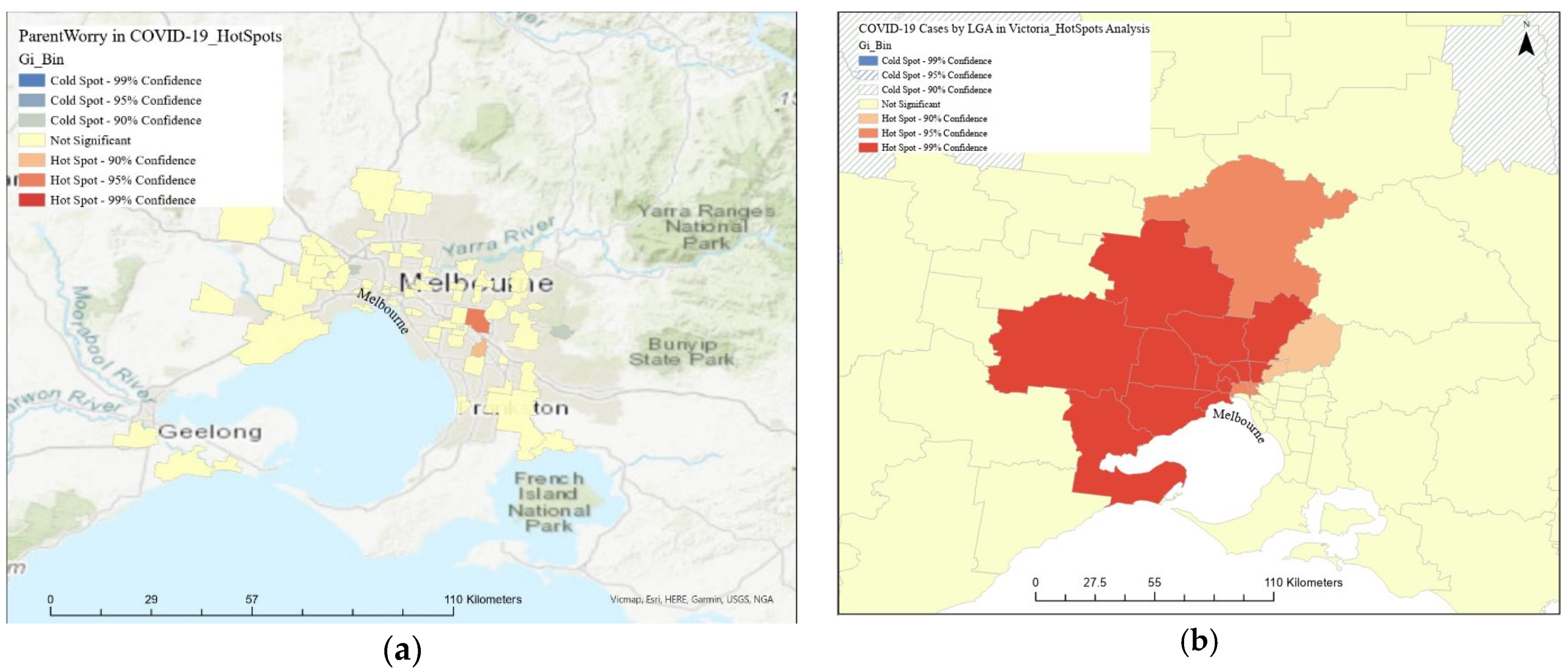

2.3. Spatial Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Parent and Children’s Characteristics

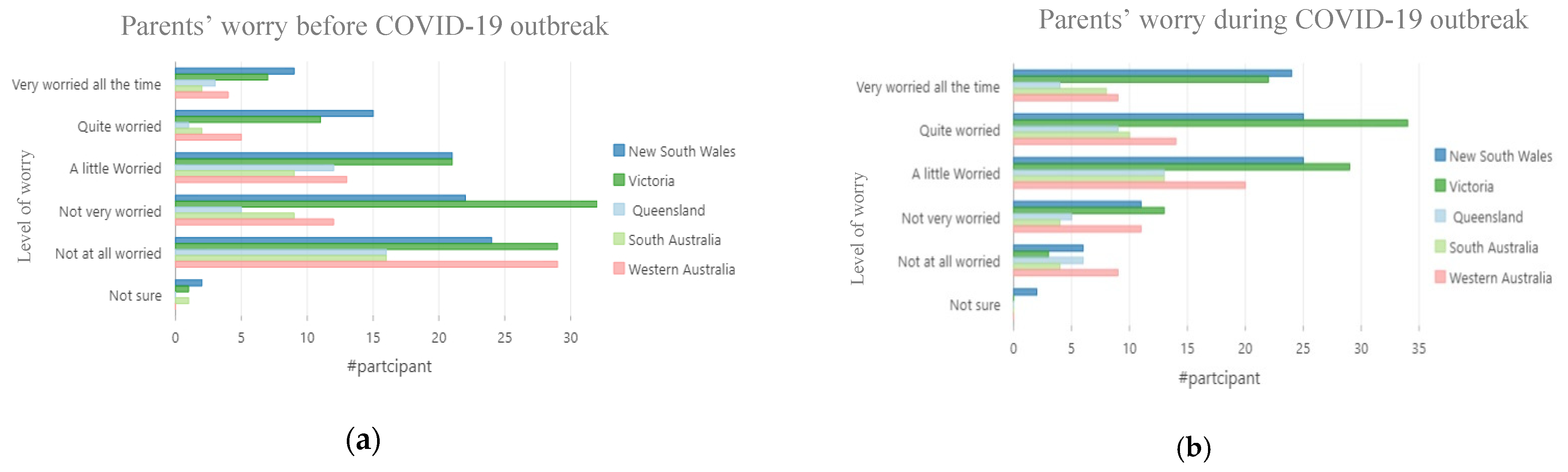

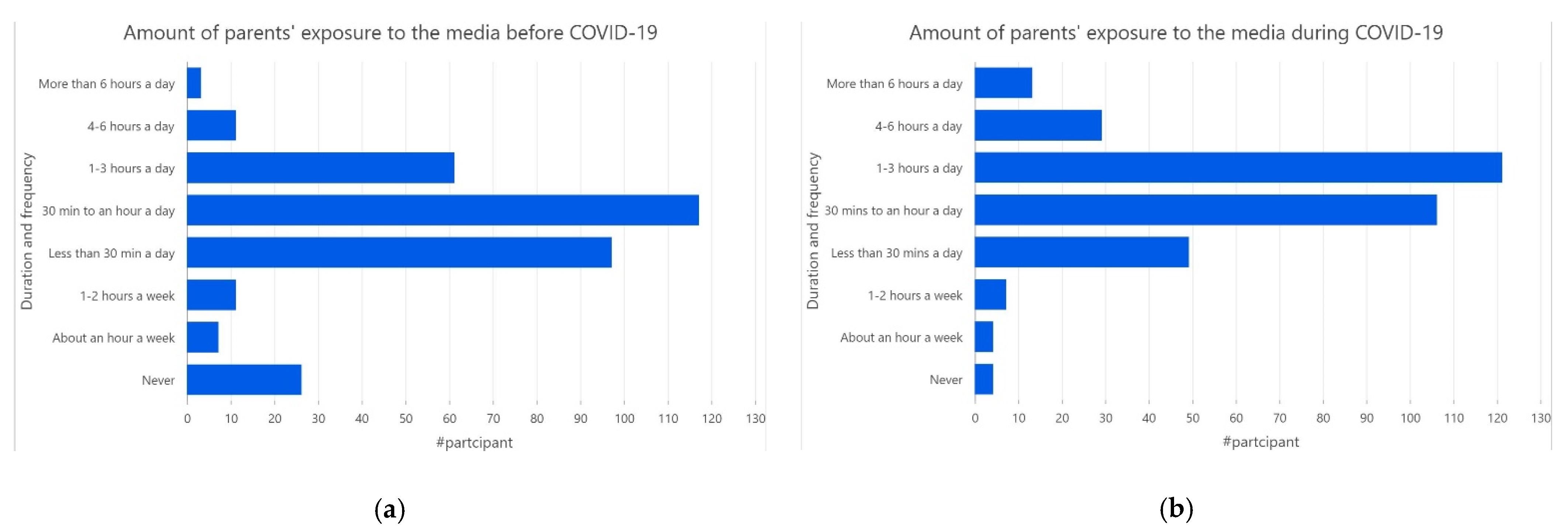

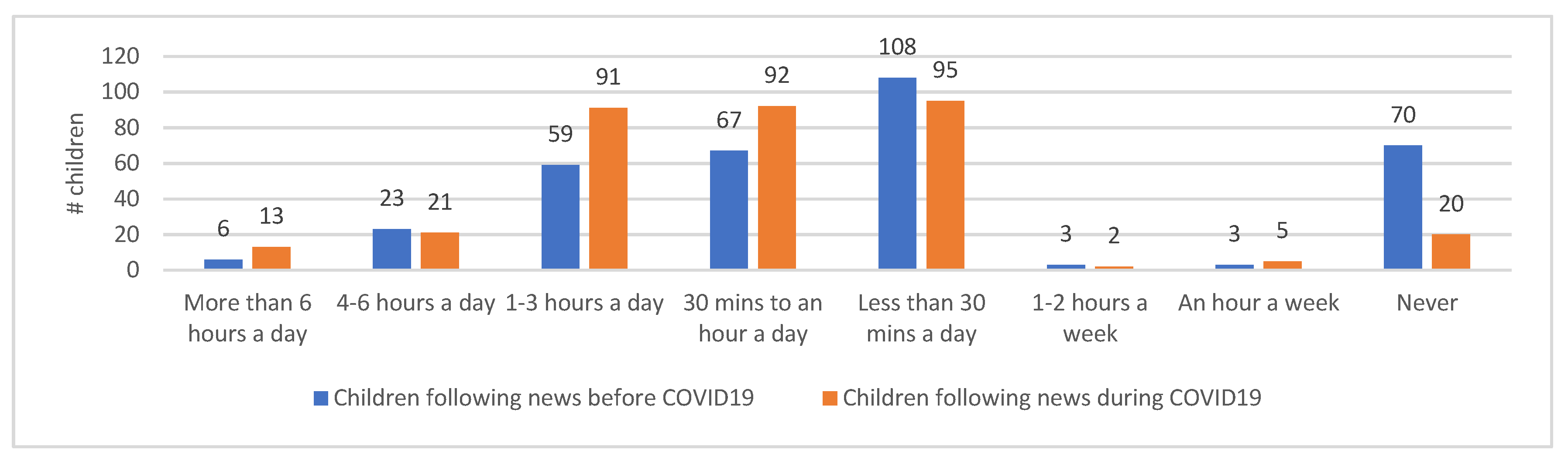

3.2. Parents’ Exposures to Media Coverage and Correlation to the Level of Worry

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bergquist, R.; Stengaard, A.-S. Covid-19: End of the beginning? Geospat Health 2020, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garfin, D.R.; Silver, R.C.; Holman, E.A. The novel coronavirus (COVID-2019) outbreak: Amplification of public health consequences by media exposure. Health Psychol. 2020, 39, 355–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, R.R.; Garfin, D.R.; Holman, E.A.; Silver, R.C. Distress, worry, and functioning following a global health crisis: A national study of Americans’ responses to Ebola. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2017, 5, 513–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Holman, E.A.; Garfin, D.R.; Silver, R.C. Media’s role in broadcasting acute stress following the Boston Marathon bombings. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Garfin, D.R.; Holman, E.A.; Silver, R.C. Cumulative exposure to prior collective trauma and acute stress responses to the Boston Marathon bombings. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 26, 675–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Department of Health. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Current Situation and Case Numbers, 24 November 2020 ed.; Australian Government, Department of Health: Canberra, Australia, 2020.

- Ware, J.E.; Sherbourne, C.D. The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual Framework and Item Selection. Méd. Care 1992, 30, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- RAND Health Care. 36-Item Short Form Survey Instrument (SF-36). Available online: https://www.rand.org/health-care/surveys_tools/mos/36-item-short-form/survey-instrument.html (accessed on 11 April 2020).

- ESRI. ArcGIS Pro. Available online: https://pro.arcgis.com/ (accessed on 14 December 2020).

- Silver, R.C.; Holman, E.A.; Andersen, J.P.; Poulin, M.; McIntosh, D.N.; Gil-Rivas, V. Mental-and physical-health effects of acute exposure to media images of the September 11, 2001, attacks and the Iraq War. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 24, 1623–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Variable | Coefficient [a] | StdError | t-Statistic | Probability [b] | Robust_SE | Robust_t | Robust_Pr [b] | VIF [c] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parents’ direct exposure to COVID-19 | 0.173496 | 0.115020 | 1.508405 | 0.132435 | 0.101130 | 1.715585 | 0.087199 | 1.250086 |

| Parents’ perception of safety before COVID-19 | 0.019415 | 0.054351 | 0.357215 | 0.721175 | 0.061451 | 0.315947 | 0.752255 | 1.045090 |

| Parents’ ability to control worry | 0.077366 | 0.082453 | 0.938302 | 0.348774 | 0.073236 | 1.056387 | 0.291568 | 1.288813 |

| Parents following the news in media before COVID-19 | −0.153906 | 0.262035 | −0.587350 | 0.557380 | 0.178021 | −0.864540 | 0.387916 | 1.098175 |

| Parents following the news in media during COVID-19 | 0.145401 | 0.036053 | 4.032969 | 0.000075 * | 0.035189 | 4.131950 | 0.000051 * | 1.135791 |

| Variables | Coefficient [a] | StdError | z-Statistic | Probability [b] | VIF [c] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parents’ gender | −0.028637 | 0.053690 | −0.533384 | 0.593768 | 1.090314 |

| Household income | 0.005574 | 0.025652 | 0.217290 | 0.827983 | 1.071606 |

| Parents’ income change during COVID-19 | 0.018846 | 0.018661 | 1.009950 | 0.312519 | 1.009999 |

| Living in place with backyard | 0.023516 | 0.075866 | 0.309962 | 0.756590 | 1.007281 |

| Parents’ direct exposure to COVID-19 | −0.044463 | 0.043935 | −1.012010 | 0.311533 | 1.242509 |

| Perception of safety before COVID-19 | −0.047679 | 0.021654 | −2.201846 | 0.027676 * | 1.064312 |

| Parents’ level of worry on children playing during COVID-19 | 0.075110 | 0.022244 | 3.376706 | 0.000734 * | 1.031549 |

| Parents’ history of controlling worry feeling | 0.081566 | 0.030697 | 2.657105 | 0.007881 * | 1.240850 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zougheibe, R.; Norman, R.; Gudes, O.; Dewan, A. Impact of COVID-19 Outbreak on the Level of Worry and Its Association to Modified Active Mobility Behaviour among Australian Children: A Cross-Sectional National Study. Med. Sci. Forum 2021, 4, 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/ECERPH-3-09009

Zougheibe R, Norman R, Gudes O, Dewan A. Impact of COVID-19 Outbreak on the Level of Worry and Its Association to Modified Active Mobility Behaviour among Australian Children: A Cross-Sectional National Study. Medical Sciences Forum. 2021; 4(1):13. https://doi.org/10.3390/ECERPH-3-09009

Chicago/Turabian StyleZougheibe, Roula, Richard Norman, Ori Gudes, and Ashraf Dewan. 2021. "Impact of COVID-19 Outbreak on the Level of Worry and Its Association to Modified Active Mobility Behaviour among Australian Children: A Cross-Sectional National Study" Medical Sciences Forum 4, no. 1: 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/ECERPH-3-09009

APA StyleZougheibe, R., Norman, R., Gudes, O., & Dewan, A. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 Outbreak on the Level of Worry and Its Association to Modified Active Mobility Behaviour among Australian Children: A Cross-Sectional National Study. Medical Sciences Forum, 4(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/ECERPH-3-09009